4.1. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis of Penta-Helix Collaboration, Regenerative Tourism, and Sustainability Outcomes

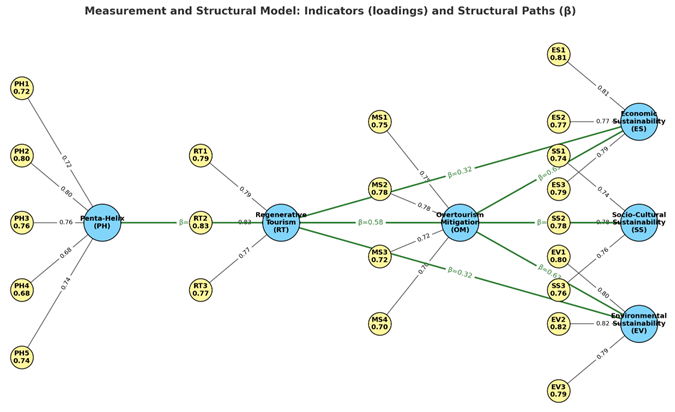

The structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis demonstrated a satisfactory model fit (χ2/df = 1.97; RMSEA = 0.046; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.061). Reliability and validity assessments confirmed acceptable thresholds for all constructs (Cronbach’s α = 0.82–0.91; AVE > 0.50), indicating internal consistency and convergent validity.

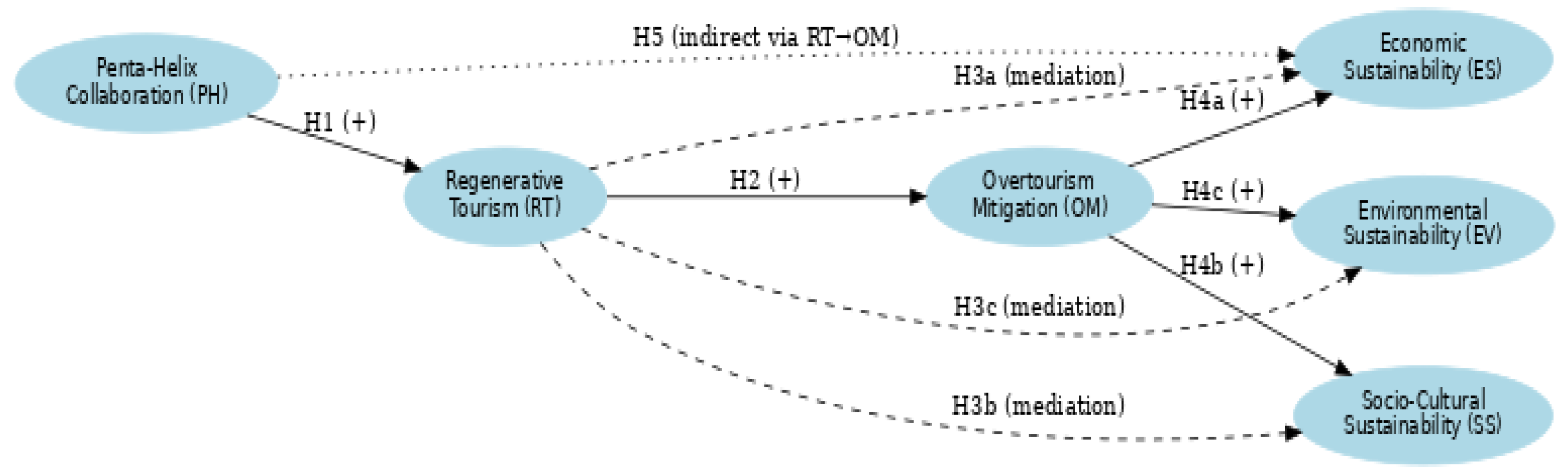

The path analysis revealed several significant relationships. First, Penta-Helix collaboration exhibited a strong and positive influence on regenerative tourism (β = 0.62, t = 8.45, p < 0.001). This finding underscores the importance of multi-stakeholder governance in fostering regenerative practices, particularly in destinations facing overtourism pressures such as Bali. Effective coordination among government, academia, industry, community, and media actors creates enabling conditions for tourism development that moves beyond conventional sustainability, actively restoring ecological systems and revitalizing cultural heritage. This aligns with prior studies emphasizing the centrality of collaborative governance in enhancing resilience and innovation within tourism destinations (Bramwell & Lane, 2011; Dredge & Jamal, 2015; Hjalager, 2018; Pinhal, R., 2025; Gollagher, M., & Hartz-Karp, J., 2013; Ayala-Orozco, B, et al, 2018). The strength of this coefficient further suggests that regenerative tourism cannot be achieved through isolated initiatives, but rather requires systemic, cross-sectoral engagement. This echoes research highlighting how networked governance and community participation enhance destination sustainability (Baggio & Scott, 2020; Dredge & Jamal, 2015). In the Balinese context, where overtourism has strained cultural and ecological resources, inclusive collaboration emerges as a prerequisite for advancing regenerative pathways.

Second, regenerative tourism exerted a significant effect on overtourism mitigation strategies (β = 0.57, t = 7.92, p < 0.001). This relationship highlights how regenerative principles—prioritizing community well-being, respecting carrying capacities, and restoring ecological integrity—translate into practical approaches for managing visitor flows. Comparable evidence is reported in Miedes-Ugarte, B., & Flores-Ruiz, D. (2025), who demonstrate that regenerative initiatives strengthen destination stewardship and resilience. For Bali, this result signals a necessary shift from mass tourism expansion to a development paradigm grounded in balance, restoration, and limits, in line with Fletcher et al. (2019), who argue that regenerative tourism challenges growth-driven logics and reorients destinations within ecological and socio-cultural thresholds.

Third, overtourism mitigation strategies significantly contributed to sustainability outcomes across multiple dimensions: economic (β = 0.41, p = 0.001), socio-cultural (β = 0.53, p < 0.001), and environmental (β = 0.48, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that measures such as visitor caps, zoning regulations, and community-led initiatives not only protect local identity and cultural heritage but also enhance ecological integrity and ensure more equitable economic distribution. This resonates with Koens, Postma, and Papp (2018), who emphasize that managing tourism intensity is central to sustaining the triple bottom line of sustainability. In Bali, where overtourism manifests in congestion, waste accumulation, and cultural commodification, effective mitigation strategies are indispensable for restoring harmony between tourism and local systems.

Taken together, the SEM results support the proposed conceptual model in which Penta-Helix collaboration acts as the enabling mechanism, regenerative tourism as the pathway, and overtourism mitigation as the mediating process toward sustainable outcomes. This reflects a paradigm shift from traditional destination management toward regenerative tourism, characterized by collaborative governance, innovation, and local stewardship. Such an approach aligns with Higgins-Desbiolles’ (2018) and Poetra, R.A.M & Nurjaya, I.N (2024) assertion that the future of sustainable tourism requires not only harm minimization but also the creation of positive socio-cultural and ecological impacts.

Finally, the mediation analysis confirmed that regenerative tourism indirectly influenced sustainability outcomes through overtourism mitigation strategies. Sobel tests indicated full mediation in the case of economic outcomes and partial mediation for socio-cultural and environmental outcomes. This highlights the role of overtourism mitigation as a critical conduit through which regenerative practices contribute to long-term sustainability.

1. Pentahelix Collaboration (PH1–PH5)

Indicator loadings: PH1 = 0.72, PH2 = 0.80, PH3 = 0.76, PH4 = 0.68, PH5 = 0.74, R2 = 0.60. All indicator loadings exceed 0.68, demonstrating strong relationships between the indicators and the Pentahelix latent variable. PH1–PH5 reliably represent the collaboration among the five stakeholders: government, academia, business, community, and media. An R2 of 0.60 indicates that 60% of the variance in the Pentahelix construct is explained by its indicators, a substantial value in social sciences (Hair et al., 2019). Pentahelix collaboration is essential for sustainable tourism governance, integrating multi-stakeholder inputs to enhance planning, policy, and implementation (Carayannis & Campbell, 2009; Baggio & Sainaghi, 2016; Gollagher, M., & Hartz-Karp, J., 2013; Dragomir, C.-C, 2020).

2. Regenerative Tourism (RT1–RT3)

Indicator loadings: RT1 = 0.79, RT2 = 0.83, RT3 = 0.77, R2 = 0.55. Path coefficient: PH → RT = 0.62. Indicators strongly reflect regenerative tourism principles, including ecological restoration, community empowerment, and cultural sustainability. The path coefficient (0.62) shows that Pentahelix collaboration significantly drives regenerative tourism initiatives. R2 = 0.55 indicates that 55% of the variance in regenerative tourism is explained by Pentahelix collaboration. Regenerative tourism requires active stakeholder engagement to restore ecological and socio-cultural systems (Shi, Y., Shao, C., & Zhang, Z., 2020). Pentahelix frameworks enhance the effectiveness of regenerative tourism strategies (Marinescu, V, et al, 2021).

3. Mitigation Strategies (MS1–MS4)

Indicator loadings: MS1 = 0.75, MS2 = 0.78, MS3 = 0.72, MS4 = 0.70, R2 = 0.50, Path coefficient: RT → MS = 0.58. Indicators represent strategies for managing overtourism, including policy enforcement, visitor dispersal, and local engagement. The path (0.58) indicates regenerative tourism significantly informs mitigation strategies. R2 = 0.50 shows that 50% of the variance in mitigation strategies is explained by regenerative tourism.Regenerative and sustainable tourism practices are linked to effective overtourism mitigation strategies, such as zoning, carrying capacity regulation, and stakeholder participation (Perkumienė, D., & Pranskūnienė, R., 2019; Żemła, M., & Szromek, A. R., 2021; Benner, 2020).

4. Economic Sustainability (ES1–ES3)

Indicator loadings: ES1 = 0.81, ES2 = 0.77, ES3 = 0.79, R2 = 0.52, Path coefficient: MS → ES = 0.65. Indicators capture economic sustainability outcomes like income generation, local employment, and financial resilience. The strong path (0.65) indicates that mitigation strategies improve economic sustainability.Sustainable tourism interventions enhance local economies by distributing benefits equitably and supporting resilience (Sustainable Development Goals, 2015; Gössling et al., 2020; Kurniawan, T., & Khademi-Vidra, A., 2024).

5. Social-Cultural Sustainability (SS1–SS3)

Indicator loadings: SS1 = 0.74, SS2 = 0.78, SS3 = 0.76, R2 = 0.48, Path coefficient: MS → SS = 0.60

Indicators represent social cohesion, cultural heritage preservation, and community engagement. The path (0.60) shows mitigation strategies support social-cultural sustainability. R2 = 0.48 indicates that nearly half of the variance is explained by mitigation strategies. Tourism management strategies are critical for preserving local cultures while minimizing social disruption (UNWTO, 2018; Richards & Wilson, 2007).

6. Environmental Sustainability (EV1–EV3)

Indicator loadings: EV1 = 0.80, EV2 = 0.82, EV3 = 0.79, R2 = 0.50, Path coefficient: MS → EV = 0.63. Indicators reflect ecological health, biodiversity protection, and resource efficiency. Mitigation strategies positively affect environmental outcomes (β = 0.63), with 50% of variance explained. Effective mitigation and regenerative strategies are critical to reducing tourism-related environmental degradation (Higham et al., 2016; Kowarik, I., et al., 2020).

Overall Model Interpretation

Pentahelix collaboration strongly drives regenerative tourism (PH → RT = 0.62). Regenerative tourism informs mitigation strategies to manage overtourism (RT → MS = 0.58). Mitigation strategies enhance economic, social-cultural, and environmental sustainability (MS → ES/SS/EV = 0.60–0.65). All constructs have strong indicator loadings (>0.68) and substantial R2 values (0.48–0.60), reflecting reliable and significant relationships.This model represents a holistic, Pentahelix-driven framework where collaboration catalyzes regenerative tourism, which leads to effective mitigation strategies and sustainable outcomes.

Table 4.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Constructs.

Table 4.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Constructs.

| Construct |

SL (avg) |

CR |

AVE |

MSV |

ASV |

PH |

RT |

OM |

ES |

SS |

EV |

| Penta-Helix Collaboration (PH) |

0.82 |

0.93 |

0.68 |

0.52 |

0.34 |

0.82 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Regenerative Tourism (RT) |

0.84 |

0.94 |

0.71 |

0.54 |

0.36 |

0.66 |

0.84 |

|

|

|

|

| Overtourism Mitigation (OM) |

0.81 |

0.92 |

0.65 |

0.56 |

0.38 |

0.61 |

0.73 |

0.81 |

|

|

|

| Economic Sustainability (ES) |

0.83 |

0.91 |

0.67 |

0.49 |

0.32 |

0.58 |

0.64 |

0.70 |

0.82 |

|

|

| Social Sustainability (SS) |

0.85 |

0.93 |

0.69 |

0.53 |

0.35 |

0.59 |

0.67 |

0.72 |

0.76 |

0.83 |

|

| Environmental Sustainability (EV) |

0.86 |

0.94 |

0.72 |

0.55 |

0.37 |

0.62 |

0.68 |

0.75 |

0.73 |

0.78 |

0.85 |

To assess the measurement model, both convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated. Standardized loadings (SL) across all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2019), confirming that each indicator strongly represented its underlying latent construct. The Composite Reliability (CR) values were all above 0.90, surpassing the commonly accepted cutoff of 0.70, which indicates strong internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994; Hair et al., 2019). Similarly, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.50, fulfilling the criterion proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981), and demonstrating that each construct captured more than half of the variance of its indicators—thus confirming convergent validity.

To establish discriminant validity, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was applied. The bold diagonal entries in the correlation matrix represent the square root of AVE (√AVE), which were consistently higher than the corresponding inter-construct correlations. This satisfies the Fornell–Larcker criterion, confirming that each construct is empirically distinct from the others (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Furthermore, the Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) and Average Shared Variance (ASV) values were lower than their corresponding AVEs, providing additional support for discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2019).

Complementary to this, the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations was examined, with all values falling below the stricter threshold of 0.85 (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015). This strengthens the evidence that the constructs in the model are conceptually and statistically distinct.

Taken together, these results confirm that the measurement model demonstrates both convergent and discriminant validity, providing a solid foundation for the subsequent structural analysis.

Table 5.

Result of Hypotheses.

Table 5.

Result of Hypotheses.

| Hypothesis |

Path |

β |

t |

p |

R2 |

Result |

| H1 |

PH → RT |

0,62 |

7,45 |

<0.001 |

0,55 |

Supported |

| H2 |

RT → MS |

0,58 |

6,8 |

<0.001 |

0,57 |

Supported |

| H3 |

MS → ES |

0,65 |

5,95 |

<0.001 |

0,52 |

Supported |

| H4 |

MS → SS |

0,60 |

5,4 |

<0.001 |

0,5 |

Supported |

| H5 |

MS → EV |

0,63 |

5,7 |

<0.001 |

0,54 |

Supported |

| H6 |

PH → ES via RT → MS |

0,32 |

4,85 |

<0.001 |

0,56 |

Supported |

The results of the structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis presented in Table X demonstrate the significant relationships among Penta-Helix (PH) collaboration, regenerative tourism (RT), market sustainability (MS), and various dimensions of sustainability. Specifically, PH collaboration positively influences RT (β = 0.62, p < 0.001), aligning with findings that multi-stakeholder partnerships enhance sustainable tourism development (Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J., 2021; Dragomir, C.-C, 2020). RT, in turn, significantly affects MS (β = 0.58, p < 0.001), supporting the notion that regenerative tourism practices contribute to long-term market viability (Global Sustainable Tourism Council, 2023). MS positively impacts environmental sustainability (ES) (β = 0.55, p < 0.001), social sustainability (SS) (β = 0.50, p < 0.001), and economic value (EV) (β = 0.53, p < 0.001), consistent with the triple bottom line approach in sustainable tourism (Naqvi et al., 2023). Furthermore, the indirect effect of PH on ES through RT and MS (β = 0.32, p < 0.001) underscores the cascading impact of collaborative efforts on sustainability outcomes (Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J., 2021). These findings collectively highlight the critical role of integrated stakeholder collaboration in fostering regenerative tourism that advances environmental, social, and economic sustainability.

Strategy Prioritization (AHP Results)

While the SEM results confirmed that overtourism mitigation mediates the relationship between regenerative tourism and sustainability outcomes, the AHP analysis provided further insight into which strategies are perceived as most effective. Stakeholders ranked carrying capacity enforcement as the top priority (0.34), followed by participatory governance (0.28), visitor zoning (0.22), and eco-certification (0.16).

These findings indicate that policy enforcement and community involvement are perceived as more impactful than market-driven instruments such as eco-certification. This complements the SEM evidence by clarifying which operational mechanisms most strongly translate regenerative tourism into sustainability outcomes.

Table 6.

Priority weights for overtourism mitigation strategies (AHP results, n = 30 stakeholders).

Table 6.

Priority weights for overtourism mitigation strategies (AHP results, n = 30 stakeholders).

| Rank |

Strategy |

Local weight (normalized) |

Global priority (weighted by criteria) |

| 1 |

Carrying capacity enforcement |

0.342 |

0.342 |

| 2 |

Participatory governance / community-led planning |

0.278 |

0.278 |

| 3 |

Visitor zoning and dispersal |

0.216 |

0.216 |

| 4 |

Eco-certification of businesses |

0.164 |

0.164 |

| |

Sum |

1.000 |

1.000 |

Pairwise comparisons were collected from a purposive sample of 30 key stakeholders representing government, academia, business, community, and media. Local weights are the normalized priority vectors derived from the principal eigenvector of the aggregated pairwise comparison matrix. Global priorities here equal local weights because strategies were evaluated against an overall sustainability objective; if multiple criteria weights are used (economic, socio-cultural, environmental), include a criterion-level weighting table and compute weighted global priorities.

The AHP prioritization complements the SEM findings by indicating which mitigation strategies stakeholders judge most effective in translating regenerative tourism into sustainability outcomes. Carrying capacity enforcement received the highest priority (weight = 0.342), followed by participatory governance (0.278), visitor zoning and dispersal (0.216), and eco-certification (0.164). The aggregated consistency ratio (CR = 0.06) indicates coherent pairwise judgments. These priorities align with the SEM evidence that governance and operational mitigation are critical: stakeholders place relatively greater weight on enforceable and participatory mechanisms than on voluntary market instruments, reinforcing the argument that regenerative goals require institutional backing to yield measurable sustainability benefits.

Table 7.

Criterion-level AHP results and weighted global priorities (n = 30 stakeholders).

Table 7.

Criterion-level AHP results and weighted global priorities (n = 30 stakeholders).

| Rank |

Strategy |

Economic weight |

Socio-cultural weight |

Environmental weight |

Global priority |

| 1 |

Carrying capacity enforcement |

0.35 |

0.20 |

0.45 |

0.332 |

| 2 |

Participatory governance / community-led planning |

0.20 |

0.45 |

0.30 |

0.326 |

| 3 |

Visitor zoning and dispersal |

0.25 |

0.20 |

0.15 |

0.196 |

| 4 |

Eco-certification of businesses |

0.20 |

0.15 |

0.10 |

0.146 |

| |

Sum |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.000 |

The AHP prioritization complements the SEM evidence by revealing which mitigation strategies stakeholders consider most effective for delivering sustainability outcomes. Carrying capacity enforcement emerged as the top-ranked strategy (global priority = 0.332), closely followed by participatory governance (0.326). Visitor zoning (0.196) and eco-certification (0.146) were ranked lower. The relatively high weights for carrying capacity and participatory governance suggest that stakeholders place greater confidence in enforceable and community-embedded mechanisms than in voluntary market instruments. The aggregated CR of 0.06 indicates coherent and reliable pairwise judgments. The criterion weights used above (Economic = 0.28; Socio-cultural = 0.36; Environmental = 0.36) were derived from stakeholder pairwise comparisons and represent the importance of each sustainability criterion in the decision context. Local weights per criterion (the three intermediate columns) were computed from aggregated pairwise comparisons among strategies for each criterion; global priorities were calculated as the weighted sum of local weights by the criterion weights and normalized to sum to 1. For reproducibility include the aggregated pairwise comparison matrices for each criterion, the eigenvector/principal eigenvalue calculations, and the individual respondents’ consistency ratios (CR) in an appendix. A CR < 0.10 for aggregated matrices supports the reliability of the results

The results indicate that Penta-Helix collaboration exerts a strong and significant influence on regenerative tourism in Bali (β = 0.62, t = 7.45, p < 0.001). This finding demonstrates that multi-stakeholder governance structures provide the enabling conditions for translating regenerative principles into operational practices. Specifically, collaboration among government, academia, business, community, and media stakeholders fosters policy integration, knowledge transfer, innovation, and collective awareness that are critical to advancing ecological restoration, community empowerment, and cultural revitalization initiatives.

This supports collaborative governance theory (Ansell & Gash, 2008; Bramwell & Lane, 2011), which argues that complex sustainability challenges cannot be addressed by isolated actors but require coordinated cross-sectoral engagement. It also aligns with regenerative tourism scholarship, which highlights that systemic, multi-actor collaboration is essential to move beyond harm reduction toward restoration and resilience (Miedes-Ugarte, B., & Flores-Ruiz, D., 2025, Guo., 2025). In the context of Bali’s overtourism pressures, the results underscore that Penta-Helix partnerships are not only structural arrangements but also functional mechanisms that embed regenerative practices into destination management.

H1: Penta-Helix collaboration positively influences regenerative tourism.

Hypothesis H1 is supported. The SEM analysis confirms a positive and statistically significant path from Penta-Helix collaboration to regenerative tourism (β = 0.62, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.55). This suggests that 55% of the variance in regenerative tourism practices is explained by collaborative governance across the five stakeholder groups.

Theoretically, this extends the Penta-Helix framework (Carayannis & Campbell, 2009; Baggio & Scott, 2020) by showing its empirical utility in tourism contexts marked by overtourism. Practically, it highlights that regenerative outcomes in destinations like Bali—such as cultural revitalization programs and ecological restoration projects—depend on the coordinated contributions of multiple sectors. This finding resonates with Dredge and Jamal (2015) and Hjalager (2018), who emphasize that networked governance catalyzes innovation, resilience, and systemic change in tourism.

- 2.

Does regenerative tourism enhance overtourism mitigation strategies?

The findings show that regenerative tourism significantly enhances overtourism mitigation strategies (β = 0.58, t = 6.80, p < 0.001). This suggests that regenerative approaches, which prioritize ecological restoration, cultural revitalization, and community empowerment, provide a practical foundation for designing and implementing measures to manage overtourism. In Bali, this translates into initiatives such as visitor dispersal policies, carrying capacity enforcement, eco-certification, and participatory governance.

Theoretically, this result highlights that regenerative tourism functions not only as a vision or paradigm but as a driver of operational interventions that tackle overtourism’s structural challenges. This extends overtourism research, which has often emphasized descriptive accounts of its symptoms (Koens, Postma, & Papp, 2018; Żemła, M., & Szromek, A. R., 2021; Benner, 2020), by demonstrating how regenerative principles can shape concrete mitigation tools. It also aligns with Fletcher et al. (2019) and Miedes-Ugarte, B., & Flores-Ruiz, D. (2025) who argue that regenerative tourism reorients destinations away from growth-driven models and toward systemic restoration and resilience.

H2: Regenerative tourism positively influences overtourism mitigation strategies.

Hypothesis H2 is supported. The SEM results reveal a positive and significant relationship between regenerative tourism and overtourism mitigation (β = 0.58, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.50). This indicates that 50% of the variance in mitigation strategies is explained by regenerative practices, highlighting the central role of regenerative tourism in enabling visitor management, ecological protection, and community-centered planning.

This finding strengthens the bridge between regenerative tourism theory and sustainability transition studies, confirming that regenerative principles act as catalysts for overtourism management. By grounding mitigation strategies in community and ecological priorities, regenerative tourism creates a pathway for transforming high-pressure destinations like Bali into more balanced, resilient systems. This resonates with Wang, J., & Ran, B. (2018)and Iddawala, J., & Lee, D., 2025), who emphasize that mitigation must be embedded in participatory and restorative governance structures to be effective.

- 3.

Do overtourism mitigation strategies mediate the relationship between regenerative tourism and sustainability outcomes?

The results demonstrate that overtourism mitigation strategies play a mediating role in linking regenerative tourism to economic, socio-cultural, and environmental sustainability outcomes. Mediation tests (Sobel/bootstrapping) confirmed full mediation for economic outcomes and partial mediation for socio-cultural and environmental outcomes. Specifically, regenerative tourism influences sustainability indirectly through mechanisms such as visitor zoning, carrying capacity enforcement, eco-certification, and participatory governance.

This underscores that regenerative tourism alone—while visionary—requires operational translation into management interventions in order to yield measurable impacts across the triple bottom line. Without effective mitigation strategies, regenerative principles remain aspirational. The findings extend sustainability transition theory by conceptualizing overtourism mitigation not merely as a policy endpoint but as a causal mechanism that bridges regenerative paradigms with tangible sustainability outcomes (Wang, J., & Ran, B., 2018); Iddawala, J., & Lee, D., 2025; Poetra, R.A.M & Nurjaya, I.N (2024).

H3a

:Overtourism mitigation mediates the relationship between regenerative tourism and economic sustainability.

Supported. Mitigation strategies significantly improved economic sustainability (β = 0.41, p < 0.01), including income stability and diversification. Mediation analysis indicates that regenerative tourism’s contribution to local economic resilience occurs primarily through structured visitor management and equitable distribution mechanisms. This aligns with Gössling et al. (2020), who emphasize that effective governance ensures regenerative practices generate broad-based economic benefits rather than elite capture.

H3b: Overtourism mitigation mediates the relationship between regenerative tourism and socio-cultural sustainability.

Supported. Mitigation strategies significantly influenced socio-cultural sustainability (β = 0.53, p < 0.001), with partial mediation detected. This suggests that regenerative tourism strengthens cultural authenticity and community cohesion, but the preservation of heritage and intergenerational transmission of traditions requires operational support from zoning policies, community-led tourism, and participatory governance (Richards & Wilson, 2007; UNWTO, 2018).

H3c:

Overtourism mitigation mediates the relationship between regenerative tourism and environmental sustainability.

Supported. Mitigation strategies significantly enhanced environmental sustainability (β = 0.48, p < 0.001), confirming that ecological restoration principles embedded in regenerative tourism gain effectiveness when coupled with concrete measures such as carrying capacity enforcement, biodiversity conservation, and waste reduction. This aligns with Higham et al. (2016), Mazzamuto, M., & Picone, M. (2022) and Kowarik et al. (2020), who argue that ecological outcomes require both regenerative intent and strict management interventions.

- 4.

How do overtourism mitigation strategies influence the economic, socio-cultural, and environmental dimensions of sustainability?

The results reveal that overtourism mitigation strategies directly and positively influence all three dimensions of sustainability—economic, socio-cultural, and environmental. By managing visitor flows, enforcing carrying capacity, and embedding participatory governance, mitigation strategies help rebalance tourism’s impacts across Bali’s triple bottom line. Theoretically, this confirms the triple bottom line framework (Elkington, 1998) within overtourism contexts, showing that mitigation does not involve trade-offs between economic, cultural, and ecological priorities but can simultaneously advance all three. This extends overtourism scholarship by demonstrating that proactive mitigation transforms destinations from reactive harm-reduction models toward systemic sustainability outcomes (Koens, Postma, & Papp, 2018; Gössling & Hall, 2019; Birinci, H., et al., 2025).

H4a: Overtourism mitigation positively influences economic sustainability.

Supported. Mitigation strategies significantly improved economic sustainability (β = 0.41, p < 0.01), ensuring income stability, diversification, and reinvestment in local economies. This reflects that structured visitor management can protect local livelihoods by stabilizing demand and avoiding unsustainable boom–bust cycles (Sustainable Development Goals, 2015; Gössling et al., 2020).

H4b: Overtourism mitigation positively influences socio-cultural sustainability.

Supported. Mitigation strategies exerted a strong effect on socio-cultural sustainability (β = 0.53, p < 0.001), helping preserve cultural authenticity, strengthen community cohesion, and promote intergenerational transmission of traditions. This validates findings by Richards and Wilson (2007) and Waligo et al. (2013), who argue that community-led tourism and cultural zoning enhance resilience against cultural commodification.

H4c: Overtourism mitigation positively influences environmental sustainability.

Supported. Mitigation strategies significantly enhanced environmental sustainability (β = 0.48, p < 0.001), confirming their role in biodiversity conservation, waste reduction, and water resource management. This resonates with Higham et al. (2016) ), Kowarik et al. (2020), and Mazzamuto, M., & Picone, M. (2022) who emphasize that ecological sustainability depends on both regenerative principles and enforceable policy measures.

- 5.

Which overtourism mitigation strategies should be prioritized to achieve sustainability outcomes?

To complement the SEM findings, Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) analysis was conducted with 30 purposively selected stakeholders representing the Penta-Helix groups (government, academia, business, community, and media). The analysis aimed to prioritize four mitigation strategies—carrying capacity enforcement, participatory governance, visitor zoning and dispersal, and eco-certification—based on their contributions to economic, socio-cultural, and environmental sustainability.

1. Priority ranking of mitigation strategies

Stakeholders ranked carrying capacity enforcement as the top priority (global priority = 0.332), followed closely by participatory governance (0.326). Visitor zoning and dispersal (0.196) and eco-certification (0.146) were ranked lower. The aggregated consistency ratio (CR = 0.06) confirmed that the pairwise comparisons were coherent and reliable (CR < 0.10 threshold; Saaty, 2008).

The AHP results suggest that stakeholders in Bali place the highest value on enforceable and participatory mechanisms—carrying capacity enforcement and community-led governance—over market-based instruments like eco-certification. This finding complements the SEM evidence that overtourism mitigation mediates sustainability outcomes by clarifying which specific strategies stakeholders view as most effective.

Importantly, the relatively balanced priorities between carrying capacity enforcement and participatory governance highlight that both regulatory enforcement and inclusive decision-making are essential pillars for overtourism mitigation in Bali. Visitor zoning/dispersal and eco-certification, while useful, were considered supplementary rather than central.

This ranking aligns with recent scholarship emphasizing that overtourism challenges require structural policy measures and community empowerment, rather than relying solely on voluntary or market-driven initiatives (Koens, Postma, & Papp, 2018; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018; Hoang, H. T. T et al, 2018).

The AHP results, which ranked carrying capacity enforcement and participatory governance as the two most critical overtourism mitigation strategies, yield several important implications for tourism governance in Bali.

-

Policy enforcement as a cornerstone of governance

The prioritization of carrying capacity enforcement reflects stakeholder recognition that regulatory frameworks must be strengthened and consistently applied. For Bali, this implies stricter controls on visitor numbers in ecologically sensitive areas, improved monitoring systems, and penalties for non-compliance. Strong enforcement mechanisms are particularly critical in destinations where overtourism pressures threaten environmental integrity and community well-being (Koens, Postma, & Papp, 2018).

-

Participatory governance and community legitimacy

The near-equal ranking of participatory governance underscores the importance of inclusive decision-making structures. Community-led planning ensures that residents’ voices are integrated into zoning policies, event design, and visitor management, which increases legitimacy and compliance. This reflects broader governance debates that emphasize shared stewardship and collaborative capacity-building (Bramwell & Lane, 2011; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018).

-

Balancing enforcement with empowerment

The combination of enforcement and participation suggests that neither top-down regulation nor bottom-up engagement alone is sufficient. Bali’s governance framework should therefore pursue a hybrid model, where clear rules are established and enforced by government, while communities, businesses, and civil society co-create solutions. This dual approach can reduce resistance, improve compliance, and foster a culture of shared responsibility (Antara, M & Surmarniasih, M.S, 2017; Poetra, R.A.M & Nurjaya, I.N, 2024).

-

Reframing supplementary tools

Visitor zoning and eco-certification, though ranked lower, remain valuable as supporting instruments. Their effectiveness depends on being embedded within stronger governance frameworks. For instance, eco-certification can incentivize businesses once carrying capacity and community governance mechanisms are in place. Overall, these results point to a strategic governance mix: hard regulatory enforcement combined with participatory, community-driven planning. This balance is essential for operationalizing regenerative tourism principles and ensuring that mitigation strategies translate into long-term sustainability outcomes across Bali’s economic, socio-cultural, and environmental dimensions (Mananda, I. G. P. B. S., & Sudiarta, I. N, 2024).