1. Introduction

Access to clean and safe water remains a fundamental requirement for human health, environmental sustainability, and economic development. Yet, water quality continues to deteriorate globally due to industrial effluents, agricultural runoff, urbanization, and climate-induced hydrological extremes (Ferdowsi et al., 2024). The World Health Organization estimates that contaminated drinking water causes more than half a million deaths annually, while nutrient enrichment and eutrophication drive harmful algal blooms (HABs) that compromise aquatic ecosystems and recreational use of water bodies (Karlson et al., 2021). These challenges highlight the urgent need for reliable, real-time water quality assessment systems that can support decision-making by regulators, utilities, and communities.

Traditional monitoring frameworks rely heavily on periodic grab sampling followed by laboratory-based analysis of physico-chemical and microbiological indicators. While these methods provide high accuracy and remain the regulatory standard, they are resource-intensive, laborious, and lack temporal resolution (Madrid & Zayas, 2007). Episodic sampling often fails to capture dynamic and short-lived events such as combined sewer overflows, pesticide runoff following storms, or contamination intrusions in distribution networks (Furrer et al., 2023). As a result, decision-making is frequently delayed, reducing the capacity to protect public health and ecosystems in real time.

The convergence of the Internet of Things (IoT) and machine learning (ML) offers a paradigm shift in how water quality is monitored and assessed. IoT systems employ networks of in situ sensors capable of continuously recording parameters such as turbidity, pH, conductivity, dissolved oxygen, and surrogate measures for pathogens (Essamlali et al., 2024). These systems generate high-frequency data streams that, when integrated with ML algorithms, enable predictive modeling, anomaly detection, and short-term forecasting of contamination events. ML techniques ranging from regression and classification models to advanced deep learning architectures have been applied to predict microbial contamination in bathing waters [Author, Year], detect intrusion events in drinking water networks (Himeur et al., 2021), and optimize nutrient removal in wastewater treatment processes (Essamlali et al., 2024).

Although interest in ML–IoT integration for water quality has grown rapidly over the last decade, several gaps remain in the literature. First, existing reviews are often fragmented: some focus exclusively on ML algorithms without considering sensor limitations, while others emphasize IoT architectures without exploring the analytical methods that give meaning to data (Dharmarathne et al., 2025). Second, many case studies remain context-specific, limiting generalization across geographies, water types, and regulatory environments. Third, reproducibility and comparability of results are hindered by the lack of standardized datasets, benchmarks, and evaluation protocols.

This review seeks to address these gaps by providing a comprehensive synthesis of methods, applications, and future research directions for ML–IoT systems in water quality assessment. Specifically, the objectives are to:

Categorize and critically evaluate ML approaches for key water quality monitoring tasks.

Examine IoT architectures, deployment models, and operational challenges.

Synthesize applications across domains including surface waters, groundwater, drinking water, wastewater, bathing waters, aquaculture, and coastal environments.

Identify methodological and practical gaps, particularly around data quality, reproducibility, and regulatory adoption.

Propose future research directions to advance reliability, interpretability, and scalability of ML–IoT systems.

The contribution of this paper lies in bridging methodological advances in ML with practical IoT deployments, providing an interdisciplinary framework relevant to environmental scientists, engineers, utility operators, and policymakers.

2. Methodology of Literature Selection

To ensure transparency, reproducibility, and rigor, this review followed a structured methodology consistent with guidelines for systematic literature reviews. The process involved five stages: database selection, search strategy design, application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, screening and selection, and data extraction.

2.1. Databases and Timeframe

The literature search was conducted across four major databases: Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect. These platforms were selected for their broad coverage of environmental science, engineering, and computer science publications. The primary timeframe was January 2010 to August 2025, reflecting the period during which IoT technologies and ML methods have become widely applied in environmental monitoring. However, earlier publications with seminal contributions—such as early applications of statistical modeling for water quality or foundational IoT frameworks—were also included.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy combined keywords from three conceptual categories:

Water domain: “water quality,” “drinking water,” “wastewater,” “surface water,” “groundwater,” “bathing water,” “aquaculture.”

IoT technologies: “Internet of Things,” “IoT,” “wireless sensor networks,” “remote monitoring,” “smart sensing.”

ML approaches: “machine learning,” “deep learning,” “artificial intelligence,” “predictive modeling,” “forecasting,” “anomaly detection.”

Boolean operators were applied to construct queries such as:

(“water quality” OR “drinking water” OR “wastewater” OR “aquatic monitoring”) AND (“Internet of Things” OR “IoT” OR “wireless sensors”) AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “predictive modeling”)

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- i.

-

Inclusion criteria:

Peer-reviewed journal articles, reviews, and full conference papers.

Studies reporting applications of ML techniques to IoT-enabled water quality monitoring.

Case studies or deployments with measurable performance outcomes.

Papers describing open datasets, benchmarks, or reproducible frameworks.

- ii.

-

Exclusion criteria:

Studies focused exclusively on laboratory-based sensor development without ML integration.

Articles applying ML only to simulated datasets with no link to real IoT data.

Grey literature, theses, and non-English publications.

Duplicate records across databases.

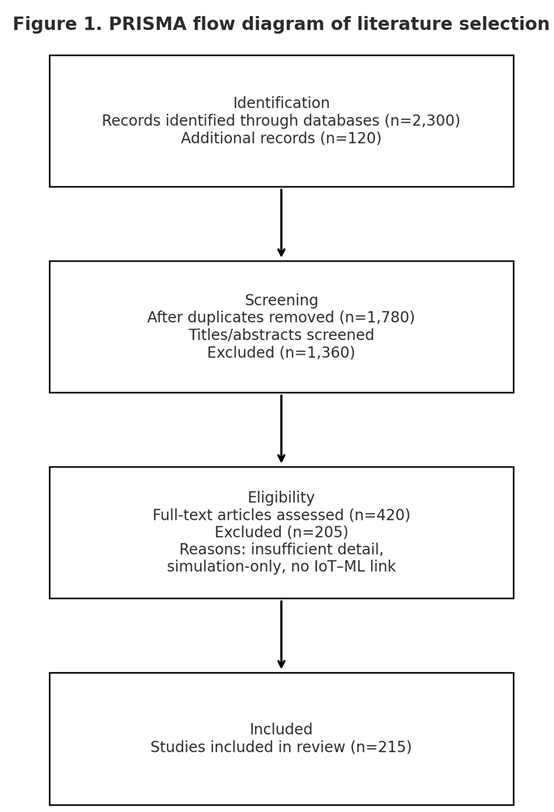

2.4. Screening Process

The initial search returned approximately 2,300 records. After removing duplicates, 1,780 unique records remained. Title and abstract screening excluded 1,360 records that did not meet inclusion criteria. A full-text review of the remaining 420 articles led to the exclusion of a further 205 studies, primarily due to insufficient methodological detail or lack of IoT–ML integration. Ultimately, 215 articles were included in the final synthesis. The process are visualized in a PRISMA-style flow diagram (Figure 1).

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each included study, the following variables were systematically extracted:

Domain of application (e.g., surface water, groundwater, drinking water).

Target indicators (turbidity, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, microbial contamination, algal pigments, etc.).

Sensor type and modality (optical, electrochemical, multi-parameter probes, hybrid systems).

IoT architecture (edge, fog, cloud; communication protocols such as LoRaWAN, NB-IoT).

ML methods applied (classical regression, decision trees, neural networks, deep learning, physics-informed).

Performance metrics (RMSE, MAE, accuracy, F1, AUROC, skill scores).

Deployment maturity (pilot-scale trials, operational utility systems, commercial deployments).

Data availability (publicly accessible datasets, proprietary industrial data).

Extracted information was tabulated and coded for thematic analysis, enabling synthesis across domains, methods, and outcomes. This structured approach ensures that the review captures both methodological diversity and practical deployment experiences.

3. Foundations

The integration of machine learning (ML) and Internet of Things (IoT) systems in water quality monitoring requires a clear understanding of three core elements: the indicators that define water quality, the technologies that enable real-time sensing, and the analytical tasks through which data are transformed into meaningful insights (Dharmarathne et al., 2025). Equally important are the challenges that arise across the data lifecycle, from acquisition to model deployment.

3.1. Water Quality Indicators

Water quality assessment depends on a diverse set of physico-chemical, biological, and microbiological indicators that collectively describe the condition of aquatic systems (Adelagun et al., 2021). Basic physico-chemical parameters, including temperature, pH, conductivity, turbidity, and dissolved oxygen, provide a baseline description of aquatic environments and are frequently used as early-warning signals of ecological disturbance. Nutrients and organic matter, particularly nitrate, ammonium, total phosphorus, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), and chemical oxygen demand (COD), are critical for assessing eutrophication risks and oxygen depletion (Shah et al., 2022). Heavy metals such as arsenic, lead, and mercury, along with other trace elements, represent toxic contaminants of regulatory concern, although their continuous monitoring remains limited by the sensitivity of current field-deployable sensors (Abo et al., 2025). Microbial indicators, including

Escherichia coli and Enterococci, are widely applied to assess drinking water safety and recreational water risks, yet direct real-time monitoring is challenging, and IoT deployments often rely on proxies such as turbidity or fluorescence (STARADUMSKYTĖ & PAULAUSKAS, 2012). Algal pigments, most notably chlorophyll-a and phycocyanin, serve as effective proxies for harmful algal blooms, which are increasingly monitored with optical sensors and remote platforms (Brenckman et al., 2025). Finally, a growing body of research addresses emerging contaminants such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and microplastics, though real-time IoT-enabled monitoring of these pollutants remains largely in the experimental stage(Brenckman et al., 2025). A key distinction between conventional laboratory methods and IoT-based approaches lies in the reliance on proxies. While laboratory analysis remains the gold standard for regulatory compliance, in situ IoT sensors provide continuous data streams that, with appropriate calibration, can detect transient events otherwise missed by periodic sampling (Ding et al., 2023).

Table 1 summarizes common indicators, their environmental relevance, and the extent to which IoT proxies are available.

3.2. IoT Sensing Technologies

The IoT paradigm relies on the deployment of diverse sensing technologies within networked systems to capture real-time data on aquatic conditions (Rastegari et al., 2023). Electrochemical sensors, which measure parameters such as pH, conductivity, and specific ions, remain among the most widely used due to their low cost and compact form. However, their performance is often constrained by drift and biofouling, necessitating frequent recalibration (Katie, 2024). Optical sensors, including nephelometers for turbidity and fluorometers for chlorophyll-a and dissolved organic matter, have been adopted extensively in field deployments because they provide rapid, non-invasive measurements (Katie, 2024). Nonetheless, they are sensitive to environmental interferences and require rigorous maintenance. Recent advances in biosensing, including microfluidic and lab-on-chip systems, are enabling the on-site detection of pathogens and toxins with high sensitivity (Hou et al., 2024). While these systems remain relatively expensive and at an early stage of deployment, they represent an important pathway toward expanding the scope of IoT-enabled monitoring. Multi-parameter sondes, which integrate a suite of electrochemical and optical sensors, have become standard in large-scale deployments, offering broader coverage of indicators at the cost of increased maintenance requirements (Erun, 2025). Remote sensing technologies, such as satellite imagery and drone-based systems, extend the spatial coverage of monitoring by providing data on parameters like turbidity and chlorophyll-a at large scales, though their temporal resolution is limited (Dritsas & Trigka, 2025). These technologies are increasingly integrated with IoT ground networks to provide complementary datasets.

According to Lombardo et al. (2021) the choice of communication protocols is central to IoT system design. Options such as LoRaWAN, Zigbee, NB-IoT, and cellular networks differ in range, bandwidth, and energy requirements. In remote catchments, long-range low-power protocols are typically favoured, whereas high-bandwidth cellular or Wi-Fi connections may be feasible in urban systems (Shukla et al., 2025).

Table 2 compares the strengths and limitations of major sensor types commonly applied in IoT-enabled water quality monitoring.

3.3. Machine Learning Tasks in Water Quality Assessment

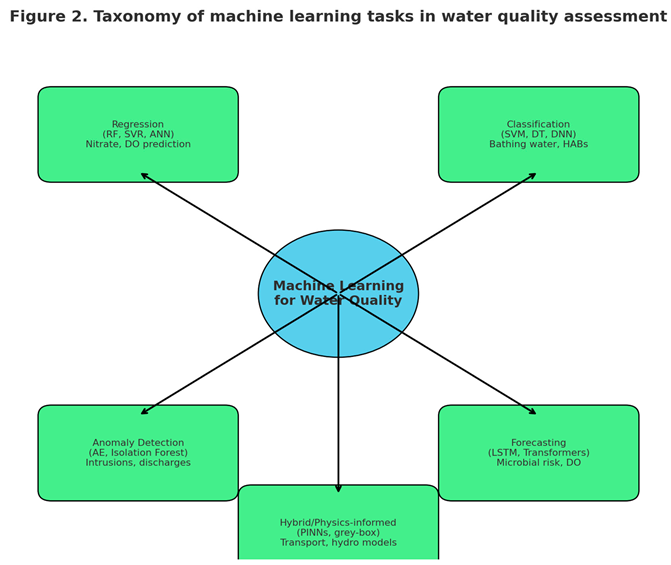

Machine learning provides the analytical backbone of IoT-based monitoring systems, enabling raw data streams to be converted into operational insights. Five categories of ML tasks dominate the field (Rahman et al., 2023). Regression models are employed to predict continuous outcomes such as nitrate concentrations or dissolved oxygen levels, often using random forests, support vector regression, or artificial neural networks. Classification models are applied where categorical decisions are required, for example, predicting whether bathing water meets microbiological safety thresholds or identifying the presence of harmful algal blooms (Ahmed et al., 2024).

Anomaly detection represents another critical application, particularly in drinking water distribution and wastewater systems where rare but high-impact contamination or intrusion events must be identified. Autoencoders, clustering methods, and isolation forests have been widely used for this purpose. Forecasting tasks are increasingly important for applications such as microbial risk prediction in recreational waters or short-term dissolved oxygen forecasting in aquaculture, with models ranging from ARIMA hybrids to advanced recurrent neural networks and Transformer-based time-series models (Yang et al., 2025). Finally, hybrid and physics-informed ML approaches are gaining traction as a means of integrating data-driven methods with mechanistic water quality models (Zhao et al., 2024). These hybrid models are particularly valuable for improving generalizability across sites and ensuring that predictions remain consistent with established hydrological and biochemical principles (Zhao et al., 2024).

A taxonomy of these ML tasks, their typical algorithms, and application domains is presented in Figure 2 and summarized in

Table 3. Together, they illustrate the diverse analytical strategies available for transforming IoT-generated data into actionable environmental intelligence.

3.4. Data Lifecycle Challenges

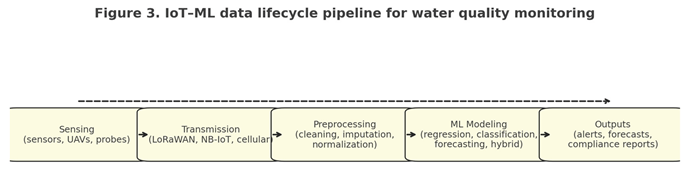

Despite rapid advances, the successful deployment of ML–IoT systems is constrained by challenges that occur throughout the data lifecycle. Data acquisition is often undermined by sensor drift, biofouling, and intermittent communication failures, which result in incomplete or noisy datasets (Okafor, 2023). Calibration across sites remains a persistent issue, as site-specific biases hinder the transferability of models trained in one location to another (Okafor et al., 2024). Data preprocessing therefore becomes critical, encompassing tasks such as missing value imputation, noise reduction, and normalization. The problem of concept drift—where statistical properties of data change over time due to seasonal variations, land use changes, or climate impacts—further complicates model deployment, often necessitating retraining or adaptive methods (Okafor et al., 2024). Uncertainty quantification remains underdeveloped in many studies, yet it is vital for regulatory acceptance and operational trust. Finally, interoperability challenges arise from the absence of standardized data formats, APIs, and metadata protocols, limiting the integration of datasets across utilities, regions, and research groups (Jørgensen et al., 2025).

Figure 3 illustrates a typical IoT–ML data pipeline, from sensing and data transmission through preprocessing, modeling, and output generation, with feedback loops for calibration and retraining. Addressing these lifecycle challenges is essential for moving beyond small-scale pilots toward robust, scalable systems capable of supporting compliance monitoring and adaptive management.

4. Machine Learning Methods for Water Quality Assessment

The application of machine learning (ML) to IoT-enabled water quality assessment spans a wide spectrum of techniques, from well-established statistical models to advanced deep learning and hybrid frameworks (Essamlali et al., 2024). Each family of methods has distinct strengths and limitations depending on the task, data availability, and operational context. In practice, the choice of model is influenced not only by predictive accuracy but also by interpretability, computational feasibility, and regulatory acceptance.

4.1. Classical Models

Classical ML approaches remain prevalent in water quality studies because of their efficiency, robustness on small datasets, and relatively high interpretability. Linear regression and its regularized variants (LASSO, Ridge, Elastic Net) are still widely applied for predicting dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and nutrient concentrations from surrogate indicators such as temperature and turbidity (Zhu et al., 2022). While simple, these models provide valuable baselines and can reveal relationships among predictors.

Decision trees and ensemble methods such as Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) are extensively used for both regression and classification tasks. RF models, for example, have been applied to estimate nitrate and ammonium concentrations from IoT sensor streams with high reliability (Jun, 2021). Ensemble methods handle non-linear relationships, provide feature importance metrics, and are relatively resistant to overfitting, making them particularly suited for environmental applications where data may be noisy or partially missing.

Support vector machines (SVM) are employed for both regression and classification, often achieving strong performance with relatively small training sets. SVM-based classifiers have been applied to distinguish safe from unsafe bathing water conditions and to detect harmful algal blooms based on multi-sensor inputs (Hassani et al., 2019). However, they can be computationally intensive for large datasets and less transparent compared to tree-based models. k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), while less common in recent studies, has been applied for anomaly detection in water distribution systems by identifying deviations from historical sensor readings. Its simplicity makes it useful for rapid prototyping, but performance declines in high-dimensional datasets (Hassani et al., 2019). Overall, classical models are advantageous where data are limited and interpretability is valued, as is often the case in regulatory monitoring programs.

4.2. Deep Learning Architectures

Deep learning has become increasingly prominent in water quality research, particularly for time-series forecasting, spatial pattern recognition, and sensor fusion. Convolutional neural networks (CNN) have been employed to process spectral and image-like data, such as hyperspectral signatures for algal pigment estimation. Recurrent neural networks (RNN), especially long short-term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent unit (GRU) models, are well-suited for time-series prediction of microbial contamination, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient dynamics (Pang et al., 2025). More recently, Transformer-based architectures have shown superior performance in capturing long-range dependencies in irregularly sampled water quality datasets. Graph neural networks (GNN) are emerging as promising tools for representing river networks, sewer systems, and distribution grids, where spatial relationships among monitoring nodes influence predictive accuracy. Despite their accuracy gains, deep learning models are often data-hungry, computationally intensive, and less interpretable than classical methods, which poses challenges for adoption in regulatory settings.

4.3. Hybrid and Physics-Informed Approaches

An important development in environmental applications is the integration of ML with mechanistic or physics-based models. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and grey-box approaches introduce domain constraints into learning processes, improving extrapolation to unseen conditions and increasing the plausibility of predictions (Cao et al., 2025). Coupling ML models with hydrodynamic simulations has enhanced predictions of nutrient transport and harmful algal blooms in estuarine environments (Busari et al., 2023). Hybrid approaches also facilitate data assimilation, where IoT sensor streams update mechanistic models in real time. These methods bridge the gap between purely empirical ML models and process-based environmental science, making them more suitable for compliance monitoring and long-term management (Busari et al., 2023). However, their deployment requires both domain expertise and computational resources, which can limit scalability in resource-constrained settings.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics and Model Validation

The choice of evaluation metrics is critical for assessing ML performance. Regression tasks typically use root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and coefficient of determination (R²) (Saeik et al., 2021). Classification studies often report accuracy, precision, recall, F1 scores, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). Forecasting tasks require skill scores that compare model predictions to baselines such as persistence or climatology (Saeik et al., 2021). A common limitation in the literature is over-reliance on random cross-validation, which can lead to inflated performance estimates due to temporal or spatial autocorrelation (Ploton et al., 2020). More robust validation strategies include blocked cross-validation, rolling-origin evaluation for time series, and leave-one-site-out validation for multi-location studies. Adoption of standardized evaluation protocols would greatly improve comparability across studies.

4.5. Robustness, Generalization, and Uncertainty

Robustness and generalization remain pressing challenges in applying ML to water quality. Models trained on data from one site or season often perform poorly when transferred to different hydrological or climatic conditions, reflecting the problem of domain shift. Adaptive and transfer learning approaches have been proposed to mitigate these issues, but their use in water quality remains limited. Handling missing data and sensor drift is also critical for robust deployment, with imputation strategies, redundancy in sensing networks, and online drift detection increasingly recommended. Uncertainty quantification is essential for operational decision-making yet underrepresented in current literature. Bayesian neural networks, ensemble modeling, and conformal prediction methods provide estimates of predictive uncertainty, which can guide risk-aware interventions by utilities and regulators (Chaulagain et al., 2025). Explicit reporting of uncertainty would improve trust and adoption of ML–IoT systems in compliance frameworks.

5. IoT Architectures and Deployment for Water Quality Monitoring

The deployment of Internet of Things (IoT) systems for water quality assessment extends beyond individual sensors to encompass communication networks, data management frameworks, and computing architectures (Jayaraman et al., 2024). Effective IoT design determines whether sensor data can be transformed into reliable, real-time information for operational and regulatory purposes. Four key dimensions are central to IoT deployment: system architecture, communication protocols, power and maintenance strategies, and cybersecurity and data integrity (Jayaraman et al., 2024).

5.1. System Architecture: Edge, Fog, and Cloud Computing

IoT systems for water quality monitoring typically adopt hierarchical architectures comprising edge, fog, and cloud layers. Edge computing involves processing data locally on sensor nodes or gateways, allowing for basic tasks such as threshold-based alarms, noise filtering, or data compression (Ahmed et al., 2025). This reduces bandwidth demands and latency, which is crucial in remote or bandwidth-limited sites. For example, dissolved oxygen monitoring in aquaculture often incorporates edge-based rules for triggering aeration when values fall below thresholds (Ahmed et al., 2025).

Fog computing refers to intermediate processing at local servers or gateways, often used for more complex tasks such as short-term forecasting or anomaly detection (Hasan et al., 2024). This balances responsiveness with computational capacity. Cloud computing, in contrast, provides centralized processing power, enabling the application of advanced ML models, long-term storage, and integration with other datasets such as hydrological or meteorological records (Ahmed et al., 2025). Most large-scale IoT deployments adopt hybrid architectures, with routine operations managed at the edge or fog layers and more resource-intensive analytics conducted in the cloud.

5.2. Communication Protocols and Networking

Reliable data transmission is a prerequisite for IoT-enabled monitoring. A range of communication technologies are available; each suited to different contexts. Low-power wide-area networks (LPWANs), such as LoRaWAN and Sigfox, provide long-range, low-bandwidth communication and are increasingly deployed in catchment-scale monitoring. Cellular networks (3G, 4G, 5G, NB-IoT) offer higher bandwidth and reliability, making them suitable for urban areas and critical infrastructure monitoring (Diane et al., 2025). Short-range protocols, such as Zigbee, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth, are appropriate for confined systems such as wastewater treatment plants where sensor density is high and power supply is available (Diane et al., 2025).

Emerging technologies, including satellite-based IoT and mesh networking, are particularly relevant for remote or data-scarce regions where terrestrial infrastructure is limited (Ali et al., 2021). The choice of protocol depends on trade-offs among range, energy consumption, cost, and environmental conditions.

5.3. Power Supply, Maintenance, and Calibration

Ensuring long-term operation of IoT systems requires careful consideration of power management and sensor maintenance. Most field-deployed sensors rely on batteries, which must be replaced or recharged at regular intervals. Energy harvesting techniques, including solar, hydrokinetic, and microbial fuel cells, are being explored to reduce reliance on manual servicing (Shaharuddin et al., 2023). Biofouling remains a major operational challenge, particularly in nutrient-rich waters (Delgado et al., 2021). Fouling can degrade signal quality, increase sensor drift, and shorten maintenance intervals. Strategies to mitigate fouling include anti-fouling coatings, wipers, and chemical cleaning routines integrated into sensor housings (Delgado et al., 2021). Calibration protocols are equally important: remote calibration and automated zero/span checks are being developed to minimize field visits while ensuring accuracy.

Operational costs remain a barrier to large-scale deployments. Multi-parameter sondes can cost thousands of dollars and require frequent servicing, while low-cost sensor networks often sacrifice accuracy for affordability. Hybrid strategies that combine high-quality reference sensors with networks of low-cost nodes, calibrated against the reference data, offer a cost-effective compromise.

5.4. Cybersecurity and Data Integrity

As IoT networks expand, the risk of cyberattacks and data manipulation grows. Potential vulnerabilities include unauthorized access to sensor nodes, spoofing of data streams, and denial-of-service attacks. In drinking water distribution systems, such breaches could have severe public health and security consequences (Singh et al., 2024). To address these risks, best practices include end-to-end encryption of data, secure firmware updates, and authentication protocols for device access. Blockchain-based approaches are being investigated to ensure tamper-proof audit trails for compliance monitoring (Singh et al., 2024). In addition, utilities are increasingly adopting resilience frameworks that combine redundancy in sensor networks with anomaly detection algorithms that flag suspicious data patterns.

5.5. Interoperability and Scalability

Beyond technical performance, IoT deployment must address interoperability across devices, platforms, and regulatory frameworks. Proprietary systems often restrict integration, limiting the ability of utilities to scale deployments or share data across jurisdictions. The adoption of open standards for data exchange, such as the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) SensorThings API, can enhance interoperability and reproducibility (Crawford, 2024). Scalability also requires modular system design, enabling networks to grow from pilot deployments to basin- or national-scale monitoring frameworks without prohibitive cost increases.

5.6. Case Examples of IoT Deployment

Case studies highlight both the promise and limitations of IoT architectures. In China, a LoRaWAN-based network covering an entire river basin provided real-time turbidity and nutrient data, feeding into predictive models for downstream drinking water plants. The system reduced contamination response times by more than 40% (Pires & Gomes, 2024). In Europe, fog-based IoT systems integrated anomaly detection in drinking water distribution networks, reducing false alarms compared to cloud-only systems while maintaining low latency (Pires & Gomes, 2024). In Norway, aquaculture farms deployed IoT sensors for oxygen, temperature, and turbidity, integrated with cloud-based ML forecasts to optimize aeration and feeding schedules. These examples demonstrate that while IoT architectures can be tailored to diverse environments, they require careful alignment of technical design, maintenance capacity, and institutional frameworks to ensure long-term success.

6. Applications of ML–IoT Systems in Water Quality Monitoring

Machine learning (ML) integrated with Internet of Things (IoT) architectures has been deployed across multiple aquatic environments, each presenting unique opportunities and challenges. Applications range from natural systems such as rivers, lakes, and coastal zones to engineered systems like drinking water networks, wastewater treatment facilities, and aquaculture. While pilot projects demonstrate significant promise, scalability and regulatory uptake vary across domains.

6.1. Surface Waters (Rivers and Lakes)

IoT–ML systems in rivers and lakes are primarily designed for pollution risk forecasting, nutrient management, and algal bloom monitoring. Rivers often face dynamic contamination events driven by rainfall, agricultural runoff, or industrial discharges. IoT networks typically deploy multi-parameter sondes measuring turbidity, conductivity, pH, and dissolved oxygen. These high-frequency datasets are analyzed with ML models such as Random Forests or Gradient Boosting to predict sediment loads, nutrient concentrations, or microbial contamination (Ngwenya et al., 2025). For example, rainfall and turbidity data have been used to train logistic regression models that forecast E. coli exceedances following storm events.

Lakes present a different challenge, particularly regarding harmful algal blooms (HABs). IoT fluorescence sensors and satellite-derived chlorophyll-a products have been integrated with LSTM networks to provide multi-day HAB forecasts. Some studies report lead times of 3–5 days with predictive accuracies above 85% (Caballero et al., 2025). Such forecasts are critical for drinking water utilities and recreational water managers. However, transferability of models across lakes remains poor because bloom dynamics are strongly influenced by local hydrodynamics, nutrient cycling, and climate variability.

6.2. Groundwater Monitoring

Groundwater is traditionally monitored through infrequent sampling, but IoT-enabled systems are beginning to enhance temporal and spatial resolution. Applications focus on nitrate leaching in agricultural aquifers, heavy metal contamination in mining regions, and salinity intrusion in coastal aquifers. IoT systems typically deploy electrochemical probes in monitoring wells, transmitting data via LPWAN protocols (García et al., 2023). Machine learning plays a key role in interpolating sparse and irregular data. Hybrid ML–geostatistical approaches (e.g., Random Forest combined with kriging) have been applied to generate continuous groundwater quality maps in near real time (García et al., 2023). In agricultural catchments, decision tree models trained on nitrate sensor data and weather variables have been used to forecast leaching risks. Despite these advances, deployments remain limited due to sensor durability in subsurface conditions, high installation costs, and difficulties in long-term maintenance. Future opportunities lie in combining IoT well data with satellite-derived soil moisture and land use information for regional-scale groundwater quality assessments.

6.3. Drinking Water Distribution Systems

Drinking water networks represent one of the most sensitive applications of IoT–ML monitoring due to the need for public health protection and regulatory compliance. Sensors measuring turbidity, chlorine residual, conductivity, and pressure are commonly deployed. IoT streams feed into anomaly detection models designed to identify contamination intrusions, pipe bursts, or backflow events. Deep learning methods, particularly autoencoders and LSTM-based anomaly detectors, have demonstrated the ability to reduce false alarms while improving detection rates compared to threshold-based monitoring (Zulkifli et al., 2022). For example, one pilot study in the United States demonstrated that autoencoder-based models could identify contamination events within 30 seconds, compared to several minutes for rule-based systems (Truong & Luong, 2024).

A critical concern in this domain is cybersecurity. IoT nodes in distribution systems represent potential attack vectors, and ML-based anomaly detection is increasingly being used to identify both environmental anomalies and malicious data manipulation (R & Jeevaa Katiravan, 2025). Integration into regulatory frameworks such as the EU Drinking Water Directive and the US Safe Drinking Water Act remains in early stages but is progressing as confidence in system reliability grows.

6.4. Wastewater Treatment Plants

IoT–ML applications in wastewater treatment are focused on process control, energy optimization, and compliance assurance. Sensors for dissolved oxygen, ammonia, COD, and turbidity are integrated into supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems. ML models are applied to forecast influent loads, optimize aeration, and predict effluent quality (Wang et al., 2024). Aeration control is a prominent case: aeration accounts for up to 60% of total plant energy costs. ML models, particularly LSTM and reinforcement learning frameworks, have been used to optimize aeration schedules, reducing energy use while maintaining effluent compliance with nitrogen and phosphorus standards (Igor Gulshin & Kuzina, 2024). Hybrid mechanistic–ML models are increasingly popular. Activated sludge models updated in real time with IoT sensor streams have improved resilience to shock loads and seasonal variability (Wang et al., 2024). However, fouling of sensors in high-solids environments remains a critical operational barrier, often requiring redundant sensing networks and frequent maintenance.

6.5. Bathing Waters and Recreational Use

Bathing waters are monitored for microbial safety under EU and US regulatory frameworks. Traditional culture-based methods for E. coli and Enterococci require 24–48 hours, creating delays in issuing advisories. IoT–ML systems aim to provide real-time proxies and short-term forecasts.

IoT probes measuring turbidity, rainfall, solar radiation, and temperature have been coupled with ML models such as Random Forests and logistic regression to predict microbial exceedances. In one case study, an ML–IoT system achieved 82% accuracy in forecasting unsafe bathing conditions during rainfall-driven events (Roy et al., 2025). Adoption remains limited because surrogate indicators may not always align with true microbial counts. However, the increasing emphasis on near real-time risk communication is driving regulatory interest. Pilot deployments in Europe have already demonstrated that IoT–ML forecasts can support compliance with the EU Bathing Water Directive, potentially transforming risk-based advisories.

6.6. Aquaculture Systems

Aquaculture has seen some of the most rapid adoption of IoT–ML systems because of the direct economic value of improved water quality management. Dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity, and temperature are continuously monitored by IoT probes, often connected to automated aeration and feeding systems (Baena-Navarro et al., 2025).

LSTM and GRU models trained on historical and real-time sensor data are widely used to forecast oxygen depletion. For example, an IoT–ML system deployed in shrimp ponds in Southeast Asia successfully predicted hypoxic events several hours in advance, enabling timely aeration and reducing mortality rates (Abdullah et al., 2024). Advanced deployments integrate multiple data streams, including meteorological forecasts, feeding schedules, and even underwater video monitoring. Reinforcement learning frameworks have been applied to optimize feeding strategies, improving feed conversion ratios by up to 15% while maintaining water quality (Abdullah et al., 2024). This makes aquaculture a strong case for the economic viability of IoT–ML adoption.

6.7. Coastal and Estuarine Systems

Coastal and estuarine environments are characterized by high spatial and temporal variability, making them challenging but critical domains for IoT–ML monitoring. IoT-enabled buoys equipped with multi-parameter sondes measure salinity, turbidity, chlorophyll, and nutrients. These datasets are often combined with meteorological, hydrodynamic, and tidal inputs for predictive modeling.

ML models, including Random Forests and LSTMs, have been applied to predict hypoxia and harmful algal bloom dynamics. For example, in the Gulf of Mexico, hybrid ML–hydrodynamic models improved the prediction of seasonal hypoxia extent compared to hydrodynamic models alone (Politikos et al., 2021). Integration of satellite data further enhances spatial coverage, allowing basin-scale assessments that inform fisheries and coastal management. However, the deployment of IoT systems in coastal environments faces challenges such as biofouling, storm damage, and salinity-driven sensor degradation. Robust sensor housings and redundancy are essential for long-term operation.

6.8. Cross-Domain Synthesis

Across these domains, IoT–ML applications demonstrate considerable potential to enhance predictive capacity, reduce monitoring latency, and support adaptive management. Engineered systems such as wastewater treatment and aquaculture have advanced most rapidly due to strong economic incentives and controlled conditions. Natural systems, particularly groundwater and coastal waters, lag due to higher technical complexity and deployment costs.

Three common themes emerge:

Data reliability remains the key constraint. Sensor fouling, drift, and communication failures continue to undermine data quality.

Uncertainty quantification is underdeveloped. Few studies provide confidence intervals, limiting trust in predictions.

Scalability depends on interoperability. Without open standards and modular architectures, scaling from pilots to regional or national systems will remain difficult.

Overall, IoT–ML systems are transitioning from experimental pilots to operational tools, but widespread adoption will require addressing these systemic barriers.

7. Knowledge Gaps and Challenges

Despite rapid advances in IoT–ML applications for water quality monitoring, significant gaps remain that limit their large-scale adoption and integration into regulatory frameworks. These challenges span technical, methodological, and institutional dimensions, and addressing them is critical for transitioning from experimental pilots to robust operational systems.

7.1. Sensor Reliability and Data Quality

One of the most persistent challenges is the reliability of IoT sensors in field deployments. Biofouling, drift, and calibration issues compromise data accuracy, particularly in nutrient-rich or high-turbidity environments. Many studies report frequent data gaps due to sensor malfunction or communication failures, leading to incomplete time series that undermine ML performance (Huang & Khabusi, 2025). Low-cost sensors are particularly prone to instability, raising concerns about their long-term suitability for compliance monitoring. Development of self-calibrating sensors, advanced anti-fouling materials, and redundancy in sensor networks are needed to improve resilience.

7.2. Data Scarcity and Imbalance

Although IoT systems generate large volumes of data, the availability of labeled datasets for supervised ML tasks remains limited. For instance, microbial contamination events in bathing waters or intrusion events in drinking water systems are rare, resulting in imbalanced datasets that bias model training (Abdulla & M. Jameel, 2023). This problem leads to overestimation of accuracy in controlled experiments and poor generalization in operational settings. Data scarcity is further exacerbated in groundwater and coastal systems, where sensors are sparse and costly to deploy (Abdulla & M. Jameel, 2023). Semi-supervised learning, transfer learning, and anomaly detection methods offer partial solutions but remain underexplored in water quality applications.

7.3. Generalization Across Sites and Conditions

Most published studies are site-specific, with models trained and validated in a single catchment, treatment plant, or aquaculture farm. When applied to different sites, performance typically degrades due to variations in hydrology, climate, land use, and infrastructure. Seasonal and interannual variability further complicate model transferability. This lack of generalization limits the scalability of IoT–ML systems for national or regional monitoring. Research into domain adaptation, physics-informed ML, and standardized benchmarking datasets is required to overcome this challenge.

7.4. Integration of Uncertainty and Interpretability

Few studies quantify uncertainty in IoT–ML predictions, despite its importance for regulatory and management decisions. Most outputs are presented as deterministic forecasts without confidence intervals, which limits trust among stakeholders. Similarly, deep learning models are often criticized as “black boxes,” hindering interpretability. Without clear explanations of model behavior, regulatory acceptance is unlikely. Incorporating Bayesian methods, ensemble modeling, and explainable AI (XAI) into water quality applications remains a critical research need.

7.5. Cybersecurity and Data Governance

The increasing reliance on IoT networks introduces vulnerabilities to cyberattacks and data manipulation. To date, only a limited number of studies explicitly address cybersecurity in water quality IoT systems. Potential threats include spoofed sensor data, unauthorized access to control systems, and denial-of-service attacks. In addition, the absence of standardized data governance frameworks impedes interoperability between platforms and across jurisdictions. Proprietary systems often restrict data sharing, creating silos that undermine scalability. Development of open standards, encryption protocols, and blockchain-based verification could help safeguard data integrity and foster trust.

7.6. Cost and Scalability Constraints

Although IoT and ML technologies are becoming more affordable, large-scale deployment remains constrained by high capital and maintenance costs. Multi-parameter sondes and spectroscopic sensors remain expensive, and frequent servicing increases operational costs. Low-cost sensor networks, while promising, often sacrifice accuracy and require extensive calibration. Most current deployments are limited to pilot projects, with limited evidence of long-term cost-effectiveness at basin or national scale. Research into hybrid systems that integrate low-cost IoT nodes with high-precision reference sensors could provide a path toward scalable deployment.

7.7. Limited Integration into Regulatory Frameworks

Despite their potential, IoT–ML systems are rarely embedded into formal monitoring programs. Regulatory agencies remain cautious, citing concerns over data reliability, model interpretability, and uncertainty. For example, most bathing water quality advisories are still based on culture-based microbiological analyses despite the availability of IoT–ML forecasting systems. Bridging this gap requires robust validation, inter-agency collaboration, and pilot programs that demonstrate regulatory equivalence or superiority. Until these systems are recognized in environmental directives, their influence will remain limited to research and pilot-scale operations.

7.8. Cross-Domain Synthesis of Challenges

Across domains, several systemic barriers emerge. First, technical reliability of sensors remains the foundation on which ML performance depends. Second, data challenges — scarcity, imbalance, and lack of standardization — constrain model development and transferability. Third, institutional factors — cybersecurity, governance, cost, and regulatory acceptance — determine whether systems move from pilots to operational use. Without progress in these areas, IoT–ML systems risk remaining experimental technologies rather than mainstream monitoring tools.

8. Future Research Directions and Opportunities

The future of IoT–ML systems in water quality monitoring lies in addressing the persistent technical, methodological, and institutional challenges that currently constrain their widespread adoption. Progress requires coordinated advances across sensor technology, data science, and governance. Beyond incremental improvements, there is an opportunity to fundamentally reimagine how environmental monitoring is designed, implemented, and integrated into decision-making frameworks.

8.1. Advancing Resilient Sensor Technologies

Improving the robustness of sensors is foundational. Many deployments fail not because of ML limitations but due to unreliable sensor data. Research must therefore prioritize anti-fouling innovations, such as bio-inspired coatings, ultraviolet self-cleaning mechanisms, or automated wipers that minimize biofilm accumulation. Equally important is the development of sensors capable of self-calibration, with built-in routines to adjust baselines remotely, reducing the need for frequent site visits. Energy autonomy is another frontier. IoT nodes that integrate solar cells, hydrokinetic turbines, or microbial fuel cells could operate for extended periods without manual recharging, a necessity for remote and inaccessible sites. Hybrid strategies that combine dense grids of low-cost sensors with a few high-quality reference sondes will likely dominate future deployments, striking a balance between affordability and accuracy.

8.2. Expanding Data Availability and Diversity

The lack of representative datasets remains a bottleneck for ML training. Future work must focus on establishing open, standardized repositories of IoT water quality time series. Such benchmark datasets, similar to ImageNet in computer vision, would enable fair comparison of algorithms and accelerate innovation. Generative models and physics-based simulators can also be used to create synthetic datasets that represent rare events, such as contamination intrusions or hypoxic crises, which are underrepresented in real-world data. Participatory sensing offers another avenue. By integrating community-collected data from citizen science initiatives with formal IoT networks, spatial coverage could be greatly expanded. To ensure comparability, standardized metadata protocols such as the OGC SensorThings API should be adopted widely, making datasets interoperable across regions and platforms (Horsburgh et al., 2025).

8.3. Improving Generalization and Transferability

One of the greatest weaknesses in current studies is the lack of model generalizability across sites and time periods. Most published models are validated within a single catchment or facility, yielding optimistic results that fail to translate elsewhere. Future research should prioritize domain adaptation and transfer learning, allowing models trained in one location to be efficiently retrained in another with minimal data. Embedding physical constraints into ML architectures represents another promising path. Physics-informed neural networks that respect conservation laws and hydrological principles can reduce overfitting and enhance plausibility. Benchmarking protocols also need reform. Rolling-origin evaluations for time series and leave-one-site-out cross-validation should replace random partitioning, providing more realistic assessments of transferability. Meta-learning approaches, in which models learn across multiple catchments or treatment plants, could further enhance adaptability.

8.4. Integrating Uncertainty Quantification and Interpretability

For IoT–ML predictions to be actionable in regulatory settings, they must include quantified uncertainty and transparent reasoning. Current studies overwhelmingly report deterministic point forecasts, a practice that undermines trust. Probabilistic methods such as Bayesian neural networks, ensemble modeling, and quantile regression should be incorporated to provide prediction intervals. Parallel advances are needed in explainable AI. Tools such as SHAP and LIME can identify which variables most strongly influence predictions, turning black-box models into interpretable systems. For instance, recent work on bathing water forecasts revealed that rainfall and turbidity were consistently the dominant drivers when explainability frameworks were applied. Future decision-support systems should embed both uncertainty and interpretability, allowing regulators to weigh predictions in light of risk tolerance and management thresholds.

8.5. Strengthening Cybersecurity and Governance

As IoT monitoring scales, the risk of cyber-physical vulnerabilities becomes increasingly significant. Few studies explicitly address how to secure water IoT networks against spoofed data, denial-of-service attacks, or unauthorized control. End-to-end encryption tailored to low-power IoT devices should become standard practice, while blockchain and distributed ledger systems offer promise for ensuring tamper-proof audit trails. Governance must advance alongside technical security. Proprietary platforms currently create silos that limit interoperability and data sharing. International frameworks for water data governance, including standardized metadata, security compliance protocols, and interoperability guidelines, will be essential for cross-border and national-scale systems.

8.6. Enhancing Cost-Effectiveness and Sustainability

Economic and environmental sustainability must be integral to future IoT–ML designs. Large-scale deployments will only be feasible if life-cycle costs, including maintenance, calibration, and replacement, are minimized. Rigorous cost–benefit analyses comparing IoT–ML with conventional monitoring are needed, not only in terms of financial savings but also in avoided pollution incidents, reduced energy use, and improved regulatory responsiveness. Environmental sustainability is equally critical. Few studies consider the ecological footprint of sensor networks, including battery waste and rare-earth material demand. Future IoT designs should prioritize modular, repairable, and recyclable devices. Linking water quality innovation with circular economy principles would ensure that scaling IoT does not introduce new environmental burdens.

8.7. Pathways to Regulatory Integration

Perhaps the most decisive frontier is regulatory acceptance. Despite promising results, IoT–ML systems are rarely embedded in official compliance frameworks. To build credibility, large-scale pilot programs must be undertaken where IoT–ML predictions directly inform bathing water advisories, wastewater discharge permits, or drinking water safety protocols. Inter-laboratory validation studies comparing IoT–ML forecasts with traditional laboratory results are essential to demonstrate equivalence. Legal and liability frameworks must also evolve, clarifying responsibility when automated predictions guide interventions. Finally, capacity building is vital. Regulators and utility operators will need training not only in sensor maintenance but also in interpreting ML outputs, uncertainty intervals, and data dashboards.

8.8. Cross-Cutting Opportunities

Beyond addressing specific challenges, several transformative opportunities lie ahead. One is the integration of IoT–ML with Earth observation data from satellites and radar, enabling multi-scale monitoring that links basin-level drivers with in situ dynamics. Another is the rise of digital twins for water systems, dynamic virtual replicas of rivers, lakes, or treatment plants that update continuously with IoT and ML inputs. These tools could allow scenario testing and real-time management interventions. Finally, IoT–ML can converge with emerging technologies such as autonomous drones for water sampling, blockchain for transparent reporting, and climate models for adaptive management. These cross-cutting opportunities position IoT–ML not merely as incremental monitoring tools but as central pillars in the digital transformation of water resource management.

8.9. Synthesis

The trajectory of IoT–ML research indicates a clear transition from isolated pilots to integrated, large-scale deployments. Achieving this transformation requires simultaneous advances in resilient sensor hardware, methodological rigor, and governance frameworks. Progress in one dimension without the others will be insufficient. A future in which IoT–ML systems are trusted components of regulatory infrastructure is possible, but only if uncertainty, interpretability, sustainability, and security are prioritized alongside accuracy. If realized, such systems could fundamentally change how societies monitor, predict, and protect water resources in an era of increasing environmental stress.

9. Conclusion and Policy Implications

The integration of machine learning and Internet of Things technologies into water quality monitoring represents a significant shift in how aquatic environments are observed and managed. Evidence from diverse domains — rivers, lakes, groundwater, drinking water networks, wastewater treatment plants, bathing waters, aquaculture, and coastal systems — demonstrates the ability of IoT–ML systems to provide continuous, high-resolution data and predictive insights that far exceed the capabilities of traditional monitoring. These advances can improve responsiveness to contamination events, optimize operational decisions, and support adaptive management under conditions of increasing environmental stress. At the same time, this review highlights critical barriers that prevent widespread adoption. Technical challenges include sensor biofouling, calibration drift, data gaps, and energy supply limitations. Methodological issues persist around data scarcity, generalization across sites, lack of uncertainty quantification, and limited interpretability of deep learning models. Institutional barriers — particularly high costs, fragmented governance, cybersecurity risks, and the absence of regulatory frameworks — remain decisive in determining whether IoT–ML systems can transition from pilot projects to mainstream monitoring tools.

The policy implications are clear. Regulatory agencies should begin to recognize the value of IoT–ML forecasts as complements, and eventually partial replacements, for conventional laboratory analyses. This will require structured pilot programs, inter-laboratory validation, and the development of legal frameworks for accountability in automated decision-making. Public–private partnerships may be essential to finance large-scale infrastructures, while international cooperation will be needed to standardize data formats, metadata, and interoperability protocols. Capacity building among regulators and utility staff must also be prioritized to ensure that the technical and interpretive skills required for IoT–ML adoption are widely available.

Looking forward, the convergence of resilient sensor hardware, advanced ML architectures, and robust governance frameworks offers an opportunity to transform water quality monitoring from a reactive to a proactive discipline. If the research priorities identified in this review are addressed, IoT–ML systems could become trusted regulatory tools, enabling real-time protection of public health, safeguarding of ecosystems, and more efficient management of water resources. Achieving this vision will demand sustained collaboration between scientists, engineers, policymakers, and industry. The stakes are high: with climate change, population growth, and pollution pressures intensifying, the capacity to predict and prevent water quality crises is no longer optional but essential.

Authors’ Contributions

The sole author designed, analyzed, interpreted and prepared the manuscript.

Funding

Author hereby declares that NO generative AI technologies such as Large Language Models (ChatGPT, COPILOT, etc.) and text-to-image generators have been used during the writing or editing of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the valuable insights shared by peers and researchers working in water quality management and environmental modeling, whose studies informed this review. gratitude is also extended to the broader scientific community advancing research in internet of things and machine learning applications for environmental monitoring. This work was conducted independently and did not receive specific funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Author has declared that they have no known competing financial interests OR non-financial interests OR personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abdulla, A. R., & M. Jameel, N. G. (2023). A Review on IoT Intrusion Detection Systems Using Supervised Machine Learning: Techniques, Datasets, and Algorithms. UHD Journal of Science and Technology, 7(1), 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A. F., Man, H. C., Mohammed, A., Karim, M. M. A., Yunusa, S. U., & Jais, N. A. B. M. (2024). Charting the aquaculture internet of things impact: Key applications, challenges, and future trend. Aquaculture Reports, 39, 102358. [CrossRef]

- Abo, L. D., Areti, H. A., Jayakumar, M., Rangaraju, M., & Subashini, S. (2025). Nanobiomaterials-enabled sensors for heavy metal detection and remediation in wastewater systems: advances in synthesis, characterization, and environmental applications. Results in Engineering, 27, 105694. [CrossRef]

- Adelagun, R. O. A., Edet Etim, E., & Emmanuel Godwin, O. (2021). Application of Water Quality Index for the Assessment of Water from Different Sources in Nigeria. Promising Techniques for Wastewater Treatment and Water Quality Assessment. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. A., Sayed, S., Abdoulhalik, A., Moutari, S., & Oyedele, L. (2024). Applications of machine learning to water resources management: A review of present status and future opportunities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 441, 140715. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. F., Shanjana Shuravi Shawon, Shaila Afrin, Rafa, S. J., Hoque, M., & Gandomi, A. H. (2025). Optimising Internet of Things (IoT) Performance Through Cloud, Fog and Edge Computing Architecture. IET Wireless Sensor Systems, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Ali, O., Ishak, M. K., & Bhatti, M. K. L. (2021). Emerging IoT domains, current standings and open research challenges: a review. PeerJ Computer Science, 7, e659. [CrossRef]

- Baena-Navarro, R., Carriazo-Regino, Y., Torres-Hoyos, F., & Pinedo-López, J. (2025). Intelligent Prediction and Continuous Monitoring of Water Quality in Aquaculture: Integration of Machine Learning and Internet of Things for Sustainable Management. Water, 17(1), 82. [CrossRef]

- Brenckman, C. M., Parameswarappa Jayalakshmamma, M., Pennock, W. H., Ashraf, F., & Borgaonkar, A. D. (2025). A Review of Harmful Algal Blooms: Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Prevention Methods. Water, 17(13), 1980. [CrossRef]

- Busari, I., Sahoo, D., Harmel, R. D., & Haggard, B. E. (2023). A Review of Machine Learning Models for Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring in Freshwater Systems. Journal of Natural Resources and Agricultural Ecosystems, 1(2), 63–76. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, C. B., Martins, V. S., Paulino, R. S., Butler, E., Sparks, E., Lima, T. M., & Novo, E. M. L. M. (2025). The need for advancing algal bloom forecasting using remote sensing and modeling: Progress and future directions. Ecological Indicators, 172, 113244. [CrossRef]

- Cao, C., Debnath, R., & Alvarez, R. M. (2025). Physics-based machine learning for predicting urban air pollution using decadal time series data. Environmental Research Communications. [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S., Lamichhane, M., & Chaulagain, U. (2025). A review of current trends, challenges, and future perspectives in machine learning applications to water resources in Nepal. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 18, 100678. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C. (2024). Protocol power: Matter, IoT interoperability, and a critique of industry self-regulation. Internet Policy Review, 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A., Briciu-Burghina, C., & Regan, F. (2021). Antifouling Strategies for Sensors Used in Water Monitoring: Review and Future Perspectives. Sensors, 21(2), 389. [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathne, G., Abekoon, A. M. S. R., Bogahawaththa, M., Alawatugoda, J., & Meddage, D. P. P. (2025). A review of machine learning and internet-of-things on the water quality assessment: Methods, applications and future trends. Results in Engineering, 26, 105182. [CrossRef]

- Diane, A., Diallo, O., & El. (2025). A systematic and comprehensive review on low power wide area network: characteristics, architecture, applications and research challenges. Discover Internet of Things, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Ding, S., Ward, H., & Tukker, A. (2023). How Internet of Things can influence the sustainability performance of logistics industries – a Chinese case study. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain, 6, 100094. [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E., & Trigka, M. (2025). Remote Sensing and Geospatial Analysis in the Big Data Era: A Survey. Remote Sensing, 17(3), 550–550. [CrossRef]

- Erun. (2025). Multiparameter Sondes: Essential Tools for Water Quality Monitoring. Erunwas.com. https://www.erunwas.com/news-detail/id-164.html.

- Essamlali, I., Nhaila, H., & Khaili, M. E. (2024). Advances in machine learning and IoT for water quality monitoring: A comprehensive review. Heliyon, 10(6), e27920–e27920. [CrossRef]

- Ferdowsi, A., Piadeh, F., Behzadian, K., Mousavi, S.-F., & Ehteram, M. (2024). Urban water infrastructure: A critical review on climate change impacts and adaptation strategies. Urban Climate, 58, 102132. [CrossRef]

- Furrer, V., Mutzner, L., Singer, H., & Ort, C. (2023). Micropollutant concentration fluctuations in combined sewer overflows require short sampling intervals. Water Research X, 21, 100202–100202. [CrossRef]

- García, J., Leiva-Araos, A., Diaz-Saavedra, E., Moraga, P., Pinto, H., & Yepes, V. (2023). Relevance of Machine Learning Techniques in Water Infrastructure Integrity and Quality: A Review Powered by Natural Language Processing. Applied Sciences, 13(22), 12497. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F., Nassereldin Ahmed Kabashi, Saleh, T., Alam, M. Z., Wahab, M. F., & Nour, A. H. (2024). WATER QUALITY MONITORING USING MACHINE LEARNING AND IOT: A REVIEW. 8(2), 32–54. [CrossRef]

- Hassani, H., Silva, E. S., Combe, M., Andreou, D., Ghodsi, M., Yeganegi, M. R., & Gozlan, R. E. (2019). A Support Vector Machine Based Approach for Predicting the Risk of Freshwater Disease Emergence in England. Stats, 2(1), 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y., Ghanem, K., Alsalemi, A., Bensaali, F., & Amira, A. (2021). Artificial intelligence based anomaly detection of energy consumption in buildings: A review, current trends and new perspectives. Applied Energy, 287(1), 116601. [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, J. S., Lippold, K., & Slaugh, D. L. (2025). Adapting OGC’s SensorThings API and data model to support data management and sharing for environmental sensors. Environmental Modelling & Software, 183, 106241. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., Liu, Z., Huang, H., Lou, C., Sun, Z., Liu, X., Pang, J., Ge, S., Wang, Z., Zhou, W., & Liu, H. (2024). Biosensor-Based Microfluidic Platforms for Rapid Clinical Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria. Advanced Functional Materials. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-P., & Khabusi, S. P. (2025). Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) Advances in Aquaculture: A Review. Processes, 13(1), 73–73. [CrossRef]

- Igor Gulshin, & Kuzina, O. (2024). Optimization of Wastewater Treatment Through Machine Learning-Enhanced Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition: A Case Study of Granular Sludge Process Stability and Predictive Control. Automation, 6(1), 2–2. [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, W. A., Mei Ting, T., I. Hamidun, M. F., Che Kamarudin, A. H., Wu, W., Sultan, J., Alsewari, A. A., & Ali, M. A. H. (2024). Development of LoRaWAN-based IoT system for water quality monitoring in rural areas. Expert Systems with Applications, 242, 122862. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, P., Kothalam Krishnan Nagarajan, Pachaivannan Partheeban, & Krishnamurthy, V. (2024). Critical review on water quality analysis using IoT and machine learning models. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 4(1), 100210–100210. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, B. N., Gunasekaran, S. S., & Ma, Z. G. (2025). Impact of EU Laws on AI Adoption in Smart Grids: A Review of Regulatory Barriers, Technological Challenges, and Stakeholder Benefits. Energies, 18(12), 3002. [CrossRef]

- Jun, M.-J. (2021). A comparison of a gradient boosting decision tree, random forests, and artificial neural networks to model urban land use changes: the case of the Seoul metropolitan area. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 35(11), 2149–2167. [CrossRef]

- Karlson, B., Andersen, P., Arneborg, L., Cembella, A., Eikrem, W., John, U., West, J. J., Klemm, K., Kobos, J., Lehtinen, S., Lundholm, N., Mazur-Marzec, H., Naustvoll, L., Poelman, M., Provoost, P., De Rijcke, M., & Suikkanen, S. (2021). Harmful algal blooms and their effects in coastal seas of Northern Europe. Harmful Algae, 102, 101989. [CrossRef]

- Katie, B. (2024). Internet of Things (IoT) for Environmental Monitoring. International Journal of Computing and Engineering, 6(3), 29–42. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, A., Parrino, S., Peruzzi, G., & Pozzebon, A. (2021). LoRaWAN vs NB-IoT: Transmission Performance Analysis within Critical Environments. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Madrid, Y., & Zayas, Z. P. (2007). Water sampling: Traditional methods and new approaches in water sampling strategy. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 26(4), 293–299. [CrossRef]

- Ngwenya, B., Paepae, T., & Bokoro, P. N. (2025). Monitoring ambient water quality using machine learning and IoT: A review and recommendations for advancing SDG indicator 6.3.2. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 73, 107664. [CrossRef]

- Okafor, N. (2023). Advances and Challenges in IoT Sensors Data Handling and Processing in Environmental Monitoring Systems. [CrossRef]

- Okafor, N., Ingle, R., Matthew, U. O., Saunders, M., & Delaney, D. T. (2024). Assessing and Improving IoT Sensor Data Quality in Environmental Monitoring Networks: A Focus on Peatlands. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 11(24), 40727–40742. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z., Zhou, Z., Fu, J., Jiang, W., Qin, X., & Sun, M. (2025). Deep learning-based remote sensing retrieval of inland water quality: A review. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 61, 102759. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Patel, K., & Lee, W. H. (2024). Recent advances in algal bloom detection and prediction technology using machine learning. The Science of the Total Environment, 938, 173546–173546. [CrossRef]

- Pires, L. M., & Gomes, J. (2024). River Water Quality Monitoring Using LoRa-Based IoT. Designs, 8(6), 127. [CrossRef]

- Ploton, P., Mortier, F., Réjou-Méchain, M., Barbier, N., Picard, N., Rossi, V., Dormann, C., Cornu, G., Viennois, G., Bayol, N., Lyapustin, A., Gourlet-Fleury, S., & Pélissier, R. (2020). Spatial validation reveals poor predictive performance of large-scale ecological mapping models. Nature Communications, 11(1), 4540. [CrossRef]

- Politikos, D. V., Petasis, G., & Katselis, G. (2021). Interpretable machine learning to forecast hypoxia in a lagoon. Ecological Informatics, 66, 101480. [CrossRef]

- R, S. A., & Jeevaa Katiravan. (2025). Enhancing anomaly detection and prevention in Internet of Things (IoT) using deep neural networks and blockchain based cyber security. Scientific Reports, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Md. S., Ghosh, T., Aurna, N. F., Kaiser, M. S., Anannya, M., & Hosen, A. S. M. S. (2023). Machine learning and internet of things in industry 4.0: A review. Measurement: Sensors, 28, 100822. [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, H., Nadi, F., Lam, S. S., Ikhwanuddin, M., Kasan, N. A., Rahmat, R. F., & Mahari, W. A. W. (2023). Internet of Things in aquaculture: A review of the challenges and potential solutions based on current and future trends. Smart Agricultural Technology, 4, 100187. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S. C., Islam, M. A., Sarkar, R., Sarkar, R. R., Jibon, F. A., & Naznin, L. (2025). A Study of Water Quality Monitoring System With Internet of Things and Machine Learning Regression Techniques. Cureus Journal of Computer Science. [CrossRef]

- Saeik, F., Avgeris, M., Spatharakis, D., Santi, N., Dechouniotis, D., Violos, J., Leivadeas, A., Athanasopoulos, N., Mitton, N., & Papavassiliou, S. (2021). Task offloading in Edge and Cloud Computing: A survey on mathematical, artificial intelligence and control theory solutions. Computer Networks, 195, 108177. [CrossRef]

- Shah, N. W., Baillie, B. R., Bishop, K., Ferraz, S., Högbom, L., & Nettles, J. (2022). The effects of forest management on water quality. Forest Ecology and Management, 522(120397), 120397. [CrossRef]

- Shaharuddin, S., Abdul Maulud, K. N., Syed Abdul Rahman, S. A. F., Che Ani, A. I., & Pradhan, B. (2023). The Role of IoT Sensor in Smart Building Context for Indoor Fire Hazard scenario: a Systematic Review of Interdisciplinary Articles. Internet of Things, 22, 100803. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, B. K., Ruchi Saraswat, Agarwal, N., Singh, H. K., & Verma, S. (2025). A Comparative Study of IoT-Based Water Quality Monitoring Systems (IoT-WQMS) and the Potential of Machine Learning in Water Quality Assessment. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., Buyya, R., & Kim, H. (2024). Securing Cloud-Based Internet of Things: Challenges and Mitigations. Sensors, 25(1), 79–79. [CrossRef]

- STARADUMSKYTĖ, D., & PAULAUSKAS, A. (2012). Indicators of microbial drinking and recreational water quality. Biologija, 58(1). [CrossRef]

- Truong, A. M., & Luong, H. Q. (2024). A non-destructive, autoencoder-based approach to detecting defects and contamination in reusable food packaging. Current Research in Food Science, 8, 100758. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A., Li, H., He, Z., Tao, Y., Wang, H., Yang, M., Savic, D., Daigger, G. T., & Ren, N. (2024). Digital Twins for Wastewater Treatment: A Technical Review. Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Behzadian, K., Coleman, C., Holloway, T. G., & Campos, L. C. (2025). Application of AI-based techniques for anomaly management in wastewater treatment plants: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 392, 126886. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Wang, H., Bai, M., Xu, Y., Dong, S., Rao, H., & Ming, W. (2024). A Comprehensive Review of Methods for Hydrological Forecasting Based on Deep Learning. Water, 16(10), 1407–1407. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M., Wang, J., Yang, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Ren, H., Wu, B., & Ye, L. (2022). A review of the application of machine learning in water quality evaluation. Eco-Environment & Health, 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, C. Z., Garfan, S., Talal, M., Alamoodi, A. H., Alamleh, A., Ahmaro, I. Y. Y., Sulaiman, S., Ibrahim, A. B., Zaidan, B. B., Ismail, A. R., Albahri, O. S., Albahri, A. S., Soon, C. F., Harun, N. H., & Chiang, H. H. (2022). IoT-Based Water Monitoring Systems: A Systematic Review. Water, 14(22), 3621. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Common water quality indicators, environmental relevance, and IoT monitoring potential.

Table 1.

Common water quality indicators, environmental relevance, and IoT monitoring potential.

| Indicator category |

Example parameters |

Environmental significance |

IoT sensor approaches |

Limitations in IoT deployment |

| Basic physico-chemical |

Temperature, pH, electrical conductivity, turbidity, dissolved oxygen |

Provide baseline assessment of aquatic conditions; early warning signals of stress or contamination |

Electrochemical probes (pH, conductivity); optical sensors (turbidity, DO via luminescence); multiparameter sondes |

Sensor drift, biofouling, need for frequent recalibration |

| Nutrients and organic matter |

Nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, total phosphorus, BOD, COD |

Key drivers of eutrophication and hypoxia; critical for wastewater and agricultural runoff monitoring |

Ion-selective electrodes; optical absorbance sensors; surrogate proxies (e.g., UV absorbance for organic load) |

Limited sensitivity at low concentrations; calibration required for site-specific conditions |

| Heavy metals and trace elements |

Lead, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, chromium, zinc |

Chronic toxic effects on human health and ecosystems; regulated at low thresholds |

Emerging electrochemical sensors; biosensors under development; most monitoring still laboratory-based |

IoT-ready field sensors not yet reliable for trace detection; interference effects common |

| Microbiological indicators |

Escherichia coli, Enterococci, total coliforms |

Primary indicators for drinking water safety and recreational water compliance |

Fluorescence-based proxies (e.g., turbidity, tryptophan-like fluorescence); biosensors in pilot use |

Indirect proxies lack specificity; pathogen detection requires confirmatory laboratory analysis |

| Algal pigments and toxins |

Chlorophyll-a, phycocyanin, cyanotoxins |

Proxies for harmful algal blooms; relevant for aquaculture, lakes, and reservoirs |

Fluorescence sensors, hyperspectral probes, drone and satellite remote sensing |

Calibration challenges across sites; interferences from suspended solids |

| Emerging contaminants |

Pharmaceuticals, pesticides, microplastics |

Growing concern in environmental and public health; linked to wastewater and diffuse pollution |

Experimental IoT biosensors and spectroscopic systems; currently limited to lab and pilot studies |

Immature technology, limited field deployment, high cost |

Table 2.

IoT sensor technologies for water quality monitoring.

Table 2.

IoT sensor technologies for water quality monitoring.

| Sensor type |

Typical parameters measured |

Advantages |

Limitations and operational challenges |

| Electrochemical |

pH, electrical conductivity, redox potential, nitrate, ammonium, chloride |

Compact, low cost, and widely available; suitable for long-term deployments |

Susceptible to drift and fouling; require regular calibration and maintenance |

| Optical |

Turbidity, chlorophyll-a, dissolved organic matter, phycocyanin |

Non-invasive, rapid response, high sensitivity for algal proxies |

Performance affected by suspended solids and biofouling; calibration required |

| Biosensors and lab-on-chip systems |

Pathogens, cyanotoxins, pesticides, pharmaceuticals |

High specificity, rapid on-site detection potential |

Expensive and technologically immature; limited deployment in real environments |

| Multi-parameter sondes |

DO, turbidity, pH, temperature, conductivity, nutrients (various combinations) |

Comprehensive monitoring capability in single unit; robust for field use |

High capital and operational cost; maintenance-intensive in long-term deployments |

| Remote sensing and UAVs |

Chlorophyll-a, turbidity, surface temperature, suspended solids |

Large spatial coverage; valuable for lakes, reservoirs, and coastal systems |

Limited temporal resolution; require ground-truth calibration; indirect proxies |

Table 3.

Mapping of ML tasks to water quality applications.

Table 3.

Mapping of ML tasks to water quality applications.

| ML task |

Common algorithms applied |

Example applications in water quality monitoring |

Key strengths |

Key limitations |

| Regression |

Random Forest regression, support vector regression, artificial neural networks, gradient boosting |

Prediction of continuous variables such as nitrate concentration, dissolved oxygen, or biochemical oxygen demand |

Handles continuous prediction tasks; adaptable to multi-parameter inputs |

Performance depends on quality of calibration data; sensitive to concept drift |

| Classification |