Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

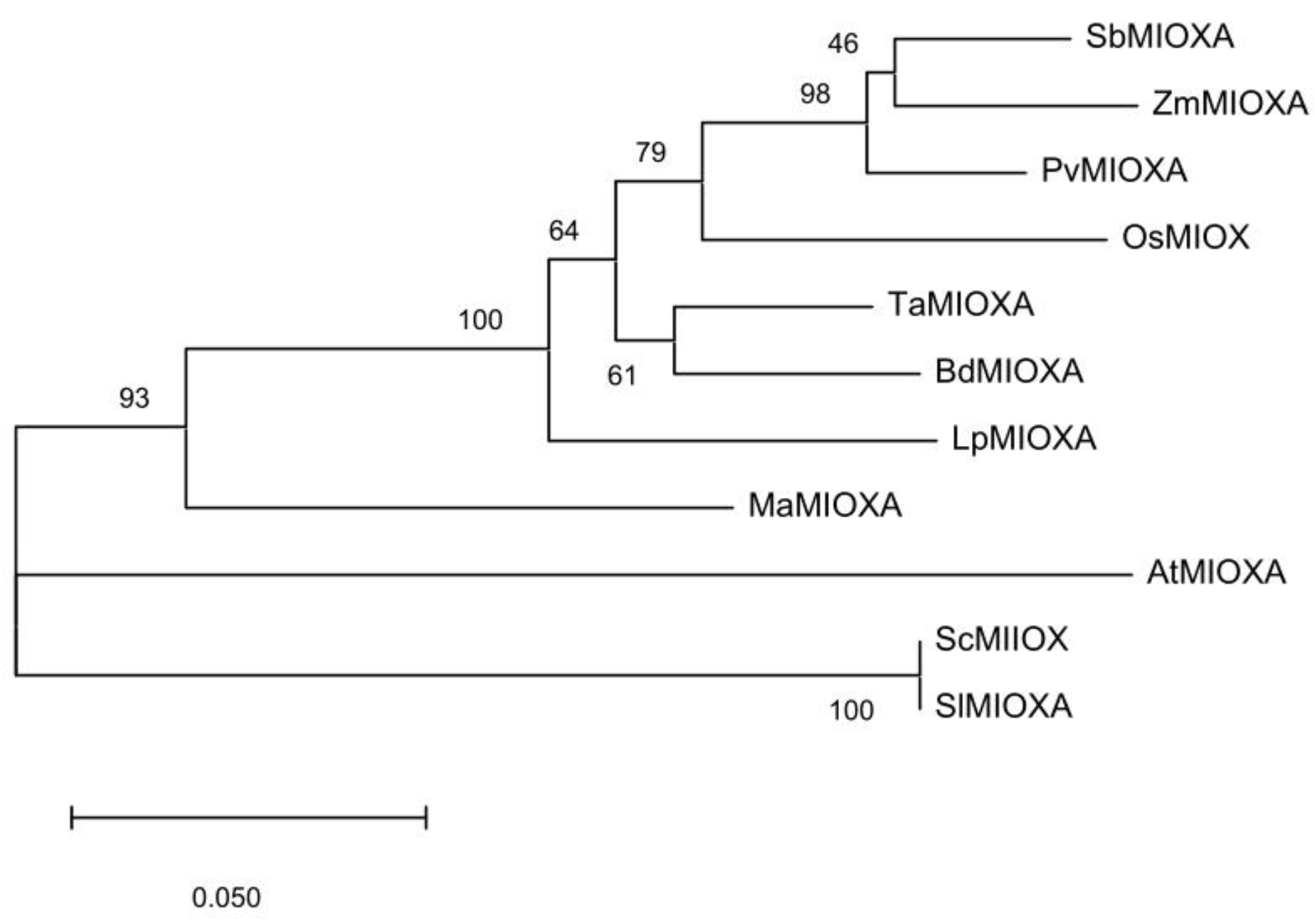

2.1. Gene Sequence Information of Inositol Oxidase

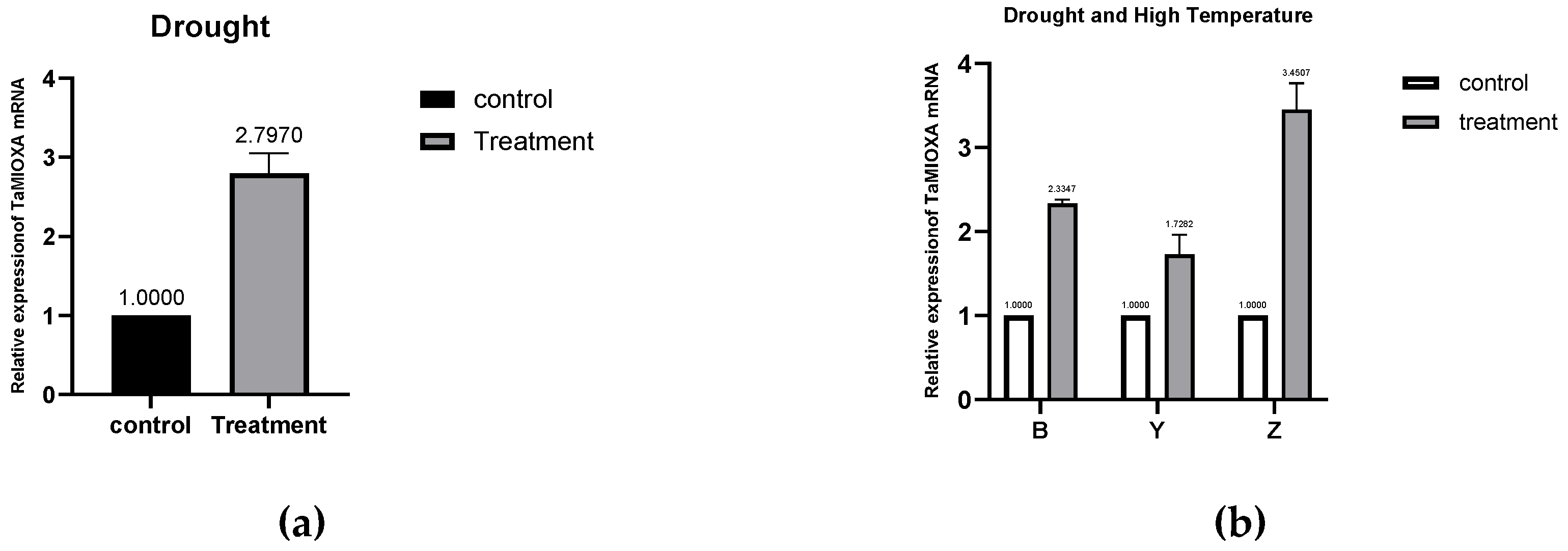

2.2. Changes in Inositol Oxidase Transcription Level Under Drought and High-Temperature Stress

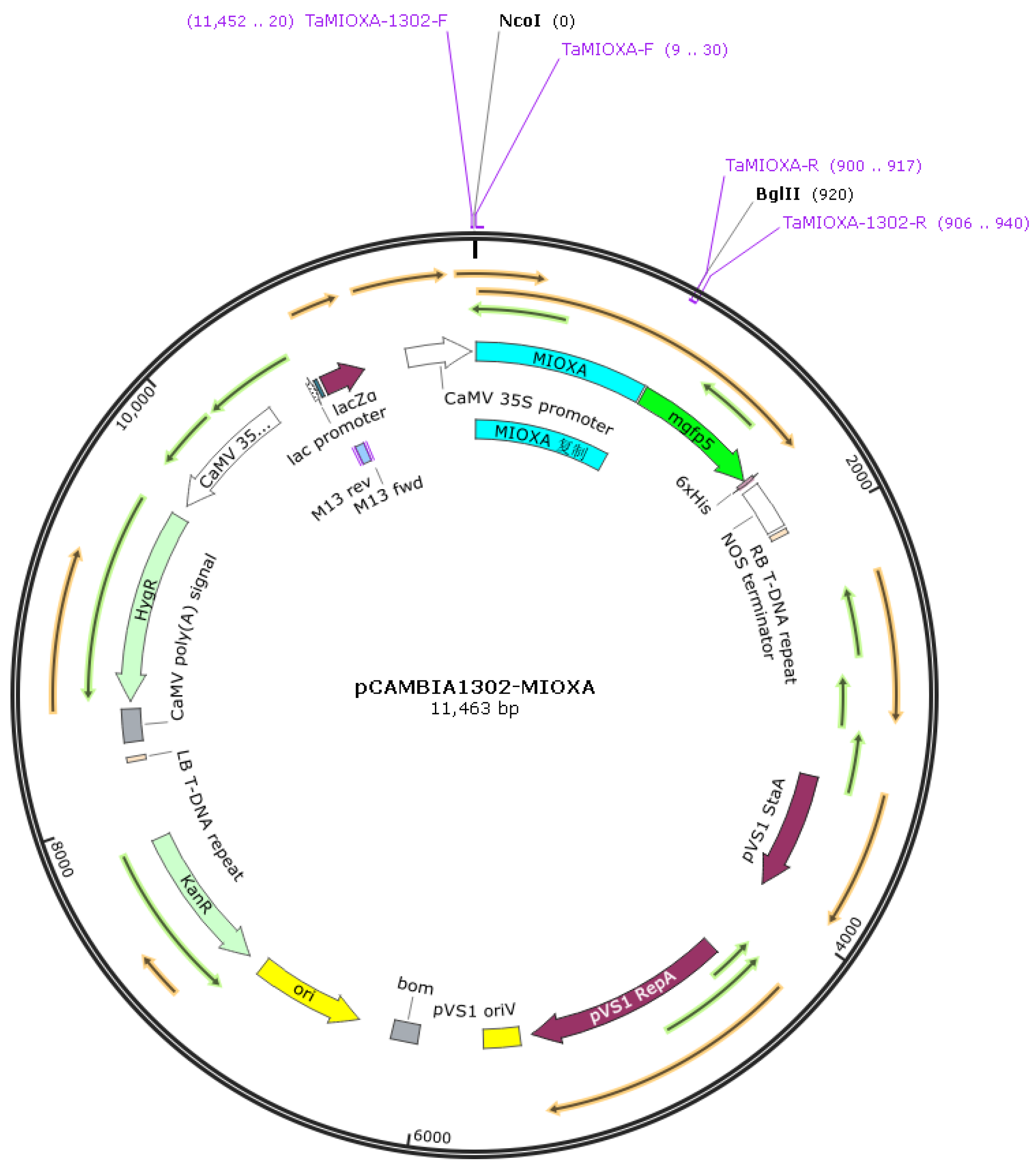

2.3. Construction of W

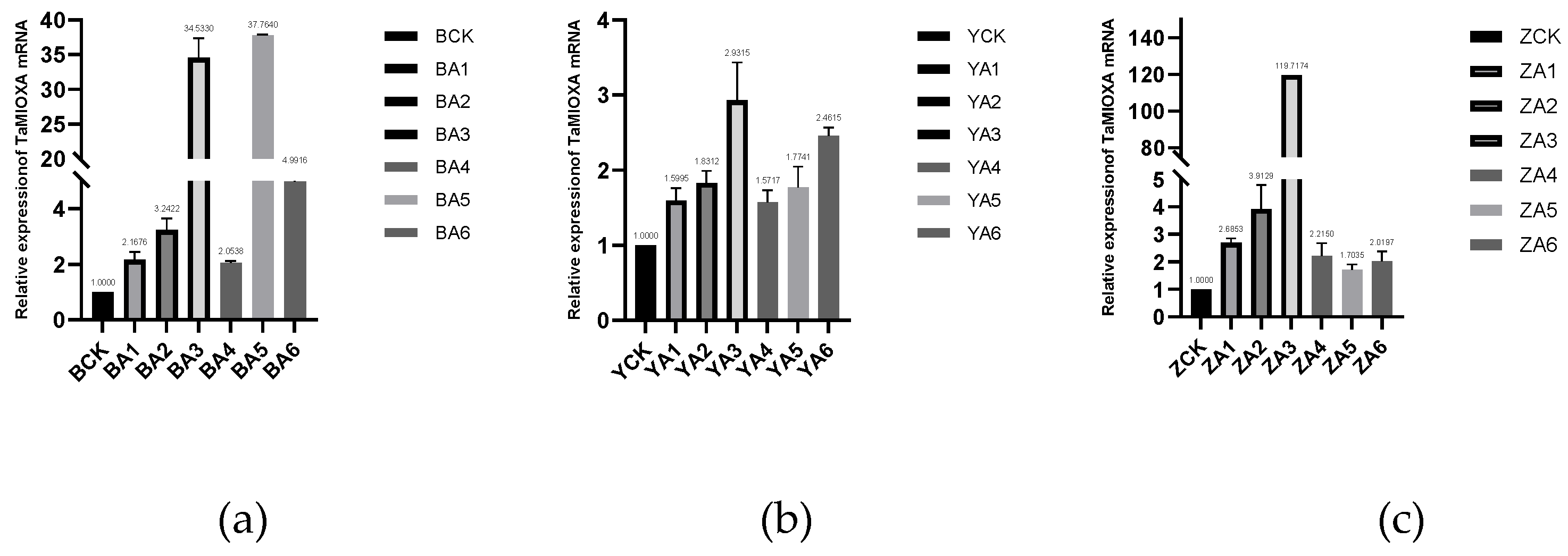

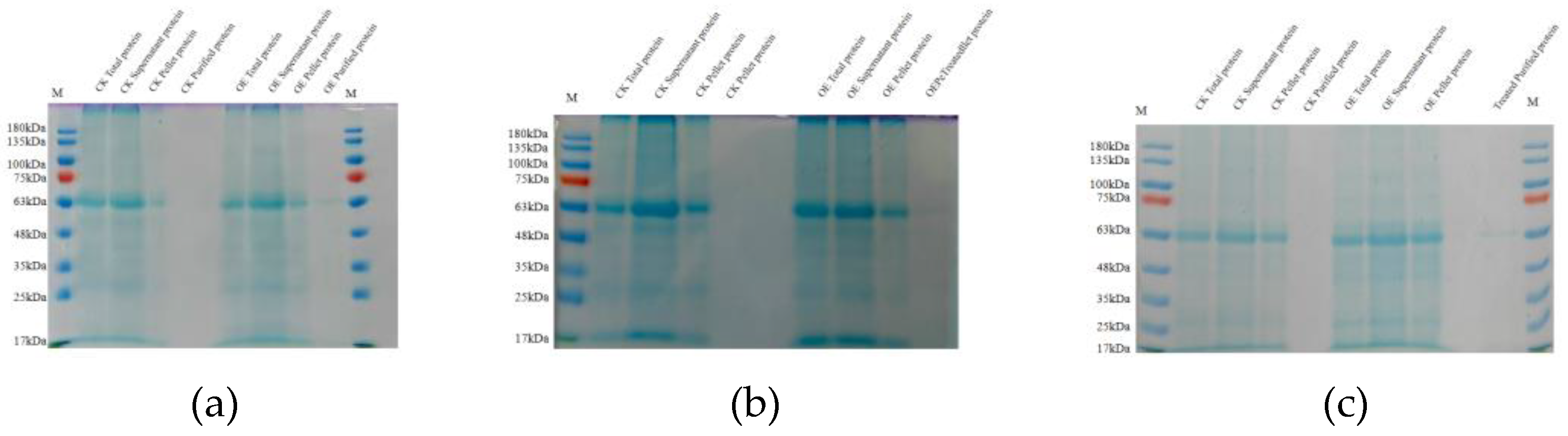

2.4. Detection of Various Indicators of Overexpressing Strains

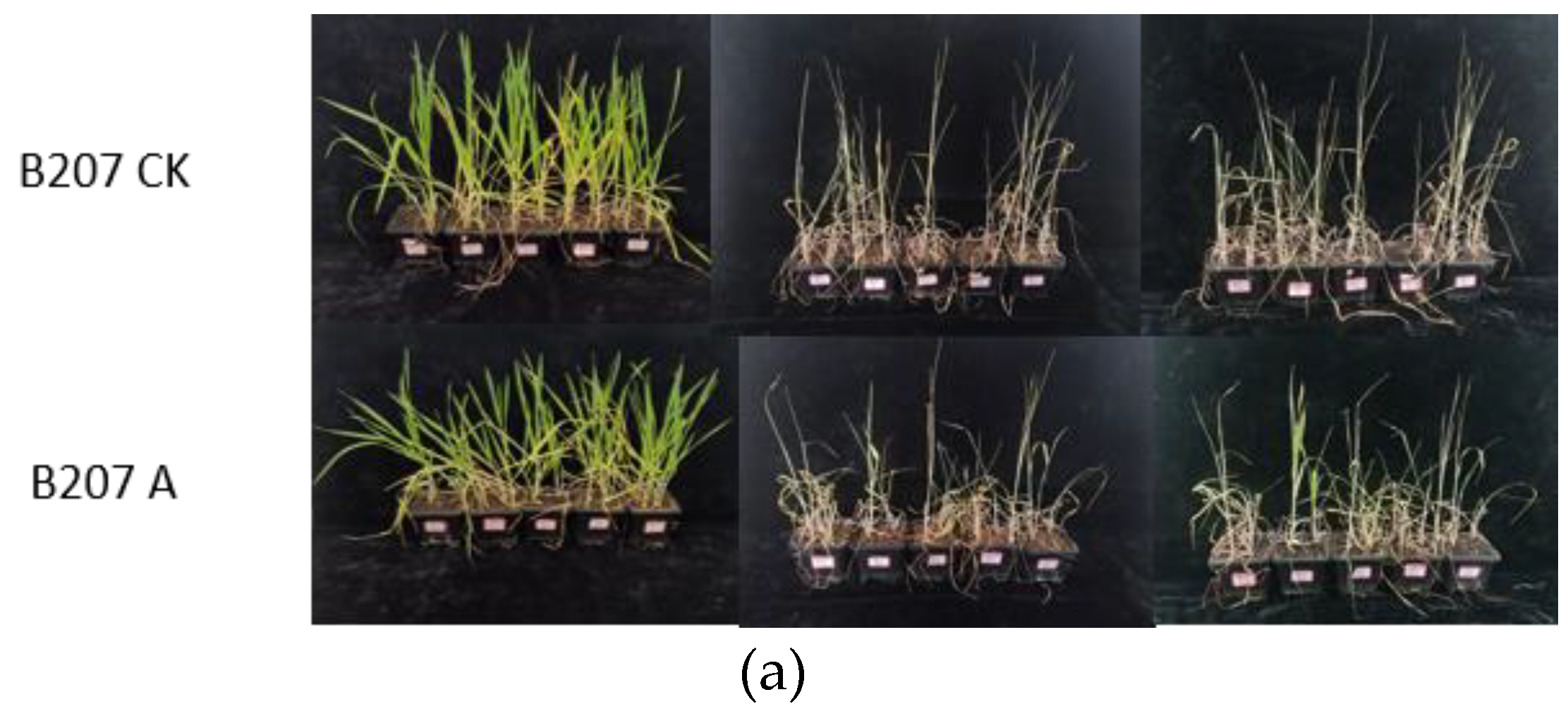

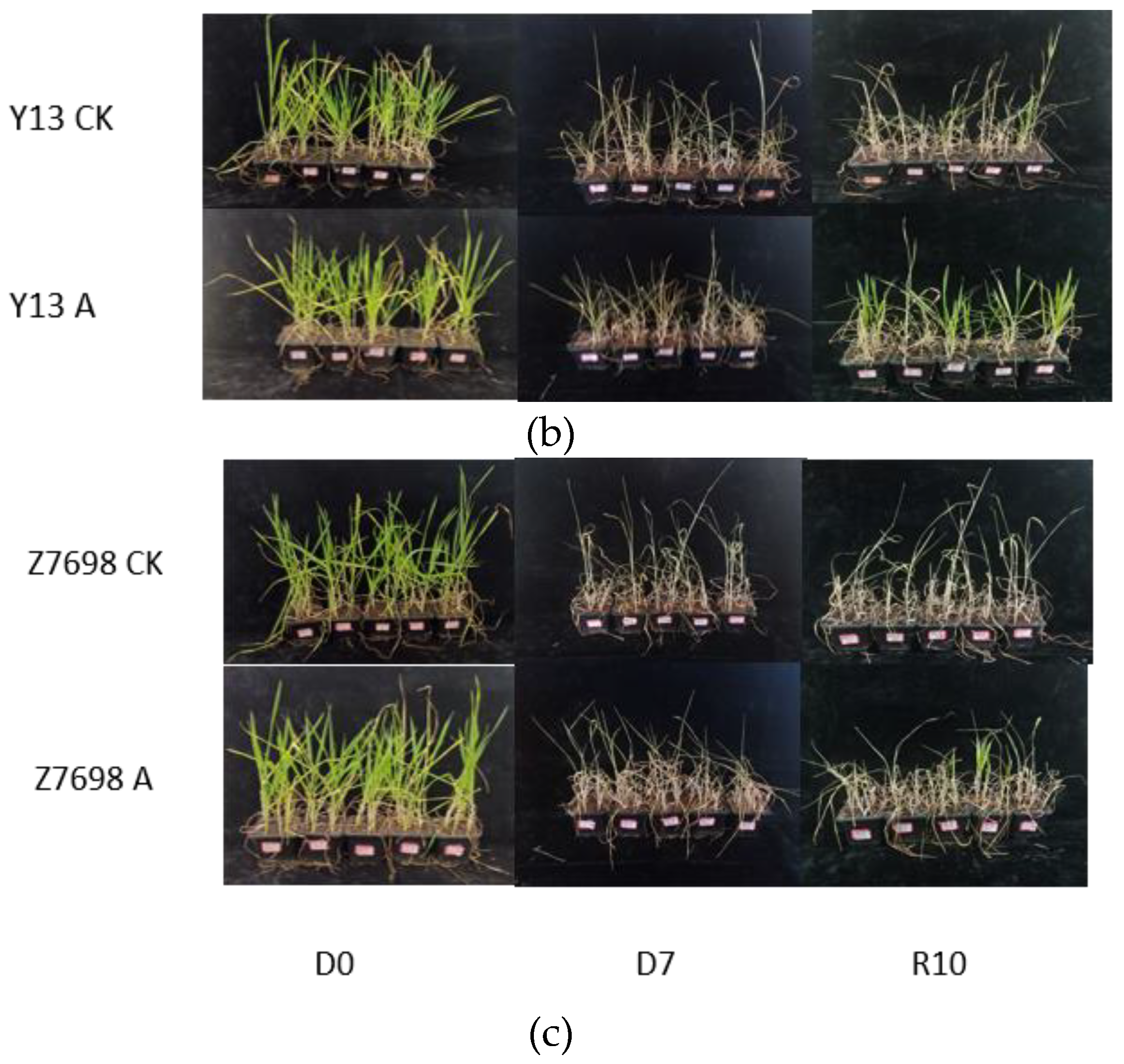

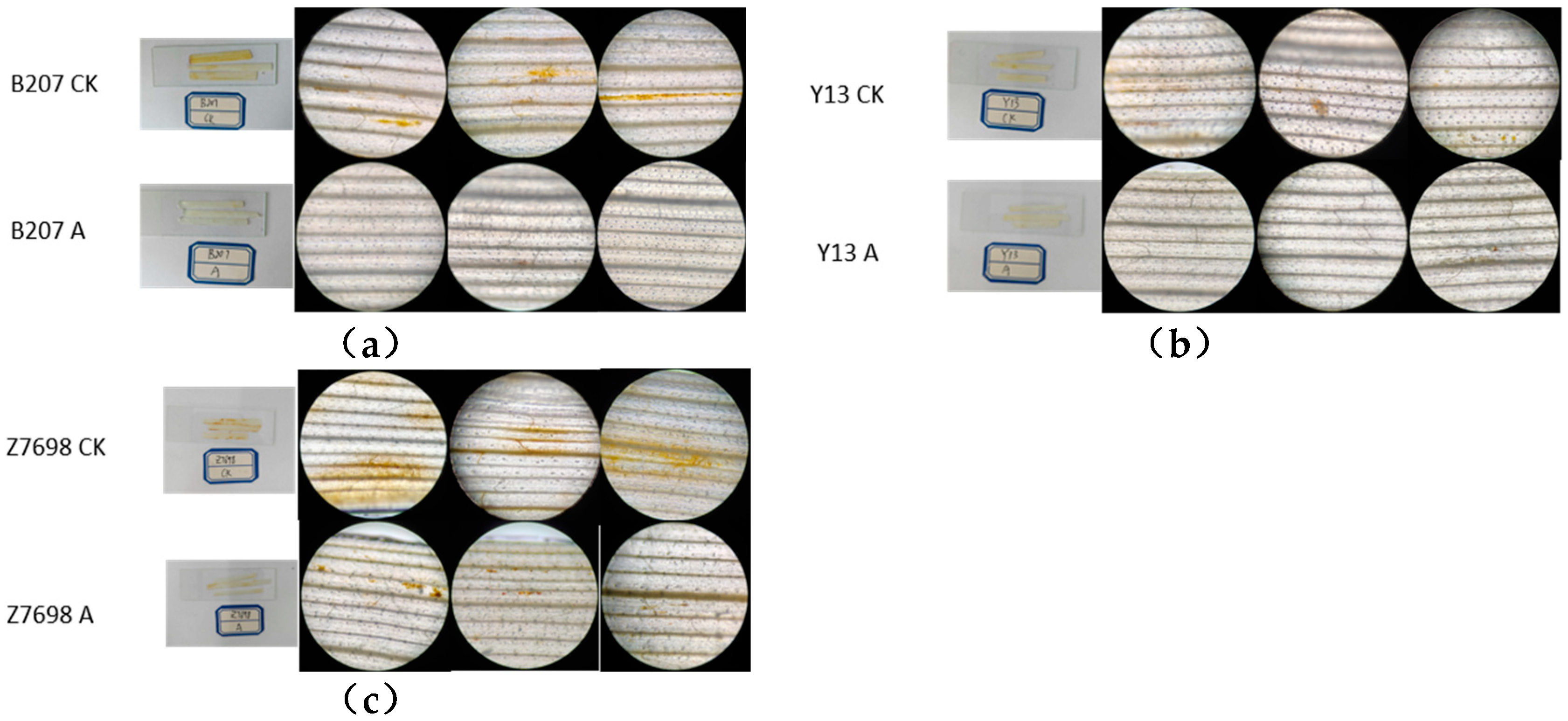

2.4.1. Phenotype of Drought and High-Temperature Treatment

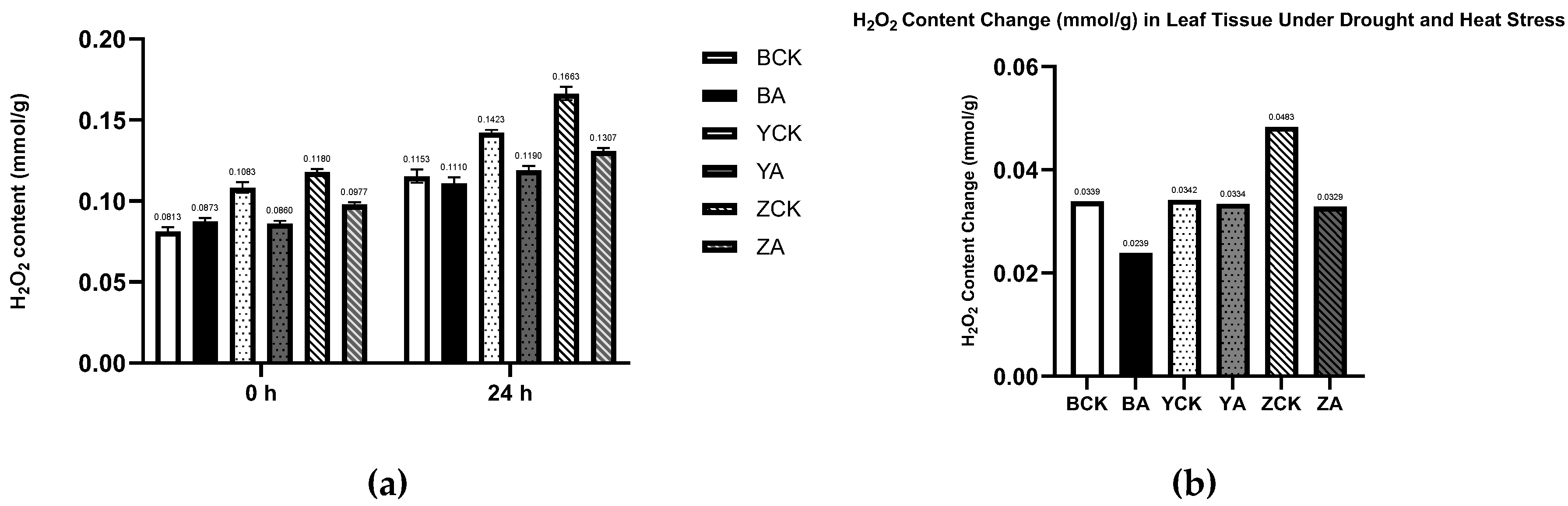

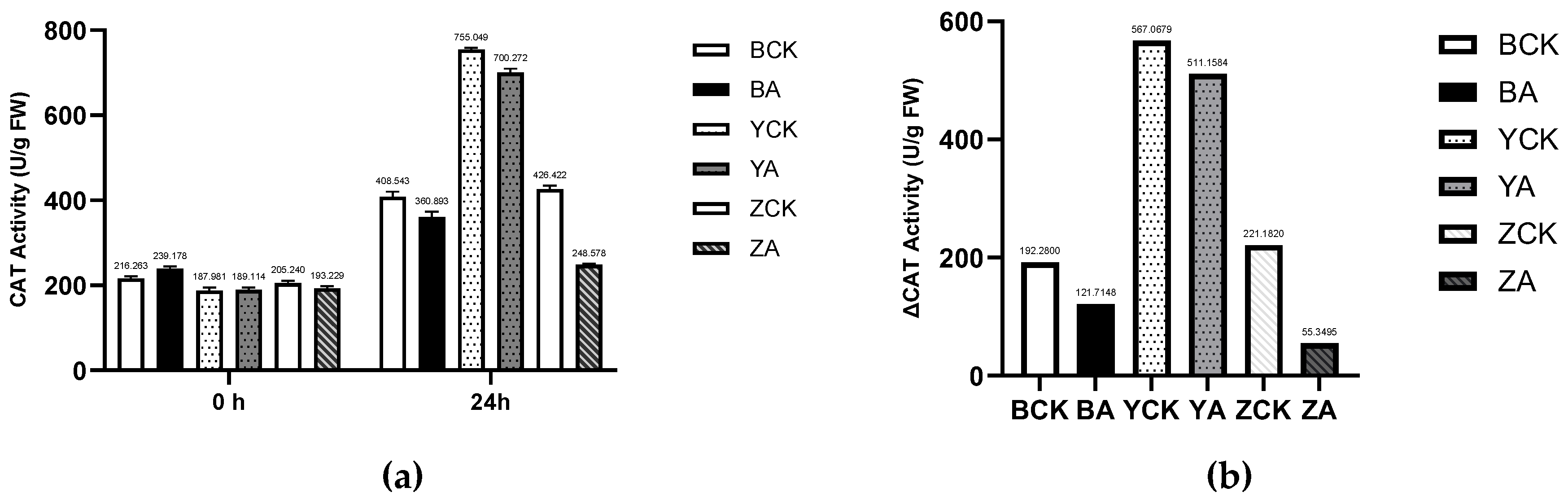

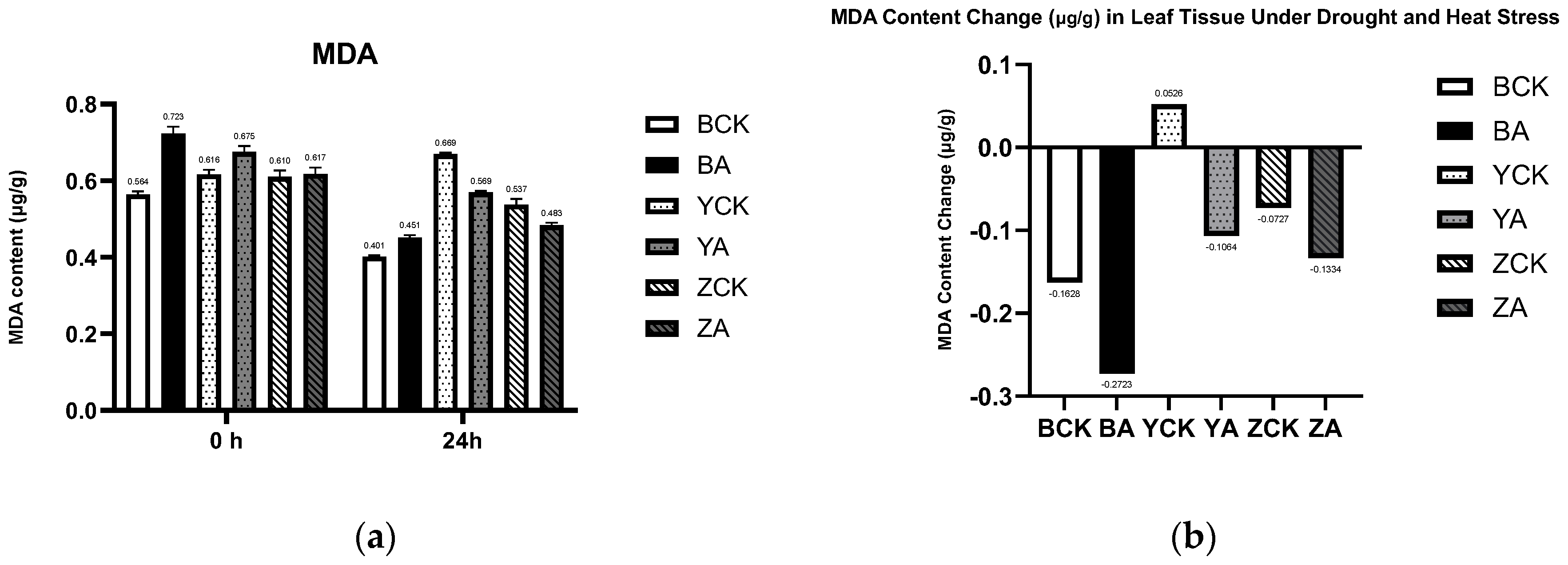

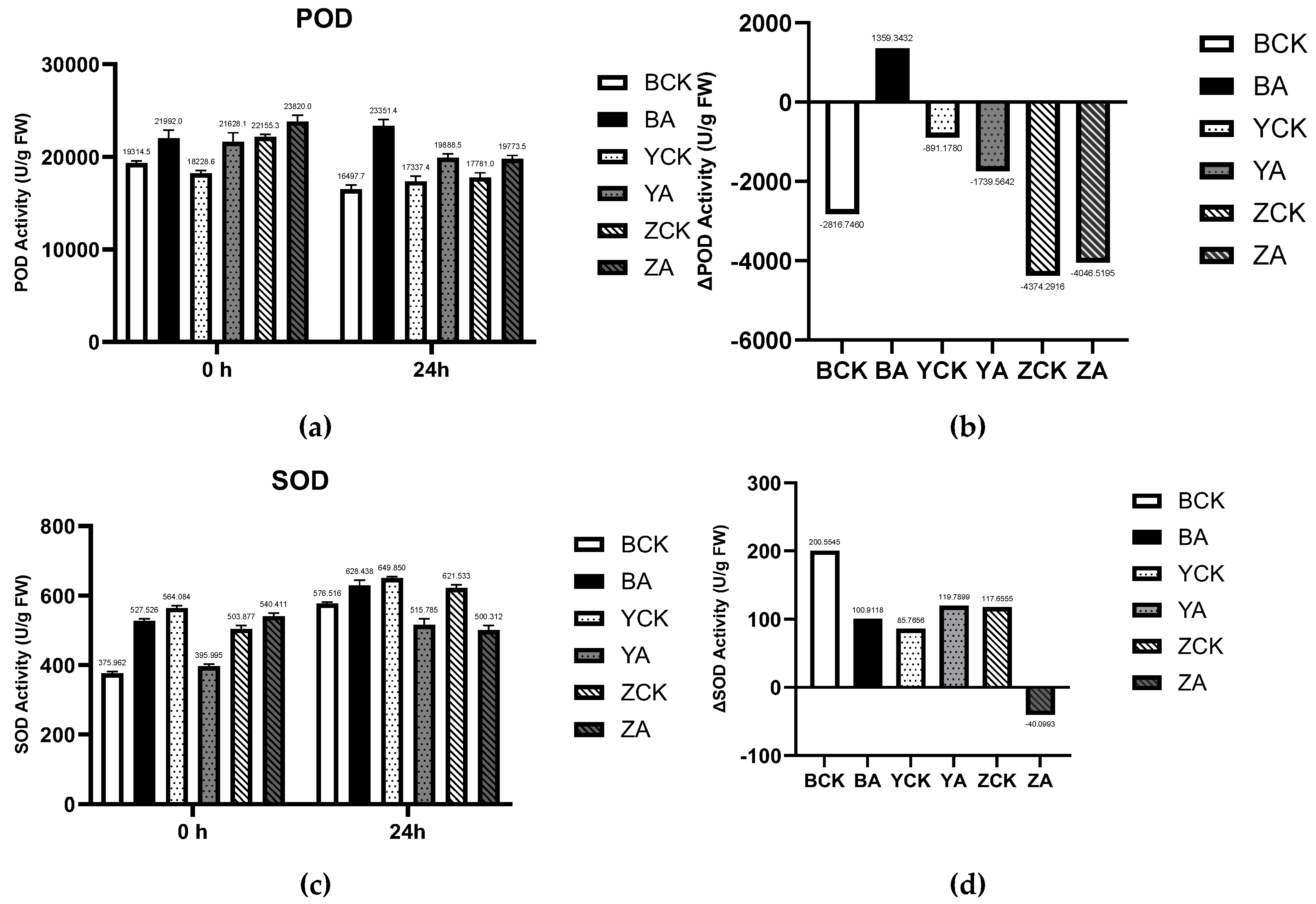

2.4.2. Detection of Physiological Indexes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation and Cloning of TaMIOXA

4.2. Bioinformatics Analysis of TaMIOXA

4.3. Expression Analysis of the TaMIOXA Gene

4.4. Preparation of Vector and Transformation of Wheat Plants

4.5. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.6. Analysis of Physiological Indicators After Stress Overexpression of TaMIOXA in Wheat

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TaMIOXA | myo-inositol oxygenase gene in Triticum aestivum A-genome (Triticum urartu) |

| TaMIOXB | myo-inositol oxygenase gene in Triticum aestivum B-genome (Aegilops speltoides) |

| TaMIOXD | myo-inositol oxygenase gene in Triticum aestivum D-genome (Aegilops tauschii) |

| B207A | TaMIOXA overexpressing lines of wheat cultivar Bainong 207 |

| Y13207A | TaMIOXA overexpressing lines of wheat cultivar Yangmai 13 |

| Z7698A | TaMIOXA overexpressing lines of wheat cultivar Zhengmai 7698 |

| B207CK | control line of wheat cultivar Baonong 207 |

| Y13207CK | control line of wheat cultivar Yangmai 13 |

| Z7698CK | control line of wheat cultivar Zhengmai 7698 |

| CAT | catalase |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| POD | peroxidase |

| GlcA | glucuronic acid |

| ASA | ascorbic acid |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

References

- Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wei, S.; Qin, F.; Zhao, H.; Suo, B., Identification of Circular RNAs and Their Targets in Leaves of Triticum aestivum L. under Dehydration Stress. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Reynolds, M. P.; Jing, R.; Wang, C.; Mao, X., Wheat TaSnRK2.10 phosphorylates TaERD15 and TaENO1 and confers drought tolerance when overexpressed in rice. Plant Physiol 2023, 191, (2), 1344-1364. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, M.; Zhu, X.; Nai, F.; Yang, R.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ma, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, X., TaGSr contributes to low-nitrogen tolerance by optimizing nitrogen uptake and assimilation in Arabidopsis. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2024, 219, 105657. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M. P.; Lewis, J. M.; Ammar, K.; Basnet, B. R.; Crespo-Herrera, L.; Crossa, J.; Dhugga, K. S.; Dreisigacker, S.; Juliana, P.; Karwat, H.; Kishii, M.; Krause, M. R.; Langridge, P.; Lashkari, A.; Mondal, S.; Payne, T.; Pequeno, D.; Pinto, F.; Sansaloni, C.; Schulthess, U.; Singh, R. P.; Sonder, K.; Sukumaran, S.; Xiong, W.; Braun, H. J., Harnessing translational research in wheat for climate resilience. J Exp Bot 2021, 72, (14), 5134-5157. [CrossRef]

- Rathor, P.; Rouleau, V.; Gorim, L. Y.; Chen, G.; Thilakarathna, M. S., Humalite enhances the growth, grain yield, and protein content of wheat by improving soil nitrogen availability and nutrient uptake. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2024, 187, (2), 247-259. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, P.; Su, X.; Zhao, H., Effects of 2,4-epibrassinolide on photosynthesis and Rubisco activase gene expression in Triticum aestivum L. seedlings under a combination of drought and heat stress. Plant Growth Regulation 2017, 81, (3), 377-384. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, P.; Gao, M.; Wang, D.; Zhao, H., High temperature effects on D1 protein turnover in three wheat varieties with different heat susceptibility. Plant Growth Regulation 2017, 81, (1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, J. A.; Capó-Bauçà, S.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Galmés, J., Rubisco and Rubisco Activase Play an Important Role in the Biochemical Limitations of Photosynthesis in Rice, Wheat, and Maize under High Temperature and Water Deficit. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 490. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Wen, H.; Zhang, J.; Peng, T.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Q., High temperature and drought stress cause abscisic acid and reactive oxygen species accumulation and suppress seed germination growth in rice. Protoplasma 2019, 256, (5), 1217-1227. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Ma, D.; Huang, X.; Hou, J.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, H.; Guo, T., Exogenous hydrogen sulfide alleviates salt stress by improving antioxidant defenses and the salt overly sensitive pathway in wheat seedlings. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2019, 41, (7), 123. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xin, Z.; Yang, T.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Lin, T., Metabolomics Response for Drought Stress Tolerance in Chinese Wheat Genotypes (Triticum aestivum). Plants (Basel) 2020, 9, (4). [CrossRef]

- Maseyk, K.; Lin, T.; Cochavi, A.; Schwartz, A.; Yakir, D., Quantification of leaf-scale light energy allocation and photoprotection processes in a Mediterranean pine forest under extensive seasonal drought. Tree Physiol 2019, 39, (10), 1767-1782. [CrossRef]

- Bouremani, N.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Silini, A.; Bouket, A. C.; Luptakova, L.; Alenezi, F. N.; Baranov, O.; Belbahri, L., Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): A Rampart against the Adverse Effects of Drought Stress. In Water, 2023; Vol. 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yan, S.; Zhang, S.; Yan, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H., Glutathione, carbohydrate and other metabolites of Larix olgensis A. Henry reponse to polyethylene glycol-simulated drought stress. PLoS One 2021, 16, (11), e0253780. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Xiao, F.; He, K., Physiological response and drought resistance evaluation of Gleditsia sinensis seedlings under drought-rehydration state. Sci Rep 2023, 13, (1), 19963. [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Shi, J.; Kovalchuk, N.; Luang, S.; Bazanova, N.; Chirkova, L.; Zhang, D.; Shavrukov, Y.; Stepanenko, A.; Tricker, P.; Langridge, P.; Hrmova, M.; Lopato, S.; Borisjuk, N., Overexpression of the TaSHN1 transcription factor in bread wheat leads to leaf surface modifications, improved drought tolerance, and no yield penalty under controlled growth conditions. Plant Cell Environ 2018, 41, (11), 2549-2566. [CrossRef]

- Xue, R. L.; Wang, S. Q.; Xu, H. L.; Zhang, P. J.; Li, H.; Zhao, H. J., Progesterone increases photochemical efficiency of photosystem II in wheat under heat stress by facilitating D1 protein phosphorylation. Photosynthetica 2017, 55, (4), 664-670. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, X., Endoplasmic reticulum stress-responsive microRNAs are involved in the regulation of abiotic stresses in wheat. Plant Cell Rep 2023, 42, (9), 1433-1452. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, J.; Guo, R.; Zhao, M.; Hu, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, H.; Li, Y., Physiological characteristics and metabolomics of transgenic wheat containing the maize C(4) phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) gene under high temperature stress. Protoplasma 2017, 254, (2), 1017-1030. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, H.; Bi, H.; Xu, H., The Wheat MYB Transcription Factor TaMYB(31) Is Involved in Drought Stress Responses in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 1426. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Liu, M.; Miao, J.; Ma, C.; Feng, Y.; Qian, J.; Li, H.; Bi, H.; Liu, W., The SPL transcription factor TaSPL6 negatively regulates drought stress response in wheat. Plant Physiol Biochem 2024, 206, 108264. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Su, X.; Xia, Z., Overexpression of NtDOG1L-T Improves Heat Stress Tolerance by Modulation of Antioxidant Capability and Defense-, Heat-, and ABA-Related Gene Expression in Tobacco. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 568489. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Xia, Z., Overexpression of a maize SUMO conjugating enzyme gene (ZmSCE1e) increases Sumoylation levels and enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Sci 2019, 281, 113-121. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Ren, Z.; Abou-Elwafa, S. F.; Pu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Dou, D.; Su, H.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, E.; Shao, R.; Ku, L., ZmERF21 directly regulates hormone signaling and stress-responsive gene expression to influence drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Plant Cell Environ 2022, 45, (2), 312-328. [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, N.; Wang, Y.; Fan, J.; Li, Y.; Ding, J., Down-Regulation of Cytokinin Receptor Gene SlHK2 Improves Plant Tolerance to Drought, Heat, and Combined Stresses in Tomato. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11, (2). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Miao, J.; He, J.; Tian, X.; Gao, K.; Ma, C.; Tian, X.; Men, W.; Li, H.; Bi, H.; Liu, W., Wheat heat shock factor TaHsfA2d contributes to plant responses to phosphate deficiency. Plant Physiol Biochem 2022, 185, 178-187. [CrossRef]

- Alok, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar, P.; Bhati, K. K., Potential of engineering the myo-inositol oxidation pathway to increase stress resilience in plants. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, (8), 8025-8035. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov Kavkova, E.; Blöchl, C.; Tenhaken, R., The Myo-inositol pathway does not contribute to ascorbic acid synthesis. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 2019, 21 Suppl 1, (Suppl Suppl 1), 95-102. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, L.; Liu, M.; Li, P.; Lu, Q.; Peng, R., Genome-wide identification of the MIOX gene family and their expression profile in cotton development and response to abiotic stress. PLoS One 2021, 16, (7), e0254111. [CrossRef]

- Nepal, N.; Yactayo-Chang, J. P.; Medina-Jiménez, K.; Acosta-Gamboa, L. M.; González-Romero, M. E.; Arteaga-Vázquez, M. A.; Lorence, A., Mechanisms underlying the enhanced biomass and abiotic stress tolerance phenotype of an Arabidopsis MIOX over-expresser. Plant Direct 2019, 3, (9), e00165. [CrossRef]

- Flood and Drought Disaster Prevention and Control Division, D. o. W. R. o. H. P.; Li, L.; Junfeng, L.; Zhipeng, G.; Hao, S.; Di, W.; Rongrong, G., Henan Province: Precise measures to fully ensure the water supply demand for drought resistance, planting and seedling protection. China Flood & Drought Management 2024, 34, (8), 81-82.

- Carril, P.; da Silva, A. B.; Tenreiro, R.; Cruz, C., An Optimized in situ Quantification Method of Leaf H(2)O(2) Unveils Interaction Dynamics of Pathogenic and Beneficial Bacteria in Wheat. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 889. [CrossRef]

- Moskala, R.; Reddy, C. C.; Minard, R. D.; Hamilton, G. A., An oxygen-18 tracer investigation of the mechanism of myo-inositol oxygenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1981, 99, (1), 107-13. [CrossRef]

- Lorence, A.; Chevone, B. I.; Mendes, P.; Nessler, C. L., myo-inositol oxygenase offers a possible entry point into plant ascorbate biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 2004, 134, (3), 1200-5. [CrossRef]

- Munir, S.; Mumtaz, M. A.; Ahiakpa, J. K.; Liu, G.; Chen, W.; Zhou, G.; Zheng, W.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Y., Genome-wide analysis of Myo-inositol oxygenase gene family in tomato reveals their involvement in ascorbic acid accumulation. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, (1), 284. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z. Main Pathway and Key Gene Contribution to the Increasing AsA Concentration in Cucumber Leaves under Nitrogen Deficiency. Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, 2016.

- Tatineni, S.; Alexander, J.; Qu, F., Differential Synergistic Interactions Among Four Different Wheat-Infecting Viruses. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 800318. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gan, J.; Mi, X., On four species of the genus Argiope Audouin, 1826 (Araneae, Araneidae) from China. Zookeys 2021, 1019, 15-34. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. L.; Zhang, C.; Hao, J.; Wang, X. L.; Ming, J.; Mi, L.; Na, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y., DPPA2/4 and SUMO E3 ligase PIAS4 opposingly regulate zygotic transcriptional program. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, (6), e3000324. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, M.; Shang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhao, M.; Tang, Q.; Tang, Q.; Luo, J., Immunogenicity and protection of recombinant self-assembling ferritin-hemagglutinin nanoparticle influenza vaccine in mice. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2025, 14, (1), 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E. W.; Bolton, E. E.; Brister, J. R.; Canese, K.; Chan, J.; Comeau, D. C.; Connor, R.; Funk, K.; Kelly, C.; Kim, S.; Madej, T.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Lanczycki, C.; Lathrop, S.; Lu, Z.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Murphy, T.; Phan, L.; Skripchenko, Y.; Tse, T.; Wang, J.; Williams, R.; Trawick, B. W.; Pruitt, K. D.; Sherry, S. T., Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, (D1), D20-d26. [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Yan, L.; Li, H.; Lian, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Ye, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Feng, J., Genome-wide identification of HSF family in peach and functional analysis of PpHSF5 involvement in root and aerial organ development. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10961. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Du, Y.; Li, Z.; Guo, R.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Yin, X.; Su, L., Soldier Caste-Specific Protein 1 Is Involved in Soldier Differentiation in Termite Reticulitermes aculabialis. Insects 2022, 13, (6). [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M. S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M. E.; Valiente, P. A.; Moreno, E., AMDock: a versatile graphical tool for assisting molecular docking with Autodock Vina and Autodock4. Biol Direct 2020, 15, (1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, C.; Li, S.; Kong, L.; Wu, W.; Kong, W.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, J. K.; Zhang, H., The inhibition of protein translation mediated by AtGCN1 is essential for cold tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ 2017, 40, (1), 56-68. [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, M.; Matus, J. T.; Francia, P.; Rusconi, F.; Cañón, P.; Medina, C.; Conti, L.; Cominelli, E.; Tonelli, C.; Arce-Johnson, P., The grapevine guard cell-related VvMYB60 transcription factor is involved in the regulation of stomatal activity and is differentially expressed in response to ABA and osmotic stress. BMC Plant Biol 2011, 11, 142. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, K.; Bai, C.; Yin, D.; Li, G.; Qi, K.; Wang, G.; Li, Y., Development of a SYBR Green I real-time PCR for the detection of the orf virus. AMB Express 2017, 7, (1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, X.; Yang, L.; Raziq, A.; Hao, S.; Zeng, W.; Huang, J.; Cao, Y.; Duan, Q., Nontransformation methods for studying signaling pathways and genes involved in Brassica rapa pollen-stigma interactions. Plant Physiol 2024, 196, (3), 1802-1812. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Rong, W.; Wang, K.; Guo, W.; Zhou, M.; Wu, J.; Ye, X.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z., Overexpression of TaSTT3b-2B improves resistance to sharp eyespot and increases grain weight in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J 2022, 20, (4), 777-793. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, J.; Duan, W.; Ma, X.; Qu, L.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J., NtRAV4 negatively regulates drought tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum by enhancing antioxidant capacity and defence system. Plant Cell Rep 2022, 41, (8), 1775-1788. [CrossRef]

- Davoudpour, Y.; Schmidt, M.; Calabrese, F.; Richnow, H. H.; Musat, N., High resolution microscopy to evaluate the efficiency of surface sterilization of Zea Mays seeds. PLoS One 2020, 15, (11), e0242247. [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Hou, H.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Guo, S.; Huang, S.; Zhang, C., Effect of dietary Glycyrrhiza polysaccharides on growth performance, hepatic antioxidant capacity and anti-inflammatory capacity of broiler chickens. Res Vet Sci 2024, 167, 105114. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, N.; Wei, S.; Wang, J.; Qin, F.; Suo, B., The iTRAQ-based chloroplast proteomic analysis of Triticum aestivum L. leaves subjected to drought stress and 5-aminolevulinic acid alleviation reveals several proteins involved in the protection of photosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20, (1), 96. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Fan, X.; Shao, R.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, Q.; Guo, L., Physiological and iTRAQ-based proteomic analyses reveal that melatonin alleviates oxidative damage in maize leaves exposed to drought stress. Plant Physiol Biochem 2019, 142, 263-274. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, F. K.; Rivero, R. M.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R., Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J 2017, 90, (5), 856-867. [CrossRef]

- Eixelsberger, T.; Horvat, D.; Gutmann, A.; Weber, H.; Nidetzky, B., Isotope Probing of the UDP-Apiose/UDP-Xylose Synthase Reaction: Evidence of a Mechanism via a Coupled Oxidation and Aldol Cleavage. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2017, 56, (9), 2503-2507. [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Kumar, S.; Sui, X.; Niu, J.; Yang, J.; Zheng, M.; Tang, Y.; Li, H., Exogenous acetylsalicylic acid mitigates cold stress in common bean seedlings by enhancing antioxidant defense and photosynthetic efficiency. Front Plant Sci 2025, 16, 1589706. [CrossRef]

| Survival Count (Plants) | Initial Count (Plants) | Survival Rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | B207 CK | 2 | 30 | 6.67 |

| Y13 CK | 4 | 30 | 13.33 | |

| Z7698 CK | 0 | 30 | 0 | |

| OE-TaMIOX-A | B207 A | 5 | 30 | 16.67 |

| Y13 A | 16 | 30 | 53.33 | |

| Z7698 A | 12 | 30 | 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).