Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Lower Urinary Tract Inflammation

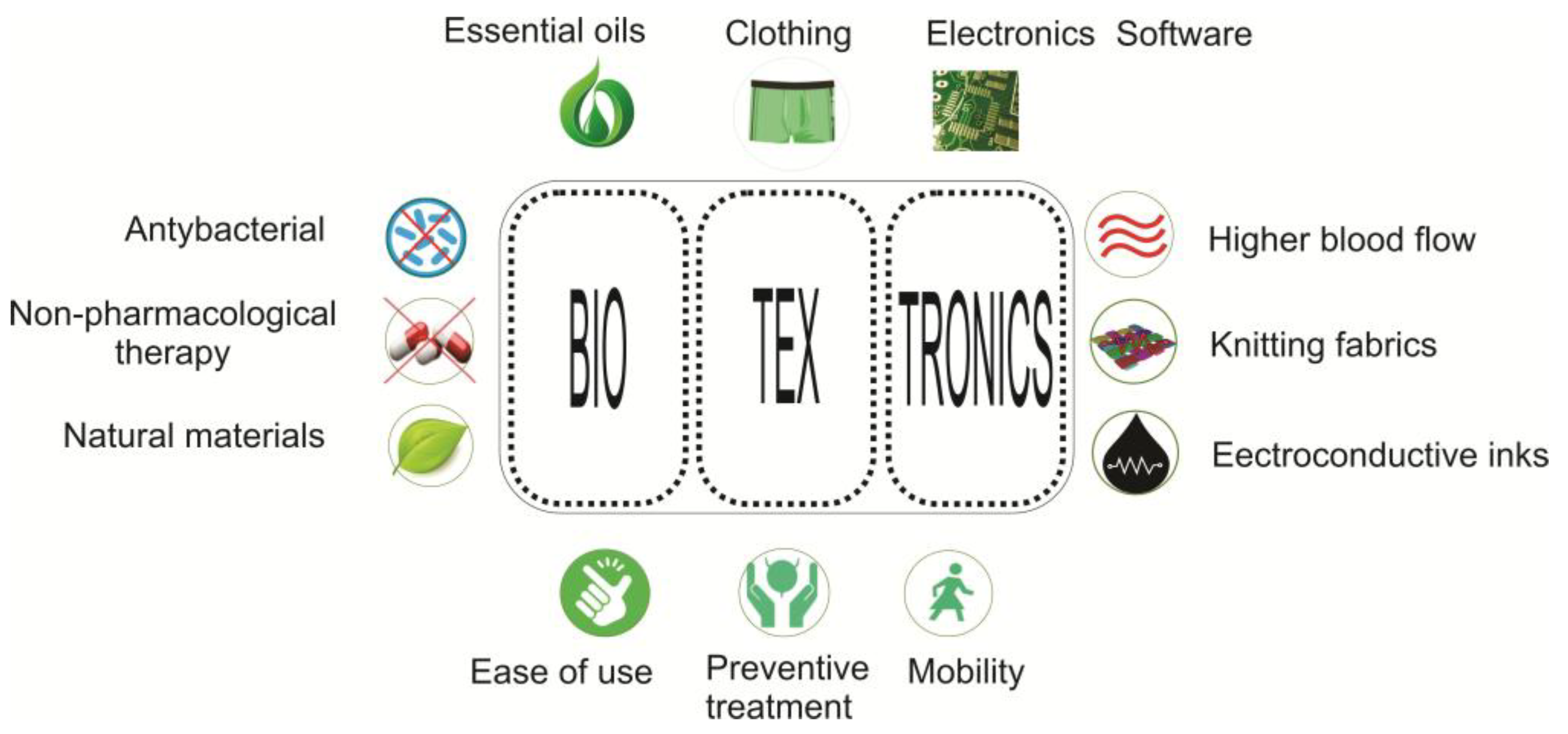

2. Textronics and Biotextronics in Healthcare

- high flexibility;

- lightness;

- resistance to mechanical and operational exposure;

- resistance to moisture (sweat, washing);

- resistance to weather conditions (variable temperature, rain, humidity).

3. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

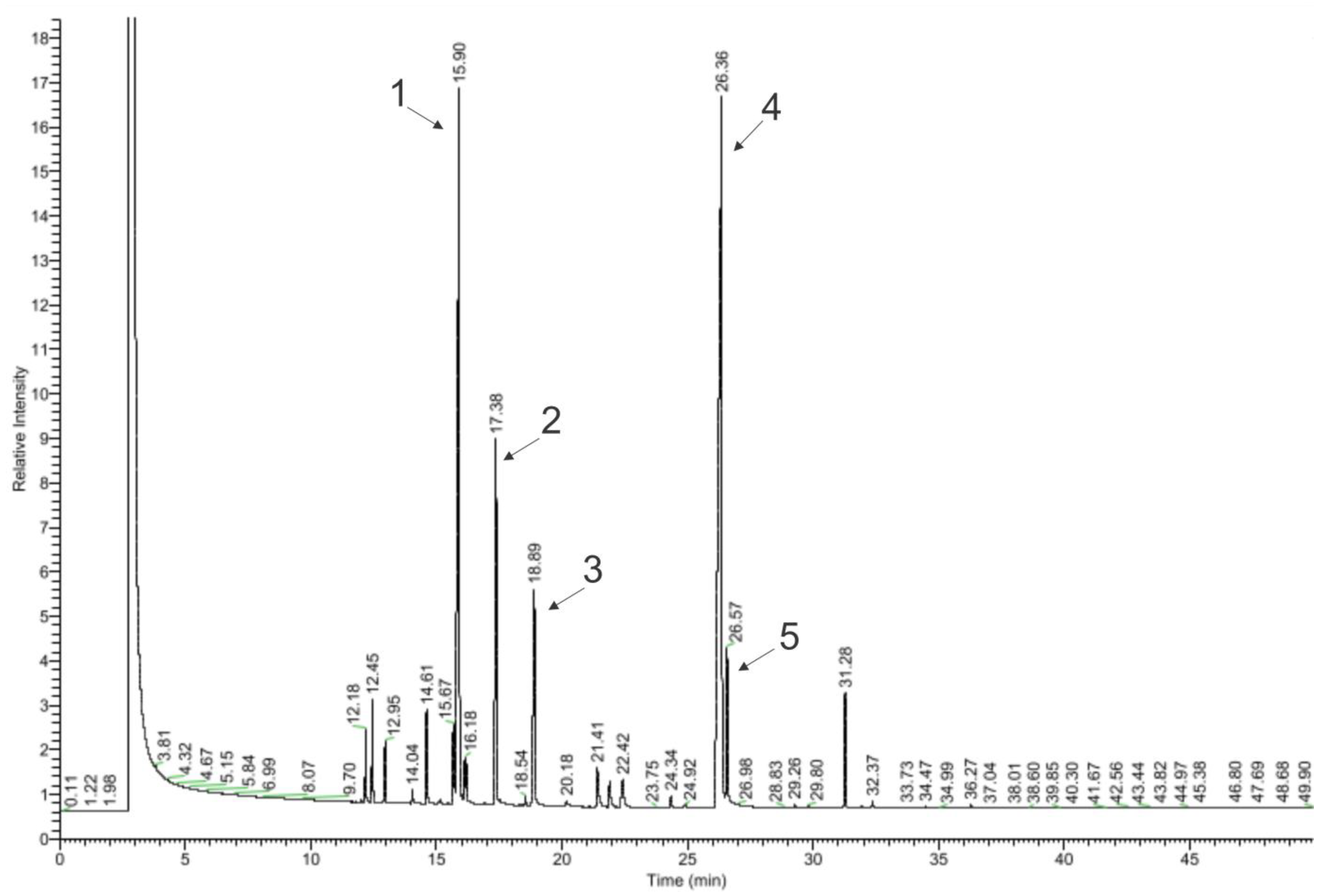

4.2.1. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

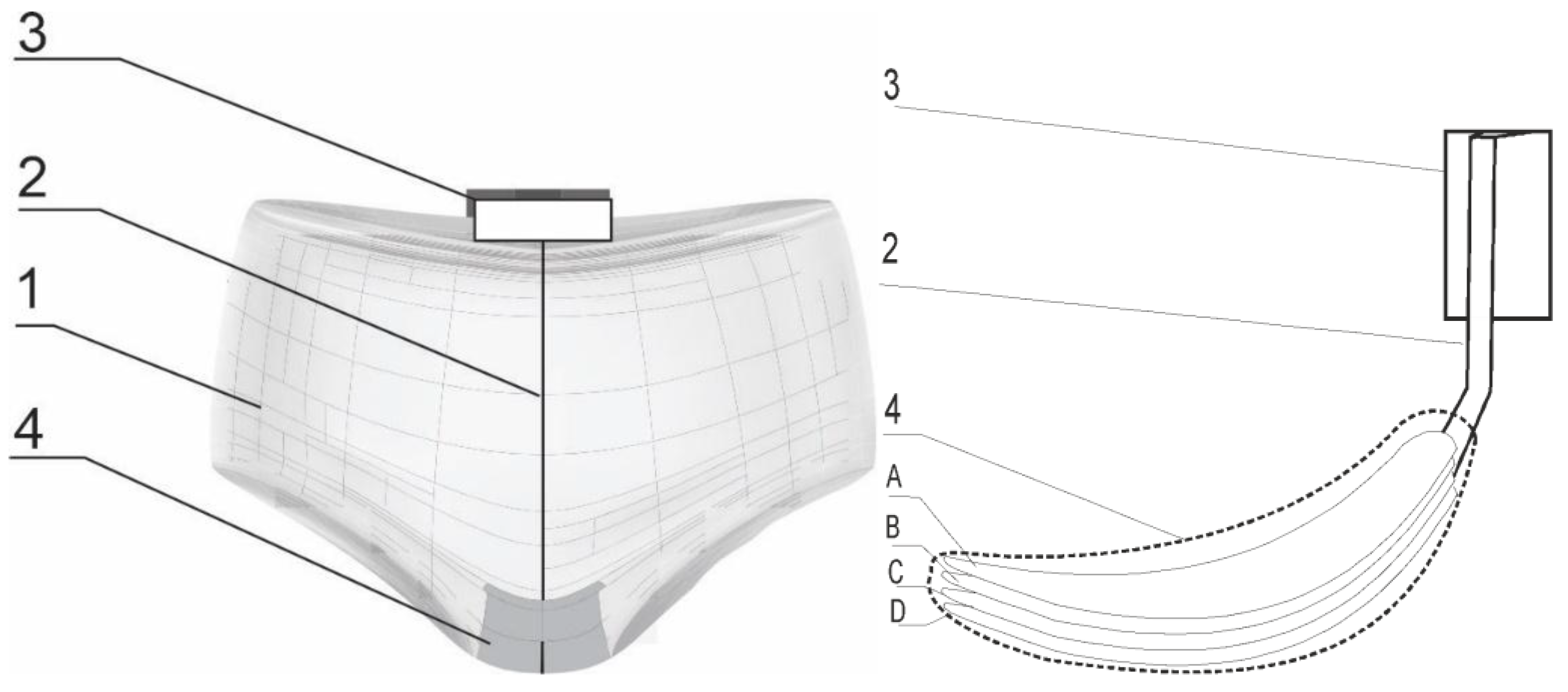

4.2.2. Preparing the Model Inserts

4.2.3. Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME)

- temperature: 40°C;

- conditioning time: taq = 5 and 10 min;

- extraction time: tex = 20 min;

- no mixing;

- fiber: ternary DVB/CAR/PDMS (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

5. Results

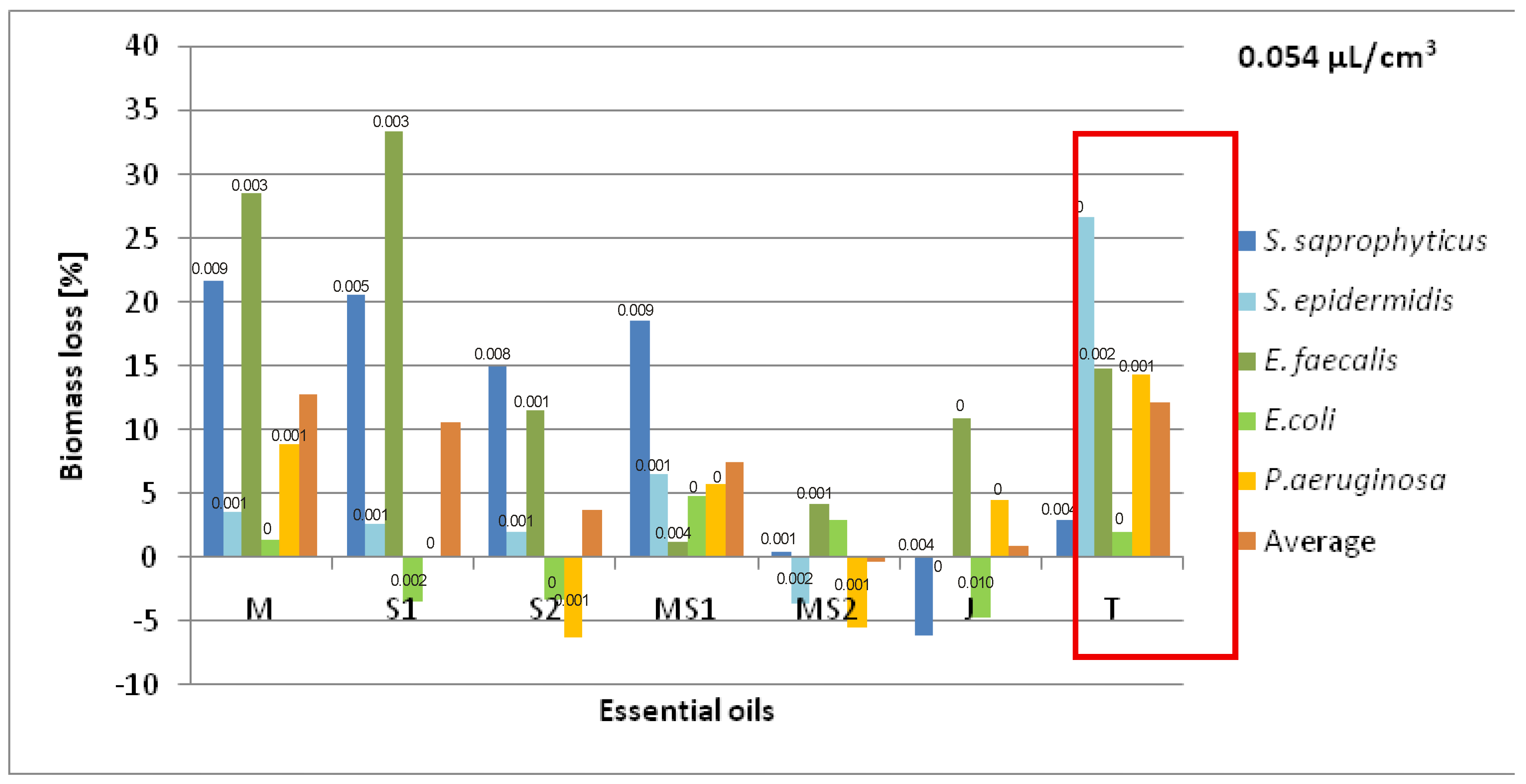

5.1. Chemical Part

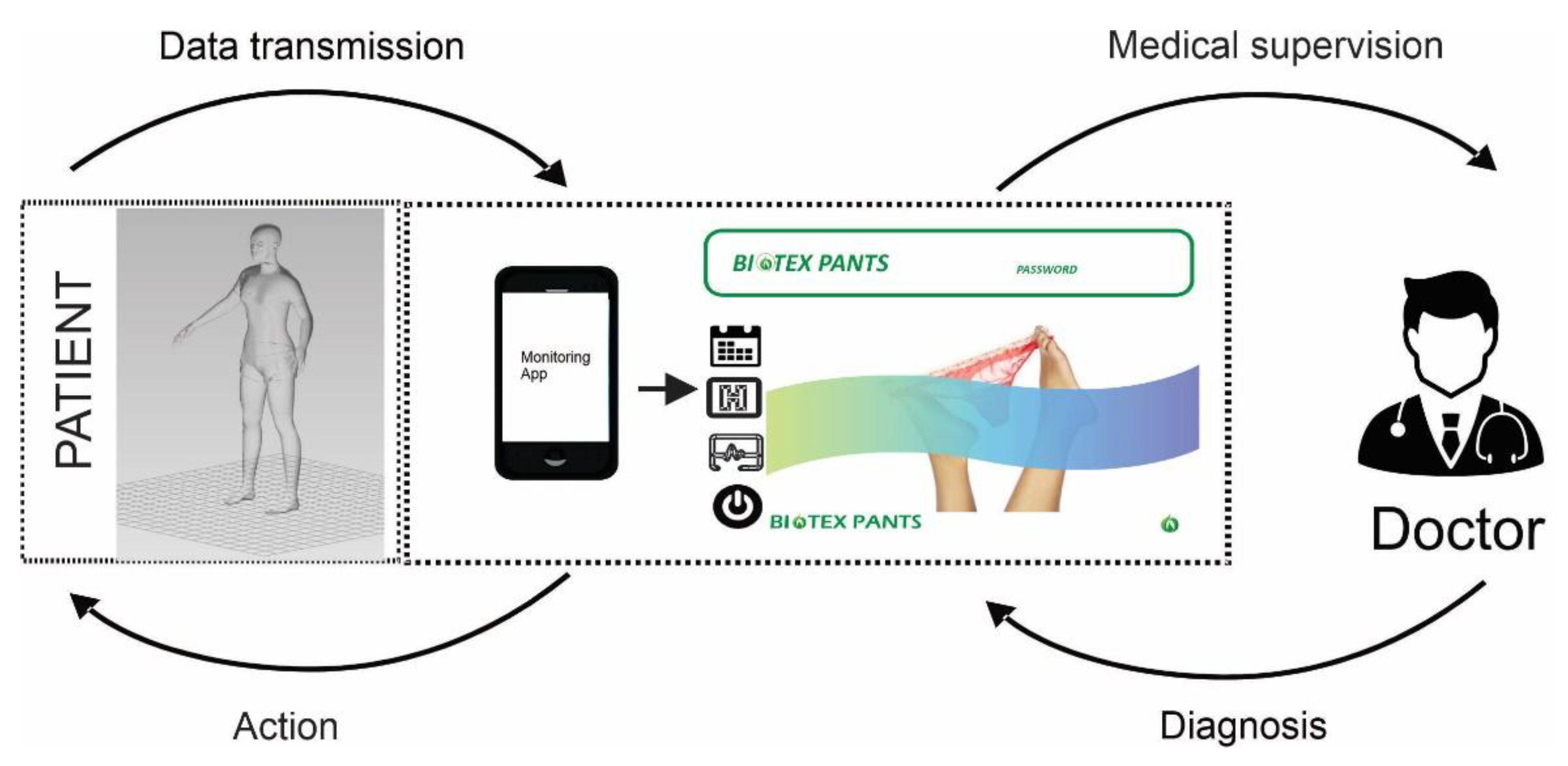

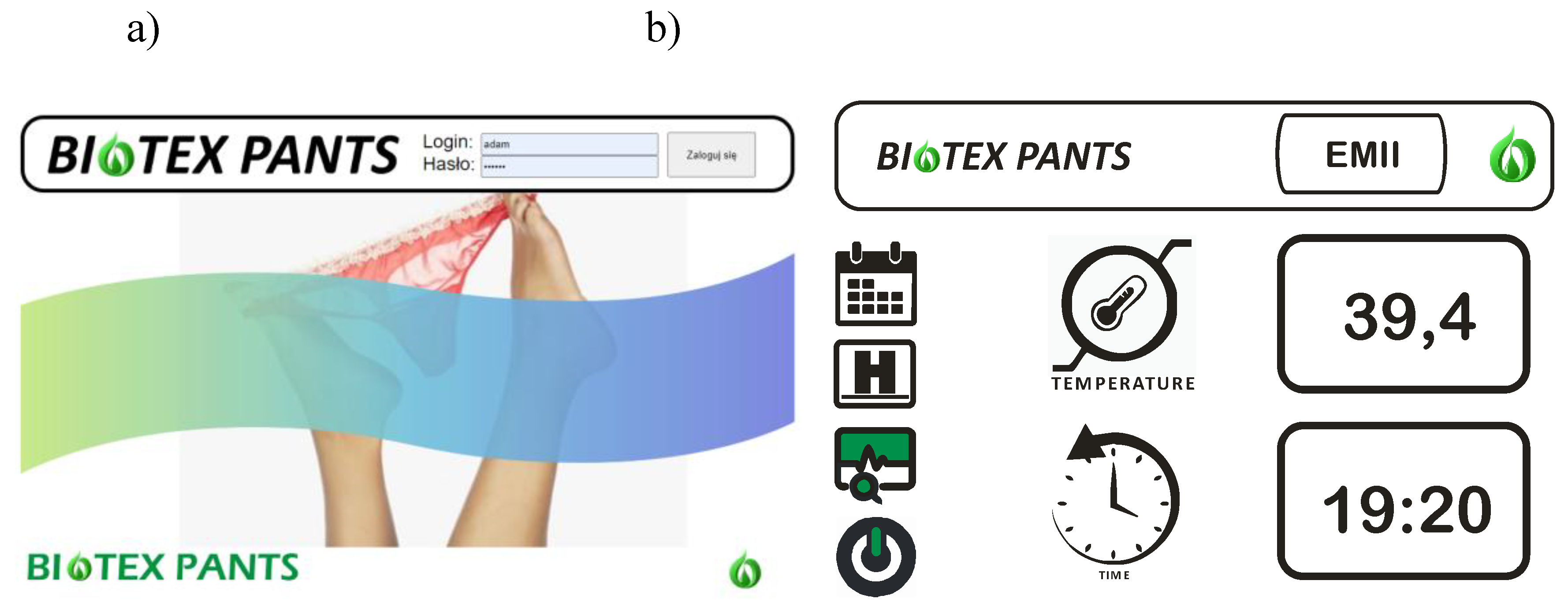

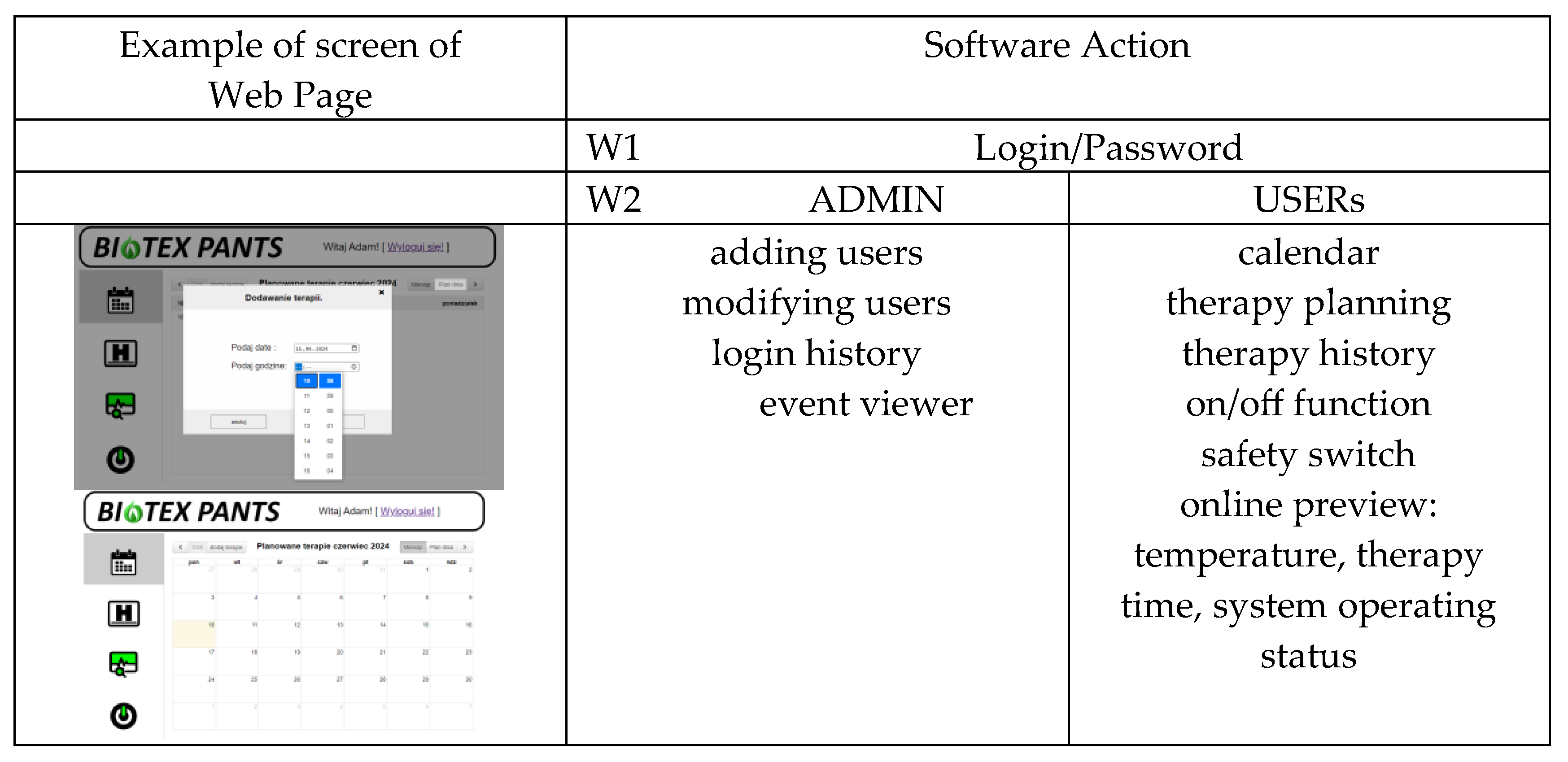

5.2. Software Part

6. Discussion and Conclusions

References

- B. Abelson et al., “Sex differences in lower urinary tract biology and physiology,” Biol Sex Differ, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Henning and K. F. Jureidini, “Urinary tract infection.,” Aust Fam Physician, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1–2, 1989.

- K. Dickson, J. Zhou, and C. Lehmann, “Lower Urinary Tract Inflammation and Infection: Key Microbiological and Immunological Aspects.,” J Clin Med, vol. 13, no. 2, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Wasik-Olejnik, “Recurrent urinary tract infections \– prophylaxis and treatment,” Przewodnik Lekarza/Guide for GPs, pp. 18–23, 2009, [Online]. Available: https://www.termedia.pl/Recurrent-urinary-tract-infections-8211-prophylaxis-and-treatment,8,13276,1,1.html.

- S. Das, “Natural therapeutics for urinary tract infections—a review,” Futur J Pharm Sci, vol. 6, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Pulipati, P. Srinivasa Babu, M. Lakshmi Narasu, C. Sowjanya Pulipati, and N. Anusha, “An overview on urinary tract infections and effective natural remedies,” ~ 50 ~ Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 50–56, 2017, [Online]. Available: https://www.plantsjournal.com/archives/2017/vol5issue6/PartA/5-6-7-566.pdf.

- R. H. Latham, K. Running, and W. E. Stamm, “Urinary tract infections in young adult women caused by Staphylococcus saprophyticus.,” JAMA, vol. 250, no. 22, pp. 3063–3066, Dec. 1983.

- M. Holecki et al., Rekomendacje diagnostyki, terapii i profilaktyki zakażeń układu moczowego u dorosłych. 2015.

- M. Loose, E. Pilger, and F. Wagenlehner, “Anti-bacterial effects of essential oils against uropathogenic bacteria,” Antibiotics, vol. 9, no. 6, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Miller and J. N. Krieger, “Urinary tract infections cranberry juice, underwear, and probiotics in the 21st century,” Urologic Clinics of North America, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 695–699. [CrossRef]

- G. Song, “Improving Comfort in Clothing,” Improving Comfort in Clothing, pp. 1–459, 2011. [CrossRef]

- B. Filipowska, E. Rybicki, A. Walawska, and E. Matyjas-Zgondek, “New method for the antibacterial and antifungal modification of silver finished textiles,” Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe, vol. 87, no. 4, pp. 124–128, 2011.

- M. S. Abu-Darwish, E. A. D. M. Al-Ramamneh, V. S. Kyslychenko, and U. V. Karpiuk, “The antimicrobial activity of essential oils and extracts of some medicinal plants grown in Ash-shoubak region - South of Jordan,” Pak J Pharm Sci, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 239–246, 2012.

- M. Guennes, J. Cunha, and I. Cabral, “Smart Textile Design: A Systematic Review of Materials and Technologies for Textile Interaction and User Experience Evaluation Methods,” Technologies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 6, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Frydrysiak and L. Tesiorowski, “Wearable textronic system for protecting elderly people,” in 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), 2016, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- M. Frydrysiak and Ł. Tęsiorowski, “Wearable Care System for Elderly People,” International Journal of Pharma Medicine and Biological Sciences, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 171–177, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Łada-Tondyra and A. Jakubas, “Modern applications of textronic systems,” Przeglad Elektrotechniczny, vol. 94, no. 12, pp. 198–201, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Frydrysiak, A. Kunicka-Styczyńska, K. Śmigielski, and M. Frydrysiak, “The impact of selected essential oils applied to non-woven viscose on bacteria that cause lower urinary tract infections—preliminary studies,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Łada-Tondyra, A. Jakubas, B. Jabłońska, and E. Stańczyk-Mazanek, “The research and analysis of the bactericidal properties of the spacer knitted fabric with the UV-C system,” Opto-Electronics Review, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 192–200, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Frydrysiak, K. Śmigielski, J. Zabielska, A. Kunicka-Styczyńska, and M. Frydrysiak, “Antibacterial activity of essential oils potentially used for natural fiber pantiliner textronic system development,” Procedia Eng, vol. 200, pp. 416–421, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Russo et al., “Chemical composition and anticancer activity of essential oils of Mediterranean sage (Salvia officinalis L.) grown in different environmental conditions,” Food and Chemical Toxicology, vol. 55, pp. 42–47, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Das, B. Horváth, S. Šafranko, S. Jokić, A. Széchenyi, and T. Koszegi, “Antimicrobial activity of chamomile essential oil: Effect of different formulations,” Molecules, vol. 24, no. 23, pp. 1–17, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Frydrysiak, K. Śmigielski, A. Kunicka-Styczyńska, and M. Frydrysiak, “Investigation of Releasing Chamomile Essential Oil from Inserts with Cellulose Agar and Microcrystalline Cellulose Agar Films Used in Biotextronics Systems for Lower Urinary Tract Inflammation Treatment,” Materials, vol. 17, no. 16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Kędzia, B. Dera-Tomaszewska, M. Ziółkowska-Klinkosz, A. W. Kędzia, B. Kochańska, and A. Gębska, “Aktywność olejku tymiankowego (Oleum Thymi) wobec bakterii tlenowych,” Postępy Fitoterapii, vol. 2, pp. 67–71, 2012.

- Kędzia, M. Ziółkowska-Klinkosz, Ł. Lassmann, A. Włodarkiewicz, A. Kusiak, and B. Kochańska, “Wrażliwość na olejek tymiankowy (Oleum Thymi) bakterii mikroaerofilnych wyizolowanych z zakażeń jamy ustnej,” Postępy Fitoterapii, vol. 3, pp. 159–162, 2013.

- Lis, A. Lis, and P. Łódzka., Najcenniejsze olejki eteryczne. in Monografie / Politechnika Łódzka. Łódź : Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej,. [Online]. Available: http://www.nukat.edu.pl/nukat/icov/L30/xx003024897.jpg.

- D. Scholes, T. M. Hooton, P. L. Roberts, A. E. Stapleton, K. Gupta, and W. E. Stamm, “Risk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection in young women.,” J Infect Dis, vol. 182, no. 4, pp. 1177–1182, Oct. 2000. [CrossRef]

- P. Satyal, B. L. Murray, R. L. McFeeters, and W. N. Setzer, “Essential oil characterization of thymus vulgaris from various geographical locations,” Foods, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1–12, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Wińska, W. Mączka, J. Łyczko, M. Grabarczyk, A. Czubaszek, and A. Szumny, “Essential oils as antimicrobial agents—myth or real alternative?,” Molecules, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 1–21, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Reyes-Jurado, A. R. Navarro-Cruz, C. E. Ochoa-Velasco, E. Palou, A. López-Malo, and R. Ávila-Sosa, “Essential oils in vapor phase as alternative antimicrobials: A review,” Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, vol. 60, no. 10, pp. 1641–1650, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Reyes-Jurado, A. R. Navarro-Cruz, C. E. Ochoa-Velasco, E. Palou, A. López-Malo, and R. Ávila-Sosa, “Essential oils in vapor phase as alternative antimicrobials: A review,” Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, vol. 60, no. 10, pp. 1641–1650, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Compound | Producer | Target of using |

|---|---|---|

| Non-woven viscose | Lentex S.A. (Poland) | Outer insert layer for EO immobilization |

| Thyme essential oil | Avicenna Oil® (Poland) | Antibacterial activity |

| Cellulose / Microcrystalline cellulose | RETTENMAIER Polska Sp. z o.o. (Poland) | Carrier for EO |

| Agar-agar | Sigma-Aldrich® (USA) | Film for EO immobilization |

| Organoleptic description | Analytical data | Chromatographic profile |

|---|---|---|

| clear liquid, yellow to dark reddish-brown in color, with a strong odor of thymol | density (at 20 °C): 0.915-0.935 g/cm3 refractive index (at 20 °C): 1.490–1.505 optical rotation: -7° to +3° flash point: 58°C |

α-thujene: 0.2-1.5% β-myrcene: 1.0-3.0% α-terpinene: 0.9-2.6% ρ-cymene: 14.0-28.0% γ-terpinene: 4.0-12.0% linalool: 1.5-6.5% terpinen-4-ol: 0.1-2.5% methyl carvacrol ether: 0.05-1.5% thymol: 37.0-55.0% carvacrol: 0.5-5.5% |

| No. | Chemical compounds | Content in EO [%] |

Content according to manufacturer's specifications Avicenna Oil [%] | Content according to European Pharmacopoeia 7 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tricyclene | 0.04 | NA | NA |

| 2 | α-Thujene | 1.28 | 0.2-1.5 | NA |

| 3 | α-Pinene | 1.81 | NA | NA |

| 4 | Camphene | 1.08 | NA | NA |

| 5 | β-Pinene | 0.25 1.81 |

NA | NA |

| 6 | Pseudolimonene | 0.05 | NA | NA |

| 7 | α-Phellandren | 0.09 | NA | NA |

| 8 | Hydroxy-trans-sabinene | 0.05 | NA | NA |

| 9 | α-Terpinene | 1.78 | 0.9-2.6 | NA |

| 10 | p-Cymene | 23.84 | 14.0-28.0 | 15.0-28.0 |

| 11 | β-Cymene | 0.05 | NA | NA |

| 12 | 1.8-Cineole | 0.62 | NA | NA |

| 13 | Limonene | 0.76 | NA | NA |

| 14 | γ-Terpinene | 9.04 | 4.0-12.0 | 5.0-10.0 |

| 15 | cis-Sabinene hydrate | 0.04 | NA | NA |

| 16 | cis-Linalool oxide | 0.03 | NA | NA |

| 17 | α-Terpinolene | 0.20 | NA | NA |

| 18 | Linalool | 5.73 | 1.5-6.5 | 4.0-6.5 |

| 19 | Camphor | 0.13 | NA | NA |

| 20 | Camphor | 0.05 | NA | NA |

| 21 | trans-Borneole | 1.04 | NA | NA |

| 22 | Terpinen-4-ol | 0.72 | 0.1-2.5 | 0.2-2.5 |

| 23 | α-Terpineol | 0.96 | NA | NA |

| 24 | Methyl carvacrol ether | 0.26 | 0.05-1.5 | NA |

| 25 | Linalyl anthranilate | 0.03 | NA | NA |

| 26 | Linalyl anthranilate | 0.06 | NA | NA |

| 27 | Thymol | 42.29 | 37.0-55.0 | 36.0-55.0 |

| Time of storage [days] |

Total number of identified compounds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EO : C | EO: MC | |||||

| 1:1 | 1:2 | 1:3 | 1:1 | 1:2 | 1:3 | |

| 0 | 16 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 27 |

| 7 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| 14 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| 28 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 56 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| No. | Chemical compouNAs | EO : C | EO : MC | EO | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 | 1:2 | 1:3 | 1:1 | 1:2 | 1:3 | ||||||

| On the day of preparation | |||||||||||

| 1 | α-Thujene | 0,39 | 0,46 | 0,41 | 0,36 | 0,35 | 0,37 | 1,28 | |||

| 2 | α-Pinene | 0,73 | 0,65 | 0,60 | 0,49 | 0,62 | 0,59 | 1,81 | |||

| 3 | Camphene | 0,52 | 0,50 | 0,59 | 0,43 | 0,41 | 0,47 | 1,08 | |||

| 4 | Myrcene | 1,52 | 1,46 | 1,83 | 1,84 | 1,71 | 1,72 | ND | |||

| 5 | γ-Terpinene | 1,14 | 1,03 | 1,46 | 1,54 | 1,88 | 2,10 | 9,04 | |||

| 6 | p-Cymene | 51,10 | 41,22 | 47,61 | 48,98 | 36,24 | 32,17 | ND | |||

| 7 | Limonene | 2,24 | 2,23 | 2,37 | 2,20 | 1,94 | 1,94 | 0,76 | |||

| 8 | α-PhellaNArene | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1,98 | 0,15 | ND | |||

| 9 | Sabinene | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1,93 | ND | |||

| 10 | 1,8-Cineoly | 2,86 | 2,21 | 3,45 | 3,27 | 1,93 | 1,93 | 0,62 | |||

| 11 | β -Ocimene | ND | 19,49 | ND | ND | 17,88 | 18,30 | ND | |||

| 12 | β -Ocimene | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0,28 | ND | |||

| 13 | γ-Terpinene | 21,38 | 19,49 | 22,12 | 20,54 | 17,88 | 16,37 | ND | |||

| 14 | Terpinolene | ND | 0,23 | 0,48 | 0,27 | 0,30 | 0,40 | ND | |||

| 15 | Linalool | 5,69 | 3,55 | 5,67 | 7,61 | 4,09 | 4,18 | 5,73 | |||

| 16 | Camphor | ND | ND | ND | 0,39 | ND | 0,17 | ND | |||

| 17 | Borneole | 0,41 | 0,18 | 0,41 | 0,50 | 0,29 | 0,24 | ND | |||

| 18 | Terpinen-4-ol | 0,33 | 0,26 | 0,48 | 0,59 | 0,36 | 0,29 | 0,72 | |||

| 19 | α-Terpineol | ND | ND | 0,23 | 0,42 | 0,15 | 0,15 | 0,96 | |||

| 20 | Methyl carvacrol ether | 0,40 | 0,24 | 0,68 | 0,44 | 0,35 | 0,56 | ND | |||

| 21 | Thymol | 2,93 | 2,52 | 3,46 | 4,17 | 3,15 | 3,75 | 42,29 | |||

| 22 | Carvacrol | ND | 0,27 | 0,23 | 0,29 | 0,22 | 0,25 | 2,87 | |||

| 23 | Kopaene | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0,13 | 0,04 | |||

| 24 | β- Caryophyllene | 7,99 | 3,74 | 7,41 | 5,43 | 7,86 | 10,56 | 2,42 | |||

| 25 | AromadeNArene | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0,16 | ND | |||

| 26 | α- Caryophyllene | 0,37 | 0,24 | 0,40 | 0,25 | 0,40 | 0,63 | 0,15 | |||

| 27 | δ-Cadinene | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0,17 | ND | |||

| After 7 days | |||||||||||

| 1 | α-Thujene | 0,31 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 2 | α-Pinene | 0,63 | ND | ND | 1,76 | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 3 | Camphene | 0,40 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 4 | Myrcene | 1,55 | ND | ND | 1,10 | 1,69 | ND | NA | |||

| 5 | p-Cymene | 58,19 | 37,35 | 46,70 | 36,80 | 48,46 | 53,63 | NA | |||

| 6 | β-Ocimene | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 7 | Limonene | 1,91 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 8 | 1,8-Cineole | 3,59 | 8,57 | 7,31 | 6,88 | 6,56 | 6,37 | NA | |||

| 9 | γ-Terpinene | 14,64 | 6,29 | 5,34 | 13,95 | 9,24 | 9,61 | NA | |||

| 10 | Linalool | 8,07 | 30,77 | 18,80 | 17,03 | 16,17 | 13,71 | NA | |||

| 11 | Camphor | 0,83 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 12 | Borneole | 0,47 | ND | 0,92 | 1,36 | 1,26 | 1,44 | NA | |||

| 13 | Terpinen-4-ol | 0,61 | ND | 2,79 | 1,70 | 1,22 | 1,28 | NA | |||

| 14 | Thymol methyl ether | 0,40 | ND | 1,07 | ND | 1,29 | ND | NA | |||

| 15 | Thymol | 4,41 | 17,01 | 14,10 | 17,34 | 9,66 | 10,17 | NA | |||

| 16 | β- Caryophyllene | 4,00 | ND | 2,97 | 2,08 | 4,45 | 3,78 | NA | |||

| After 14 days | |||||||||||

| 1 | p-Cymene | 32,75 | 9,88 | 5,21 | 20,63 | 17,18 | 7,11 | NA | |||

| 2 | 1,8-Cineole | 3,72 | 9,53 | 14,42 | 13,17 | 9,90 | 11,35 | NA | |||

| 3 | γ-Terpinene | 5,04 | ND | ND | ND | 4,09 | ND | NA | |||

| 4 | Linalool | 30,16 | 44,10 | 38,23 | 37,19 | 33,09 | 40,93 | NA | |||

| 5 | Camphor | 5,58 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 6 | Borneole | ND | ND | 3,30 | 2,32 | 4,16 | ND | NA | |||

| 7 | Terpinen-4-ol | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5,11 | ND | NA | |||

| 8 | Thymol | 22,74 | 36,49 | 38,84 | 26,69 | 26,48 | 40,61 | NA | |||

| After 28 days | |||||||||||

| 1 | p-Cymene | 5,70 | ND | 3,47 | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 2 | 1,8-Cineole | ND | 6,18 | 10,35 | 9,64 | ND | 18,06 | NA | |||

| 3 | Linalool | 44,87 | 31,32 | 43,78 | 46,97 | 43,47 | ND | NA | |||

| 4 | Camphor | 9,38 | 22,90 | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 5 | Borneole | ND | ND | 3,33 | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 6 | Thymol | 40,05 | 39,61 | 39,08 | 43,40 | 56,53 | 81,94 | NA | |||

| After 56 days | |||||||||||

| 1 | Linalool | 38,42 | 30,08 | 37,91 | 37,73 | 29,22 | 31,06 | NA | |||

| 2 | Camphor | 10,27 | 17,24 | ND | 12,60 | 11,08 | ND | NA | |||

| 3 | Borneole | ND | ND | 1,43 | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 4 | Terpinen-4-ol | 5,68 | ND | 6,32 | 6,02 | 4,32 | 12,77 | NA | |||

| 5 | α-Terpineole | ND | ND | 4,25 | ND | ND | ND | NA | |||

| 6 | Thymol | 42,41 | 52,68 | 47,98 | 39,42 | 50,58 | 56,17 | NA | |||

| 7 | Carvacrol | 3,22 | ND | 2,11 | 4,22 | 4,80 | ND | NA | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).