1. Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections (HAI) can increase the mortality and morbidity of hospitalized patients, the length of stay, and medical costs. Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) have the highest risk of HAI. According to the statistics from the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control in 2019, the HAI densities of ICU were 6.0 ‰ and 4.8 ‰in medical centers and regional hospitals, respectively. Although care bundles were applied to reduce HAI, catheter-associated urinary tract infections and bloodstream infections are still the leading causes of HAI [

1]. Daily chlorhexidine digluconate (CHG) bathing and short-course nasal mupirocin have been reported, which can effectively decrease bacteriuria and candiduria in male patients in the ICU [

2].

Chlorhexidine is a biguanide cationic antiseptic molecule, which has been used in a variety of applications for HAI prevention, including routine hand washing, pre-procedure skin preparation, indwelling catheter exit-site care, oral care for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia, and whole-body bathing. CHG is available in a range of concentrations from 0.05% to 4% (w/v) in aqueous solutions and combination with different alcohols. CHG has broad-spectrum non-sporicidal antimicrobial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, yeasts, and some lipid-enveloped viruses, including HIV. CHG is generally more active against gram-positive bacteria than gram-negative bacteria. The positively charged CHG molecule is attracted to the negatively charged phospholipids in the bacterial cell wall. At low concentrations (<0.5%), CHG is bacteriostatic, altering the cell wall and leading to loss of cell membrane integrity and leakage of intracellular components. At higher concentrations (≥0.5%) CHG is bacteriocidal, causing cell death following coagulation of the cytoplasmic components and precipitation of proteins and nucleic acid [

3]. Decolonization with topical CHG is superior to regular soap because it binds to skin proteins and continues to exert its antiseptic activities on the skin for up to 24 hours [

4].

Several meta-analyses of the effects of CHG bathing on reducing HAI have been reported, and the results showed that CHG bathing could prevent central-line associated bloodstream infections, especially Gram-positive bacteria (including methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant

Enterococci). However, the effects of catheter-associated urinary tract infections and Gram-negative bacteria are controversial [

3,

4]. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the efficacy of daily 2% CHG bathing for healthcare-associated infections (including catheter-associated bloodstream infections and urinary tract infections) and multidrug-resistant microorganisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

The prospective, uncontrolled before-and-after study was performed at a 400-bed regional hospital in 2019 in southern Taiwan, which had a 20-bed mixed medical and surgical ICU. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (approval no. KMUHIRB-E(I)-20180084). The study included all patients treated in the ICU, excluding patients with a history of hypersensitivity to CHG. The ICU physician decided whether the patient with multiple wounds or pressure sores was recruited in the study.

2.2. Intervention

1. Pre-intervention period: The daily hygiene procedure was performed by traditional liquid soap-water bathing, including the perineal area.

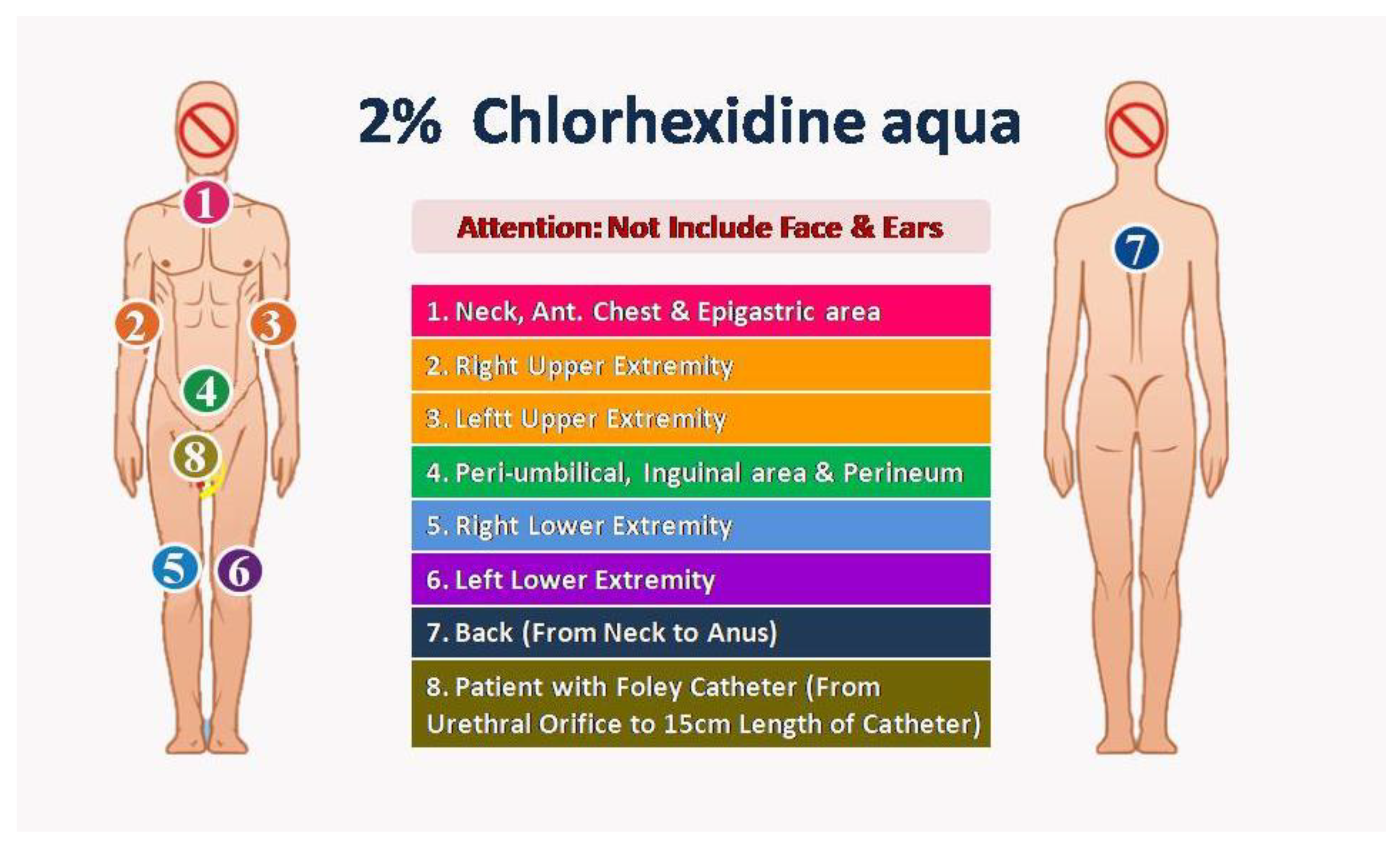

2. Intervention period: Owing to the anionic surfactant interfering with the disinfection efficacy of CHG, we used a specific anionic surfactant non-containing cleaning solution to replace traditional liquid soap before the CHG bath. Two nurses as one group performed the CHG bathing procedure with 2% CHG-impregnated wipes: Step 1, anterior surface from neck to upper abdomen; Step 2, right arm and palm; Step 3, left arm and palm; Step 4, lower abdomen, groin and perineum; Step 5, right leg and foot; Step 6, left leg and foot; Step 7, back surface from neck to anus; Step 8 (optional), external surface of urinary catheter 15cm length from urethral meatus. Because the CHG had potential toxicity to the eyes and central nervous system, we prevented contact with the eyes and external auditory canal with 2% CHG. (

Figure 1)

Before introducing the new CHG bathing procedure, we updated the standard operating procedure of daily baths for ICU patients. We made the standard procedure learning video for all the ICU nursing staff. We also checked the procedure's correctness and monitored the procedure adherence by three senior nursing staff before and during the intervention period. The study was started on January 1, 2019, and maintained for one year.

3. Post-intervention period: Owing to no obvious adverse events, the updated 2% CHF bathing procedure was continued after the study without regular external monitoring of the procedure adherence.

The demographic data was recorded, including Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation(APACHE II) score, urinary catheter and central venous catheter utilization, microbiological data, and adverse events associated with 2% CHG. The incidence rates (‰, events/1,000 patient-day) of healthcare-associated infections were diagnosed according to the Taiwan Centers for Diseases Control guideline, which was revised from the definition of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp, NY, USA). Continuous variables among different causal pathogens were analyzed with the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis Test. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test. When more than 20% of cells have expected frequencies < 5, Fisher's exact test was applied. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (two-tailed).

3. Results

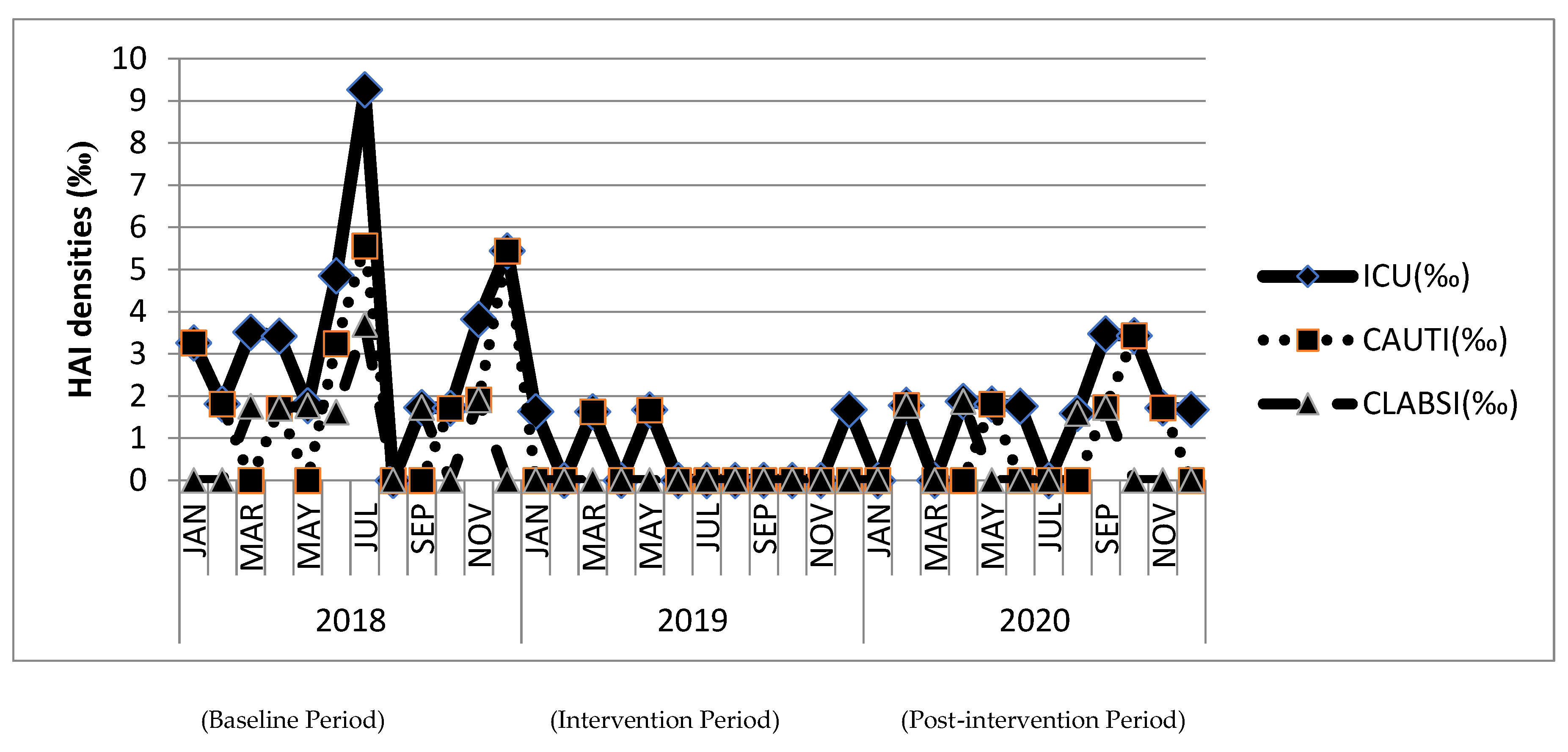

The demographic characteristics and patient severity were not significantly changed among the three study periods, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The utilization of urinary and central venous catheters was also not significantly different during the three study periods. The healthcare-associated infection incidence rates in ICU were significantly reduced after the intervention, and the efficacy was preserved during the post-intervention period (baseline period: 3.43‰; intervention period: 0.58‰,

p<0.05 compared with baseline; post-intervention period: 1.59‰,

p<0.05 compared with baseline). Overall urinary tract infection (baseline: 2.09‰ vs. intervention: 0.43‰,

p<0.05) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection incidence rates (baseline: 2.09‰ vs. intervention: 0.28‰,

p<0.05) were significantly reduced during intervention period with comparison on baseline period. The incidence rates of urinary tract infection and catheter-associated urinary tract infection were raised slightly (both: 0.87‰) during the post-intervention period without statistical significance between the intervention periods. Overall bloodstream infection (baseline: 1.19‰ vs. intervention: 0.14‰,

p<0.05) and catheter-associated bloodstream infection incidence rates (baseline: 1.18‰ vs. intervention 0.00‰,

p<0.05) were significantly reduced during intervention period with comparison on baseline period. The incidence rates of bloodstream infection and catheter-associated bloodstream infection were raised slightly (both: 0.72‰) during the post-intervention period without statistical significance between the intervention periods. (

Figure 2 and

Table 1)

The bacterial isolates number of multidrug-resistant microorganisms was also significantly reduced, not only Gram-positive bacteria (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci, 13 to 1) but also Gram-negative bacteria (carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, 35 to 12) after the intervention. The bacterial isolates number of multidrug-resistant microorganisms from sputum, urine, and blood specimens was also significantly reduced after intervention (sputum: 23 to 11; urine: 4 to 0; blood: 14 to 2, respectively). The effects can be persistent till the post-intervention period.

4. Discussion

Daily 2% CHG bathing can significantly reduce the overall incidence of healthcare infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and bloodstream infections among ICU patients. The number of multidrug-resistant microorganism infections also decreased. No adverse events related to CHG bathing were observed. Although the infection incidence rates rose slightly during the post-intervention period, the efficacy was preserved after the intervention without intensive monitoring.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analysis reports have addressed the issue of implementing CHG bathing for ICU patients to prevent urinary tract infections. The inclusion criteria (only randomized control trials or combined observational studies) and analysis method of outcomes were various among these reports. Four systematic reviews revealed no significant change in risk reduction of overall or catheter-associated urinary tract infections [

5,

6,

8,

9]. One report favored daily CHG bathing as beneficial for preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections [

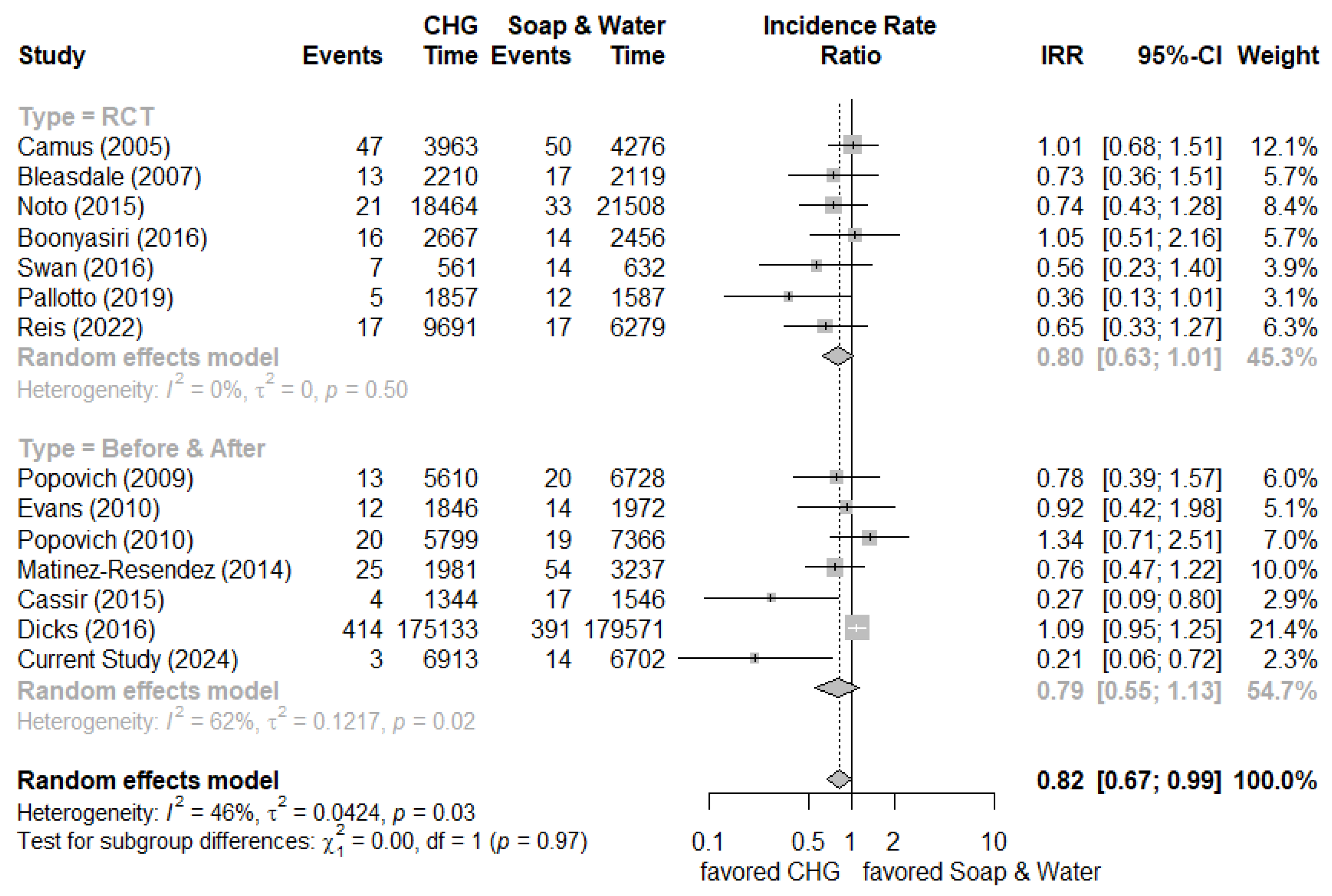

10]. We added newly published clinical studies (including randomized control trials and before-and-after studies) and our current study results to generate new meta-analysis results [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. It showed the overall incidence rate ratio was 0.82 (95% confidence interval (C.I.) 0.67-0.99) by random effect model (randomized control trials: 0.80 [95% C.I. 0.63-1.01] and before-and-after studies: 0.79 [95% C.I. 0.55-1.13], respectively) which indicated marginal effect on reducing the incidence of urinary tract infection (

Figure 3). The meta-analysis focusing on daily CHG bathing to reduce Gram-negative infections was also insignificant [

24]. Why did our study show a 79% risk reduction of urinary tract infection incidence? Although cleaning the periurethral area with antiseptics is not recommended to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections, routine hygiene is recommended according to current guidelines. The proposed mechanism of CHG for preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections was the reduction of microbial flora in the perineum, periurethral tissue, and urinary catheter surface by the prolonged and residual effects of CHG, which reduced the risk of colonization and subsequent infection from manipulation of urinary catheter [

4,

25]. Generally, the 4% CHG solution was applied and then rinsed off in the shower, while 2% CHG is used as leave-on products (CHG-impregnated clothes or wipes) for bathing. The 2% CHG leave-on product is favored because it results in high residual concentrations of CHG on the skin, which can provide germicidal activity for up to 24 hours [

4]. The presence of organic material reduces the effectiveness of CHG. Besides, the anionic surfactant would interfere with the disinfective efficacy of CHG. We used a specific anionic surfactant non-containing cleaning solution instead of traditional liquid soap to remove excess organic substance on the skin surface before CHG bathing, which may enhance the effect of CHG. We also reinforced the cleaning of the perineum with the additional cleaning on the external surface of the urinary catheter 15cm in length from the urethral meatus, which may have had the effect of meatal cleaning [

7]. The advantage of our study included the package of 2% CHG-impregnated clothes, specific anionic surfactant non-containing cleaning solution, and enhanced perineum cleaning with additional cleaning on the external surface of the urinary catheter 15cm length from the urethral meatus. Further well-designed randomized control trials are needed to confirm the effectiveness of daily CHG bathing for preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

Compliance also plays a vital role in the effectiveness of CHG bathing. Assessing and monitoring adherence and skillful quality are crucial for success. We did the quality assessment after staff training and before clinical application, which made the implementation of daily CHG bathing for ICU patients a great success. Still, the healthcare-associated infection incidence rates slightly rose during the post-intervention period, which reflected that intensive monitoring and annual refresher training were necessary.

The widespread use of CHG has raised concerns about resistant emergence and the cross-resistance to other antimicrobials. Wand et al. showed that the adaptation of

Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates to CHG exposure led to an increase of minimal inhibitory concentration values for colistin from 2-4 mg/L to >64 mg/L [

26]. Intrinsic microbial resistance to CHG is partly due to bacterial degradative enzymes and cellular impermeability. It explained the reason for less CHG susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria. Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with reduced CHG susceptibility have been identified, partly due to efflux pumps. However, inconsistencies in testing methods (including phenotype and genotype) make it difficult to assess the broader impact of CHG use on resistance. Despite these concerns, most evidence suggests that the risk of significant bacterial resistance from CHG is low and should not be prevented from its use in preventing healthcare-associated infections. Continued research and standardized testing are needed, but the benefits of CHG in clinical settings remain great [

27,

28].

Our study results showed no adverse events related to CHG bathing were observed. However, adverse reactions to CHG involved immediate IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity and delayed cutaneous T cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity, ranging from mild contact dermatitis to anaphylaxis or death, especially due to CHG-coating central venous catheter. Pre-procedure compatibility checks, history taking, and increased awareness of CHG hypersensitivity should be cautious while implementing CHG daily bathing in clinical practice [

29].

The present study had several limitations. First, there were only 20 beds in our ICU. We were unable to perform a randomized control trial, and we used a before-and-after study design with historical control. Second, this is only a single-center small sample study. However, the study had some strengths. We applied a specific anionic surfactant non-containing cleaning solution before 2% CHG daily bathing and enhanced perineum cleaning with additional cleaning on the external surface of the urinary catheter 15cm in length from the urethral meatus. The intervention was started after well-trained and certificated nursing staffs. They all contributed to our study's significant reduction of catheter-associated urinary tract infection incidence.

5. Conclusions

The present study demonstrated the implementation of daily 2% CHG bathing can significantly reduce the overall healthcare infection incidence rates, catheter-associated bloodstream infections, and catheter-associated urinary tract infections among ICU patients, which was controversial in the prior meta-analyses. The number of multidrug-resistant microorganism infections also decreased. Further well-designed, multicenter randomized control trials are needed to consolidate the effectiveness of daily CHG bathing for preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

Authors’ contributions: Conceptualization, H.-L. C., T.-Y. L., and T.-C. C.; methodology, T.-Y. L., H.-Z. C., and T.-C. C.; data collection, P.-S. H., C.-W. C., and C.-W. Y.; data analysis, T.-Y. L., and T.-C. C.; manuscript drafting, H.-L. C., and T.-C. C.; manuscript review and editing, S.-H. K., S.-Y. L., and P.-L. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital (kmtth-104-019, kmtth-107-040, kmtth-107-045, kmtth-109-001, kmtth-109-030).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (approval no. KMUHIRB-E(I)-20180084).

Data Availability statement: Not applicable for that section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Taiwan Centers for Diseases Control. Annual Report of Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System(2019). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Category/Page/J63NmsvevBg2u3I2qYBenw (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Huang, S.S.; Septimus, E.; Hayden, M.K.; Kleinman, K.; Sturtevant, J.; Avery, T.R.; et al. Effect of body surface decolonisation on bacteriuria and candiduria in intensive care units: An analysis of a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouadma, L.; Karpanen, T.; Elliott, T. Chlorhexidine use in adult patients on ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 2232–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.S. Chlorhexidine-based decolonization to reduce healthcare-associated infections and multidrug resistant organisms (MDROs): Who, what, where, when, and why? J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 103, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, S.A.; Hou, Y.C.; Lombardo, L.; Metcalfe, L.; Lynch, J.M.; Hunt, L.; et al. Evidence for the effectiveness of chlorhexidine bathing and health care-associated infections among adult intensive care patients: A trial sequential meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.R.; Schofield-Robinson, O.J.; Rhodes, S.; Smith, A.F. Chlorhexidine bathing of the critically ill for the prevention of hospital-acquired infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, CD012248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasugba, O.; Cheng, A.C.; Gregory, V.; Graves, N.; Koerner, J.; Collignon, P.; et al. Chlorhexidine for meatal cleaning in reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: A multicentre stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, S.A.; Alogso, M.C.; Metcalfe, L.; Lynch, J.M.; Hunt, L.; Sanghavi, R.; et al. Chlorhexidine bathing and health care-associated infections among adult intensive care patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Song, R. Effect of 2% chlorhexidine bathing on the incidence of hospital-acquired infection and multidrug-resistant organisms in adult intensive care unit patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2021, 4, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.P.; Chen, B.; Wang, H.Y.; He, M. The efficacy of daily chlorhexidine bathing for preventing healthcare-associated infections in adult intensive care units. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, C.; Bellissant, E.; Sebille, V.; Perrotin, D.; Garo, B.; Legras, A.; et al. Prevention of acquired infections in intubated patients with the combination of two decontamination regimens. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 33, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleasdale, S.C.; Trick, W.E.; Gonzalez, I.M.; Lyles, R.D.; Hayden, M.K.; Weinstein, R.A. Effectiveness of chlorhexidine bathing to reduce catheter-associated bloodstream infections in medical intensive care unit patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 2073–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noto, M.J.; Domenico, H.J.; Byrne, D.W.; Talbot, T.; Rice, T.W.; Bernard, G.R.; et al. Chlorhexidine bathing and health care-associated infections: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015, 313, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonyasiri, A.; Thaisiam, P.; Permpikul, C.; Judaeng, T.; Suiwongsa, B.; Apiradeewajeset, N.; et al. Effectiveness of chlorhexidine wipes for the prevention of multidrug-resistant bacterial colonization and hospital-acquired infections in intensive care unit patients: A randomized trial in Thailand. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, J.T.; Ashton, C.M.; Bui, L.N.; Pham, V.P.; Shirkey, B.A.; Blackshear, J.E.; et al. Effect of chlorhexidine bathing every other day on prevention of hospital-acquired infections in the surgical ICU: A single-center, randomized controlled trial. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotto, C.; Fiorio, M.; De Angelis, V.; Ripoli, A.; Franciosini, E.; Quondam Girolamo, L.; et al. Daily bathing with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate in intensive care settings: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.A.O.; de Almeida, M.C.S.; Escudero, D.; Medeiros, E.A. Chlorhexidine gluconate bathing of adult patients in intensive care units in Sao Paulo, Brazil: Impact on the incidence of healthcare-associated infection. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 26, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovich, K.J.; Hota, B.; Hayes, R.; Weinstein, R.A.; Hayden, M.K. Effectiveness of routine patient cleansing with chlorhexidine gluconate for infection prevention in the medical intensive care unit. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2009, 30, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.L.; Dellit, T.H.; Chan, J.; Nathens, A.B.; Maier, R.V.; Cuschieri, J. Effect of chlorhexidine whole-body bathing on hospital-acquired infections among trauma patients. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovich, K.J.; Lyles, R.; Hayes, R.; Weinstein, R.A.; Hayden, M.K. Daily skin cleansing with chlorhexidine did not reduce the rate of central-line associated bloodstream infection in a surgical intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2010, 36, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reséndez, M.F.; Garza-González, E.; Mendoza-Olazaran, S.; Herrera-Guerra, A.; Rodríguez-López, J.M.; Pérez-Rodriguez, E.; et al. Impact of daily chlorhexidine baths and hand hygiene compliance on nosocomial infection rates in critically ill patients. Am. J. Infect. Control 2014, 42, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassir, N.; Thomas, G.; Hraiech, S.; Brunet, J.; Fournier, P.E.; La Scola, B.; et al. Chlorhexidine daily bathing: Impact on healthcare-associated infections caused by gram-negative bacteria. Am. J. Infect. Control 2015, 43, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicks, K.V.; Lofgren, E.; Lewis, S.S.; Moehring, R.W.; Sexton, D.J.; Anderson, D.J. A multicenter pragmatic interrupted time series analysis of chlorhexidine gluconate bathing in community hospital intensive care units. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Parikh, P.; Dunn, A.N.; Otter, J.A.; Thota, P.; Fraser, T.G.; et al. Effectiveness of daily chlorhexidine bathing for reducing gram-negative infections: A meta-analysis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denny, J.; Munro, C.L. Chlorhexidine bathing effects on health-care-associated infections. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2017, 19, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wand, M.E.; Bock, L.J.; Bonney, L.C.; Sutton, J.M. Mechanisms of increased resistance to chlorhexidine and cross-resistance to colistin following exposure of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates to chlorhexidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01162–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Poel, B.; Saegeman, V.; Schuermans, A. Increasing usage of chlorhexidine in health care settings: Blessing or curse? A narrative review of the risk of chlorhexidine resistance and the implications for infection prevention and control. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, A.; Lutgring, J.D.; Fridkin, S.; Hayden, M.K. Assessing the potential for unintended microbial consequences of routine chlorhexidine bathing for prevention of Healthcare-associated Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiewchalermsri, C.; Sompornrattanaphan, M.; Wongsa, C.; Thongngarm, T. Chlorhexidine allergy: Current challenges and future prospects. J. Asthma Allergy 2020, 13, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).