Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Methods

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

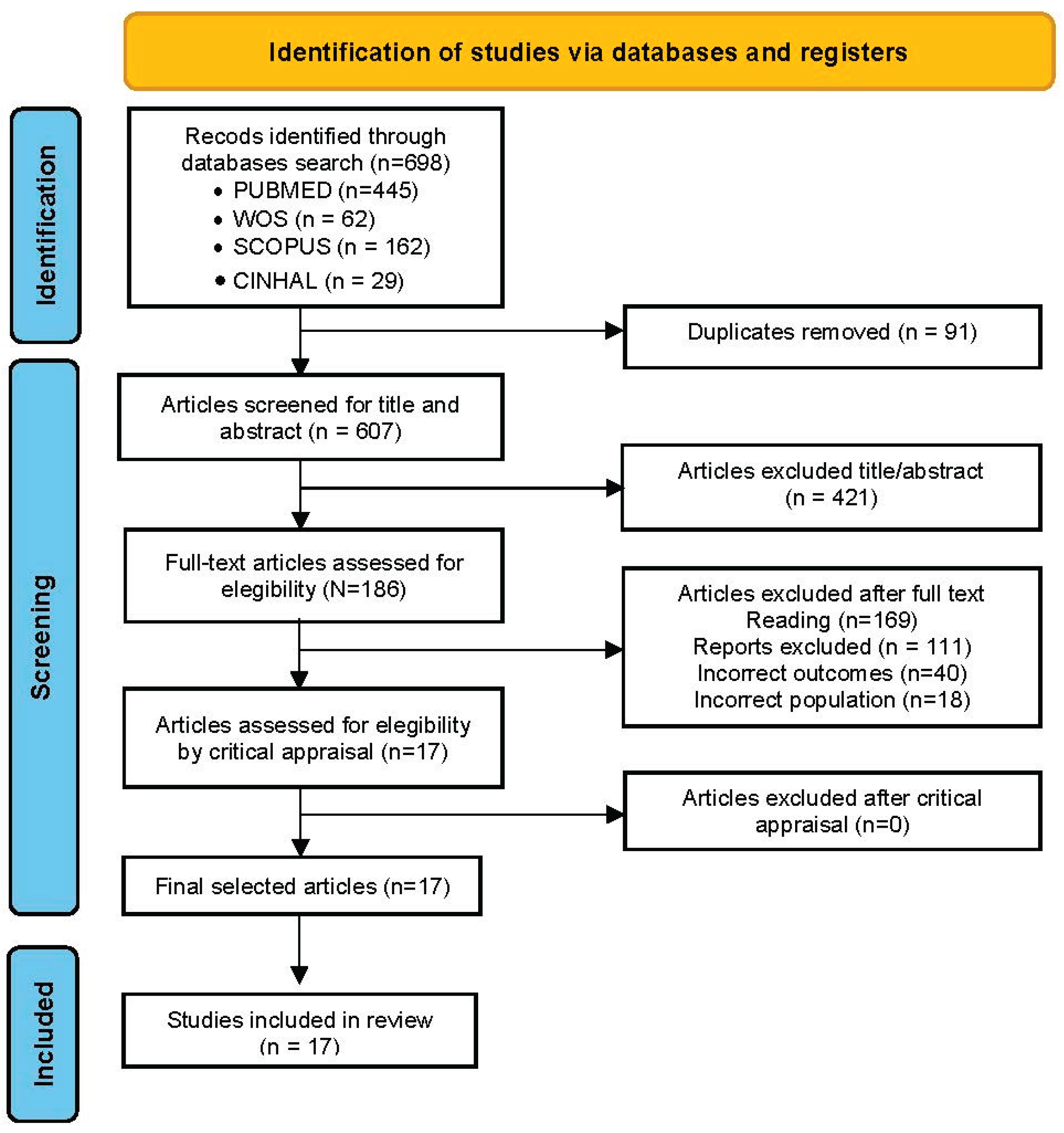

2.4. Search Results

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.8. Rigour

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and School Physiotherapy: Separated by a Fine Line

Well, what’s the most important thing here? Is it the standing? Is it the education? Is it this bit? Is it that bit?” … It’s a very fine balancing line … constant battle between therapy and education.[28]

I’ve been a PT for 27 years but I’ve only been in the schools for about 14. Certainly, coming from a clinic model, my first couple of years in the schools I had a really hard time to figure out how to make goals that were school-based…[35]

We’re looking at supporting students in special education and benefiting from those services; we’re looking at accessing educational environments and students participating with their peers in motor activities.[35]

3.1.1. Lack of Specific Guidelines

I like that it gives nice clarity around the scope of work for a school-based physiotherapist.[8]

Sometimes because of the wording, complexity and differences between countries, PTs might feel so overwhelmed.[8]

3.1.2. Professional Competencies and Diffuse Responsibility

Actually, it is everyone’s responsibility, so when everyone is responsible, no one takes responsibility.[19]

3.1.3. Lack of Support: Feeling Like Outsiders

Most of the focus [in our school] is on education and therapists are excluded from the decisions [physiotherapist not consulted to share their views] by the DoE. … To date we do not have job descriptions and are understaffed.[7]

Physiotherapy is secondary in the education system, even within the health professions… everyone needs to talk, so they [the students] receive speech therapy… everyone needs to write and hold a pencil, so who will teach them? An occupational therapist… and due to various misconceptions, the OT will also examine motor performance. So why bring in another clinician?[19]

3.1.4. Professional Intrusion

There is a big problem with physiotherapy professional boundaries: where do they begin and end, who needs physiotherapy, who should be referred to a physiotherapy… I mean, it is unclear to the public but also to therapists, when should a physiotherapy or occupational therapist be consulted?...[19]

3.1.5. Pupil-Centred, Evidence Based

And I don’t know that there is really one great way to write goals but making sure that they’re measurable and you can actually keep data on those goals.[35]

So, if it was a clickable link, if it was an interactive document, we could digitally find more of the information in it.[8]

3.2. Ensuring Healthcare for Children with Specific Conditions in Schools

3.2.1. Care for Pupils with Cerebral Palsy

She was walking longer on the treadmill and riding her bike faster for longer periods.[16]

I think that open friendliness, that it being a little bit social as well as exercise, was a great aspect of it. And so that would make it easier for them to join in.[16]

3.2.2. Supervising Pupils Using Standing Frames

If the children have got a lot of extraneous movement and they’re agitated, you can end up with friction burns … Sometimes it actually depends if they’ve got their second skin (dynamic lycra body suit) on, if they are tired … So you have to really know your children and know what mood they’re in as well.[28]

3.2.3. Implementing Aquatic Therapy Programmes

It is an environment where it is easier to mobilize compared to dry land conditions, so, first you see what the person can do regarding mobility in the water, and then this can be applied in the classroom or the dining room, encouraging us to reinforce this.[29]

They pay more attention to conversations as soon as they get into the water, and then they react in the playground when something seems funny or interesting to them, they are more awake than before they get into the water.[29]

3.2.4. Prevention and Treatment of Back Problems/Pain

The workshops have helped me to change, I have truly felt that they have been useful. In my daily life, this is noticeable and little by little, the back ache that I had starts to go away.[36]

I have found it very useful because before I would carry my backpack down by my bum and I would struggle, and it was hell and suddenly you said I should raise it higher, and I thought to myself “it doesn’t weigh a thing! I was very surprised.[36]

The teachers aren’t taught about spinal health and what’s good for children and bad.[30]

3.2.5. Care and Prevention of Complications from Spinal Cord Injuries

[Assistance through physiotherapists] … there should be the likes of … the help of the hospital physiotherapist, and the school, and other special schools, we will manage.[37]

3.2.6. Applying Mind-Body Therapies

For example, when doing homework, they can focus more; they used to chatter a lot. They can sit better and have a better posture. Like, in sorting out arguments and stuff, they already talk about it differently, and at some point, you gotta say, “F [referring to the physical therapist] comes with this and that…” [referring to the fact that she reminds them of what they’ve learned with the physical therapist, and it’s helped them to chill out].[38]

3.2.7. Addressing Minor Motor Limitations

Children with DCD are not eligible for physiotherapy at school or child development centers after the age of 6.[19]

I hope older children receive services at school. I hope, but I’m not sure it happens, and I am not sure it’s enough.[19]

3.3. The Challenge of Incorporating SP in Educational Settings

3.3.1. Integrating Therapy Into Curriculum

The most important thing is that the school has specialists . . . because if it didn’t then the opportunity to do physical activity would be limited.[39]

. . . if she [physiotherapist] says ‘come on I want you to get up and go and walk around the school seven times’, [name] will go ‘okay, I’ll do it eight times for you’.[39]

3.3.2. Meeting Physiotherapy Needs in Special (and Regular) Education Schools

Our work has to be done, books has to be marked, assessments have to be done and marked and moderated and all of those so we don’t have time. We can’t worry about their spines because we are worried about what they’re learning.[40]

Implementing this model to mainstream schools means that physical therapists should be in the general (mainstream schools), and so it’s kind of new thought, so I think it’s going to be challenging.[8]

Children with motor disabilities receive physiotherapy in special education schools. I don’t know whether to say that it is full, but certainly in special education schools there are physiotherapists who take care of these children... those in mainstream education should also receive physiotherapy at school, but it doesn’t always happen. And if not in school, then where do they get it, I don’t know.[19]

3.3.3. Training Teachers and Other Professionals

And it is perfect that in parallel to this, F [the physical therapist] is also training us teachers, so I think it is an action, and the good thing is that it is a very global intervention and that it is not isolated and so on… Yes, so I think it is important. I also think it is important that we can introduce it, as I said, in a transversal way in the curriculum, that teachers are given the tools to be able to do this.[38]

I conduct 99% of the child’s training, and that doesn’t feel right. But, she’s in massive need of physiotherapy, so I do it for her [the child].[41]

3.3.4. Integrating into Multidisciplinary Teams

We’ve all got the same goals. I obviously fight for the education, physio fights for the physio, but I’m very mindful that there’s no point just doing 100% education in school. You need to have some therapy as well.[28]

We work really hard to integrate goals … so that the teacher … or the staff can do it after we’re gone. So that they’re working on that same goal every day and not just when we’re there.[35]

I definitely want their [students’] input [on goal development] because … if they don’t buy into it, you’re not going to go anywhere with it anyway. I like them to come up with ideas of what problems they are having with their disability and … work with them on learning what their disability is … and how we can work on it.[42]

3.3.5. Accompanying, Treating, and Supervising in Natural Settings

By working in a school, physiotherapists have the opportunity to monitor the children’s progress over time and detect any signs of decline before they become more serious.[19]

3.3.6. Overcoming Setbacks and Coping with Difficulties

I think you really have to collaborate with the other members of the team … we can’t be with a child all day every day. We don’t see the entire school day. We have lots of kids to serve … I think of specifically our kids who have a Physical Needs Assistant. That person is with them all day every day and is focused just on that one student.[42]

Some of the kids are bigger than I am and they get to the stage where they - if they’ve got knee flexion contractures, if it’s uncomfortable and they don’t want to do it, then they on’t do it.[28]

Related to this, some respondents from academia said it is increasingly difficult to secure good-quality rotations, especially in highly specific or innovative areas.[44]

There will be staff that will be threatened there will be teachers that are threatened! there will be occupational therapist that is threatened… it will be a real risk to implementation of this model if it’s not done correctly.[8]

Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WCPT (World Confederation for Physical Therapy). Policy Statement: Education. Proceedings of World Confederation for Physical Therapy, Geneve, UK, 2019, May 10-13.

- Cánovas, I.M.; Salazar, J. Fisioterapia Educativa: el papel del fisioterapeuta en la mejora de la coordinación óculomanual: un protocolo de intervención”. Fisioterapia y calidad de vida 2002, 1, 26–48. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn, G.; Maher, L. Assessment of school students’ needs for therapy services. Au J Physiother 1993, 39, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekerak, D.M.; Kirkpatrick, D.B.; Nelson, K.C.; Propes, J.H. Physical therapy in preschool classrooms: successful integration of therapy into classroom routines. Pediatr Phys Ther 2003, 15, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minghelli, B. School physiotherapy programme: Improving literacy regarding postures adopted at home and in school in adolescents living in the south of Portugal. Work 2020, 67, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.; Stern, P.; Marchetti, G.; Provident, I.; Turocy, P.S. School-based pediatric physical therapists’ perspectives on evidence-based practice. Pediatr Phys Ther 2008, 20, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manamela, M.C.; Eksteen, C.A.; Mtshali, B.; Olorunju, S.A.S. South African physiotherapists’ perspectives on the competencies needed to work in special schools for learners with special needs. S Afr J Physiother 2021, 77, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, E.; Anaby, D.; Dostie, R.; PRISE-PT Network, Camden, C. Perspectives of international experts on collaborative tiered school-based physiotherapy service delivery. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2022, 42, 595–614. [CrossRef]

- Lins, F.T.; Medeiros, A.P. School inclusion of students with physical disabilities: perceptions of teachers regarding the physiotherapist´s professional cooperation. Rev. Bras. Ed. Esp. 2013, 19, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- CGCFE (Consejo General de Colegios de Fisioterapéutas de España). Documento Marco de Fisioterapia en Educación. Available online: https://www.consejo-fisioterapia.org/adjuntos/publicaciones/publicacion_3.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Figl-Hertlein, A.; Horsak, B.; Dean, E.; Schöny, W.; Stamm, T. A physiotherapy-directed occupational health programme for Austrian school teachers: a cluster randomised pilot study. Physiotherapy 2014, 100, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford, B.; Clarke, S.; Maddison, J. Therapy interventions for children with neurodisabilities: a qualitative scoping study. Health Technol Assess 2018, 22, 1–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartikainen, J.; Haapala, E.A.; Poikkeus, AM.; Sääkslahti, A.; Laukkanen, A.; Gao, Y.; Finni, T. Classroom-based physical activity and teachers’ instructions on students’ movement in conventional classrooms and open learning spaces. Learning Environ Res. 2023, 26, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronca, F.; Burgess, P.W.; Savage, P.; Senaratne, N.; Watson, E.; Loosemore, M. Decreasing sedentary time during lessons reduces obesity in primary school children: the active movement study. Obes Facts 2024, 17, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Temesgen, M.H.; Belay, G.J.; Gelaw, A.Y.; Janakiraman, B.; Animut, Y. Burden of shoulder and/neck pain among school teachers in Ethiopia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, S.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Dodd, K.J.; Shields, N. A qualitative evaluation of an aerobic exercise program for young people with cerebral palsy in specialist schools. Dev Neurorehabil 2017, 20, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larose, D.; Massie, C.L.; St-Aubin, A.; Boulay-Pelletier, V.; Boulanger, E.; Lavoie, M.D.; Yessis, J.; Tremblay, A.; Drapeau, V. Effects of flexible learning spaces, active breaks, and active lessons on sedentary behaviors, physical activity, learning, and musculoskeletal health in school-aged children: a scoping review. J Act Sedentary Sleep Behav 2024, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajacova, A.; Lawrence, E.M. The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annu Rev Public Health 2018, 39, 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Waiserberg, N.; Horev, T.; Feder-Bubis, P. "When everyone is responsible, no one takes responsibility": exploring pediatric physiotherapy services in Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, L.M.; McCoy, S.W.; Effgen, S.K.; Chiarello, L.A.; Villasante, A.G. Description of the services, activities, and interventions within school-based physical therapist practices across the United States. Phys Ther 2019, 99, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger, V.D.; Jeffries, L.M.; Effgen, S.K.; Chen, S.; Arnold, S.H. School-Based Physical Therapy Services: predicting the gap between ideal and actual embedded services. Pediatr Phys Ther 2020, 32, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Dissing, K.B.; Hartvigsen, J.; Wedderkopp, N.; Hestbæk, L. Conservative care with or without manipulative therapy in the management of back and/or neck pain in danish children aged 9-15: a randomised controlled trial nested in a school-based cohort. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnuff, J.; Gibson, J.L.; Webster, R.; Kaur-Bola, K.; Crombie, S.; Grayston, A.; Pennington, L. School-based allied health interventions for children and young people affected by neurodisability: a systematic evidence map. Disabil Rehabil. 2023, 45, 1239–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, D.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Effectiveness of school-based interventions on fundamental movement skills in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2025, 25, 1522. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.E.; Clutterbuck, G.L.; Johnston, L.M. Effectiveness of school-based physiotherapy intervention for children. Disabil Rehabil 2025, 47, 1872–1892. [Google Scholar]

- Vialu, C.; Doyle, M. Determining need for school-based physical therapy under idea: commonalities across practice guidelines. Pediatr Phys Ther 2017, 29, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Webb, C.; Anderson, J. The relevance of education training for therapists in promoting the delivery of holistic rehabilitation services for young school children with disabilities in Hong Kong. Disabil Rehabil 2003, 25, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, J.; Lecouturier, J.; Smith, J.; Crombie, S.; Basu, A.; Parr, J.R.; Howel, D.; McColl, E.; Roberts, A.; Miller, K.; et al. Understanding frames: A qualitative exploration of standing frame use for young people with cerebral palsy in educational settings. Child Care Health Dev 2019, 45, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Blanco, E.; Merino-Andrés, J.; Aguilar-Soto, B.; García, Y.C.; Puente-Villalba, M.; Pérez-Corrales, J.; Güeita-Rodríguez, J. Influence of aquatic therapy in children and youth with cerebral palsy: a qualitative case study in a special education school. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3690. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, Q.; Kriel, R.I.; Brink, Y.; van Niekerk, S.M.; Tawa, N. Perspectives of spinal health within the school setting in a South African rural region: A qualitative study. Work 2021, 69, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute). Checklist for Qualitative Research. 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Wynarczuk, K.D.; Chiarello, L.A.; Fisher, K.; Effgen, S.K.; Palisano, R.J.; Gracely, E.J. School-based physical therapists’ experiences and perceptions of how student goals influence services and outcomes. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2019, 39, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Morales, M.; Abuín-Porras, V.; Romero-Morales, C.; de la Cueva-Reguera, M.; De-La-Cruz-Torres, B.; Rodríguez-Costa, I. Implementation of a classroom program of physiotherapy among spanish adolescents with back pain: a collaborative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, U.S.; Mathye, D. Peer support as pressure ulcer prevention strategy in special school learners with paraplegia. S Afr J Physiother 2024, 80, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Sierra, Y.; Trapero-Asenjo, S.; Rodríguez-Costa, I.; Granero-Heredia, G.; Pérez-Martin, Y.; Nunez-Nagy, S. Experiences of second-grade primary school children and their teachers in a mind-body activity program: a descriptive qualitative study. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, S.; Taylor, N.F.; Dodd, K.J.; Shields, N. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity for children with cerebral palsy in special education. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, D. & Louw, Q. Primary school learners’ movement during class time: perceptions of educators in the Western Cape, South Africa. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2501. [Google Scholar]

- Sørvoll, M.; Obstfelder, A.; Normann, B.; Øberg, G.K. Perceptions, actions and interactions of supervised aides providing services to children with cerebral palsy in pre-school settings: a qualitative study of knowledge application. Eur J Physiother 2018, 20, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynarczuk, K.D.; Chiarello, L.A.; Fisher, K.; Effgen, S.K.; Palisano, R.J.; Gracely, E.J. Development of student goals in school-based practice: physical therapists’ experiences and perceptions. Disabil Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3591–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandal, A.; Østerås, B.; Söderström, S. The multifaceted role of physiotherapy - a qualitative study exploring the experiences of physiotherapists working with adolescents with persistent pain. Physiother Theory Pract 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, D.M. physiotherapists’ perspectives on the threats posed to their profession in the areas of training, education, and knowledge exchange: a pan-canadian perspective from the Physio Moves Canada Project, Part 1. Physiother Can 2020, 72, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly-Smith, A.J.; Zwolinsky, S.; McKenna, J.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Defeyter, M.A.; Manley, A. Systematic review of acute physically active learning and classroom movement breaks on children’s physical activity, cognition, academic performance and classroom behaviour: understanding critical design features. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018, 4, e000341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, E.; van Steen, T.; Direito, A.; Stamatakis, E. Physically active lessons in schools and their impact on physical activity, educational, health and cognition outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, J.; Hollweck, T. Inclusion and equity in education: Current policy reform in Nova Scotia, Canada. Prospects 2020, 49, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamphorst, E.; Cantell, M.; Van Der Veer, G.; Minnaert, A.; Houwen, S. Emerging school readiness profiles: Motor skills matter for cognitive- and non-cognitive first grade school outcomes. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 759480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortnum, K.; Furzer, B.; Reid, S.; Jackson, B.; Elliott, C. The physical literacy of children with behavioural and emotional mental health disorders: A scoping review. Ment Health Phys Act 2018, 15, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effgen, S.K.; McCoy, S.W.; Chiarello, L.A.; Jeffries, L.M.; Starnes, C.; Bush, H.M. Outcomes for students receiving school-based physical therapy as measured by the school function assessment. Pediatr Phys Ther 2016, 28, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.L.; Kuperstein, J.; Effgen, S.K. Physical therapists’ perceptions of school-based practices. Physical & Occupational Theraphy Pediatrics 2015, 35, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

| Article | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleary et al. (2017) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Sørvoll et al (2018) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ |

| Cleary et al. (2019) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Goodwin et al (2019) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Wynarczuk et al. (2019) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ |

| Muñoz-Blanco et al. (2020) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Walton (2020) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Blanco-Morales et al (2020) | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Wynarczuk et al. (2020) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Manamela et al. (2021) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Louw et al., (2020) | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Cinar et al. (2022) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| López-Sierra et al., (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Fisher & Lown (2023) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Rauter & Mathye (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Waiserberg et al (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Kandal et al (2025) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Stage | Description | Steps |

|---|---|---|

| STAGE 1 | Text coding | Recall review question Read/re-read findings of the studies Line-by-line inductive coding Review of codes in relation to the text |

| STAGE 2 | Development of descriptive themes | Search for similarities/differences between codes Inductive generation of new codes Write preliminary and final report |

| STAGE 3 | Development of analytical themes | Inductive analysis of sub-themes Individual/independent analysis Pooling and group review |

| Author and Year | Country | Sample | Design | Data collection |

Data analysis |

Main Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleary et al. (2017) | Australia | Childs (8), parents (7), teachers (6), PT (7) | Qualitative descriptive study | SSI | Thematic analysis | Benefits of an aerobic exercise programme for children with cerebral palsy |

| Sørvoll et al. (2018) | Norway | PTA (7), PT (7), Child (7) | Qualitative interpretative study | STI, observation | Theme-based content analysis | Delegating formal knowledge to non-professionals is problematic |

| Cleary et al. (2019) | Australia | Child (10), parents (13), teachers (27), PT (23) |

Qualitative descriptive study | FGs | Thematic analysis | Physical activity programmes need to take into consideration complexities |

| Goodwin et al. (2018) | UK | PT (9), EP (8), parents (9), Mixed (17) |

Qualitative study | FGs | Framework method | Training is required to ensure staff are competent in using the standing frame |

| Wynarczuk, et al. (2019) | USA | PT (20) | Qualitative descriptive study | FGs | Thematic analysis | Individualized goals influence services and optimize student outcomes. |

| Muñoz-Blanco et al. 2020 | Spain | Child CP (14), parents (8), EP (2), PT (3) |

Qualitative case study with embedded units | Non-participant observations, IDI, FGs | Thematic analysis | Aquatic therapy is an alternative treatment approach which can be applied in schools |

| Walton (2020) | Canada | PTs (116) | Qualitative study | FGs, IDI | Thematic analysis | Opportunities and threats for the development of physiotherapy |

| Blanco-Morales et al. (2020 | Spain | Child (49) Teachers (9), family (11), PT (9) | Collaborative action research | IDI, FGs, reflexive diaries, field notes | Inductive analysis | Physiotherapy activities o er students new tools to decrease their back pain and improve their health |

| Wynarczuk, et al. (2020) | USA | PT (20) | Qualitative descriptive study | FGs | Thematic analysis |

Help educational teams reflect on goal development processes |

| Manamela et al. (2021) | South Africa |

PT (22) | Mixed method research |

FGs | Thematic analysis |

Educational policies in classroom in the special educational environment |

| Louw et al. (2021) | South Africa |

Child (43), parents (17), Teachers (33) | Qualitative descriptive study | IDIs, FGs | Inductive analysis | There is a need for further engagement on school-based spinal health promotion programs |

| Cinar et al., (2022)] | Different countries (8) | PT (38) | Qualitative study | FGs | Framework method | Perspectives regarding a proposed collaborative tiered school-based PT service |

| López-Sierra et al. (2024) | Spain | Child (43), teachers (2) |

Qualitative descriptive study | IDIs, FGs | Thematic analysis | Importance of physiotherapy interventions in the school environment |

| Fisher & Lown (2023) | South Africa |

Principal (13), teachers (24) |

Qualitative descriptive study | IDIs, FGs | Inductive analysis | Policy should support teachers in implementing movement strategies in-classroom |

| Rauter & Mathye (2024) | South Africa |

Child (12) | Qualitative descriptive study | IDIs, FGs | Thematic analysis | Physiotherapists in special schools should support peer support initiatives among learners with paraplegia |

| Waiserberg et al (2024) | Israel | PT Policymakers health/education (10) | Qualitative descriptive study | IDIs | Inductive analysis | Policymakers question the provision of physiotherapy services in schools |

| Kandal et al (2025) | Norway | PT (13) | Qualitative descriptive study | FGs | Thematic analysis | Need to integrate interventions into the adolescents’ everyday lives |

| Themes | Subthemes | Unit of Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Clinical and school physiotherapy: separated by a fine line | 3.1.1 Lack of specific guidelines | Lack of guidelines, organising practice, differences between countries |

| 3.1.2 Professional competencies and diffuse responsibility | Ambiguity of competencies, lack of accountability | |

| 3.1.3 Lack of support: feeling like outsiders | Lack of managerial support, learning by doing, decision-making, lack of laterals and personnel | |

| 3.1.4 Professional intrusion | Professional intrusion, physiotherapy, and sports. | |

| 3.1.5 Pupil-centred, evidence based | Evidence-based physiotherapy, motor skills | |

| 3.2. Ensuring healthcare for children with specific conditions in schools | 3.2.1 Care for pupils with cerebral palsy | Aerobic exercise programme, cerebral palsy, motor and psychological benefits |

| 3.2.2 Supervising pupils using standing frames | Training needs, complications, burns | |

| 3.2.3 Implementing aquatic therapy programmes | Cerebral palsy, aquatic therapy, educational enhancements | |

| 3.2.4 Prevention and treatment of back problems/pain | Ergonomics, stretching, sedentary lifestyle, class backpack | |

| 3.2.5 Care and prevention of complications from spinal cord injuries | Movement, friction, ulcer prevention | |

| 3.2.6 Applying mind-body therapies | Mindfulness, breathing, body awareness, yoga | |

| 3.2.7 Addressing minor motor limitations | Developmental disorders, coordination, autism | |

| 3.3 The challenge of incorporating SP in educational settings | 3.3.1 Integrating therapy into curriculum | Change of status, professional recognition |

| 3.3.2 Meeting physiotherapy needs in special (and regular) education schools | Time, skills, funding, security, severity, doubts, financing | |

| 3.3.3 Training teachers and other professionals | Training teachers and assistants, learning from the physiotherapist | |

| 3.3.4 Integrating into multidisciplinary teams | Educational team, common goals, technology in the classroom | |

| 3.3.5 Accompanying, treating, and supervising in natural settings | School years, identifying problems | |

| 3.3.6 Overcoming setbacks and coping with difficulties | Time, staff, objectives, training, skills |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).