1. Introduction

Physiotherapy, as a health profession, created to care for people with health problems, must be a competent profession in humanized skills and aptitudes. Skills such as active listening, empathy, sensitivity, respect or tolerance should be valued at least as much as other skills associated with more technical and interventionist procedures, which usually focus on the patient's problem or symptom [

1]. It is important to remember the positive effects on health related to humanizing skills, that will bring about changes in favor of improving patients´ health through ethical strategies, care of the environment, verbal and non-verbal communication by professionals, care of the patient or teaching the patient about his pathology and its management, among other contextual factors [

2]. Thus, one of the main challenges in sustainable soft skills learning is integrating these skills into everyday work practices in a manner that promotes continuous improvement and resilience [

3]. However, the pursuit of efficiency and effectiveness in the healthcare system at the lowest possible cost, both financially and in terms of time, the pressure to provide care and the increase in administrative procedures make the humanized care or invisible care described by the nurses more difficult [

4,

5].

When the physiotherapy program was adapted to Higher Education, there were important changes in both the assessment system and the teaching-learning model. One of the main features of this adaptation was to emphasise the acquisition of competences, de-emphasising the traditional teaching model of knowledge accumulation [

6]. These competences have been defined as ‘the ability of health professionals to integrate and apply knowledge, skills and attitudes associated with the good practices of their profession in order to resolve the situations that arise [

7]. Based on this definition and taking into account not only integration but also application as action and knowledge, Tejada Fernández and Ruiz Bueno added in their definition of competences that it is not enough to have competences in the sense of resources, but that it is necessary to be competent, to master the action and to know how to use it well in the time and manner required by the situation [

7]. Therefore, educational reform has recently emphasized the need to integrate humanistic education into curricula in order to improve the professionalism of future healthcare professionals [

8,

9].

According to the World Confederation for Physical Therapy, practice education is essential for enabling students to apply their acquired knowledge, continue learning in a practical environment, and further enhance their competences [

10]. The subjects of the external clinical placements are those that allow physiotherapy students to put into practise all the competences described, both in theoretical and practical knowledge, in order to demonstrate their technical skills and act according to their values.

In Spain, Royal Decree (RD) 592/2014 regulates and guarantees the quality of student learning during external clinical placements and obliges universities to demonstrate the acquisition of student competences through assessment tools [

11]. This RD mentions some general competences of a more human nature, such as a sense of responsibility, creativity and initiative, personal commitment and motivation [

12]. It has been shown that they are of great importance for improving patients' health [

2]. These competences, described in such general terms, make it necessary to develop more specific assessment tools, especially for human competences, as there are many specific questionnaires for technical competences but not for human aspects.

At the academic level and taking advantage of the inertia of ‘humanistic empowerment’, projects such as the Invisible Care, Well-being, Security and Autonomy (CIBISA) scale, a tool for assessing nurses´ learning in patient care during clinical placements have emerged. Reflective practice is a pedagogical tool that helps students develop reflective learning habits. Thus, not only is technical care integrated, but the more humanistic dimensions are also taken into account through self-assessment [

13].

To the best of our knowledge, the CIBISA scale has not been validated for other healthcare professions such as physiotherapy. The objective of this study is to adapt and validate the CIBISA nursing scale to physiotherapy in a pilot study so that undergraduate physiotherapy students can self-assess their learning of visible care during their clinical placements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A prospective longitudinal study was designed to adapt and prevalidate the CIBISA scale from nursing to physiotherapy.

This study has been designed according to the “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) guidelines. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Universidad San Jorge (number 22/2/23-24). Informed consent was provided to all participants.

2.2. Procedure

The development of the modified CIBISA consisted of two phases: 1) adaptation and development of new items and 2) validation by establishing validity.

2.2.1. Phase 1. Adaptation and Development of New Items

This phase was conducted between September 2022 and March 2023.

The initial scale was developed from the “Invisible Care, Well-being, Safety and Autonomy” (CIBISA) scale. This scale was created to self-assess the learning of nursing students during their clinical placements. It consists of 28 items grouped into 3 dimensions (autonomy, clinical safety and well-being) in order to measure identifying aspects of the profession related to patient care and soft skills [

14].

Participants and data collection

A Delphi method was used in two rounds and a focus group was convened to achieve consensus on the adaptation of the CIBISA nursing scale to physiotherapy [

15]. The coordination team selected 14 national experts in physiotherapy, who had experience in the clinical placements of physiotherapy. The representation of different profiles was guaranteed, including clinicians, teachers, and researchers. Inclusion criteria were: (1) have more than 5 years of work experience and (2) have links to physiotherapy clinical placements, the academic field or research.

The experts received via e-mail the scale and conceptual framework to assess the relevance, pertinence, coherence, and clarity of each item. They were asked to rate the items of the CIBISA scale from the nursing area in order to adapt them to the physiotherapy area as follows: relevant, not relevant or relevantly modifiable. Any item that was considered relevant by more than 60% of the experts was taken as relevant. The experts should suggest alternatives if they think the item should be changed.

Once the new version of the scale for physiotherapy was available, a focus group of 14 experts was formed to analyze and develop a preliminary version. Each item of the CIBISA scale was discussed. Those items where the consensus was less than 60% were voted on and this preliminary version was reviewed by the coordinator team, who analysed the appropriateness of the items and ensured the comprehensibility of the scale.

In the second round, developed via email, the experts reassessed the structure and content of each item and created an agreement index with a cut-off point of 90%. Items below the cut-off point were adjusted or deleted by consensus. After the focus group and the second round, 30 items were obtained, with a total consensus among the entire panel of experts. CIBISA-F was the name proposed for the new scale adapted to physiotherapy.

2.2.2. Phase 2. Validation by Establishing Validity

This phase was conducted from February to May 2024.

Sample and participants

The study for the prevalidation of the

CIBISA-F scale was conducted at the Universidad San Jorge (USJ) in Zaragoza (Spain), with 25 physiotherapy students of the 3rd year [

16].

The inclusion criteria were: 1) volunteer students with Spanish nationality, 2) over 18 years old, 3) enrolled in clinical placements, 4) have never done external clinical placements, and 5) carrying out clinical placements in the Spanish territory.

Psychometric Assessment

For the psychometric validation of the

CIBISA-F scale, the Spanish version of the Health Professionals Communication Skills scale (assessment of communication skills in health professional) and the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale (assessment of social skills) were chosen [

17,

18,

19]. Both scales have items related to the same dimensions of the CIBISA-F

scale and were selected to assess correlations.

Reliability was assessed by internal consistency analysis with Cronbach's alpha statistic (acceptable if the value obtained exceeds 0.7) and by reproducibility analysis, assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (considered adequate if the value obtained exceeds 0.7) and with the Brand-Altman plot [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Construct validity was tested by correlation and regression analysis with the Health Professionals Communication Skills and the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scales.

Sensitivity to change was measured using Student's t-test for related samples. On one side, the results obtained at two different times before the clinical placements (CIBISA-F Pre_1 and CIBISA-F Pre_2) were compared. On the other side, the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale was used to compare and calculate the sensitivity to change of CIBISA-F by comparing the results obtained before and after the clinical placements.

The resulting questionnaire CIBISA-F, with 30 items and 4 possible answers for each item, proved to be feasible and easy for the students to complete, taking about 10 minutes to answer.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 28 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

The psychometric properties of the scale are described in the results section.

CIBISA-F Scale properties

The

CIBISA-F scale was designed for self-administration. The scale was developed to self-assess physiotherapy students´ soft skills learning during their clinical placements. The scale consists of 30 items. Each item presents an action to be carried out based on soft skills. The actions are related to the treatment of the patient. Students should indicate how often they perform these actions

. The response format follows Likert-type with 4 possible answers: 1: Almost never or never; 2: Sometimes; 3.- Frequently; 4.- Almost always or always [

14]. The overall value of the scale is estimated by calculating the average value of the answered items (range 1-4). The range of possible scores goes from 30 to 120 points. The highest scores represent a higher level of care learning.

The Goldstein Social Skills Assessment Scale

The

Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale can be self-administered. Its purpose is to find out how a person behaves in different situations, and what kind of behaviour they develop to deal with these situations. The scale was translated and adapted into Spanish by Ambrosio Tomás between 1994 and 95 [

19]. It consists of 50 items in the form of a list of basic skills which can be more or less pronounced. These skills are in turn grouped into 6 dimensions: Basic Social Skills, Advanced Social Skills, Feeling Skills, Alternative to Aggression Skills, Coping with Stress Skills and Planning Skills. The response format is a Likert-type with 5 possible answers: 1: Never; 2: Very seldom; 3.- Sometimes; 4.- Often; 5.- Always. The interpretation of the results provides information about the level of the person's social skills. Lower scores indicate a poor level and progressively increase to low, normal, good, and finally excellent levels of ability.

The Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (EHC-PS)

The

Health Professionals Communication Skills scale (EHC-PS) is a self-administered scale whose purpose is to assess the dimensions of empathy, informative communication, respect and social skills, related to communication skills and assertivity in health professionals. It is carried out on the basis of 18 items that quantify the agreement or frequency of the professional´s actions in various situations that arise. The response format is a Likert-type with 6 possible answers: 1: Almost never; 2: Occasionally; 3.- Sometimes; 4.- Usually; 5.- Often; 6.- Very often. Two of the items are reverse-worded (items 16 and 18). The reverse wording is scored: 1: Very often; 2.- Often; 3.- Usually; 4.- Sometimes; 5.- Occasionally; 6.- Almost never. Each dimension has a continuous score. Higher scores indicate greater manifestation of the assessed behavior [

17]

Data collection

Data was collected in digital format via the Microsoft Forms 365 platform.

The first questionnaire (Pre_1) was sent out 15 days before the start of clinical placements. It consisted of four parts: 1.-General questions related to age, assigned practice center and specialty of the practice center; 2.-CIBISA-F scale; 3.-Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale and 4.-Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale. For each of the scales, they were informed about the procedure for answering questions correctly.

The second questionnaire (Pre_2) was sent out 2-3 days before the start of clinical placements. It consisted of three parts: 1.-CIBISA-F scale; 2.-Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale and 3.-Health Professionals Communication Skills scale.

The third questionnaire (Post), consisting of the three scales, was finally sent to them after 6 weeks of clinical placements.

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1. Adaptation and Development of New Items

3.1.1. Participants’ Characteristics

The coordination team selected 14 national experts, 42.86% (n=6) were clinical profiles, 21.43% (n=3) were university teachers and the remaining 35.71% (n=5) were mixed.

3.1.2. Adaptation and Development of New Items

After the first round of review of the 28 items of the CIBISA nursing scale by the experts, 20 items were considered relevant for physiotherapy (71.43%). 6 items were identified as relevant and modifiable (21.43%), those with proposals for modification and which were not voted as relevant by more than 60% of the experts. Items 6 “I have visited the patient without waiting for him/her to call me” and 17 “I have given injections, handled parenteral equipment, aspirators and other equipment in the service” (7.14%) were considered not relevant because they were very specific to the nursing area without the possibility of modification.

During the focus group, all proposed modifications from the first round were considered. As a result, 12 of the 26 items were adopted unchanged from the original CIBISA scale (46.15%) and the remaining 14 were retained with some changes (53.85%).

In the second round the approval rate was 100 for 18 points, 92.86% for 7 points, and 85.71% for 1 point.

The experts and the coordination team considered that items 1, 4, 12 and 19 should be divided into 2 as they describe several actions and make it difficult to answer them.

After the focus group and the second round, 30 items were finally obtained, and there was total consensus among all the experts.

3.2. Phase 2. Validation by Establishing Validity

During this period, all students answered all questionnaires correctly. There were no dropouts, and no questionnaires were cancelled due to response errors.

3.2.1. Participants’ Characteristics

A total sample of 25 participants completed the survey (response rate=100%). The proportion of women was 36% (n=9) and the proportion of men was 64% (n=16). All were third-year physiotherapy students at the University of San Jorge. The average age was 23.04 years (SD=3.1) and ranged from 20 to 30 years.

The services in which they carried out their clinical placements were pediatrics 16% (n=4), musculoskeletal 28% (n=7), cardiorespiratory physiotherapy 8% (n=2), geriatrics 8% (n=2), urogynecology 4% (n=1), neurology 12% (n=3), general physiotherapy 24% (n=6).

3.2.2. Reliability

Internal Consistency

The internal consistency measured with Cronbach´s α showed the results α=0.911.

Reproducibility

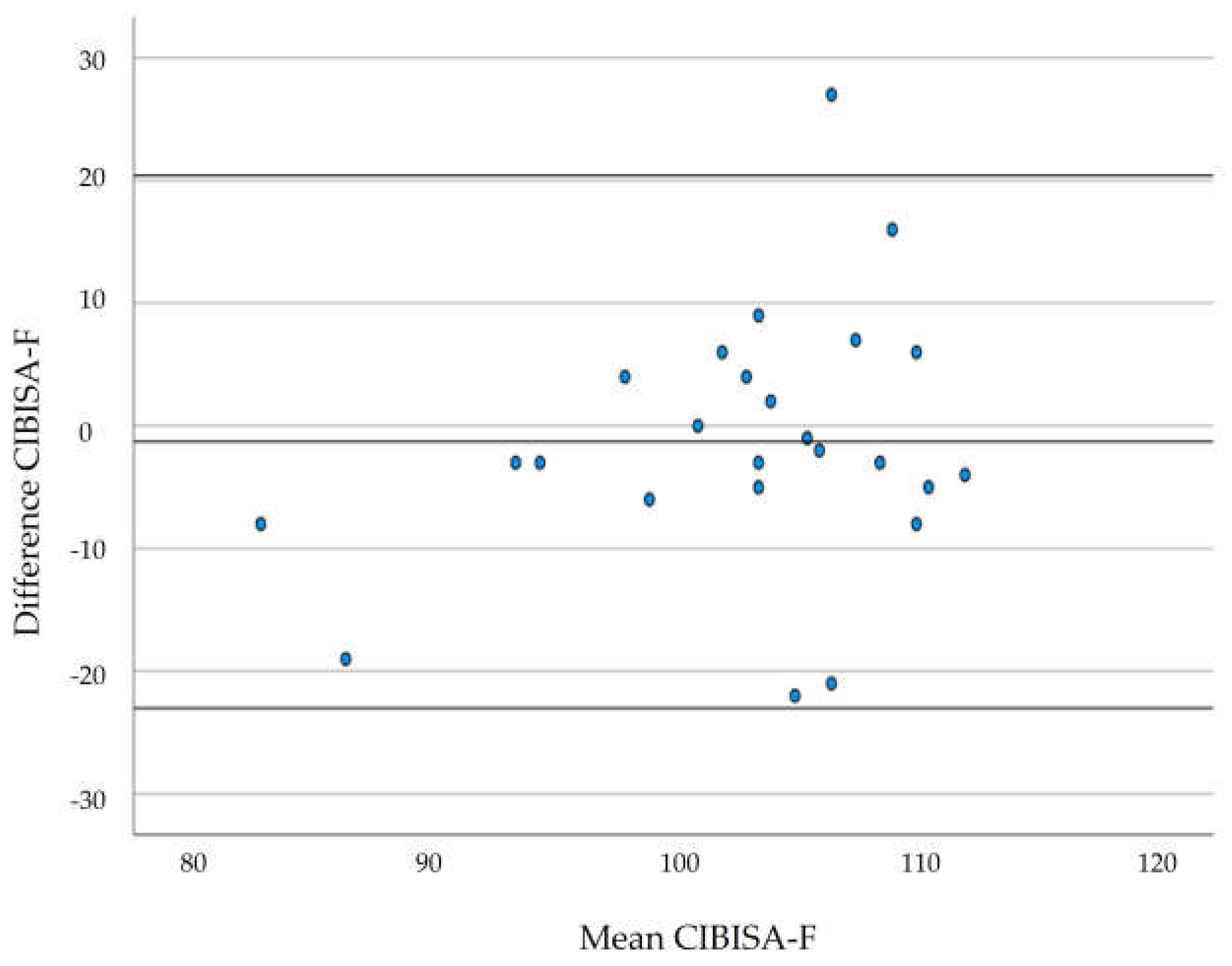

The ICC between Pre_1 and Pre_2 showed a value of 0,451. The Brand-Altman plot only left a measure out of the limits (

Figure 1).

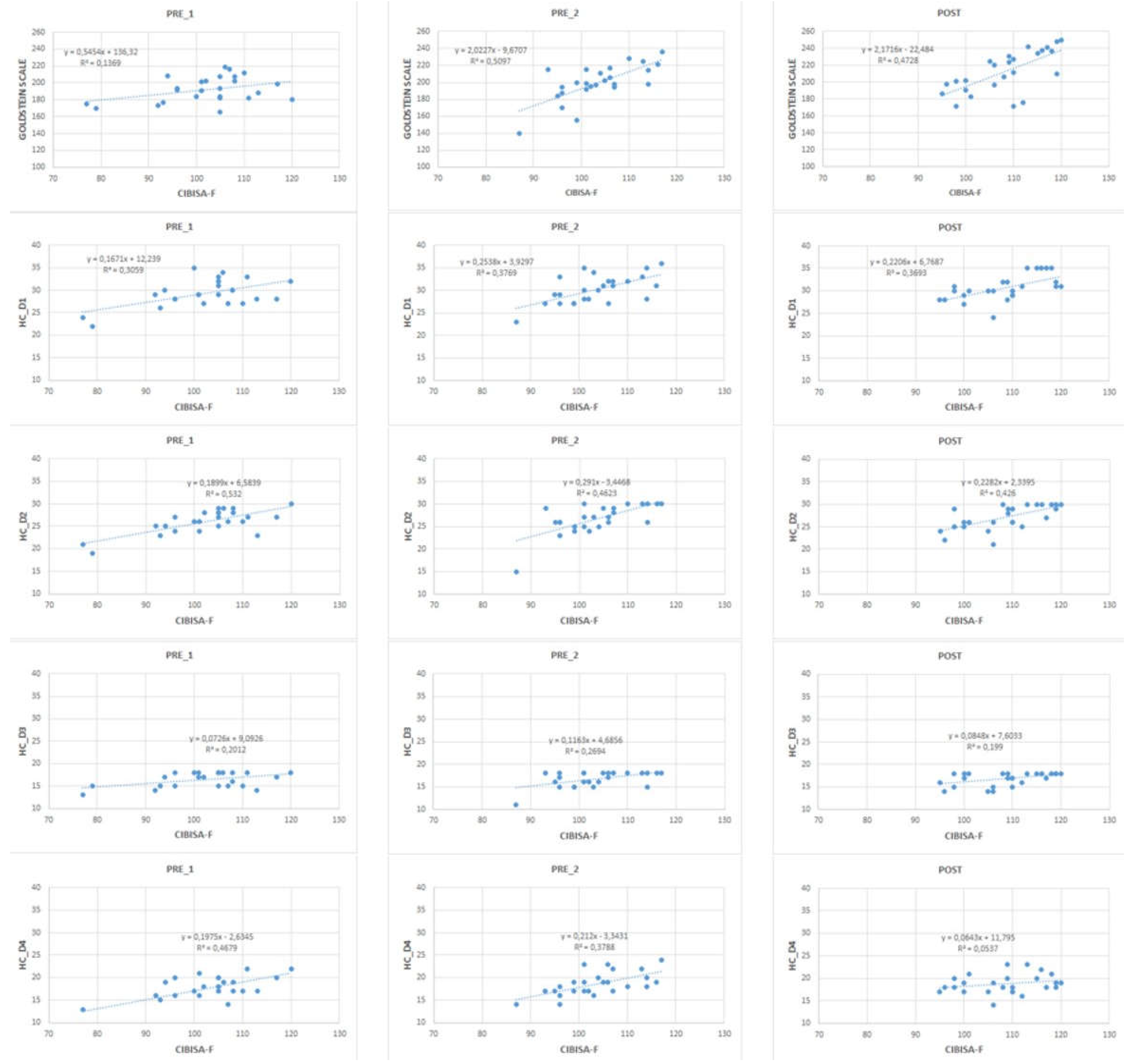

3.2.3. Construct Validity

Construct validity was measured with the Pearson's correlation coefficient and regression study of CIBISA-F with the other questionnaires. This procedure was performed for the overall score of CIBISA-F with the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment and the Health Professionals Communication Skills scales domains.

The correlation values of the scale CIBISA-F with the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale and with the domains of the Health Professionals Communication Skills scale, at three different points in time (Pre_1, Pre_2, and Post assessment), are shown in

Table 2.

The results of the regression analysis between the questionnaires, with the result of the CIBISA-F scale as the dependent variable, are shown in

Figure 2 /

Table 3.

3.2.4. Sensitivity to Change

To analyze the sensitivity to change, a mean comparison was performed by comparing the results obtained in

CIBISA-F Pre_1 and

CIBISA-F Pre_2. The analysis revealed no significant differences between the two different time points (p=0.555) (

Table 4).

The Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale was used to compare and calculate the sensitivity to change of CIBISA-F scale, showing that both questionnaires present variation and that CIBISA-F scale has the same sensitivity to change as the Goldstein questionnaire (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

One of the challenges facing physiotherapy nowadays is to be able to offer quality and sustainable education based on values and learning soft skills that go beyond the more technical skills. It is crucial to recognize the positive health impacts associated with humanizing skills. These skills can lead to improvements in patients' health through ethical strategies, environmental care, and verbal and nonverbal communication by professionals. In addition, patient care and education about their conditions and management of their disease, among other contextual factors, are important. In the field of nursing and from the educational point of view, we found references of a work in this line, with students in clinical placements [

13,

14,

24].

In this study, the CIBISA-F scale of 30-items, which measures the learning of invisible care in physiotherapy, was adapted and validated. To our knowledge, this is the first known study conducted to obtain a scale to assess humanized healthcare in physiotherapy students in placements and to measure its psychometric properties. The results demonstrated high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, construct validity, and sensitivity to change.

All respondents answered the questionnaires three times, and no questionnaires with blank items were found. In addition, as in the validation study of the CIBISA Nursing scale, all students completed the questionnaire in less than 10 minutes.

Internal consistency

The internal consistency measured with Cronbach´s α showed a value of α=0.911 for the CIBISA scale adapted to physical therapy, indicating excellent reliability [

20,

21,

25]. According to the recommendations of George and Mallery (2003, p.231) [

26], it is considered an excellent coefficient and therefore a highly reliable questionnaire. Values above the CIBISA scale for nursing were obtained, with α=0.888 [

14]. These results may be due to the decision to subdivide 4 of the items (1, 4, 12 and 19) as they originally described multiple actions and made these items more difficult to answer. This could make the response to these items more accurate.

The questionnaires used to compare the CIBISA-F results included the

Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale with an internal consistency of α=0.924

and the Health Professionals Communication Skills scale, whose internal consistency is divided into domains: 0.77 for Empathy, 0.78 for Informative Communication, 0.74 for Respect, and 0.65 for Social Skill. A Cronbach's alpha of 0.5-0.6, obtained by comparing the sum of the responses to the CIBISA-F questionnaires given at three different points in time with the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale, indicates reproducibility. Furthermore, similar data were observed in the validation of the Humanization of Healthcare Scale (HUMANS) for nursing professionals, where, after comparing the various dimensions of humanized healthcare with three other scales, it was found that virtually all dimensions were positively correlated [

27].

Reproducibility

The ICC value achieved in this pilot study after administering the questionnaire to the same population on two different occasions before the clinical placements is considered enough [

21,

23].

Compared to similar studies such as in the study on the psychometric properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale, in which the test-retest carried out for the four domains that compose it showed a high ICC value and its lowest value was 0.79 [

28], or in the study on the Perception of Invisible Nursing Care-Hospitalization questionnaire, in which we also observed an ICC value between 0.71 and 0.9, showing good reliability [

29], it may seems that our CCI results are low, but, we consider that this result is because there are few differences between the two-time points, as shown by the fact that the mean difference for values above 100 is 1.28. As the values change only slightly, it is unlikely that the results will show higher values, as this is a comparison of the variability between the students and the total number in a pilot study with a small sample of participants.

Both the Brand-Altman plot, in which all but one of the values lies within the expected range, and the Student's t-test for related samples show that the CIBISA-F scale is reliable in the repetition of the assessment in people with no change in their condition [

21,

23].

Construct Validity

Construct validity of the CIBISA-F scale was tested by correlation and regression analysis using the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale and the domains of the Health Professionals Communication Skills scale in 3 different moments. The high values of the correlation coefficient and the appropriate fit of regression models indicate adequate validity. Only 2 of the 15 measurements come out non-significant in 25 cases. The fact that the data for the remaining 13 measurements are significant suggests that this may be due to the small sample size. These results are similar to those of other measures of invisible care, such as the Perception of Invisible Nursing Care-Hospitalisation questionnaire, which found a moderate to strong relationship with the Spanish validated version of the Newcastle Satisfaction with Nursing Scales (NSNS) [

29].

The correlation with the Goldstein Social Skills Assessment shows high values just before starting the clinical placements and after, in both moments (p<0.001). Nevertheless, at Pre_1, where the measurement was not significant (p= 0.069), it can be assumed that this could be due to the small sample size. The Health Professionals Communication Skills scale has been verified with each one of its domains, showing significant results in all domains during both pre-clinical placement measurements (p<0.05). However, in the Post assessment, the results of the Assertivity domain were not significant (p=0.265). The CIBISA Nursing scale corresponds to the three domains of the triangle of care developed by Concepción German: autonomy, clinical safety, and well-being [

30]. In the validation study, the domains were analyzed individually, concluding that there are no items that correspond exclusively to one of the three dimensions originally proposed.

As the CIBISA-F scale is not presented as a scale with domains, we believe that a larger sample is required to correlate the overall calculation of the items that make it up with the individual domains of the Healthcare Professional Communication Skills Scale in order to conduct a more comprehensive analysis.

Sensitivity to change

Sensitivity to change is the measure taken to assess the ability of an instrument to detect a change in the results obtained after repeated applications, at different times, of the same instrument [

31,

32].

After reviewing the bibliography in search of articles on the validation of scales similar to the study presented here, we have not found any articles that take this aspect into account, or if there are any, the diversity of methodology used is very diverse and therefore difficult to compare [

14,

24,

29,

32].

The Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale and the CIBISA-F scale were compared twice before the students started their clinical placements. There were no significant differences (p>0.05), indicating that both scales showed no changes in students prior to their clinical placements. This suggests that the CIBISA-F scale is consistent and stable in the assessment of humanized skills, as it showed no variations in the students' results in the two measurements performed [

31,

32].

In addition, there were statistically significant changes (p<0.05) when comparing the Goldstein Social Skills scale and the CIBISA-F scale answered before and after the clinical placements. In this case, students increased their scores on both questionnaires, suggesting that the basic characteristics of assessment tools for measuring longitudinal change over time are represented [

31,

32]

Limitations

The present study has a small sample size. In a future study, the sample size should be increased taking into account the preliminary results of the prevalidation of the CIBISA-F scale.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that the version of the CIBISA-F scale is a useful and reliable tool for measuring humanization skills in healthcare in physiotherapy students' during their clinical placements.

The availability of this scale makes it possible to objectify the progress of learning in care beyond purely technical procedures, it allows to measure how students' learning and competence levels increase, and it could allow comparison between students to detect specific learning needs.

New investigations will be conducted to test and refine this instrument’s robustness and psychometric qualities. Future analyses will involve different groups and contexts of education and health, evaluating the scale’s reliability, sensitivity, and validity.

The humanistic perspective that the CIBISA-F scale gives to the measurement of learning makes it possible and sustainable to overcome the challenge that students, when self-assessing themselves, give importance to soft skills related to patient care that would otherwise be invisible and unappreciable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rita Galán-Díaz, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez, Beatriz Alonso-Cortés Fradejas and Inmaculada Villa-del Pino; Data curation, Rita Galán-Díaz, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez and Manuel Gómez-Barrera; Formal analysis, Rita Galán-Díaz and Manuel Gómez-Barrera; Funding acquisition, Rita Galán-Díaz and Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez; Investigation, Rita Galán-Díaz, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez, Beatriz Alonso-Cortés Fradejas and Inmaculada Villa-del Pino; Methodology, Rita Galán-Díaz, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez and Inmaculada Villa-del Pino; Project administration, Rita Galán-Díaz, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez and Manuel Gómez-Barrera; Resources, Rita Galán-Díaz and Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez; Software, Rita Galán-Díaz and Manuel Gómez-Barrera; Supervision, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez and Manuel Gómez-Barrera; Validation, Rita Galán-Díaz and Manuel Gómez-Barrera; Writing – original draft, Rita Galán-Díaz and Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez; Writing – review & editing, Rita Galán-Díaz, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez, Raquel Lafuente-Ureta, Natalia Brandín-de la Cruz and Jose Manuel Burgos-Bragado. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Cátedra de Humanización de la Asistencia Sanitaria de la Universidad Internacional de Valencia, Fundación ASISA y Proyecto HU-CI and by the Gobierno de Aragón (Number grant: B61_23D).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Universidad San Jorge (protocol code No. 22/2/23-24. Date. 23 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be provided upon a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants and collaborators for their significant contributions to this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CIBISA |

Invisible Care, Well-being, Security and Autonomy nursing Scale |

| CIBISA-F |

Invisible Care, Well-being, Security and Autonomy Scale adapted to physiotherapy |

| RD |

Royal Decree |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| ICC |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| EHC-PS |

Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale |

| Pre_1 |

15 days before clinical placements |

| Pre_2 |

2-3 days before clinical placements |

| Post |

after clinical placements |

| D1-CI |

Domain 1- informative communication |

| D2-E |

Domain 2- Empathy |

| D3-R |

Domain 3- Respect and social skills |

| D4-A |

Domain 4- Assertivity |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| NSNS |

Newcastle Satisfaction with Nursing Scales |

References

- Martin Urrialde, J.A. Fisioterapia y Humanización: No Es Una Moda Sino Una Necesidad. Fisioterapia 2021, 43, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, M.; Rossettini, G. Enhance Placebo, Avoid Nocebo: How Contextual Factors Affect Physiotherapy Outcomes. Man. Ther. 2016, 24, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, M.J.; Serpa, S. Higher Education as a Promoter of Soft Skills in a Sustainable Society 5.0. J. Curric. Teach. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés Muro, M.P.; Ayala Calvo, J.C.; Manzano García, G. Burnout in Nursing: A Vision of Gender and “Invisible” Unrecorded Care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 2148–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Fernández, R. La Humanización de (En) La Atención Primaria. Rev. Clínica Med. Fam. 2017, 10, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo, Jesús et al. Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de La Calidad y Acreditación (ANECA) Libro Blanco: Título de Grado En Fisioterapia, 2004.

- Fernández, J.T.; Bueno, C.R. Evaluación De Competencias Profesionales En Educación Superior: Retos E Implicaciones. Educ. XX1 2016, 19, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shan, J.; Zeng, L. Exploration and Practice of Humanistic Education for Medical Students Based on Volunteerism. Med. Educ. Online 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutac, J.; Osipov, R.; Childress, A. Innovation Through Tradition: Rediscovering the “Humanist” in the Medical Humanities. J. Med. Humanit. 2016, 37, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Physiotherapy. Physiotherapist Education Framework; World Physiotherapy.: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Real Decreto 592/2014, de 11 de Julio, Por El Que Se Regulan Las Prácticas Académicas Externas de Los Estudiantes Universitarios, /: Vol. BOE-A-2014-8138, pp 60502–60511. https, 2014.

- Martiáñez Ramírez, N.L.; Rubio Alonso, M. Propuesta de memoria del estudiante de las prácticas clínicas externas en el Grado en Fisioterapia según Real Decreto 592/2014; Universidad Europea de Madrid, 2015.

- Navas-Ferrer, Carlos. Escala CIBISA y eventos notables: instrumentos de autoevaluación para el aprendizaje de cuidados. 2018.

- Urcola-Pardo, F.; Ruiz de Viñaspre, R.; Orkaizagirre-Gomara, A.; Jiménez-Navascués, L.; Anguas-Gracia, A.; Germán-Bes, C. La Escala CIBISA: Herramienta Para La Autoevaluación Del Aprendizaje Práctico de Estudiantes de Enfermería. Index Enferm. 2017, 26, 226–230. [Google Scholar]

- Varela-Ruiz, M.; Díaz-Bravo, L.; García-Durán, R. Descripción y usos del método Delphi en investigaciones del área de la salud. Investig. En Educ. Médica 2012, 1, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- García-García, J.A.; Reding-Bernal, A.; López-Alvarenga, J.C. Cálculo del tamaño de la muestra en investigación en educación médica. Investig. En Educ. Médica 2013, 2, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado-González, S.; van-der Hofstadt Román, C.J.; Rodríguez-Marín, J. Creación de La Escala Sobre Habilidades de Comunicación En Profesionales de La Salud, EHC-PS. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá-Sanchis, R.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Leal-Costa, C.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Escribano, S. Psychometric Properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale in University Students of Health Sciences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldtein, Arnold, A.T.; Ambrosio, Tomas et al.; et al. Escala de Evaluación de Habilidades Sociales, 1995.

- Oviedo, H.C.; Campo-Arias, A. Aproximación al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2005, 34, 572–580. [Google Scholar]

- García de Yébenes Prous, M.J.; Rodríguez Salvanés, F.; Carmona Ortells, L. Validación de cuestionarios. Reumatol. Clínica 2009, 5, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, R.M. Book Review : Psychometric Theory (3rd Ed.) by Jum Nunnally and Ira Bernstein New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994, Xxiv + 752 Pp. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 19, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pérez, J.A.; Pérez Martin, P.S. Coeficiente de correlación intraclase. Med. Fam. SEMERGEN 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán González-Serna, J.M.; Ferreras-Mencia, S.; Arribas-Marín, J.M. Development and Validation of the Hospitality Axiological Scale for Humanization of Nursing Care. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 2017, 25, e2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, R.M. Book Review : Psychometric Theory (3rd Ed.) by Jum Nunnally and Ira Bernstein New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994, Xxiv + 752 Pp. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 19, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update, ()., 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon.: Boston, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M. del C.; Herera-Peco, I.; Molero Jurado, M. del M.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. The Development and Validation of the Healthcare Professional Humanization Scale (HUMAS) for Nursing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado-González, S.; Rodríguez-Marín, J.; vander-Hofstadt-Román, C.J. Psychometric Properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (HP-CSS). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huércanos-Esparza, I.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Orkaizagirre-Gómara, A.; Ramón-Arbués, E.; Germán-Bes, C.; Jiménez-Navascués, L. Measuring Invisible Nursing Interventions: Development and Validation of Perception of Invisible Nursing Care-Hospitalisation Questionnaire (PINC–H) in Cancer Patients. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 50, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Investigacion en enfermeria imagen y desarrollo. https://www.index-f.com/para/n9/pi009.php (accessed 2025-02-16).

- Stratford, P.W.; Riddle, D.L. Assessing Sensitivity to Change: Choosing the Appropriate Change Coefficient. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2005, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Yébenes Prous, M.J.G.; Rodríguez Salvanés, F.; Carmona Ortells, L. Sensibilidad al Cambio de Las Medidas de Desenlace. Reumatol. Clínica 2008, 4, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).