Introduction

White Paper 6 (EWP6), titled "Special Needs Education-Building an Inclusive Education and Training System," was established to address past discriminatory practices which resulted in less than 20% of children with disabilities accessing education [

1,

2]. The constitution for the Republic of South Africa 1996 recognizes access to education as a basic human right for all. Therefore, the endorsement of the EDWP6 by the Department of Basic Education seeks to establish equity, access to quality education, and support for learners, parents, and communities in overcoming barriers to learning [

1]. According to the National Development Plan 2030, access to quality education for children with disabilities will mobilise South Africa to achieve its employment equity goals [

3].

Teachers used the deficit model and their intuition to identify learners having challenges with learning materials [

4]. Learners were admitted to schools based on having passed their aptitude tests. This system stigmatised learners who did not pass their aptitude tests instead of considering the innate learning style of the learner [

4]. To facilitate educational reform, the policy to Screen Identify Assess and Support learners with learning barriers got implemented in 2014 after it was piloted at different schools in 2008 [

5]. The policy dispenses guidelines on how learners with barriers to learning can be supported in order to prevent learners from dropping out of school due to a lack of inclusion [

6].

According to the level of support assigned to categories of schools, special schools offer extensive support and resources, including specialised facilities, daily access to therapists (depending on availability), and individualised curricula [

7,

8]. Full-service schools offer moderate support, fostering an inclusive environment for disabled and non-disabled learners. In contrast, mainstream schools provide minimal support, primarily through remedial classes, to address various learning needs. However, provision of support services rendered by therapists including physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists is reported to be a challenge in developing countries due to shortage of these therapists [

9]. This is notably evident in rural provinces of South Africa [

2,

10,

11,

12].

Physiotherapists working within educational settings play a crucial role in the early detection of learning barriers attributable to motor skills [

13]. Gross motor skills have been found to significantly bolster visual-motor integration, which contributes positively to a child’s readiness for school [

14]. Through collaborative efforts with other stakeholders at the school, physiotherapists contribute to setting rehabilitation and education goals to develop support plans that are customised for every learner [

15]. The role of physiotherapists is not as prescribed as compared to that of educators in the SIAS policy document and again, their contribution towards implementing the policy is depended on their availability at schools [

6]. Nevertheless, physiotherapists working in the education sector are implicated in advancing inclusive education through knowledge transfer of their expertise in conducting functional assessments of activity limitations and participation restrictions within the context of the learner.

This study is conceptualised within the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model. The ICF model assumes that the learner’s level of function or disability results from the interplay between the learner's characteristics and the environment. In addition, it guides the criteria for providing support by considering the level of function and activity participation in learning processes in class and around the school [

16].

The SIAS process of assessment ensures consistent procedures in assessing and providing support by utilising toolkits such as Learner Profiles, Special Needs Assessment 1 (SNA1), Special Needs Assessment 2 (SNA2), Special Needs Assessment 3 (SNA3) and Individual Support Plans (ISPs) [

6]. These assessments focus on identifying barriers to learning, level of function, and participation rather than academic achievement. The Learner Profile is used by the class educator to screen and identify all learners that have learning barriers of any kind be it in social, physical or academic domains. Additional documents such as Road to Health booklet, Integrated School Health Programme reports, school reports (from previous schools), reports from therapists and parents would assist the educator in identifying learners at risk of not benefiting from academic activities. The educator is expected to take the role of a case manager and utilise the SNA1 to facilitate the provision of support by collaborating with the parent, and the learner (above 12 years). The educator should approach the School-Based Support Team (SBST) when the planned support is not benefitting the learner. The SBST utilising the SNA2 would review the support provided by the educator and make recommendations to support the educator and the learner. Where available therapists based at schools including physiotherapists would form part of the SBST to develop individualised support plans for the identified at risk learners. It is crucial for the ISP to be monitored and evaluated for progress by the class educator and therapists in order to make necessary adjustments to the intervention or to make a referral to the District-Based Support Team. This team comprises of inclusive education specialists and therapists based at the district level. Despite the DBST being the apex of school support, it is often challenging to access [

17,

18].

Therefore, based on the SIAS process of assessment, the role of the physiotherapist is implied at the school level and the district level. This process with the involvement of physiotherapists may lead to the referral of some learners to either full-service or mainstream schools, ultimately contributing to a decrease in the waiting list for learners currently unable to access education. However, there are challenges with fostering collaborations between educators and therapists at schools as some educators prefer working independently rather than in multidisciplinary teams [

19].

The SIAS policy is closely linked with the Rationalisation and Redeployment (R&R) policy. The primary objective of the R&R policy is to establish equity in the allocation of educator positions in the post-apartheid era, as outlined in the White Paper on Education and Training (1995). This policy stipulates that educators who are in surplus to requirements at one school should be redeployed to other schools experiencing a shortage based on the learner-to-educator ratio. This ratio is 40:1 for primary and 35:1 for high schools [

20]. As more learners are transferred to other schools without the admission of new learners, it becomes increasingly likely that some educators will need to be redeployed. However, the R&R policy is often misinterpreted at the school level, being perceived as a punitive measure rather than a strategic approach to addressing human resource challenges [

21].

Materials and Methods

The researcher explored education physiotherapist’s knowledge, and the challenges experienced in implementing the SIAS policy at special schools in Limpopo province.

Study Design

The study employed a qualitative, single exploratory case study design using focus group discussions. A case study methodology was chosen to attain a better and deeper understanding [

22] of the physiotherapists’ knowledge and challenges regarding SIAS policy implementation within Limpopo Province of South Africa.

Population and Sampling

The study was conducted in one of the rural provinces of South Africa being Limpopo Province. Limpopo Province is the fifth largest province out of nine provinces in South Africa in terms of population size [

23]. The population is predominantly Black African (96.7%), and highly varied in terms of languages spoken. The majority speaks Sepedi (52.9%), followed by Xitsonga (17%) and Tshivenda (16.7%) [

24]. As the result of the province being rural, there are constraints pertaining to resource allocation. For instance, the number of public special schools and healthcare facilities differs significantly from those in Gauteng Province which is urban. Limpopo Province only has 35 special schools accommodating learners with intellectual and physical disabilities including visual and hearing impairments whereas there are 120 special schools in Gauteng Province [

25]. Of the 35 special schools, only three are designated for learners with physical disabilities and with only one admitting learners from Grade R to Grade 12.

During the study period, the Limpopo Department of Education employed eight education physiotherapists, including the researcher. As a result, a sample of seven education physiotherapists (n=7) working for the Limpopo Department of Education was purposefully sampled [

26] to participate in the study. Of the seven, only one physiotherapist was based at a special school. In contrast, the six were appointed on an itinerant basis, rendering services to various education districts. Physiotherapists in the education sector registered with the HPCSA and who gave written informed consent to participate in the study voluntarily were included.

Recruitment

Following the ethical approval from the provincial Department of Education, prospective participants were emailed individually detailed information letters and informed consent forms inviting them to participate in the focus group discussion for the study. The recruitment process started on the 19th April 2021 to the 6th May 2021.Subsequently, after reminders all education physiotherapists expressed their interest and provided written informed consent forms via emails.

Data Collection

Considering the geographical dispersion of participants, a virtual session was adopted to facilitate convenient engagement [

27]. Data collection followed a respondent-moderated synchronous virtual format for FGD conducted via Microsoft Teams® platform [

28]. This approach involved participants choosing a moderator to lead the discussions whilst the researcher (MMS) was a moderator’s assistant during the discussion. This approach is thought to increase wide-ranging responses that are truthful from participants [

29,

30]. The moderator was taken through literature that provided guidance and tips on how to conduct FGDs. These included being able to listen to participants, being able to probe during discussions, being able to contain the discussions [

31]. The interview guide [

32] was shared with participants to famaliarise themselves with the questions in preparation for responses and also for participants to make changes with the questions where necessary. There was no indication from the participants that questions needed to be added or changed. Participants were asked about their knowledge and challenges experienced in implementing the SIAS Policy. Questions elicited insights into the challenges encountered while implementing SIAS Policy. To ensure confidentiality, each participant opted for a pseudonym to safeguard their identity [

33]. Participants chose these names:

Montsho, Celine, Sbakuza, Funky, R.S., Valentine, and Milkshake. Before FGD, all participants agreed upon the rules governing FGD. FGD was conducted in English, audio recorded and lasted for 90 minutes over four sessions

Data Analysis

Content analysis with ATLAS.ti v9 was used to determine the knowledge of education physiotherapists with the SIAS policy. Audio records were transcribed verbatim and uploaded onto ATLAS.ti v9 for analysis by the researcher. Transcripts (n=4) were analysed in retrospect and started with the strongest transcripts [

34]. The majority of the new codes, 26 (69%) in the first transcript were already generated by the second interview, 36 (95%) by the third interview and 38 (100%) were generated by the fourth interview. Data were coded following an inductive thematic analysis process [

35] by authors MMS and MT, with DM serving as a referee and a decision-maker in cases of a disagreement. Using a co-coder and a referee was aimed at maintaining coding consistency and validating the accuracy of the coding process, following the guidelines set forth by [

36]. A consensus agreement was used as a strategy to determine intercoder reliability [

37]. This strategy allowed back- and-forth and in-depth discussions of themes among the authors yielding credible results. Reaching consensus through discussions helped in addressing nuances that statistical measures might have missed [

38].

Trustworthiness

Strategies such as credibility, reflexivity, dependability, confirmability, and transferability ensured study rigour [

39].

Credibility was upheld through member checks where participants received transcripts to validate their accuracy [

40]. In demonstrating reflexivity, the researcher has a good understanding of the sector, having worked for four years within the Inclusive Education sub-directorate of the provincial Department of Education and thus able to interpret participant responses accurately within the context. This role entailed collaborative efforts with physiotherapists across various education districts, collectively working toward enhancing inclusive education. The researcher was integral in educating educators from both special and full-service schools and training caregivers and Special Care Centers’ managers on inclusive education policies, with a particular focus on SIAS policy.

To ensure transferability, descriptions of the province name, the district names, participants’ demographics, data collection procedures, and duration were provided [

39]. The findings are dependable should the same interview guide, participants and similar context be used for another study. Lastly, confirmability was upheld through collaborative efforts with a co-coder, ensuring consensus and resolving any coding discrepancies that arose during the process [

41].

Ethical Consideration

Approval to conduct the study was granted by both the University Health Sciences Ethics Committee and the provincial Department of Education to ensure ethical considerations were met. The university assigned the research the study identity. The research adhered to the ethical principles of conducting studies involving human participants, following the guidelines in the Helsinki Declaration 2013 version [

42].

Results

At the time of the study, all physiotherapists employed by the provincial department of education took part in the study. The demographic characteristics of participants is presented in

Table 1.

Themes related to the challenges experienced with the implementation of the SIAS policy are presented in

Table 2.

Discussions

A study by [

43] highlighted distinct demographic differences among registered physiotherapists in South Africa. Their investigation revealed the majority to be white physiotherapists (55.6%) and a notable female majority (82.9%). The median age ranged from 27 to 37 years. This comparison showed that our study's participants pertaining to age were older due to the majority having more than ten years of working experience.

Sub-Theme 1: Lack of In-Service Training and SIAS Policy Implementation

The training model, known as the cascade model, entails training a select group of individuals who are then expected to train others who were not present during the original training. While this model can be cost-effective, it can also be ineffective [

44] as it may not adequately address the needs of all employees, leading to negative attitudes towards policy implementation [

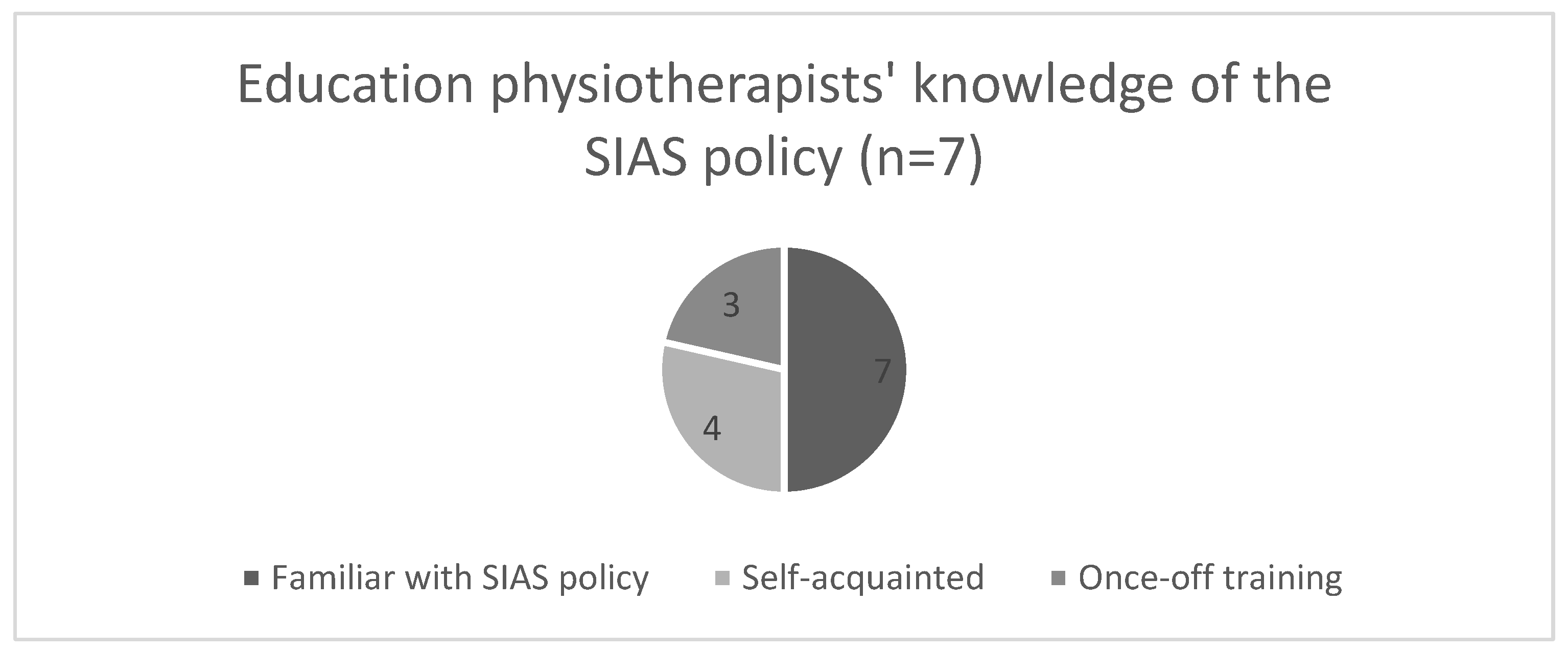

45]. The training for education physiotherapists occurred over two days and was not repeated for other staff members appointed at a later stage. Similarly, training for educators targeted only School- Based Support Teams and it was a one-time event. Due to the lack of ongoing training and capacity development by the provincial department of education, education physiotherapists took the initiative to self-acquaint themselves with the SIAS policy (

Figure 1). This initiative demonstrates that physiotherapists applied their graduate attributes to being lifelong learners. Although physiotherapists could adapt without formal training, their understanding and application of the policy could be inconsistent. Inconsistency will not achieve the uniformity and standardisation the SIAS assessment process intends to achieve.

For educators, this lack of knowledge and understanding failed to initiate the initial use of Learner Profiles to screen learners, a crucial step in the SIAS assessment process. One of the underlying issues contributing to the knowledge challenges faced by education physiotherapists and educators is the lack of inclusive education in the undergraduate teaching curriculum [

46] especially for professionals who qualified prior to the launch of the SIAS policy in the year 2014. Many school educators who received their qualifications before 2014 (when the SIAS policy was launched) were not exposed to inclusive education principles and practices during their initial training [

46]. Addressing these training gaps and incorporating inclusive education in the initial training curriculum could be essential steps towards improving the situation [

47]. Training and professional development initiatives can be introduced to enhance educators' comprehension of physiotherapists' roles and expertise, encouraging a collaborative approach to support learners with special needs [

19,

48]. Education physiotherapists should also attempt to expand their knowledge base as part of their continuous professional development. There is a need for accredited short-learning courses to train therapists (physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists) in the education sector on the SIAS policy.

Sub-Theme 2: Misinterpretation of Rationalisation & Redeployment (R&R) Policy

Education physiotherapists were of the view that educators perceived that implementing SIAS policy might activate the implementation of the R&R policy, which could work against their interests. Implementing the SIAS policy would result in learners being placed according to the level of support they require which may potentially result in a learner being transferred to either a mainstream school or a full-service school. This reassignment could lead to a decrease in school enrollment, affecting staffing levels. Educators misinterpreted that a decline in learner enrollment would make them targets for redeployment under the R&R policy and be placed in other schools they may not prefer [

20]. Hence, educators did not always involve physiotherapists in the assessment and support of learners at schools.

Misinterpretation of the R&R policy has resulted in educators viewing it negatively, seeing it as punitive rather than a strategy to address human resource challenges [

21]. This misinterpretation is likely going to lead to resistance and low morale. Thus, effective communication is crucial. School management and authorities should clearly explain the R&R policy's purpose and objectives, highlighting its strategic, non-punitive nature. Emphasis should be placed on how the SIAS policy aims to support the needs of the learners and improve their educational outcomes. Such communication could alleviate policy misinterpretations and foster a more receptive attitude among educators towards the SIAS process, ultimately benefiting learners, educators and physiotherapist

Sub-Theme 3: Lack of Role and Responsibilities

The lack of involvement and understanding of their role as education physiotherapists in the school environment contributed to their marginalisation which was detrimental to the goal of building inclusive school environments, where the expertise of various professionals, such as physiotherapists, could complement each other to meet the diverse needs of learners effectively. The absence of well-defined directives and designated responsibilities resulted in confusion and uncertainty among teams leading to an improvised approach where education physiotherapists believed they were required to undertake a wide array of tasks without precise guidance [

49,

50]. These findings are consistent with those of other researchers, highlighting the significance of collaboration and teamwork among educators and therapists for establishing inclusive school environments [

19,

51]. Collaborative endeavors and distinct role definitions were crucial in ensuring seamless cooperation among all professionals, including physiotherapists, to effectively cater to learners' needs [

51].

It is vital to address role clarity and collaboration issues among stakeholders to enhance the implementation of SIAS policy and foster inclusive school environments. Precise directives and transparent communication about the involvement and obligations of physiotherapists and other professionals in school committees must be established [

52]. Stressing teamwork and clarifying roles within SBST and DBST can contribute to an effective and comprehensive education system.

Theme 2: LACK OF SUPPORT STRUCTURES

The absence of the CBST meant that the SBST referred school cases directly to the district, bypassing the circuit. Consequently, the DBST would be burdened with many administrative tasks, affecting its effectiveness [

53,

54]. The lack of support towards the SBST by the DBST can be linked to the missing CBST, which could have shared some administrative duties. Additionally, the SBST's focus on aiding only learners rather than both learners and educators limited educators' ability to fully grasp the SIAS policy and the use of the toolkits effectively [

55]. The provincial Department of Education should release resources to strengthen the DBST to perform their duties towards supporting the SBSTs [

48].

Theme 3: Lack of Therapists’ Posts

A possible reason for the vacant posts includes the salary difference between physiotherapists in public schools and those in public hospitals and the availability of funded posts. Physiotherapists in public hospitals tend to get additional allowances such as scarce skills and even rural allowance [

56], which education physiotherapists are not getting. Besides, although therapists in public hospitals reported low levels of job satisfaction pertaining to financial recognition [

57] job satisfaction level seemed to be better when compared to those in the private sector [

58]. Thus, physiotherapists seem to have better job satisfaction whilst working in the private sector than those working the public sector pertaining to salaries.

The shortage of posts and salary discrepancies has possibly led to a lasting staff shortage in the Department of Education. The EWP6 report emphasised the same issue and pointed out that special schools lacked enough specialist professionals and non-teaching staff, worsening the education therapist shortage [

2]. The shortage of school-based physiotherapists implies that physiotherapists appointed at the district level have to perform dual roles in the School-Based Support Teams and District-Based Support Teams.

It might be crucial to offer competitive salaries and incentives to address these problems and attract qualified therapists, including physiotherapists to support learners and educators at the level of the School-Based Support Teams. This approach could help retain skilled professionals and enhance the support available to South African school learners.

Conclusions

Generally, the physiotherapists employed at the Department of Education for Limpopo Province are knowledgeable about the SIAS policy. However, a more systematic and comprehensive training approach might improve their ability to apply the policy effectively and consistently in schools. Other implementation challenges are centred around misconceptions regarding the R&R policy, and unclear roles and responsibilities. These challenges have hindered the creation of inclusive learning environments for learners with disabilities. Moreover, the absence of comprehensive support structures, the missing Circuit-Based Support Teams, and human resource shortages for physiotherapist positions exacerbated the difficulties in the policy implementation.

Various strategies can be considered to enhance the SIAS policy implementation and promote inclusivity for learners with disabilities in the South African education setting. These include providing comprehensive and ongoing in-service training, increase clarifying the R&R policy's purpose, fostering transparent communication, and ensuring well-defined stakeholder roles and responsibilities. Moreover, addressing the gaps in support structures, mainly through establishing functional Circuit-Based Support Teams and offering competitive incentives to attract skilled education physiotherapists could significantly improve the educational landscape for learners with disabilities. The SIAS policy reviewers should emphasize the need to employ education physiotherapists at schools for successful implementation of the policy.

Limitations

While there were 35 special schools in Limpopo Province, the study focused on only three that only admitted learners with physical disabilities because of the physiotherapist that was based at one of the special schools. Thus, the province itself is limited with the number of physiotherapists at schools. The researchers did not determine a statistical intercoder reliability but used a consensus agreement approach to arrive at the conclusion of the three themes that emerged from the data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in the study.

Data Availability

The raw data can be provided upon request.

References

- Education White Paper 6. Special needs education: Building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria: Department of Education; 2001.

- Department of Basic Education (DBE). Report on the Implementation of Education White Paper 6 on Inclusive Education. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education; 2015.

- National Planning Commission. National Development Plan 2030. Pretoria: National Planning Commission; 2010.

- Mkhuma, N.M.; Maseko, N.; Tlale, L.D. Exploring teachers’ views on the challenges of inclusive education in South Africa. South African Journal of Education. 2014, 34, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht, P.; Oswald, M.M.; Forlin, C. Promoting the implementation of inclusive education in primary schools in South Africa. British Journal of Special Education. 2006, 33, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Basic Education (DBE). Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education; 2014.

- Hayes, A.M.; Bulat, J. Disabilities Inclusive Education Systems and Policies Guide for Low-and Middle-Income Countries. RTI Press; 2017. [CrossRef]

- Department of Basic Education. Guidelines for Full-service/Inclusive Schools. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education; 2010.

- Basister, M.P.; Valenzuela, M.L.S. Model of Collaboration for Philippine Inclusive Education. In Instructional Collaboration in International Inclusive Education Contexts. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2020. p. 201-216.

- Du Plessis, P.; Mestry, R. Teachers for rural schools–a challenge for South Africa. South African Journal of Education. 2019, 39 (suppl 1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, M. Education in Rural Areas. South African Journal of Education. 2017, 30, 583–601. [Google Scholar]

- Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). Minimum standard of training for physiotherapy. [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.hpcsa.co.za.

- Hatch, R. Disability screening tools and when to use them: Lessons learnt under the equity initiative. R&E SEARCH for Evidence. [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 11]. Available from: https://researchforevidence.fhi360.org.

- Oberer, N.; Gashaj, V.; Roebers, C.M. Executive functions, visual-motor coordination, physical fitness and academic achievement: Longitudinal relations in typically developing children. Human Movement Science. 2018, 58, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynarczuk, I.; Gomez-Baker, D.; Morrison, K. Physiotherapy’s role in achieving inclusive education: Challenges and solutions. Journal of Rehabilitation Sciences. 2020, 28, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Nel, N.M.; Tlale, L.D.N.; Engelbrecht, P.; Nel, M. Teachers' perceptions of education support structures in the implementation of inclusive education in South Africa. Koers. 2016, 81, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulasmi; Akrim; Basri, M. Management of inclusive education in elementary schools. Int J Innov Creat Change. 2020, 12, 334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Skrypnyk, T.; Martynchuk, O.; Klopota, O.; Gudonis, V.; Voronska, N. Supporting of children with special needs in inclusive environment by the teachers' collaboration. Pedagogika. 2020, 138, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemutandani, N. The management of education redeployment in Limpopo Province. Pretoria: Unisa Press; 2004.

- Mgojo, V.S. Educators and school governing bodies’ perceptions on rationalisation and redeployment in the Alfred-Nzo West District: Advancing an argument for policy change [PhD thesis]. University of Fort Hare, Alice; 2019.

- Khan, N.I. Case Study as a Method of Qualitative Research. In: Management Association IM, editor. Research Anthology on Innovative Research Methodologies and Utilisation Across Multiple Disciplines. IGI Global; 2022. p. 452-72. [CrossRef]

- South African Institute of Race Relations. South Africa Survey 2020. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations; 2020. https://irr.org.za/reports/south-africa-survey [Accessed 19 October 2024].

- Limpopo Department of Education. Annual Performance Plan 2020/21. Polokwane: Limpopo Department of Education; 2020. https://www.edu.limpopo.gov.za [Accessed 19 October 2024].

- Gauteng Department of Education Annual Report. 2022-2023. Publication Details - Gauteng Provincial Government | Visit Us Online [Accessed 19 October 2024].

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, S.; Lomeli-Rodriguez, M.; Joffe, H. From challenge to opportunity: Virtual qualitative research during COVID-19 and beyond. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221105075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keemink, J.R.; Sharp, R.J.; Dargan, A.K.; Forder, J.E. Reflections on the use of synchronous online focus groups in social care research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221095314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberelis, G.; Dimitriadis, G. Focus groups: Strategic articulations of pedagogy, politics, and inquiry. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. p. 887-907.

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Frels, R.K. A framework for conducting critical dialectical pluralist focus group discussions using mixed method research techniques. J Educ Issues. 2015, 1, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P.I.; Fusch, G.; Ness, L.R.D. Introduction to focus group methodology. International Journal of Business Research. 2022, 18, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshed, S. Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2014, 5, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K. Protecting respondent confidentiality in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2009, 19, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawadi, S. Thematic analysis approach: A step-by-step guide for ELT research practitioners. Journal of NELTA 2021, 25, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Weber, M.B. What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research 2019, 29, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-González, P.; Martínez-Castillo, J.L.; Fernández-Galván, L.M.; Casado, A.; Soporki, S.; Sánchez-Infante, J. Epidemiology of sports-related injuries and associated risk factors in adolescent athletes: An injury surveillance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021, 18, 4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.K.C.; Tai, K.W. The use of intercoder reliability in qualitative interview data analysis in science education. Research in Science & Technological Education. 2023, 41, 1155–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L.; Adkins, D.; Chauvin, S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2020, 84, 7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKim, C. Meaningful member-checking: A structured approach to member-checking. American Journal of Qualitative Research. 2023, 7, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Assembly of the World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Journal of the American College of Dentists. 2014, 81, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, Q.A.; Berner, K.; Tiwari, R.; Ernstzen, D.; Bedada, D.T.; Coetzee, M.; Chikte, U. Demographic transformation of the physiotherapy profession in South Africa: A retrospective analysis of HPCSA registrations from 1938 to 2018. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2021, 27, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jita, L.C.; Mokhele, M.L. When teacher clusters work: Selected experiences of South African teachers with the cluster approach to professional development. South African Journal of Education 2014, 34, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoko, T.; Phasha, N. 2018. The State of Inclusive Education In South Africa and the Implications For Teacher Training Programmes. Teaching for All Research Report. Roodepoort: British Council. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30210.56009. [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.A. Teachers' Perceptions Regarding the Implementation of the Screening, Identification, Assessment, and Support Policy in Mainstream Schools [master's thesis]. Stellenbosch University, Cape Town; 2020.

- Matolo, M.F.; Rambuda, A.M. Evaluation of the Application of an Inclusive Education Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support of the Learners at Schools in South Africa. Int J Educ Pract. 2022, 10, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphumulo, T.B. Exploring the role of a school based support team (SBST) in supporting teachers at a rural primary school (Doctoral dissertation).

- Hemmingsson, H.; Gustavsson, A.; Townsend, E. Students with disabilities participating in mainstream schools: Policies that promote and limit teacher and therapist cooperation. Disabil Soc. 2007, 22, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsrud, D.; Nilholm, C. Teaching for inclusion–a review of research on the cooperation between regular teachers and special educators in the work with students in need of special support. Int J Incl Educ. 2023, 27, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Melgar, A.; Hyett, N.; Bagley, K.; McKinstry, C.; Spong, J.; Iacono, T. Collaborative team approaches to supporting inclusion of children with disability in mainstream schools: A co-design study. Res Dev Disabil. 2022, 126, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntseto, R.M.; Kgothule, R.J.; Ugwuanyi, C.S.; Okeke, C.I. Exploring the impediments to the Implementation of policy of screening, identification, assessment and support in schools: Implications for Educational Evaluators. J Crit Rev. 2021, 8, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Mfuthwana, T.; Dreyer, L.M. Establishing inclusive schools: Teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education teams. South African Journal of Education. 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpanza, L.P.; Govender, S. Primary School-Based Support Teams' Experiences and Practices When Supporting Teachers. Multicultural Educ. 2022, 8, 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Makhalemele, T.; Tlale, L.D. Exploring the effectiveness of school-based support team in special schools to support teachers. e-BANGI. 2020, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chelule, P.K.; Madiba, S. Assessment of the effectiveness of rural allowances as a strategy for recruiting and retaining health professionals in rural public hospitals in the Northwest Province, South Africa. Afr J Phys Health Educ Recr Dance. 2014, 20 (Suppl 1), 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Makholwa, N.; Tlou, B.; Dlungwane, T.P. Job satisfaction among rehabilitation professionals employed in public health facilities in KwaZulu-Natal. Afr Health Sci. 2023, 23, 764–772. [Google Scholar]

- Motloutsi, M.J. A comparative study on physiotherapists' job satisfaction in the private and public health facilities of Gauteng [master's thesis]. North-West University; 2015.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).