Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

Risk of Antibiotics and Antibiotics Resistance:

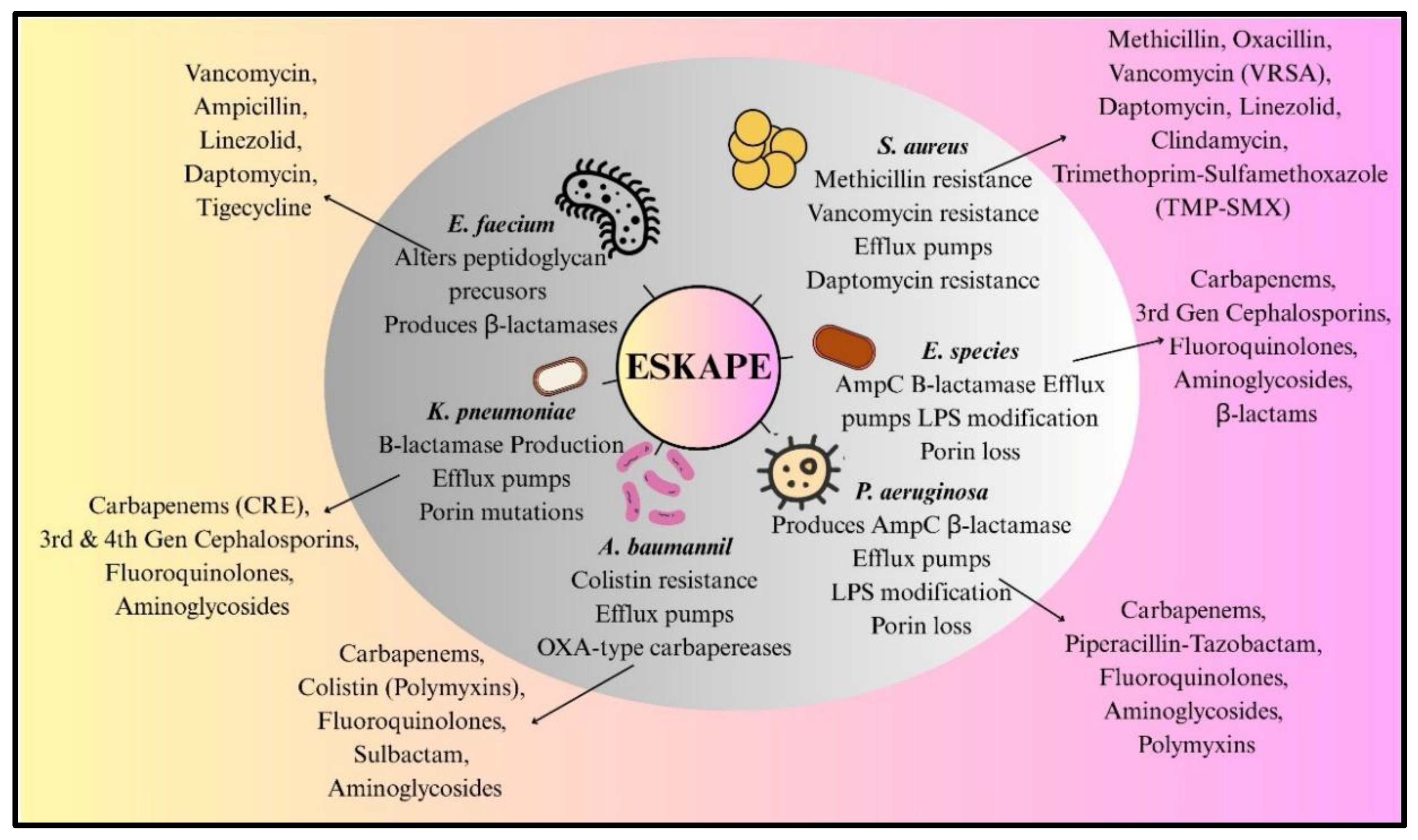

ESKAPE Pathogens Antibiotic Resistance and Mechanisms:

Alternatives Strategies and Adjuvants for ABR Treatments:

Adjuvants are Non-Antibiotic Compounds That Potentiate Antimicrobial Activity:

| Class I (Anti-resistance agents) | These include efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) and β-lactamase inhibitors. Phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PaβN), a peptidomimetic EPI, blocks the AcrAB-TolC pump in E. coli, increasing intracellular concentrations of fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines [61]. For β-lactamases, next-generation inhibitors like relebactam (a Diazabicyclooctane (DBO derivative) extend the utility of imipenem against MBL-producing strains [62]. |

| Class II (Anti-virulence agents) | Quorum sensing inhibitors (QSIs) such as furanone C-30 disrupt P. aeruginosa biofilm formation by mimicking AHL signals, reducing pyocyanin and elastase production [63,64]. Monoclonal antibodies targeting Clostridium difficile toxins TcdA and TcdB neutralize virulence without affecting bacterial growth, offering a pathogen-specific approach [65]. |

Anti-Virulence and Gene Editing Strategies:

Vaccines and Antibiotic Resistance:

Bacteriophage Therapy:

Technological Advancements:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Use in Surveillance of ABR:

Conclusion and Future Prospective:

Author Contributions

Data Sharing Statement

Disclosure

References

- Sati H, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: a prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. Published online September 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. WHO Publishes List of Bacteria for Which New Antibiotics Are Urgently Needed. Saudi Med J. 2017;(February).

- Ahmed SK, Hussein S, Qurbani K, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health. 2024;2. [CrossRef]

- Marti E, Variatza E, Balcazar JL. The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Huijbers PMC, Blaak H, De Jong MCM, Graat EAM, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, De Roda Husman AM. Role of the Environment in the Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance to Humans: A Review. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(20). [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse MEJ, Ward MJ. Sources of antimicrobial resistance. Science (1979).American Association for the Advancement of Science. 2013;341(6153):1460-1461. [CrossRef]

- Holmes AH, Moore LSP, Sundsfjord A, et al. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. The Lancet. 2016;387(10014). [CrossRef]

- Aslam B, Khurshid M, Arshad MI, et al. Antibiotic Resistance: One Health One World Outlook. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Pardo JR, Lood R, Udekwu K, et al. A One Health – One World initiative to control antibiotic resistance: A Chile - Sweden collaboration. One Health. 2019;8. [CrossRef]

- Sassi A, Basher NS, Kirat H, et al. The Role of the Environment (Water, Air, Soil) in the Emergence and Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. Antibiotics. 2025;14(8):764. [CrossRef]

- Pandey S, Doo H, Keum GB, et al. Antibiotic resistance in livestock, environment and humans: One Health perspective. J Anim Sci Technol. 2024;62(2). [CrossRef]

- Burow E, Käsbohrer A. Risk Factors for Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli in Pigs Receiving Oral Antimicrobial Treatment: A Systematic Review. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2017;23(2). [CrossRef]

- Naghavi M, Vollset SE, Ikuta KS, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet. 2024;404(10459):1199-1226. [CrossRef]

- Lee AS, De Lencastre H, Garau J, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4. [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh C, Mamphweli S, Meyer E, Okoh A. Antibiotic use in agriculture and its consequential resistance in environmental sources: Potential public health implications. Molecules. 2018;23(4). [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Sun QL, Shen Y, et al. Rapid increase in prevalence of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and emergence of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in CRE in a hospital in Henan, China. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56(4). [CrossRef]

- Ramadan AA, Abdelaziz NA, Amin MA, Aziz RK. Novel blaCTX-M variants and genotype-phenotype correlations among clinical isolates of extended spectrum beta lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, Yasmeen N, Pandey A, et al. Antibiotic adjuvants: synergistic tool to combat multi-drug resistant pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13. [CrossRef]

- Mafe AN, Büsselberg D. Phage Therapy in Managing Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Infections in Cancer Therapy: Innovations, Complications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics.Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). 2025;17(7). [CrossRef]

- Okesanya OJ, Ahmed MM, Ogaya JB, et al. Reinvigorating AMR resilience: leveraging CRISPR–Cas technology potentials to combat the 2024 WHO bacterial priority pathogens for enhanced global health security—a systematic review. Trop Med Health.BioMed Central Ltd. 2025;53(1). [CrossRef]

- Zenner D, Beer N, Harris RJ, Lipman MC, Stagg HR, Van Der Werf MJ. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: An updated network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med.American College of Physicians. 2017;167(4):248-255. [CrossRef]

- Vidaver AK. Uses of antimicrobials in plant agriculture. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;34(SUPPL. 3). [CrossRef]

- McEwen SA, Collignon PJ. Antimicrobial Resistance: a One Health Perspective. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6(2). [CrossRef]

- Kasimanickam V, Kasimanickam M, Kasimanickam R. Antibiotics Use in Food Animal Production: Escalation of Antimicrobial Resistance: Where Are We Now in Combating AMR? Medical sciences. 2021;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis L, Papachristodoulou E, Chra P, Panos G. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in important gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens and novel antibiotic solutions. Antibiotics. 2021;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Blair JMA, Webber MA, Baylay AJ, Ogbolu DO, Piddock LJV. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Michaelis C, Grohmann E. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms. Antibiotics. 2023;12(2). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Beltrán J, DelaFuente J, León-Sampedro R, MacLean RC, San Millán Á. Beyond horizontal gene transfer: the role of plasmids in bacterial evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(6). [CrossRef]

- Aslam B, Wang W, Arshad MI, et al. Antibiotic resistance: a rundown of a global crisis. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Zhang TT, Yu J, et al. Excess Body Weight during Childhood and Adolescence Is Associated with the Risk of Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;47(2). [CrossRef]

- McFarland L V., Evans CT, Goldstein EJC. Strain-specificity and disease-specificity of probiotic efficacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5(MAY). [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Amado S, Coque TM, Baquero F, Martínez JL. Defining and combating antibiotic resistance from One Health and Global Health perspectives. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(9). [CrossRef]

- Cycoń M, Mrozik A, Piotrowska-Seget Z. Antibiotics in the soil environment—degradation and their impact on microbial activity and diversity. Front Microbiol. 2019;10(MAR). [CrossRef]

- Jim YK, Shakow A, Mate K, Vanderwarker C, Gupta R, Farmer P. Limited good and limited vision: Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and global health policy. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(4 SPEC. ISS.). [CrossRef]

- Auta A, Hadi MA, Oga E, et al. Global access to antibiotics without prescription in community pharmacies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Infection. 2019;78(1). [CrossRef]

- Keenan JD, Bailey RL, West SK, et al. Azithromycin to Reduce Childhood Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(17). [CrossRef]

- Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, et al. Characterization of a new metallo-β-lactamase gene, bla NDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(12). [CrossRef]

- Singh AR. Science, names giving and names calling: Change NDM-1 to PCM. Mens Sana Monogr. 2011;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Pollini S, Maradei S, Pecile P, et al. FIM-1, a new acquired metallo-β-lactamase from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate from Italy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(1). [CrossRef]

- Bhat BA, Mir RA, Qadri H, et al. Integrons in the development of antimicrobial resistance: critical review and perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup FM, Seyfarth AM, Emborg HD, Pedersen K, Hendriksen RS, Bager F. Effect of abolishment of the use of antimicrobial agents for growth promotion on occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in fecal enterococci from food animals in Denmark. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(7). [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(18). [CrossRef]

- Fernando DM, Kumar A. Resistance-Nodulation-Division multidrug efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria: Role in virulence. Antibiotics. 2013;2(1). [CrossRef]

- Sulavik MC, Houseweart C, Cramer C, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(4). [CrossRef]

- Buynak JD. β-Lactamase inhibitors: A review of the patent literature (2010 - 2013). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23(11). [CrossRef]

- Marshall S, Hujer AM, Rojas LJ, et al. Can ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam overcome β-lactam resistance conferred by metallo-β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(4). [CrossRef]

- Marino A, Maraolo AE, Mazzitelli M, et al. Head-to-head: meropenem/vaborbactam versus ceftazidime/avibactam in ICUs patients with KPC-producing K. pneumoniae infections– results from a retrospective multicentre study. Infection. Published online 2025. [CrossRef]

- Guillot MF, Cerezuela MM, Ramírez P. New evidence in severe pneumonia: meropenemvaborbactam. Revista Espanola de Quimioterapia. 2022;35. [CrossRef]

- Petrosillo N, Chinello P, Proietti MF, et al. Combined colistin and rifampicin therapy for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections: Clinical outcome and adverse events [1]. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2005;11(8). [CrossRef]

- Lee HJ, Bergen PJ, Bulitta JB, et al. Synergistic activity of colistin and rifampin combination against multidrug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/ pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(8). [CrossRef]

- Sychantha D, Rotondo CM, Tehrani KHME, Martin NI, Wright GD. Aspergillomarasmine A inhibits metallo-β-lactamases by selectively sequestering Zn2+. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2021;297(2). [CrossRef]

- Jin W Bin, Xu C, Cheung Q, et al. Bioisosteric investigation of ebselen: Synthesis and in vitro characterization of 1,2-benzisothiazol-3(2H)-one derivatives as potent New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2020;100. [CrossRef]

- Lu Q, Cai Y, Xiang C, et al. Ebselen, a multi-target compound: Its effects on biological processes and diseases. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2021;23. [CrossRef]

- Albarri O, AlMatar M, Öcal MM, Köksal F. Overexpression of Efflux Pumps AcrAB and OqxAB Contributes to Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Clinical Isolates of K. pneumoniae. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2022;23(5). [CrossRef]

- Weston N, Sharma P, Ricci V, Piddock LJV. Regulation of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump in Enterobacteriaceae. Res Microbiol. 2018;169(7-8). [CrossRef]

- Bharatham N, Bhowmik P, Aoki M, et al. Structure and function relationship of OqxB efflux pump from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Schmitz FJ, Fluit AC, Lückefahr M, et al. The effect of reserpine, an inhibitor of multidrug efflux pumps, on the in-vitro activities of ciprofloxacin, sparfloxacin and moxifloxacin against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1998;42(6). [CrossRef]

- Costa SS, Viveiros M, Amaral L, Couto I. Multidrug Efflux Pumps in Staphylococcus aureus: an Update. Open Microbiol J. 2013;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Vargiu A V., Ruggerone P, Opperman TJ, Nguyen ST, Nikaido H. Molecular mechanism of MBX2319 inhibition of Escherichia coli AcrB multidrug efflux pump and comparison with other inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(10). [CrossRef]

- White M, Lenzi K, Dutcher LS, et al. 124. Impact of Levofloxacin MIC on Outcomes with Levofloxacin Step-down Therapy in Enterobacteriaceae Bloodstream Infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(Supplement_2). [CrossRef]

- Lamers RP, Cavallari JF, Burrows LL. The Efflux Inhibitor Phenylalanine-Arginine Beta-Naphthylamide (PAβN) Permeabilizes the Outer Membrane of Gram-Negative Bacteria. PLoS One. 2013;8(3). [CrossRef]

- Karaiskos I, Galani I, Daikos GL, Giamarellou H. Breaking Through Resistance: A Comparative Review of New Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors (Avibactam, Vaborbactam, Relebactam) Against Multidrug-Resistant Superbugs. Antibiotics.Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). 2025;14(5). [CrossRef]

- Bové M, Bao X, Sass A, Crabbé A, Coenye T. The quorum-sensing inhibitor furanone C-30 rapidly loses its tobramycin-potentiating activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms during experimental evolution. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65(7). [CrossRef]

- Proctor CR, McCarron PA, Ternan NG. Furanone quorum-sensing inhibitors with potential as novel therapeutics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol. 2020;69(2). [CrossRef]

- Kroh HK, Jensen JL, Wellnitz S, et al. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against Clostridioides difficile toxins TcdA and TcdB target diverse epitopes for neutralization. Freitag NE, ed. Infect Immun. Published online August 22, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Anantharajah A, Buyck JM, Sundin C, Tulkens PM, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Van Bambeke F. Salicylidene acylhydrazides and hydroxyquinolines act as inhibitors of type three secretion systems in pseudomonas aeruginosa by distinct mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(6). [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren MK, Zetterström CE, Gylfe Å, Linusson A, Elofsson M. Statistical molecular design of a focused salicylidene acylhydrazide library and multivariate QSAR of inhibition of type III secretion in the Gram-negative bacterium Yersinia. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18(7). [CrossRef]

- Brackman G, Breyne K, De Rycke R, et al. The Quorum Sensing Inhibitor Hamamelitannin Increases Antibiotic Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms by Affecting Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis and eDNA Release. Sci Rep. 2016;6. [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Brooks SA, Eszterhas S, et al. Globally deimmunized lysostaphin evades human immune surveillance and enables highly efficacious repeat dosing. Sci Adv. 2020;6(36). [CrossRef]

- Zha J, Li J, Su Z, Akimbekov N, Wu X. Lysostaphin: Engineering and Potentiation toward Better Applications. J Agric Food Chem. 2022;70(37). [CrossRef]

- Royer-Bertrand B, Rivolta C. Whole genome sequencing as a means to assess pathogenic mutations in medical genetics and cancer. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2015;72(8). [CrossRef]

- Beal MA, Glenn TC, Somers CM. Whole genome sequencing for quantifying germline mutation frequency in humans and model species: Cautious optimism. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2012;750(2). [CrossRef]

- Hung DT, Shakhnovich EA, Pierson E, Mekalanos JJ. Small-molecule inhibitor of Vibrio cholerae virulence and intestinal colonization. Science (1979). 2005;310(5748). [CrossRef]

- Woodbrey AK, Onyango EO, Kovacikova G, Kull FJ, Gribble GW. A Modified ToxT Inhibitor Reduces Vibrio cholerae Virulence in Vivo. Biochemistry. 2018;57(38). [CrossRef]

- Micoli F, Bagnoli F, Rappuoli R, Serruto D. The role of vaccines in combatting antimicrobial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(5). [CrossRef]

- Lipsitch M, Siber GR. How can vaccines contribute to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem? mBio. 2016;7(3). [CrossRef]

- Jansen KU, Anderson AS. The role of vaccines in fighting antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(9). [CrossRef]

- Hasso-Agopsowicz M, Sparrow E, Cameron AM, et al. The role of vaccines in reducing antimicrobial resistance: A review of potential impact of vaccines on AMR and insights across 16 vaccines and pathogens. Vaccine. 2024;42(19):S1-S8. [CrossRef]

- Gilsdorf JR. Hib Vaccines: Their Impact on Haemophilus influenzae Type b Disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;224. [CrossRef]

- Sempere J, Llamosí M, López Ruiz B, et al. Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and SARS-CoV-2 on antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes with reduced susceptibility in Spain, 2004–20: a national surveillance study. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(10). [CrossRef]

- van Heuvel L, Paget J, Dückers M, Caini S. The impact of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination on antibiotic use: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2023;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Nampota-Nkomba N, Carey ME, Jamka LP, Fecteau N, Neuzil KM. Using Typhoid Conjugate Vaccines to Prevent Disease, Promote Health Equity, and Counter Drug-Resistant Typhoid Fever. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- DiGiandomenico A, Keller AE, Gao C, et al. A multifunctional bispecific antibody protects against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(262). [CrossRef]

- Gulati S, Beurskens FJ, de Kreuk BJ, et al. Complement alone drives efficacy of a chimeric antigonococcal monoclonal antibody. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(6). [CrossRef]

- Lima R, Del Fiol FS, Balcão VM. Prospects for the use of new technologies to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10(JUN). [CrossRef]

- ault P, Leclerc T, Jennes S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a cocktail of bacteriophages to treat burn wounds infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PhagoBurn): a randomised, controlled, double-blind phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(1). [CrossRef]

- Aslam B, Arshad MI, Aslam MA, et al. Bacteriophage Proteome: Insights and Potentials of an Alternate to Antibiotics. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(3). [CrossRef]

- Patel DR, Bhartiya SK, Kumar R, Shukla VK, Nath G. Use of Customized Bacteriophages in the Treatment of Chronic Nonhealing Wounds: A Prospective Study. International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds. 2021;20(1). [CrossRef]

- Sabouri S, Sepehrizadeh Z, Amirpour-Rostami S, Skurnik M. A minireview on the in vitro and in vivo experiments with anti-Escherichia coli O157:H7 phages as potential biocontrol and phage therapy agents. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017;243. [CrossRef]

- Almeida GMF, Mäkelä K, Laanto E, Pulkkinen J, Vielma J, Sundberg LR. The fate of bacteriophages in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS)—towards developing phage therapy for RAS. Antibiotics. 2019;8(4). [CrossRef]

- Fischetti VA. Development of phage lysins as novel therapeutics: A historical perspective. Viruses. 2018;10(6). [CrossRef]

- Merabishvili M, Pirnay JP, Verbeken G, et al. Quality-controlled small-scale production of a well-defined bacteriophage cocktail for use in human clinical trials. PLoS One. 2009;4(3). [CrossRef]

- Sahota JS, Smith CM, Radhakrishnan P, et al. Bacteriophage Delivery by Nebulization and Efficacy Against Phenotypically Diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Cystic Fibrosis Patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28(5). [CrossRef]

- Nale JY, Spencer J, Hargreaves KR, Trzepiński P, Douce GR, Clokie MRJ. Bacteriophage combinations significantly reduce Clostridium difficile growth in vitro and proliferation in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(2). [CrossRef]

- de Abreu RC, Fernandes H, da Costa Martins PA, Sahoo S, Emanueli C, Ferreira L. Native and bioengineered extracellular vesicles for cardiovascular therapeutics. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(11). [CrossRef]

- Chen K, Pachter L. Bioinformatics for whole-genome shotgun sequencing of microbial communities. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1(2). [CrossRef]

- De R. Metagenomics: Aid to combat antimicrobial resistance in diarrhea. Gut Pathog. 2019;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Moon CD, Zheng N, Huws S, Zhao S, Wang J. Opportunities and challenges of using metagenomic data to bring uncultured microbes into cultivation. Microbiome. 2022;10(1). [CrossRef]

- Khedkar S, Smyshlyaev G, Letunic I, et al. Landscape of mobile genetic elements and their antibiotic resistance cargo in prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(6). [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie JS, Jeggo M. The one health approach-why is it so important? Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;4(2). [CrossRef]

- Macesic N, Polubriaginof F, Tatonetti NP. Machine learning: Novel bioinformatics approaches for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30(6). [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar P, Chen E, Banerjee O, Topol EJ. AI in health and medicine. Nat Med. 2022;28(1). [CrossRef]

- Blechman SE, Wright ES. Applications of Machine Learning on Electronic Health Record Data to Combat Antibiotic Resistance. Journal of Infectious Diseases.Oxford University Press. 2024;230(5):1073-1082. [CrossRef]

- Vamathevan J, Clark D, Czodrowski P, et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(6). [CrossRef]

- Wachino, Jun-ichi. "Horizontal Gene Transfer Systems for Spread of Antibiotic Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria." Microbiology and Immunology. 2025; 69.7: 367-376.

- Pfaller, Michael A. "Flavophospholipol use in animals: positive implications for antimicrobial resistance based on its microbiologic properties." Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2006; 56.2: 115-121.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).