Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

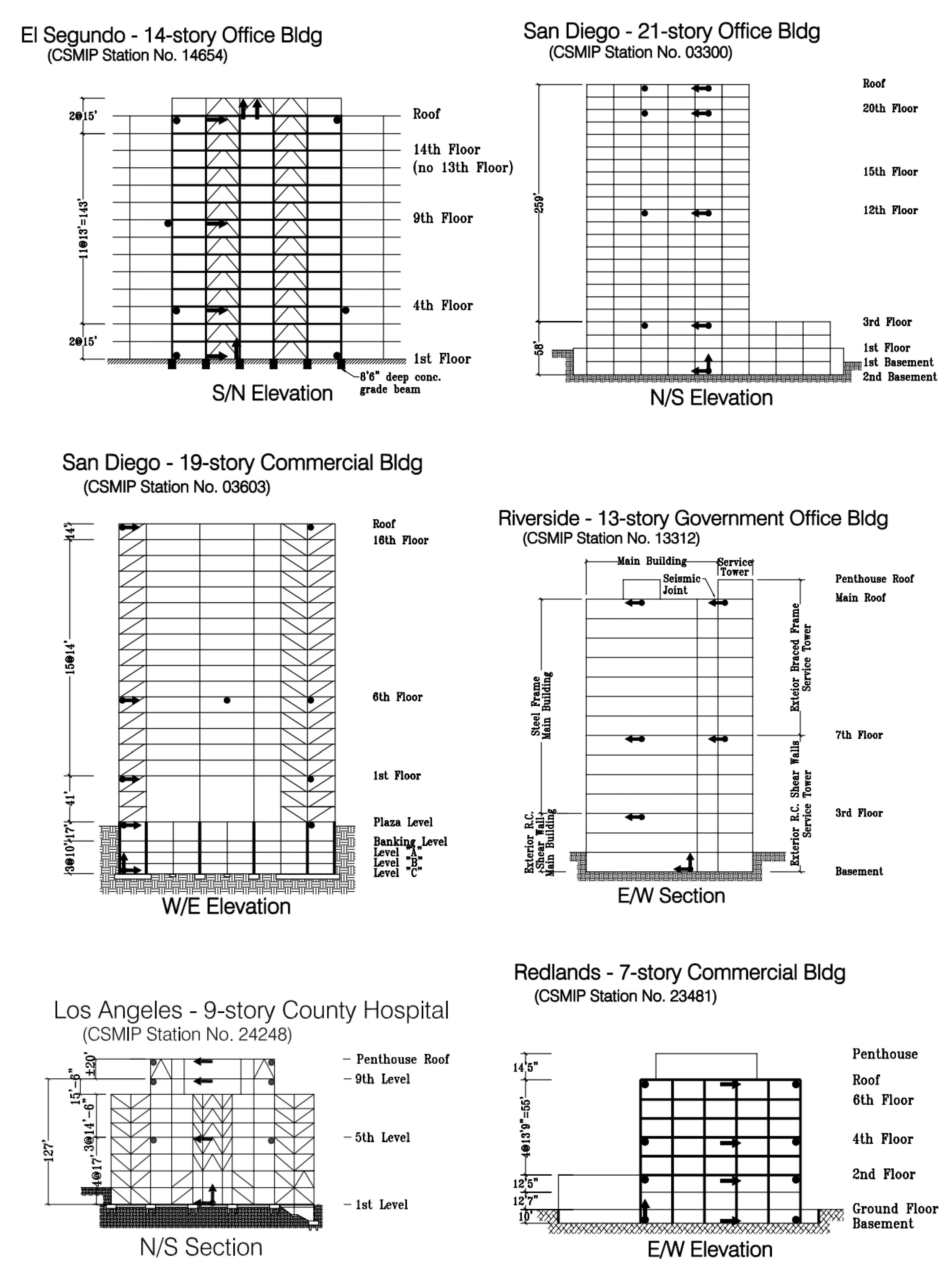

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Proposed Approach

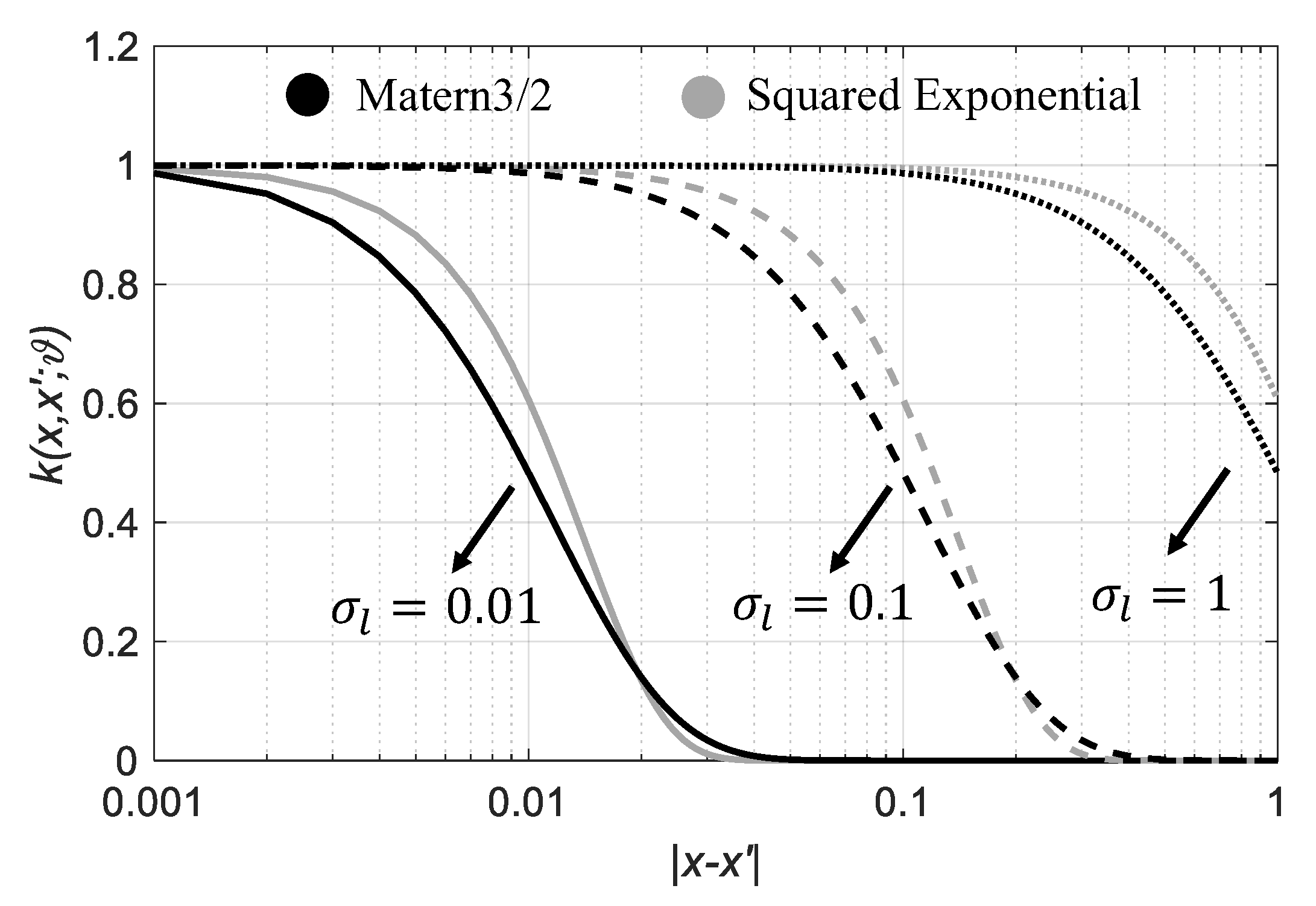

2.1. Gaussian Process Regression

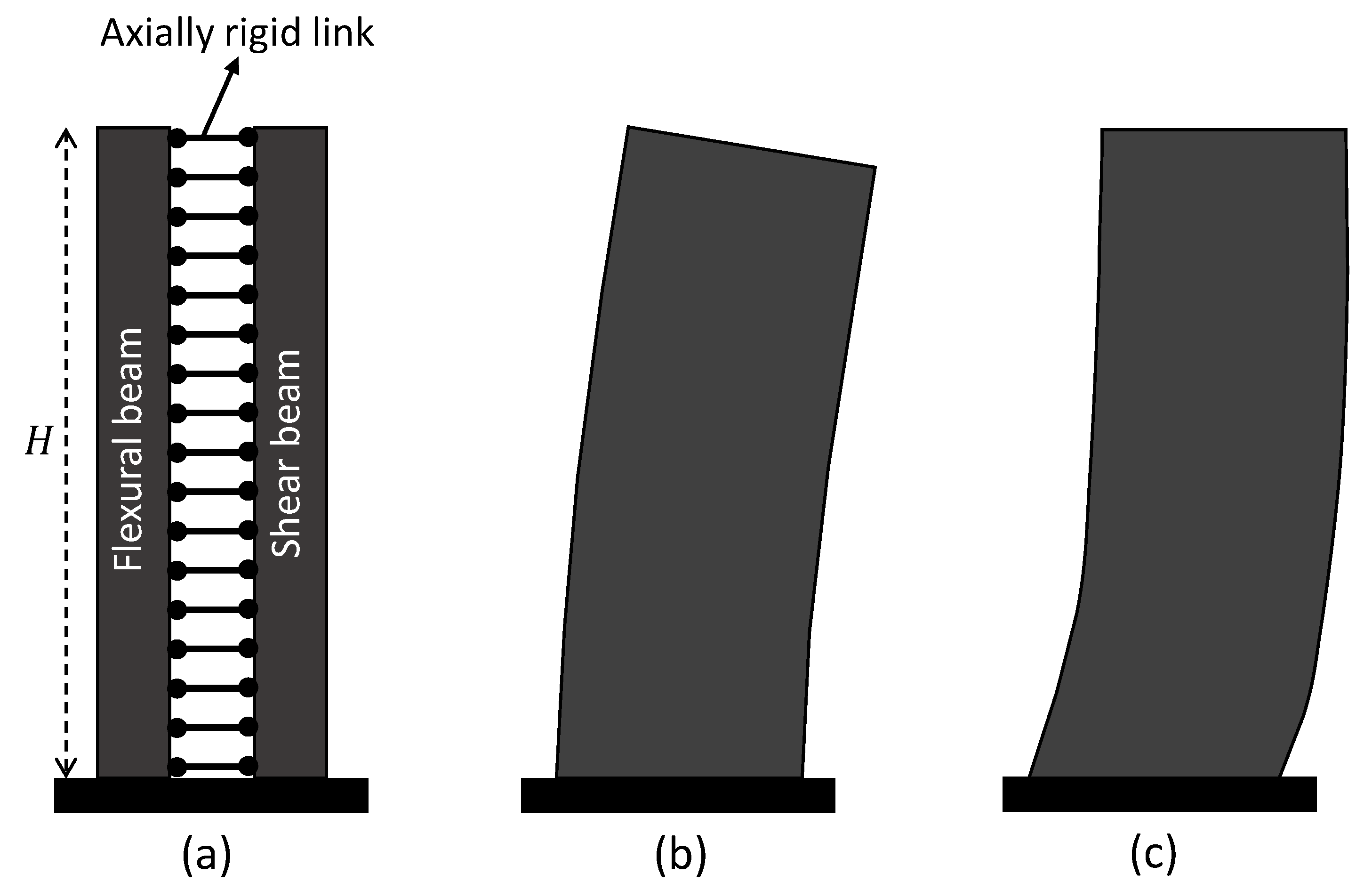

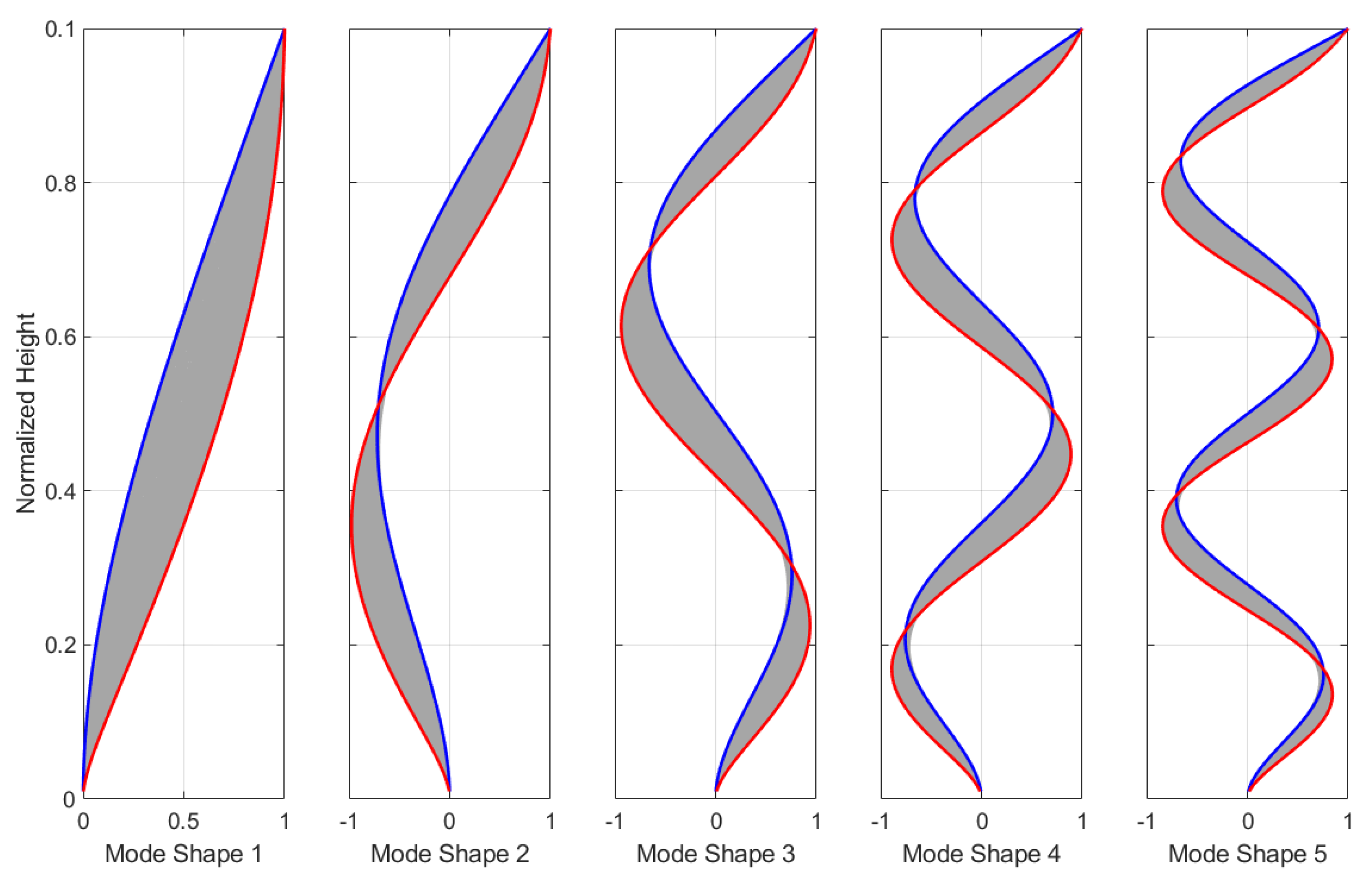

2.2. Analytical Covariance Kernel Using Beam Model

2.3. The Objective Function

- In shear wall and braced frame buildings, typically ranges between 0 and 1.5.

- In dual structural systems—such as a combination of moment-resisting frames with shear walls or braced frames— usually falls between 1.5 and 5.

- In moment-resisting frame buildings, typically ranges from 5 and 20.

3. Case Studies

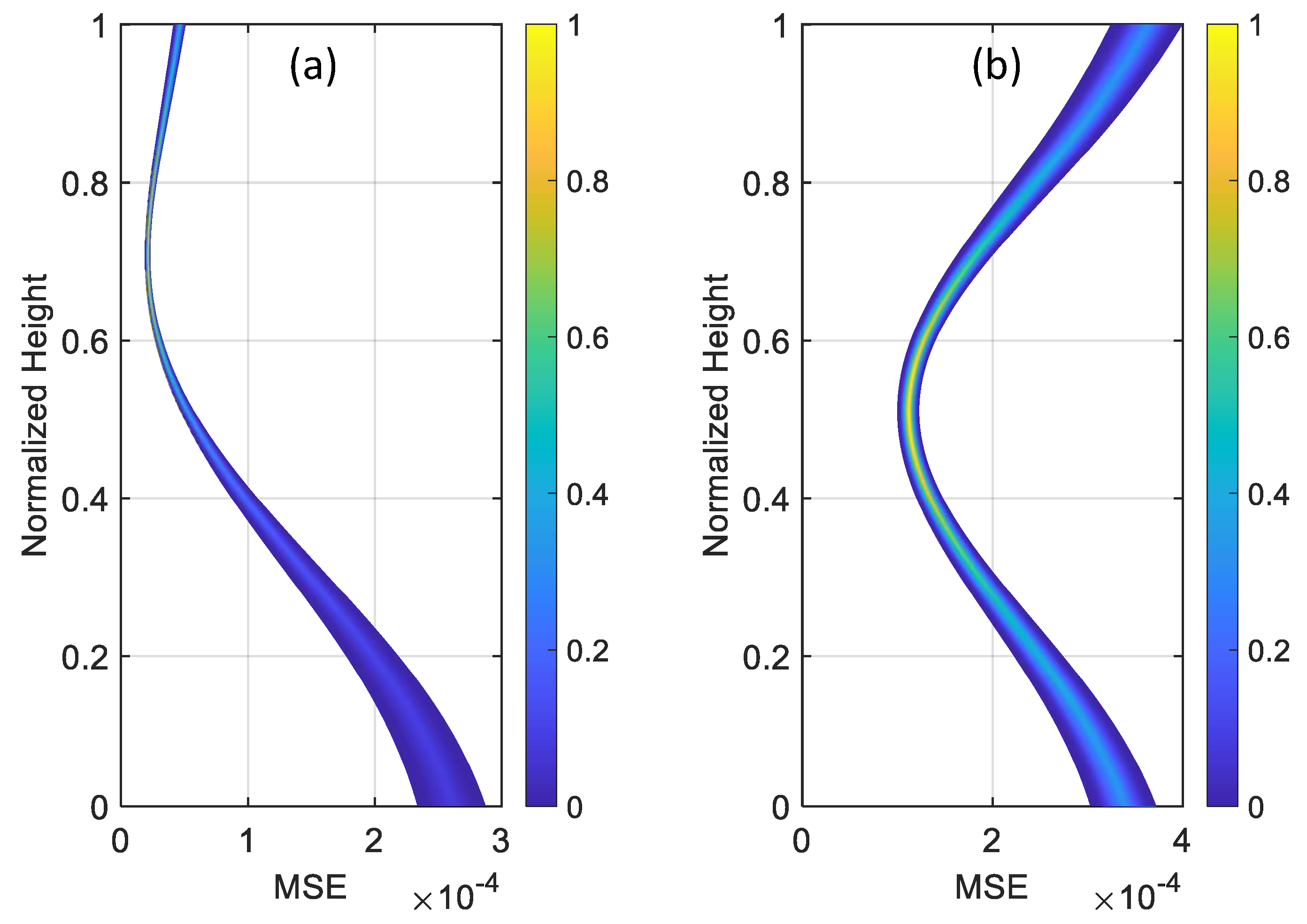

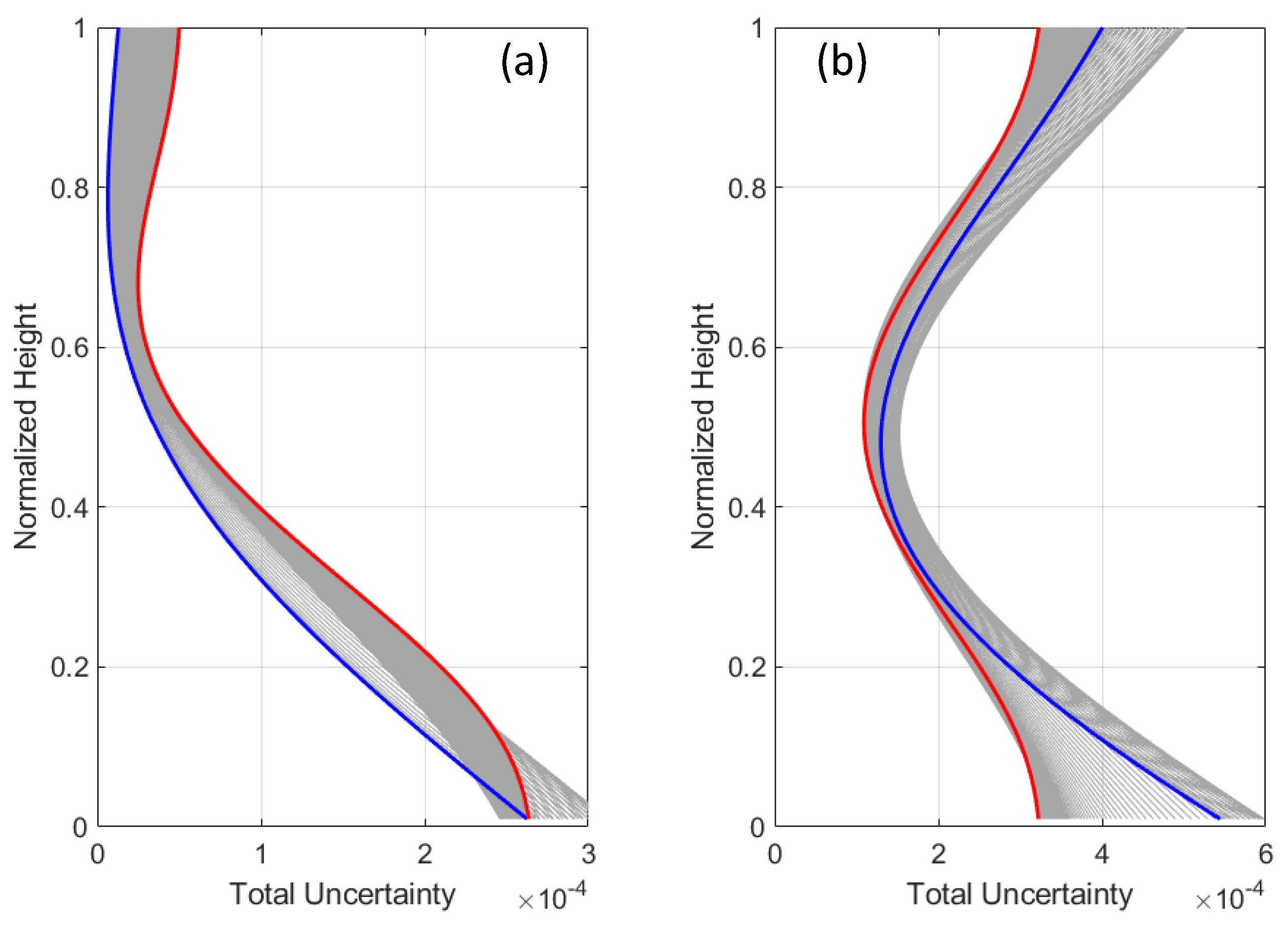

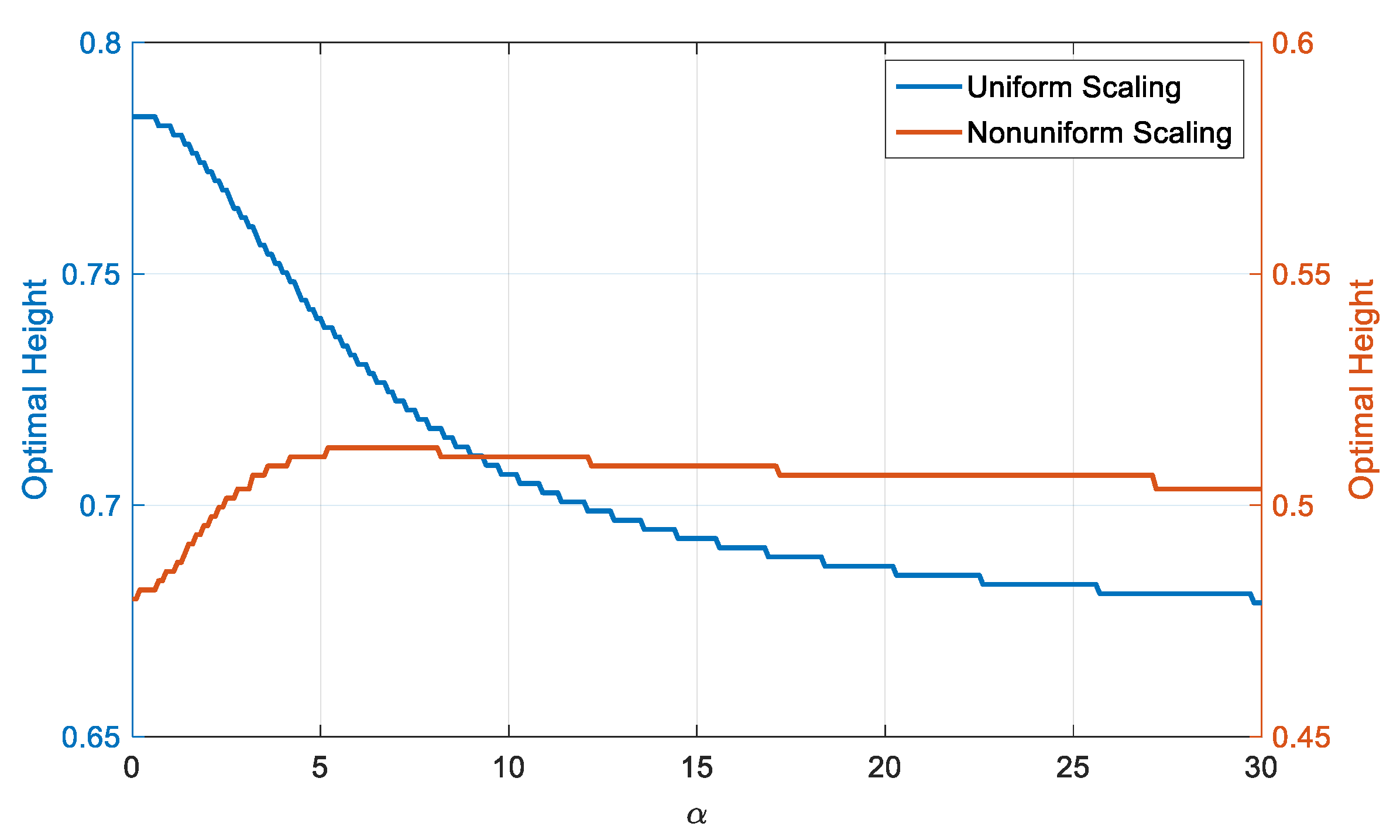

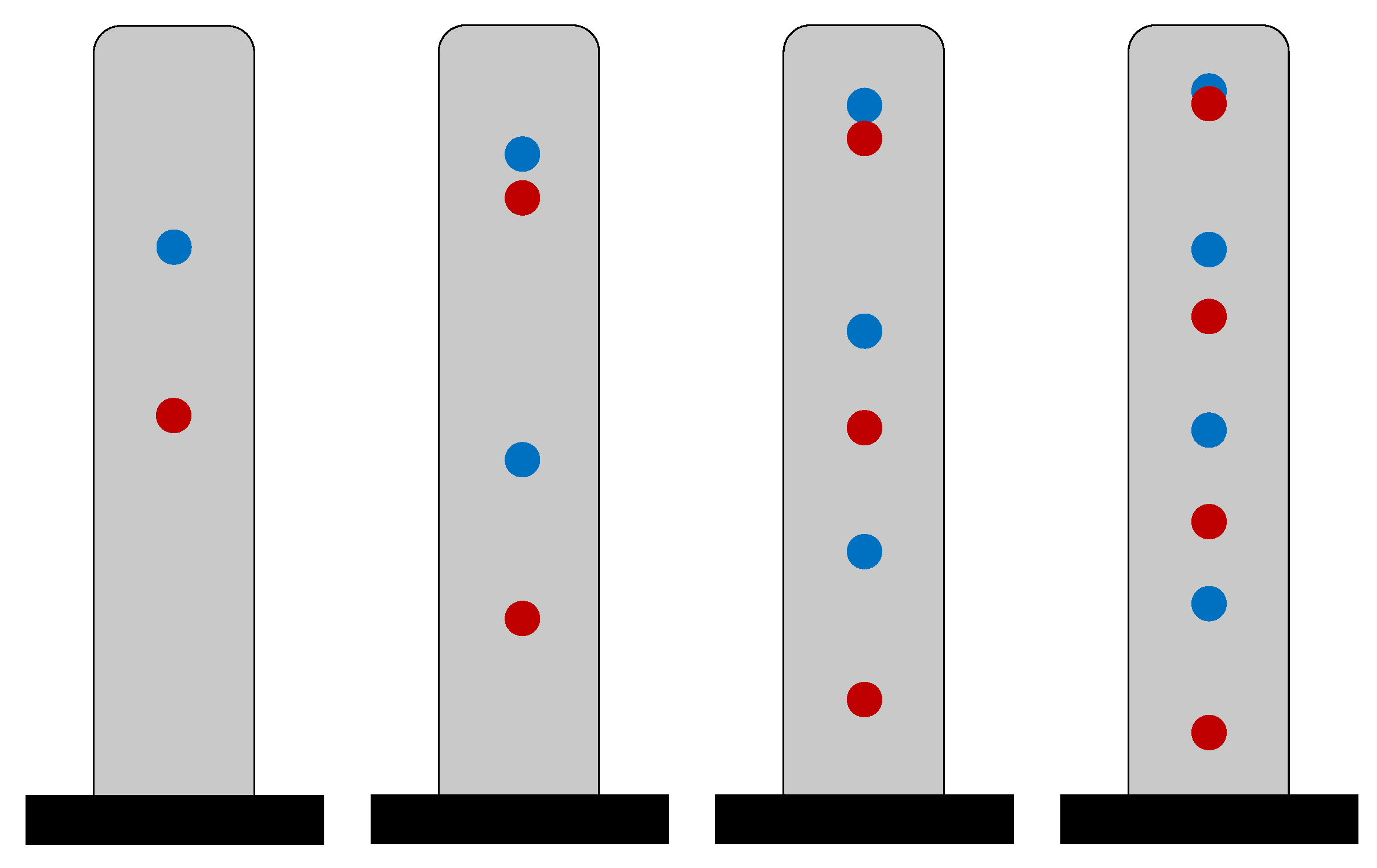

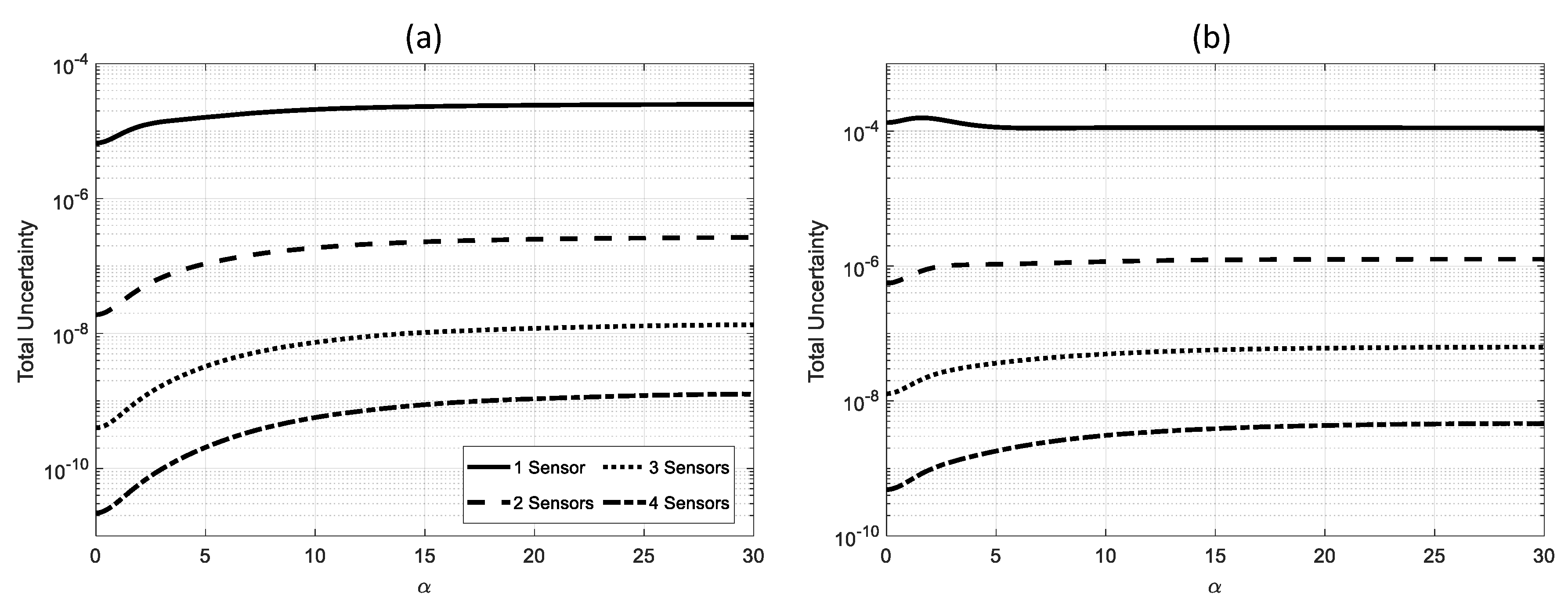

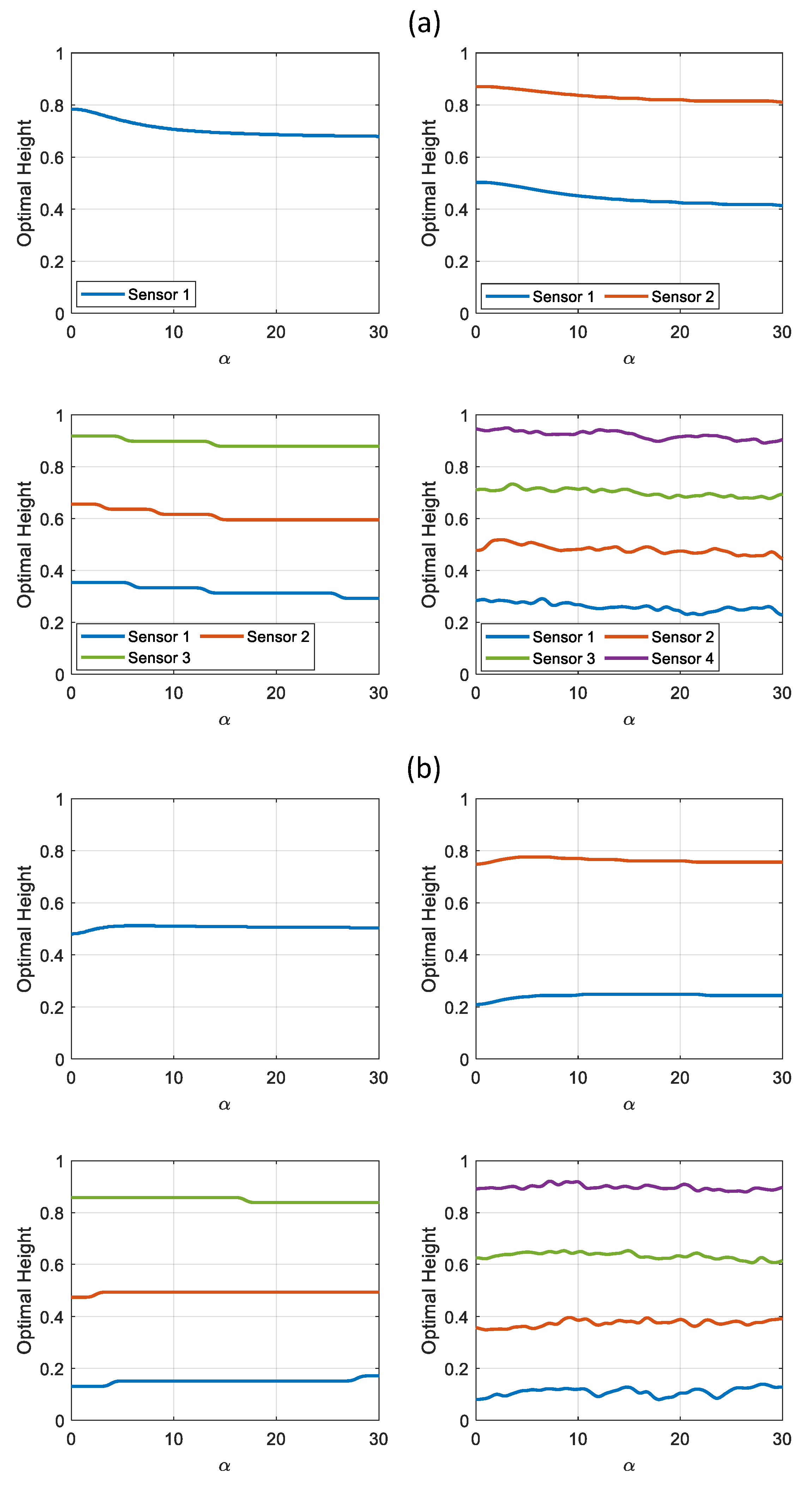

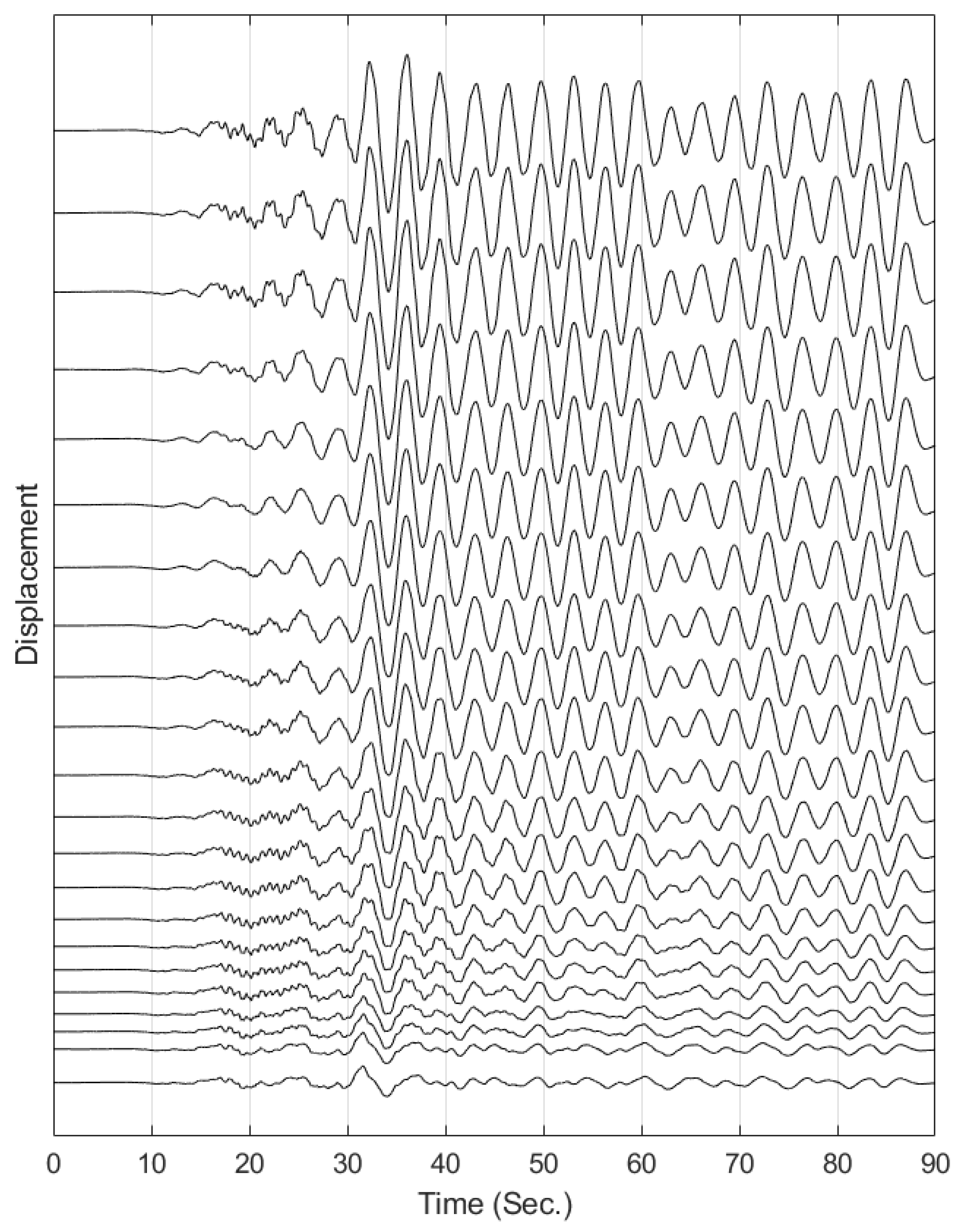

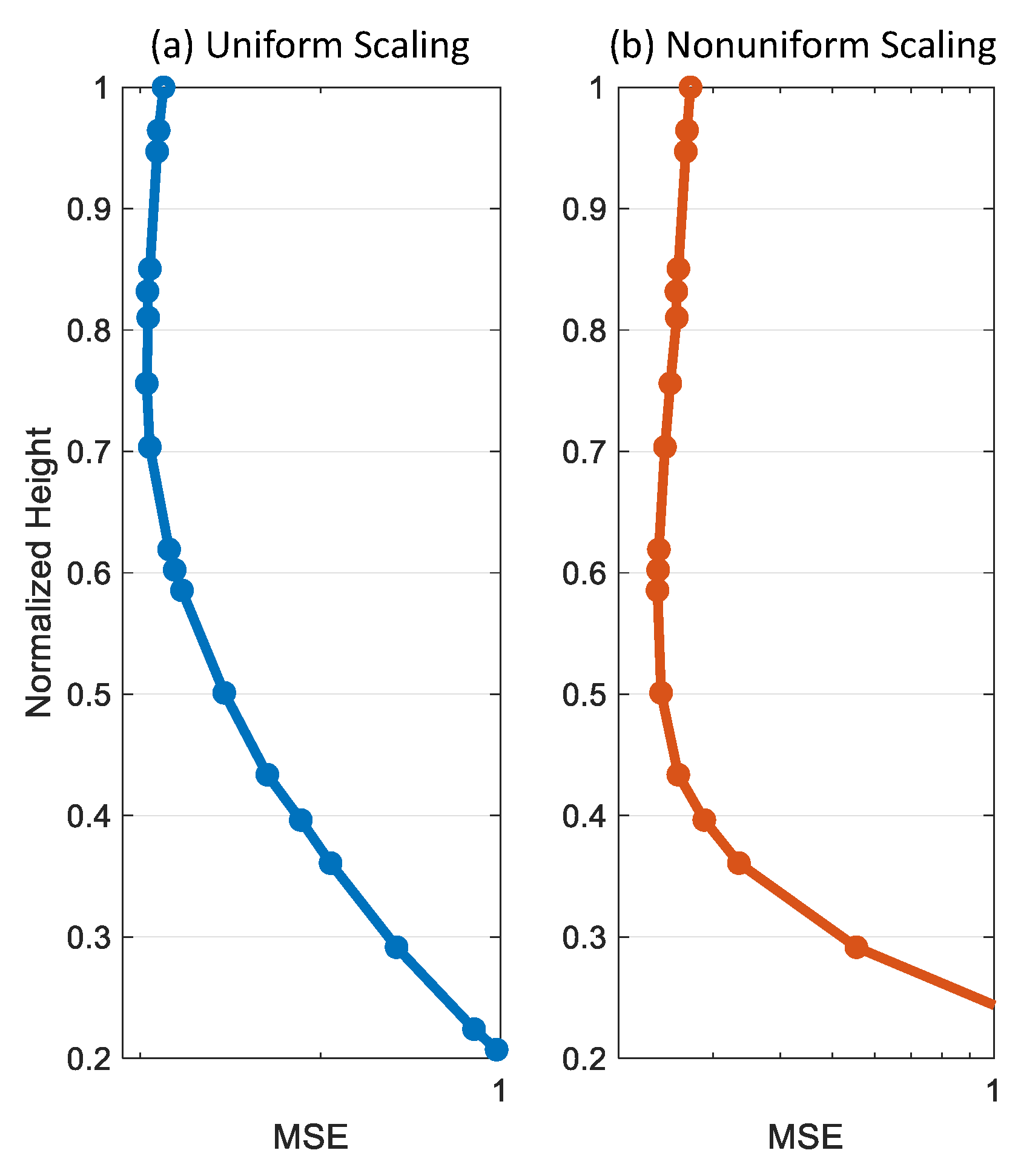

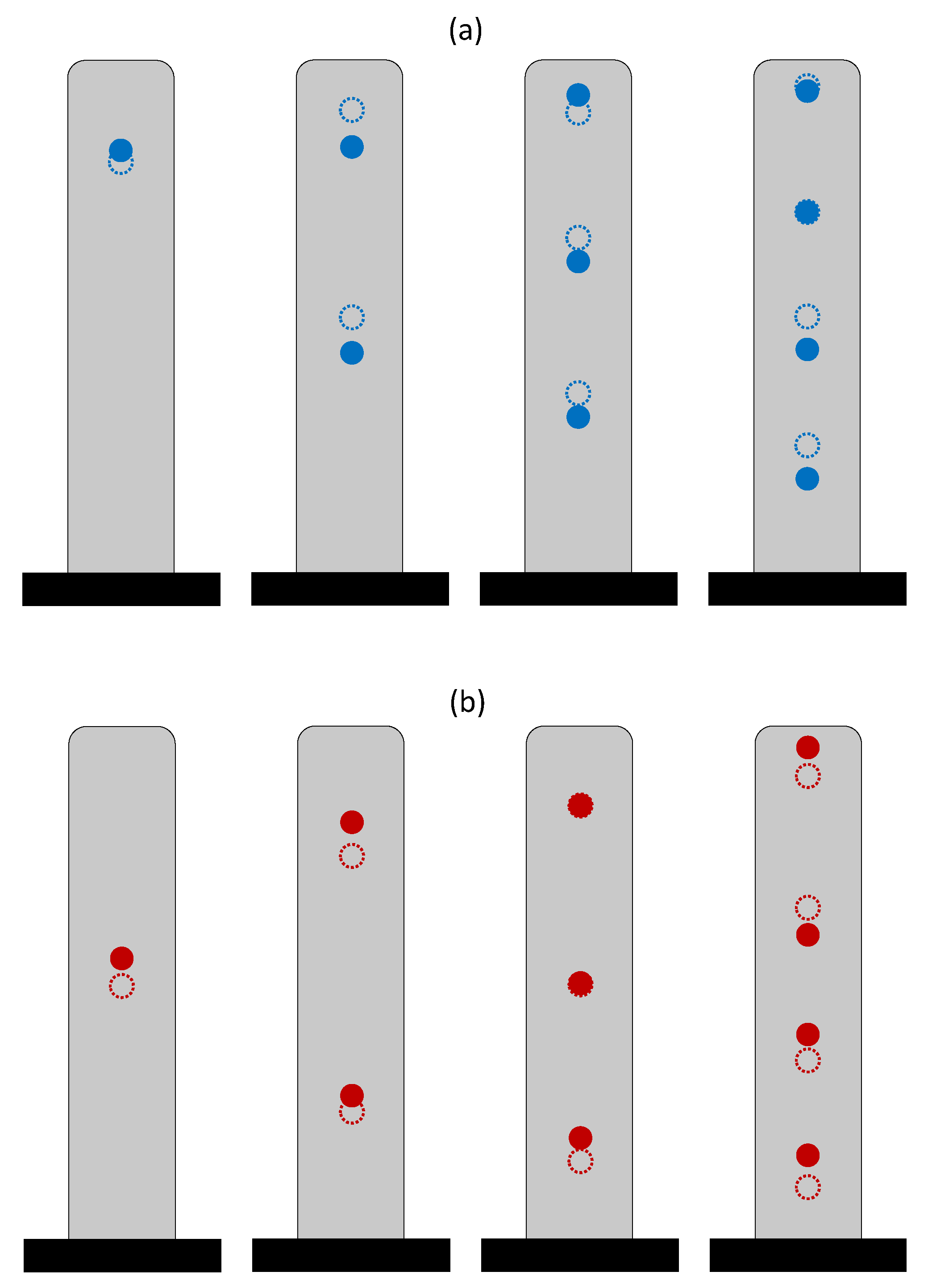

3.1. Single Sensor

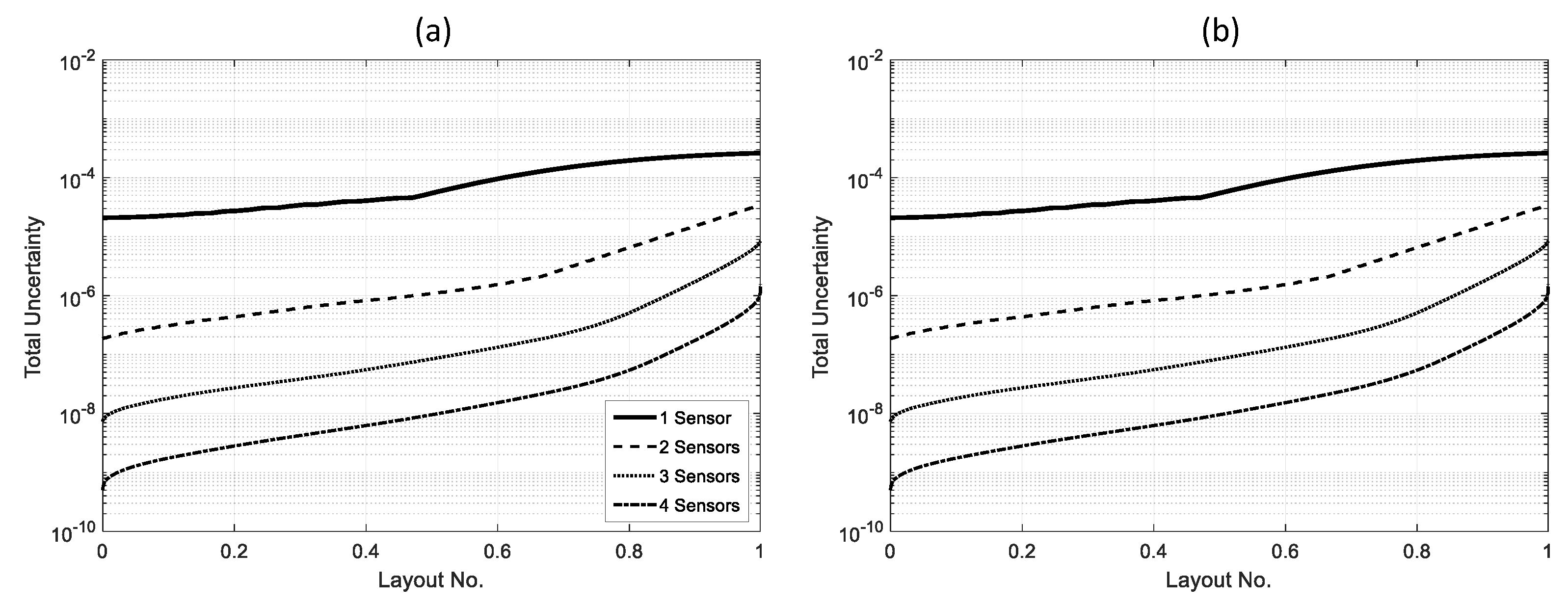

3.2. Multiple Sensors

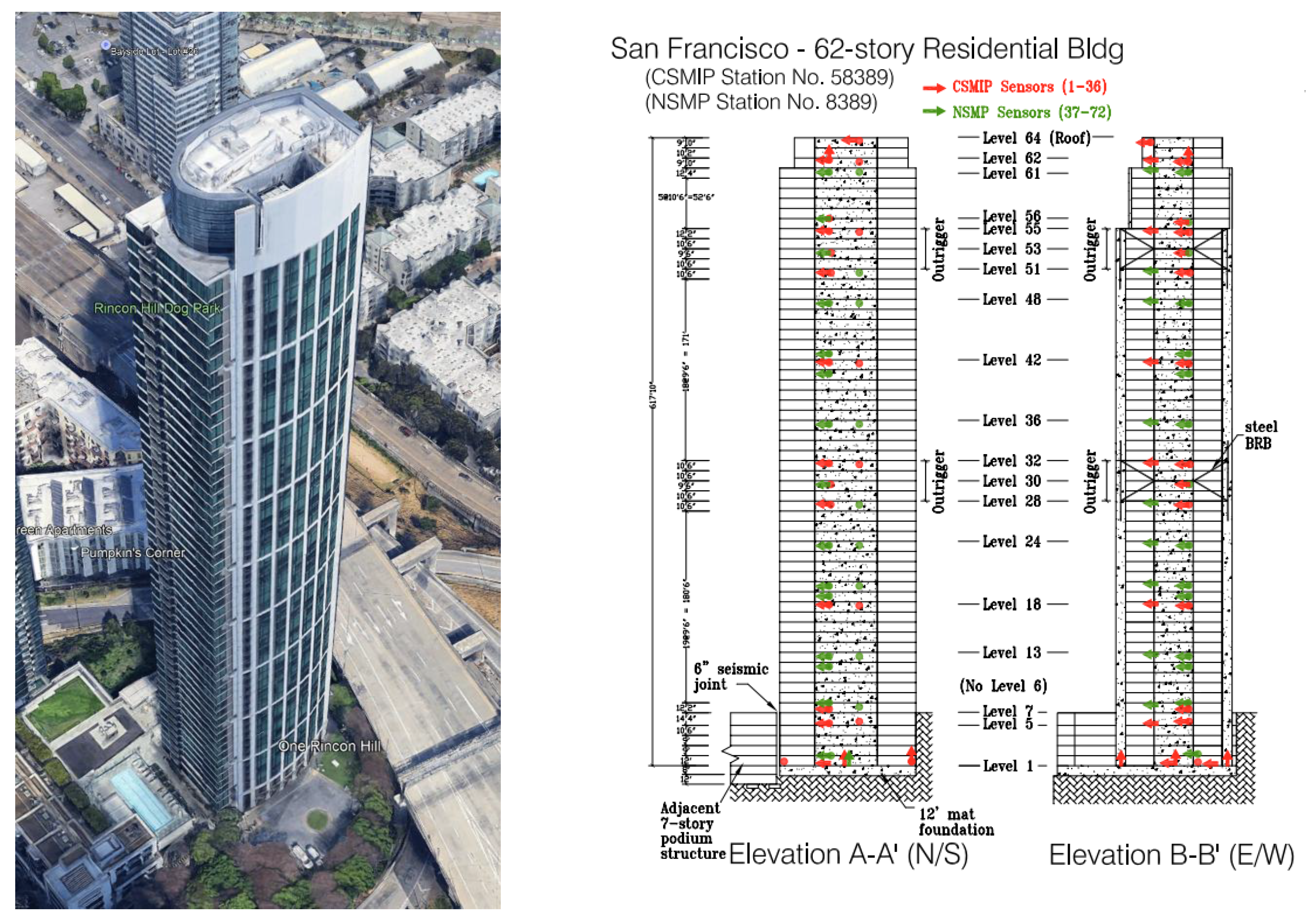

4. Validation

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Çelebi, M., Hisada. Responses of two tall buildings in Tokyo, Japan, before, during, and after the M9.0 Tohoku earthquake of 11 March 2011. Earthquake Spectra 2016, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, M., Kashima. Responses of a tall building with US code-type instrumentation in Tokyo, Japan, to events before, during, and after the Tohoku earthquake of 11 March 2011. Earthquake Spectra 2016, 32, 497–522. [Google Scholar]

- Çelebi, M., Kashima. Before and after retrofit behavior and performance of a 55-story tall building inferred from distant earthquake and ambient vibration data. Earthquake Spectra 2017, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, M., Ghahari. Response study of the tallest California building inferred from the Mw7.1 Ridgecrest, California earthquake of 5 July 2019 and ambient motions. Earthquake Spectra 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S.F., Abazarsa. Probabilistic blind identification of site effects from ground surface signals. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los Angeles Tall Buildings Structural Design Council (LATBSDC). An Alternative Procedure for Seismic Analysis and Design of Tall Buildings Located in the Los Angeles Region; LATBSDC: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Limongelli, M. P. , and Çelebi, M., 2019. Seismic Structural Health Monitoring. From Theory to Successful Applications. Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S.F., Malekghaini. Bridge digital twinning using an output-only Bayesian model updating method and recorded seismic Measurements. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, M., and Todorovska. Structural health monitoring of a 32-storey steel-frame building using 50 years of seismic monitoring data. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2021, 50, 1777–1800. [Google Scholar]

- Malekghaini, N., Ghahari. A two-step FE model updating approach for system and damage identification of prestressed bridge girders. Buildings 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazarsa, F., Ghahari. Response-only modal identification of structures using limited sensors. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2013, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazarsa, F., Nateghi. Blind modal identification of non-classically damped systems from free or ambient vibration records. Earthquake Spectra 2013, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazarsa, F., Nateghi. Extended blind modal identification technique for nonstationary excitations and its verification and validation. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 2016, 142, 04015078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S.F., Abazarsa. Response-only modal identification of structures using strong motion data. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S.F., Abazarsa. Blind modal identification of structures from spatially sparse seismic response signals. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2014, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S.F., Abazarsa. Blind modal identification of non-classically damped structures under non-stationary excitations. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friswell, M. I. , and Mottershead, J. E., 1995. Finite element model updating in structural dynamics. Solid mechanics and its applications. [CrossRef]

- Mottershead, J. E., Link. The sensitivity method in finite element model updating: A tutorial. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2011, 25, 2275–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, H., Taha. Estimation of soil–structure model parameters for the Millikan Library building using a sequential Bayesian Finite Element model updating technique. Buildings 2022, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, S.F., Abazarsa. Blind identification of the Millikan Library from earthquake data considering soil-structure interaction. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2016, 23, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, M., Hernandez. Nonlinear seismic response reconstruction and performance assessment of instrumented wood-frame buildings—Validation using NEESWood Capstone full-scale tests. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M., Astroza. Adaptive Kalman filters for nonlinear finite element model updating. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2020, 143, 106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J. P. , 2007. An overview of wireless structural health monitoring for civil structures. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q., Fei; et al. Influence of Sensor Density on Seismic Damage Assessment: A Case Study for Istanbul. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2022, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W., Fei; et al. Influence of accelerometer type on uncertainties in recorded ground motions and seismic damage assessment. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, G. Spline Models for Observational Data. Mathematics of Computation 1991, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeim, F., Lee. Three-dimensional analysis, real-time visualization, and automated post-earthquake damage assessment of buildings. Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings 2006, 15, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongelli, M. P. The interpolation damage detection method for frames under seismic excitation. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2011, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodera, K., Nishitani. Cubic spline interpolation based estimation of all story seismic responses with acceleration measurement at a limited number of floors. Japan Architectural Review 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, F., Swensen. A hybrid model-data method for seismic response reconstruction of instrumented buildings. Earthquake Spectra 2024, 40, 1235–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, E. Approximate seismic lateral deformation demands in multistory buildings. Journal of Structural Engineering 1999, 125, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, E., and Taghavi. S. \Approximate floor acceleration demands in multistory buildings. I: Formulation. Journal of structural engineering 2005, 131, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Taghavi, S., and Miranda. Approximate floor acceleration demands in multistory buildings. II: Applications. Journal of Structural Engineering 2005, 131, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzad-Ghaleroudkhani, N. , Mahsuli, M., Ghahari, S. F., and Taciroglu, E., 2017. Bayesian identification of soil-foundation stiffness of building structures. Structural Control and Health Monitoring. [CrossRef]

- Ameri Fard Nasrand, M. , Mahsuli, M., Ghahari, S.F., and Taciroglu, E., 2023. Bayesian model selection considering model complexity using stochastic filtering. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics, n/a(n/a). [CrossRef]

- Rostami, P., Mahsuli. Bayesian joint state-parameter-input estimation of flexible-base buildings from sparse measurements Using Timoshenko beam models. Journal of Structural Engineering 2021, 147, 04021151. [Google Scholar]

- Taciroglu, E., Çelebi. An investigation of soil-structure interaction effects observed at the MIT green building. Earthquake Spectra 2016, 32, 2425–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taciroglu, E., Ghahari. Efficient model updating of a multi-story frame and its foundation stiffness from earthquake records using a Timoshenko beam model. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2017, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krige, D. G. A statistical approach to some basic mine valuation problems on the Witwatersrand. Journal of Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 1951, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, C. E., and Williams. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tamhidi, A., Kuehn. Conditioned simulation of ground-motion time series at uninstrumented sites using Gaussian process regression. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2022, 112, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA P-58-1, 2018. Seismic performance assessment of buildings volume 1—methodology. Technical report FEMA-P58.

- Cremen, G. , and Baker, J. W., 2018. Quantifying the benefits of building instruments to FEMA P-58 rapid post-earthquake damage and loss predictions. Engineering Structures. [CrossRef]

- Morari, M., and O'Dowd. Optimal sensor location in the presence of nonstationary noise. Automatica 1980, 16, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammer, D. C. Sensor placement for on-orbit modal identification and correlation of large space structures. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 1991, 14, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F. Y., and Chiu. A near-optimal sensor placement algorithm to achieve complete coverage-discrimination in sensor networks. IEEE communications letters 2005, 9, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, D. L. Optimal network design for spatial prediction, covariance parameter estimation, and empirical prediction. Environmetrics: The official journal of the International Environmetrics Society 2006, 17, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, J., Chebira. Near-optimal sensor placement for linear inverse problems. IEEE Transactions on signal processing 2014, 62, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Mehr. Submodularity of optimal sensor placement for traffic networks. Transportation research part B: methodological 2023, 171, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udwadia, F. E. Methodology for optimum sensor locations for parameter identification in dynamic systems. Journal of engineering mechanics 1994, 120, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkegaard, P. H., and Brincker. On the optimal location of sensors for parametric identification of linear structural systems. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 1994, 8, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, C., Beck. Entropy-based optimal sensor location for structural model updating. Journal of Vibration and Control 2000, 6, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, C. Optimal sensor placement methodology for parametric identification of structural systems. Journal of sound and vibration 2004, 278, 923–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, C., Haralampidis. Optimal experimental design in stochastic structural dynamics. Probabilistic engineering mechanics 2005, 20, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C., Papadimitriou. Bayesian optimal sensor placement for modal identification of civil infrastructures. Journal of Smart Cities 2019, 2, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P., and Beck. Exploiting convexification for Bayesian optimal sensor placement by maximization of mutual information. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2020, 27, e2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C., Papadimitriou. A unified sampling-based framework for optimal sensor placement considering parameter and prediction inference. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2021, 161, 107950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongelli, M. P. Optimal location of sensors for reconstruction of seismic responses through spline function interpolation. Earthquake engineering & structural dynamics 2003, 32, 1055–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Bertola, N. J., Papadopoulou. Optimal multi-type sensor placement for structural identification by static-load testing. Sensors 2017, 17, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malings, C., and Pozzi. Value of information for spatially distributed systems: Application to sensor placement. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2016, 154, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, N. M., and Limongelli. Optimal Location of Strong Ground Motion Sensors for Seismic Emergency Management. In International Conference on Experimental Vibration Analysis for Civil Engineering Structures; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 582–591. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C., Chowdhury. Bayesian optimal sensor placement for crack identification in structures using strain measurements. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2018, 25, e2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capellari, G., Chatzi. Cost–benefit optimization of structural health monitoring sensor networks. Sensors 2018, 18, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodetsky, A., and Marzouk. Mercer kernels and integrated variance experimental design: connections between Gaussian process regression and polynomial approximation. SIAM/ASA Journal on Uncertainty Quantification 2016, 4, 796–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E., Speekenbrink. A tutorial on Gaussian process regression: Modelling, exploring, and exploiting functions. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 2018, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M. L. Interpolation of spatial data: some theory for kriging. Springer Science & Business Media. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahari, S.F., Sargsyan. Quantifying modeling uncertainty in simplified beam models for building response prediction. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2022, 29, e3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, R. W. , and Penzien, J., 2013. Dynamics of Structures. Dynamics of Structures. [CrossRef]

| Shear Wall/Braced Frame | Dual System | Moment Frame | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Sensors | Number of Sensors | Number of Sensors | ||||||||||

| Sensor Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0.80 (0.50) |

0.50 (0.25) |

0.35 (0.15) |

0.30 (0.1) |

0.75 (0.50) |

0.50 (0.25) |

0.35 (0.15) |

0.30 (0.1) |

0.70 (0.5) |

0.45 (0.25) |

0.30 (0.15) |

0.25 (0.1) |

| 2 | 0.9 (0.75) |

0.65 (0.50) |

0.50 (0.35) |

0.85 (0.75) |

0.65 (0.50) |

0.50 (0.35) |

0.85 (0.75) |

0.60 (0.50) |

0.50 (0.35) |

|||

| 3 | 0.90 (0.85) |

0.70 (0.65) |

0.90 (0.85) |

0.70 (0.65) |

0.90 (0.85) |

0.70 (0.65) |

||||||

| 4 | 0.95 (0.90) |

0.95 (0.90) |

0.95 (0.90) |

|||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).