1. Introduction

Tinnitus, characterized by the perception of sound in the absence of an external source, affects an estimated 10–15% of the adult population (Baguley, McFerran, & Hall, 2013). These phantom auditory sensations—including ringing, buzzing, and hissing—can vary in pitch, loudness, and location, and are often associated with cochlear damage or sensorineural hearing loss. However, accumulating evidence suggests that psychological distress, emotional reactivity, and attentional control also play significant roles in symptom severity and persistence (Langguth, Kreuzer, Kleinjung, & De Ridder, 2013; Kreuzer, Landgrebe, & Schecklmann, 2012). Recent models of tinnitus pathophysiology incorporate auditory deafferentation and central nervous system mechanisms, including altered limbic-auditory interactions and maladaptive plasticity (Rauschecker, Leaver, & Mühlau, 2010). More recently, studies have highlighted the strong interplay between tinnitus and mental health. Jiang et al. (2025), for example, demonstrated robust links between tinnitus severity and depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation, attributing these associations to altered limbic activity and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Such findings provide a neurobiological basis for the heightened emotional distress often reported by individuals with tinnitus.

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced new complexities into tinnitus management. Increasingly, reports have documented new onset or worsening of tinnitus following SARS-CoV-2 infection and, to a lesser extent, after COVID-19 vaccination (Beukes, Manchaiah, & Allen, 2021; Figueiredo et al., 2022; Taziki Balajelini et al., 2022). Hypothesized mechanisms include neuroinflammatory effects, endothelial dysfunction, and dysregulated immune responses, which may compromise auditory structures or central processing (Viola et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Pandemic-related psychosocial stress, isolation, and reduced access to hearing healthcare may also exacerbate tinnitus symptoms (Beukes, Baguley, Jacquemin, & Andersson, 2020; Yellamsetty & Gonzalez, 2024). Indeed, recent work emphasizes that stress may act as a potent trigger or amplifier of tinnitus through psychological and neurobiological pathways, rather than through direct alterations of auditory physiology (Maihoub, Mavrogeni, Répássy, & Molnár, 2025).

While anecdotal reports have linked both COVID-19 infection and vaccination to tinnitus onset, systematic investigations using validated instruments are limited. Tai, Jain, Kim, and Husain (2024) provided one of the most comprehensive examinations to date, showing that tinnitus burden is elevated across individuals reporting onset or worsening after COVID-19 infection, vaccination, or pandemic-related stress. These findings suggest that tinnitus in this context is not qualitatively distinct but reflects the broader patterns of emotional distress, functional impairment, and variability commonly observed in tinnitus populations. Prior studies have also underscored the importance of assessing functional hearing outcomes, including speech-in-noise perception and listening effort, which are often impaired in individuals with tinnitus (Moon et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2010).

The current study builds on this emerging literature by using standardized questionnaires—including the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI; Meikle et al., 2012), selected questions from the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI; Newman, Jacobson, & Spitzer, 1996), the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ; Gatehouse & Noble, 2004), and visual analog scales—to examine self-reported tinnitus severity and communication difficulties in individuals reporting tinnitus after COVID-19 vaccination. By situating these results within the broader context of pandemic-related stress and known tinnitus mechanisms, this study aims to characterize the perceptual, functional, and emotional consequences of tinnitus in this population and provide clinical insights into individualized assessment and management approaches.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey Design

A structured online survey was developed to characterize the experiences of individuals reporting tinnitus after COVID-19 vaccination. The survey included questions on demographics, vaccination history, tinnitus characteristics, medical and family history, and the impact of pandemic-related factors on auditory symptoms. Additional sections asked about prior audiological evaluations, imaging and laboratory testing, and tinnitus management strategies.

Validated measures were embedded within the survey to assess symptom severity and functional outcomes. These included the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI; Meikle et al., 2012)), selected items from the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI; Newman et al., 1996) and the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ; Wilson et al., 1991) visual analogue numeric rating scales for loudness discomfort and hyperacusis-related symptoms, and the 12-item Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ; Gatehouse & Noble, 2004) to evaluate perceived communication difficulties.

2.2. Data Collection

Data was collected in two phases. The first survey was administered through the University of Arizona between August and October 2021. Recruitment occurred via a Facebook support group (“Tinnitus and Hearing Loss/Impairment after COVID Vaccination”), where the survey link was shared publicly. The second phase took place at San José State University between December 2022 and May 2023, using a refined survey instrument that placed greater emphasis on vaccination timelines, medical and noise-exposure history, and perceptual changes in tinnitus.

Participation in both phases was voluntary, and electronic informed consent was obtained prior to the start of the survey. Eligibility criteria required that participants (1) confirm receipt of at least one COVID-19 vaccination, and (2) self-report either new-onset tinnitus or a worsening of pre-existing tinnitus temporally associated with vaccination. No control group was included (e.g., individuals with tinnitus unrelated to vaccination or tinnitus after COVID-19 infection), as the objective of this study was descriptive rather than comparative.

2.3. Data Cleaning

A total of 840 survey responses were collected across both phases. Of these, 46 incomplete responses were excluded, along with four duplicate entries and four responses deemed inaccurate or inconsistent. The final analytic sample consisted of 770 complete and valid responses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic, vaccination, and tinnitus-related variables. Group comparisons were conducted using chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent-sample t-tests for continuous variables. Correlation analyses were performed to explore associations among tinnitus severity, communication outcomes, and hyperacusis-related symptoms. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.3.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

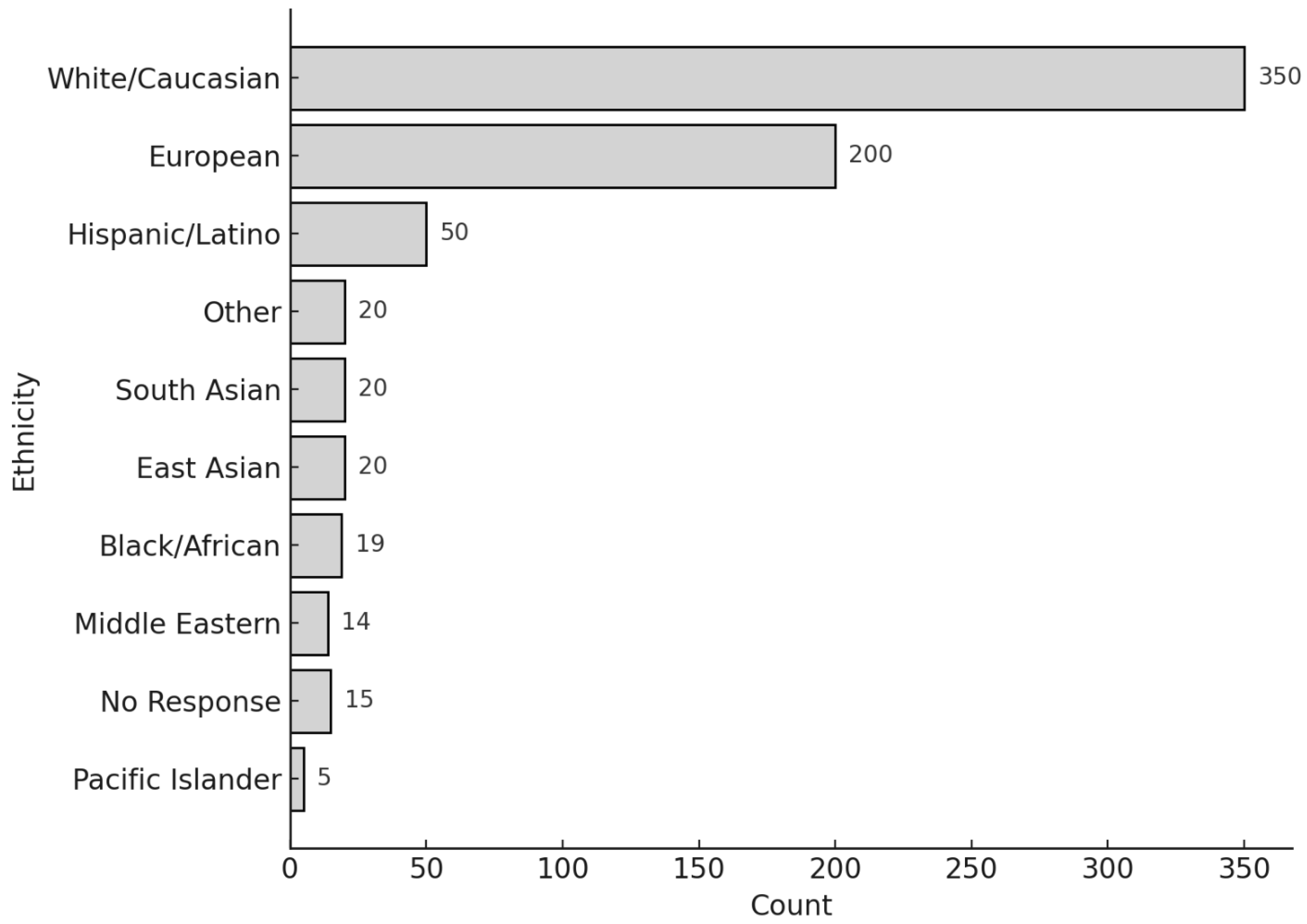

The average age of respondents was 54.7 years (SD = 14.4). Gender distribution included 450 females, 303 males, and 17 individuals who either selected “Other” or did not specify their gender. Respondents identified with the following ethnic backgrounds: White/Caucasian (356), European American (291), Hispanic/Latino (62), Black/African American (10), South Asian (21), East Asian (16), American Indian/Alaskan Native (8), Middle Eastern (8), Pacific Islander (1), Other (28), and No Response (2) (

Figure 1). Of the 770 respondents, 48 reported a COVID-19 infection, with only one hospitalization reported.

3.2. Vaccination Profiles

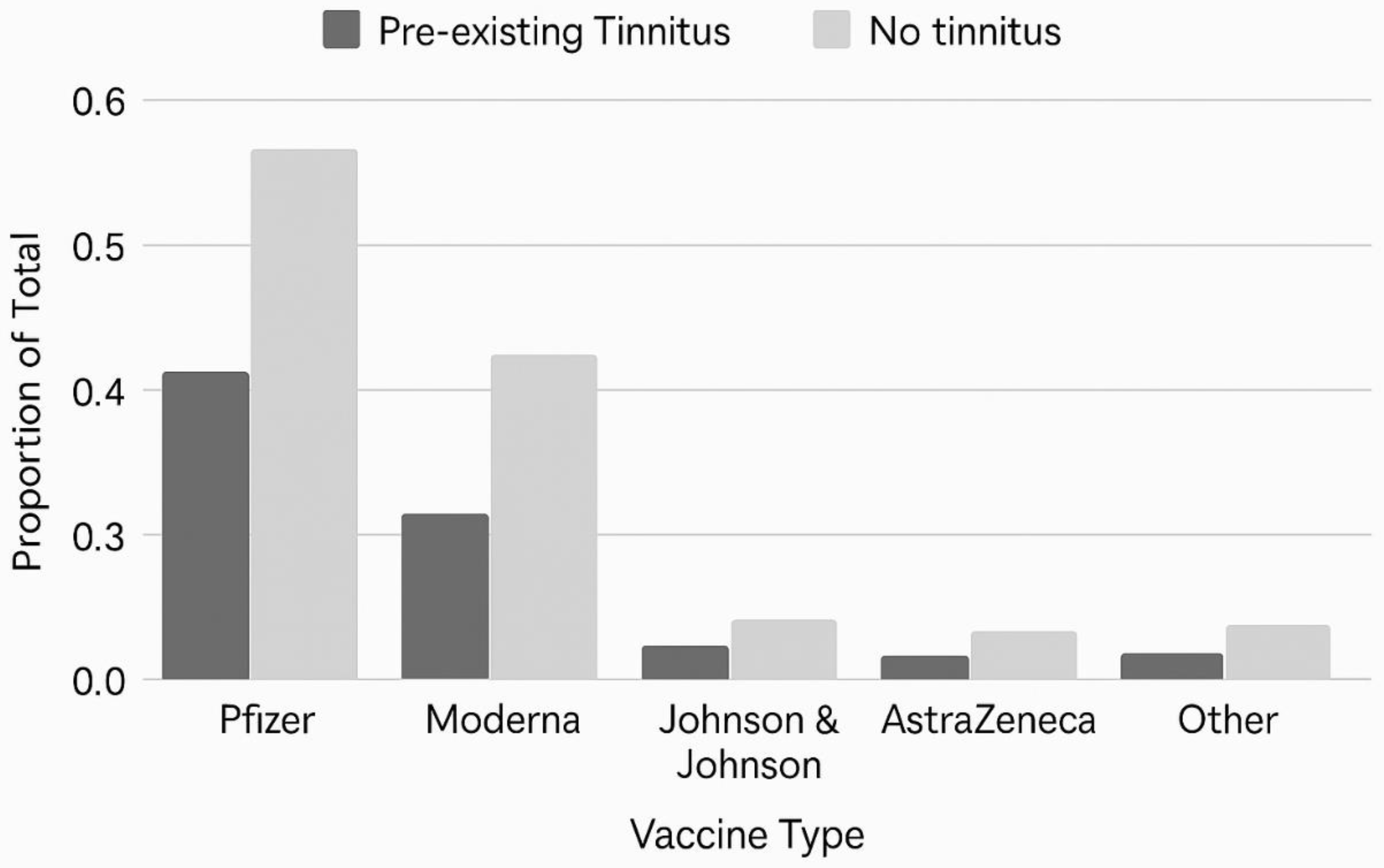

Table 1 outlines the distribution of vaccine types among all survey participants and specifically U.S.-based respondents. Pfizer was the most received vaccine, followed by Moderna.

Figure 2 displays the proportion of vaccine types received among individuals with and without pre-existing tinnitus. Across both groups, Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were the most frequently administered

. Participants without tinnitus were somewhat more likely to have received Pfizer (56% vs. 42%), while Moderna showed a similar though less pronounced pattern (43% vs. 32%). Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and other vaccines accounted for only a small proportion of the sample. Overall, the distribution of vaccine type appeared broadly similar across groups, with only modest differences

Table 2 summarizes the vaccine types, number of doses received, and presence of pre-existing tinnitus among respondents. These data help distinguish between new-onset tinnitus and cases where symptoms were potentially exacerbated post-vaccination.

3.3. Medical and Audiological Follow-Up

Of the 373 individuals who responded to this section, 224 reported undergoing follow-ups medical or hearing assessments (

Table 3). These included audiometric evaluations, ENT consultations, MRI and VNG testing, bloodwork, and specialist assessments in neurology and related fields. Audiometric evaluations were the most frequently reported.

3.3.1. Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI)

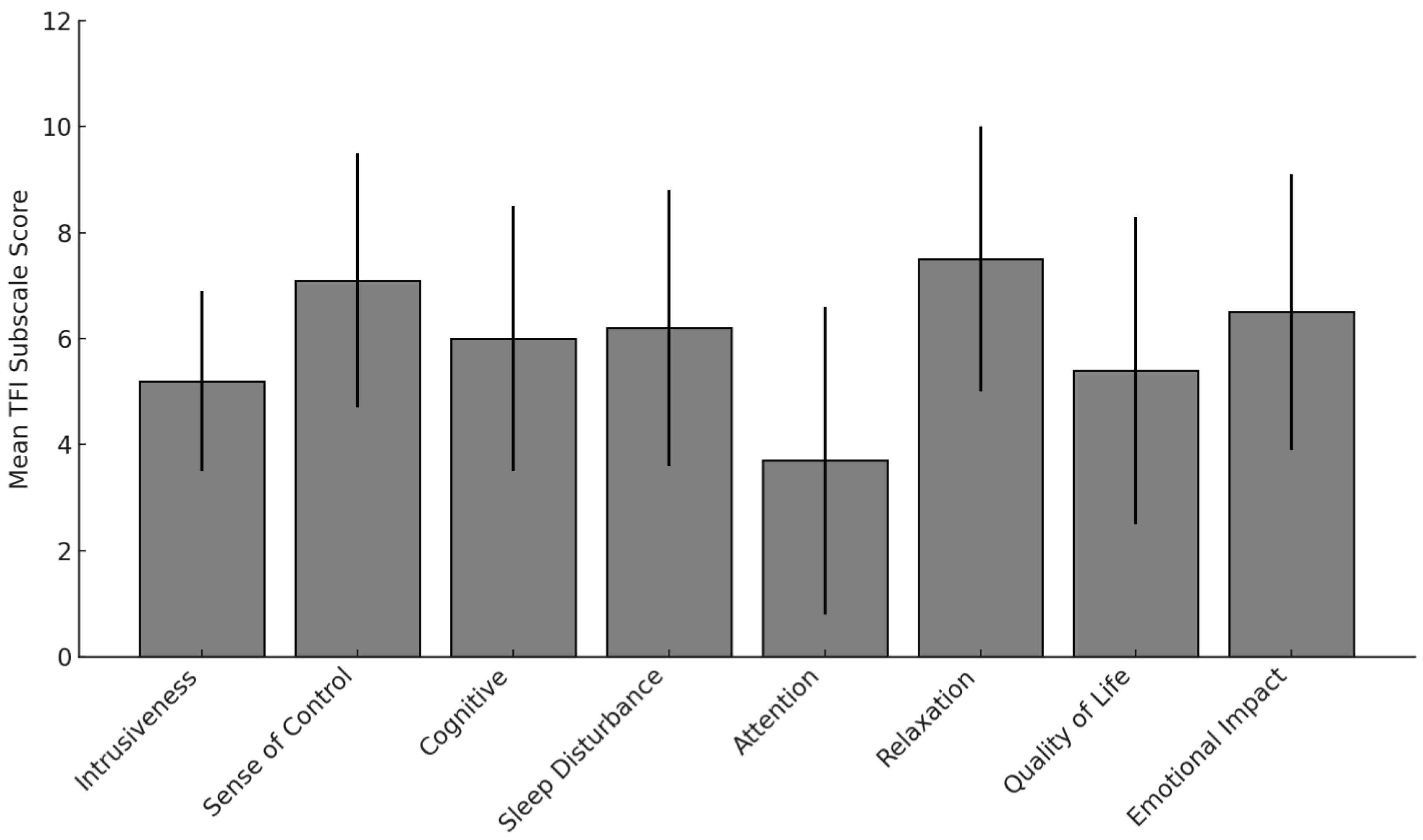

Responses to the TFI subscales revealed substantial tinnitus-related burden across multiple life domains (

Figure 3). The highest mean scores were observed for Relaxation (M ≈ 7.5), Sense of Control (M ≈ 7.2), and Emotional Impact (M ≈ 6.5). These findings indicate that tinnitus interfered most with emotional regulation, coping, and rest. Attention was rated lowest (M ≈ 3.7), although considerable individual variability was present. Other domains, including Sleep Disturbance, Cognitive effects, and Auditory-related difficulties, also showed moderate-to-high mean scores.

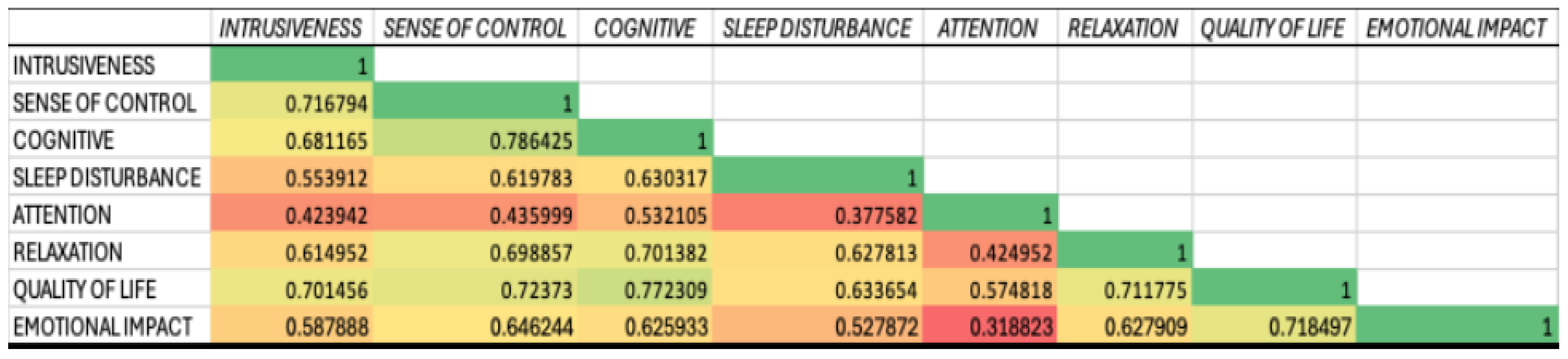

Pairwise correlations among the TFI subscales (

Figure 4) indicated strong positive associations across domains. For example, Relaxation was strongly associated with Sleep Disturbance (r = 0.77), Sense of Control (r = 0.72), and Emotional Impact (r = 0.71). Cognitive difficulties were also highly correlated with Emotional Impact (r = 0.77) and Quality of Life (r = 0.72). The weakest correlation was between Attention and Auditory (r = 0.32), though still statistically significant, suggesting that even less-related domains share variance.

3.3.2. Intrusiveness and Sense of Control

A substantial proportion of respondents reported constant awareness of tinnitus, with 35% perceiving it during 100% of waking hours. Loudness ratings were concentrated at the higher end of the scale, and many participants described minimal perceived control, with 30% indicating tinnitus was “impossible to ignore.”

3.3.2.1. Cognitive, Sleep, and Emotional Burden

Many respondents endorsed severe interference with concentration and clear thinking, as well as significant sleep disruption. More than one-third reported persistent anxiety, distress, or depressive symptoms linked to their tinnitus.

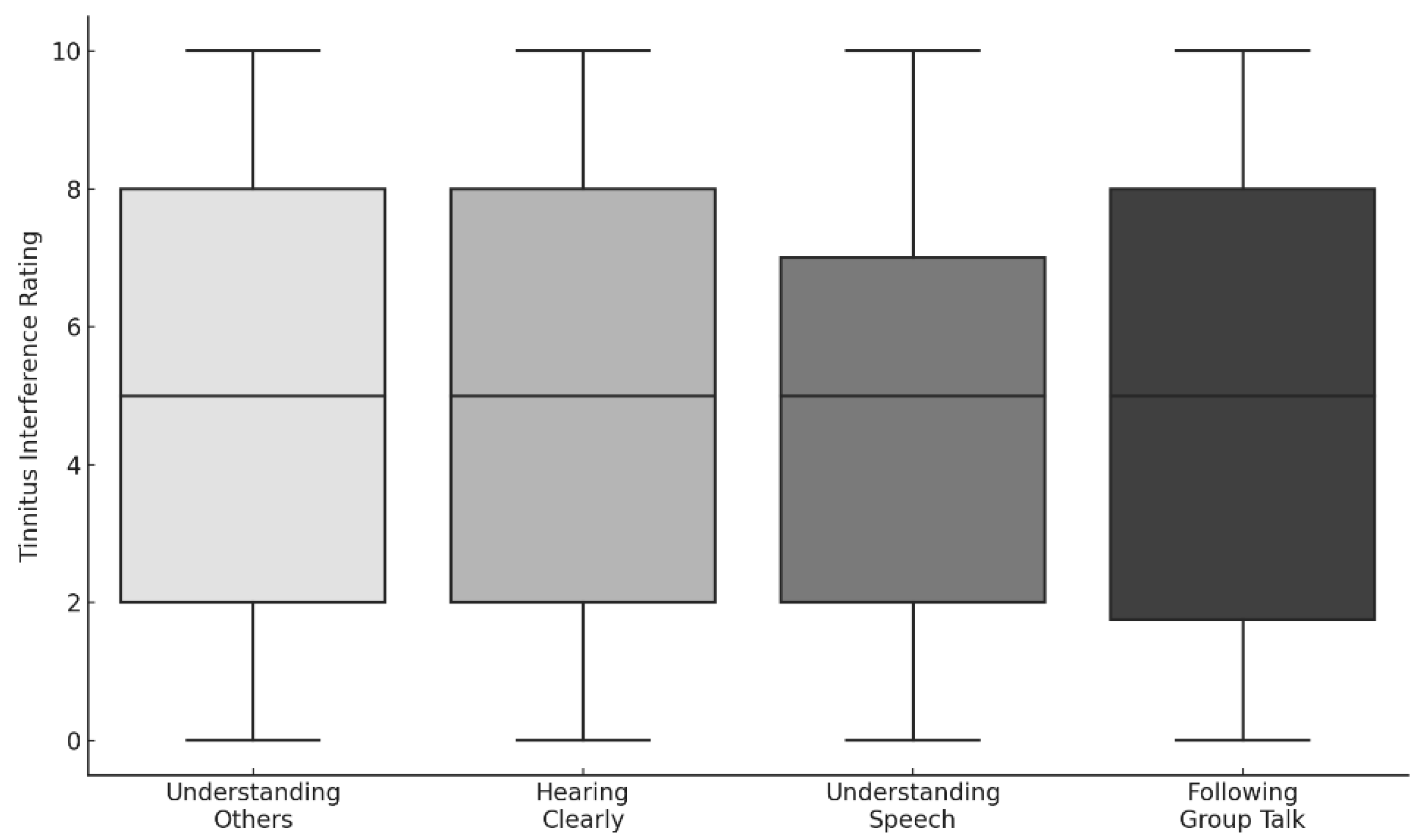

3.3.2.2. Auditory and Communication Interference

While many respondents reported preserved hearing clarity, difficulties were more pronounced in speech understanding and following group conversations. Interference ratings across communication domains were moderately elevated (median ≈ 5) and did not differ significantly across conditions (

Figure 5).

3.3.3. Hyperacusis and Loudness Sensitivity

Elevated sound sensitivity was commonly reported. Participants endorsed statements such as “moderately loud sounds are too loud” and “everyday sounds are painful,” consistent with hyperacusis-related symptoms (

Figure 6). Agreement ratings were broadly distributed, suggesting variability in sound tolerance, but no statistically significant differences were found across items.

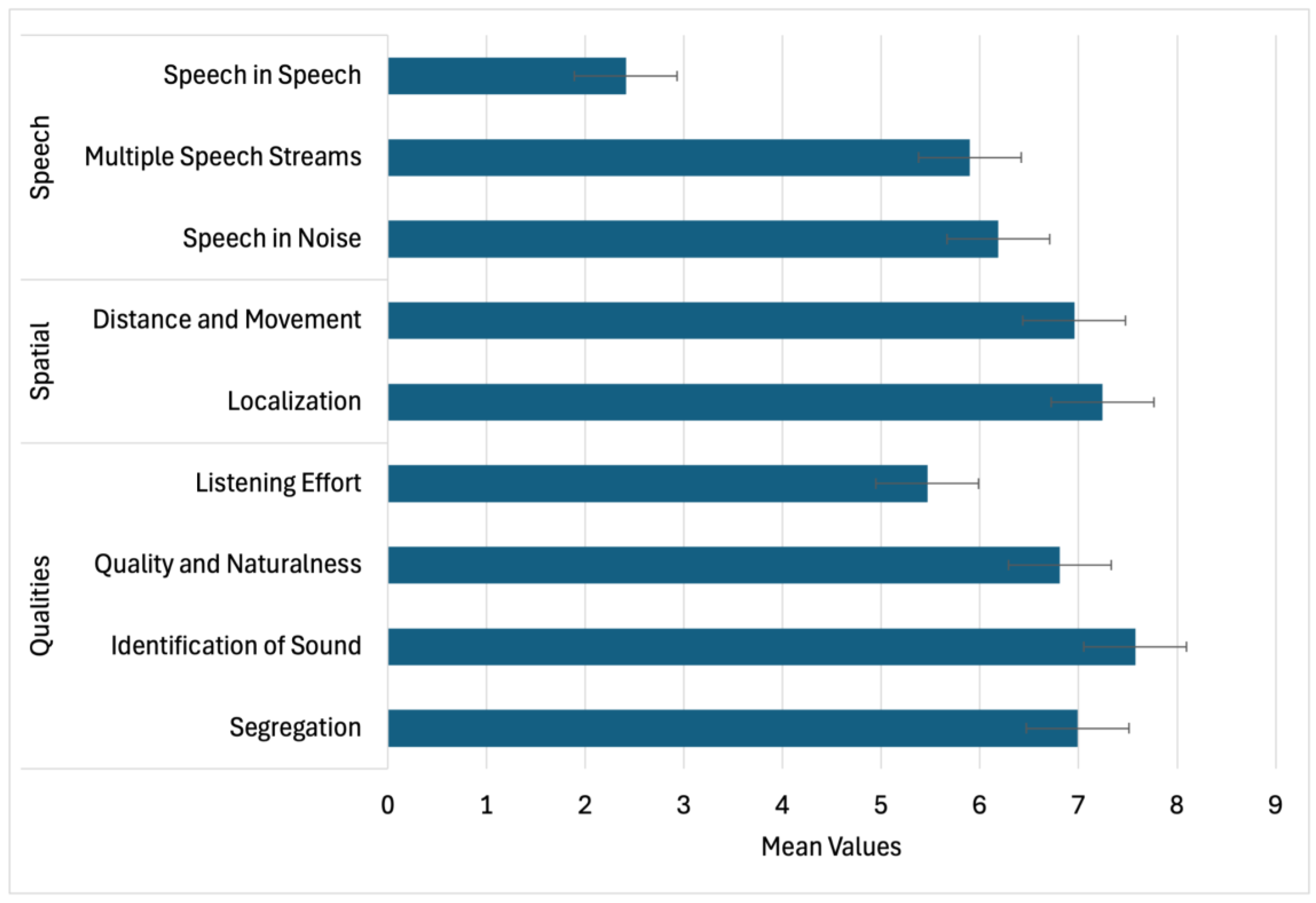

3.3.4. Functional Hearing Outcomes (SSQ)

SSQ ratings indicated challenges primarily in speech-related conditions (

Figure 7). The lowest ratings were observed for “Speech in Speech” (M ≈ 3.5) and other multi-talker or noisy environments (M ≈ 6.0). Spatial hearing (localization, distance, movement) was rated more favorably, with means above 7.0, while the Qualities domain was characterized by strong performance in sound identification and segregation but lower scores for listening effort (M ≈ 5.2). Item-level analyses confirmed significant clustering across domains (

Table 4). Strong intercorrelations were observed between Speech, Spatial, and Qualities domains (r = 0.73–0.81;

Table 5), underscoring the interconnected nature of functional hearing outcomes.

3.3.5. Loudness Ratings and Lateralization

On a visual analog scale, the most common rating for current tinnitus loudness was 6/10, while 24% reported a maximum loudness of 10/10 during their worst episode. Perceived location was most often the left ear (31.7%), followed by the center of the head (28.4%) and right ear (22.4%). A consistent left-ear predominance was observed for unilateral cases.

3.3.6. Contextualizing Symptom Burden

To situate these findings within the broader literature, participants’ mean TFI Sense of Control scores (M = 7.2) were substantially higher than typical values reported in non-tinnitus control groups (M ≈ 1.5–2.0; Meikle et al., 2012). Similarly, SSQ Speech and Spatial scores (M ≈ 6.0–7.0) were lower than normative scores for adults with normal hearing (M ≈ 8.5–9.0; Gatehouse & Noble, 2004). These comparisons suggest that, while the experiences reported in this study align with challenges commonly described by individuals with bothersome tinnitus, the symptom burden in this subgroup is clinically meaningful and warrants careful evaluation.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of COVID-19 infection and vaccination on tinnitus, focusing on self-reported changes in perceptual features (e.g., loudness, pitch, location), emotional and cognitive functioning, and speech-in-noise perception. Utilizing validated instruments including the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI), Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ), and visual analog rating scales, the study offers a comprehensive profile of tinnitus burden in the context of the pandemic. Key findings include elevated distress in TFI subdomains such as Relaxation and Emotional Impact, consistent left-ear lateralization, reports of worsened tinnitus following vaccination, and increased listening effort in noisy environments. Additionally, high correlations between SSQ domains suggest interconnected auditory processing difficulties.

These findings align with an expanding body of post-pandemic research emphasizing perceptual variability, emotional comorbidity, and auditory sensitivity in individuals with tinnitus. Yellamsetty (2023) documented increases in tinnitus loudness and hyperacusis following COVID-19 vaccination, while Yellamsetty and Gonzalez (2024) highlighted pandemic-related psychosocial stressors as exacerbating factors. Bao et al. (2024) identified pre-vaccination metabolic vulnerabilities that may predispose individuals to auditory disturbances. A comprehensive survey by Yellamsetty, Egbe-Etu, and Bao (2024) confirmed symptom heterogeneity across a large cohort. These patterns echo findings from Beukes et al. (2020, 2021), who described worsened tinnitus severity, emotional distress, and disrupted healthcare access during the pandemic, and from Taziki Balajelini et al. (2022) and Figueiredo et al. (2022), who reported variable tinnitus outcomes following vaccination. Importantly, Tai et al. (2024) provided a systematic investigation of tinnitus in relation to COVID-19 infection, vaccination, and pandemic stress, concluding that tinnitus burden is elevated across these groups and not limited to one etiology. The present findings extend this literature by characterizing a large sample of individuals attributing tinnitus onset or exacerbation specifically to vaccination, while recognizing that the symptom burden is consistent with that seen in tinnitus more broadly.

4.1. Tinnitus-Related Impairments Across Functional Domains

The TFI results underscore the multidimensional nature of tinnitus-related distress, with the greatest impact in Relaxation, Emotional Distress, and Sense of Control. A substantial proportion of participants reported constant awareness, high loudness ratings, and persistent annoyance, consistent with previous work showing the close association between tinnitus severity and psychological comorbidities (Langguth et al., 2013; Hiller & Goebel, 2006). Reduced sense of control and difficulty ignoring tinnitus reinforce the interplay between perceptual and emotional domains, while sleep disturbance and cognitive interference—well-established correlates of tinnitus (Meikle et al., 2012)—were also frequently endorsed.

While some participants reported little disruption in hearing clarity, qualitative and quantitative data highlighted difficulties with group communication and speech understanding, consistent with reports of listening fatigue in complex environments. These findings parallel more recent pandemic-era research documenting heightened distress, reduced access to care, and increased auditory sensitivity as contributors to worsened tinnitus outcomes (Beukes et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2022). Collectively, the results support prior literature while adding descriptive evidence from individuals reporting post-vaccination tinnitus.

Moreover, our results contribute to the growing body of literature identifying strong associations between tinnitus and mental health challenges, particularly during global crises. Jiang et al. (2025) recently demonstrated robust links between tinnitus severity and depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation. Their findings of altered limbic activity and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation provide a plausible neurobiological basis for the sustained increases in tinnitus distress observed in our cohort. Recent work by Maihoub et al. (2025) further emphasizes that pandemic-related stress can act as a potent trigger or amplifier of tinnitus through psychological and neurobiological pathways, rather than through direct alterations of peripheral auditory physiology. These insights resonate with our findings of heightened emotional impact and sense-of-control difficulties, suggesting that stress-mediated mechanisms may play a significant role in shaping tinnitus burden during and after the pandemic.

Compared to prior investigations that have primarily examined tinnitus linked to COVID-19 infection (e.g., Beukes et al., 2021; Viola et al., 2022) or vaccination in isolation (e.g., Formeister et al., 2022; Yellamsetty et al., 2023), the present study contributes by using validated instruments (THI, TRQ, TFI, SSQ) to capture tinnitus severity and functional impact across multiple pandemic-related contexts. This design provides a broader perspective on both psychosocial and vaccine-related influences, enabling a more comprehensive characterization of tinnitus trajectories. This divergence underscores the need for future research to disentangle stress-mediated mechanisms from peripheral auditory effects when examining tinnitus during and after the pandemic.

4.2. Speech Perception and Listening Effort in Complex Environments

SSQ results indicated that spatial hearing abilities (e.g., localization, distance estimation) were largely preserved, while speech-in-noise and multi-talker conditions were rated as particularly challenging. Elevated listening effort was consistently endorsed, reflecting the increased cognitive load required to maintain communication. These findings mirror established evidence that tinnitus is associated with greater attentional demand and reduced efficiency in auditory scene analysis (Moon et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2010; Noreña, 2011).

Hyperacusis-related symptoms also emerged, with participants reporting excessive loudness, annoyance, and in some cases fear or pain in response to everyday sounds. These results are consistent with previous findings of increased sound sensitivity among individuals with tinnitus (Tyler et al., 2014; Taziki Balajelini et al., 2022; Yellamsetty et al., 2024). The strong correlations among SSQ domains reinforce that these functional communication difficulties are interconnected and likely reflect shared perceptual and cognitive mechanisms, a conclusion also supported by Beukes et al. (2021).

4.3. Perceived Loudness and Lateralization

Self-reported tinnitus loudness revealed a bimodal distribution, with moderate loudness commonly reported during daily life and extreme loudness endorsed by nearly one-quarter of respondents at its worst. This may suggest partial adaptation over time, though residual burden remained high. Lateralization patterns showed a consistent left-ear predominance, consistent with previous clinical and neuroimaging studies implicating hemispheric auditory asymmetries. The high proportion of reports of centralized or diffuse tinnitus highlights the need for careful characterization of perceptual localization in both clinical and research contexts.

4.4. Pandemic-Related Factors and Post-Vaccination Reports

A subset of respondents described changes in tinnitus characteristics—such as increased loudness, pitch, and emotional reactivity—following vaccination, often accompanied by communication difficulties and sound sensitivity. Similar reports have been documented in observational studies (Beukes et al., 2021; Figueiredo et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022). Taziki Balajelini et al. (2022) also noted increased hyperacusis, sound intolerance, and tinnitus loudness in both healthcare workers and community samples after vaccination.

The present findings converge with Tai et al. (2024), who emphasized that tinnitus burden is heightened not only after vaccination, but also after infection and in association with pandemic-related stress. Taken together, these studies suggest that while specific mechanisms remain uncertain, immune response, neuroinflammation, psychosocial stress, and pre-existing vulnerabilities may all contribute to tinnitus exacerbation in this context.

4.5. Clinical and Research Implications

This study reinforces the need for multidimensional assessment of tinnitus, incorporating both symptom severity and functional communication outcomes. Tools such as the TFI and SSQ are valuable for capturing the emotional, perceptual, and cognitive consequences of tinnitus. Clinically, audiologists should integrate counseling and cognitive support, as psychological distress and attentional mechanisms strongly influence patient experiences. From a research perspective, the findings highlight the importance of including control groups and longitudinal follow-up in future studies to better delineate whether tinnitus associated with vaccination differs from tinnitus triggered by infection or pandemic stress, as emphasized by Tai et al. (2024).

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The study relied on self-reported data, with no objective audiometric verification. Recruitment through online surveys and support groups introduces potential selection bias. Most importantly, the study did not include a control group (e.g., individuals with tinnitus unrelated to vaccination or those developing tinnitus after infection), limiting the ability to establish whether findings are specific to post-vaccination tinnitus or reflective of broader tinnitus populations.

Nonetheless, the large sample size and use of validated measures strengthen the descriptive value of the results. Future work should incorporate longitudinal designs, biological and neuroimaging markers, and comparison groups to clarify mechanisms. Integrating insights from Tai et al. (2024) and others, future research should aim to disentangle the relative contributions of infection, vaccination, and psychosocial stress to tinnitus burden.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing literature documenting the multidimensional burden of tinnitus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals reporting tinnitus after vaccination described emotional distress, cognitive interference, sleep disruption, and communication difficulties—findings consistent with bothersome tinnitus populations more generally (Langguth et al., 2013; Beukes et al., 2021; Tai et al., 2024). While causality cannot be inferred, the results underscore the importance of comprehensive clinical evaluation and patient-centered care, and they highlight the need for future controlled, longitudinal studies to better understand risk factors and mechanisms.

Declaration of the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Manuscript Preparation

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-4), were utilized during the preparation of this manuscript to assist with language editing, grammar refinement, and organization of scientific text. The use of AI was limited to enhancing readability and did not involve the generation of original scientific ideas, data analysis, or interpretation of findings. All content was critically reviewed, revised, and approved by the authors to ensure scientific integrity and compliance with ethical publication standards.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

None.

Ethics Statement

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) in compliance with ethical guidelines at San Jose State University (22177) on 17 August 2022 and University of Arizona (2106965138) on 22 July 2026.

References

- Baguley, D., McFerran, D., & Hall, D. (2013). Tinnitus. The Lancet, 382(9904), 1600–1607. [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E. W., Manchaiah, V., & Allen, P. M. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 and the associated restrictions on people with pre-existing chronic tinnitus. International Journal of Audiology, 60(9), 707–714. [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E. W., Baguley, D. M., Jacquemin, L., & Andersson, G. (2020). Changes in tinnitus experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 592878. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, R. R., Azevedo, A. A., de Oliveira Penido, N., & Canto, G. (2022). Tinnitus and COVID-19: An overview of preexisting evidence and perspectives for future research. Journal of Otology, 17(2), 77–82. [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse, S., & Noble, W. (2004). The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). International Journal of Audiology, 43(2), 85–99. [CrossRef]

- Hiller, W., & Goebel, G. (2006). Factors influencing tinnitus loudness and annoyance. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 132(12), 1323–1330. [CrossRef]

- Langguth, B., Kreuzer, P. M., Kleinjung, T., & De Ridder, D. (2013). Tinnitus: Causes and clinical management. The Lancet Neurology, 12(9), 920–930. [CrossRef]

- Maihoub, S., Mavrogeni, P., Molnár, V., & Molnár, A. (2025). Tinnitus and its comorbidities: a comprehensive analysis of their relationships. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(4), 1285. [CrossRef]

- Maihoub, S., Mavrogeni, P., Répássy, G. D., & Molnár, A. (2025). Exploring how blood cell levels influence subjective tinnitus: A cross-sectional case-control study. Audiology Research, 15(3), 72. [CrossRef]

- Meikle, M. B., Henry, J. A., Griest, S. E., Stewart, B. J., Abrams, H. B., McArdle, R.,... & Vernon, J. A. (2012). The tinnitus functional index: Development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear and Hearing, 33(2), 153–176. [CrossRef]

- Moon, I. J., Shim, H. J., Park, H. J., Jung, J. Y., Lee, S. H., & Lee, W. S. (2015). Tinnitus and speech perception in noise: The role of hearing loss and cognition. Journal of Audiology & Otology, 19(2), 82–87. [CrossRef]

- Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 122(2), 143–148.

- Noreña, A. J. (2011). An integrative model of tinnitus based on a central gain controlling neural sensitivity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(5), 1089–1109. [CrossRef]

- Rauschecker, J. P., Leaver, A. M., & Mühlau, M. (2010). Tuning out the noise: Limbic-auditory interactions in tinnitus. Neuron, 66(6), 819–826. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L. E., Eggermont, J. J., Caspary, D. M., Shore, S. E., Melcher, J. R., & Kaltenbach, J. A. (2010). Ringing ears: The neuroscience of tinnitus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30(45), 14972–14979. [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y., Jain, N., Kim, G., & Husain, F. T. (2024). Tinnitus and COVID-19: Effect of infection, vaccination, and the pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1508607. [CrossRef]

- Tan, B. K. J., Ng, J. Y., & Puvanendran, R. (2022). Post-COVID-19 tinnitus: A review. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 43(5), 103418. [CrossRef]

- Taziki Balajelini, M., Sadoughi, M., & Mirzaei, M. (2022). Evaluation of tinnitus prevalence and characteristics in healthcare workers after COVID-19 vaccination. Noise & Health, 24(115), 17–22. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R. S., Pienkowski, M., Roncancio, E. R., Jun, H. J., Brozoski, T., Dauman, N.,... & Moore, B. C. J. (2014). A review of hyperacusis and future directions: Part I. Definitions and manifestations. American Journal of Audiology, 23(4), 402–419. [CrossRef]

- Viola, P., Ralli, M., Pisani, D., & Petrucci, A. G. (2021). Tinnitus and equilibrium disorders in COVID-19 patients: Preliminary results. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 278(10), 3725–3730. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Zhou, Y., Lin, H., & Ma, X. (2022). A review of SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccine-associated otologic symptoms. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 928099. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Yellamsetty, A., Edmonds, R. M., Barcavage, S. R., & Bao, S. (2024). COVID-19 vaccination-related tinnitus is associated with pre-vaccination metabolic disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P. H., Henry, J., Bowen, M., & Haralambous, G. (1991). Tinnitus reaction questionnaire: psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34(1), 197–201.

- Yellamsetty, A. (2023). COVID-19 vaccination effects on tinnitus and hyperacusis: Longitudinal case study. The International Tinnitus Journal, 27(2), 253–258. [CrossRef]

- Yellamsetty, A., & Gonzalez, V. (2024). Understanding COVID-19-related tinnitus: Emerging evidence and implications. Tinnitus Today.

- Yellamsetty, A., Egbe-Etu, E., & Bao, S. (2024). Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on tinnitus onset and severity: A comprehensive survey study. Frontiers in Audiology and Otology, 3, 1509444. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution of self-reported ethnicity among study participants (N = 770). The majority identified as White/Caucasian or European American. Bar heights indicate the number of respondents per category, highlighting the ethnic composition of the study sample.

Figure 1.

Distribution of self-reported ethnicity among study participants (N = 770). The majority identified as White/Caucasian or European American. Bar heights indicate the number of respondents per category, highlighting the ethnic composition of the study sample.

Figure 2.

Distribution of COVID-19 vaccine types among individuals with and without pre-existing tinnitus. Each bar shows the number of participants receiving a given vaccine type, segmented by tinnitus status. Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were most commonly received across both groups.

Figure 2.

Distribution of COVID-19 vaccine types among individuals with and without pre-existing tinnitus. Each bar shows the number of participants receiving a given vaccine type, segmented by tinnitus status. Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were most commonly received across both groups.

Figure 3.

Mean values (± standard deviation) for each of the eight subscales of the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI). Higher scores indicate greater perceived tinnitus-related burden. The highest average scores were observed in the domains of Relaxation, Sense of Control, and Emotional Impact, while Attention showed the lowest average rating.

Figure 3.

Mean values (± standard deviation) for each of the eight subscales of the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI). Higher scores indicate greater perceived tinnitus-related burden. The highest average scores were observed in the domains of Relaxation, Sense of Control, and Emotional Impact, while Attention showed the lowest average rating.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix of Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) subscales. Each cell represents the Pearson correlation coefficient between two subscales, with stronger correlations indicated by darker shading. High correlations were observed among Emotional Impact, Sleep, and Relaxation.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix of Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) subscales. Each cell represents the Pearson correlation coefficient between two subscales, with stronger correlations indicated by darker shading. High correlations were observed among Emotional Impact, Sleep, and Relaxation.

Figure 5.

Boxplots depicting self-reported tinnitus interference ratings (scale: 0 = no interference to 10 = extreme interference) across four communication domains: understanding others, hearing clearly, understanding speech, and following group talk. Median interference levels were comparable across all domains.

Figure 5.

Boxplots depicting self-reported tinnitus interference ratings (scale: 0 = no interference to 10 = extreme interference) across four communication domains: understanding others, hearing clearly, understanding speech, and following group talk. Median interference levels were comparable across all domains.

Figure 6.

Boxplots of self-reported agreement ratings (0–10) across four perceptual domains related to sound tolerance among individuals reporting tinnitus after COVID-19 vaccination. Participants responded to whether moderately loud sounds were perceived as too loud, annoying, fear-inducing, or painful. Median agreement was highest for “Too Loud” and “Annoying.”.

Figure 6.

Boxplots of self-reported agreement ratings (0–10) across four perceptual domains related to sound tolerance among individuals reporting tinnitus after COVID-19 vaccination. Participants responded to whether moderately loud sounds were perceived as too loud, annoying, fear-inducing, or painful. Median agreement was highest for “Too Loud” and “Annoying.”.

Figure 7.

Mean ratings (± standard deviation) for the Speech, Spatial, and Qualities subdomains of the Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). Participants reported the lowest average performance in the Speech domain, particularly under multi-talker conditions.

Figure 7.

Mean ratings (± standard deviation) for the Speech, Spatial, and Qualities subdomains of the Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). Participants reported the lowest average performance in the Speech domain, particularly under multi-talker conditions.

Table 1.

Frequency and distribution of tinnitus cases across vaccine manufacturers. Includes total responses and U.S.-based cases. Pfizer and Moderna were the most common vaccines received among participants.

Table 1.

Frequency and distribution of tinnitus cases across vaccine manufacturers. Includes total responses and U.S.-based cases. Pfizer and Moderna were the most common vaccines received among participants.

| Vaccine Manufacturer |

All Survey Cases |

U.S. Survey Cases |

| Pfizer |

427 |

328 |

| Moderna |

256 |

239 |

| Johnson & Johnson |

55 |

48 |

| AstraZeneca |

28 |

2 |

| Other |

4 |

1 |

Table 2.

Dose series by vaccine manufacturer and pre-existing tinnitus. Includes the number of participants who received 1, 2, 3, or 4+ doses for each manufacturer, with a breakdown by pre-existing tinnitus status.

Table 2.

Dose series by vaccine manufacturer and pre-existing tinnitus. Includes the number of participants who received 1, 2, 3, or 4+ doses for each manufacturer, with a breakdown by pre-existing tinnitus status.

| Vaccine Manufacturer |

1 Dose |

2 Doses |

3 Doses |

4+ Doses |

Total Cases |

Pre-existing Tinnitus (n) |

| Pfizer |

16 |

187 |

177 |

47 |

427 |

113 |

| Moderna |

7 |

94 |

122 |

33 |

256 |

67 |

| Johnson & Johnson |

31 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

55 |

17 |

| AstraZeneca |

18 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

28 |

4 |

Table 3.

Medical evaluations following tinnitus onset. Includes frequencies of audiological and neurological assessments among 373 participants, segmented by gender where available.

Table 3.

Medical evaluations following tinnitus onset. Includes frequencies of audiological and neurological assessments among 373 participants, segmented by gender where available.

| Type of Evaluation |

Total (n=373) |

Male (n=162) |

Female (n=199) |

Other/Unspecified (n=12) |

| Audiometric Testing |

161 |

73 |

85 |

3 |

| ENT Consultation |

105 |

52 |

50 |

3 |

| MRI |

89 |

40 |

46 |

3 |

| Blood Tests |

54 |

26 |

27 |

1 |

| Vestibular (VNG, Balance) Tests |

27 |

12 |

14 |

1 |

| Neurologist Evaluation |

26 |

13 |

12 |

1 |

| Other (e.g., TMJ, Cardiology) |

18 |

7 |

10 |

1 |

Table 4.

Chi-square test results for Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ) item responses. All items demonstrated significant deviation from uniform distributions, indicating patterned responses across domains.

Table 4.

Chi-square test results for Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ) item responses. All items demonstrated significant deviation from uniform distributions, indicating patterned responses across domains.

| SSQ Domain |

Item Description |

χ² (df) |

p-value |

| Speech |

Speech in Noise (TV on) |

125.61 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Multiple Streams (TV & person) |

57.89 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Speech in Speech (Crowd) |

67.16 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Group Speech (Restaurant) |

55.33 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Switching Speakers |

88.26 |

< 0.0001 |

| Spatial |

Localization (Dog barking) |

248.56 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Distance Judgement |

168.11 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Directionality (Coming vs. Going) |

188.84 |

< 0.0001 |

| Qualities |

Segregation (Jumbled Sounds) |

272.88 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Identifying Instruments |

311.27 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Sound Naturalness (Clarity) |

165.83 |

< 0.0001 |

| |

Listening Effort |

46.94 |

< 0.0001 |

Table 5.

Spearman correlation matrix across the three SSQ domains (Speech, Spatial, Qualities). Strong correlations were observed among all domains, particularly between Speech and Qualities (r = 0.81).

Table 5.

Spearman correlation matrix across the three SSQ domains (Speech, Spatial, Qualities). Strong correlations were observed among all domains, particularly between Speech and Qualities (r = 0.81).

| |

Speech |

Spatial |

Qualities |

| Speech |

1.00 |

0.73*** |

0.81*** |

| Spatial |

— |

1.00 |

0.77*** |

| Qualities |

— |

— |

1.00 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).