1. Introduction

Medical personnel wear facemasks to enhance aseptic healthcare delivery [

1]. Facemask use is paramount in controlling respiratory contagions such as the coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [

2,

3]. The pandemic necessitated using facemasks as personal protective equipment [

4]. However, facemasks cause physical, psychological, social, and communication problems [

5]. Facemasks cause a 10% decrease in speech discrimination [

6]. This problem is pronounced in healthcare, where patients and staff rely on effective communication using speech, gestures, non-verbal cues, and emotional pointers [

7]. Facemasks can significantly impair speech perception, frequency, and word translation accuracy [

8]. Impaired communication may worsen healthcare outcomes [

9].

Normal hearing level is 0-19 decibels, mild hearing loss is 20-40 decibels, moderate hearing loss is 41-60 decibels, severe hearing loss is 61-80 decibels, and profound hearing loss is ≥81 decibels [

10,

11]. Moderate to severe hearing loss is denoted as hearing difficulty, and profound hearing loss is denoted as deafness [

10,

12]. Patients with hearing difficulty have struggled with communication even before facemask use became widespread. Facemasks may impede verbal, visual, and emotional communication for patients with hearing difficulty [

12,

13]. Also, facemasks can significantly impair speech intelligibility [

14]. Speech intelligibility is the perceived quality of sound transmission [

8,

15]. The Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) ranges from 0.0 to 1.0, with 1.0 indicating that all speech information is perceived, 0.0 indicating no speech information is perceived, and 0.5-1.0 indicating the normal range [

16]. Facemasks reduce the perception of high-frequency units of sound signals for people with hearing difficulty [

17]. This population relies heavily on visual cues, lip-reading, and facial expressions to decipher the emotional parts of speech, but this opportunity is undermined by facemask use [

12,

15].

Hearing difficulty is associated with older age [

11,

18]. Similarly, chronic pain is prevalent in adults and older adults [

19,

20]. Chronic pain is associated with psychological disorders [

20,

21]. Similarly, hearing difficulty is associated with dementia and depression [

10,

22]. There is a relationship between aging, hearing difficulty, and chronic pain.

During interventional pain treatments, healthcare staff wear facemasks [

1]. However, patients with hearing loss often complain that facemasks impede communication. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the characteristics of adult chronic pain patients with hearing loss. The study determined the prevalence of hearing loss in chronic pain patients. It analyzed the impact of facemasks on clinical communication and outcomes in chronic pain patients during and after the pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred from March 2020 to April 2023. This prospective observational study involved consecutive patients undergoing pain treatment during the pandemic from June 2020 to April 2023 and post-pandemic from May 2023 to June 2024. It was approved by the health authority and specialist pain clinic where the study was conducted in Canada. The research did not require ethical approval because it is a quality assurance study. The research was registered on the Clinical Trials Protocol Registration and Results System (PRS) website, and the PRS number is NCT06072235.

Out of 413 consecutive patients, 67 patients had hearing loss, comprising five patients with profound deafness and 62 patients with an audiometric diagnosis of hearing difficulties. The study focused on 62 patients with hearing difficulty (HD) who use hearing aids and matched them with 62 patients with normal hearing (NH). Inclusion criteria were adults, chronic pain diagnosis, informed consent for therapy, and pain therapy during the pandemic. Exclusion criteria were profound hearing loss, cochlear implant, language barrier, severe loss of vision, and cognitive dysfunction. The prospective methodology minimized selection bias, enabled data collection on multiple variables, and enhanced the discovery of associations between variables and outcomes. The crossover methodology empowered each patient to serve as their control, reduced the influence of confounding variables, required fewer study participants, and increased statistical efficiency.

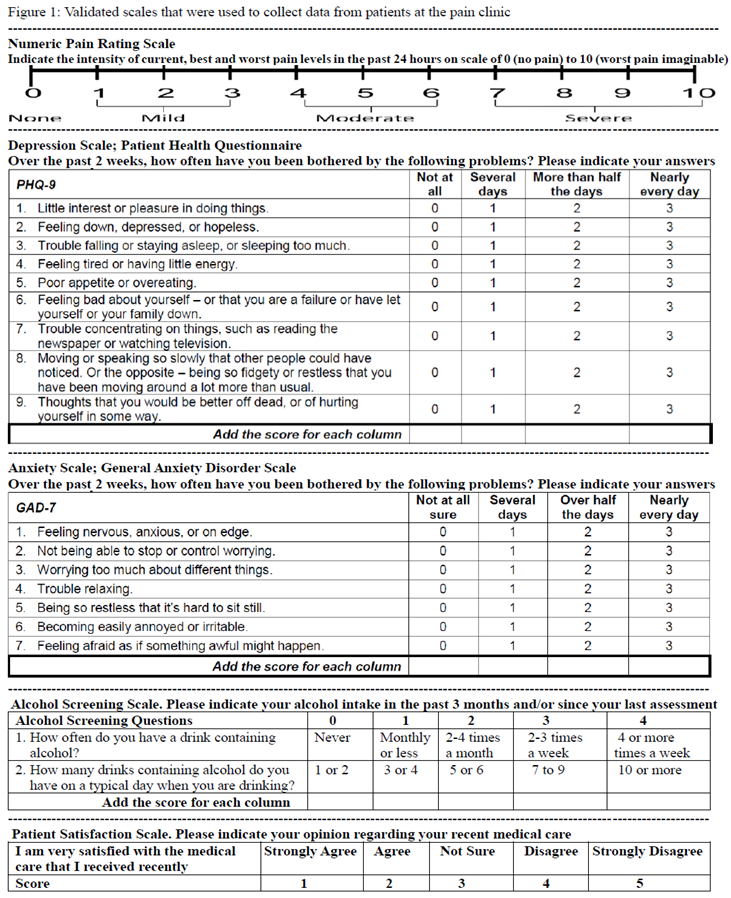

Prospective data collection included patients’ age, gender, pain diagnosis, pain score, anxiety score, depression score, weekly alcohol intake, healthcare satisfaction score, and effects of facemasks on patient care. Data were collected using validated scales for pain, anxiety, depression, alcohol intake, and patient satisfaction. At clinic consultations, patients self-reported their pain score, depression score, anxiety score, alcohol intake, and healthcare satisfaction score using the questionnaire shown in Figure 1. The questionnaire's measurement tools are validated, objective, and reliable. Pain score was measured using the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) of 0-10. Depression score was calculated using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scale of 0-27. Anxiety score was measured using the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale of 0-21. Alcohol intake was assessed using the Alcohol Screening Scale of 0-8. Patient satisfaction with healthcare was evaluated using the Patient Satisfaction Scale of 1-5. The pandemic scores of each patient were compared with their post-pandemic scores. The pandemic and post-pandemic scores of patients with HD were compared with NH patients.

Clinic staff recorded the patients’ age, gender, body mass index (BMI), pain diagnosis, regular analgesic usage, and effects of facemask use on patient communication or care. The impact of facemasks was categorized as (1) the need to repeat or shout speech to the patient, (2) the need to handwrite speech to the patient, (3) the need to remove facemasks to talk to the patient, (4) incomplete consent or treatment due to miscommunication, and (5) radiology or clinic appointment non-compliance.

The data were analysed with IBM® SPSS® Statistics 28 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) using the student T-test, paired T-test, analysis of variance, Chi-square test, regression analysis, and Fisher's exact test. P-value <0.05 was considered as significant. The data was organized, compared, and presented as numbers, averages, ranges, percentages, categories, and descriptions.

3. Results

Of the 413 patients, 67 patients (16.2%) had hearing loss, comprising five patients (1.2%) with profound deafness and 62 patients (15%) with the audiometric diagnosis of hearing difficulty.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients with HD (n=62) and matched NH patients (n=62). Most patients in both groups were older adults (age >65 years), constituting 56% of the HD group and 53% of the NH group. Most patients in the HD group were male, comprising 58% of the group. The majority of patients in both groups were obese (BMI >30), constituting 60% of the HD group and 56% of the NH group. Most patients in both groups were treated for spinal or paraspinal pain, constituting 68% of the HD group and 71% of the NH group. Approximately 61% of the patients with HD and 63% of the NH patients regularly used weak opioid analgesics (codeine or tramadol). In comparison, potent opioid analgesics (oxycodone or morphine) were used regularly by 16% of the HD group and 18% of the NH group.

Table 2 shows the scores of both patient groups. It depicts their physiological and psychological scores. For patients with HD, the scores of pain, depression, anxiety, alcohol intake, and healthcare satisfaction were worse during the pandemic compared to the post-pandemic. During the pandemic, patients with HD suffered more pain, anxiety, and depression than NH patients.

Table 3 shows the effects of facemasks on communication and clinical care during the post-pandemic and pandemic periods. During the pandemic, there was an increased need for pain clinic staff to repeat or shout speech to patients with HD compared to NH patients (p=0.001). Additionally, clinic staff needed to remove their facemasks while talking to patients with HD but not NH patients (p=0.001). In the HD group, there were more missed radiology or pain clinic appointments (p=0.035) and a greater need for clinic staff to handwrite speech (p=0.001) during the pandemic than in the post-pandemic period. Furthermore, patients with HD had incomplete consents or treatments due to communication difficulties during the pandemic, but no such problem occurred during the post-pandemic period (p=0.044).

4. Discussion

Hearing difficulty, chronic pain, and aging pose challenges for some adults. The association of these factors significantly impacts some patients’ physiological and psychological well-being. The prevalence of hearing difficulty is 6-17% in the general adult population [

10,

15]. However, our study revealed a relatively higher prevalence of 16.2% in the adult chronic pain patient population. Aging is a risk factor for hearing loss, and our study's relatively high prevalence of hearing loss is partly attributable to the preponderance of older patients in the chronic pain clinic. Additionally, hearing loss is more common in men than women [

23]. This fact is corroborated by our study, where most patients with hearing difficulty were males. This male preponderance also contributes to our study population's high prevalence of hearing loss.

Hearing difficulty is associated with poorer patient-provider communication, healthcare quality, and patient satisfaction [

10]. Patient satisfaction is essential for good healthcare compliance and outcomes [

21,

24]. Facemasks impede the ability of healthcare providers to pick up non-verbal cues from patients, which causes misdiagnosis, mistrust, or patient dissatisfaction [

12]. Therefore, our clinic adopted telehealth, an evolving healthcare delivery modality beneficial for patients with hearing difficulty [

25,

26]. The clinic increased the use of email, text, and electronic communications for patients with hearing difficulty. Despite the clinic’s adoption of telehealth, some patients did not have cell phones or email access. To mitigate this problem, the clinic sent electronic notifications through the patient’s designated intermediaries or relatives. Although this multilevel communication was time-consuming, it effectively enhanced patients’ compliance with treatments and appointments. Our study highlights the need for technological adaptation and adoption to enhance communication for patients with hearing difficulty.

Our study revealed that communication problems were more severe among patients with hearing difficulty than those with normal hearing during the pandemic. To mitigate these challenges, healthcare staff had to speak louder, handwrite, or repeat questions. This corroborates previous studies that showed increased speech or voice volumes when healthcare workers wear facemasks [

13,

15,

17]. Occasionally, staff removed their facemasks to communicate with patients, during which they resorted to physical distancing and face shields for protection. However, face shields are not as protective as facemasks [

6]. Alternatively, transparent facemasks may improve speech perception for patients with hearing difficulty since transparent facemasks maintain visual input [

27]. However, transparent facemasks are not readily available since they are scarce and expensive. This highlights the necessity of innovations in personal protective equipment and other forms of aids in communicating. Other tools such as hearing-assisted devices or real-time transcription services could significantly enhance communication with patients with hearing loss [

28,

29].

Hearing loss constitutes a significant socioeconomic burden, increasing healthcare costs and utilization [

10,

18,

30]. Our study revealed unusual occurrences of incomplete consent and interventional treatment procedures involving patients with hearing difficulty during the pandemic. Despite the best efforts of the clinic staff, some patients with hearing difficulty were uncertain about treatment procedures and consent, and their treatment had to be abandoned. Additionally, these patients had decreased treatment compliance during the pandemic, including missed pharmacy, radiology, therapist, and pain clinic appointments. It is essential to be aware of the intersectionality of hearing loss and other chronic medical conditions such as chronic pain and chronic systemic diseases that are more common in older patients [

10,

20,

31,

32]. These different points further compound and increase the complexity of care in patients with hearing difficulties. Therefore, it is crucial to have a multidisciplinary approach for these patients, including audiological care and psychological, social service, and chronic care management to address all aspects of care [

20,

32]. During the pandemic, the abandoned treatments and missed appointments caused by facemask-impaired communication influenced poorer outcomes in patients with hearing difficulty.

Hearing difficulty is associated with psychological and mood disorders [

10,

31,

32]. Our study revealed worse pain, anxiety, depression, alcohol intake, and patient satisfaction scores in patients with hearing difficulty during the pandemic than in the post-pandemic period. All these parameters were worse in these patients than in those with normal hearing. These revelations highlight the impact of pandemic-related stress and psychological disorders, a problem partly attributable to increased facemask use [

5]. These findings indicate that healthcare staff should be proactive regarding the communication and psychological needs of patients with hearing difficulty, especially when staff are wearing facemasks.

Alcohol consumption may predispose to hearing difficulty [

23]. Some people consume more alcohol during periods of stress or anxiety. Our study revealed that patients with hearing difficulty consumed more alcohol during the pandemic compared to the post-pandemic period. This indicates that these patients experienced more severe pandemic-related stress, hence their higher alcohol consumption. Their higher alcohol consumption during the pandemic may potentially aggravate pre-existing hearing loss. Therefore, better psychological support should be provided to these patients during stressful periods to minimize alcohol requirements during such periods.

This study was limited by the consecutive patient recruitment method, which required a longer study period. However, the prospective cohort methodology minimized the risk of bias, enabled data collection on multiple variables or outcomes, and enhanced the discovery of new associations between variables and outcomes. To reduce confounding factors, the patients with hearing difficulty were appropriately matched with normal-hearing patients.

5. Conclusions

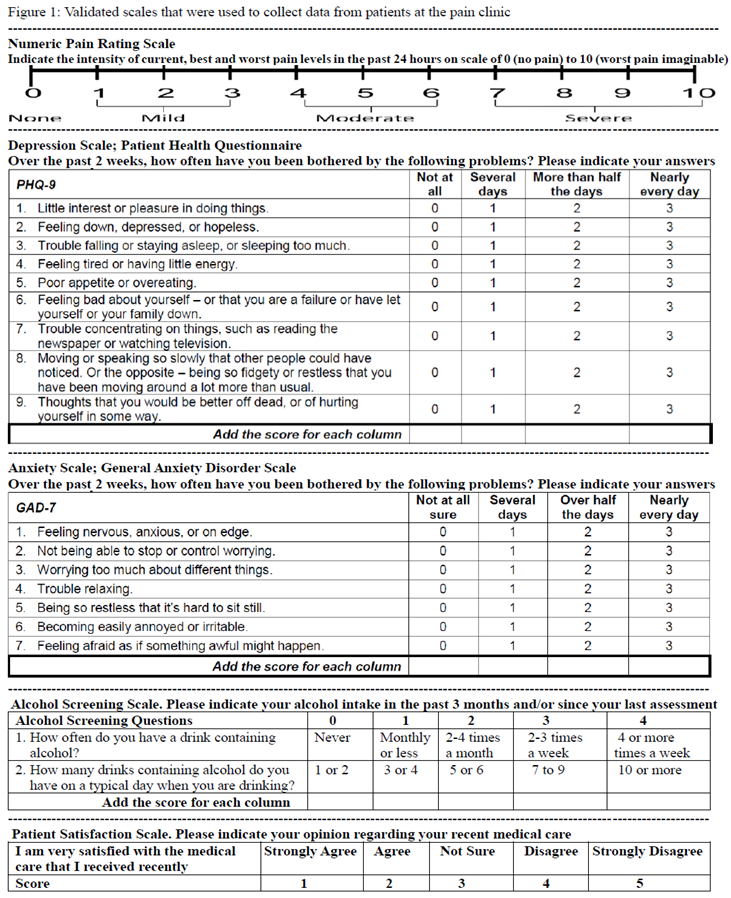

Healthcare staff must be mindful that facemasks can impede communication and aggravate patients’ psychological disorders. This may reduce patient satisfaction, treatment compliance, and clinical outcomes. Therefore, healthcare providers should employ innovative strategies to improve clinical communication and care for patients with hearing difficulty, such as speaking slowly and accentuating non-verbal or visual cues. When available, healthcare staff should use transparent facemasks when treating patients with hearing difficulty. Also, these patients may apply unique stickers on their facemasks to indicate their hearing difficulty, and such stickers are cheap, reusable, and removable (sticker example in

Figure 2).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research did not require ethical approval because it is a quality assurance study of routine clinical care. Ethical review and approval were waived by the local healthcare organization which confirmed that it is a quality assurance study and does not require a formal review by the research ethics board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset presented in the study is available on request from the corresponding author during submission or after publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bamgbade, O. A.; Richards, R. N.; Mwaba, M.; Ajirenike, R. N.; Metekia, L. M.; Olatunji, B. T. Facial topical cream promotes facemask tolerability and compliance during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 2022, 17 (3), 441–447. [CrossRef]

- Al Harthi, H,; Al Fannah, J.; Khamis, F.; Al Hasmi, S.; Al Siabi, B.; Al Habsi, A.; Al Muniri, A.; Al Salmi, Q.; Al Awaidy, S. Oman's COVID-19 publication trends: A cross-sectional bibliometric study. Public Health Practice Oxford 2022, 4:100310. [CrossRef]

- Jose, J.; Saberi, M. K.; Khamis, F.; Mokthari, H.; Al Zakwani, I. COVID-19 Medical Research in Oman: A Bibliometric and Visualization Study. Oman Medical Journal 2022, 37 (4):e406. [CrossRef]

- Bamgbade, O. A.; Onongaya, V. O.; Metekia, L. M.; Al Harthi, H. A.; Tase, N. E.; Oluwole, O.; Lawal, O. O.; Atcham Amougou, L. M.; Khanyile, T. M.; Soni, N. K.; Manuel, B.; Butelezi, G. P.; Hoggar, S. K.; Mulenga, J. M. Behavioral Implications of COVID-19 Prevention and Vaccination Status in Africa During 2023. Preprints 2024, 2024112092. [CrossRef]

- Scheid, J. L.; Lupien, S. P.; Ford, G. S.; West, S. L. Commentary: Physiological and Psychological Impact of Face Mask Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(18), 6655. [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, S. V.; Augustine, A. M.; Lepcha, A.; Sebastian, S.; Gowri, M.; Philip, A.; Mammen, M. D. The effects of N95 mask and face shield on speech perception among healthcare workers in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic scenario. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 2020, 134 (10), 895–898. [CrossRef]

- Balton, S.; Vallabhjee, A. L.; Pillay, S. C. When uncertainty becomes the norm: The Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital’s Speech Therapy and Audiology Department’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. South African Journal of Communication Disorders 2022, 69 (2). [CrossRef]

- Magee, M.; Lewis, C.; Noffs, G.; Reece, H.; Chan, J. C. S.; Zaga, C. J.; Paynter, C.; Birchall, O.; Azocar, S. R.; Ediriweera, A.; Kenyon, K.; Caverlé, M. W.; Schultz, B. G.; Vogel, A. P. Effects of face masks on acoustic analysis and speech perception: Implications for peri-pandemic protocols. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2020, 148(6), 3562–3568. [CrossRef]

- Khoza-Shangase, K.; Moroe, N.; Neille, J.; Edwards, A. The impact of COVID-19 on speech–language and hearing professions in low- and middle-income countries: Challenges and opportunities explored. South African Journal of Communication Disorders 2022, 69 (2). [CrossRef]

- Deal, J. A.; Reed, N. S.; Kravetz, A. D.; Weinreich, H.; Yeh, C.; Lin, F. R.; Altan, A. Incident hearing loss and comorbidity. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2018, 145 (1), 36. [CrossRef]

- Khabori, M. A.; Khandekar, R. The prevalence and causes of hearing impairment in Oman: a community-based cross-sectional study. International Journal of Audiology 2004, 43 (8), 486–492. DOI: 10.1080/14992020400050062.

- Chodosh, J.; Weinstein, B. E.; Blustein, J. Face masks can be devastating for people with hearing loss. BMJ 2020, m2683. [CrossRef]

- Hampton, T.; Crunkhorn, R.; Lowe, N.; Bhat, J.; Hogg, E.; Afifi, W.; De, S.; Street, I.; Sharma, R.; Krishnan, M.; Clarke, R.; Dasgupta, S.; Ratnayake, S.; Sharma, S. The negative impact of wearing personal protective equipment on communication during coronavirus disease 2019. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 2020, 134 (7), 577–581. [CrossRef]

- Alkharabsheh, A.; Aboudi, O.; Abdulbaqi, K.; Garadat, S. The effect of wearing face mask on speech intelligibility in listeners with sensorineural hearing loss and normal hearing sensitivity. International Journal of Audiology 2022, 62 (4), 328–333. [CrossRef]

- Rahne, T.; Fröhlich, L.; Plontke, S.; Wagner, L. Influence of surgical and N95 face masks on speech perception and listening effort in noise. PLoS ONE 2021, 16 (7), e0253874. [CrossRef]

- Sönnichsen, R.; Tó, G. L.; Hochmuth, S.; Hohmann, V.; Radeloff, A. How face masks interfere with speech Understanding of Normal-Hearing Individuals: Vision makes the difference. Otology & Neurotology 2022, 43 (3), 282–288. [CrossRef]

- Shekaraiah, S.; Suresh, K. Effect of face mask on voice production during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic review. Journal of Voice 2021, 38 (2), 446–457. [CrossRef]

- Khabori, M. A.; Khandekar, R. Unilateral hearing impairment in Oman: a Community-Based Cross-Sectional study. Ear Nose & Throat Journal 2007, 86 (5), 274–280. [CrossRef]

- Bamgbade, O. A.; Aloul, Z. S.; Omoniyi, D. A.; Adebayo, S. A.; Magboh, V. O.; Rodrigues, S. P. Lidocaine swallow analgesia for severe painful prolonged esophageal disorders. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia 2021, 15 (2), 244–245. [CrossRef]

- Bamgbade, O. A.; Sonaike, M. T.; Adineh-Mehr, L.; Bamgbade, D. O.; Aloul, Z. S.; Thanke, C. B.; Thibela, T.; Gitonga, G. G.; Yimam, G. T.; Mwizero, A. G.; Alawa, F. B.; Kamati, L. O.; Ralasi, N. P.; Chansa, M. Pain Management and Sociology implications: The sociomedical problem of pain clinic staff harassment caused by chronic pain patients. Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine 2024, 14 (2). [CrossRef]

- Parkoohi, P. I.; Amirzadeh, K.; Mohabbati, V.; Abdollahifard, G. Satisfaction with chronic pain treatment. Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine 2015, 5 (4). [CrossRef]

- Khandekar, R.; Kantharaju, K.K.; Mane, P.; Hassan, A. R.; Niar, R.; A, S. F.; Al-Khabori, M.; Al-Harby, S. Hearing Health Practices and Beliefs among over 20 year-olds in the Omani Population. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2010, 10(2):241-8. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3074718/.

- Curhan, S. G.; Eavey, R.; Shargorodsky, J.; Curhan, G. C. Prospective study of alcohol use and hearing loss in men. Ear And Hearing 2010, 32 (1), 46–52. [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhn, E. G.; Lemma, G. F. Patient satisfaction with the perioperative surgical services and associated factors at a University Referral and Teaching Hospital, 2014: a cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal 2017, 27. [CrossRef]

- Frisby, C.; Eikelboom, R.; Mahomed-Asmail, F.; Kuper, H.; Swanepoel, D. W. M-Health Applications for Hearing Loss: A scoping review. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 2021, 28 (8), 1090–1099. [CrossRef]

- Tar-Mahomed, Z.; Kater, K.-A. The perspectives of speech–language pathologists: Providing teletherapy to patients with speech, language and swallowing difficulties during a COVID-19 context. South African Journal of Communication Disorders 2022, 69 (2). [CrossRef]

- Atcherson, S. R.; Mendel, L. L.; Baltimore, W. J.; Patro, C.; Lee, S.; Pousson, M.; Spann, M. J. The Effect of Conventional and Transparent Surgical Masks on Speech Understanding in Individuals with and without Hearing Loss. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2016, 28 (01), 058–067. [CrossRef]

- Koerber, R. M.; Kokorelias, K. M.; Sinha, S. K. The clinical use of personal hearing amplifiers in facilitating accessible patient–provider communication: A scoping review. Journal of American Geriatric Society 2024; 72 (7): 2195-2205. [CrossRef]

- Jama, G. M.; Shahidi, S.; Danino, J.; Murphy, J. Assistive communication devices for patients with hearing loss: a cross-sectional survey of availability and staff awareness in outpatient clinics in England. Disability Rehabilitation Assistive Technology 2020, 15 (6):625-628. [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthy, N. A.; Abugad, H.; Zabeeri, N.; Alghamdi, A. A.; Yousif, G. F. A.; Darwish, M. A. Noise Mapping, Prevalence and Risk Factors of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss among Workers at Muscat International Airport. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19 (13), 7952. [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, D. W.; Strauss, S.; Becker, P.; Grobler, L. M.; Eloff, Z. Occupational noise and age: A longitudinal study of hearing sensitivity as a function of noise exposure and age in South African gold mine workers. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 2020, 67(2), a687. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Blum, S.; Voss, E. (2017). The psychological impact of hearing loss and its association with depressive symptoms: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 2017, 24 (4), 436-444. [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

Sticker on a facemask to indicate that the wearer has hearing difficulties.Author Contributions: For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, OAB.; methodology, OAB., LMM., HD.; validation, OAB., AMA., VOO.; formal analysis, OAB., AAA., NET.; investigation, OAB., AMA., OOO.; resources, OAB.; data curation, OAB., TM., MK.; writing—original draft preparation, OAB., NPS., RR.; writing—review and editing, OAB., LMM., HD., AMA., VOO., AAA., NET., AMA., OOO., TM., MK., NPS., RR.; visualization, OAB., LMM., HD., AMA., VOO., AAA., NET., AMA., OOO., TM., MK., NPS., RR.; supervision, OAB.; project administration, OAB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 2.

Sticker on a facemask to indicate that the wearer has hearing difficulties.Author Contributions: For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, OAB.; methodology, OAB., LMM., HD.; validation, OAB., AMA., VOO.; formal analysis, OAB., AAA., NET.; investigation, OAB., AMA., OOO.; resources, OAB.; data curation, OAB., TM., MK.; writing—original draft preparation, OAB., NPS., RR.; writing—review and editing, OAB., LMM., HD., AMA., VOO., AAA., NET., AMA., OOO., TM., MK., NPS., RR.; visualization, OAB., LMM., HD., AMA., VOO., AAA., NET., AMA., OOO., TM., MK., NPS., RR.; supervision, OAB.; project administration, OAB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the hearing-difficulty patients (n=62) and matched normal-hearing patients (n=62) who underwent treatment in the pain clinic during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods .

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the hearing-difficulty patients (n=62) and matched normal-hearing patients (n=62) who underwent treatment in the pain clinic during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods .

| Parameter |

Category |

Hearing-difficulty; n=62 |

Normal-hearing; n=62 |

| Age |

44-64 years |

27 (44%) |

29 (47%) |

| |

65-91 years |

35 (56%) |

33 (53%) |

| Gender |

Female |

26 (42%) |

31 (50%) |

| |

Male |

36 (58%) |

31 (50%) |

| Body Mass Index |

20-29.9 |

25 (40%) |

27 (44%) |

| |

30-59.9 |

37 (60%) |

35 (56%) |

| Hearing aid use |

Yes |

62 (100%) |

0 |

| |

No |

0 |

62 (100%) |

| Chronic pain type |

Spinal or paraspinal pain |

42 (68%) |

44 (71%) |

| |

Non-spinal limb pain |

20 (32%) |

18 (29%) |

| Regular analgesic type |

Acetaminophen/Paracetamol |

14 (23%) |

12 (19%) |

| |

Codeine or Tramadol |

38 (61%) |

39 (63%) |

| |

Oxycodone or Morphine |

10 (16%) |

11 (18%) |

Table 2.

Measurements of pain, depression, anxiety, alcohol intake, and satisfaction of hearing-difficulty patients and matched normal-hearing patients who underwent treatment in pain clinic during pandemic and post-pandemic periods .

Table 2.

Measurements of pain, depression, anxiety, alcohol intake, and satisfaction of hearing-difficulty patients and matched normal-hearing patients who underwent treatment in pain clinic during pandemic and post-pandemic periods .

| Parameter |

Period |

Hearing-difficulty patients (mean±SD) |

Normal-hearing patients (mean±SD) |

| Pain score, on a scale of 0-10 |

Post-pandemic |

4±2 |

4±2 |

| |

Pandemic |

7±2 |

5±2 |

| Anxiety score, on a scale of 0-21 |

Post-pandemic |

10±4 |

10±3 |

| |

Pandemic |

17±3 |

12±2 |

| Depression score, on a scale of 0-27 |

Post-pandemic |

11±3 |

10±3 |

| |

Pandemic |

19±4 |

13±2 |

| Alcohol intake score, on a scale of 0-8 |

Post-pandemic |

3±3 |

3±3 |

| |

Pandemic |

5±2 |

4±2 |

| Patient satisfaction score, on a scale of 1-5 |

Post-pandemic |

2±1 |

2±1 |

| |

Pandemic |

3±1 |

2±1 |

Table 3.

Incidental effects of facemask use on communication and clinical care for hearing-difficulty patients and matched normal-hearing patients who underwent treatment in pain clinic during post-pandemic and pandemic periods .

Table 3.

Incidental effects of facemask use on communication and clinical care for hearing-difficulty patients and matched normal-hearing patients who underwent treatment in pain clinic during post-pandemic and pandemic periods .

| Parameter |

Period |

Hearing-difficulty

patients’ occurrence rate % |

Normal-hearing patients’

occurrence rate % |

| Need to repeat or shout speech to patient |

Post-pandemic |

20 |

0 |

| |

Pandemic |

80 |

10 |

| Need to handwrite speech to patient |

Post-pandemic |

0 |

0 |

| |

Pandemic |

40 |

0 |

| Need to remove facemask to talk to patient |

Post-pandemic |

0 |

0 |

| |

Pandemic |

60 |

0 |

| Incomplete consent or treatment because of miscommunication |

Post-pandemic |

0 |

0 |

| |

Pandemic |

20 |

0 |

| Clinical or radiology appointment non-compliance |

Post-pandemic |

5 |

5 |

| |

Pandemic |

50 |

5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).