1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic introduced unprecedented global challenges that extended well beyond the physical health domain, influencing psychological well-being, emotional resilience, and quality of life. In addition to its biological impact, the pandemic triggered widespread psychological distress due to prolonged isolation, uncertainty, and disruption of daily life (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Cullen, Gulati, & Kelly, 2020). Taylor (2022) emphasized that the psychological footprint of pandemics can exceed the medical footprint, as emotional responses are often more pervasive and longer lasting than the infection itself. For example, during early lockdowns in 2020, only 2% of a North American sample reported COVID-19 diagnosis, yet 20% experienced elevated anxiety and depression (Taylor et al., 2020).

Stress-related disorders such as PTSD, OCD, and prolonged grief disorder have all been linked to pandemic-related experiences, including the loss of loved ones, income insecurity, and disruption of social rituals (Taylor, 2019). Xiong et al. (2020) reported an increased global burden of mental disorders and suicidality driven by COVID-19-related isolation, financial stress, and uncertainty. These mental health challenges were compounded by reduced access to non-urgent healthcare services, including hearing healthcare and tinnitus management (Beukes et al., 2021).

Tinnitus, a perception of sound without an external source, affects a substantial portion of the population and is known to be exacerbated by stress and emotional distress (Mazurek et al., 2015; Kennedy et al., 2004). Individuals with tinnitus often report worsened symptoms during periods of psychological strain, and the pandemic may have further amplified these effects (Beukes et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2022). The multifactorial nature of tinnitus, involving audiological and psychological dimensions, makes it especially susceptible to contextual influences such as those imposed by the pandemic.

Emerging literature has also identified the COVID-19 vaccine as a potential trigger for new-onset or worsening tinnitus in susceptible individuals. For example, Yellamsetty et al. (2023); Yellamsetty et al. (2024a, 2024b); and Bao et al. (2024) reported increased tinnitus severity following vaccination, with a notable association between pre-existing metabolic disorders and post-vaccination auditory symptoms. Aydogan et al. (2024), Tai et al. (2024), and Jiang et al. (2025) further support the link between tinnitus and mental health vulnerability during the pandemic. Additional studies (e.g., Yellamsetty et al., Front. Public Health, 2024; Wang et al., 2024, JMIR Formative Res.) emphasize the need for ongoing public health surveillance of post-vaccine auditory symptoms, particularly in populations with predisposing risk factors.

Validated instruments such as the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI; Newman et al., 1996) and Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ; Wilson et al., 1991) provide standardized tools for assessing tinnitus severity and associated psychological distress. These tools were used in the present study to evaluate longitudinal changes in tinnitus perception and reaction from before the pandemic, through its peak, and into the post-pandemic period.

Studying tinnitus symptoms over a longitudinal timeline capturing data before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic is essential to understanding the trajectory of auditory and psychological symptom evolution. This approach allows researchers to distinguish between transient and persistent changes in tinnitus severity and identify potential causal patterns associated with vaccination, infection, and psychological stressors. These insights are especially critical for clinicians and policymakers seeking to implement timely interventions and develop robust public health strategies in response to evolving crises.

This study aimed to investigate the psychological and auditory impacts of COVID-19 and vaccination on individuals with tinnitus, using a cross-sectional survey approach. By analyzing self-reported symptoms across multiple timepoints, this research contributes to a growing body of evidence addressing the biopsychosocial burden of tinnitus in the context of a global health crisis.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Recruitment

This study employed a cross-sectional design to examine the psychological and perceptual effects of COVID-19 and its vaccination on individuals with and without tinnitus. Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling approach (Beukes, Manchaiah, & Roeser, 2020). The recruitment strategy included distribution of a Qualtrics-based online survey via multiple channels: social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn), email outreach to voluntary research registries, and physical flyers posted in audiology clinics in the Bay Area. The survey link was accessible to a national audience across the United States to promote geographic diversity in participation.

2.2. Participants

Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years of age, residing in the United States, and having a history of COVID-19 vaccination or infection, regardless of tinnitus status. Participants self-reported their demographics, medical history, COVID-19 exposure and vaccination details, and tinnitus experience.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at San José State University. Informed consent was obtained electronically prior to survey participation. The consent form outlined the study’s objectives, procedures, confidentiality safeguards, participants’ rights, and contact information for study personnel and the IRB.

2.4. Survey Materials

Data collection occurred between December 2023 and April 2024. The survey consisted of four main components: (1) demographic information; (2) medical history, including pre-existing audiological and systemic conditions; (3) COVID-19 and vaccination history; and (4) two validated self-report instruments assessing tinnitus severity and distress. These instruments included the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) and the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ), both of which have been extensively validated in prior tinnitus research.

2.5. Data Analysis Strategy

All analyses were performed using SPSS and R version 4.3.1. Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize participant characteristics and survey responses. Differences in tinnitus severity across timepoints (before, during, and current) were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where assumptions of sphericity were violated, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied. Chi-square tests were used to examine group differences in symptom severity across gender and vaccine dose. Significance thresholds were set at p < .05 for all analyses, and effect sizes (e.g., partial eta squared) were reported where appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample

A total of 189 participants completed the survey, with 55.6% identifying as female (n = 105) and 44.4% as male (n = 84). The mean age for male participants was 53.42 years (SD = 16.43), while females had a mean age of 48.19 years (SD = 17.77). An independent samples t-test revealed a statistically significant difference in age between male and female participants (t(187) = 2.08, p = 0.039), with males being significantly older on average.

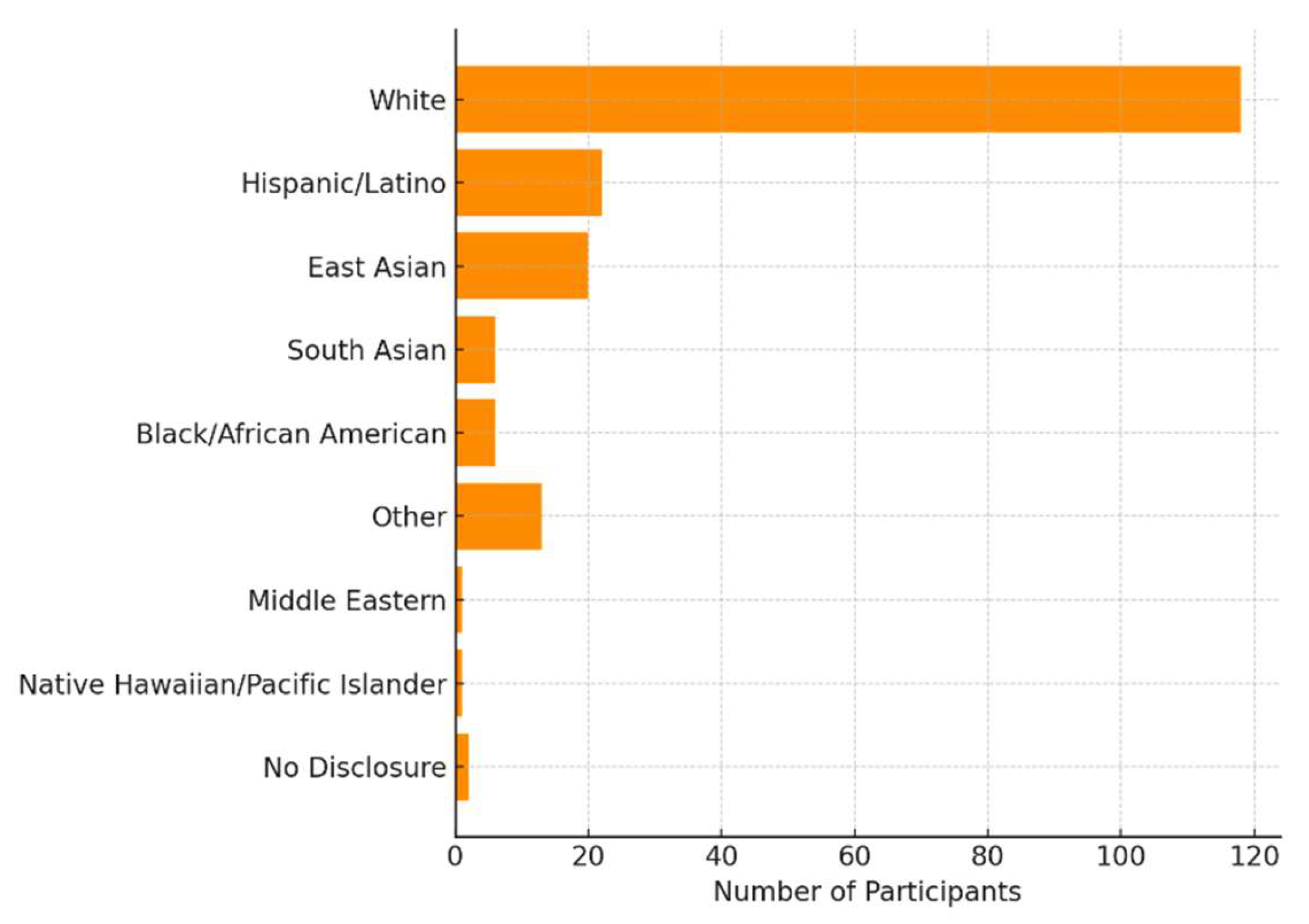

In terms of ethnicity (

Figure 1), the majority of participants identified as European American / White (62.4%), followed by Hispanic / Latino (11.6%), East Asian (10.6%), South Asian (3.2%), and Black / African American (3.2%). Smaller proportions identified as Middle Eastern (0.5%), Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander (0.5%), Other (6.9%), or selected No Disclosure (1.1%).

3.2. Medical History of Participants

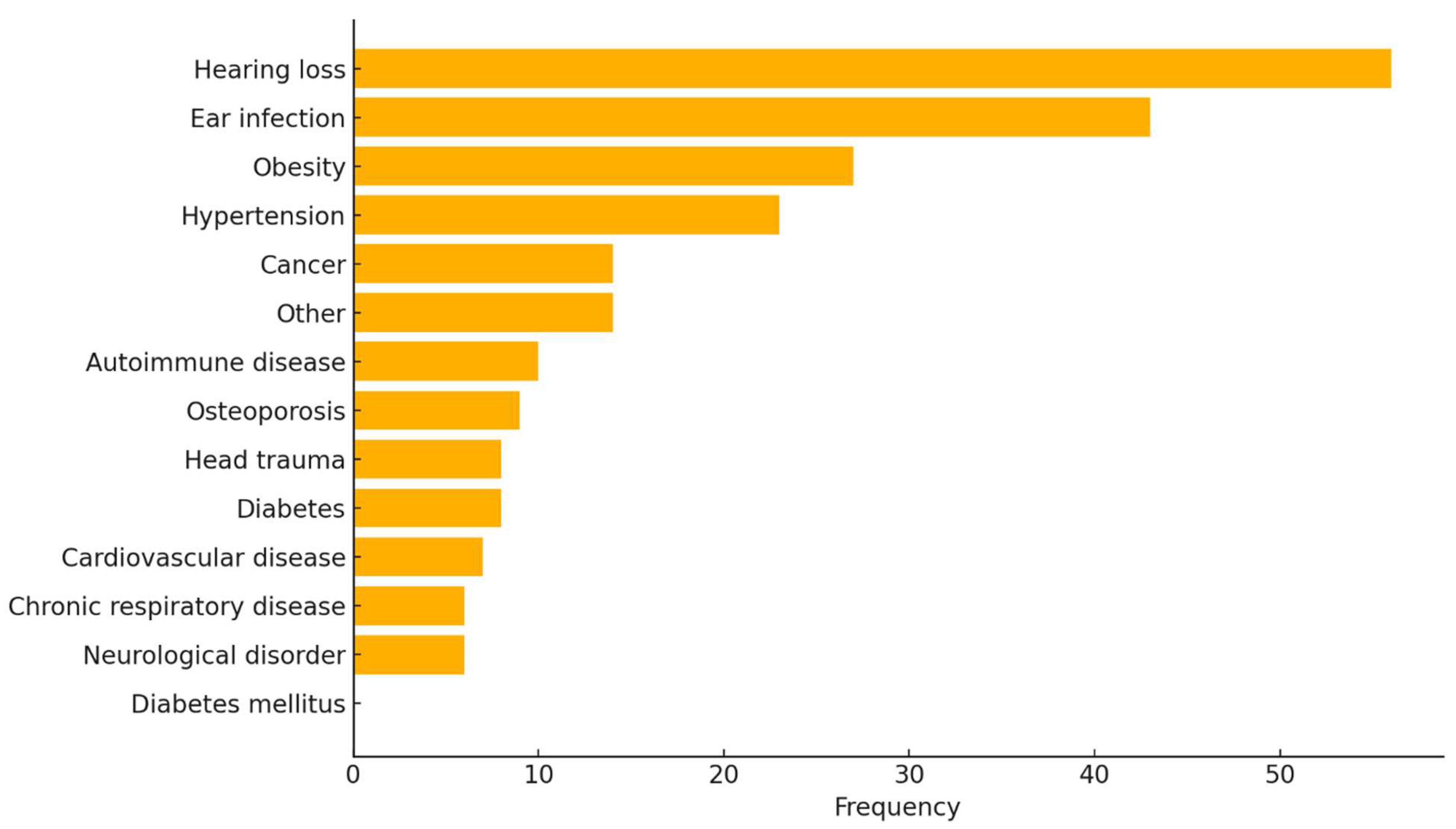

Participants reported a range of pre-existing medical conditions, most commonly hearing loss (29.6%,

n = 56) and ear infections (22.8%,

n = 43). Additionally, obesity (14.3%,

n = 27), hypertension (12.2%,

n = 23), and cancer or other conditions (each 7.4%,

n = 14) were also noted. Less frequently reported conditions included autoimmune diseases (5.3%,

n = 10), osteoporosis (4.8%,

n = 9), head trauma and diabetes (each 4.2%,

n = 8), cardiovascular disease (3.7%,

n = 7), chronic respiratory disease and neurological disorders (each 3.2%,

n = 6), while diabetes mellitus was not reported (

Figure 2). These findings reflect a broad spectrum of comorbidities that may intersect with tinnitus severity and perception in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.3. COVID-19 Vaccination Status

Participants reported their COVID-19 vaccination history across primary doses and booster shots (

Table 1). For the first dose, the most common vaccine received was Pfizer-BioNTech (53.2%,

n = 100), followed by Moderna (38.3%,

n = 72), Johnson & Johnson (7.4%,

n = 14), and Other vaccines (1.1%,

n = 2). A similar pattern was observed for the second dose, with Pfizer-BioNTech (53.8%,

n = 91) and Moderna (43.8%,

n = 74) being the predominant vaccines, while Johnson & Johnson and Other each accounted for 1.2% (

n = 2). Among participants who received a first booster, 53.0% (

n = 70) received Pfizer-BioNTech and 44.7% (

n = 59) received Moderna, with very few reporting Johnson & Johnson (0.8%,

n = 1) or another vaccine (1.5%,

n = 2). The second booster was administered to a smaller group (

n = 81), with Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna accounting for 50.6% (

n = 41) and 43.2% (

n = 35), respectively. A limited number of participants received Johnson & Johnson (

n = 2) or other vaccines (

n = 3). For the third booster, only 50 participants reported vaccine type: 58.0% (

n = 29) received Pfizer-BioNTech, 40.0% (

n = 20) received Moderna, and 2.0% (

n = 1) received a different vaccine.

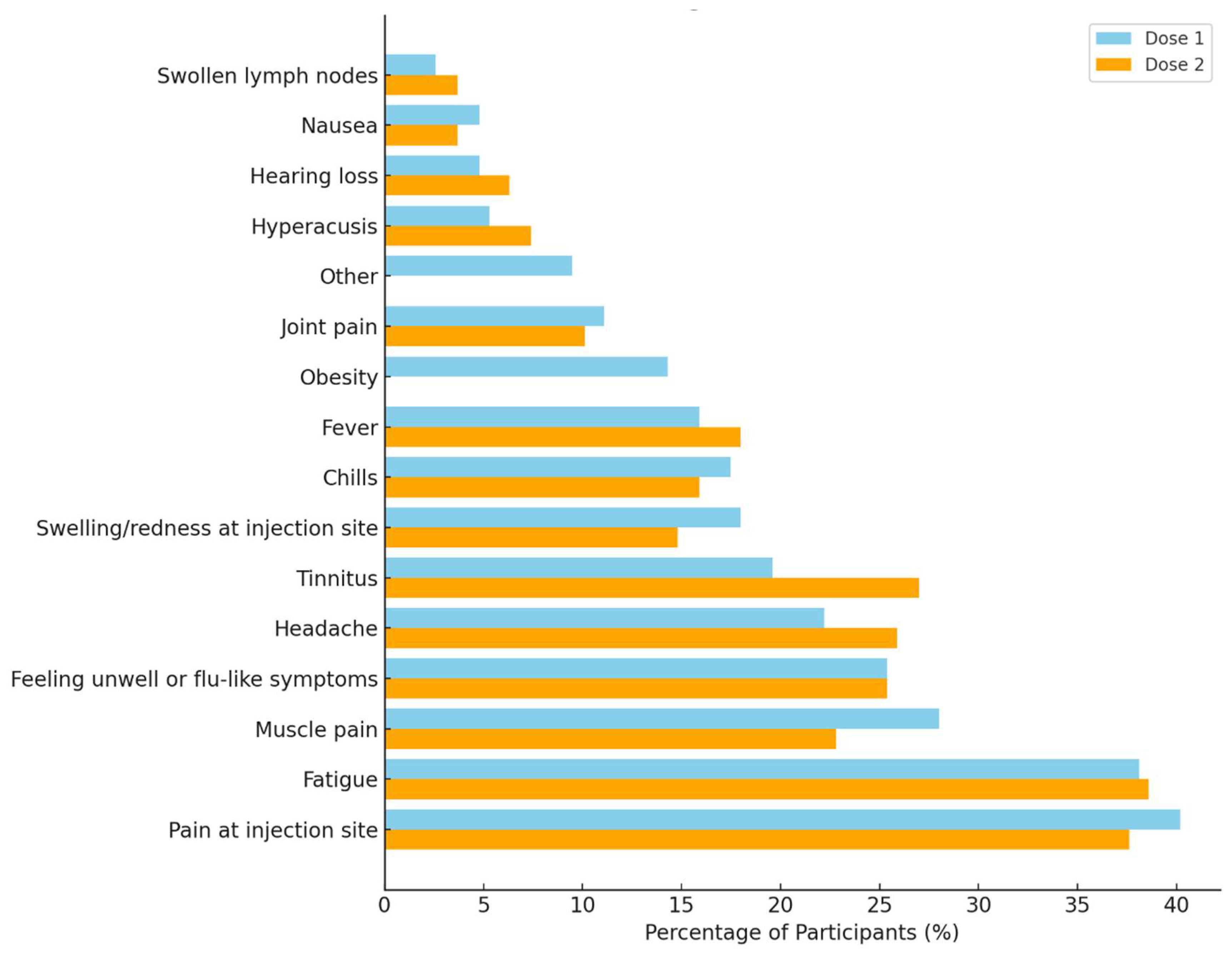

3.4. Adverse Reactions and Symptom Severity Following COVID-19 Vaccination

Participants reported a wide range of adverse reactions following both the first and second doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. After the first dose, the most frequently reported reactions were pain at the injection site (40.2%), fatigue (38.1%), and muscle pain (28.0%). Additional systemic symptoms included feeling unwell or flu-like (25.4%), headache (22.2%), fever (15.9%), and chills (17.5%). Notably, 19.6% of respondents reported tinnitus, along with other audiological symptoms such as hyperacusis (5.3%) and hearing loss (4.8%).

Reactions following the second dose were comparable, with fatigue (38.6%), pain at the injection site (37.6%), and headache (25.9%) being most commonly reported. A higher proportion of participants reported tinnitus (27.0%) after the second dose compared to the first. Other reactions included muscle pain (22.8%), feeling unwell (25.4%), and fever (18.0%). Audiological symptoms also persisted after the second dose, including hyperacusis (7.4%) and hearing loss (6.3%).

Figure 3.

Comparison of self-reported adverse reactions following the first and second doses of COVID-19 vaccination. The most frequently reported symptoms across both doses were pain at the injection site and fatigue, with notable audiological symptoms including tinnitus, hyperacusis, and hearing loss. Percentages reflect the proportion of participants endorsing each symptom.

Figure 3.

Comparison of self-reported adverse reactions following the first and second doses of COVID-19 vaccination. The most frequently reported symptoms across both doses were pain at the injection site and fatigue, with notable audiological symptoms including tinnitus, hyperacusis, and hearing loss. Percentages reflect the proportion of participants endorsing each symptom.

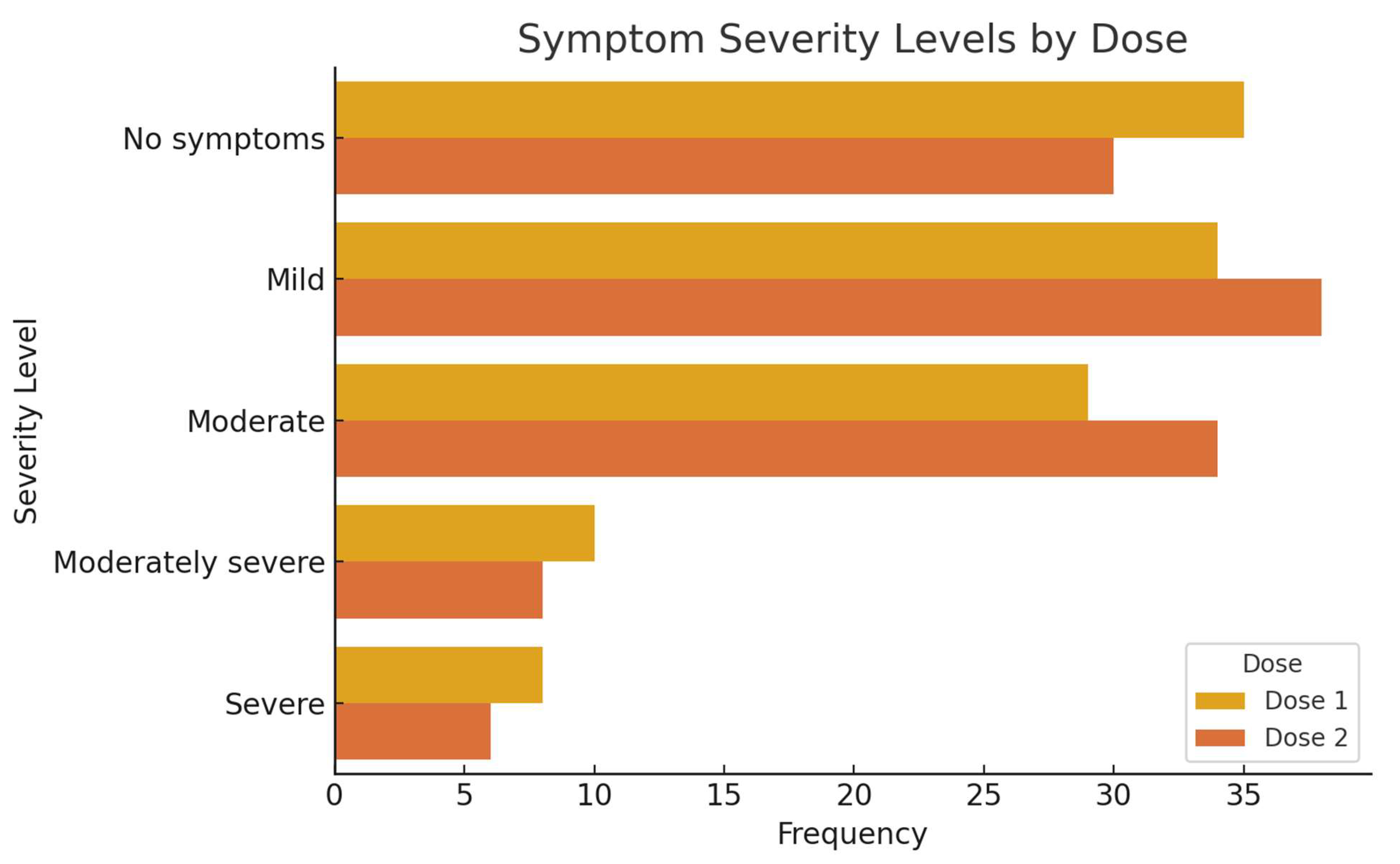

Symptom severity was evaluated across both doses (

Figure 4). After the first dose, 30.2% of participants reported no symptoms, 29.3% reported mild symptoms, 25.0% moderate symptoms, 8.6% moderately severe, and 6.9% reported severe symptoms. For the second dose, 25.9% reported no symptoms, 32.8% mild, 29.3% moderate, 6.9% moderately severe, and 5.2% severe symptoms.

Gender-based comparisons of symptom severity revealed no statistically significant association between gender and symptom burden following either dose. After the first dose, 37.5% of males and 23.3% of females reported no symptoms, whereas 25.0% of males and 48.3% of females reported moderate to severe symptoms. Chi-square analysis showed no significant difference between genders (χ2(4) = 3.856, p = 0.426). Similarly, after the second dose, 30.4% of males and 21.7% of females reported no symptoms, while 34.8% of males and 51.7% of females reported moderate to severe symptoms. Again, the difference was not statistically significant (χ2(4) = 2.298, p = 0.682). These findings suggest a consistent adverse event profile across both vaccine doses, with a noteworthy prevalence of audiological symptoms, particularly tinnitus, and similar symptom severity distributions between male and female participants.

Table 2.

Symptom severity stratified by dose and gender.

Table 2.

Symptom severity stratified by dose and gender.

| Severity Level |

Dose 1 Male |

Dose 1 Female |

Dose 2 Male |

Dose 2 Female |

| No symptoms |

21 |

14 |

17 |

13 |

| Mild |

17 |

17 |

16 |

22 |

| Moderate |

11 |

18 |

13 |

21 |

| Moderately severe |

4 |

6 |

2 |

6 |

| Severe |

3 |

5 |

2 |

4 |

3.5. Tinnitus Onset Following COVID-19 Vaccination

Out of 189 participants who provided valid responses, 49 individuals (25.9%) reported the onset of tinnitus following the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, while 140 participants (74.1%) did not experience tinnitus onset at that time. For the second dose, 116 participants responded to the relevant question. Among them, 37 participants (31.9%) reported developing tinnitus after receiving the second dose, while 79 participants (68.1%) did not. Notably, 73 participants did not respond to this item, resulting in missing data for a significant portion of the sample.

3.6. COVID-19 Infection Status and Timing Relative to Vaccination

Among all 189 respondents, 34 participants (18.0%) reported being infected with COVID-19 prior to receiving any vaccination. The remaining 155 participants (82.0%) reported no history of infection prior to their initial vaccine dose. In the subgroup who received more than one vaccination, 43 participants (22.8%) reported testing positive for COVID-19 between vaccine doses, while 146 participants (77.2%) did not experience infection in that interval.

3.7. COVID-19-Related Hospitalization

Of the 189 total participants, 137 provided responses to the question about COVID-19-related hospitalization. Only one participant (0.7%) reported being hospitalized due to COVID-19, while 136 participants (99.3%) indicated they were not hospitalized. Fifty-two participants (27.5%) did not respond to this question. These findings suggest that severe COVID-19 outcomes requiring hospitalization were rare in this study cohort.

Table 3.

Summary of key binary outcomes reported by participants. Values indicate the number and percentage of participants who responded “Yes” or “No” to each item. Percentages for tinnitus after the second dose are based on the 116 participants who responded.

Table 3.

Summary of key binary outcomes reported by participants. Values indicate the number and percentage of participants who responded “Yes” or “No” to each item. Percentages for tinnitus after the second dose are based on the 116 participants who responded.

| Variable |

Yes (n, %) |

No (n, %) |

| Tinnitus after first dose |

49 (25.9%) |

140 (74.1%) |

| Tinnitus after second dose |

37 (19.6%)* |

79 (41.8%)* |

| COVID-19 infection prior to vaccination |

34 (18.0%) |

155 (82.0%) |

| COVID-19 positive between vaccine doses |

43 (22.8%) |

146 (77.2%) |

3.8. Longitudinal Changes in Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) Scores

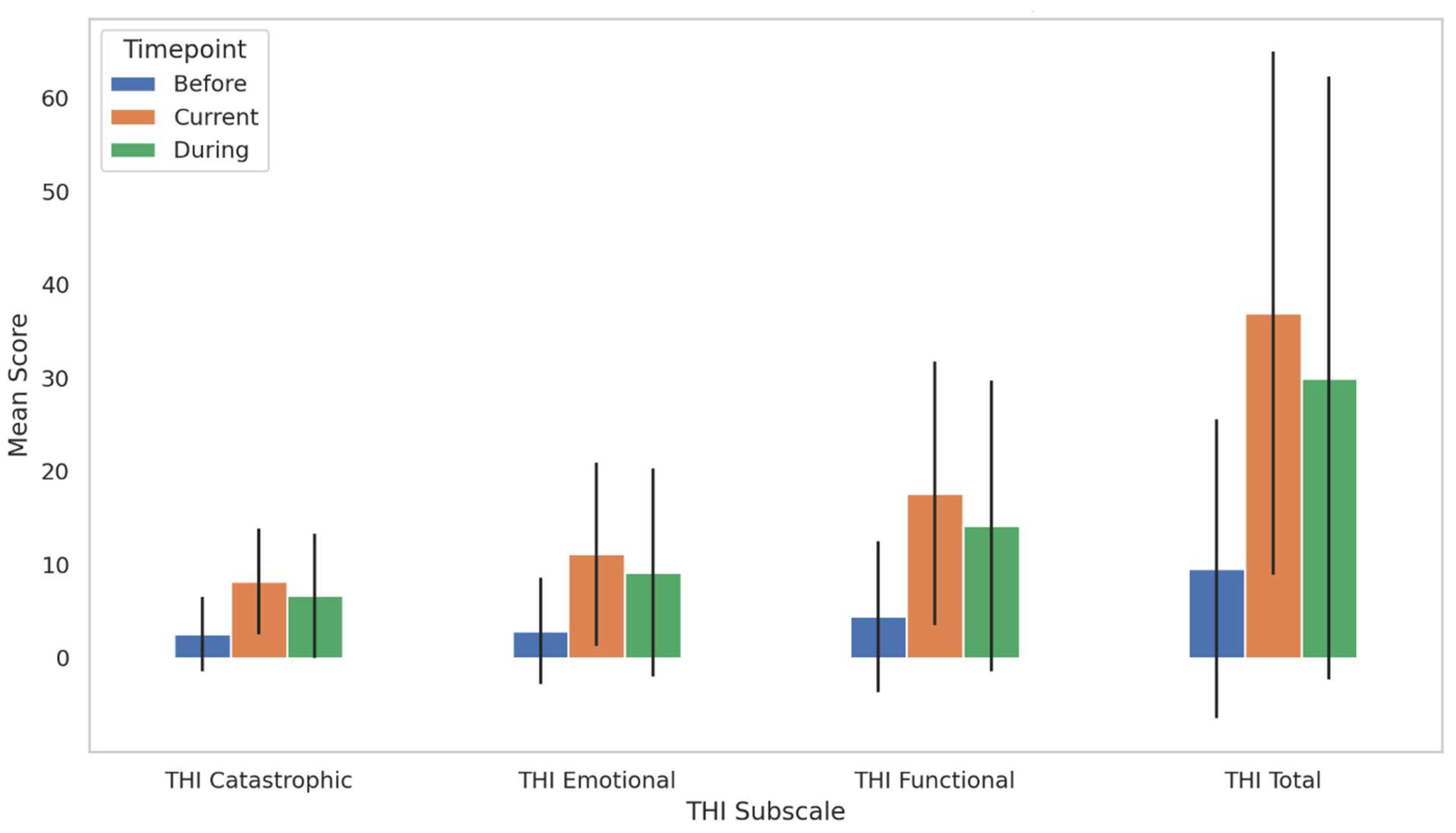

Repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine changes in tinnitus severity, as measured by the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), across three time points: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Mean THI scores increased progressively from before the pandemic (M = 9.57, SD = 16.00), to during the pandemic (M = 29.97, SD = 32.30), and further to the current point (M = 36.92, SD = 28.04). Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated a violation of the sphericity assumption (χ2 (2) = 13.46, p = 0.001), so the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time on THI scores, F(1.84,270.21) =69.74F(1.84, 270.21) = 69.74F(1.84,270.21) =69.74, p < 0.001, with a large effect size (partial η2 = 0.453). Post hoc pairwise comparisons (LSD adjusted) showed that THI scores were significantly higher during the pandemic compared to before (p < 0.001, mean difference = 20.41), and current scores were significantly higher than both during (p < 0.001, mean difference = 6.95) and before the pandemic (p < 0.001, mean difference = 27.35). These findings suggest a significant and sustained increase in tinnitus-related handicap over the course of the pandemic, with the highest burden reported at the time of survey.

Figure 5.

Bar plot illustrates the mean scores of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) total and subscale domains (Functional, Emotional, and Catastrophic) across three pandemic timepoints: before, during, and current. Error bars represent standard deviations. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed statistically significant increases in all subscale scores over time (p < .001), with pairwise comparisons indicating significant differences between each timepoint for all domains. These findings highlight a progressive and persistent increase in tinnitus severity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 5.

Bar plot illustrates the mean scores of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) total and subscale domains (Functional, Emotional, and Catastrophic) across three pandemic timepoints: before, during, and current. Error bars represent standard deviations. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed statistically significant increases in all subscale scores over time (p < .001), with pairwise comparisons indicating significant differences between each timepoint for all domains. These findings highlight a progressive and persistent increase in tinnitus severity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.8.1. THI Functional Subscale

Repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to evaluate changes in tinnitus-related functional difficulties (THI Functional subscale) across three time points: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Mean functional scores increased from 4.42 (SD = 8.11) before the pandemic, to 14.16 (SD = 15.58) during the pandemic, and to 17.62 (SD = 14.13) at the current time point. Mauchly’s test of sphericity was violated (W = 0.902, χ2(2) = 15.05, p < 0.001); therefore, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied. The repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time, F(1.82,267.77)=70.09F(1.82, 267.77) = 70.09F(1.82,267.77)=70.09, p < 0.001, with a large effect size (partial η2 = 0.444). Pairwise comparisons (LSD-adjusted) showed that functional scores were significantly higher during the pandemic compared to before (p < 0.001, mean difference = 9.74), and continued to rise significantly from during to the current time point (p < 0.001, mean difference = 3.46). These results suggest a progressive and statistically significant increase in functional tinnitus burden from pre-pandemic levels through the present.

3.8.2. THI Emotional Subscale

Repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to assess changes in emotional distress related to tinnitus (THI Emotional Subscale) across three time points: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Mean emotional scores increased from 2.88 (SD = 5.70) pre-pandemic to 9.16 (SD = 11.12) during the pandemic, and further to 11.11 (SD = 9.87) at the current time point. Mauchly’s test indicated a violation of sphericity (W = 0.897, χ2 (2) = 15.83, p < 0.001); therefore, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied. The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time, F(1.81,265.53) =52.77F(1.81, 265.53) = 52.77F(1.81,265.53) =52.77, p < 0.001, with a large effect size (partial η2 = 0.264). Post hoc pairwise comparisons (LSD-adjusted) indicated significant increases in emotional subscale scores from before to during the pandemic (p < 0.001), from before to current (p < 0.001), and from during to current (p = 0.006). These findings demonstrate a progressive and statistically significant increase in tinnitus-related emotional distress, with the highest levels reported at the time of the survey.

3.8.3. THI Catastrophic Subscale

Repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine changes in catastrophic responses to tinnitus (THI Catastrophic Subscale) across three times: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The mean scores increased from 2.55 (SD = 3.97) before the pandemic, to 6.65 (SD = 6.63) during the pandemic, and further to 8.19 (SD = 5.67) at the current time. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was met, χ2(2) = 5.70, p = 0.058; therefore, sphericity was assumed. The repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect of time on catastrophic scores, F (2,294)=66.11F(2, 294) = 66.11F(2,294) =66.11, p < 0.001, with a large effect size (partial η2 = 0.310). Post hoc pairwise comparisons (LSD-adjusted) indicated that catastrophic scores significantly increased from before to during (p < 0.001, mean difference = 4.10), from before to current (p < 0.001, mean difference = 5.64), and from during to current (p = 0.001, mean difference = 1.54). These results highlight a statistically significant escalation in catastrophic tinnitus reactions during and after the pandemic period, with the highest scores observed at the time of survey.

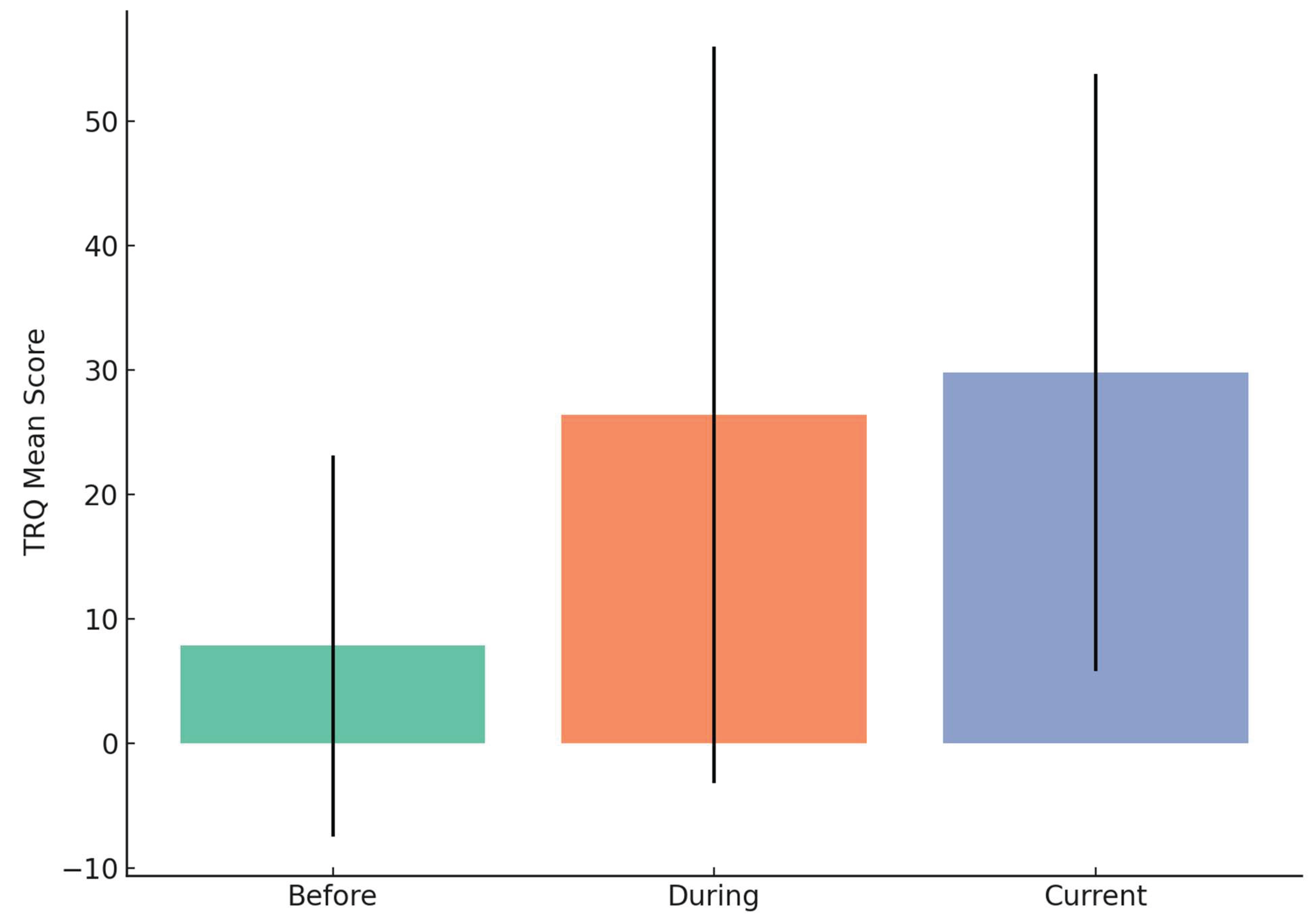

3.9. Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ)

To assess tinnitus-related distress over time, participants completed the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) at three time points: prior to COVID-19 vaccination (“Before”), during the vaccination period (“During”), and at the time of survey completion (“Current”). Descriptive statistics and visual inspection of score distributions revealed meaningful changes across these points.

The mean TRQ score prior to vaccination was 9.96 (SD = 15.01), indicating minimal tinnitus-related distress for most participants. During the vaccination period, TRQ scores increased significantly, with a mean of 29.74 (SD = 28.46). This marked increase reflects a subset of participants experiencing the onset or exacerbation of tinnitus-related symptoms during this period. At the time of the survey (Current), the mean TRQ score remained elevated at 29.75 (SD = 26.97), which suggested persistent distress in a subgroup of participants. A repeated-measures ANOVA confirmed a statistically significant effect of time on TRQ scores, F (2, 212) = 65.74, p < .001, with pairwise comparisons indicating significant increases from Before to During (p < .001) and Before to Current (p < .001), but no significant change from During to Current (p = .995). This pattern suggests that tinnitus distress worsened during the vaccination period and remained elevated at the time of data collection.

These findings provide empirical support for a potential link between the COVID-19 vaccination period and increased tinnitus-related distress in a subset of individuals.

Figure 6.

Mean Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) scores before, during, and after the COVID-19 vaccination period. Error bars represent standard deviations. A notable increase in tinnitus-related distress is observed from the pre-vaccination period to the cur.

Figure 6.

Mean Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) scores before, during, and after the COVID-19 vaccination period. Error bars represent standard deviations. A notable increase in tinnitus-related distress is observed from the pre-vaccination period to the cur.

TRQ Severity Levels Across Timepoints

The distribution of tinnitus-related distress, as assessed by the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) severity levels, showed notable changes across the three assessed timepoints: before, during, and at the time of survey completion (“current”). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of participants (81.3%, n = 87) fell within the “No/Slight” severity category, indicating minimal tinnitus-related distress. Only small proportions reported mild (13.1%, n = 14), moderate (3.7%, n = 4), severe (0.9%, n = 1), or very severe distress (0.9%, n = 1).

During the pandemic, a shift toward greater severity was observed. The proportion of participants in the “No/Slight” category decreased to 51.4% (n = 55), while increases were seen in mild (19.6%, n = 21), moderate (11.2%, n = 12), severe (6.5%, n = 7), and very severe (11.2%, n = 12) categories.

At the time of the survey (“current”), the proportion in the “No/Slight” category further declined to 33.6% (n = 36). The number of participants reporting mild (33.6%, n = 36) and moderate (16.8%, n = 18) severity increased, and severe (10.3%, n = 11) and very severe (5.6%, n = 6) cases remained notable. These results indicate a progressive increase in tinnitus-related distress throughout the pandemic period, with a substantial shift from lower to higher severity categories.

Table 4.

Distribution of Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) Severity Levels Across Three Timepoints: Before, During, and Current.

Table 4.

Distribution of Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) Severity Levels Across Three Timepoints: Before, During, and Current.

| TRQ severity levels |

Before |

During |

Current |

| No/Slight |

87 |

55 |

36 |

| Mild |

14 |

21 |

36 |

| Moderate |

4 |

12 |

18 |

| Severe |

1 |

7 |

11 |

| Very Severe |

1 |

12 |

6 |

4. Discussion

This study offers a comprehensive examination of the longitudinal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent vaccination on tinnitus-related distress and severity, as measured by the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) and Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ). Our results indicate a significant and sustained increase in tinnitus burden from pre-pandemic to the present timepoint, with all THI subscales functional, emotional, and catastrophic demonstrating progressive and statistically significant elevations. Repeated measures ANOVAs revealed large effect sizes, highlighting the clinical relevance of these shifts.

Changes in TRQ severity classifications were particularly striking: the proportion of participants experiencing moderate or greater tinnitus-related distress tripled from baseline to the current timepoint. These findings are consistent with prior studies reporting an exacerbation of tinnitus symptoms during the pandemic (Beukes et al., 2021; Viola et al., 2022), and may reflect the compounded effects of psychosocial stress, isolation, and disruptions to routine healthcare access.

We also identified notable patterns related to COVID-19 vaccination. New-onset or worsening tinnitus temporally associated with vaccination was reported by 25.9% of participants after the first dose and 31.9% after the second dose. These rates are consistent with emerging literature (Formeister et al., 2022; Yellamsetty et al., 2023; Yellamsetty et al., 2024a; Bao et al., 2024) and underscore the importance of continued monitoring. While causality cannot be inferred from our observational design, the temporal associations particularly among individuals with preexisting metabolic conditions merit further investigation into potential biological and psychological mechanisms (Bao et al., 2024).

Interestingly, gender-based analyses did not reveal statistically significant differences in symptom severity or trajectory post-vaccination. This finding aligns with the work of Crossley et al. (2021), who similarly found no sex-based differences in auditory outcomes in post-viral populations, suggesting that gender may not be a key moderator in vaccination-related tinnitus onset or distress.

The observed increase in TRQ scores over time lends support to cognitive-emotional models of tinnitus, such as the framework proposed by Tyler et al. (2008), which emphasizes the role of anxiety, attention, and rumination in tinnitus-related distress. These findings reaffirm the value of the biopsychosocial model in clinical tinnitus management and highlight the importance of integrating mental health screening and psychological support into standard audiological care.

Moreover, our results contribute to the growing body of literature identifying strong associations between tinnitus and mental health challenges, particularly during global crises. Jiang et al. (2025) recently demonstrated robust links between tinnitus severity and depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation. Their findings of altered limbic activity and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis provide a plausible neurobiological basis for the sustained increases in tinnitus distress observed in our cohort.

5. Conclusions

This study provides robust evidence of the sustained and multifactorial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination on tinnitus severity and distress. The observed increases in THI and TRQ scores from pre-pandemic to current timepoints underscore the importance of addressing both the auditory and psychological dimensions of tinnitus within clinical care. The substantial proportion of participants reporting new-onset or worsened tinnitus symptoms following COVID-19 vaccination further emphasizes the need for ongoing monitoring and clear, evidence-based communication with patients.

Our findings support the biopsychosocial model of tinnitus, highlighting how stress, isolation, and reduced healthcare access may amplify tinnitus-related burden. Importantly, they reinforce the need for interdisciplinary approaches that integrate audiologic management with mental health screening and psychological support.

6. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study’s observational design precludes causal inference between COVID-19 vaccination and tinnitus onset or exacerbation. Second, all data were self-reported, which may introduce recall bias or reporting inaccuracies, particularly regarding symptom onset and severity. Third, the lack of audiometric or neurophysiological data limits our ability to objectively verify changes in hearing or tinnitus perception. Additionally, while the sample was demographically diverse, it may not be representative of the broader population, potentially limiting generalizability. Finally, mental health variables such as anxiety or depression were not directly measured and should be considered in future research.

7. Future Directions

Future studies should aim to clarify the biological and neuropsychological mechanisms linking vaccination, pandemic-related stress, and tinnitus. This includes examining the role of pre-existing metabolic or psychological vulnerabilities and potential involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Longitudinal cohort studies incorporating objective audiological assessments, biomarkers of stress and inflammation, and validated mental health measures are warranted. Additionally, randomized controlled trials evaluating integrated interventions such as tinnitus retraining therapy combined with cognitive-behavioral or stress-reduction strategies may inform best practices in managing tinnitus in post-pandemic clinical settings.

Ethics Statement

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) in compliance with ethical guidelines at San Jose State University.

Declaration of the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Manuscript Preparation

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-4), were utilized during the preparation of this manuscript to assist with language editing, grammar refinement, and organization of scientific text. The use of AI was limited to enhancing readability and did not involve the generation of original scientific ideas, data analysis, or interpretation of findings. All content was critically reviewed, revised, and approved by the authors to ensure scientific integrity and compliance with ethical publication standards.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

None.

References

- Aydogan, Z., Can, M., Soylemez, E., Karakoc, K., Buyukatalay, Z. C., & Tokgoz Yilmaz, S. (2024). The effects of COVID-19 on tinnitus severity and quality of life in individuals with subjective tinnitus. Brain and Behavior, 14(3), e7031. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Yellamsetty, A., Edmonds, R. M., Barcavage, S. R., & Bao, S. (2024). COVID-19 vaccination-related tinnitus is associated with pre-vaccination metabolic disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 15, 1374320. [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E. W., Baguley, D. M., Jacquemin, L., Lourenco, M. P., & Manchaiah, V. (2020). Changes in tinnitus experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 592878. [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E., Ulep, A. J., Eubank, T., & Manchaiah, V. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 and the pandemic on tinnitus: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(13), 2763. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, W., Gulati, G., & Kelly, B. D. (2020). Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(5), 311–312. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Li, P., Huang, X., Liu, Y., Mao, S., Yin, H., Wang, N., Luo, Y., & Sun, S. (2024). Exploring the prevalence of tinnitus and ear-related symptoms in China after the COVID-19 pandemic: Online cross-sectional survey. JMIR Formative Research, 8, e54326. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, V., Wilson, C., & Stephens, D. (2004). Quality of life and tinnitus. Audiological Medicine, 2(1), 29–40.

- Mazurek, B., Szczepek, A. J., & Hébert, S. (2015). Stress and tinnitus. HNO, 63(4), 258–265. [CrossRef]

- Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 122(2), 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2020). Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y., Jain, N., Kim, G., & Husain, F. T. (2024). Tinnitus and COVID-19: Effect of infection, vaccination, and the pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1508607. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. (2019). The psychology of pandemics: Preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020). Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 72, 102232. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. (2022). The psychology of pandemics. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 581–609. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P. H., Henry, J., Bowen, M., & Haralambous, G. (1991). Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire: Psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34(1), 197–201.

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. [CrossRef]

-

Yellamsetty, A., Etu, E.-E., & Bao, S. (2025). Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on tinnitus onset and severity: A comprehensive survey study. Frontiers in Audiology and Otology, 3, Article 1509444. [CrossRef]

- Yellamsetty, A. (2024a). COVID-19 vaccination effects on tinnitus and hyperacusis: Longitudinal case study. The International Tinnitus Journal, 27(2), 253–258. [CrossRef]

- Yellamsetty, A., Fortuna, G., Egbe-Etu, E., & Bao, S. (Submitted). Functional and perceptual impacts of tinnitus following COVID-19 vaccination: Implications for public health surveillance and communication. Frontiers in Audiology and Otology.

- Nieminen TA, Kivekäs I, Artama M, Nohynek H, Kujansivu J, Hovi P. (2023). Sudden hearing loss following vaccination against COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 149(2), 133–140. [CrossRef]

- Yanir Y, Doweck I, Shibli R, Najjar-Debbiny R, Saliba W. (2022). Association between the BNT162b2 messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccine and the risk of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 148(4), 299–306. [CrossRef]

- Leong, S., Teh, B., & Kim, A. H. (2023). Characterization of otologic symptoms appearing after COVID-19 vaccination. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 44(2), 103725. [CrossRef]

- Frontera, J. A., Tamborska, A. A., Doheim, M. F., Garcia-Azorin, D., Gezegen, H., Guekht, A., Khan Yusof Khan, A. H., Santacatterina, M., Sejvar, J., Thakur, K. T., Westenberg, E., Winkler, A. S., Beghi, E., & contributors from the Global COVID-19 Neuro Research Coalition. (2022). Neurological events reported after COVID-19 vaccines: An analysis of VAERS. Annals of Neurology, 91(6), 756–771. [CrossRef]

- Formeister EJ, Wu MJ, Chari DA, et al. (2022). Assessment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss after COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 148(4), 307–315. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker HR, Gulea C, Koteci A, et al. (2021). GP consultation rates for sequelae after acute COVID-19 in patients managed in the community or hospital in the UK: Population-based study. BMJ, 375, e065834. [CrossRef]

- Kant A, Jansen J, van Balveren L, van Hunsel F. (2022). Description of frequencies of reported adverse events following immunization among four different COVID-19 vaccine brands. Drug Safety, 45(4), 319–331. [CrossRef]

- Dorney I, Bobak L, Otteson T, Kaelber DC. (2023). Prevalence of new-onset tinnitus after COVID-19 vaccination with comparison to other vaccinations. Laryngoscope, 133(7), 1722–1725. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).