1. Introduction

Climate change has emerged as a major global threat to food systems [

1]. The global average temperature has increased by approximately 1.2°C since pre-industrial times, with projections indicating that between 2030 and 2052 the temperature might increase 1.5°C, causing more frequent climate extremes, such as floods, droughts, and cyclones [

2,

3,

4]. The impacts of these climate events are particularly severe in Sub-Saharan Africa, where over 80% of the people rely on rainfed agriculture, but adaptive capacity is constrained by persistent socio-economic challenges [

5]. Mozambique stands out as one of the most vulnerable countries to extreme climate events in the region [

6]. Over the past two decades, it has been repeatedly affected by climate-related disasters [

6,

7]. Notably, Tropical Cyclones Idai (2019) and Freddy (2023) displaced more than two million people and caused damages exceeding USD 3.3 billion [

8]. In the country’s southern provinces (Maputo, Gaza, and Inhambane), prolonged droughts have become more recurrent, exacerbating food insecurity and threatening the sustainability of agricultural livelihoods [

9].

Given the increasing climatic frequency and severity of dry periods, smallholder farmers in southern Mozambique are adopting diverse strategies to cope with and adapt to drought conditions [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Among these, conservation practices (CP), including both, recently introduced climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices and locally grounded indigenous knowledge (IK), are gaining recognition for their potential to build long-term resilience [

13,

14,

15]. Studies in the region report the use of drought-tolerant crop varieties, minimum tillage, intercropping, mulching, improved soil and water management, and traditional forecasting methods as part of local adaptive strategies [

13,

14,

16,

17]. These approaches, while contextually relevant and often low-cost, are not always well-documented or systematically assessed in terms of their efficacy, coverage, or constraints [

18].

Although empirical studies on drought adaptation among smallholder farmers are increasing, major knowledge gaps persist. First, there is a limited understanding of how conservation practices are implemented on the ground, and to what extent their adoption has contributed to tangible improvements in drought resilience and yield gain [

14,

18,

19]. Second, the integration of indigenous and scientific knowledge systems, despite being widely advocated, is rarely operationalized in practice or evaluated in terms of complementarities and limitations [

20,

21]. Third, barriers to adoption, including access to land, credit, extension services, decision-making dynamics within households, and institutional support mechanisms, are often mentioned but not systematically analyzed or synthesized [

11,

14,

22]. This review, therefore, seeks to consolidate fragmented insights into a holistic overview of conservation practices and their adoption barriers, with a focus on enhancing drought resilience in southern Mozambique.

To guide this analysis, the review adopts a conceptual framework that defines conservation practices (CPs) as both climate-smart agriculture (CSA) and indigenous knowledge systems [

23]. Moreover, the analysis of the literature is guided by two frameworks: (i) Resilience Thinking Framework, which assesses how these practices strengthen farmers’ capacity to absorb, adapt, and transform under recurrent droughts [

24,

25], and (ii) Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) to assess the barriers to their adoption [

26]. The purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize the available evidence on conservation practices used by smallholder farmers in southern Mozambique to address climate-driven droughts. Specifically, it aims to: (i) describe the conservation practices employed in response to climate-driven droughts; (ii) assess the effectiveness of these practices in enhancing resilience in rainfed agricultural systems; and (iii) identify the main barriers limiting their adoption.

Accordingly, the review is guided by two major research questions:

What conservation practices are used by smallholder farmers in response to climate change- and variability-induced droughts in southern Mozambique, and how effective are they?

What barriers hinder the adoption of these practices, and what gaps remain in the literature?

Based on the existing evidence, the review is also framed by the following conceptual hypothesis: (i) Conservation practices, including CSA techniques and indigenous knowledge systems, contribute to improved drought resilience among smallholder farmers in southern Mozambique.

2. Materials and Methods

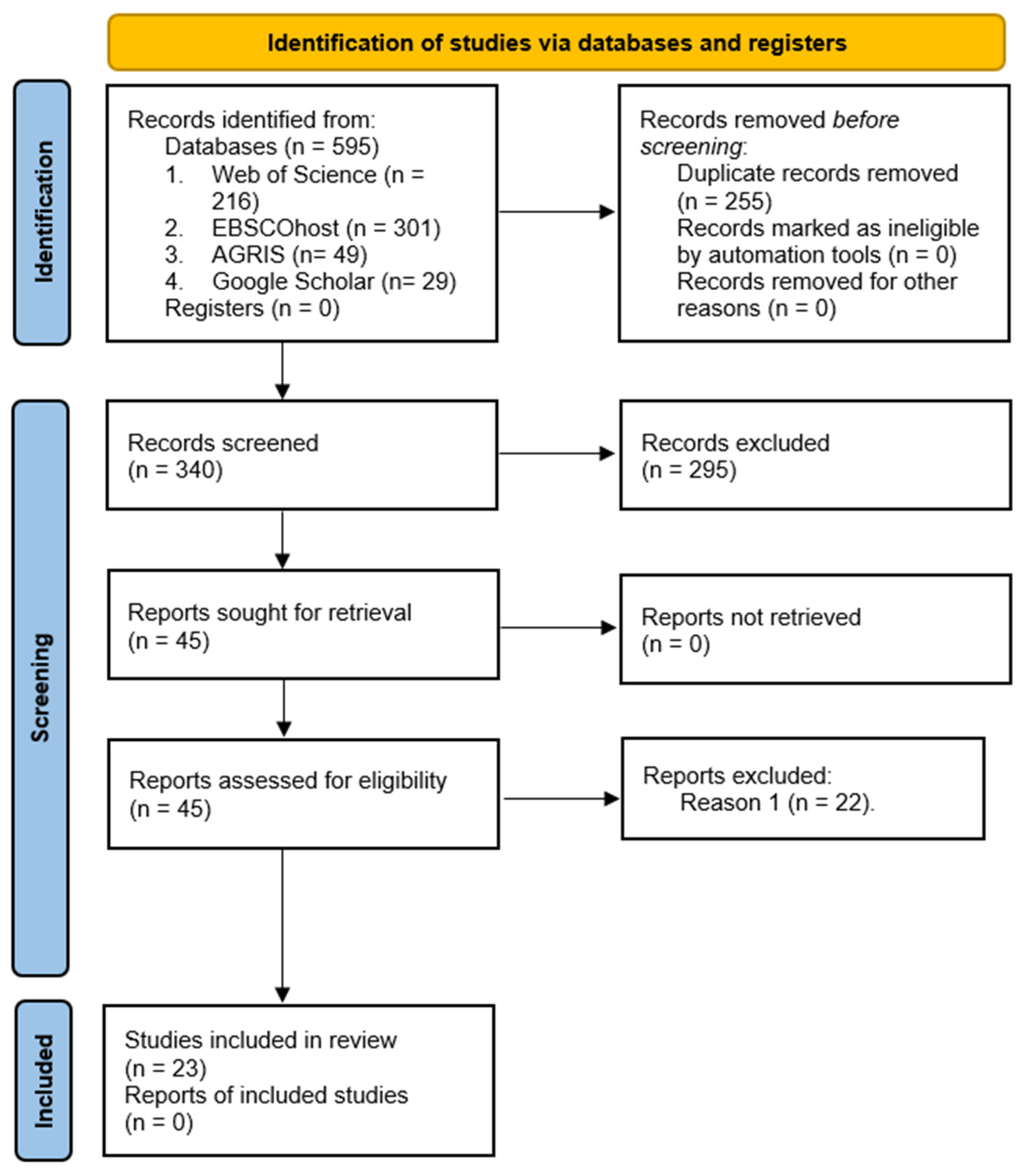

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines [

68]. The review protocol was structured around four stages: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion.

2.1. Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted in four databases: Web of Science, EBSCOhost, AGRIS, and Google Scholar. Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to combine search terms, and the complete search strings are presented in

Table 1. The same Boolean structure was applied across all databases, with minor syntax adjustments where required. Searches were limited to publications between January 2000 and April 2025 and included studies published in English and Portuguese.

2.2. Screening Process

The selection of studies followed a structured four-stage screening process, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The initial stage, “Identification”, identified a total of 595 records: 301 from EBSCOhost, 216 from Web of Science, 49 from AGRIS, and 29 from Google Scholar. Following identification, the second stage, “Screening”, started with the removal of duplicate records. A total of 255 duplicated entries were identified among the four databases and excluded, leaving 340 unique studies. The number of records retained after duplication check was as follows: EBSCOhost (n = 172), Web of Science (n = 123), AGRIS (n = 28), and Google Scholar (n = 17). In the next screening phase, studies were assessed based on their geographic and thematic relevance. This involved the review of titles and abstracts to determine whether the studies (i) had been conducted in southern Mozambique, and (ii) focused on conservation practices in response to drought. Studies that did not meet these conditions, such as those focused on other climate hazards (e.g., floods or cyclones), conducted outside the study region were excluded. This step reduced the number of potentially eligible studies to 45, distributed as follows: EBSCOhost (n = 23), Web of Science (n = 16), AGRIS (n = 4), and Google Scholar (n = 2). The third stage, “Eligibility”, focused on evaluating the academic quality and publication credibility of the remaining records. To maintain scientific rigor and ensure the reliability of evidence, only studies published in peer-reviewed journals with established academic standards were retained. After applying this filter, 23 studies remained eligible: 12 from EBSCOhost, 7 from Web of Science, 2 from AGRIS, and 2 from Google Scholar.

For the final stage, “Included”, these 23 articles were then subjected to a full-text reading and critical appraisal process to confirm their alignment with the review’s inclusion criteria. Each article was carefully examined to verify that it presented original empirical evidence, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods, on the use of conservation practices by smallholder farmers in the context of drought adaptation in southern Mozambique.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure the scientific integrity and contextual relevance of this systematic review, a clear set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was established as shown in

Table 2. These criteria were applied throughout the screening process to filter studies based on PRISMA 2020. In terms of publication, only studies published between 2000 and April 2025 were considered. Eligible publications had to be peer-reviewed and written in either English or Portuguese. Studies falling outside this scope, including those not subject to academic peer review or published in grey literature such as reports, proceedings, or non-indexed sources, were excluded. Regarding the type of data, the review prioritized studies that presented original empirical evidence, whether derived from qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods research designs.

The geographic scope was limited to studies conducted in southern Mozambique. This region was selected due to its high exposure to climate-driven drought and the predominance of smallholder agricultural systems that manage areas ranging from less than 1 hectare to 10 hectares [

69]. Studies carried out in other parts of Mozambique or in different regions were not considered. In terms of thematic relevance, the central focus of the study had to be on adaptation strategies but were not limited to soil and water conservation techniques, reduced or zero tillage, agroforestry, drought-resistant crop varieties, and traditional integrated farming systems. Studies that focused on non-agricultural domains, large-scale commercial farms, or contexts unrelated to smallholder agriculture were excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, research addressing other climatic threats, such as floods or cyclones, without reference to drought-specific responses, was not eligible for inclusion.

Two reviewers independently screened all studies using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until agreement on study eligibility was achieved.

2.4. Data Extraction

A structured data extraction process was implemented using Microsoft Excel, Zotero and SciSpace Softwares, to ensure consistency across all included studies, as shown in

Table 3. For each article, a set of predefined data fields was used to capture relevant information systematically [

68]. This included bibliographic details such as the article ID, authors, year of publication, title, journal or source, and full reference. Contextual information such as the geographic location within southern Mozambique, study population, language, study design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), sample size, and data collection methods was also recorded.

The extraction focused on whether the study described climate conditions, with specific attention to rainfall and temperature trends where applicable. It was also noted whether the article addressed crops, and, if so, the names of those crops. A key component of the extraction involved identifying and detailing conservation practices, including techniques such as minimum tillage, cover cropping or mulching, soil microbiology, crop diversification, intercropping, crop rotation, drought-tolerant varieties, agroforestry, and traditional practices. Any additional adaptation practices mentioned outside these categories were also considered.

Furthermore, information was gathered on whether the effectiveness of the reported practices was discussed, along with any evidence of outcomes such as improved yields or soil quality. The presence and nature of barriers to adoption were noted, including economic, institutional, or social constraints. Each study’s relevance to the research questions was assessed, and key findings, author-identified gaps, study limitations, and funding sources were recorded. All extracted data were organized into a spreadsheet titled “Extracted Data,” serving as a foundational resource for subsequent synthesis.

2.5. Quality Assessment and Data Analysis

Data analysis combined quantitative and qualitative approaches done in Microsoft Excel and NVivo 15 tool. In Excel, frequencies and percentages were calculated to summarize study characteristics and adoption rates of conservation practices, with outputs organized in Tables and Figures. NVivo 15 supported thematic coding of full texts, allowing the identification and categorization of adaptation practices, barriers and study limitations.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Selected Studies

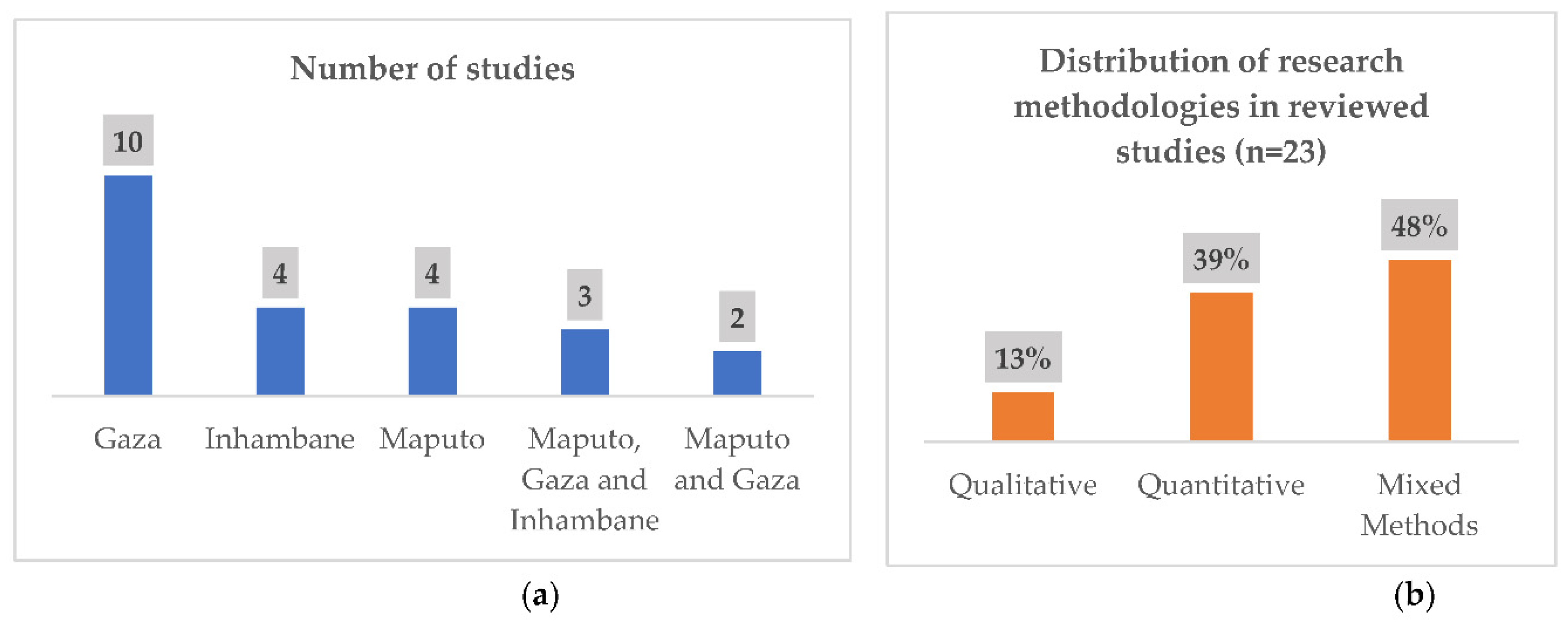

Figure 2 summarizes the geographic and methodological distribution of the 23 studies included in this systematic review. As shown in

Figure 2a, most of the studies were conducted in Gaza province (n = 10), followed by Maputo (n = 4), Inhambane (n = 4), multi-province studies covering Maputo, Gaza, and Inhambane (n = 3), and two (n= 2) studies focusing on Maputo and Gaza. The dominance of Gaza may reflect its high agricultural vulnerability, particularly in arid and semi-arid districts of Guijá, Mapai, Mabalane, Chicualacuala, Chigubo, Massingir, Massangena located in this province. These district’s rainfall ranges from 400 mm to 615 mm per year and [

27,

28] is highly irregular and intermittent. These conditions might have made Gaza a hotspot for interventions and academic research on climate resilience. In contrast, Inhambane, despite having an extended arid and semi-arid areas in the northern region (Funhalouro, Mabote, Pande districts), remains underrepresented in the literature, suggesting spatial research gaps in southern Mozambique that warrant further attention.

In general, in these three provinces (Maputo, Gaza and Inhambane), the precipitation often falls in a few intense events separated by long dry spells, leading to intermittent droughts and, in some years, premature cessation of the rainy season, resulting in seasonal droughts [

70]. These droughts coincide with the critical flowering and grain-filling stages of staple crops grown by smallholder farmers such as maize, cowpea, groundnut amongst others causing substantial yield losses [

71]. Water deficits are further aggravated by annual evapotranspiration (1,000–1,300 mm) that exceeds rainfall in most districts, driven by rising mean temperatures (up to +1 °C above the 1950–2019 average), strong winds, and high solar radiation [

71,

72].

On the other hand,

Figure 2b shows that mixed-methods approaches (quantitative and qualitative) are the most frequently used, accounting for 48% of the reviewed studies. These studies typically combined surveys, focus group discussions (FGDs), and interviews with key informants to explore both technical and socio-cultural dimensions of drought resilience. For example, [

13] employed 200 open-ended questionnaires, 25 FGDs, and 17 interviews to examine drought perceptions in Gaza, while [

29] combined surveys and FGDs to understand information sharing in climate adaptation. Quantitative studies made up 39% of the total and were characterized by experimental trials (e.g., maize genotype and soil property assessments), structured household surveys (e.g., with 122 or 616 farmers), and statistical modeling. Qualitative studies were the least represented (13%) and were mostly literature-based or stakeholder-driven.

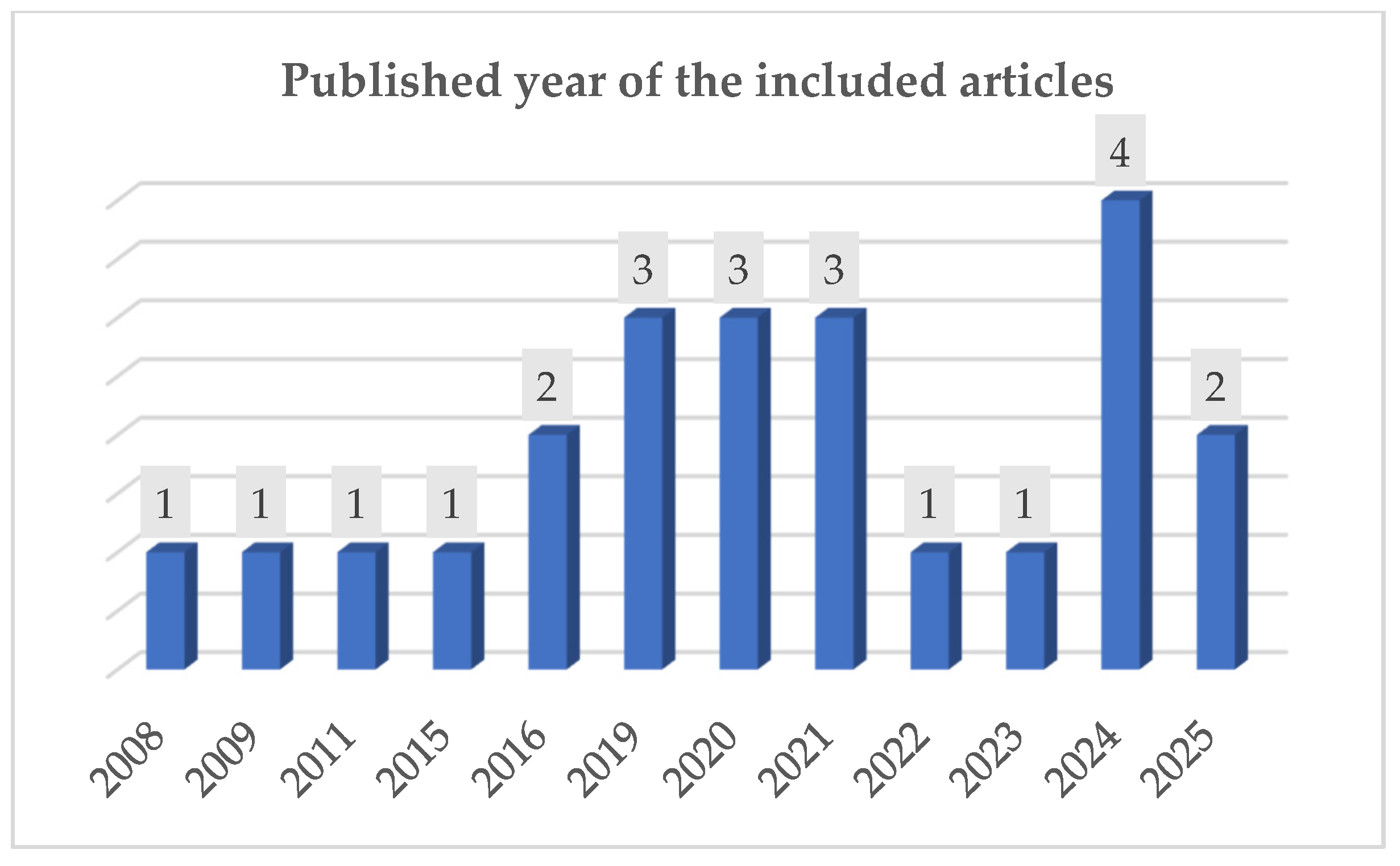

In terms of publication timeline,

Figure 3 shows the year of publication of the 23 included articles. The distribution reveals a growing interest in research on climate resilience and sustainable agriculture in southern Mozambique in recent years. Most studies were published in 2024 (n = 4), and between 2019 and 2021, with three studies published each year. In contrast, earlier years such as 2008 to 2015 show only sporadic publications, one article each year, suggesting that scholarly engagement with the topic was still emerging during that time. The number of studies declined slightly in 2022 and 2023, with only one publication per year, most likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to movement restrictions between 2020 and 2023. However, interest appears to have resumed in 2025 (n = 2).

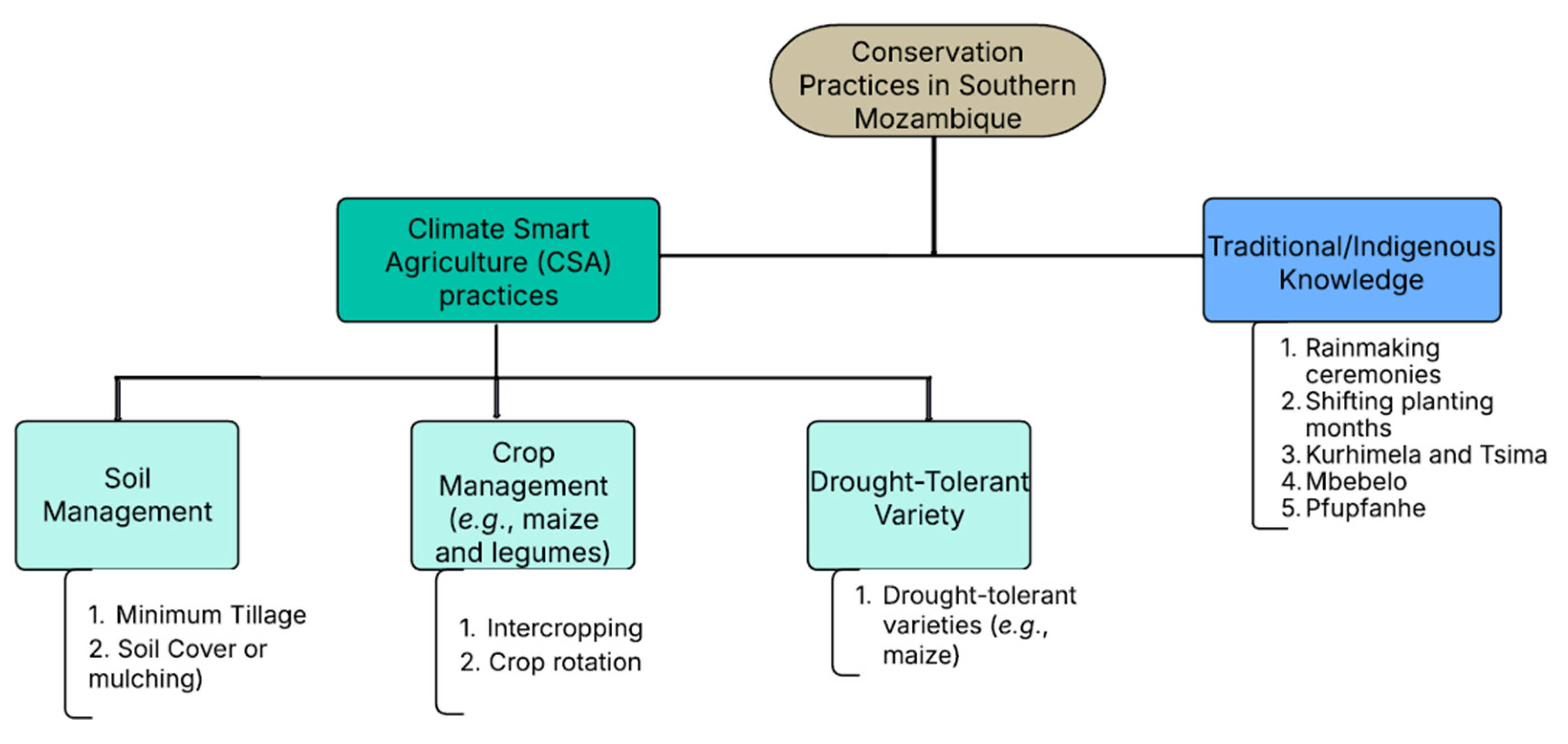

3.3. Description of Conservation Practices in Southern Mozambique and Their Effectiveness

Figure 4 illustrates the integration of CSA practices and Traditional/Indigenous Knowledge as key components of conservation practices in southern Mozambique used by smallholder farmers.

These practices are implemented with the common goal of enhancing the resilience of smallholder farmers to recurrent climate-induced droughts.

3.3.1. Soil Management

Table 5 presents the Soil management practices (minimum tillage and soil cover) implemented in southern Mozambique. Experimental evidence in the region (Maputo, Gaza and Inhambane provinces) indicates that minimum tillage (MT) reduces soil evaporation, increases infiltration, and enhances soil water storage through greater residue cover and organic matter accumulation [

15]. These improvements are reflected in higher crop performance, with maize yields reported to be higher in 89% of cases and legume yields in 90% under MT relative to conventional tillage (CT) [

15,

30]. Localized trials further demonstrated that MT practices with tools such as basin planting and Jab planters increased maize yields by 13.7% and 11%, respectively, in comparison with CT systems [

27,

31]. Despite these biophysical benefits, MT adoption in southern Mozambique is strikingly limited. The review showed adoption rates of only 16% in Inhambane and 7% in Gaza, with CT still dominating at 75–100% of farmers across key districts [

27,

31]. The persistence of CT reflects its customary use of the short-handled hoe in subsistence farming, the availability of animal traction, and its ability to quickly prepare land under rainfed conditions. However, this reliance increases vulnerability, as CT accelerates SOC loss, reduces infiltration, and lowers drought resilience, often resulting in yield decline [

31,

32].

The productivity impact of MT is also strongly site-specific. In semi-arid Malawi, MT basins increased maize yields by up to 95% under rainfall below 700 mm, outperforming jab planters and dibble sticks [

33]. However, contrast emerges in wetter agro-ecologies, trials in Salima (Malawi) and Angonia (Mozambique) showed no yield advantages under MT due to waterlogging and nutrient leaching [

33,

34,

35]. Similarly, in Gaza province, extreme drought years led to crop failure regardless of tillage type, illustrating that while MT can mitigate moderate climatic stress, it can-not eliminate vulnerability under severe rainfall deficits [

31].These findings underline that MT’s efficacy under controlled trials does not always translate into effectiveness under heterogeneous smallholder conditions.

This study also revealed that soil cover practices, particularly mulching and residue retention, are more widely adopted in southern Mozambique than MT, and represent a cornerstone of CSA strategies in the region. Approximately 60% of smallholders reported maintaining crop residues on their fields, making this one of the most common soil management practices [

27,

31]. Evidence indicates that residue retention improves infiltration, reduces runoff, and enhances soil organic matter, resulting in maize yield gains ranging between 24% and 59% across different studies [

33,

35]. Comparatively, in Zimbabwe, adoption rates remain much lower, as residues are more commonly diverted for livestock feed [

32]. This contrast highlights that while residue retention is widely practiced in Mozambique, competing demands for biomass elsewhere in southern Africa limit its adoption.

However, despite relatively higher uptake, residue retention in Mozambique is rarely implemented at the recommended threshold of ≥30% cover. Competing uses of crop residues for livestock feed, fuel, and construction limit their availability for mulching [

31]. Moreover, the review found that in many cases residues are applied inconsistently, reducing their effectiveness in sustaining long-term soil fertility and yield stability. The minimum residue level required to achieve benefits remains contested, with some studies showing that sub-threshold coverage provides limited drought mitigation [

33,

35].

Long-term trials in Mozambique demonstrated that residue retention improves SOC, infiltration, and resilience after five or more years [

27,

32] . However, similar to evidence from Malawi and Zimbabwe, short-term results often show little or no yield advantage in the first years of adoption [

33,

34,

35]. This temporal lag undermines farmer motivation in subsistence contexts where immediate food security needs are paramount. Nevertheless, survey data revealed that in Mozambique, CSA adoption that included mulching significantly improved household Food Consumption Scores (+5.486

1, p < 0.1), unlike in Zimbabwe and Malawi, where incomplete adoption and small land areas prevented significant impacts [

32]. This alignment suggests that when consistently applied and integrated with complementary practices, mulching contributes not only to yield gains but also to improved food security, although the magnitude of benefits depends on both - ecological conditions and socio-economic contexts.

Table 4.

Soil management practices implemented in southern Mozambique.

Table 4.

Soil management practices implemented in southern Mozambique.

| Category |

Conservation practice - CSA |

Type |

Description |

Impact/Result |

Adoption of smallholders’ farmers |

Citation |

| Soil Management |

Minimum Tillage vs Conventional Tillage |

Minimum Tillage (using implements or not) |

Minimal soil disturbance to conserve moisture and structure. |

Maize yield higher in 89%.

Legume yield higher in 90%. |

16% adopted in Inhambane province.

7% adopted in Gaza province. |

[15,27,36,37,38,39] |

| Conventional Tillage |

Intensive soil plowing before planting. |

Soil degradation and SOC loss.

Lower yields for both maize and legumes.

Low drought resilience. |

75%-100% uses conventional tillage in southern Mozambique. |

Soil Cover (Crop Residue Retention/Mulching)

|

Cover Cropping/mulching |

Using plants or crop residues to protect and enrich the soil |

Maize grain yields by 24% to 59%.

Maintains permanent soil cover with ≥30% crop residues. |

60% adopted in southern Mozambique |

3.3.2. Crop Management

Table 6 presents the Crop management practices (intercropping and crop rotation) implemented in southern Mozambique. Evidence shows that maize–legume intercropping, involving crops such as cowpea, groundnuts, pigeon pea, and soybeans, is practiced by more than 60% of farmers in the region, with adoption rates ranging from 60% to 90% [

15,

17,

37,

38]. These figures were largely derived from household surveys and farmer interviews, confirming intercropping as a farmer-led adaptation strategy. This system consistently increases yields of both maize and legumes by over 30%, largely due to complementary resource use, improved nitrogen fixation, and enhanced soil cover [

30]. From an adaptation perspective, intercropping buffers farmers against drought by reducing risk of total crop failure, if one crop performs poorly under dry conditions, the companion legume often sustains household production and food supply [

40,

41]. In addition, survey-based evidence indicates that adopters of maize–legume systems reported significantly higher Food Consumption Scores (p < 0.05), reflecting both improved productivity and resilience to climatic shocks [

33,

41].

Crop rotation strategies, particularly alternating maize with legumes such as cowpea or groundnuts, are less widespread but still significant, with adoption levels between 40% and 74% among smallholder farmers in southern Mozambique [

30]. Data from surveys and focus group discussions confirm that rotation improves pest and disease control, restores soil fertility, and stabilizes yields over time [

41]. Trials in Mozambique and Zimbabwe further demonstrated yield increases of up to 38% for maize and cowpea rotations compared to monoculture systems (p < 0.1), highlighting their role in low-input environments [

42]. Importantly, crop rotation enhances adaptive capacity to drought by improving soil organic matter, which increases water-holding capacity and reduces vulnerability during prolonged dry spells [

43]. In Tanzania, maize–pigeon pea systems improved land use efficiency, with Land Equivalent Ratios (LER) consistently >1 [

43], confirming productivity gains similar to those seen in Mozambique.

Table 5.

Crop management (cereal and legume combinations).

Table 5.

Crop management (cereal and legume combinations).

| Category |

Type |

Description |

Impact/Result |

Adoption of smallholders’ farmers |

Citation |

Crop Management Cereal-legume combinations (e.g., maize with cowpea or peanut)

|

Maize-Legume Intercropping |

Growing maize with legumes in the same field for soil health. |

More than 60% of farmers practice intercropping between Maize and legume (Cowpea, Groundnuts, Pigeon Pea and Soybeans).

Increases yield both Maize and Legumes in more than 30%. |

60% to 90% adopt in southern Mozambique

|

[15,37,38,39] |

| Crop Rotation |

Alternating different crops in the same field each season to restore soil. |

Highest yield in both Maize and Cowpea is 38%.

Improve crop management practices (less pests, less diseases, etc). |

40% to 74% of adoption in southern Mozambique. |

3.3.3. Drought Tolerant Variety

Table 7 presents the drought tolerant variety implemented in southern Mozambique. Drought-tolerant varieties demonstrated yield increases of 26–46%, equivalent to 695–1,422 kg/ha of maize more than conventional varieties [

10,

13,

29]. Adoption rates range from 40% to 77% in southern Mozambique [

37,

39,

44,

45]. Though national survey data reported only 11% of households planting improved maize to cope with drought in 2011 [

46,

47]. In other hand, evidence from randomized controlled trials indicates that drought-tolerant maize offset nearly all yield losses during moderate mid-season droughts, while conventional varieties suffered declines of up to 15% [

48]. However, the protective effect was weaker under severe drought, where yields of improved varieties also fell significantly [

35]. Besides, drought-tolerant maize with intercropping systems enhances both yield stability and dietary diversity, particularly when legumes such as cowpea, pigeon pea, and lablab are used [

14,

49]. These findings confirm that while drought-tolerant maize is critical for stabilizing food production, its effectiveness is maximized within broader risk management and soil fertility strategies [

50]. Moreover, the findings indicate that drought-tolerant varieties exhibit greater effectiveness in mitigating drought impacts when cultivated in intercropping systems, as opposed to being grown as sole crops.

Table 6.

Drought tolerant variety.

Table 6.

Drought tolerant variety.

| Category |

Conservation practice |

Type |

Description |

Impact/Result |

Adoption of smallholders’ farmers |

Citation |

| Drought tolerant Variety |

Drought-Tolerant maize. |

Crop bred to survive with limited water. |

26–46% higher yields of maize (695–1422 kg/ha more). |

40% to 77% of adoption in southern Mozambique. |

[10,13,29,37,39,44,45] |

3.3.4. Traditional

Table 8 presents the traditional practices implemented in southern Mozambique. The table shows that traditional practices remain highly adopted among smallholder farmers in southern Mozambique, with adoption rates ranging between 75% and 100% [

13,

21,

44]. This widespread use reflects the continued reliance on Indigenous Knowledge (IK) as a central pillar of farming systems, particularly in contexts of recurrent droughts and climatic variability [

51]. In Gaza province, for example, farmers still attribute droughts to supernatural forces ( 51% to God and 12.5% to ancestors), shaping their reliance on ceremonies and prayers as first responses to climatic shocks [

44]. These beliefs directly influence the timing and order of adaptation strategies, with 63.5% of households prioritizing collective spiritual actions before individual agronomic measures [

13].

Practices such as rainmaking ceremonies (

Mbelelo), shifting planting months, and exchange systems like

Kurhimela and

Tsima illustrate how communities embed spiritual, social, and ecological knowledge into their agricultural calendars [

21]. Surveys and focus group discussions conducted in Chibuto and Guijá districts confirm that 31% of farmers still participate in traditional rain ceremonies, while 69% join collective church prayers as part of drought response strategies [

44]. Similar findings are reported in South Africa and Zimbabwe, where rituals such as

Mutoro and

Mbelelo serve both to ask for rain and to strengthen communal resilience [

51,

52].

Traditional knowledge also provides practical benefits beyond ceremonies. Rituals to chase away pests (

Pfupfanhe), indigenous food preservation systems, and the use of naturally resilient resources such as wood ash and creeper crops, contribute directly to improving maize and legume yields [

52]. Evidence from household surveys and FGDs in Gaza Province shows that farmers employ environmental indicators such as moon phases (92% of FGDs), cloud formations (88%), and wind direction (72%) to predict rainfall and adjust planting dates accordingly [

21]. These methods, though increasingly challenged by climate variability, remain the most accessible and trusted forecasting tools for rural households. Comparable strategies have been documented in Zambia and south Africa, where seed preservation, crop rotation, and indigenous pest management play key roles in sustaining production under drought [

53,

54].

Table 7.

Traditional practices or Indigenous Knowledge (IK).

Table 7.

Traditional practices or Indigenous Knowledge (IK).

| Conservation practice |

Type |

Description |

Impact/Result |

Adoption of smallholders’ farmers |

Citation |

| Traditional |

Traditional practices |

Indigenous methods passed down to manage farming naturally. Includes rainmaking rituals, pest-control rituals, burial ceremonies, shifting planting months, exchange systems (Khurimela, Tsima), and reliance on local natural resources. Also use of environmental indicators such as moon phases, cloud formations, and wind direction. |

31% of farmers in Chibuto & Guijá districts still join rainmaking rituals; 69% participate in collective drought prayers; 92% use moon phases, 88% cloud formations, and 72% wind direction (Gaza Province). These practices improve maize/legume yields and strengthen resilience. |

75% to 100% adopt in Southern Mozambique

|

[13,15,17,21,28,30,37,44,55,56] |

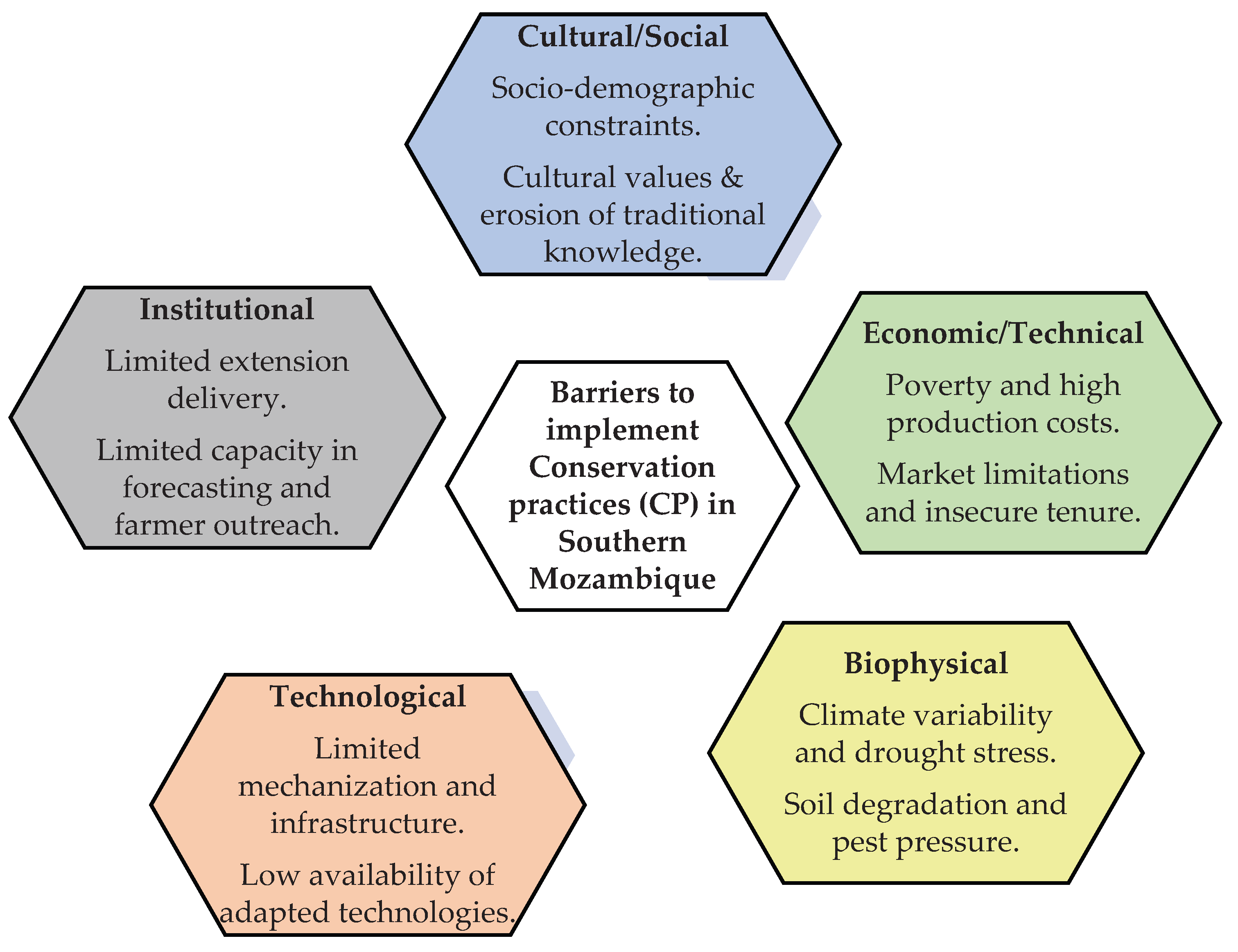

3.4. Barriers and Challenges to Implementation in Southern Mozambique

Although conservation practices show clear benefits in mitigating drought impacts, their adoption in southern Mozambique remains uneven. Multiple social/cultural, economic, institutional, technological and biophysical barriers continue to constrain wider implementation.

Figure 5 provides an overview of these barriers. The following sections explore each barrier category in detail.

3.4.1. Social/Cultural

Table 9 summarizes the socio-cultural barriers that influence the adoption of CSA and traditional practices in southern Mozambique. Adoption of CSA technologies in southern Mozambique is highly conditioned by gender and age. Male-headed households benefit from greater access to resources and extension services, while women face socio-cultural restrictions that limit their participation in training and decision-making [

44]. In Malawi and Zambia, similar trends were observed, with female-headed households more likely to abandon CSA due to financial constraints and lack of inputs, while widows frequently cited lack of access to information as a primary barrier [

57]. Age also plays a role, as older farmers in Mozambique tend to resist new practices, preferring familiar routines [

21]. These findings align with evidence from Bushbuckridge, South Africa, where regression models confirmed education as a significant positive predictor of CSA adoption (β = 1.554, p = 0.014), while larger household sizes had a strong negative effect (β = –1.307, p = 0.007) [

58].

Cultural norms and local perceptions add another layer of complexity. In Mozambique, cultural beliefs surrounding drought responses sometimes encourage maladaptive practices, such as rituals or communal ceremonies, which may reinforce social cohesion but fail to deliver long-term resilience [

13,

29,

56]. More broadly, CSA initiatives across Africa often struggle because they disregard farmers’ local knowledge [

59]. This mismatch between external interventions and community realities creates resistance, reducing adoption rates. The evidence thus suggests that CSA cannot be successfully scaled unless participatory approaches and context-specific designs are prioritized [

73]. Traditional and indigenous practices present both resilience strategies and barriers to CSA adoption. In southern Mozambique, farmers’ preference for landraces over improved varieties illustrates this dynamic, landraces are locally adapted and require fewer external inputs, but their use limits the uptake of new CSA technologies [

21].

Generational changes further weaken the continuity of indigenous knowledge systems. In southern Mozambique, the declining number of elders has eroded the transmission of weather-prediction skills, leaving younger generations with limited familiarity with these methods [

21]. This erosion coincides with the increasing dominance of modern meteorological forecasts, which often fail to integrate or validate traditional knowledge, leading to distrust and cultural disconnection [

59]. Moreover, spiritual beliefs that attribute climate events to supernatural forces reduce farmers’ perception of their adaptive capacity, discouraging investment in proactive adaptation strategies [

13]. These findings align with broader African evidence, where the neglect of local knowledge and cultural systems in CSA design is identified as a major obstacle to adoption [

59].

Table 8.

Social/cultural barriers.

Table 8.

Social/cultural barriers.

| Barrier Type |

Conservation Practice |

Barrier Detail |

Citation |

| Social/Cultural |

Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) practices

|

Gender

Male-headed households have a higher probability of adopting improved technologies due to their social and cultural position, and preferential access to information compared to female-headed households.

Age

Older farmers are less flexible to new ideas and have shorter planning horizons.

Others

Farming time experience, household size, and farmers' associations also influence adoption.

Cultural beliefs directly influence responses to drought, sometimes leading to practices that are not necessarily adaptive or effective in the long term.

Farmers' preference for the staple food crop maize, leading to mono-cropping practices.

Farmers preference for landraces over improved varieties due to local adaptation and low input requirements. |

[13,21,29,44,56]

|

| Traditional/Indigenous practices |

Reduced number of elders in the community is causing a decline of traditional practices.

Younger generations have reduced knowledge of traditional prediction methods compared to elders.

Lack of documentation of traditional practices.

Belief that supernatural forces control the weather reduce farmers' perception of their own adaptive capacity |

3.4.2. Institutional

Table 10 summarizes the institutional weaknesses that influence the adoption of CSA and traditional practices in southern Mozambique. The limited capacity of The Mozambican National Meteorological Institute (INAM) to monitor and disseminate climate information mirrors findings across Africa, where poor institutional frameworks and weak policy support reduce the reliability of climate services for agricultural planning [

29,

60]. Similarly, government responses that prioritize short-term relief rather than long-term adaptation reflect the institutional inefficiencies observed in South Africa, where fragmented support systems and reactive policy approaches hinder effective CSA implementation [

61]. These weaknesses are further reinforced by rigid bureaucratic systems that slow research and adaptation processes, consistent with broader reviews that identify weak institutional arrangements and incoherent policy frameworks as central barriers to CSA adoption [

31].

Another institutional constraint concerns the delivery of extension services. In Mozambique, logistical issues such as lack of transport and fuel, prevent extension officers from regularly reaching farmers, which reduces opportunities for knowledge transfer and follow-up [

13]. Comparable evidence from South Africa shows that while farmers acknowledge the usefulness of extension, the quality of climate-related advice remains poor, with fewer than 2% of smallholders receiving support annually between 2014 and 2017 [

61]. Moreover, lack of coordination among institutions and overlapping mandates generate confusion for farmers when accessing services, echoing findings from regional reviews that emphasize the absence of clear institutional frameworks and the need for integrated governance structures [

60]. These institutional deficiencies are not only technical but systemic, highlighting that CSA adoption depends on building coherent, well-coordinated, and adequately resourced institutional environments.

For traditional and indigenous practices, the table shows that institutional barriers arise mainly from limited scientific research and documentation. This gap prevents the incorporation of local knowledge into formal agricultural policies and advisory programs [

13]. Similar patterns are noted across Sub-Saharan Africa, where CSA interventions often neglect indigenous knowledge, assuming farmers are homogeneous and disregarding diverse cultural practices [

59,

62]. Such exclusion reduces the legitimacy of external interventions and widens the gap between formal institutions and community-based systems, weakening adoption rates and community ownership of adaptation measures.

The erosion of indigenous knowledge systems is also intensified by institutional neglect. Younger generations in Mozambique increasingly rely on modern meteorological services that rarely integrate traditional forecasting, which diminishes confidence in indigenous practices [

13]. Across Africa, this dynamic is reinforced by top-down CSA programs that fail to recognize local knowledge as co-equal with scientific expertise, creating resistance and limiting uptake [

59,

60]. Bridging this divide requires institutional reforms that integrate participatory approaches, systematically document indigenous practices, and embed them into extension and research frameworks. Such efforts would ensure that CSA and traditional strategies complement rather than compete, enhancing resilience at the community level.

Table 9.

Institutional barries.

Table 9.

Institutional barries.

| Barrier Type |

Conservation Practice |

Barrier Detail |

Citation |

| Institutional |

Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) practices

|

The Mozambican National Meteorological Institute (INAM) is limited in its capacity to adequately monitor, forecast, and communicate weather and climate data.

Government responses are often reactive, uncoordinated, and untimely, focusing on relief rather than long-term adaptation.

Bureaucratic management systems with rigid logical frameworks hinder evolutionary research processes.

Lack of visits by extension agents is farmers due to logistical issues (e.g., lack of fuel). |

[13,29,31] |

| Traditional/Indigenous practices |

Limited scientific studies on traditional/indigenous practices |

3.4.3. Economic

Table 11 summarizes the economic constraints that influence the adoption of CSA and traditional practices in southern Mozambique. High levels of poverty remain a critical limitation, as nearly 68.7% of the population lives on less than USD 1.90 per day, which reduces farmers’ capacity to invest in improved technologies [

13]. This situation mirrors findings across Africa, where limited access to credit and insurance is consistently identified as a major constraint to CSA adoption [

63]. In Mozambique, surveys show that 52% of farmers fail to adopt CSA practices due to financial capacity to make on-farm investments [

69]. These results align with evidence from South Africa, where access to credit significantly raises the likelihood of adoption, with one study reporting that a 1% increase in credit access can increase CSA uptake by 63% [

61].

The cost and availability of inputs and equipment also constitute major barriers. Farmers face high prices for seeding equipment such as jab planters [

56], while improved seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides remain scarce or unaffordable [

55]. Studies from across Sub-Saharan Africa confirm that the high cost and limited accessibility of inputs reduce resilience and increase vulnerability to climate shocks [

64]. Technical equipment such as irrigation kits, animal or tractor, powered implements, and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) for climate services also remain prohibitively expensive, limiting widespread use [

60]. These challenges are compounded by poor infrastructure and limited market access. In Mozambique, only 20% of roads are paved, constraining both input delivery and the marketing of surpluses [

69]. This is consistent with findings from South Africa, where poor infrastructure and fragmented value chains undermine the profitability of CSA interventions [

62].

In Mozambique, insecure land tenure exacerbates economic barrier, as farmers are unwilling to invest labor and resources into plots where ownership and use rights remain uncertain [

29]. This corresponds to regional evidence that ambiguous tenure discourages long-term investments in CSA, particularly soil fertility and agroforestry practices, which require extended time horizons to be profitable [

60]. In other hand, in Mozambique, the lack of crop residues to ensure soil cover further limit technical feasibility, constraining the practical implementation of CSA practices [

13].

Table 10.

Economic constraints.

Table 10.

Economic constraints.

| Barrier Type |

Conservation Practice |

Barrier Detail |

Citation |

| Economic |

Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) practices |

High levels of poverty (68.7% of the population live below USD 1.90 per day).

Limited Access to Agricultural Inputs (e.g., hybrid varieties, fertilizers, etc).

High prices of seeding equipment (e.g., jab planters).

Lack of markets for surpluses.

Insecure land tenure disincentivize long-term investments in soil quality.

Lack of adequate crop residues for soil cover limit CSA uptake. |

[13,29,55,56]

|

3.4.4. Technological Barriers

Table 12 summarizes the technological barriers that influence the adoption of CSA and traditional practices in southern Mozambique. Farmers without appropriate implements they cannot execute conservation operations such as minimum tillage, residue retention, and precision planting at the right time [

10,

45]. Regionally, similar patterns are reported across Sub-Saharan Africa, where the absence of CSA-specific equipment and thin input–machinery supply chains are repeatedly flagged as core technological bottlenecks that depress farm-level adoption [

74]. In other hand, communication barriers compound these issues, low-quality radio/TV/mobile signals and sparse electrification restrict access to seasonal forecasts, early warnings, and agronomic guidance, widening the technological divide between better-connected and remote households [

39,

45]. Taken together, the Mozambican findings align with regional evidence that technological barriers are less about farmer reluctance and more about missing or ill-adapted tools, weak power/connectivity, and limited research–extension bandwidth to localize technologies at scale [

15,

29].

Table 11.

Technological barriers.

Table 11.

Technological barriers.

| Barrier Type |

Conservation Practice |

Barrier Detail |

Citation |

| Technological |

Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) practices |

Lack of mechanization.

Lack of electricity.

Low quality radio, TV, and mobile signals are structural factors limiting access to these resources. |

[10,15,29,39,45] |

3.4.5. Biophysical Barriers

Table 13 summarizes the biophysical barriers that constrain the adoption of CSA and traditional practices in southern Mozambique. These include extreme droughts, high evapotranspiration surpassing rainfall, declining soil fertility, and pest outbreaks that undermine the effectiveness of drought-tolerant varieties, mulching, and other conservation practices [

39,

55,

56]. In addition, traditional forecasting systems based on local environmental indicators such as clouds, winds, or stars have lost reliability under increasing climatic variability, weakening farmers’ confidence in indigenous practices [

13]. Comparable, in Ethiopia and Kenya, rainfall variability and recurrent droughts are consistently cited as major drivers of low CSA adoption, while poor soil quality is linked to limited yield gains from conservation practices [

63]. A broader review confirms that farm size, distance to plots, access to water, and local topography are decisive biophysical constraints that condition adoption outcomes, as farmers closer to resources or markets are more likely to implement CSA successfully [

65,

66]. Moreover, agro-ecological diversity across the region complicates the universal application of CSA technologies, requiring site-specific interventions rather than one-size-fits-all approaches [

67].

These findings show that biophysical barriers act as transversal constraints, not only cutting across CSA and indigenous practices but also reinforcing economic, institutional, social, and technological barriers. As such, overcoming these barriers requires system-level responses that complement household-level strategies and strengthen the enabling environment for CSA adoption.

Table 12.

Biophysical barriers.

Table 12.

Biophysical barriers.

| Barrier Type |

Conservation Practice |

Barrier Detail |

Citation |

Biophysical

|

Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) practices |

Extreme droughts reduce the performance of drought-tolerant maize varieties

High evapotranspiration exceeding rainfall undermines soil moisture retention

Soil degradation and declining fertility limit effectiveness of conservation pactices

Pest and disease outbreaks aggravated by climatic stress discourage adoption |

[10,39,55,56] |

| Traditional/Indigenous practices |

Traditional rainfall prediction losing reliability due to increasing climate variability

Environmental indicators (clouds, wind, stars) no longer consistent predictors of rainfall |

[13]

|

4. Limitations of the Literature

Based on the systematic review of 23 studies, there is a degree of geographic imbalance, while Gaza province is well represented, Inhambane and Maputo provinces remain understudied. This limits external validity across heterogeneous agro-ecological zones. And on the other hand, most of the available evidence derives from short-term trials, which cannot capture a long-term system response, yield trajectories, or soil fertility dynamics under recurrent droughts.

5. Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions

Future research should move beyond short-term, single-site experiments and adopt multi-year, multi-site designs that capture temporal dynamics and heterogeneous agro-ecologies across southern Mozambique. Second, there is a need for mixed methods approaches that combine household surveys with controlled field trials, supported by longitudinal and panel data to assess adoption trajectories and yield stability over time. Third, the integration of indigenous and scientific knowledge should be operationalized through co-designed participatory trials and evaluation of complementarities (e.g., how local indicators can be linked with meteorological forecasts). Fourth, research should critically examine institutional and socio-cultural mechanisms, including gendered decision-making, land tenure security, and farmer-extension interactions, that mediate the adoption of conservation practices. Finally, future studies should explicitly evaluate policy and programmatic interventions, such as input subsidies, credit schemes, and extension models, to assess not only technical performance but also pathways for scaling adoption across diverse smallholder systems.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights that smallholder farmers in southern Mozambique rely on a diverse set of conservation practices, encompassing both Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) techniques and Indigenous Knowledge (IK), to adapt to climate change- and variability-induced droughts. These practices, such as minimum tillage, mulching, intercropping, crop diversification, drought-tolerant varieties, and traditional forecasting methods, contribute to improved soil and water management, enhanced yields, and strengthen resilience in rainfed farming systems. However, adoption remains uneven across provinces and practices. While some approaches, particularly those rooted in indigenous traditions, demonstrate relatively high uptake, many CSA techniques face low adoption due to persistent barriers. Socio-economic constraints (limited access to credit, inputs, and markets), institutional weaknesses (insufficient extension services and policy support), cultural dynamics (gender roles, decision-making), technological and biophysical gaps, collectively limit the broader scaling of these practices. The review also reveals significant knowledge gaps. Empirical evidence on the long-term effectiveness of conservation practices remains scarce, with most studies being short-term and spatially concentrated. Integration of CSA and IK, though widely advocated, has rarely been systematically documented or evaluated. In conclusion, building climate-resilient smallholder farming systems in southern Mozambique requires more than the promotion of individual practices. It calls for: (i) integrated strategies that combine CSA techniques with indigenous knowledge; (ii) policy interventions that strengthen extension services, credit access, and institutional coordination; and (iii) targeted research that uses longitudinal, participatory, and comparative approaches to assess practice effectiveness and farmer adoption dynamics. Addressing these gaps will not only enhance the adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers but also contribute to sustainable livelihoods and food security under a changing climate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Aires Adriano Mavulula and Tesfay Araya; methodology, Aires Adriano Mavulula and Tesfay Araya; validation, Tesfay Araya, Luis Artur and Jone Medja Ussalu; formal analysis, Aires Adriano Mavulula; investigation, Aires Adriano Mavulula; data curation, Aires Adriano Mavulula; writing—original draft preparation, Aires Adriano Mavulula; writing—review and editing, Tesfay Araya, Luis Artur and Jone Medja Ussalu; visualization, Aires Adriano Mavulula; supervision, Luis Artur and Jone Medja Ussalu; project administration, Aires Adriano Mavulula; funding acquisition, Aires Adriano Mavulula. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the Climate Research and Education to Advance Green Development in Africa (CREATE–Green Africa) program, funded by the European Union and hosted at the University of the Free State, South Africa, and by the Centre of Excellence in Food Security and Nutrition Systems (CE-AFSN) hosted at Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique, through the ACE II – Additional Funds project. The APC was funded by the CREATE–Green Africa program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study were derived from the published literature included in the systematic review. The full list of references analyzed is provided in the manuscript, and data extraction tables are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Climate Research and Education to Advance Green Development in Africa (CREATE–GreenAfrica) program, funded by the European Union and hosted at the University of the Free State, South Africa, and from the Centre of Excellence in Food Security and Nutrition Systems (CE-AFSN) hosted at Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique through the ACE II – Additional Funds project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Disclaimer: The terms indigenous, traditional, and local are used interchangeably throughout this article to describe practices embedded in local knowledge systems and transmitted across generations.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| CP |

Conservation practices |

| CSA |

Climate-Smart Agriculture |

| SLF |

Livelihoods Framework |

| MT |

Minimum Tillage |

| CT |

Conventional Tillage |

| IK |

Indigenous Knowledge |

| FGD |

Focus groups discussion |

References

- Myers, S.S.; Smith, M.R.; Guth, S.; Golden, C.D.; Vaitla, B.; Mueller, N.D.; Dangour, A.D.; Huybers, P. Climate Change and Global Food Systems: Potential Impacts on Food Security and Undernutrition. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnell, N.W.; Lowe, J.A.; Challinor, A.J.; Osborn, T.J. Global and Regional Impacts of Climate Change at Different Levels of Global Temperature Increase. Climatic Change 2019, 155, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.C.; Carvalho, D.; Rocha, A. Temperature and Precipitation Extremes over the Iberian Peninsula under Climate Change Scenarios: A Review. Climate 2021, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Work-ing Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Mas-son-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emediegwu, L.E.; Wossink, A.; Hall, A. The Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Spatial Panel Data Approach. World Development 2022, 158, 105967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleia, R.; Maúre, G.; José, A.; Maholela, P.; Adjei, I.A.; Karim, Md.R.; Trigo, S.; Kutane, W.; Inlamea, O.; Kazembe, L.N.; et al. Assessing the Vulnerability and Adaptation Needs of Mozambique’s Health Sector to Climate: A Comprehensive Study. IJERPH 2024, 21, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, A. Natural Hazards and Climate Change Impacts on Food Security and Rural–Urban Livelihoods in Mozambique—A Bibliometric Analysis and Framework. Earth 2024, 5, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinto, N. Tropical Cyclone Freddy Exposes Major Health Risks in the Hardest-Hit Southern African Countries: Lessons for Climate Change Adaptation. International Journal of Surgery: Global Health 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, S.A.; Jalata, D.D.; Onyeaka, H. Building Resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Food Systems: Diversification, Traceability, Capacity Building and Technology for Overcoming Challenges. Food and Energy Security 2024, 13, e563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.I.; Naico, A.; Ricardo, J.; Eyzaguirre, R.; Makunde, G.S.; Ortiz, R.; Grüneberg, W.J. Genotype × Environment Interaction and Selection for Drought Adaptation in Sweetpotato (Ipomoea Batatas [L.] Lam.) in Mozambique. Euphytica 2016, 209, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, J.; Bilotto, F.; Mbui, D.; Omondi, P.; Harrison, M.T.; Crane, T.A.; Sircely, J. Exploring Smallholder Farm Resilience to Climate Change: Intended and Actual Adaptation. Pastor. res. policy pract. 2024, 14, 13424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthelo, D.; Owusu-Sekyere, E.; Ogundeji, A.A. Smallholder Farmers’ Adaptation to Drought: Identifying Effective Adaptive Strategies and Measures. Water 2019, 11, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salite, D. Traditional Prediction of Drought under Weather and Climate Uncertainty: Analyzing the Challenges and Opportunities for Small-Scale Farmers in Gaza Province, Southern Region of Mozambique. Nat Hazards 2019, 96, 1289–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondlhane, C.; Munjonji, L.; Victorino, Í.; Huenchuleo, C.; Pimentel, P.; Cornejo, P. Sustainable Agricultural Alternatives to Cope with Drought Effects in Semi-Arid Areas of Southern Mozambique: Review and Strategies Proposal. World 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichongue, O.; Pelser, A.; Tol, J.V.; Du Preez, C.; Ceronio, G. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Conservation Agriculture Practices among Smallholder Farmers in Mozambique. Int. J. Agr. Ext. 2020, 7, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichongue, O.; Pelser, A.; Tol, J.V.; Du Preez, C.; Ceronio, G. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Conservation Agriculture Practices among Smallholder Farmers in Mozambique. Int. J. Agr. Ext. 2020, 7, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhantumbo, N.; Chaminuka, P.; Henriques, A.C.; Palma, J.; Mp, A. Identifying Scalable Sustainable Intensification Pathways for the Rainfed N-Deprived Maize-Legume Cropping Systems of Eastern and Southern Africa – The Cases of Mozambique and Tanzania.

- Khainga, D.N.; Marenya, P.P.; Da Luz Quinhentos, M. How Much Is Enough? How Multi-Season Exposure to Demonstrations Affects the Use of Conservation Farming Practices in Mozambique. Environ Dev Sustain 2021, 23, 11067–11089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuchete, L.; Hove, A.; Nezomba, H.; Rurinda, J.; Mbanyele, V.; Mlambo, S.; Nyakudya, E.; Mtambanengwe, F.; Mapfumo, P. Productivity of Sorghum and Millets under Different In-Field Rainwater Management Options on Soils of Varying Fertility Status in Zimbabwe. Front. Agron. 2024, 6, 1378339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masinde, M. An Effective Drought Early Warning System for Sub-Saharan Africa: Integrating Modern and Indigenous Approaches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Southern African Institute for Computer Scientist and Information Technologists Annual Conference 2014 on SAICSIT 2014 Empowered by Technology; ACM: Centurion South Africa, September 29, 2014; pp. 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Salite, D. Explaining the Uncertainty: Understanding Small-Scale Farmers’ Cultural Beliefs and Reasoning of Drought Causes in Gaza Province, Southern Mozambique. Agric Hum Values 2019, 36, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthelo, D.; Owusu-Sekyere, E.; Ogundeji, A.A. Smallholder Farmers’ Adaptation to Drought: Identifying Effective Adaptive Strategies and Measures. Water 2019, 11, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvobgo, L.; Odoulami, R.C.; Johnston, P.; Simpson, N.P.; Trisos, C.H. 1 Indigenous and Local Knowledge in the Vulnerability of Smallholder Farmers to 2 Climate Variability and Change in Chiredzi, Zimbabwe.

- Deppisch, S.; Hasibovic, S. Social-Ecological Resilience Thinking as a Bridging Concept in Transdisciplinary Research on Climate-Change Adaptation. Nat Hazards 2013, 67, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, N.L.; De Bremond, A.; Malone, E.L.; Moss, R.H. Towards a Resilience Indicator Framework for Making Climate-Change Adaptation Decisions. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 2014, 19, 1295–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majale, M. Towards Pro-Poor Regulatory Guidelines for Urban Upgrading: A Review of Papers. Presented at the International Workshop on Regulatory Guidelines for Urban Upgrading, Bourton-On-Dunsmore, May 17–18, 2001; Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG): Rugby, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, P.; Walker, F.; Haggblade, S.; Maria, R.; Eash, N. Conservation Agriculture in Mozambique - Literature Review and Research Gaps.

- Osbahr, H.; Twyman, C.; Neil Adger, W.; Thomas, D.S.G. Effective Livelihood Adaptation to Climate Change Disturbance: Scale Dimensions of Practice in Mozambique. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla-Miras, P.; Lisboa, S.N.; López-Gunn, E.; Giordano, R. Farmers’ Information Sharing for Climate Change Adaptation in Mozambique. Information Development 2024, 02666669241227910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichongue, O.; Van Tol, J.; Ceronio, G.; Du Preez, C. Effects of Tillage Systems and Cropping Patterns on Soil Physical Properties in Mozambique. Agriculture 2020, 10, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, P.P.; Kerr, J.M.; Donovan, C. ; Bordalo Mouzinho A Prospective Analysis of Participatory Research on Conservation Agriculture in Mozambique 2015.

- Mango, N.; Siziba, S.; Makate, C. The Impact of Adoption of Conservation Agriculture on Smallholder Farmers’ Food Security in Semi-Arid Zones of Southern Africa. Agric & Food Secur 2017, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamayevu, D.; Nyagumbo, I.; Chipindu, L.; Li, R.; Liang, W. Crop Diversification and Reduced Tillage for Improved Grain and Nutritional Yields in Rain-Fed Maize-Based Cropping Systems of Semi-Arid Malawi. Ex. Agric. 2025, 61, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwira, A.; Johnsen, F.H.; Aune, J.B.; Mekuria, M.; Thierfelder, C. Adoption and Extent of Conservation Agriculture Practices among Smallholder Farmers in Malawi. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2014, 69, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierfelder, C.; Rusinamhodzi, L.; Setimela, P.; Walker, F.; Eash, N.S. Conservation Agriculture and Drought-Tolerant Germplasm: Reaping the Benefits of Climate-Smart Agriculture Technologies in Central Mozambique. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2016, 31, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichongue, Ó.; Van Tol, J.J.; Ceronio, G.M.; Du Preez, C.C.; Kotzé, E. Short-Term Effects of Tillage Systems, Fertilization, and Cropping Patterns on Soil Chemical Properties and Maize Yields in a Loamy Sand Soil in Southern Mozambique. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyagumbo, I.; Mkuhlani, S.; Pisa, C.; Kamalongo, D.; Dias, D.; Mekuria, M. Maize Yield Effects of Conservation Agriculture Based Maize–Legume Cropping Systems in Contrasting Agro-Ecologies of Malawi and Mozambique. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 2016, 105, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Encarnação Tomo, M.; Zwane, E. Assessment of Factors Influencing the Adoption of Improved Crop Management Practices (ICMP) by Smallholder Farmers in the Boane District, Mozambique. S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhantumbo, A.; Famba, S.; Fandika, I.; Cambule, A.; Phiri, E. Yield Assessment of Maize Varieties under Varied Water Application in Semi-Arid Conditions of Southern Mozambique. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnukwa, M.L.; Mdoda, L.; Mudhara, M. Frontiers | Assessing the Adoption and Impact of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices on Smallholder Maize Farmers’ Livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. [CrossRef]

- Phiri, A.; Njira, K.; Dixon, A. Comparative Effects of Legume-based Intercropping Systems Involving Pigeon Pea and Cowpea under Deep-bed and Conventional Tillage Systems in Malawi. Agrosystems Geosci & Env 2024, 7, e20503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinamhodzi, L.; Corbeels, M.; Nyamangara, J.; Giller, K.E. Maize–Grain Legume Intercropping Is an Attractive Option for Ecological Intensification That Reduces Climatic Risk for Smallholder Farmers in Central Mozambique. Field Crops Research 2012, 136, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, L.L.R.; Kimaro, A.A.; Hafner, J.M.; Rosenstock, T.S.; Gaudin, A.C.M. Maize-Pigeonpea Intercropping Outperforms Monocultures Under Drought. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 562663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salite, D.; Poskitt, S. Managing the Impacts of Drought: The Role of Cultural Beliefs in Small-Scale Farmers’ Responses to Drought in Gaza Province, Southern Mozambique. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 41, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, L.; Chiziane, O.; Mandhlate, G.; Hartley, F.; Tostão, E. Impact of Climate Change on the Agriculture Sector and Household Welfare in Mozambique: An Analysis Based on a Dynamic Computable General Equilibrium Model. Climatic Change 2021, 167, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavane, E.; Donovan, C. Determinants of Adoption of Improved Maize Varieties and Chemical Fertilizers in Mozambique. JIAEE 2011, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Abate, T.; Lunduka, R.W.; Asnake, W.; Alemayehu, Y.; Madulu, R.B. Drought Tolerant Maize for Farmer Adaptation to Drought in Sub-Saharan Africa: Determinants of Adoption in Eastern and Southern Africa. Climatic Change 2015, 133, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, J.E.; Hellin, J.; Sonder, K.; Araus, J.L.; MacRobert, J.F.; Thierfelder, C.; Prasanna, B.M. Adapting Maize Production to Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Sec. 2013, 5, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; Corbeels, M.; Nyamangara, J.; Triomphe, B.; Affholder, F.; Scopel, E.; Tittonell, P. A Research Agenda to Explore the Role of Conservation Agriculture in African Smallholder Farming Systems. Field Crops Research 2011, 124, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupangwa, W.; Thierfelder, C.; Cheesman, S.; Nyagumbo, I.; Muoni, T.; Mhlanga, B.; Mwila, M.; Sida, T.S.; Ngwira, A. Effects of Maize Residue and Mineral Nitrogen Applications on Maize Yield in Conservation-Agriculture-Based Cropping Systems of Southern Africa. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, M.S.; Masunungure, C.; Manyani, A. Integrating Local Indigenous Knowledge to Enhance Risk Reduction and Adaptation Strategies to Drought and Climate Variability: The Plight of Smallholder Farmers in Chirumhanzu District, Zimbabwe. Jàmbá Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyambo, F.; Bahta, Y.T.; Jordaan, A.J. The Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Drought Risk Reduction: A Case of Communal Farmers in South Africa. Jamba 2017, 9, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanza, J.B.; Nsenduluka, E.; Shumba, O. Indigenous Knowledge Use and Its Constraints in Drought Resilience Building: A Case of Rural Gwembe-Zambia. JSS 2024, 12, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, T.A.; Chakale, M.V.; Asong, J.A.; Aremu, A.O.; Amoo, S.O. Indigenous Farming Methods and Crop Management Practices Used by Local Farmers in Madibeng Local Municipality, South Africa. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 8918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.; Silva, J.A. The Vulnerability Context of a Savanna Area in Mozambique: Household Drought Coping Strategies and Responses to Economic Change. Environmental Science & Policy 2009, 12, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalane, O.I.; Silva, E.V.D.; Sopchaki, C.H. AGRICULTURA DE SUBSISTÊNCIA E MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS: CASOS DOS DISTRITOS DE MAGUDE E MOAMBA (SUL DE MOÇAMBIQUE). RGNE 2021, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoza, S.; Van Niekerk, D.; Nemakonde, L. Gendered Vulnerability and Inequality: Understanding Drivers of Climate-Smart Agriculture Dis- and Nonadoption among Smallholder Farmers in Malawi and Zambia. E&S 2022, 27, art19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane, V.N.; Agholor, I.A.; Sithole, M.Z.; Morepje, M.T.; Msweli, N.S.; Mgwenya, L.I. Socio-Demographic Determinants of Climate-Smart Agriculture Adoption Among Smallholder Crop Producers in Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga Province of South Africa. Climate 2024, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyiola, A.; Gardezi, M.; Vij, S. Smallholder Farmers’ Engagement with Climate Smart Agriculture in Africa: Role of Local Knowledge and Upscaling. Climate Policy 2022, 22, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totin, E.; Segnon, A.C.; Schut, M.; Affognon, H.; Zougmoré, R.B.; Rosenstock, T.; Thornton, P.K. Institutional Perspectives of Climate-Smart Agriculture: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzielwana, R.A. Climate-Smart Food Systems: Integrating Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture in South Africa.

- Olabanji, M.F.; Chitakira, M. The Adoption and Scaling of Climate-Smart Agriculture Innovation by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa: A Review of Institutional Mechanisms, Policy Frameworks and Market Dynamics. World 2025, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finizola E Silva, M.; Van Schoubroeck, S.; Cools, J.; Van Passel, S. A Systematic Review Identifying the Drivers and Barriers to the Adoption of Climate-Smart Agriculture by Smallholder Farmers in Africa. Front. Environ. Econ. 2024, 3, 1356335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutengwa, C.S.; Mnkeni, P.; Kondwakwenda, A. Climate-Smart Agriculture and Food Security in Southern Africa: A Review of the Vulnerability of Smallholder Agriculture and Food Security to Climate Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O.; Khan, S.; Kithaka, K.M. A Review of the Socio-Economic, Institutional, and Biophysical Factors Influencing Smallholder Farmers’ Adoption of Climate Smart Agricultural Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa. Earth 2025, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogisi, O.D.; Begho, T. Adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Progress, Barriers, Gender Differences and Recommendations. Farming System 2023, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakweya, R.B. Challenges and Prospects of Adopting Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices and Technologies: Implications for Food Security. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2023, 14, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020.

- CIAT;World Bank. Climate-Smart Agriculture in Mozambique; CSA Country Profiles for Africa Series; International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT): Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–25, Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/83338. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, R. , & Julaia, C. (2007). Drought characterization at Limpopo Basin Mozambique. Department of Rural Engineering, Faculty of Agronomy and Forestry Engineering, University Eduardo Mondlane.

- Recha, J. W. , Chiulele, R.M. (2017). Mozambique climate smart agriculture guideline. Vuna Guideline. Pretoria: Vuna. Online: http://vuna-africa.com.

- Araneda-Cabrera, R.J.; Bermudez, M.; Puertas, J. Revealing the spatio-temporal characteristics of drought in Mozambique and their relationship with large-scale climate variability. , 38, Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2021, 38, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, J.; Manyire, H.; Tambi, E. ; Bangali, S (2015). Barriers to scaling up/out climate smart agriculture and strategies to enhance adoption in Africa. Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa: Accra, Ghana.

- Dimande, P.; Arrobas, M.; Rodrigues, M.Â. Intercropped Maize and Cowpea Increased the Land Equivalent Ratio and Enhanced Crop Access to More Nitrogen and Phosphorus Compared to Cultivation as Sole Crops. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Food Consumption Score (FCS): +5.486 — Households that adopted CA with mulching experienced, on average, an increase of 5.486 points in their Food Consumption Score compared to non-adopters. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).