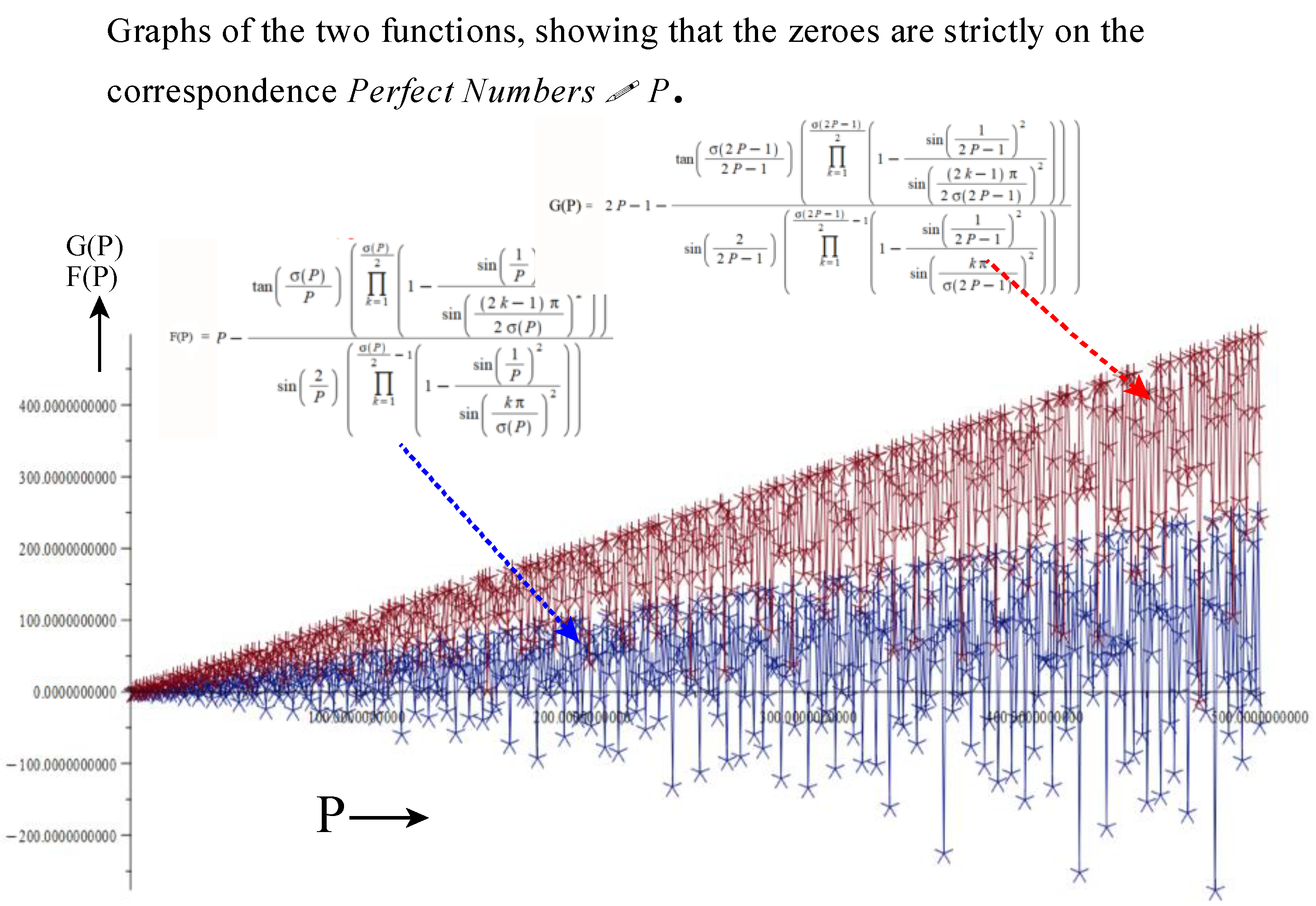

5. The General Relation That Captures the Behavior of Abondant Numbers, Perfect Numbers and Deficient Numbers

Definition 1: An Abundant number is a positive integer for which the sum of its proper divisors excluding itself is greater than the number itself.

Definition 2: A Perfect number is a number for which the sums of all divisors is equal to twice the number.

Definition 3: A Deficient number is a number for which the sums of all divisors is less than twice the number.

LEMMA: If

is a Perfect number, then,

Proof: for a Perfect number,

Hence,

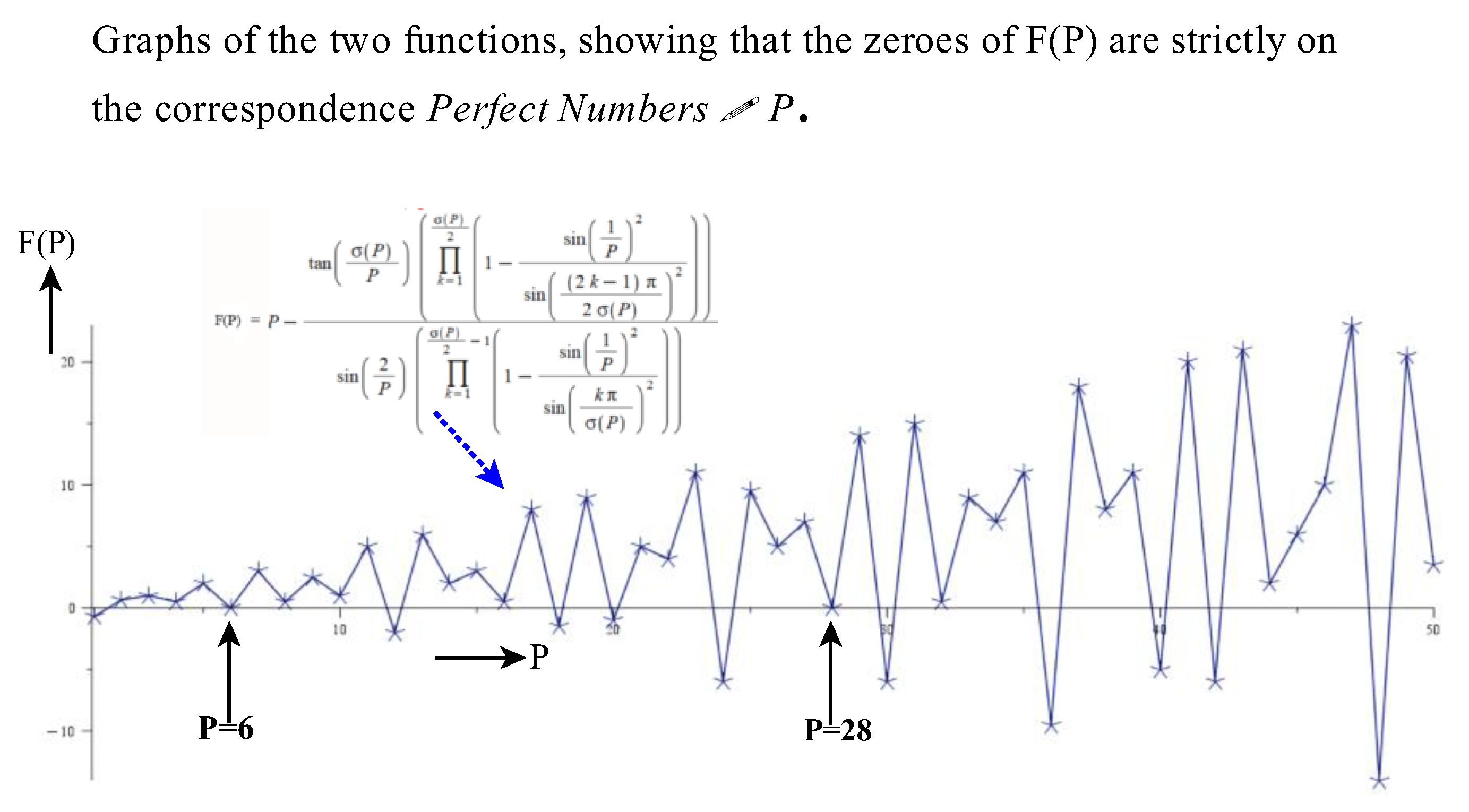

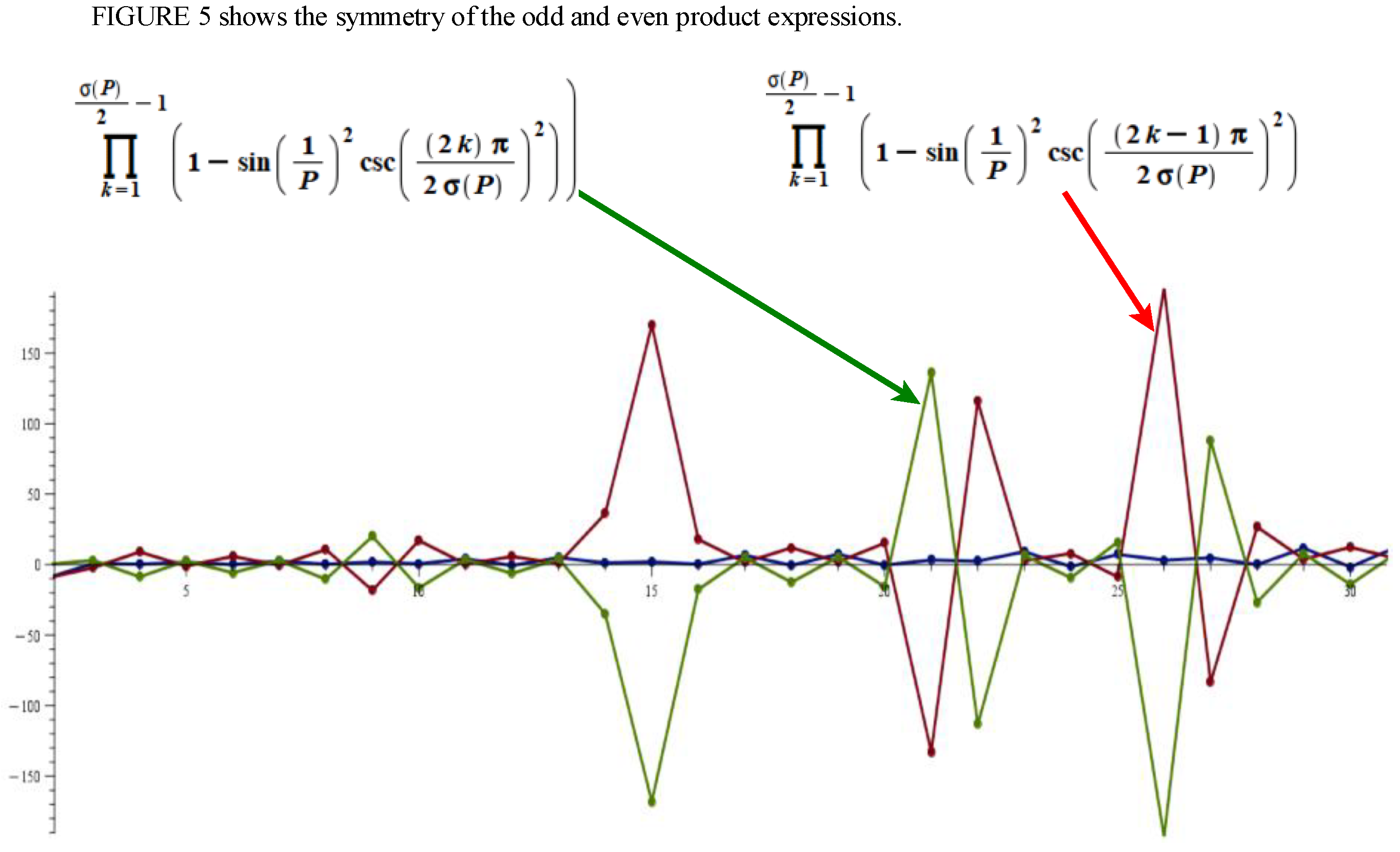

The distribution of

perfect numbers, abondant numbers and

deficient numbers is captured by the general relation:

a. For perfect numbers,

and the relation (33) vanishes.

b. For

abondant numbers,

and the relation does not vanish but generates negetaive imaginary values for

c. For

deficient numbers,

and the relation does not vanish but generates positive imaginary values for

To see this, put the relation (33) in the form:

Obviously, the zeros of the function (34) occur at the Perfect numbers. However, for clarity we convert this relation to the exponential form:

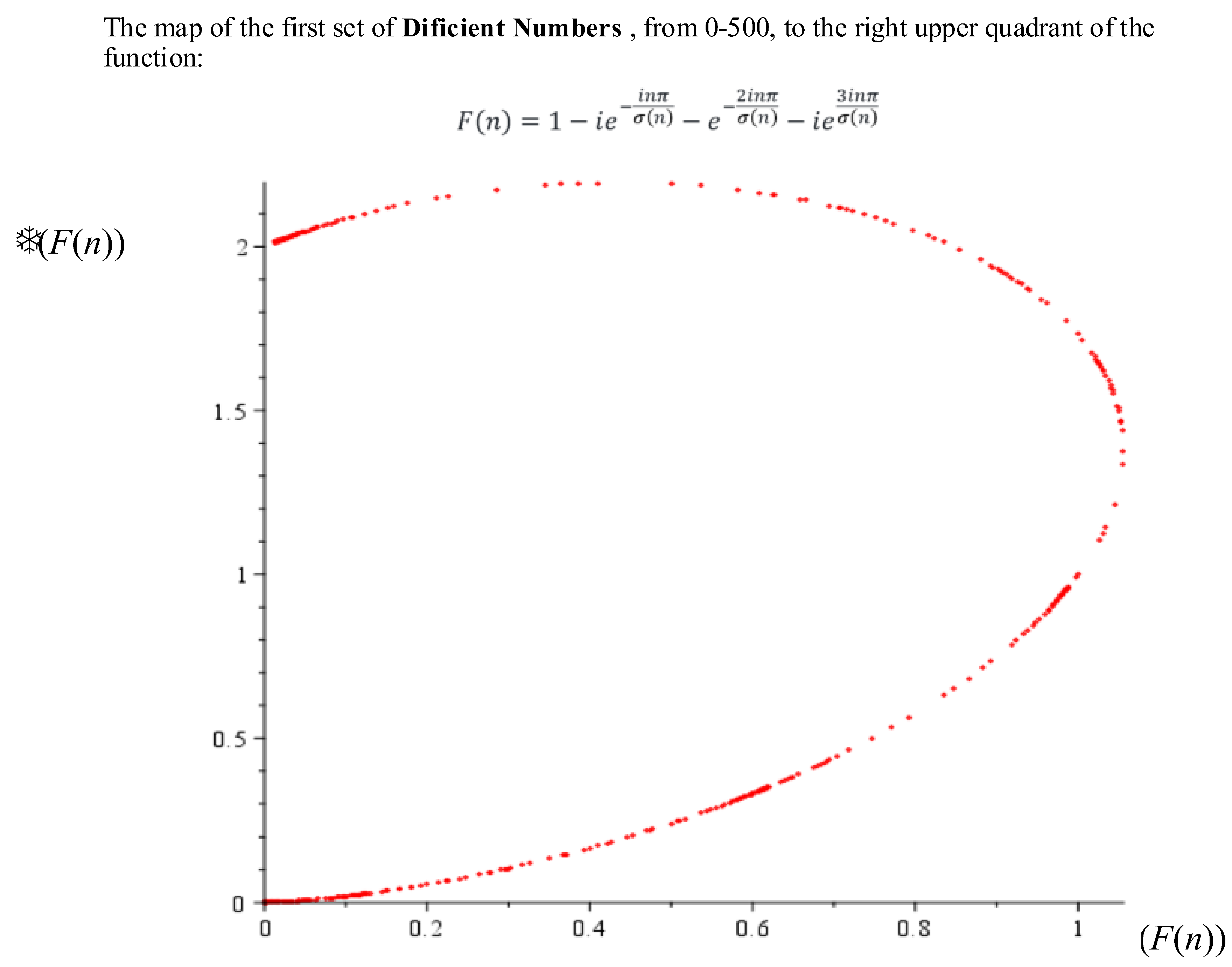

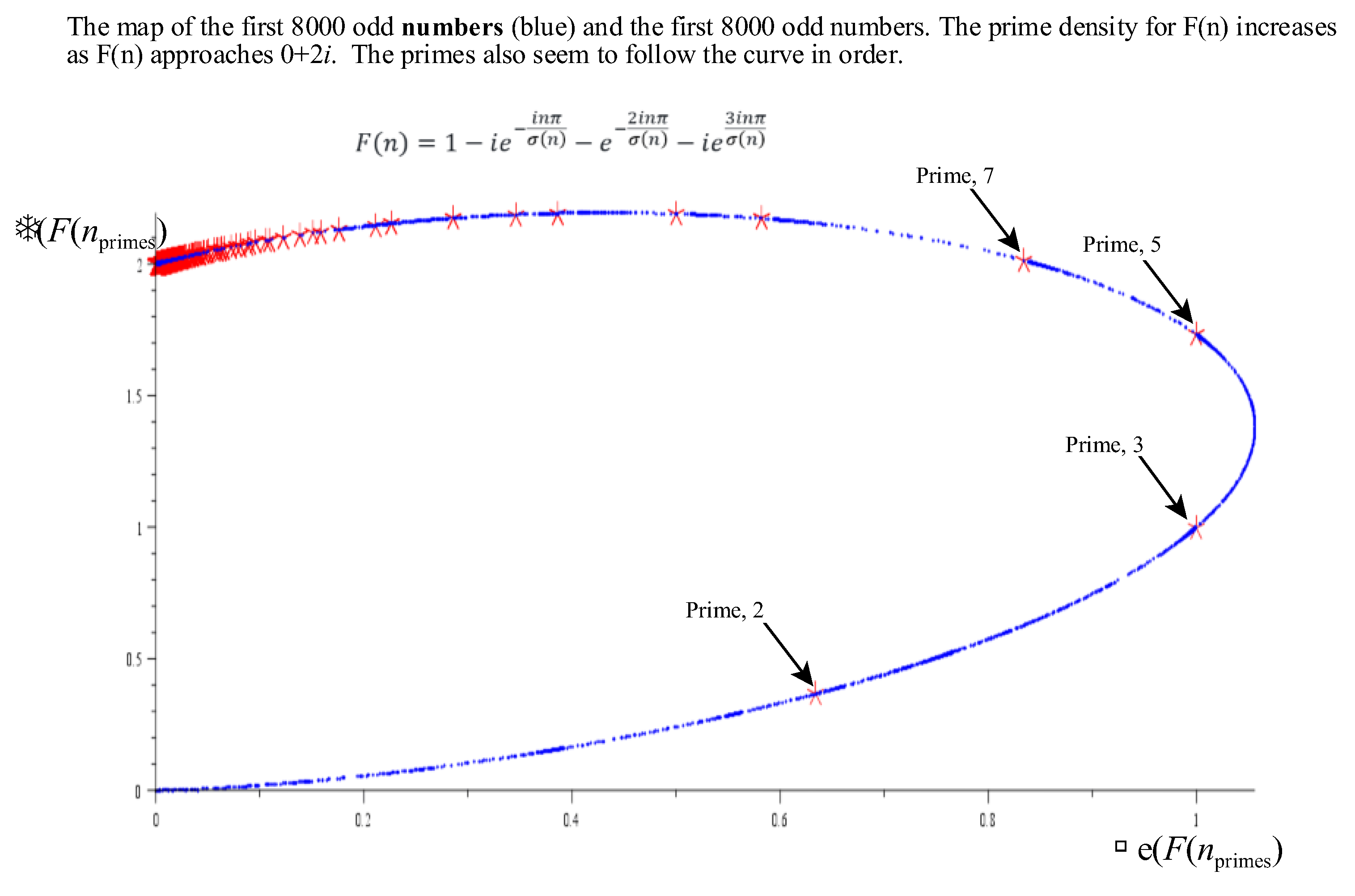

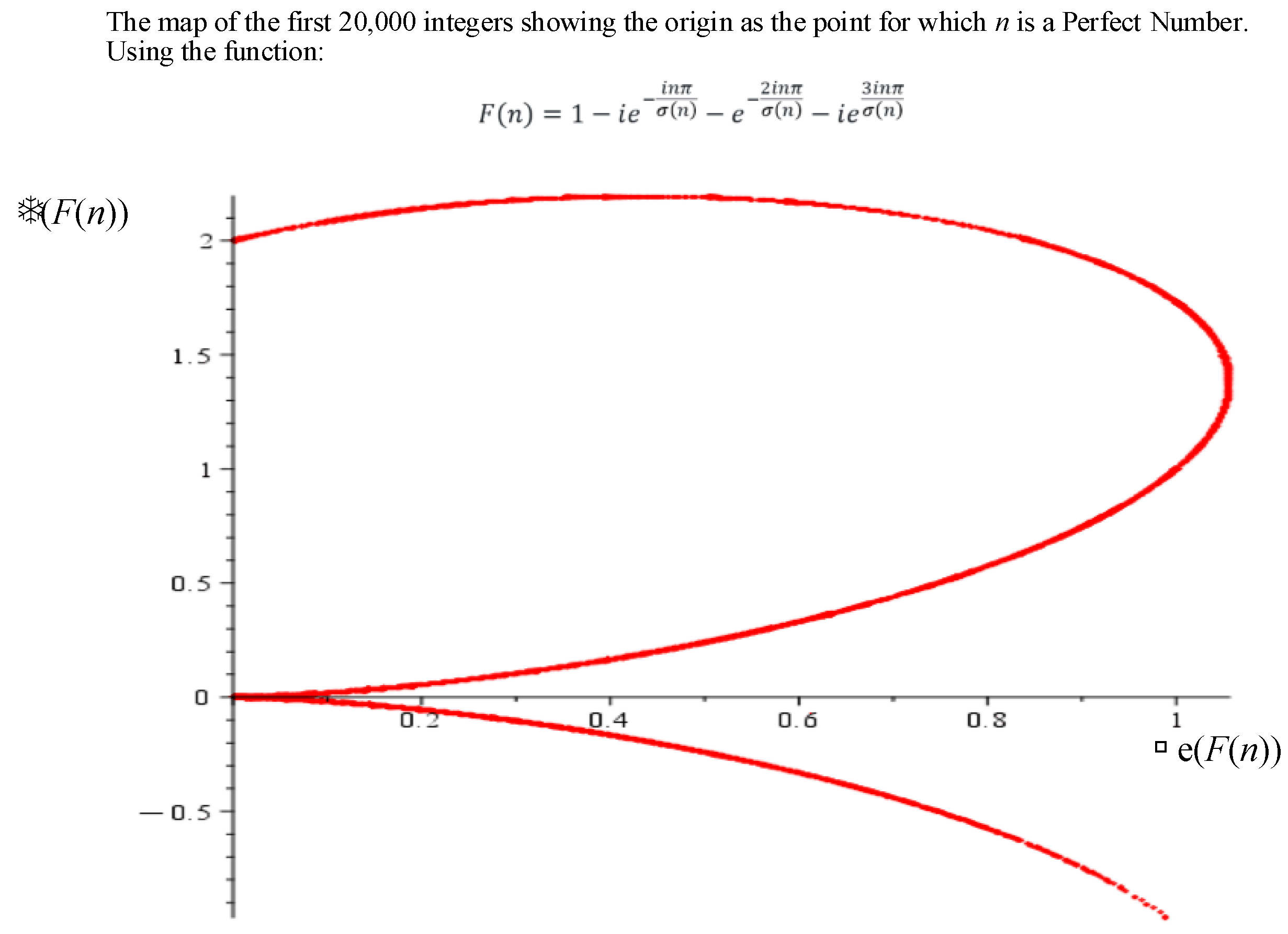

Figure 6 shows the complex map of the function

over the range

.

The zeros of the function occur at the values 6, 28, 496, 8124….

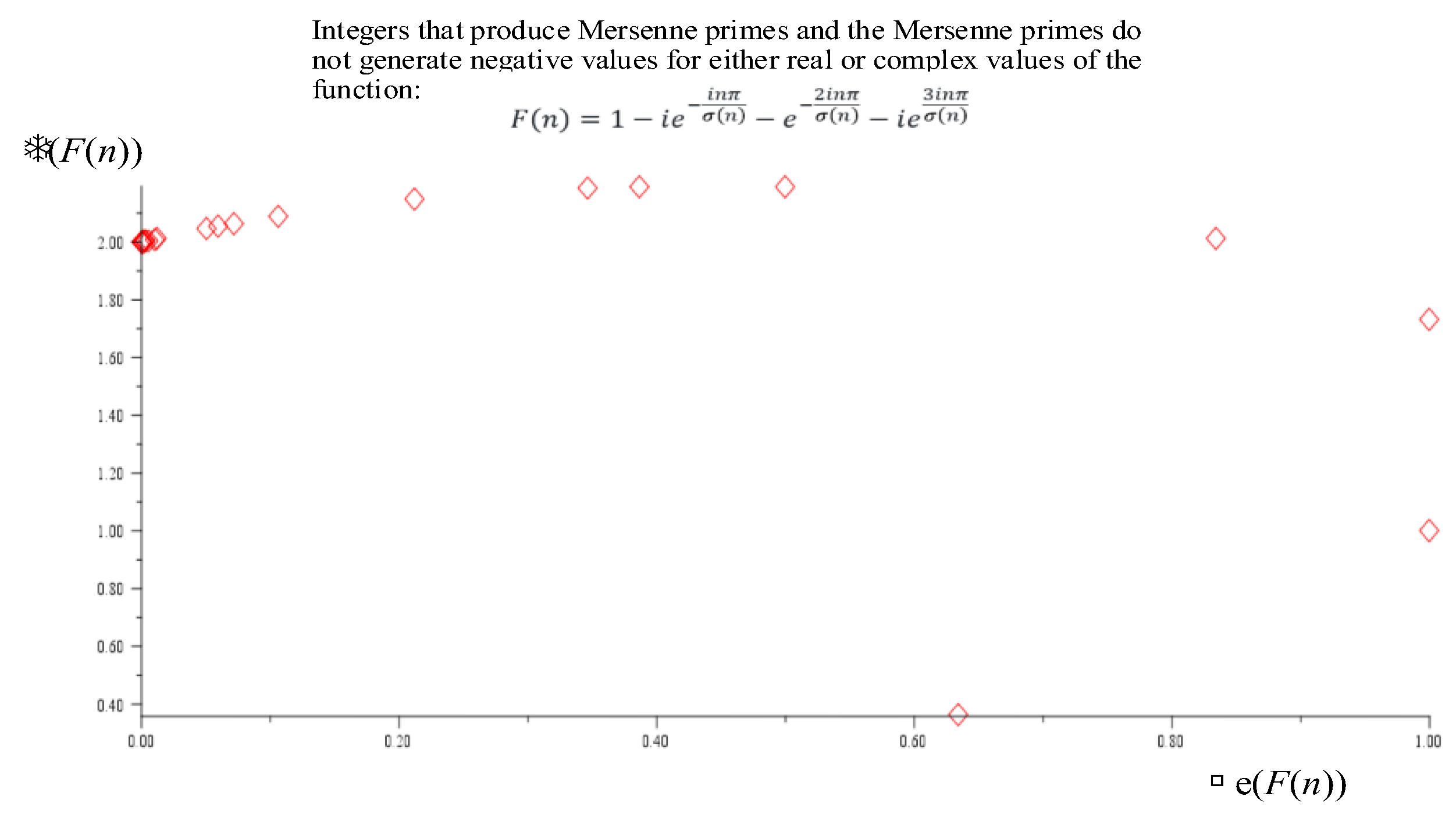

NOTE*: The Mersenne primes and the perfect numbers can only exist on the upper right quadrant corrsponding to deficient numbers. Perfect numbers are the zeros of the function .

The general locations of primes and Mersenne primes are shown in

Figure 7. As can be seen, the oprimes do not generate negative imaginary values, and are located on the top-right quadrant of the complex plane.

Hence, It is clear that the sequence of abundant numbers,

[12, 18, 20, 24, 30, 36, 40, 42, 48, 54, 56, 60, 66, 70, 72, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 96, 100, 102, 104, 108, 112, 114, 120, 126, 132, 138, 140, 144, 150, 156, 160, 162, 168, 174, 176, 180, 186, 192, 196, 198, 200, 204, 208, 210, 216, 220, 222, 224, 228, 234, 240, 246, 252, 258, 260, 264, 270, 272, 276, 280, 282, 288, 294, 300, 304, 306, 308, 312, 318, 320, 324, 330, 336, 340, 342, 348, 350, 352, 354, 360, 364, 366, 368, 372, 378, 380, 384, 390, 392, 396, 400, 402, 408, 414, 416, 420, 426, 432, 438, 440, 444, 448, 450, 456, 460, 462, 464, 468, 474, 476, 480, 486, 490, 492, 498, 500],

produce values of in (35) that lie on the lower right quadrant of the complex plane. This distinct observation for the first 500, abondant numbers provides a clue as to their distribution.

It is clear the first numbers between 0 and 500 that generate a sequence of deficient numbers:

[2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 55, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 67, 68, 69, 71, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 79, 81, 82, 83, 85, 86, 87, 89, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 97, 98, 99, 101, 103, 105, 106, 107, 109, 110, 111, 113, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 139, 141, 142, 143, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 157, 158, 159, 161, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 175, 177, 178, 179, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 193, 194, 195, 197, 199, 201, 202, 203, 205, 206, 207, 209, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 217, 218, 219, 221, 223, 225, 226, 227, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239, 241, 242, 243, 244, 245, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 259, 261, 262, 263, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269, 271, 273, 274, 275, 277, 278, 279, 281, 283, 284, 285, 286, 287, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293, 295, 296, 297, 298, 299, 301, 302, 303, 305, 307, 309, 310, 311, 313, 314, 315, 316, 317, 319, 321, 322, 323, 325, 326, 327, 328, 329, 331, 332, 333, 334, 335, 337, 338, 339, 341, 343, 344, 345, 346, 347, 349, 351, 353, 355, 356, 357, 358, 359, 361, 362, 363, 365, 367, 369, 370, 371, 373, 374, 375, 376, 377, 379, 381, 382, 383, 385, 386, 387, 388, 389, 391, 393, 394, 395, 397, 398, 399, 401, 403, 404, 405, 406, 407, 409, 410, 411, 412, 413, 415, 417, 418, 419, 421, 422, 423, 424, 425, 427, 428, 429, 430, 431, 433, 434, 435, 436, 437, 439, 441, 442, 443, 445, 446, 447, 449, 451, 452, 453, 454, 455, 457, 458, 459, 461, 463, 465, 466, 467, 469, 470, 471, 472, 473, 475, 477, 478, 479, 481, 482, 483, 484, 485, 487, 488, 489, 491, 493, 494, 495, 497, 499 ],

produce values of that lie on the upper right quadrant of the complex plane. This distinct observation for the first 500, defficient numbers and abondant numbers provides a clue as to their distributions.

Between the

abondant numbers and the deficient numbers, are the P

erfect Numbers, [6, 7, 28, 496, 8128, 33550336,….], that generate the zeros of the function:

Hence, the imaginary part of the function

determines if a number is an

abondant number, a

perfect number or a

deficient number.

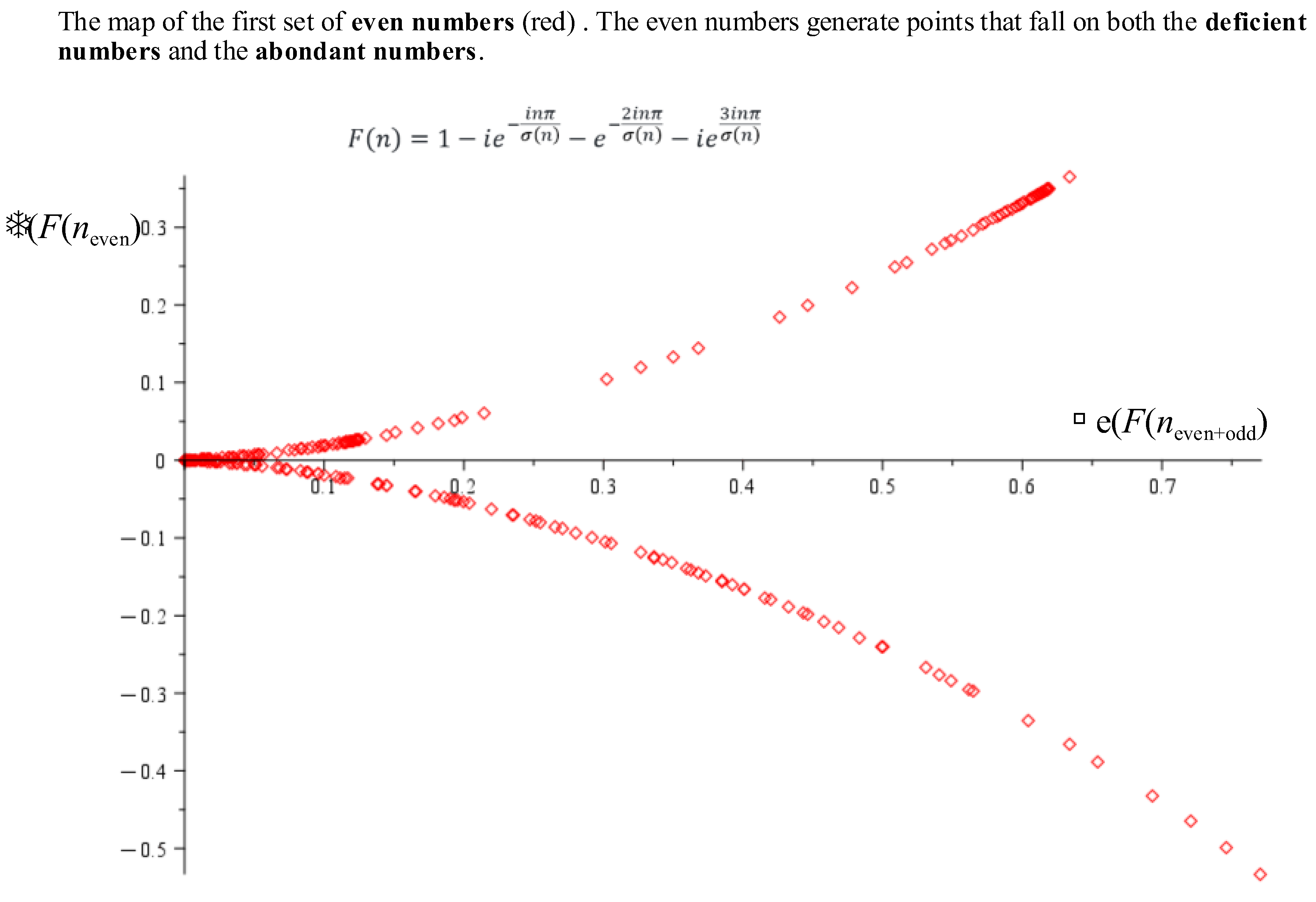

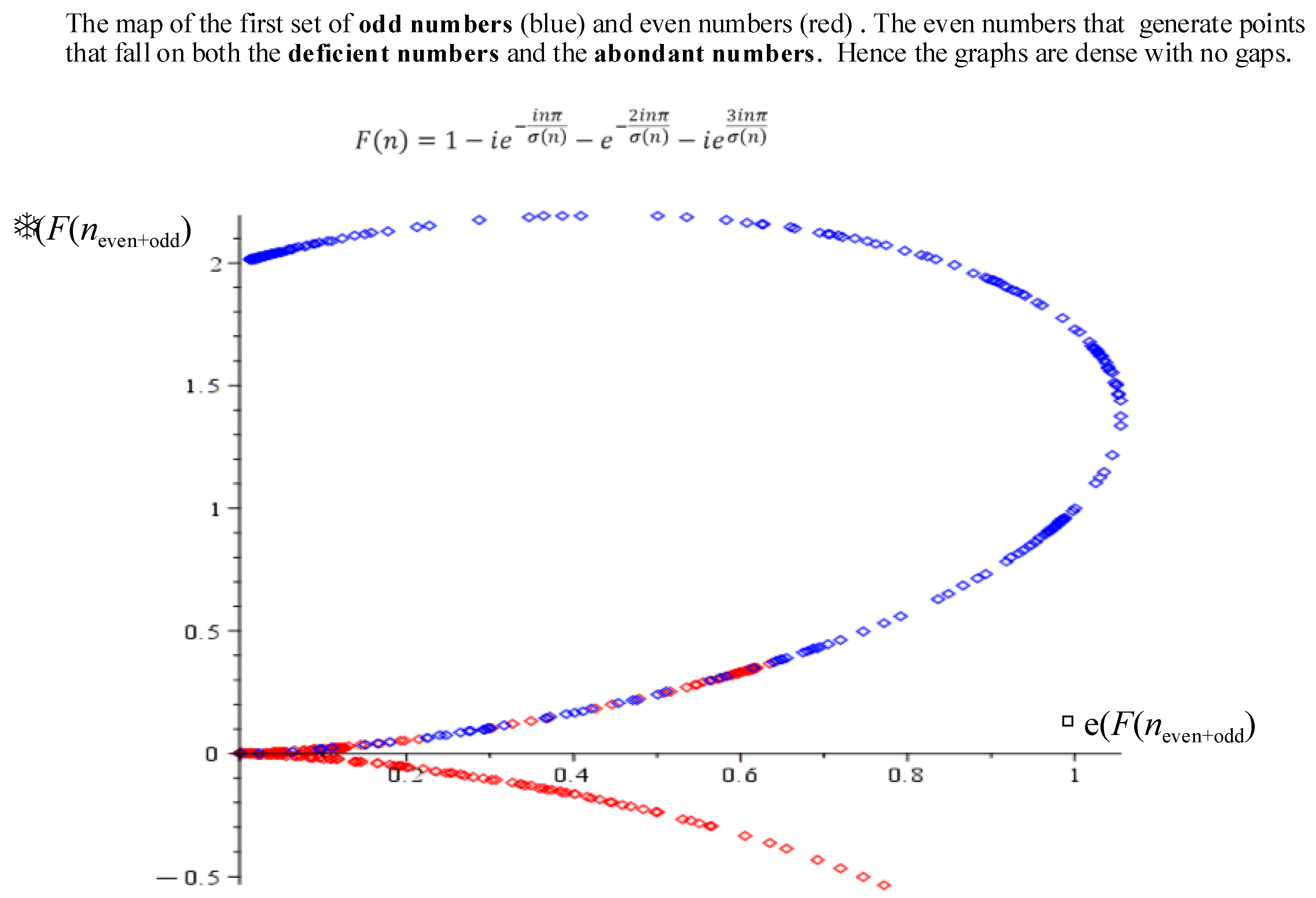

The first set of even numbers from 0..500 that lie on the defient number curve but are not abondant numbers are:

[2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, 16, 22, 26, 28, 32, 34, 38, 44, 46, 50, 52, 58, 62, 64, 68, 72, 74, 76, 82, 86, 92, 94, 98, 106, 110, 116, 118, 122, 124, 128, 130, 134, 136, 142, 146, 148, 152, 154, 158, 164, 166, 170, 172, 178, 182, 184, 188, 190, 194, 202, 206, 212, 214, 218, 226, 230, 232, 236, 238, 242, 244, 248, 250, 254, 256, 262, 266, 268, 274, 278, 284, 286, 290, 292, 296, 298, 302, 304, 310, 314, 316, 322, 326, 328, 332, 334, 338, 344, 346, 356, 358, 362, 370, 374, 376, 382, 386, 388, 394, 398, 404, 406, 410, 412, 418, 422, 424, 428, 430, 434, 436, 442, 446, 452, 454, 458, 466, 470, 472, 478, 482, 484, 488, 494, 496].

These numbers are clearly defined by (37).

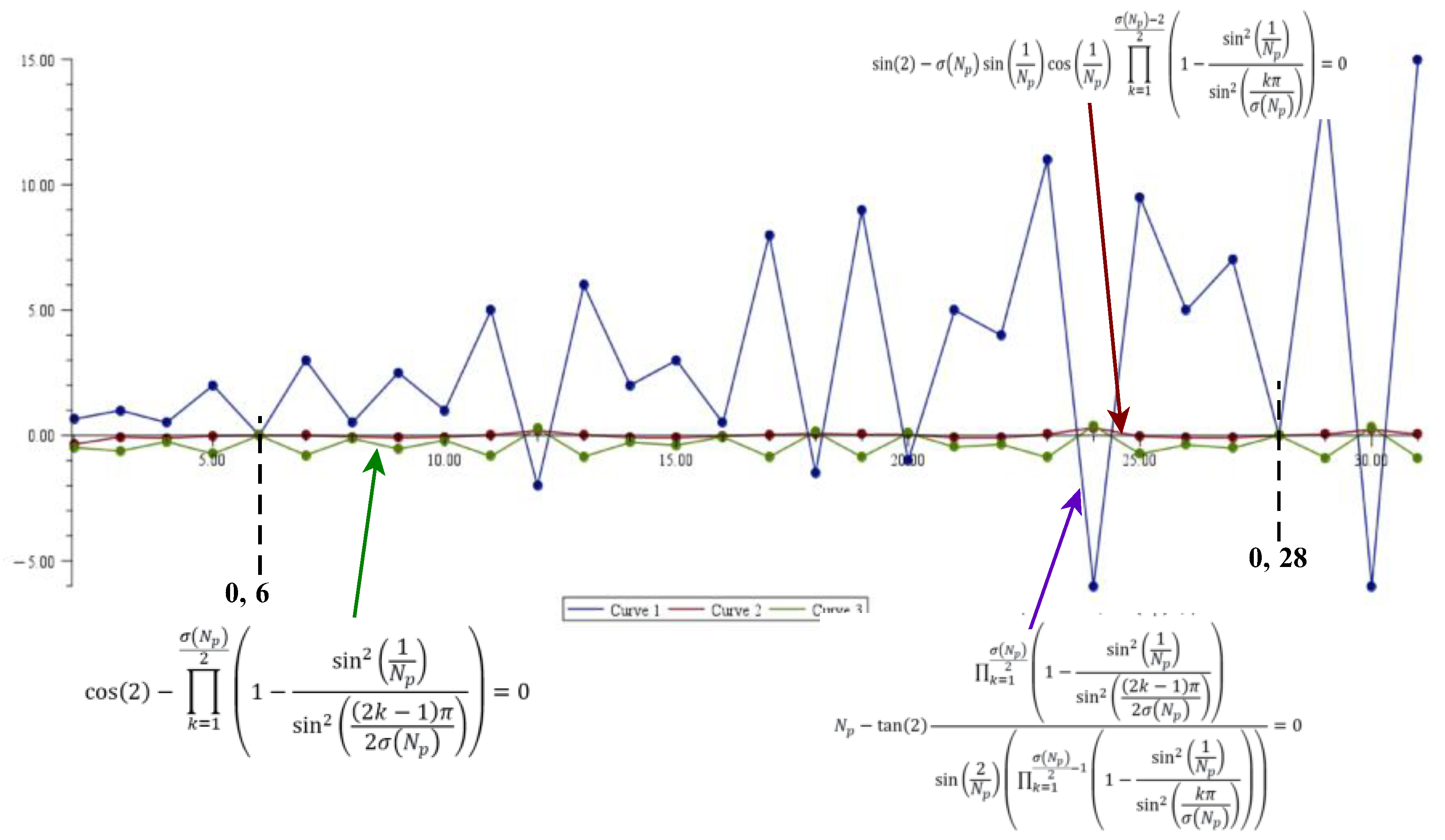

Figure 10 shows the 2D plot of the function covering both odd and even numbers in the range

0.

It is clear that the even numbers (red points) can fall on both the deficient number curve and the abondant number curve. The deficient numbers seem to be bounded by the line and a maximum imaginary value of .

Definition 4: An Deficient disturbing number , (DDN), is a deficient number which:

These are the red points on

Figure 10 that intermingle with the blue odd number points.

[2,4,8,10,14,16,22,26,32,34,38,44,46,50,52,58,62,64,68,74,76,82,86,92,94,98,106,110,116,118,122,124,128,130,134,136,142,146,148,152,154,158,164,166,170,172,178,182,184,188,190,194,202,206,212,214,218,226,230,232,236,238,242,244,248,250,254,256,262,266,268,274,278,284,286,290,292,296,298,302,310,314,316,322,326,328,332,334,338,344,346,356,358,362,370,374,376,382,386,388,394,398,404,406,410,412,418,422,424,428,430,434,436,442,446,452,454,458,466,470,472,478,482,484,488,494…..].

The extent to which the even numbers infiltrate the deficient number space for up to

seems to be confined to the approximate range,

The extent to which the even numbers penetrate the abondant number space is unknown. However it is known that there exists in infinite number of abundant numbers. It has been shown that every multiple is either an abondant number, or taking more multiples of 6 of such numbers leads to an bondant number. Since there is an infinite number of multiples of 6, then there are an infinite number of abondant numbers. Erdos &Graham, 1980, [], showed that even numbers greater than 46 are either abundant numbers or the sum of two abondant numbers.

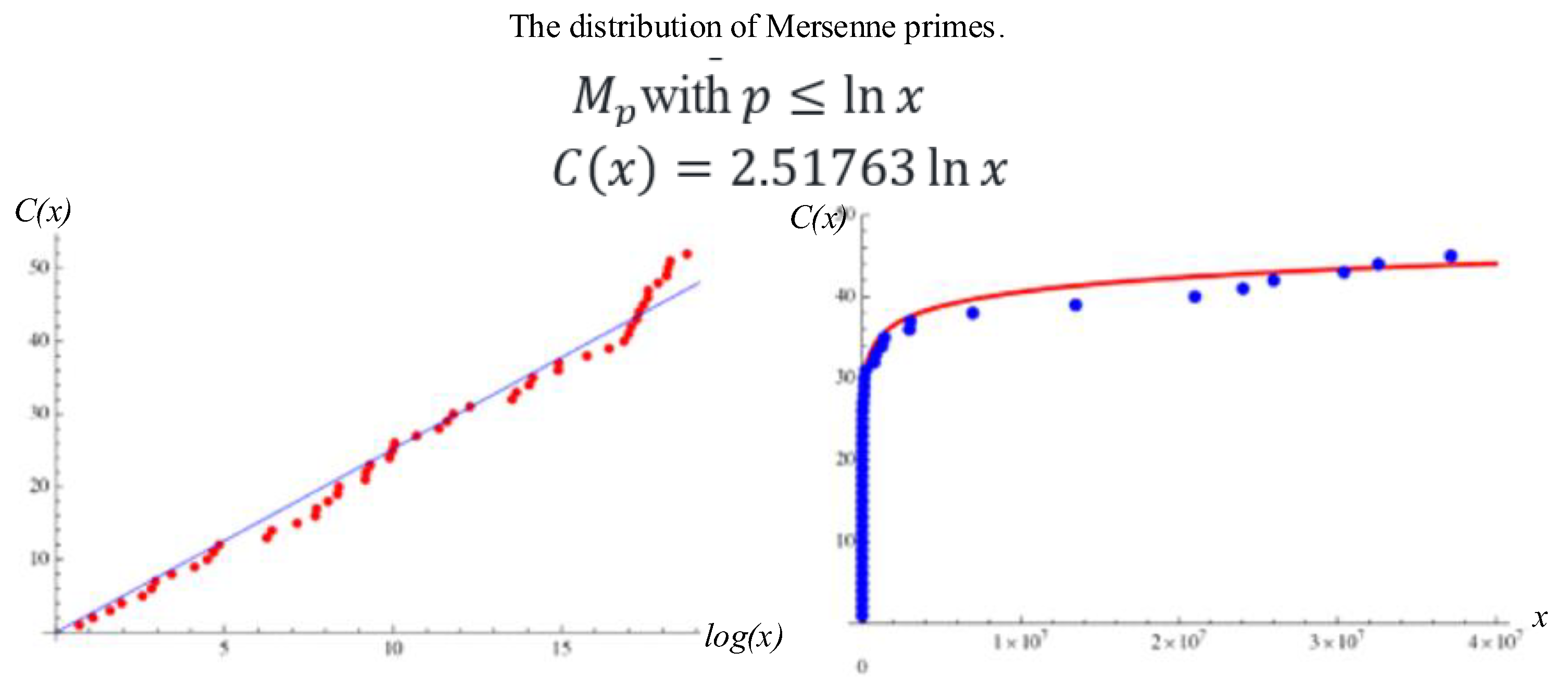

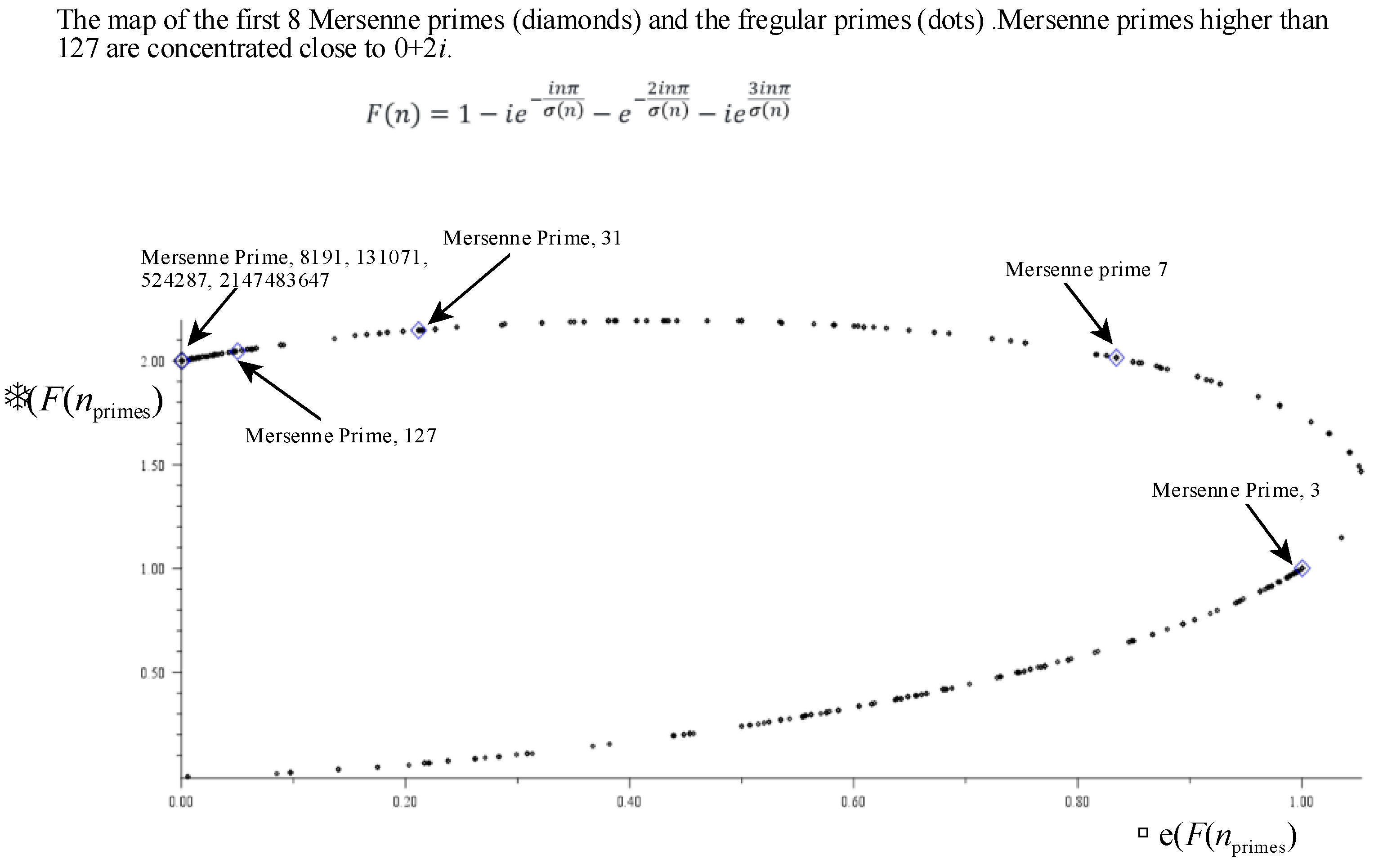

Figure 13 shows the distribution of the Mersenne primes with the regular primes.

6. The Extension of TH Function F(n) to A General Series Form

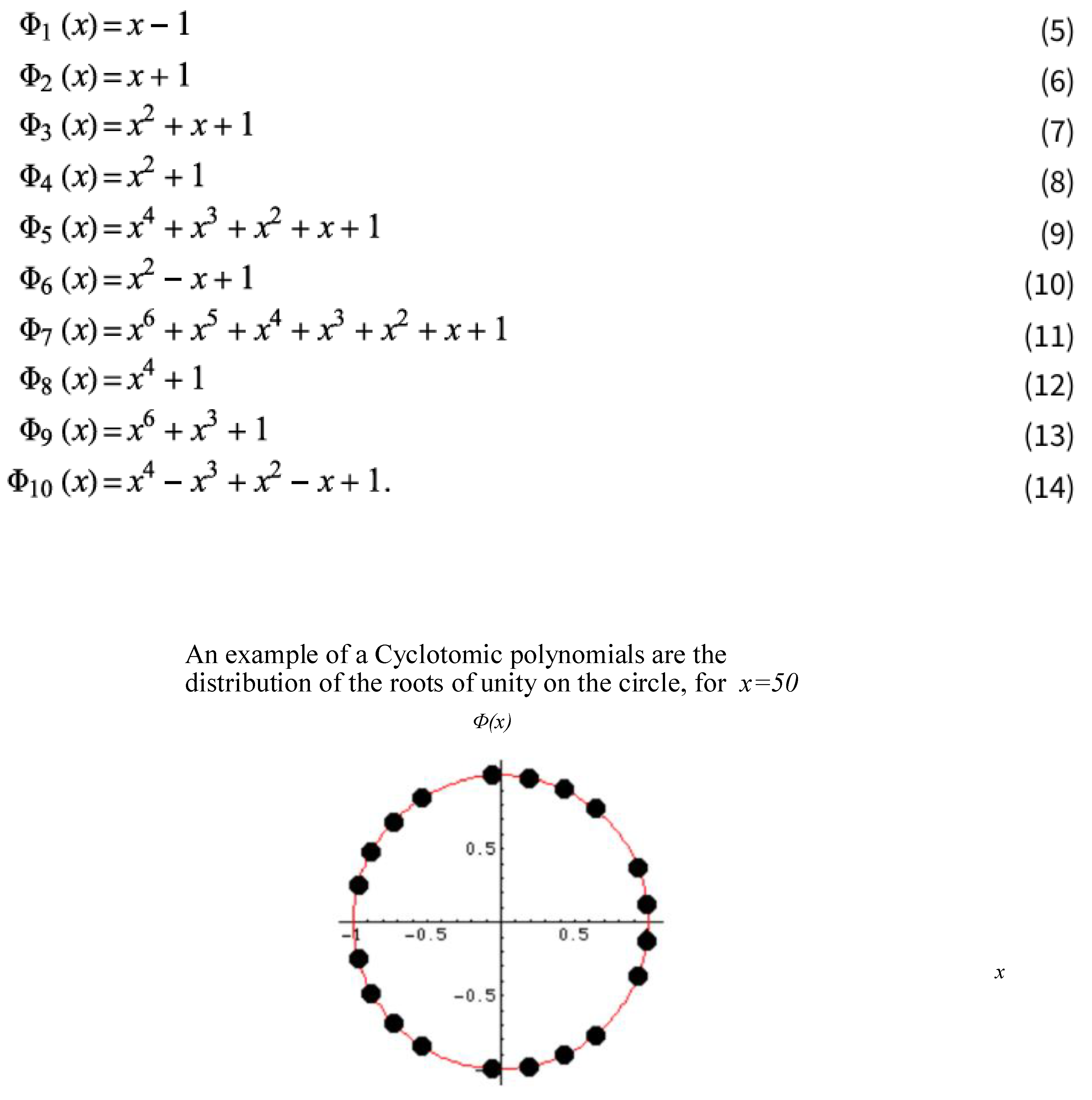

The function

behaves like a CyclotomicPolynomial. CyclotomicPolynomialare the minimal polynomials of primitive roots of unity with rational coefficients. The first few CyclotomicPolynomial are shown below:

A cyclotomic polynomial is of the product form:

where,

, are the roots of unity in the complex plane,

. In general, the circle,

and

is taken over integers relative prime to

It is clear that the function

is composed of functions of cyclotomic polynomials for the the special case of an expansion of some function over the function

Looking at exponential terms with the sequence,

we determine the first difference in the powers to be

The second difference gives,

The second difference points to the function

following a sequence of powers that is purely linear, but quadratic or alternating in some manner. We assume a quadratic relation, of the form,

However, the second differences are not the same constants, and so a recurrence relation of the form,

must be used to expand

as a series of higher powers for

recurrenses. The sequence of powers in

follows the recurrence, with initial conditions,

The characteristic equation for the recurrence then yeilds,

This yields, the two solutions,

Since the recurrence (46) follows a second order linear form, the general solution of the recurrence is

Solcing for

and

we get:

Hence we have the general form for

terms:

This sum produces the first four terms giving the same function:

The function,

will only have coefficients that are

1, or

, for the first 4 terms,

. The remaining terms

have large coefficients that blow up quickly. For example for m=7,

In general, for Perfect numbers,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

A 3-d plot of the function, shows that the function is the axis of an infinite cylinder ,where the rest of the terms lie.

Figure 15 shows the cylinderical form with the axis approaching a line when the cylinder radius approaches infinity. The axis of the cylinder becomes the solutions for Perfect numbers,

Now, from (18), for some integer ,

Hence for a Perfect number

, (57) gives:

Theorem 1: There are an infinite number of Mersenne Primes.

Analytic Mersenne Density and Infinitude.

Setup:

Fix Partition, into disjoint classes , and where is the set of Mersenne exponents with a prime.

Note

and

for

Definition (analytic Mersenne density).

With the set up above, at a fixed supposew the following holds true:

(H1) (Regularity/positivity of coefficients).

Each summand is positive and satisfies the classical Bernoulli-Zeta representation:

Hence, (H2): (Analytic density at ). The decomposition of ields a normalized quadratic identity in the as shown in LEMMA 2, only if LEMMA1 holds.

(H2): (Single valuedness/discriminat collapse). Since is single valued, the discriminat of the quadratic in LEMMA 2 vanishes.

Proof Sketch:

Absolute positivity and conditional subtraction.

By (H1), , and . The analytic value may be negative (e.g. ), which arises from subtracting the strictly positive from .

Quadratic normalization.

(H2) encodes the partition into a quadratic in

:

Since and , we have and finite and nonzero.

Discriminant collapse and consistency.

By (H3), . Solve for : the two roots coincide, so the quadratic exactly reproduces .

Contradiction from finiteness.

Assume , is finite. Then is a fixed positive constant, hence is fixed. Meanwhile is also fixed. The identity becomes a rational equality among strictly positive finite constants. But this equality must be compatible with the sign of (e.g. negative at ); when the decomposition is realized by finite sets, the resulting rational combination cannot produce the required analytic sign/phase (it stays on the “algebraic” positive side). This contradicts the actual value of .

A symmetric argument applies if is finite: then is fixed and must bear the entire analytic burden; again the finite rational identity cannot reproduce the analytic sign at . Therefore, both classes must be infinite.

Interpretation via classical pillars.

Pringsheim (nonnegative coefficients ⇒ real singular control): Positivity of coefficients yields rigid real-axis behavior of generating series; finite truncations cannot emulate the required analytic sign at .

Gap/lacunary theorems (Fabry/Hadamard): Attempting to realize the analytic function from a set with “large gaps” (finite or too-sparse) obstructs continuation/phase needed at ; an infinite contribution from both parts is necessary.

Tauberian philosophy (Wiener–Ikehara): Analytic constraints (here, the discriminant identity at a real point) force “density/infinity-type” conclusions for the underlying index sets. Thus both and must be infinite.

Corollary A (Intrinsic analytic density)

Under the hypotheses of

Theorem A, the intrinsic analytic Mersenne density

is well-defined with

. In particular,

cannot be realized by a finite index set on either side.

THEOREM: There exists an infinite number of Mersenne Primes.

Proof:

I start with the relationship between Perfect numbers and their sums of divisors. Let be a prime number such that Then the following applies.

Lemma 1:

If

Proof of LEMMA 1: See equation (19) for Perfect numbers.

Lemma 2:

Let p be a prime that generates a Mersenne prime and a Perfect Number N, then, there exits a unique decomposition of

into a quadratic identity

Proof (LEMMA 1):

Now, from [

4], p.42, 1.411 (7) we find an expressions for

:

We find that by chosing

, since (66) holds for

the expression can be modifed and separated into two class , one over the sum over Mersenne primes to include Perfect numbers,

when

, a prime for which

is a Mersenne prime, and the class of non-Mersenne primes, for

Put

in (67), then,

Now, we reduce (73) further with the following identities [[

4],page 41]:

Putting

,

Substitute expressions (74) into (73):

Note that the sum for the Perfect Numbers expressed in Mersernne Primes require a modification with a factor that is lost in (80) for the original sum defoinition for . This is where the result of in (19) comes into play.

However, by (H3), can only have one value, hence, we get:

Inserting the factor of 2 for the Mersenne primes again to make the sums as per the original

formula,

This is not possible since the sums are all positive quantities. It is clear that the contradiction results in negative sum of the Mersenne primes . The reasons are given below.

a) Discriminant condition.

For a single-valued analytic function tan(2), both roots of (83) must coincide, giving the constraint (84), i.e.

b) Finite-set contradiction.

Suppose either or is finite. If is finite, then is bounded and is strictly positive; hence , contradicting the analytic value … .

If is finite is finite, diverges, destroying convergence and violating the finite analytic value of .

Therefore, both subsets must extend infinitely.

c) Analytic necessity.

The negative finite value of arises from the conditional convergence of the full series. Only infinite, interleaved contributions from both classes can reproduce the correct analytic continuation through the real axis.

Finite truncations cannot yield the required sign reversal because all partial sums are positive.

d) Conclusion.

Hence, the equality (84) can hold with finite only if Therefore, both the Mersenne-prime and non-Mersenne classes are infinite classes.

Now an estimate of the Mersenne prime sum can be obtained if we consider:

Now,

hence,

Again a contradiction.