Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Plant Extract

4.3. Fractionation of Ethyl Acetate Fraction

4.4. Xanthine Oxidase (XO) Inhibitory Activity

4.5. Porcine Pancreatic a-Glucosidase Inhibition Assay

4.6. Porcine Pancreatic a-Amylase Inhibition Assay

4.7. Pharmaceutical compounds identification by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

4.8. Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) Analysis.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spivey, A.C.; Weston, M.; Woodhead, S. Celastraceae sesquiterpenoids: Biological activity and synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T.N.; Shimoyamada, M.; Yamauchi, R. Isolation and characterization of rosmarinic acid oligomers in Celastrus hindsii Benth leaves and their antioxidative activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3786–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.H.; Kuo, L.M.Y. Antitumour and anti-AIDS triterpenes from Celastrus hindsii. Phytochemistry. 1997, 44, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Viet, T.D.; Xuan, T.D.; Van, T.M.; Andriana, Y.; Rayee, R.; Tran, H.D. Comprehensive fractionation of antioxidants and GC-MS and ESI-MS fingerprints of Celastrus hindsii leaves. Medicines. 2019, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.Q.; Han, W.; Han, Z.Z.; Liu, Q.X.; Xu, X.K.; Fu, P.; Li, H.L. Three new diphenylpropanes from Celastrus hindsii. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.Q.; Han, W.; Han, Z.Z.; Liu, Q.X.; Xu, X.K.; Fu, P.; Li, H.L. Three new diphenylpropanes from Celastrus hindsii. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, P.; Vivekanandan, S. Urate crystal deposition, prevention and various diagnosis techniques of gout arthritis disease: A comprehensive review. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2018, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Chen, W.; Qiu, X.; Wang, W. Epidemiology of gout–Global burden of disease research from 1990 to 2019 and future trend predictions. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 15, 20420188241227295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.; Ong, K.L.; Culbreth, G.T.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Cousin, E.; Lenox, H.; Woolf, A.D. Global, regional, and national burden of gout, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2024, 6, e507–e517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xu, B.; Wu, G.; Yuan, Q.; Xue, X.; Mo, S. Global, regional, and national burden of gout in elderly 1990–2021: An analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. BMC Public Health. 2024, 24, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Nie, Q.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, Z. Assessing cross-national inequalities and predictive trends in gout burden: A global perspective (1990–2021). Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1527716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Reddy, S.G.; Kundukulam, J. Risk factors for gout and prevention: A systematic review of the literature. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2011, 23, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, B.; Just, J.; Bleckwenn, M.; Weckbecker, K. Treatment options for gout. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, B.K.; Akter, R.; Das, J.; Das, A.; Modak, P.; Halder, S.; Kundu, S.K. Diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 2362–2371. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, D.; Chavez, A.O. Defects in insulin secretion and action in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2010, 10, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezil, S.A.; Abed, B.A. Complication of diabetes mellitus. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Gangwar, R.; Ahmad Zargar, A.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, A. Prevalence of diabetes in India: A review of IDF diabetes atlas 10th edition. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2024, 20, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yameny, A.A. Diabetes mellitus overview 2024. J. Biosci. Appl. Res. 2024, 10, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogurtsova, K.; Guariguata, L.; Barengo, N.C.; Ruiz, P.L.D.; Sacre, J.W.; Karuranga, S.; Magliano, D.J. IDF diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, K.; Kirpich, A.; Chowell, G. The future diabetes mortality: Challenges in meeting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal of reducing premature mortality from diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaq, R.A.; Mahdi, J.A.; Jawad, R.A. Information about diabetes mellitus. J. Univ. Babylon Pure Appl. Sci. 2020, 28, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mutyambizi, C.; Booysen, F.; Stokes, A.; Pavlova, M.; Groot, W. Lifestyle and socio-economic inequalities in diabetes prevalence in South Africa: A decomposition analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0211208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Prasad, S.; Reuter, S.; Kannappan, R.; Yadav, V.R.; Park, B.; Sung, B. Identification of novel anti-inflammatory agents from Ayurvedic medicine for prevention of chronic diseases: “Reverse pharmacology” and “bedside to bench” approach. Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 1595–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.T.; Hai, N.D.; Nam, N.T.H.; Thanh, N.M.; Huyen, N.T.T.; Duong, L.T.T.; Hieu, N.H. Flavonoid content and antifungal activity of Celastrus hindsii leaf extract obtained by supercritical carbon dioxide using ethanol as co-solvent. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 52, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.L. An in silico approach for identification of potential therapeutic targets for cancer treatment from Celastrus hindsii Benth. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2024, 53, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiq, K.; Hussain, K.; Islam, M.; Shehzadi, N.; Ali, E.; Ashiq, S. Medicinal plants of Pakistan and their xanthine oxidase inhibition activity to treat gout: A systematic review. Turk. J. Bot. 2021, 45, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtoh, H.; Baek, K.H. Recent updates on phytoconstituent α-glucosidase inhibitors: An approach towards the treatment of type two diabetes. Plants. 2022, 11, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, M.; Polito, L.; Battelli, M.G.; Bolognesi, A. Xanthine oxidoreductase: One enzyme for multiple physiological tasks. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.A.; Althumali, J.S.; Almalki, M.M.M.; Almasoudi, A.S.; Almuntashiri, A.H.; Mahzari, M.A.H. An overview on the role of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in gout management. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 12, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J. The starch hydrolysis and aroma retention caused by salivary α-amylase during oral processing of food. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, S.; Warren, F.J.; Butterworth, P.J.; Ellis, P.R.; Gidley, M.J. Mechanisms of starch digestion by α-amylase—Structural basis for kinetic properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyoshi, T.; Fujiwara, M.; Yao, Z. Postprandial hyperglycemia and postprandial hypertriglyceridemia in type 2 diabetes. J. Biomed. Res. 2019, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartini, S.; Juariah, S.; Mardhiyani, D.; Bakar, M.F.A.; Bakar, F.I.A.; Endrini, S. Phytochemical properties, antioxidant activity and α-amylase inhibitory of Curcuma caesia. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 30, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Jin, Z.; Svensson, B. Food-derived non-phenolic α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors for controlling starch digestion rate and guiding diabetes-friendly recipes. LWT. 2022, 153, 112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Mishra, A. α-Glucosidase inhibitors for diabetes/blood sugar regulation. In Natural Products as Enzyme Inhibitors: An Industrial Perspective. Springer Nature: Singapore.

- Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Jin, Z.; Svensson, B. Food-derived non-phenolic α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors for controlling starch digestion rate and guiding diabetes-friendly recipes. LWT. 2022, 153, 112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromova, L.V.; Fetissov, S.O.; Gruzdkov, A.A. Mechanisms of glucose absorption in the small intestine in health and metabolic diseases and their role in appetite regulation. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjita, I.P.D.; Yasa, I.W.P.S.; Dewi, N.N.A.; Satriyasa, B.K.; Suastika, K.; Saraswati, M.R.; Saputra, I.P.B.A. Potential α-glucosidase inhibitor in Nyale worm (Eunice sp.) extract for anti-diabetic type 2 target. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2024, 15, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.H.; Farhadi, N.F.; Smith, T.J. Slowing starch digestion and inhibiting digestive enzyme activity using plant flavanols/tannins A review of efficacy and mechanisms. LWT. 2018, 87, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, R.P.; Babu, R.J.; Srinivas, N.R. Reappraisal and perspectives of clinical drug–drug interaction potential of α-glucosidase inhibitors such as acarbose, voglibose and miglitol in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Xenobiotica. 2018, 48, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, B.S.; Edelman, S.V.; Wolosin, J.D. Gastrointestinal complications of diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 42, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtoh, H.; Baek, K.H. Recent updates on phytoconstituent α-glucosidase inhibitors: An approach towards the treatment of type two diabetes. Plants 2022, 11, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinita, M.D.N.; Harwanto, D.; Tirtawijaya, G.; Negara, B.F.S.P.; Sohn, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.S. Fucosterol of marine macroalgae: Bioactivity, safety and toxicity on organism. Mar. Drugs. 2021, 19, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, Q.A.; Choi, R.J.; Jung, H.A.; Choi, J.S. Health benefit of fucosterol from marine algae: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, B.K.; Lee, S. Anti-diabetic activities of fucosterol from Pelvetia siliquosa. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2004, 27, 1120–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourelle, M.L.; Gómez, C.P.; Legido, J.L. Role of algal derived compounds in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. In Recent Advances in Micro and Macroalgal Processing: Food and Health Perspectives. 2021, 537- 603.

- Hwang, J.; Kim, M.B.; Lee, S.; Hwang, J.K. Fucosterol, a phytosterol of marine algae, attenuates immobilization-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in C57BL/6J mice. Mar. Drugs. 2024, 22, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato, M.T.; Jiménez, N.; Pelechá, M.; Tolosa, L. Oxidative-stress and long-term hepatotoxicity: Comparative study in Upcyte human hepatocytes and HepaRG cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi, H.K.; Alwan, N.A.; Al-Masoudi, E.A. Physiological and biochemical effect of α-amyrin: A review. J. Med. Life Sci. 2024, 6, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, T.D.; Xuan, T.D.; Anh, L.H. α-Amyrin and β-amyrin isolated from Celastrus hindsii leaves and their antioxidant, anti-xanthine oxidase, and anti-tyrosinase potentials. Molecules. 2021, 26, 7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, T.D.; Anh, L.H.; Xuan, T.D.; Dong, N.D. The pharmaceutical potential of α- and β-amyrins. Nutraceuticals. 2025, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.A.; Frota, J.T.; Arruda, B.R.; de Melo, T.S.; da Silva, A.A.C.A.; Brito, G.A.C.; Rao, V.S. Antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of α,β-amyrin, a triterpenoid mixture from Protium heptaphyllum in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, P.; Reeta, K.H.; Maulik, S.K.; Dinda, A.K.; Gupta, Y.K. α-Amyrin attenuates high fructose diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureka, D.; Sam Rosan, Y.; Avinash, B.; Blessy Victa, N.I.; Christi, V.I. A mechanism-based comparative review on functional food with phytomolecules and marketed formulation for type II diabetes mellitus. Curr. Funct. Foods. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Ferreira, R.G.; Guilhon-Simplicio, F.; Acho, L.D.R.; Batista, N.Y.; do Carmo Guedes-Junior, F.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Lima, E.S. Anti-hyperglycemic, lipid-lowering, and anti-obesity effects of the triterpenes α- and β-amyrenones in vivo. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2021, 11, 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J. β-Amyrin ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in mice and regulates the miR-181b-5p/HMGB2 axis in high glucose-stimulated HK-2 cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, T.F.; Krishna, K.L.; Shakeel, F. Synergistic modulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway, oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis by β-amyrin and metformin in mitigating hyperglycemia-induced renal damage using adult zebrafish model. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 25, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomazi, R.; Figueira, Â.C.; Ferreira, A.M.; Ferreira, D.Q.; de Souza, G.C.; de Souza Pinheiro, W.B.; da Silva de Almeida, S.S.M. Hypoglycemic activity of aqueous extract of latex from Hancornia speciosa Gomes: A study in zebrafish and in silico. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.A.; Sabulal, B.; Radhika, J.; Arunkumar, R.; Subramoniam, A. Promising anti-diabetes mellitus activity in rats of β-amyrin palmitate isolated from Hemidesmus indicus roots. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 734, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriana, Y.; Xuan, T.D.; Quy, T.N.; Minh, T.N.; Van, T.M.; Viet, T.D. Antihyperuricemia, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities of Tridax procumbens L. Foods. Foods. 2019, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, L.T.T.; Son, N.T.; Van Tuyen, N.; Thuy, P.T.; Quan, P.M.; Ha, N.T.T.; Tra, N.T. Antioxidative and α-glucosidase inhibitory constituents of Polyscias guilfoylei: Experimental and computational assessments. Mol. Divers. 2022, 26, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, N.V.; Xuan, T.D.; Tran, H.D.; Thuy, N.T.D.; Trang, L.T.; Huong, C.T.; Tuyen, P.T. Antioxidant, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities and potential constituents of Canarium tramdenum bark. Molecules. 2019, 24, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubaye, A.F.; Hameed, I.H.; Kadhim, M.J. A review: Uses of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) technique for analysis of bioactive natural compounds of some plants. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 9, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, G.R.D.; Williams, E.R.; Wilm, M.; Urban, P.L. Mass spectrometry using electrospray ionization. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers. 2023, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extract | IC50 XO Inhibition (µg /mL) |

IC50 α-Glucosidase Inhibition (µg /mL) |

IC50 α-Amylase Inhibition (µg /mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EtAOC | 114.06 ± 7.04c | 363.46 ± 1.55a | 689.09 ± 2.09 a |

| Aqueous | 410.81 ± 6.89b | - | - |

| Haxane | 621.11 ± 16.36a | - | - |

| Allopurinol | 6.06 ± 0.38d | - | - |

| Acarbose | - | 141.06 ± 0.64b | 74.18 ± 4.21b |

|

Fractions |

IC50 XO Inhibition (µg/mL) |

IC50 α-Glucosidase Inhibition (µg/mL) |

IC50 α-Amylase Inhibition (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| V2 | - | 128.00 ± 7.12c | 597.38 ± 3.94a |

| V4 | - | 185.00 ± 2.30a | |

| V5 | 38.22 ± 3.17a | 68.00 ± 3.30d | 292.33 ± 7.80b |

| Allopurinol | 7.58 ± 1.29b | - | |

| Acarbose | - | 145.06 ± 6.43b | 74.18 ± 4.2c |

| Fraction | Time (min) |

Area (% of total) |

Compounds | Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

Chemical Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

V2 |

21.27 | 32.17 | Fucosterol | C29H48O | 412.70 | Phytosterols |

| 29.04 | 25.66 | β-Amyrin | C30H50O | 426.70 | Triterpene | |

| 29.67 | 36.09 | α-Amyrin | C30H50O | 426.70 | Triterpene | |

| V4 | 2.64 21.28 29.03 29.64 |

1.25 38.64 25.56 32.71 |

Fucosterol Hydrazinecarboxamide β-Amyrin α-Amyrin |

C29H48O CH5N3O |

412.70 | Phytosterols |

| 75.07 | Amino | |||||

| C30H50O | 426.70 | Triterpene | ||||

| C30H50O | 426.70 | Triterpene | ||||

| 21.28 | 34.22 | Bauerenol | C30H50O | 426.70 | Triterpenoid | |

| V5 | 21.45 | 43.62 | Fucosterol | C29H48O | 412.70 | Sterol |

| 22.10 | 4.78 | β-Amyrin | C30H50O | 426.70 | Triterpene | |

| 29.68 | 8.55 | α-Amyrin | C30H50O | 426.70 | Triterpene |

|

Fractions |

IC50 XO Inhibition (µg /mL) | IC50 α-Glucosidase Inhibition (µg /mL) |

IC50 α-Amylase Inhibition (µg /mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fucosterol | 5.28 ± 1.22b | 58.22 ± 2.18b | 88.55 ± 2.88a |

| Allopurinol | 7.58 ± 1.05a | - | - |

| Acarbose | - | 155.28 ± 5.88a | 72.25 ± 2.25c |

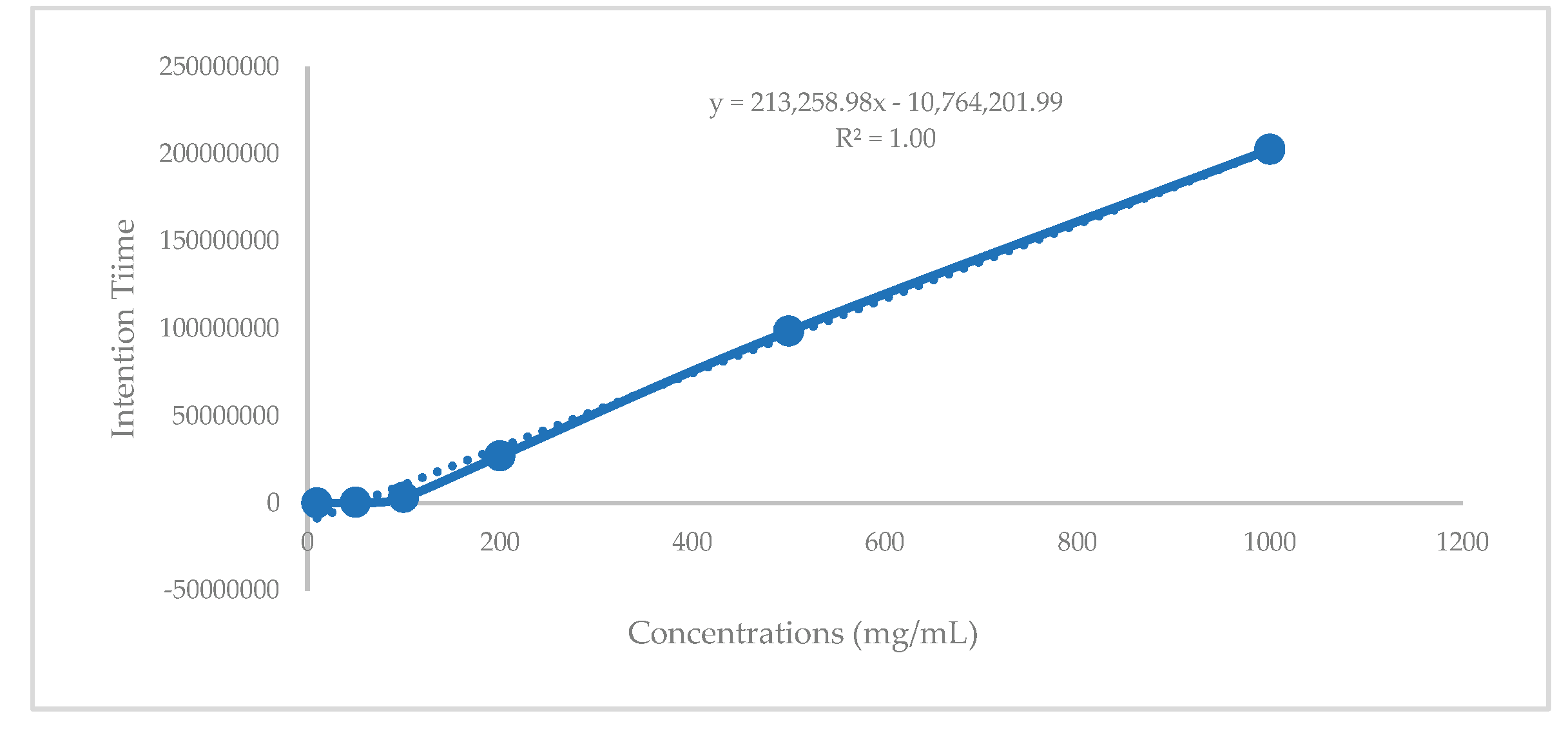

| Fractions | Intention Time (Second/ g) |

Concentration (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| V2 | 98412933.03 | 0.51 |

| V4 | 168641969.5 | 0.84 |

| V5 | 221163634 | 1.08 |

| Total in leaves of C.hindsii | (2.03 mg/ kg extract) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).