1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction is a challenging ill-posed problem that has been approached from multiple perspectives using various techniques to recover accurate geometric representations of real-world environments. Previously, researchers have proposed solving this problem using different sensors, such as lasers, infrared, radars, LIDARs, and cameras, as well as combinations of these sensors, including additional sensors like GPS and INS [

1,

2,

3]. Due to notable improvements in computer vision over the past few decades, cameras have become a precise alternative for solving this problem. For 3D reconstruction, cameras can be used in stereo arrays that favor pixel triangulation, with additional active sensors such as infrared, active, and passive sensors, as well as RGB-D cameras. They can also be combined with inertial INS sensors or used alone [

4]. The most interesting input modality for many researchers is the monocular RGB camera because of its low price, availability in most portable devices (like smartphones, tablets, and laptops), and independence from additional sensors (like infrared and laser sensors) that limit their application to large environments. Using a monocular camera as the sole source of information is convenient for many applications. However, it presents a more complex problem due to its lack of real-world prior information, such as depth or scale. Consequently, these methods typically require more effort and computational power. This is why all monocular, pure visual methods are scale-ambiguous—one of their main disadvantages compared to stereo, RGB-D, or RGB-INS methods—and it is considered one of the main sources of drift. Thus, the present work aims to address these issues by incorporating depth-prior information into a popular monocular RGB system.

The 3D reconstruction corresponds to the mapping process, which is typically an output of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM), Visual Odometry (VO), and Structure from Motion (SFM). Multiple studies have contributed to improving this task because accurate mapping significantly improves the performance of SLAM, VO, and SFM systems, even for methods focused on ego-motion estimation. Most systems perform tracking from the geometry map, and it has been proven that it is easier to solve both tracking and mapping problems jointly [

1,

2]. As mentioned in the previous study [

5], SLAM, VO, and SFM can be categorized into three groups: direct vs. indirect, dense vs. sparse, and classic vs. machine learning based. Indirect methods use preprocessing to extract visual features or optical flow from each image, considerably reducing the amount of information and allowing only sparse representations of the scene geometry to be obtained. In contrast, direct methods work directly with pixel intensities, allowing those systems to work with more image information, though this increases computation cost. Dense methods refer to algorithms that can recover most of the scene geometry, typically entire structures, objects, or surfaces. In contrast, sparse methods work with less information and can only recover sparse point clouds representing the environment. Finally, classic methods are those that depend entirely on mathematical, geometric, optimization, or probabilistic techniques without including machine learning (ML).

Consequently, ML methods correspond to proposals based on classic formulations that include ML techniques to improve the performance of each system from different perspectives. Recent advances in transformer-based architectures have revolutionized monocular depth estimation, with methods such as AdaBins [

6] introducing adaptive binning strategies that leverage transformer encoders for global depth distribution analysis, and Dense Prediction Transformers (DPT) [

7] demonstrating how vision transformers can provide fine-grained and globally coherent depth predictions. Additionally, reinforcement learning approaches have emerged as promising alternatives for visual odometry optimization, particularly in keyframe selection and feature management strategies that enhance traditional geometric methods [

8]. Furthermore, multi-scale feature pyramid networks have been developed to improve monocular depth estimation through enhanced spatial and semantic information fusion across different resolution levels [

9]. The taxonomy for SLAM, VO, and SFM methods suitable for the 3D reconstruction problem was proposed in [

5] and is formed by combining the following classifications: Classic-Sparse-Indirect [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], Classic-Dense-Indirect [

16,

17], Classic-dense-direct [

18,

19,

20], Classic-Sparse-Direct [

21,

22,

23], Classic-Hybrid [

24], ML-sparse-indirect [

25,

26,

27], ML-dense-indirect [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], ML-dense-direct [

33,

34,

35,

36], ML + classic-sparse-direct [

37,

38,

39,

40], and ML-hybrid [

41]. Additionally, previous work [

42] evaluated different open-source methods across the entire taxonomy using an appropriate, large monocular benchmark [

43] to identify significant differences in performance among taxonomy categories and their respective advantages and shortcomings. That study identified that sparse direct methods significantly outperform the other taxonomy categories. They achieved the lowest translation, rotation, and scale errors, as well as the lowest alignment root mean square error (RMSE) over the 50 sequences of the TUM-Mono dataset [

43].

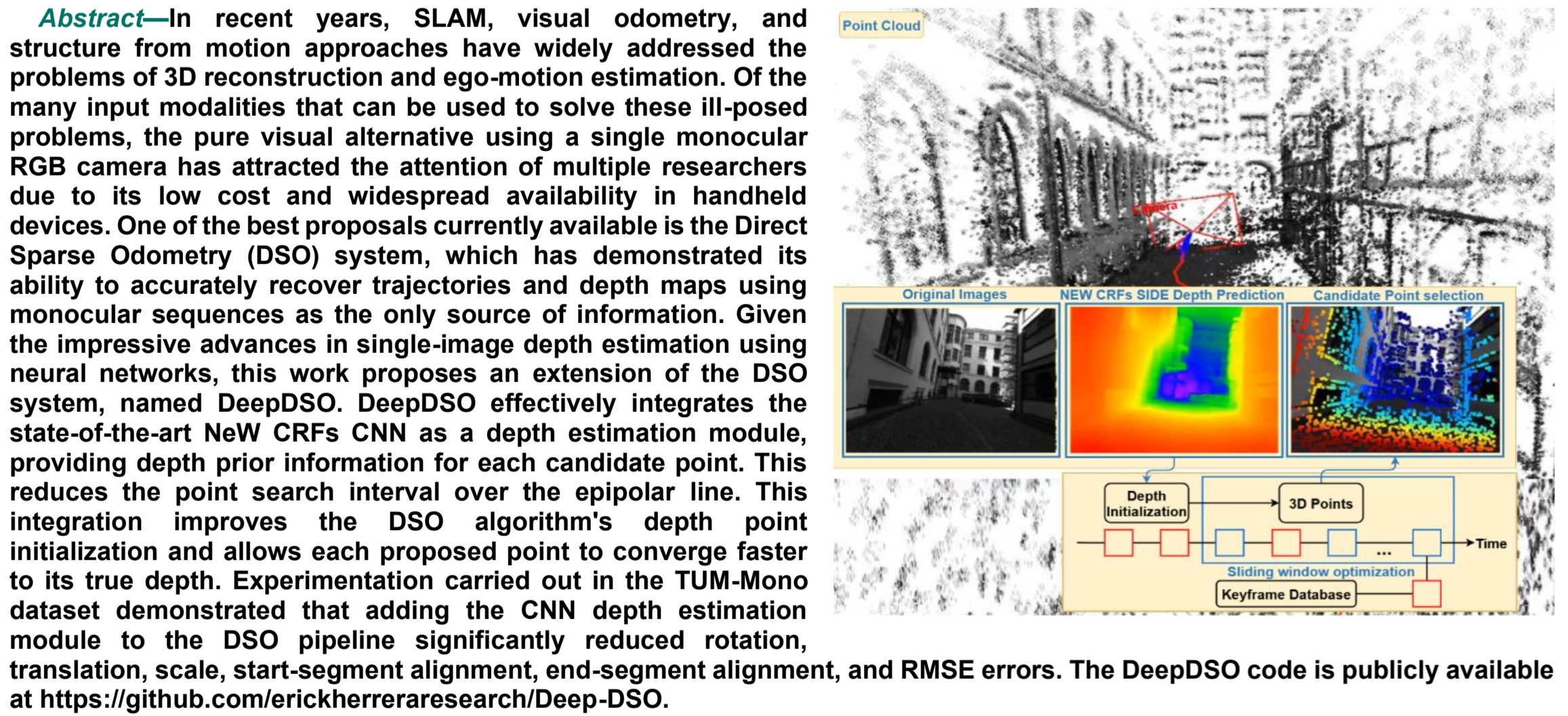

For these reasons, we selected the classic sparse direct method, DSO, one of the best classic methods available. We propose improving its depth map estimation module by integrating a Single Image Depth Estimation (SIDE) Neural Network (NN) module. The SIDE-NN module takes a single image as input and estimates the depth of each pixel, returning a numeric value for each pixel in a matrix. This improves the mapping capabilities of the DSO method and provides an accurate, scaled reconstruction

1 using pixel-wise prior depth information estimated by the network. We selected the NeW CRFs SIDE technique because it was the state of the art in deep learning-based monocular depth estimation when the Deep-DSO method was developed. Experimental results show that DeepDSO outperformed its classic version in the rotation, translation, scale, and RMSE metrics by adding the NeW CRFs CNN module.

2.1. Related Works

Some proposals aim to improve the performance of sparse-direct methods by including a convolutional neural network (CNN) in their pipeline [

37,

38,

39,

40]. These methods have been integrated for disparity map estimation [

44], replacing the depth estimation module with a CNN [

45], joint depth, pose, and uncertainty estimation [

38], depth mask estimation for moving object detection and segmentation [

39], and pose transformation estimation [

40]. Nevertheless, none of these studies have thoroughly investigated the potential of incorporating prior depth information to constrain the point search interval along the epipolar line, as outlined in [

41], which was successfully applied to the SVO hybrid approach. Thus, the most similar related work to our approach is the CNN-SVO proposed in [

41]. It took the SVO hybrid system and implemented a single-image depth estimation module to improve the depth estimation process. This process was originally computed incrementally using a Gaussian formulation for depth estimation and a Beta distribution for the inlier ratio. In the original SVO, the beta distribution parameters are calculated using incremental Bayesian updates and depth filters that converge when the variance is lower than a threshold. The CNN-SVO authors, however, proposed reducing the epipolar point search interval in the next frame by using the mean and variance of the inverse depth calculated from each pixel depth obtained by the SIDE-NN module. This allowed the SVO method to converge faster to true depth and achieve better scaling in the reconstruction. The open-source code CNN-DSO, published in [

46], applied the same approach as CNN-SVO to the DSO algorithm using MonoDepth [

47] SIDE depth estimation. However, the code did not correctly follow the proposal of [

41], so it did not significantly outperform the DSO algorithm [

42]. In contrast to this approach, we successively integrated Loo’s method [

41] into the original DSO system. We also used the state-of-the-art SIDE-NN NeW CRFs, which significantly improved the performance of the sparse-direct method.

DeepDSO is distinguished from CNN-DSO by its successful integration, which extends beyond merely replacing the SIDE architecture through three critical contributions to the framework. First, we preserved the probabilistic Gaussian depth filtering framework of DSO by initializing the depth filter parameters with SIDE-NN predictions rather than replacing depth values directly. This maintains the capability of uncertainty-based inference. Second, we implemented epipolar search interval constraints that are theoretically grounded and operate through Bayesian inference, optimization regularization, and geometric filtering mechanisms. Third, we rigorously calibrated the variance coefficient through an experimental analysis to balance accommodating neural network predictions and preventing outliers. These integration mechanisms explain why the original DSO significantly outperformed CNN-DSO in rotation and alignment metrics despite the latter incorporating neural depth priors. Meanwhile, DeepDSO achieved substantial improvements, demonstrating that proper framework integration is as critical as depth estimation accuracy.

3. Results

The DSO and NeW CRF SIDE-NN integration was developed using the C++ and Python programming languages on the Ubuntu 18.04 operating system. For implementation and evaluation purposes, we selected affordable, readily available computer components to assemble a desktop based on the AMD Ryzen™ 7 3800X processor and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU. The technical specifications of the hardware used for evaluation are presented in

Table 2.

In the previous study [

42], ten open-source algorithms from each taxonomy category were tested using the monocular benchmark from [

43]. This study demonstrated that sparse-direct methods significantly outperformed state-of-the-art methods. For this reason, this work is based on the classic sparse-direct method DSO due to its impressive results for monocular reconstruction. Thus, we compared the original DSO [

21] and its ML update, CNN-DSO [

42], to test whether the proposed method, DeepDSO, significantly outperforms the classic version and whether the newest NeW CRFs SIDE-NN significantly improves the performance of the sparse-direct method. DSO and CNN-DSO are both publicly available on GitHub as open-source code [

46,

70] and can be implemented with minimal requirements, including Pangolin V0.5 [

71], OpenCV V3.4.16, TensorFlow V1.6.0, and the C++ version of MonoDepth [

72], which is faster than its original Python implementation.

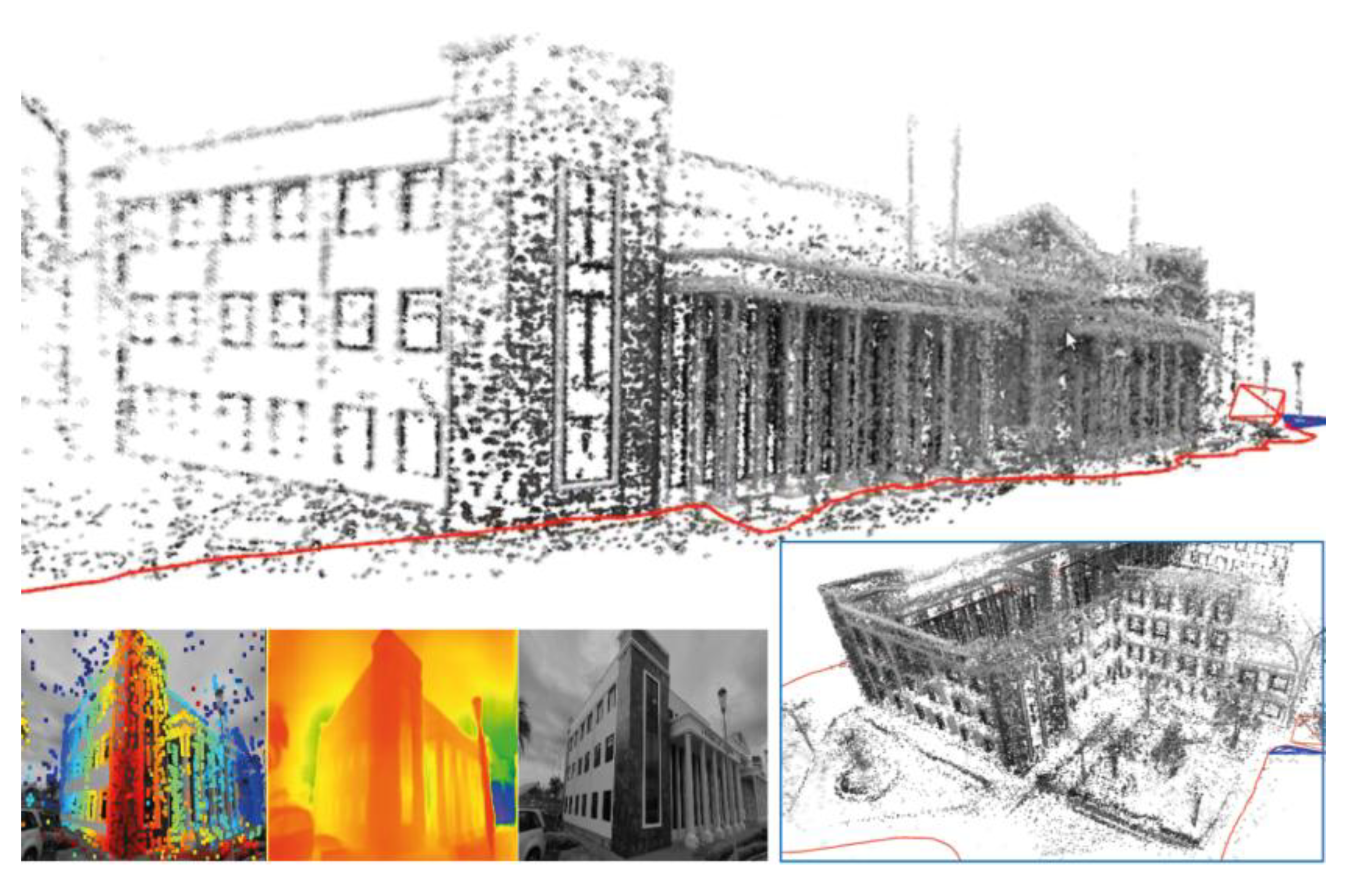

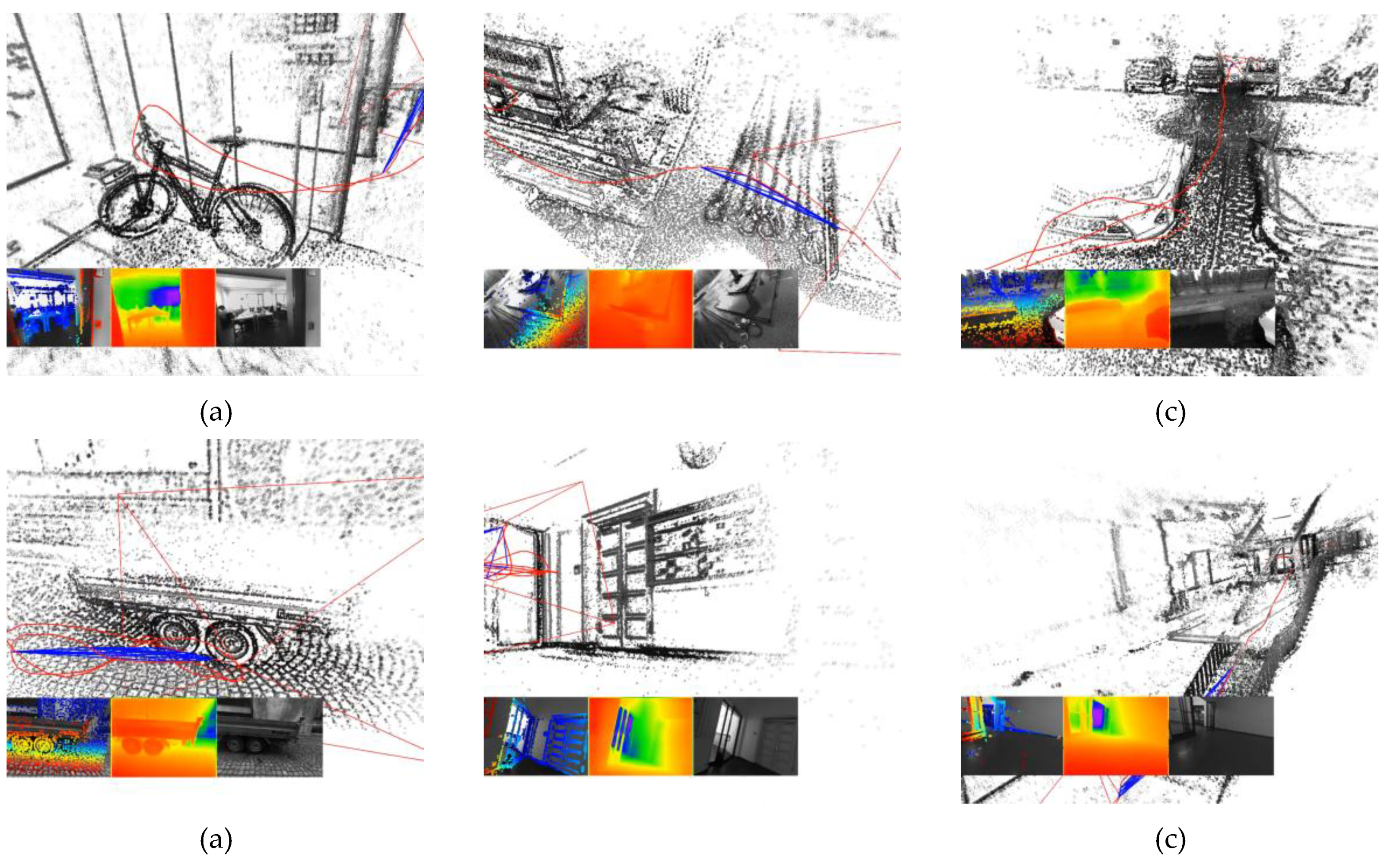

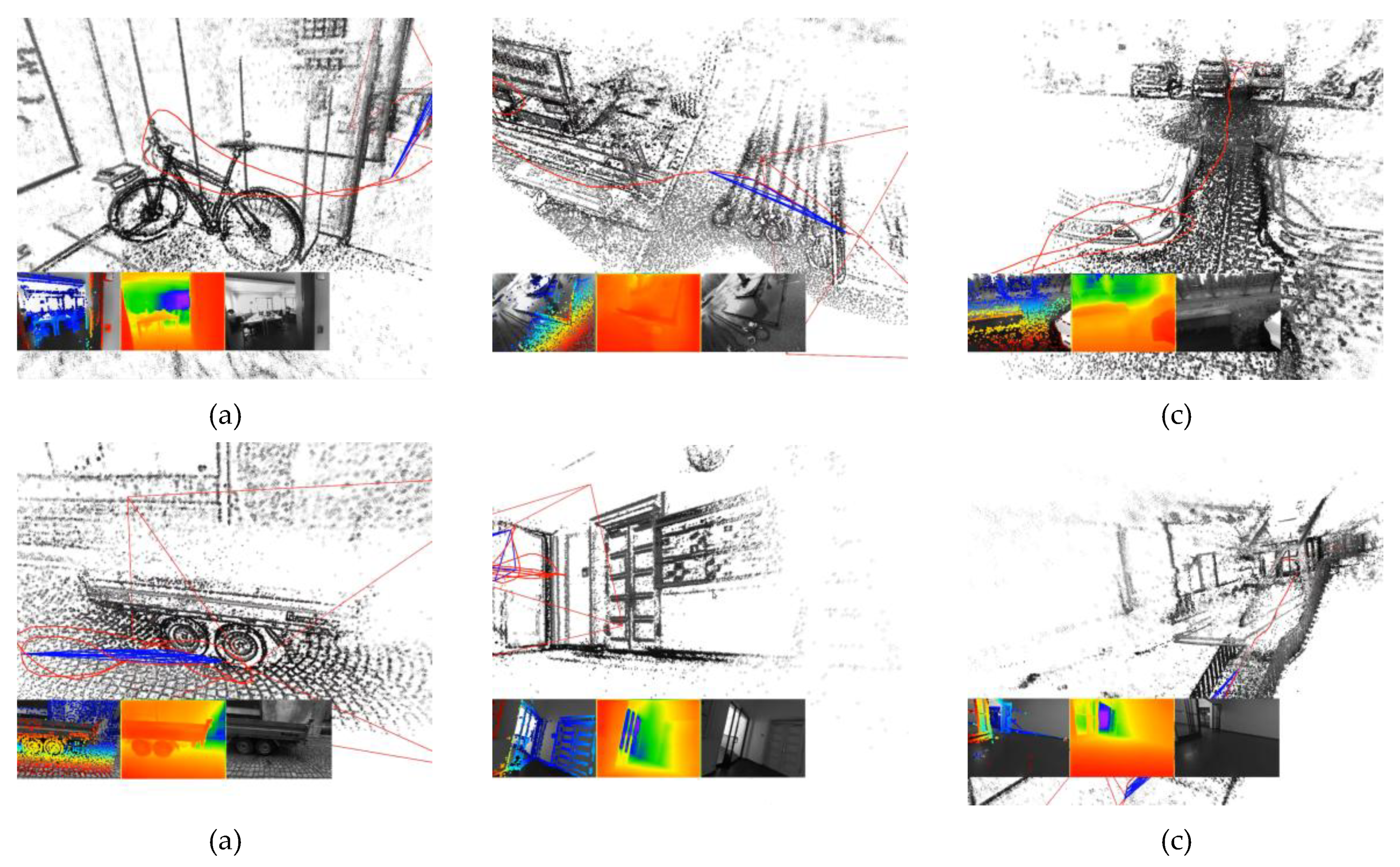

Figure 4 shows examples of 3D reconstructions obtained using the DeepDSO algorithm.

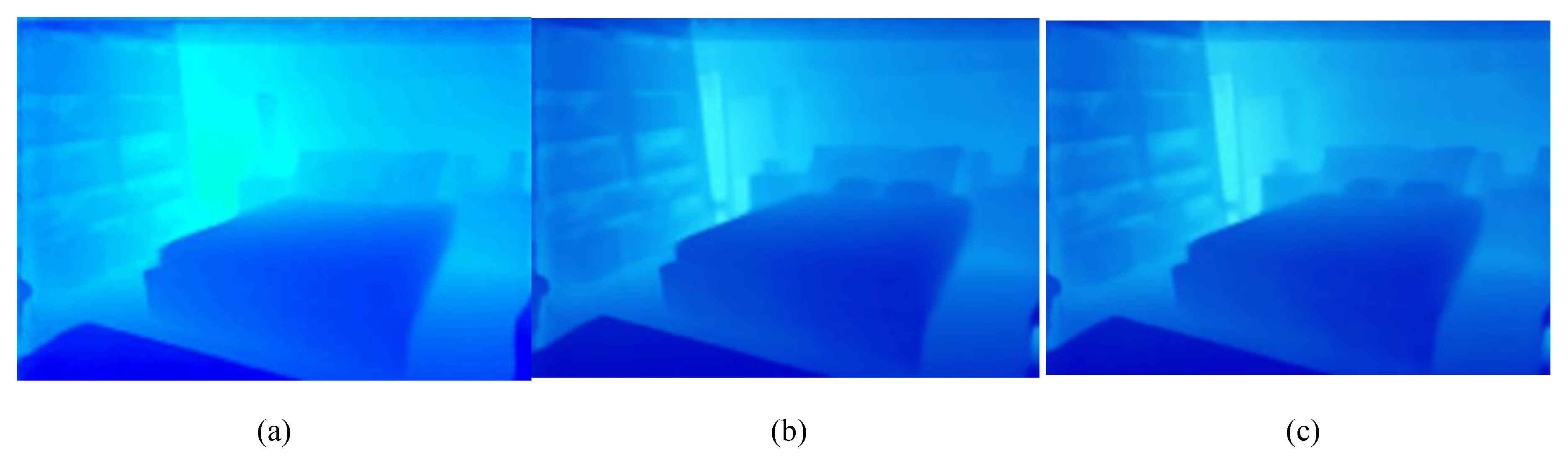

Figure 5 compares the three implementations running in the same sequences, both indoors and outdoors.

As

Figure 5 shows, the DeepDSO algorithm considerably improves the mapping results. In the top row, which belongs to sequence_01 of the TUM-Mono dataset, the addition of the MonoDepth CNN to CNN-DSO reduces the mapping quality of DSO. This may be primarily because its integration did not follow the point search recommendations on the epipolar line provided in [

41]. Additionally, the precision of the MonoDepth CNN is considerably lower than that of NeW CRFs, causing CNN-DSO to produce reconstructions with a large number of outliers. Additionally, DeepDSO recovers slightly denser and more precise reconstructions due to its improved depth initialization strategy for candidate points in keyframes, which allowed these points to converge faster to their true depth. Similarly, the bottom row of

Figure 5 presents an outdoor example for

, where DeepDSO again recovers slightly denser, more precise, and scaled reconstructions. In contrast, the previous neural proposal (CNN-DSO) recovers sparser reconstructions with a considerable number of outliers. MonoDepth CNN recovers depth maps of lower quality than NeW CRFs.

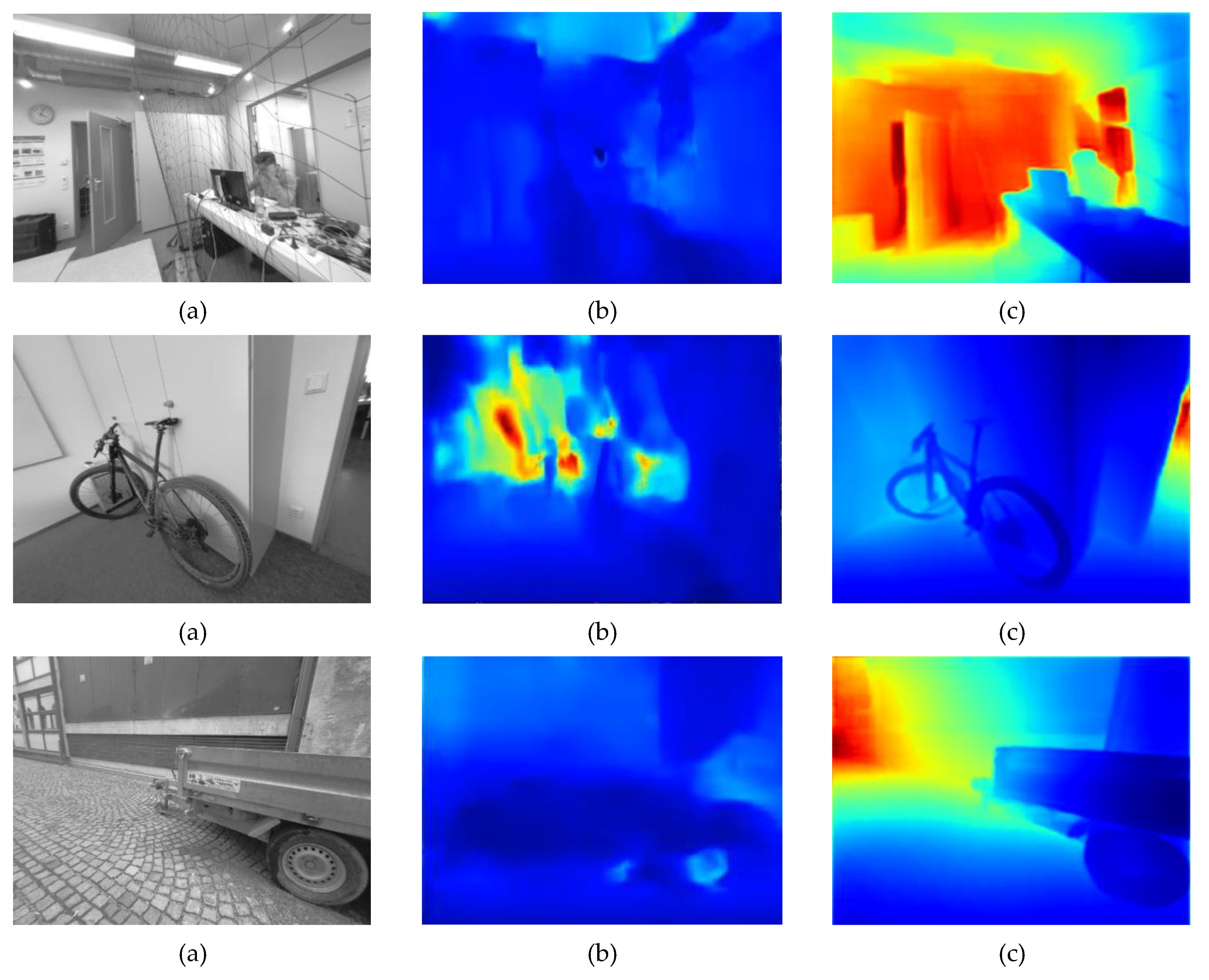

Figure 6 presents this effect in more detail.

Figure 6 shows that the per-pixel depth estimation task has improved significantly in recent years. This improvement is evident in the newer SIDE NeW CRFs, which perform considerably better than MonoDepth, allowing for more precise, detailed, consistent, and reliable depth estimation.

Figure 6b shows examples of MonoDepth SIDE, which performs poor depth estimation compared to the NeW CRFs, especially in the TUM-Mono dataset, which has different camera calibration than the Cityscapes dataset [

73] (where MonoDepth was trained). Despite using the camera calibration compensation formula described in (11) [

41], CNN-DSO remains incompatible with TUM-Mono 640×480 rectified images.

where

represents the scaled estimated depth and

is the focal length ratio for the current camera and the camera used in the training dataset. Additionally, the superior performance of NeW CRFs over previous SIDE proposals is justified in [

66].

For the evaluation of visual SLAM and VO systems, many benchmarks have been collected and proposed in recent years, such as [

43,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82]. However, only a few of these are designed specifically for evaluating monocular RGB systems and were recorded using monocular cameras. Of these, we considered: The KITTI dataset [

76], which contains 21 video sequences of a driving car; the EUROC-MAV dataset [

77], which contains 11 inertial stereoscopic sequences of a flying quadcopter; the TUM-Mono dataset [

43], which contains 50 sequences comprising indoor and outdoor examples with more than 190,000 frames and over 100 minutes of video; and the ICL-NUIM dataset [

74], which comprises eight video sequences of two environments with their respective ray tracing. Among the datasets suitable for evaluating monocular RGB systems, the TUM-Mono dataset is the most complete. It is also the most compatible with sparse-direct systems because it provides full photometric calibration information for the cameras, which is useful for these systems.

This investigation focuses on reconstructing indoor and outdoor scenarios from handheld monocular sequences with loop-closure characteristics typical of pedestrian navigation. While established benchmarks such as KITTI (automotive driving), EuRoC (aerial navigation), and ICL-NUIM (synthetic environments) provide valuable evaluation frameworks, their motion patterns and environmental conditions fall outside our current scope. Therefore, the TUM-Mono dataset was selected as it specifically addresses handheld monocular sequences captured by walking persons in closed-loop trajectories. Future research will evaluate the approach on automotive and aerial benchmarks to assess generalizability across diverse motion patterns. This dataset enabled comprehensive evaluation of currently available monocular sparse-direct methods [

21,

22,

83,

84,

85].

As previously mentioned, the performance of the monocular RGB method can be evaluated from different perspectives. For instance, scene geometry can be represented as structures, surfaces, or point clouds, which can be dense or sparse. Therefore, to make an accurate comparison, a good, defined ground truth is required. However, dense and accurate point clouds are difficult to obtain and are not included in existing benchmarks. As proposed in [

43,

83,

84,

86], the estimated trajectory is the best way to evaluate monocular RGB methods because most SLAM and VO approaches use a 3D reconstruction map to estimate camera pose from known features and points. Thus, a better-estimated trajectory implies an accurate map. The TUM-Mono benchmark provides the most complete set of metrics for evaluating pure visual systems. It evaluates each monocular system in multiple dimensions. In contrast, [

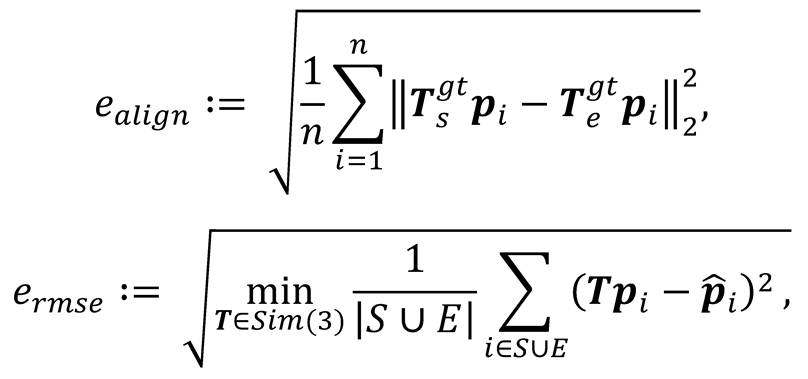

86] only proposes two metrics: the absolute trajectory root mean square error (ATE) and the relative pose root mean square error (RPE) for evaluating pose and trajectory. The TUM-Mono benchmark considers the following metrics:

Start and end segment alignment error. Each experimental trajectory was aligned with ground truth segments at both the start (first 10-20 seconds) and end (last 10-20 seconds) of each sequence, computing relative transformations through

optimization:

Translation, rotation and scale error: From these alignments, the accumulated drift was computed as

, enabling the extraction of translation, rotation and scale error components across the complete trajectory.

Translational RMSE: The TUM-Mono benchmark authors also established a metric that equally considers translational, rotational, and scale effects. This metric, named alignment error (), can be computed for the start and end segments. Furthermore, when calculated for the combined start and end segments, is equivalent to the translational RMSE:

where

are the estimated tracked positions for the

to

frames,

and

are the frame indices corresponding to the start- and end-segments for the ground truth positions

. As can be seen, the TUM-Mono benchmark is ideal for monocular comparisons, particularly for sparse-direct systems. This is because the benchmark was entirely acquired using monocular cameras and the ground truth was registered by a monocular SLAM system. Additionally, it enables the comparison of SLAM and VO systems from multiple dimensions, both separately and in conjunction. For this reason, we used this benchmark to test the performance of our DeepDSO proposal.

We evaluated DeepDSO by comparing it with its classic version, DSO, and its neural update, CNN-DSO. As recommended in [

21,

43,

83,

84], we tested each algorithm in each of the 50 sequences of the TUM-Mono benchmark. We ran each algorithm ten times forward and ten times backward, for a total of 1,000 runs per algorithm and 3,000 runs for the entire evaluation. The results obtained in each run were stored in a

file in the format

, gathering each tracked position

and its corresponding quaternion

at each timestamp

. We processed the trajectory results in MATLAB using the official scripts provided in the TUM-Mono benchmark.

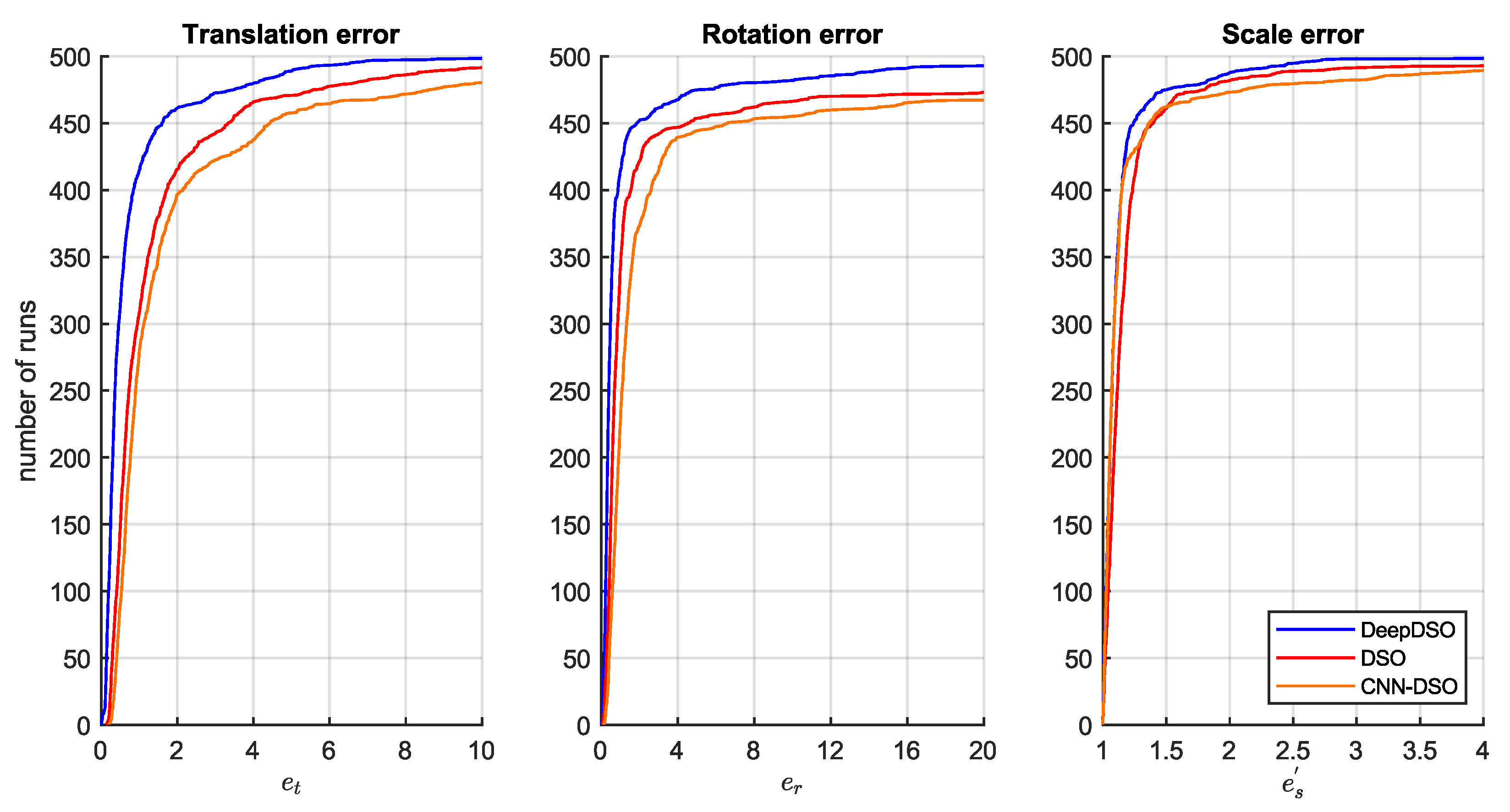

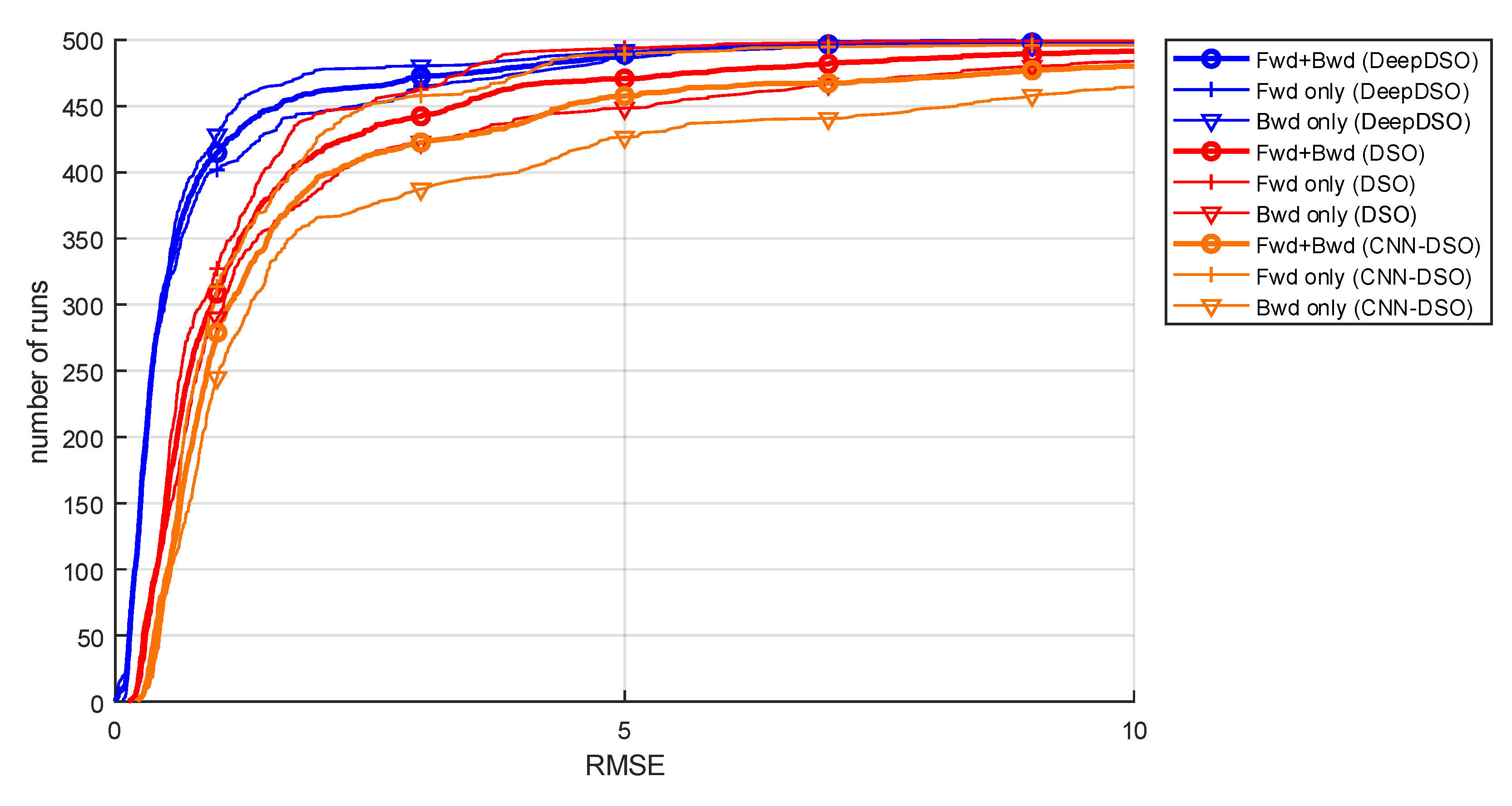

Figure 7 shows the cumulative translation, rotation, and scale errors obtained from 500 runs of each algorithm.

Figure 7 shows the accumulated error achieved by the algorithms over 500 runs. The y-axis represents the number of runs, and the x-axis represents the accumulated error achieved by each method after a certain number of runs. Thus, the best methods should be in the top-left corner of each diagram.

Figure 4 shows that the DeepDSO algorithm outperforms the DSO and CNN-DSO methods in translation, rotation, and scale error metrics. This suggests that adding the NeW CRFs SIDE-NN module to the DSO framework improves its performance, achieving better-scaled reconstructions and recovering accurate trajectories and rotations. This is evident in the reduction of translation, rotation, and scale errors. However, the CNN-DSO update that included the MonoDepth SIDE module did not outperform the original DSO system, which gathered the largest amount of translation, rotation, and scale error. Additionally,

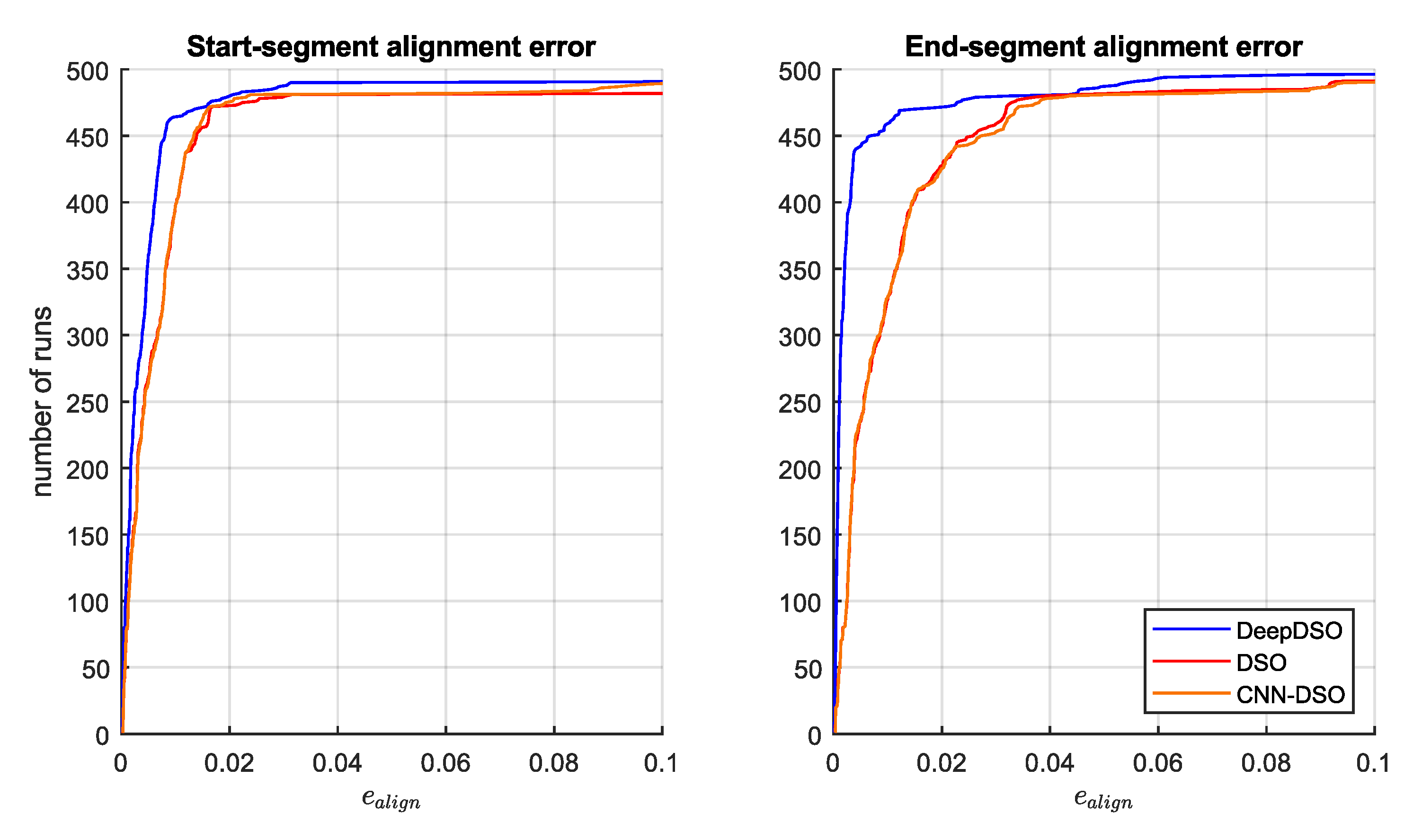

Figure 8 presents the alignment error, which represents these effects in a single metric for the start and end segments.

As shown in

Figure 8, DeepDSO performed better than the other methods for the alignment metrics at the start and end of the segments. This demonstrates that the addition of the NeW CFRs SIDE-NN module considerably improved the DSO system during the bootstrapping stage. This improvement is due to the NeW CFRs SIDE-NN's enhanced point initialization technique, which reduces the search interval over the epipolar line for the next frame, allowing the true depth to converge faster. Additionally, DeepDSO considerably reduced errors in the last segment. This means the improved depth initialization technique continued to contribute to better overall algorithm performance by reducing drift in each pose through more accurate depth and pose estimation. This is reflected in the final segment, which shows significant drift reduction. It should be noted that CNN-DSO exhibited a slight reduction in alignment error in the initial segment compared to DSO. This indicates that the addition of MonoDepth SIDE improves the initialization process for DSO. However, the considerable presence of outliers affected its performance throughout the rest of the trajectory, producing a higher end-segment alignment error. Next, we evaluated the effect of motion bias for the three algorithms by comparing the performance of each method when running forward and backward, and measuring their combined effect.

Figure 9 presents motion bias for DeepDSO, DSO, and CNN-DSO.

The motion bias effect was defined in [

43] as the behavior of a monocular SLAM or VO system in different environments and with different motion patterns. As

Figure 9 shows, DeepDSO exhibits a lower motion bias effect than the other tested algorithms. This indicates more robust and reliable performance with different motion patterns and changes, such as fast movements, strong rotations, and textureless surfaces. This can be attributed to the addition of a SIDE-NN module, which allows the DSO system to recover better, scaled information of each environment. This effectively limits the introduction of outliers and noisy estimations, thereby improving DSO performance. Furthermore, as seen in

Figure 9, DeepDSO achieves a lower root mean square error (RMSE) in the backward modality. This is considerably different from the original DSO, where system performance diminished in backward runs.

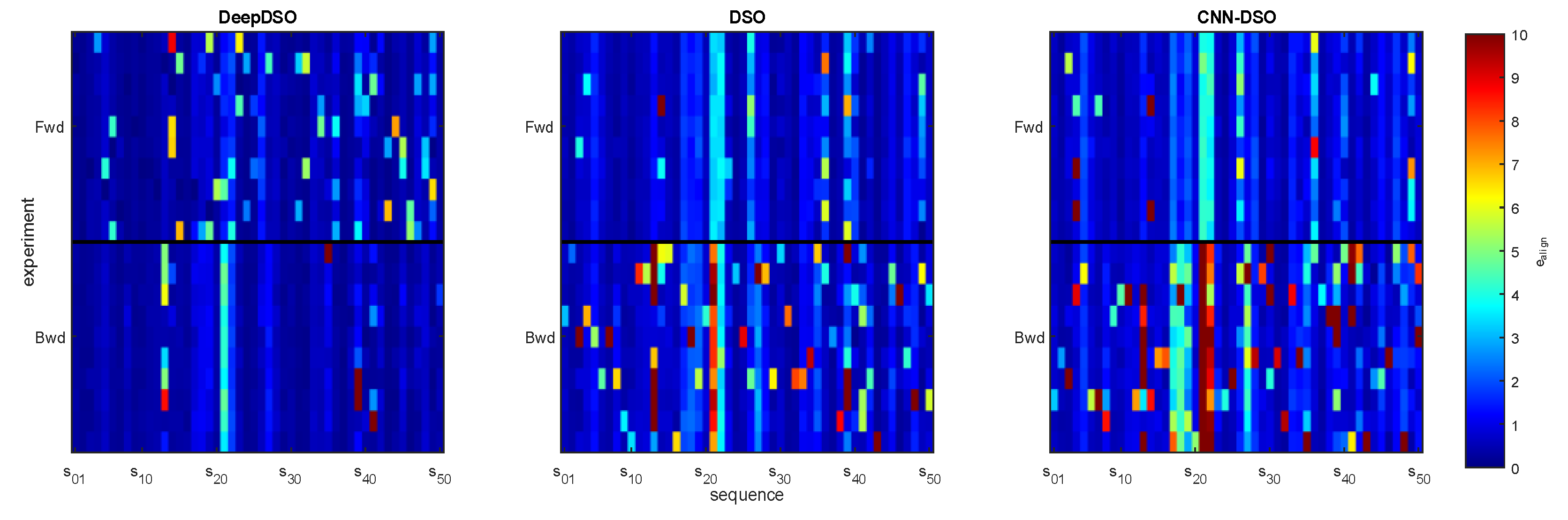

Figure 10 depicts the total alignment error measured for each system run on the 50 sequences of the TUM-Mono benchmark in both forward and backward directions to facilitate visualization of each system's performance.

As

Figure 10 shows, the DeepDSO method had the best performance of the three evaluated methods across the entire dataset. Although DeepDSO produced more errors when running forward (yellow, orange, and green pixels), it exhibited a considerable reduction in the frequency of backward errors, suggesting a more stable and reliable performance compared to DSO. DSO performs well forward but presents many backward failure cases, especially in sequences 13, 21, and 22. DeepDSO's performance is clearly better in these sequences but still presents minor issues in sequence 21. Conversely, CNN-DSO performed the worst, with many failure cases, particularly for backward runs. It failed for sequences 21 and 22.

For the sake of completeness, we performed a full statistical analysis of the results gathered by running the TUM-Mono benchmark on each algorithm, as proposed in [

42]. We started the statistical analysis by collecting all the error metric information in a database. This database included the following dependent variables: translation error (

), rotation error (

), scale error (

), start-segment alignment error (

), end-segment alignment error (

), and translational RMSE (

). We considered the method and the forward and backward modalities as categorical variables. Next, we used Mahalanobis distances as a data-cleaning technique to remove outliers. A cut-off score of 22.45774 was set based on the chi-squared distribution for a 99.999% confidence interval. This allowed us to detect and remove 94 outlier observations, leaving a database of 2,906 observations. Then, we tested the normality and homogeneity assumptions for each dependent variable using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene's tests. As an example, running the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for translation error yielded p-values of

for DeepDSO, DSO, and CNN-DSO, which make up the sample. Thus, the normality assumption was rejected. We also obtained a p-value of

in the Levene test and rejected the homogeneity assumption. Similar results were found when evaluating the other dependent variables. Therefore, it was concluded that the sample was nonparametric. Thus, the Kruskal–Wallis test was selected as the general test, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was selected as the post hoc test to determine whether the observed differences in the evaluation were significant.

Figure 11 and

Table 3 present the results obtained by applying statistical analyses to each dependent variable.

.

As can be seen in

Figure 11 and

Table 3, all Kruskal-Wallis comparisons reached the significance level. Thus, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed for each dependent variable to determine which paired comparisons were significant. DeepDSO significantly outperformed DSO and CNN-DSO in the translation error metric, achieving an average reduction of 0.32211 in translation error compared to its classic predecessor, while DSO significantly outperformed CNN-DSO. For the accumulated rotation error metric, DeepDSO significantly outperformed the DSO and CNN-DSO methods, achieving an average error reduction of 0.2519316 compared to the classic version. Again DSO significantly outperformed the CNN-DSO method in the rotation error metric. DeepDSO also outperformed DSO and CNN-DSO significantly in the scale error metric, achieving an error reduction of 0.37644 compared to DSO. Meanwhile, CNN-DSO significantly outperformed DSO in this metric. Regarding the start-segment alignment error metric, DeepDSO significantly outperformed DSO and CNN-DSO, achieving an error reduction of 0.002317049 compared to its classic version, while DSO performed significantly better than CNN-DSO. As expected,

Figure 5's behavior was confirmed for the end-segment alignment error metric: DeepDSO significantly outperformed DSO and CNN-DSO with an error reduction of 0.002048155, and DSO again outperformed CNN-DSO. Finally, for the RMSE metric, which considers all the aforementioned rotation, translation, and scale effects for both the start and end segments, DeepDSO significantly outperformed DSO and CNN-DSO, achieving an RMSE reduction of 0.1335233 and 0.14514478 compared to DSO and CNN-DSO, respectively. It should be noted that DSO achieved a slightly lower RMSE average score than CNN-DSO, though the difference was not significant.

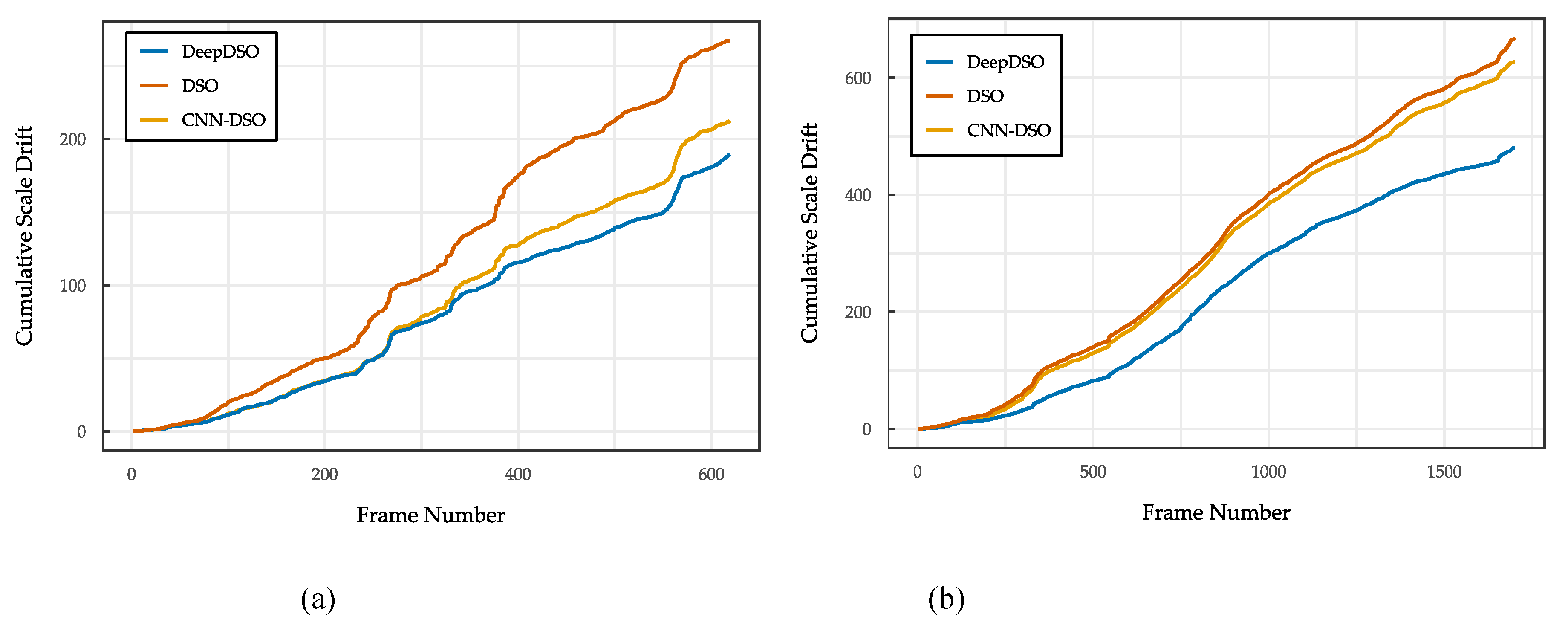

Finally, a temporal analysis of frame-wise scale error was conducted for sequences 02 and 29 of the TUM-Mono benchmark. The frame-wise scale factor was computed by comparing incremental displacements between consecutive frames in the estimated trajectory with the ground truth, according to the methodology proposed by [

87]. Then, the cumulative scale drift was calculated as the sum of the frame-wise errors across the trajectory. This provides insight into long-term stability without loop closure constraints. This method of evaluating scale drift dynamics was suggested by [

88].

Figure 12 shows the temporal evolution of the cumulative scale drift for DeepDSO, DSO, and CNN-DSO across both sequences. The results showed that DeepDSO had substantially lower cumulative drift than DSO and CNN-DSO throughout both trajectories. The final accumulated errors were X and Y for sequences 02 and 29 of the TUM-Mono dataset, respectively. DeepDSO notably exhibited stable scale estimation beyond frame 500, where traditional methods diverged. This sustained stability without loop closure demonstrates that the depth estimation module provides continuous scale correction throughout optimization, effectively mitigating the accumulation of prediction errors inherent to purely geometric approaches [

89].

4. Discussion

The TUM-Mono benchmark results, ratified by statistical analysis, demonstrated that integrating the NeW CRFs SIDE-NN module into the DSO framework significantly improved performance across all evaluated metrics: translation, rotation, scale, alignment, and RMSE. This confirmed that neuronal depth estimation modules substantially enhanced classic VO and SLAM systems for monocular applications. The experimental evidence revealed that these improvements stemmed from two synergistic mechanisms operating simultaneously. First, accurate depth initialization accelerated convergence during the windowed photometric optimization process—DSO's direct analogue to traditional bundle adjustment. The substantially lower start-segment alignment errors achieved by DeepDSO (0.001659 versus 0.003976 for DSO) indicated that NN depth priors constrained the search space to geometrically plausible regions, enabling faster convergence to better local optima during bootstrapping. Second, geometric constraints filtered erroneous correspondences before they contaminated the optimization window, substantially reducing outlier propagation. This mechanism was confirmed through comparative analysis: CNN-DSO, despite incorporating MonoDepth depth priors, produced reconstructions with considerable outlier contamination (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) and higher end-segment alignment errors (0.006651), whereas DeepDSO achieved 0.002171 through proper epipolar constraint integration with the more accurate NeW CRFs network. The motion bias analysis (

Figure 9) further demonstrated enhanced system stability, with DeepDSO maintaining consistent performance across forward and backward trajectory execution. These complementary mechanisms—accelerated optimization convergence and geometric outlier filtering—jointly explained the observed performance gains.

The proposed architecture employed a unidirectional design in which the SIDE-NN provided depth priors without receiving feedback from the DSO's optimization results. This open-loop formulation was deliberate. Closed-loop systems that require online CNN fine-tuning would introduce prohibitive computational overhead. For example, gradient backpropagation adds

per keyframe, whereas the current inference time is

. Closed-loop systems would also introduce potential instabilities, where optimization failures could corrupt learned priors. Training the NeW CRFs with self-supervised photometric consistency and spatial smoothness losses [

66] ensured geometric coherence compatible with the DSO's multi-view optimization objectives. The statistical significance of the performance improvements (

Table 3,

) validated the effective utilization of priors without requiring bidirectional coupling. Previous implementations [

46], inspired by [

41], addressed similar integration challenges but proved ineffective. CNN-DSO was significantly outperformed by original DSO in rotation, translation, and alignment errors, only achieving marginal improvements in scale recovery. This demonstrated that incorporating depth priors without proper integration allowed noisy data inclusion, ultimately degrading system performance due to MonoDepth's limited accuracy on TUM-Mono sequences and inadequate epipolar constraint implementation. Conversely, DeepDSO's superior scale error performance confirmed that the SIDE-NN module effectively contributed to properly scaled reconstructions. Since DSO's sparse-direct formulation tracks and manages every point and keyframe based on depth information, improved initialization directly enhanced both tracking and mapping capabilities, as evidenced by significant reductions in translation and rotation errors.

It is worth mentioning that a crucial component that enabled the successful implementation of the SIDE-NN module in the DSO algorithm was the CRF-based depth estimation approach. Adopting the NeW CRFs architecture instead of traditional fully-connected CRFs offered significant computational advantages for real-time depth estimation. As demonstrated in [

66], segmenting the input into non-overlapping windows and computing fully-connected CRFs within each window rather than across the entire image reduces the computational complexity from

to

, where

represents the total number of patches and

denotes the window size. The reduced computational burden enables integrating CRF optimization into the visual odometry pipeline without compromising real-time performance requirements while maintaining geometric constraints that pure regression-based depth networks lack.

This investigation focused on handheld monocular sequences acquired while pedestrians moved along closed-loop trajectories. The TUM-Mono benchmark provided a comprehensive evaluation framework for these sequences. However, extending this approach to substantially different domains, such as autonomous driving (KITTI benchmark) or UAV exploration, was beyond the scope of this study and represents a direction for future work. As with all purely monocular methods, scale ambiguity was an inherent limitation. Although the SIDE-NN integration mitigated this issue by providing depth priors, complete elimination was unattainable because performance depended on depth estimation accuracy. Advances in SIDE architectures would directly benefit visual odometry systems. Additionally, pure visual methods have well-known challenges with illumination variations, occlusions, and low-texture surfaces. Deep learning techniques for object detection and semantic segmentation could address these issues. Finally, considerable computational requirements complicated deployment on resource-constrained embedded devices, with the transformer-based NeW CRFs module contributing substantially to these demands through its multi-head attention mechanisms and window-based fully-connected CRF operations. Despite the demonstrated improvements, convergence issues inherent to the direct sparse DSO framework remained susceptible to occurrence, albeit at reduced frequencies. These included photometric error optimization convergence failures in textureless regions, depth estimation convergence difficulties under rapid motion patterns, pose estimation convergence challenges when incorporating distant keyframes, and the absence of loop closure capabilities that could lead to trajectory drift accumulation. Drift was particularly expected to occur during extended trajectory sequences, rapid motion transitions, prolonged exposure to textureless environments, and scenarios with frequent occlusions or significant illumination variations. While the NeW CRFs epipolar line constraints effectively reduced outlier inclusion and scale-related errors, the fundamental algorithmic characteristics of sparse direct methods preserved these convergence vulnerabilities. Comprehensive analysis of these convergence behaviors and robust mitigation strategies constitute essential directions for future investigations. Future research could explore lightweight closed-loop architectures enabling bidirectional information flow through adaptive mechanisms such as confidence-weighted prior integration or test-time optimization updates modulated by photometric convergence indicators. Such approaches could potentially enhance performance by leveraging geometric feedback while maintaining real-time capability, though careful analysis of coupling dynamics would be required to preserve system robustness.

Although NeW CRFs and MonoDepth were primarily employed, alternative depth estimation methods were evaluated during the 2023 development phase. At that time, DepthFormer [

90] and PixelFormer [

91] represented state-of-the-art, open-access SIDE architectures. However, these methods exhibited prohibitively long inference times, averaging 5.27 seconds per image, rendering them impractical for real-time operation. In contrast, NeW CRFs and MonoDepth achieved inference times below one second, reaching up to 10 frames per second. Consequently, only these two architectures were incorporated into this comparative analysis. While newer SIDE models have since emerged, their evaluation and integration into the DeepDSO framework remain subjects for future work.

Figure 13 presents depth inference examples using DepthFormer, PixelFormer, and NeW CRFs.

Figure 13.

Examples of depth inferences obtained using different SIDE-NNs: (a) DepthFormer, (b) PixelFormer, and (c) NeW CRFs.

Figure 13.

Examples of depth inferences obtained using different SIDE-NNs: (a) DepthFormer, (b) PixelFormer, and (c) NeW CRFs.

Figure 14.

3D map of the administrative building of Carchi State Polytechnic University captured with a standard smartphone camera (Xiaomi Redmi Note 10 Pro), without photometric calibration. As can be seen, DeepDSO can obtain 3D reconstructions and trajectories with non-specialized computer vision cameras without requiring exhaustive photometric calibration.

Figure 14.

3D map of the administrative building of Carchi State Polytechnic University captured with a standard smartphone camera (Xiaomi Redmi Note 10 Pro), without photometric calibration. As can be seen, DeepDSO can obtain 3D reconstructions and trajectories with non-specialized computer vision cameras without requiring exhaustive photometric calibration.

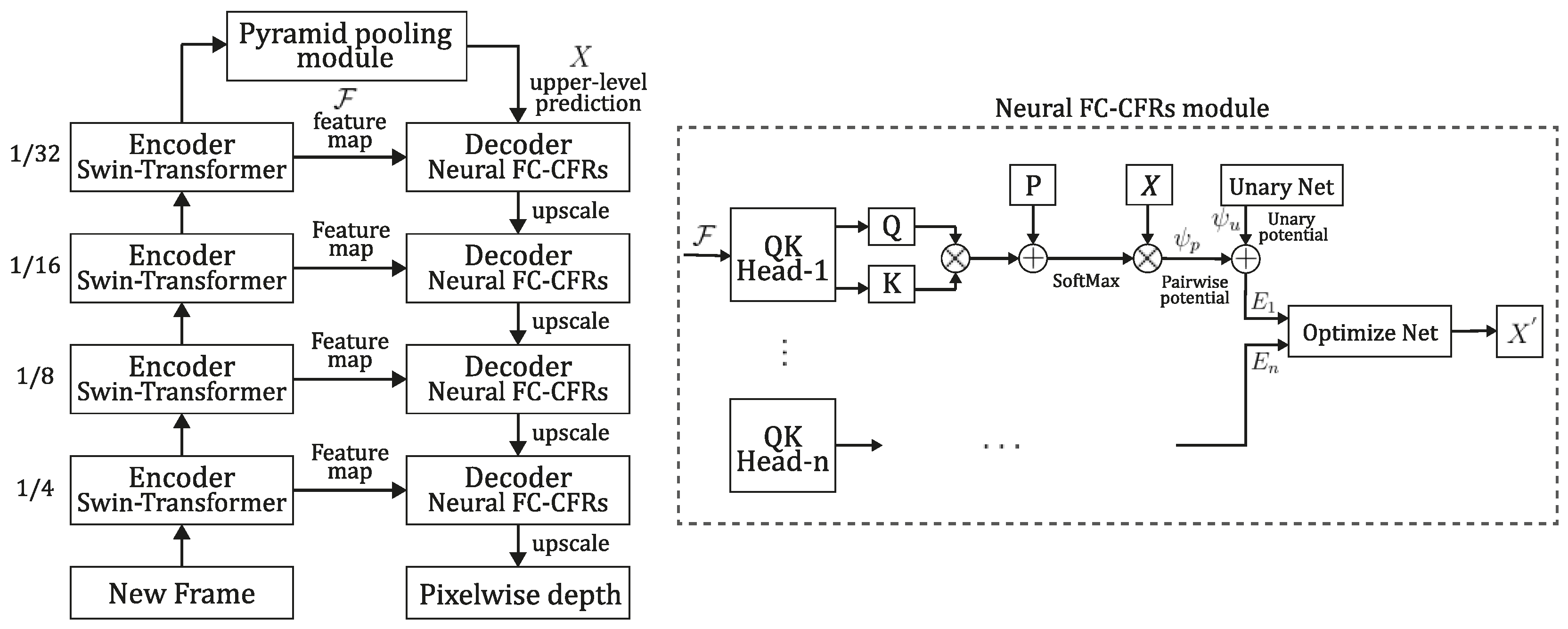

Figure 1.

Diagram of the NeW CRFs' bottom-up-top-down NN architecture and its FC-CRFs module.

represents the encoder’s output feature map;

represents the upper-level prediction; and

and

represent the unary and pairwise potentials, respectively. The dashed lines show the decoder's FC-CRFs module, which builds a multi-head energy function from the upper-level predictions and the feature map to improve the prediction. Inspired by the article of [

66].

Figure 1.

Diagram of the NeW CRFs' bottom-up-top-down NN architecture and its FC-CRFs module.

represents the encoder’s output feature map;

represents the upper-level prediction; and

and

represent the unary and pairwise potentials, respectively. The dashed lines show the decoder's FC-CRFs module, which builds a multi-head energy function from the upper-level predictions and the feature map to improve the prediction. Inspired by the article of [

66].

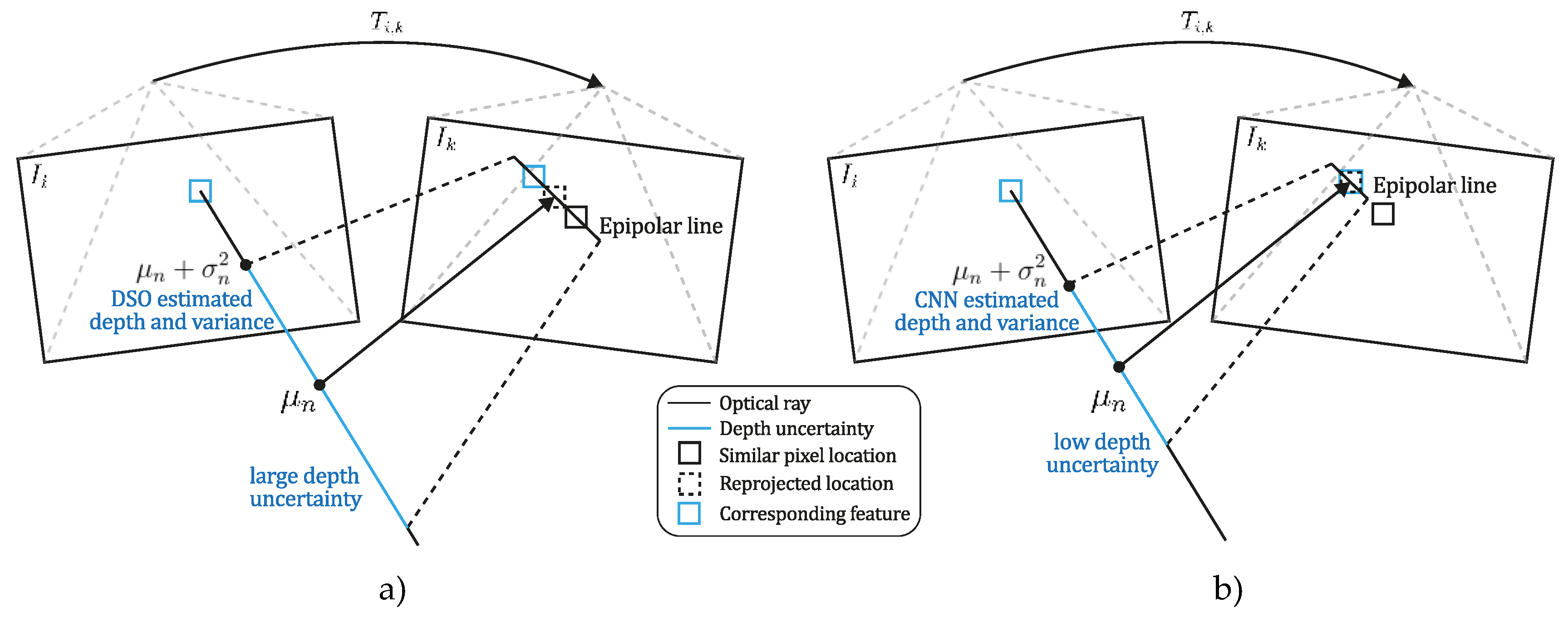

Figure 2.

Map point initialization strategy. The DSO searching interval along the epipolar line is improved by introducing prior information as depth and variance estimated using the SIDE-NN module. Figure (a) shows the DSO search interval without incorporating depth prior information. As shown in (b), the epipolar search interval in the next frame is reduced, enabling each point to converge to its scaled true depth while excluding similar points from the search interval.

Figure 2.

Map point initialization strategy. The DSO searching interval along the epipolar line is improved by introducing prior information as depth and variance estimated using the SIDE-NN module. Figure (a) shows the DSO search interval without incorporating depth prior information. As shown in (b), the epipolar search interval in the next frame is reduced, enabling each point to converge to its scaled true depth while excluding similar points from the search interval.

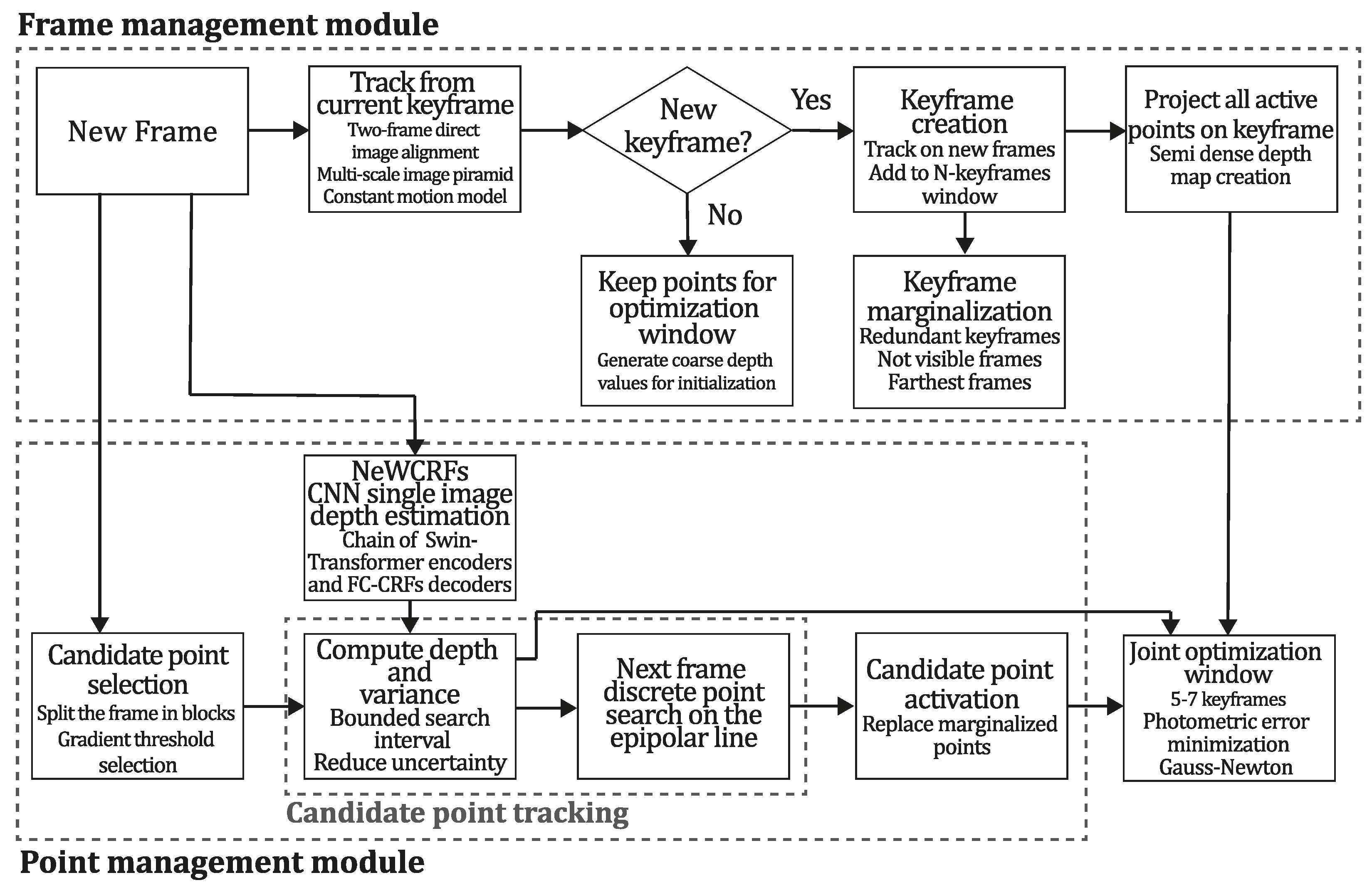

Figure 3.

Diagram of DeepDSO algorithm. Integrating the NeW CRFs SIDE-NN module in the DSO method.

Figure 3.

Diagram of DeepDSO algorithm. Integrating the NeW CRFs SIDE-NN module in the DSO method.

Figure 4.

Depth maps obtained with the DeepDSO method. Examples were obtained running the algorithm on the sequences a) 01, b) 20, c) 25, d) 29, e) 38, and f) 40 of the TUM-Mono dataset.

Figure 4.

Depth maps obtained with the DeepDSO method. Examples were obtained running the algorithm on the sequences a) 01, b) 20, c) 25, d) 29, e) 38, and f) 40 of the TUM-Mono dataset.

Figure 5.

Example reconstructions obtained using the evaluation algorithms. (a) represents the input image, and the geometry representations correspond to the (b) DSO, (c) CNN-DSO, and (d) DeepDSO methods. The top row shows indoor examples and the bottom row shows outdoor examples obtained using sequences 01 and 29 of the TUM-Mono dataset [

43].

Figure 5.

Example reconstructions obtained using the evaluation algorithms. (a) represents the input image, and the geometry representations correspond to the (b) DSO, (c) CNN-DSO, and (d) DeepDSO methods. The top row shows indoor examples and the bottom row shows outdoor examples obtained using sequences 01 and 29 of the TUM-Mono dataset [

43].

Figure 6.

Examples of the per-pixel depths recovered by the two SIDE modules that were tested. (a) shows the input image, (b) shows the output of MonoDepth, and (c) shows the output of the NeW CRFs. .

Figure 6.

Examples of the per-pixel depths recovered by the two SIDE modules that were tested. (a) shows the input image, (b) shows the output of MonoDepth, and (c) shows the output of the NeW CRFs. .

Figure 7.

Translation , rotation , and scale accumulated errors for the DeepDSO, DSO, and CNN-DSO algorithms evaluated algorithms.

Figure 7.

Translation , rotation , and scale accumulated errors for the DeepDSO, DSO, and CNN-DSO algorithms evaluated algorithms.

Figure 8.

Start- and end-segment alignment error, corresponding to the RMSE of the alignment error when compared with the start- and end-segment ground truth.

Figure 8.

Start- and end-segment alignment error, corresponding to the RMSE of the alignment error when compared with the start- and end-segment ground truth.

Figure 9.

Dataset motion bias for each method. They were evaluated by running all sequences forwards and backward, as well as their combination (bold).

Figure 9.

Dataset motion bias for each method. They were evaluated by running all sequences forwards and backward, as well as their combination (bold).

Figure 10.

Color-coded alignment error for each algorithm in the TUM-mono dataset.

Figure 10.

Color-coded alignment error for each algorithm in the TUM-mono dataset.

Figure 11.

Box plots, error bars, and Kruskal-Wallis comparisons for the medians of the cumulative errors collected after 1000 runs of each algorithm, (a) translation error, (b) rotation error, and (c) scale error, (d) only start-segment alignment error, (e) only end-segment alignment error, (f) RMSE for combined effect on start and end segments.

Figure 11.

Box plots, error bars, and Kruskal-Wallis comparisons for the medians of the cumulative errors collected after 1000 runs of each algorithm, (a) translation error, (b) rotation error, and (c) scale error, (d) only start-segment alignment error, (e) only end-segment alignment error, (f) RMSE for combined effect on start and end segments.

Figure 12.

Temporal evolution of cumulative scale drift on TUM-Mono sequences: (a) sequence 02 (650 frames) and (b) sequence 29 (1900 frames).

Figure 12.

Temporal evolution of cumulative scale drift on TUM-Mono sequences: (a) sequence 02 (650 frames) and (b) sequence 29 (1900 frames).

Table 1.

Sensitivity Analysis of Variance Coefficient in Depth Variance Initialization

Table 1.

Sensitivity Analysis of Variance Coefficient in Depth Variance Initialization

|

Coefficient ()

|

Translational RMSE† |

Std. Dev. |

Convergence Rate‡ |

| 2 |

0.4127 |

0.0856 |

73% |

| 3 |

0.3214 |

0.0523 |

87% |

| 4 |

0.2685 |

0.0347 |

94% |

| 5 |

0.2453 |

0.0218 |

98% |

| 6 |

0.2382 |

0.0163 |

100% |

| 7 |

0.2491 |

0.0197 |

100% |

| 8 |

0.2738 |

0.0284 |

100% |

| 9 |

0.3156 |

0.0412 |

100% |

| 10 |

0.3647 |

0.0569 |

100% |

Table 2.

Specifications of the hardware used during experimentation.

Table 2.

Specifications of the hardware used during experimentation.

| Component |

Specifications |

| CPU |

AMD Ryzen™ 7 3800X. 8 cores, 16 threads, 3.9 – 4.5 GHz. |

| GPU |

NVIDIA GEFORCE RTX 3060. Ampere architecture, 1.78 GHz, 3584 CUDA cores, 12 GB GDDR6X. Memory interface width 192-bit. 2nd generation Ray Tracing Cores and 3rd generation Tensor cores. |

| RAM |

16 GB, DDR 4, 3200 MHz. |

| ROM |

SSD NVME M.2 Western Digital 7300 MB/s |

| Power consumption |

750 W1

|

Table 3.

Medians and Kruskal-Wallis comparisons for each algorithm's translation, rotation, and scale errors.

Table 3.

Medians and Kruskal-Wallis comparisons for each algorithm's translation, rotation, and scale errors.

| Method |

Translation

error

|

Rotation

error

|

Scale

error

|

Start-segment

Align. error

|

End-segment

Align. error

|

RMSE |

| Kruskal-Wallis general test |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DeepDSO |

0.3250961a |

0.3625576a |

1.062872a |

0.001659008a |

0.002170299a |

0.06243667a |

| DSO |

0.6472075b

|

0.6144892b

|

1.100516b

|

0.003976057b

|

0.004218454b

|

0.19595997b

|

| CNN-DSO |

0.7978954c

|

0.9583970c

|

1.078830c

|

0.008847161c

|

0.006651353c

|

0.20758145b

|