Submitted:

09 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

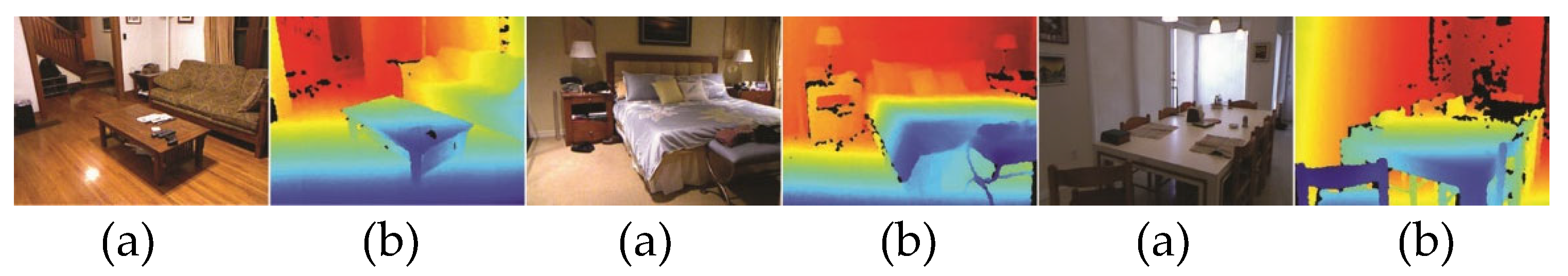

- We propose a human-robot interaction system for a monocular depth estimation auto-encoder network to effectively learn the complex process of transforming a color image into a depth image. Unlike previous approaches that relied on the concept of perceptual loss.

- -

- The proposed technique aims to learn the process of “generation” from the latent space rather than using a “classification” strategy to refine the estimated depth information.

- -

- In contrast to other techniques, the proposed method works reasonably accurately since the proposed network design does not use feature branches other than skip connections of residula blocks.

2. Related Work

3. Proposed Monocular Depth Estimation

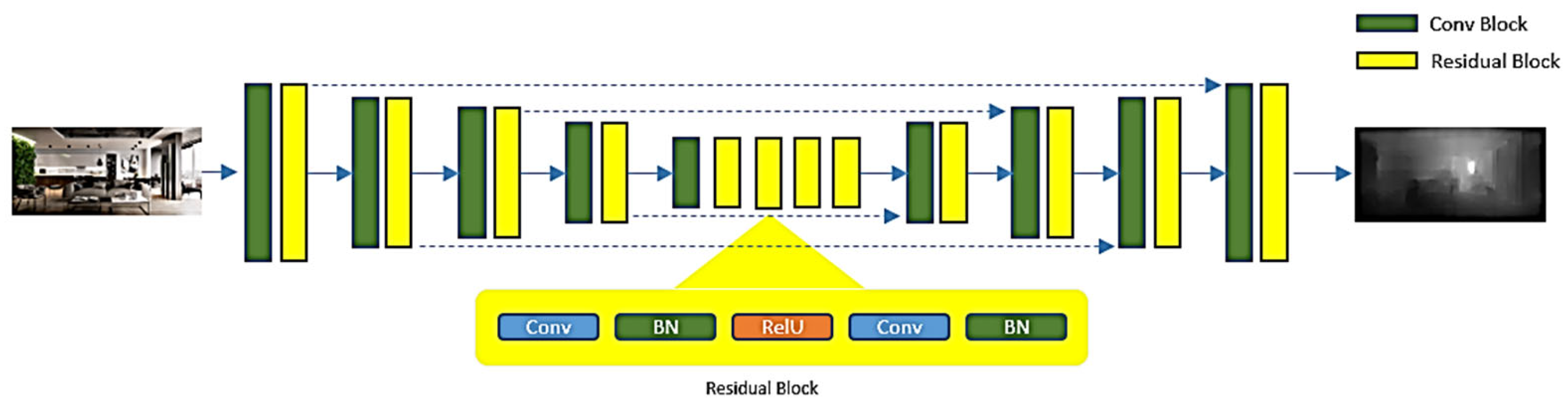

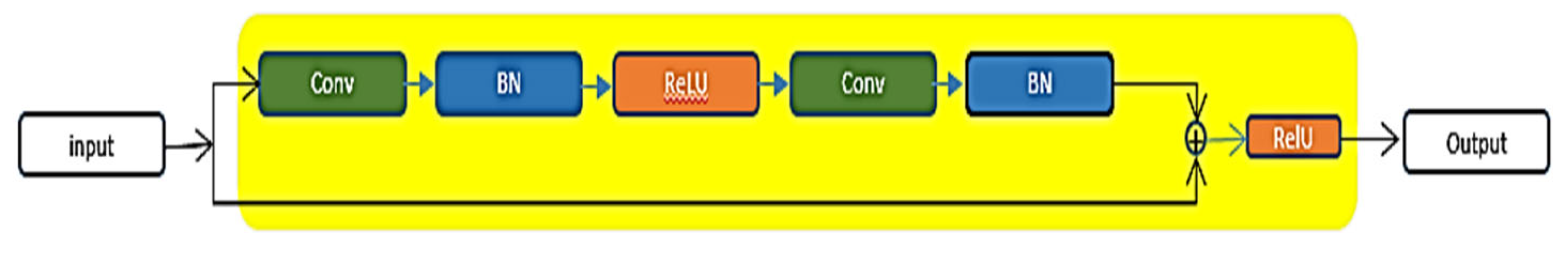

3.1. Depth Estimation Deep Learning Model

| Module | Layer type | Weight dimension | Stride |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder | Conv ResBlock Conv ResBlock Conv ResBlock Conv ResBlock Conv |

64x3x9x9 64 x 64 x 9 x 9 128 x 64 x 7 x 7 128 x 128 x 7 x 7 256 x 128 x 5 x 5 256 x 256 x 5 x 5 512 x 256 x 3 x 3 512 x 512 x 3 x 3 512 x 512 x 3 x 3 |

1 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 |

| ResNet | 6x ResBlock | 512 x 512 x 3 x 3 | 1 |

| Decoder | Upsampling Conv ResBlock Upsampling Conv ResBlock Upsampling Conv ResBlock Upsampling Conv ResBlock Conv |

- 512 x 512 x 3 x 3 512 x 512 x 3 x 3 - 256 x 512 x 3 x 3 256 x 256 x 5 x 5 - 256 x 128 x 5 x 5 128 x 128 x 7 x 7 - 128 x 64 x 7 x 7 64 x 64 x 9 x 9 64x3x9x9 |

- 1 1 - 1 1 - 1 1 - 1 1 1 |

3.2. Latent Loss Functions

3.3. Gradiant Loss

4. Experiment

4.1. NYU v2 Depth Dataset

4.2. Performance Evaluation

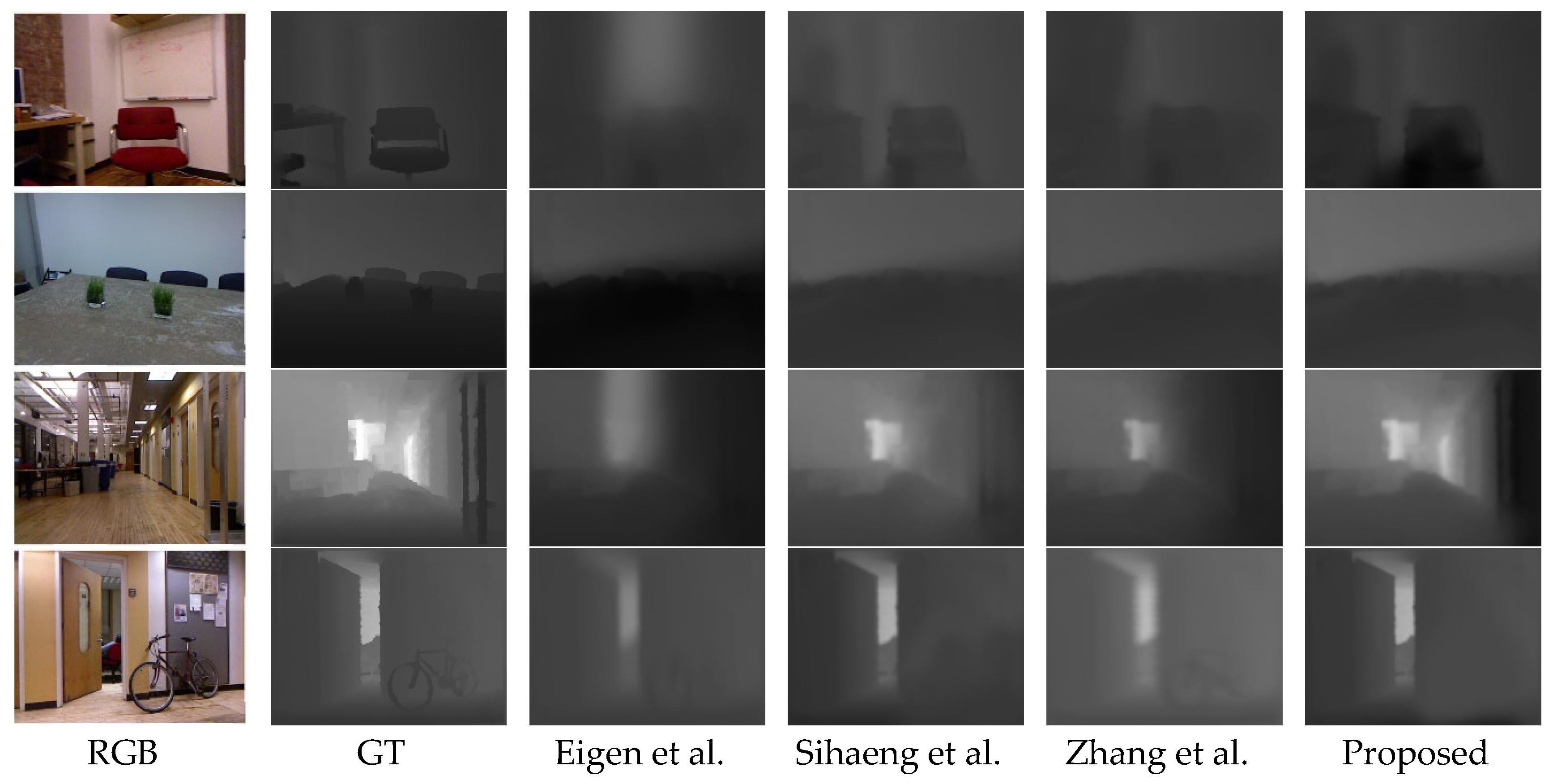

| Architectures | Eigen et al. | Sihaeng et al. | Zhang et al. | Proposed |

| RMSE | 0.907 | 0.454 | 0.590 | 0.416 |

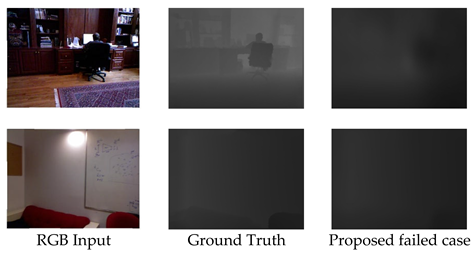

4.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M. Tightly Coupled 3D Lidar Inertial Odometry and Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); IEEE Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, May 20 2019; pp. 3144–3150. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Hang, K.; Song, H.; Kragic, D.; Wang, M.Y.; Stork, J.A. Reinforcement Learning in Topology-Based Representation for Human Body Movement with Whole Arm Manipulation. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); May 2019; pp. 2153–2160. [CrossRef]

- Scharstein, D.; Szeliski, R. A Taxonomy and Evaluation of Dense Two-Frame Stereo Correspondence Algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2002, 47, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenderink, J.J.; Doorn, A.J. van Affine Structure from Motion. JOSA A 1991, 8, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, S.M.; Curless, B.; Diebel, J.; Scharstein, D.; Szeliski, R. A Comparison and Evaluation of Multi-View Stereo Reconstruction Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’06); June 2006; Vol. 1, pp. 519–528. [CrossRef]

- Stefanoski, N.; Bal, C.; Lang, M.; Wang, O.; Smolic, A. Depth Estimation and Depth Enhancement by Diffusion of Depth Features. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing; September 2013; pp. 1247–1251. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Sun, M.; Ng, A.Y. Make3D: Learning 3D Scene Structure from a Single Still Image. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2009, 31, 824–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, J.; Wang, M.; Ishwar, P.; Wu, C.; Mukherjee, D. Learning-Based, Automatic 2D-to-3D Image and Video Conversion. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 3485–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, S.; Derek, H.; Pushmeet, K.; Rob, F. Indoor Segmentation and Support Inference from RGBD Images. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-J.; Lin, S.-K. A Performance Criterion for the Depth Estimation of a Robot Visual Control System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2001 ICRA. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.01CH37164); May 2001; Vol. 2, pp. 1201–1206 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Nicolas, G.; Sagues, C.; Guerrero, J.J.; Lopez-Nicolas, G.; Sagues, C.; Guerrero, J.J. Shortest Path Homography-Based Visual Control for Differential Drive Robots; IntechOpen, 2007; ISBN 978-3-902613-01-1.

- Sabnis, A.; Vachhani, L. Single Image Based Depth Estimation for Robotic Applications. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Recent Advances in Intelligent Computational Systems; September 2011; pp. 102–106. [CrossRef]

- Unsupervised Odometry and Depth Learning for Endoscopic Capsule Robots – ArXiv Vanity. Available online: https://www.arxiv-vanity.com/papers/1803.01047/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Jin, Y.; Lee, M. Enhancing Binocular Depth Estimation Based on Proactive Perception and Action Cyclic Learning for an Autonomous Developmental Robot. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Xu, W.; Guo, J.; Lam, H.-K.; Jia, G.; Hong, W.; Ren, H. Depth Estimation of Hard Inclusions in Soft Tissue by Autonomous Robotic Palpation Using Deep Recurrent Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yi, P.; Liu, R.; Dong, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Q. Human-Robot Interaction Method Combining Human Pose Estimation and Motion Intention Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 24th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD); May 2021; pp. 958–963. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Shen, F. Disparity Estimation Method of Electric Inspection Robot Based on Lightweight Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP); April 2021; pp. 929–932. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Ruan, X. CLIFFNet for Monocular Depth Estimation with Hierarchical Embedding Loss. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 316–331. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, N.; Shirai, Y.; Kuno, Y.; Miura, J. Hand Gesture Estimation and Model Refinement Using Monocular Camera-Ambiguity Limitation by Inequality Constraints. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Third IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition; April 1998; pp. 268–273. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Huang, J.; Qin, S. High Accurate Estimation of Relative Pose of Cooperative Space Targets Based on Measurement of Monocular Vision Imaging. Optik 2014, 125, 3127–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learning Latent Vector Spaces for Product Search | Proceedings of the 25th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2983323.2983702 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Kashyap, H.J.; Fowlkes, C.; Krichmar, J.L. Sparse Representations for Object and Ego-Motion Estimation in Dynamic Scenes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 2521–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reading, C.; Harakeh, A.; Chae, J.; Waslander, S.L. Categorical Depth Distribution Network for Monocular 3D Object Detection; IEEE Computer Society, June 1 2021; pp. 8551–8560.

- Pei, M. MSFNet:Multi-Scale Features Network for Monocular Depth Estimation 2021.

- Zhao, C.; Tang, Y.; Sun, Q. Unsupervised Monocular Depth Estimation in Highly Complex Environments 2022.

- Guo, S.; Rigall, E.; Ju, Y.; Dong, J. 3D Hand Pose Estimation From Monocular RGB With Feature Interaction Module. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 5293–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 694–711. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); June 2016; pp. 770–778.

- Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, X. Monocular Image Depth Estimation Using a Conditional Generative Adversarial Net. In Proceedings of the 2018 37th Chinese Control Conference (CCC); July 2018; pp. 9176–9180. [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, W.; Lin, L. Monocular Depth Estimation with Affinity, Vertical Pooling, and Label Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 232–247. [Google Scholar]

- Depth Map Prediction from a Single Image Using a Multi-Scale Deep Network | Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 2. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/2969033.2969091 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Patch-Wise Attention Network for Monocular Depth Estimation(AAAI 2020) - KAIST. Available online: https://ee.kaist.ac.kr/en/ai-in-signal/18520/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Delage, E.; Lee, H.; Ng, A.Y. A Dynamic Bayesian Network Model for Autonomous 3D Reconstruction from a Single Indoor Image. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’06); June 2006; Vol. 2, pp. 2418–2428. [CrossRef]

- Hoiem, D.; Efros, A.A.; Hebert, M. Geometric Context from a Single Image. In Proceedings of the Tenth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV’05) Volume 1; October 2005; Vol. 1, pp. 654-661 Vol. 1. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).