1. Introduction

Depth estimation is important in computer vision for robot control [

1], multi-view generation for 3D exhibition [

2,

3,

4], autonomous driving [

5] and hand-gesture recognition in mixed reality (MR) [

6] and so forth. In general, the depth estimations can be roughly catalogued into image-based and sensor-based approaches. Image-based approaches including stereo matching [

7] and monocular depth estimation [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] which purely exploit the RGB image resource to achieve the depth estimation task.

The monocular depth estimation networks can be cataloged into supervised [

8], unsupervised [

13] and semi-supervised [

15,

16] approaches. The training resource of su

pervised monocular depth estimation networks could primarily come from the infrared, LiDAR, radar, and ultrasonic sensors [

17]. Thus, the primary depths are manually corrected according to the accurate depth distances to obtain the ground truth (GT) depth maps. However, in most cases, labeling and annotations of GT depths cannot be easily available. Thus, the unsupervised networks adopt paired stereo color images captured by dual cameras to indirectly infer the GT depth map for each other. The convenience of developing the unsupervised network is that the GT depth maps of TOF camera is not needed at all. The depth map predicted from a color view is applied to render the virtual RGB image of another view using depth-image-based rendering (DIBR) [

3]. Thus, the prediction of depth loss can be transferred to the RGB domain that the training loss is only associated with the varied RGB image differences. The semi-supervised networks are conceptually similar to the unsupervised ones that they can be divided into two classes. The first class utilizes dual-view RGB images combined with semantic segmentation information and 3D-reconstructed surface normal information to achieve multi-functional networks [

15]. The embeddings of normal, segmentation and depth can be informatively harmonized to enhance the accuracy of depth estimation. The second class integrates the dual-view RGB images and low-resolution depth maps [

15] that their loss functions are similar to that of unsupervised approaches where the calibrations are partially required in supervised processing.

The users would not like to adopt the parallelized RGB cameras for obtaining the parallax in depth estimation, when the persistence of on-line calibration is troublesome for the use of moving stereo cameras with inevitable vibrations. Thus, the monocular depth estimation network appears common in use for cost-effective depth estimation. Further, the monocular depth estimation with the aid of LiDAR sensor [

17] or time-of-flight (ToF) sensor [

18] is preferred for predicting the real-world distances. The ToF sensors of LED light source are cheap but supply the low accuracies and the shorter range of sensed depths relative to the LiDAR sensors. The MR glasses in mobile features are often with computation-constrained resource, making the complex state-of-the-art depth methods be hardly designed in it. Hence, the low power-consumption ToF depth sensor is the first choice for the installation in smart MR glasses. Although, the low-cost ToF depth sensor can only offer spare depths, in principle, the high effective compensation of spare depth map and RGB image shall capably figure out the high-precision depth map with partial practical distances. To obtain precise high dimension depths for the MR glasses, in this paper, we presented lightweight depth estimation networks that the main contributions are threefold.

The proposed structure of our network targeted at the utilization of low-cost MR glasses can attain the optimal fusion of the sparse depth map and RGB image to achieve the accurate high-precision dense depth map.

A novel adaptive dynamic range bins estimator is proposed for promptly estimating the depth distribution of the captured scene, making the finally resulted depth maps be considerably appropriate for specified employments.

The proposed networks with two decoding variants have been successfully implemented on the Jorjin MR glasses [

19] for the hand-gesture MR and the augmented reality (AR) applications.

2. Related Work

Related to this study, the technologies of monocular depth estimation, adaptive bins estimation and depth completion should be briefly reviewed in the following three subsections.

2.1. Depth Estimation

Monocular depth estimation tackles the problem of estimating scene depth via a single RGB image. Estimating depth/distance from a single RGB image is an ill-pose problem physically in the viewpoint of computer vision. However, numerous deep learning approaches have been developed to address this challenge in terms of the maximum probability. Most of these methods are based on the autoencoder architecture. The encoder extracts the embedding features from RGB images and then the decoder with learnable upsampling layers to progressively recover the depth predictions. Depth estimation tasks can be divided into two major categories: unsupervised and supervised approaches. Supervised learning approaches [

8,

9,

10,

11] use ground truth depth to perform per-pixel regression of dense depth values and unsupervised methods [

13,

14] do not need the GT depth data for the training process. In general, the pure supervised learning networks need the precise high-dimensional GT depth maps for deepening the learning and the pure unsupervised learning demands the sufficient RGB stereo image datasets. Thus, they appear unsuitable for estimating the high-precision real-world depths under the constraints of only using the low-power equipment and anticipating the dense practical perspective distances. Hence, we herein design the lightweight depth predictive networks with variant decoders under the conditions that a color camera and a ToF depth-sparse sensor are only available.

2.2. Depth Completion

With sparse samples obtained from LiDAR or ToF sensors, depth completion [

17,

18] can reconstruct the dense depth by utilizing high resolution RGB images and sparse depth measures. Ma et al. develop a CNN-based depth network using RGB-D raw data to achieve the accurate and reliable LiDAR super-resolution [

20]. This work can identify that, by the aid of only few LiDAR depths, the high-dimensional depth map estimation can be improved. The autoencoder-based network can likely recover the dense depth map from the sparse depth samples by direct regression routine [

21]. However, the generated depth maps of these approaches often have blurry depth boundaries. To solve this problem, Cheng et al. [

22] proposed an architecture termed convolutional spatial propagation network (CSPN) to effectively mitigate this blurring phenomenon in depth completion task. This architectural concept is inspired by the spatial propagation network (SPN) [

23] that SPN can learn the affinities for local neighborhood of pixels and propagate the information of affinities iteratively over spatial dimensions. As a result, the blurry depth maps and the coarse-profile segmentation masks can be sharpened and refined.

2.3. Adaptive Bins Estimation

Early CNN-based depth estimation approaches can be viewed as a per-pixel regression task. Some approaches employ the autoencoder to extract features for making the extensive per-pixel regression to construct the depth maps of rational naturalness. Compared to CNN-based depth methods based on one-step regression without the alignment of depth anchors, AdaBins can provide the individual alignments of estimated depth centers for different real-word perspective ranges. The common sense of AdaBins is to split depth range into several subintervals that the division of bins is estimated per-image adaptively. Thus, the probabilities of per-pixel depth falling into these dynamic bins can be measured. Finally, the depth of each pixel can be predicted by linear combination of each bin center and their corresponding probabilities. Bhat et al. [

12] show that monocular depth estimation can be treated as a pixel-based classification task by utilizing an AdaBins module. The AdaBins modules can be useful appropriated tools to offer the high-precision depth estimation for remote sensing and aerial images [

24,

25]. There are several AdaBins structures suggested to further promote the depth estimation performances with semantic, mask transformer, multi-scale and knowledge distillation techniques [

25,

26,

27,

28] to alleviate the computation. Hence, the AdaBins module can support the high practicality of monocular depth estimation network in real-distance detection tasks.

3. Proposed Method

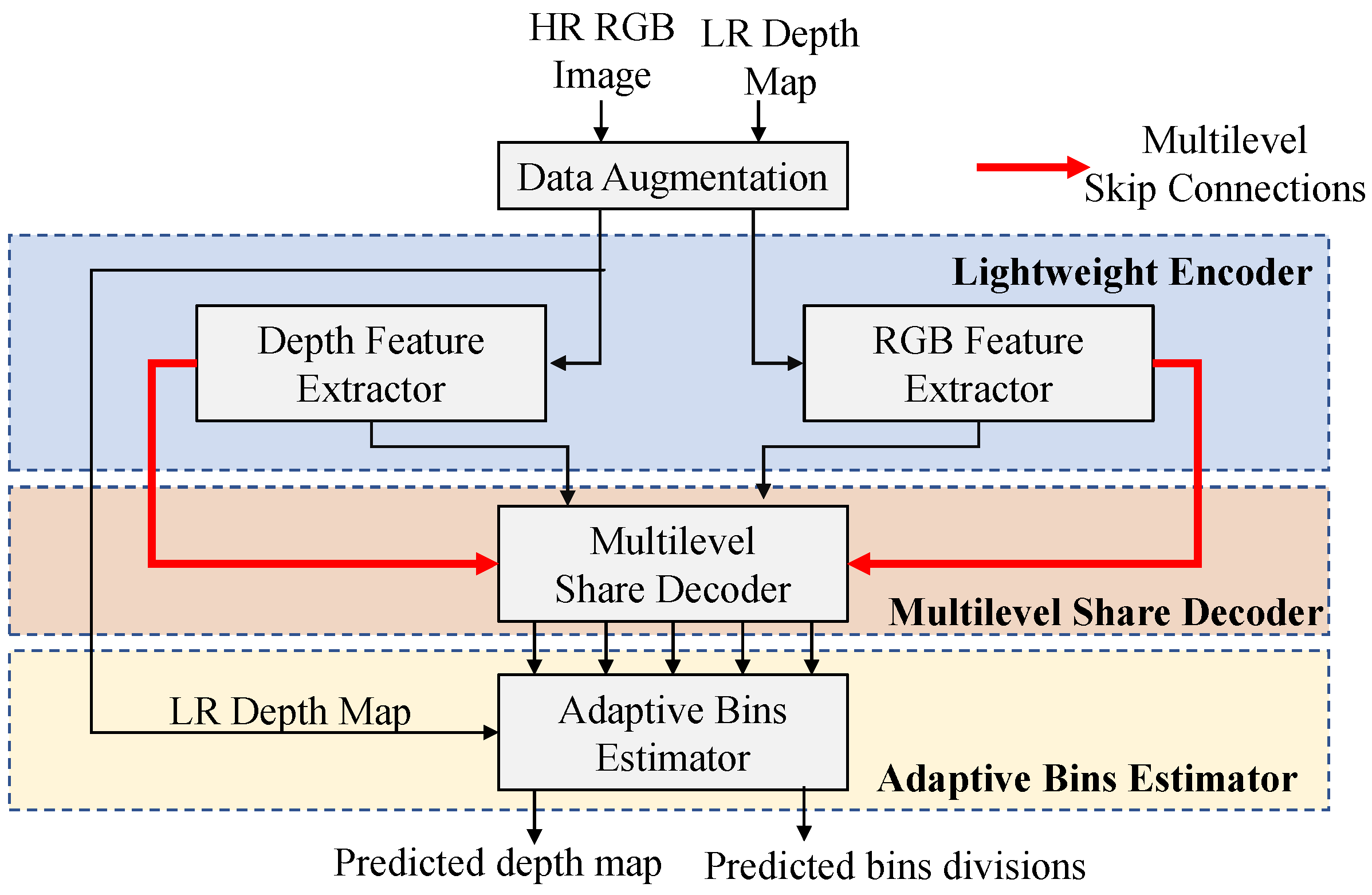

In the proposed depth estimation network, the inputs captured by MR glasses are a high-resolution (HR) RGB image and a low-resolution (LR) depth map. The HR images and their corresponding LR depth maps are fed into the feature extractors to extract their high and low level features separately. The extracted features then pass through a share multilevel share decoder to fuse all the level features of image and depth together to reconstruct the dense depth features gradually, as

Figure 1 shown. The features decoded from low level to high level are fed into an adaptive bins estimator which performs global analysis of depth features. The adaptive bins estimator predicts the bins divisions, which can be treated as the predictive depth distributions of current scenes. Finally, the output dense depth map is calculated by the linear combination of bins divisions and the corresponding probabilities.

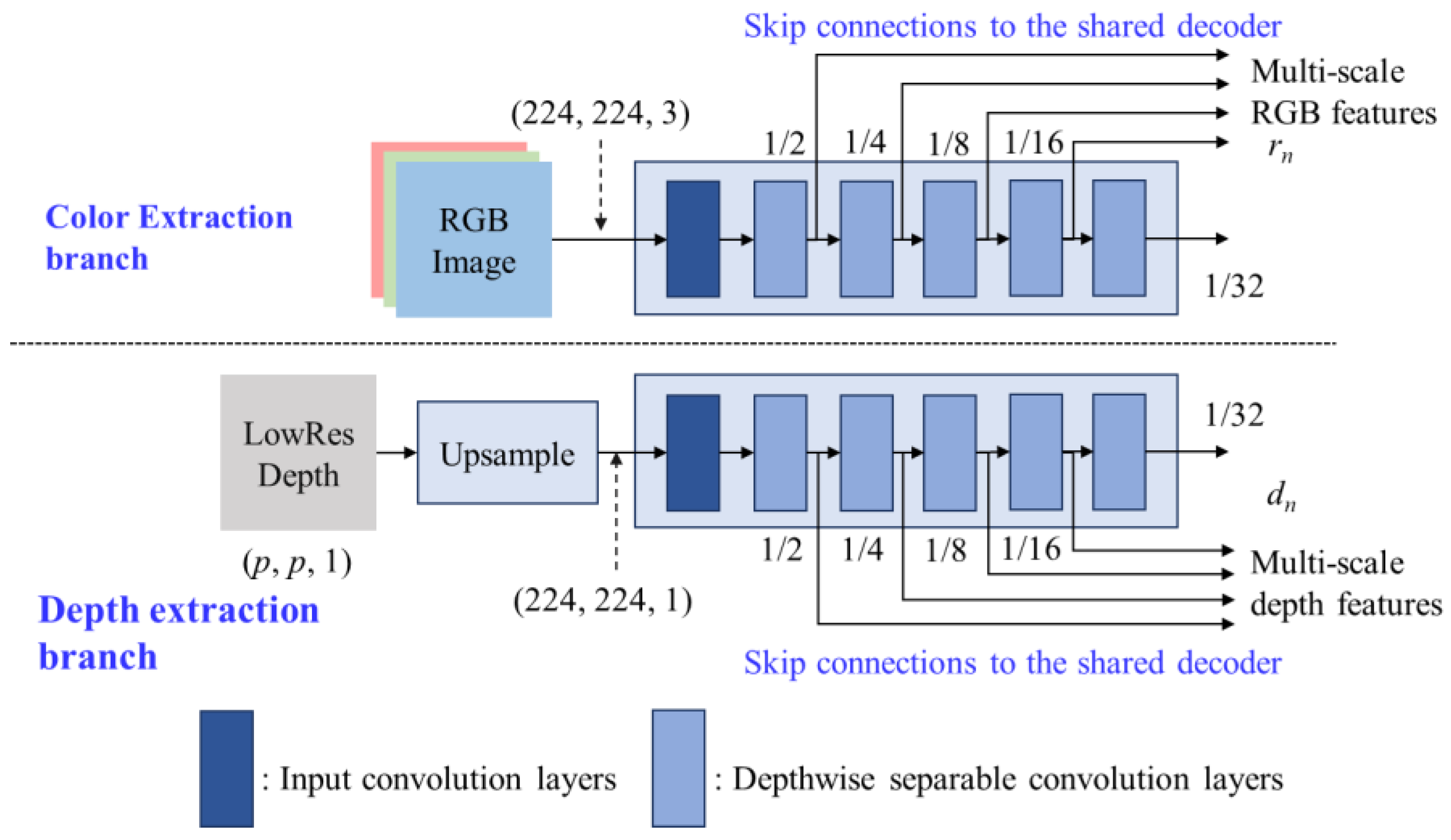

3.1. Lightweight Encoder

The proposed encoder is designed as a lightweight dual-path feature extractor where one path is called the RGB extraction branch and another is called the depth extraction branch, as shown in

Figure 2. The inputs of proposed encoder are the RGB image with size 224×224×3 and the LR depth map with the size of

p×

p×1 that

p = 8 needs to be set for the Jorjin J7EF Plus AR glasses [

19]. The HR RGB image and LR depth map are fed into color extraction branch and depth extraction branch, respectively, that the LR depth maps are bi-linearly interpolated to the same spatial dimension as the RGB images before feed into depth extraction branch.

To let the proposed model be suited for low-cost MR glasses, the primary consideration of designing modules should be high efficiency in computation. Inspired by FastDepth [

10], we adopt MobileNet [

30] with depthwise separable convolution layers as our feature extractors since they provide extreme computational efficiency. Then, we reduce the convolution layers on the original MobileNet layers to further achieve higher model throughput. The reduced encoder contains 6 depthwise separable convolution layers which can be regarded as a simplified MobileNet module termed MobileNet-s. The multilevel outputs of MobileNet-s are fed forward to the multilevel decoder through the multilevel skip connections to generate the fused multilevel decoding features.

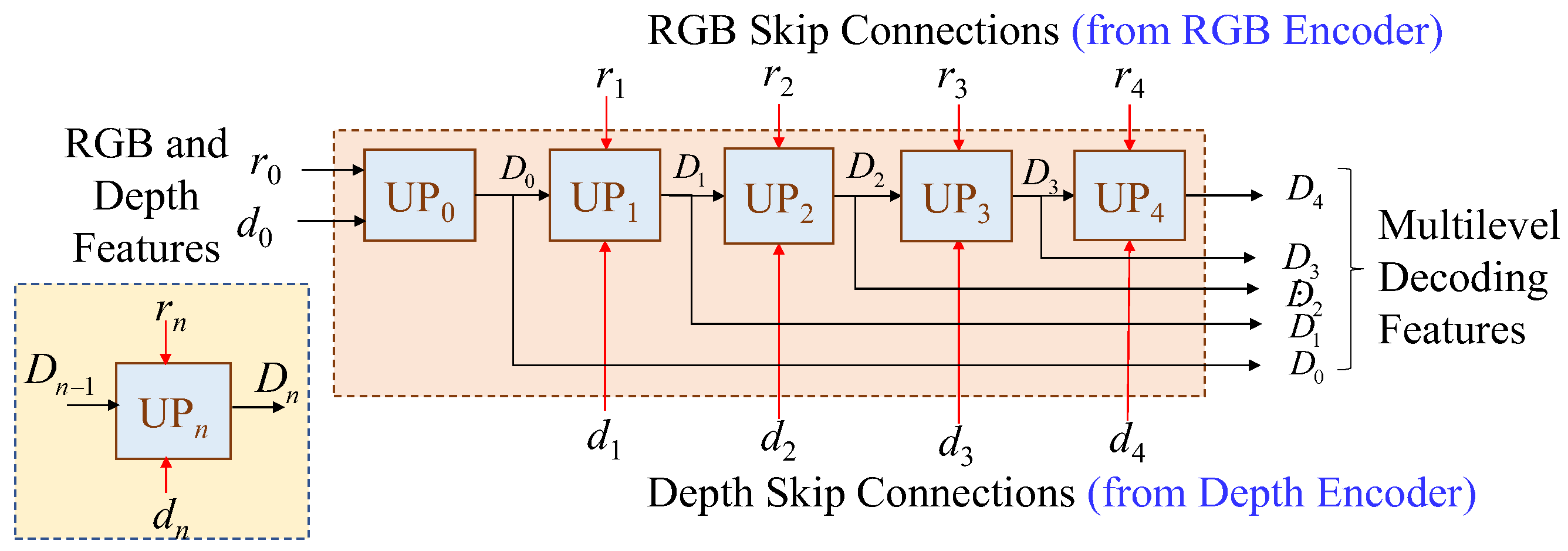

3.2. Multilevel Shared-Decoder

The proposed multilevel shared-decoder can successfully fuse the RGB and depth features together, shown as

Figure 3, where the multilevel shared-decoder, which consists of five cascading upsample blocks, i.e., UP

0, UP

1, UP

2, UP

3, and UP

4. For the nth upsample block (UP

n), two nth level features, r

n and d

n, coming from RGB and depth branches, respectively, are applied layer by layer to progressively reconstruct multilevel decoding features, i.e., D

0, D

1, D

2, D

3, and D

4, which will be further processed by the adaptive bins estimator for depth estimation.

In the study, two types of upsampling blocks are designed to cover different application scenarios, which are SimpleUp for high-efficiency and UpCSPN-k for high-accuracy applications.

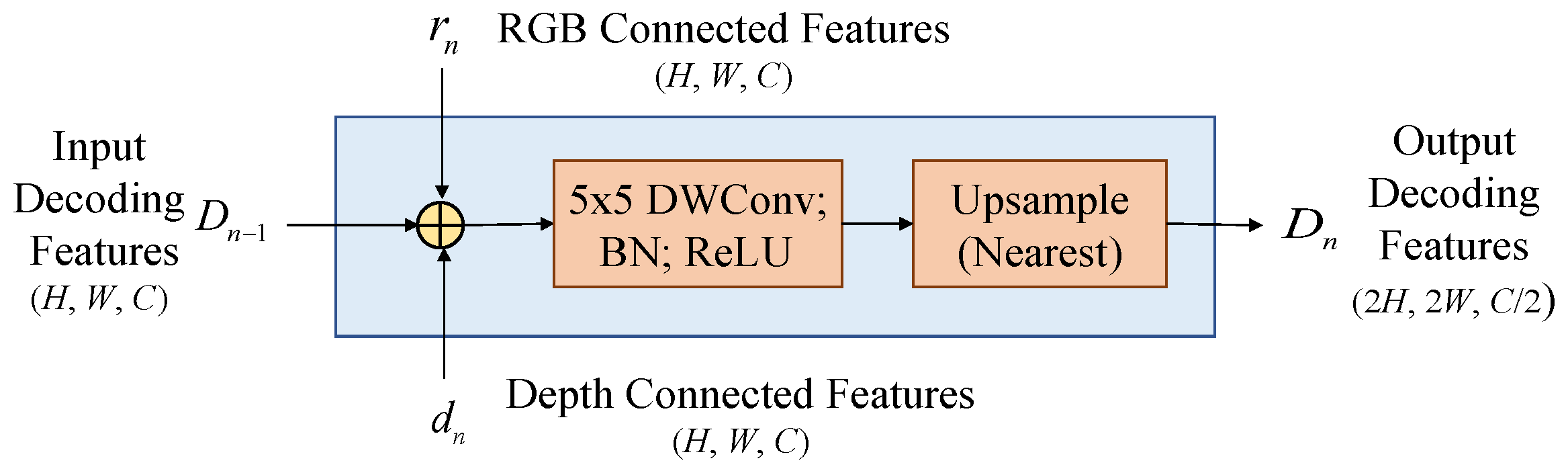

3.2.1. Upsampling by SimpleUp

For the applications of mobiles, the design of upsampling block must be very lightweight to fit the restrictions of target hardware. Therefore, we suggest a simple high-efficient module for the upsampling block called SimpleUp. As shown in

Figure 4, the encoding results

rn and dn are blended with the last-level decoding result

Dn-1 together in the

nth upsampling block (UP

n) by element-wise addition. We adopt element-wise addition rather than concatenation, because the concatenation will increase the channels of features and consume the additional resource for the subsequent convolution operation. The SimpleUp consists of a 5×5 convolution kernel to reduce the channel number by half followed by a bilinear interpolation to double the spatial resolution at each layer. In the convolution layers, adopting the depthwise separable convolution over the standard convolutions can further reduce the parameters of the decoding layers, making SimpleUp more efficient without performance degradation.

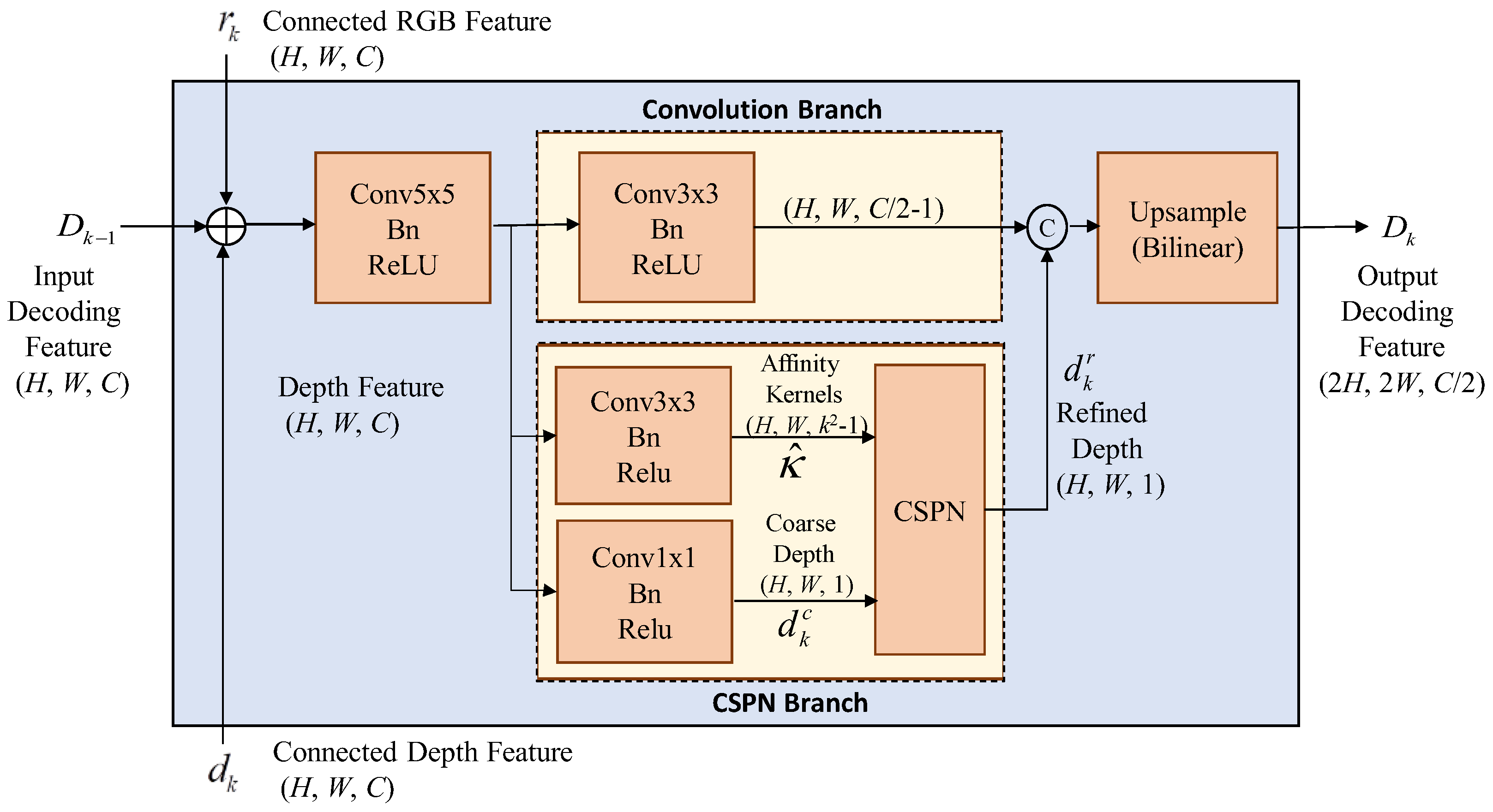

3.2.2. Upsampling by UpCSPN-k

With relative adequate resource, the complexity-moderate upsampling module called UpCSPN-

k can be selected for the high-accuracy applications. The UpCSPN-

k utilizes CSPNs over the layers of decoder to iteratively produce the refined depths. As shown in

Figure 5, the input RGB feature

rn and depth feature

dn with the size of (

H,

W,

C) in the

nth layer are passed through a 5×5 convolution then divided into two branches,

convolution branch and CSPN branch.

In

Figure 5, the convolution branch performs a 3×3 standard convolution and outputs the features with the size of (

H,

W, (

C/2)-1). In the meanwhile, the

CSPN branch is composed of two prediction heads, which produce a coarse depth map

with the size of (

H,

W, 1) and a predicted affinities map

with the size of (

H,

W,

k2-1) where

k is the kernel size of CSPN. For each pixel

x in

, the convolution weights of channels can help to convey the information of pixels through the spatial average. Thus, the refined depth

through the CSPN processing in each decoding layer can be obtained as

where

x denotes the pixel indices,

xn denotes the local neighborhood

Nx around

x and “

” is the element-wise production. The refined affinity of

x is given as

where the normalization of predicted affinities map

is performed by

After the CSPN processing, the refined depth is concatenated with the features of convolution branch, and then the spatial resolution of concatenated results is doubled by a bilinear interpolator for each decoding layer. Although the UpCSPN-k consumes more computation resource, the upsampling by UpCSPN-k can achieve the more accurate interpolation with the lower error rate than that by SimpleUp.

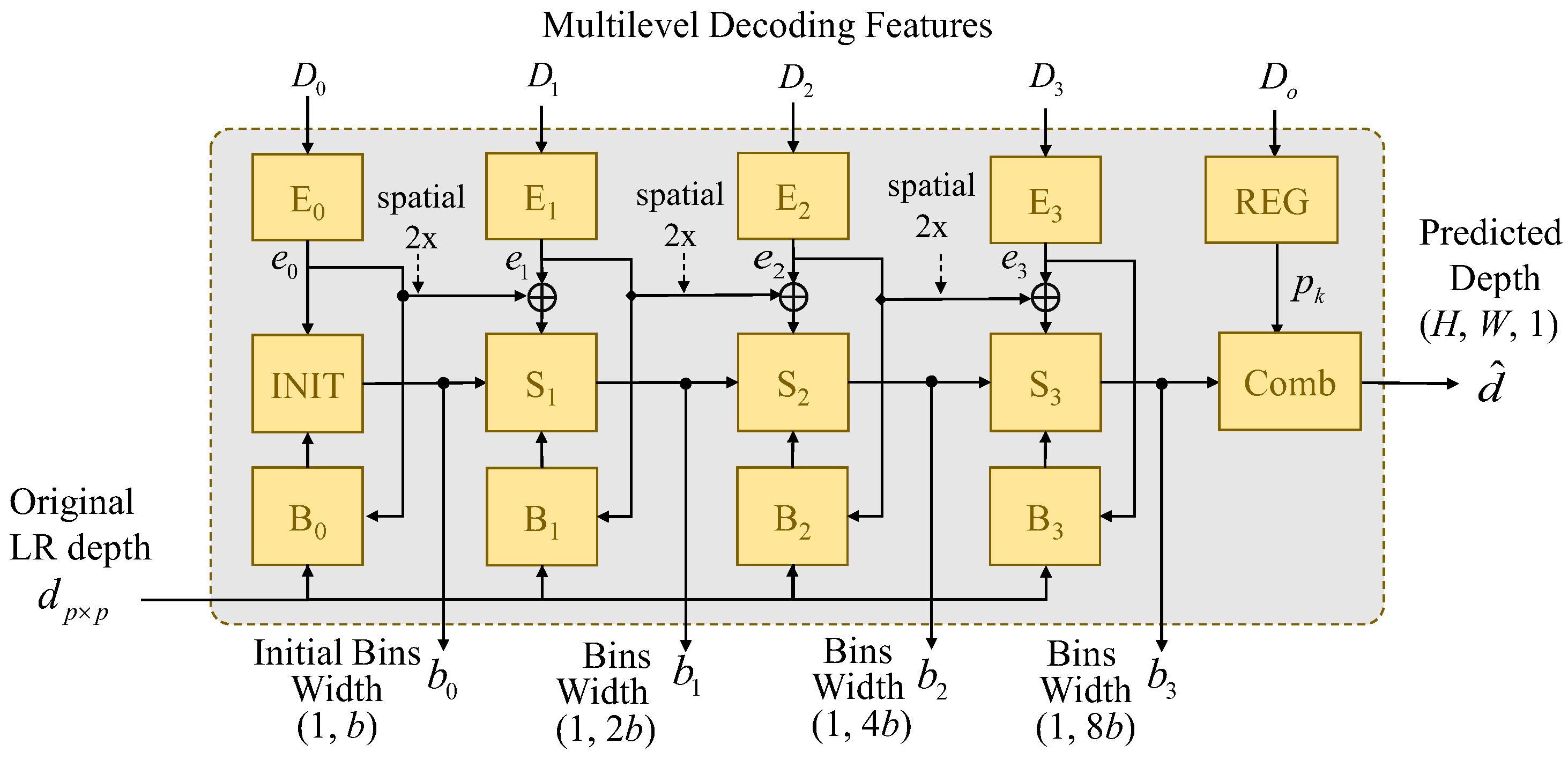

3.3. Adaptive Bins Estimator

After the multilevel shared decoder, the multilevel decoding features,

D0,

D1,

D2,

D3, and

D4 are sent into the proposed adaptive dynamic range bins (AdaDRBins) estimator. The AdaDRBins estimator employ these multilevel decoding features and the original LR depth map,

dpxp to produce a set of predicted bins width {

b0,

b1,

b2,

b3} and the predicted depth map , as shown in

Figure 6.

The AdaDRBins estimator consists of four types of multiple layer perceptron (MLP): features embedding MLP (En-symbolized block), bins initialization MLP (INIT-symbolized block), bins splitter MLP (Sn-symbolized block) and bias prediction MLP (Bn-symbolized block). Those MLPs exploit the individual fully-connected (FC) structures to project the data into the different specified dimensions. The combination of those MLP can make the gaps of bins be more and more fine-grained in the bins estimator

3.3.1. Feature Embedding MLPs (En)

The decoded features are first passed through Feature embedding MLPs layers. The embedding MLPs project the nth decoding features Dn with the size of (Hn, Wn, Cn) to become the nth embedding features, en, with the size of (Hn, Wn, Ce). The channel dimension Ce of embedding features now become the same size, which is referred as “embedding space”. Tab. 1 shows the detailed architecture of feature embedding MLPs that the proper channel dimension is assigned by Ce =32 in our experiments. The subsequent layers within the AdaDRBins module utilize these embedding features to determine the appropriate bin division for each video frame.

Table 1.

Details of feature embedding MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

Table 1.

Details of feature embedding MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

| Layer type |

Input channels |

Output channels |

Activation |

| FC |

Cn |

64 |

GeLU |

| FC |

64 |

Ce=32 |

- |

3.3.2. Bins Initialization MLPs (INIT):

The input of INIT is the first embedding feature denoted by e

0 which is obtained from bottleneck of the decoder. The INIT generates an initial bin division, which is treated as coarse bin division, to serve as the starting point of bin division refinement. In the subsequent bins estimating layers, each bin will be consecutively split into two new bins layer by layer. To fit the range of training datasets, the predicted bins division is re-scaled by

where

and

denote the predicted minimal depth and maximal depth of bias prediction MLP B

0, respectively. Tab. 2 shows the detailed architecture of INIT MLPs.

Table 2.

Details of INIT MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

Table 2.

Details of INIT MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

| Layer type |

Input channels |

Output channels |

Activation |

| FC |

32 |

64 |

GeLU |

| FC |

64 |

b |

RLU |

| Global AvgPool |

- |

-- |

- |

3.3.3. Bins Splitter MLPs (Sn)

After bins initialization, the initial bin division is sent to the bins splitter MLPs to perform the coarse-to-fine bins generation strategy. The bins splitter MLPs play an important role in determining the distribution of bins, based on their respective bin embeddings. In essence, they acts as decision-makers to determine how the previous bin division should be divided for improving the precision and the resolution of bins. As shown in

Figure 6, the interpolated embedding features of previous layer are element-wisely added with the embedding features of current layer and then fed into the next bin splitter MLP. After the FC layer in each bins splitter MLP, the features are passed through a Sigmoid activation to obtain a split score vector denoted by

. The scores in this vector determine how each previous bin is divided into two bins. Let

denote the previous bins division,

denoting the bins division after the bin splitter MLP becomes

This binning processing increases the granularity and resolution as the layers progress, ultimately improving the quality of the output. Similar to INIT, the output bin divisions are re-scaled to fit the depth range of the training dataset, given by

where

and

are the predicted minimal depth and maximal depth of bias prediction MLP

Bn.

Table 3 details the architecture of the

nth splitting MLPs.

Table 3.

Details of the nth splitting MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

Table 3.

Details of the nth splitting MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

| Layer type |

Input channels |

Output channels |

Activation |

| FC |

32 |

64 |

GeLU |

| FC |

64 |

|

- |

| Global AvgPool |

- |

-- |

- |

3.3.4. Bias Prediction MLPs (Bn)

For low-resolution depth inputs, we only have a rough understanding of the depth distribution in the scene. Our general idea is to constrain the predicted depth range, making the bins prediction closer to the ground truth depth range. Since the minimum and maximum depths in low-resolution depth map may not be identical to the true minimum and maximum depths in ground truth, a bias term is needed for compensating the predictive offset. The bias MLP consists of two inputs: the low-resolution depth map

dpxp and the embedding feature

en. The outputs are the estimated minimum depth and maximum depth of the scene. The embedding feature is passed through a bias prediction MLP to estimate the minimum and maximum depths. The estimated biases are respectively added to the minimum value and maximum value of the resolution depth map as

where

and

are the predicted biases generated by the bias prediction of B

k. The predicted minimum depth and maximum depth are then fed into bin initialization MLP and bin splitter MLP with the more accurate dynamic depth range of current scene. Tab.4 details the architecture of the

nth bias MLPs.

Table 4.

Details of the nth bias MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

Table 4.

Details of the nth bias MLPs while keeping the same Hn and Wn.

| Layer type |

Input channels |

Output channels |

Activation |

| FC |

32 |

32 |

GeLU |

| FC |

64 |

2 |

- |

| Global AvgPool |

- |

-- |

- |

After the prediction of these MLPs, the final bin division

b3 is obtained. In the final stage of AdaDRBins, a hybrid regression layer (REG) is used on the final decoded feature

D0 to estimate the probabilities of each pixel falling into these bins. The hybrid regression layer consists of a 3×3 convolution followed by a softmax activation unit which results in the predicted probability

pi for the

ih bin. Then, the predicted probabilities are applied to perform the linear combination with the predicted final bin-centers

, which is given by

for achieving the final predicted depth map

. The predicted depth at (x, y) in

can be obtained by

where

pi(x,y) is the probability of predicted depth at

(x,y) falling in the

ih bin.

3.4. Loss Functions

Similar to AdaBins, we employ two loss terms to assemble the loss function which is designed as

where

and

denote the per-pixel regression loss and bin-centers distribution loss, respectively. With extensive experiments, the scalars

and

are selected to attain the stability of training our network.

3.4.1. Scale-Invariant Log Loss

We use masked scale-invariant log (SILog) loss proposed by Eigen et al. [

5] as the per-pixel regression loss. The loss term is defined by:

with

where

and

denote ground truth depth and predicted depth at pixel

i, respectively, and

N denotes number of valid pixels in ground truth depth (i.e.,

). Similar to AdaBins, we set λ = 0.85 in our experiments.

3.4.2. Bin-Centers Distribution Loss

Similar to primary AdaBins, the chamfer distance [

31] is adopted as the bin center distribution loss in order to supervise the distribution of predicted bin centers. Let

denotes the set of predicted bin centers at different scale and

denotes the set of valid ground truth values. The loss term is given by

where the chamfer distance is defined as

This loss term promotes the alignment between the distribution of bin centers and the distribution of ground truth depth values by pushing the bin centers to match the actual depth values in average.

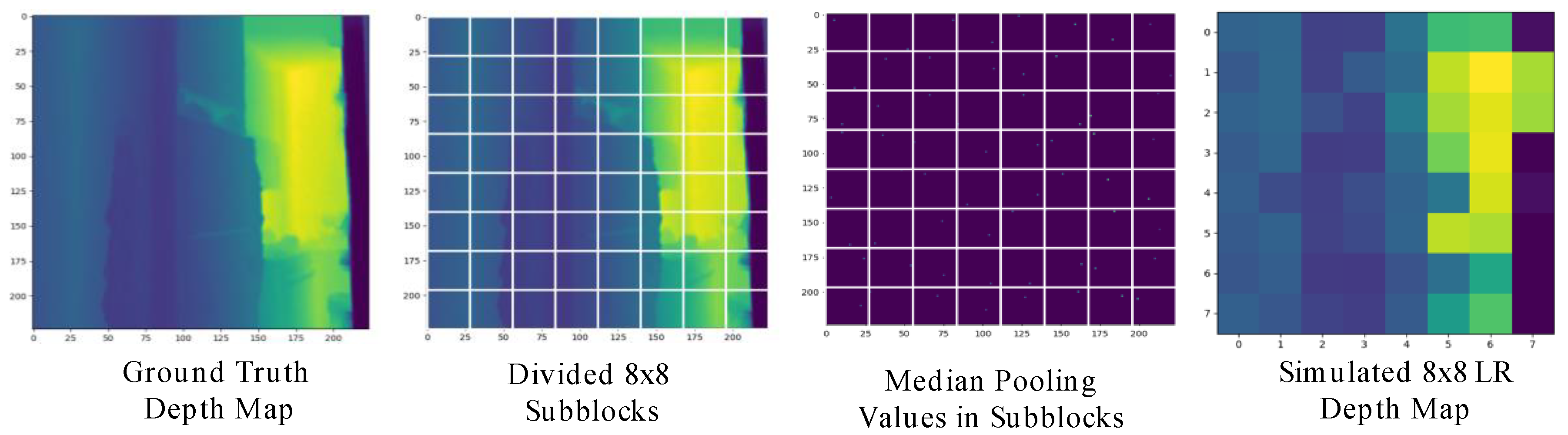

3.5. LR Depth Generation for Training

In order to simulate the LR depth maps obtained from MR glasses for training, we introduce a depth sampling method that generates low-resolution depths randomly from the ground truth.

Figure 7 shows the results of LR depth generation with

p = 8 by our proposed simulation strategy, where the proposed two-step LR depth generation is stated as follows:

- Step 1.

Subblocking: To obtain a p×p low-resolution depth map from the ground truth depth map d, we first divide the ground truth depth map into p×p subblocks.

- Step 2a.

Median pooling: We simply take the median value of each sub-block as the LP depth value to obtain the simulated LR depth map.

- Step 2b.

Max-depth filtering (optional): In practical, the depth range on most MR glasses depth sensors is limited to a short distance range. To simulate the short distance range depth during training, we apply max-depth filtering on the sampled low-resolution depth map. As the depth value is greater than a max-depth threshold, max-depth filtering will reset the depth value to zero (i.e., invalid pixel)

4. Experimental Results

In this section, we will first describe the datasets and implementation settings. Then, we will exhibit the depth estimation performance achieved by the proposed network in various evaluation criteria.

4.1. Datasets and Implementation Settings

We use NYU Depth V2 Dataset [

32] and EgoGesture Dataset [

33] as our training datasets. The NYU Depth V2 provides the pairs of RGB images and the corresponding depth map for indoor scenes. The image and depth map resolution of the dataset are captured at 640×480 from Microsoft Kinect which renders the maximum sensible distance of 10 meters. We employ the official train/test split in our experiments, which comprises 12K training samples and 654 testing samples. The EgoGesture Dataset provides RGB images and the depth map of diverse hand gestures. The dataset is gathered by Intel RealSense SR300 with resolution 640×480. The dataset encompasses four indoor scenes and two outdoor scenes. In total, the dataset contains 2,953,224 hand gesture frames collected for the RGB and depth modality, respectively.

Our experiments are implemented with Python 3.9, PyTorch 1.10.2 [

34], CUDA 11.3 and cuDNN 8.2 on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS operating system. We trained our network using single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB memory and Intel i7-13700K CPU. During training, we utilize the batch size of 16 and Adam [

34] optimizer with (0.95, 0.99) betas and 0.1 weight-decay. The proposed depth estimation network is trained over 50 epochs with the learning rate starting from 0.000357 and decaying 20% every 5 epochs.

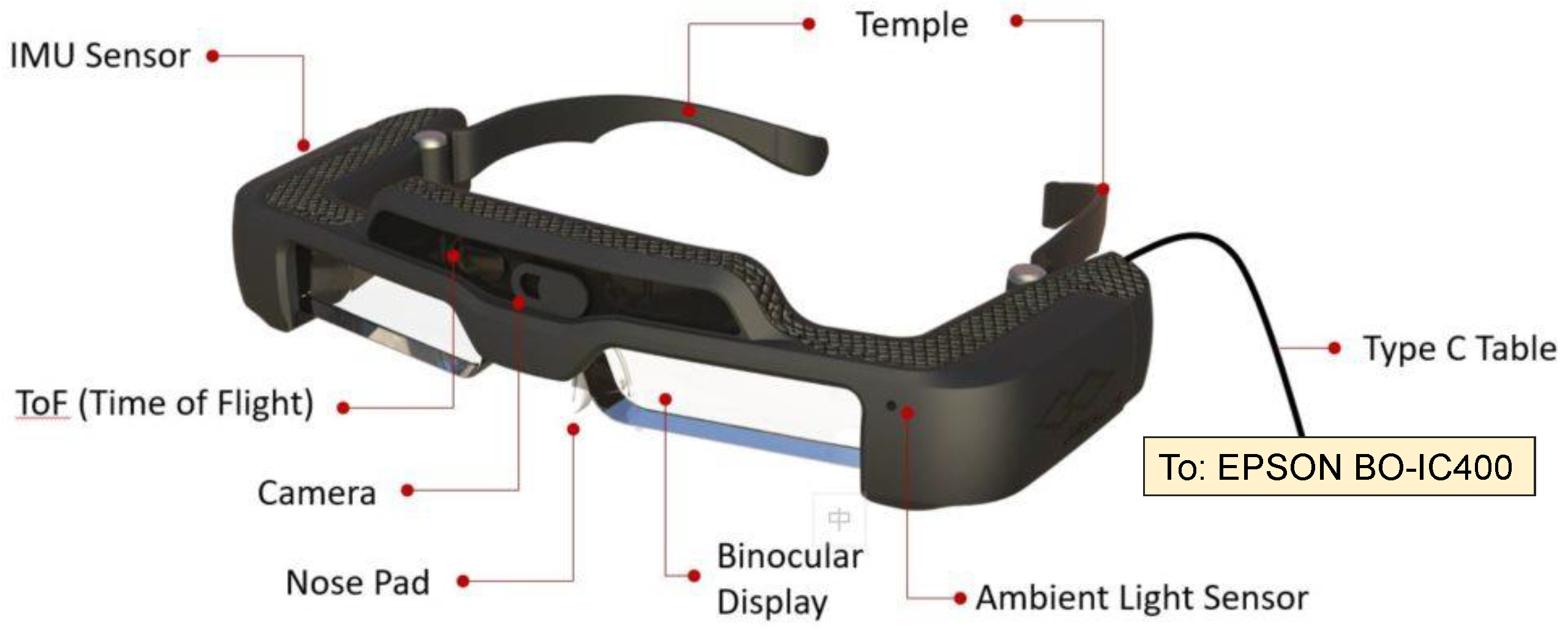

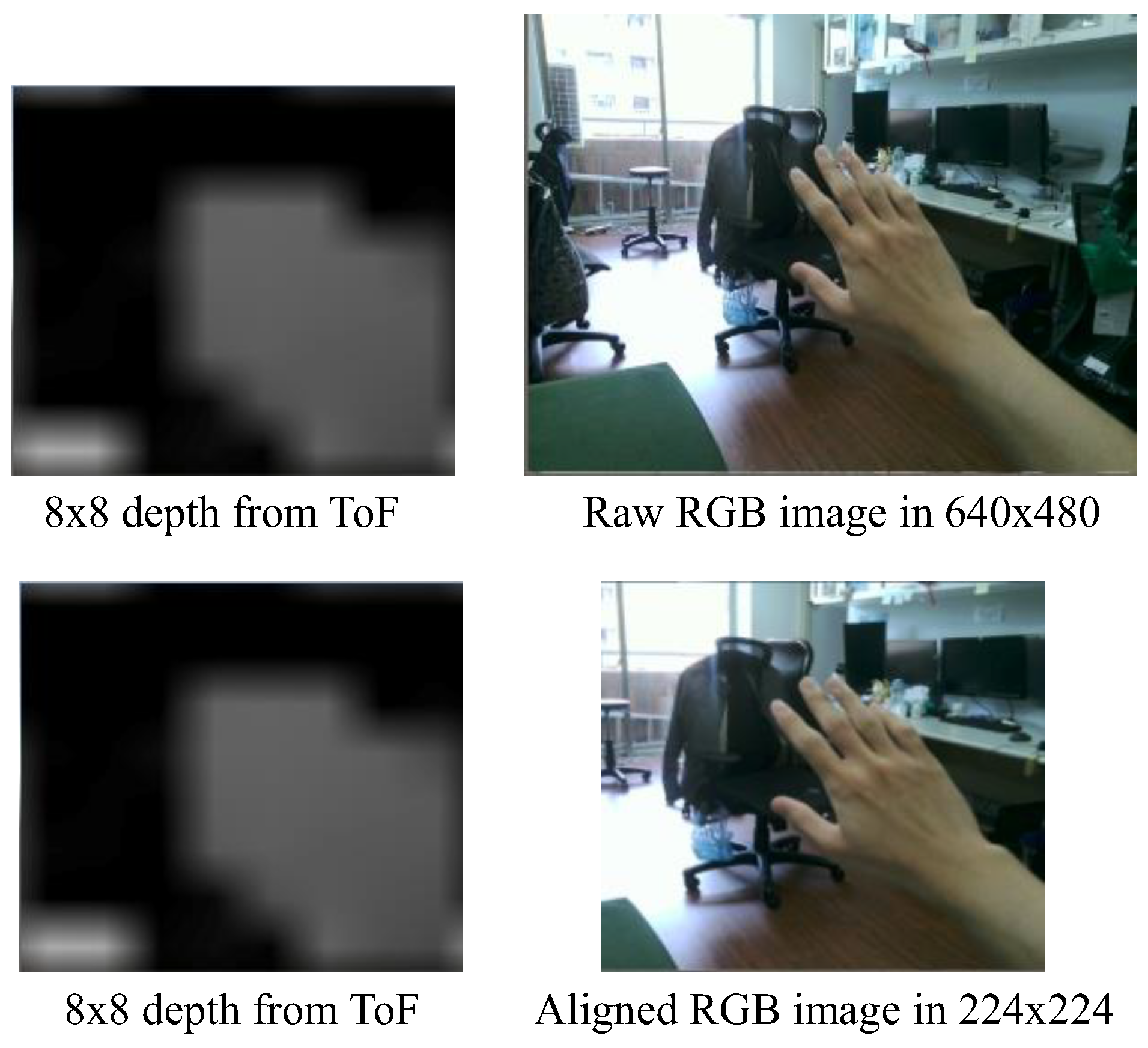

4.2. Proposed Network Implementation on Low-cost MR Glasses

The profile and components of Jorjin J7EF Plus AR glasses are described by

Figure 8 which contains two major parts: an MR goggle with several sensors and a computation device connected through USB type C connector. There are several useful sensors built on this MR goggle, including time-of-flight (ToF), RGB camera, gyroscope, accelerator and magnetometer. The resolution of the ToF sensor is 8×8 and its sensing distance range is roughly within 3 meters, which is comparably low. Our goal is to utilize the LR depth map and RGB images from Jorjin’s MR glasses to get precise and high-resolution depth map by using EPSON BO-IC400 platform [

35], which adopts Qualcomm SXR1130 processor with 4GB memory and 64GB storage.

For Jorjin MR-glasses sensor, the resolutions of captured raw RGB image and depth map are 640×480 and 8×8, respectively. Since the spatial positions of RGB and depth images must be fully aligned, we first resize the raw RGB image into 360×270 and crop the region

RGBcrop = {(

x,

y): 68 ≤

x ≤ 191, 23 ≤

y ≤ 246} to make the cropped color images be 224×224 RGB images for further aligning with depth maps. We tried the spatial transformer network to align the RGB and depth images. However, this deep learning network not only consumes additional cost, but also causes some unpredictable inaccuracies in the alignment. Hence, we adopt a semi-automatic alignment by the aid of easy manual refinement that an alignment result for Jorjin MR-glasses data is displayed by

Figure 9. Because the calculation of depth-estimation loss directly exploits the high-resolution GT depth maps provided by NYU Depth V2 dataset and EgoGesture dataset. Those high-resolution GT depth maps are downsampled as the sensor-labeled 8×8 depth maps for training our networks.

For verifying the feasibility of our model for resource-limited MR glasses, we implement the simplest model with the sole-SimpleUp decoder w/o AdaDRBins. The Unity with version: 2020.3.29f1 is used as our engine to build the virtual scene on MR glasses. Jorjin provided the software development kit (SDK) for MR glasses on Unity, we can access the MR sensor data with Unity scripting API in C# language. We use Barracuda Unity 3.0.0 as our model inference library. Barracuda Unity provides a lightweight and cross-platform neural network inference API for Unity. It can inference neural network in ONNX (Open Neural Network Exchange) format directly on both CPU and GPU of supported platforms.

For indoor scenes, the model is trained on the NYU Depth V2 dataset, we apply max-depth filtering of 3 meters on the depth training samples. For hand gesture scenes, the model is trained on the EgoGesture dataset, we apply max-depth filtering of 1.5 meters on the depth training samples.

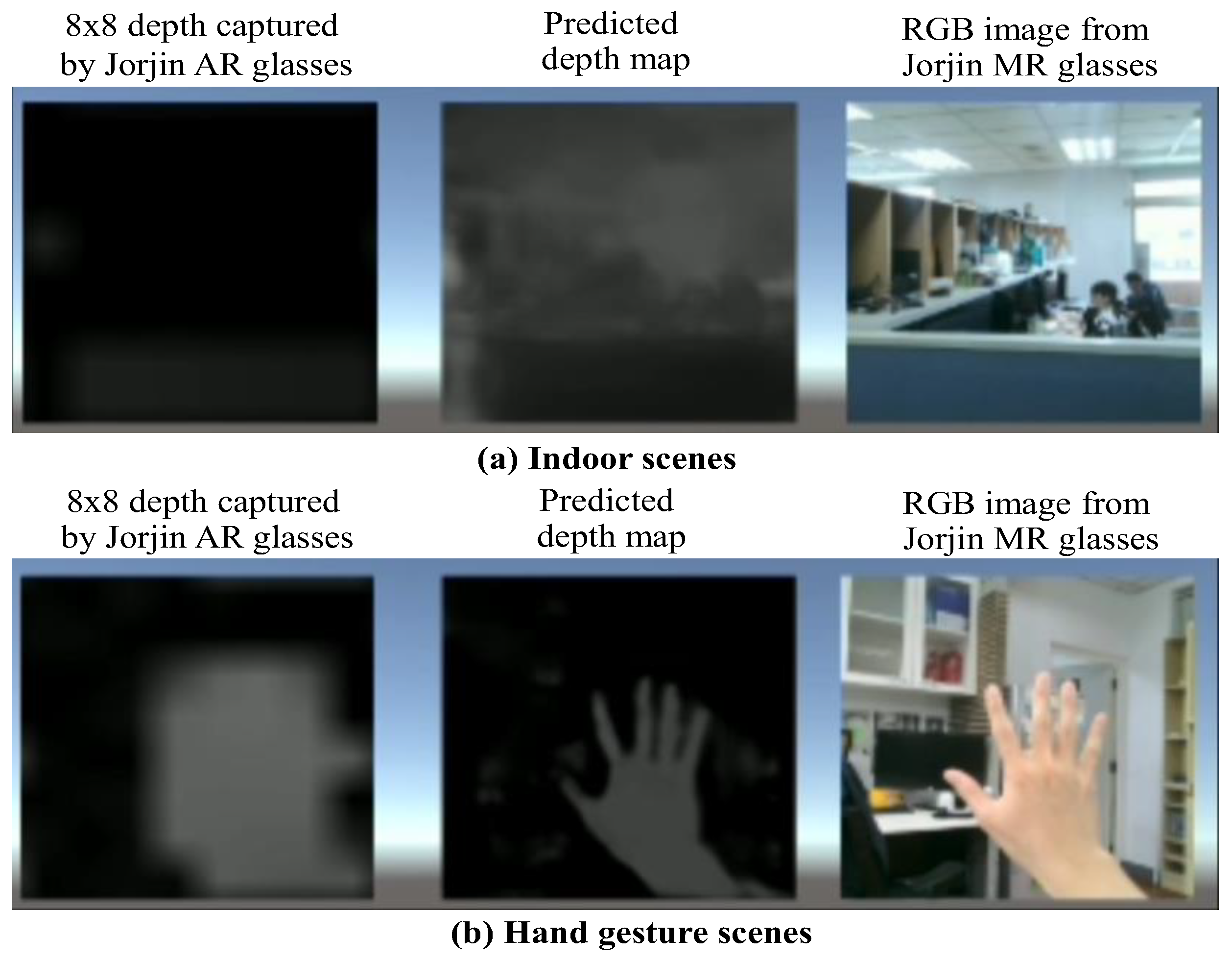

Figure 10 displays the estimated high-precision depths for indoor and dynamic hand scenes on Jorjin MR glasses by the simplest model with only SimpleUp decoder w/o AdaDRBins. There are three windows, 8×8 depths captured by the ToF sensor, the depth estimation result predicted by our proposed network, and RGB image captured by Jorjin MR glasses. For the result of indoor scenes, we can see the network roughly understand the depth information of the scene. However, the depth sensing range of the MR glasses is very low. Consequently, the quality of the predicted images is not good as what we demonstrated in the experiments. For the hand gesture scenes, since the distance range of hand gestures can fit the short depth sensing range of ToF sensor, the position and distance of hand making a gesture can be clearly identified. We believe that with the high-resolution depth information on MR glasses, many applications can be more accurate. To see the hand gesture demos in details, one can download

Video S1: EgoGesture demo.mp4 at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1.

4.3. Performance Evaluation Results

For the experiments, we adopt MobileNet-s as the encoder. We use the official testing split, which contains 654 testing samples, to test the performances by using average evaluation metrics. The resolution of RGB images is set to 224×224 and the resolution of simulated LR depth is set to 8×8.

We compare the proposed models to the FastDepth [

10] with ResNet50+NNConv5, FastDepth [

10] with MobileNet+NNConv5, and the MonoDepth [

13] with ResNet50+ DispNet for 224×224 RGB input images. As

Table 5 shown, the computational burdens of two compared latters are about 4.8 G MACs and 0.74 G MACs, respectively. In our proposed network, the Dual MobileNet encoder including 6 depthwise separable convolution layers and one pointwise convolution totally requires about 0.185G MACs. In

Table 5 , three proposed models using the solo-SimpleUp decoder, the SimpleUp+AdaDRBins decoder and the UpCSPN-7+AdaDRBins decoder are chosen to display their computational complexities in order. These three models demand 0.675 (i.e., 0.185+0.49), 1.335 (i.e.,0.185+1.15) and 9.445 (i.e.,0.185+9.26) G MACs, respectively. Not only the proposed simplest model, which adopts the solo-SimpleUp decoder, is lighter than the fastest version of FastDepth in MACs, but also achieves the lower 0.233 RMSE than its 0.599 RMSE obtained for testing the NYU Depth V2 dataset. It is noted that the MonoDepth tested on the KITTI dataset attains 4.392 RMSE in monotonous outdoor scenes. Thus, for the more complex indoor dataset, e.g., the NYU Depth V2 dataset, the RMSE of MonoDepth shall be larger than 4.392 such that we enlisted the RMSE of MonoDepth as “>4.392” in

Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparisons of FastDepth, MonoDepth and the various proposed variants by using the NYU Depth V2 dataset.

Table 5.

Comparisons of FastDepth, MonoDepth and the various proposed variants by using the NYU Depth V2 dataset.

| Network |

Encoder |

Decoder |

Weights (M) |

MAC(G) |

RMSE |

| FastDepth [10] |

ResNet50 |

NNConv5 |

25.60 |

4.190 |

0.568 |

| FastDepth [10] |

MobileNet |

NNConv5 |

3.19 |

0.740 |

0.599 |

| MonoDepth [13] |

ResNet50 |

DispNet |

30.00 |

4.800 |

>4.392. |

| Proposed |

DMobileNet_s |

SimpleUp |

2.18 |

0.675 |

0.223 |

| Proposed |

DMobileNet_s |

SimpleUp+

AdaDRBins |

2.28 |

1.150 |

0.199 |

| Proposed |

DMobileNet_s |

UpCSPN-7+ AdaDRBins |

43.57 |

9.445 |

0.185 |

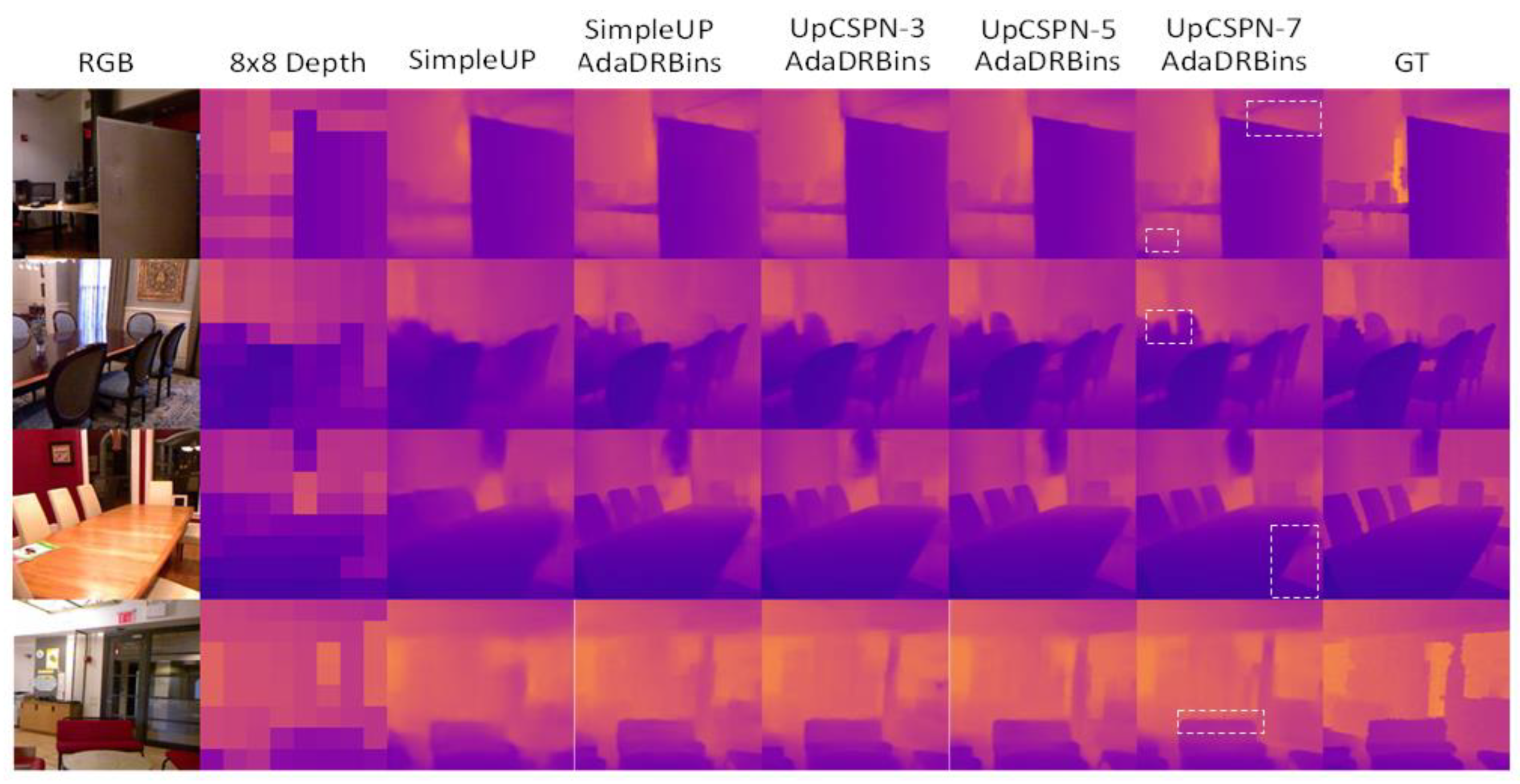

Figure 11 shows the qualitative results of our proposed network on NYU Depth V2 Dataset. We observe that the depth maps achieved by the combination of UpCSPN-k mand AdaDRBins modules preserve more details and clearer boundaries than those obtained by SimpleUp. However, the depth maps resulted from the model with the solo-SimpleUp decoder are still clear and recognizable. For considering the balance of complexity and precision, the combination of SimpleUP and AdaDRBins could be a good solution for the resource-limited platforms. Particularly, observing the 2nd and 4th rows of

Figure 11, the rectangle-highlighted depth areas resulted by the proposed network using UpCSPN-7+AdaDRBins decoder can be even better than the corresponding depth areas in GT maps in terms of visual rationality.

4.4. Ablation Study

For the ablation study, we exhibit the quantitative metrics of proposed networks with different amounts and complexities of ingredients in

Table 6 and

Table 7. The simulation results show that our simplest architecture of the decoder, i.e., Solo-SimpleUp, achieves the comparable performance on NYU Depth V2 with incredibly fast inference speed, makes it more suitable to be implemented on mobile devices.

Table 6.

Quantitative results of the proposed networks achieved by different structures that REL expresses the relative error.

Table 6.

Quantitative results of the proposed networks achieved by different structures that REL expresses the relative error.

| Decoder |

Bins Estimator |

RMSE (m) |

REL |

|

|

|

| SimpleUp |

-- |

0.223 |

0.046 |

97.36 |

99.43 |

99.85 |

| UpCPSN-3 |

-- |

0.206 |

0.039 |

97.87 |

99.56 |

99.89 |

| UpCPSN-5 |

-- |

0.197 |

0.036 |

97.87 |

99.55 |

99.89 |

| UpCPSN-7 |

-- |

0.202 |

0.036 |

97.87 |

99.54 |

99.89 |

| SimpleUP |

AdaBins |

0.197 |

0.037 |

98.04 |

99.64 |

99.91 |

| SimpleUp |

AdaDRBins |

0.199 |

0.038 |

98.06 |

99.64 |

99.91 |

| UpCSPN-3 |

AdaDRBins |

0.190 |

0.036 |

98.21 |

99.67 |

99.92 |

| UpCSPN-5 |

AdaDRBins |

0.191 |

0.036 |

98.21 |

99.67 |

99.92 |

| UpCSPN-7 |

AdaDRBins |

0.185 |

0.034 |

98.24 |

99.67 |

99.92 |

Table 7.

Computational analyses of the proposed networks with different structures where MAC expresses the number of multiply-accumulate operations.

Table 7.

Computational analyses of the proposed networks with different structures where MAC expresses the number of multiply-accumulate operations.

| Decoder |

Bins Estimator |

#Bins |

Weights (M) |

MAC(G) |

FPS |

| SimpleUp |

-- |

- |

2.18 |

0.49 |

1170 |

| UpCPSN-3 |

-- |

-- |

41.85 |

8.04 |

367 |

| UpCPSN-5 |

-- |

-- |

42.13 |

8.36 |

356 |

| UpCPSN-7 |

-- |

-- |

42.57 |

8.60 |

337 |

| SimpleUp |

AdaBins |

256 |

4.52 |

4.43 |

425 |

| SimpleUp |

AdaDRBins |

32 |

2.28 |

1.15 |

560 |

| UpCSPN-3 |

AdaDRBins |

32 |

42.85 |

8.70 |

340 |

| UpCSPN-5 |

AdaDRBins |

32 |

43.14 |

8.92 |

330 |

| UpCSPN-7 |

AdaDRBins |

32 |

43.57 |

9.26 |

310 |

Although the combinations of UpCSPN-k and AdaDRBins have lower inference speeds, their performances are much higher than the model with the solo-SimpleUp decoder. As

Table 6 shown, the decoder with UpCSPN-7 and AdaDRBins can make the generated depth maps acquire a very high precision with RMSE 0.185, which is lower the RMSEs achieved by the existing AdaBin-based networks [

12,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], i.e., with RMSEs higher than 0.19 for various task-specific testing images

5. Discussion

In this study, for low cost MR applications, the proposed depth estimation algorithms with lightweight encoders and simpleUp multilevel share decoder. The simplest network with only 2.18M parameters is successfully implemented in Jorjin J7EF Plus AR glasses. It is noted that the proposed network with lightweight encoders, UpCPSN-7 multilevel share decoder and AdaDRbins can achieve the highest precision performance in depth estimation, better than AdaBines-based networks.

We can divide the models of proposed network into 4 groups that their decoders are “Solo-SimpleUp”, “UpCPSN-k only”, “SimpleUP+AdaxBins” (AdaxBins can be AdaBins and AdaDRBins), “UpCSPN-k+AdaDRBins”. Observing

Table 7 , we find that the RMSEs of models between different groups have the salient differences, and the RMSEs of models in the identical group have close RMSEs. Even that, in the second group, i.e., UpCPSN-k only, the “UpCPSN-5 only” decoder is better than the “UpCPSN-7 only” decoder. This fact can manifest an evidence for the deep learning investigation that the more stacked layers could not guarantee better performance. We can claim that the better structure design is more important than the use of larger amounts of kernels.

In this study, we follow the rule of gradually increasing the stacked ingredients and layers to develop our networks. The content of Tab.6 can imply that the model with the “SimpleUP+AdaBins” decoder could be a teacher network to distillate the model with the solo-SimpleUp decoder. Similarly, the model with the UpCSPN-l+AdaDRBins decoder can play a teacher role for the model the UpCSPN-m+AdaDRBins decoder for l > m. Hence, based on this design strategy, the teacher-and-student structure can be easily attained by arbitrarily reducing the layers of a complex model for distillation.

Because the depths captured by the ToF depth camera in MR-glasses are very sparse, the original depths near fingers are mostly lost during hand-moving actions. The high-resolution depth predicted by our proposed networks can greatly support the accurate estimation of hand gestures in complex backgrounds. The predicted depths of finger pixels could provide better foundation for recognition of subtle 3D hand gestures.

It is noted that the proposed network should further investigate the vulnerabilities posed by adversarial examples when the MR glasses involve security sensitive applications, such as medical surgery and military security checks, etc. In the future, the proposed networks could consider a robust technique involving camouflage through the use of adversarial examples [

36].

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced the lightweight dual-path autoencoder and the adaptive dynamic range bins estimator architecture for estimation of highly accurate depth maps for resource-limited MR applications, which are based on an RGB image and a low-resolution depth map. The proposed approaches with different effective decoding modules yield impressive depth estimation results, particularly for indoor scenes and hand gestures. According to simulation results, we firmly believe that the proposed models with various combinations are well-suited for the deployment on light-weight mobile devices, MR glasses and AR apparatuses. By providing precise and dense depth information, the proposed networks can help greatly enhancing the accuracy of MR applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Video S1: EgoGesture demo.mp4. The link

https://youtu.be/XFgtftdPQls demos a practical video fragment in the downstream depth estimation task. The model with the Solo-SimpleUp decoder trained by NYU Depth V2 Dataset and EgoGesture datasets achieved the depth estimation inference for the practical moving hand with dynamic gestures. The middle successive depth maps in the exhibited triple-image video are the inferred high-resolution depth maps.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y. and H.T.; methodology, W.Y. and H.T.; software, H.T.; validation, W.Y. and D.C.; formal analysis, W.Y.; investigation, D.C.; resources, W.Y.; data curation, H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.; writing—review and editing, W.Y. and D.C.; visualization, W.Y.; supervision, W.Y.; project administration, W.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. and D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan under Grant: NSTC 113-2221-E-017-009.(W.Y.) and NSTC 113-2221-E-415-010 (D.C.)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

In this paper, we use public datasets, NYU Depth V2 Dataset [

30] and EgoGesture Dataset [

31] to train the networks for experimental comparisons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MR |

Mixture Reality |

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| 3D |

Three Dimensional |

| RGB |

Red, Green and Blue |

| LiDAR |

Light Detection And Ranging |

| ToF |

Time-of-Flight |

| LED |

Light Emitting Diode |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| CSPN |

Convolutional Spatial Propagation Network |

| SPN |

Spatial Propagation Network |

| LR |

Low Resolution |

| HR |

High Resolution |

| MLP |

Multiple Layer Perception |

| SILog |

Scale Invariant Log |

| CD |

Chamfer Distance |

| NYU |

New York University |

| ONNX |

Open Neural Network Exchange |

| CPU |

Central Processing Unit |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

References

- Fabrizio F.; De Luca, A. Real-time computation of distance to dynamic obstacles with multiple depth sensors. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 56-63, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kauff, P.; Atzpadin, N.; Fehn, C.; Müller, M.; Schreer, O.; Smolic. A.; Tanger, R. Depth map creation and image-based rendering for advanced 3DTV services providing interoperability and scalability. Signal Processing: Image Communication, vol. 22, no. 2, February 2007, pp.217-234. [CrossRef]

- Fehn, C. Depth-image-based rendering (DIBR), compression, and trans-mission for a new approach on 3d-tv. in Stereoscopic Displays and Virtual Reality Systems XI, vol. 5291. SPIE, 2004, pp. 93-104. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-J.; Yang, J.-F.; Chen, G.-C.; Chung, P.-C.; Chung, M.-F. An assigned color depth packing method with centralized texture depth packing formats for 3D VR broadcasting services. IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 122–132, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Natan, O.; Miura, J. End-to-end autonomous driving with semantic depth cloud mapping and multi-agent. IEEE Trans. on Intelligent Vehicles, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 557-571, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.; Murphy, R. R. Hand gesture recognition with depth images: A review. in RO-MAN: The 21st IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication. 2012, pp. 411–417. [CrossRef]

- Hirschmuller, H. Stereo processing by semiglobal matching and mutual information. in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 328-341, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Eigen, D.; Puhrsch, C.; Fergus, R. Depth map prediction from a single image using a multi-scale deep network. in Proc. of Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 2366-2374, 2014.

- Alhashim, I.; Wonka, P. High quality monocular depth estimation via transfer learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.11941, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wofk, D.; Ma, F.; Yang, T.-J. Karaman, S.; Sze, V. Fastdepth: Fast monocular depth estimation on embedded systems. in 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2019, pp. 6101–6108. [CrossRef]

- Laina, I.; Rupprecht, C.; Belagiannis, V.; Tombari, F.; Navab, N. Deeper depth prediction with fully convolutional residual networks. in 2016 Fourth international conference on 3D vision (3DV). IEEE, pp. 239–248, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. F.; Alhashim, I.; Wonka, P. Adabins: Depth estimation using adaptive bins. in Proc. of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 4009–4018. [CrossRef]

- Godard, C.; Aodha, O. M.; Brostow, G. J. Unsupervised monocular depth estimation with left-right consistency. in Proc. of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 270-279, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Godard, C.; Aodha O., M.; Firman, M.; Brostow, G. J. Digging into self-supervised monocular depth estimation. in Proc. of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 3828–3838, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Zama Ramirez, P.; Poggi, M.; Tosi, F.; Mattoccia, S.; Di Stefano, L. Geometry meets semantics for semi-supervised monocular depth estimation. In Computer Vision – ACCV 2018. vol 11363. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kuznietsov, Y.; Stuckler, J.; Leibe, B. Semi-supervised deep learning for monocular depth map prediction. Proc. of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 6647–6655, July 2017. [CrossRef]

- Marti, E.; de Miguel, M. A.; Garcia, F.; Perez, J. A Review of sensor technologies for perception in automated driving. in IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 94-108, winter 2019. [CrossRef]

- Foix, S.; Alenya, G.; Torras, d C. Lock-in time-of-flight (ToF) cameras: A Survey. in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 1917-1926, Sept. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Jorjin J7EF Plus AR glasses. https://www.jorjin.com/products/ar-vr-glasses/j-reality/j7ef/.

- Ma, F.; Karaman, S. Sparse-to-dense: Depth prediction from sparse depth samples and a single image. in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, pp. 4796–4803, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Tian, F.-P; Feng, W.; Li, J.; Tan, P. Learning guided convolutional network for depth completion. in IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 30, pp. 1116–1129, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, P.; Yang, R. Depth estimation via affinity learned with convolutional spatial propagation network. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; De Mello, S.; Gu, J.; Zhong, G.; Yang, M.-H.; Kautz, J. Learning affinity via spatial propagation networks. Proc. of Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 30, 2017.

- Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, X. X. HTC-DC Net: Monocular height estimation from single remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 61, no. 5623018, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Miclea, V.–C.; Nedevschi, S. SemanticAdaBins - Using semantics to improve depth estimation based on adaptive bins in aerial scenarios,” In Proc. of 4th International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME) 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yuan, L.; Wilber, K.; Sharma, A.; Gu, X.; Qiao, S. PolyMaX: General dense prediction with mask transformer. In Proc. of IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jaisawal, P. K.; Papakonstantinou, S. Monocular fisheye depth estimation for UAV applications with segmentation feature integration,” In Proc. of IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC). 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Y.; Kim, D. J.; Suh, Y. J.; Hwang, D. K. Improving monocular depth estimation through knowledge distillation: better visual quality and efficiency. IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 2763 – 2782, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. F.; Birkl, R.; Wofk, D.; Wonka, P.; Muller, M. ZoeDepth: Zero-shot transfer by combining relative and metric depth. in Proc. of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, arXiv:2302.12288, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Howard, A. G.; Zhu M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04861, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Su, H.; Guibas, L. A point set generation network for 3d object reconstruction from a single image." in 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pages 2463–2471, 2017.

- Silberman, N.; Hoiem, D.; Kohli, P.; Fergus, R. Indoor segmentation and support inference from rgbd images. in European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, pp. 746–760, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, C.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Egogesture: A new dataset and benchmark for egocentric hand gesture recognition. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 1038–1050, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; Desmaison, A.; Kopf, A.; Yang, E.; DeVito, M.; Raison, M.; Tejani, A.; Chilamkurthy, S.; Steiner, B.; Fang, L.; Bai, J.; Chintala, S. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol.32, pp. 8026–8037, 2019.

- EPSON MOVERIO BO-IC400 User's Guide. https://download3.ebz.epson.net/dsc/f/03/00/16/15/46/95ef7d99574b1d519141f71c055ea50600b6b390/UsersGuide_BO-IC400_EN_Rev04.pdf.

- Lee, J.; Kim, T.; Bang, S.; Oh, S.; Kwon, H. Evasion attacks on deep learning-based helicopter recognition systems. In Hindawi Journal of Sensors, vol. 2024, Article ID 1124598. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).