Submitted:

05 July 2023

Posted:

07 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A comparison of 10 SLAM and VO methods, following the main classification described in the taxonomy (sparse-indirect, dense-indirect, dense-direct, sparse-direct), to identify the advantages and limitations of each method of those classifications.

- A comparison of three machine learning-based methods against their classic geometric versions to identify if there exist significative improvements in adding neuronal networks to classic approaches.

- An inferential statistical analysis that describes a correct procedure to identify significative differences based on the most suitable metrics for testing monocular RGB methods.

1.1. Related works

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxonomy

- Direct vs. indirect. Indirect methods refer to those algorithms that implement preprocessing steps, like feature extraction or optical flow estimation, before their pose and map estimation processes, so the amount of information that gets into the following steps gets considerably reduced, requiring less computational power but also reducing the density of the final 3D reconstruction. Indirect methods typically perform their optimization steps by minimizing the reprojection error due to the feature type of information that the preprocessing step outputs. On the other hand, direct methods work directly on pixel intensity information without requiring preprocessing steps, which implies that the algorithm has more information available for their estimation tasks, being available to obtain denser reconstructions of the scene but requiring more computational power. In addition, direct methods typically perform their optimization steps based on the photometric error due to the availability of direct pixel information.

- Dense vs. sparse. Dense vs. sparse classification refers to the amount of information recovered in the final map as a 3D reconstruction. Denser reconstructions have more definition and continuity in the reconstructed objects and surfaces. In contrast, sparser reconstructions are typically represented as point clouds largely separated where edges and corners are commonly the only types of objects that can be recognized clearly.

- Classic vs. machine learning. Classic methods have been proposed in the last three decades, typically basing their formulation on geometric, optimization, and probabilistic techniques without machine learning. However, in recent years, due to the impressive advances in artificial intelligence, especially in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), many techniques have been applied to improve SLAM or VO estimation tasks. The methods based on classic formulations and improved with machine learning are called Machine Learning based approaches (ML).

2.2. Selected algorithms

- ORB-SLAM2. As a sparse-indirect representant, we selected ORB-SLAM2 [35], which is widely known as the gold standard of this category, as most of the currently available sparse-indirect methods are proposals inspired by this algorithm. Original ORB-SLAM [36] extracts ORB features as preprocessing that are multiscale FAST corners with a 256-bit descriptor, which gives that algorithm information to perform a Bundle Adjustment for optimization and work in three threads for tracking, local mapping, and loop closure. In addition, ORB-SLAM2 incorporates a fourth thread to perform a full Bundle Adjustment after loop closure, which is demonstrated to improve the original method allowing it to obtain the optimal geometric representation of the scene. ORB-SLAM2 is publicly available as open source code in [37]; it can be implemented in its C++ version or ROS version, with minimum additional requirements, which are Pangolin, OpenCV (tested for 2.4.3 version), Eigen 3 (tested for 3.1.0 version), DBoW2 and g2o which are included in the repository.

- DF-ORB-SLAM. Classic-dense-indirect methods available in the literature, like [38,39], are not available as open-source code for implementations, so they could not be considered for this evaluation. Instead, a well-known classic-dense-direct version of ORB-SLAM2 exists, called DF-ORB-SLAM [13], with its code publicly available on GitHub. DF-ORB-SLAM algorithm was built based on the ORB-SLAM2 algorithm, allowing the addition of depth map retrieval capabilities and incorporating optical flow to track the detected points; thus, this algorithm uses a large amount of information obtained through the input using most of the pixel values for optical flow estimation. Once the optical flow is estimated, ORB-SLAM2 performs feature extraction on the optical flow domain and executes the rest of its pipeline. DF-ORB-SLAM is publicly available in [13], and it was implemented in Ubuntu 18.04 in its ROS version using its official build_ros.sh script.

- LSD-SLAM. LSD-SLAM [40] is one the most popular methods of the dense direct category since it has been the basis and inspiration of a lot of the methods currently available [7,18,41]. LSD-SLAM not only locally tracks the camera’s movement but also allows the construction of dense maps of the environment through a semi-dense geometric representation, which tracks depth values only in high-gradient areas. The method has direct image alignment mechanisms and estimation based on the semi-dense depth map filtering technique [42]. The global depth map is rendered as a pose graph comprising keyframes represented as vertices that present feature 3D similarity transformations as edges, adding environment scaling ability and allowing accumulated drift to be detected and corrected. Furthermore, LSD-SLAM uses an appearance-based loop detection algorithm called FAB-MAP [43], which proposes prominent loop closure candidates that extract their features without reusing any additional visual odometry information. LSD-SLAM is publicly available in [44] and was implemented in Ubuntu 18.04 in its ROS version.

- DSO. DSO [18] is considered widely known as the gold standard of direct methods due to the impressive reconstruction and odometry results that it has achieved, and it has inspired and kept inspiring many implementations and new proposals. DSO works directly on pixel intensities information but applies a point selection strategy to reduce the amount of information to be processed efficiently. It continuously optimizes photometric error applied to the last N-frames while optimizes the complete likelihood for all the parameters involved in the model, including poses, intrinsics, extrinsics, and inverse depths, executing a windowed sparse bundle adjustment for this. DSO is publicly available for implementation in [45], and its code runs totally in C++ using minor requirements like Suitesparse, Eigen3, and Pangolin.

- SVO. We selected the most commonly known method, SVO [9], for the hybrid classification. SVO efficiently combines the advantages of direct and indirect approaches by using feature correspondences obtained on direct motion estimation for tracking and mapping. This procedure considerably reduces the number of required features and is only executed when a new keyframe is selected to insert new points in the map. First, camera motion is estimated by a sparse model-based image alignment algorithm, where sparse point features are used to estimate feature correspondences. Next, this information is used to minimize the photometric error. Then reprojected points, pose, and structure are refined by minimizing the reprojection error. SVO is publicly available in [46] for testing and implementation and runs on C++ or ROS. Modern operating systems might find issues during implementation, so Ubuntu 16.04 and ROS kinetic were used for its implementation.

- LDSO. As an additional sparse direct system, we selected LDSO [47], an update of the DSO algorithm that includes loop closure capabilities. LDSO enables the DSO framework to detect loop closure by ensuring point repeatability using corner features to detect loop candidates. For this purpose, the depth estimates for those point features allow the algorithm to compute Sim(3) constraints, to be combined with pose-only bundle adjustment and point cloud alignment to be fused with the relative pose co-visibility graph of the DSO sliding window optimization stage. This way, LDSO adds loop closure to the DSO system, including a loop closure module based on a global pose graph optimization that works over the last 5 to 7 keyframes sliding window. LDSO was made publicly available in [48], and for this comparison, it was implemented in Ubuntu 18.04 along with OpenCV 2.4.3, Sophus, DBoW3, and g2o.

- DSM. Another sparse-direct method we were interested in testing was DSM [49], another update made over DSO to create a complete SLAM system. DSM aimed to include scene reobservation information to enhance precision and reduce drift and inconsistencies. In contrast to LDSO, which considers a sparse set of reobservations, DSM builds a persistent map that allows the algorithm to reuse existing information by a photometric formulation. DSM uses local map co-visibility window criteria to detect the active keyframes reobserving the same region, a coarse-to-fine strategy to process that point reobservation information, and a robust nonlinear photometric bundle adjustment technique based on photometric error for outlier detection. DSM open-source code is publicly available in [50], and it was implemented for comparisons on Ubuntu 18.04 with Eigen (v3.1.0), OpenCV (v2.4.3), and the Ceres solver provided in its official repository.

- DynaSLAM. Dyna-SLAM algorithm [51] was made over a lighter version of ORB-SLAM2 and was improved by adding ML capabilities for detection, segmentation, and inpainting of dynamic information on scenes. In addition, the Mask R-CNN of [52] was integrated with the classic sparse-indirect method to detect and segment regions of each image that potentially belong to movable objects. The authors also incorporated a multi-view geometry approach that calculates back-projections of each key point to compute parallax angles, which are then used to detect additional dynamic information that the CNN cannot recognize. Authors reported that this combination contributes to overcoming initialization issues of ORB-SLAM2 and allows it to work in dynamic environments. DynaSLAM is publicly available in [14], and it was implemented in Ubuntu 16.04 with ROS Kinetic, Cuda 9, Tensorflow 1.4.0, and Keras 2.0.8.

- CNN-DSO. In the literature can be found neuronal versions of the DSO method like D3VO [53], MonoRec [11], and DDSO [54]. Nevertheless, they are not publicly available, or in the case of MonoRec, its monocular VO pipeline is not available for testing, so we chose CNN-DSO for this comparison which is publicly available in [12]. This method includes a CNN depth prediction module that enables the DSO system to execute its estimation modules using additional depth prior information obtained by the network. The CNN used for this study was the MonoDepth system of [55], a single image depth estimation network that outputs a depth value for each pixel position by chains of feature maps processing. The network was built over the ResNet backbone using a variant of its encoder-decoder architecture. CNN-DSO requires building TensorFlow (v1.6.0) from source and MonoDepth from its official repository [56], and it was implemented in Ubuntu 18.04 with Eigen (v3.1.0), OpenCV (v2.4.3).

- CNN-SVO. In the study of [8], an extension of the hybrid method SVO was proposed by fusing the same Single Image Depth Estimation (SIDE) CNN MonoDepth module used in CNN-DSO with the original geometric-based hybrid method. In this case, MonoDepth was included to add preliminary depth information to the SVO pipeline to reduce uncertainty in the feature correspondence identification steps. In this way, the system is initialized, obtaining maps with high uncertainty. Then the SIDE CNN creates filters to approximate the mean and variance of the current values, considerably reducing the amount of information separating inliers and outliers for the depth map. CNN-SVO is publicly available in [26], and it was implemented in Ubuntu 16.04 to allow SVO modules to work with ROS Kinetic.

2.3. Benchmarks

- KITTI. The KITT dataset of [59] contains 21 video sequences of a driving car, where the movement parameters are limited to forward driving. The available images have pre-rectification treatments, and the data set provides a ground truth obtained through an assembly of GPS and INS.

- EUROC-MAV. The EUROC-MAV dataset of [60] contains 11 inertial stereoscopic sequences of a quadcopter flying in different indoor environments. The data set also provides the ground truth values of all frames and calibration parameters.

- TUM-Mono. The TUM-Mono dataset of [3] presents 50 sequences of indoor and outdoor environments obtained using monocular RBG cameras on monochrome uEye UI-3241LE-M-GL cameras equipped with Lensagon BM2420 (with 148˚ × 122˚ field of view) and Lensagon BM4018S118 (with 98˚ × 79˚ field of view) sensors. This benchmark includes the photometric calibration parameters of each camera, the ground truth, the timestamps for the execution of each image sequence, and the calibration file for the vignetting effect for each sequence. This dataset comprises more than 190,000 frames and more than 100 minutes of video.

- ICL-NUIM. The ICL-NUIM benchmark of [5] has eight sequences in conjunction with its ray-tracing of 2 environments. It provides the ground truth values of each sequence and the intrinsics of the cameras, and no photometric calibration is required. This data set presents degenerative and purely rotational motion sequences that are usually especially demanding for monocular algorithms.

2.4. Metrics

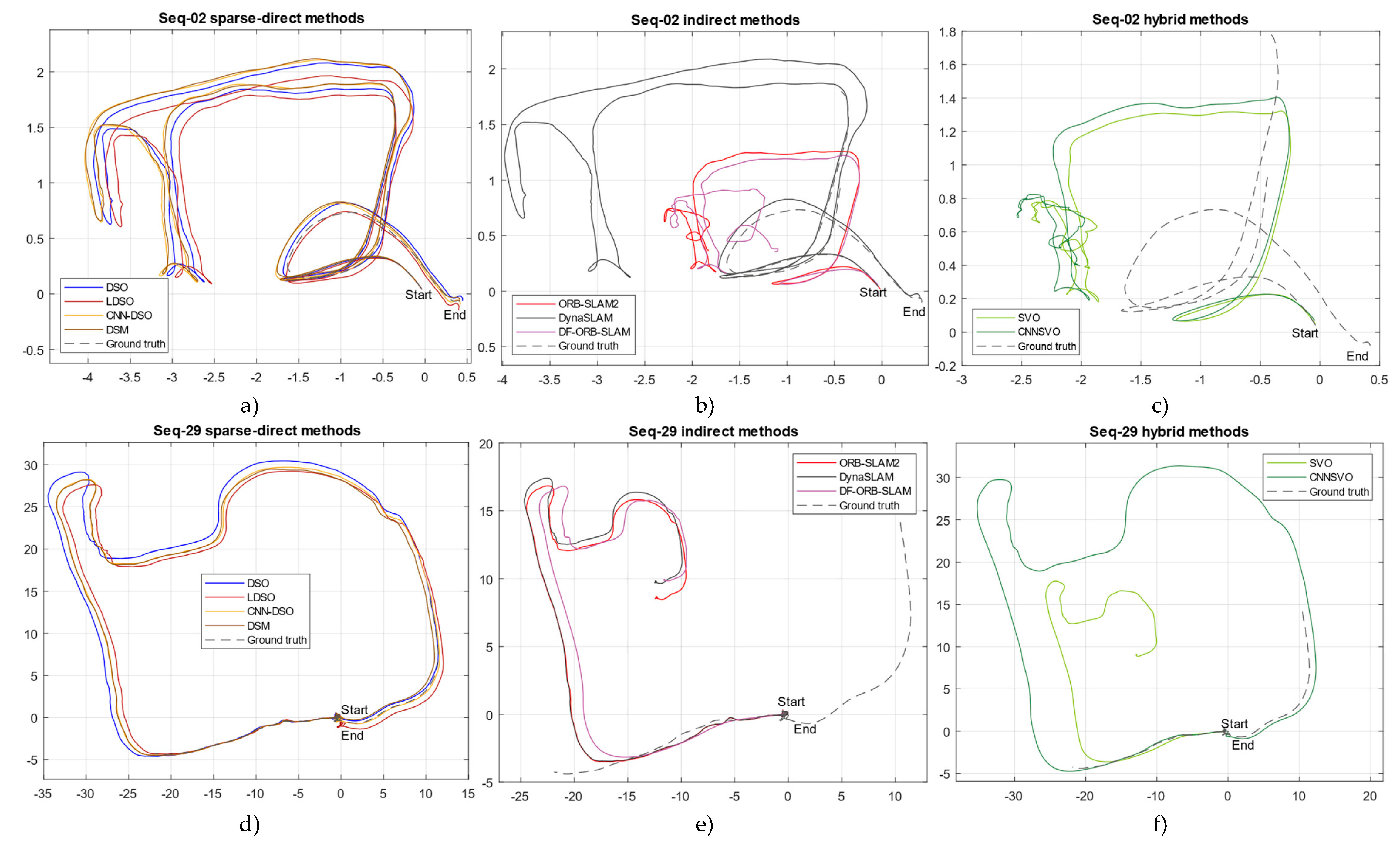

3. Results

3.1. Hardware Setup

3.2. Comparative analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. O. A. Aqel, M. H. Marhaban, M. I. Saripan, and N. B. Ismail, “Review of visual odometry: types, approaches, challenges, and applications,” SpringerPlus 2016 51, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–26, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Zollhöfer et al., “State of the Art on Monocular 3D Face Reconstruction, Tracking, and Applications,” Comput. Graph. Forum, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 523–550, 18. [CrossRef]

- J. Engel, V. Usenko, and D. Cremers, “A Photometrically Calibrated Benchmark For Monocular Visual Odometry,” Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Macario Barros, M. Michel, Y. Moline, G. Corre, and F. Carrel, “A Comprehensive Survey of Visual SLAM Algorithms,” Robotics, vol. 11, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Handa, T. Whelan, J. McDonald, and A. J. Davison, “A benchmark for RGB-D visual odometry, 3D reconstruction and SLAM,” in 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2014, pp. 1524–1531.

- E. P. Herrera-Granda, “An Extended Taxonomy for Monocular Visual SLAM, Visual Odometry, and Structure from Motion methods applied to 3D Reconstruction,” GitHub repository, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/erickherreraresearch/TaxonomyPureVisualMonocularSLAM/.

- K. Tateno, F. Tombari, I. Laina, and N. Navab, “CNN-SLAM: Real-time dense monocular SLAM with learned depth prediction,” in Proceedings - 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, 2017, vol. 2017-Janua, pp. 6565–6574.

- S. Y. Loo, A. J. Amiri, S. Mashohor, S. H. Tang, and H. Zhang, “CNN-SVO: Improving the mapping in semi-direct visual odometry using single-image depth prediction,” Proc. - IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom., vol. 2019-May, pp. 5218–5223, May 2019.

- C. Forster, Z. Zhang, M. Gassner, M. Werlberger, and D. Scaramuzza, “SVO: Semidirect Visual Odometry for Monocular and Multicamera Systems,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 249–265, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Forster, M. Pizzoli, and D. Scaramuzza, “SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry,” Proc. - IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom., pp. 15–22, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Wimbauer, N. Yang, L. von Stumberg, N. Zeller, and D. Cremers, “MonoRec: Semi-Supervised Dense Reconstruction in Dynamic Environments from a Single Moving Camera,” in 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2021, pp. 6108–6118.

- Muskie, “CNN-DSO: A combination of Direct Sparse Odometry and CNN Depth Prediction,” GitHub repository, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/muskie82/CNN-DSO.

- S. Wang, “DF-ORB-SLAM,” GitHub repository, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/834810269/DF-ORB-SLAM.

- B. Bescos, “DynaSLAM,” GitHub repository, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/BertaBescos/DynaSLAM.

- J. Sun, Y. Wang, and Y. Shen, “Fully Scaled Monocular Direct Sparse Odometry with A Distance Constraint,” 2019 5th Int. Conf. Control. Autom. Robot. ICCAR 2019, pp. 271–275, Apr. 2019.

- A. Sundar, “CNN-SLAM,” GitHub repository, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/iitmcvg/CNN_SLAM.

- C. Tang and P. Tan, “BA-Net: Dense Bundle Adjustment Network,” 7th Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. ICLR 2019, Jun. 2019.

- J. Engel, V. Koltun, and D. Cremers, “Direct Sparse Odometry,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 611–625, Mar. 2017.

- N. Yang, R. Wang, X. Gao, and D. Cremers, “Challenges in Monocular Visual Odometry: Photometric Calibration, Motion Bias, and Rolling Shutter Effect,” IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 2878–2885, 2018.

- E. Mingachev, R. Lavrenov, E. Magid, and M. Svinin, “Comparative analysis of monocular slam algorithms using tum and euroc benchmarks,” in Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, 2021, vol. 187, pp. 343–355. [CrossRef]

- E. Mingachev et al., “Comparison of ROS-Based Monocular Visual SLAM Methods: DSO, LDSO, ORB-SLAM2 and DynaSLAM,” in Interactive Collaborative Robotics, 2020, pp. 222–233. [CrossRef]

- M. Servières, V. Renaudin, A. Dupuis, and N. Antigny, “Visual and Visual-Inertial SLAM: State of the Art, Classification, and Experimental Benchmarking,” J. Sensors, vol. 2021, p. 2054828, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, “DVSO: Deep Virtual Stereo Odometry,” GitHub repository, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/SenZHANG-GitHub/dvso.

- R. Cheng, “CNN-DVO,” McGill repository. McGill, 2020.

- F. Wimbauer and N. Yang, “MonoRec,” GitHub repository, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/Brummi/MonoRec.

- S. Y. Loo, “CNN-SVO,” GitHub repository, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/yan99033/CNN-SVO.

- A. Steenbeek, “Sparse-to-Dense: Depth Prediction from Sparse Depth Samples and a Single Image,” GitHub repository, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/annesteenbeek/sparse-to-dense-ros.

- B. Ummenhofer, “DeMoN: Depth and Motion Network,” GitHub repository, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/lmb-freiburg/demon.

- Z. Teed and J. Deng, “DeepV2D,” GitHub repository, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/princeton-vl/DeepV2D.

- Z. Min, “VOLDOR: Visual Odometry from Log-logistic Dense Optical flow Residual,” GitHub repository, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/htkseason/VOLDOR.

- Z. Teed and J. Deng, “DROID-SLAM,” GitHub repository, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/princeton-vl/DROID-SLAM.

- H. Zhou, B. Ummenhofer, and T. Brox, “DeepTAM,” GitHub repository, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/lmb-freiburg/deeptam.

- S. Troscot, “CodeSLAM,” GitHub repository, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/silviutroscot/CodeSLAM.

- J. Czarnowski and M. Kaneko, “DeepFactors,” GitHub repository, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/jczarnowski/DeepFactors.

- R. Mur-Artal and J. D. Tardos, “ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 1255–1262, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Mur-Artal, J. M. M. Montiel, and J. D. Tardos, “ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 1147–1163, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Mur-Artal, “ORB-SLAM2,” GitHub repository, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/raulmur/ORB_SLAM2.

- L. Valgaerts, A. Bruhn, M. Mainberger, and J. Weickert, “Dense versus Sparse Approaches for Estimating the Fundamental Matrix,” Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2011 962, vol. 96, no. 2, pp. 212–234, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Ranftl, V. Vineet, Q. Chen, and V. Koltun, “Dense Monocular Depth Estimation in Complex Dynamic Scenes,” Proc. IEEE Comput. Soc. Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., vol. 2016-Decem, pp. 4058–4066, Dec. 2016.

- J. Engel, T. Schöps, and D. Cremers, “LSD-SLAM: Large-Scale Direct monocular SLAM,” in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2014, vol. 8690 LNCS, no. PART 2, pp. 834–849.

- H. Matsuki, L. von Stumberg, V. Usenko, J. Stückler, and D. Cremers, “Omnidirectional DSO: Direct Sparse Odometry With Fisheye Cameras,” IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 3693–3700, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Engel, J. Sturm, and D. Cremers, “Semi-dense visual odometry for a monocular camera,” in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2013, pp. 1449–1456.

- M. Cummins and P. Newman, “FAB-MAP: Probabilistic Localization and Mapping in the Space of Appearance:,” http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0278364908090961, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 647–665, Jun. 2008.

- J. Engel, “LSD-SLAM: Large-Scale Direct Monocular SLAM,” GitHub repository, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/tum-vision/lsd_slam.

- J. Engel, “DSO: Direct Sparse Odometry,” GitHub repository, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/JakobEngel/dso.

- C. Forster, “Semi-direct monocular visual odometry,” GitHub repository, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_svo.

- X. Gao, R. Wang, N. Demmel, and D. Cremers, “LDSO: Direct Sparse Odometry with Loop Closure,” IEEE Int. Conf. Intell. Robot. Syst., pp. 2198–2204, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Demmel, G. Xiang, and U. Erkam, “LDSO: Direct Sparse Odometry with Loop Closure,” GitHub repository, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/tum-vision/LDSO.

- J. Zubizarreta, I. Aguinaga, and J. M. M. Montiel, “Direct Sparse Mapping,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 1363–1370, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Zubizarreta, “DSM: Direct Sparse Mapping,” GitHub repository, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/jzubizarreta/dsm.

- B. Bescos, J. M. Fácil, J. Civera, and J. Neira, “DynaSLAM: Tracking, Mapping, and Inpainting in Dynamic Scenes,” IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 4076–4083, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. He, G. Gkioxari, P. Dollár, and R. Girshick, “Mask R-CNN,” in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2017, pp. 2980–2988.

- N. Yang, L. von Stumberg, R. Wang, and D. Cremers, “D3VO: Deep Depth, Deep Pose and Deep Uncertainty for Monocular Visual Odometry,” in 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020, pp. 1278–1289.

- C. Zhao, Y. Tang, Q. Sun, and A. V. Vasilakos, “Deep Direct Visual Odometry,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., 2021.

- C. Godard, O. Mac Aodha, and G. J. Brostow, “Unsupervised Monocular Depth Estimation with Left-Right Consistency.” 2017.

- S. Y. Loo, “MonoDepth CPP,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/yan99033/monodepth-cpp.

- M. Cordts et al., “The Cityscapes Dataset for Semantic Urban Scene Understanding,” in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 3213–3223.

- X. Huang et al., “The ApolloScape Dataset for Autonomous Driving,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 2018, pp. 1067–10676.

- A. Geiger, P. Lenz, and R. Urtasun, “Are we ready for autonomous driving? The KITTI vision benchmark suite,” in 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2012, pp. 3354–3361.

- M. Burri et al., “The EuRoC micro aerial vehicle datasets:,” https://doi.org/10.1177/0278364915620033, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 1157–1163, Jan. 2016.

- D. J. Butler, J. Wulff, G. B. Stanley, and M. J. Black, “A naturalistic open source movie for optical flow evaluation,” in European Conf. on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2012, pp. 611–625.

- A. R. Zamir, A. Sax, W. Shen, L. Guibas, J. Malik, and S. Savarese, “Taskonomy: Disentangling Task Transfer Learning,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 3712–3722.

- W. Yin, Y. Liu, and C. Shen, “Virtual Normal: Enforcing Geometric Constraints for Accurate and Robust Depth Prediction,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., p. 1, 2021.

- J. Cho, D. Min, Y. Kim, and K. Sohn, “A Large RGB-D Dataset for Semi-supervised Monocular Depth Estimation.” arXiv, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Xian et al., “Monocular Relative Depth Perception with Web Stereo Data Supervision,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 311–320.

- J. Sturm, N. Engelhard, F. Endres, W. Burgard, and D. Cremers, “A benchmark for the evaluation of RGB-D SLAM systems,” in 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2012, pp. 573–580.

- B. K. P. Horn, “Closed-form solution of absolute orientation using unit quaternions,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 629–642, Apr. 1987. [CrossRef]

- S. Sarabandi and F. Thomas, “Accurate Computation of Quaternions from Rotation Matrices,” in Advances in Robot Kinematics 2018, 2019, pp. 39–46.

- F. Devernay and O. Faugeras, “Straight lines have to be straight,” Mach. Vis. Appl., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 14–24, 2001. [CrossRef]

- R. Castle, “PTAM-GPL: Parallel Tracking and Mapping,” GitHub repository, 2013. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/Oxford-PTAM/PTAM-GPL.

- ROS.org, “ROS Camera Calibration,” 2020. [Online]. Available: http://wiki.ros.org/camera_calibration. [Accessed: 26-Dec-2022].

- Open Source Computer Vision.org, “Camera calibration with OpenCV,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://docs.opencv.org/4.1.1/d4/d94/tutorial_camera_calibration.html. [Accessed: 26-Dec-2022].

- H. Ghorbani, “MAHALANOBIS DISTANCE AND ITS APPLICATION FOR DETECTING MULTIVARIATE OUTLIERS,” FACTA Univ. Ser. Math. INFORMATICS, vol. 34, pp. 583–595, 2019.

- Z. Min and E. Dunn, “VOLDOR-SLAM: For the Times When Feature-Based or Direct Methods Are Not Good Enough,” CoRR, vol. abs/2104.0, 2021.

- Z. Teed and J. Deng, “DROID-SLAM: Deep Visual SLAM for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras.” arXiv, 2021.

- C. Yang, Q. Chen, Y. Yang, J. Zhang, M. Wu, and K. Mei, “SDF-SLAM: A Deep Learning Based Highly Accurate SLAM Using Monocular Camera Aiming at Indoor Map Reconstruction With Semantic and Depth Fusion,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 10259–10272, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhou, B. Ummenhofer, and T. Brox, “DeepTAM: Deep Tracking and Mapping with Convolutional Neural Networks,” Int. J. Comput. Vis., vol. 128, no. 3, pp. 756–769, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Laidlow, J. Czarnowski, and S. Leutenegger, “DeepFusion: Real-time dense 3D reconstruction for monocular SLAM using single-view depth and gradient predictions,” in Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2019, vol. 2019-May, pp. 4068–4074.

- M. Bloesch, J. Czarnowski, R. Clark, S. Leutenegger, and A. J. Davison, “CodeSLAM - Learning a Compact, Optimisable Representation for Dense Visual SLAM,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 2560–2568.

- J. Czarnowski, T. Laidlow, R. Clark, and A. J. Davison, “DeepFactors: Real-Time Probabilistic Dense Monocular SLAM,” IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 721–728, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Yang, R. Wang, J. Stückler, and D. Cremers, “Deep Virtual Stereo Odometry: Leveraging Deep Depth Prediction for Monocular Direct Sparse Odometry.” arXiv, 2018.

- A. Steenbeek and F. Nex, “CNN-Based Dense Monocular Visual SLAM for Real-Time UAV Exploration in Emergency Conditions,” Drones, vol. 6, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, W. Yin, E. Xie, Z. Li, C. Sun, and C. Shen, “Improving Monocular Visual Odometry Using Learned Depth,” IEEE Trans. Robot., pp. 1–14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Ummenhofer et al., “DeMoN: Depth and motion network for learning monocular stereo,” Proc. - 30th IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, vol. 2017-January, pp. 5622–5631, Nov. 2017.

- Z. Teed and J. Deng, “DeepV2D: Video to Depth with Differentiable Structure from Motion.” arXiv, 2020.

- C. Tang, “BA-Net: Dense Bundle Adjustment Network,” GitHub repository, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/frobelbest/BANet.

| Component | Specifications |

|---|---|

| CPU | AMD Ryzen™ 7 3800X, eight cores, 16 threads, 3.9 – 4.5 GHz. |

| GPU | NVIDIA GEFORCE GTX 1080 Ti. Pascal architecture, 1582 MHz, 3584 CUDA cores, 11 GB GDDR5X. |

| RAM | 16 GB, DDR 4, 3200 MHz |

| ROM | SSD NVME M.2 Western Digital 7300 MB/s |

| Power consumption | 750 W1 |

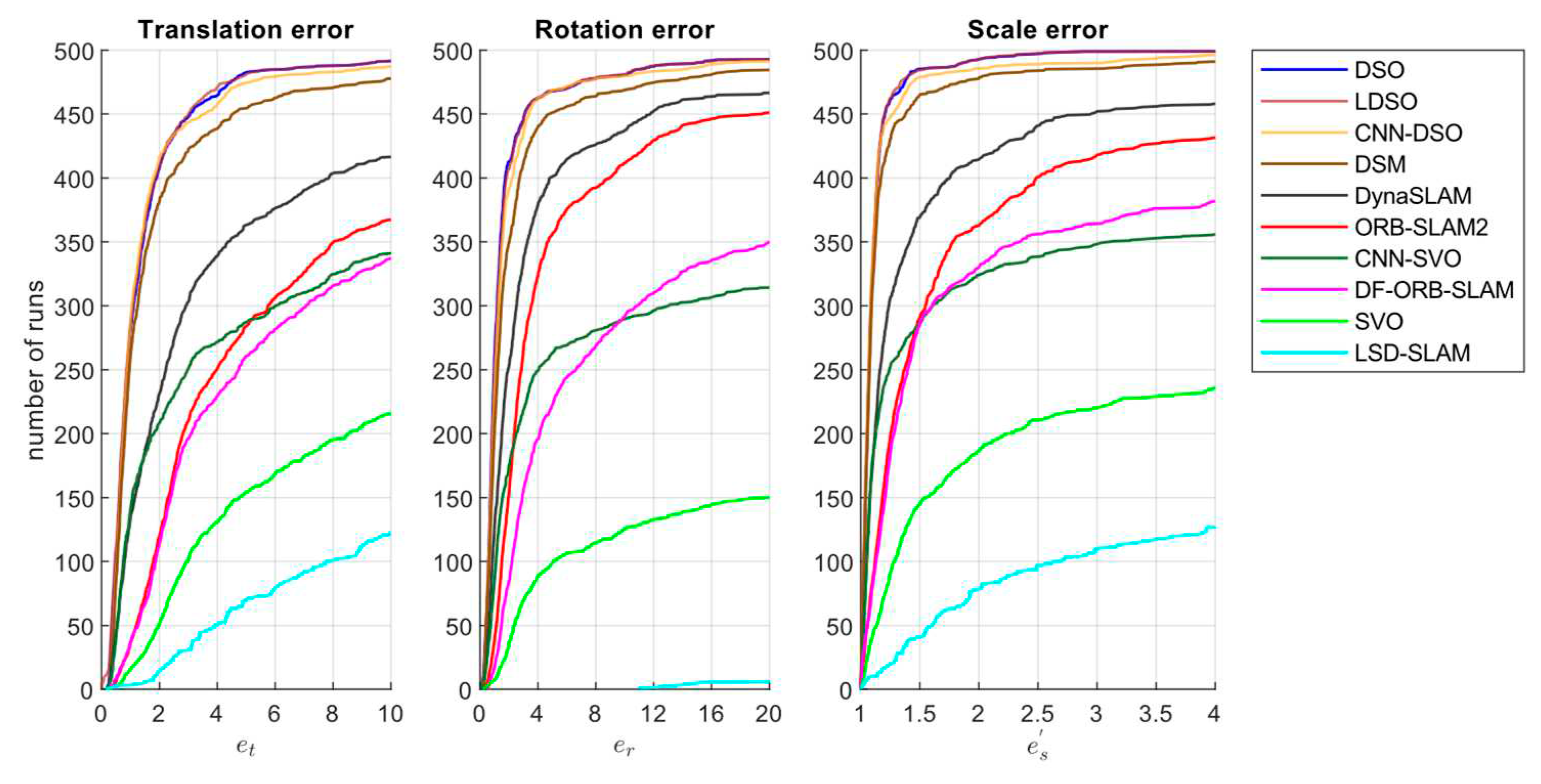

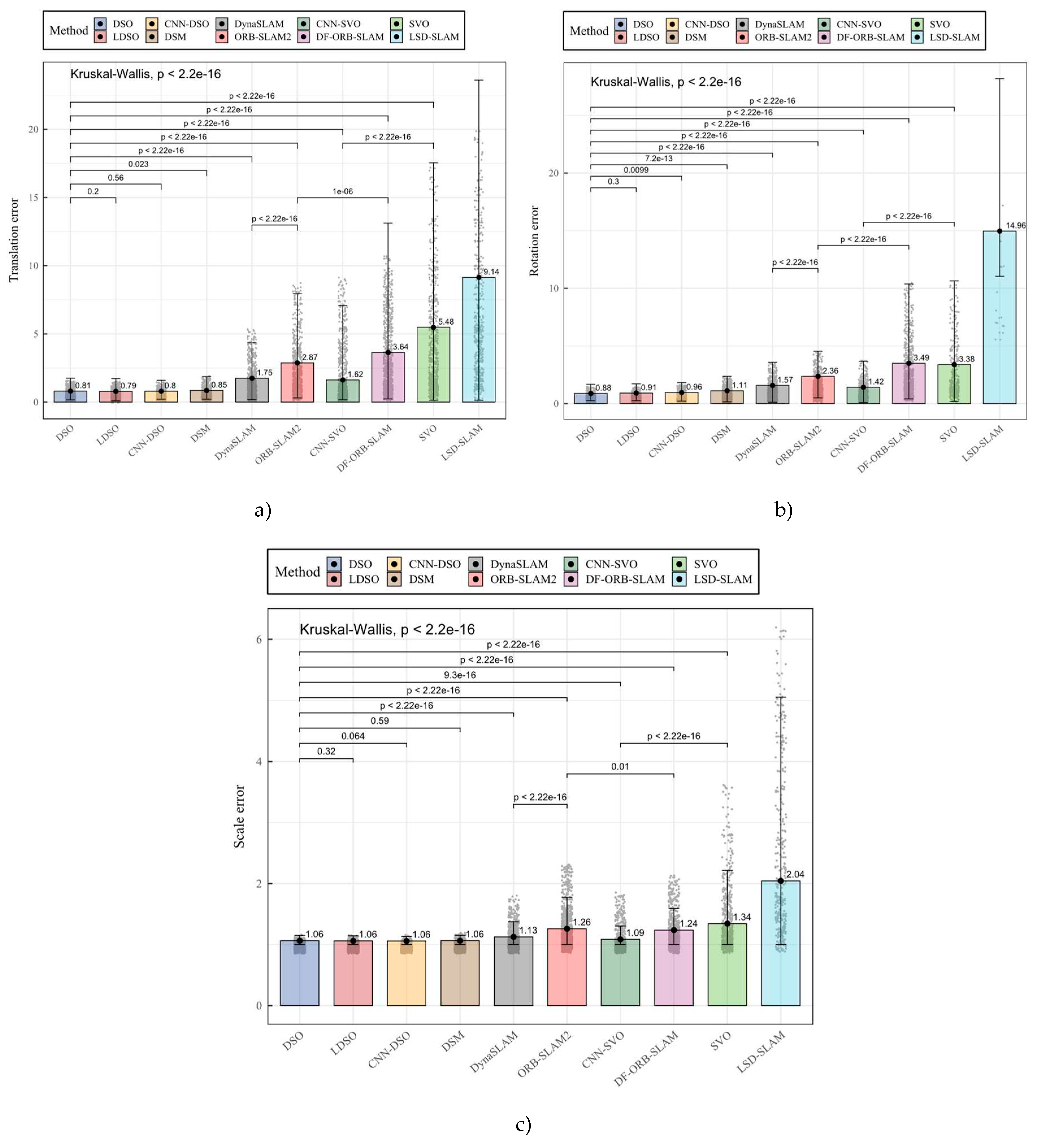

| Method | Translation error | Rotation error | Scale error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal-Wallis general test | |||

| DSO | 0.8064585a | 0.8800369b | 1.064086ab |

| LDSO | 0.7892125a | 0.9135608ab | 1.061302ab |

| CNN-DSO | 0.7980411a | 0.9618528a | 1.058849a |

| DSM | 0.8519143b | 1.1117710c | 1.064615b |

| DynaSLAM | 1.7473504c | 1.5730542d | 1.126499c |

| ORB-SLAM2 | 2.8738313d | 2.3585843e | 1.260155d |

| CNN-SVO | 1.6248001c | 1.4159545d | 1.086399e |

| DF-ORB-SLAM | 3.6423921e | 3.4940400f | 1.238232f |

| SVO | 5.4819407f | 3.3772024f | 1.343603g |

| LSD-SLAM | 9.1403348g | 14.9621188g | 2.044298h |

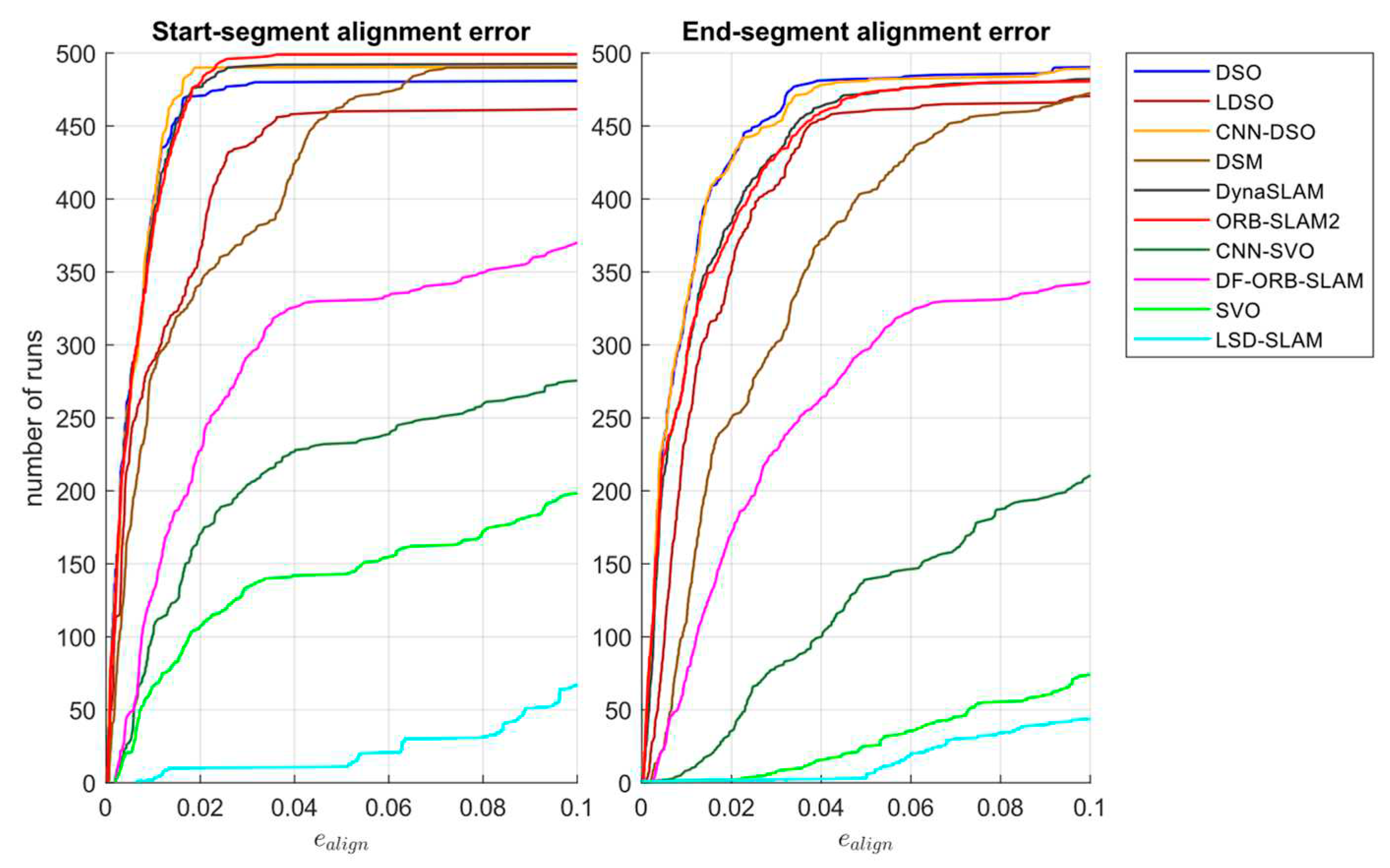

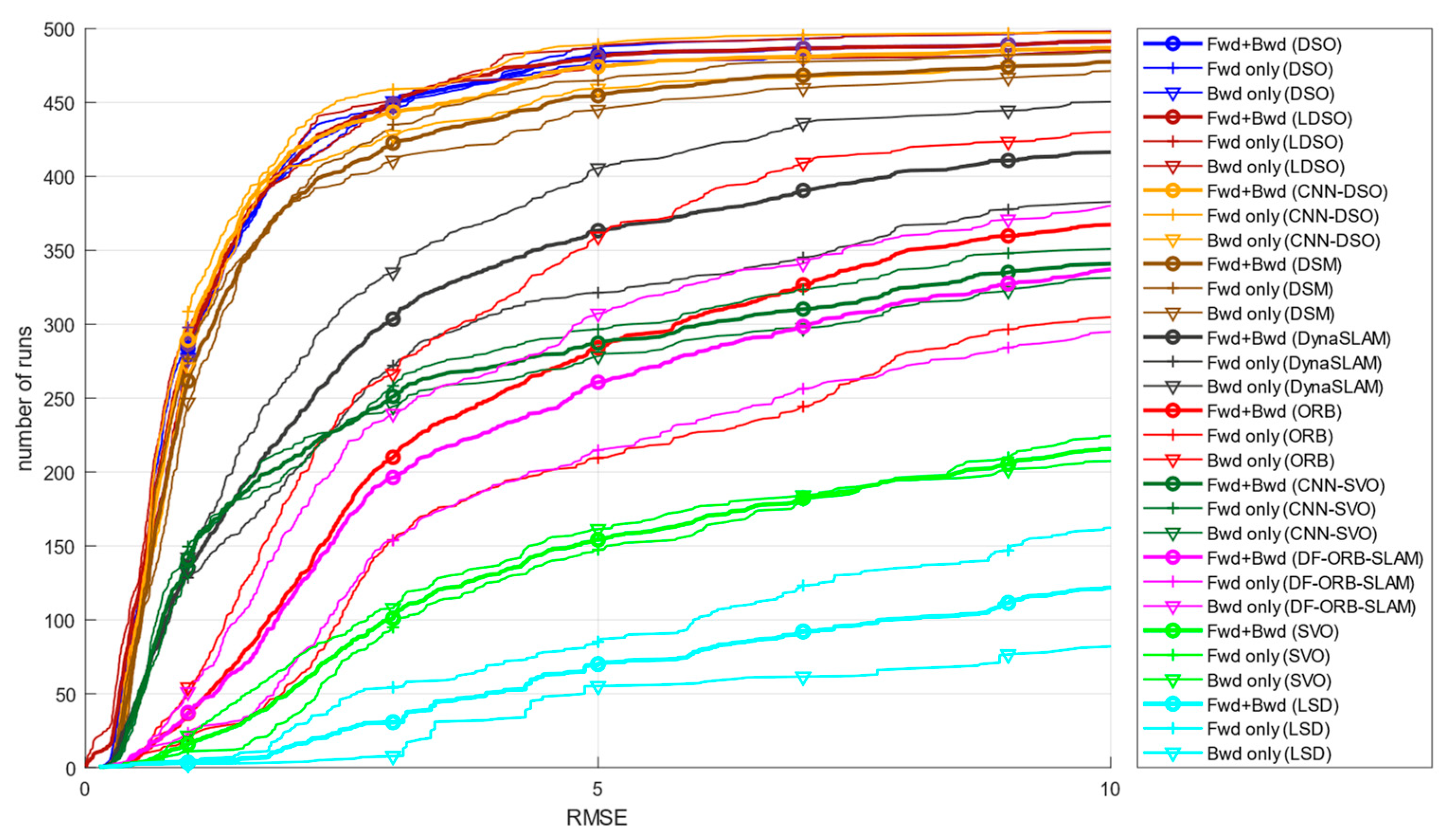

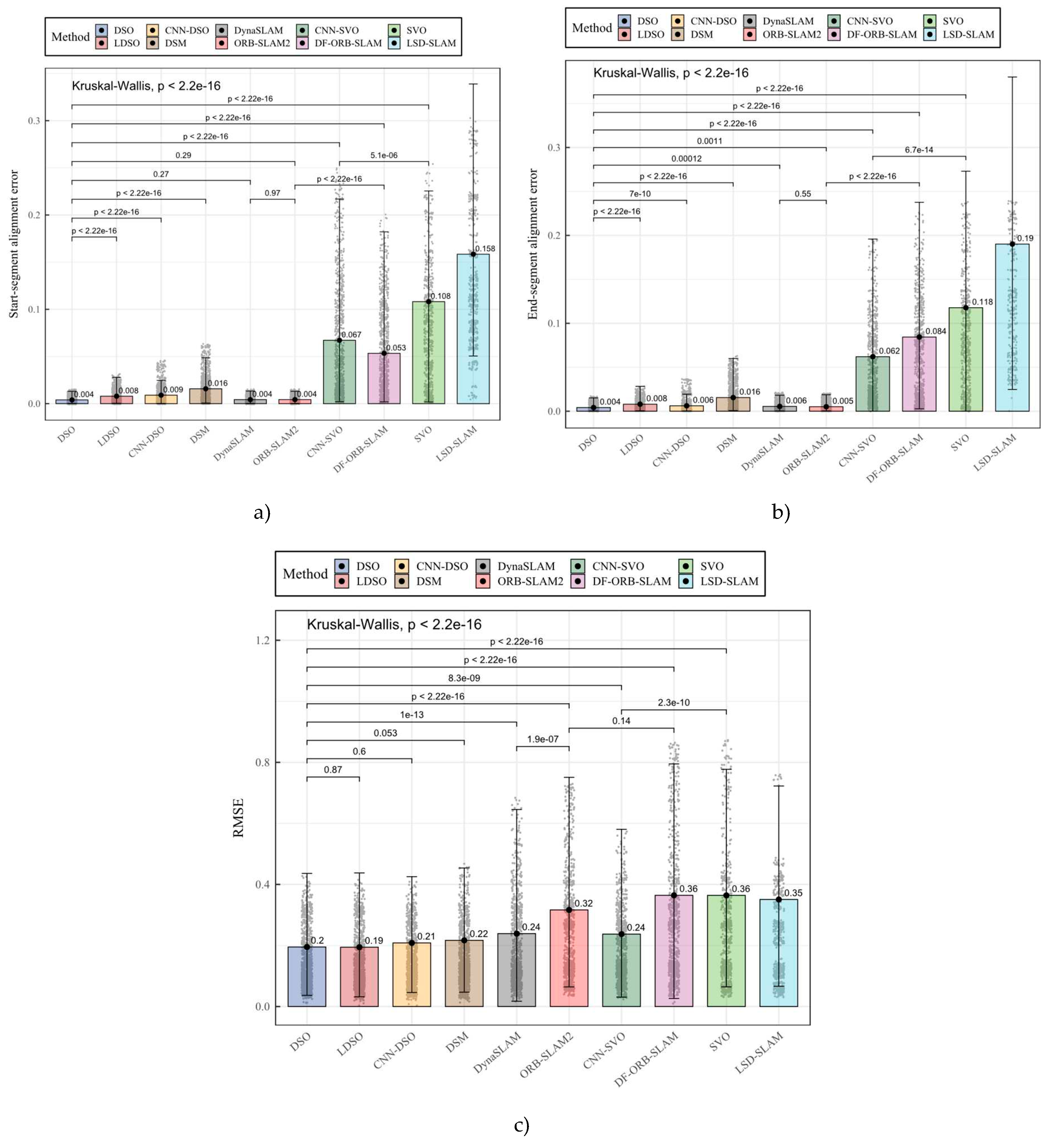

| Method | Start-segment alignment error |

End-segment alignment error |

RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal-Wallis general test | |||

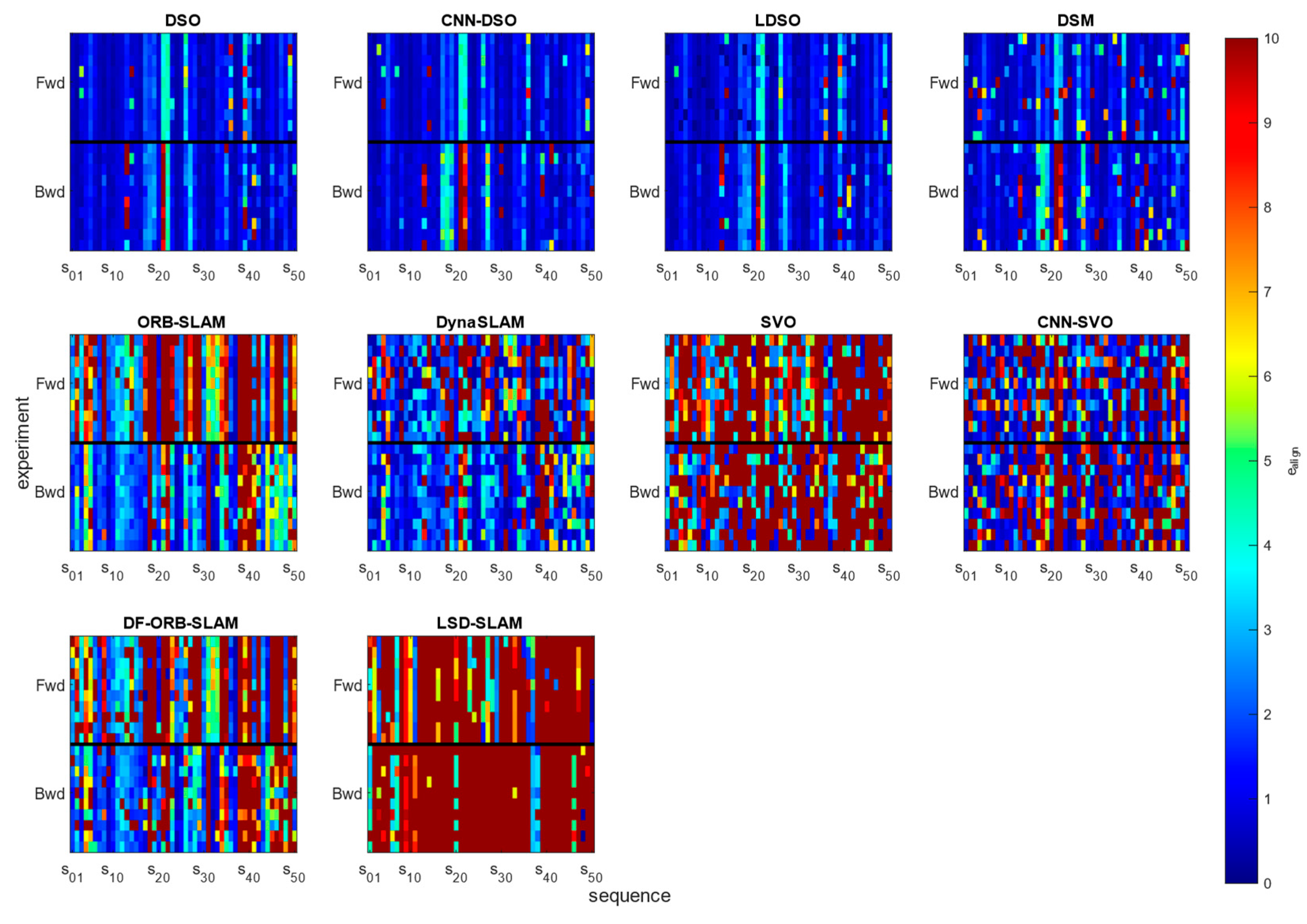

| DSO | 0.003974759a | 0.004184367a | 0.1950799ab |

| LDSO | 0.007925665b | 0.008009198b | 0.1944492a |

| CNN-DSO | 0.008987173b | 0.006199582c | 0.2083872ab |

| DSM | 0.015794222c | 0.015537213d | 0.2167750b |

| DynaSLAM | 0.004286919a | 0.005516179e | 0.2389837cd |

| ORB-SLAM2 | 0.004311949a | 0.005102672e | 0.3165024e |

| CNN-SVO | 0.067201999d | 0.062036008f | 0.2373532c |

| DF-ORB-SLAM | 0.053360456e | 0.084420570g | 0.3643844e |

| SVO | 0.108150349f | 0.117753996h | 0.3642558e |

| LSD-SLAM | 0.158469383g | 0.190127787i | 0.3507099d |

| Method. | Category | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORB-SLAM2 [35] | Classic-sparse-indirect | Low computational cost. Multiple input modalities. Easy to implement. Robustness to multiple environments. | Trajectory loss issues. Accumulates drift while relocalizing. Sparse 3D reconstruction. |

| DF-ORB-SLAM [13] | Classic-dense- indirect | Low computational cost. Reduces trajectory loss issues. | Introduces noise for trajectory estimation. Accumulates drift on relocalization. Sparse 3D reconstruction. Reduces the performance of ORB-SLAM2 significantly. |

| LSD-SLAM [40] | Classic-dense-direct | Low computational cost. More detailed 3D reconstruction, but with the presence of outliers. Includes more information in the final 3D reconstruction. | Poorest performance of the evaluated methods. Initialization issues. Trajectory loss issues. |

| DSO [18] | Classic-sparse-direct | Low computational cost. Easy to implement. More detailed and precise 3D reconstruction. Robust to multiple environments and motion patterns. Best performance of all methods in most of the metrics. | Requires specific complex camera calibration. Slightly but outperformed by LDSO in translation and RMSE metrics, but the differences were not significant. |

| SVO [10] | Classic-hybrid | Low computational cost. Good documentation and open-source availability for implementation in diverse configurations. | Frequent trajectory loss issues. Initialization issues. Critical execution errors due to the absence of a relocalization module. |

| LDSO [47] | Classic-sparse-direct | Low computational cost. Similar to DSO, detailed and precise 3D reconstruction. Easy to implement. Includes loop closure module. Slightly outperforms DSO in translation and rotation error, but the differences were not significant. Best performance in translation and RMSE metrics than DSO, but the differences weren’t significant. | Requires specific complex camera calibration. Performs significantly worse than DSO in the end-segment error metric. |

| DSM [49] | Classic-sparse-direct | Detailed and precise 3D reconstruction. Robust execution in most of the environments and motion patterns. Complete and interactive GUI. | Requires more computational capabilities than the rest of sparse-direct methods. Significatively underperformed most of the sparse-direct methods. |

| CNN-DSO [12] | ML-sparse-direct | Detailed and precise 3D reconstruction. Robust to multiple environments and motion patterns. Significant best performance in scale error metric. | Presence of outliers in the 3D reconstruction. Significatively outperformed in rotation error metric by DSO. Difficult to implement. Specific hardware is required. |

| DynaSLAM [51] | ML-sparse-indirect | Multiple input modalities. Easy to implement. Robustness to multiple environments. Detects, segments, and removes information of moving objects. Especially recommended for dynamic environments. Less trajectory loss issues than ORB-SLAM2. | Accumulates drift while relocalizing. Sparse 3D reconstruction. Increases complexity to ORB-SLAM2. Specific hardware is required. |

| CNN-SVO [8] | ML-hybrid | Considerably reduces trajectory loss issues of SVO. Initialization issues. Reduces the number of execution issues compared to SVO. Outperforms ORB-SLAM2 in the rotation, translation, scale, and RMSE metrics. Significantly outperforms its classic version in all the metrics. | Considerable presence of outliers in the 3D reconstruction. Imprecise and sparser 3D reconstruction. Complex implementation. Specific hardware is required. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).