Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Higher Power Density and Efficiency

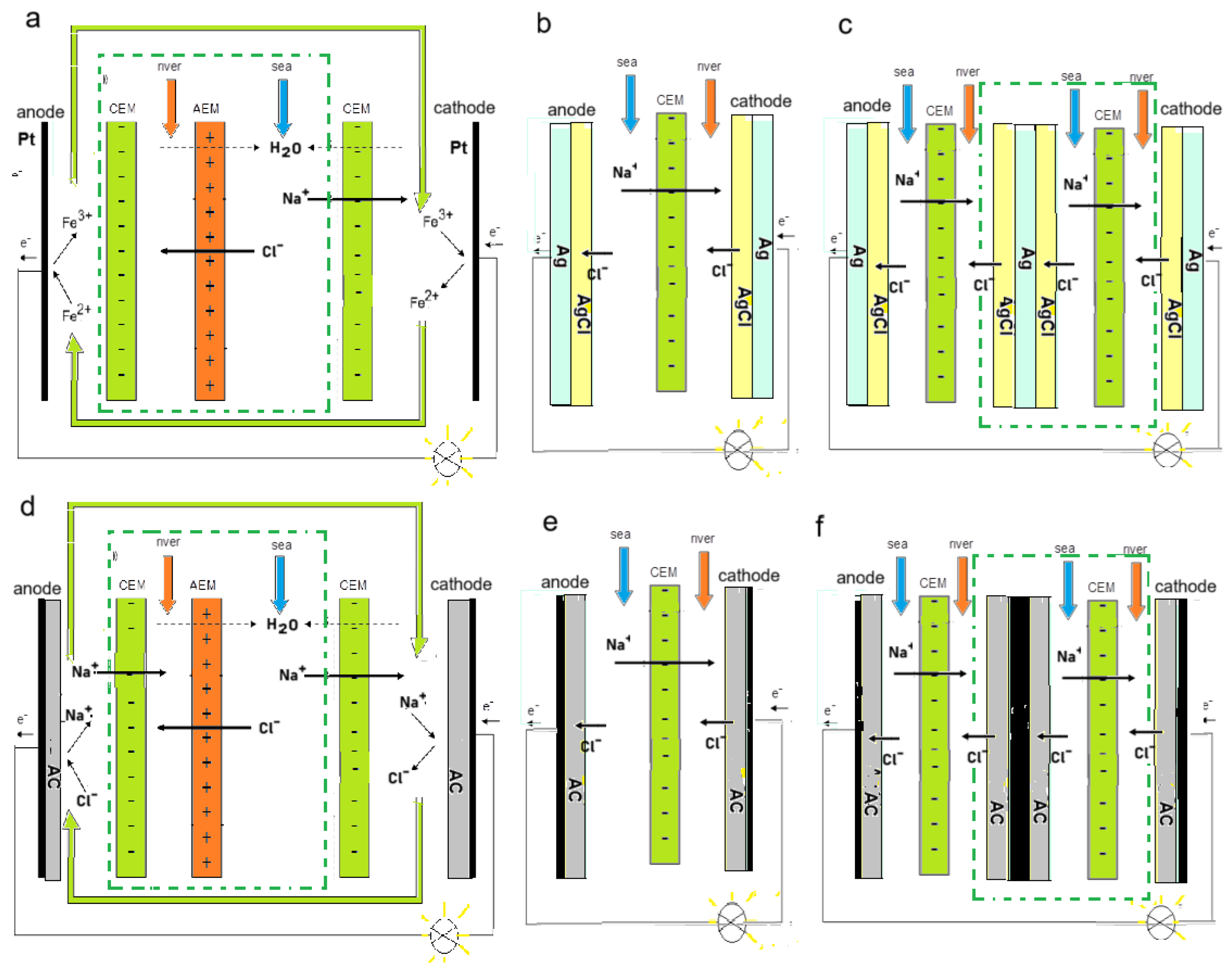

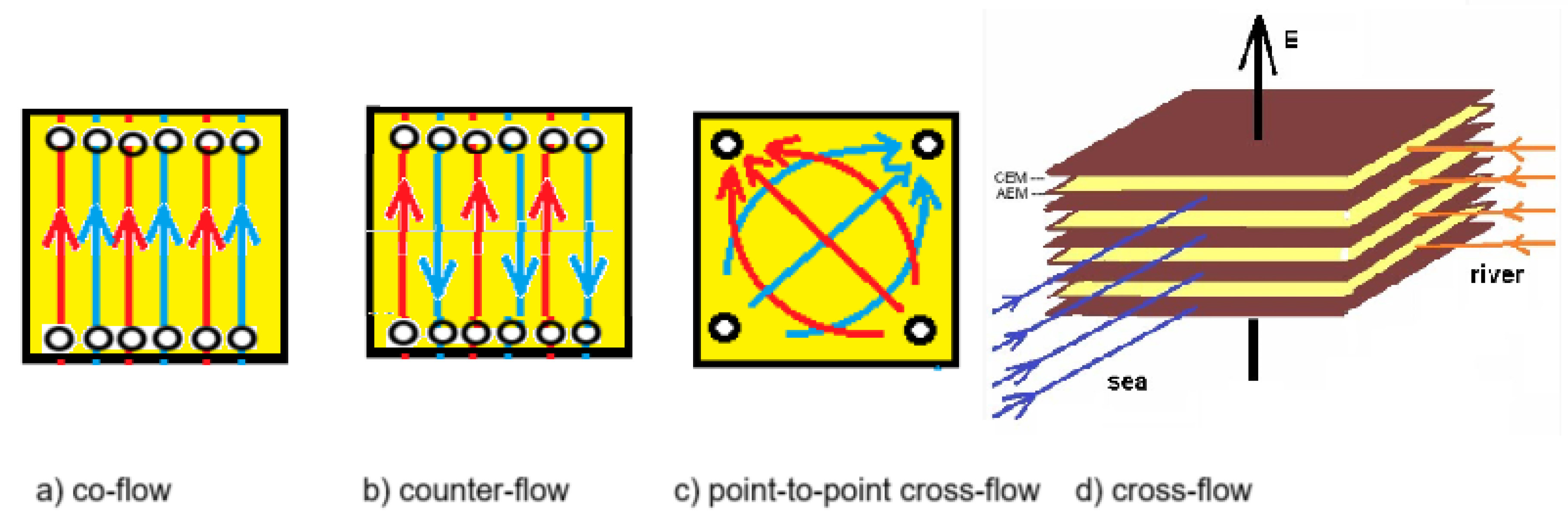

2.1. Stack Optimization

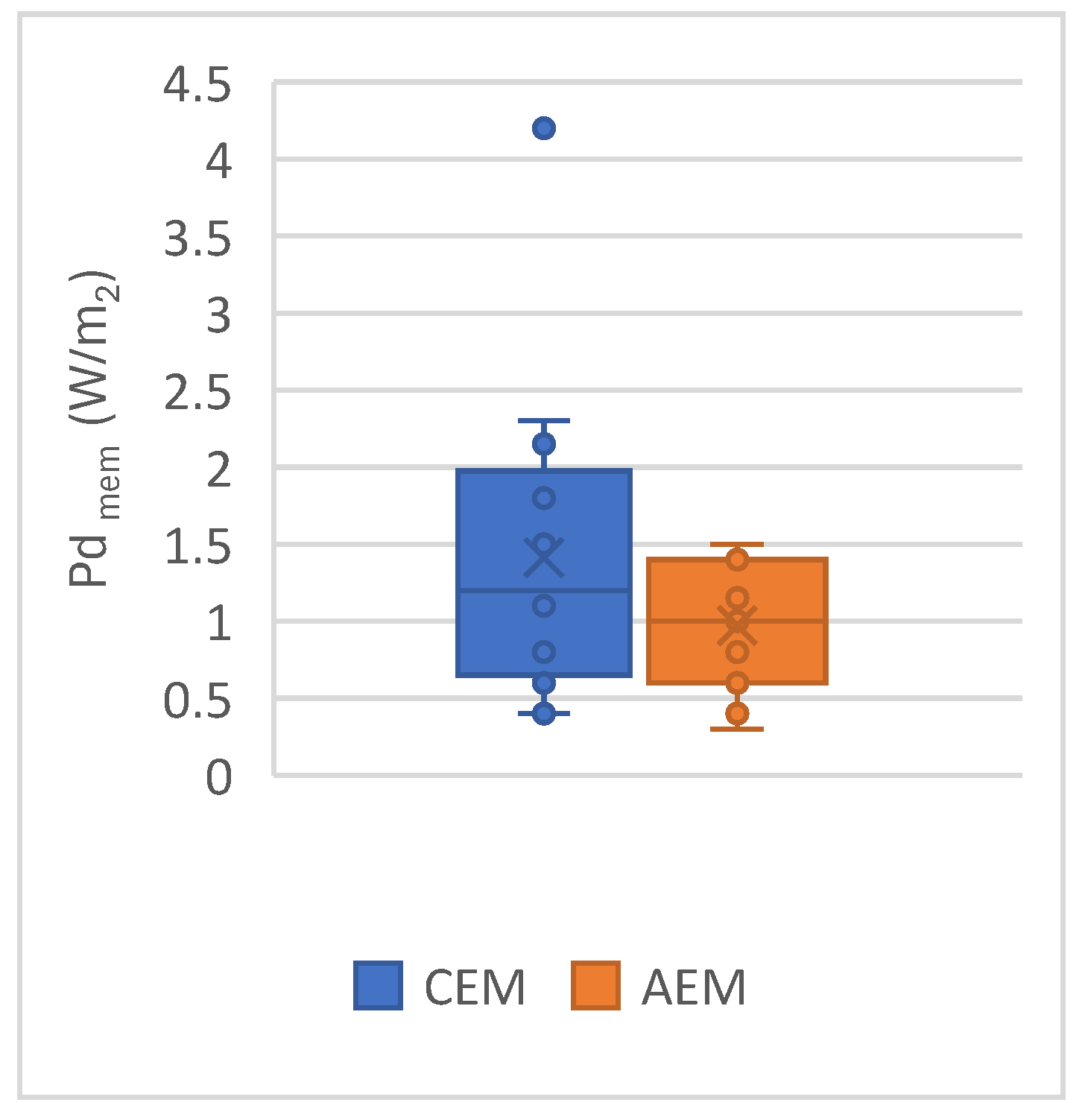

2.2. Classical Ion Exchange Membranes

2.3. New Membranes

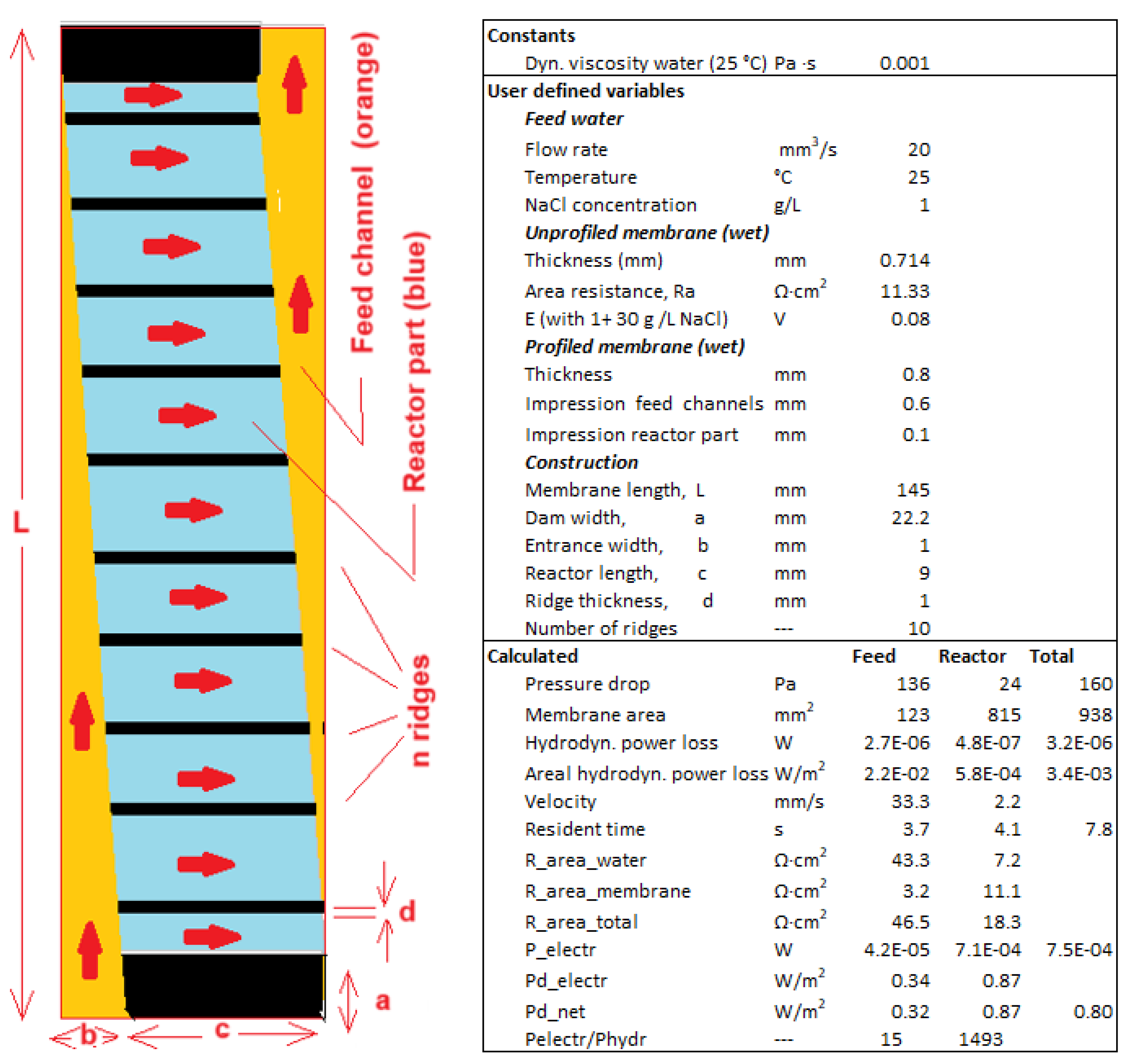

2.4. Profiled Membranes

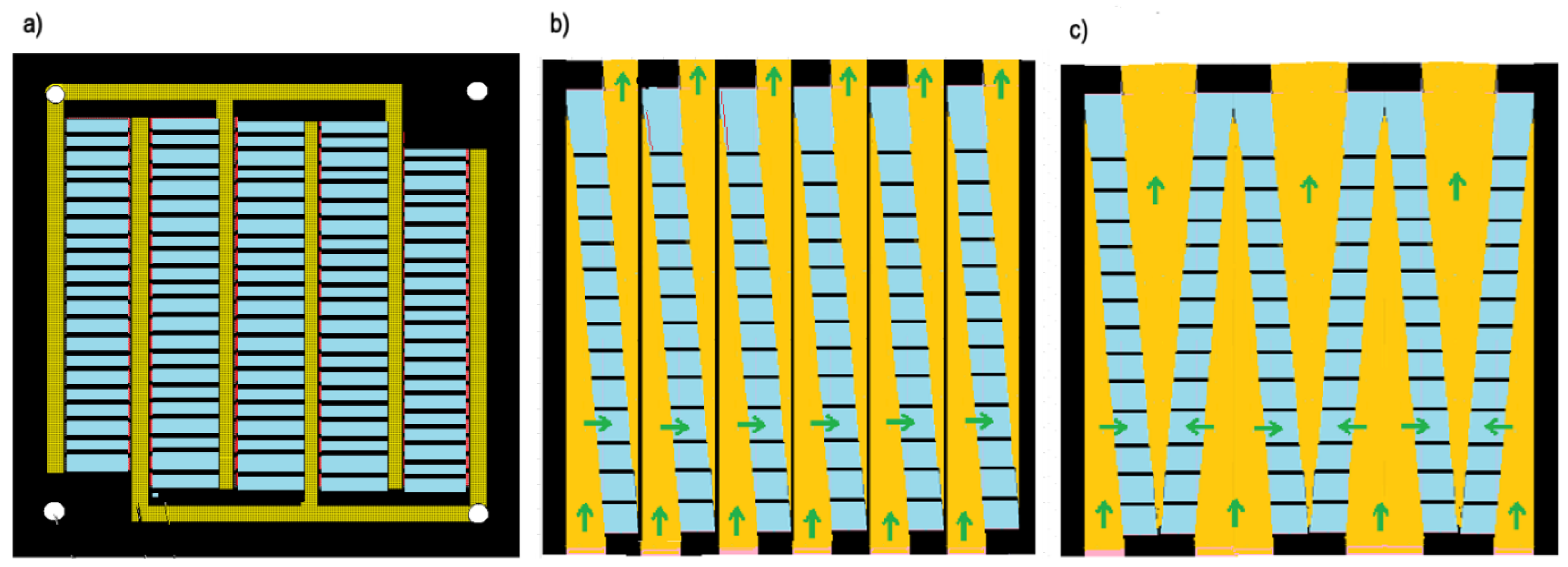

3. Fractal Design

3.1. Fractal Profiled Membranes

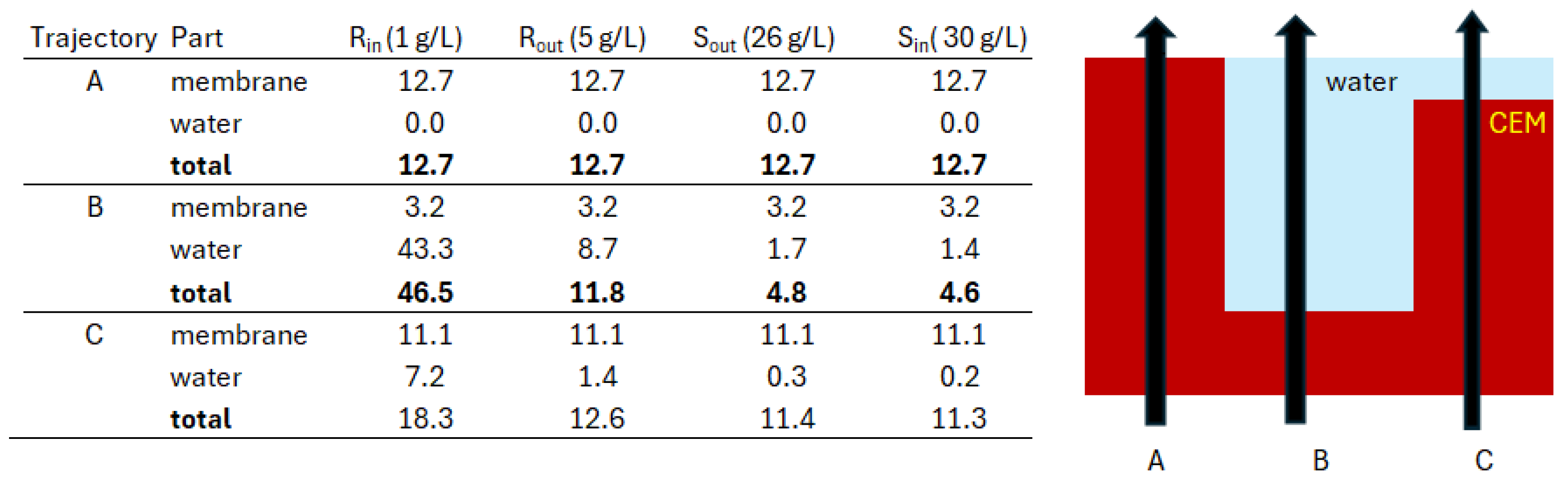

| Ralex membrane |

IEC | Perm-selectivity | Rarea | Swelling degree | Thickness dry |

Thickness wet |

| meq/g dry | % | Ω∙cm2 | % | μm | μm | |

| AMH-PES | 1.97 | 94.7 | 7.66 | 56 | 764 | |

| CMH-PES | 2.34 | 89.3 | 11.33 | 31 | 450 | 714 |

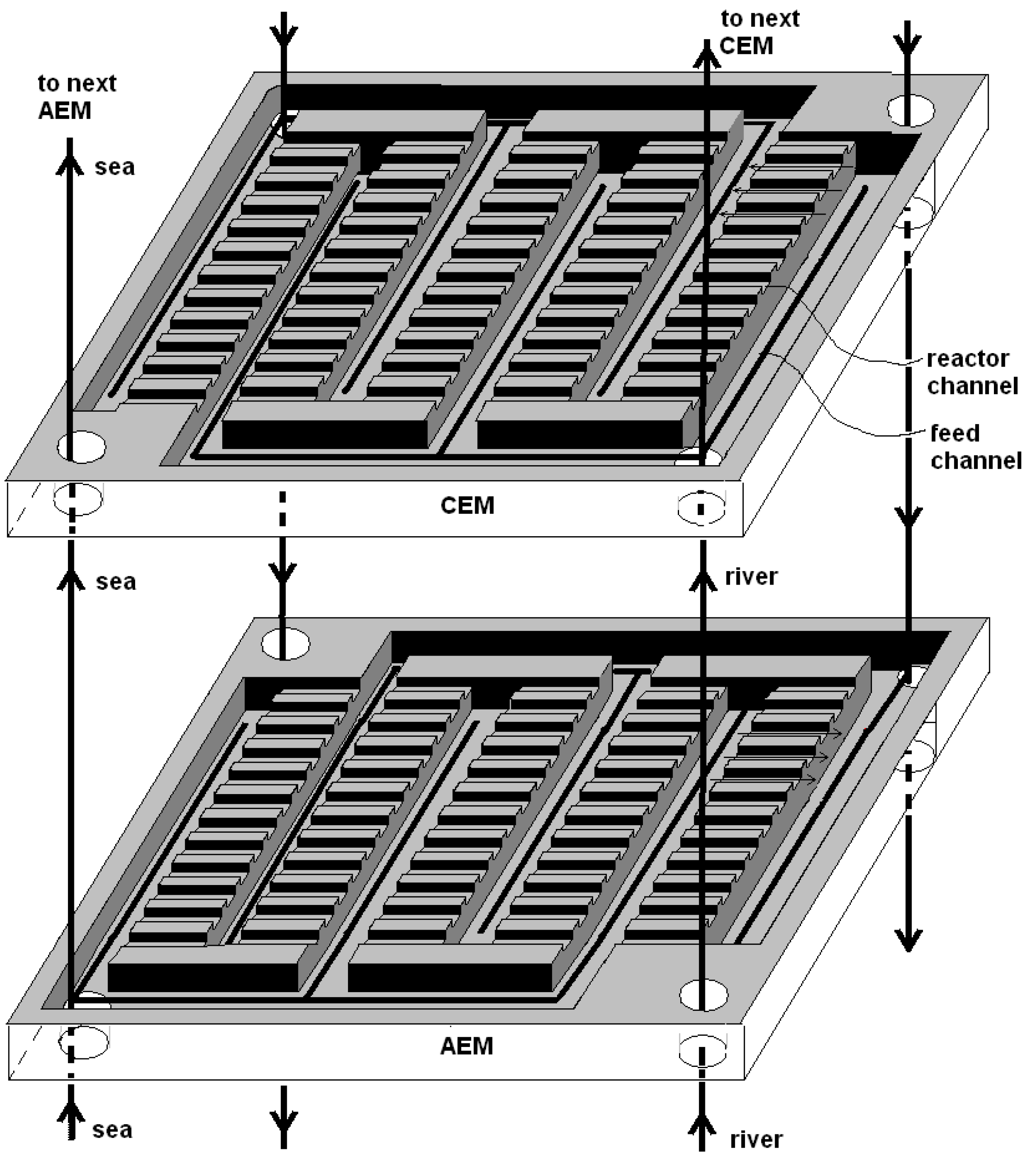

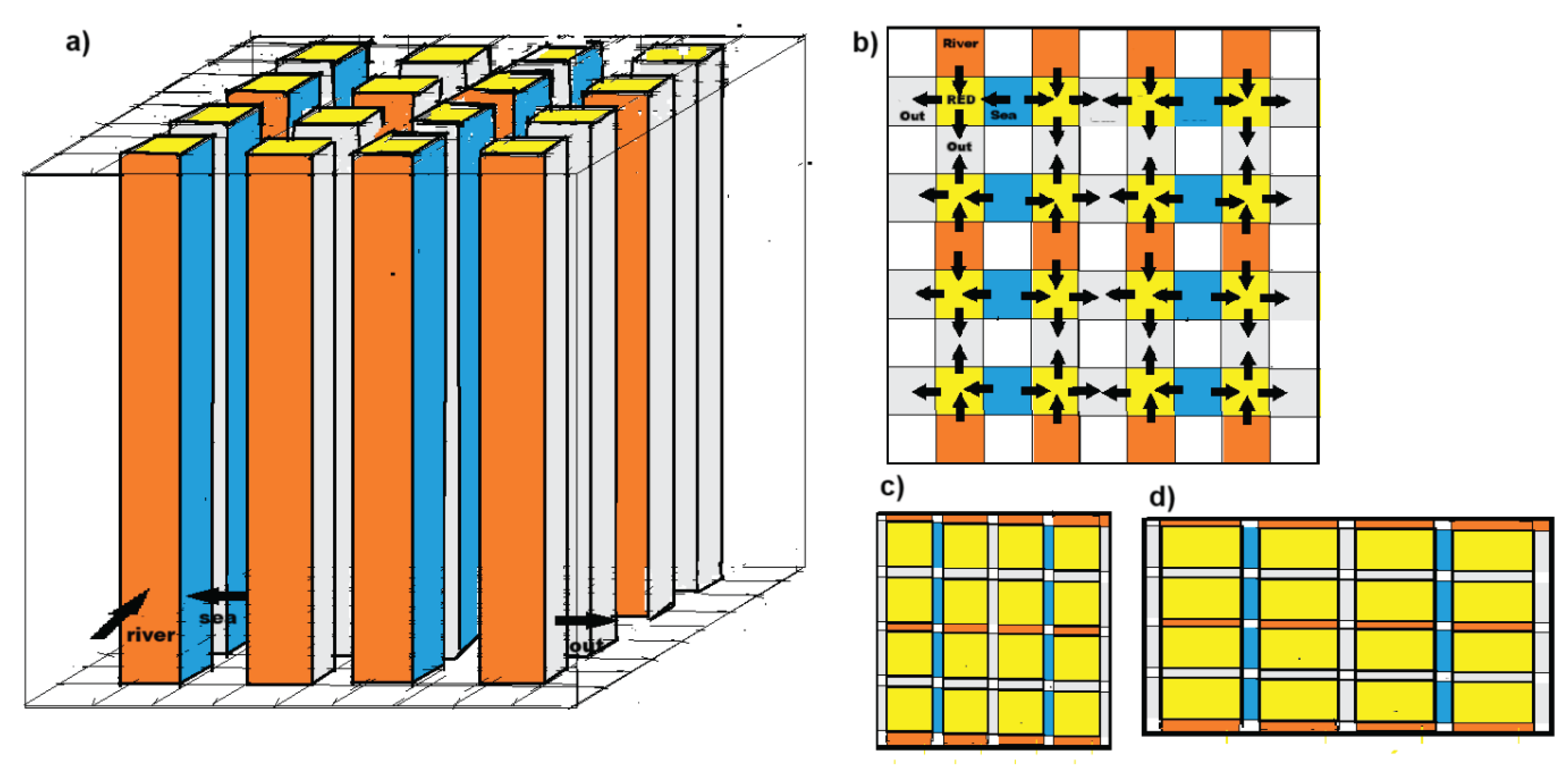

3.2. Fractal Stacks

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEM | anion exchange membrane |

| CEM | cation exchange membrane |

| CFD | computer fluid dynamics |

| cRED | capacitive RED |

| ED | electrodialysis |

| HC | high concentration feedwater |

| IEM | ion exchange membrane |

| LC | low concentration feedwater |

| OCF | overlapped cross filaments |

| RED | reverse electrodialysis |

| SEE | specific extractable energy |

| NPG | nanopore power generation |

References

- Veerman, J. Harvesting salinity gradient energy by diffusion of Ions, liquid water, and water vapor. Processes 2025, 13, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clampitt, B.H.; Kiviat, F.E. Energy recovery from saline water by means of electrochemical cells. Science 1976, 194, 719–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaas, D.A.; Bajracharya, S.; Sales, B.B.; Saakes, M.M. Clean energy generation using capacitive electrodes in reverse electrodialysis. Energy & Environmental Science 2013, 6, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Levant, M.; Brahmi, Y.; Tregouet, C.; Colin, A. Blue energy harvesting and divalent ions: Capacitive reverse electrodialysis cell with a single membrane opens a gateway to new application. Research Square 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, J.; Kunteng, D. Inorganic pseudo ion exchange membranes—Concepts and preliminary experiments. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, J. Reverse electrodialysis: co-and counterflow optimization of multistage configurations for maximum energy efficiency. Membranes 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, J.; Hack, P.; Siebers, R. Blue energy from salinity gradients. The Journal of Ocean Technology 2023, 18, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, A.G.; Wright, N.C. Spiral-wound electrodialysis module. Patent UA2019/0111393A1 (2019).

- Dow. Omexell, Spiral wound electrodeionization. Available online: https://www.lenntech.com/Data-sheets/DOW%20-EDI-210-L.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Derkenne, T.; Colin, A.; Tregouet, C. Macroscopic access resistances hinders the measurement of ion-exchange-membrane performances for electrodialysis processes. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2024, 7, 6621–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaas, D.A.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Doubled power density from salinity gradients at reduced intermembrane distance. Environmental Science & Technology 2011, 45, 7089–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaloc, J. Power numbers in grand tours—Vingegaard and Pogačar breaking records. Available online: https://www.welovecycling.com/wide/2023/08/30/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Veerman, J.; Saakes, M.; Metz, S.J.; Harmsen, G.J. Reverse electrodialysis: A validated process model for design and optimization. Chemical Engineering Journal 2011, 166, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, J. Reverse Electrodialysis—design and optimization by modeling and experimentation. Doctoral thesis University of Groningen (2010); https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/2625515/13complete.pdf.

- Abidin, M.N.Z.; Nasef, M.M.; Veerman, J. Towards the development of new generation of ion exchange membranes for reverse electrodialysis: A review. Desalination 2022, 537, 115854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-K.K.; Duan, C.; Chen, Y.-F.F.; Majumdar, A. Power generation from concentration gradient by reverse electrodialysis in ion-selective nanochannels. Microfluidics and Nanofluidics 2010, 9, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siria, A.; Poncharal, P.; Biance, A.-L.; Fulcrand, R.; Blase, X.; Purcell, S.T.; Bocquet, L. Giant osmotic energy conversion measured in a single transmembrane boron nitride nanotube. Nature 2013, 494, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Graf, M.; Liu, K.; Ovchinnikov, D.; Dumcenco, D.; Heiranian, M.; Nandigana, V.; Aluru, N.R.; Kis, A.; Radenovic, A. Single-layer MoS2 nanopores as nanopower generators. Nature 2016, 536, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikandan, D.; Karishma, S.; Kumar, M.; Nayak, P.K. Salinity gradient induced blue energy generation using two-dimensional membranes. npj 2D Materials and Applications 2024, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.R.; Wu, W. Emerging devices based on two-dimensional monolayer materials for energy harvesting. AAAS Research 2019, 2019, 7367828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Chu, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Hambsch, M.; Mannsfeld, S.C.; Borrelli, M.; Löffler, M.; Pohl, D.; Liu, Y. Giant blue energy harvesting in two-dimensional polymer membranes with spatially aligned charges. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2310791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, V.-P.; Fauziah, A.R.; Gu, C.-R.; Yang, Z.-J.; Wu, K.C.-W.; Yeh, L.-H.; Yang, R.-J. Two-dimensional metal–organic framework nanocomposite membranes with shortened ion pathways for enhanced salinity gradient power harvesting. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 484, 149649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.M.J.; Feng, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, M. Highly conductive anti-fouling anion exchange membranes for power generation by reverse electrodialysis. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 598, 234176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sun, X.; Ding, S.; Lu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, L. Charge-gradient sulfonated poly (ether ether ketone) membrane with enhanced ion selectivity for osmotic energy conversion. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 7161–7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, C.; Dou, H.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Y.; Xia, F. PET-hydrogel heterogeneous membranes that eliminate concentration polarization for salinity gradient power generation. Journal of Membrane Science 2024, 698, 122644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Yang, G.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, D.; Lei, W. Tunable surface charge of layered double hydroxide membranes enabling osmotic energy harvesting from anion transport. Small 2024, 20, 2400850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Meng, L.; Cao, L.; Zhang, D.; An, S.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; Pan, T.; Shen, J.; Chen, Z. Phase engineering of zirconium MOFs enables efficient osmotic energy conversion: structural evolution unveiled by direct imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2024, 146, 11855–11865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awati, A.; Yang, R.; Shi, T.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, H.; Lv, Y.; Liang, K.; Xie, L.; Zhu, D.; Liu, M. Interfacial super-assembly of vacancy engineered ultrathin-nanosheets toward nanochannels for smart ion transport and salinity gradient power conversion. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, 63, 202407491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wu, H. Dual-network fiber-hydrogel membrane for osmotic energy harvesting. Frontiers in Chemistry 2024, 12, 1401854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, J.; Jia, P.; Lu, W.; Yao, Q.; Deng, M.; Gao, Y.; Liu, N. Enhancing osmotic energy harvesting through supramolecular design of oxygen-functionalized MXene with biomimetic ion channel. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34, 2404410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shan, Z.; Ahmad, M.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z. Robust holey graphene oxide/cellulose nanofiber composites for sustainable and efficient osmotic energy conversion. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2024, 7, 4265–14274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, R.; Zeng, H.; Chen, X.; Yao, C.; Zhou, J.; Kong, X.-Y.W.L.; Jiang, L. Three-dimensional hydrogel membranes for boosting osmotic energy conversion: Spatial confinement and charge regulation induced by zirconium ion crosslinking. Nano Today 2024, 58, 102468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Xu, J.; Zhu, F.; Ding, Z.; Luo, Y. Different hydrophilic bilayer membranes for efficient osmotic energy harvesting with high-concentration exfoliation. Applied Clay Science 2024, 261, 107577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ma, W.; Zhou, J.; Wu, C.; Yao, C.; Zeng; Wang, J. A composite hydrogel with porous and homogeneous structure for efficient osmotic energy conversion. Chinese Chemical Letters 2024, 36, 110449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.-H.; Peng, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-K.; Chang, P.-Y.; Kang, D.-Y.; Yeh, L.-H. Crystal orientation control in angstrom-scale channel membranes for significantly enhanced blue energy harvesting. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 499, 155934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Jia, W.; Chang, L.; Ren, G.; Hu, S.; Sui, X.; Gao, L.; Sui, K.S.; Jiang, L. Anti-swelling 3D nanohydrogel for efficient osmotic energy conversion. Advanced Functional Materials 2025, 35, 2416425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Ling, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, D.; Li, K.; Wu, Y.; Xin, W.; Kong, X.-Y.; Jiang, L.; Wen, L. Turing-type nanochannel membranes with extrinsic ion transport pathways for high-efficiency osmotic energy harvesting. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wu, R.; Zeng, H.; Yao, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, G.; Wang, J. High-performance hydrogel membranes with superior environmental stability for harvesting osmotic energy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 499, 156681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Liu, X.; Cao, L.; Chen, C.; Chen, I.-C.; Li, Z.; Miao, J.; Lai, Z. Zeolite membrane with sub-nanofluidic channels for superior blue energy harvesting. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Patel, S.Z.; Lin, S.; Elimelech, M. Nanopore-based power generation from salinity gradient: why it is not viable. ACS nano 2021, 15, 4093–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, S.; Geraldes, V.; Crespo, J.G.; Velizarov, S. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) assisted analysis of profiled membranes performance in reverse electrodialysis. Journal of Membrane Science 2016, 502, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaas, D.A.; S. M.; Nijmeijer, K. Power generation using profiled membranes in reverse electrodialysis. Journal of membrane science 2011, 385, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, S.; Rijnaarts, T.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K.; Crespo, J.G.; Velizarov, S. Improved fluid mixing and power density in reverse electrodialysis stacks with chevron-profiled membranes. Journal of membrane science 2017, 531, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, E.; Elizen, R.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Micro-structured membranes for electricity generation by reverse electrodialysis. Journal of membrane science 2014, 458, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza, S.; Loza, N.; Kutenko, N.; Smyshlyaev, N. Profiled ion-exchange membranes for reverse and conventional electrodialysis. Membranes 2022, 12, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, S.; Crespo, J.G.; Velizarov, S. Profiled ion exchange membranes: A comprehensible review. International journal of molecular science 2019, 20, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Sugimoto, Y.; Higa, M. Power generation by reverse electrodialysis stack using profiled ion exchange membranes with novel concave-convex pattern. Salt and Seawater Science & Technology 2024, 4, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gurreri, L.; Santoro, F.; Battaglia, G.; Cipollina, A.; Tamburini, A.; Micale, G.; Ciofalo, M. Investigation of reverse electroDialysis units by multi-physical modelling. COMSOL Conference.

- Gurreri, L.; Battaglia, G.T.A.; Cipollina, A.; Micale; Ciofalo, M. Multi-physical modelling of reverse electrodialysis. Desalination 2017, 423, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cerva, M.F.; Di Liberto, M.; Gurreri, L.; Tamburini, A.; Cipollina, A.; Micale, G.; Ciofalo, M. Coupling CFD with a one-dimensional model to predict the performance of reverse electrodialysis stacks. Journal of Membrane Science 2017, 541, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofalo, M.; La Cerva, M.F.; Di Liberto, M.; Gurreri, L.; Cipollina, A.; Tamburini, A.; Micale, G. Coupling CFD with simplified 1-D models to predict the performance of reverse electrodialysis stacks. Submitted to Journal of Membrane Science, May 2017.

- Nikonenko, V.V.; Pismenskaya, N.D.; Istoshin, A.G.; Zabolotsky, V.I.; Shudrenko, A.A. Description of mass transfer characteristics of ED and EDI apparatuses by using the similarity theory and compartmentation method. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification 2008, 47, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larchet, C.; Zabolotsky, V.I.; Nikonenko, P.N.V.V.; Tskhay, A.; Tastanov, K.; Pourcelly, G. Comparison of different ED stack conceptions when applied for drinking water production from brackish waters. Desalination 2008, 222, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Kusher, I.; H. M. A, “3D Printing of micropatterned anion exchange membranes,” ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces (2016). [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Geise, G.M.; Luo, X.; Hou, H.; Zhang, F.; Feng, Y.; Hickner, M.A.; Logan, B.E. Patterned ion exchange membranes for improved power production in microbial reverse electrodialysis cells. Journal of Power Sources (2014). [CrossRef]

- Gurreri, L.; Filingeri, A.; Ciofalo, M.; Cipollina, A.; Tedesco, M.; Tamburini, A.; Micale, G. Electrodialysis with asymmetrically profiled membranes: Influence of profiles geometry on desalination performance and limiting current phenomena. Desalination 2021, 506, 115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The fractal geometry of nature. Macmillan (1983). ISBN 978-0-7167-1186-5.

- Coppens, M.O. Nature inspired chemical engineering learning from the fractal geometry of nature in sustainable chemical engineering. Fractal Geometry and Applications: A Jubilee of Benoit Mandelbrot 2004, 72, 507–532. [Google Scholar]

- Veerman, J.; Metz, S.J. Membrane, stack of membranes for use in an electrode-membrane process, and device and method therefore. Patent WO2011/002288A1.

| Spacer | Membrane | Pdnet (W/m2) | Pdnet (W/m2) | Pdnet (W/m2) |

| @ 0.01 m | @ 0.1 m | @ 1 m | ||

| empty | ideal | 60.2 | 19.0 | 19.0 |

| woven | ideal | 11.58 | 3.66 | 3.66 |

| empty | Qianqiu | 2.43 | 1.91 | 1.91 |

| woven | Qianqiu | 1.63 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Parameter | - | - | Maximized Pdnet | Maximized RPZ | ||||

| Path length | L (m) | m | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 |

| Net power density | Pd_net | W/m2 | 1.63 | 0.99 | 0.47 | 1.05 | 0.74 | 0.38 |

| Net river water yield | Znet | kJ/m3 | 78 | 126 | 156 | 298 | 299 | 272 |

| Flow ratio sea/river water | ΦS/ΦR | - | 0.90 | 1.11 | 1.36 | 5.76 | 3.82 | 3.03 |

| Thickness sea water comp. | δS | μm | 194 | 503 | 1430 | 240 | 590 | 1500 |

| Thickness river water comp. | δR | μm | 96 | 240 | 672 | 54 | 175 | 553 |

| Authors | Ref, | Type | CHC/CLC | Pd (W/m2) | Membrane |

| Liu et al. | [21] | CEM | S/R | 48.4 | Propidium iodide-based two-dimensional polymer |

| Mai et al. | [22] | CEM | 50 | 6.48 | Metal-organic framework |

| Liu et al. | [23] | AEM | S/R | 1.47 | Modified cross-linked alginat hydrogels |

| Guo et al. | [24] | CEM | 50 | 9.2 | Sulfonated poly(ether ether) keton membrane |

| Li et al. | [25] | CEM | 50 | 1.92 | PET-hydrogel heterogeneous membranes |

| Qin et al. | [26] | AEM | S/R | 2.31 | Layered double hydroxide membranes |

| Chen et al. | [27] | CEM | 50 | 10.08 | Zirconium based MOF |

| Awati et al. | [28] | CEM | S/R | 5.35 | VOLD/CNF wrapped carbon nanotubes |

| Cao and Wu | [29] | CEM | 50 | 4.84 | Dual-Network Fiber-Hydrogel Membrane |

| Ren et al. | [30] | CEM | S/R | 21.7 | Oxygen functionalized Mxene |

| Wang et al. | [31] | CEM | 500 | 1.25 | Hole-enriched graphene oxide and cellulose nanofibers |

| Wu et al. | [32] | CEM | 50 | 16.44 | Three-dimensional hydrogel |

| Gu et al. | [33] | CEM | - | 4.66 | Hydrophilic bilayers of vermiculite and Mxene |

| Li et al. | [34] | CEM | 50 | 13.73 | Composite hydrogel |

| Chuang et al. | [35] | CEM | S/R | 9.64 | MOF MIL-178 |

| Lin et al. | [36] | CEM | 500 | 48.5 | Anti-swelling nano-hydrogel |

| Zhou et a.l | [37] | CEM | S/R | 7.7 | Turing-type nanochannels |

| Wu et al. | [38] | CEM | 50 | 30.94 | PASH hydrogel |

| Wei er al. | [39] | CEM | 50 | 21.27 | NaX zeolite |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).