1. Introduction

Single crystal silicon chips have been widely used in devices from macro to nano level, mainly used for lighting, photoelectric detection, and solar energy conversion, attributing to their high direct bandgap, saturated electron velocity, and electron mobility [

1]. However, monocrystalline silicon is type of brittle material with high brittleness, low plasticity, inclusion and crack at ambient temperature, and thus observing the evolution in the processing steps through experiments is very difficult [

2]. In addition, carbides exist in most primary silicon crystals to varying degrees, and their amount is related to the carbon content and crystal position in the crystal. Silicon carbide is the most common inclusion. Especially, with the upgrading of electronic technology, national defense and other industries, the nano processing of monocrystalline silicon crystal materials has become a bottleneck problem. The key to solve this problem is to deeply investigate the polishing mechanism of single crystal silicon with defects [

3]. Nano machining is mainly realized by nano diamond abrasive particles towards achieving the dimensional accuracy of the structure and the nanometer level size device [

4]. Mastering the polishing mechanism of three body abrasive polishing of single crystal silicon can promote the large-scale development of single crystal silicon semiconductor with high precision, high efficiency, and low cost [

5].

At present, molecular dynamics method has been used to study the ultra-precision polishing process, leading to significant achievements in material removal and deformation mechanism and machined surface formation mechanism [

6,

7]. Zhang et al. [

8] established the simulation model of diamond cutting single crystal cerium by molecular dynamics simulation method and revealed that the dislocation and slip are the main mechanism of single crystal cerium deformation, and the removal process of single crystal cerium changes from furrow removal to large deformation removal with increasing cutting depth. Yang [

9] et al. established a three-dimensional simulation model of diamond abrasive polishing single crystal copper and studied the transformation of single crystal copper removal mode from large deformation removal mode to furrow removal mode with increasing rotation speed. Moreover, the rotation speed of abrasive directly affects the surface quality and internal defect distribution of single copper crystal. Fang [

10] et al. established the nanoindentation simulation model of single crystal germanium films and revealed that shear extrusion transformation deformation and dislocation slip are the main deformation mechanisms of single crystal germanium during nanoindentation. Although the material removal mechanism of nano polishing process has been deeply investigated with many outstanding results, the effect of polishing parameters on the material removal mechanism of monocrystalline silicon still needs to be further studied. Zhai [

11] et al. found that ultrasonic assisted chemical mechanical polishing can effectively improve the polishing efficiency and surface quality of silicon workpiece. Fang [

12] et al. studied the relationship between the shape of fixed abrasive particles and material removal, as well as the effect on the surface quality of single crystal silicon. Goel [

13] et al. also investigated the wear mechanism of monocrystalline silicon during single point diamond turning by molecular dynamics simulation.

In contrast, most of the existing simulation studies focus on the ideal defect free crystal materials, but there are some defects such as inclusions, dislocations, and cracks in the actual manufacturing and use process. Defects have attracted the attention of many scholars. Qi and Yang [

14] used molecular dynamics and function methods to study circular inclusions and cracks at any position, leading to the following numerical results: the geometry considered localizes underground high energy. In addition, some scholars studied the free vibration of composite films with hexagonal lattice circular inclusions and analyzed the effect of larger inclusion size [

15]. Their numerical analysis shows that inclusions have an important effect on their research. Mattoni [

16] et al. proved that the interaction between microcracks and hard inclusions (fibers) can improve the mechanical properties β-SiC. The strength of SiC lattice is beyond the linear range. They used surface elasticity to study the surface effect of defects on the deformation of composites. Luo and Wang [

17] used the complex function method to analyze the stress field near an elliptical cylindrical inclusion with interface effect and its interaction with screw dislocation under in-plane shear loading. Mogilevskaya et al. [

18,

19] also used the complex function method to calculate the interaction between nano cylindrical inclusions with interface effect in infinite and semi-infinite bulk. However, the evolution mechanism of nano polishing process cannot be observed by experiments and numerical simulation. Moreover, continuum mechanics cannot be used to analyze the process of nanofabrication, thus necessitating to study the mechanism of nanofabrication from the perspective of atoms and molecules. Molecular dynamics simulation plays the role of bridge between macro characteristics and microstructure and has become the most important simulation method. Therefore, studying the polishing process of single crystal silicon with inclusions by molecular dynamics simulation is of great theoretical and practical value.

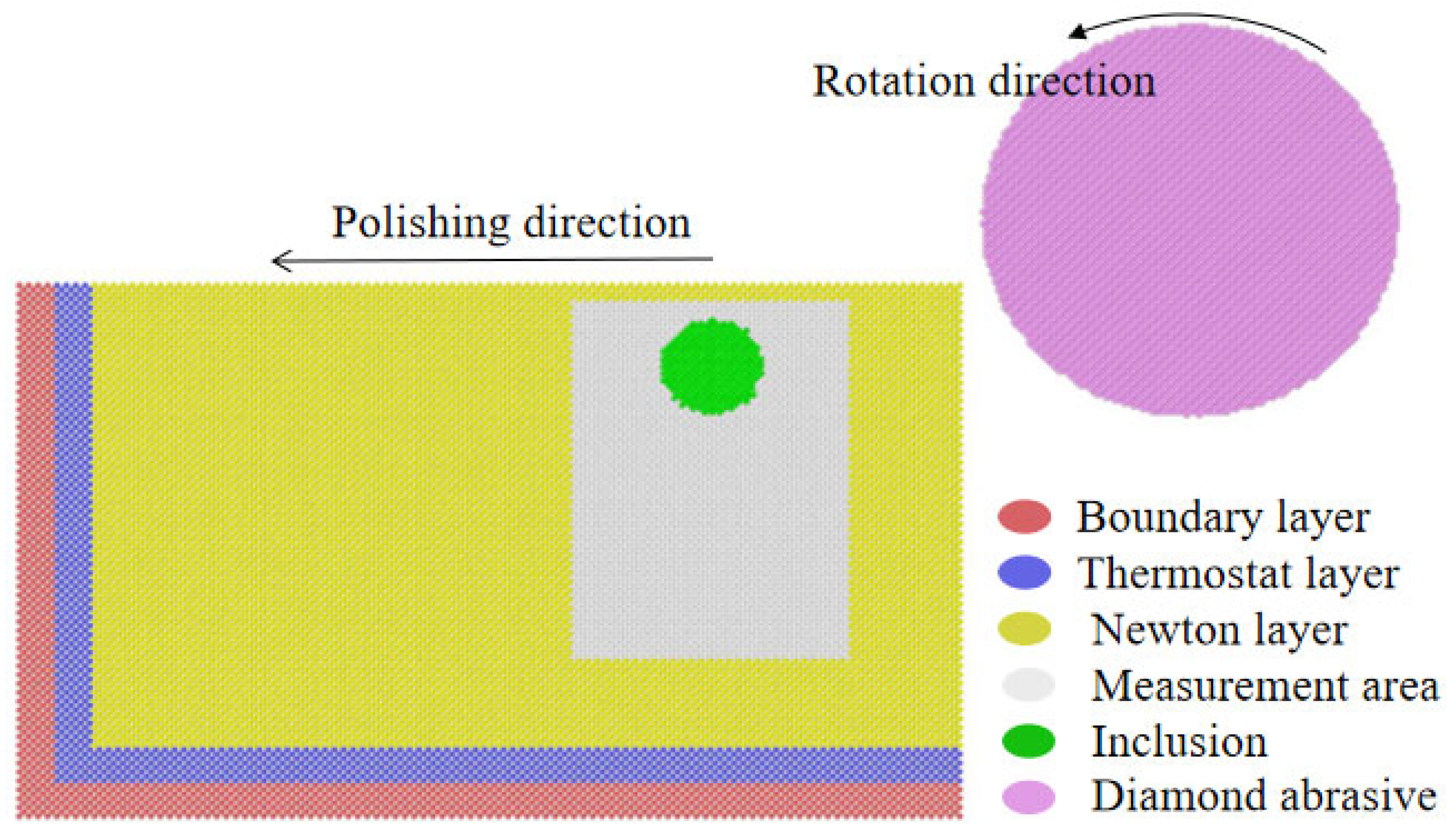

In this study, a model of polishing monocrystalline silicon workpiece with diamond abrasive particles containing different diameter silicon carbide inclusions was established, and the basic polishing characteristics, i.e., the effect of the size of silicon carbide inclusions on friction coefficient, flatness, and material removal rate was studied by molecular dynamics simulation. At the same time, the morphology of the workpiece surface and the damage of the sub surface were observed, and the thermodynamic information and mechanical properties were analyzed to understand the polishing mechanism of single crystal silicon with inclusion defects.

3. Results and Discussion

The effect of the diameter of round silicon carbide inclusions on the polishing process is discussed in this section. The coordination number, polishing force, friction coefficient, potential energy, polishing temperature, diamond structure surface morphology, and dislocation were analyzed in detail. The simulation results of this study are all from MD simulation of open-source software LAMMPS [

32]. The MD simulation results were visualized by OVITO software [

33] and processed by origin.

In the process of polishing, temperature is a very important physical characterization for studying polishing mechanism. The temperature is calculated according to the following formula [

34]:

. Where N represents the number of atoms,

is the velocity of the ith atom,

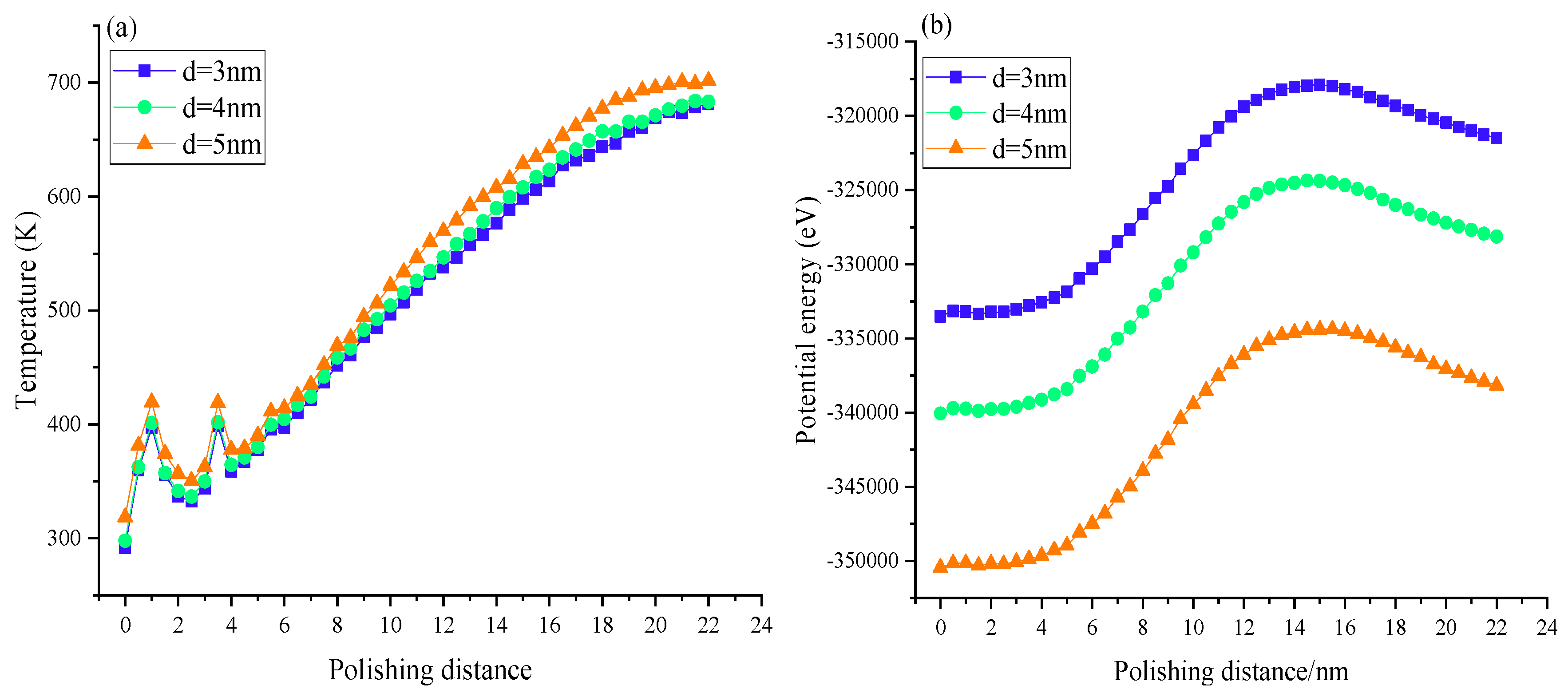

is the Boltzmann constant, and T represents the atomic temperature. The temperature changes mainly because of the friction and extrusion between diamond abrasive and single crystal wafer. In addition, inclusions in monocrystalline silicon also have an important effect on temperature. The change in the polishing temperature not only affects the service life of abrasive particles, but also affects the surface and sub surface quality of the workpiece to be polished. Therefore, the study of the change in polishing temperature is an important aspect of the study of material removal and surface formation mechanism. In order to better understand the evolution mechanism of the polishing process from the perspective of polishing temperature, as shown in

Figure 2 (a), the polishing temperature increases with increasing polishing distance. Obviously, the larger the diameter of the inclusion causes the higher the polishing temperature in the measurement area. This is very well understood, because the larger the diameter of the inclusion, the larger the contact area and contact stress between the abrasive particles and the inclusion during polishing, increasing the extrusion shear deformation of the workpiece, and the energy released by the workpiece will increase accordingly, increasing the temperature change. However, the effect of the size of inclusions on the temperature difference is not very obvious. The main reason for the temperature change is the extrusion and friction of the abrasive particles and workpieces.

Figure 2 (a) shows that the temperature difference caused by the size of inclusions increases when polishing to the 8 nm position, because the number of atoms in bct-5 and Si-II (CN=6) increases, the fracture of atomic bond, lattice deformation, and reconstruction increase the temperature. Notably, the temperature rises sharply and fluctuates in the initial stage of polishing because of the inclusion in the workpiece. Then, the grinding particles move forward, and the temperature changes tend to be stable. Obviously, when the abrasive particles move to the top of the inclusion, the inclusion makes the polishing process generate more heat, and the larger the inclusion, the more heat will be generated.

The potential energy of the measurement area varies with the polishing distance as shown in

Figure 2 (b), indicating that when the polishing distance is less than 14 nm, the potential energy rises rapidly; when the polishing distance is more than 14 nm, the potential energy decreases, and tends to be in dynamic balance with the polishing process. When the diamond abrasive particles just contact the monocrystalline silicon atom, the covalent bond of the silicon atom is broken because of the squeezing of the silicon atom before and below the grinding grain. Moreover, the energy generated by the plough of diamond abrasive grains will be stored in the lattice of silicon in the form of lattice deformation energy, thereby the induced potential energy increases rapidly. Then, the potential energy decreases slowly because of the energy consumption of crystal reconstruction and elastic recovery of the machined surface. With increasing polishing process time, the potential energy tends to be in stable dynamic equilibrium state. It is worth noting that the potential energy is different in the initial stage of polishing, because of the difference of the size of inclusions. The larger the diameter of the inclusions, the smaller the initial potential energy, and the lower the average value of the potential energy.

Figure 2 (b) also shows that after entering the polishing process, the potential energy increase rate of the system increases with increasing number of inclusions, because the effect of abrasive particles and inclusions increases with increasing number of inclusions; therefore, the number of atoms removed will increase, the lattice deformation of atoms and the energy released by amorphous phase transition increase, eventually increasing the potential energy change of the system.

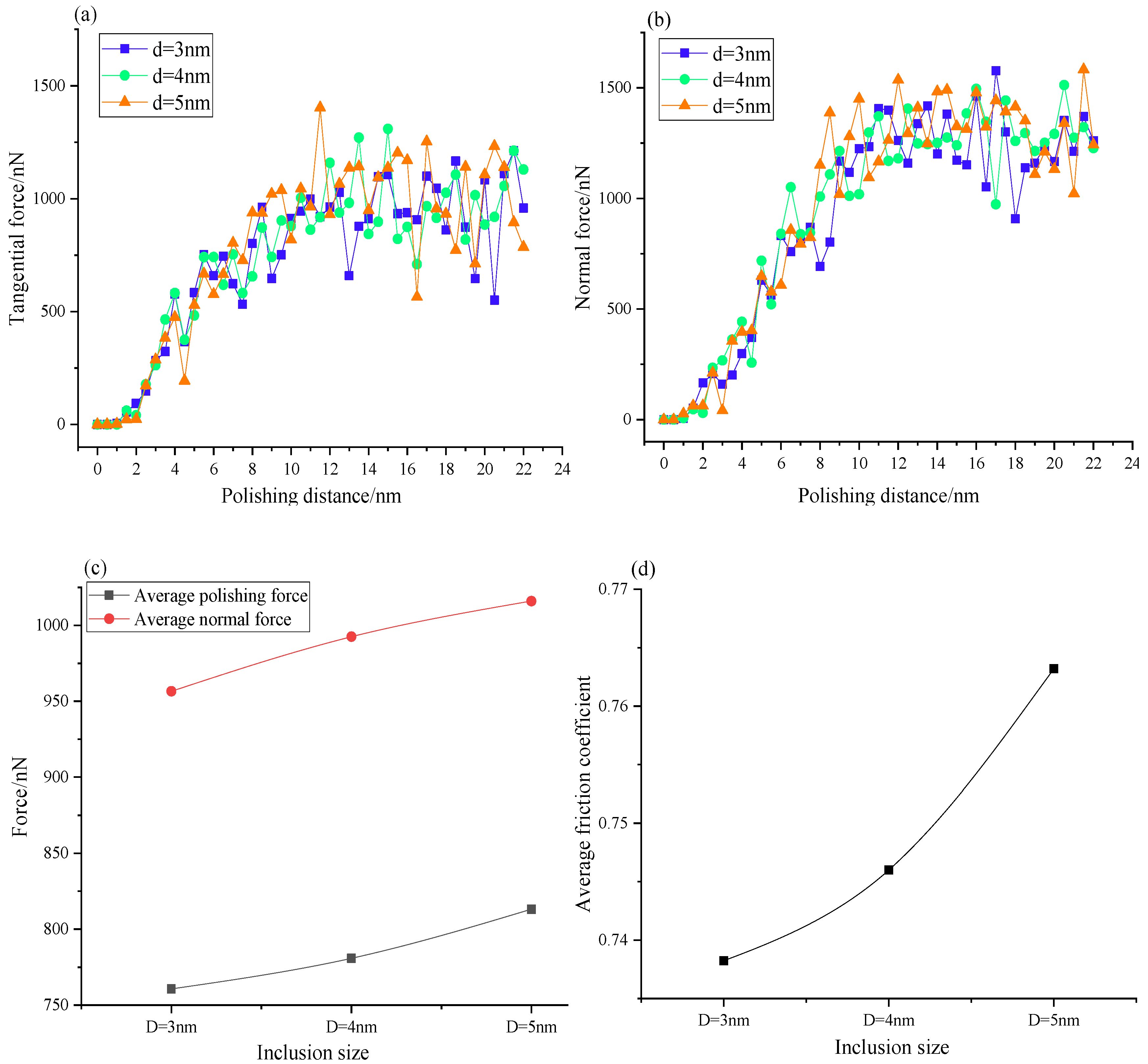

In the nano polishing process, the main source of polishing force is the interaction between abrasive atoms and silicon workpiece atoms. In this study, the source of polishing force is not only the interaction between abrasive atoms and workpiece, but also the size of inclusions in workpiece. The polishing force is mainly composed of normal force and tangential force.

Figure 3 (a) and (b) show the curves of tangential force and normal force varying with polishing distance, respectively, indicating that: (1) in the polishing process, the variation trend of tangential force and normal force is similar with some fluctuations; (2) in the initial stage of polishing, the growth rate of tangential force and normal force is higher, but the growth rate of the normal force is greater than the tangential force. When polishing to 10 nm, the force tends to be in a stable dynamic equilibrium, and the dynamic equilibrium value of normal force is greater than the tangential force. The crystal deformation and reconstruction of silicon atoms and the internal inclusions are the main reasons for the fluctuation. The elastic recovery of the machined surface also has a certain influence on it. Because of the inclusion in the workpiece, the normal force will be opposite to the normal force in the polishing process, resulting in a higher average value of the normal force. Because of the fluctuation of the force curve, the average force (tangential force and normal force) as shown in

Figure 3 (c) is plotted to better represent the effect of different size inclusions on the force.

Figure 3 more intuitively shows that the average normal force is greater than the average tangential force. The average force increases with increasing inclusion diameter. The friction coefficient is mainly used to characterize the ability of diamond particles to remove silicon surface materials.

Figure 3 (d) shows that the friction coefficient increases with increasing number of inclusions. In the absence of any inclusion in monocrystalline silicon workpiece, the friction coefficient of monocrystalline silicon polished by diamond abrasive can reach 0.797 [

35]. This study proved that the a certain size of inclusions in the workpiece can reduce the friction coefficient and increase the machinability of the material.

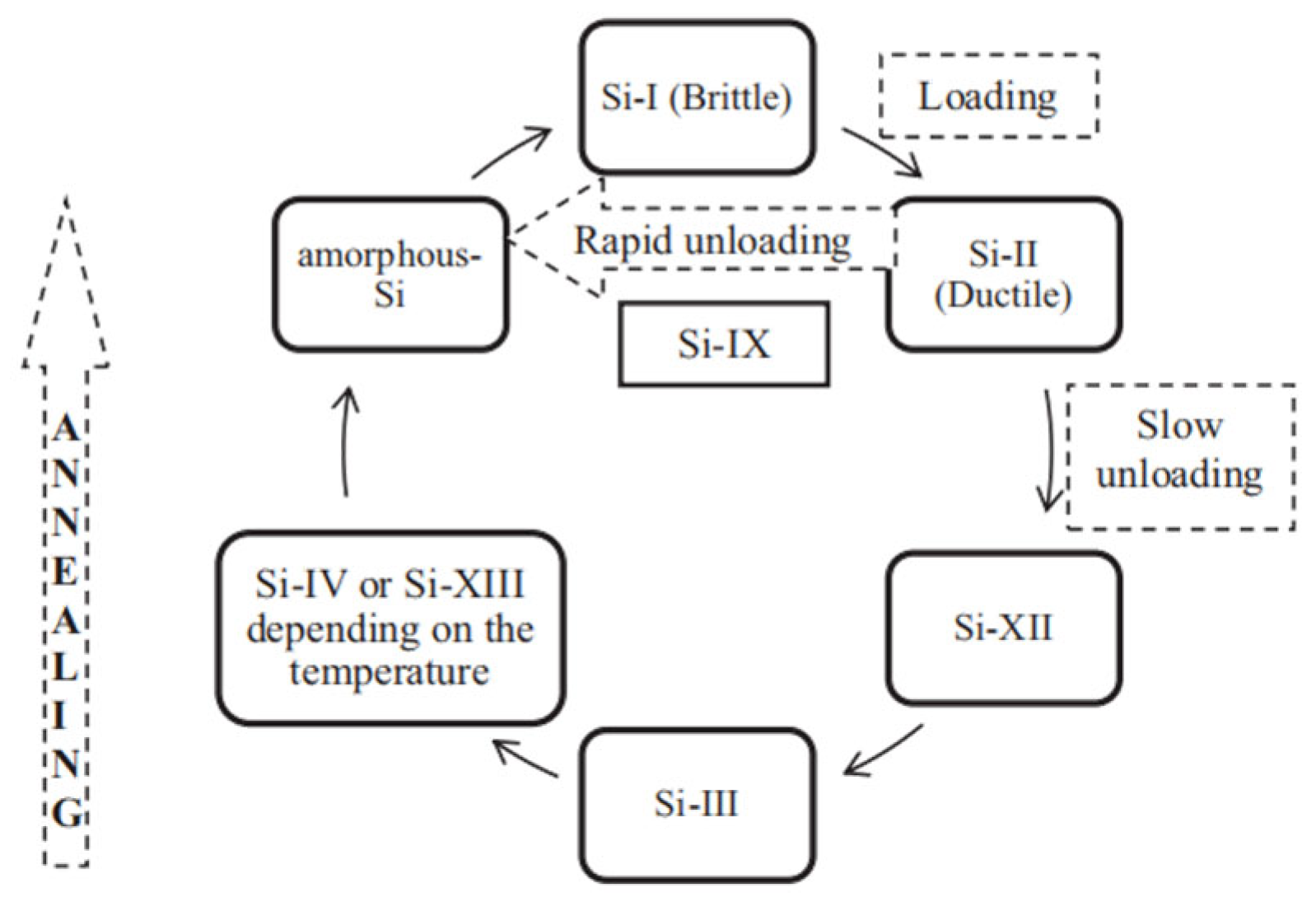

Different coordination numbers represent different crystal phases, which in turn leads to monocrystalline silicon with different properties. Therefore, the study of phase transition structure plays an important role in revealing the mechanism of mechanical polishing. According to Goel and Luo et al. [

34], the transformation process between different phases under contact load is shown in

Figure 4. In this study, SI-I phase is an atom with CN = 4; bct-5 phase is an atom with CN = 5; Si-II phase is an atom with CN = 6; and atoms with coordination number 7 or more is high pressure phases. The effect of inclusion diameter on the atomic phase transformation during polishing was investigated, the diagram of phase transformation atoms with polishing distance is shown in

Figure 5. Obviously, the number of defect atoms in different phases increases with increasing polishing distance. With the progress of polishing distance, the diamond particles squeeze and rub the workpiece forward and downward, causing atomic bond fracture and lattice reconstruction of silicon atoms.

Figure 5 (a) shows the evolution trend of atoms of bct-5 phase (CN = 5) with polishing distance when the diameter of SiC inclusion in silicon workpiece is different. Although the variation curves of the number of atoms in bct-5 phase are almost intertwined with each other at different inclusion diameters, the evolution trend is nearly the same. Larger inclusion diameter produced more defect atoms. The main reason for the formation of bct-5 phase (CN = 5) atoms is the stress concentration in the workpiece, and the increase in the inclusion size is the main reason for the increase of bct-5 phase atoms. In brief, the larger the diameter of the inclusion, the larger the stress concentration area, resulting in more bct-5 phase atoms.

Figure 5 (b) and (c) show the changes of Si-II phase (CN = 6) atoms and high-pressure phase atoms, respectively. In the polishing process, the bct-5 phase (CN = 5) has the most atoms and the Si-II phase (CN = 6) has the least, because the Si-II phase silicon atoms are reversible and unstable, and is easy to transform into other phase atoms in the polishing process, also explaining the fluctuation of the number of silicon atoms with the coordination number of 6 and the reason of the least number. High temperature and high pressure near the abrasive particles are the main reasons for the occurrence of atoms with coordination number greater than or equal to 7. Figure. 5 (c) shows that the larger the inclusion diameter is, the fewer the number of atoms with a ligand greater than or equal to 7. Wang et al. [

36] showed a certain degree of damage on the surface of the workpiece, which can in turn enhance the machinability of the workpiece. The presence of inclusions will cause atomic defects in the workpiece and reduce the cutting force, improve the extreme conditions near the abrasive particles, and reduce the generation of high-pressure phase atoms. Therefore, silicon carbide inclusions with a certain size can improve the machinability of monocrystalline silicon and reduce the surface and subsurface damage caused by machining.

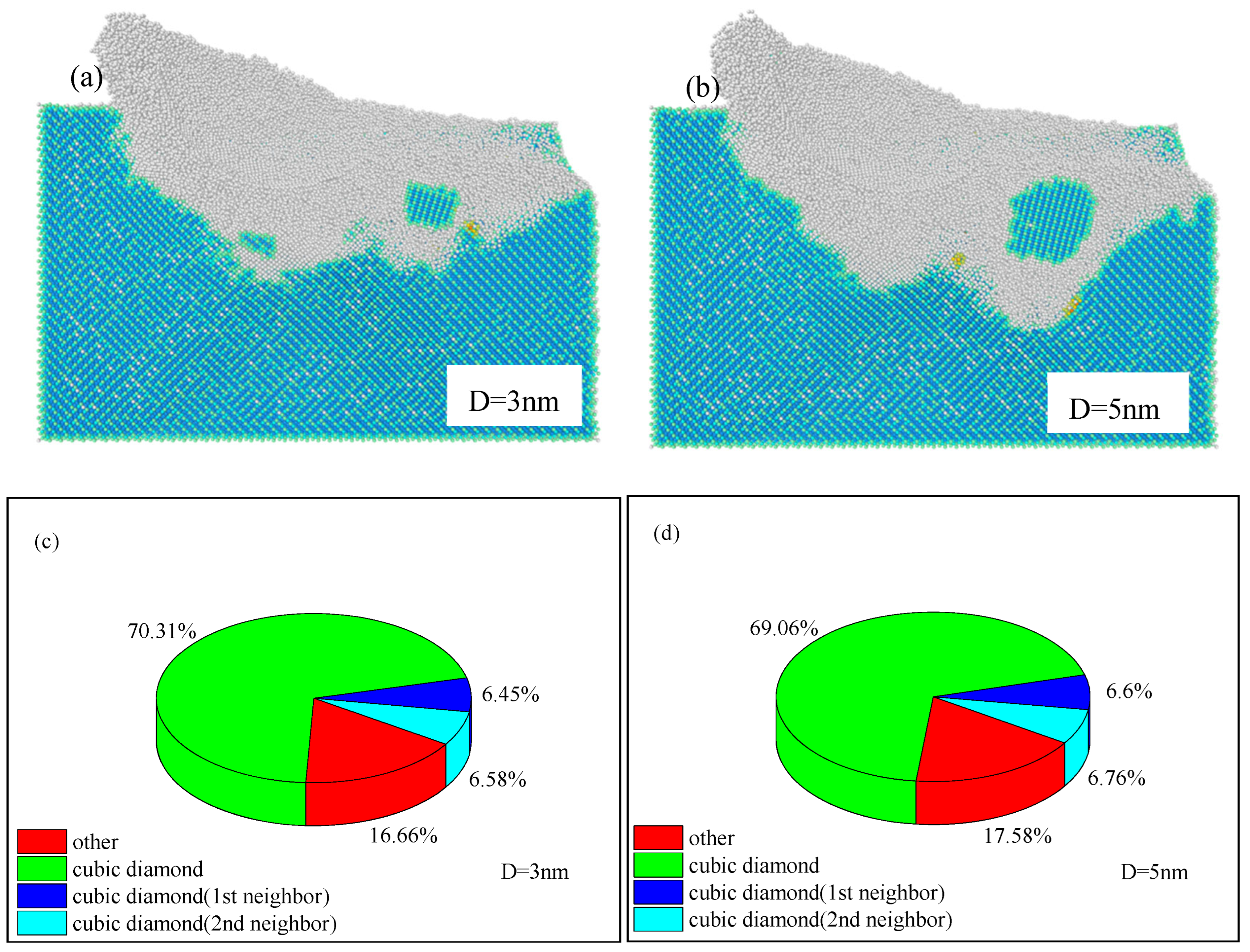

The previous study of coordination number indicated that changing the diameter of SiC circular inclusion has an important effect on the coordination number of monocrystalline silicon. The distribution of atoms with different coordination endows different properties and surface characteristics of the workpiece. Herein, the inclusion diameters of 3 nm and 5 nm were chosen to study the effect the inclusion diameter on the surface morphology of the workpiece. As shown in

Figure 6, when the inclusion diameter is 3 nm, the silicon atoms with different coordination numbers evolve with the polishing process. A comparison with

Figure 7 shows that the larger the diameter of inclusions, the more atoms of bct-5 phase (CN = 5) and Si II phase (CN = 6) are produced when diamond grains contact with inclusions in the workpiece. The forward movement of the abrasive above the inclusion produces a large number of CN ≥ 7 phase atoms. The larger the diameter of the inclusion is, the CN≥ 7 phase atoms are produced, because the circular inclusion is directly under the abrasive particles, causing stress concentration, and a large number of high-pressure phase atoms are produced in the high-temperature and high-pressure environment. When the abrasive particles just contact with the circular inclusion, the defect atoms are mainly concentrated in the contact position of the abrasive particles and the circular inclusion. At this time, the bct-5 phase (CN = 5) atoms produced by the smaller inclusion are more than those produced by the inclusion with a diameter of 5 nm. When the abrasive particles move directly above the circular inclusion, the larger the diameter of the inclusion is, the more defect atoms are produced below the inclusion. In addition, the large inclusion leads to increased number of defect atoms in the subsurface layer after abrasive polishing. When the abrasive particles move to the final state, a large number of atoms of bct-5 phase (CN = 5) still gather under the inclusion when the inclusion is large, while the number of atoms of bct-5 phase (CN = 5) under the inclusion with small inclusion is less. The increase in inclusion size has little effect on the accumulation of surface materials and the height of surface bulge, and the inclusion mainly affects the subsurface damage depth of the workpiece.

Figure 8 shows the subsurface damage depth in the final state at the inclusion diameters of 3, 4, and 5 nm. Obviously, the larger the inclusion diameter is, the deeper the subsurface damage depth is. In contrast, with increasing number of inclusions, no significant chip accumulation was observed on the surface of the silicon workpiece, i.e., there are certain inclusions in the silicon workpiece, which will not reduce its surface quality.

Figure 8 shows that the damaged atoms are mainly concentrated in the contact area between the abrasive particles and the workpiece, among which the atoms of high-pressure phase (CN ≥ 7) and Si II phase (CN = 6) are the most significant, and some of the atoms of bct-5 phase (CN = 5) are located at the bottom of the abrasive polishing position and some around the impurity. With the movement of the abrasive particles, the atomic lattice of the silicon workpiece is squeezed by the polishing force, and the surface atoms are pushed by the abrasive particles. With the progress of polishing, the interaction between abrasive particles and inclusions intensifies, and the energy generated by lattice deformation is stored in the lattice of single crystal silicon. When the stored energy reaches a certain value but is not enough to form dislocation, the silicon atomic bond breaks, leading to lattice reconstruction and generation of more silicon atoms with different coordination numbers. With the increasing polishing time, subsurface gets damaged.

In order to distinguish hexagonal structure from the diamond structure, the second layer neighbor particles are considered in the method of identifying diamond structure. Common neighbor analysis (CNA) is usually used to distinguish FCC, HCP, and BCC structures, but it is not suitable to distinguish diamond structures, because there is no common neighbor between the first layer neighbors, and the second and third layers cannot be well distinguished. Because of the changing diameter of the inclusions at the same position in the polishing process, the motion process of the inclusions is similar to the evolution process of the damaged atoms. This part only discusses the final polishing effect in the case of d = 3 nm and 5 nm.

Figure 9 (a) and (b) show the final state of the workpiece after interaction with the abrasive at the inclusion diameters of 3 and 5 nm, respectively. Obviously, the larger the diameter of the inclusion is, the more atoms of diamond structure will be destroyed. The larger the size of inclusions, the more prominent the stress concentration in the workpiece, and the more strong the interaction among the workpiece, abrasive particles and inclusions, destroying the diamond structure of the workpiece. Although the inclusion moves slightly along the polishing direction, it does not damage the diamond structure of SiC inclusion.

Figure 9 shows that in the cubic diamond, the neighboring atoms of the first and second layers are arranged according to the lattice of BCC diamond. Cubic diamond (1st neighbor) means that the four neighbor atoms of the first layer are arranged according to cubic diamond, but at least one of the second layer is not. Cubic diamond (2nd neighbor) indicates that at least one of the first layer is missing or not in the lattice position. Other means hexagonal diamond structure and unknown coordination structure. In order to quantify the number of atoms in the damaged diamond structure, the pie chart as shown in

Figure 9 (c) and (d) was drawn according to the silicon atoms of different structure types to indicate their proportion. A comparison of

Figure 9 (c) and (d) indicated that increasing diameter of inclusions will indeed increase of the number of atoms in the damaged diamond structure. Therefore, in order to improve the surface quality of the workpiece after polishing, the presence of larger inclusions should be avoided.

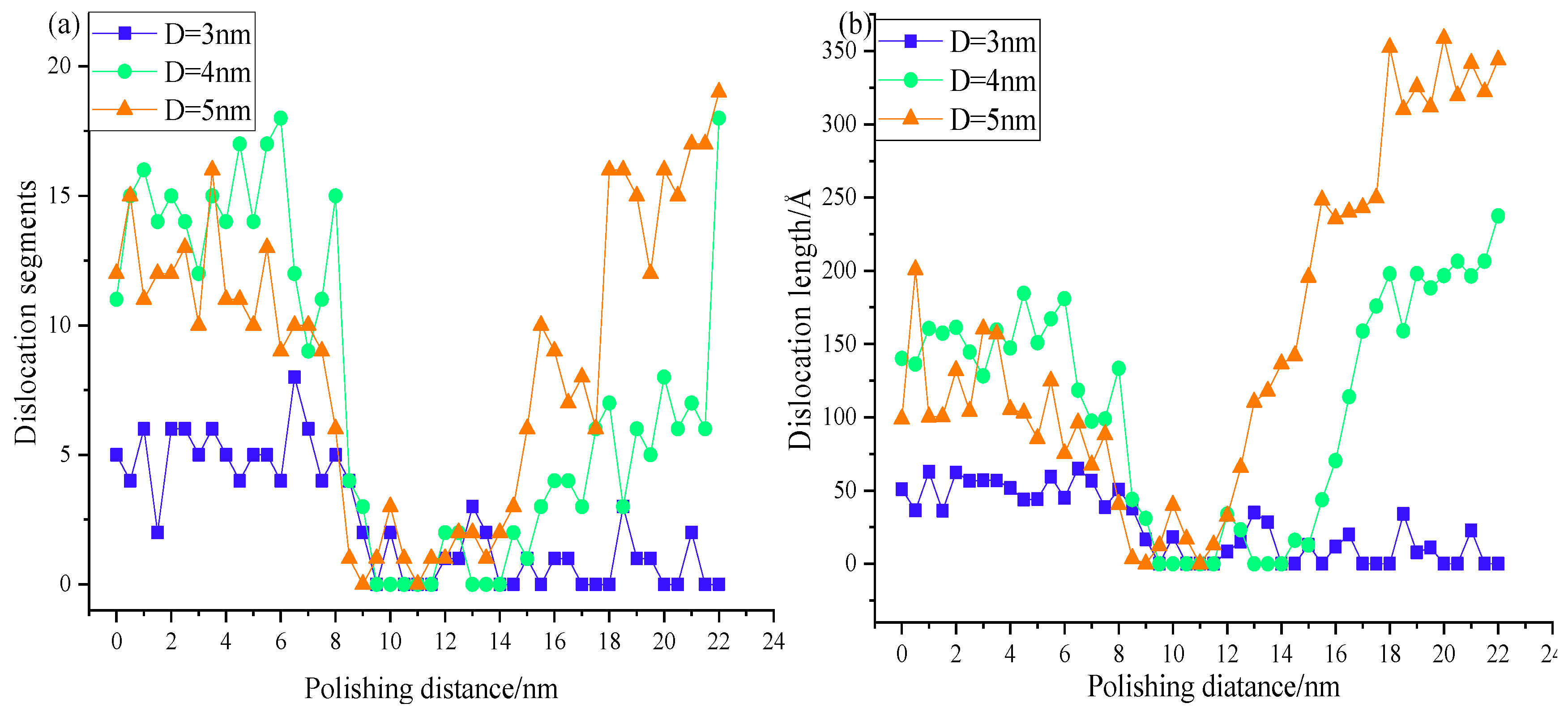

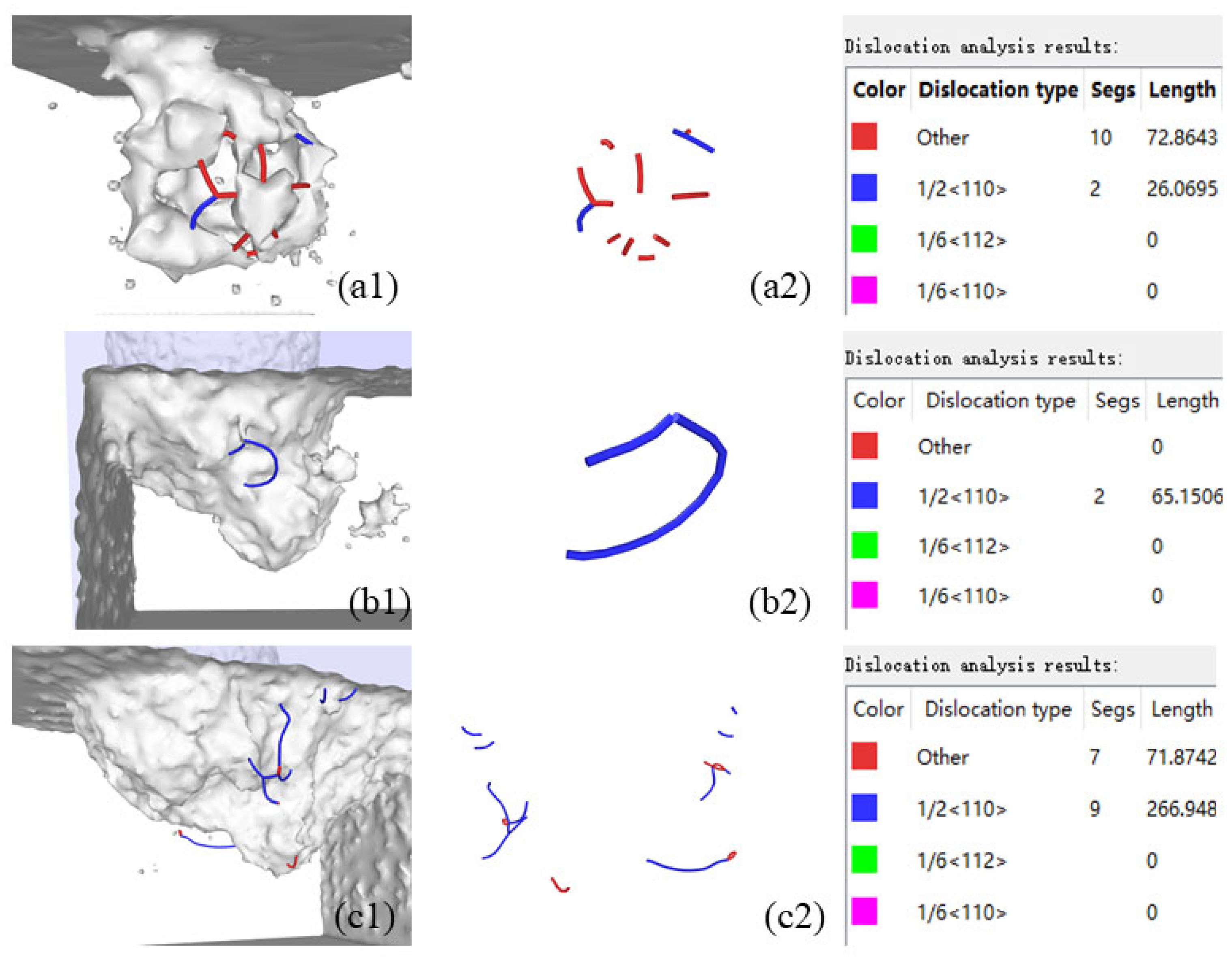

The DXA (dislocation extraction algorithm) analysis of the simulation results lead to the following correct position error views.

Figure 10 shows the number of dislocations in the atoms inside the silicon carbide workpiece with SiC inclusions and the total length of the dislocation segments changing with the polishing progress. The total length and number of dislocation segments decrease first and then increase. With increasing diameter of SiC inclusions, the number of dislocations increases, and the total length of dislocation section increases. The difference between the number of dislocation segments and the total length of the dislocation segments in the initial polishing period is smaller, mainly because the diamond abrasive particles have not been strongly affected by the internal inclusions; when polished to 9–12 nm, the number and total length of dislocation segments decreased to 0. Elastic recovery occurs during this period; then, with increasing inclusions, the difference between the number of dislocation segments and the total length is more and more obvious. In conclusion, the smaller the diameter of the inclusions, the less the number of dislocations and the shorter the total length of the dislocation section.

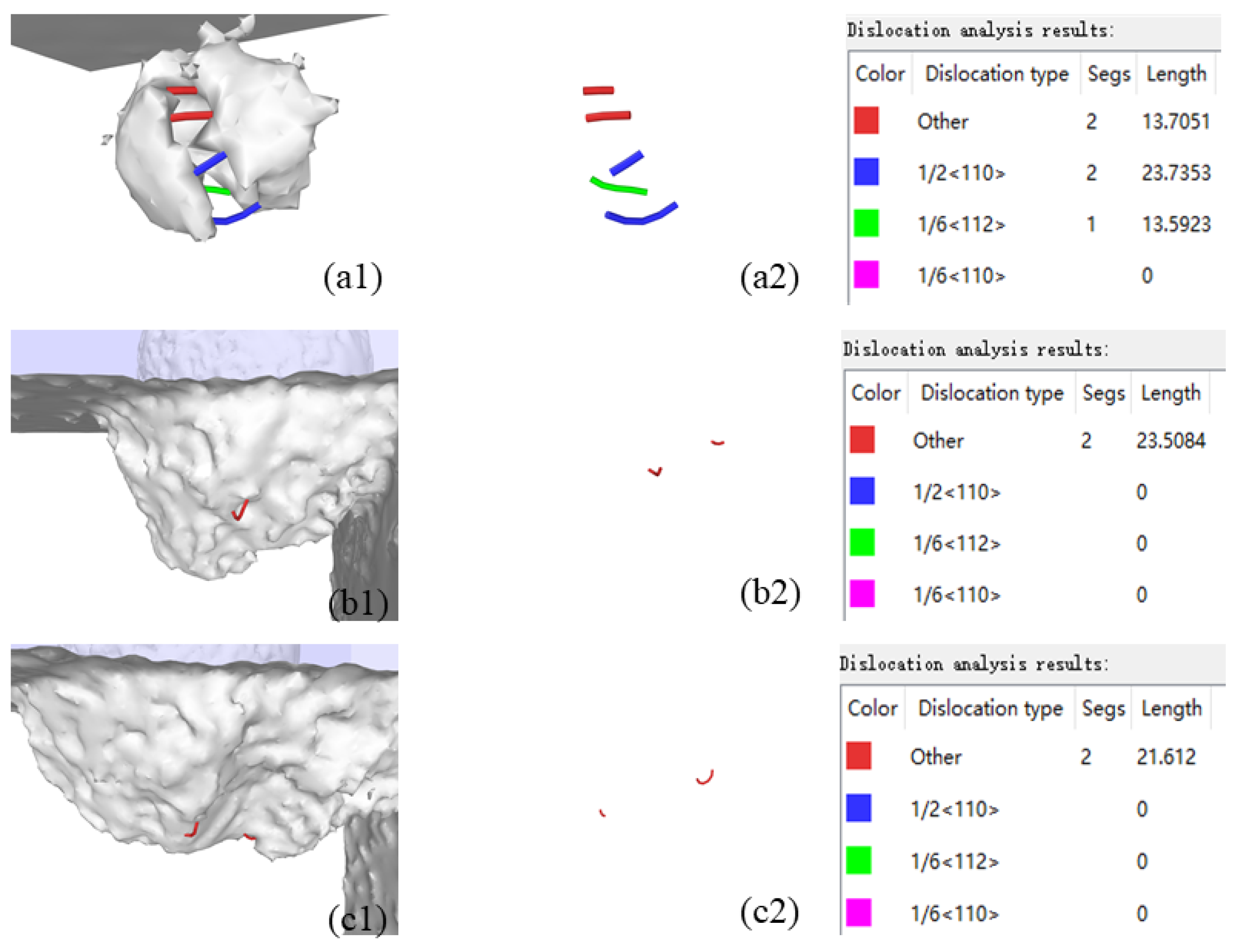

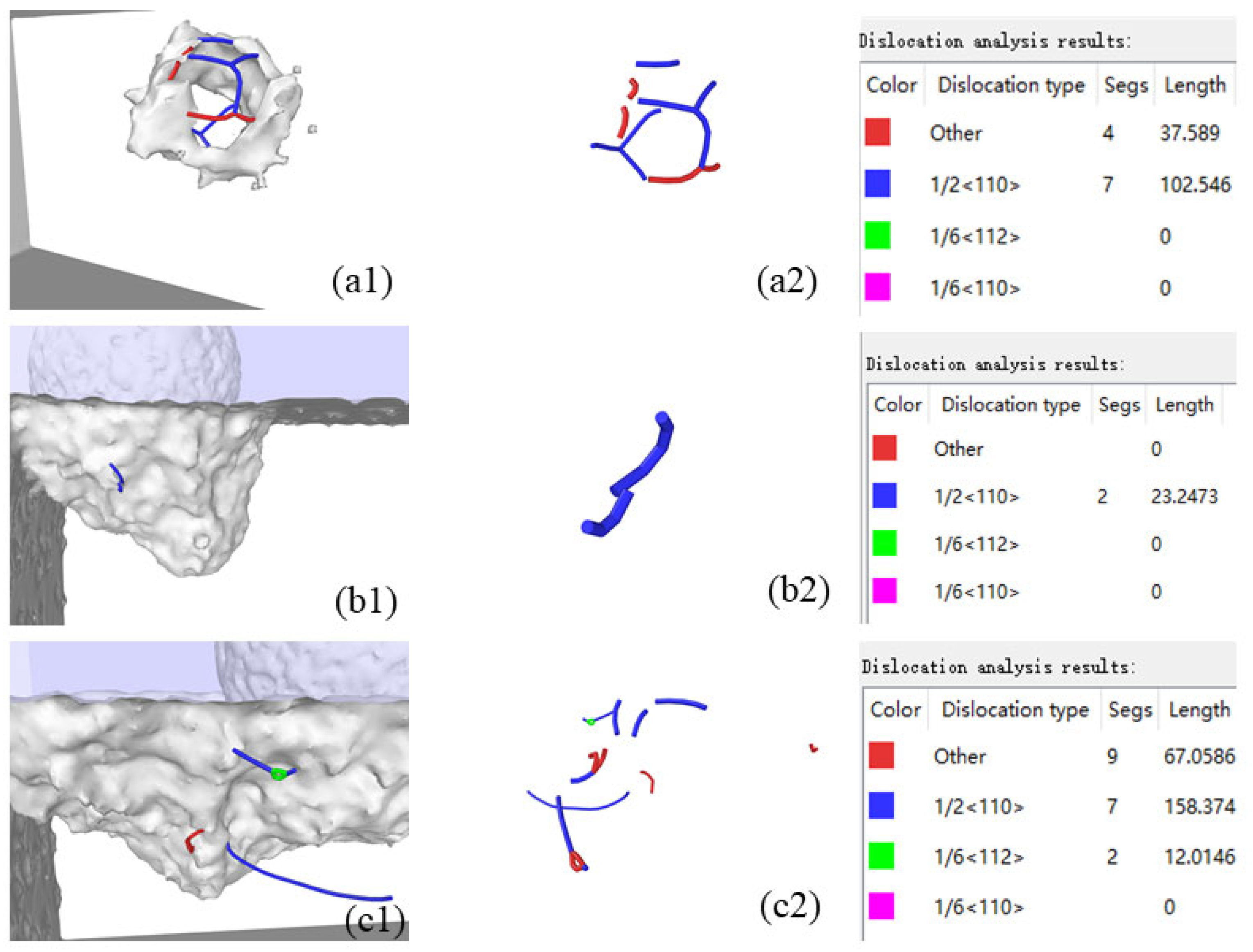

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 (A1) shows dislocation graphs at the initial stage of polishing when the inclusion diameter is 3, 4, and 5 nm respectively. With increasing inclusion diameter, the total length of dislocation section is larger. Although the inclusions are the smallest, the dislocation types are the most. The dislocation diagram of the polishing medium period is shown in

Figure 11-13 (B1) when the inclusion diameter is 3, 4, and 5 nm. At this time, the number of dislocations in three cases is very small. The dislocation diagram at the end of polishing is shown in

Figure 11-13 (C1) after the completion of the polishing at the inclusion diameters of 3, 4, and 5 nm. When the diameter of the inclusion is 3 nm, the number of dislocations is very small; when the diameter of the inclusion is 4 nm, there are a lot of complex dislocation segments at the end of polishing, and the dislocation segments with Burgers vector of 1/6 < 110 > appear. The results show that the number and total length of dislocation segments increase with increasing number of inclusions.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, a molecular dynamics simulation model of monocrystalline silicon with circular inclusions in diamond nano polishing was established by the molecular dynamics method. The effects of changing the size of inclusions in silicon workpiece on potential energy, temperature, polishing force, surface morphology, coordination number, and dislocation were studied and analyzed. The following conclusions can be drawn from this study:

(1) The larger the size of inclusions in the workpiece, the deeper the subsurface damage. The increase in inclusion size will increase the damage of diamond structure. At the same time, polishing process releases more heat, increasing the temperature, but to a certain extent, it can reduce the potential energy generated in the polishing process.

(2) The polishing force and normal force increase with increasing inclusion size. The larger the inclusion size is, the larger the friction coefficient is. However, the presence of a certain size of inclusions in the workpiece can reduce the friction coefficient and increase the machinability of the material.

(3) The defect atoms in the workpiece mainly exist in bct-5 phase, and the larger size of the inclusion results in a large number of bct-5 phase (CN = 5) atoms under the inclusion. The larger the inclusion diameter is, the less high-pressure phase (CN ≥7) atoms are produced, which can improve the machinability and surface quality of silicon workpiece.

(4) The DXA analysis shows that the smaller the diameter of the inclusion, the less the number of dislocations and the shorter the length of the dislocation segment. With increasing diameter of the inclusion, the more dislocation types and the more dislocations are produced.