1. Introduction

The appearance of high entropy alloys breaks the traditional design concept of alloy based on mixing enthalpy and opens up a broad space for composition design for the research and development of new materials. The comprehensive effect of the mixing of various main elements endows the high entropy alloy with high entropy effect in thermodynamics, lattice distortion effect in structure, hysteresis diffusion effect in dynamics and “cocktail” effect in performance [

1,

2]. The principle of multi principal element design based on four effects makes the high entropy alloy show many unique properties beyond the traditional alloy. These characteristics cover excellent corrosion resistance[

3], wear resistance [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], excellent fatigue strength and yield strength under various temperature conditions [

10,

11], high hardness [

12], excellent microstructure stability and thermal stability [

13,

14] and excellent high-temperature oxidation resistance [

15]. In view of its outstanding mechanical and functional characteristics, high entropy alloys show broad application prospects in many fields, such as marine engineering, automotive industry, energy development, chemical industry and biomedicine [

16,

17,

18,

19].

FeNiCrCo-X high entropy alloys have become a research hotspot of relevant scholars in recent years because of their unique physical properties such as high temperature stability [

13], high hardness and high strength [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

12]. Among them, FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloys has excellent wear resistance, which is regarded as ideal high-temperature wear-resistant materials, attracting a large number of scholars to study them. A new Al

0.75CrFeNi eutectic high entropy alloy was prepared composed of disordered body centered cubic phase and ordered body centered cubic (BCC) phase, which shows excellent mechanical properties and high yield strength [

20]. Mohsen et al. [

21] systematically studied the wear resistance of Al

xCo

1.5CrFeNi

l.5Ti

y system and found that the wear resistance of Co

l.5CrFeNi

l.5Ti and A1

0.2Co

1.5CrFeNi

l.5Ti alloys was at least twice that of conventional wear-resistant steel. Braic et al. [

22] used (TiZrNbHfTa)N high entropy alloy as a protective coating in the biomedical field to improve the indicators of titanium alloy implants, they pointed out that the hardness of the alloy increased to 30GPa, and the surface wear rate was as lower than 0.2x10-6mm3N-1m-1. Li et al. [

23] found that FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy coating on the surface of Cu matrix can effectively improve the wear resistance of the material by molecular dynamics method. They reached conclusion that increase of friction velocity results in the reduction of tangential force affected by material thermal softening and the increase of normal force affected by material strain rate hardening, and therefore leads to the reduction of friction coefficient [

23]. Yang et al.[

24] found that the hardness and Young’s modulus of AlCoCrFe high entropy alloy coatings are about 10 times that of the substrate metal Al. In the interface area between the high entropy alloy coating and the Al substrate, as the laser heating during the manufacturing process of the high entropy alloy coating, a part of substrate is melted and reacts with other elements in the coating forming some BCC structures which can effectively protect the matrix material from wear. [

24]. Doan et al. [

8] used AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy as a coating material adhered to the surface of Ni substrate, found that Ni based alloys are protected by high entropy alloy coatings with less wear. With the increase of friction depth, the resistance of tool movement is greater, and the friction coefficient increases. Instead, due to the effects of thermal softening and strain rate hardening, the friction coefficient decreases with the increase of friction speed [

8]. Bui et al. [

25] investigated the effects of composition, grain size, and cutting depth on the deformation behavior and damage of NiCoCrFe high entropy alloys. It was found that dislocations increase with the increase of Co content, Ni

25Co

25Cr

25Fe

25 high entropy alloy has the highest number of worn atoms, while the Ni

25Co

25Cr

30Fe

20 high entropy alloy has the lowest number of worn atoms.

At present, researchers mainly focus on studying the room temperature friction performance of high entropy alloy materials and have not studied the overall wear resistance of coating materials at different temperatures. However, it is difficult to observe its microscopic deformation mechanism during the experimental process, and effective conclusions cannot be drawn on the impact mechanism of wear resistance at different temperatures. Therefore, in response to the current research shortcomings of high entropy alloys coatings, this study adopts molecular dynamics methods to analyze the influencing mechanism of wear resistance of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy coatings at different temperatures from the microstructure, to provide theoretical basis for practical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Friction Simulation

In this work, single crystal Cu was used as the matrix material and FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy is used as the coating material. The lattice types of both materials are face centered cubic (FCC). The lattice constant of Cu was set as 3.56Å, the lattice constant of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy was also set as 3.56Å. The dimensions of Cu matrix were 72Å×185.2Å×52Å, and the total number of atoms was 62423. The ambient temperature was set at 300K, 600K, 900K and 1200K. The high entropy alloy coating was 21Å. Same crystal orientations of matrix and coating material in X axis, Y axis and Z axis were set as [100], [010] and [001] directions respectively. The virtual indenter of Lammps was used in this simulation. This nano indentation simulation method has already been widely used [

26,

27]. The form of force field between virtual indenter and atoms is shown in equation as follows [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]:

where

K is the specified force constant;

r is the distance from the atom to the center of the indenter;

R is the indenter radius. In this simulation, the value of constant

K is set as 3ev/Å, which is considered to be very reliable in the simulation of multiple nanoindentation [

23,

26].

After the initial model was built, in order to eliminate the unreasonable structure in this model, the conjugate gradient algorithm [

35] was used to minimize the energy of the model firstly. Then, the model was relaxed. In the relaxation process, periodic boundary conditions were used in the X, Y and Z directions of the model, and the model was initialized at 300K. In the next four steps, the Nosé-Hoover hot bath method [

36] was used to control the system. In the first step, the NPT ensemble [

37,

38] was used to raise the temperature of the model from 300K to 1000K, taking 200ps; In the second step, the NVT ensemble [

38] was used to maintain the model at a temperature of 1000K for 100ps; the third step was to use NPT ensemble to reduce the temperature from 1000K to 300K, which takes 200ps; the fourth step was to use NVT ensemble model to maintain 100ps at 300K.

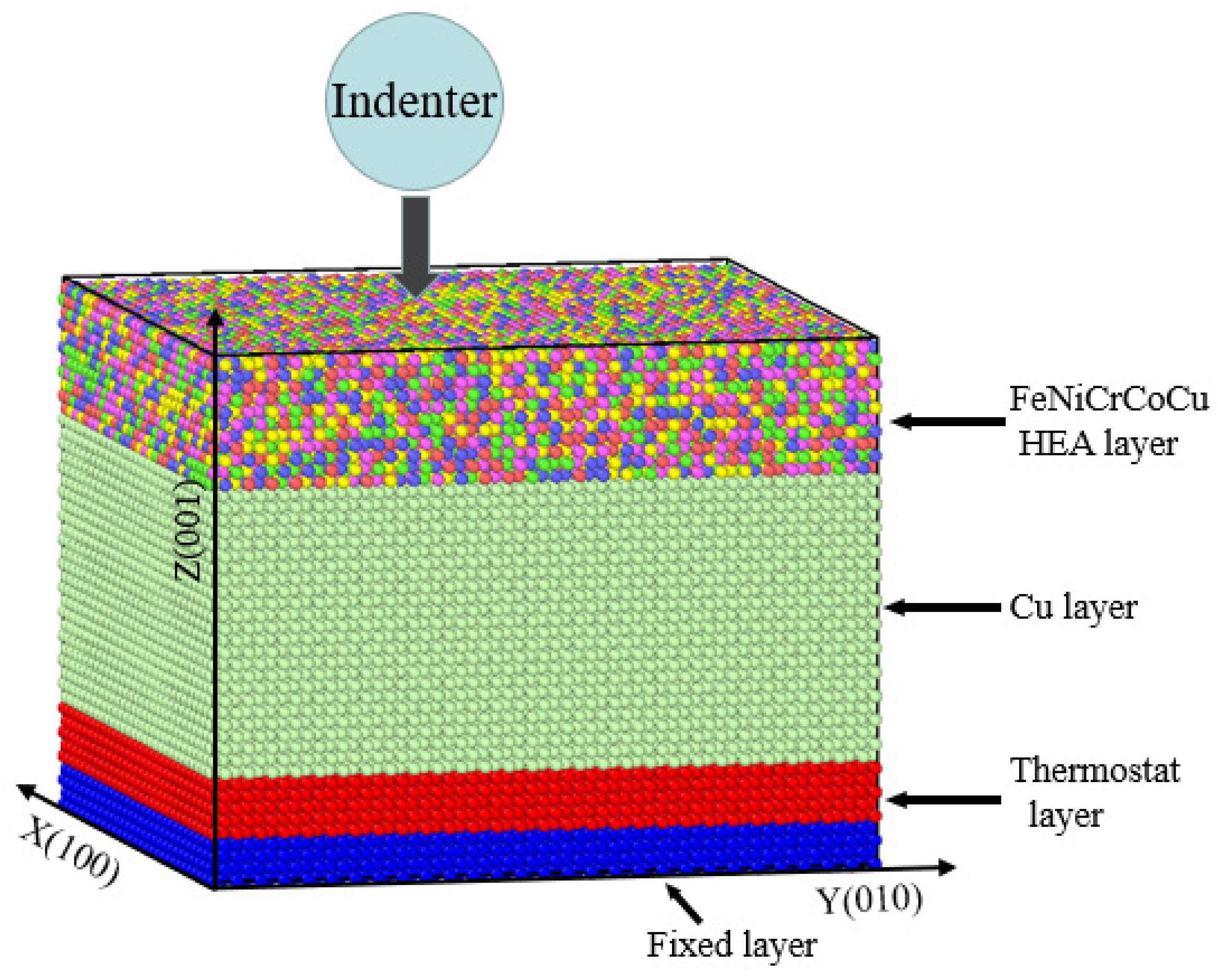

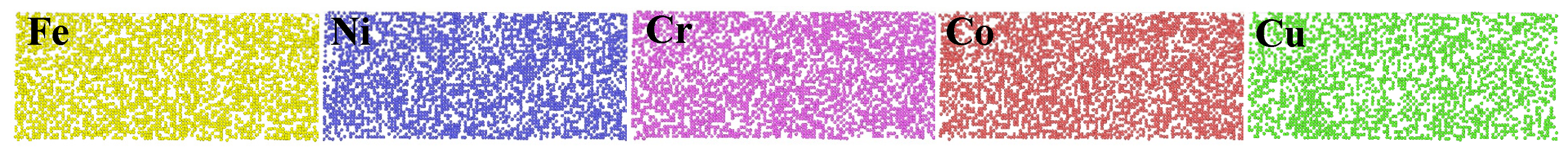

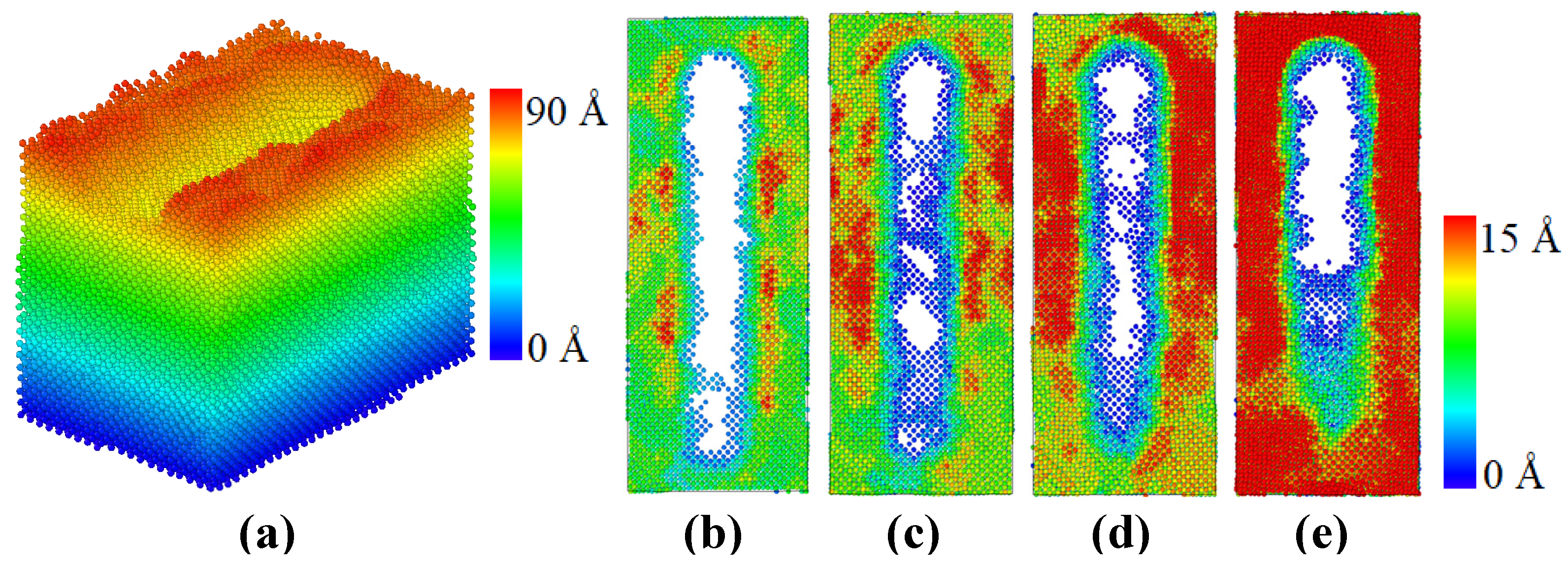

Figure 1 shows the final distribution of five elements Fe, Ni, Cr, CO and Cu in the high entropy alloy coating after the model reaches the equilibrium state.

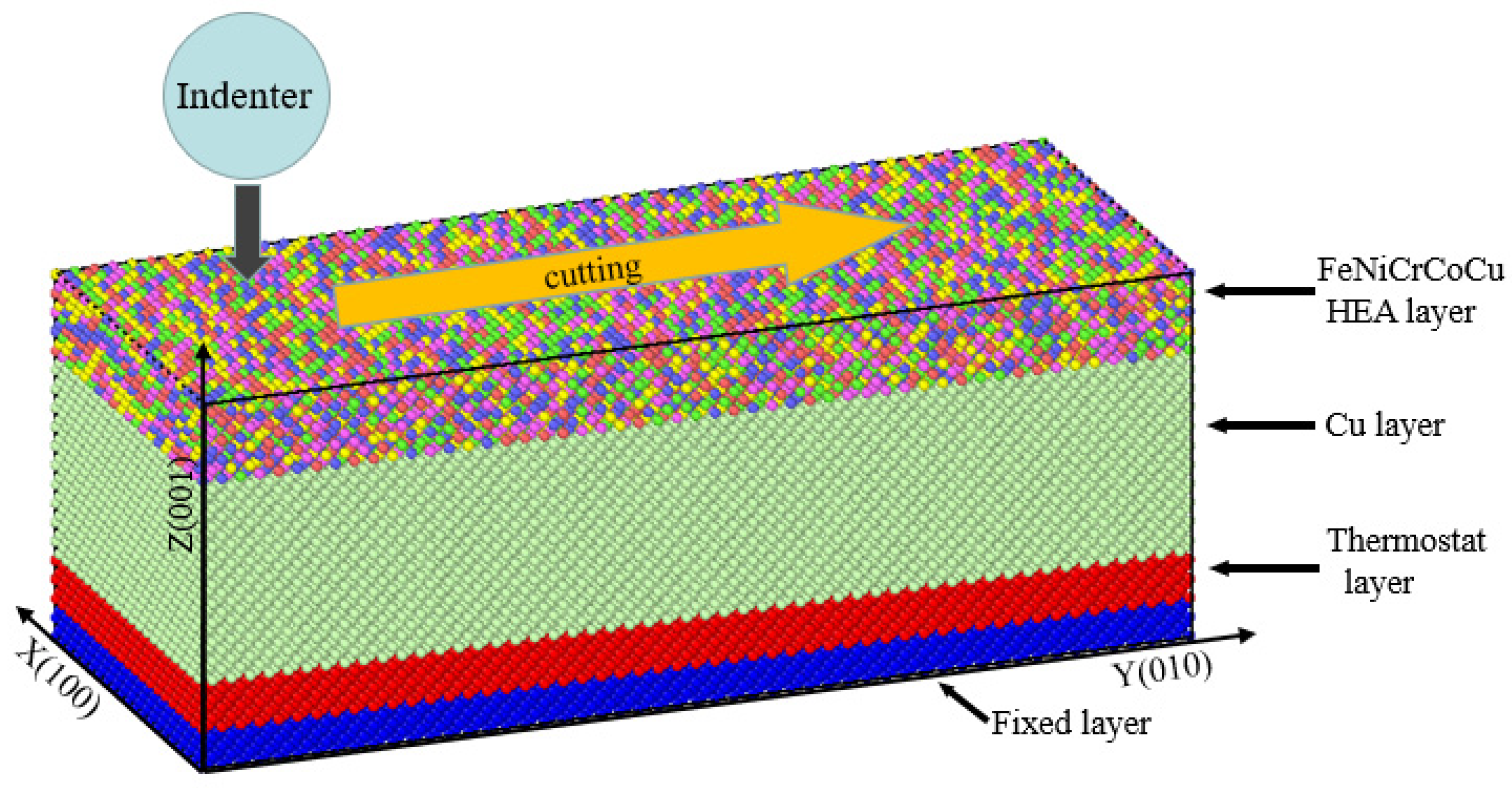

After the relaxation model reaches the equilibrium state, the atoms in the range of 0~5 Å, 5~10 Å and 10~52 Å in the Z direction were set as the fixed layer, thermostatic layer, Cu layer as shown in

Figure 2. The high entropy alloy coating was set as the high entropy alloy layer. The atoms in Cu layer and high entropy alloy layer were Newtonian layers with free moving atoms. The fixed layer was placed at the bottom of the model to avoid the movement in space. The thermostat layer consists of atoms adjacent to the fixed layer to maintain the temperature of the system constant. The simulation only works on the thermostat and Newtonian layers. Periodic boundary conditions are used in the X and Y directions of the model, and contractive boundary conditions are used in the Z direction. The atoms in the boundary layer were fixed as rigid bodies, and the Cu layer and high entropy alloy layer were set as NVE ensemble. The constant temperature layer was set as NVT ensemble, and the temperature was controlled at 300K. The initial position of the indenter was located above the matrix and pressed into the matrix at a speed of 10 m/s along the negative direction of the Z axis, with a depth of 10 Å, and then rubbed along the positive direction of the Y axis at a speed of 10 m/s, as shown in

Figure 2.

2.2. Nanoindentation Simulation

In the nanoindentation model, single crystal Cu was used as the matrix material and FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy was used as the coating material. The same lattice types of both materials were set. The model size of Cu matrix was 100Å×100Å×55Å, and the total number of atoms was 47111. The ambient temperature was also set at 300K, 600K, 900K and 1200K. The high entropy alloy coating was also set as 21Å. The substrate and coating adopt the same crystal orientation as above. In order to eliminate the unreasonable structure in the model, the conjugate gradient algorithm[

35] was used to minimize the energy, and then the model was relaxed. The relaxation process is consistent with the friction model above. The final distribution of five elements Fe, Ni, Cr, CO and Cu in the high entropy alloy coating reached the equilibrium state after the relaxation process.

After the model reached the equilibrium state, the atoms in the range of 0~5Å, 5~10Å and 10~55Å in the Z direction were set as the boundary layer, constant temperature layer and Cu layer, and the high entropy alloy coating is set as the high entropy alloy layer, as shown in Figure 4. Periodic boundary conditions were used in the X and Y directions of the model, and contractive boundary conditions were used in the Z direction. The atoms in the boundary layer were fixed as rigid bodies, and the Cu layer and high entropy alloy layer were set as NVE ensemble. The setting of constant temperature layer adopted Langevin method to control the temperature. The temperature was controlled as 300K, 600K, 900K and 1200K respectively. The bottom of the virtual indenter was contacted with the top of the simulation model, and there was no pressure. After the simulation position was determined, it started to press into the matrix material at the speed of 10 m/s. The loading process lasted for 300ps, and the pressing depth was 30Å. After that, the unloading started at the same speed as loading, and the unloading time lasted for 300ps.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of nanoindentation model area distribution.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of nanoindentation model area distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Force Displacement Curve

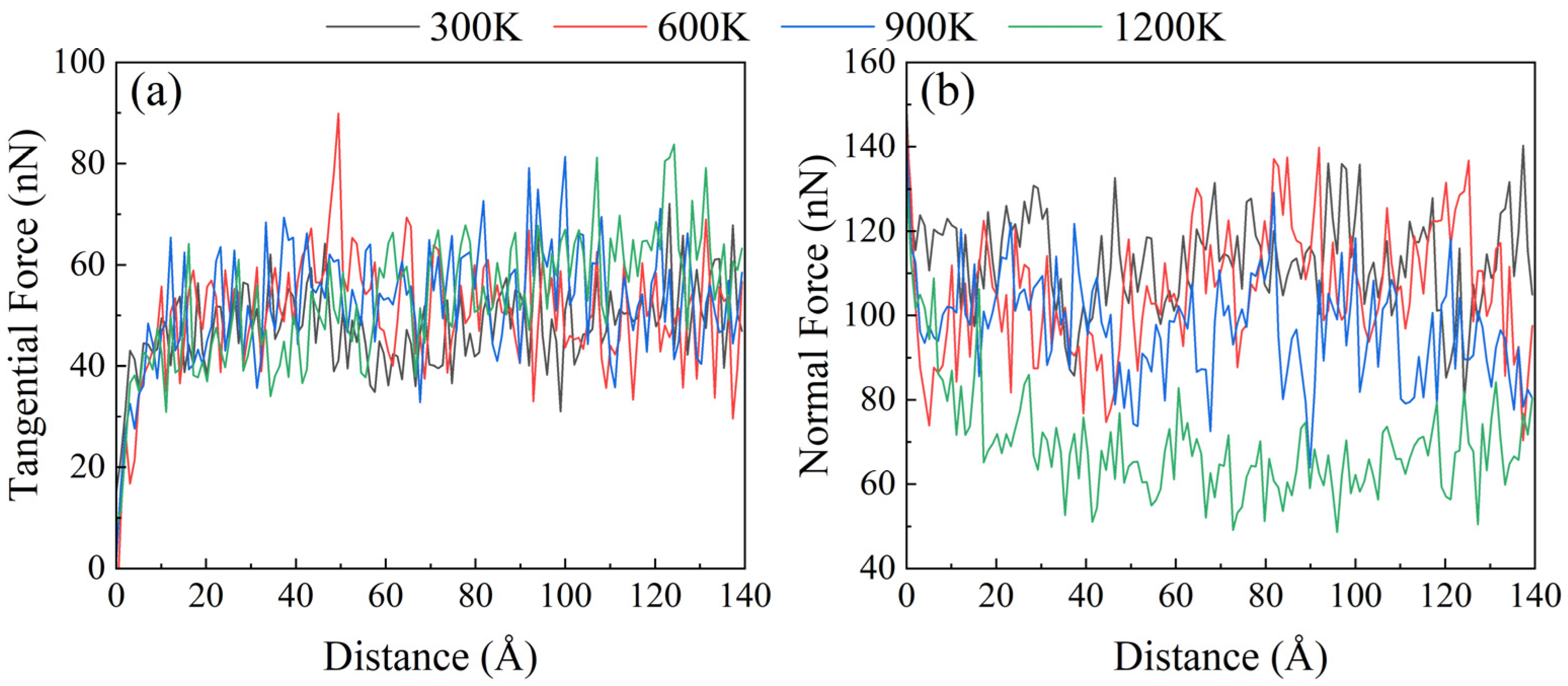

Four temperatures were designed for friction simulation. The change of tangential force during friction is shown in

Figure 4a, and the change of normal force is shown in

Figure 4b. With the increase of temperature, the tangential force has a slow increasing trend, and the variation range is small. The general difference between 300K and 1200K is about 20nN. After the temperature rises, the normal force significantly decreased. When the temperature increases from 300K to 900K, the normal force decreases slowly, the change value of the normal force decreases by about 20nN. When the temperature reaches 1200K, the change of normal force amplitude increases, and the value of the positive force decreases by about 40nN from that under 900K. It can be found from the force curve that FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy has excellent high temperature resistance at 300-900K.

The virtual indenter was also used to simulate nanoindentation. The force displacement curve in the unloading process was linearly fitted to the initial unloading position. The hardness and elastic modulus of the material were calculated using Oliver Pharr method [

39,

40]. During the virtual indenter pressing process, the pressure generated on the model was shown in

Figure 5. The material has gone through elastic deformation and plastic deformation at different temperatures, which was similar to the loading curve of traditional alloys. At 300K and 600K, the slope of the curve in the elastic stage is basically the same as that in the unloading process. At 900K and 1200K, the slope of the curve in the loading stage is higher than that in the unloading stage, indicating that the friction properties of the material have changed permanently in the friction process.

3.2. Effect of Temperature on Lattice Structure

Figure 6 shows the evolution of lattice structure in the friction process at different temperatures. At the temperature of 300K, a small amount of stacking faults appears at the position of the high entropy alloy coating during the friction process. The overall structure was very stable, consisting almost entirely of FCC crystal phase, and a little disordered structure appears on the coating surface. At the temperature of 600K, the coating material basically did not produce stacking faults after friction, but there was a small amount of stacking faults in the matrix material, and the overall structure was still very stable. When the temperature reached 900K, stacking faults across the interface between the two materials appeared, and disordered structures increased in the Cu matrix. At the temperature of 1200K, the lattice structure was still mostly FCC phase in high entropy alloy coating, and only a little disordered structure was increased. The stability of the lattice structure in the Cu matrix decreased greatly. During the friction process, a large number of disordered structures appeared and began to melt, and the stacking faults also began to decrease.

Figure 7 shows the simulation process of nanoindentation under different temperatures. The lattice structure changed during the loading process of the indenter. At the temperature of 300K, a small amount of stacking faults appeared in the high entropy alloy coating and Cu substrate during the indentation process. The overall structure was very stable, formed by FCC crystal phase, and a little disordered structure appeared on the coating surface. At the temperature of 600K, there was basically no stacking faults in coating material after friction, and a small amount of stacking faults appeared in the Cu matrix material, and the overall structure was still very stable. When the temperature reached 900K, stacking faults across the interface between the two materials appeared, and disordered structures increased in the Cu matrix. At the temperature of 1200K, there was mainly FCC crystal phase in high entropy alloy coating, and the disordered structure only increased slightly. The stability of the lattice structure in the Cu matrix became worse. During the pressing process, a large number of disordered structures appeared, the Cu matrix began to melt, and the stacking fault also began to decrease.

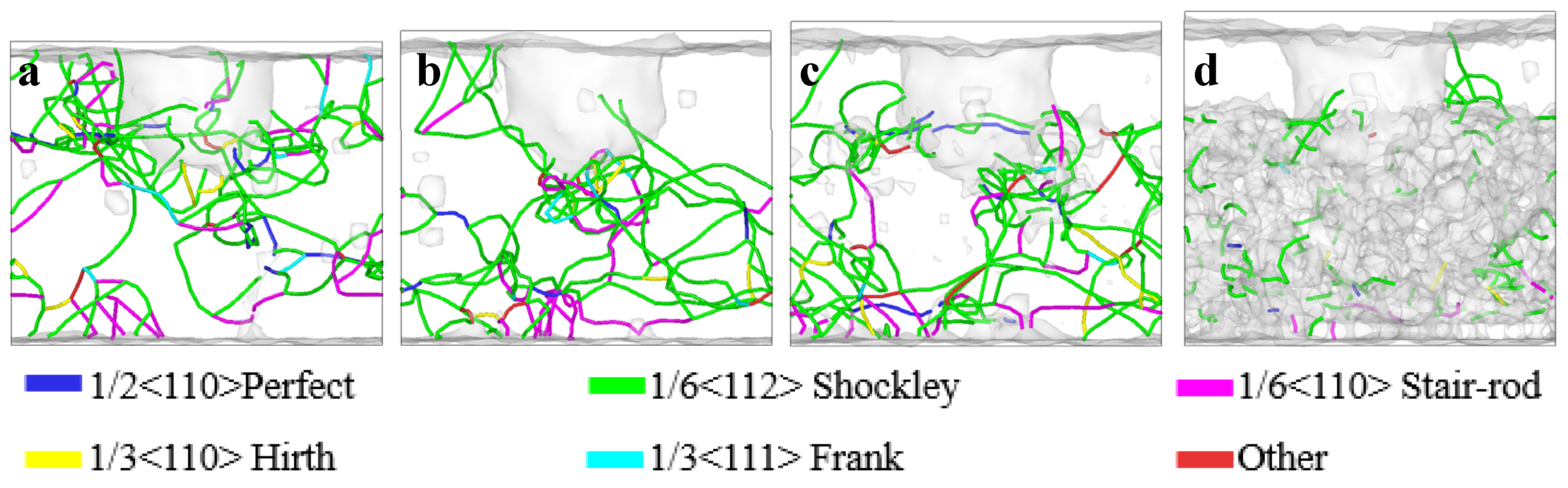

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Lattice Structure

Figure 8 shows the evolution of dislocation at four different temperatures in friction process. At the temperature of 300K, there was mainly Shockley incomplete dislocations at the initial indentation position and the middle region of the indenter in friction process. There was also a small number of stair rod incomplete dislocations were generated, connecting Shockley incomplete dislocations between different stacking faults. At the ambient temperature of 600K, the Shockley incomplete dislocation was mainly located at the initial indentation position of the indenter and the middle region in the friction process. Dislocation slip phenomenon began to appear in the friction process, and there was a reaction in the Shockley incomplete dislocation slip process in the two regions. At the temperature of 900K, the Shockley incomplete dislocation appeared in a large range along the y-axis direction from the initial pressing position and the middle region of the friction process, and the Shockley incomplete dislocation between different stacking faults was connected by the stair rod incomplete dislocation, which damaged the elastic recovery ability of the material. At the temperature of 1200K, the Shockley incomplete dislocation in the high entropy alloy coating and the Cu matrix appeared obvious delamination during the friction process, and a small amount of complete dislocation appeared on the contact surface of the two materials. The Shockley incomplete dislocation in the high entropy alloy coating was a continuous form of line defects continuity. However, there was a uniform dense distribution of short dislocations, and no longer a long dislocation line in the Cu matrix. This might be due to a large number of surface defects in the Cu matrix under the high temperature environment, which hindered the generation of line defect dislocation.

Figure 9 shows the evolution of dislocation at four temperatures in nanoindentation process. After the indentation depth of 10Å, the dislocations mainly appeared in one side at the temperatures of 300K, 600K and 900K. The length of the dislocation line was the smallest, and the deformation recovery ability of the material was enhanced at the temperature of 600K. During the loading process of the indenter, the Shockley incomplete dislocation appeared sliding phenomenon, moving from one side to the other side, and finally existed in the whole matrix at the end of the loading. At the temperature of 1200K, the Shockley incomplete dislocations in the high entropy alloy coating and the Cu matrix appeared obvious delamination phenomenon during the loading process. When the indentation depth was 20Å, the Shockley incomplete dislocations were continuous line defects in the high entropy alloy coating. However, in the Cu matrix, there were uniformly distributed short dislocations, and no longer dislocation lines. When the indentation depth was 30Å, there were a small number of segment dislocations in the matrix material. It might be due to the damage of the contact surface caused by the penetration of the coating into the matrix under the pressure of the indenter at high temperature. This damage could result in a large number of surface defects in the matrix, which hindered the generation of dislocations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Temperature on Morphology and Friction Coefficient

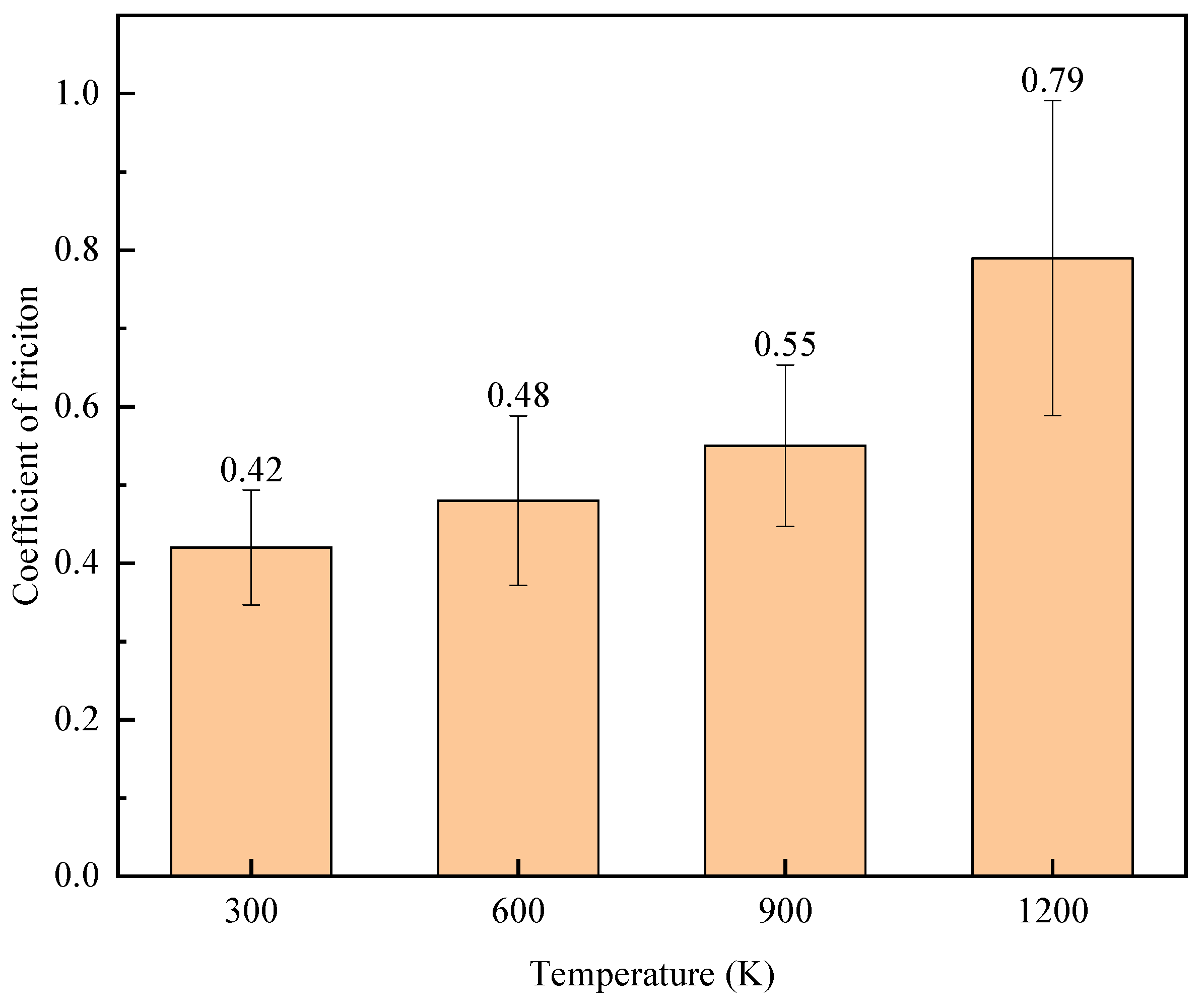

Figure 10 shows the atomic wear morphology on the material surface after friction simulation at four temperatures. With the increase of temperature, it can be seen that the wear degree of coating increases obviously.

The friction coefficients of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy coating material at 300K, 600K, 900K and 1200K were obtained by using Amontons Coulomb friction law [

41,

42]. As shown in

Figure 11, the effect of temperature on its friction coefficient was analyzed. With the increase of temperature, the friction coefficients gradually increased, and the fluctuation range also continued to increase. When the temperature rises from 900K to 1200K, there was a large increase, and the fluctuation was more intense. This was because the temperature was close to the melting point of the Cu matrix material, resulting in a significant decrease in the hardness of the material and a significant decrease in the value of the positive force. However, the high entropy alloy material was relatively stable at this temperature. The friction depth of the indenter was less than the thickness of the high entropy alloy coating, and the value of the tangential force in the friction process was basically stable, resulting in a significant increase in the friction coefficient of the material. The friction coefficient data was also basically consistent with 0.5~0.75 measured by Li et al. in the experiments [

43].

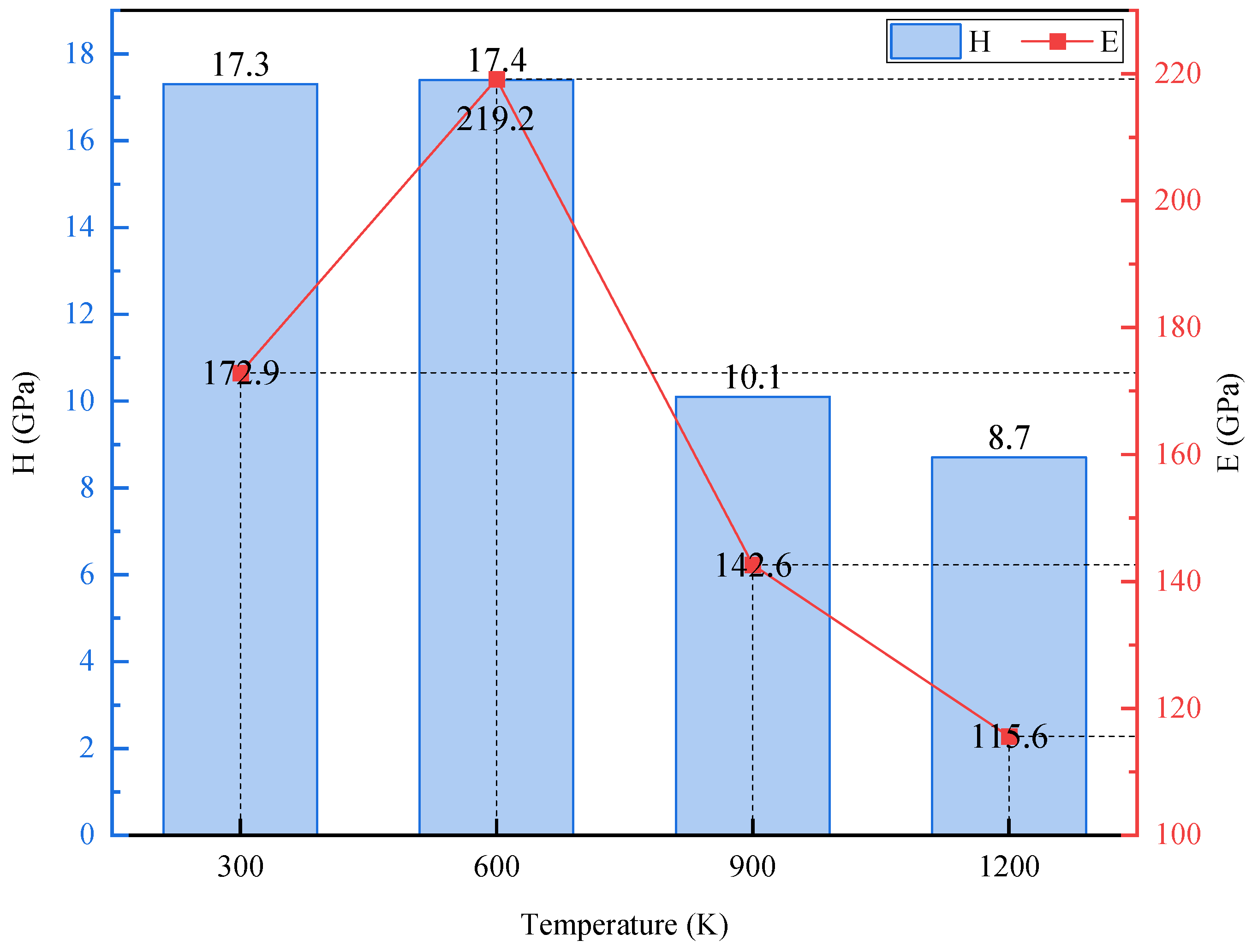

4.2. Effect of Temperature on Elastic Modulus and Hardness

The change of ambient temperature would have a great impact on the hardness and elastic modulus of the material. In

Figure 5, the change of the positive force under different temperature environments could be seen intuitively. Oliver Pharr method [

39,

40] was used to calculate hardness and elastic modulus. The calculation expression of O-P method is as follows[

39,

40]:

where

hc is the contact depth;

h is the maximum indentation depth;

P is the corresponding load of

h;

S is the slope of the unloading curve;

ε is the correction coefficient. Tan used O-P method and nanoindentation technology to carry out the experiment, and the result was reliable when

ε was 0.75 [

44].

where

C1、

C2、…、

C8 are the correction constants.

H is Rockwell hardness;

Er is the reduced elastic modulus;

v、vi are the Poisson’s ratio of matrix material and indenter, respectively;

E、

Ei are the elastic modulus of coating material and indenter respectively. Since the virtual indenter used in this paper is loaded, the elastic modulus can be taken as infinity, so equation (6) could be simplified as:

According to the loading curve in

Figure 5 and the fitting curve in the unloading process, the Poisson’s ratio of similar materials was about 0.32 [

45], and the data shown in

Table 1 could be obtained. The hardness and elastic modulus corresponding to each model obtained after calculation was as shown in

Figure 12.

As shown in

Figure 12, the hardness is basically the same at 300K and 600K. When the temperature raised to 900K, there was a large decrease from 17.4GPa to 10.2GPa. When the temperature raised from 900K to 1200K, the hardness decreases slightly, from 10.2GPa to 8.6GPa. When the temperature increased from 300K to 600K, the elastic modulus increased significantly, from 173GPa to 219GPa. As the temperature continues to rise, the elastic modulus began to decline rapidly, which was also consistent with the slope change during the unloading pressure process. At low temperature, the high entropy alloy coating material has higher hardness, elastic modulus and better wear resistance. In the high temperature environment, the hardness decreases significantly, and the friction performance of the material also decreases continuously, which is easier to be destroyed in the friction process. Luo et al. [

46] obtained the elastic modulus of 201GPA and hardness of 17.2GPA of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy at 293K, which is very close to the simulation results at 300K in our work. And the results are also basically consistent with the results obtained by Deng et al. [

47] in the experiment.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the wear resistance of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy coating material was comprehensively analyzed by molecular dynamics method. The effects of temperature on lattice structure, dislocation, friction coefficient and hardness of high entropy alloy coating material were analyzed. Through the above research and analysis, the following conclusions are obtained:

(1) In the friction process of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy coating, with the increase of temperature, the value of the normal force decreases greatly due to thermal softening. High temperature leads to the increase of the proportion of disordered atoms in the material, and the linear density of dislocations is also larger.

(2) At 300K and 600K, the ordered lattice structure of the high entropy alloy coating material is basically the same, and their hardness is basically the same. But the dislocation linear density at 600K is significantly reduced compared with that at 300K, resulting in the increase of the elastic modulus of the material from 173GPa to 219GPa. At the temperatures of 900K and 1200K, the proportion of disordered lattice structure increases rapidly, and the linear density of dislocation also decreases significantly, resulting in a significant decrease in the hardness and elastic modulus of the material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and Y.D.; methodology, X.Z.; software, X.Z. and Z.Y.; validation, X.Z. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, X.Z. and Z.Y.; investigation, Y.D.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, X.Z. and Y.D.; supervision, X.Z. and Y.D.; project administration, X.Z. and Y.D.; funding acquisition, X.Z. and Y.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant number 12002223 and12102354], the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST [grant number 2022QNRC001], the National Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province under Grant no. A2020210035, the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation [2024A1515012018].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Qiu, Y.; Thomas, S.; Gibson, M.A.; Fraser, H.L.; Birbilis, N. Corrosion of high entropy alloys. npj Mat. Degrad. 2017, 1, 41529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wardini, J.L.; MacDonald, B.E.; Wen, H.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Rupert, T.J.; Chen, W.; Lavernia, E.J. A high-entropy alloy with hierarchical nanoprecipitates and ultrahigh strength. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, 8712–8712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.H.; Pan, Z.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Luo, H.; Li, X. Corrosion-resistant high-entropy alloy coatings: A Review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Han, J.; Su, B.; Li, P.; Meng, J. Microstructure, mechanical properties and tribological performance of CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy matrix self-lubricating composite. Mater. Design 2017, 114, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Lan, L.; Zhu, S.; Yang, H.J.; Shi, X.H.; Liaw, P.K.; Qiao, J. Effects of temperature on the tribological behavior of Al0.25CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, M.H.; Tsai M., H.; Wang, W.R.; Lin, S.J.; Yeh, J.W. Microstructure and wear behavior of AlxCo1.5CrFeNi1.5Tiy high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 6308–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Qin, R.; Chen, P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, L. An Atomic Insight into the Stoichiometry Effect on the Tribological Behaviors of CrCoNi Medium-Entropy Alloy. SSRN Electronic J. 2022, 2022 593, 153391. [Google Scholar]

- Doan, D.Q.; Nguyen, V.H.; Tran, T.V.; Hoàng, M.T. Atomic-scale analysis of mechanical and wear characteristics of AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy coating on Ni substrate. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 85, 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Yang, R.; Gao, Q.; Li, J.; Xue, H.; Lu, X.; Tang, F. Atomistic simulation of tribology behaviors of Ti-based FeCoNiTi high entropy alloy coating during nanoscratching. SSRN Electronic J. 2023, 213, 112124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Komarasamy, M.; Gwalani, B.; Shukla, S.; Mishra, R.S. Fatigue behavior of ultrafine grained triplex Al0.3CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. Scripta Mater. 2019, 2019 158, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Fu, R.D; Li, Y.; Sang, D.L. Effects of nitrogen alloying and friction stir processing on the microstructures and mechanical properties of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Comp. 2020, 822, 153512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, S.; Shen, X.; Du, C.; Zhao, J.; Sun, B.R.; Xue, H.; Yang, T.; Cai, X.; Shen, T. Bulk nanocrystalline boron-doped VNbMoTaW high entropy alloys with ultrahigh strength, hardness, and resistivity. J. Alloys Comp. 2021, 853, 155995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, N.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, L.J.; Xiang, H.F. Microstructure stability and oxidation behaviour of (FeCoNiMo)90(Al/Cr)10 high-entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Cai, Z.; Guan, Y.; Cui, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Dong, M.; Zhang, D. High temperature wear performance of laser-cladded FeNiCoAlCu high-entropy alloy coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 445, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.P.; Huai, L.L.; Jia, J.F; Zhou, W.; Yang, Y.; Ren, X. Laser additive manufacturing of CrMnFeCoNi high entropy alloy: Microstructural evolution, high-temperature oxidation behavior and mechanism. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020, 130, 106326. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Guo, W.; Fu, Y. High-entropy alloys: emerging materials for advanced functional applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 663–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruestes, C.J.; Farkas, D. Dislocation emission and propagation under a nano-indenter in a model high entropy alloy. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2022, 205, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; He, T.; Feng, M. The effect of Cu and Mn elements on the mechanical properties of single-crystal CoCrFeNi-based high-entropy alloy under nanoindentation. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 195104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplanche, G.; Gadaud, P.; Bärsch, C.; Demtröder, K.; Reinhart, C.; Schreuer, J.; George, E.P. Elastic moduli and thermal expansion coefficients of medium-entropy subsystems of the CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Comp. 2018, 746, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Li, T.; Chang, X.X.; Lu, Y.; Yin, G.; Cao, Z.; Li, T. A novel Co-free Al0.75CrFeNi eutectic high entropy alloy with superior mechanical properties. J. Alloys Comp. 2022, 902, 163814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, M.; Li, D.; Yong, Z.; Liaw, P.K.; Lewandowski, J.J. Fracture toughness and fatigue crack growth behavior of as-cast high-entropy alloys. JOM 2015, 67, 2288–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braic, V.; Balaceanu, M.; Braic, M.; Vlădescu, A.; Panseri, S.; Russo, A. Characterization of multi-principal-element (TiZrNbHfTa)N and (TiZrNbHfTa)C coatings for biomedical applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2012, 10, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Dong, L.; Dong, X.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Xiong, J.; Xu, C. Study on wear behavior of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy coating on Cu substrate based on molecular dynamics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 570, 151236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Sagar, S.; Dube, T.; Kim B., G.; Jung Y., G.; Koo, D.D.; Jones, A.; Zhang, J. Molecular dynamics modeling of mechanical and tribological properties of additively manufactured AlCoCrFe high entropy alloy coating on aluminum substrate. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 263, 124341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.X.; Fang, T.H.; Lee, C.I. Deformation and machining mechanism of nanocrystalline NiCoCrFe high entropy alloys. J. Alloys Comp. 2022, 924, 166525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Yi, M.; Li, J.; B Liu. ; Huang Z. Deformation behaviors of Cu29Zr32Ti15Al5Ni19 high entropy bulk metallic glass during nanoindentation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 443, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Fang, F. On the mechanism of material removal in nanometric cutting of metallic glass. Appl. Phys. A 2014, 116, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruestes, C.J.; Bringa, E.M.; Gao, Y.; Urbassek, H.M. Molecular dynamics modeling of nanoindentation. Appl. Nanoindentation Adv. Mater. 2017, 313–345. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.H.; Weng, C.I.; Chang, J.G. Molecular dynamics analysis of temperature effects on nanoindentation measurement. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2003; 357, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.H.; Wu, J.-H. Molecular dynamics simulations on nanoindentation mechanisms of multilayered films. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, S.; Lu, S.; Zhang, B.; Bao, C.; Kan, Q.; Kang, G.; Zhang, X. Effects of high entropy and twin boundary on the nanoindentation of CoCrNiFeMn high-entropy alloy: A molecular dynamics study. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2021, 195, 110495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Fang, Q.; Li, J. Molecular dynamics simulations for nanoindentation response of nanotwinned FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 465701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Hou, H.; Pan, Y.; Pei, X.; Song, Z.; Liaw, P.K.; Zhao, Y. Hardening-softening of Al0.3CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy under nanoindentation. Mater. Design, 2023; 231, 112050. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Li, Q. Molecular dynamics study on the dislocation evolution mechanism of temperature effect in nano indentation of FeCoCrCuNi high-entropy alloy. Mater. Technol. 2024, 39, 2299903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippo, L.; Lucidi, S. A globally convergent version of the Polak-Ribière conjugate gradient method. Math. Program. 1997, 78, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosé, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyna, G.J.; Tobias, D.J.; Klein, M.L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 4177–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, W.; Shiga, M.; Mikami, M. Rapid estimation of elastic constants by molecular dynamics simulation under constant stress. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 134103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulomb, C.A. Théorie des machines simples, en ayant égard au frottement de leurs parties, et à la roideur des cordages. Bachelier, Paris, 1821. [Google Scholar]

- Popova, E.; Popov, V.L. The research works of Coulomb and Amontons and generalized laws of friction. Friction 2015, 3, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, Y. Microhardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance of AlxCrFeCoNiCu high-entropy alloy coatings on aluminum by laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.X. Calculation of hardness indentation depth relationship and elastic modulus using nanoindentation loading curve (in Chinese). J. Metals 2005, 10, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.F.; Wang, X.D.; Cao, Q.P.; Zhao, G.H.; Li, J.X.; Zhang, D.X.; Zhu, J.J.; Jiang, J.Z. Microstructure characterization of AlxCo1Cr1Cu1Fe1Ni1 (x=0 and 2.5) high-entropy alloy films. J, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.; Li, L.; Fang, Q.; Li, J.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Peng, J.; Liaw, P.K. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of FeCoCrNiCu high entropy alloys: a microstructure-based constitutive model and a molecular dynamics simulation study. Appl. Math. Mechan. 2021, 42, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Chawla, N.; Chawla, K.K.; Koopman, M.C.; Chu, J.P. Mechanical Behavior of Multilayered Nanoscale Metal-Ceramic Composites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2005, 7, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).