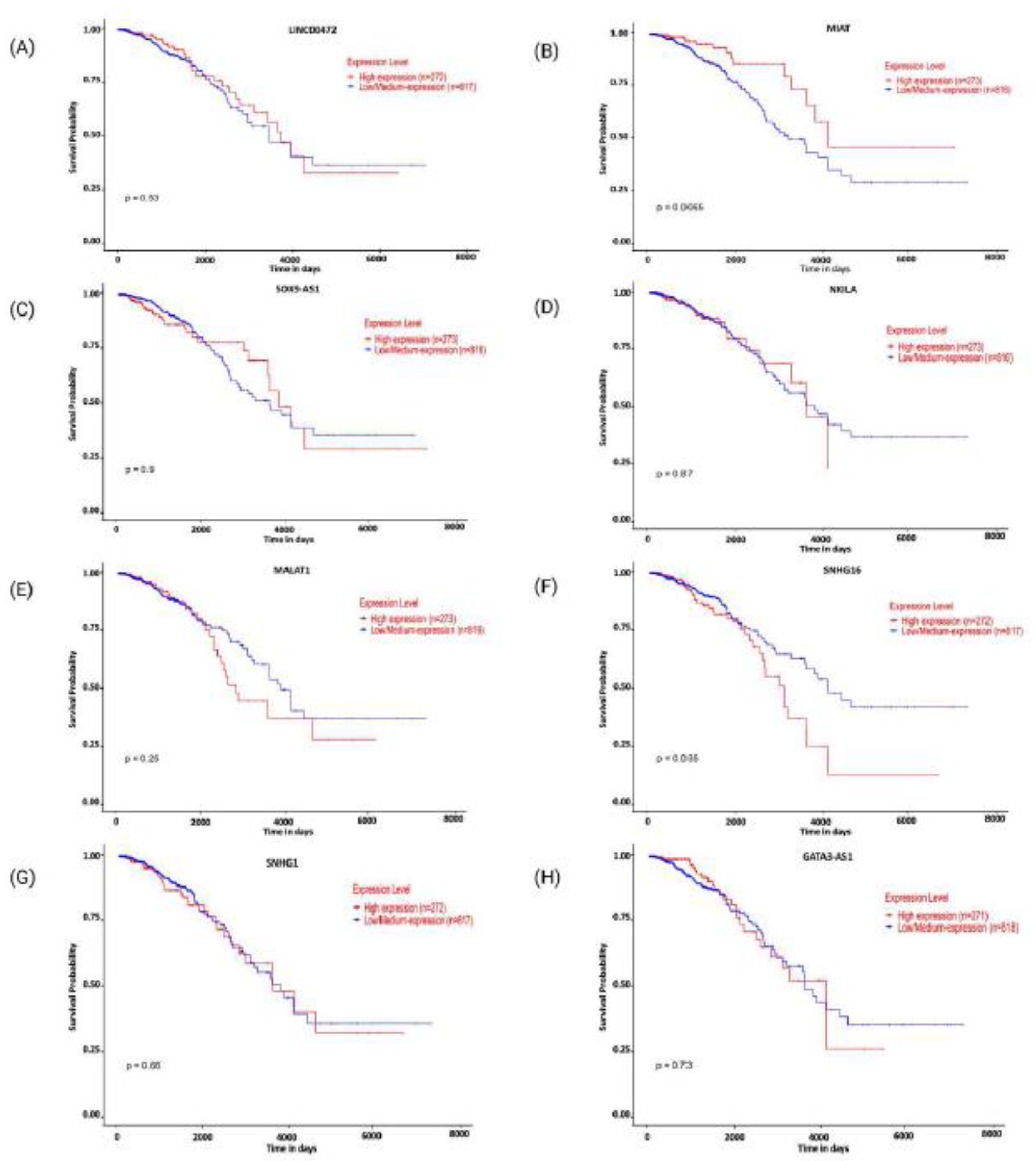

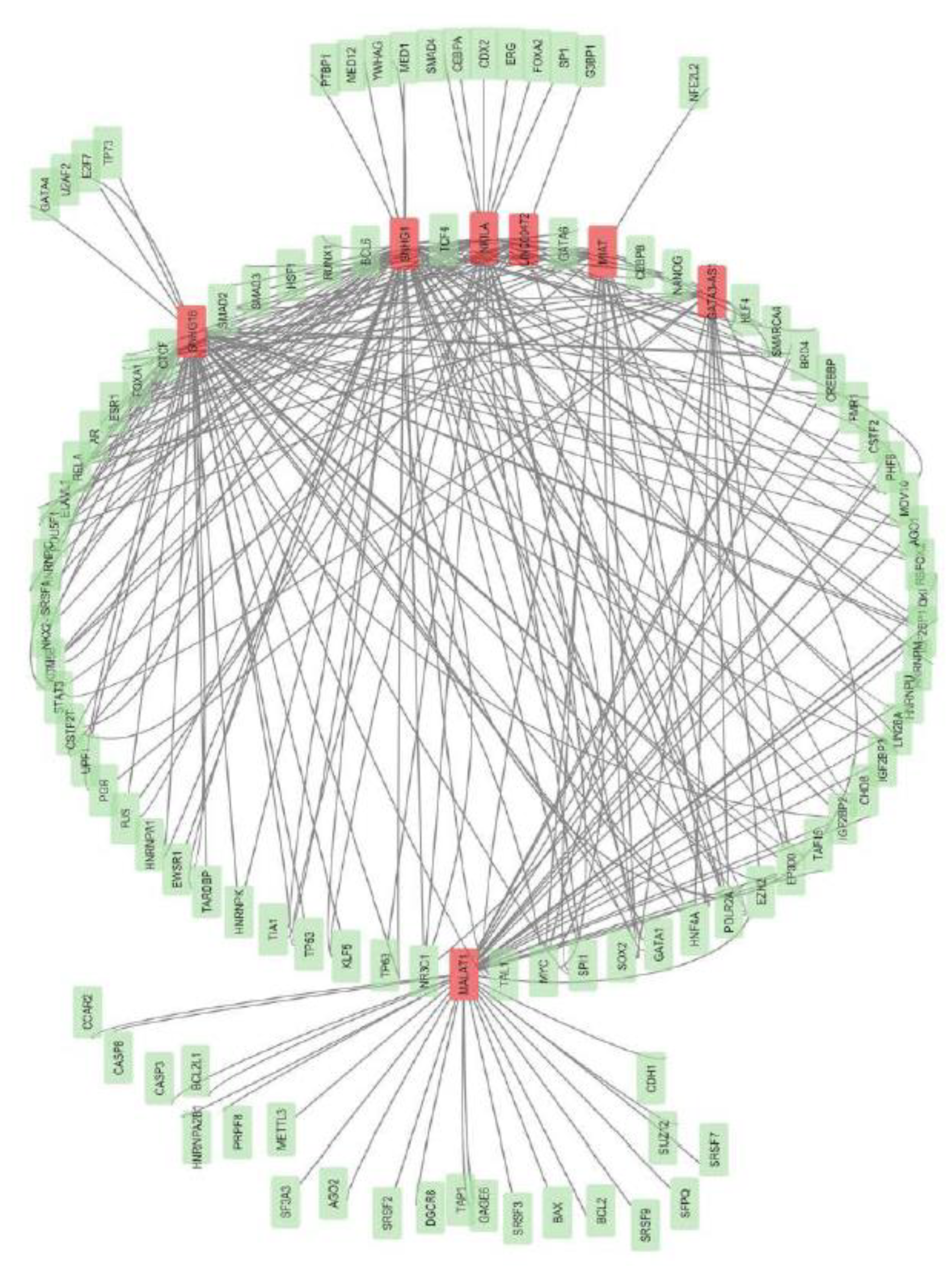

2. Modulatory Functions of lncRNAs in Shaping T-Cell Infiltration Within Breast Cancer

The innate and adaptive immune systems are critical contributors to tumor immunosurveillance and modulation of cancer progression. Immune cells, such as T-cells, natural killer cells, B-cells, or macrophages that travel from the blood circulation and accumulate in the tumor microenvironment, particularly in the tumor stroma and intraepithelial region, are termed tumor-infiltrating immune cells (

Figure 1). As key mediators of anti-tumor immune response, the presence and abundance of these immune-infiltrating cells are often associated with therapeutic efficacy and overall patient survival. T cells are identified using specific cell surface markers among these infiltrating cells. CD3+ is a general marker for each T cell, whereas CD4+ and CD8+ T cell markers reflect the distribution of T helper (Th) and cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTL), respectively [

24,

25]. Cytotoxic T cells aid in anti-tumor activity by secreting perforin and granzyme that induce cell death. T-helper 1 (Th1) promotes the activation of macrophages to target tumor cells by secreting IFN-ɤ (Interferon gamma), IL-2 (Interleukin 2), and TNF-α (Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha), while Th2 (T helper 2) promotes tumor cell proliferation. T cells can differentiate into immunosuppressive T regulatory (Treg) cells in the tumor microenvironment. They promote tumor growth through multiple mechanisms by suppressing the anti-tumor activity of various immune effector cells, including CD4+ T cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells [

15].

Long non-coding RNA has been implicated in regulating Treg cells' differentiation and functional activity. Although the concentration of T cells in the breast cancer tumor microenvironment is low, studies have revealed a notable level of T cell infiltration [

26]. TIMER (Tumor Immune Estimation Resource) was used to analyze the abundance of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs). T cell infiltration in tumors is highly variable, not only between different types of cancer but also among tumors of the same type. Compared with Luminal A and B subtypes of breast cancer, HER2+ and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) tumors typically show higher levels of T cell infiltration [

26]. LncRNA

TCL6 expression was strongly associated with increased infiltration of various immune cells, including B cells, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells, with all correlations being statistically significant (P<0.001) in breast cancer [

27]

(Figure 1).

In a recent study, Yang et al. [

28] evaluated the immune-related long non-coding RNAs (irlncRNAs) within the tumor microenvironment (TME) of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients. To classify TNBC tumors based on their immune landscapes, they analysed immune cell infiltration (ICI), PD-L1 expression, and tumor mutational burden (TMB) using bioinformatics tools TCGA-TNBC and datasets GSE33926. The authors revealed that tumors with high ICI showed increased PD-L1 expression and improved overall survival (OS) despite exhibiting lower TMB. In contrast, a higher TMB was linked to better survival outcomes in the low-ICI group, indicating that significant immune infiltration may weaken reliance on TMB for responses to immunotherapy.

Additional immune profiling revealed that high-ICI tumors have many immunostimulatory cells, including CD8+ T cells, activated memory CD4+ T cells, plasma B cells, M1 macrophages, NK cells (Natural killer cells), and dendritic cells. This means the tumor microenvironment is "hot" for the immune system. On the contrary, low-ICI tumors contained additional immunosuppressive cells like M2 macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils. This distinction shows the intricate relationship between the TME in triple-negative breast cancer, angiogenesis, and resistance to therapy.

To effectively stratify patients into high-risk groups, the authors, by applying LASSO-Cox regression analysis, developed a 13-irlncRNAs (Immune-related long non-coding RNA) prognostic signature. These high-risk group patients exhibited poorer overall survival (p<0.001) and displayed immunosuppressive infiltration with increased plasma B cells, M2 macrophages, and neutrophils, along with diminished PD-L1 expression. A significant association between the expression of irlncRNAs and the infiltration of immune cells like CD8+ T cells, B cells, and macrophages was also demonstrated in this study. Elevated CD8+ T cells and M1 macrophages were associated with improved overall survival (p≈0.04). This suggests that irlncRNAs may play a role in identifying immune-cold, treatment-resistant tumors. Among the 13 irlncRNAs investigated,

LINC00472 has been recognized as a tumor suppressor and a predictive marker in breast cancer [

29].

The

LINC00472 is located on chromosome 6q13, with 2,933 base pairs in length [

30]. High expression levels of

LINC00472 correlate with ER+ (Estrogen receptor-positive), low-grade breast cancer, and favourable molecular subtypes [

31]. Furthermore, experimental cell studies have confirmed that

LINC00472 inhibits the phosphorylation of NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa B) by binding to IKKβ (Inhibitor of Nuclear Factor Kappa B Kinase Subunit Beta) in breast cancer [

32]. Moreover, chemoresistant breast cancer cells also display increased levels of lncRNA

LINC00839, whose overexpression promotes the cancer-related pathway mediated by PI3K/AKT and Myc (myelocytomatosis oncogene) activation. Ultimately, this enhances cell invasion, migration, and proliferation, resulting in worse prognoses for breast cancer [

33]. This study provided a detailed and thorough assessment of the tumor microenvironment in TNBC by combining ICI (Immune cell infiltration), PD-L1, TMB (Tumor mutational burden), and irlncRNAs: the ICI score and the irlncRNA signature direct precision immunotherapy and patient stratification in TNBC.

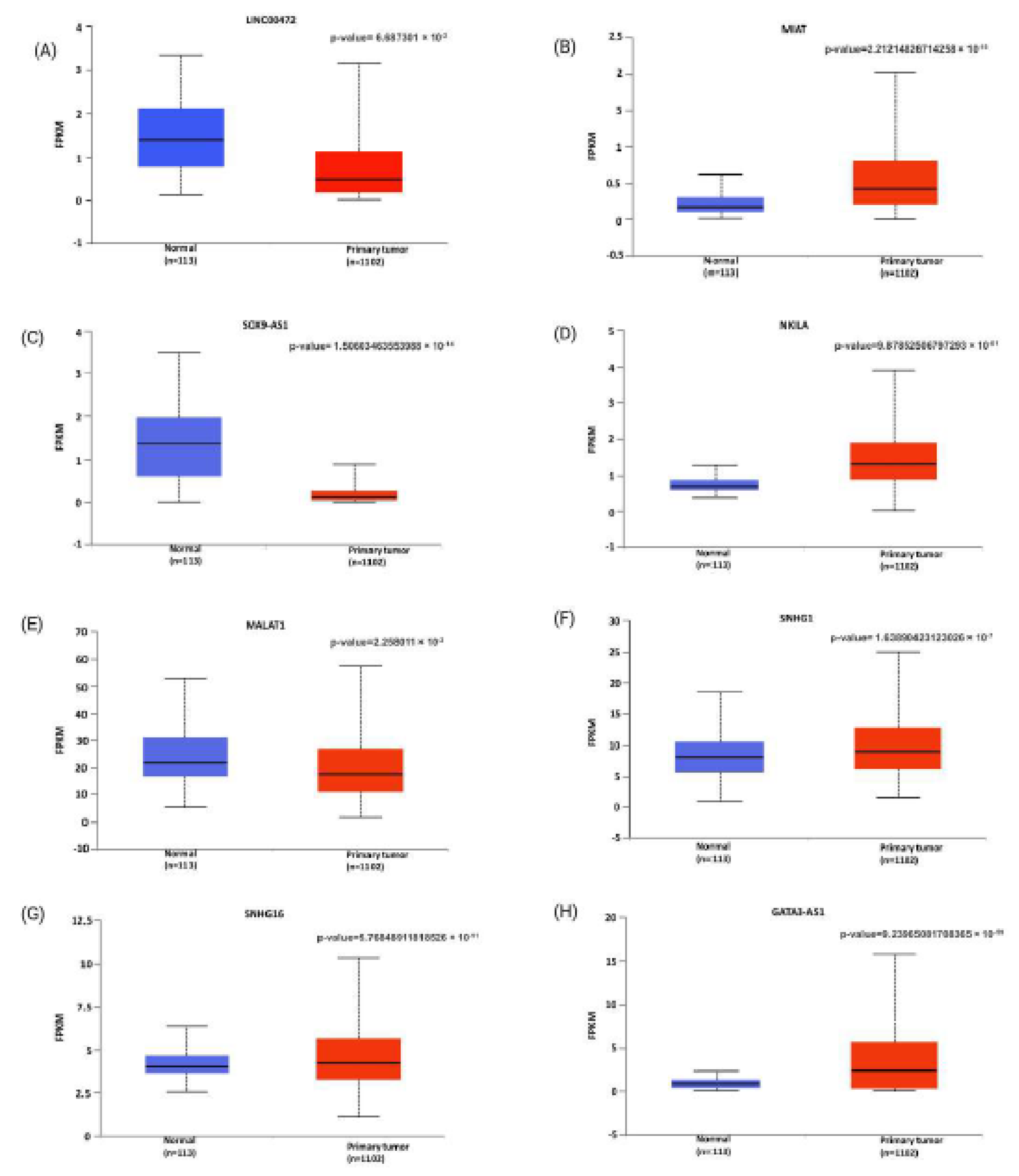

It has been observed that the long non-coding RNA

MIAT (Myocardial Infarction Associated Transcript) has aberrant regulation in several kinds of cancers, such as stomach, cervical, lung, liver, and prostate [

34]. In these types of cancers, it promotes tumor growth in several ways, particularly by functioning as an miRNA sponge [

35]. It is observed that

MIAT mainly exists in the nucleus and encompasses about 30 kilobases on chromosome 22q12.1 [

36]. Further, it involves significant biological processes involving oncogenesis, immune regulation, and alternative cell transcription [

36]. Elevated

MIAT levels compared to adjacent tissue are considered a promising non-invasive breast carcinoma diagnostic biomarker [

37]. Moreover, upregulated

MIAT levels are positively associated with lymph node metastasis and advanced TNM staging, and show strong diagnostic potential, with an AUC (Area under curve) of 0.832, a sensitivity of 75.7%, and a specificity of 85.0 % in ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) curve analysis [

38]. The authors employed bioinformatics analyses further to elucidate

MIAT's involvement in the tumor microenvironment, focusing particularly on immune cell infiltration, including T cell subtypes. The study showed that higher

MIAT expression in breast tumors is linked to more CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, activating as well as resting CD4+ memory T cells, γδ T cells, and M1-polarized macrophages (

Figure 1). In contrast, tumors with high

MIAT expression had lower levels of plasma cells, activated NK cells, monocytes, M2 macrophages, and activated mast cells. This unique immune cell profile suggests that

MIAT may influence the tumor immune microenvironment by encouraging the infiltration of specific T cell subsets and pro-inflammatory macrophages while reducing immune surveillance and regulatory elements. This may lead to a biased immune response. Previous studies have suggested CD8+ T cells as a prognostically favorable factor of immunotherapy in breast cancer cases [

39,

40]. The pathway enrichment analysis showed that the genes co-expressed with

MIAT significantly participate in several immune processes. These include T cell receptor (TCR) signaling, T helper cell differentiation (Th1, Th2, and Th17), cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, and primary immunodeficiency.

Moreover,

MIAT expression positively correlates with important immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4, along with other factors that regulate the immune system. This indicates that tumors with high

MIAT expression may use immune checkpoint pathways to weaken T-cell responses and avoid being detected by the immune system. Functional validation experiments confirmed these bioinformatic findings. Silencing

MIAT in TNBC cell lines significantly reduced cell proliferation, colony formation, and invasiveness. It also triggered apoptosis in both in vitro and xenograft models. Mechanistically

, MIAT was shown to act as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) by sponging miR-150-5p, thereby preventing this miRNA from downregulating CD274, the gene encoding PD-L1 [

19] (

Figure 2D). miR-150-5p, a miRNA on chromosome 19q13, is highly expressed in TNBC. Its expression levels are associated with tumor grade, patient survival, ethnicity, and regulation of several cancer driver genes [

41].

MIAT's distinct impact on tumor growth and immune modulation is supported by its indirect contribution to PD-L1 upregulation, a mechanism that has also been documented for other oncogenic lncRNAs such as

HCP5 (Histocompatibility leukocyte antigen complex P5). Together, these results show that

MIAT significantly affects the immune microenvironment in breast cancer. It connects to both tumor growth and immune evasion. The study highlights that targeting

MIAT could improve anti-tumor immune responses and change the tumor microenvironment, mainly when used with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Additionally,

MIAT could serve as a valuable biomarker with strong clinical importance for breast cancer patients.

A similar study by Luan et. al further validated

MIAT`s role in breast cancer progression. MIAT functions as ceRNA to miR-155-5p also through its conserved binding sites. This miR-155-5p sponging was found to modulate the expression profile of DUSP7 (dual specificity phosphatase 7). DUSP7 is a diverse family of protein phosphatases that target both phosphotyrosine and phosphoserine/ phosphothreonine within the same substrate. Reduced expression of DUSP7 is often associated with several cancers, suggesting its tumor suppressive roles. In a separate study by Li et. al [

42]

, drug resistance was induced in breast cancer by FOSL1 through DUSP7-mediated dephosphorylation of PEA15 (Proliferation and apoptosis adaptor protein 15). Luan et. al also correlated knockdown of

MIAT in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines with decreased epithelial to mesenchymal transitions, increased apoptosis, thereby inhibiting breast cancer migration and invasion [

37]

.

SOX9-AS1 lncRNA is becoming more recognized for its crucial role in cancer progression and immune regulation. It is located on chromosome 17q24.3, close to the

SOX9 gene, and spans about 170 kilobases [

43]. It is mainly found in the cytoplasm of breast cancer cells [

43] and is involved in regulating transcription. It has been significantly overexpressed in several cancers, including TNBC, where it reduces therapy-induced senescence (TIS), favors cell proliferation, and influences immune evasion to exhibit oncogenic activity [

44]. Gene enrichment analysis revealed that high expression of

SOX9-AS1 in TNBC patients is significantly associated with several biological pathways, like adherens junctions, selenoamino acid metabolism, and the ErbB and Wnt signaling pathways. In cells with TNBC,

SOX9-AS1 knockdown impedes cell-cycle progression, causes apoptosis, and minimizes invasive properties, as demonstrated by a study by Xuan Ye et al. [

44].

Nevertheless, these effects are mitigated by overexpressing

SOX9-AS1, verifying its function in maintaining tumor aggressiveness. Immune infiltration analyses using CIBERSORT showed that lower levels of

SOX9-AS1 are linked to more infiltration of naïve B cells, CD8+ T cells, and γδ T cells (

Figure 1). This suggests it may suppress the immune response. This suppression seems to relate to the reduction of SASP (senescence-associated secretory phenotype) factors, including IL-6 and IL-8, which are strong chemoattractants. Functional tests confirmed that reducing

SOX9-AS1 makes TNBC cells more sensitive to tamoxifen-induced senescence. This is indicated by increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity and higher levels of SASP cytokines like IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8. Mechanistic studies showed that

SOX9-AS1 affects the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. When knocked down, it lowers β-catenin levels and alters GSK-3β activity, which promotes SASP expression and enhances senescence. Given that Wnt signaling is known to dampen antigen presentation and T cell activation,

SOX9-AS1-mediated Wnt activation may contribute to developing a non-inflamed, immunologically "cold" tumor microenvironment resistant to immune infiltration. Therefore, the SOX9-AS1/Wnt/SASP regulatory axis represents a critical mechanism by which TNBC evades both senescence and immune surveillance, as represented in the

Figure 3C. Targeting

SOX9-AS1 or its downstream effectors may sensitize TNBC to immunotherapies and senescence-inducing agents, providing a promising therapeutic strategy to convert poorly immunogenic tumors into "hot" tumors more responsive to treatment.

Another lncRNA that garners attention as a critical regulator in immune responses is

HITT (HIF-1α Inhibitor at Translation Level). It plays diverse role in tumor suppression and immune modulation. Genomically, its locus lies on chromosome 3p22.1 and with an approximate length of 32 kilobases [

45]. Although

HITT is transcribed, it does not encode a protein but exerts its functions through interactions with RNA-binding proteins and target mRNAs. It originally emerged as a transcription factor that dampens the translation of HIF-1α, vital to tumor growth and survival in hypoxic environments. Angiogenesis and glycolysis pathways, believed to be crucial to tumor development, are hampered by

HITT's inhibition of HIF-1α mRNA translation through binding. A tumor-suppressive function suggests that reduced

HITT expression is common in several types of cancers, including colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer [

45].

A recent study by Lin et al. [

46] demonstrated lncRNA

HITT's functional repertoire by exploring its role in immune regulation, specifically within breast cancer's TME. The researchers showed that IFN-γ, a key cytokine involved in immune activation, significantly upregulates

HITT expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. They found that upregulation of

HITT is IFN-γ time- and dose-dependent, indicating that

HITT responds to physiological immune stimuli. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and promoter-reporter assays, the study identifies E2F1, a transcription factor, as the mediator of this effect. E2F1 directly binds to the

HITT promoter following IFN-γ treatment. Silencing E2F1 stops

HITT induction and confirms its essential role in regulation. E2F transcription factors control genes that manage DNA replication and cell cycle progression. Uncontrolled cell growth indicates a problem in the E2F pathway in cancer, often due to mutations in the Rb tumor suppressor. Overactive E2F in combination with

HITT is a possible therapeutic target because it supports tumor growth, apoptosis resistance, and genomic instability [

47].

Functionally,

HITT overexpression reduces PD-L1 protein levels without altering PD-L1 mRNA expression, implying that

HITT suppresses translation rather than transcription of PD-L1. Conversely, knocking down or knocking out

HITT increases PD-L1 protein levels, especially when cells are stimulated with IFN-γ. This translational repression is highly significant given PD-L1's role in immune evasion, where it binds PD-1 on T cells and inhibits their cytotoxic activity, as shown in

Figure 2A. Thus,

HITT acts as a checkpoint modulator by post-transcriptionally repressing PD-L1 and potentially enhancing anti-tumor immunity. To uncover the mechanistic basis of this repression, Lin et al. investigated whether

HITT interacts with the 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR) of PD-L1 mRNA. Their experiments identified RGS2 (Regulator of G-protein Signaling 2) as a novel binding partner of

HITT. Co-immunoprecipitation and RNA pull-down assays confirmed that

HITT forms a complex with RGS2 and directly binds the PD-L1 5′-UTR. Mutational analyses of the 5′-UTR revealed that altering nucleotides 1 to 36 disrupts RGS2 binding and abolishes the repression of PD-L1 translation, underscoring the importance of this RNA motif.

HITT thus acts as a molecular scaffold, guiding RGS2 to specific RNA structures in PD-L1's 5′-UTR to block its translation initiation.

The immunological relevance of this pathway was validated using co-culture experiments with CD8+ T cells. Cancer cells overexpressing HITT were found to be more susceptible to cytotoxic T cell killing, while HITT-deficient cells were resistant. Importantly, this effect was PD-L1-dependent, neutralizing PD-L1 with antibodies that erased the difference in T cell-mediated killing, confirming the translational control of PD-L1 as the key mechanism. These in vitro results were reconfirmed by in vivo tumor mouse models. Mice with tumors that overexpressed HITT showed slower tumor growth and more T cells entering the tumor. Reintroducing PD-L1 reversed this immune-mediated tumor suppression, affirming that HITT exerts its anti-tumor effects through PD-L1 downregulation.

Lin et al. [

46] further analyzed the role of the

HITT/RGS2 axis in breast cancer tissue samples. The authors found that the

HITT/RGS2 axis may be functionally relevant in patients, as their analysis showed a negative correlation between

HITT and PD-L1 levels and a positive correlation between RGS2 expression and low PD-L1 protein. Lower PD-L1 was seen in tumors with high

HITT expression, suggesting that immune evasion may be facilitated by tumor downregulation of

HITT. This finding supports the translational significance of

HITT pathway targeting in cancer treatment. Given that PD-L1 is a central target in immune checkpoint therapy, the ability of

HITT to suppress PD-L1 at the translational level introduces a novel therapeutic approach. Unlike conventional methods that use antibodies to block PD-L1 or its receptor PD-1, modulating

HITT activity could provide a complementary or synergistic strategy. Therapeutic options may include

HITT-mimicking oligonucleotides, gene therapy to overexpress

HITT, or modulators that enhance

HITT–RGS2 complex formation. These strategies might be especially helpful in overcoming checkpoint blockade therapy resistance. Overall, the authors provide a thorough functional and mechanistic description of

HITT as a critical immune response regulator in breast cancer. The study reveals a hitherto unidentified layer of immune checkpoint regulation by clarifying how IFN-γ activates

HITT through E2F1 and how

HITT inhibits PD-L1 translation via RGS2. The study also makes a strong case for creating

HITT-based immunotherapies by confirming

HITT's immune-boosting and tumor-suppressive properties in cellular and animal models and connecting these results with clinical data. Future work could expand this paradigm to other cancers and explore combination therapies integrating

HITT activation with existing checkpoint inhibitors.

NKILA(NF-κB Interacting Long Non-Coding RNA), an 8.4-kilobase-long cytoplasmic lncRNA, plays a crucial role in cancer immunity [

48]. Initially identified for its ability to inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway in breast cancer cells,

NKILA has since been recognized as a key immunoregulatory molecule that affects T cell survival, tumor immune evasion, and the modulation of the immune microenvironment across various cancer types [

49].

NKILA directly binds to the NF-κB/IκB complex in the cytoplasm [

49]. Maintaining the stability of this complex prevents IκB from being phosphorylated and degraded. As a result, NF-κB is unable to migrate into the nucleus, suppressing the transcription of anti-apoptotic genes. NF-κB plays a key role in T-cell survival, growth, and the production of inflammatory cytokines like IL-2. Therefore,

NKILA acts as a negative regulator of NF-κB, shifting the balance toward pro-apoptotic signaling when T cells are activated. This suppression of NF-κB makes T cells, especially cytotoxic CD8⁺ T lymphocytes (CTLs) and type-1 helper T cells (TH1), very vulnerable to activation-induced cell death (AICD). In comparison, regulatory T cells and TH2 cells show relative resistance. Notably, tumor-infiltrating CTLs and TH1 cells in breast and lung cancers demonstrate elevated

NKILA expression, which correlates with increased apoptosis and poorer patient survival outcomes.

Mechanistically, the authors illustrate that upon T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement, an influx of intracellular calcium activates calmodulin, facilitating histone acetylation at the

NKILA promoter. In cancer, dysregulated calmodulin signaling contributes to tumor progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance by activating oncogenic pathways like PI3K/Akt and MAPK (Mitogen Activated protein kinase) [

50]. While histone acetylation at the NKILA promoter mechanism is beneficial in preventing chronic inflammation and autoimmunity,

NKILA becomes a disadvantage in cancer, as it induces the premature death of tumor-specific T cells. Its expression is increased by

STAT1 and histone acetylation in activated T cells, making

NKILA an essential connection between T cell activation and activation-induced cell death (AICD). This process also improves the binding of

STAT1 and the transcriptional activation of

NKILA. The expression of

NKILA leads to a continued inhibition of NF-κB, which usually supports T cell survival. As a result, higher levels of

NKILA make tumor-specific T cells more sensitive to apoptosis through Fas/FasL-induced signaling and other pathways that promote cell death during AICD. Authors further support their results by doing electrophoretic mobility shift assays using drugs to block NF-κB, which increased sensitivity to apoptosis.

The authors further demonstrate that cytotoxic T lymphocytes' (CTLs') anti-tumor efficacy and persistence increase when

NKILA is silenced. Compared to control groups,

NKILA-knockdown CTLs demonstrated enhanced tumor infiltration (

Figure 1) and decreased tumor growth in patient-derived breast cancer xenograft models. This illustrates how

NKILA modulation in adoptive T-cell immunotherapy has therapeutic potential. To sum up,

NKILA is an essential immune-regulatory long non-coding RNA. It facilitates tumor immune evasion by limiting T-cell longevity by suppressing NF-κB. Targeting

NKILA also offers a strong way to improve anti-tumor immunity and T-cell persistence in therapeutic settings.

MALAT1 (Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1), also known as NEAT2, is a highly conserved lncRNA [

51]. It is located on chromosome 11q13.1 and is about 12.8 kilobases long [

52]. This lncRNA is mainly found in nuclear speckles and is key in regulating alternative splicing, gene transcription, and epigenetic modifications [

53].

MALAT1 is often overexpressed in various cancers, including lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, and glioblastoma. It is linked to tumor progression, metastasis, and worse prognosis [

54]. It promotes cell growth, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, and immune evasion. Additionally, it acts as a sponge for tumor-suppressive miRNAs, which affects immune and inflammatory signaling pathways [

55].

To investigate the role of lncRNA Malat1 in regulating T cell infiltration in the breast tumor microenvironment, Adewunmi et al. (2023) [

56] established syngeneic mouse models using orthotopically implanted T12 and 2208L cell lines. The T12 cell line represents a claudin-low tumor subtype known for high macrophage infiltration, while 2208L is a luminal-like TNBC model with a rich presence of neutrophils. Both cell lines have highly immunosuppressive myeloid environments that support tumor growth, metastasis, and resistance to treatment. In the 2208L model, knocking down Malat1 led to more CD8+ T cells, significantly increasing cytotoxic markers Granzyme B and IFN-γ. There was also a decrease in immunosuppressive CD4+ T cells. In the T12 subtype, although the total number of CD8+ T cells stayed the same, there was a notable increase in Granzyme B+ T cell infiltration. Levels of CD4+ T cells dropped, while Treg populations were unaffected after Malat1 silencing. Overall, analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in primary tumors showed that inhibiting Malat1 using Gapmer antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) created a more immunostimulatory tumor microenvironment, boosting cytotoxic T cell infiltration and division (

Figure 1).

Tumor secretory profiles of both cell lines are also altered by Malat1 knockdown. Chemokines like Ccl5 that attract immunosuppressive M2-type macrophages are suppressed in T12 cancer cells. Also, the inflammatory cytokines that attract M1-macrophages, like Cxcl9 and Cxcl10, are decreased, denoting that macrophage repolarization to a more inflammatory state is not supported by Malat1 inhibition. Similarly, reduced secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines/chemokines, including Cxcl1, Gm-csf, TNF-α, Ccl5, and cytokine IL6, was observed in Malat1 ASO-treated 2208L cell lines. All these factors that are known to recruit MDSC (myeloid-derived suppressor cells) and develop an immunosuppressive microenvironment are reduced. By reducing the immunosuppressive activity of tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and MDSCs on T cells, Malat1 knockdown in the TNBC tumor microenvironment contributes towards a more immunostimulatory landscape, enabling a stronger T cell response towards the tumor.

In a similar exploration of MALAT1's role in T cell modulation within breast cancer, Kumar and colleagues [

57] utilized murine breast cancer models and human and mouse datasets. They found that Malat1 is essential for initiating metastatic lesions and their reactivation from dormant states. Mechanistically, among its downstream effects, Malat1 enhances the expression of WNT ligands, thereby reinforcing autocrine signaling loops that support tumor self-renewal. Additionally, it upregulates a specific set of serine protease inhibitors, most notably SERPINB6B [

57].

Functionally, SERPINB6B exhibits dual immunomodulatory effects. It inhibits caspase 1 and cathepsin G, thereby preventing the activation and pore formation of gasdermin D, which is the central executor of pyroptosis. This inhibition interrupts a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death known as pyroptosis, which typically alerts and attracts immune effectors. By impairing pyroptosis, SERPINB6B dampens immunogenic cell death signals, reducing the clearance of early metastatic lesions by cytotoxic T cells.

Genetic or pharmacologic suppression of Malat1 through antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) effectively disrupts this immune-evasive mechanism. Specifically, Malat1 ASOs downregulate SERPINB6B, lifting the blockade on caspase-1 and cathepsin G. This reinstates gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis and enhances T cell-mediated tumor lysis. The resulting molecular cascade significantly reduces metastatic colony formation and improves survival outcomes in treated mouse models. Significantly, the metastasis-suppressive effect of Malat1 inhibition is negated when SERPINB6B is knocked out, highlighting SERPINB6B as a crucial mediator of Malat1's pro-metastatic role. SERPINB6B is a serine protease inhibitor (serpin) family member that regulates protease activity and maintains cellular homeostasis. Though its specific role in cancer remains underexplored, aberrant expression of SERPINB6B has been associated with inflammation and immune modulation, suggesting potential involvement in tumor progression, immune evasion, and metastasis [

57].

Overall, this study suggests that Malat1 is a master regulator of metastatic emergence by linking tumor-intrinsic signaling with immune suppression and underscoring its potential as a target for anti-metastasis therapies.

SNHG16 (Small Nucleolar RNA Host Gene 16) lncRNA is located on chromosome 17q25.1 [

58], and has been identified as an oncogenic regulator in cervical, neuroblastoma, pancreatic, gastric, and breast cancers [

59]. It is often overexpressed and associated with adverse clinical outcomes [

60]. A pan-cancer meta-analysis indicates that upregulated expression of

SNHG16 facilitates proliferation and metastasis while blocking apoptosis by targeting key signaling pathways, such as TGF-β/SMAD, JAK/STAT3, and PI3K/AKT, as well as the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and others. Additionally,

SNHG16 acts as a sponge for several miRNAs, including miR-200a-3p, miR-132-3p, and miR-302a-3p [

61].

Recently, Ni et al. (2020) [

62] discovered that breast cancer cells create a localized immunosuppressive environment through the exosome-mediated delivery of long

SNHG16 lncRNAs. Tumor-infiltrating γδ1 T cells (Vδ1) usually have cytotoxic anti-tumor functions and are plentiful in breast tumors. However, they paradoxically do not eliminate cancer cells. Instead, a specific group of γδ1 T cells expressing CD73, an ectonucleotidase that produces adenosine, a potent immunosuppressant, is found in higher numbers in BC tissues than in normal breast tissue. Furthermore, increased levels of CD73+ γδ1 T cells are present in the peripheral blood of patients, which correlates with tumor size. Functionally, these CD73+ γδ1 T cells strongly suppress the growth of conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, reducing their ability to kill cancer cells, including the release of perforin and granzyme B. Blocking the receptor interactions of CD73 restores T-cell activity and confirms that the immunosuppressive effects of these γδ1 Tregs mainly result from excess adenosine secretion.

To investigate the upregulation of CD73 in γδ1 T cells, the authors performed transwell co-culture experiments involving breast cancer (BC) cells and primary Vδ1 T cells. They found that this effect depended on cancer cell-derived exosomes (TDEs) and the presence of TGF-β1 signaling, but did not require direct contact between the cells. It was determined that exosomes derived from BC cell lines (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, T-47D) contained significantly higher levels of SNHG16 compared to those from non-malignant breast cells (MCF-10A). Microarray analysis and qRT-PCR validation identified SNHG16 as the crucial lncRNA responsible for the induction of CD73 expression; knocking down SNHG16 in the exosomes abolished their ability to upregulate CD73 in γδ1 T cells.

Mechanistically,

SNHG16 acts as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) within γδ1 T cells by sequestering miR-16-5p. This action leads to the derepression of SMAD5, which serves as the downstream effector of the TGF-β1 pathway. The resulting elevation of SMAD5 amplifies TGF-β1 signaling, driving the transcription of CD73. Disrupting this pathway through

SNHG16 knockdown, miR-16-5p overexpression, or SMAD5 suppression prevents the induction of CD73. Consequently, the exosomal

SNHG16/miR-16-5p/SMAD5 regulatory loop prepares γδ1 T cells for CD73-mediated immunosuppression by leveraging TGF-β1 signaling,

Figure 3B. This study identifies CD73+γδ1 T cells as the primary regulatory γδ T-cell population in breast cancer, which plays a significant role in diminishing anti-tumor immunity through the production of adenosine. Notably, exosomes derived from BC cells loaded with

SNHG16 induce the phenotypic transformation of γδ1 T cells into immunosuppressive CD73+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). The authors show that TGF-β1, a recognized inducer of CD73, is further enhanced by

SNHG16 through the miR-16-5p-SMAD5 signaling pathway. Given the functional implications of γδ1 T cells transitioning from a cytotoxic to a suppressive role, this study reveals the mechanism of immune evasion in BC. It proposes that targeting exosomal communication,

SNHG16, or CD73+γδ1 Tregs could open new therapeutic possibilities. The findings highlight the broader impact of exosomal

SNHG16 long non-coding RNAs in shaping the tumor microenvironment.

Overall, from the above section, we can conclude that the aforementioned lncRNAs play a vital role in the infiltration of immune cells to the tumor microenvironment, hence controlling the breast cancer tumorigenesis.

3. Immunomodulatory lncRNAs Orchestrating T Cell Dysfunction and Immune Escape

Through the modulation of T cell activity, lncRNA contributes to establishing an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, promoting tumor immune evasion. Recruitment of immunosuppressive cells like Treg cells, M2 macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) around the tumor leads to inactivation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) by secretion of immunosuppressive chemokines like CCL2, CXCL12 [

63]. MDSCs facilitate tumor evasion through multiple mechanisms, such as depletion of arginine and increased production of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species, which impair T cell receptors (TCR). Inhibitory cytokines like transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-

ꞵ), interleukin 10 (IL-10) promote differentiation of T regulatory cells, thus inhibiting anti-tumor immunity [

64]. In addition to myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) within the tumor microenvironment (TME) show immunosuppressive properties that help tumors grow. These cells can activate immune checkpoint pathways and their related receptors, which promote tumor growth [

65,

66]. Another way tumors can trigger immunosuppressive responses is by increasing the levels of immunosuppressive molecules and their receptors. CTLA-4 (Cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated protein 4), PD1 Programmed death 1), Lymphocyte activating 3 (LAG3) are the inhibitory receptors on CD4+ T helper cells and CD8+ T cytotoxic cells that interact with specific ligands on tumor cells. These interactions suppress T cell activation, proliferation, and effector functions, resulting in immune escape of tumor cells [

67]. CTLA-4 mediates immunosuppression by inhibiting various proliferative pathways, such as the NF-kB and PI3K/Akt pathways [

68].

Another long non-coding RNA that has gained recognition as a key regulator of T-cell modulation is

SNHG1 [

21]. Originating from a host gene linked to small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs),

SNHG1 is located in the nucleus and cytoplasm, and participates in transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. It is on chromosome 11q12.3 and spans approximately 4.6Kb [

69,

70].

SNHG1 is frequently upregulated in several cancers, including breast, lung, colorectal, liver, and gliomas. Its overexpression is linked to poor clinical outcomes and tumor progression [

71]. As an oncogenic lncRNA,

SNHG1 promotes proliferation, invasion, metastasis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and resistance to apoptosis by negatively regulating tumor suppressors such as p53 [

72]. One of the main mechanisms involves acting as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) where it binds and sequesters tumor-suppressive miRNAs such as miR-448, miR-195, and miR-145, thereby facilitating oncogenic signaling pathways [

21,

70,

73]. miR-195, miR-448, and miR-14 play a significant role in breast cancer progression, prognosis, and therapy resistance. miR-195 is a tumor suppressor in breast cancer and inhibits cell growth and movement. It also spreads by targeting key oncogenes such as BCL2, CCND1, and FASN [

74]. miR-448, on the other hand, acts as a tumor suppressor by blocking genes involved in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), like ZEB1 [

75]. It also affects pathways such as PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin, which reduce metastasis and improve chemosensitivity. miR-14, although not studied as much in humans, has been linked to breast cancer progression based on similarities with Drosophila and findings from comparative studies [

76].

Recently, [

21] researchers examined

SNHG1's role in T cell responses related to breast cancer. The study found that

SNHG1 expression was higher in tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells (TILs) than in peripheral CD4+ T cells. This increase is linked to lower levels of miR-448 and higher expression of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), IL-10, and the transcription factor FoxP3. These markers suggest a rise in regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation. By directly binding to iR-448,

SNHG16 inhibits its activity, weakening its tumor suppressor ability. Since miR-448 negatively regulates IDO, IL-10, and FoxP3, its inhibition by

SNHG1 results in higher expression of IDO. IDO then breaks down tryptophan into kynurenine, creating an immunosuppressive tumor environment. This change decreases effector T cell activity while promoting Treg expansion. In in vivo murine xenograft models,

SNHG1 knockdown reduced tumor growth and lowered IL-10, IDO, and FoxP3, highlighting its role in immune evasion and tumor progression,

Figure 3A.

In summary, SNHG1 facilitates immune escape in breast cancer by enhancing Treg cell differentiation through the miR-448/IDO axis, thereby dampening anti-tumor immunity. Future studies warrant investigating whether SNHG1 modulates the infiltration and function of other immune cell subsets within the tumor microenvironment, including CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells, and M2 macrophages.

GATA3-AS1, or

GATA3 antisense RNA 1, is a long non-coding RNA in a head-to-head orientation with the

GATA3 protein-coding gene on chromosome 10p14 [

77]. It spans about 2 kb and has several splice variants, including four main exons. Under normal conditions,

GATA3-AS1 is mainly expressed in T-helper 2 (Th2) lymphocytes. It regulates

GATA3 transcription by remodeling chromatin [

78].

GATA3-AS1 brings histone methyltransferase complexes, like MLL/WDR5, to the shared promoter region of

GATA3-AS1 and

GATA3. This process helps add H3K4me3 and H3K27ac marks. It also forms DNA: RNA hybrid R-loops that support transcriptional activation [

79]. The knockdown of

GATA3-AS1 in Th2 cells decreases

GATA3 expression and the downstream cytokines IL-5 and IL-13. In the context of cancer,

GATA3-AS1 is often aberrantly overexpressed across various tumor types and functions as an oncogenic lncRNA, contributing to tumor growth and immune evasion [

23].

Zhang et al. (2020) [

23] examined how the lncRNA

GATA3-AS1 contributes to aggressive behavior in TNBC through immune evasion. Using bioinformatics tools, the authors found that

GATA3-AS1 was significantly overexpressed in both TNBC tissues and cell lines compared to normal breast tissue. This overexpression is linked to larger tumor sizes, lymph node metastasis, advanced TNM staging, and worse overall survival rates. Functional tests performed on TNBC cell lines showed that knocking down

GATA3-AS1 with shRNA led to significant reductions in proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasiveness. Additionally, there was an increase in apoptosis and greater susceptibility to CD8+ T cell-mediated killing. Mechanistically, the study reveals two distinct yet complementary molecular pathways through which

GATA3-AS1 promotes oncogenesis and immune evasion. In the first pathway,

GATA3-AS1 acts as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA), sponging miR-676-3p and thereby relieving the repression on COPS5 (also known as CSN5), a deubiquitinase that specifically stabilizes PD-L1 (

Figure 2B). Numerous assays, including RIP, luciferase reporter, and RNA pull-down, confirm the direct interaction between

GATA3-AS1 and miR-676-3p. Furthermore, knockdown experiments indicate that decreased levels of

GATA3-AS1 lead to lower COPS5 levels, enhanced ubiquitination of PD-L1, and a reduction in its half-life.

They further show that

GATA3-AS1 directly interacts with the

GATA3 protein, which helps its ubiquitination and eventual degradation. RIP assays confirm this interaction. Treatments with cycloheximide and MG132 (a proteasome inhibitor) reveal that overexpression of

GATA3-AS1 speeds up the turnover of

GATA3. Since GATA3 is a transcription factor that encourages luminal differentiation and reduces malignancy, its destabilization worsens the malignant phenotype. By stabilizing PD-L1,

GATA3-AS1 supports immune escape in TNBC.

GATA3-AS1 knockdown leads to increased PD-L1 ubiquitination, decreased protein levels, stronger CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration (

Figure 1), and heightened apoptosis, demonstrating restored anti-tumor immunity. This dual mechanism PD-L1 stabilization via miR-676-3p/COPS5 and GATA3 destabilization positions

GATA3-AS1 as a central driver of aggressive growth and evasion of host immunity in TNBC. The authors note that these findings highlight

GATA3-AS1 as a promising therapeutic target: targeting it could destabilize PD-L1, restore

GATA3 tumor-suppressive functions, suppress tumor proliferation, and enhance immunotherapy responses.

This study advances our understanding of lncRNA-mediated cancer progression by shedding light on how lncRNA orchestrates both the tumor microenvironment and malignant behavior. It identifies GATA3-AS1 as a powerful oncogenic driver and immune modulator in TNBC. Further studies are warranted to understand more about the role of GATA3-AS1 in immune evasion.

Tissue differentiation-inducing non-protein coding RNA

(TINCR) was first characterized over a decade ago for its role in regulating cellular differentiation and tumor progression. It is situated on chromosome 19p13.3 [

8]. The

TINCR gene spans approximately 20 kilobases and is transcribed into a long non-coding RNA that lacks significant open reading frames. Functionally,

TINCR is highly versatile; it serves as a molecular scaffold for proteins, recruits epigenetic modifiers, and acts as a competing endogenous RNA.

Wang et al. (2023) [

22] looked at how lncRNA

TINCR weakens the effectiveness of PD-L1 inhibitors in breast cancer. It does this by creating a complex network that involves changes to genes and immune responses. The authors note that PD-L1 blockage often has limited success in breast cancer because tumors can escape the immune system. They focus on

TINCR, which is linked to cancer progression, as a possible reason for this immune resistance. Their findings show that

TINCR is overexpressed in both breast cancer tissues and cell lines. This overexpression is positively linked to PD-L1 protein levels, suggesting a direct role in avoiding immune attacks. Through functional tests, they show that

TINCR encourages breast cancer cell growth, movement, invasion, and tumor development in living organisms. Importantly, silencing

TINCR improved the effectiveness of PD-L1 blockage in mouse models. This suggests that

TINCR significantly contributes to resistance against immunotherapy.

The study reveals that TINCR regulates PD-L1 primarily at the protein level by inhibiting its ubiquitin-mediated degradation rather than affecting PD-L1 transcript levels. This led the authors to identify the deubiquitinase USP20 as a downstream effector whose expression is promoted by TINCR. The knockdown of USP20 replicates the decline in PD-L1 protein levels, while USP20 overexpression restores these levels in TINCR-deficient cells, thereby confirming a functional relationship. Mechanistically, TINCR acts as a ceRNA in the cytoplasm by sponging miR-199a-5p. This microRNA would otherwise bind to and degrade USP20 mRNA. As a result, the stability of USP20 mRNA improves, which leads to higher levels of USP20 protein and a subsequent decrease in PD-L1 ubiquitination.

TINCR is involved in nuclear epigenetic regulation by recruiting the DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 to the promoter of miR-199a-5p. This recruitment leads to CpG methylation, which causes the transcriptional downregulation of the miRNA and an increase in USP20 expression. These cytoplasmic and nuclear mechanisms significantly raise levels of USP20 and PD-L1 proteins. Further investigation shows that IFN-γ signaling acts as an upstream regulator of TINCR through the phosphorylation and activation of STAT1. After IFN-γ stimulation, STAT1 binds to the TINCR promoter, which boosts TINCR transcription. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and luciferase assays confirm the direct interaction between STAT1 and the TINCR promoter. Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis of tissue specimens also shows a link between STAT1 and TINCR expression.

This study is the first to identify

TINCR as a crucial regulator of tumor immunity in breast cancer, broadening its previously established roles beyond tumor progression. The IFN-γ/

STAT1→

TINCR→USP20→PD-L1 pathway connects inflammatory signaling with immune evasion (

Figure 2C), revealing a network in which

TINCR fine-tunes the stability of USP20 both epigenetically and post-transcriptionally to increase PD-L1 protein levels. This ultimately dampens T cell-mediated anti-tumor activity and diminishes the efficacy of PD-L1 inhibitors. Experimental results demonstrate that

TINCR knockdown significantly enhances tumor sensitivity to PD-L1 blockade in mouse models, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target. It is clear that

TINCR lncRNA functions are significantly exacerbated because it works in two ways: it recruits DNMT1 in the nucleus and acts as a miRNA sponge in the cytoplasm. This suggests that focusing on

TINCR could improve the immune system against breast cancer by lowering PD-L1 levels and making it easier for the immune system to reactivate.

Overall, this study discovers an innovative method by which breast cancers can resist immunotherapy and implies that TINCR might serve as a good target for making PD-L1-based treatments operate more effectively.

5. Conclusion and Future Outlook

In conclusion, current evidence emphasizes the essential role of lncRNAs as central regulators of the tumor immune landscape, specifically by influencing the T cell dynamics. This review highlights various lncRNAs, such as LINC00472, MIAT, HITT, NKILA, MALAT1, and SNHG16, affecting T cell infiltration. The role of SNHG1, TINCR, and GATA3-AS1 in immune escape is also discussed, providing insights into how lncRNAs facilitate breast cancer immunity, which can be utilised for therapeutic purposes.

By reviewing available literature, we have observed that lncRNA mediates T cell activation, differentiation, exhaustion, and immune checkpoint expression within the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer. By modulating the differentiation and functional aspects of Treg and T cytotoxic cells, lncRNA can inhibit tumor growth or aid in tumor immune evasion by recruiting Treg cells, M2 macrophages, and MDSCs. LncRNA uses key signaling pathways like NF-kB, Wnt/ β-catenin, PI3/AKT, and JAK/ STAT to modulate T-cell plasticity. Interfering with the lncRNA-regulated signaling may improve immunotherapeutic efficacy, better stratification of breast cancer patients, and personalised therapeutic paradigms. LncRNAs exhibit their immunomodulatory effects by various molecular mechanisms, like miRNA decoy activity, transcriptional regulation, and direct interaction with protein complexes involved in immune signaling.

The cytokine and chemokine signaling, which governs T cell activation (e.g., IL-2), T cell differentiation (e.g., IL-12, IL-4), T cell migration (eg, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10), and effector functions (IFN-ɣ, TNF-ɑ), has a crucial role in T cell-mediated immune functions. LncRNAs, including SOX9-AS1, NKILA, MALAT1, HITT, and GATA3-AS1, regulate key signaling cascades, driving the changes in cytokine and chemokine production, thus remodelling the tumor microenvironment. By altering the IFN-ɣ signaling, HITT fosters an immunologically active tumor microenvironment. NKILA plays an immunosuppressive role by sensitising T cells to activation cell death. lncRNAs like LINK-A, MALAT1, MIAT, and GATA3 possess strong potential as prognostic and diagnostic breast cancer biomarkers, as their expression profiles are often associated with TNM staging, survival rates, and T cell infiltration rates. Upregulated MIAT, SOX9-AS1, and HITT profiles exhibit delayed tumor growth by increased CD8+ cytotoxic T cells infiltration into tumor sites. Similarly, down regulation of MALAT1, GATA3-AS1 and NKILA promotes CD8+ T cell infiltration, suppressing tumor proliferation and facilitating the immunotherapy response. As a molecular sponge for distinct miRNAs, lncRNAs such as MIAT1 and GATA3-AS1 regulate PDL1 expression through a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) mechanism. Overexpression of lncRNA, such as TINCR and MIAT, GATA3-AS1, and knockdown of HITT is associated with increased PD-L1 protein activity, either by enhanced PD-L1 deubiquitination or by increasing PD-L1 translation, thus aiding in tumor immune evasion.

Based on the current study's findings, to fully understand the roles lncRNAs play in T cell activation and exhaustion completely, more research focusing on the functional validation of lncRNAs using in vivo and single-cell multi-omics technologies is warranted. Clinical evaluation of lncRNA expression profiles is required to establish them as reliable biomarkers for prognosis and patient stratification. Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools can also be utilized to correlate the expression patterns of lncRNAs with T cell function and activation, to potentially improve immunity in breast cancer patients. For therapeutic purposes, lncRNAs that are oncogenic could be targeted, or lncRNAs that are tumor-suppressive could be restored, utilizing promising technologies, like CRISPR, CAR-T cells, and antisense oligonucleotides. Moreover, lncRNA modulation along with immune checkpoint inhibitors may be used to improve personalized immunotherapy for breast cancer. Based on the characteristics of the tumor microenvironment and the levels of immune cells, personalized immunotherapy options, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors or combination therapies, can be provided to improve breast cancer care.