Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

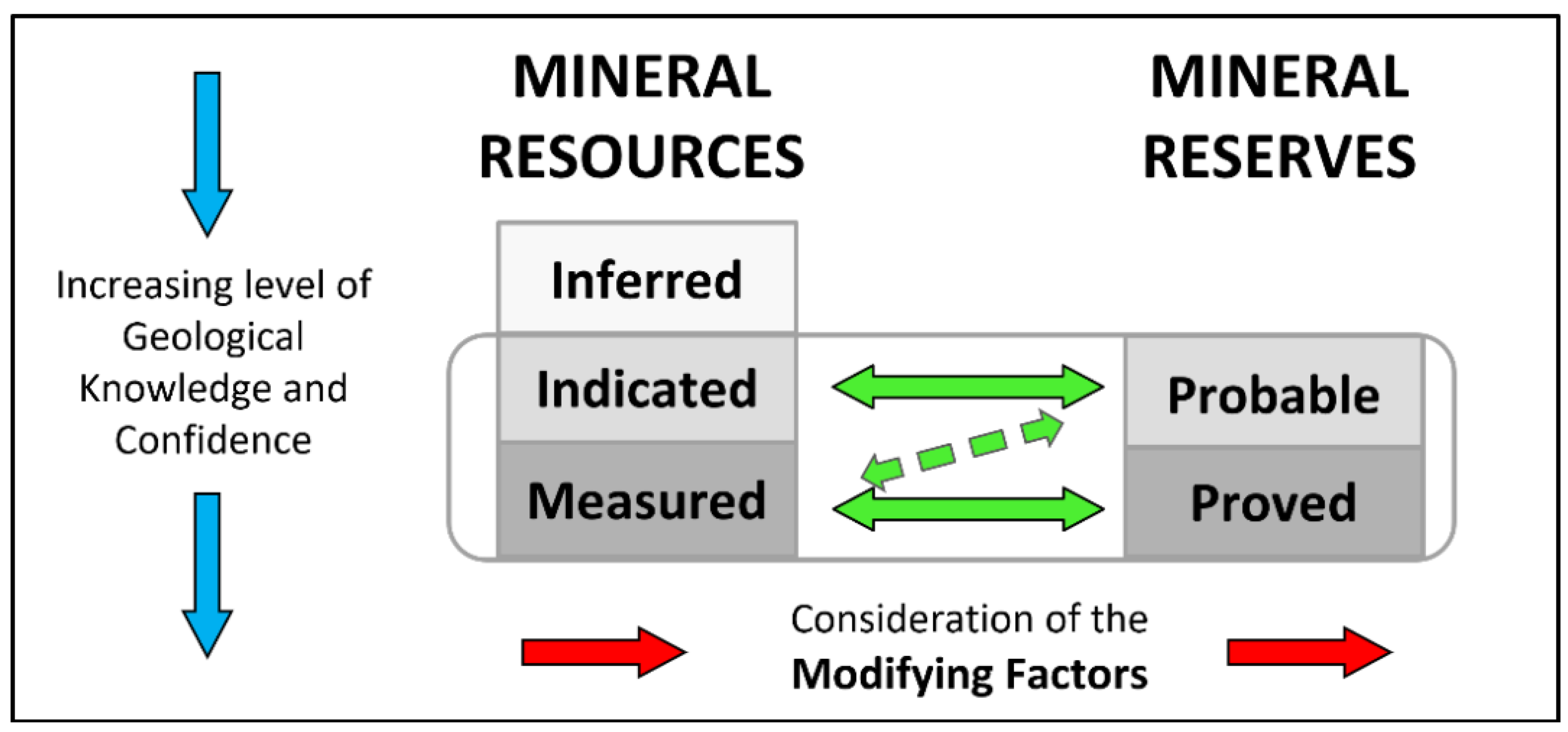

1. Introduction

- Measured resources or proved reserves: ± 5-10% for annual production periods or ± 10-15% for three monthly production periods.

- Indicated resources or probable reserves: ± 10-15% for annual production periods or ± 15-25% for three monthly production periods.

2. Materials and Methods

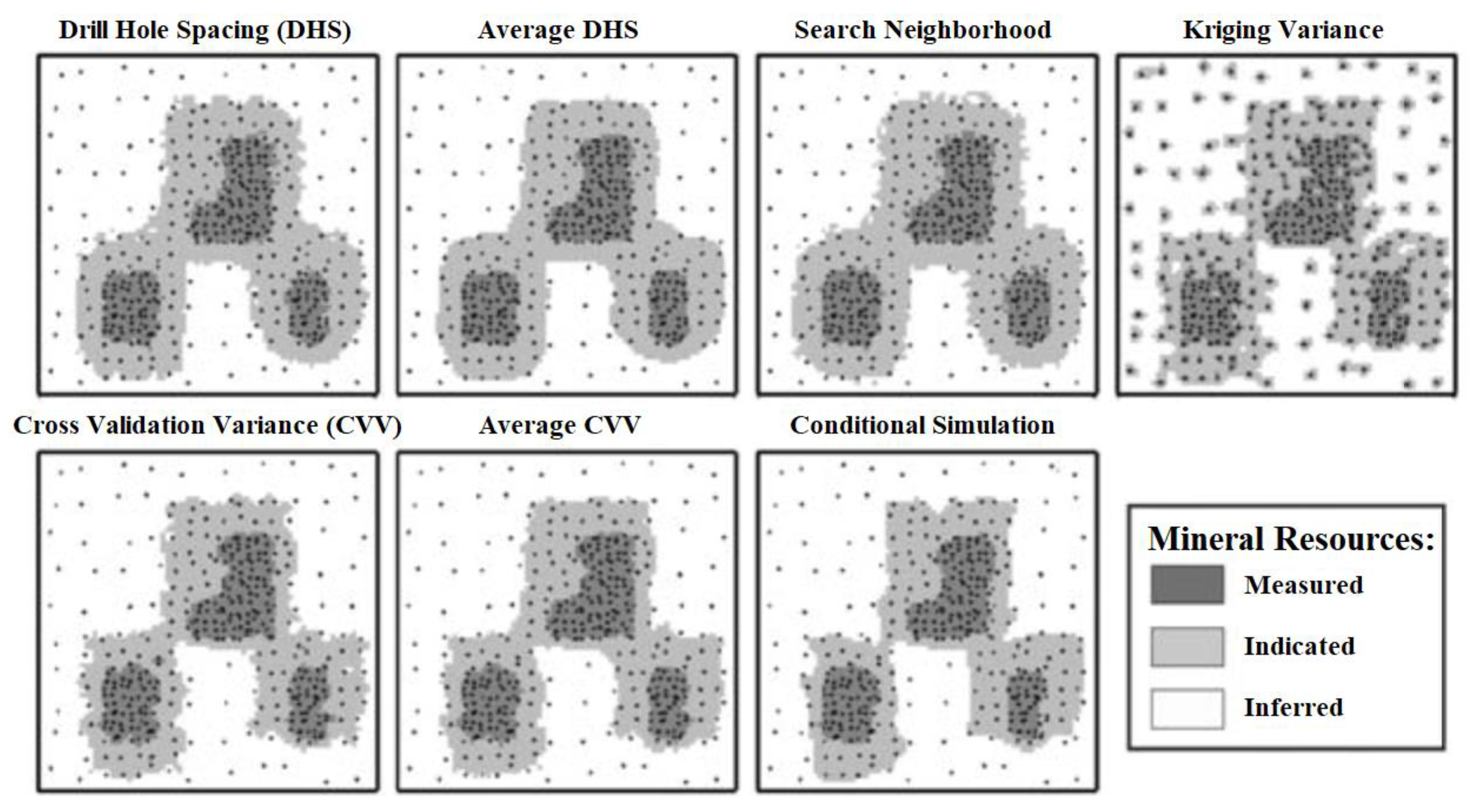

2.1. MR³ Index Classes

2.2. Sub-Classes Score Assignment

- Binary sub-classes are assessed with a simple yes/no criterion. Full compliance scores 100%, while non-compliance results in a score of 0%. Example: the presence of a competent person (CP) or qualified person (QP) for resource classification.

- Scaled sub-classes use a 0-to-5 scale, reflecting progressive levels of compliance. A score of 5 corresponds to full compliance (100%), while intermediate values represent partial compliance. Example: status of environmental licensing, where some licenses may be obtained while others are pending.

2.3. Sub-Classes Description

2.3.1. Competence Class Aspects

2.3.2. Transparency Class Aspects

2.3.3. Materiality Class Aspects

2.3.4. Modifying Factors Class Aspects

2.4. Calculating the Final Score

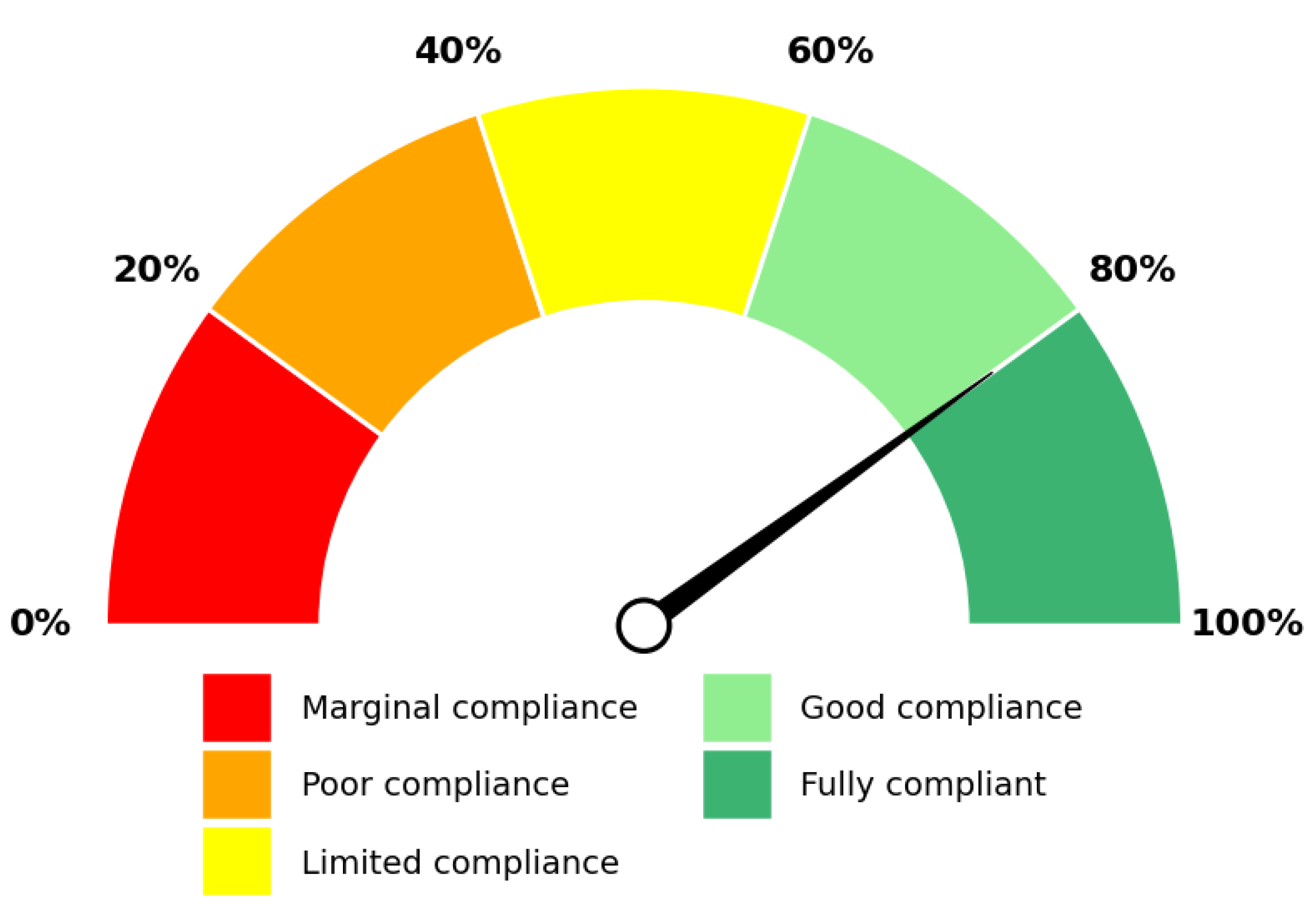

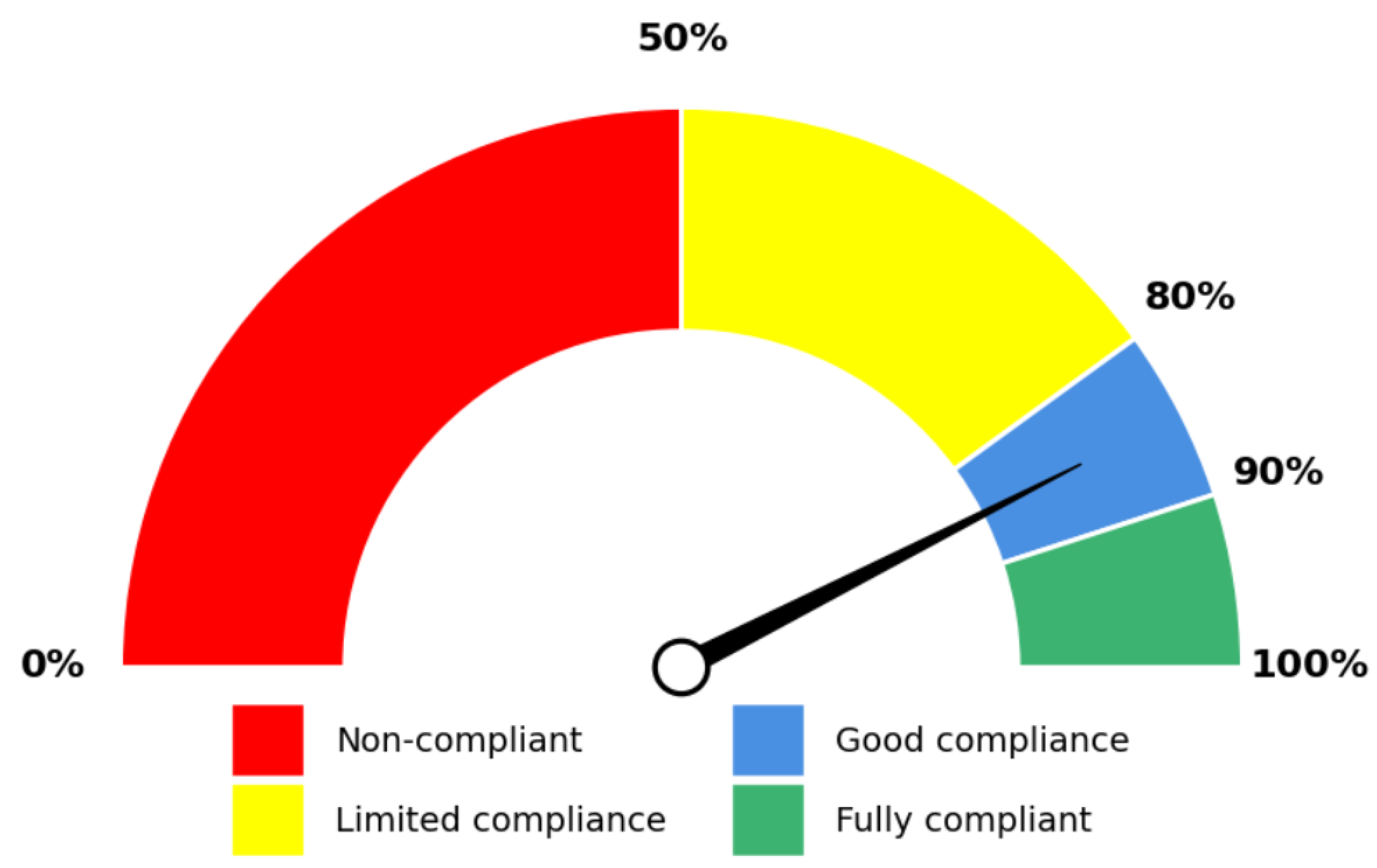

2.5. MR³ Index Classification

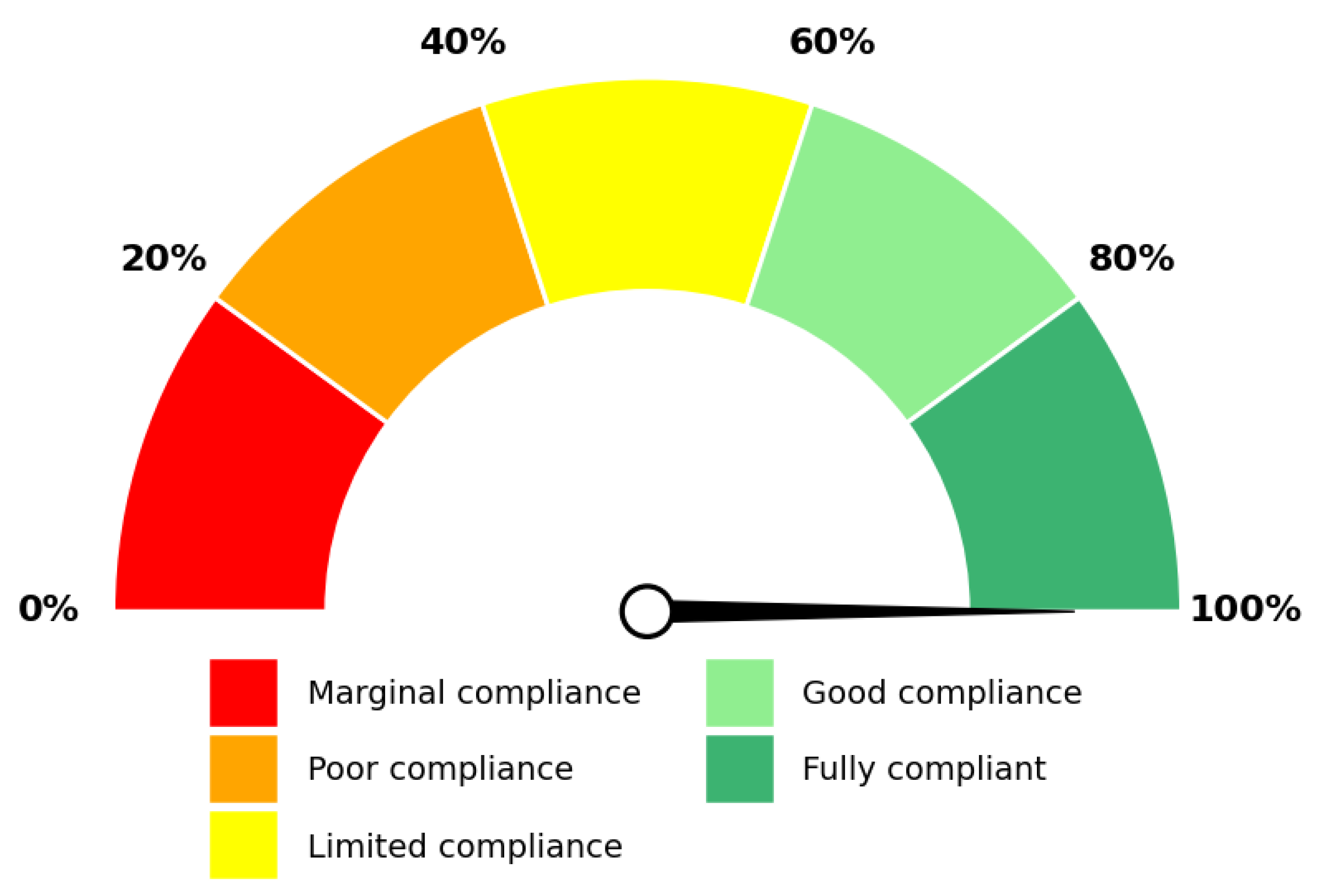

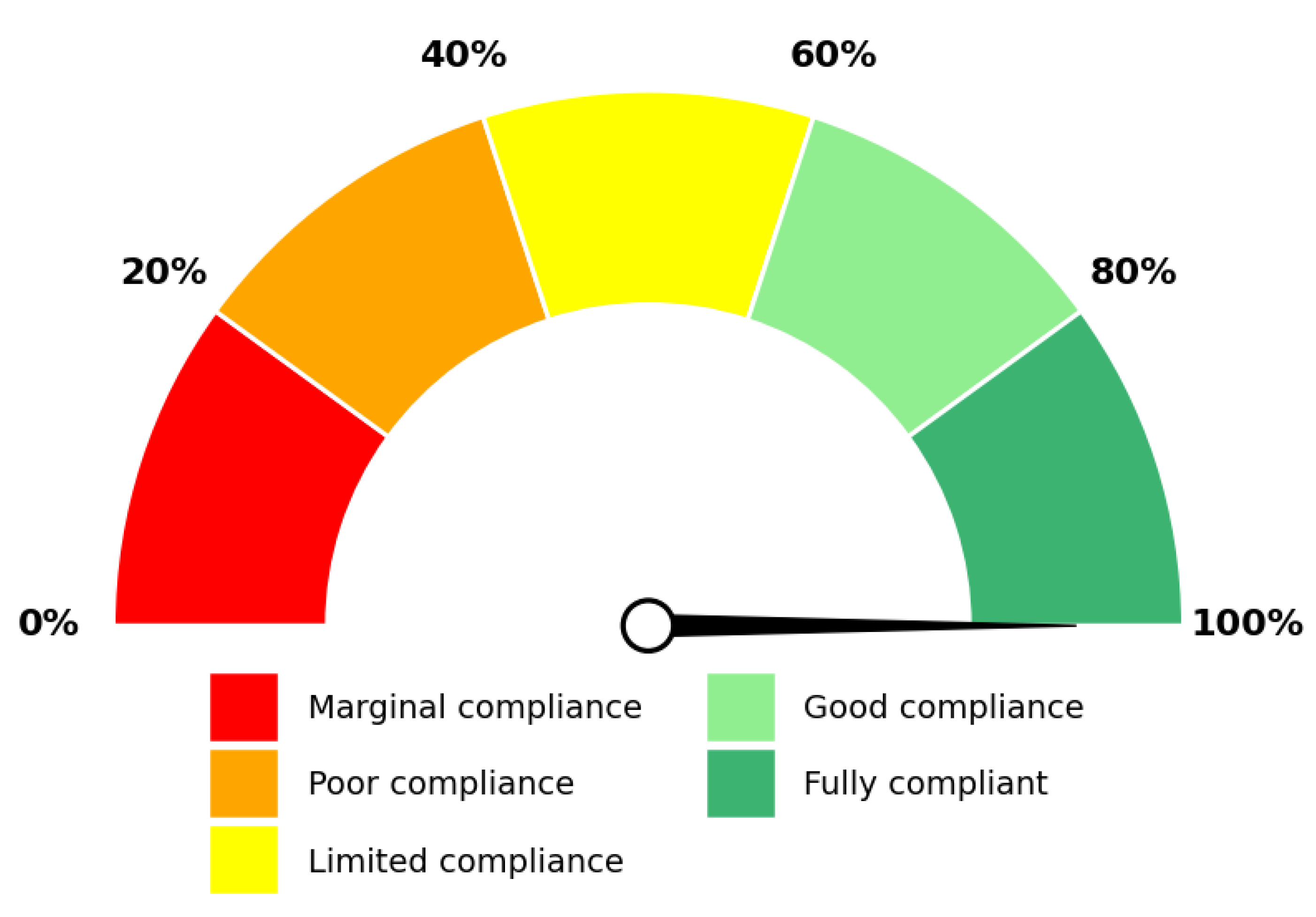

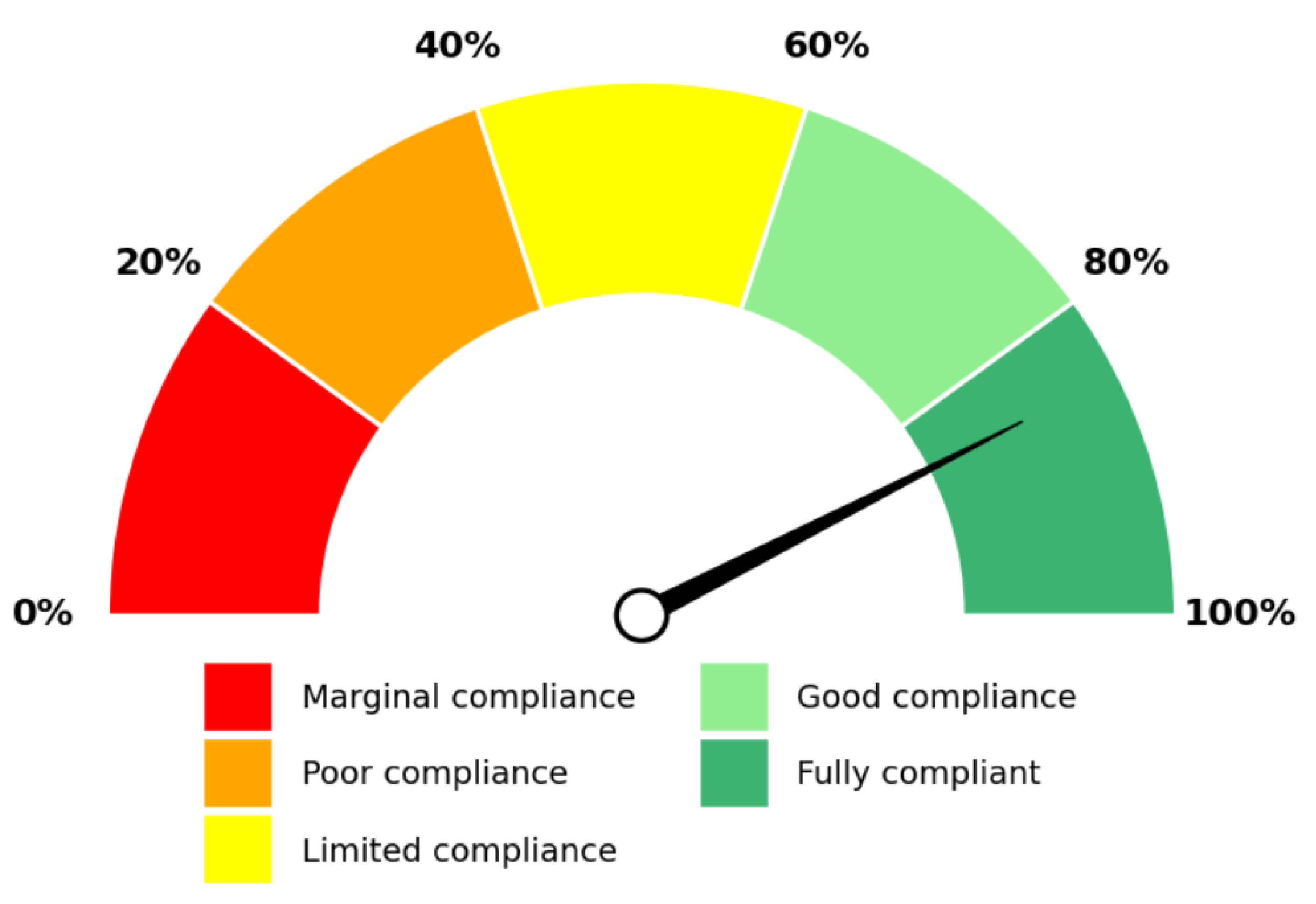

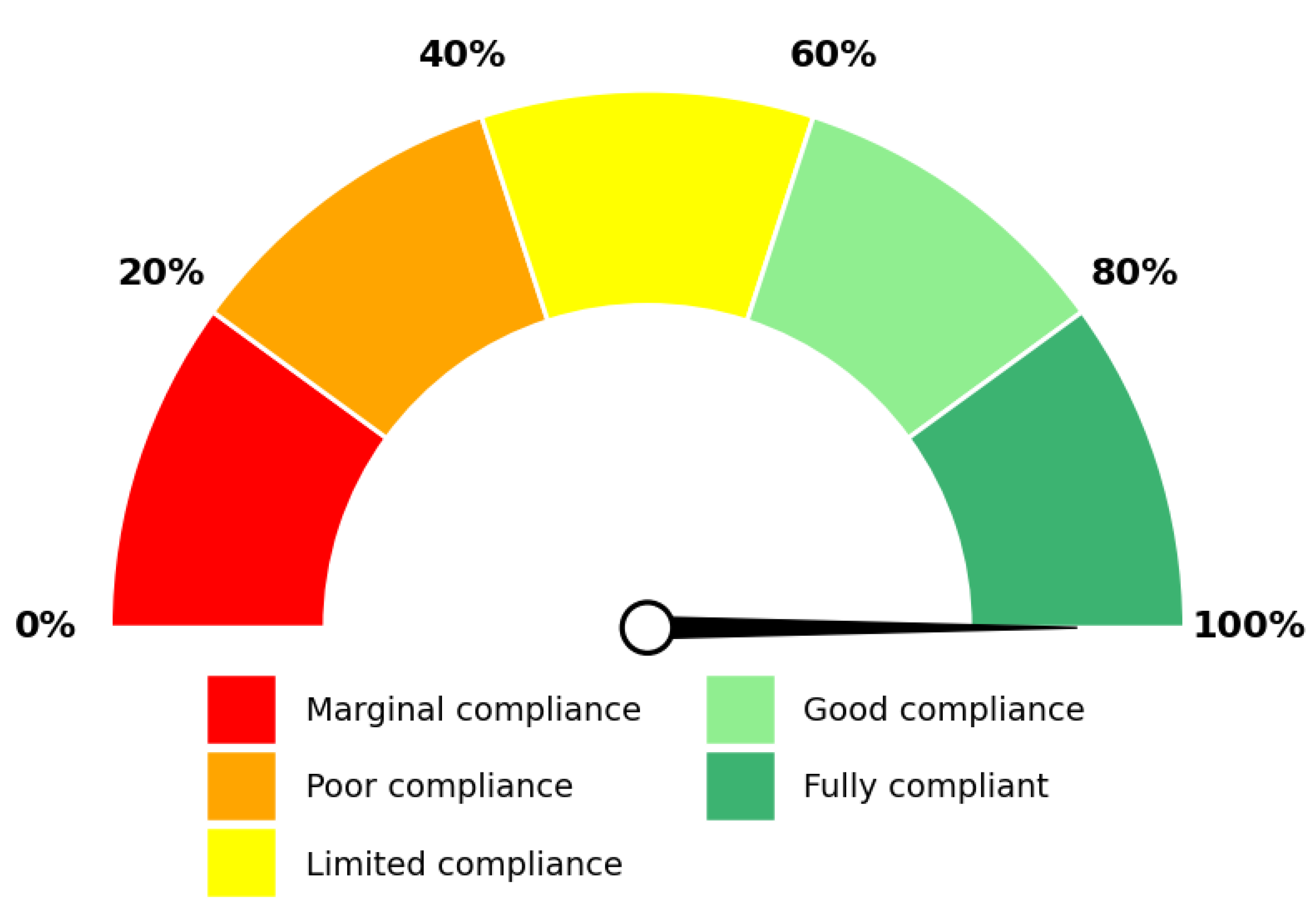

- : Non-compliant;

- : Limited compliance;

- : Good compliance;

- : Fully compliant.

2.6. General Comments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mine Operation Under Study

3.2. MR³ Index Classes Calculation

3.2.1. Competence Class Assignment

- Mineral Resources CP/QP: Letter of Consent and report from the mineral resources’ consultants, submitted to the company’s board in February 2025.

- Mineral Reserves CP/QP: Technical Report (internal draft) of the company’s expansion project, namely, Project 100k, submitted to the company’s board in August 2025.

3.2.2. Transparency Class Assignment

- Exploration Results Disclosure: Official exploration results’ report, submitted to and approved by the National Mining Agency in June 2006 (for the exploration permit areas). The report describes geological mapping, geophysical, and geochemical campaigns; channel and rock chip sampling were performed, as well as mineralogical analysis and mineral characterization; exploratory drillhole campaigns and laboratory analysis results respecting QA/QC principles supported the report conclusions. The current exploration work, which includes geophysical campaign in conjunction with the Brazilian Geological Survey (carried out during the first half of 2025), geochemistry, trenches, and extensive drilling campaign will be the object of an updated report to be submitted to the Brazilian National Agency in the first quarter of 2026. Since updating this data with the National Mining Agency is not mandatory after the mining permit is granted, and since the reports and documents from the most recent campaigns are robust and auditable by any external auditor, this sub-class can be considered fully compliant.

- Mineral Resource Modelling Disclosure: Official report of updated reserves, submitted to and approved by the National Mining Agency in August 2022 (for the mining concession area). The report provides drillcore geological and geotechnical description, in addition to laboratory results from the drillhole campaigns; the geological model was based on the cross-sectional method; an estimation model based on ordinary kriging was supplied, along with a mineral resource classification based on the polygonal method; the models rely on laboratory analysis results respecting QA/QC principles, and a simplified economic assessment was provided.

- Mineral Reserve Modelling Disclosure: Technical report of the economic exploitation report, submitted to and approved by the National Mining Agency in May 2023 for the mining concession area). The report provides a complete economic evaluation of the operation, including: mining equipment and processing plant dimensioning; a life of mine plan (LoMP) for 14 years based on the mining sequence through the sublevel stopping operation; an economic evaluation encompassing aspects such as the lithium selling price and revenue forecast, capital and operational expenditure, taxation, and economic results (e.g. internal rate of return and net present value).

3.2.3. Materiality Class Assignment

- Disclosure of Key Risks and Constraints: The LOM 2025 report, submitted to the company’s board in August 2025, presents the results and analysis of the operational, technical, and economic aspects of Project 100k. Among the key risks, the report highlights potential constraints related to infrastructure capacity, market fluctuations, and permitting timelines, proposing measures to mitigate these risks through contingency planning and staged investments. The disclosure is adequate and aligned with international reporting expectations. Nevertheless, the report does not provide a quantified ranking of risks by probability and impact, and the mitigation measures are outlined superficially. While compliant, the disclosure could be enhanced by adding more detail on prioritization and implementation.

- Disclosure of Economic Assumptions: The company’s LOM 2025 report sets out the economic assumptions in the Project 100k, including revenue sources, unit costs, and a detailed breakdown of capital and operating expenditures. An updated cost table provides details on the project’s financial requirements. Standard sensitivity analyses were included, but some of the assumptions rely on a simplified market forecast. In addition, although some sensitivity tests are presented, no full scenario analysis is provided. While compliant, these points suggest areas where the economic disclosure could be strengthened.

- Consistency in Technical Narrative: The company’s LOM 2025 report demonstrates consistency across its main sections, with the geological model, mine planning, and financial projections integrated and aligned with the modifying factors considered. Cross-references between sections are well established, avoiding contradictions in tonnage, grade distribution, or scheduling. This ensures that the technical narrative remains coherent throughout the document, supporting decision-making reliability. However, the report could be further reinforced by adding more detail on how the updated geological model relates to past performance, and by expanding on the integration of geotechnical, metallurgical, and economic factors into the production schedule. Even so, these are minor points that do not affect compliance significantly.

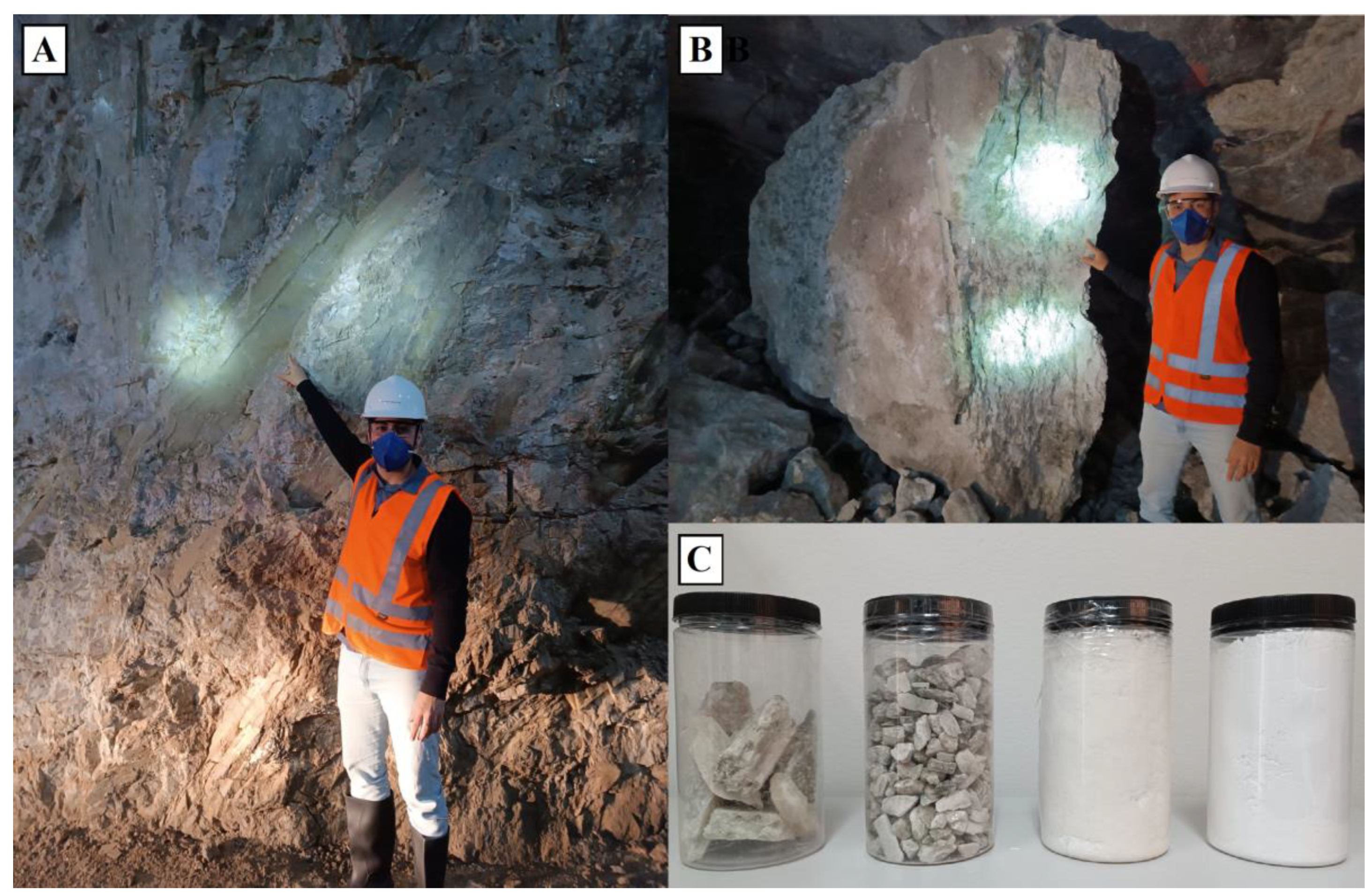

- Consistency in Drillhole Reconciliation: The audit report prepared by an independent CP/QP (May 2025) assessed a set of random drillholes, validating geological and geotechnical descriptions against physical drillcores. The analysis confirmed robustness between digital datasets and real information, strengthening confidence in the database and supporting compliance with reporting standards. Figure 9 illustrates the physical drillcores presented during the site visit. While fully compliant, the disclosure could be slightly enhanced by providing more detail on the drillhole selection process.

3.2.4. Modifying Factors Class Assignment

- Mining, Processing, and Metallurgical Factors: The LOM 2025 report, submitted to the board in August 2025, presents detailed descriptions of the mining method and development activities, as well as the processing and metallurgical routes. An additional report by external consultants (July 2025) provided further details on the planned expansion of the processing plant under Project 100k. Together, these documents confirm the feasibility of sustaining the desired production rate, ensuring sufficient mining fronts, adequate haul roads for increased traffic, and a processing route capable of delivering lithium concentrate at the required grade and quantity. Geometallurgical aspects are also addressed, reinforcing confidence in the integration between mine planning and processing capacity.

- Inferred Resources Confidence for Production: To support confidence in the quality of inferred resources, the company submitted a technical report prepared by the SGS Lab and presented to the board in September 2025. In this study, nine representative drillcore samples were collected from the inferred, indicated, and measured resource categories and submitted to laboratory analysis, including heavy-liquid separation tests. The results confirmed that lithium grades in ore samples across all categories were similar, as well as grades and recoveries in concentrate samples, which reinforces a geometallurgical homogeneity between the inferred resources and the ore currently mined and processed at CBL. These findings support the robustness of the geological model and provide assurance that inferred resources can be progressively upgraded to indicated and measured resources as drilling campaigns advance.

- Economic, Market, and Infrastructure Factors: Annual Mining Reports submitted to the Brazilian National Mining Agency for 2022, 2023, and 2024 confirm the mine’s consistent economic performance, established infrastructure, and reliable market conditions. The operating history of Cachoeira Mine shows that logistics and facilities are fully consolidated, while a stable customer base provides additional security. In particular, integration with CBL’s chemical plant ensures a significant share of concentrate has a guaranteed downstream market for conversion into high-purity lithium compounds.

- Regulatory and Legal Factors (Compliance Legal): The company provided certifications from National and State Government Agencies confirming compliance with mining and environmental requirements, as shown in Table 9. Contracts with surface landowners were also disclosed, demonstrating regulatory alignment and legal security for current and planned operations.

- Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG): The company presented valid certifications covering management, environmental performance, safety, and social responsibility, as shown in Table 10. These documents highlight the company’s commitment to ESG standards and to maintaining safe and socially responsible operations.

- Tailings Monitoring: The Monitoring and Control Program for Waste and Tailings Stockpiles, approved by the National Mining Agency in 2024, was provided. This report includes measures to ensure the stability, safety, and long-term sustainability of tailings storage facilities, addressing monitoring routines, risk management protocols, and mitigation actions.

| Certification standard | Date of Issue | Certifying body |

|---|---|---|

| ABNT NBR ISO 9001 – Quality Management System – Requirements | Nov/25 | Bureau Veritas |

| ABNT NBR ISO 14001 – Environmental Management System – Requirements with guidance for use | Nov/25 | Bureau Veritas |

| ABNT NBR ISO 45001 – Occupational Health and Safety Management System – Requirements with guidance for use | Nov/25 | Bureau Veritas |

| ABNT NBR 16001 – Social Responsibility – Management System – Requirements | Jan/25 | Bureau Veritas |

| BV ESG 630 - ESG Requirements | Feb/25 | Bureau Veritas |

| Sub-class | Score | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mining, Processing and Metallurgical Factors |  |

The company was able to provide detailed mining, processing, and metallurgical studies to support confidence in the operation | Not required |

|

Inferred Resources Confidence for Production |

|

Laboratory analysis demonstrated a high level of homogeneity among different resources categories, since inferred resource samples behave similarly to indicates and measured resources across heavy liquid separation tests | Not required |

| Economic, Market, and Infrastructure Factors |  |

The Annual Mining Reports for the last three years were presented, justifying that the current economic assumptions, market, and infrastructure are solid | Not required |

| Regulatory and Legal Factors |  |

Current State and Federal license certificates were provided | Not required |

| Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) |  |

Certification standards regarding management, environment, safety, and social responsibility were provided | Not required |

| Tailings Monitoring |  |

The company was able to provide an approved report on Monitoring and Control Program for Waste and Tailings Stockpiles | Not required |

3.3. MR³ Index Classification

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASE | Alberta Stock Exchange |

| AusIMM | Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy |

| CBL | Companhia Brasileira de Lítio |

| CIM | Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum |

| CMMI | Council of Mining and Metallurgical Institutions |

| CP | Competent person |

| CRIRSCO | Committee for Mineral Reserves International Reporting Standards |

| CVV | Cross validation variance |

| DHS | Drill hole spacing |

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| IMM | Institution of Mining and Metallurgy |

| IOM3 | Institution of Materials, Minerals & Mining |

| IPO | Initial public offering |

| IRMA | Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance |

| JORC | Joint Ore Reserves Committee |

| LoMP | Life of mine plan |

| MR³ | Mineral Resource and Reserve Readiness Index |

| PO | Professional organization |

| QP | Qualified person |

| SAIMM | Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SME | Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration |

| TSX | Toronto Stock Exchange |

References

- CRIRSCO. International Reporting Template for Public Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves. Available online: https://crirsco.com/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2024/06/CRIRSCO_International_Reporting_Template_June2024_Update_Approved_for_Release_20240627-dl8515.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Miskelly, N. Progress on international standards for reporting of mineral resources and reserves. Available online: https://yermam.org.tr/uploads/kutuphane/627742_progress_nmrestonpaper.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Cuchierato, G.; Chieregati, A.C.; Castilho, Y.F.P.; Prado, G.C. A practical review of the evolution of international reporting standards for mineral resources and mineral reserves. REM Int. Eng. J. 2025, 78(1), e240037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AusIMM. Australasian Code for Reporting Identified Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves. Available online: https://www.jorc.org/docs/historical_documents/1989_jorc_code.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- IMM. Definitions of Resources and Reserves. Ruling and recommendations of the Council; Institution of Mining and Metallurgy: London, United Kingdom, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- SME. A Guide for Reporting Exploration Information, Resources and Reserves; Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration Inc.: Englewood, United States, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- AusIMM; AIG; MCA. Australasian Code for Reporting of Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves (The JORC Code). Available online: https://www.jorc.org/docs/historical_documents/1999_jorc_code.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- SAIMM. South African Code for Reporting of Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves (The SAMREC Code). Available online: https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/media/gxwfraxr/south-africa-code.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- CSA. National Instrument 43-101 – Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects. Available online: https://www.asc.ca/-/media/ASC-Documents-part-1/Regulatory-Instruments/2018/10/4410886-v1-NI-43-101-INITIAL-IMPLEMENTATION-FEB1-2001-PDF.PDF (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- CIM. CIM Definition Standards for Mineral Resources & Mineral Reserves. Available online: https://mrmr.cim.org/media/1128/cim-definition-standards_2014.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- SEC. Modernization of property disclosures for mining registrants. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/files/rules/final/2018/33-10570.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- PERC. PERC Reporting Standard 2021. Available online: https://percstandard.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/PERC_REPORTING_STANDARD_2021_RELEASE_01Oct21_full.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- CBRR. The CBRR Guide for Reporting Exploration Results, Mineral Resources, and Mineral Reserves. Available online: https://mrmr.cim.org/media/1054/519-cbrr_2016.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- AIG; AusIMM; AMC. The JORC Code 2012 Edition. Available online: https://www.jorc.org/docs/JORC_code_2012.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- CSA. National Instrument 43-101 – Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects. Available online: https://www.bcsc.bc.ca/-/media/PWS/New-Resources/Securities-Law/Instruments-and-Policies/Policy-4/43101-NI-July-25-2023.pdf?dt=20230720163240 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Annels, A.E. Mineral Deposit Evaluation: A Practical Approach, 1st ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, England, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, J. K. Quantification of uncertainty in ore-reserve estimation: Applications to Chapada Copper Deposit, state of Goiás, Brazil. Nat. Resour. Res. 1999, 8(2), 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.E.; Deutsch, C.V. Mineral Resource Estimation; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, Netherlands. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.S.F.; Boisvert, J.B. Mineral resource classification: a comparison of new and existing techniques. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2014, 114(3), 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Abzalov, M. Applied Mining Geology. Modern Approaches in Solid Earth Sciences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noppé, M.A. Communicating confidence in mineral resources and mineral reserves. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2014, 114(3), 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulos, R. Stochastic optimization for strategic mine planning: A decade of developments. J. Min. Sci. 2011, 47, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariz, J.L.V.; Rocha, S.S.; Souza, J.C.; Maior, G.R.S. Stochastic economic feasibility assessment and risk analysis of a quarry mine focusing on the Brazilian tax system. REM Int. Eng. J. 2023, 76(1), 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, B.; Madani, N.; Carranza, E.J.M. Combination of geostatistical simulation and fractal modeling for mineral resource classification. J. Geochem. Explor. 2015, 149, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A; Hassani, H. ; Moarefvand, P.; Golmohammadi, A.; Jabbari, N. Three-dimensional subsurface modeling and classification of mineral reserve: A case study of the C-north iron skarn ore reserve, Sangan, NE Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Deng, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Wan, L.; Zhang, R. Fractal models for ore reserve estimation. Ore Geol. Rev. 2010, 37(1), 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, S.K.A.; Dagdelen, K. Critical review of mineral resource classification techniques in the gold mining industry. In Mining goes Digital, 1st ed.; Mueller, C., Assibey-Bonsu, W., Baafi, E., Dauber, C., Doran, C., Jaszczuk, M., Nagovitsyn, O., Eds.; CRC Press: London, England, 2019; pp. 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, X; Ortiz, J. M.; Rodríguez, J.J. Quantifying uncertainty in mineral resources by use of classification schemes and conditional simulations. Math. Geol. 2006, 38, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daya, A. Ordinary kriging for the estimation of vein type copper deposit: A case study of the Chelkureh, Iran. J. Min. Metall. 2015, 51A, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edixhoven, J.D.; Gupta, J.; Savenije, H.H.G. Recent revisions of phosphate rock reserves and resources: reassuring or misleading? An in-depth literature review of global estimates of phosphate rock reserves and resources. Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss. 2013, 4, 1005–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edixhoven, J.D.; Gupta, J.; Savenije, H.H.G. Recent revisions of phosphate rock reserves and resources: a critique. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2014, 5, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Zhang, S. Analysis of the rare earth mineral resources reserve system and model construction based on regional development. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 900219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghvaeenezhad,M; Shayestehfar, M.; Moarefvand, P.; Rezaei, A. Quantifying the criteria for classification of mineral resources and reserves through the estimation of block model uncertainty using geostatistical methods: a case study of Khoshoumi Uranium deposit in Yazd, Iran. Geosystem Eng. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Taghvaeenezhad,M.; Shayestehfar, M.; Moarefvand, P. Applying analytical and quantitative criteria to estimate block model uncertainty and mineral reserve classification: A case study: Khoshumi Uranium deposit in Yazd. J. Min. Environ. 2021, 12, 425–441. [CrossRef]

- Jiankeng, Z.; Qianhong, W.; Jiqiu, D. The realization and application of mineral resources and reserves estimation based on MapGIS. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 88-89, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygucgila, H.; Konukb, A. Reserve estimation in multivariate mineral deposits using Geostatistics and GIS. J. Min. Sci. 2015, 51(5), 993–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fa, G.; Yuan, R; Wang, Z. ; Lan, J.; Zhao, J.; Xia, M.; Cai, D.; Yi, Y. CBM Resources/reserves classification and evaluation based on PRMS rules. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 121, 052080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.A.; Friederich, M.C. Defining uncertainty: Comparing resource/reserve classification systems for coal and coal seam gas. Energies 2021, 14, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saakyan, M.; Kuramshin, R. Oil and fuel gas reserves and resources classification. Some methodological explanations and proposals for its application. Geomodel 2018, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzemień, A.; Fernández, P.R.; Sánchez, A.S.; Álvarez, I.D. Beyond the pan-european standard for reporting of exploration results, mineral resources and reserves. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, M. Vukas, R. On the harmonisation of Serbian classification and accompanying regulations on resources/reserves of solid minerals with the PERC standard. Eur. Geol. 2016, 41, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baraković, D. Classification of labels and points of non-metallic mineral raw materials by pan-european reserves & resources reporting committee –PERC. J. Fac. Min. Geol. Civ. Eng. 2019, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, W. Review of standards for mineral resources and reserves estimation in Korea (in Korean). J. Korean Soc. Miner. Energy Resour. Eng. 2019, 56(2), 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Wang, T. Research on reserve classification of solid mineral resources in China and Western Countries. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 631, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Yq.; Ma, Y. Mapping between “Classifications for Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves (GB/T 17766-2020)” and “United Nations Framework Classification for Resources (UNFC-2019)”. In Proceedings of the International Field Exploration and Development Conference 2020; Lin, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, Singapore, 2021; pp. 3405–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumakor-Dupey, N.K.; Arya, S. Machine Learning—A Review of Applications in Mineral Resource Estimation. Energies 2021, 14, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Xia, Q. Developments in quantitative assessment and modeling of mineral resource potential: An overview. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 1825–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominy, S.C.; Noppé, M.A.; Annels., A.E. Errors and uncertainty in mineral resource and ore reserve estimation: The importance of getting it right. Explor. Min. Geol. 2002, 11, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Bian, Z.; Yuan, J.; Xu, F.; Cheng, Y. Mineral reserves optimization based on improved group AHP. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2014, 20(4), 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, L.D.; Robinson, G.R.; Nassar, N.T. Mineral Resources: Reserves, Peak Production and the Future. Resour. 2016, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drielsma, J.A.; Russell-Vaccari, A.J.; Drnek, T.; Brady, T.; Weihed, P.; Mistry, M.; Simbor, L.P. Mineral resources in life cycle impact assessment—defining the path forward. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revuelta, M.B. Mineral Resources: From Exploration to Sustainability Assessment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderegger, T.; Berger, M.; Alvarenga, R.; Bach, V.; Cimprich, A.; Dewulf, J.; Frischknecht, R.; Guinée, J.; Helbig, C.; Huppertz, T.; Jolliet, O.; Motoshita, M.; Northey, S.; Rugani, B.; Schrijvers, D.; Schulze, R.; Sonnemann, G.; Valero, A.; Weidema, B.P.; Young, S.B. Mineral resources in life cycle impact assessment—part I: a critical review of existing methods. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowitt, S.M.; McNulty, B.A. Geology and mining: Mineral resources and reserves: Their estimation, use, and abuse. SEG Discov. 2021, 125, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagmolen, S.; Innecco, P. State of codes and standards for the reporting of mineral resources and reserves. Min. Eng. 2024, 76(10), 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Equator Principles. The Equator Principles. Available online: https://equator-principles.com/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- IRMA. Introduction to IRMA. Available online: https://responsiblemining.net/about/about-us/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- GRI. The global leader for sustainability reporting. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Černý, P.; Ercit, T.S. The classification of Granitic Pegmatites revisited. Can. Mineral. 2005, 43(6), 2005–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa-Soares, A.C.; Chaves, M.L.S.C.; Scholz, R.; Dias, C.H. PEG2009 pre-symposium field trip guide: eastern Brazilian pegmatite province (Minas Gerais). Estudos Geológicos 2022, 32, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzal, C.B.; Silva, J.M.; Jaques, D.S.; Santos, R.C.P. An overview of lithium mining in Brazil: From artisanal extraction to large-scale production. Resour. Policy 2025, 100, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBL. Nossas operações (in Portuguese). Available in: https://www.cblitio.com.br/nossas-opera%C3%A7%C3%B5es. (accessed on 02 August 2025).

| MR³ Index Classes | Corresponding Weights |

|---|---|

| Competence | 15% |

| Transparency | 15% |

| Materiality | 30% |

| Modifying factors | 40% |

| Sub-class | Type | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mineral Resources CP/QP |

Binary | Demonstrate the presence of a CP/QP responsible for mineral resources | Hire a qualified CP/QP for mineral resources |

|

Mineral Reserves CP/QP |

Binary | Demonstrate the presence of a CP/QP responsible for mineral reserves and economic evaluation | Hire a qualified CP/QP for mineral reserves and economic analysis |

| Sub-class | Type | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exploration Results Disclosure |

Scaled | Clear disclosure of exploration techniques and results | Review by a qualified professional; correct omissions and inconsistencies |

| Mineral Resource Modelling Disclosure | Scaled | Consistent explanation of resource modelling techniques and parameters | Review by a qualified professional; correct omissions and inconsistencies |

| Mineral Reserve Modelling Disclosure | Scaled | Detailed explanation of reserve conversion methodology and economic assessment | Review by a qualified professional; correct omissions and inconsistencies |

| Sub-class | Type | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosure of Key Risks and Constraints | Scaled | Explicit discussion of technical and project risks | Conduct structured risk assessment and disclose in report |

| Disclosure of Economic Assumptions | Scaled | Clear presentation of all key economic assumptions | Revise and justify economic inputs clearly |

| Consistency in Technical Narrative | Scaled | Alignment between quantitative estimates and narrative | Reconcile discrepancies between data and narrative |

| Consistency in Drillhole Reconciliation | Binary | Alignment between drill cores and their corresponding description | Make available the drill cores and reconcile the information |

| Sub-class | Type | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mining, Processing, and Metallurgical Factors | Scaled | Detailed mine planning, processing, and metallurgical studies with supporting data | Update studies and improve reconciliation under technical supervision |

|

Inferred Resources Confidence for Production |

Scaled | Historical records or proof of homogeneity among resources categories (operating mines) | Enhance QAQC, reconciliation, and classification procedures |

|

Economic, Market, and Infrastructure Factors |

Scaled | Current and justifiable economic assumptions and infrastructure access | Update economic models and infrastructure assessments |

|

Regulatory and Legal Factors |

Scaled | Legal compliance with mining rights, permits, and regulations | Regularize legal standing and obtain missing documentation |

| Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) | Scaled | Disclosure of ESG performance, policies, and governance structures | Implement and disclose ESG frameworks and indicators |

| Tailings Monitoring | Scaled | Detailed tailing disposal and monitoring plan, based on a geotechnical report and in accordance with legislation. | Develop actions to ensure safety and compliance with current legislation |

| Sub-class | Score | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral Resources CP/QP |  |

The company proved the presence of a CP/QP responsible for mineral resources | Not required |

| Mineral Reserves CP/QP |  |

The company proved the presence of a CP/QP responsible for mineral reserves and economic evaluation | Not required |

| Sub-class | Score | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exploration Results Disclosure |

|

The exploration report was approved by the government agency and presents a clear disclosure of techniques and results | Not required |

| Mineral Resource Modelling Disclosure |  |

The mineral resource report was approved by the government agency and provides a consistent explanation of resource modelling techniques and parameters | Not required |

| Mineral Reserve Modelling Disclosure |  |

The mineral reserve report was approved by the government agency and provides a detailed explanation of reserve conversion methodology and economic assessment | Not required |

| Sub-class | Score | Compliance Condition | Non-Compliance Action |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Disclosure of Key Risks and Constraints |

|

The report presents the results and analysis of the operational, technical, and economic aspects, including the main risks and potential constraints, as well as measures to mitigate these risks, but a quantified classification of the risks by probability and impact was not provided and the mitigation measures were superficial | Add more detail on risk prioritization and implementation of mitigation measures |

|

Disclosure of Economic Assumptions |

|

Economic assumptions detailing revenue sources, unit costs, and an analysis of capital and operating expenses has been shown, as well as sensitivity analyses have been included, but some of the assumptions are based on a simplified market forecast and the sensitivity analysis can be improved | Present stronger economic assumptions and a complete sensitivity analysis of the enterprise |

|

Consistency in Technical Narrative |

|

The provided document demonstrates consistency between the geological model, mine planning, and financial projections regarding modifying factors, avoiding contradictions in tonnage, grade distribution, or scheduling, but further improvements can be made | Add more detail on how the updated geological model relates to past performance regarding geotechnical, metallurgical, and economic factors in the production schedule |

|

Consistency in Drillhole Reconciliation |

|

An alignment between drill cores and their corresponding description was proven | Not required |

| License | License number | Government Agency | Year of issue | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploration Permit | ANM 831.216/1997 | National Mining Agency | 2006 | Current (Extension) |

| Mining License | ANM 807.022/1971 ANM 807.652/1971 |

National Mining Agency | 2023 2023 |

Current |

| Mining Operations | LO 128/2015 | State Environmental Agency | 2015 | Current (Extension) |

| Alteration | LAC 5575/2021 | State Environmental Agency | 2021 | Current (Extension) |

| Fuel Station | LAS 1638/2023 | State Environmental Agency | 2023 | Current (Extension) |

| Access Roads | LAS-RAS 331/2020 | State Environmental Agency | 2020 | Current (Extension) |

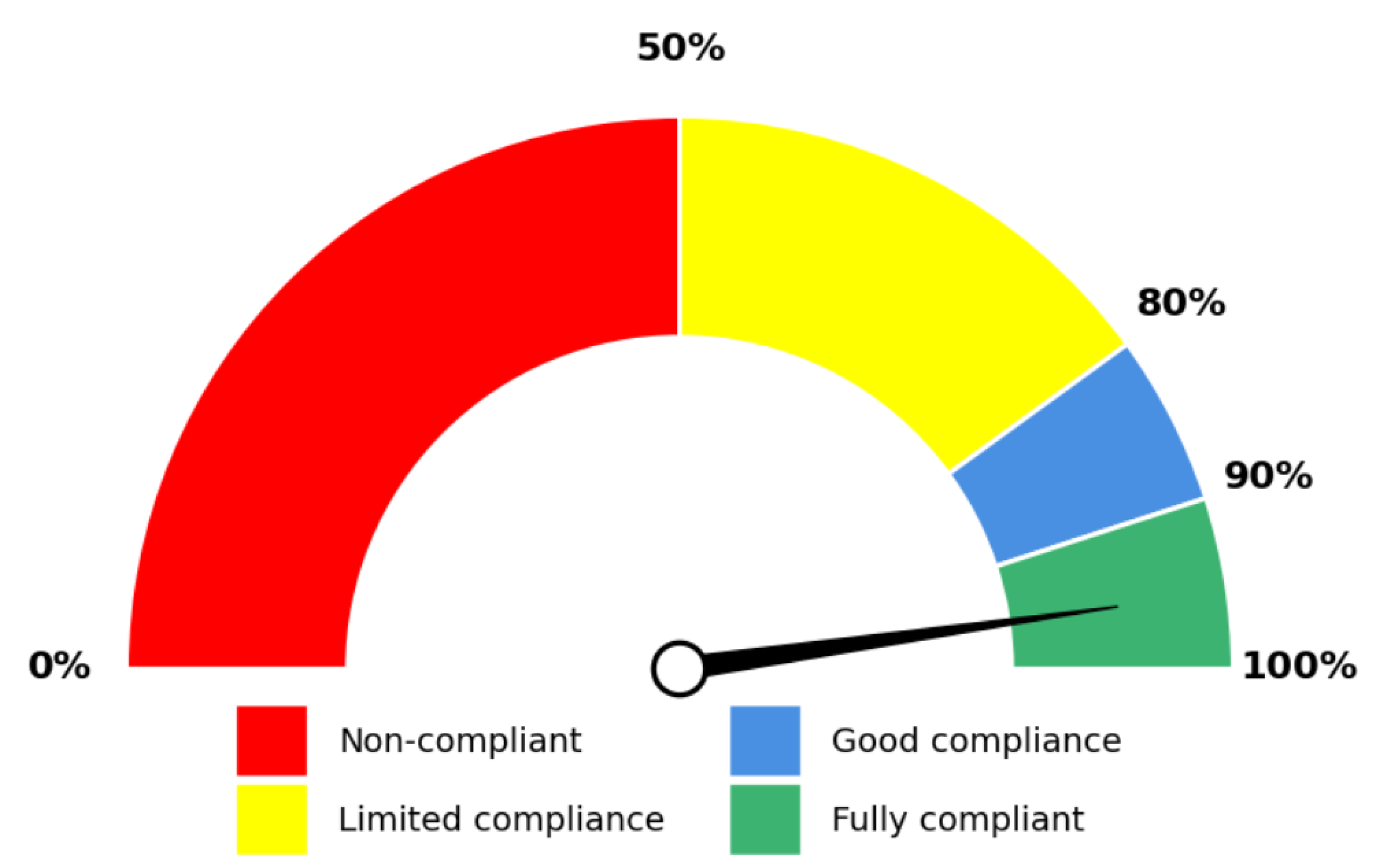

| MR³ Index Classes | Scores | Weights | Weighted Averages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competence | 100% | 15% | 15% |

| Transparency | 100% | 15% | 15% |

| Materiality | 85% | 30% | 25.5% |

| Modifying factors | 100% | 40% | 40% |

| Final Score | 95.5% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).