1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (

Hp) is a Gram-negative bacterium classified by the World Health Organization as a Group I carcinogen[

1], and its infection is closely associated with the development of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer[

2]. Approximately 50% of the global population is infected with this bacterium, with infection rates in China ranging from 40% to 60% [

3,

4], Currently, the first-line clinical treatment for

Hp infection is the “proton pump inhibitor + bismuth agent + two antibiotics” quadruple therapy, or the “proton pump inhibitor + two antibiotics” triple therapy [

5]. However, in recent years, the drawbacks of antibiotic therapy have become increasingly evident. Due to its single target, it can lead to bacterial resistance, disrupt gut microbiota balance, and reduce patient compliance, ultimately causing decreased eradication rates and even relapse [

6]. Studies show that the resistance rate to clarithromycin exceeds 20% [

7], and the relapse rate after

Hp eradication failure is about 1% to 5%, while the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains further reduces the success rate of subsequent treatments [

8]. Therefore, finding non-antibiotic alternatives with multiple targets, pathways, and high activity is of significant clinical importance.

In recent years, with the continuous advancement of research on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the development of active monomer components with clear pharmacological activity from TCM has become an important global direction in drug development. The successful development of active monomer compounds from plant medicines, such as artemisinin for malaria treatment, berberine for intestinal infections, triptolide for immune diseases, and anticancer drugs like paclitaxel and vincristine [

9], has provided valuable examples for drug development. In this context, indigo (IND) and indirubin (IRN) have considerable development potential and application value.

IND and IRN are primarily derived from Polygonaceae plants such as

Isatis tinctoria [

10], Brassicaceae plants such as

Isatis indigotica [

11], and Plumbaginaceae plants such as

Plumbago species [

12], with the dried roots (Banlangen) and leaves (Daqingye) of

Isatis indigotica serving as their main medicinal sources. Its processed product, Qingdai (with IND content ≥5%), has been used as a dye and medicinal material since the Xia Dynasty. According to the 2020 edition of the

Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 edition), IND is listed as a quality control marker for Qingdai and Daqingye. Traditionally, IND-containing plants have been used for clearing heat and detoxification, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory purposes, anti-infection, and anticancer effects [

13,

14], and their related compound preparations are widely applied in the treatment of gastric-heat type ulcers, oral mucosal diseases, and various infectious inflammations. They have also shown certain therapeutic effects in improving right ventricular function in patients with acute pulmonary embolism [

15]. Modern pharmacological studies have demonstrated that IND possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities [

16], exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against

Staphylococcus aureus and

Escherichia coli (MIC: 64–128 µg/mL), and shows antiviral activity against influenza virus and herpes virus [

17,

18]. Additionally, IND can inhibit cell proliferation and protect against ultraviolet-induced damage [

19,

20].

As a metabolite of IND, IRN exhibits even broader pharmacological potential. IRN has been approved as a marketed drug for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia and has shown efficacy in inflammatory diseases such as liver-stomach heat-type gastritis, psoriasis, and ulcerative colitis [

21]. Studies have found that IRN exerts a more potent inhibitory effect on

S. aureus (MIC: 8 µg/mL) [

22] and can attenuate inflammation in LPS-induced mouse mastitis models by downregulating IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels and inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB/MAPKs signaling pathway [

23]. Furthermore, IRN and its derivatives have additional activities, including platelet regulation, antiviral effects, and neuroprotection [

24,

25,

26]. Overall, both IND and IRN exhibit favorable clinical safety and broad-spectrum antibacterial potential. However, despite their confirmed activity against infections—particularly bacterial, viral, and inflammatory responses—their direct inhibitory effects on

Hp and the associated mechanisms remain poorly understood and have not been systematically investigated.

Recent results from our research group have shown that extracts from different parts of Isatis indigotica (Da Qing Ye, Ban Lan Gen, Qingdai) exhibit strong inhibitory activity against Hp, but whether their core bis-indole components, IND and IRN, are involved in this antibacterial process remains to be systematically studied. It is noteworthy that as isomers (molecular formula C16H10N2O2), the structural-activity differences between them arise from the spatial specificity of their indole ring coupling sites. IND forms a linear coupling structure through the C3-C3’ position, while IRN constructs an angularly deflected structure through the C3-C2’ position. This structural difference may result in significant variations in their target affinity and biological activity. Although the two structures are complementary, whether their combination produces a synergistic antibacterial effect remains unknown.

In this study, we found that the MIC of IND and IRN against the standard strain ATCC 43504 of Hp were 2.5 µg/mL and 10 µg/mL, respectively, significantly better than the natural berberine (MIC: 16 µg/mL). However, their high hydrophobicity severely limits their clinical application potential.

Nanocarriers, due to their ability to penetrate biological membrane barriers, have become an important strategy for the delivery of drugs and functional components. Among these, protein-polysaccharide complex nanodelivery systems show great potential in improving the solubility and bioavailability of hydrophobic molecules, due to their unique physicochemical properties and biocompatibility. This study focuses on employing such composite carriers to encapsulate IND and IRN, with the aim of overcoming their high hydrophobicity and exploring the potential of their combined application in enhancing Hp activity.

Ovalbumin (OVA) was chosen as one of the core carrier materials due to its strong amphiphilicity [

27]. OVA can form self-assembled structures with hydrophobic “pockets” through precise spatial amphiphilic distribution [

28], efficiently encapsulating hydrophobic drugs and significantly improving their solubility and bioavailability. Numerous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of OVA composite carriers in encapsulating hydrophobic drugs. OVA-oligosaccharide complexes significantly improve the stability, controlled release, and bioavailability of quercetin [

29]. OVA-carboxymethyl cellulose sodium achieves more than 90% encapsulation of curcumin and enhances its antioxidant activity [

30]. OVA-carvone nanoparticles have an encapsulation rate of 91.86% at pH 9.0 and show antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

31]. OVA-sodium fucoidan composite nanocarriers encapsulating sennoside and tannic acid form delivery systems that enhance inhibition against Escherichia coli [

32].

Fucoidan was selected as another key component due to its excellent carrier properties and significant bioactivities. Clinical studies have shown that the combination of fucoidan with standard quadruple therapy can increase the

Hp eradication rate to 76.67% and alleviate antibiotic-associated gut microbiota dysbiosis [

33,

34]. Mechanistic studies have demonstrated that its

Hp effects involve downregulating urease activity, regulating gastric pepsinogen levels, interfering with

Hp adhesin

alpA function, and reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and IL-6, thus mitigating gastric inflammatory damage [

35]. In addition, fucoidan exhibits a wide range of bioactivities, including antitumor and gut regulatory effects [

36]. Previous studies have also reported that OVA and fucoidan can undergo electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions to form self-assembled nanostructures for the delivery of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), significantly enhancing its efficacy [

37], suggesting the great potential of this system for co-loading hydrophobic drugs such as IND and IRN. Similarly, chitosan–β-lactoglobulin self-assembled systems have verified the feasibility of co-delivering hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds, such as egg white peptides and curcumin [

38].

Therefore, the present study aims to construct food-grade self-assembled nanoparticles based on the electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions between OVA and fucoidan, to efficiently encapsulate the hydrophobic drugs IND and IRN and thereby improve their solubility. Leveraging the intrinsic anti-

Hp, anti-inflammatory, and gut-regulatory activities of fucoidan, this strategy is expected to achieve multi-target synergistic interventions against

Hp infection and enhance therapeutic efficacy. The resulting nanoparticles will be subjected to physicochemical characterization, followed by systematic evaluation of the antibacterial activity and synergistic potential of the drug monomers and their nanoformulations against both sensitive and drug-resistant

Hp strains using network pharmacology, molecular docking, in vitro assays, and untargeted metabolomics, with a preliminary exploration of the underlying mechanisms. This study is expected to provide an important theoretical foundation for the application of the hydrophobic drugs IND and IRN in

Hp treatment. It also offers a potential mechanistic explanation for the high sensitivity and specificity demonstrated by FDA-approved contrast agent IND Carmine in the detection of

Hp-related gastritis [

39]. Moreover, the nanoparticle-based strategy to enhance drug solubility provides a novel perspective for the structural optimization of indole-based compounds and their potential in the development of anti-

Hp therapeutics.

4. Discussion

Hp infection is a common chronic bacterial infection worldwide, associated with gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer [

47]. Although proton pump inhibitor-based antibiotic therapy remains the first-line treatment [

48], antibiotic resistance significantly reduces its efficacy. Screening TCM active monomers with multi-target effects and low resistance potential represents a promising strategy. IND and IRN are bis-indole TCM monomers with heat-clearing, detoxifying, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties, and good safety profiles, but their hydrophobicity limits bioavailability. To improve solubility, this study encapsulated IND and IRN in OVA/fucoidan self-assembled nanoparticles, enhancing drug loading and stability through electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond interactions, while leveraging the intrinsic antibacterial activity of the carriers.

OFNPs form at pH 4.0, below the isoelectric point of OVA (pI ≈ 4.5), rendering OVA positively charged. It self-assembles with negatively charged fucoidan through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, ultimately forming stable nanoparticles. Experiments showed that at a total concentration of 0.75 mg/mL, OFNPs exhibited optimal dispersibility, with a particle size of 142.6 ± 1.2 nm, PDI of 0.120 ± 0.001, and a Zeta potential of -33.4 ± 0.8 mV. Increasing the concentration elevated collision frequency, promoting fucoidan aggregation on the OVA surface, resulting in larger particle sizes and broader distribution. [

49]. FTIR analysis showed that the amide I band shifted from 1656 cm

−1 to 1648 cm

−1 and broadened, indicating hydrogen bond formation between OVA and fucoidan [

50] possibly accompanied by partial α-helix to β-sheet transition in the secondary structure [

51]. The weakening of the tyrosine peak suggested exposure of hydrophobic groups, enhancing hydrophobic interactions. The decrease in the S=O peak intensity and the appearance of a shoulder peak indicated electrostatic interactions between fucoidan sulfate groups and positively charged OVA residues. Additionally, the retention of C=O and C–O–C characteristic peaks, along with amide I/II band shifts, further confirmed multiple molecular interactions during complex formation. These interactions increased the rigidity of the protein secondary structure and suppressed molecular motion via hydrogen bonding, enhancing nanoparticle stability. Drug loading experiments revealed that increasing IND/IRN concentrations led to larger particle sizes, broader distributions, and reduced absolute Zeta potential, indicating a higher tendency for aggregation, consistent with SEM observations. At a loading concentration of 40 µg/mL, the particles exhibited optimal stability, with EE (68.64%) and LC (3.66%) at desirable levels, along with the strongest antibacterial activity. Notably, IND and IRN are normally soluble only in 100% DMSO, whereas the nanosystem developed in this study achieved effective encapsulation and loading under 50% DMSO, significantly improving their solubility. Overall, a preparation concentration of 0.75 mg/mL combined with a drug loading of 40 µg/mL provided the optimal balance of particle stability, uniformity, and anti-

HP activity, offering ideal conditions for subsequent drug delivery.

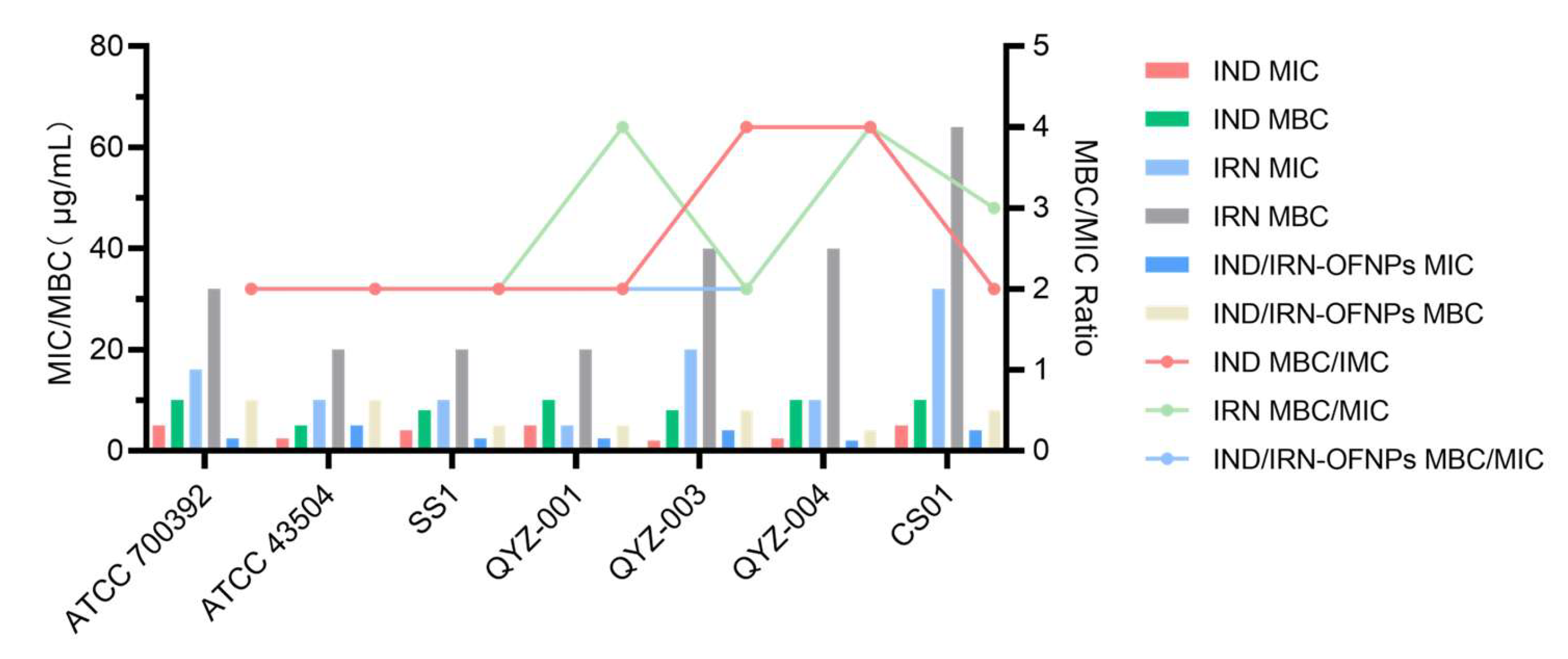

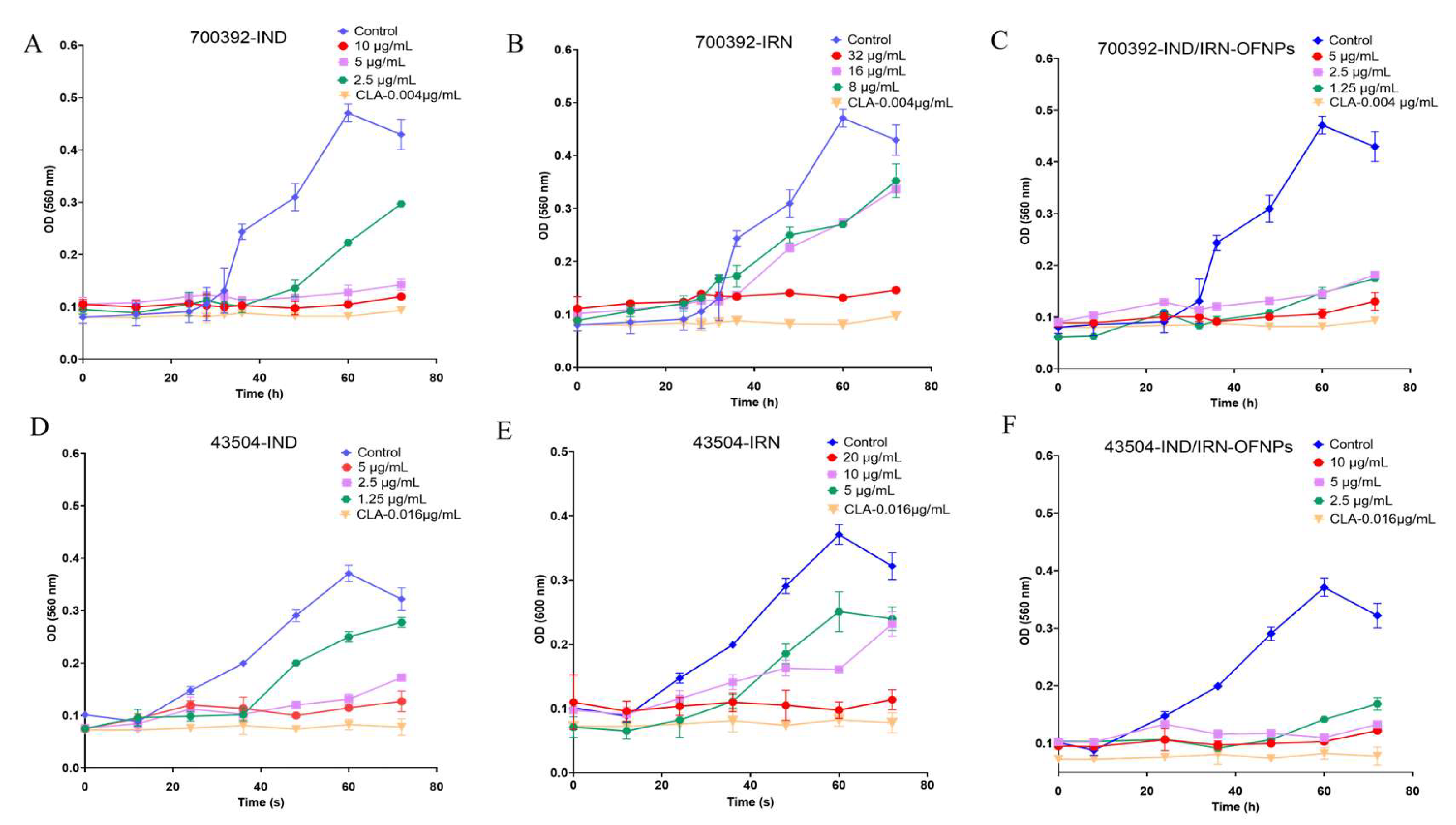

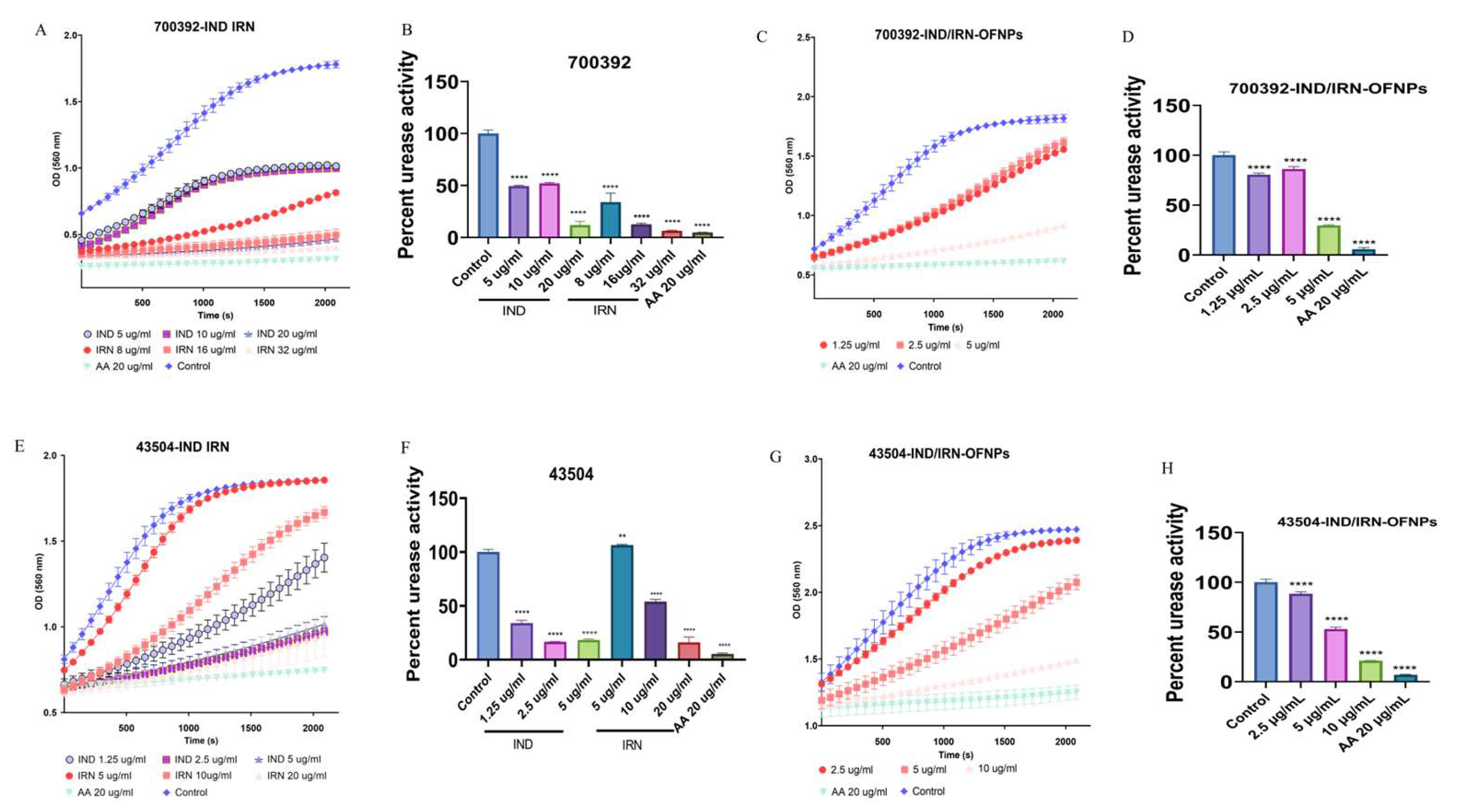

In vitro anti-Hp results showed that IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs (without removal of free drugs) exhibited significant inhibitory and bactericidal effects against both standard and clinically resistant strains. The blank carrier OFNPs had an MIC >375 µg/mL, indicating negligible antibacterial activity. Among the single drugs, IND had an MIC of 2-5 µg/mL, and IRN had an MIC of 5-32 µg/mL; in contrast, the MIC of IND/IRN-OFNPs was 2-5 µg/mL, lower than that of most single drugs, with stronger inhibitory effects against clinical strains, indicating that nanoencapsulation of the combined drugs markedly enhances antibacterial activity and holds greater potential for treating clinical Hp infections. Time-kill assays further demonstrated that IND/IRN-OFNPs at 1.25 µg/mL could inhibit the growth of ATCC 700392, with dose-dependent effects clearly superior to single drugs, reflecting both the high antibacterial efficiency at low concentrations and providing dynamic evidence of the synergistic effect of IND and IRN. After 72 h of treatment, all drug groups exhibited MBC/MIC ≤4, indicating not only growth inhibition but also complete eradication of Hp, confirming the efficacy and potential clinical value of IND, IRN, and the nano-drug delivery system in anti-Hp therapy.

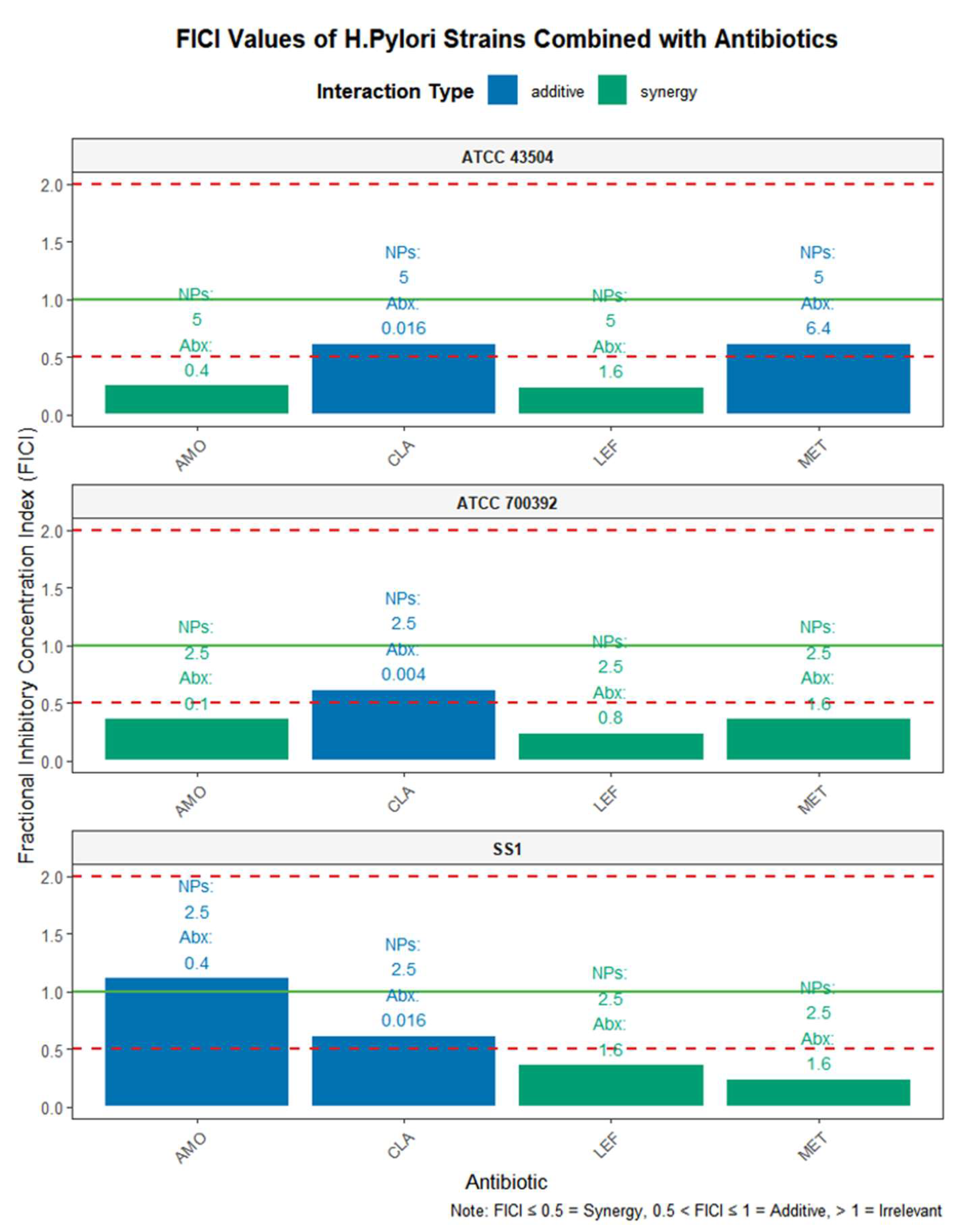

Considering the issue of clinical antibiotic resistance, this study employed the checkerboard dilution method to systematically evaluate the combined effects of IND/IRN-OFNPs with four commonly used antibiotics, while also assessing the intrinsic synergistic effect of IND and IRN. The results showed that IND/IRN-OFNPs generally exhibited synergistic interactions with the antibiotics, and when combined with MET or LEF, the MIC values decreased to half of those observed with single-drug use, demonstrating inhibitory effects that exceeded simple additive outcomes. This indicates that the regimen not only has potential for dose optimization but may also reduce antibiotic-related side effects and lower the risk of resistance in clinical settings. The antibacterial effect of the physical combination of IND and IRN was superior to that of the individual drugs, exhibiting synergistic or additive effects, while the blank carrier showed no significant activity. Nanoencapsulation further enhanced the antibacterial efficacy of IND/IRN-OFNPs, confirming that nanoencapsulation can significantly improve the combined synergistic antibacterial effect of the two drugs.

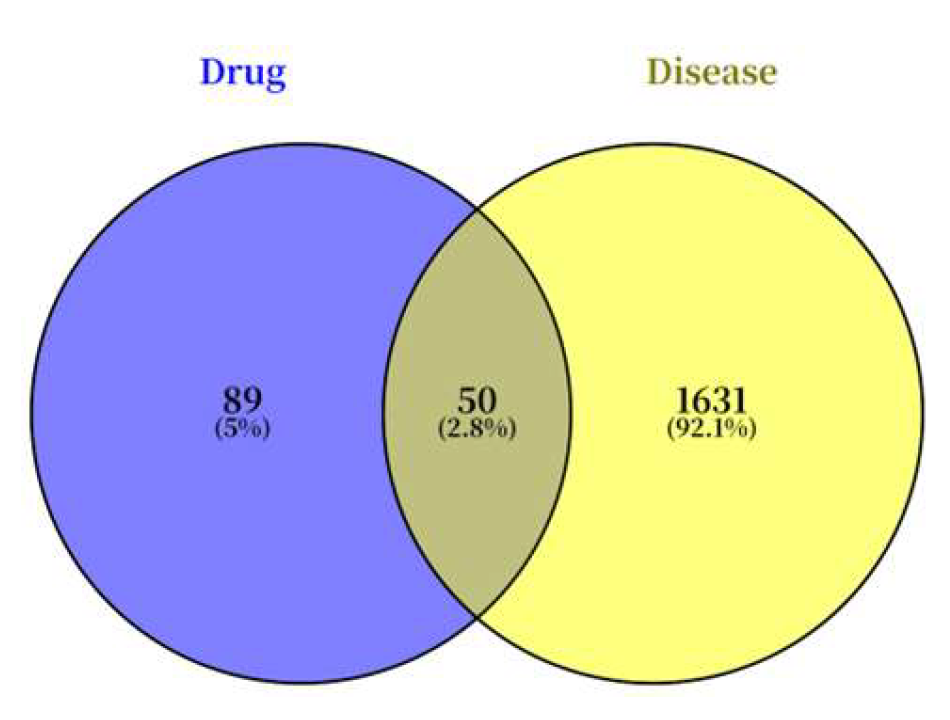

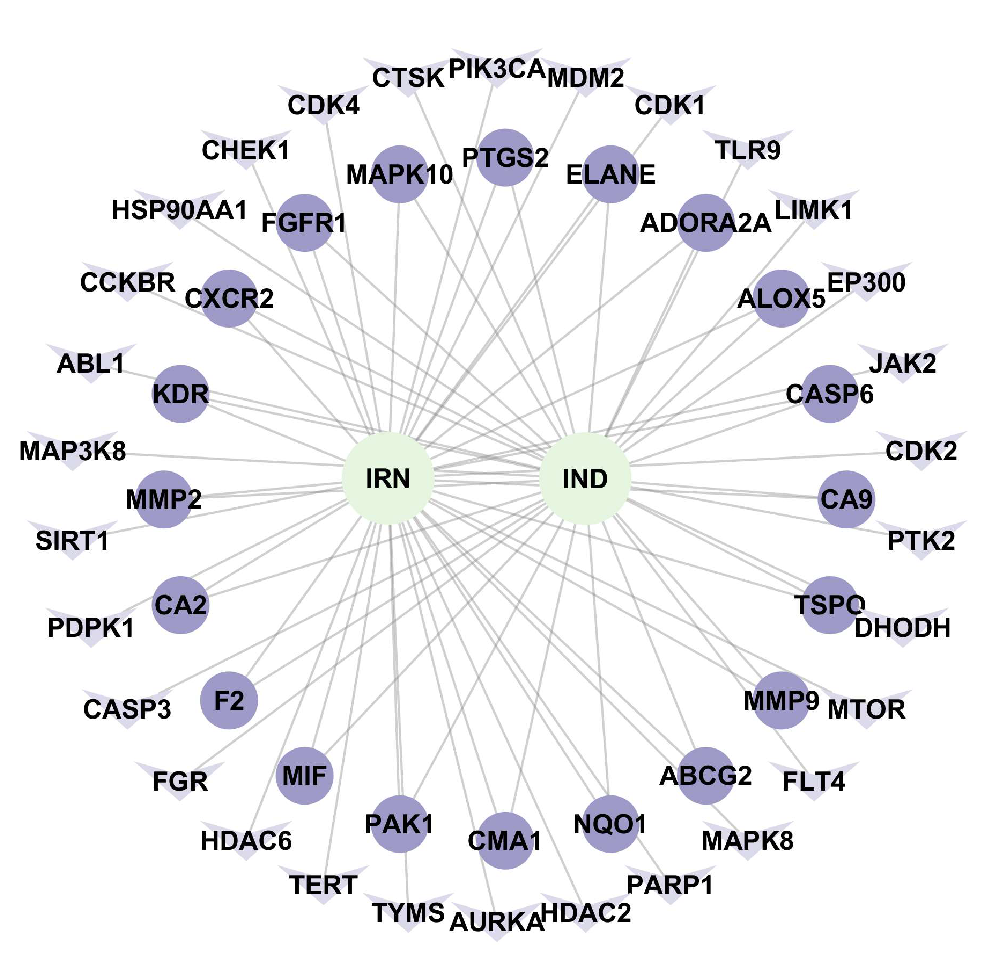

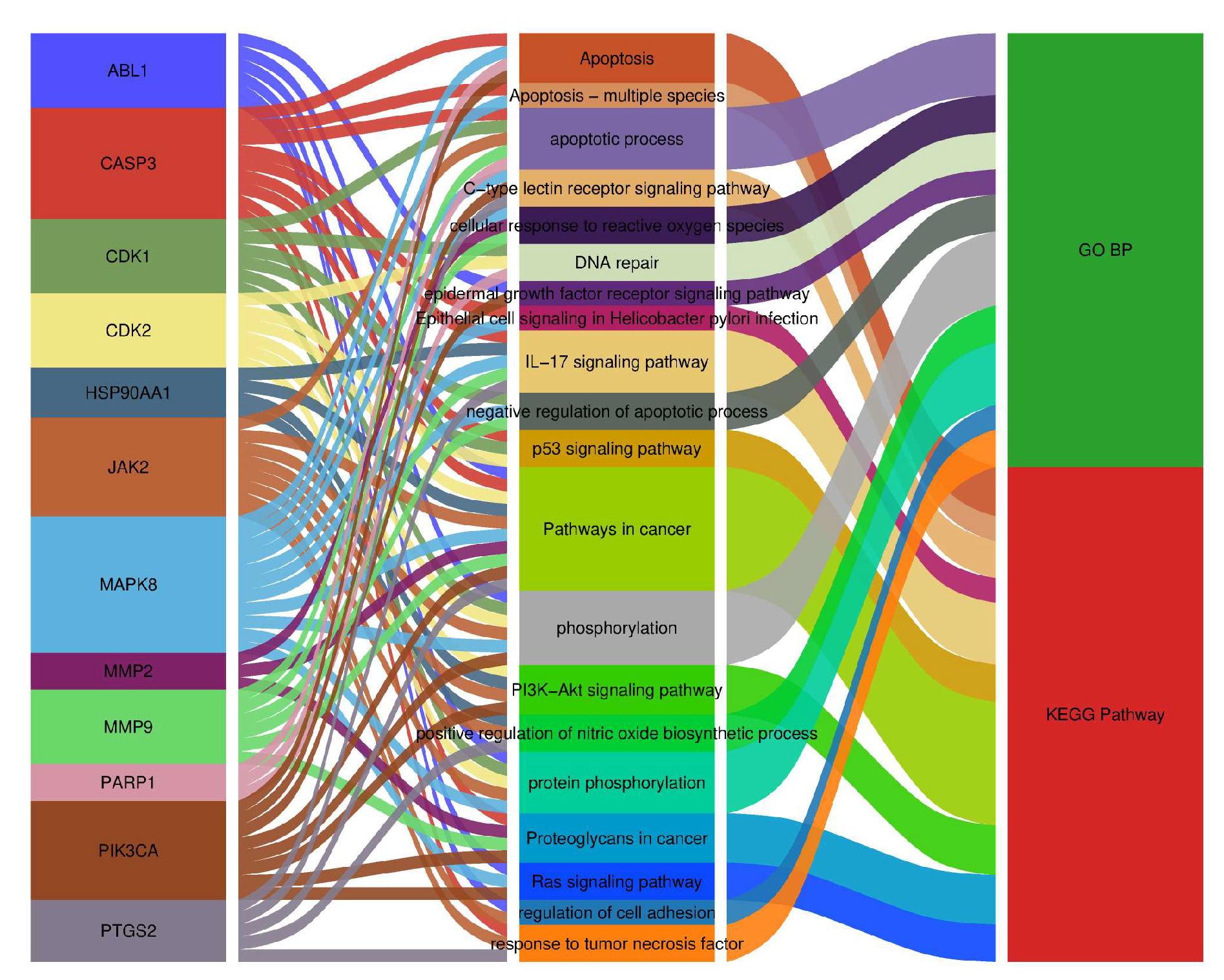

Both single compounds and crude extracts from traditional Chinese medicine exhibit multi-target and multi-pathway regulatory characteristics. In this study, a combination of network pharmacology and experimental validation was used to preliminarily elucidate the anti-Hp mechanisms of IND and IRN. Integration of drug and disease databases identified 50 shared potential targets for IND/IRN. The constructed “drug–disease–target” network revealed that the two compounds form a complementary, multidimensional network through core and specific targets, reflecting systematic and synergistic regulatory features.

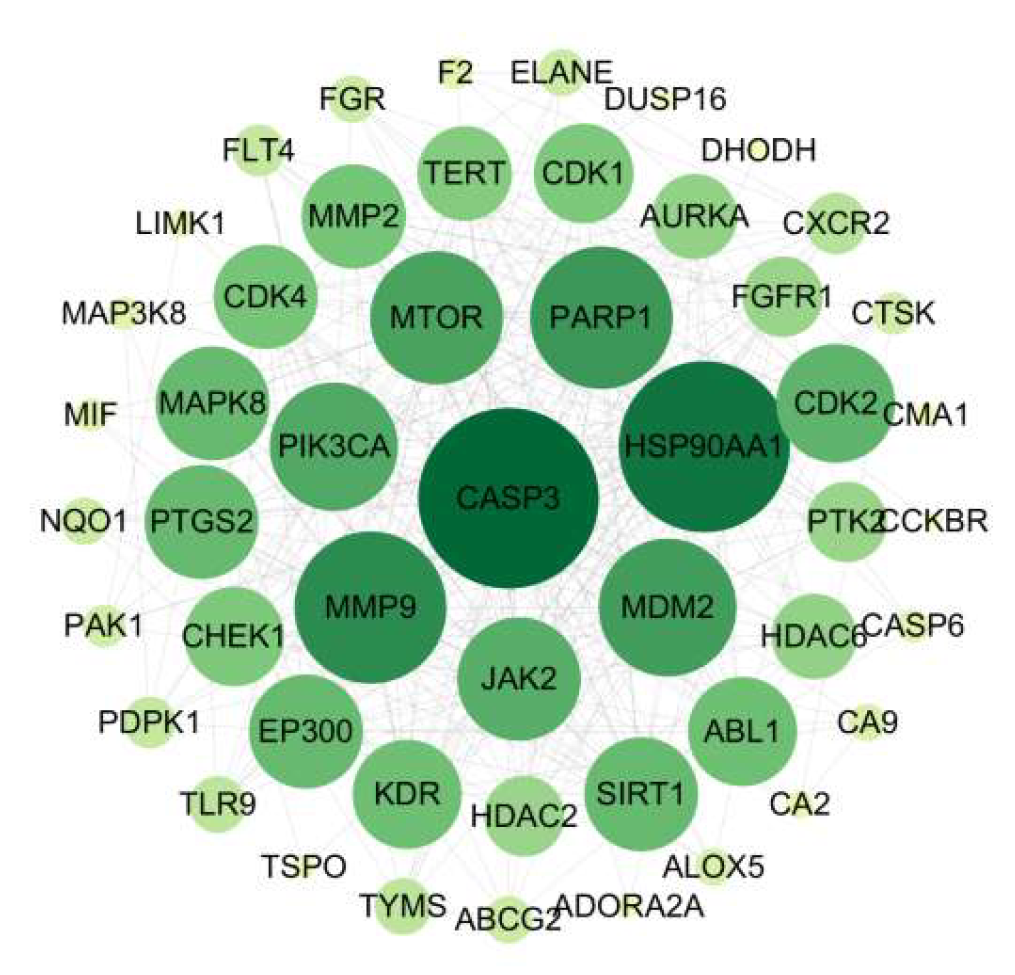

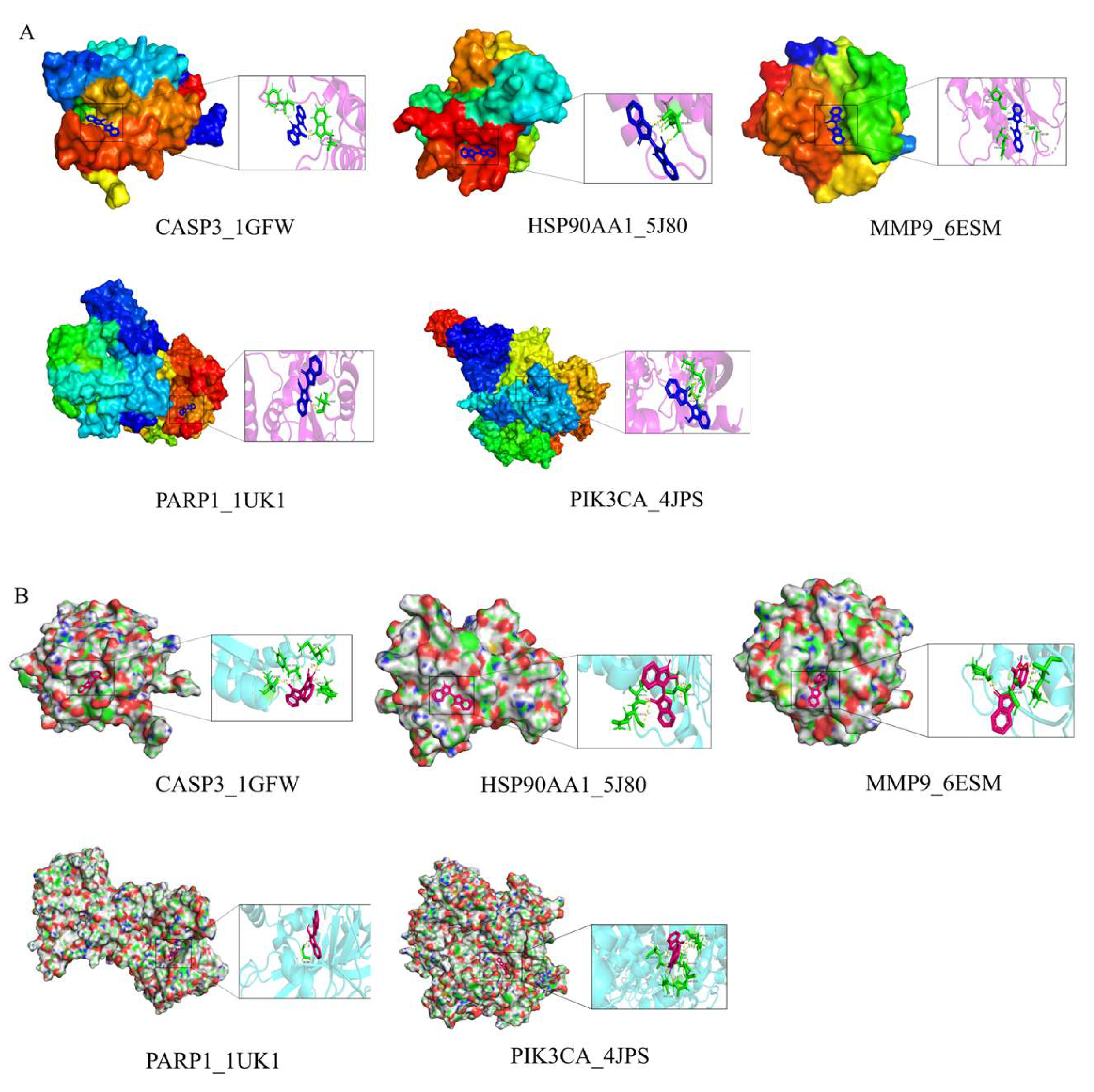

Molecular functions in biological systems typically rely on the coordinated action of proteins, mediated through dynamic PPI networks [

52]. In this study, network topology analysis identified 12 core targets, with the top five by degree-CASP3, HSP90AA1, PARP1, PIK3CA, and MMP9-potentially playing key roles in the anti-

Hp activity of IND and IRN.CASP3 (Caspase-3), a member of the cysteine-aspartic protease family, is a key executor of apoptosis, inducing DNA fragmentation and cell disassembly by cleaving PARP1 and cytoskeletal proteins [

53,

54]. During

Hp infection, CASP3 can be activated via the death receptor-mediated pathway through Caspase-8 [

55,

56] or the mitochondrial pathway involving cytochrome c release and Apaf-1/Caspase-9 complex activation [

57,

58]. Moderate activation helps eliminate infected cells, whereas excessive apoptosis may compromise the mucosal barrier, promoting chronic inflammation and precancerous lesions. [

59]. Heat shock protein 90 alpha family member 1 (HSP90AA1) is a highly conserved chaperone protein that plays an important role in cell cycle regulation, gene modification, DNA damage response, and the development of various human cancers [

60]. The

Hp virulence factor CagA relies on HSP90AA1 for stability and promotes host inflammatory responses. Inhibiting HSP90AA1 can reduce the activity of

Hp virulence proteins and reshape the host immune response [

61]. PARP1 (Poly ADP-ribose polymerase 1) is involved in DNA damage repair, and it regulates inflammation and cell death [

62]. Recent studies have found that PARP1 activates the AMPKα pathway to extend lifespan [

63]. In

Hp infection, excessive PARP1 activation may promote the release of the inflammatory factor NF-κB, exacerbating gastric mucosal damage [

64]. PIK3CA (Phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha), a member of the PI3K family, is the second most common mutated cancer gene [

65], with mutations detected in over 10% of eight types of cancers. This gene promotes cell proliferation, survival, and metabolism by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [

66]. Upon infection of gastric epithelial cells by

Hp, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways are activated, inducing malignant transformation of epithelial cells through processes such as apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation [

67]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix and are involved in various degenerative and inflammatory diseases. In

Hp infection, they are closely associated with the progression of gastritis, gastric/duodenal ulcers, and gastric cancer. MMP9 mediates

Hp-induced gastric cancer invasion and metastasis via signal protein 5A, with its expression depending on the integrity of

Hp’s cag pathogenicity island (cag-PAI) [

68]. These key proteins play central roles in signal transduction, metabolic homeostasis, DNA repair, and the balance between proliferation and apoptosis in host cells. They are likely involved in multiple pathogenic processes during

Hp infection. IND and IRN may exert their effects through multi-target synergy, interfering with the activity and expression of these proteins, thereby affecting

Hp’s invasion, virulence factor secretion, and bacterial metabolic pathways. This, in turn, inhibits

Hp’s infection and reproduction in the gastric mucosa, achieving an anti-

Hp effect.

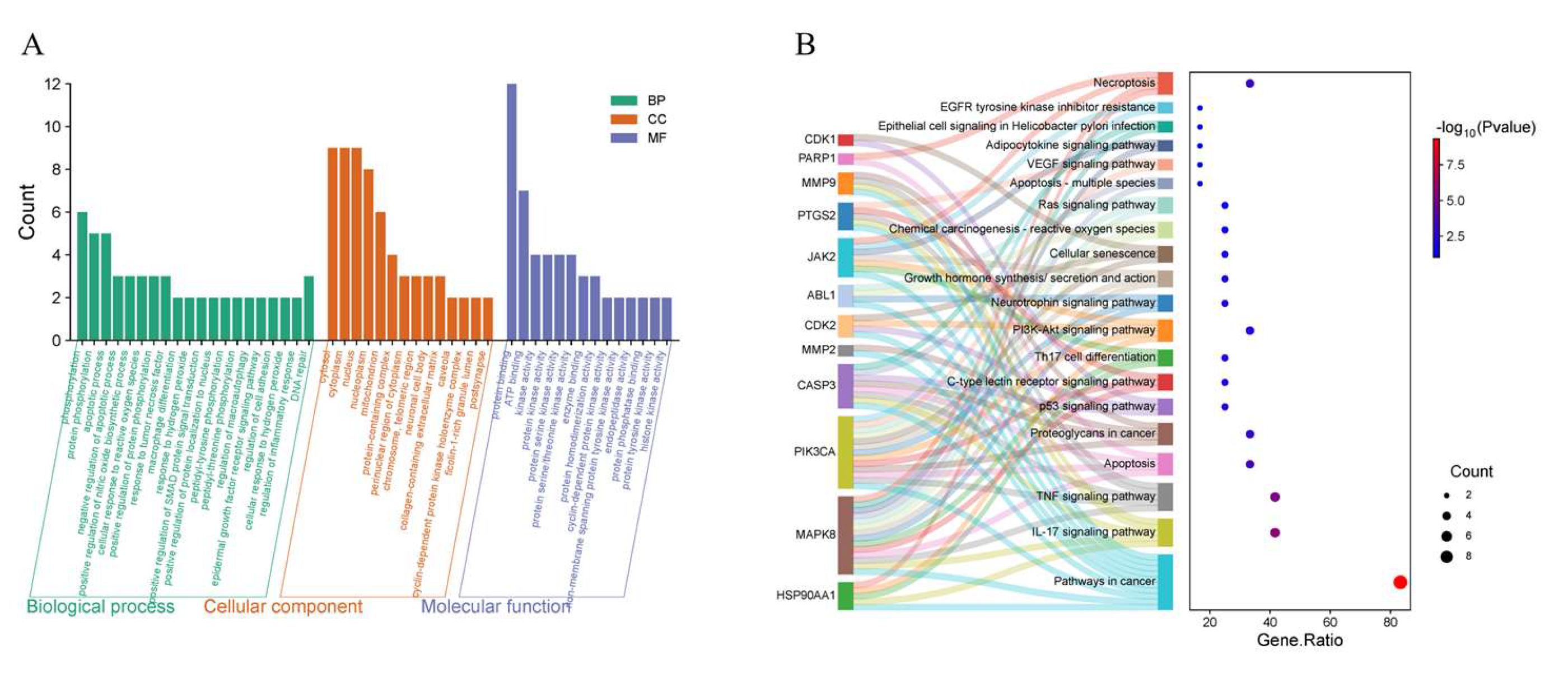

GO enrichment analysis indicated that IND and IRN primarily target the cytoplasmic matrix, nucleoplasm, nucleus, and mitochondria, suggesting that they may exert anti-Hp effects by modulating cellular structure and function. Their molecular functions involve ATP binding, protein phosphatase binding, protein binding, and protein kinase activity, indicating potential regulation of downstream biological processes through target modulation. Furthermore, IND and IRN affect negative regulation of apoptosis, cellular responses to reactive oxygen species, inflammation regulation, DNA damage repair, and tumor necrosis factor-mediated responses, suggesting that they may inhibit Hp growth and alleviate gastrointestinal mucosal inflammation by suppressing inflammatory responses and preventing genomic instability.

KEGG enrichment analysis indicates that the effects of IND and IRN against

Hp are mediated through synergistic regulation of multiple targets and pathways, primarily involving

Hp–infected epithelial cell signaling, TNF signaling, PI3K-Akt signaling, IL-17 signaling, Th17 cell differentiation, and cancer-related pathways.

Hp infection activates these signaling networks, modulating epithelial cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation, while creating a microenvironment favorable for bacterial colonization and pathogenicity [

69]. Studies have shown that

Hp infection significantly upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in the gastric mucosa [

70] and induces local differentiation and activation of Th17 cells. Activated Th17 cells secrete large amounts of IL-17, and the concomitant elevation of TNF-α and IL-17 synergistically exacerbates inflammation and is closely associated with gastric precancerous lesions [

71,

72]. Aberrant activation of PI3K-Akt signaling promotes AKT phosphorylation, regulating cell survival and proliferation, and represents a key mechanism in

Hp–induced early gastric carcinogenesis [

73,

74]. Epidemiological data indicate that approximately 90% of non-cardia gastric cancers are associated with

Hp infection, which has been classified as a Group I carcinogen by the IARC. Previous studies have demonstrated that IND and IRN exhibit anticancer activity against various cancers [

75,

76], and their anticancer properties align with the cancer-related pathways enriched in this study, suggesting that they may exert therapeutic effects by blocking

Hp–driven carcinogenesis.

Notably, MAPK8 plays a critical regulatory role, participating in over 50% of the core biological processes and KEGG pathways. Molecular docking demonstrates that IND and IRN bind well to core targets such as PARP1 and MMP9, supporting their potential to inhibit Hp–related pathological progression through modulation of these targets. Overall, the core targets of IND and IRN may achieve multi-dimensional intervention in Hp infection and associated pathological damage via synergistic regulation of multi-target, multi-pathway signaling networks.

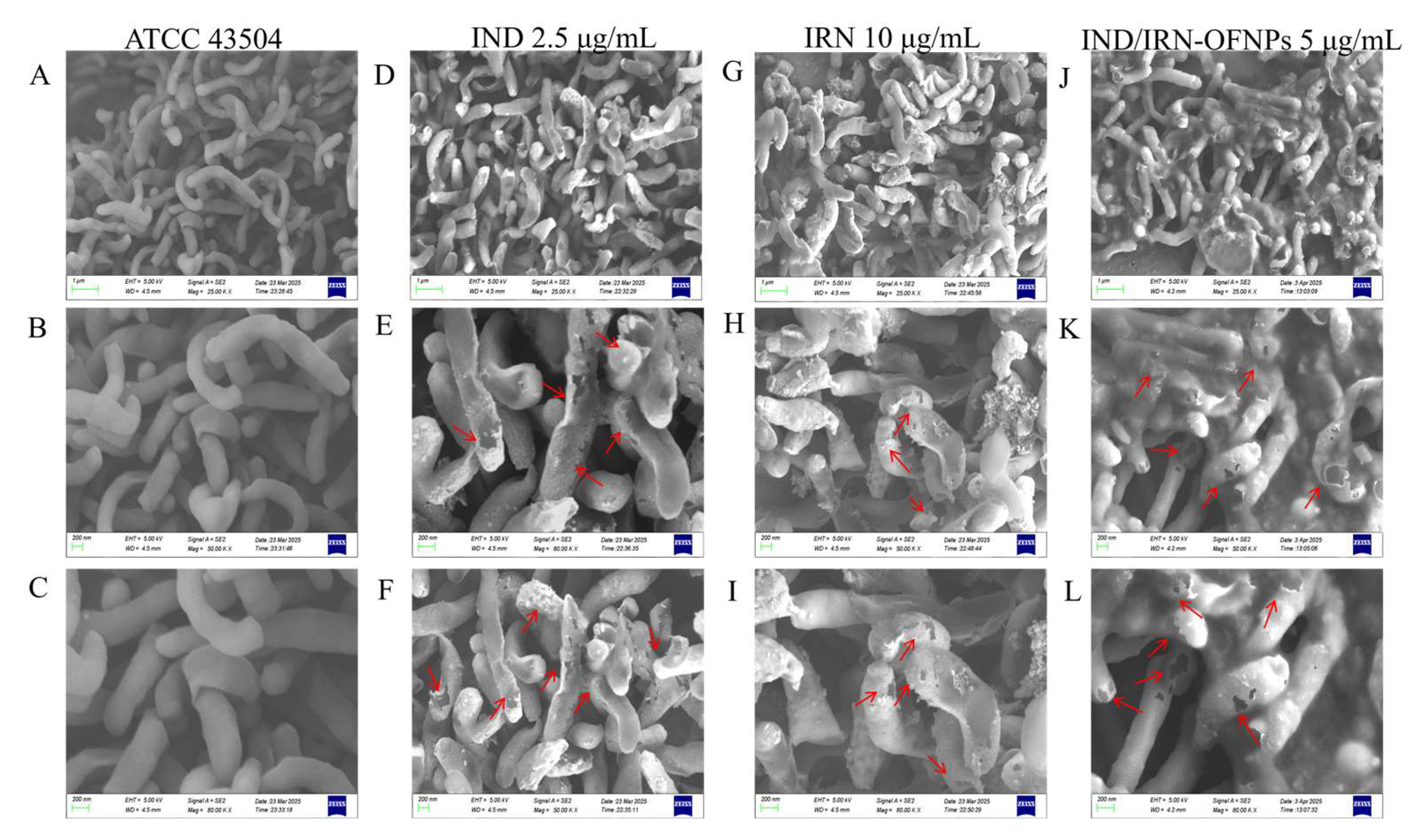

Studies have shown that

Hp can be eradicated by altering bacterial morphology and disrupting cell membrane integrity [

77]. SEM observations revealed that after 12 h of IRN or IND treatment,

Hp exhibited shrinkage, cytoplasmic leakage, and cell fragmentation, suggesting that these compounds may exert bactericidal effects by compromising membrane integrity. This mechanism differs from antibiotics like clarithromycin, which act indirectly by inhibiting protein synthesis [

78], further supporting the multi-target antibacterial properties of IRN and IND, consistent with network pharmacology predictions.

Network pharmacology analysis suggested that IND and IRN may interfere with epithelial cell signaling pathways associated with

Hp infection, thereby affecting bacterial colonization and pathogenicity. AlpA mediates specific adhesion to gastric epithelial cells and is essential for initial colonization [

79]; the urease system (ureA, ureB, ureE, ureH, ureI, nixA) maintains acid resistance and nitrogen metabolism homeostasis(Marais et al., 1999), in which the catalytic subunits (ureA, ureB) hydrolyze urea to produce ammonia and form a protective “ammonia cloud” [

80], the accessory genes (ureE, ureH, ureI) participate in nickel activation and enzyme maturation [

81], and nixA ensures nickel uptake [

82]; while flagellar genes (flgA, flgB) drive bacterial motility and gastric dissemination [

83].

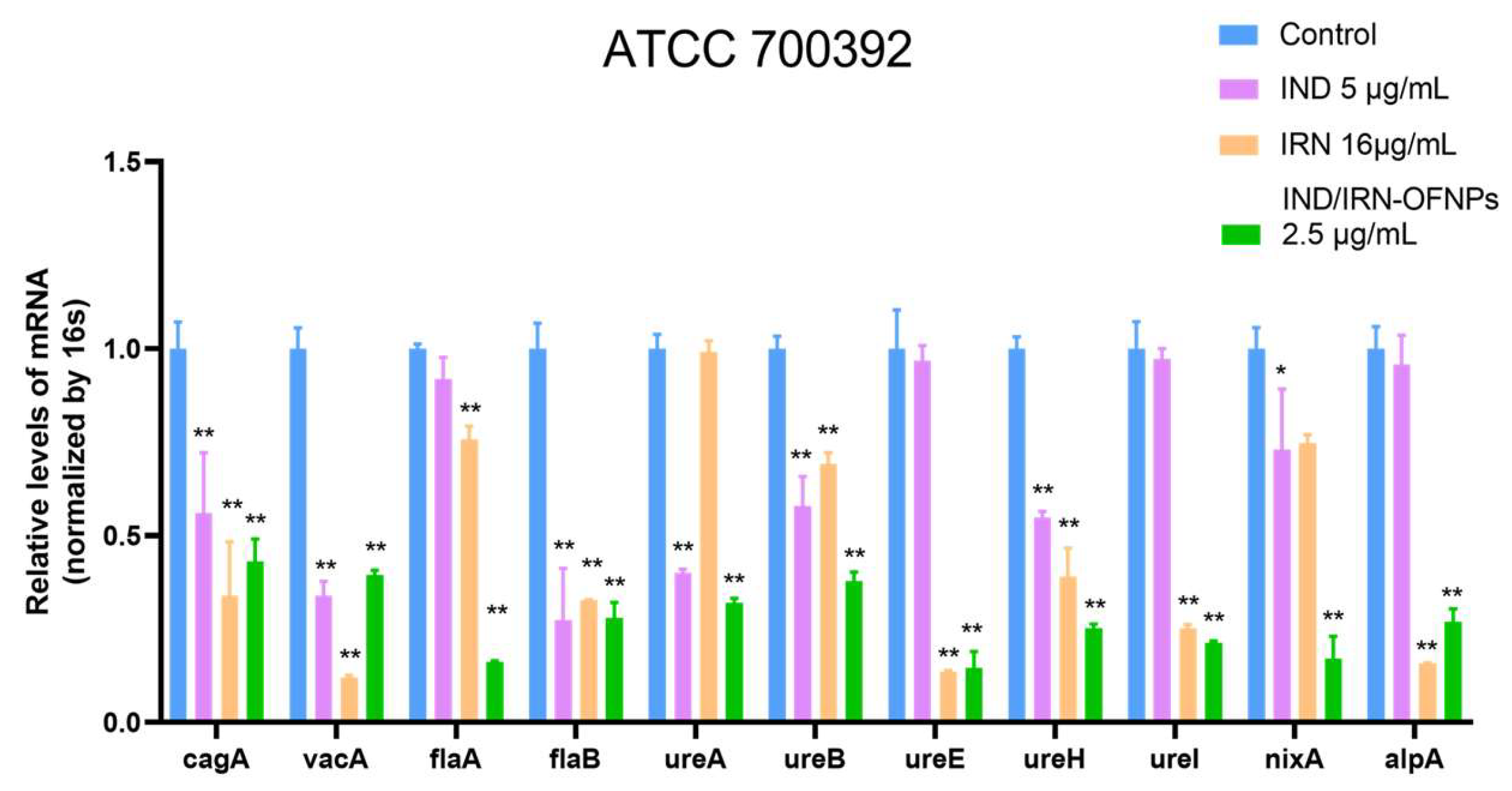

RT-qPCR results showed that under MIC conditions, IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs significantly downregulated urease gene transcription. The two single agents exerted differential effects on virulence factors, whereas the combination exhibited the strongest inhibition, indicating a synergistic effect. Urease activity assays further confirmed this: all three treatments effectively suppressed urease activity in both the standard strain (ATCC 700392) and the resistant strain (ATCC 43504), and IND/IRN-OFNPs maintained potent inhibition even at low concentrations. These findings suggest that IND and IRN attenuate Hp acid tolerance through dual mechanisms at both the transcriptional and enzymatic levels, thereby disrupting the infection process.

In addition, IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs markedly downregulated the transcription of flagellar genes (flaA, flaB) and the adhesion gene alpA, thereby impairing bacterial motility and colonization. Consistent with previous studies, these genes are closely associated with adhesion [

84], motility [

85], and inflammation [

86], and their suppression would directly weaken colonization capacity and alleviate host inflammatory responses [

87].

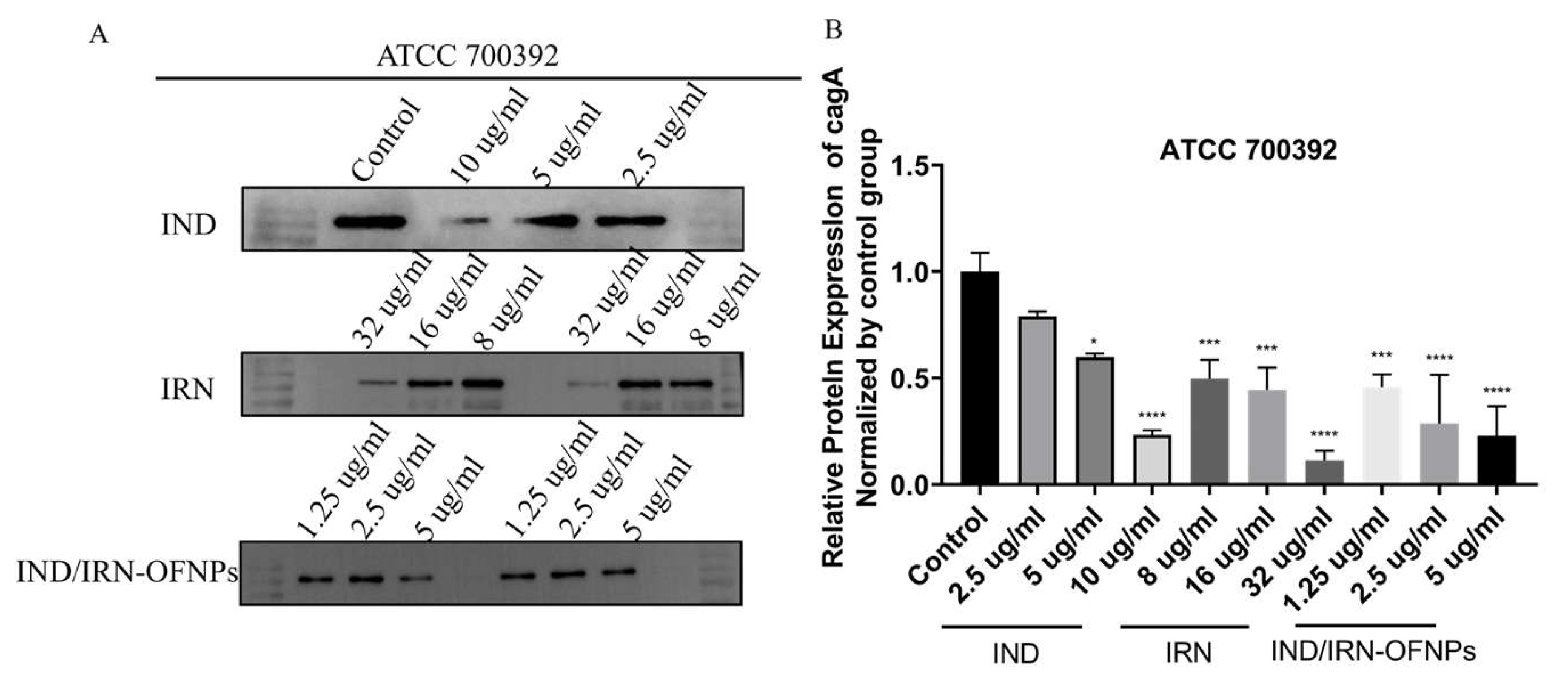

Notably, CagA and VacA are key virulence factors in persistent

Hp infection and gastric carcinogenesis [

88,

89], and network pharmacology identified them as critical regulatory nodes. RT-qPCR revealed that IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs significantly downregulated their transcription, which was further confirmed by Western blot. Among them, IND/IRN-OFNPs achieved over 50% inhibition of CagA expression at 1.25 µg/mL, showing the strongest effect. These findings suggest that IND and IRN may mitigate gastric mucosal inflammation and tissue damage, and potentially block the initiation and progression of

Hp–associated gastric cancer by interfering with CagA/VacA-mediated pathogenic signaling.

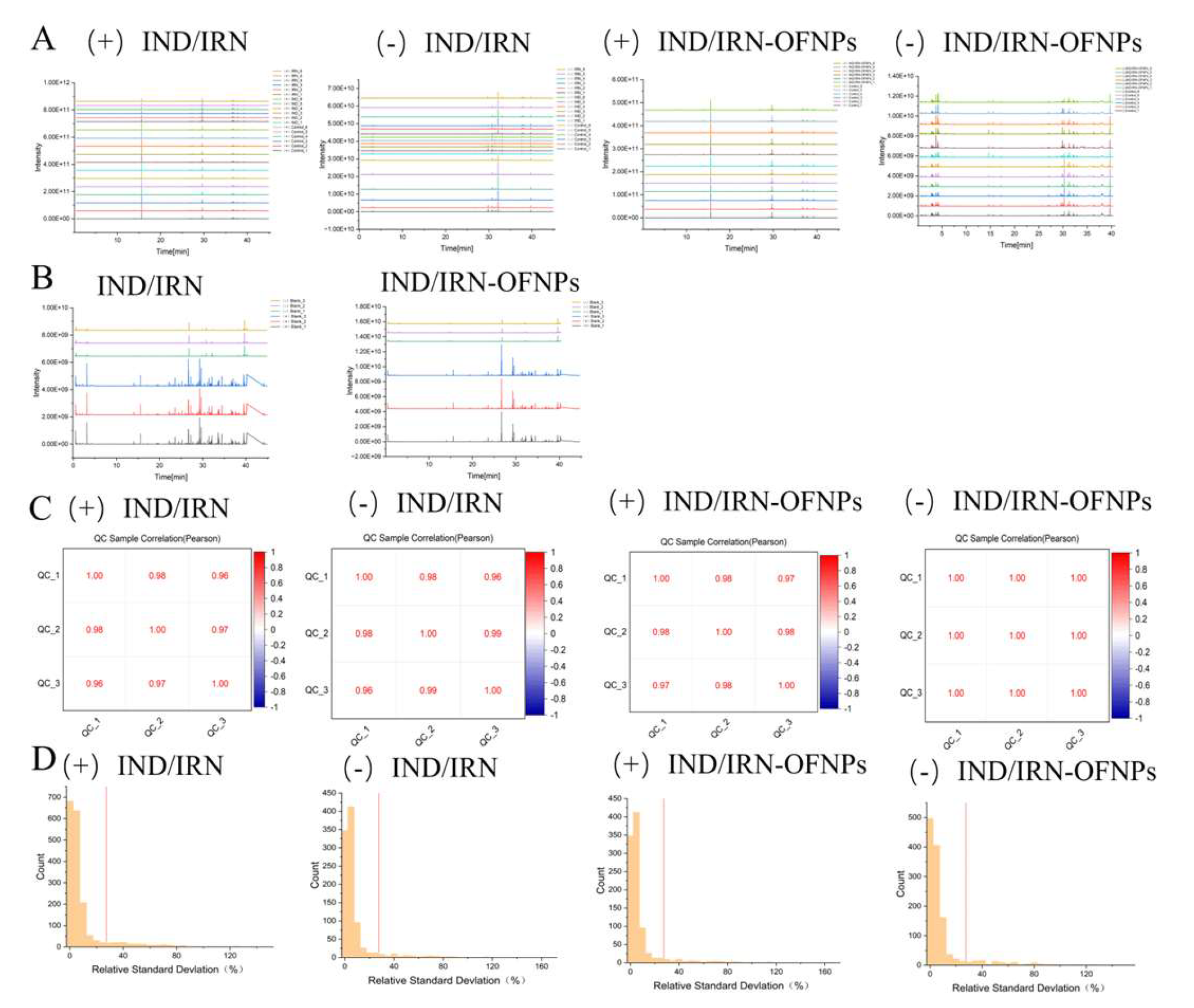

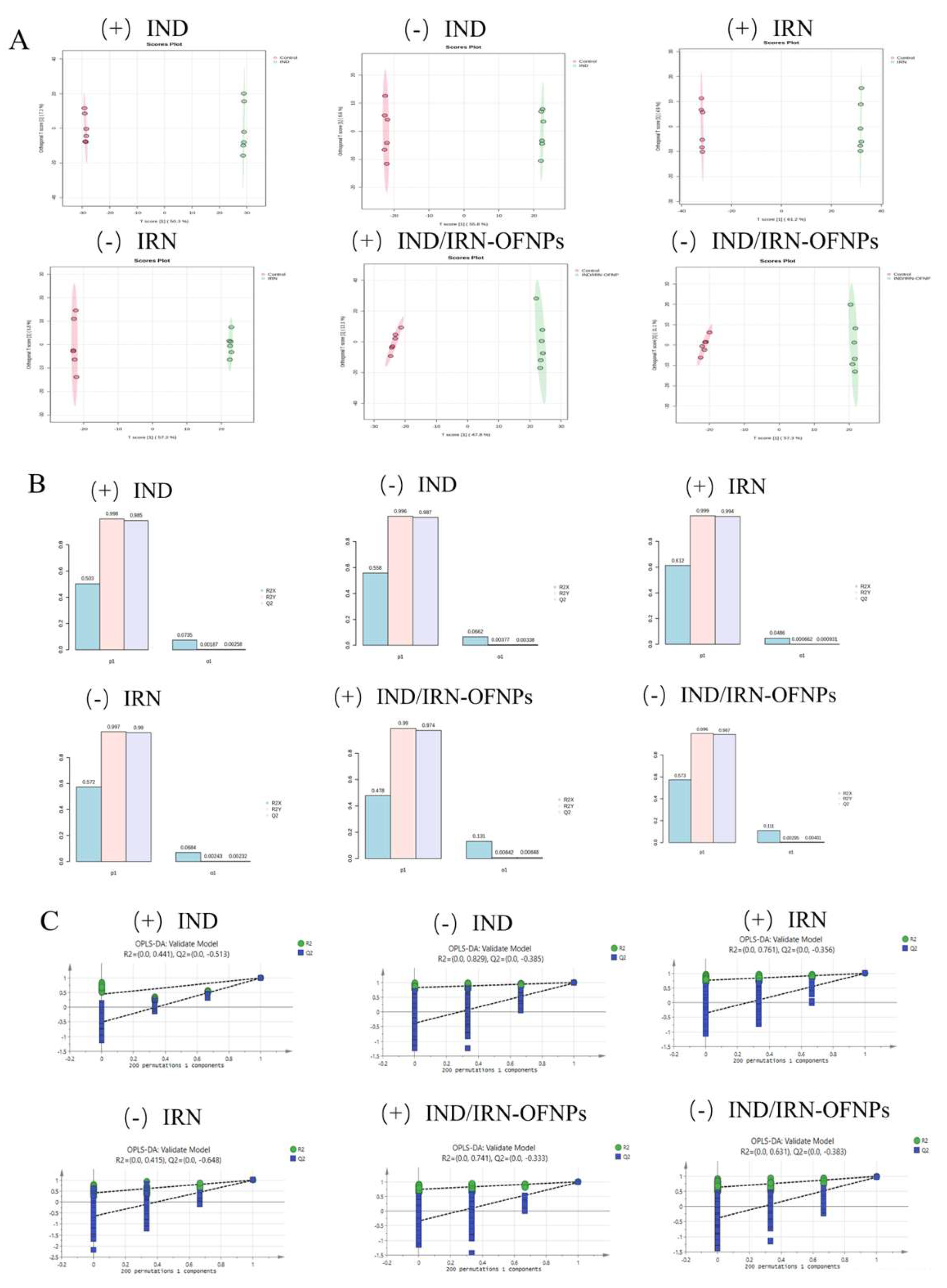

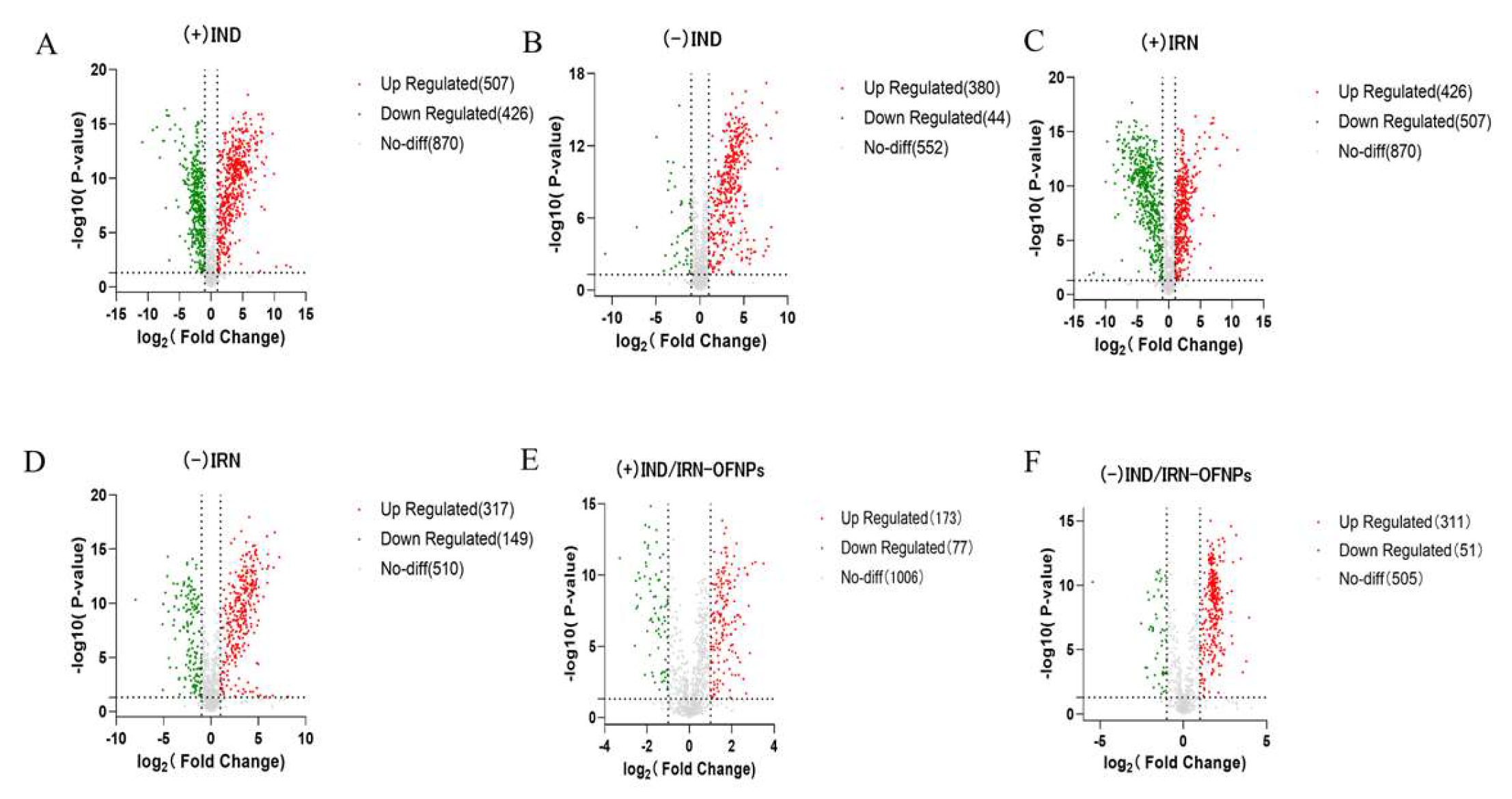

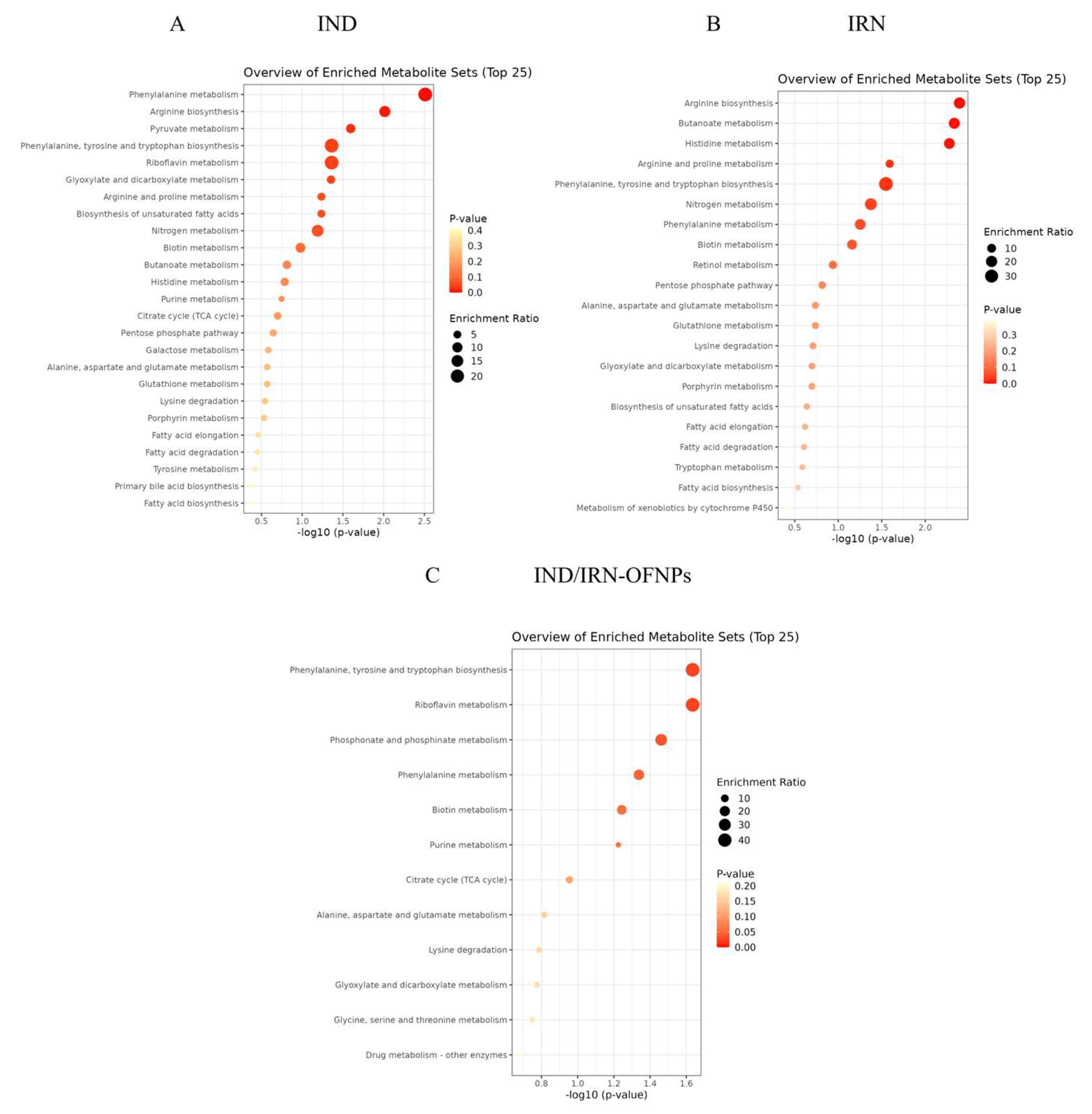

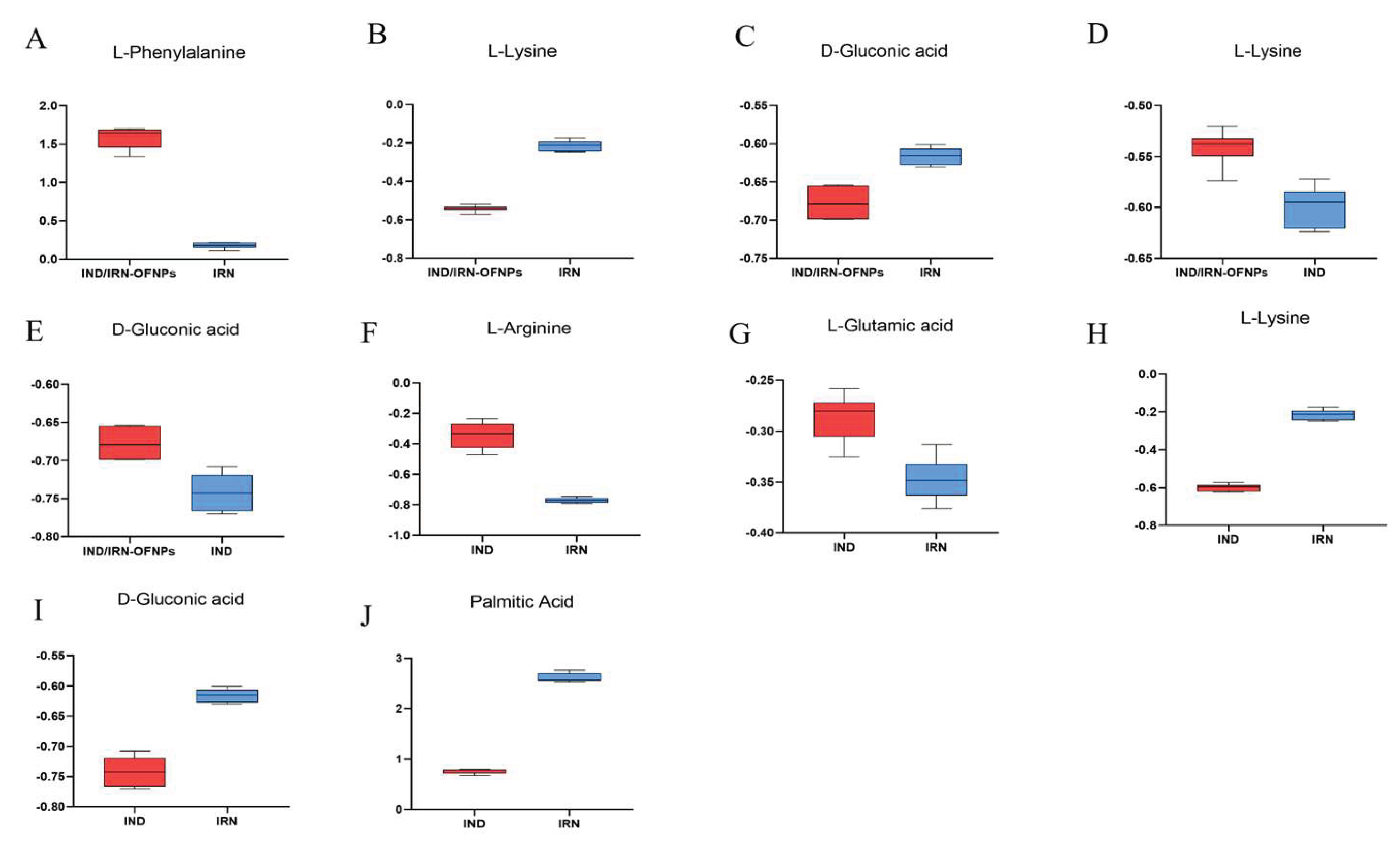

Using untargeted metabolomics, this study analyzed the significant metabolic profile alterations of Hp induced by IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs, preliminarily revealing their antibacterial metabolic regulation and differential mechanisms.

In the phenylalanine/tyrosine/tryptophan biosynthesis pathway, amino acids serve not only as key substrates for

Hp energy metabolism and nitrogen supply but also as essential molecules for protein synthesis, colonization, and virulence regulation [

90]. L-phenylalanine, an essential amino acid for

Hp, was significantly upregulated after IND and IND/IRN-OFNPs treatment. Since

Hp cannot synthesize phenylalanine and depends on exogenous uptake [

91], its accumulation suggests a blockade in downstream conversion, leading to impaired utilization of this essential amino acid, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis and bacterial growth. L-arginine, the central substrate of the arginine deiminase pathway, was downregulated after IRN treatment, suggesting impaired arginine metabolism [

92], which may reduce acid resistance and bacterial growth capacity.

In the arginine biosynthesis pathway, arginine functions not only as a substrate for protein synthesis but also participates in the urea cycle and the generation of signaling molecules (e.g., NO). Moreover, it can act as a urease activator, enabling bacteria to neutralize gastric acid. Its precursor, L-glutamic acid, is a crucial component of peptidoglycan in the bacterial cell wall, essential for cell wall integrity and acid resistance [

93]. After IND/IRN-OFNPs treatment, both L-glutamic acid and L-arginine were downregulated, indicating impaired acid resistance and cell wall biosynthesis, thereby weakening bacterial survival. In contrast, IND treatment upregulated both metabolites, which may reflect a stress-induced compensatory mechanism to sustain urease activity and energy metabolism.

Pyruvate metabolism represents a central hub for

Hp energy acquisition and carbon flux distribution. Pyruvate, as the end product of glycolysis, can be converted into malate, feeding into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, amino acid metabolism, and acid resistance regulation [

94]. Given that

Hp lacks a complete glycolytic pathway, its energy generation mainly depends on amino acid and organic acid metabolism to replenish pyruvate and its downstream products. Following IND treatment, DL-malic acid, a critical intermediate of the TCA cycle, was markedly downregulated, indicating TCA cycle blockade, energy deficiency, and consequent growth inhibition.

The glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism pathway, which interlinks fatty acid metabolism, acetyl-CoA, and other organic acids, plays a particularly important role under carbon-limited conditions [

95,

96], supporting

Hp survival in the nutrient-restricted gastric mucosa. IND treatment led to DL-malic acid downregulation, reflecting impaired carbon flux and failed energy compensation, thereby suppressing bacterial growth. This metabolic crisis and depletion of intermediates compromise

Hp survival, acid resistance, and pathogenicity, consistent with the observed growth arrest and bacteriostatic phenotype.

In the riboflavin metabolism pathway, flavin mononucleotide (FMN) functions as a vital cofactor in respiratory chain complexes I (NADH dehydrogenase) and II (succinate dehydrogenase) [

97], as well as in certain antioxidant enzymes [

98,

99]. IND treatment significantly reduced FMN levels, suggesting impaired electron transport and diminished reactive oxygen species scavenging, rendering

Hp more vulnerable to host oxidative stress and reducing its survival capacity.

In the butyrate ester metabolism pathway, butyrate can serve as an energy substrate, but its excessive accumulation may exert toxic effects [

100]. IRN treatment induced metabolic dysregulation and led to a significant increase in butyrate levels, indicating the accumulation of endogenous toxic metabolites and impairment of downstream energy metabolism, thereby reflecting the failure of compensatory energy mechanisms.

In the histidine metabolism pathway, histidine can be converted into histamine, contributing to acid–base regulation and signaling, facilitating

Hp survival in acidic environments. L-glutamic acid serves as an important substrate, while ethylamine is a downstream metabolite. IRN treatment downregulated L-glutamic acid, suggesting disrupted metabolic flux and reduced acid resistance, while ethylamine accumulation may cause local pH imbalance and react with nitrites to form carcinogenic nitrosamines [

101], synergistically damaging membrane structures and DNA, consistent with electron microscopy observations of bacterial lysis.

In the arginine/proline metabolism pathway, both amino acids are critical for energy generation, urease activity, and antioxidant defense [

102]. IRN treatment downregulated L-glutamic acid and L-arginine, indicating dual suppression of nitrogen and energy metabolism, consistent with the experimentally observed decrease in urease activity.

Nitrogen metabolism regulates amino acid synthesis, the urea cycle, and nitrogen utilization [

103], playing a central role in ammonia production, urease activity, and gastric acid neutralization in

Hp. IRN treatment downregulated L-glutamic acid, suggesting impaired nitrogen metabolism and restricted nitrogen utilization, further confirming disruption of bacterial nitrogen homeostasis.

In the phosphate metabolism pathway, phosphate is essential for energy synthesis, signal transduction, and nucleic acid metabolism [

104]. After IND/IRN-OFNPs treatment, phosphate levels increased, suggesting that the combined treatment interferes with phosphorylation processes and energy metabolism, thereby suppressing bacterial growth.

More importantly, metabolomics analysis revealed that although IND, IRN monotherapy, and IND/IRN-OFNPs groups shared certain metabolites, their abundances differed significantly, and pronounced metabolic heterogeneity was observed between the monotherapy groups. This indicates that the groups differ in their modes of metabolic pathway regulation and their capacities to modulate metabolites, reflecting variations in binding patterns, affinities, and metabolic characteristics with biological targets, thereby leading to mechanistic divergence.

IND carmine, a commonly used endoscopic contrast agent, enhances color contrast between lesions and normal tissue, thereby improving the detection rate of early Hp–associated lesions. This study demonstrates that IND itself possesses anti-Hp activity, while whether IND carmine, as its derivative, affects diagnostic accuracy or subsequent treatment requires further investigation. More importantly, IND and IRN are indole isomers, and their combined use significantly enhances antibacterial activity, providing a rationale for the development of Hp therapeutics and the rational design of synergistic agents based on shared indole scaffolds.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the preparation of IND/IRN-loaded OFNPs. (B) Photographs of OFNPs solutions after heating at 90 °C for 5 min and adjusting the pH to 4 at different concentrations. (C) FTIR spectra of free OVA, fucoidan, and OFNPs at concentrations of 0.75, 1, 1.25, and 1.5 µg/mL. (D) Particle size and PDI, and (E) zeta potential of OFNPs at different concentrations (0.75, 1, 1.25, and 1.5 µg/mL). (F-I) SEM images of OFNPs at concentrations of 0.75, 1, 1.25, and 1.5 µg/mL.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the preparation of IND/IRN-loaded OFNPs. (B) Photographs of OFNPs solutions after heating at 90 °C for 5 min and adjusting the pH to 4 at different concentrations. (C) FTIR spectra of free OVA, fucoidan, and OFNPs at concentrations of 0.75, 1, 1.25, and 1.5 µg/mL. (D) Particle size and PDI, and (E) zeta potential of OFNPs at different concentrations (0.75, 1, 1.25, and 1.5 µg/mL). (F-I) SEM images of OFNPs at concentrations of 0.75, 1, 1.25, and 1.5 µg/mL.

Figure 2.

(A-C) SEM images of IND/IRN-OFNPs with different drug loadings (40, 50, and 60 µg/mL). (D)Particle size and (E) zeta potential of free OFNPs and IND/IRN-OFNPs with different drug loadings. (F) Drug loading content and encapsulation efficiency of IND/IRN-OFNPs with different drug loadings.

Figure 2.

(A-C) SEM images of IND/IRN-OFNPs with different drug loadings (40, 50, and 60 µg/mL). (D)Particle size and (E) zeta potential of free OFNPs and IND/IRN-OFNPs with different drug loadings. (F) Drug loading content and encapsulation efficiency of IND/IRN-OFNPs with different drug loadings.

Figure 3.

(A) MIC and MBC values of IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs against different Hp strains. Standard strains: ATCC 700392 and ATCC 43504; clinical multidrug-resistant strains: SS1, QYZ-001, QYZ-003, QYZ-004, and CS01.

Figure 3.

(A) MIC and MBC values of IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs against different Hp strains. Standard strains: ATCC 700392 and ATCC 43504; clinical multidrug-resistant strains: SS1, QYZ-001, QYZ-003, QYZ-004, and CS01.

Figure 4.

Time–kill curves of IND (A), IRN (B), and IND/IRN-OFNPs (C) against ATCC 700392, and of IND (D), IRN (E), and IND/IRN-OFNPs (F) against ATCC 43504.

Figure 4.

Time–kill curves of IND (A), IRN (B), and IND/IRN-OFNPs (C) against ATCC 700392, and of IND (D), IRN (E), and IND/IRN-OFNPs (F) against ATCC 43504.

Figure 5.

MIC values of IND/IRN-OFNPs in combination with four antibiotics. NPs indicate IND/IRN-OFNPs; Abx indicate antibiotics.

Figure 5.

MIC values of IND/IRN-OFNPs in combination with four antibiotics. NPs indicate IND/IRN-OFNPs; Abx indicate antibiotics.

Figure 6.

SEM images showing the morphology of Hp ATCC 43504 after 12 h treatment at MIC concentrations: control group (A-C), IND group (D-F), IRN group (G-I), and IND/IRN-OFNPs group (J-L).

Figure 6.

SEM images showing the morphology of Hp ATCC 43504 after 12 h treatment at MIC concentrations: control group (A-C), IND group (D-F), IRN group (G-I), and IND/IRN-OFNPs group (J-L).

Figure 7.

Venn diagram of potential targets of IND and IRN.

Figure 7.

Venn diagram of potential targets of IND and IRN.

Figure 8.

Drug–Disease–Target Network.

Figure 8.

Drug–Disease–Target Network.

Figure 10.

(A) GO functional enrichment of core targets. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment of core targets.

Figure 10.

(A) GO functional enrichment of core targets. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment of core targets.

Figure 11.

Sankey diagram of core targets–BP/KEGG pathways, with 12 core targets on the left and the top 20 significantly enriched GO-BP and KEGG terms on the right.

Figure 11.

Sankey diagram of core targets–BP/KEGG pathways, with 12 core targets on the left and the top 20 significantly enriched GO-BP and KEGG terms on the right.

Figure 12.

(A) molecular docking models of IND with the top 5 core targets ranked by Degree. (B) molecular docking models of IRN with the top 5 core targets ranked by Degree.

Figure 12.

(A) molecular docking models of IND with the top 5 core targets ranked by Degree. (B) molecular docking models of IRN with the top 5 core targets ranked by Degree.

Figure 13.

Expression of multiple Hp virulence factors after 12 h treatment under MIC conditions with IND, IRN, or IND/IRN-OFNPs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the control.

Figure 13.

Expression of multiple Hp virulence factors after 12 h treatment under MIC conditions with IND, IRN, or IND/IRN-OFNPs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the control.

Figure 14.

(A, B) Effects of IND and IRN on urease activity of ATCC 700392. (C, D) Effects of IND/IRN-OFNPs on urease activity of ATCC 700392. (E, F) Effects of IND and IRN on urease activity of ATCC 43504. (G, H) Effects of IND/IRN-OFNPs on urease activity of ATCC 43504. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the control.

Figure 14.

(A, B) Effects of IND and IRN on urease activity of ATCC 700392. (C, D) Effects of IND/IRN-OFNPs on urease activity of ATCC 700392. (E, F) Effects of IND and IRN on urease activity of ATCC 43504. (G, H) Effects of IND/IRN-OFNPs on urease activity of ATCC 43504. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the control.

Figure 15.

(A) Representative Western blot images showing CagA protein expression in Hp treated with different concentrations (1/2× MIC, MIC, and 2× MIC) of IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs. (B) Quantitative analysis of CagA protein expression in Hp following treatment with different concentrations (1/2× MIC, MIC, and 2× MIC) of IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the control.

Figure 15.

(A) Representative Western blot images showing CagA protein expression in Hp treated with different concentrations (1/2× MIC, MIC, and 2× MIC) of IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs. (B) Quantitative analysis of CagA protein expression in Hp following treatment with different concentrations (1/2× MIC, MIC, and 2× MIC) of IND, IRN, and IND/IRN-OFNPs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the control.

Figure 16.

(A) TIC of IND/IRN and IND/IRN-OFNPs groups. (B) TIC of QC samples from IND/IRN and IND/IRN-OFNPs groups. (C) Pearson correlation heatmap of QC samples. (D) RSD distribution histogram of QC samples. Symbols “+” and “−” indicate positive and negative ion modes, respectively.

Figure 16.

(A) TIC of IND/IRN and IND/IRN-OFNPs groups. (B) TIC of QC samples from IND/IRN and IND/IRN-OFNPs groups. (C) Pearson correlation heatmap of QC samples. (D) RSD distribution histogram of QC samples. Symbols “+” and “−” indicate positive and negative ion modes, respectively.

Figure 18.

(A) OPLS-DA score plots for each group, with red representing the control group and green representing the treatment group; (B) OPLS-DA model validation plots for each group; (C) OPLS-DA permutation test results for each group. Symbols “+” and “−” indicate positive and negative ion modes, respectively.

Figure 18.

(A) OPLS-DA score plots for each group, with red representing the control group and green representing the treatment group; (B) OPLS-DA model validation plots for each group; (C) OPLS-DA permutation test results for each group. Symbols “+” and “−” indicate positive and negative ion modes, respectively.

Figure 19.

(A) Volcano plot of metabolites in the IND group under positive ion mode, and (B) under negative ion mode. (C) Volcano plot of metabolites in the IRN group under positive ion mode, and (D) under negative ion mode. (E) Volcano plot of metabolites in the IND/IRN-OFNPs group under positive ion mode, and (F) under negative ion mode.

Figure 19.

(A) Volcano plot of metabolites in the IND group under positive ion mode, and (B) under negative ion mode. (C) Volcano plot of metabolites in the IRN group under positive ion mode, and (D) under negative ion mode. (E) Volcano plot of metabolites in the IND/IRN-OFNPs group under positive ion mode, and (F) under negative ion mode.

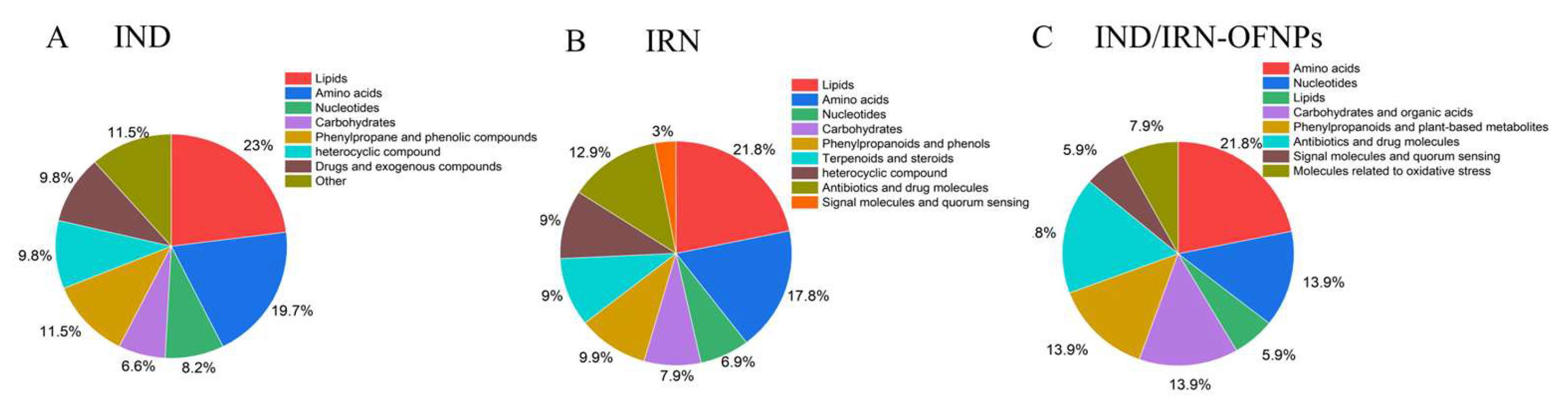

Figure 20.

Integrated classification of differential metabolites combining positive and negative ion modes. (A) A total of 155 metabolites were identified in the IND group. (B) 180 metabolites in the IRN group. (C) 101 metabolites in the IND/IRN-OFNPs group.

Figure 20.

Integrated classification of differential metabolites combining positive and negative ion modes. (A) A total of 155 metabolites were identified in the IND group. (B) 180 metabolites in the IRN group. (C) 101 metabolites in the IND/IRN-OFNPs group.

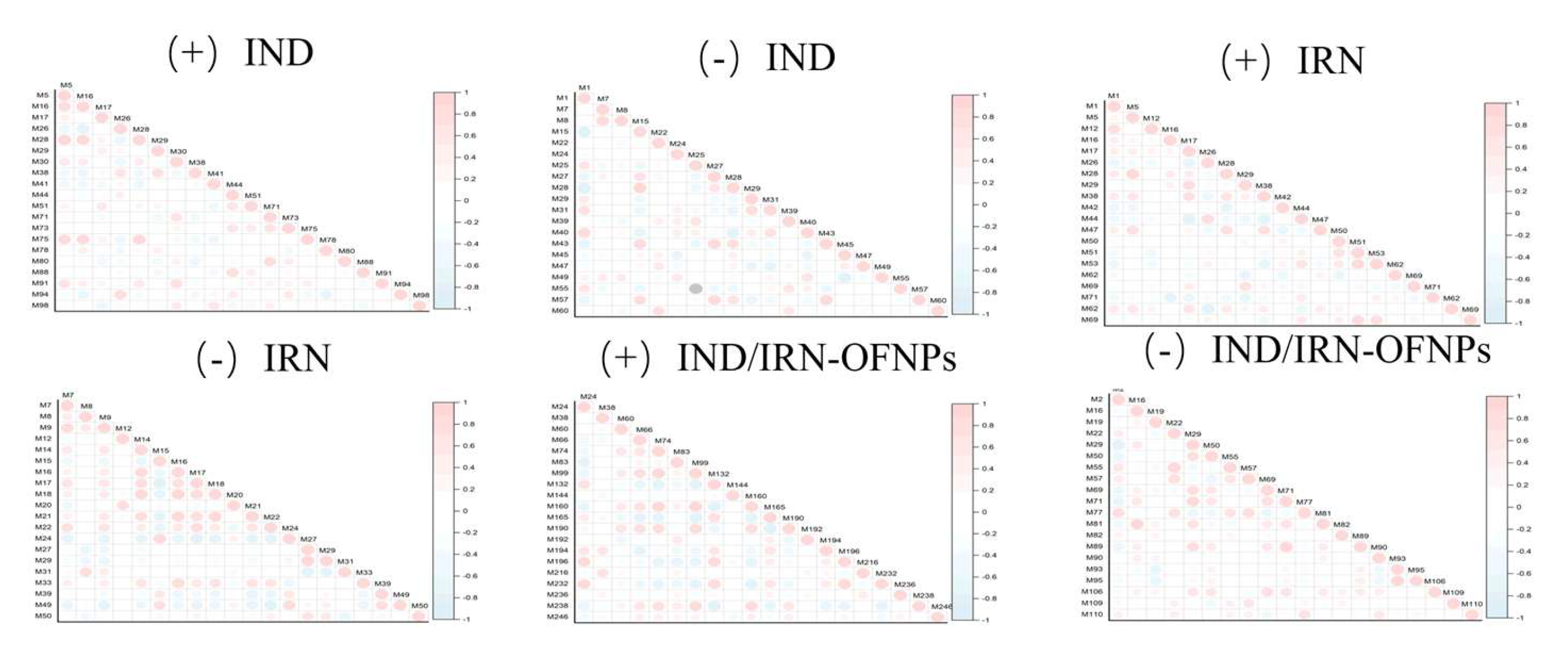

Figure 21.

Correlation analysis of the top 20 differential metabolites for each group, with red indicating positive correlation and blue indicating negative correlation. Symbols “+” and “−” indicate positive and negative ion modes, respectively.

Figure 21.

Correlation analysis of the top 20 differential metabolites for each group, with red indicating positive correlation and blue indicating negative correlation. Symbols “+” and “−” indicate positive and negative ion modes, respectively.

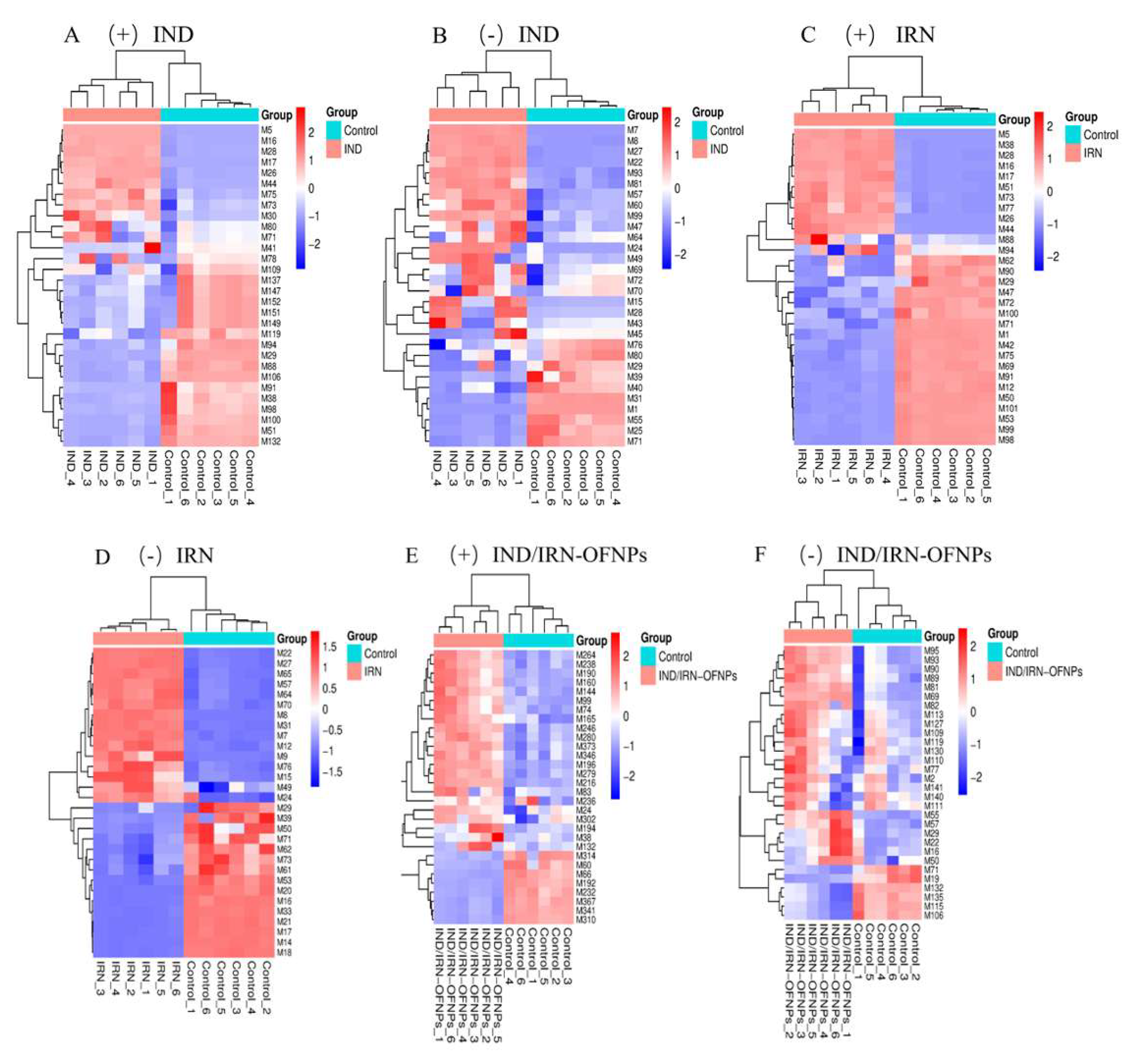

Figure 22.

Cluster analysis of the top 30 differential metabolites for each group. (A) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of differential metabolites in the IND group under positive ion mode, and (B) under negative ion mode. (C) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of differential metabolites in the IRN group under positive ion mode, and (D) under negative ion mode. (E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of differential metabolites in the IND/IRN-OFNPs group under positive ion mode, and (F) under negative ion mode.

Figure 22.

Cluster analysis of the top 30 differential metabolites for each group. (A) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of differential metabolites in the IND group under positive ion mode, and (B) under negative ion mode. (C) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of differential metabolites in the IRN group under positive ion mode, and (D) under negative ion mode. (E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of differential metabolites in the IND/IRN-OFNPs group under positive ion mode, and (F) under negative ion mode.

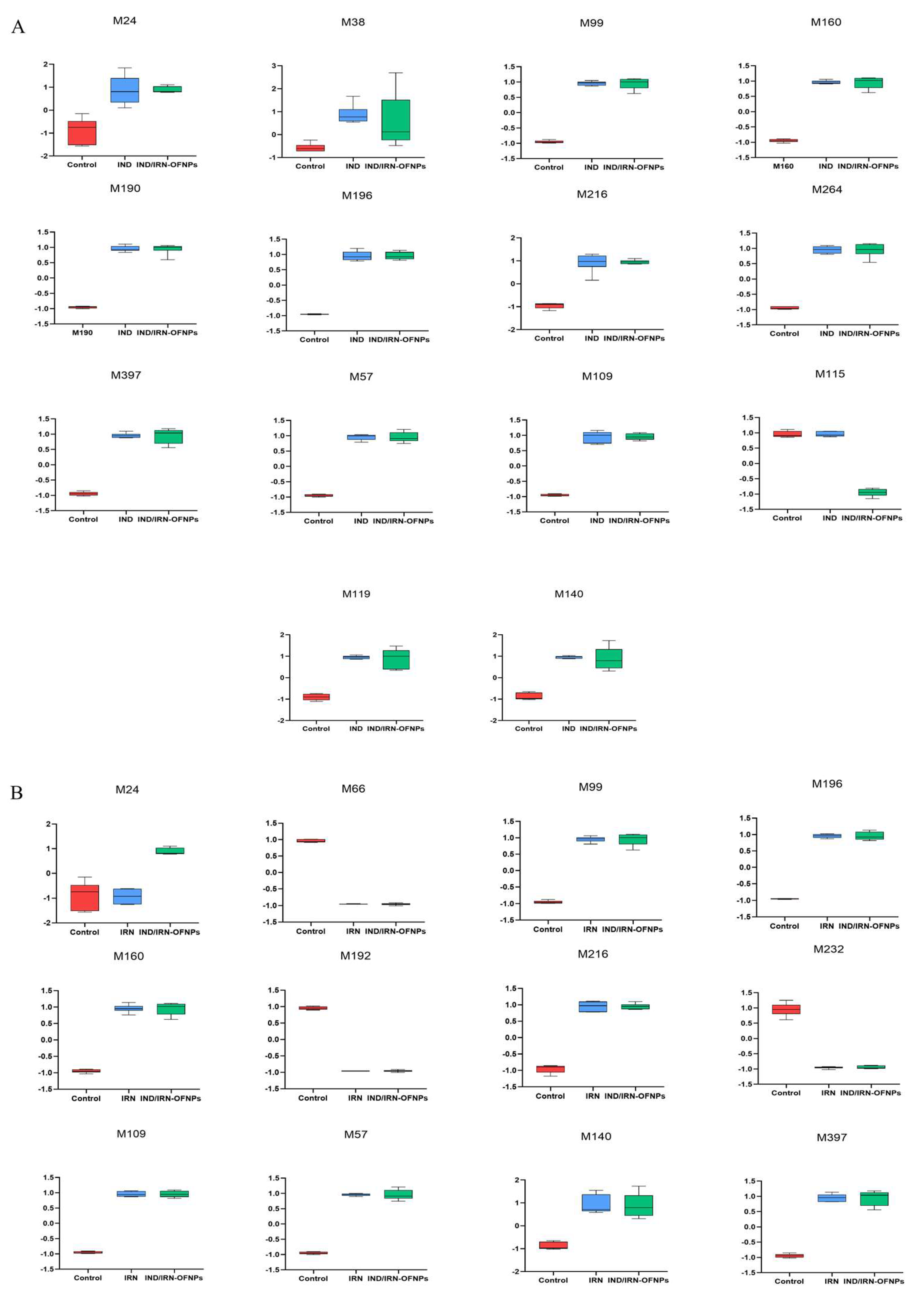

Figure 23.

(A) Boxplots showing expression differences of 14 shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs and IND groups. (B) Boxplots showing expression differences of 12 shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs.

Figure 23.

(A) Boxplots showing expression differences of 14 shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs and IND groups. (B) Boxplots showing expression differences of 12 shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs.

Figure 24.

KEGG pathway enrichment bubble plot of differential metabolites in IND(A), IRN(B), and IND/IRN-OFNPs groups(C).

Figure 24.

KEGG pathway enrichment bubble plot of differential metabolites in IND(A), IRN(B), and IND/IRN-OFNPs groups(C).

Figure 25.

(A-C) Boxplots of expression differences of shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs and IRN groups within KEGG pathways. (D, E) Boxplots of expression differences of shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs and IND groups within KEGG pathways. (F-J) Boxplots of expression differences of shared metabolites between IND and IRN groups within KEGG pathways.

Figure 25.

(A-C) Boxplots of expression differences of shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs and IRN groups within KEGG pathways. (D, E) Boxplots of expression differences of shared metabolites between IND/IRN-OFNPs and IND groups within KEGG pathways. (F-J) Boxplots of expression differences of shared metabolites between IND and IRN groups within KEGG pathways.

Table 1.

RT-qPCR Primer sequences.

Table 1.

RT-qPCR Primer sequences.

| Gene name |

Sequences forward (F) |

Sequences reverse (R) |

| 16S rRNA |

CCGCCTACGCGCTCTTTAC |

CTAACGAATAAGCACCGGCTAAC |

| cagA |

ATAATGCTAAATTAGACAACTTGAGCGA |

TTAGAATAATCAACAAACATCACGCCAT |

| vacA |

CTGGAGCCGGGAGGAAAG |

GGCGCCATCATAAAGAGAAATTT |

| flgA |

ATTGGCGTGTTAGCAGAAGTGA |

TGACTGGACCGCCACATC |

| flgB |

ACATCATTGTGAGCGGTGTGA |

GCCCCTAACCGCTCTCAAAT |

| ureA |

ACCGGTTCAAATCGGCTCAC |

CAAACCTTACCGCTGTCCCG |

| ureB |

GGAATGGTTTGAAACGAGGA |

CCGCTTCCACTAACCCCACTA |

| ureE |

TCTTGGCTTGGATGTGAATG |

GGAATGGTTTGAAACGAGGA |

| ureH |

AGATCCCAAAACCACCGACTT |

ACGGCTCCATCCACTCCTT |

| ureI |

CCCCTGTAGAAGGTGCTGAA |

GCCGCATACAAGTAGGTGAAAC |

| nixA |

CATATGATCATAGAGCGTTTAATG |

CTCGAGTTTCATGACCACTTTAAA |

| alpA |

GCACGATCGGTAGCCAGACT |

ACACATTCCCCGCATTCAAG |

Table 2.

Chromatographic Gradient Elution Conditions.

Table 2.

Chromatographic Gradient Elution Conditions.

| Time/min |

0~1.5 |

1.5~3 |

3~10 |

| Moving phase |

98%A+2%B |

100%B |

100%B |

Table 3.

MIC and MBC results of different drug treatments against different Hp strains. S: Sensitive to the drug, R: Resistant to the drug, MTZ: Metronidazole, LEF: Levofloxacin, AMO: Amoxicillin, CLA: Clarithromycin.

Table 3.

MIC and MBC results of different drug treatments against different Hp strains. S: Sensitive to the drug, R: Resistant to the drug, MTZ: Metronidazole, LEF: Levofloxacin, AMO: Amoxicillin, CLA: Clarithromycin.

|

Hp strains |

Drug sensitivity |

MIC(µg/mL) |

MBC(µg/mL) |

| IND |

IRN |

OFNPs |

IND/IRN-OFNPs |

IND |

IRN |

IND/IRN-OFNPs |

| ATCC 700392 |

S |

5 |

16 |

>375 |

2.5 |

10 |

32 |

5 |

| ATCC 43504 |

R(MTZ) |

2.5 |

10 |

>375 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

10 |

| SS1 |

S |

4 |

10 |

>375 |

2.5 |

8 |

20 |

5 |

| QYZ-001 |

R(MTZ) |

5 |

5 |

>375 |

2.5 |

10 |

20 |

5 |

| QYZ-003 |

R(MTZ,CLA,LEF) |

2 |

20 |

>375 |

2 |

8 |

40 |

8 |

| QYZ-004 |

R(MTZCLA,LEF,AMO) |

2.5 |

10 |

>375 |

2 |

10 |

40 |

4 |

| CS01 |

R(CLA) |

5 |

32 |

>375 |

4 |

10 |

64 |

8 |

Table 4.

Results from the checkerboard dilution method, showing MIC and FICI values for the physical mixture of IND and IRN against Hp.

Table 4.

Results from the checkerboard dilution method, showing MIC and FICI values for the physical mixture of IND and IRN against Hp.

|

Hp strains |

MIC (µg/mL) |

FICI |

Interaction |

| IND |

IRN |

IND+IRN |

| ATCC 700392 |

5 |

16 |

1.25+2 |

0.375 |

synergy |

| ATCC 43504 |

2.5 |

10 |

0.3125+5 |

0.625 |

additive |

| SS1 |

4 |

10 |

0.5+5 |

0.625 |

additive |

Table 5.

Results from the checkerboard dilution method, showing MIC and FICI values for IND/IRN-OFNPs alone or in combination with four antibiotics.

Table 5.

Results from the checkerboard dilution method, showing MIC and FICI values for IND/IRN-OFNPs alone or in combination with four antibiotics.

|

Hp Strains |

Antibiotics |

MIC (µg/mL) |

FICI |

Interaction |

| IND/IRN-OFNPs |

antibiotics |

IND/IRN-OFNPs+ antibiotics |

| ATCC 700392 |

MET |

2.5 |

1.6 |

0.3125+0.4 |

0.375 |

synergy |

| AMO |

2.5 |

0.1 |

0.3125+0.25 |

0.375 |

synergy |

| LEF |

2.5 |

0.8 |

0.3125+0.1 |

0.25 |

synergy |

| CLA |

2.5 |

0.004 |

0.3125+0.008 |

0.625 |

additive |

| ATCC 43504 |

MET |

5 |

6.4 |

2.5+0.8 |

0.625 |

additive |

| AMO |

5 |

0.4 |

1.25+0.005 |

0.2625 |

synergy |

| LEF |

5 |

1.6 |

0.625+0.2 |

0.25 |

synergy |

| CLA |

5 |

0.016 |

2.5+0.002 |

0.625 |

additive |

| SS1 |

MET |

2.5 |

1.6 |

0.3125+0.2 |

0.25 |

synergy |

| AMO |

2.5 |

0.4 |

2.5+0.005 |

1.125 |

additive |

| LEF |

2.5 |

1.6 |

0.3125+0.4 |

0.375 |

synergy |

| CLA |

2.5 |

0.016 |

0.3125+0.008 |

0.625 |

additive |

Table 6.

Core target proteins for IND and IRN in anti-Hp infection.

Table 6.

Core target proteins for IND and IRN in anti-Hp infection.

| Uniprot ID |

Gene |

Protein |

Degree value |

| P42574 |

CASP3 |

Caspase-3 |

35 |

| P07900 |

HSP90AA1 |

Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha |

33 |

| P14780 |

MMP9 |

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

29 |

| P09874 |

PARP1 |

Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 |

27 |

| P42336 |

PIK3CA |

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha isoform |

24 |

| O60674 |

JAK2 |

Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2 |

23 |

| P24941 |

CDK2 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 |

22 |

| P35354 |

PTGS2 |

Prostaglandin G/H synthase |

21 |

| P45983 |

MAPK8 |

Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 |

21 |

| P00519 |

ABL1 |

Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 |

20 |

| P08253 |

MMP2 |

72 kDa type IV collagenase |

19 |

| P06493 |

CDK1 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 |

18 |

Table 7.

Molecular docking information for IND, IRN, and core targets.

Table 7.

Molecular docking information for IND, IRN, and core targets.

| No. |

Gene ID |

Protein ID |

Binding energy

(kcal/mol) |

| IND |

IRN |

| 1 |

CASP3 |

1GFW |

-5.80 |

-6.05 |

| 2 |

HSP90AA1 |

5J80 |

-6.30 |

-6.17 |

| 3 |

MMP9 |

6ESM |

-6.99 |

-6.56 |

| 4 |

PARP1 |

1UK1 |

-6.00 |

-7.46 |

| 5 |

PIK3CA |

4JPS |

-5.57 |

-5.66 |