Introduction

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) is a herniation of abdominal contents through a diaphragmatic defect into the thoracic cavity. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is relatively common in the neonatal period. Depending on the study population, an estimated incidence is 1.7 to 5.7 per 10,000 live births (Kotecha 2012). It presents most frequently with respiratory distress in infancy (O’Neill 2002). CDH diagnosed after the age of one month is a late-presenting CDH (Kim 2013). The reported incidence of late-presenting CDH is 5 to 25% of all cases of CDH (Raucci 2025). The late-presenting CDH presents with a variety of complaints, leading to diagnostic dilemmas and delays in management. Diagnostic difficulty is faced often left-sided late CDH in 78.4% as compared to right sided hernia in 21.2% (Bagłaj 2004). A wide spectrum of clinical presentation is seen in late presenting CDH. Common symptoms were respiratory distress and vomiting (Bagłaj 2005). Some gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and regurgitation of feeding are common in late presenting CDH associated with respiratory distress. It may give a high index of suspicion towards late CDH (Gebremichael 2024). Reported cases were confused with pneumothorax or pneumonia and had chest tube placement (Coren 1997).

The patient discussed here presented as pneumonia with chest radiographic findings consistent with left pneumothorax that subsequently proved to be a diaphragmatic hernia. It is a rare condition with an atypical presentation. The experience of the case may help to manage future cases of similar conditions.

Case Presentation

A previously healthy, well-nourished, 7-month-old child, who had had an uneventful neonatal period, presented to the emergency department with complaints of fever, difficult breathing, and poor feeding. On review of symptoms, she had a four-day history of a slight cough with occasional vomiting. She was treated for pneumonia with cefaclor and paracetamol for two days; otherwise, medical history was noncontributory. She had no known exposures and no recent trauma. Her immunization status was up to date.

On physical exam, her respiratory rate was 76 per minute with oxygen saturations of 76% on room air. Signs of respiratory distress were present. Her heart rate was 190 per minute with a temperature of 37.3°C in the axilla. She had diminished breath sounds in the left lower zone with coarse crackles on the left upper zone. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender with normal bowel sounds.

The white blood cell count was 16,000 mm

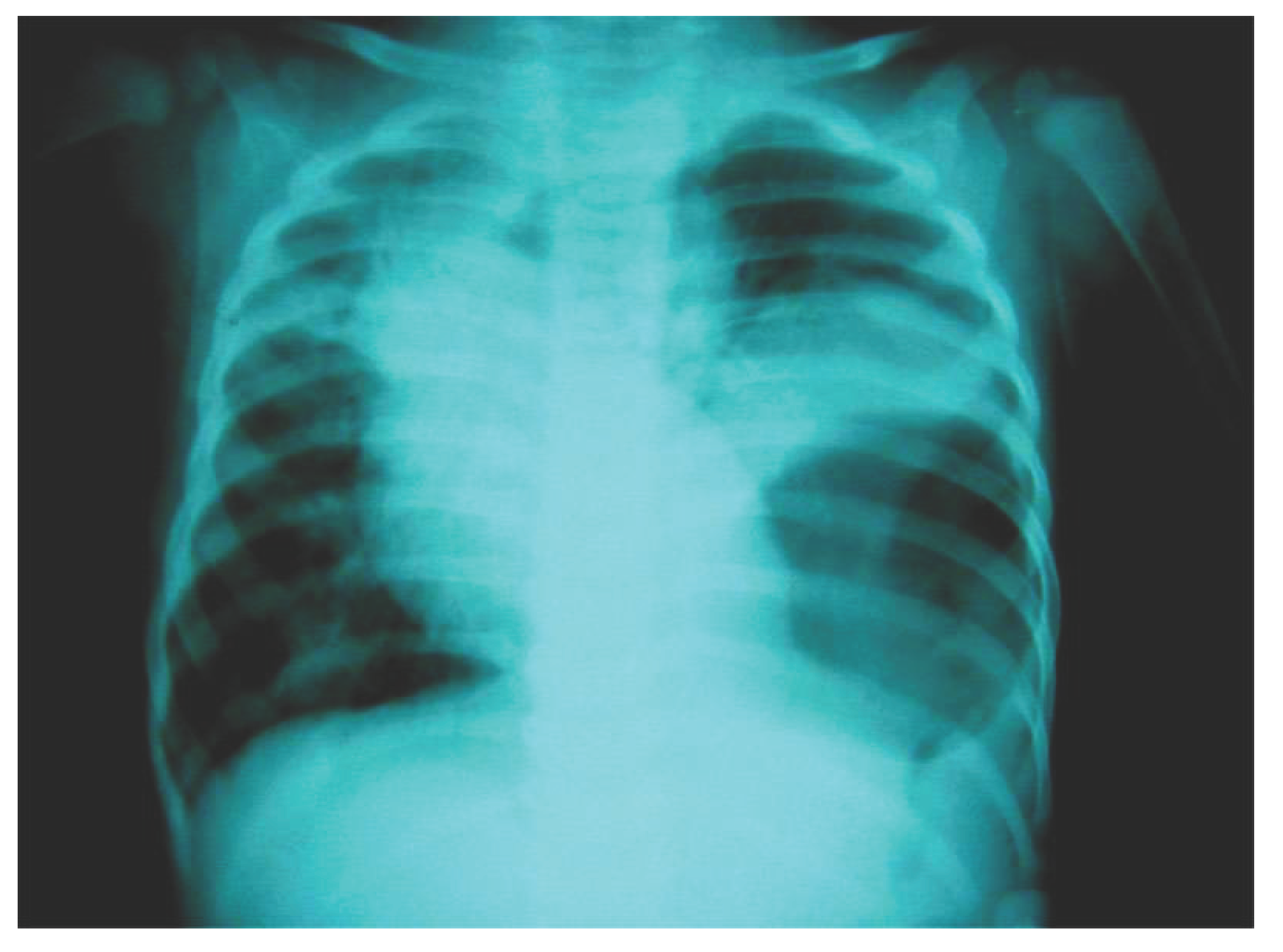

3 with a differential of 84% neutrophils, 12% lymphocytes, and 4% monocytes. The patient was admitted, and oxygen was given to maintain saturation. Intravenous ampicillin was started for presumed pneumonia. She continued to have intermittent vomiting and fever. An X-ray of the chest was done and interpreted as a large left pneumothorax leading to mediastinal shift with left upper lobe consolidation (

Figure 1).

Chest tube insertion was planned. Because of a clear, localized air inferiorly with an indistinct left diaphragm, a strong suspicion of diaphragmatic hernia was made, and a chest tube insertion was not attempted.

A nasogastric tube was placed, and an abdominal x-ray was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. A subsequent radiograph revealed the nasogastric tube advancing into the left thoracic cavity (

Figure 2).

The nasogastric tube decompression was continued. Surgery was delayed, waiting for full recovery from pneumonia. At surgery, a small Bochdalek hernia defect was found containing the stomach and a portion of the splenic flexure of the colon. After reduction of the hernia contents, the posterolateral defect was primarily closed with a patch (

Figure 3).

The patient did well postoperatively with resolution of her symptoms and was discharged from the hospital after six days. Follow up after 30 days of surgery revealed marked clinical and radiological improvement.

Discussion

The late presenting diaphragmatic hernia presents with a variety of complaints leading to diagnostic difficulty and delay in treatment. A child with this defect presents frequently with respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms or symptoms involving both simultaneously. Sudden onset of symptoms are observed in the children aged less than 12 months, in older children the clinical symptoms are of a chronic manifestation (Bagłaj 2005). Patients may have diverse complaints including acute gastrointestinal symptoms such as recurrent abdominal pain, vomiting, anorexia, and constipation; pulmonary symptoms including cough, dyspnea, and respiratory distress; or nonspecific complaints such as failure to thrive and fever ((Wooldridge 2003). Plain chest films often show the presence of bowel in the thorax, leading to the diagnosis. However, plain films have been misinterpreted as pneumatoceles, tension pneumothorax, pleural effusion, congenital lung cysts, and gastric volvulus ((Wooldridge 2003). Misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatment and significant morbidity ((Mei-Zahav 2003) There are reports on delayed onset diaphragmatic hernia confused with pneumothorax and few cases misdiagnosed as pneumonia (O’Neill 2002)(Mei-Zahav 2003)(Siegel 1981). All of these children had respiratory symptoms ranging from mild respiratory symptoms to respiratory distress. In our patient, respiratory distress and fever were the prominent features.

Coren ME et al(Coren 1997) reported two cases of diaphragmatic hernia initially diagnosed as tension pneumothorax later turned out diaphragmatic hernia and chest tube placement was carried out on patients. In our patient chest tube placement was prevented due to strong suspicion of delayed onset diaphragmatic hernia seeing indistinct left diaphragm. Our patient was diagnosed with the plain chest film with gastric tube placement because the herniated content was stomach. If the herniated content were other than stomach, patient would have gone through different interventions with diagnostic delay. Ng et al ((Ng 2004) reported similar case misdiagnosed as pneumonia clinically and radiologically later ultrasonography raised the suspicion of diaphragmatic hernia. In our case ultrasonography of chest was not needed because plain chest film after swallowing of nasogastric tube showed the diaphragmatic hernia. Again Kaur and singh ((Kaur 2003) reported an infant diagnosed to have diaphragmatic hernia masquerading as staphylococcal pneumonia. Our patient is very similar to these patients. Both of the cases were confused with pneumonia as in our patient. Our patient was again misdiagnosed as pneumothorax and planned for chest tube insertion. The recognition of the clinical symptoms of the patient and awareness of the late presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia may have led to earlier radiographic workup and early diagnosis of the hernia.Plain radiograph with a swallowed nasogastric tube advancing into the thoracic cavity is an important investigation to diagnose diaphragmatic hernia (Cigdem 2007). In diaphragmatic hernias simulating pleural effusion, this maneuver does not provide the diagnosis because the herniating structure would be other than the stomach and will have a normal nasogastric tube placement. In our patient with a herniated stomach, radiographic findings suggested a pneumothorax. The presence of a flat or scaphoid abdomen as a clinical clue in the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia was absent due to pneumonia. However, a gastrointestinal contrast study with ultrasound has good diagnostic value in difficult cases. Wooldridge et al (Wooldridge 2003) recommended a chest radiograph with ultrasound and computed tomography of the chest in children with clinical symptoms atypical for pneumonia in unusual patient presentations for the definitive diagnosis of either a hernia or other chest masses. Siegel et al (Siegel 1981) showed that ultrasound was useful in establishing the diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Another diagnostic imaging choice available is a gastrointestinal contrast study, but it would not have worked well in our patient because she was seriously ill with grunting, vomiting, and was in respiratory distress. Since late presentation of congenital hernia has a high survival rate after surgery, early and accurate diagnosis decreases morbidity and mortality.

In an emergency, respiratory distress due to gastrothorax, decompression with placement of a gastric tube should be done first (Gebremichael 2024). In this case, intermittent vomiting and respiratory distress improved after gastric tube decompression.

Conclusion

In children with sudden onset of clinical symptoms such as pneumonia with respiratory distress and pneumothorax, late presenting diaphragmatic hernia should be suspected. We recommend a chest radiograph with a swallowed nasogastric tube and further imaging with ultrasound or computed tomography in atypical patient presentations. Late presentation of diaphragmatic hernia, although uncommon, needs to be considered in a child with respiratory distress and in unusual patient presentations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Marc Downing, MD, for performing surgery on this patient in United Mission Hospital, Tansen Palpa, Nepal.

References

- S Kotecha, A Barbato, A Bush, F Claus, M Davenport, C Delacourt, J Deprest, E Eber, B Frenckner, A Greenough, AG Nicholson, JL Antón-Pacheco, F Midulla. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia.. Eur Respir J 39, 820-9 (2012).

- CP O’Neill, R Mabrouk, WA McCallion. Late presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia.. Arch Dis Child 86, 395 (2002).

- DJ Kim, JH Chung. Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in children: the experience of single institution in Korea.. Yonsei Med J 54, 1143-8 (2013). [CrossRef]

- U Raucci, A Boni, S Foligno, L Valfrè, P Bagolan, PS Schingo, Vecchia N Della, A Reale, A Villani, A Musolino. Late congenital diaphragmatic hernia: is a significant challenge?. Minerva Pediatr (Torino) 77, 205-212 (2025). [CrossRef]

- M Bagłaj. Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in children: a clinical spectrum.. Pediatr Surg Int 20, 658-69 (2004). [CrossRef]

- M Bagłaj, U Dorobisz. Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in children: a literature review.. Pediatr Radiol 35, 478-88 (2005). [CrossRef]

- A Gebremichael, W Tesfaye. Clinical challenges and management of late presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia mimicking tension pneumothorax in a child: a case report and review of literatures.. Int J Emerg Med 17, 134 (2024). [CrossRef]

- ME Coren, M Rosenthal, A Bush. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia misdiagnosed as tension pneumothorax.. Pediatr Pulmonol 24, 119-21 (1997).

- JL Wooldridge, DA Partrick, DD Bensard, RR Deterding. Diaphragmatic hernia simulating a left pleural effusion.. Pediatrics 112, e487 (2003). [CrossRef]

- M Mei-Zahav, M Solomon, D Trachsel, JC Langer. Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia: not only a neonatal disease.. Arch Dis Child 88, 532-5 (2003). [CrossRef]

- MJ Siegel, GD Shackelford, WH McAlister. Left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia: delayed presentation.. AJR Am J Roentgenol 137, 43-6 (1981). [CrossRef]

- CP Ng, CB Lo, CH Chung. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia masquerading as pneumonia.. Emerg Med Australas 16, 167-9 (2004). [CrossRef]

- G Kaur, T Singh. Right-sided diaphragmatic hernia masquerading as staphylococcal pneumonia.. Indian J Pediatr 70, 743-5 (2003). [CrossRef]

- MK Cigdem, A Onen, S Otcu, H Okur. Late presentation of bochdalek-type congenital diaphragmatic hernia in children: a 23-year experience at a single center.. Surg Today 37, 642-5 (2007). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).