1. Introduction

Tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) is a relatively frequent clinical condition in pediatric patients. Despite this, the diagnostic criteria and treatment of this pathology are still highly debated and not standardized, so they can vary greatly from pediatric center to pediatric center. Furthermore, clear international guidelines that can be applied to pediatric patients with this pathology are missing, especially regarding the selection criteria of patients deserving of surgical therapy, and which therapy: anterior aorthopexy or posterior tracheopexy. Even the 2019 ERS statement on tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children deals with these surgical procedures in a very brief manner, and does not outline clear clinical and diagnostic criteria for selecting patients to be treated surgically.

We therefore felt the need for a comparison between the various Italian pediatric centers that treat this pathology, inviting specialists who have recognized experience in their field to a day of discussion: pulmonologists, endoscopists, pediatric surgeons, otolaryngologists. This work of ours derives precisely from all the interventions and consequent discussions that were held on 8 June 2024 at the IRCCS G. Gaslini Children Hospital (Genova, Italy), with the intention of covering all aspects that may be of interest to doctors dealing with this pathology.

This work is divided into various sections, starting from the clinical presentation of the patient which must lead to suspicion of the presence of tracheomalacia. This is followed by the section of diagnostic tests: radiographic, spirometric and endoscopic, giving particular importance to the need for bronchoscopy to be dynamic, i.e. to be performed with a phase in which the patient also performs abdominal staining, to verify how the tracheal lumen changes with the increase in intrathoracic pressure. Once the diagnosis of TBM has been made, and the individual patient has been discussed within a multidisciplinary team, the surgical treatments most suitable for every single patient are exposed (anterior aortopexy or posterior tracheopexy). A section dedicated to the most severe cases of malacia follows: TM associated with esophageal atresia, which sometimes must be treated with both anterior aortopexy and posterior tracheopexy. The section concerning the follow-up of patients with TM is next, which underlines the need to have a multidisciplinary team available, to verify not only the success of the surgical treatment (if carried out), but also to treat the various pathologies that are often associated with TM in these patients. The final section of the paper instead deals with the respiratory assistance of the patient with TM, both as a bridging therapy while waiting for surgery, and when this is not feasible. We therefore talk about the indications for the positioning of stents and tracheal splits, tracheostomy and its removal, as well as non-invasive ventilation procedure: all the therapeutic procedures that can be offered to these patients in addition to the classic surgical treatments of anterior aortopexy and posterior tracheopexy.

A general discussion was held at the end of each section, highlightening how there is still no unity of opinion between the various Italian pediatric center. While regarding some sections, such as the Clinical presentation of the patient with TM, there was a general consensus, other sections such as the Diagnostic tests (need to perform a dynamic bronchoscopy) or the indications for Surgical treatment (which and when), there was a certain discrepancy in views. The indications for surgical treatment was the most controversial topic: some centers had a more conservative attitude, while others placed indication for TM surgery earlier in the clinical history, above all with the aim of anticipating and preventing the appearance of complications, such as protracted bacterial bronchitis and the development of bronchiectasis.

We recognize that the final result of all this is not easily labelable; netherless, the best definition that can be attributed to our work is: a summary of a multicentric Italian experience on tracheomalacia, as stated in the title. Our intentions, our hope is that this work can be the basis for a future national guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of tracheomalacia. We also hope that the publication of this paper may be of interest to all specialists who, even outside our country, are interested in this pathology, stimulating a broader knowledge of this pathology and of all the best diagnosis and treatments.

2. The Clinical History and the Typical Two-Tone / Biphasic Cough of the Patient with Tracheomalacia (TM)

In pediatric age, the central airways are more flexible and mobile, with more yielding tracheal walls tending to anteroposterior diameter (APD) collapse, thus easily allowing partial or complete occlusion of the lumen [

1]. In its intrathoracic course, the trachea is also surrounded by mediastinal vascular structures: the aortic arch and epiaortic arterial vessels, and its lumen can be easily narrowed by extrinsic vascular compression, given the close spatial contiguity relationships. All congenital anomalies of the aortic arch: right aortic arch with/without lusory subclavian artery, aberrant innominate artery (IA) , complete vascular rings with double aortic arch and left pulmonary artery sling, present in 1-2% of the general population, are conditions that can cause TM, secondary to extrinsic compression [

2]. Even in patients with primary TM, i.e. not accompanied by vascular anomalies, any condition that causes an increase in intrathoracic pressure: cough, crying, Valsalva maneuver, forced expiration, physical exertion, are all situations in which airway collapse is accentuated and biphasic or barking cough (brassy cough/barking seal cough) appears, present in 70-80% of cases [

3].

In these patients, the tone of the cough is biphasic because the first tone (physiological) is generated by the larynx, the second (pathological) is caused by the vibration of the tracheal wall when it collapses at the level of compression/malacia, with contact between the anterior and posterior walls, up to complete occlusion of the lumen. The biphasic cough can be recognized by the human ear because the harmonics of the sound coming from the larynx and those generated by the tracheal wall have different frequencies (Hz) [

4,

5].

In the diagnostic pathway, if the patient at the time of the visit is not already coughing with a biphasic cough, it is important to ask parents:

In many patients, biphasic cough occurs only in conjunction with a respiratory infection when they are coughing hard, which can lead to delayed diagnosis of TM. In addition to patients with typically biphasic cough, TM should also be considered in patients with recurrent wheezing or those mistakenly labeled as asthmatic and not responding to usual inhalation therapy, which is very common if the patient also has allergic sensitization [

6]. Reduced exercise tolerance and exertion-induced cough can also be symptoms present in patients with TM: the increased intrathoracic pressure worsens airway collapse, so as these patients are frequently misdiagnosed as having asthma [

7]. Severe TM is typically clinically evident from birth, characterized by cyanosis stridor even during normal breathing apnea; cardiac arrest or sudden infant death may rarely occur. These cases require intubation and are patients who are then difficult to extubate, unless surgically treated by removing the vessel compressing the trachea, if malacia is secondary to extrinsic compression.

Airway collapse during expiratory efforts and consequent ineffective coughing, with patients unable to expectorate effectively, are all factors that can cause altered secretion clearance, leading to mucus accumulation with increased risk of recurrent respiratory infections and chronic/ persistent productive cough: clinical picture of protracted bacterial bronchitis (PBB) [

8,

9]. In Kompare’s study, in a population of 70 patients with PBB, tracheobronchial malacia (TBM) was present in 74% of them, so it is important to think about TBM especially in patients with PBB [

8].

In the presence of a biphasic cough and a clinical history of recurrent/persistent respiratory infections, second-level diagnostic investigations have to be performed: chest computed tomography (CT) with contrast medium (CM) plus S/DVBS [

10,

11,

12]. After these investigations, every patient is then discussed within our Institute’s Tracheal Team (TT), consisting of: pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, cardiologists, otolaryngologists, radiologists, gastroenterologists, and anesthesiologists for case-by-case therapeutic decisions.

Discussion. All the partecipants underlined the importance of recognizing the two-tone cough as the clinical sign that should suggest the presence of tracheomalacia. It was also emphasized that the two-tone cough generally appears after two years of age, when the patient is able to cough effectively enough to generate a significant increase in intrathoracic pressure that causes the collapse of the tracheal lumen in the presence of TM. Last but not the least, when TM is suspected, the clinical history must be very accurate regarding the recurrence of lower respiratory tract infections,

3. Diagnostic Tests

3.1. Imaging Techniques

The “gold standard” for the diagnosis of TM and TBM is represented by videobronchoscopy (VBS), but the usefulness of various imaging techniques has been demonstrated, so as to integrate the endoscopic data:

Chest radiography (CXR): has not been shown to be useful for the diagnosis of TBM, although it can visualize the tracheal lumen, which in some cases may be focally slightly lateralized in cases of extrinsic compression from the aortic arch.

Tracheobronchography-fluoroscopy (TBG-TBF): these examinations are often performed concurrently with endoscopic examination in the operating room under general anesthesia. Isoosmolar CM is used through the working channel of a bronchoscope, obtaining an immediate and panoramic evaluation of the airways. In particular, information is obtained on airway dimensions (even downstream from stenosis), morphology (normal or abnormal bronchial bifurcation, v. isomerisms), as well as changes in tracheal lumen during different phases of respiration. TBG is also very useful as a guide for subsequent interventional procedures, favoring precise luminal localization of devices (balloon tracheoplasty, cutting balloon, bioabsorbable stent) [

13,

14].

Esophagography-fluoroscopy (EG-EF): are performed for searching tracheoesophageal fistulas (TEF) often present in esophageal atresia (EA), frequently associated with TM. Diagnostic accuracy for some is 84%, for others lower [

15]. CT can demonstrate the presence of the TEF, but definitive diagnosis on patency or not of the fistula is certainly entrusted to endoscopy with direct injection of CM into the fistula injection through the working channel of the endoscope

Computed tomography (CT): continuously evolving imaging technique, rapid and non-invasive. Provides an excellent overall view, independent of body size, high spatial/temporal resolution and allows multiplanar and volumetric reconstructions (MPR, MinPR, MipPR, Volumetric 3D). Can be performed on children of all ages; anesthesia/sedation may be necessary under 5 years of age. Flash Monophasic Technique performed with single scan, after intravenous injection of CM, provides information on airway morphology (but not dynamics), visualizing airways even distal to any obstructions, on mediastinal vessels that exert compression on the trachea or bronchi and can also highlights any mediastinal pathologies. CT shows cardiovascular anomalies compressing airway such as: right aortic arch, complete/incomplete double aortic arch, pulmonary sling anomalous, aberrant IA, all causing more or less severe TBM [

16]. TM is very frequently associated with EA; CT can demonstrate malacia and extrinsic tracheal compression with significant reduction of the tracheal ADP at the point of intersection with IA. CT can also demonstrate irreversible lung damage such as bronchiectasis formation, caused by chronic recurrent lung infections resulting from reduced mucociliary clearance in TBM. Skeletal anomalies (e.g., pectus excavatum, scoliosis) that can cause airway compression and consequent TBM are also demonstrated. CT also evaluates tracheal compressions caused by space-occupying mediastinal lesions. Virtual bronchoscopy obtained with 3D airway reconstruction on CT images has not been very sensitive (<75%) in detecting TBM [

17,

18].

Dynamic CT (DCT) allows visualization of the entire airway in a single gantry rotation using dynamic volumetric scanning technique. Images can be acquired over 1 or 2 respiratory cycles with total scan time less than 2 seconds while the child is breathing at tidal volume during this rapid acquisition. Anesthesia is not necessary, making the exam comfortable and drastically reducing the patient risks. Dynamic imaging throughout the respiratory cycle allows accurate determination of end-inspiration/end-expiration phases in 3 dimensions (3D) with accurate determination of luminal collapse degree. The disadvantage of this technique is increased radiation dose to the patient, so it is performed only in selected cases [

19,

20].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the examination of choice for studying cervical or thoracic masses compressing or displacing the trachea in pediatric age (cervical lymphangioma, venous vascular malformation, neuroblastoma, duplication, lymphoma, teratoma). The main advantage of MRI is the lack of exposure to ionizing radiation while disadvantages are long acquisition times and lower spatial resolution than CT. Dynamic MRI for tracheomalacia is still limited to research rather than clinical application. High-field 3 Tesla scanners and dedicated coils are used. The Time-Resolved sequence can demonstrate the dynamic aspect of the airway during forced expiration [

1,

21].

In conclusion: we believe that the “gold standard” for diagnosing TBM is VBS supported by other imaging techniques. Among these, CT with CM is the technique that provides the most information for high-resolution imaging of airways, vessels, and lung parenchyma, as well as associated anomalies causing TBM of vascular or skeletal nature. Third-generation equipment has achieved a reduction in radiation dose and amount of CM used, decreased need for anesthesia/sedation, and generally shortened exam execution times. DCT provides information on airway caliber changes during inspiration and expiration phases but, due to higher radiation dose required compared to Flash Monophasic CT, it is used only in selected cases.

3.2. Spirometry

Spirometry / pulmonary function test (PFT) is the most standardized test for evaluating respiratory function in both adults and children when the patient is cooperative. We know how airway obstructions can occur at both the extrathoracic level (pharynx, larynx, and the initial extrathoracic portion of the trachea) and the intrathoracic level (intrathoracic trachea and main bronchi). Although it has not yet been well defined which is the best test to use for the diagnosis of TM, many studies show that patients with TM present a frankly obstructive pattern on PFT, associated with a Flow/Volume Curve (F/VC) morphology tending to plateau in the expiratory phase [

1,

22].

In the case of a tracheal obstruction, the functional parameters that can be most involved are predominantly expiratory, primarily with a reduction in Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF), and often also in Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1) in the case of severe obstructions [

23]. However, it should be noted that clinical symptoms are often not directly proportional to the severity of spirometry data, and mild TM can often be present even when PFT is almost normal.

In the case of a frank intrathoracic obstruction as in TM, endotracheal airway pressure during forced inspiration is greater than pleural pressure, so the inspiratory portion of the flow-volume curve more easily appears normal. Conversely, during forced expiration, when pleural pressure is greater than endotracheal airway pressure, this will tend to reduce airway diameter, especially at the locus of minus resistance. This results in an increase in obstruction, corresponding to a flattening/decapitation of the expiratory portion of the F/VC, with a marked reduction, especially in Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF). Last but not least, PFR data and F/VC morphology in patients with TM show no change after bronchodilation [

24].

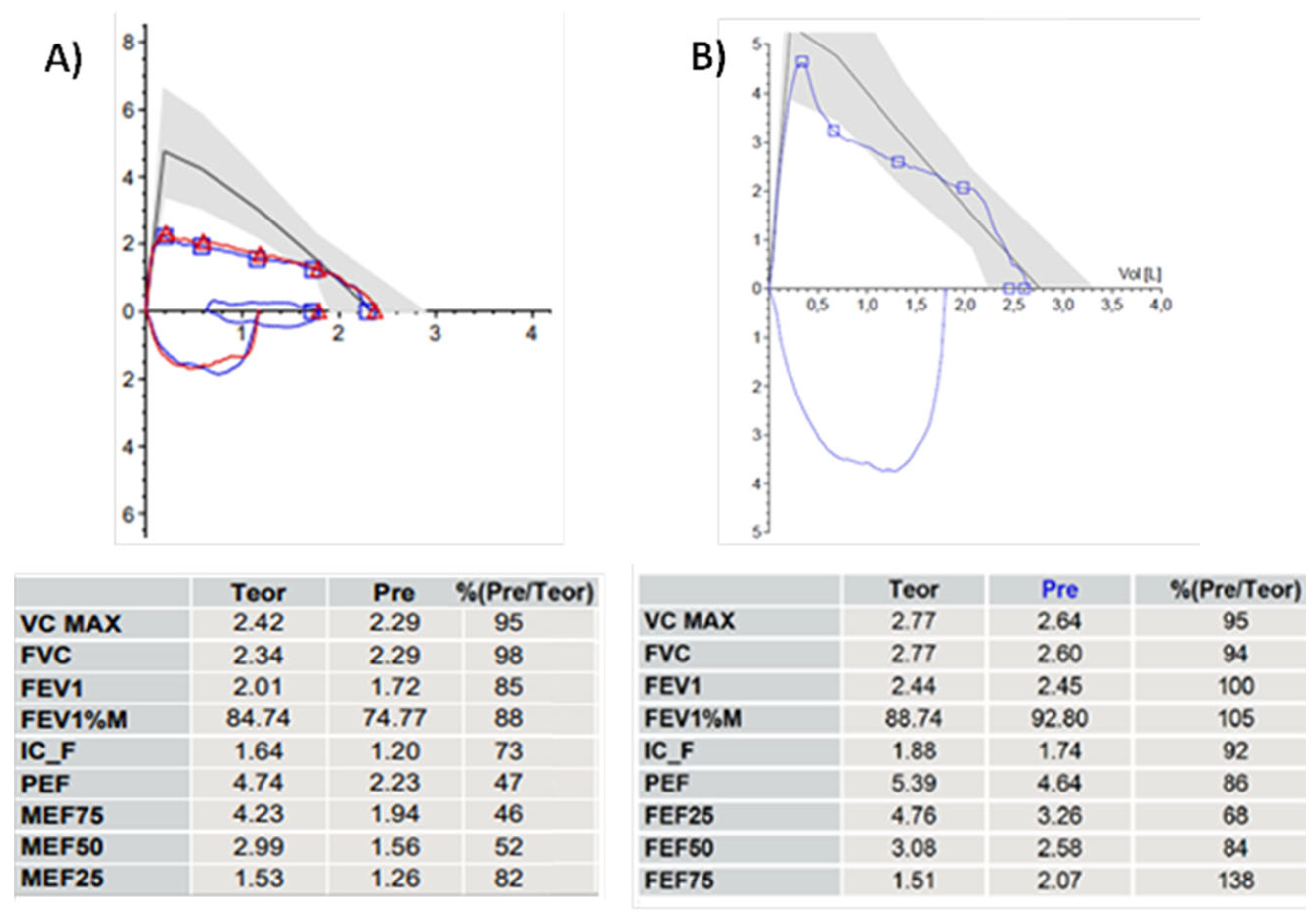

Figure 1.

10-year-old girl with hitherto undiagnosed balanced double aortic arch. The patient had always dyspnea with even moderate physical activity and dysphagia for elastic foods such as meat boluses. A) PFT before and B) 14 months after vascular ring opening surgery, performed few days after the first PFT. The change in the morphology of the F/VC is impressive, going from a box shape to an almost normal morphology with a PEF value that increases from 47% to 86% of the theoretical values after surgery. Abbreviations. PFT: Pulmonary Function Test; F/VC: Flow/Volume Curve. PEP: Peak Expiratory Flow.

Figure 1.

10-year-old girl with hitherto undiagnosed balanced double aortic arch. The patient had always dyspnea with even moderate physical activity and dysphagia for elastic foods such as meat boluses. A) PFT before and B) 14 months after vascular ring opening surgery, performed few days after the first PFT. The change in the morphology of the F/VC is impressive, going from a box shape to an almost normal morphology with a PEF value that increases from 47% to 86% of the theoretical values after surgery. Abbreviations. PFT: Pulmonary Function Test; F/VC: Flow/Volume Curve. PEP: Peak Expiratory Flow.

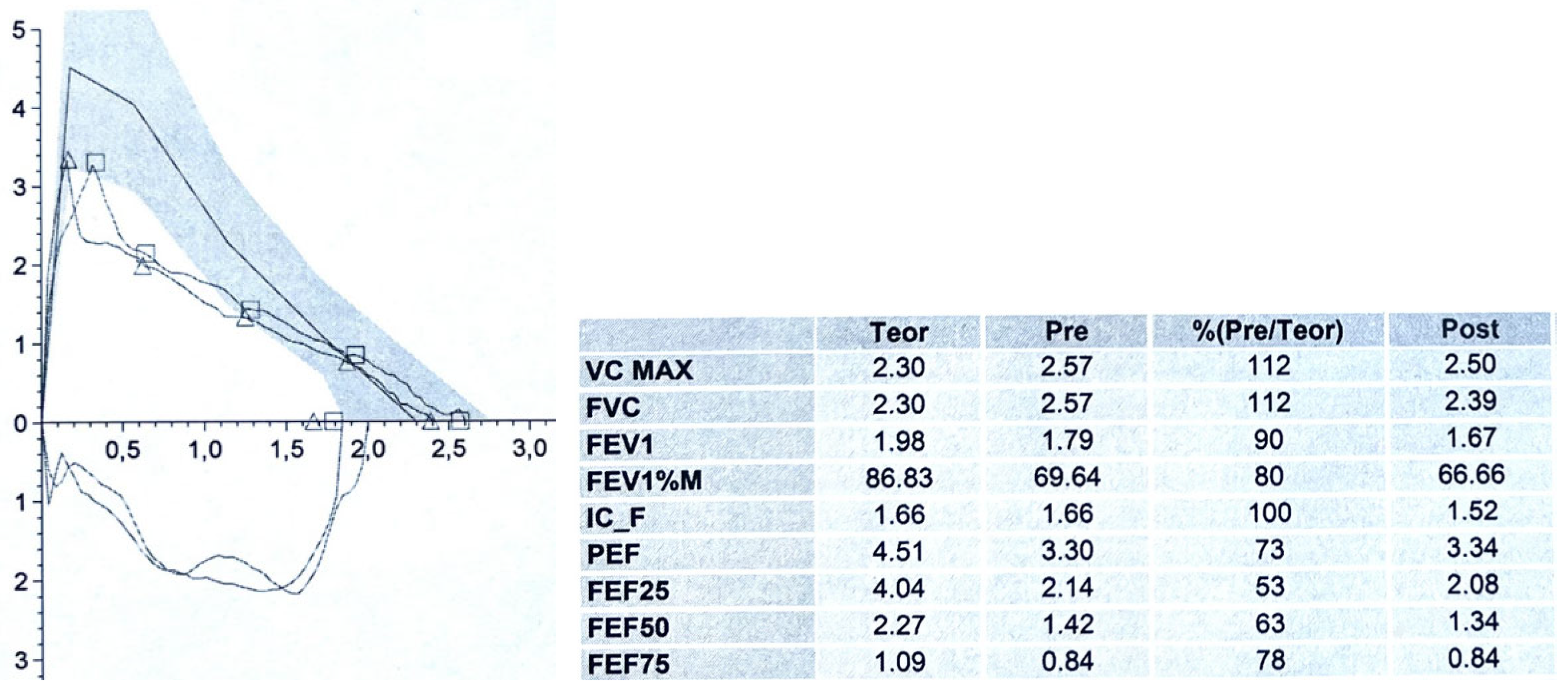

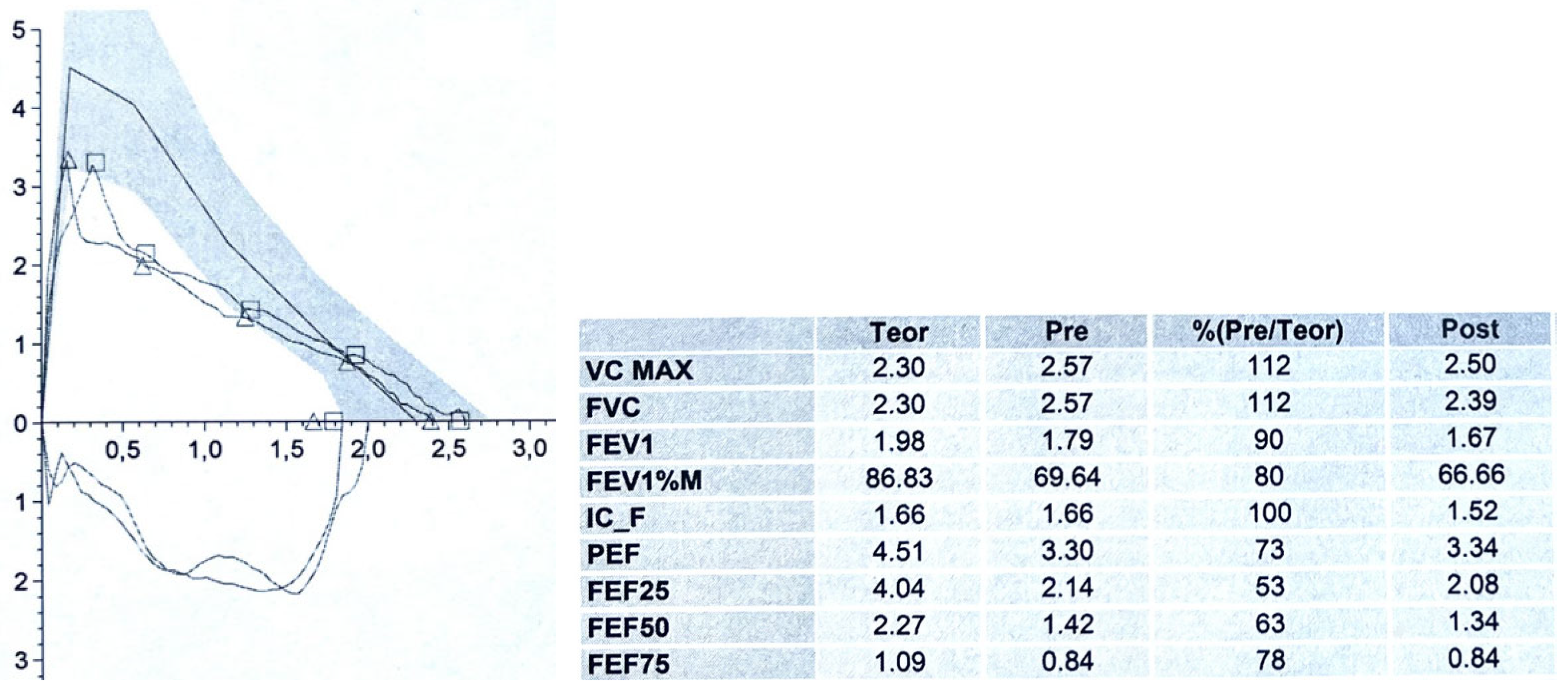

Figure 2.

A 9-year-old boy with two-toned barking cough since the age of 2, present above all during intercurrent infectious events and physical activity: especially running. The CT scan with CM and VBS showed anterior tracheal compression from the IA with a decrease in the tracheal lumen of approximately 50%. PFT demonstrates normal lung volumes, the expiratory curve has a reduced PEF: 73% of the theoretical value and, immediately after the peak, a clear incision is present with a sharp decrease in FEF25, FEF50 and FEF75: 53, 63 and 78% of the theoretical value respectively. No response to bronchodilator. The parents were offered OAA surgery, which was not accepted. The patient is treated with topical cortisone during the infectious events, with poor clinical response. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; VBS: Videobronchoscopy; IA: Innominate Artery; PFT: Pulmonary Function Test; PEF: Peak Expiratory Flow. FEF: Forced Expiratory Flow; OAA: Open Anterior aortopexy.

Figure 2.

A 9-year-old boy with two-toned barking cough since the age of 2, present above all during intercurrent infectious events and physical activity: especially running. The CT scan with CM and VBS showed anterior tracheal compression from the IA with a decrease in the tracheal lumen of approximately 50%. PFT demonstrates normal lung volumes, the expiratory curve has a reduced PEF: 73% of the theoretical value and, immediately after the peak, a clear incision is present with a sharp decrease in FEF25, FEF50 and FEF75: 53, 63 and 78% of the theoretical value respectively. No response to bronchodilator. The parents were offered OAA surgery, which was not accepted. The patient is treated with topical cortisone during the infectious events, with poor clinical response. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; VBS: Videobronchoscopy; IA: Innominate Artery; PFT: Pulmonary Function Test; PEF: Peak Expiratory Flow. FEF: Forced Expiratory Flow; OAA: Open Anterior aortopexy.

3.3. Static and Dynamic VBS (S/DVBS): Endoscopic Pictures in Clinical Cases

TM can occur due to:

Primary malacia due to intrinsic alteration of the cartilage of the respiratory tract walls, which is less common compared to:

Secondary malacia if the normally shaped cartilage is then deformed by extrinsic compression, usually of vascular origin, on the anterior tracheal wall;

Hypermobility of the posterior wall (pars membranacea), which protrudes exaggeratedly and pathologically into the tracheal lumen during expiration and with coughing.

In all these conditions, which can also coexist, the end result is a reduction in the tracheal lumen. The ERS statement [

1] defines the severity of TM based on the percentage of this reduction, evidenced during videobronchoscopy (VBS), so that TM is classified as:

Mild TM: reduction between 50-75%

Moderate TM: reduction between 75-90%

Severe TM: reduction is > 90%

This stratification of the degree of TM is flawed by the fact that the endoscopic evaluation of the degree of TM can be very subjective, which clearly affects subsequent therapeutic conduct. Another limitation of this classification is that the reduction in lumen is judged during quiet breathing, without considering that the trachea is not a rigid tube but has elastic and yielding walls especially in children, so its patency can change greatly during the respiratory cycle and especially when the patient coughs.

In our opinion, VBS performed in pediatric patients in the operating room under sedation should be:

To better understand why VBS should also have a dynamic phase, we present 3 clinical cases, valuated at Pediatric Pneumology Unit IRCCS G. Gaslini, Genoa, Italy.

CLINICAL CASE 1: boy, 5 years old, with recurrent biphasic cough. The patient was valuated with:

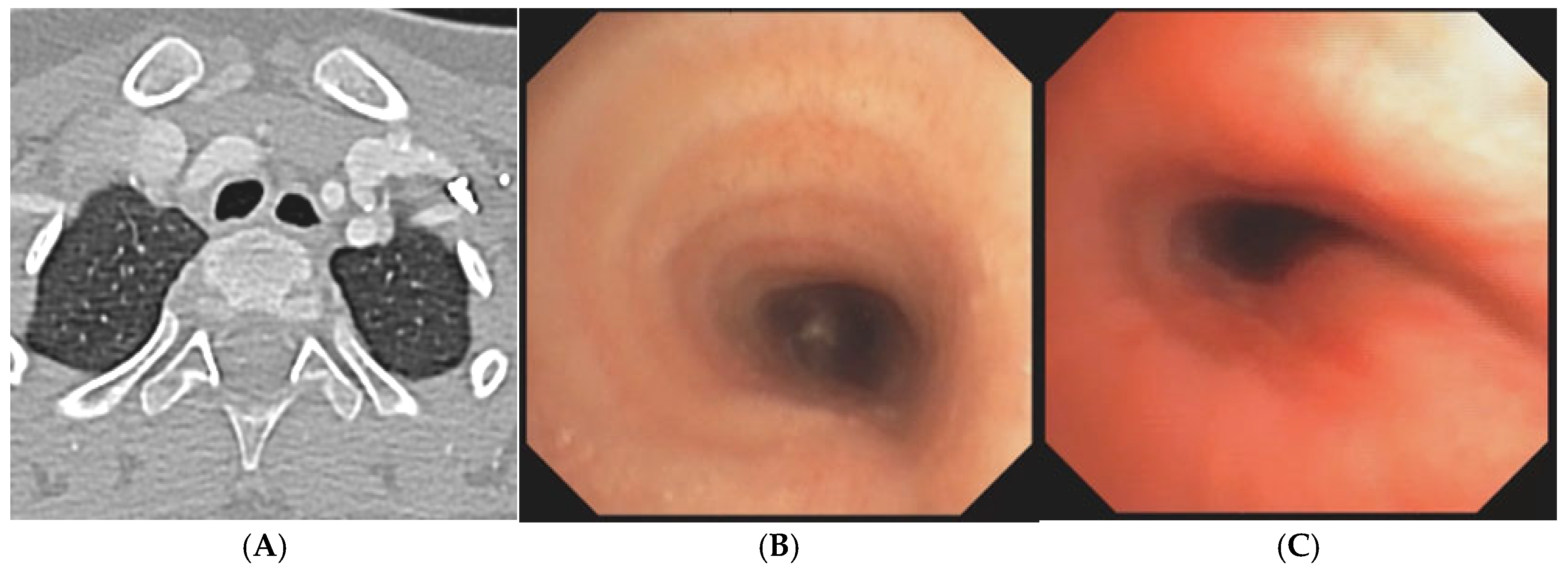

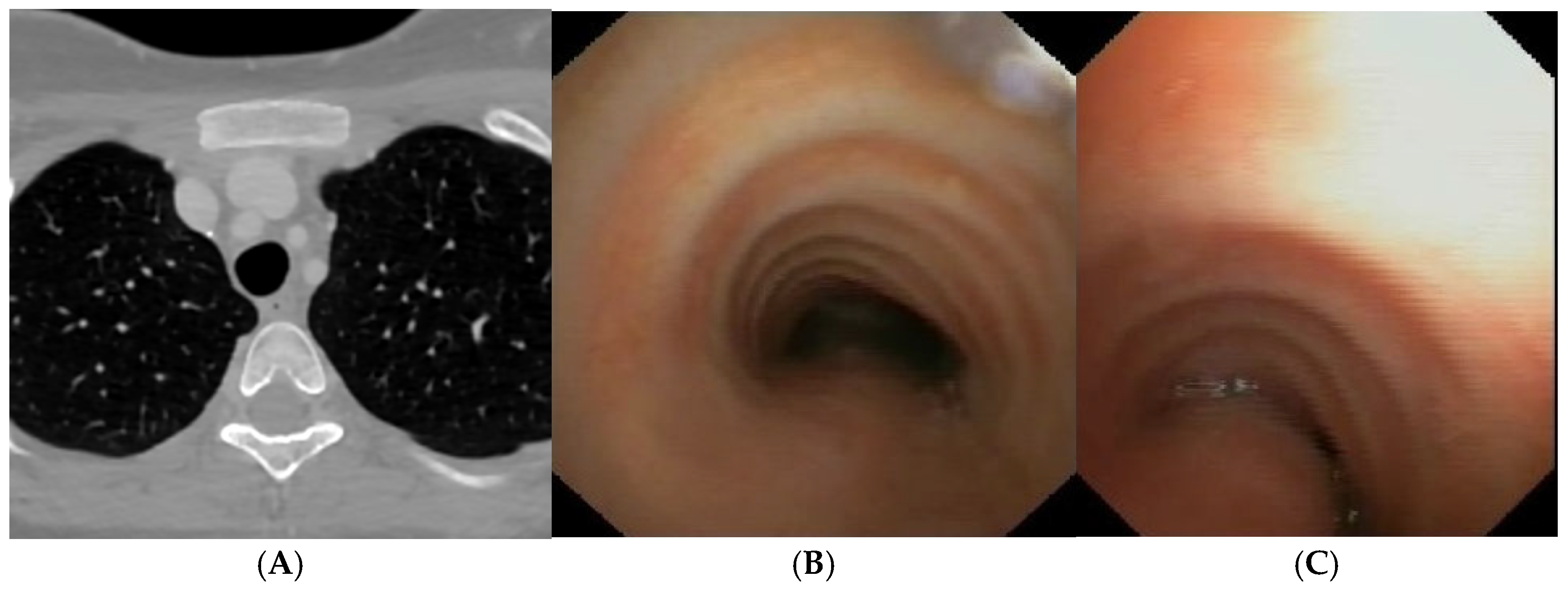

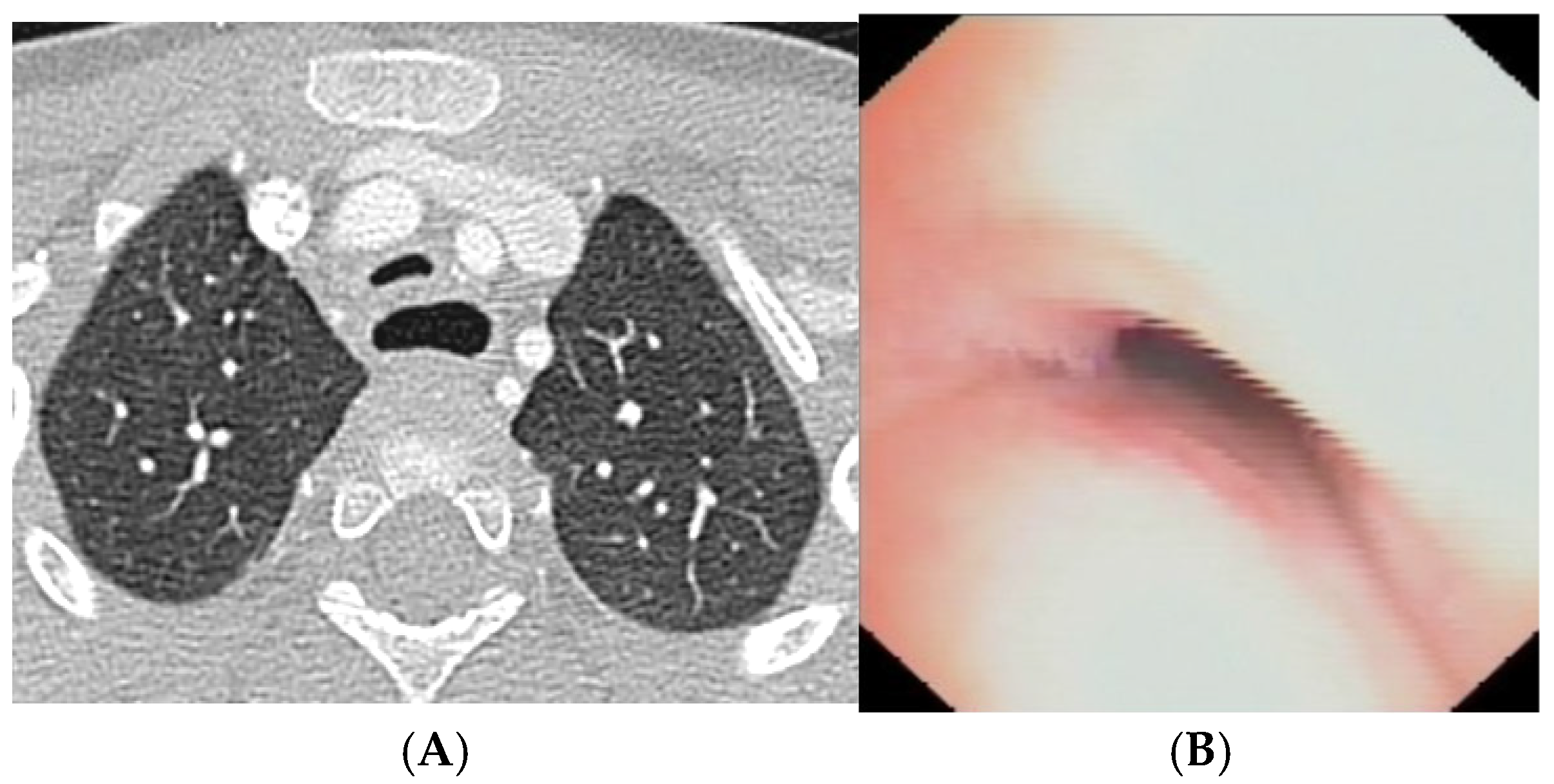

Figure 3.

A) Chest CT with CM: tracheal lumen only slightly deformed at the junction with the IA. Fig. B) SVBS, as CT, shows only slight extrinsic compression at the junction of the IA. Fig. C) DVBS, when the patient attempts to cough by performing abdominal straining: hypermobility of the pars membranacea, with subtotal occlusion of the tracheal lumen at the level of even slight extrinsic compression. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; IA: Innominate Artery; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 3.

A) Chest CT with CM: tracheal lumen only slightly deformed at the junction with the IA. Fig. B) SVBS, as CT, shows only slight extrinsic compression at the junction of the IA. Fig. C) DVBS, when the patient attempts to cough by performing abdominal straining: hypermobility of the pars membranacea, with subtotal occlusion of the tracheal lumen at the level of even slight extrinsic compression. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; IA: Innominate Artery; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

The patient is discharged with bac”grou’d medical therapy: Inhaled corticosteroid and respiratory physiotherapy with Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) mask, clinical follow-up after 6 months.

CLINICAL CASE 2: girl, 8 months old, prenatal diagnosis of right aortic arch with lusory subclavian artery, confirmed at birth by echocardiogram. Absence of respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, good growth. According to our Institute’s internal protocol, we performed:

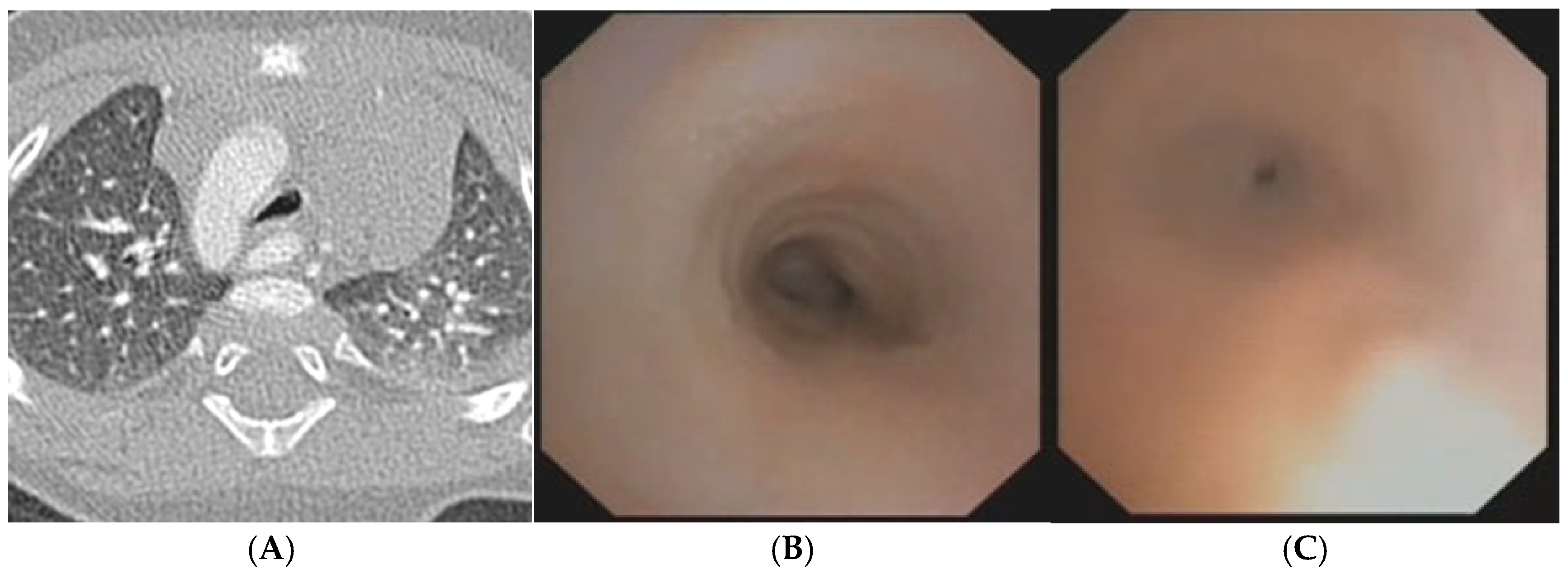

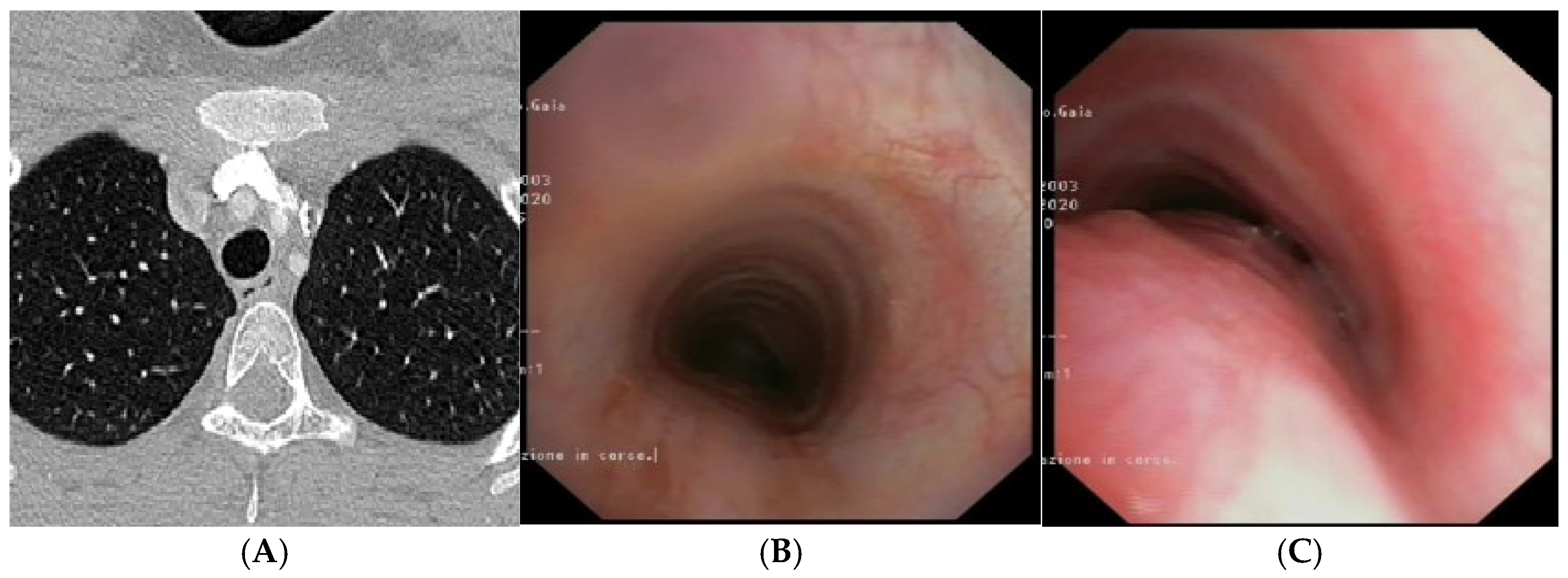

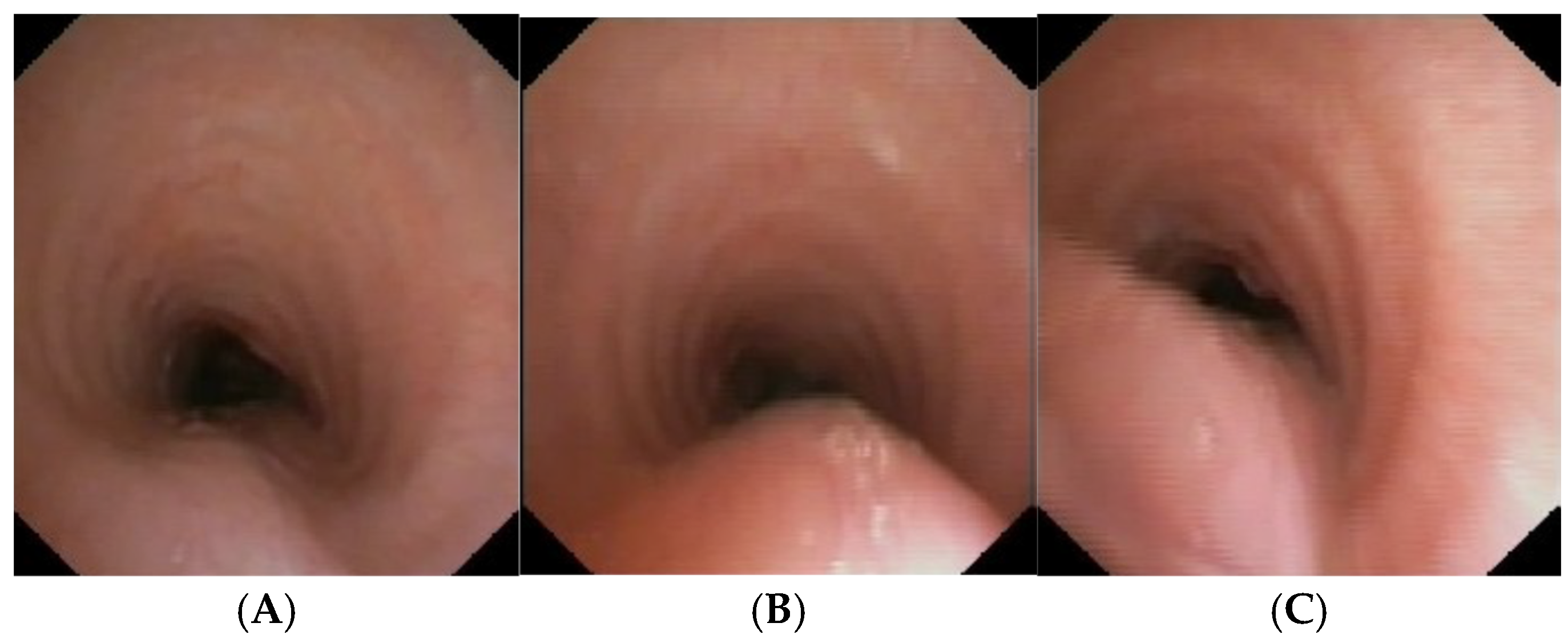

Figure 4.

A) Chest CT with CM: right aortic arch with lusory subclavian artery and marked compression/deformation of tracheal lumen at this level. Fig. B) SVBS: well-patent tracheal lumen up to the junction between middle and distal third tracheal lumen, where pulsating extrinsic compression appears on the anterolateral right wall significantly deforming and narrowing tracheal lumen by more than 50% compared to upper area. Patent carina but main right bronchus inlet slightly deformed by aortic arch. Fig. C) DVBS, stimulating cough reflex under abdominal straining: almost complete occlusion of tracheal lumen. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 4.

A) Chest CT with CM: right aortic arch with lusory subclavian artery and marked compression/deformation of tracheal lumen at this level. Fig. B) SVBS: well-patent tracheal lumen up to the junction between middle and distal third tracheal lumen, where pulsating extrinsic compression appears on the anterolateral right wall significantly deforming and narrowing tracheal lumen by more than 50% compared to upper area. Patent carina but main right bronchus inlet slightly deformed by aortic arch. Fig. C) DVBS, stimulating cough reflex under abdominal straining: almost complete occlusion of tracheal lumen. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

Cardiac surgery followed TT discussion: sectioning of atretic left arch, resection of Kommerell’s diverticulum with reimplantation of left lusory subclavian artery on ipsilateral carotid artery. SVBS one year after surgery: well-preserved tracheal lumen up to distal third, where only slight pulsating deformity on anterolateral right wall at site of aortic arch; in DVBS: even when patient performs abdominal straining, the occlusion of tracheal lumen is no longer present.

CLINICAL CASE 3: girl, 15 years old, clinical history of biphasic cough and recurrent respiratory infections. Already diagnosed with asthma with various inhalation therapies without clinical benefit. The patient was valuated with:

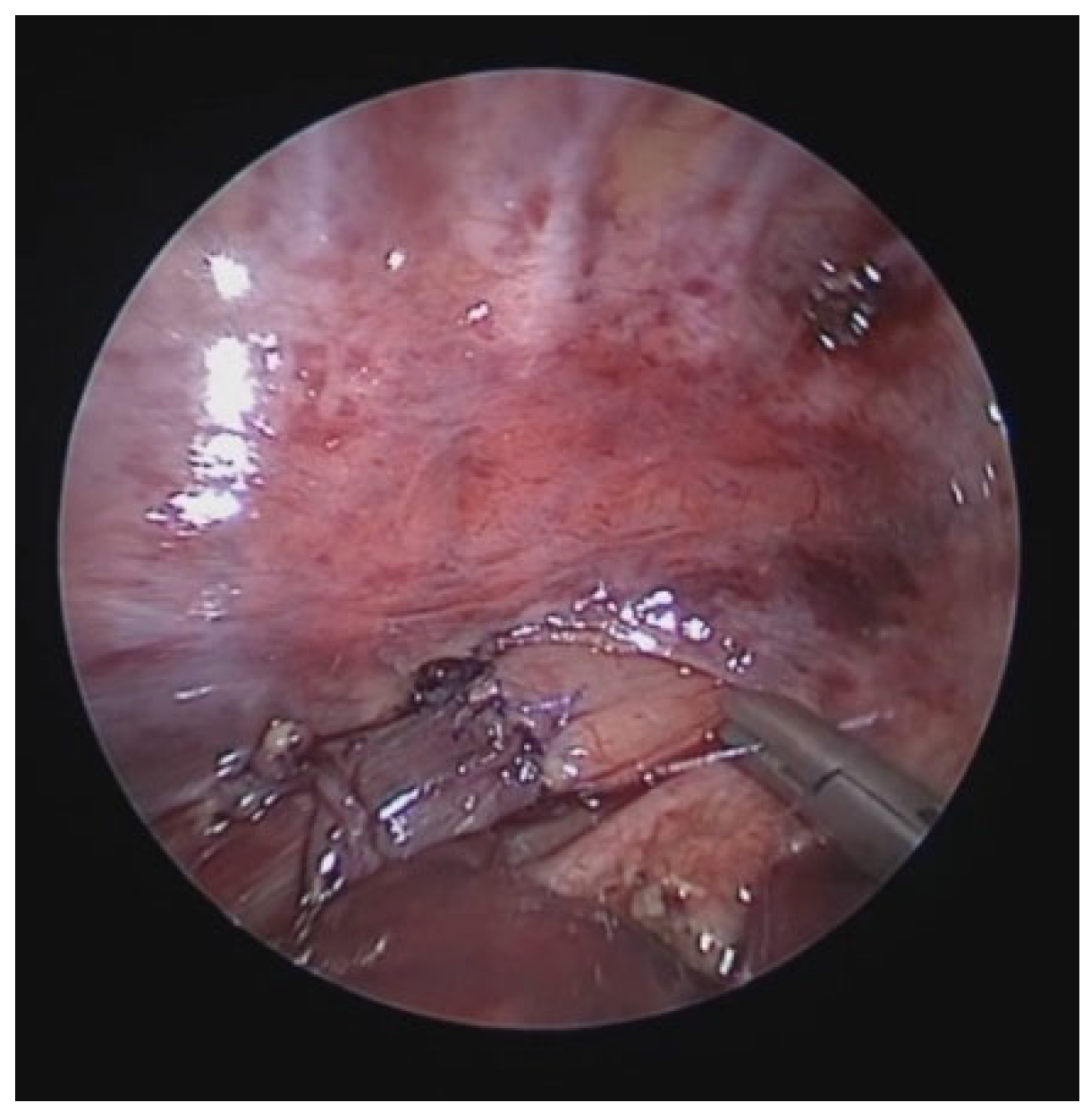

Figure 5.

A) Chest CT with CM: slight tracheal compression from IA. Fig. B) SVBS: well-preserved tracheal lumen up to junction between middle and distal third where clear pulsating extrinsic compression from IA deforms tracheal lumen and granulomas are present on pars membranacea at this level. Fig. C) DVBS: when patient performs abdominal straining, pars membranacea appears hypermobile and protrudes pathologically into tracheal lumen, which at level of extrinsic compression becomes completely occluded by contact between pars membranacea and anterior wall. The presence of granulomas at this level proves this contact occurs recurrently. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; IA: Innominate Artery; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 5.

A) Chest CT with CM: slight tracheal compression from IA. Fig. B) SVBS: well-preserved tracheal lumen up to junction between middle and distal third where clear pulsating extrinsic compression from IA deforms tracheal lumen and granulomas are present on pars membranacea at this level. Fig. C) DVBS: when patient performs abdominal straining, pars membranacea appears hypermobile and protrudes pathologically into tracheal lumen, which at level of extrinsic compression becomes completely occluded by contact between pars membranacea and anterior wall. The presence of granulomas at this level proves this contact occurs recurrently. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; IA: Innominate Artery; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

After collegial discussion with the TT: OAA was performed (see “Surgical Treatments” later). At the clinical follow-up one year later: less frequent infectious episodes, but still present biphasic cough attacks.

Figure 6.

A) Chest CT with CM: good outcome of the OAA procedure, with well-preserved tracheal lumen even at the junction with the IA. Fig. B) SVBS: at the junction between the middle and distal third, no more transmitted pulsation, persistent reduction of the lumen by 25-30%, no more visible granulomas. Fig. C) DVBS: marked protrusion of the pars membranacea with abdominal straining, occluding the lumen by about 80-90%. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; OAA: Open Anterior Aortopexy; IA: Innominate Artery; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 6.

A) Chest CT with CM: good outcome of the OAA procedure, with well-preserved tracheal lumen even at the junction with the IA. Fig. B) SVBS: at the junction between the middle and distal third, no more transmitted pulsation, persistent reduction of the lumen by 25-30%, no more visible granulomas. Fig. C) DVBS: marked protrusion of the pars membranacea with abdominal straining, occluding the lumen by about 80-90%. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; OAA: Open Anterior Aortopexy; IA: Innominate Artery; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

After discussion with the TT: PT was performed (see “Surgical Treatments” later). Follow-up 6 months after the surgery: significant clinical improvement with the disappearance of the biphasic cough.

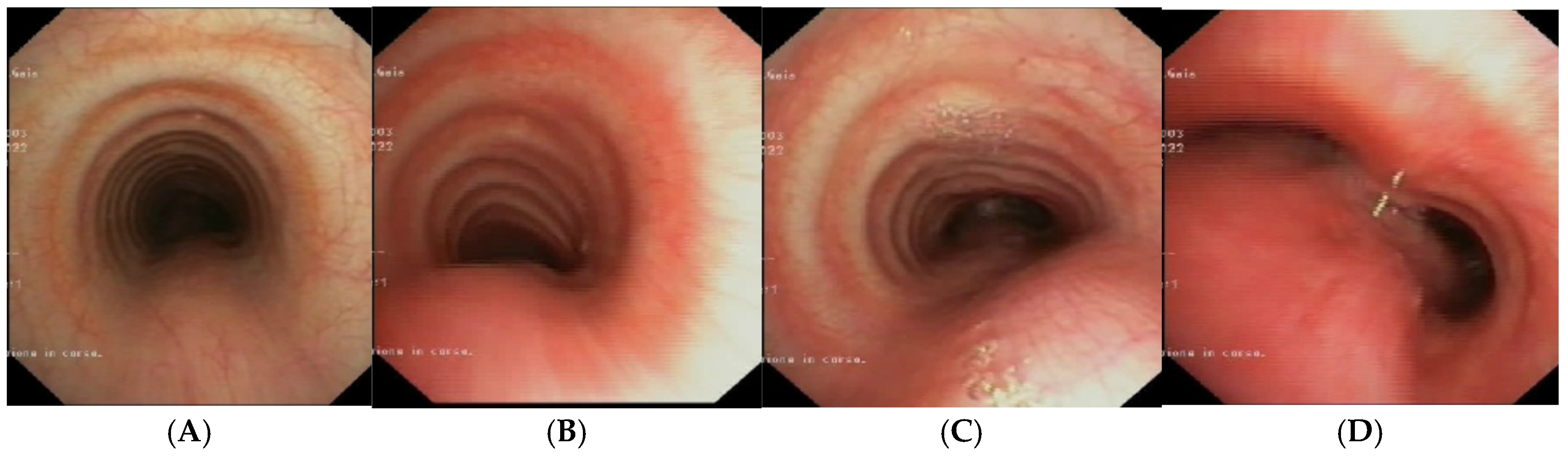

Figure 7.

A, B) SVBS: well-preserved tracheal lumen, only moderately deformed at the site of previous extrinsic compression. C, D) DVBS: physiological protrusion of the pars membranacea into the tracheal lumen, which remains well patent even under abdominal straining (slight bulging only above the carina). Abbreviations. SVBS: Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 7.

A, B) SVBS: well-preserved tracheal lumen, only moderately deformed at the site of previous extrinsic compression. C, D) DVBS: physiological protrusion of the pars membranacea into the tracheal lumen, which remains well patent even under abdominal straining (slight bulging only above the carina). Abbreviations. SVBS: Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS: Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

These cases demonstrate the importance of performing, in suspected TM, both SVBS and DVBS to highlight changes in the tracheal lumen when intrathoracic pressure increases, such as during abdominal straining. These changes are not visible during spontaneous breathing, but are responsible for the clinical symptoms presented by the patient in everyday life.

3.4. Indications for Surgical Treatment

Primary TM (rarer), due to developmental alteration of the organ, or secondary TM (more common), due to extrinsic compression, mostly vascular, is the most common congenital tracheal anomaly, affecting about 1 in 2,000 children [

1].. Despite its relative frequency, the management of patients with TM varies greatly from center to center, lacking a clear decision-making algorithm to guide the clinician from diagnosis to treatment [

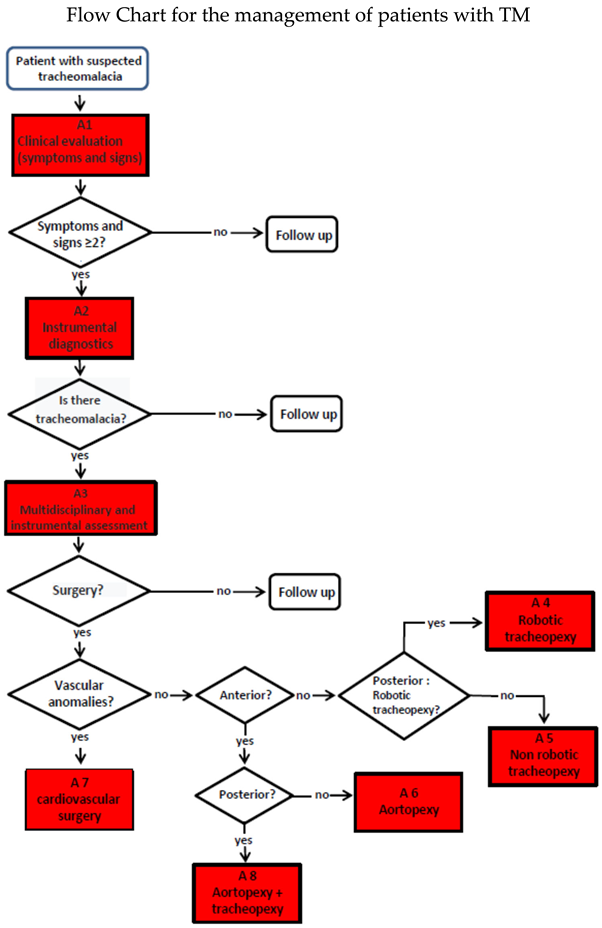

27]. Within the TT, composed by pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, cardiothoracic surgeons, otolaryngologists, radiologists, gastroenterologists, and anesthesiologists, we discuss individual clinical cases in the weekly team meetings, and we felt the need to formulate a flow chart:

Although a Flow Chart for the management of patients with TM has been broadly established, there is still no standardization of:

The degree of clinical severity: biphasic cough, stridor, wheezing, recurrent respiratory infections, dyspnea, respiratory failure.

The degree of TM severity according to radiological imaging (chest CT with CM) and endoscopic criteria: S/DVBS.

Within the Gaslini Institute TT, we felt the need to develop a tracheomalacia score (TMS) that takes into account both clinical symptoms: clinical score, and endoscopic data: endoscopic score, to help choose the best therapeutic option for each TM patient: 1) vigilant waiting with medical therapy and respiratory physiotherapy, 2) AA or 3) PT.

-

TM Clinical Score (TMCS), characterized by the

absence: score =

0 or

presence: score =

1 of certain symptoms (each symptom contribute with its score to the final sum score), divided by age groups, which must be present even in substantial well-being, outside of acute infectious events:

| 0-2 years |

- ☐

Apparent Life-Threatening Event (ALTE) - ☐

Biphasic or “choked” cough or abnormal tone - ☐

Inspiratory or expiratory stridor - ☐

Jugular or intercostal retractions - ☐

Recurrent pneumonia (>2 episodes) in a non-immunodeficient patient |

| 2-6 years |

- ☐

Recurrent/persistent biphasic cough - ☐

Inspiratory or expiratory stridor with or without jugular or intercostal retractions - ☐

Recurrent and prolonged lower respiratory tract infections (>6/year) in a non-immunodeficient patient - ☐

Poor resistance to play - ☐

Dysphagia or vomiting |

| > 6 years |

- ☐

Recurrent/persistent biphasic cough - ☐

Recurrent and prolonged lower respiratory tract infections (>6/year), in a non-immunodeficient patient - ☐

Poor resistance to physical activity/sports - ☐

Exertional cough, in the absence of bronchospasm - ☐

Dysphagia or vomiting/gastroesophageal reflux |

In cooperative patients who can perform spirometry with a correct F/VC, a score of 1 is assigned if the expiratory phase of the curve shows a box or plateau appearance (see above: 2.2. Spirometry).

In our Institute, each patient with suspected TM is evaluated according to this clinical score and, if at least 2 signs/symptoms are present, undergoes S/DVBS, and chest CT with CM, so to formulate:

-

TM Endoscopic Score (TMES), following the indications of the 2019 ERS statement on TBM in children [

1]. The S/DVBS, leads to the assignment of these scores:

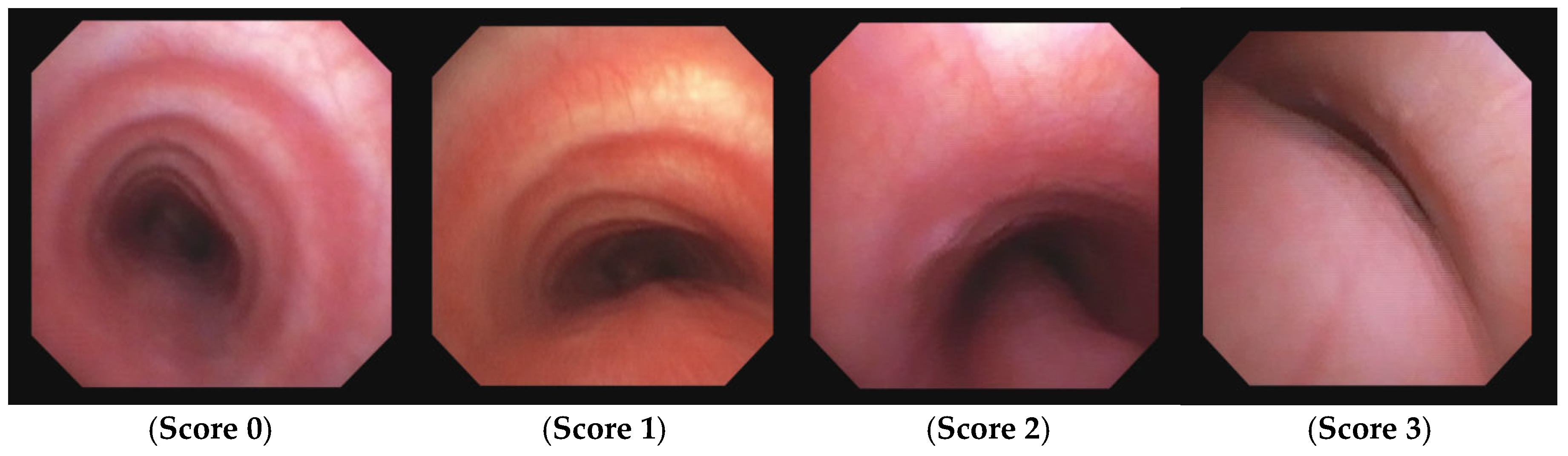

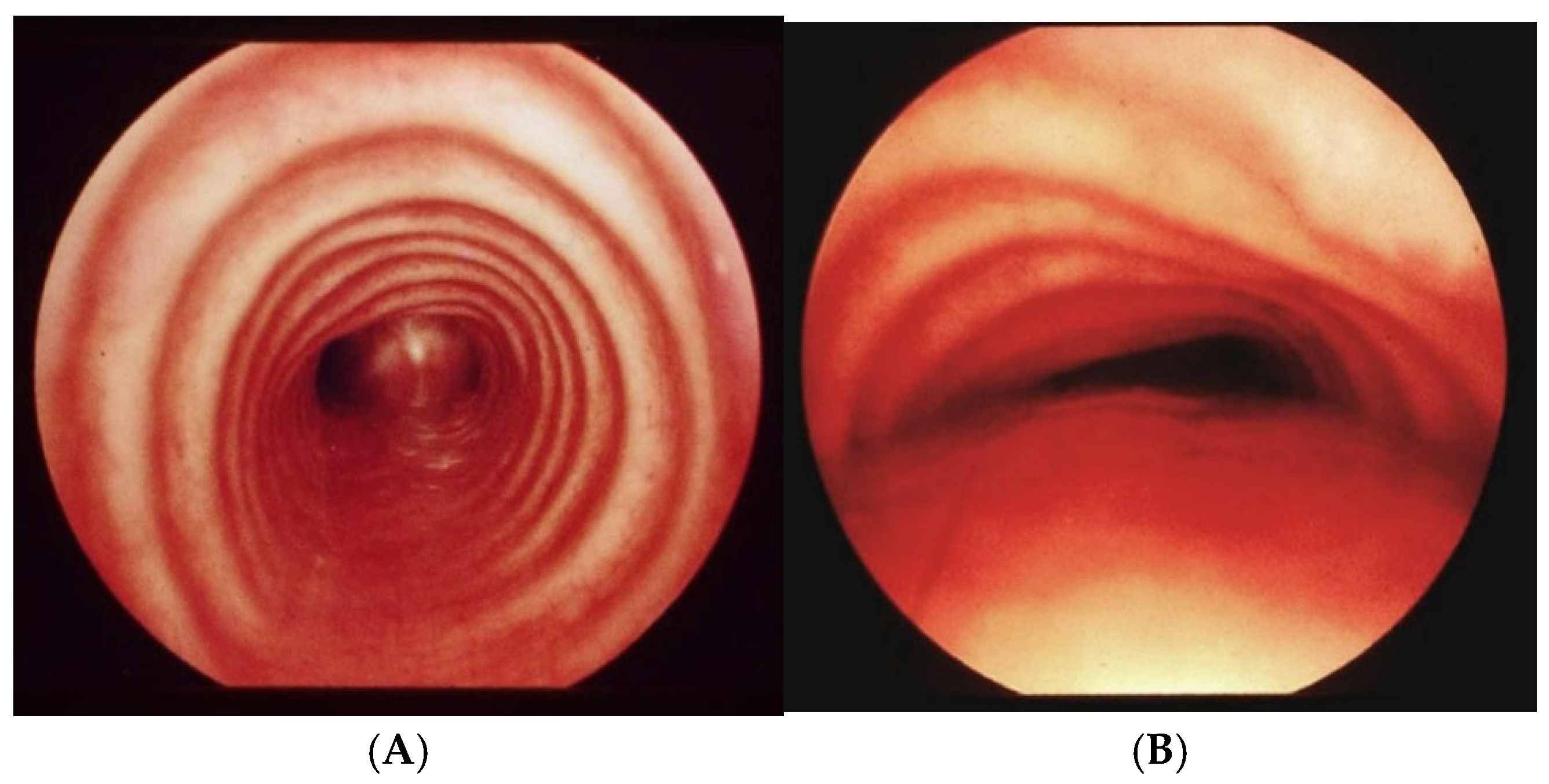

| Score: 0 |

Pulsating extrinsic deformation on the anterior tracheal wall, reduction of the APD of the trachea less than 50% compared to the suprastenotic tract, even during expiration. Good representation of the cartilaginous rings. |

| Score: 1 |

Reduction of the tracheal APD between 50% and 75% compared to the suprastenotic tract, absence of contact between the anterior tracheal walls and the pars membranacea even when the patient performs abdominal straining. Good representation of the cartilaginous rings. |

| Score: 2 |

Reduction of the APD of the trachea between 75% and 90% compared to the suprastenotic tract and/or anterior tracheal wall and pars membranacea tending to touch, without complete closure of the lumen even when the patient performs abdominal straining, poor representation of the cartilaginous rings. |

| Score: 3 |

Reduction of the APD of the trachea greater than 90% already during the expiratory phase, when the tracheal lumen completely closes.

|

Figure 8.

TMES Score 0 – 3, following the indications of the 2019 ERS statement on TM in children. Abbreviations. TMES: Tracheo Malacia Endoscopic Score; TM: Tracheo Malacia.

Figure 8.

TMES Score 0 – 3, following the indications of the 2019 ERS statement on TM in children. Abbreviations. TMES: Tracheo Malacia Endoscopic Score; TM: Tracheo Malacia.

The TMS is obtained by summing the TMCS and the TMES: if the total score is greater than 5, a surgical approach is indicated; otherwise, only medical therapy and clinical follow-up are recommended.

The development of a third score, the TM radiological score (TMRS), is currently in progress through a retrospective observational study (resulting from the collaboration between pulmonologists, radiologists, and surgeons) with the aim of correlating chest CT imaging (with evaluation of specific markers) with the clinical and endoscopic data of patients with TM.

Discussion. The flow chart for the management of the patients with TM was shared and approved in its lines. The main focus was on the importamce of bronchoscopy with the dynamic phase, so as to be able to visualize how the tracheal lumen behaves with the increase in intrathoracic pressure, such as when the patient tightens his abdomen to cough. Not all pediatric pulmonology centers directly perform bronchoscopy: the procedure is often performed by otolaryngologists or anesthesiologists, who more rarely perform dynamic bronchoscopy. All pediatric pulmonologists agreed on the importance of dynamic bronchoscopy and on the need to directly perform the procedure to obtain the most useful data to make surgical indications, and specifically whether anterior aortopexy or posterior tracheopexy. The need to develop a tracheomalacia score (TMS), that takes into account both clinical symptoms and endoscopic data, as a guide in choosing the best therapeutic option for each TM patient (as proposed by the Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery Unit Gaslini Children Hospital), was shared by most of the meeting participants. A verbal commitment to try to implement this tool was expressed, but a lot of work still needs to be done to have a TMS used as an usefull tool in various italian pediatric pulmonology centers to characterized TM patients.

4. Surgical Treatments

4.1. Introduction

The choice of treatment for TM depends on: the etiology and severity of TM itself, the general and respiratory clinical conditions of the patient, the presence of any comorbidities. Mild and moderate TM can be managed pharmacologically or non-invasively because, in most cases, there is an improvement in clinical manifestations as the patient grows. For the treatment of severe TM, a surgical approach is generally indicated, especially when there is a compromised respiratory condition, requiring mechanical ventilation, feeding difficulties, and recurrent episodes of bronchopneumonia or PBB [

1,

28].

The main surgical options for the treatment of TM are: 1) anterior aortopexy (AA), 2) posterior tracheopexy (PT), and, more rarely, 3) tracheal resection. The use of 4) resorbable endotracheal/bronchial stents, placed endoscopically, is also increasingly common, particularly in cases of surgical failure or when surgery is contraindicated.

The treatment TM is not standardized. In most centers, the first approach is usually medical treatment but, in non-responders or in severe cases, a surgical approach may be considered. In different centers, patients with TM receive different treatments according to local experience / preferences. In this paper, we summarize the most common surgical treatments for TM, focusing on the different approaches and the technical aspects of each technique. This is a multicenter symposium, and each speaker describes the preferred approach and technique performed in his center.

4.2. Open Anterior Aortopexy (OAA)

OAA (via right or left anterior thoracotomy, or sternotomy) has always been considered the standard procedure for the treatment of TM due to anterior tracheal vascular compression by an anomalous course of the IA [

29,

30]. At the Cardiosurgery Division of IRCCS G. Gaslini, Genoa, Italy, from June 2011 to December 2023, 131 patients with symptomatic tracheal vascular compression due to an anomalous course of the IA underwent OAA (Table 1).

Patient population

131 patients

Age: 5.1 ± 4.2 years (range 0.2 – 16.39 years)

Female: 32%, Male: 68%

TEF: 38 patients (29%)

Comorbidities: cardiopathy, chromosomal abnormalities, autism, etc.: 37 patients (28.2%)

107 patients (82%): Upper ministernotomy (split sternum)

24 patients (18%): Right or left anterior thoracotomy

Additionally, 6 patients with left main stem bronchus malacia underwent section and suture of the arterial ligament and posterior aortopexy (original approach) [

31]..

The right or left thoracotomy approach was used in the early years of the reported experience. Currently, ministernotomy is considered the preferred access route for OAA. With the patient in the supine position, the sternum is split through a 2-3 cm skin incision. Subtotal thymectomy is performed to create sufficient space in the anterior mediastinum for AA. The pericardium is opened, and two 4-0 Prolene sutures mounted on pledgets are usually placed on the aorta adventitial tunic for traction: one at the base of the IA origin, the other after the origin of the left carotid artery, in the concavity of the arch. Under endoscopic control, the sutures are first anchored to the sternum, transfixing it, and then tied on the anterior sternal table. The chest is closed with steel wires, and a 10 Fr pericardial drain is placed under suction. The pleurae are drained only in case of accidental opening. The procedure is carried out in just: 30-40 minutes, with the patients being extubated in the operating room if their weight is >10 kg, after a two-hour observation period if they weigh <10 kg. Average postoperative stay: 8 ± 7 days (range 4 – 50 days)

With zero mortality, the rate of major complications is very low: less than 6%; the average hospital stay is short: about a week.

Complications

Complete follow-up was performed on 109 patients, typically reviewing the patient 8-12 months later, with S/DVBS. CT with CM is reserved for still symptomatic cases or if SVBS shows persistent pulsatile extrinsic compression with residual TM.

Follow-up

109/131 patients (83%)

-

Average follow-up months: 29.75 ± 27.17 (range 3.3-130.66)

Clinical Outcome

- 52% asymptomatic

- 35% mildly symptomatic

- 13% still symptomatic

Endoscopic Outcome: 8-12 months after OAA

Increase in tracheal APD and disappearance of pulsatility: 85%

Unchanged diameters and pulsatility: 15%

Requiring second stage treatment with PT: 7 patients (6.4%)

87% of operated patients report clinical improvement, with 52% completely asymptomatic, 35% significantly improved; the VBS data are generally corresponding with clinical outcome. In cases of persistent TM, especially if DVBS shows a reduction in tracheal APD due to hypermobility of the membranous part, with no clinical improvement, our protocol includes PT via right thoracoscopy.

In conclusion: TM due to vascular compression by IA is not so rare, require a multidisciplinary approach by a dedicated TT, it is treatable with excellent results with OAA, ensuring excellent short- and long-term outcomes.

4.3. Thoracoscopic Anterior Aortopexy (TAA).

At Pediatric Surgery Division of Grande Ospedale Metropolitano, Milano, Italy (GOM Hospital), the experience with the surgical correction of TM using the TAA technique began in 2023. The first case was a male newborn, operated on at 2 days of life (GA 35+6, BW 1,490 g) for type III EA, who in the weeks following the surgery had repeated episodes of respiratory arrest requiring prompt resuscitation. VBS in spontaneous breathing and chest CT with CM showed severe TM without vascular rings or compressions. The indication for AA was based on literature reporting satisfactory efficacy rates of the procedure and its feasibility even with minimally invasive surgery (MIS) thoracoscopic technique [32.33]. The advantages of the thoracoscopic surgical approach over thoracotomy in infancy and childhood are demonstrated in terms of reduced postoperative pain, hospitalization and functional recovery times, long-term musculoskeletal complications, and cosmetic aspects [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Despite favorable experiences already reported [

39], recent studies have shown that some results of MIS, especially regarding recurrence, appear inferior to those of traditional surgery: OAA [

40]. Therefore, a systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines to clarify unclear aspects of this comparison. After selecting published works on PubMed based on specific inclusion criteria, 33 studies were selected, totaling 694 children operated on AA, 92% with OAA, 8% with MIS. Intraoperative complications and mortality were comparable between the two groups, while the recurrence rate was higher in the MIS group. Detailed analysis of the MIS approach revealed that the traditional technique was often not followed, not performing pericardiotomy and not using Teflon pledgets. Conversely, thoracoscopic experiences faithfully reproducing traditional steps, including pericardiotomy and the use of pledgets, showed results comparable to the traditional technique. Before establishing a definitive surgical approach, preoperative CT with CM is essential in determining the presence and thickness of the thymus, to evaluate the recoverable anterior space for traction after thymectomy. It also allows precise assessment of the extent of malacia and consequently choosing the most appropriate approach: AA vs. PT. Preoperative CT with CM also allows preoperative planning of the correct positioning of trans-sternal sutures to achieve the most effective traction.

In light of all these observations, it was decided to proceed with the MIS approach. Anesthetic management included the ipsilateral lung exclusion with an endobronchial blocker, Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) and Sedline monitoring. The cardiac surgeon and the table for urgent sternotomy conversion were always available in the operating room.

Surgical technique following steps at our center:

Preliminary VBS

Supine position with left flank and shoulder elevated by 30°

3 trocars: 3 mm for patients <1 year; 5 mm for children >1 year

Opening of the mediastinal pleura

Thymectomy (possibly total)

Isolation and lifting of the IA

Pericardiotomy

Non absorbable sutures with Dacron pledgets on the aorta and IA

Pericardial flap

Retrieval of trans sternal sutures with “Suture Passer”

Retrosternal scarification

Tension and closure of the sutures subcutaneously

No drainage

VBS post operative control

In the following 12 months, another 6 patients underwent TAA, with a median age of 3 years (6 months – 6 years) and a median weight of 15 kg (3 – 23 kg). All patients were awakened at the end of the procedure, without the need for intensive care admission. No patient had a thoracic drain placed. Feeding was resumed on the same day of the surgery, and discharge was relatively early (median 4th postoperative day, range 3-21 days). All showed clinical improvement: complete in 7, partial in 2, who subsequently underwent thoracoscopic surgical revision.

Literature data [

41] show that the general frequency of complications for AA is as follows:

Pneumothorax and/or pleural effusion: 3%

Pulmonary atelectasis: 2.5%

Pericardial effusion: 2%

Phrenic nerve paralysis: 1.3%

Hemorrhage: 1%

Recurrence: 1%

Death: 6%

In our series, we had only one case of bleeding from the IA, effectively managed through conversion to mini-sternotomy and completion of the procedure via open approach.

Based on the results of our preliminary experience, the MIS approach to AA appears feasible and safe, and it can therefore assume a role of choice, if some essential prerequisites are guaranteed: an adequate (certified) learning curve in pediatric thoracoscopy, dedicated anesthetists, a surgical team experienced in open and MIS thoracic surgery, a pediatric cardiac surgeon at the operating table, an accessory operating table for urgent sternotomy / thoracotomy conversion, and constant postoperative review of individual cases treated for critical analysis. These procedures should not be considered the prerogative of a single specialist, but of a multidisciplinary team that considers and treats the pediatric patients in their complexity, forming a true pediatric TT.

4.4. Posterior Tracheopexy (PT)

PT consists in fixing the posterior wall of the trachea (pars membranacea) to the anterior longitudinal ligament of the spine using sutures [

42]. DVBS allows for the indication of this procedure by documenting the hypermobility of the pars membranacea, which tends to almost completely occlude the tracheal lumen when the patient performs abdominal straining. Endoscopic images also indicate the extent of the posterior tracheal wall that shows hypermobility and thus the segment to be fixed to the spine.

In the period 2018-2024, 18 patient underwent PT at UOSD Thoracic and Airway Surgery, IRCCS G. Gaslini, Genoa. The “classic” surgical approach was right posterolateral thoracotomy, while sternotomy was preferred only in specific cases. Recently, the surgical procedure is increasingly performed using minimally invasive techniques: both Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) or Robotic-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (RATS) [

43,

44]. After mobilizing and laterally displacing the esophagus and thoracic duct, non-absorbable sutures are passed between the posterior membrane of the trachea, without crossing it, and the anterior longitudinal ligament of the spine under VBS control. In this way, the pars membranacea is fixed to the spine, resulting in a significant reduction in its mobility during expiration, limiting its protrusion into the tracheal lumen when the patient coughs, ensuring good preservation of the tracheal lumen with the disappearance of the biphasic cough.

Patient population

18 patients: 11 males, 7 females

average age: 10.50 ± 5.57 years (range: 3.33-22.89 years)

6 patients (33,3%): EA/TEF

1 patient: congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH).

6 patients (33.3%) had previously undergone AA,

1 patient: AA was performed simultaneously with the PT procedure.

average postoperative hospital stay for patients undergoing RATS was 8 ± 11 days (range: 3-16 days),

average follow-up of 10.23 ± 11.62 months (range: 1.41-40.62 months).

Detailed analysis of operative times revealed considerable variability between different approaches, with operative times ranging from 105 to 320 minutes and console times for RATS ranging from 75 to 215 minutes.

Intraoperative complications were recorded only in 1 patient, related to the AA performed simultaneously; no intraoperative complications occurred in patients treated with RATS. Postoperative complications affected 4 out of 18 patients (22%), of which 4 (28.6%) were treated with RATS, all with favorable outcomes with conservative treatment.

Postoperative complications in 4 out of 18 patients (22%),

The presence of comorbidities such as esophageal malformations and congenital heart diseases influenced both the choice of surgical approach and the postoperative outcomes, indicating the need for a personalized operative plan for each patient.

Clinical outcome, evaluated in 16 of the 18 patients,

complete resolution of respiratory symptoms in 50% of cases (8/16)

clinical improvement in 43.75% (7/16),

stability in 6.25% (1/16)

overall benefit in 93.75%

In conclusion: in cases of hypermobility of the pars membranacea, PT, especially with the use of minimally invasive techniques such as RATS, represents an effective solution with manageable complications and a high rate of clinical success.

Discussion. There was agreement in underlining the importance of the dynamic phase of bronchoscopy to differentiate patients who require artopexy or tracheopexy, interventions now well described in their procedural steps. In the absence of a TMS shared by the various centres, no unity of views emerged both on the degree of tracheomalacia that could justify the surgical indication, but also and above all on the timing of the operation. If the most severe cases of TM are generally treated surgically within the first 2 years of life and there are no other choices than surgical treatment, there was a lower concordance of indications regarding the vast majority of patients with TM but with less severe clinical symptoms. There was good consensus to indicate surgery in cases of TM associated with a diagnosis of protracted bacterial bronchitis, especially in cases with poor response to medical therapy. Surgical treatment of TM in these patients was judged to be important in hindering the progression to the development of bronchiectasis.

5. The Patient with Esophageal Atresia (EA) with / Without Tracheoesophageal Fistula (TEF)

5.1. The severe TM in patients with EA with / without TEF

EA, with or without TEF, is a congenital malformation characterized by the interruption of the continuity of the esophagus and an abnormal communication: a fistula, between the digestive and respiratory tracts. The morphogenesis of this anomaly occurs in the early stages of embryonic development (5th week of gestation), when the “foregut” forms the tracheoesophageal septum, which divides a dorsal portion (esophagus) from a ventral portion (trachea) [

45]. EA is often associated with other malformative anomalies: VACTERL, CHARGE syndrome, cardiac or genitourinary defects, and this association highlights a common genetic defect that alters the early stages of embryonic development [

46].

TEF occurs when there is an alteration in the physiological process of detachment of the airway from the foregut (the primitive esophagus), so that an abnormal communication between the esophagus and the trachea is maintained. The presence of TEF interferes with the regular differentiation of the tracheal wall, which at this level presents poorly formed cartilaginous arches, resulting in the most severe form of primary TM, because the malacia is intrinsic to the tracheal wall. This condition, typical of patients with TEF, is generally also associated with secondary or extrinsic TM, due to the compression from the IA, which greatly contributes to further worsening the patency of the esophageal lumen [

47]. TM in these patients is always present and with severe clinical complications, especially respiratory, as a vicious circle is established: the impairment of mucociliary clearance causes secretion stagnation, which favors persistent bacterial colonization with the development of PBB and pneumonia, leading to the final formation of bronchiectasis [

48,

49]. Patients with EA / TEF present therefore recurrent respiratory symptoms during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, which requires long term pulmonary follow-up.

EA, with or without TEF, has an incidence of about 1 in 3500/4500 live births, and five types are recognized [

50,

51]:

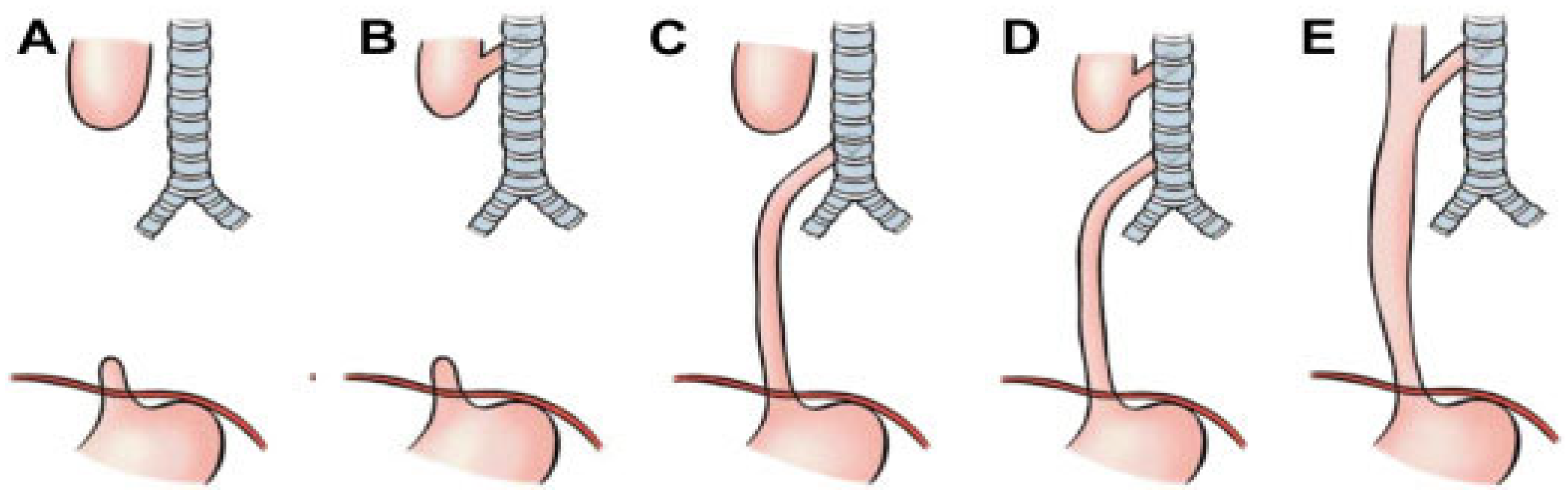

Figure 9.

The Gross classification of EA, based on the presence and location of TEF. Type A) EA without fistula; Type B): EA with TEF between the upper segment and the trachea; Type C) EA with TEF between the lower segment and the trachea (most common type: 84% of cases); Type D): EA with 2 TEFs connecting both segments to the trachea; Type E) TEF without EA (H-type fistula). Abbreviations. EA: Esophageal Atresia; TEF TracheoEsophageal Fistula.

Figure 9.

The Gross classification of EA, based on the presence and location of TEF. Type A) EA without fistula; Type B): EA with TEF between the upper segment and the trachea; Type C) EA with TEF between the lower segment and the trachea (most common type: 84% of cases); Type D): EA with 2 TEFs connecting both segments to the trachea; Type E) TEF without EA (H-type fistula). Abbreviations. EA: Esophageal Atresia; TEF TracheoEsophageal Fistula.

CLINICAL CASE: A baby born prematurely (32+4 weeks), the pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios. At birth: respiratory distress requiring CPAP support. Due to excessive salivation and difficulty advancing the nasogastric tube (NGT), an EG-EF was performed: it showed dilation of the proximal esophagus ending in a blind pouch, suggestive of EA, marked gaseous distension of the intestinal loops, indicative of a possible distal TEF, confirmed by bronchoscopy: EA type C. On the first day of life: ligation of the TEF and end-to-end esophageal anastomosis, with good results. In the first year of life: recurrent wheezing with frequent emergency room visits, one hospitalization for bronchiolitis requiring O2 support by High Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC), and persistent choking cough. Diagnostic tests were performed around 13 months of age.

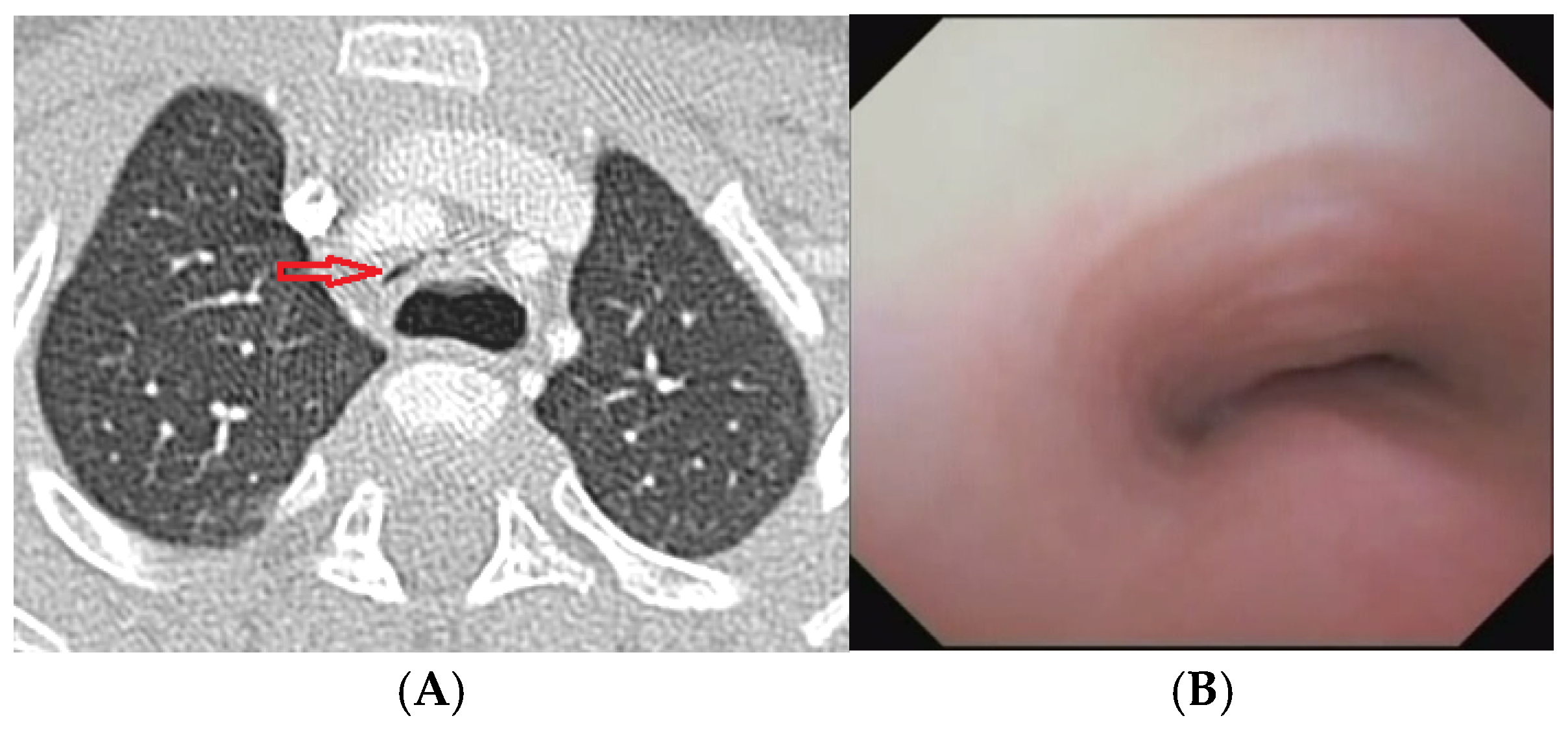

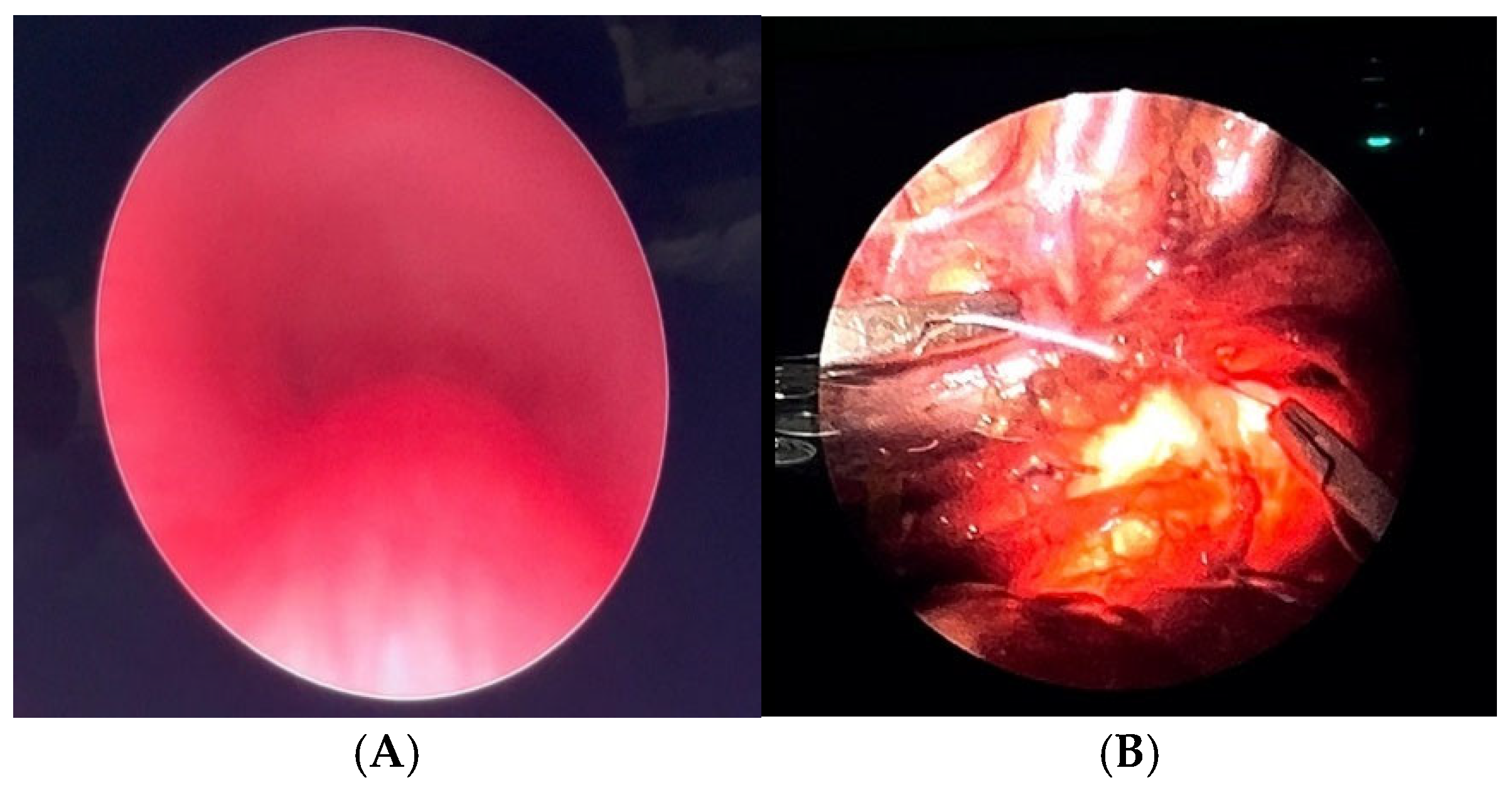

Figure 10.

A) Chest CT with CM: tracheal lumen completely collapsed (arrow) at the level of anterior compression by the IA and posteriorly by the dilated esophagus. B) SVBS: Endoscopic view of the trachea above the TEF: tracheal lumen almost completely collapsed even during quiet breathing. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; IA: Innominate Artery; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 10.

A) Chest CT with CM: tracheal lumen completely collapsed (arrow) at the level of anterior compression by the IA and posteriorly by the dilated esophagus. B) SVBS: Endoscopic view of the trachea above the TEF: tracheal lumen almost completely collapsed even during quiet breathing. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; IA: Innominate Artery; SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy.

At 16 months of age: OAA was performed via mini-sternotomy.

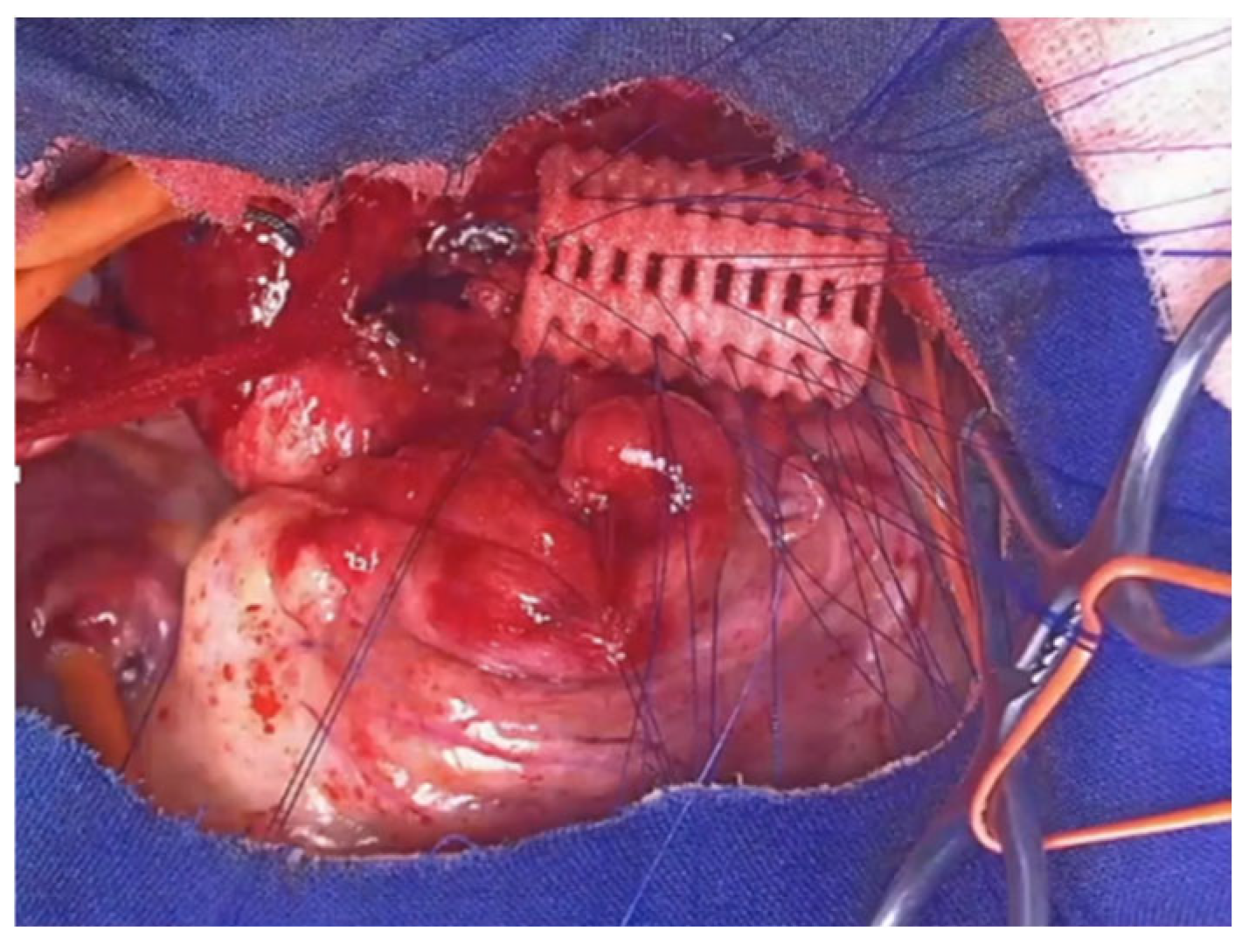

Figure 11.

Intraoperative VBS during OAA (after thymectomy): A) without traction on the aortic arch; B) significant increase in tracheal lumen while traction is exerted on the aortic arch. Abbreviations. VBV: Videobronchoscopy; OAA: Open Anterior aortopexy.

Figure 11.

Intraoperative VBS during OAA (after thymectomy): A) without traction on the aortic arch; B) significant increase in tracheal lumen while traction is exerted on the aortic arch. Abbreviations. VBV: Videobronchoscopy; OAA: Open Anterior aortopexy.

Despite the surgery, with favorable intraoperative control, the patient continued to experience recurrent cough, frequent need for antibiotic therapy cycles, repeated emergency room visits, and four hospitalizations for asthmatic bronchitis requiring HFNC.

At 3 and a half years old (2 years after the OAA) the patient was reevaluated.

Figure 12.

A) Chest CT with CM: although the IA appears well pulled anteriorly towards the sternum, a severe TM is persistent with lumen occlusion > 75%, also because a large esophagus compresses the tracheal lumen from behind. B) The SVBS confirms the persistence of TM, with a patent but severely deformed tracheal lumen even in quit breathing. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; IA: Innominate Artery; TM: Tracheo Malacia; SVBS: Static Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 12.

A) Chest CT with CM: although the IA appears well pulled anteriorly towards the sternum, a severe TM is persistent with lumen occlusion > 75%, also because a large esophagus compresses the tracheal lumen from behind. B) The SVBS confirms the persistence of TM, with a patent but severely deformed tracheal lumen even in quit breathing. Abbreviations. CT: Computed Tomography; CM: Contrast Medium; IA: Innominate Artery; TM: Tracheo Malacia; SVBS: Static Videobronchoscopy.

After collegial discussion within the TT: PT was planned, which involves the partial displacement of the esophagus laterally to the right. After the surgery, there was a prompt clinical improvement with the disappearance of the recurrent biphasic cough. Endoscopy 6 months after the PT (

Figure 13):

Figure 13.

A) SVBS: good patency of the tracheal lumen with almost complete restoration of the “bridge arch” structure of the wall; B, C) DVBS: the tracheal lumen maintains a good patency even when the patient is performing abdominal straining in an attempt to cough, thus causing an increase in intrathoracic pressure. Abbreviations. SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

Figure 13.

A) SVBS: good patency of the tracheal lumen with almost complete restoration of the “bridge arch” structure of the wall; B, C) DVBS: the tracheal lumen maintains a good patency even when the patient is performing abdominal straining in an attempt to cough, thus causing an increase in intrathoracic pressure. Abbreviations. SVBS Static Videobronchoscopy; DVBS Dynamic Videobronchoscopy.

In the clinical follow-up post PT (the patient is now 7 years old): no more hospitalizations or antibiotic cycles.

In conclusion: this clinical case highlights how, especially in patients with EA and TEF, AA may not be resolutive, making PT necessary to significantly improve the quality of life for patients.

5.2. Indications for Consensual PT During Esophageal Recanalization in EA Patients

The execution of PT requires lateral displacement of the esophagus, followed by fixing the membranous part of the trachea to the anterior longitudinal ligament. This surgical step is unnecessary during the correction of EA because the esophageal segments are far apart, leaving the posterior tracheal wall exposed. Despite this apparent technical advantage, until 2017, there was no literature describing the execution of PT concurrent with EA treatment. The first to describe the technique in 2018 were colleagues from Utrecht: 4 patients treated with thoracoscopic technique [

52], followed by the Aerodigestive Team from Boston with 18 patients, mostly treated with open technique. Utrecht later described an additional 14 patients, and Boston this year described 21 patients, some also thoracoscopically treated [

53]. China, with 17 patients, joined the two challengers [

54]. These reports demonstrate that this procedure reduces respiratory morbidity and TM complications without increasing the complexity of the intervention and avoids much riskier secondary procedures [

53,

54,

55]. However, the short follow-up, heterogeneity, and complexity of the case series, sometimes approached with different techniques and all numerically very limited, necessitate the execution of prospective multicenter randomized studies [

56,

57].

In my center: Pediatric Surgery Unit, Ospedale Filippo Del Ponte, Varese, Italy, the procedure for correcting EA begins with VBS in a spontaneously breathing child, followed by rigid bronchoscopy. The surgery is then performed using a thoracoscopic technique, first isolating the proximal esophageal segment, then the distal segment projecting into the trachea as TEF. This is ligated with a transfixing suture and sectioned; the upper esophageal segment is then mobilized, freed from the posterior tracheal wall, opened, and anastomosed with its distal counterpart, so that the esophagus is canalized:

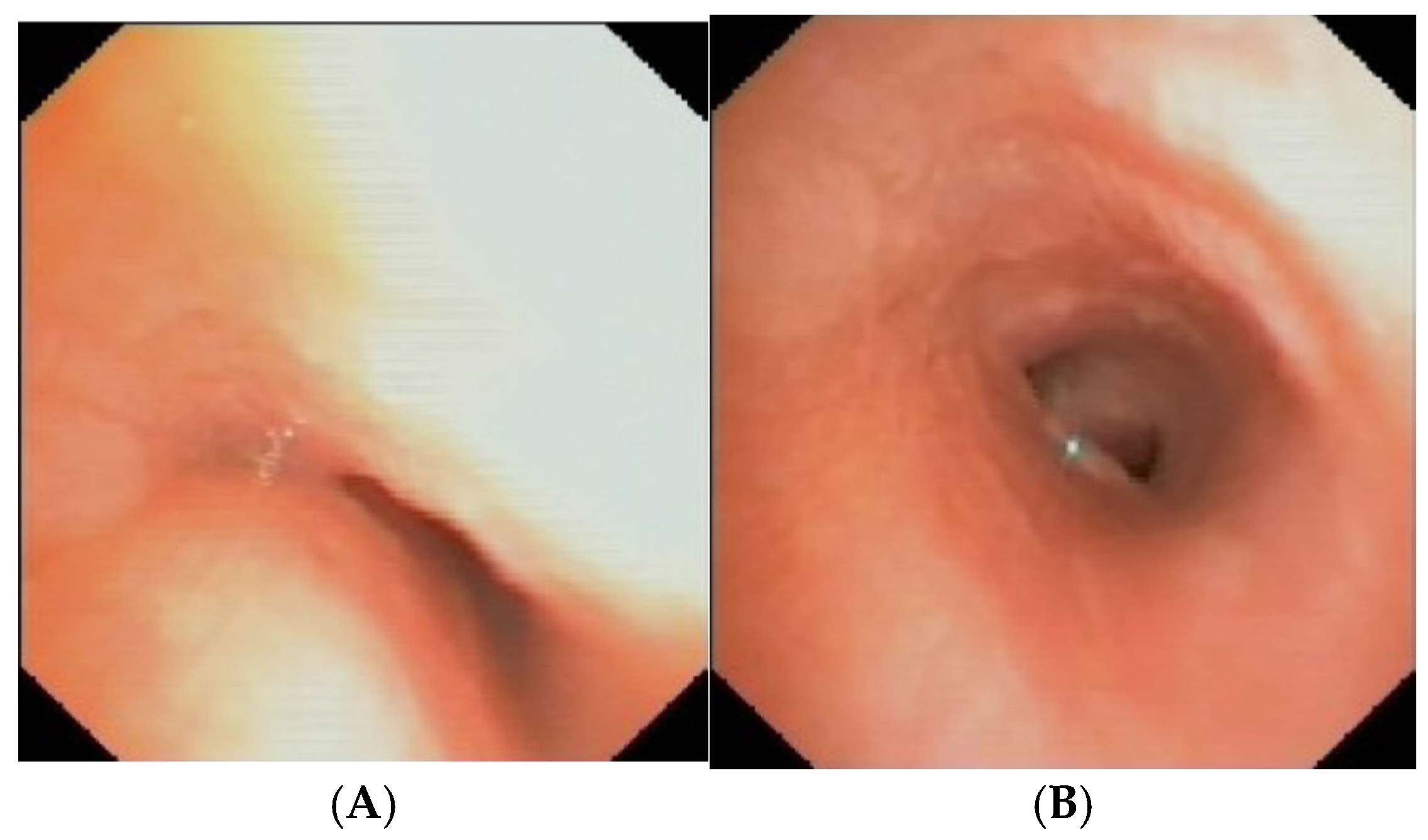

Figure 14.

To answer the question of whether there are indications for PT in patients with EA and TEF, each patient must be evaluated individually, as shown in the two cases in

Figure 15.

I encountered recently a patient with EA, and this is the preoperative image (of poor quality) of their trachea:

Figure 16 A. Well, I decided to proceed with the PT and therefore, before performing the esophago-esophageal anastomosis, I anchored the posterior wall of the trachea (under endoscopic guidance) to the anterior longitudinal ligament of spine: procedure performed without difficulty and without complications:

Figure 16 B.

In conclusion, it seems to me that mild forms of TM do not require any concurrent treatment, while severe forms definitely require concurrent TP. Therefore, each patient must be carefully evaluated, and it is essential to always perform preoperative VBS. Additionally, having a team experienced in neonatal, MIS is crucial to minimize functional and aesthetic outcomes.

5.3. Endoscopic Treatment of Recurrent/Persistent TEF

Before the 1980s, the treatment of choice for recurrent or persistent TEF was classic open surgery. In the early 1980s, the first attempts at endoscopic obliteration of recurrent/persistent TEF after surgical closure were made, mainly due to the high complication rates following classic surgery [

58]. Over the years, numerous strategies have been employed to achieve endoscopic closure of TEF; from the use of diathermocoagulation, to simple mucosal denudation, to the abrasion of the edges plus the use of sealing agents, and even the placement of tracheal stents [

59,

60].

In our center: Otolaryngology Unit, IRCCS G. Gaslini Genova, Itay, endoscopic closure of TEF has been practiced since 2017, for a total of 7 patients (2 of whom are still in treatment). The technique used is rigid bronchoscopy, through which we first abrade the edges of the fistula with a CO2 laser fiber, followed by local applications of 50% Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA). Patient age range: 4 months – 4 years with a median of 8 months. Weight of treated patients: 4.2 – 7.8 kg. Each endoscopic session involves, after the laser, 2 applications of TCA, with an average total contact time with the mucosa of about 100 seconds. The average number of sessions required for closure has been 3.6. Closure has been achieved so far in 5 out of 7 cases (71%); the 5th and 6th cases are still in treatment: 3 and 4 applications of TCA have been performed so far, respectively. No significant post-procedure complications have been reported. In conclusion:

Endoscopic treatment for the closure of recurrent TEF is reliable and has few complications.

The method with laser edge abrasion, followed by 2 local applications of TCA, has proven to be the most effective. The application time of TCA to the abraded edges of the TEF is variable and operator-dependent; we maintain a total time (two applications) of about 100 seconds.

Treatment limitations include patient weight (not less than 4 kg) and the possibility to use a rigid bronchoscope of at least 3.5 mm diameter.

Repeated applications (an average of 4 in the literature) are necessary to achieve closure; we wait about 20 days between two successive sessions.

So far, no limit has been set beyond which the treatment is considered ineffective.

Discussion. There was unanimous consensus in judging EA patients with the most severe degrees of TM, in which tracheoscopy should be performed early, if possible simultaneously with surgical recanalization of the esophageal lumen. The consensual execution of posterior tracheopexy during esophageal recanalization is currently a practice that is still not very widespread among pediatric surgeons. To our knowledge, it is currently practiced in Italy only in few pediatric centers in selected cases of AE.

6. Follow-Up of the Patient with TM

Given the varying severity of clinical presentations and the heterogeneity of associated clinical conditions, the management of follow-up for patients with TM and TBM should aim for a personalized approach. As demonstrated by the ERS statement [

1], numerous syndromes can be associated with the presence of TBM, which can represent either the primary clinical condition or a minor part of the patient’s spectrum of comorbidities (mostly neurological or cardiological).

Patients with TM require careful follow-up, especially for the recurrence of respiratory symptoms present from the early years of life: recurrent lower respiratory tract infections, wheezing, recur-rent bronchitis, and pneumonia. These complications are particularly frequent in patients with EA / TEF, representing the most severe cases of TM: both primary and secondary malacia, due to the concomitant compressive effect on the tracheal lumen by the IA [

61,

62,

63]. Regarding patients with TM associated with EA and TEF, the ERNICA consensus statement [

64] emphasizes the need for long-term longitudinal monitoring, based on a multidisciplinary program (surgical, gastroenterological and nutritional, pulmonological, and otorhinolaryngological) but managed by a single coordinating specialist, who can also decide on performing invasive procedures under sedation (e.g., esophagogastroduodenoscopy and VBS).

The ERNICA recommendations suggest that the longitudinal monitoring of these patients should start from hospital discharge and continue through the transition age and possibly into adulthood. Attention should be particularly focused not only on the proper management of recurrent infections but also on growth and weight gain, and the prevention of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is particularly frequent in patients operated on for TEF. Additionally, it is mandatory to have a supportive and informative role from the pediatrician following the patient at home, both towards the family and the child affected by TBM.

The recurrence of respiratory symptoms is also a frequent issue in patients with intrathoracic vascular anomalies (complete or incomplete vascular rings), where the abnormal vessel causes a reduction in the tracheal lumen and often TM due to extrinsic compression. Although there is a clear surgical indication for some of these conditions, surgical treatment may not be followed by the immediate resolution of associated respiratory and/or digestive symptoms, as the TM takes time to improve. The persistence of symptoms up to a year after the correction of the anatomical anomaly is widely reported in the literature, especially in children with a double aortic arch, compared to children with a complete vascular ring from the right aortic arch [

65].

Objectives of follow-up for patients with TM:

Improvement of airway patency,

Enhancement of mucociliary clearance,

Prevention of recurrent respiratory infections and PBB,

Reduction of the risk of lung damage,

Improvement of long-term respiratory prognosis.

Diagnostic tools useful in respiratory follow-up, especially when periodic patient evaluation reveals a worsening of the respiratory condition, include:

VBS with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL),

Chest CT with or without CM,

PFT: baseline and post-salbutamol,

Exercise tests (walk test/cardiopulmonary exercise test),

Nocturnal oximetry,

Microbiological examination of sputum and/or BAL.

S/DVBS is certainly the gold standard for studying TBM, and during the examination, BAL can also be performed to check if the patient is colonized by pathogenic germs in the deep lung. Chest CT with CM, and particularly Dynamic CT, has proven to be a valid alternative to VBS, as it has good sensitivity and specificity in detecting and defining TBM [

65]. Considering the rapid execution and the lack of need for deep sedation, it can be considered in that group of fragile or clinically unstable patients, where general sedation is contraindicated.

Baseline PFT may show a particular morphology of the expiratory phase of the F/VC with deflection/tendency to plateau in the expiratory phase not modifiable with bronchodilation, so the test can be used to assess the severity of TM in these patients [

66]. The walk test or cardiopulmonary exercise test allows for objectifying exertional dyspnea, detecting any variations in Saturation O2 values during imposed activity, and thus estimating functional capacity. Nocturnal oximetry monitoring in patients with TM is indicated if obstructive apnea events secondary to tracheal wall collapse are suspected, or with comorbidities that may cause apneic episodes. Due to the inefficient mucociliary clearance of the malacic tract, children with TM often experience infectious episodes of the lower respiratory tract: in such circumstances, microbiological monitoring of respiratory secretions (sputum or BAL) can be useful for managing a possible subsequent episode of respiratory exacerbation.

In light of the findings during the diagnostic process in the follow-up, the pulmonologist should focus the medical management of patients with TM on managing bronchial hyperreactivity and infectious episodes. The cornerstones of therapy are therefore: a) Inhaled steroid therapy as maintenance therapy in patients with bronchial hyperreactivity; b) Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy to be started early in the presence of symptoms suggestive of respiratory exacerbation involving the lower airways. Currently, there are no studies on the usefulness of azithromycin prophylaxis in patients with TM: the indication for its use is extrapolated from data on patients with non-Cistic Fibrosis bronchiectasis and frequent respiratory exacerbations. C) Respiratory physiotherapy, with devices promoting the mobilization of respiratory secretions (PEP mask or similar devices); d) Immunoprophylaxis: Respiratory Sincitial Virus vaccination in the first year of life in patients with tracheobronchial tree anomalies; annual influenza vaccination [

67].

In conclusion, in the absence of precise guidelines regarding the follow-up of patients with TBM, the pulmonologist should personalize the diagnostic-therapeutic pathway, based on the reported symptoms and clinical findings, especially in cases with other comorbidities, with a multidisciplinary approach to the patient.

Discussion. The follow-up of patients with TM, whether treated conservatively or surgically, was judged by all participants to be essential: the patients must be followed over time, even after a surgical procedure with good clinical outcomes. It was emphasized that follow-up must always be multi-specialist, and possibly carried out at the center where the patient underwent the entire diagnostic and therapeutic process

7. Respiratory Assistance in Patients with TM

7.1. The Tracheal Splint

As early as 1968, Vasko et al. described the treatment of TBM by external application of specially shaped costal cartilage [

68]. In subsequent decades, synthetic material devices were introduced, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, when Filler et al. [

69] used supports made of silicone elastomers (Silastic), reinforced with polypropylene mesh (Marlex). Later, in 1997, Hagl et al. used devices made of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). In the last 10 years, there has been an increase in studies on the use of external support devices for the tracheobronchial wall or splints; in 2017, Ando et al. published a series of 98 patients with TBM who underwent placement of PTFE tracheobronchial splints, with good results: low morbidity and mortality [

70].

In 2015 and 2019, the Green group presented their experience with the implantation of tracheobronchial splints, produced using 3D printing, made of polycaprolactone (96%) and hydroxyapatite (4%) [

71,

72]. To prepare the printing of the devices, patients underwent chest DCT and VBS to confirm diagnosis, position, and extent of TBM. From the CT images and three-dimensional reconstructions, the length and diameter of the malacic segment were calculated for each patient, from which the 3D printing of the splint was performed using a laser sintering machine (96% polycaprolactone/4% hydroxyapatite).

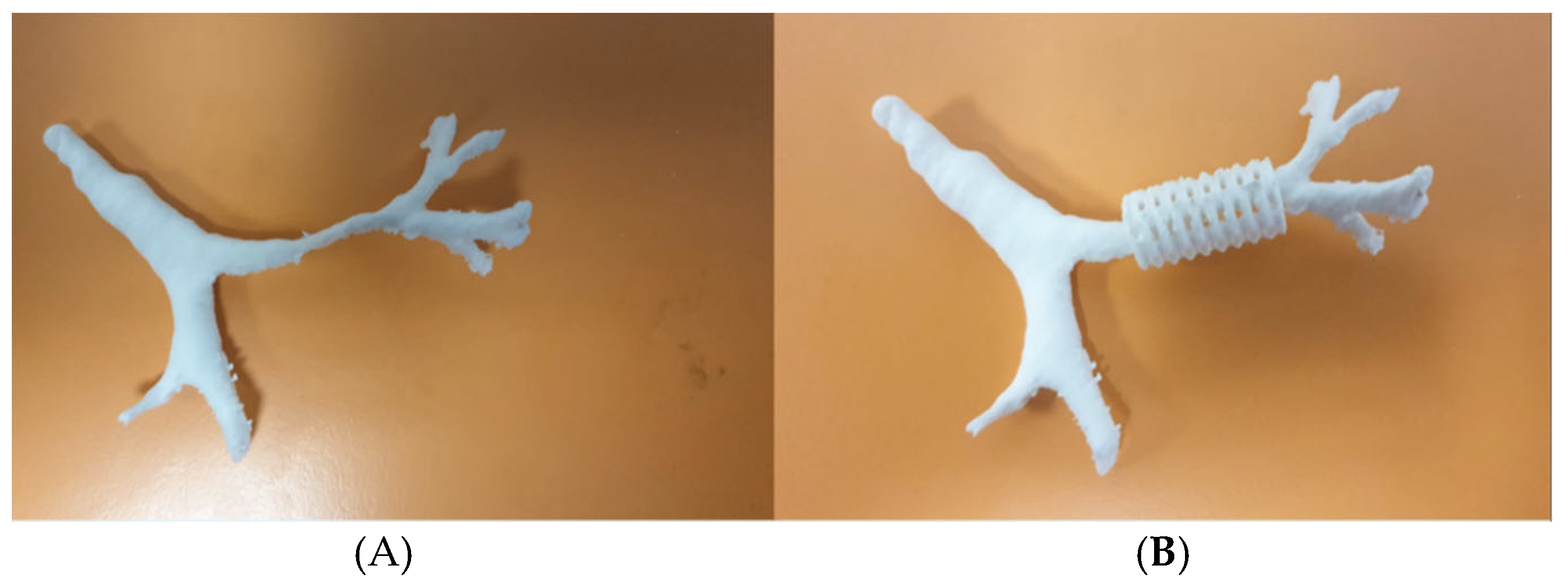

Figure 17.

A) a three-dimensional airway model; B) Example of bronchial splint in polycaprolactone and hydroxyapatite on the airway model.

Figure 17.

A) a three-dimensional airway model; B) Example of bronchial splint in polycaprolactone and hydroxyapatite on the airway model.

Our recent experience at the Bambin Gesù Pediatric Hospital in Rome, with 3 patients (1 tracheal splint and 2 bronchial splints), is based on the aforementioned indications from Green’s work for the production of the devices [

71,

72,

73,

74]. For each treated case, authorization was obtained from our ethics committee for “compassionate use” and from the Ministry of Health for the suitability of the device. Each device undergoes static and dynamic mechanical tests (compression, torsion, and breakage) to verify its elastic, resistance, and failure characteristics. The devices are sterilized using ethylene oxide. The composition of the splint: 96% polycaprolactone, 4% hydroxyapatite, allows the maintenance of initial properties without significant degradation in the first year of implantation, with an overall device duration of 2 to 3 years. The placement of the splint occurs after isolating the anterior and lateral portions of the trachea and/or main bronchi, where the malacic segments have been confirmed.

Figure 18.

After 3D printing of the custom made splint, prolene sutures are placed on the tracheal or bronchial wall of the malacic segment. The sutures then pass through the splint slots, so that it is fixed to the wall, suspending the trachea or bronchus within it. The correct positioning of the splint and the achieved patency of the malacic segment are verified by intraoperative VBS.

Figure 18.

After 3D printing of the custom made splint, prolene sutures are placed on the tracheal or bronchial wall of the malacic segment. The sutures then pass through the splint slots, so that it is fixed to the wall, suspending the trachea or bronchus within it. The correct positioning of the splint and the achieved patency of the malacic segment are verified by intraoperative VBS.

The two patients with bronchial splints were simultaneously subjected to cardiac surgery with the French maneuver (moving the pulmonary artery confluence anterior to the ascending aorta and reconstructing the right pulmonary artery), with evidence of good long-term results both clinically and in subsequent radiological and endoscopic controls.

The patient who underwent tracheal splint placement also showed a significant increase in respiratory space in radiological and endoscopic control with initial respiratory stabilization. However, six months after the procedure, the general condition of the patient: dystonic-dyskinetic tetraparesis, epileptic encephalopathy and progressive pontine impairment, necessitated the restoration of long-term ventilatory support with the creation of a tracheostomy.

In conclusion: the main advantage of treating TBM with bioresorbable splints is the reduction of endoluminal complications typical of endotracheal and endobronchial stents (dislocation, granulation, reduced mucosal clearance, obstruction), allowing good radial expansion and resistance to external compression. Splint placement is generally performed during other cardiovascular surgery interventions, given the need for a sternotomy approach. Polycaprolactone and hydroxyapatite devices also have a long duration, ensuring long-term stabilization with good adaptation to airway growth. The preliminary results reported in the literature and in our center are encouraging, but the indication is currently for “compassionate use,” still reserved for severe TBM cases.

7.2. The Tracheal Stent

Once the TM has been classified as primary/secondary and its severity, the most appropriate therapy can be proposed to the parents, choosing from the possible current therapeutic options [

1]:

AA, in case of extrinsic vascular compression

PT, in case of hypermobility of the pars mebranacea

positioning of external tracheal splint

positioning of endoluminal stents, which we will talk about.

The placement of a stent takes place in the operating/endoscopy room under double vision: endoscopic and radiological (the stents are radiopaque, either by their structure or thanks to the presence of metal markers), to achieve the best possible precision in the tracheal positioning of the device, although fine position adjustments are made with optical forceps [

75,

76].

The main complications related to the placement of a stent in the trachea are:

- Dislocation: to prevent it, it is recommended to place a stent with a diameter about 2 mm larger than the trachea’s diameter.