Introduction

Bronchiolitis is the leading cause of hospital admissions in children, yet effective therapies and diagnostics beyond supportive care remain controversial [

1]. Despite the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines discouraging routine chest X-rays (CXRs) [

2], they are still used in 83–98% of PICU cases, often without altering clinical management [

3].

Routine CXRs in bronchiolitis reveal non-specific findings, such as atelectasis or infiltrates, which are frequently misinterpreted as bacterial pneumonia. These misinterpretations, in addition to radiation exposure, can lead to overtreatment with increased antibiotic use, contributing to higher healthcare costs and patient risks [

4]. The economic burden of bronchiolitis is significant, costing the U.S. healthcare system

$1.73 billion annually [

5]. Evidence suggests that reducing unnecessary radiography can lower costs without compromising the diagnostic accuracy of bacterial pneumonia [

6].

While the AAP's "less is more" approach effectively manages non-severe bronchiolitis, it does acknowledge disease heterogeneity, stating that "initial radiography should be reserved for cases in which respiratory effort is severe enough to warrant ICU admission" [

2]. However, current evidence-based protocols primarily address non-critically ill children, leading to variability in imaging practices in those admitted to the ICU.

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of routine CXRs in critical bronchiolitis, specifically focusing on ICU length of stay (ICU-LOS) and the level of respiratory support (ICU-LRS). Critical bronchiolitis was defined as patients diagnosed with viral bronchiolitis requiring ICU-LRS, including high-flow nasal cannula therapy (HFNC), non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV), or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). As a marker of illness severity, the study utilized the Critical Bronchiolitis Score (CBS), a validated tool that predicts ICU-LRS and ICU-LOS [

7].

Materials and Methods

Study Overview

This was a single-center retrospective cohort study conducted at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital. We included children aged 0–36 months admitted to the PICU, step-down ICU (SDICU), or pediatric cardiac ICU (PCTICU) with a clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis requiring ICU-LRS. We extended the age cut-off to 36 months to reflect real-world practice, as physicians often treated children just over 24 months as bronchiolitis, and excluding them risked introducing selection bias by omitting clinically similar cases.

The study period spanned from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022. Children with a history of cardiac surgery within seven days, readmission to PICU during the same hospitalization, tracheostomy dependence, and age greater than 3 years were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital (IRB #5220357).

Outcome Measure

The primary outcome measures were ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS. Patients were divided into two groups for analysis: those who received CXRs and those who did not. CXRs were counted as received if they occurred in the ER prior or during the ICU admission. Actual ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS were measured for patients admitted to the PICU, SDICU, and PCTICU. The actual lengths of stay and respiratory support were compared to predicted lengths.

The predicted ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS were calculated for both the CXR and no-CXR groups using the Critical Bronchiolitis Score (CBS), a validated metric for illness severity in bronchiolitis [

7]. The difference between actual and predicted values for ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS was then analyzed to compare the effect on outcomes between the two groups.

Data Collection

Variables collected from each patient included demographic data, past medical history, past surgical history, home-oxygen use, day-of-illness on presentation, month and year of presentation, presence of viral infection, ICU-LOS, hospital LOS, type and duration of respiratory support, CXR status, and use of antibiotics, bronchodilators, steroids, or nebulized hypertonic saline. Data was also collected for additional imaging modalities, including lung ultrasound, chest computed tomography (CT), and echocardiography, with associated relevant findings.

To evaluate the CXR findings, a scoring system was used. Each CXR was assessed for actionable findings (defined as the presence of consolidation, pneumothorax, pleural effusion), questionably actionable findings (such as atelectasis), or expected findings (increased perihilar markings). For patients who received multiple CXRs, the subsequent images were scored based on whether they were unchanged from the previous one, represented a new actionable finding, or if the finding was unrelated to bronchiolitis.

For the CBS calculation, variables collected 12 hours after hospital admission included the highest respiratory rate (RR), highest heart rate (HR), highest temperature, lowest serum bicarbonate, lowest pH with the highest pCO₂ ratio, and the worst Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. For intubated patients, the score also incorporated the highest blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and lowest systolic blood pressure (SBP) values.

A list of collected variables is in Table # in the online supplement [Table at the end of the manuscript].

Statistical Analysis

A target sample size of 97 patients was determined a priori to achieve a power of 0.8, with an effect size of 2 days and an alpha level of 0.05. To evaluate differences in demographics and assess the association of antibiotic usage and CXRs between groups, a chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables.

Given the non-parametric nature and non-normal distribution of the variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze differences between CXR utilization and ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS. Additionally, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied to compare differences between actual and predicted values (actual minus predicted) for ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS between the two groups. This analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.3.0 (461) (GraphPad Software, LLC, 2024;

www.graphpad.com).

Results

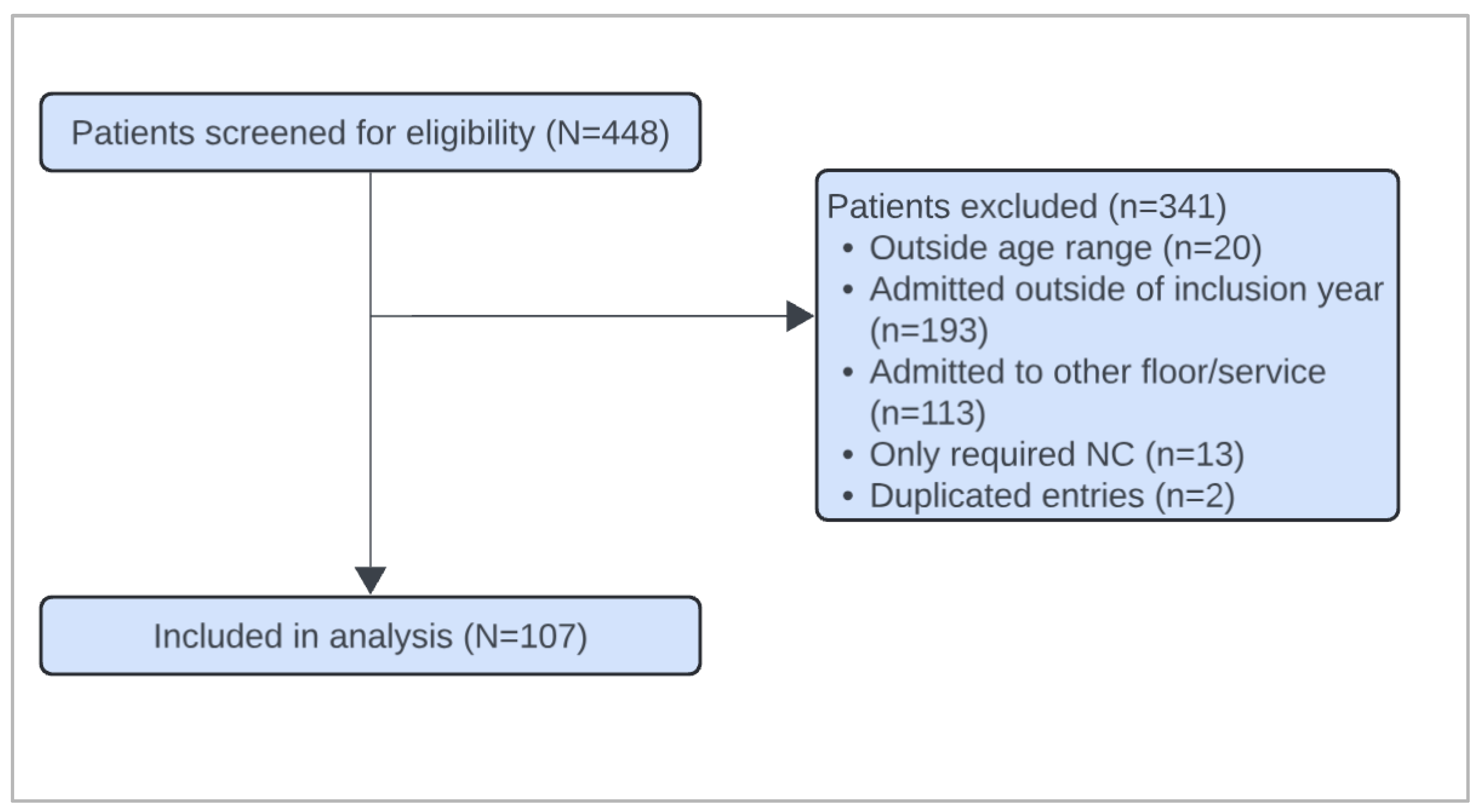

Of the 448 patients screened, 107 met inclusion criteria [

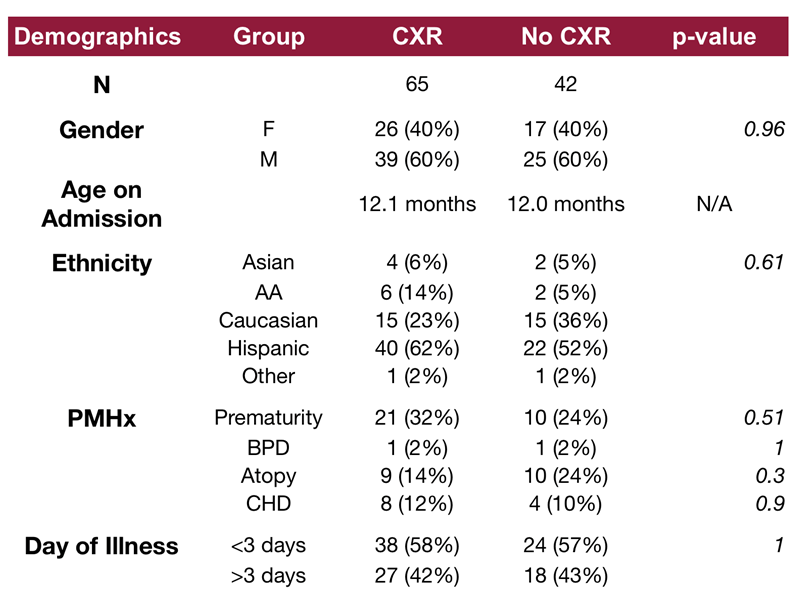

Figure 1]. The demographic characteristics of the cohorts are listed in

Table 1. No significant differences were identified in baseline demographics between the groups. Of the 107 patients included in the study, 65 patients (61%) underwent CXR during their admission, while 42 patients (39%) did not receive a CXR. All three patients who were intubated received a CXR.

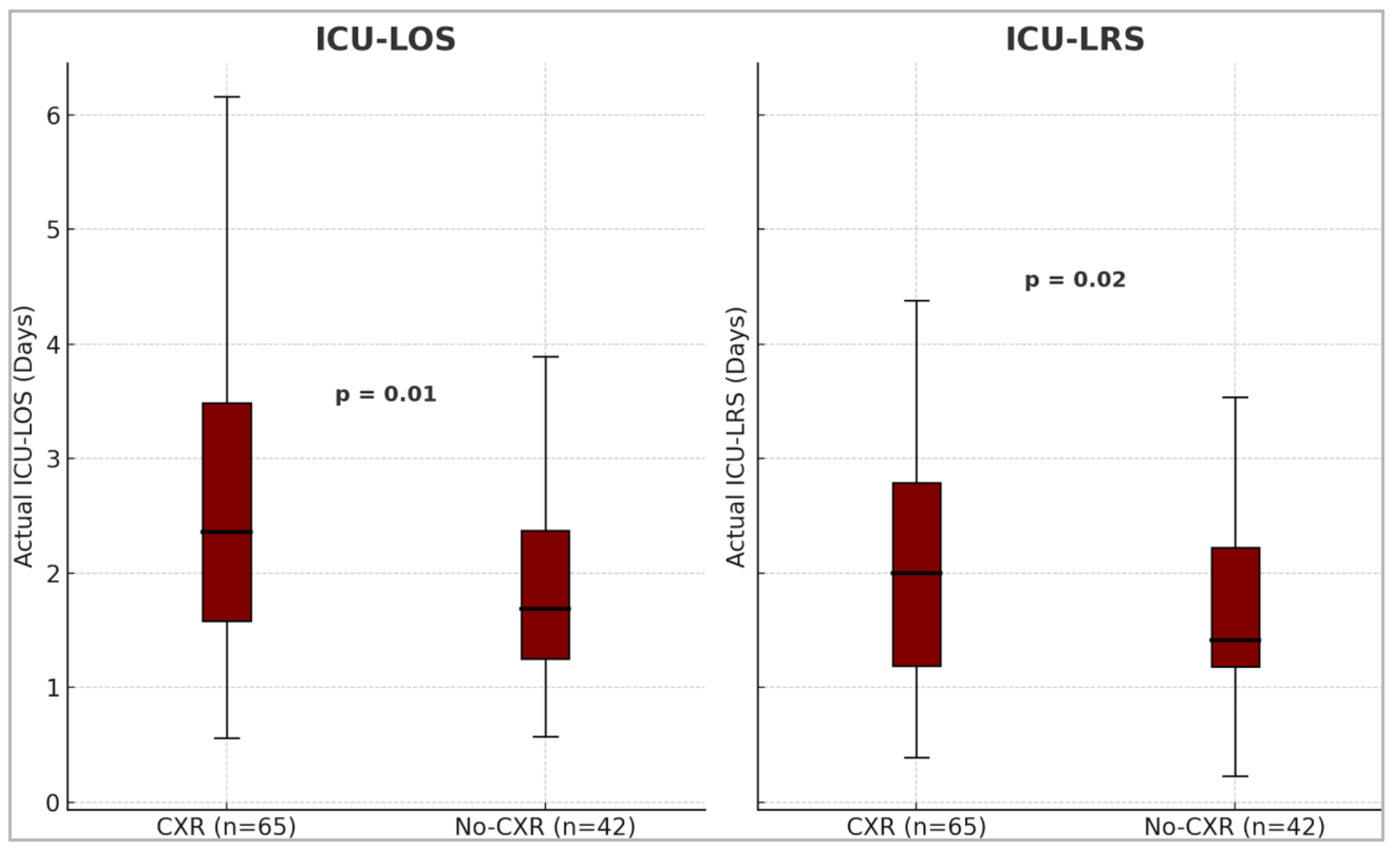

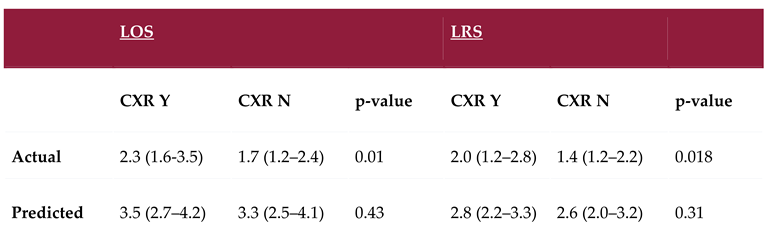

Patients in the no-CXR group had a significantly shorter observed median ICU-LOS of 1.7 days (IQR: 1.3 to 2.4) compared to 2.4 days (IQR: 1.6 to 3.5) in the CXR group (p = 0.01). Similarly, the observed ICU-LRS was significantly shorter in the no-CXR group, 1.4 days (IQR: 1.2 to 2.2), compared to 2.0 days (IQR: 1.2 to 2.8) in the CXR group (p = 0.02) [

Figure 2].

There was no significant difference in illness severity between the two groups. The predicted median ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS was 3.5 days (IQR: 2.7 to 4.2) and 2.8 days (IQR: 2.2 to 3.3) respectively in the CXR group vs 3.3 days (IQR: 2.5 to 4.1) and 2.6 days (IQR: 2.0 to 3.2) in the no-CXR group (p = 0.43 and p=0.31).

Figure 2.

Box and whisker plots showing the difference in median observed ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS between the two groups. The median ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS were significantly shorter in the no-CXR group. ICU= Intensive Care Unit, LOS= Length of stay, LRS= Level of Respiratory Support, CXR= Chest X-Ray.

Figure 2.

Box and whisker plots showing the difference in median observed ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS between the two groups. The median ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS were significantly shorter in the no-CXR group. ICU= Intensive Care Unit, LOS= Length of stay, LRS= Level of Respiratory Support, CXR= Chest X-Ray.

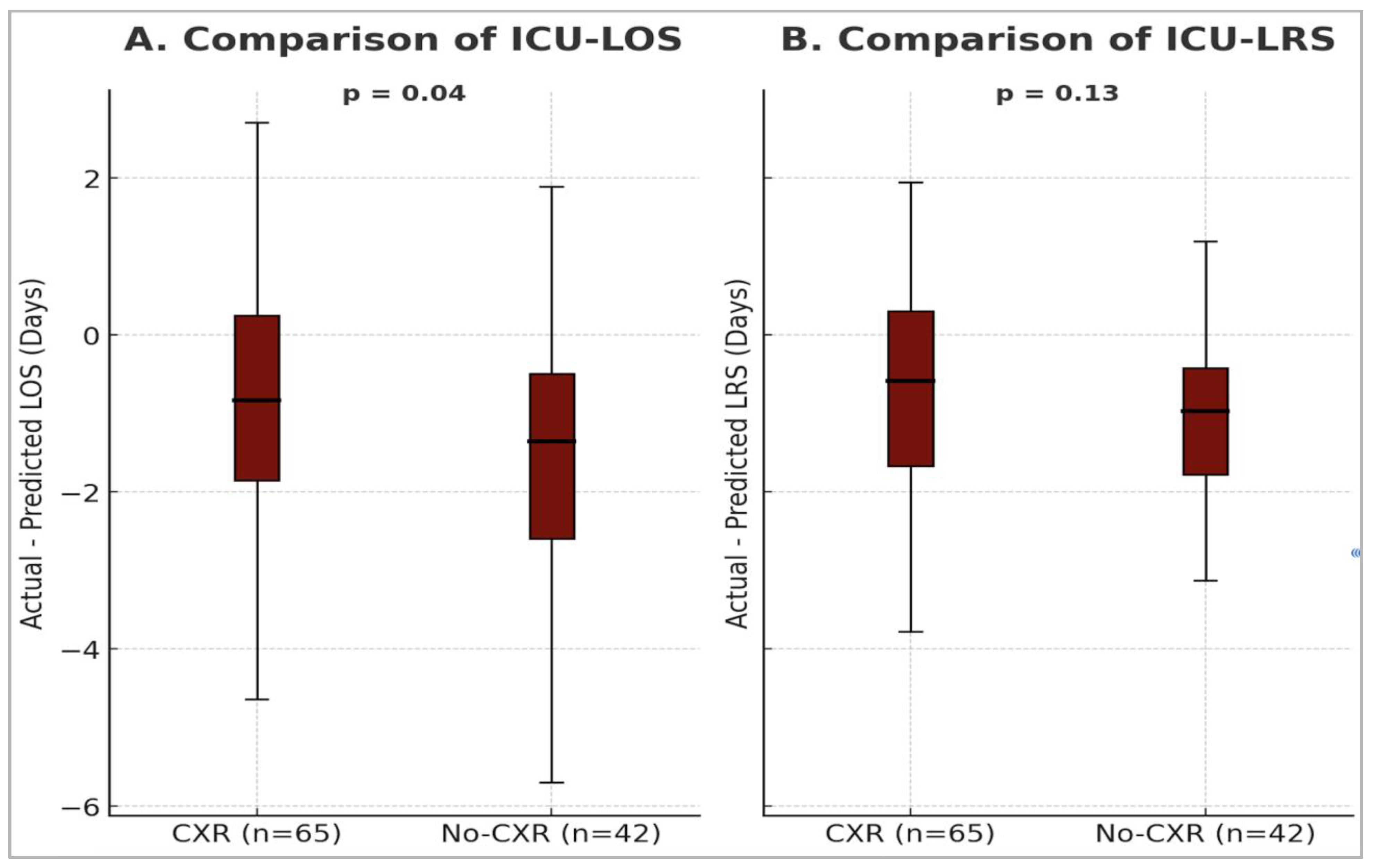

Actual ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS were significantly shorter than predicted values in both the CXR and no-CXR groups [

Table 2]. The median difference in ICU-LOS (actual minus predicted) was significantly shorter in the no-CXR group: –1.4 (IQR: –2.6 to –0.5) days, compared to –0.8 (IQR: –1.9 to 0.3) days in the CXR group (p = 0.04) [

Figure 3]. In contrast, the difference in median ICU-LRS between the two groups was not statistically significant: –0.6 (IQR: –1.7 to 0.3) days for the CXR group vs. –1.1 (IQR: –1.8 to –0.4) days for the no-CXR group (p = 0.13) [

Figure 3].

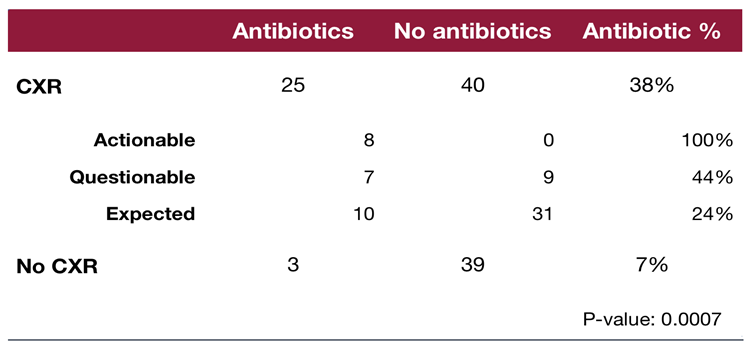

Among those who received a CXR, 8 patients (12%) had actionable findings, 16 patients (25%) had possibly actionable findings, and 41 patients (63%) had expected findings. All patients with definitely actionable findings received antibiotics (8/8), 44% (7/16) of those with possibly actionable findings, and 24% (10/41) of those with expected bronchiolitis findings. Overall, antibiotic use was 38% (25/65) in the CXR group and 7% (3/42) in the no-CXR group. This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0007), indicating an association with CXRs and higher antibiotic use [

Table 3].

Comparison of antibiotic administration in patients who received a chest radiograph CXR upon admission versus those who did not. A significantly higher proportion of patients in the CXR group received antibiotics compared to those in the no-CXR group with those with actionable and questionably actionable findings receiving higher rates of antibiotics. CXR= Chest X-Ray

Of the 65 patients who received an initial CXR, 15 (23%) underwent repeat imaging. In most of these cases (87%), the repeat CXR confirmed the initial interpretation—whether the findings were significant, possibly significant, or non-significant. Only 2 patients (13%) were reclassified as having a significant finding on repeat imaging after an initially non-significant result.

A total of seven patients underwent echocardiography. In the CXR group, 6 patients had echocardiograms, which revealed stable CHD or normal findings. In the no-CXR group, one patient underwent echocardiography, which revealed stable CHD. No patients in either group had a chest CT or lung ultrasound obtained.

Discussion

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first study conducted in the ICU setting to evaluate the impact of routine CXR use on PICU outcomes. Our findings demonstrate that obtaining a CXR on admission was associated with significantly longer ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS, despite similar illness severity.

Interestingly, CXRs were performed in 61% of our cohort, yet only 12% of those receiving CXR had clearly actionable findings such as consolidation, effusion, or pneumothorax. An additional 25% had questionably actionable findings (atelectasis), which are common in viral illnesses and often misinterpreted as bacterial pneumonia. Consistent with prior literature, these nonspecific findings may have influenced increased antibiotic use: 100% of patients with actionable CXRs received antibiotics, as did 43% with possibly actionable findings. Overall, antibiotic administration was five times higher in the CXR group than in those not imaged (38% vs. 7%). This difference was statistically significant, aligning with prior studies suggesting CXRs may drive unnecessary antibiotic exposure without improving outcomes [

8,

9,

10].

Although the predicted ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS were similar between groups, the observed durations were significantly shorter in the no-CXR group. This difference warrants careful interpretation and may stem from several mechanisms. First, misinterpreting radiographic findings as a bacterial infection may delay the de-escalation of respiratory support or prolong pulmonary clearance treatments [

11]. Second, providers may perceive radiographic abnormalities as indicators of more severe illness, prompting a more conservative approach and addition of antibiotics. Third, CXR use may reflect physician bias toward diagnostic thoroughness, even in the absence of clinical deterioration. This introduces the potential for reverse causality, wherein longer ICU stays and more complex courses prompted CXR use, rather than resulting from it. Alternatively, patients with prolonged ICU courses may represent a distinct subgroup—potentially with a differential or overlapping diagnosis—that would not be fully captured by the CBS.

The relative differences between actual and predicted ICU-LOS remained greater in the no-CXR group, further reinforcing the observed association between CXR use and longer ICU stays. The median ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS in our cohort were significantly shorter than CBS predictions for both groups. This may be attributed to variations in institutional ICU-admission criteria, management strategies, or regional differences in disease presentation.

Although CXRs revealed actionable findings in a minority of cases (12%), the low yield underscores the importance of more targeted imaging approaches. Prior studies have noted that hypoxia is a modest predictor of radiographic abnormalities [

12], but widespread CXR use—even in non-intubated patients—remains common in PICUs [

3]. Importantly, routine imaging not only contributes to cumulative radiation exposure in young children but also adds to healthcare costs without clear benefit in most cases [

6]. Future work should focus on identifying subpopulations (e.g., sudden unexplained deterioration, persistent hypoxemia, or lack of clinical improvement) in whom CXRs may alter management.

Our findings reinforce the AAP's recommendation against routine imaging in bronchiolitis and extend that guidance to the ICU population, a group historically excluded from such guidelines [

2,

13,

14,

15]. Quality improvement initiatives have primarily focused on emergency and general pediatric settings [

16,

17]; our data support extending these efforts to critical care environments.

This study is limited by its single-center, retrospective design. While the CBS standardizes illness severity, it may not entirely capture the nuances of clinical decision-making. The CBS also does not include some known variables associated with illness severity (prematurity, work of breathing, multiple viruses, etc.). Still, it is a more appropriate way to adjust for disease severity in low-mortality illnesses, such as bronchiolitis. We also did not assess the timing of management strategies following CXR findings, such as the initiation of antibiotics, additional respiratory therapies, or escalation of respiratory support. These aspects warrant investigation in future prospective studies.

Conclusions

Routine CXRs are common in critically ill bronchiolitis patients and may be associated with longer ICU-LOS and ICU-LRS despite similar illness severity. Future research should focus on identifying criteria for targeted imaging in subsets of bronchiolitis patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S., S.C., C.L.F., R.G., H.C., M.C.M., H.S.C., and M.E.G.; methodology, T.S., M.E.G., R.G., H.C., and H.S.C.; validation, T.S., M.E.G., R.G., H.C., and H.S.C.; formal analysis, T.S.; investigation, T.S., C.L.F., and S.C.; resources, T.S., S.C., M.E.G., and C.L.F.; data curation, T.S., S.C., M.E.G., and C.L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, T.S., M.E.G., H.S.C., H.C., and R.G.; visualization, T.S. and M.E.G.; supervision, R.G., H.C., H.S.C., and M.E.G..; project administration, T.S., R.G., H.C., H.S.C., and M.E.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding..

Institutional Review Board

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration115 of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital (IRB #5220357).

Informed Consent

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective study design.

Data Availability

De-identified data underlying the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data will be provided in an Excel format, subject to institutional and ethical guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of pediatric residents Arjun Jindal, and Tiffany Seik Ismail, for their assistance with data collection. The authors also extend their sincere thanks to Steven L. Shein, for his valuable guidance on the interpretation and appropriate application of the Critical Bronchiolitis Score.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PICU |

Pediatric intensive care unit |

| SDICU |

Step-down intensive care unit |

| PCTICU |

Pediatric cardiac intensive care unit |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| LOS |

Length of stay |

| CBS |

Critical Bronchiolitis Score |

| LRS |

Level of respiratory support |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| RR |

Respiratory rate |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale |

| pCO₂ |

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide |

| SBP |

Systolic blood pressure |

| BUN |

Blood urea nitrogen |

| HFNC |

High-flow nasal cannula |

| NIMV |

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation |

| IMV |

Invasive mechanical ventilation |

| CXR |

Chest X-ray |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| AAP |

American Academy of Pediatrics |

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of collected data variables.

Table A1.

List of collected data variables.

| Variable |

Units |

Concept |

| Demographic data |

- |

Patient characteristics |

| Past medical history |

- |

Medical conditions prior to admission |

| Past surgical history |

- |

Surgical procedures prior to admission |

| Past family history of atopy in a first-degree relative |

- |

Family predisposition to atopic conditions |

| Home-oxygen use |

Yes/No |

Pre-admission oxygen therapy at home |

| Day-of-illness on presentation |

Days |

Duration of illness before presentation |

| Month and year of presentation |

Month/ Year |

Temporal factors of admission |

| Presence of viral infection |

Names of virus identified |

Confirmed viral etiology |

| ICU-LOS |

Days |

Length of ICU stay |

| Hospital LOS |

Days |

Length of hospital stay |

| HFNC use |

Yes/No, L/Kg, Days |

Duration of respiratory support |

| NIMV use (including nCPAP) |

Yes/No, Highest PIP/PEEP/RR/ FiO2, Days |

Duration of respiratory support |

| IMV use (including HFOV) |

Yes/No, Highest PIP/PEEP/MAP/RR/ FiO2, Days |

Duration of respiratory support |

| CXR use |

Yes/No |

Diagnostic modality |

| Other imaging- US, Echocardiography, CT |

Yes/No |

Diagnostics |

| Antibiotic use |

Yes/No |

Clinical management |

| Nebulizations- Albuterol, 3%, racemic epinephrine |

Yes/No |

Adjunctive therapies |

| Highest RR |

Breaths per minute |

Vital signs |

| Highest HR |

Beats per minute |

Vital signs |

| Highest temperature |

°C or °F |

Vital signs |

| Worst GCS |

GCS score |

Clinical decision tool |

| Lowest serum bicarbonate |

mmol/L |

Measure of dehydration |

| Lowest pH/highest pCO2 ratio |

pH, mmHg |

Measure of respiratory acidosis |

| Highest BUN |

mg/dL |

Measure of dehydration |

| Lowest SBP |

mmHg |

Vital signs |

References

- Nicolai, A.; Ferrara, M.; Schiavariello, C.; Gentile, F.; Grande, M. E.; Alessandroni, C.; Midulla, F. Viral bronchiolitis in children: a common condition with few therapeutic options. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, S7–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralston, S. L.; Lieberthal, A. S.; Meissner, H. C.; Alverson, B. K.; Baley, J. E.; Gadomski, A. M.; Johnson, D. W.; Light, M. J.; Maraqa, N. F.; Mendonca, E. A.; Phelan, K. J.; Zorc, J. J.; Stanko-Lopp, D.; Brown, M. A.; Nathanson, I.; Rosenblum, E.; Sayles, S., 3rd; Hernandez-Cancio, S.; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1474–e1502.

- Zurca, A. D.; González-Dambrauskas, S.; Colleti, J.; Vasquez-Hoyos, P.; Prata-Barbosa, A.; Boothe, D.; Combs, B. E.; Lee, J. H.; Franklin, D.; Pon, S.; Karsies, T.; Shein, S. L. Intensivists' reported management of critical bronchiolitis: more data and new guidelines needed. Hosp. Pediatr. 2023, 13, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almadani, A.; Noël, K. C.; Aljassim, N.; Maratta, C.; Tam, I.; Papenburg, J.; Quach, C.; Thampi, N.; McNally, J. D.; Lefebvre, M. A.; Zavalkoff, S.; O'Donnell, S.; Jouvet, P.; Fontela, P. S. Bronchiolitis management and unnecessary antibiotic use across 3 Canadian PICUs. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, K.; Tsugawa, Y.; Brown, D. F.; Mansbach, J. M.; Camargo, C. A., Jr. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J. H.; Schuh, S.; Rashidi, R.; Vanderby, S.; Lau, R.; Laporte, A.; Nauenberg, E.; Ungar, W. J. A cost effectiveness analysis of omitting radiography in diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2009, 44, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mount, M. C.; Ji, X.; Kattan, M. W.; Slain, K. N.; Clayton, J. A.; Rotta, A. T.; Shein, S. L. Derivation and validation of the Critical Bronchiolitis Score for the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 23, e45–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakis, D. A.; Cowan, C. A.; Garrison, M. M.; Molteni, R.; Marcuse, E.; Zerr, D. M. Variation in inpatient diagnostic testing and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, K.; Fergie, J. Concurrent serious bacterial infections in 2396 infants and children hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, J. H.; Lin, R. C.; Marneni, S.; Pandya, S.; Alhajri, S.; Sinert, R. Predictors of airspace disease on chest X-ray in emergency department patients with clinical bronchiolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J. N.; Rieder, M. J.; Walton, J. M.; Canadian Paediatric Society, Acute Care Committee, Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances Committee. Bronchiolitis: recommendations for diagnosis, monitoring and management of children one to 24 months of age. Paediatr. Child Health 2014, 19, 485–498. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, J. H.; Lin, R. C.; Marneni, S.; Pandya, S.; Alhajri, S.; Sinert, R. Predictors of airspace disease on chest X-ray in emergency department patients with clinical bronchiolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, S.; Lalani, A.; Allen, U.; Manson, D.; Babyn, P.; Stephens, D.; MacPhee, S.; Mokanski, M.; Khaikin, S.; Dick, P. Evaluation of the utility of radiography in acute bronchiolitis. J. Pediatr. 2007, 150, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bronchiolitis in children: diagnosis and management. NICE Guideline NG9, 2nd edition. 2015, updated 2021.

- Friedman, J. N.; Rieder, M. J.; Walton, J. M.; Canadian Paediatric Society, Acute Care Committee; Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances Committee. Bronchiolitis: recommendations for diagnosis, monitoring and management of children one to 24 months of age. Paediatr. Child Health 2014, 19, 485–498. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, J.; Breuer, A.; Breuer, O.; Hashavya, S.; Rekhtman, D.; Kerem, E.; Cohen-Cymberknoh, M. A quality improvement intervention to reduce emergency department radiography for bronchiolitis. Respir. Med. 2018, 137, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, S. B.; Walls, C.; Jain, S.; Plemmons, G.; Johnson, D. P. Reducing chest radiographs in bronchiolitis through high-reliability interventions. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020014597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).