1. Introduction

Bangladesh is among the most vulnerable nations in the world to the impacts of climate change. As the ninth most populous and twelfth most densely populated country, it has a rapidly growing population, and limited land resources have placed immense pressure on the urban ecosystem. The capital city, Dhaka, has undergone significant transformations in recent years to keep pace with the accelerated rate of urbanization. A surge in the real estate, construction, and housing sectors has accompanied this rapid shift. However, according to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Dhaka is now ranked among the most polluted cities in the world (Bhuiya, 2007).

The Bangladesh National Building Code (BNBC) and global LEED certification play a pivotal role in promoting environmentally sustainable construction in Bangladesh, where demand for energy-efficient buildings is rapidly increasing in both residential and industrial sectors. As one of South Asia's fastest-growing economies, the construction sector contributes over 8% to the national GDP (BBS, 2025). However, rapid urbanization has brought significant environmental challenges, including increased energy consumption, with electricity demand expected to grow by 9% annually (BBS, 2025). As a result, there is a rise in carbon emissions since the construction industry accounts for approximately 38% of global carbon emissions, and the depletion of natural resources. In Dhaka, groundwater levels drop by 1–2 meters per year due to excessive extraction (BBS, 2025). To address these issues, Green Building Standards are being increasingly adopted nationwide, helping to reduce energy usage, conserve resources, and lower building operating costs. The development and emerging trends of green building practices ensure a sustainable construction industry in Bangladesh (Starpath Holdings, 2025).

The construction industry has significant environmental, social, and economic impacts, with buildings affecting these areas throughout their lifecycle. While construction activities fulfill human needs, create jobs, and boost national economies, they also play a key role in advancing urbanization (Zuo & Zhao, 2014). Over recent decades, driven by population growth, rapid urbanization, and increasing social demands, issues such as heightened resource consumption (Hirokawa, 2009; Y. Li et al., 2014), high energy use and pollution have worsened (Azam et al., 2023). More than 30% of these problems are attributed to the construction industry, leading to environmental damage and resource waste (Yang & Hongyu, 2025). As global climate change and environmental concerns become more pressing, carbon emissions (CE) are recognized as one of the most critical global issues (D. Z. Li et al., 2013; X. Li et al., 2024; Y. Zhang et al., 2022). Achieving low-carbon development is now a consensus in most countries (Zhu et al., 2025). Low-carbon emissions depend on various factors, including architecture, economics, society, technology, energy, and other influences (Liu et al., 2020). Buildings and construction activities are responsible for 40% of global CO2 emissions, making them a primary driver of climate change.

The construction industry in Bangladesh faces numerous challenges in addressing the issues of insufficient housing and poor infrastructure while striving to operate in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. Despite the growing global interest in green building technology, understanding its adoption in Bangladesh remains limited. Various barriers and problems cause the slow progress of green buildings in Bangladesh. Companies should focus on adopting advanced technologies, utilizing renewable energy, and designing their operations with green principles from the earliest planning stages (UNIDO, 2011). Bangladesh has several significant projects, including power plants, deep-sea ports, high-tech parks, and rapid transit systems (MRTs).

Additionally, Bangladesh has consistently ranked at the top worldwide for environmental air pollution over the past decades. The construction sector in Bangladesh makes up a significant portion (10%) of the nation's total greenhouse gas emissions. Major concerns in Bangladesh include groundwater depletion (Das et al., 2018; S. Islam et al., 2017), inefficient use of finite resources in production processes, the unavailability of natural gas, and issues with waste management and occupational health and safety measures (Ahmed, 2014).

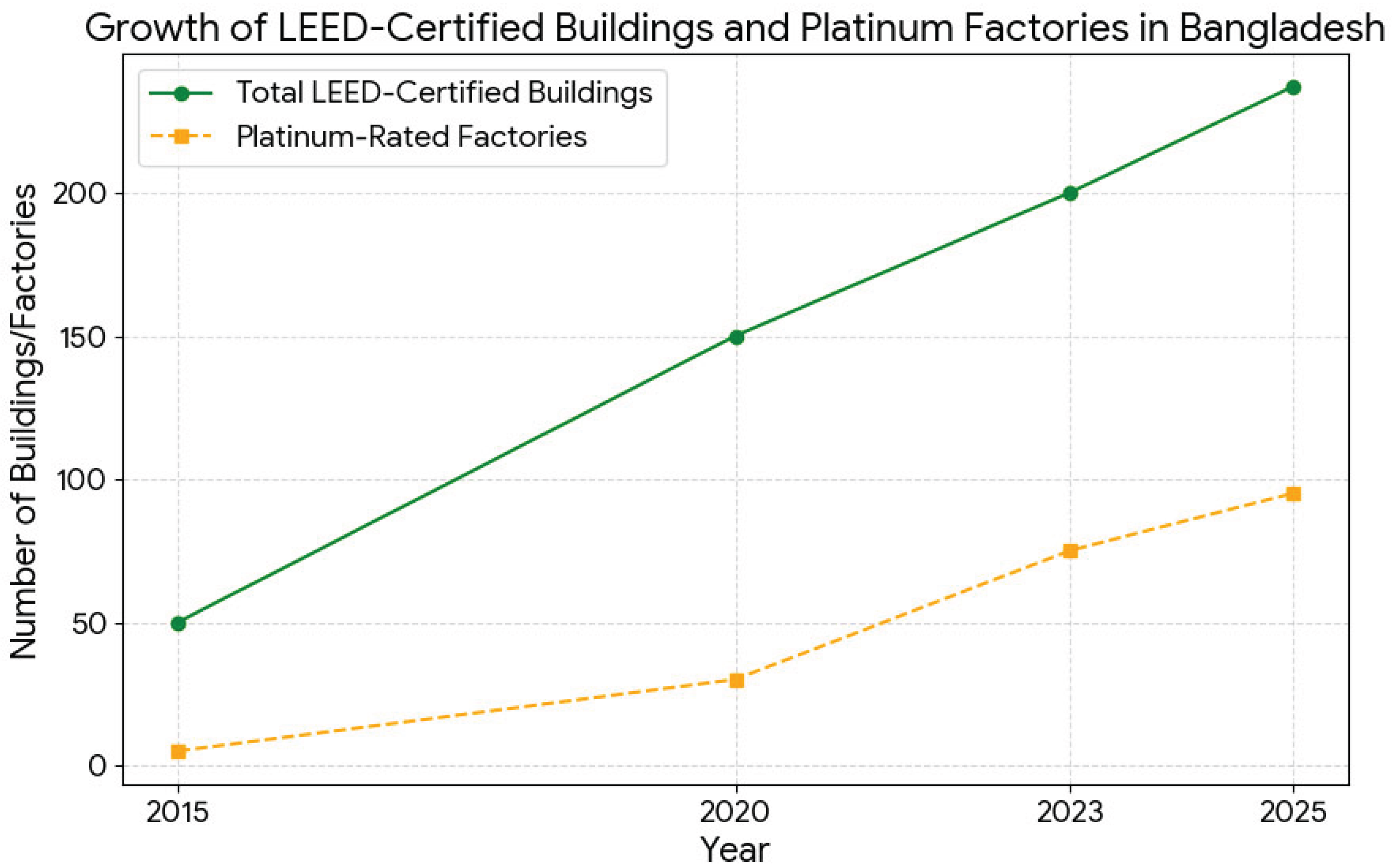

Since 2007, Bangladesh has made significant strides in promoting green buildings. The Eco-Housing Project by HBRI introduced low-cost, energy-efficient housing solutions, laying the groundwork for sustainable construction. In 2010, the country saw its first LEED-certified factory, marking the beginning of the green ready-made garment (RMG) movement. By 2012, the drafting of the Green Building Code by IFC and HBRI led to the integration of sustainability regulations into the Bangladesh National Building Code (BNBC). In 2014, the inclusion of an Energy Efficiency Chapter in BNBC mandated minimum green building standards, further advancing sustainable practices. By 2017, Bangladesh had surpassed 100 LEED-certified factories, strengthening its global recognition in the green industry. The enforcement of BNBC 2020 introduced mandatory renewable energy requirements for new projects. In 2024, the government approved the Bangladesh Energy Efficiency and Environmental Rating (BEEER) System, launching the country's own sustainability rating system. By May 2025, Bangladesh had achieved 243 LEED-certified factories, earning the distinction of being ranked number one globally in green RMG buildings (TextileFocus.com, 2025) as shown in

Figure 1.

Bangladesh has introduced several policies and regulations to promote sustainable construction. The Bangladesh National Building Code (BNBC) 2020 mandates energy-efficient design, rainwater harvesting, and the use of solar energy, making compliance compulsory for all new buildings. The Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority (SREDA) Act of 2012 promotes energy efficiency in construction projects, leading to an estimated 30% reduction in energy use in green buildings (TextileFocus.com, 2025). In 2024, the Building Energy Efficiency and Environment Rating (BEEER) System was launched to provide a sustainability rating for buildings, encouraging voluntary compliance with energy efficiency standards. The Green Financing Initiative, introduced by the Bangladesh Bank in 2016, offers low-interest loans for green projects and has since financed over 200 projects. Additionally, the updated Dhaka Building Construction Rules of 2023 mandate the use of eco-friendly materials, water recycling, and sustainable land use practices in all new developments.

Although several researchers worldwide have studied green buildings, few have done so in the context of Bangladesh. Currently, Bangladesh has over 7,000 factories employing more than 4.0 million workers (Mia et al., 2019). However, the number of green factories is very low compared to the total number of existing factories in Bangladesh (M. Islam et al., 2024). Previous research has identified significant obstacles to implementing green building technologies in the construction industry, including a lack of green building data, skills, stakeholder awareness, expertise, top management support, knowledge, well-documented green construction regulations, and limited availability (Tran et al., 2020). According to the World Air Quality Report 2024, Bangladesh is the second most polluted country in the world, ranking 15 times higher than the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines (Dhaka Tribune, 2025). It is crucial to reduce pollution by adopting sustainable building practices in the construction sector (Chowdhury et al., 2022). In this context, the study reviews existing research to identify gaps and opportunities for green building in Bangladesh, with a focus on a case study of Karupannya Rangpur Ltd., one of the country's leading green factories. It also examines the effects of green buildings on human health through factors such as temperature and water consumption, while exploring future opportunities for the development of green buildings.

2. Background and Concept of Green Buildings:

The origins of Green Building (GB) development date back to the energy crisis of the 1960s, which prompted vital research and initiatives aimed at enhancing energy efficiency and reducing environmental pollution (Mao et al., 2009). Coupled with the strong environmental movement of that era, these early efforts laid the foundation for the modern GB movement, centered on energy-efficient and eco-friendly construction practices. A significant milestone came with the 1992 Earth Summit (UNCED), which introduced the Rio Declaration and Agenda, further advancing global interest in environmental protection within the building sector. Earlier, in 1990, the UK’s Building Research Establishment (BRE) launched BREEAM, the first GB rating system, providing a structured framework to assess green building practices and performance (Ding et al., 2018). Since then, various countries have developed comprehensive GB assessment tools, led by governments and independent organizations, to evaluate and improve building quality (Alwisy et al., 2018a).

Green building (GB) definitions vary across countries and organizations, reflecting both environmental and human-centered priorities. In the USA, the World Green Building Council defines a GB as one that reduces or eliminates negative impacts while creating positive impacts on the climate and natural environment (WGBC, 2025). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) emphasizes environmentally responsible and resource-efficient practices across the building’s life cycle, from siting to deconstruction (EPA, 2025). At the same time, the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) highlights key considerations, including energy, water, indoor environmental quality, materials, and site impacts (USGBC, 2025). In the UK, the Building Research Establishment (BRE), through BREEAM, associates GBs with sustainable environments that enhance well-being, protect resources, and increase property value (BRE, 2025). The European Commission frames sustainable buildings as preserving the environment while promoting occupant well-being through improved space use and air quality (Strohmer, S., 2006). Similarly, the German Sustainable Building Council (DGNB, 2025) emphasizes conscious resource use, reduced energy consumption, and environmental preservation, whereas France's HQE certification focuses on energy, environment, health, and comfort. In Australia, the Green Building Council Australia (GBCA, 2025) incorporates sustainable development principles that balance present needs with future considerations. Japan's Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ, 2025) defines GBs as those designed to conserve resources, minimize emissions, align with local culture and environment, and improve human life quality while sustaining ecosystems. China's Assessment Standard of GBs emphasizes lifecycle resource efficiency, covering energy, land, water, and materials, as well as environmental protection and healthy indoor conditions (GB/T 50378, 2014). In Singapore, the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Sustainable Development (IMCSD) views GBs as energy- and water-efficient, built with eco-friendly materials, and integrated with green spaces to ensure high-quality indoor environments (BCA, 2025; Zhang et al., 2019).

Green building theory has become a vital focus for advancing sustainable development in the construction industry, attracting widespread attention (Shan & Hwang, 2018). Consequently, green building has become a significant topic in the property sector (Robinson, 2005). Green building is a substantial effort because it can reduce the use of resources, such as electricity, gas, and water, by utilizing energy-efficient appliances and systems. Additionally, it can reduce waste by using long-lasting products, including recycled carpet, natural linoleum, and bamboo flooring. It also requires maximizing health, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and durability during construction, maintenance, and cleaning. The most important goal of green buildings is to achieve environmental sustainability (Liu et al., 2021). Green buildings help improve environmental impact by reducing energy use by 30-50%, CO2 emissions by 35%, waste output by 70%, and water consumption by 40% (McManus, 2012). The protection of natural resources and ecosystems can be ensured by reducing the impacts of climate change with sustainable, environmentally friendly building constructions (Zhao et al., 2016). However, green buildings often require higher initial investments, such as high-performance HVAC ( Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning) systems, solar panels, and better insulation materials. At the same time, to reduce energy consumption, it may be necessary to sacrifice some comfort, such as reducing air conditioning usage and lowering lighting intensity, which may affect the comfort and satisfaction of residents or users (Liu et al., 2023). The performance of buildings is influenced by various factors, including the structure of the envelope (Zou et al., 2024), the building's scale, layout, and regional climate (Fu et al., 2023).

3. Green Buildings Certification Systems (GBCSs):

GBCSs are independent systems that review a building based on specific criteria to determine how "green" it is. The criteria used by these systems, which are developed through collaborations among a wide range of government and non-government organizations, industry representatives, and scientists, provide guidelines for green building design and construction within the industry. Independent organizations or government bodies typically give certificates. The content of certificates and identified efficiency criteria evolve in parallel with the development of building technology and updated laws and regulations, and the performance level required to obtain a certificate regularly increases. GBCSs have become vital tools for promoting more sustainable practices in environmental, economic, and social areas (Ebert et al., 2011).

3.1. Global Adopted Certifications:

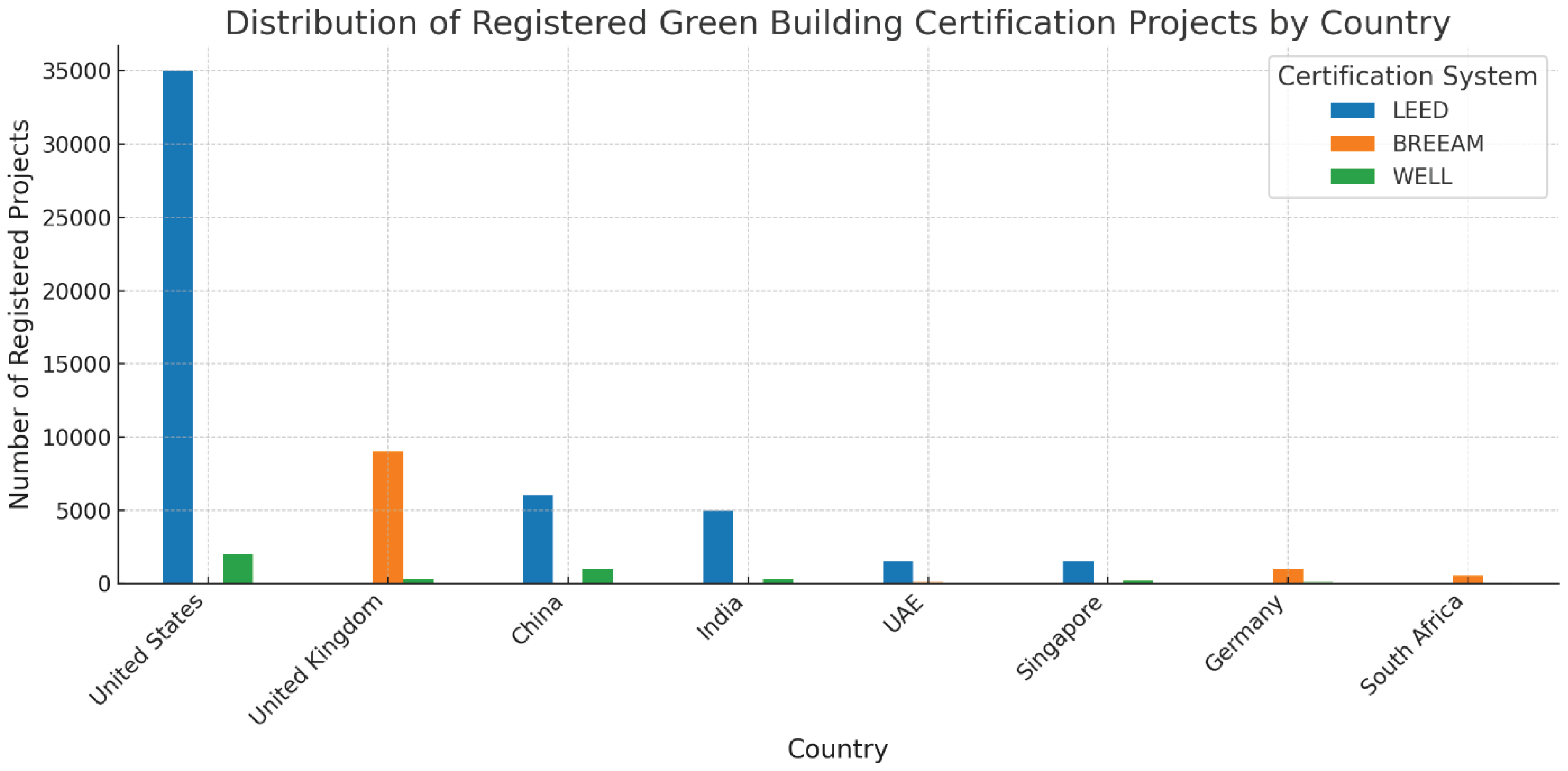

LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), developed by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), is a program that covers design, construction, operation, and maintenance across various building types and neighborhoods. As of 2024, there were over 195,000 LEED-certified buildings in 186 countries, with the highest representation in the United States, the United Kingdom, India, China, and the UAE (Katafygiotou et al., 2023; USGBC, 2025). LEED demonstrates top performance in the Energy and Carbon category due to its strict requirements for energy modeling, site optimization, and renewable energy integration. Projects like the Bullitt Center showcase LEED’s effectiveness in achieving ultra-low energy use intensities (EUIs) when paired with performance tracking. It also scores well in Economic Efficiency, driven by energy cost savings and demand-side management programs. However, LEED is comparatively weaker in Lifecycle Analysis and Health and Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ), where its metrics are optional or carry only marginal weight (Scheuer & Keoleian, 2002).

Figure 2.

Growth of LEED-Certified Buildings and Platinum Factories in Bangladesh.

Figure 2.

Growth of LEED-Certified Buildings and Platinum Factories in Bangladesh.

BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method), established in 1990 and led by the UK’s BRE, remains widely used in Europe and has expanded through region-specific adaptations such as BREEAM-NL and BREEAM-Gulf. BREEAM (Yeom et al., 2023; T. Zhang et al., 2022) ranks highest in Lifecycle Analysis, emphasizing full lifecycle carbon accounting, embodied emissions, and biodiversity preservation (Alwisy et al., 2018, 2018; Chen et al., 2015). Its system rewards the use of locally sourced materials, passive systems, and long-term design resilience. It also performs well in Community/Social and Economic Efficiency, particularly in European contexts where policies such as the EU Taxonomy influence building codes. Policies like the EU Taxonomy influence building codes (Diestelmeier & Cappelli, 2023).

WELL Building Standard focuses on the health and wellness (Ildiri et al., 2022) of occupants by assessing factors such as air quality, lighting, water, comfort, and overall mental well-being (Allen et al., 2015; Condezo-Solano et al., 2025). Although newer (launched in 2014), WELL has seen accelerated uptake post-pandemic due to its occupant-centric health metrics, particularly in urban corporate sectors in North America, Australia, and Southeast Asia (IWBS, 2019).

Figure 3. Sustainability certification-registered projects by country. The table shows the distribution of registered projects under LEED, BREEAM, and WELL certification systems across different countries (Cidell, 2009; Cole & Valdebenito, 2013; Saleh et al., 2024; Suzer, 2019).

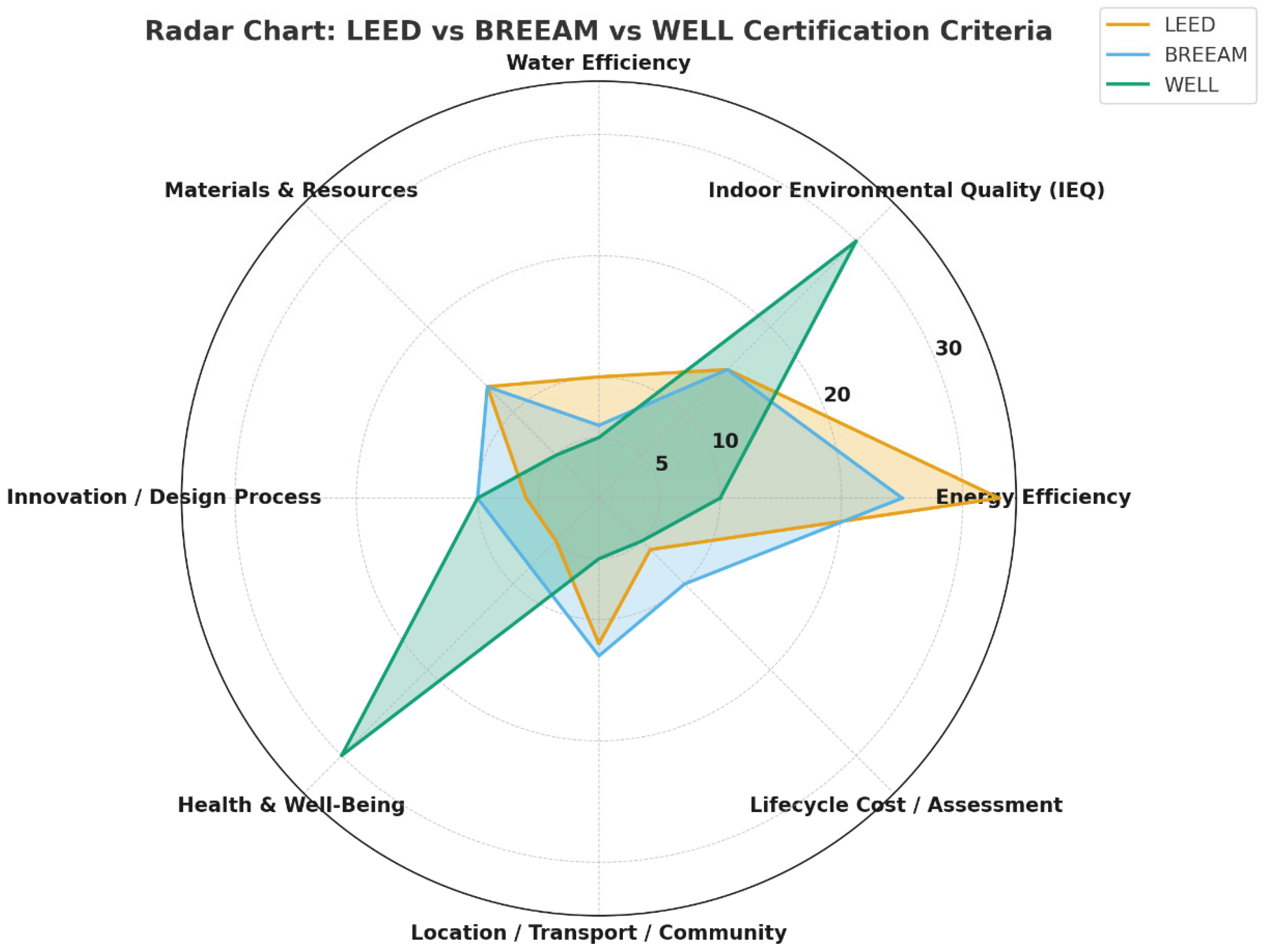

The comparison of certification criteria weighting across LEED, BREEAM, and WELL reveals key differences in emphasis among the three systems. LEED places the highest weight on energy efficiency (33%), followed by indoor environmental quality (15%) and materials/resources (13%) as shown in

Figure 4. BREEAM exhibits a more balanced distribution, with significant weight given to energy (25%), materials (13%), and indoor environmental quality (15%), while also acknowledging the importance of lifecycle assessment and innovation (10% each). In contrast, WELL strongly emphasizes indoor environmental quality (30%) and health and well-being (30%), reflecting its focus on human-centered design rather than purely environmental factors. Overall, environmental categories (energy, water, and materials) dominate in LEED (56%) and BREEAM (44%), whereas WELL prioritizes occupant health and comfort (20%). This highlights the distinct philosophies of the three systems: LEED and BREEAM are more environmentally performance-driven, while WELL is more human health-driven (Allen et al., 2015b; Kent et al., 2024; D. H. Wong et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2017).

3.2. Regional & National Certification Systems

The Green Star (Australia) and the Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA) were established in 2002 as a national not-for-profit organisation dedicated to developing a sustainable property industry in Australia (Xia et al., 2013). In 2003, the GBCA launched its green building rating system, known as "Green Star". Australia is the most significant single contributor of greenhouse gases and generates approximately 40% of the world's waste. Green Star is aimed at improving environmental efficiencies in buildings, while also boosting productivity, creating jobs, and enhancing the health and well-being of communities. Initially, GBCA had Green legacy tools, and by the end of 2015, all these tools were superseded by a new set of green building rating tools. These tools include four green building rating systems for Design and as-built, Interiors, Communities, and Performance, which also assess the sustainability of projects at all stages of the life cycle. The Green Star performance tool assesses green buildings during their operational stage (Negarestani et al., 2025). The Green Star certification criteria and prerequisites are presented as follows (

Figure 5):

The Chinese evaluation standard for green buildings (ESGB) is similar to the evaluation standards of other countries and tools for the operational phase of buildings, which is minimal. However, in China, a country-specific green building rating tool exists, known as the Chinese Evaluation Standard for Green Buildings. The concept of green building was first introduced to China in the 1990s, and an evaluation standard was subsequently developed. In June 2006, the Ministry of Construction issued "the green building evaluation criteria" (Evaluation Standard for Green Building, hereinafter referred to as ESGB) (GB/T50378-2006), which was the first national standard for evaluating green buildings in China. It published the 2014 edition of "Green Building Evaluation Criteria" (GB/T50378-2014) in January 2015 (Ma et al., 2016).

CASBEE (Japan), The Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency, was initiated in 2002 by the Japan Sustainable Building Consortium. CASBEE includes lifecycle CO₂ assessment and a star-rating system, and it is integrated into local policies such as Sustainable Building Reporting Systems (S. C. Wong & Abe, 2014). CASBEE for Urban Development (CASBEE-UD) was developed in 2006 to assess the environmental efficiency of planned projects comprising multiple buildings and public areas (Murakami et al., 2007). CASBEE was first developed to assess the performance of individual buildings. The assessment scope was then expanded from individual buildings to a town block and urban development scale to assess the environmental efficiency of planned projects comprising multiple buildings and public areas. Finally, its scope was widened to a city scale (Murakami et al., 2011).

BEPAC (Building Environmental Performance Assessment Criteria), introduced in Canada in 1993 by the University of British Columbia, was a precursor to modern green building rating systems in the region, focusing on energy efficiency, indoor air quality, and resource consumption (Cole, 1994). PromisE, launched in Finland in 2002 by the VTT Technical Research Station, is tailored to Finnish construction and environmental conditions, assessing energy use, material choices, indoor environment quality, and water management (Y. Zhang et al., 2019). BEAM Plus, initially introduced in Hong Kong in 1996 and updated in 2010, assesses sustainability performance in high-density urban environments, taking into account site aspects, materials, energy, water, and indoor environmental quality (Yeung et al., 2022).

EcoEffect, developed in Sweden in 1997 (Assefa et al., 2010), and Eco-Quantum, from the Netherlands, in 1999 (Boonstra & Knapen, 2000), are lifecycle assessment tools used for evaluating energy, material use, and environmental impacts. BEAT from Denmark in 2000 (Y. Zhang et al., 2019) and Ecoprofil from Norway in 2000 (S & H, 1997) focus on environmental and health performance, including energy, indoor climate, and material impacts. South Korea's KGBC, established in 2002 (Jeong, 2011), certifies buildings based on energy efficiency, resource conservation, and ecological impact.

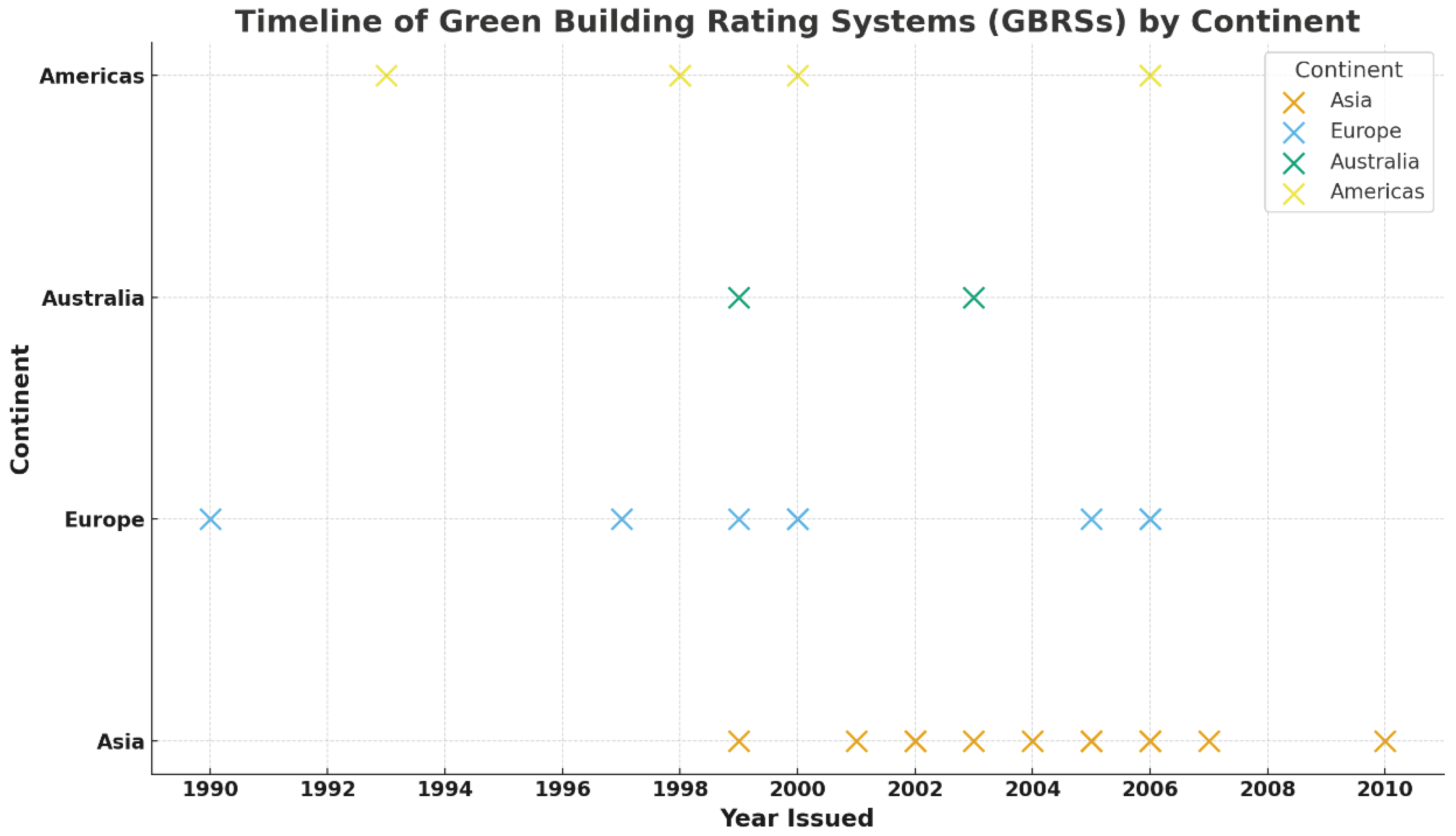

In India, TERI developed TGBRS in 2003 as a precursor to GRIHA, which launched in 2004 to provide a holistic national rating system addressing site planning, energy efficiency, occupant comfort, and water and waste management (Pamu & Mahesh, 2019). France’s HQE (2005) manages environmental impacts through 14 targets in eco-construction, eco-management, comfort, and health (Sinou et al., 2006), while Israel’s Si-5281 standard (2005) addresses energy, water, materials, and land use (Cohen et al., 2017). Singapore’s Green Mark (2005) emphasizes energy and water efficiency in a tropical urban context (Agarwal et al., 2017). Germany's DGNB system (2006) adopts a holistic lifecycle approach, considering environmental, economic, and sociocultural factors (Braune et al., 2019). In contrast, the UK's Code for Sustainable Homes (CSH, 2006) establishes standards for sustainable residential construction (O’Malley et al., 2014). Finally, Abu Dhabi’s Estidama Pearl Rating System (EPRS, 2007) focuses on sustainable design, construction, and operation in hot, arid climates, prioritizing water conservation, energy efficiency, and cultural preservation (Alkaabi & Thesis, 2019). The timeline of Green Building Rating Systems (GBRSs) issued by the continents is given in the

Figure 6.

4. Case Study Area

The study was conducted at Green Factory Karupannya Rangpur Ltd., located in Bangladesh, at the GPS coordinates (25.7257° N, 89.2639° E) within Rangpur Sadar District. The Climate of the Rangpur Sadar Upazila is moderate with equable temperature (6.0–36.3 °C), high humidity, and plenty of rainfall (1932 mm) (Roy et al., 2021).

4.1. Data Collection

The factories of Karupannya Rangpur Ltd. and surrounding conventional households were visited, and real-time data were collected with the help of a digital temperature meter from the selected study sites. Again, the recorded data, including water use and energy consumption, were collected from the respective organizational inventory. Manager of the Human Resources & Administration Department at Karupannya Rangpur Ltd., was interviewed. All relevant data concerning green building activities, indoor environment, achievements, costs, durability, LEED certification projects and activities, the LEED rating system, and LEED certification levels were recorded from observations and interviews as shown in

Figure 7.

According to the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) rating system, there are nine categories: integrated process, area and transportation, sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, indoor environmental quality, innovation, and regional priority. These categories of the LEED rating system indicate the parameters of a green building. A total of 110 points is available across these nine categories. Here, we see that the importance of energy and atmosphere is greater than any other category, accounting for 33 points out of 110. Buildings use energy, materials, water, and land to create a suitable environment for occupants. All these resources come at a cost and have an environmental impact. The Bangladesh Green Building Council (BGBC) assigns ratings to buildings in the following categories. The certification levels and their corresponding point requirements are displayed in

Table 1. Additionally,

Table 2 illustrates how the points necessary for certifications are allocated across different categories.

The LEED certificate is worth a total of 110 points. Among them-The collected temperature and water use data were analyzed to compare and assess the impacts of green buildings versus traditional buildings in Bangladesh. The study employed a questionnaire-based approach for human health impact assessment, in which several questions were asked of employees from green factories, comprising a sample group of 20 individuals, as given in

Table 3.

4.2. Results and Discussion

The study was conducted in accordance with the LEED rating system. The test results have been discussed based on real-time data collection of temperature and water use from renewable sources, thereby reducing water consumption from groundwater. Interview-based results on human health and the environment are shown below.

The LEED rating system provides independent, third-party verification that a building, home, or community was designed and built using strategies aimed at achieving high performance in key environmental and human health areas. The LEED green building rating system is flexible enough to apply to all building types, including commercial, residential, and entire neighborhood communities. It functions throughout the building’s lifecycle, including design and construction, operations and maintenance, tenant fit-out, and significant retrofit. The environmental impact and performance of the building are assessed using a whole-building approach to sustainability. LEED certification is granted when a project meets all prerequisites and earns a minimum number of credits by adopting sustainable strategies related to energy efficiency, water savings, building materials, indoor environmental quality, location and transportation, site development, innovative strategies, and regionally focused priorities. A total of 110 credits is available to LEED applicants. LEED offers a framework for healthy, efficient, low-carbon, and cost-effective green buildings. Certification from LEED is a globally recognized symbol of sustainability achievement and leadership. LEED-certified buildings save money, increase efficiency, reduce carbon emissions, and create healthier environments for people. They are essential in addressing climate change, enhancing resilience, and supporting more equitable communities.

The LEED rating system has nine areas of concentration. Among these, the result will be discussed with the energy and atmosphere category as given in

Table 4.

Karupannya Rangpur Ltd scored 71 out of 110 points and was certified as “LEED Platinum” because its scores fall within the 68-110 range. This study highlights the significance of the energy and atmosphere category, which is valued more highly than any other category. According to this category, Karupannya Rangpur Ltd. scored 23 out of 71 points.

The temperatures inside and outside Karupannya and the conventional building in Rangpur were recorded three times a day. The measurements were taken at 9:00 a.m., 2:00 p.m., and 5:00 p.m. The temperature data were collected weekly.

Table 4 shows that the average temperature difference for Karupannya is 4.33 degrees Celsius, while the difference for the conventional building is 1.67 degrees Celsius.

Table 5.

Weekly Average Inside and Outside Temperature of Green Building and Conventional Building.

Table 5.

Weekly Average Inside and Outside Temperature of Green Building and Conventional Building.

Location |

9:00 am |

2:00 pm |

5:00 pm |

| Inside Temp. (OC) |

Outside Temp. (OC) |

Inside Temp. (OC) |

Outside Temp. (OC) |

Inside Temp. (OC) |

Outside Temp. (OC) |

| Karupannya |

23 |

27 |

25 |

30 |

24 |

28 |

| Con. Building |

25 |

27 |

28 |

30 |

27 |

28 |

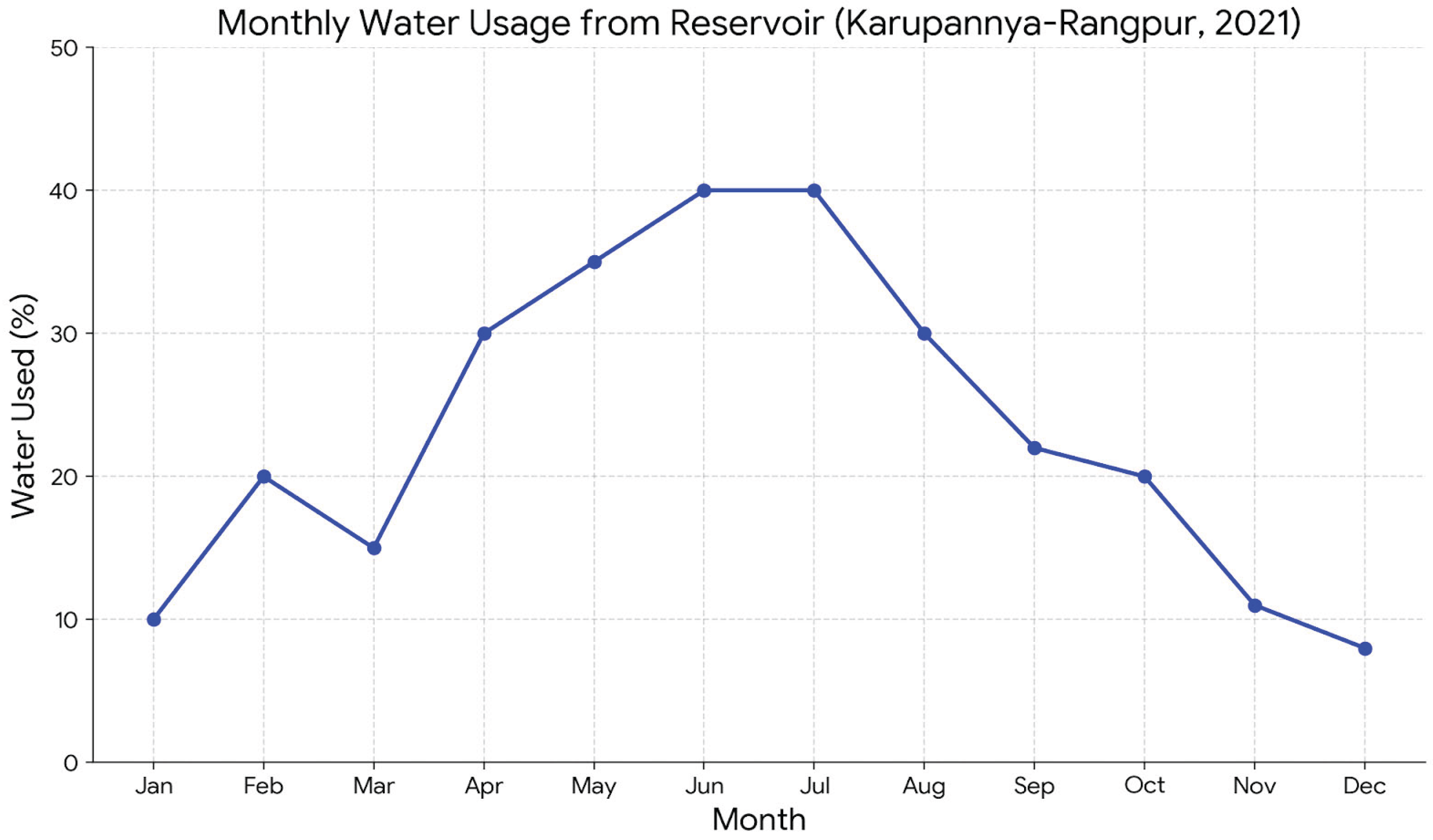

The monthly water use data from renewable water sources were collected from the study areas. The table shows that the highest percentage of water, 40%, was used from renewable water sources in March and July 2021, while the lowest percentage, 6.5%, was used in January 2021 as shown in

Figure 8.

The survey result showed overwhelmingly positive feedback about the working environment and sustainability features. Most workers reported feeling comfortable even during the summer for natural cooling systems such as south-facing reservoirs, wall-mounted greenery, and ventilators, which lowered indoor temperatures by 4 to 6°C and reduced electricity use by up to 80% (M. Islam et al., 2024). Employees appreciated the clean, odor-free, low-emission environment and confirmed the availability of amenities such as medical centers, canteens, and prayer rooms. While 90% of participants reported feeling more productive and cheerful in the green environment, awareness of LEED certifications was moderate, with only 58% acknowledging that their factory was certified. Overall, the green design inspired by traditional Bengali architecture significantly improved thermal comfort, energy efficiency, and employee well-being. It was observed that herbs were growing on the walls of the buildings at the tops, and questions were raised about how these plants were cultivated and what made the employees feel comfortable in a green environment (M. Islam et al., 2024).

In response, it was explained that special techniques were used to ensure proper airflow inside the factories. Traditional folk knowledge from rural Bengal was applied in this cooling process. The south-facing sides of the factories were designed with large reservoirs, reminiscent of countryside architecture, where a pond on the southern side cools the incoming air. Various species of trees were planted randomly on the building walls and fronts, with herbs hanging from the walls. Ventilators were installed on every floor, allowing air to rise and circulate, which helped lower the interior temperature by 4 to 6 degrees Celsius. This passive cooling led to an 80% reduction in electricity usage, effectively minimizing energy waste.

Hot air was released through ventilators, following the natural principle that hot air rises and cold air falls. Rainwater was collected in reservoirs and used for external purposes, such as toilet flushing. Machines produced hot air on each floor, which was allowed to escape through floor vents and then was released via ventilators above the windows. Barometers were installed on each floor to measure temperature. Sunlight hit the south-facing walls, but the verandas and windows, at 4.5 feet high, along with the green herbaceous trees outside, blocked solar heat from entering the buildings. In winter, northern windows were kept shut to block the cold winds, while planters on the south side, filled with herbaceous plants, helped keep the interior warm. These planters were irrigated through a deep watering system. Trees in front of the buildings swayed in the south wind, naturally cooling the environment.

These design strategies were beneficial for women workers, as comfortable conditions allowed them to work more efficiently. It was observed that working in green environments improved worker morale and reduced production disruptions. Additionally, women's roles within families were strengthened through employment in these factories. It was emphasized that these factories do not emit black smoke, produce foul-smelling wastewater, or release chemical pollutants. Workers expressed satisfaction with the 100% eco-friendly environment, improved security, and low carbon emissions. Additionally, amenities such as medical centers, grocery stores, canteens, prayer rooms, and ATM booths were available within the factory premises.

This study should consider opportunities during the design phase to enhance energy efficiency and protect the atmosphere, such as reducing building energy consumption, utilizing less harmful refrigerants, generating on-site renewable energy, providing ongoing energy savings, and purchasing green power for the project. It should also address materials and resource considerations, such as promoting recycling, reusing existing buildings, reducing construction waste, using salvaged and recycled content materials, utilizing rapidly renewable (agricultural) materials, and certified wood products. Additionally, it may focus on indoor environmental quality by improving indoor air quality, increasing outside air ventilation, managing air quality during construction, using only non-toxic finishes, carpets, and composite wood products, reducing exposure to toxic chemicals during building operations, providing individual comfort control, and maintaining thermal comfort standards for sustainable green building technology.

For the development of the green construction sector, there is no alternative to energy-efficient building practices, such as those discussed in the 104th International Conference on Green Architecture (Seraj et al., 2018). Implementing these green building technologies will significantly relieve the government and future generations from energy problems. Architects and engineers should consider these factors during the design phase. Using energy-efficient equipment will ultimately help convert buildings into environmentally friendly structures. The outcomes of this research, including reduced energy demand, will benefit both Bangladesh and the world. Suppose we commit to implementing green building policies. In that case, we can save electricity, protect the environment, and enhance social interaction, thereby achieving a smart, green power plant, sustainability, and balanced social development in Bangladesh.

5. Conclusions

The temperature in the Green Building has significantly decreased by creating a microclimate through water circulation and the presence of multiple trees within the building, compared to traditional buildings in Bangladesh. The rainwater reservoir, located in the Green Building, stores rainwater for use throughout the year. This enables the factories to reduce groundwater extraction, thereby saving natural resources and protecting the environment. In China, a similar decrease in temperature and water use was found by (Liu et al., 2021) that helped to achieve environmental sustainability.

Green Buildings reduce consumption of non-renewable resources, minimize waste, and create healthy, productive environments. Green building can optimize site potential; minimize non-renewable energy use; protect and conserve water; improve indoor environmental quality; and optimize operational and maintenance practices through rainwater harvesting, passive systems, active systems, hybrid systems, wastewater recycling, radiant heating and cooling, passive heating and cooling, building massing, and orientation.

Green building has many benefits and have a significant impact on the environment, economy, and society. However, these buildings have some disadvantages, such as the higher cost of constructing green buildings compared to regular buildings. The construction cost of a green industrial manufacturing building is about 28% higher than that of a conventional building. However, long-term benefits are available despite the additional costs.

References

- Agarwal, S. , Sing, T. F., & Yang, Y. (2017). Are Green Buildings Really “Greener”? Energy Efficiency of Green Mark Certified Buildings in Singapore. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. F. (2014). Urbanization and Environmental Problem: An Empirical Study In Sylhet City, Bangladesh. 4(3). www.iiste.

- Alkaabi, N. , & Thesis, M. (2019). Resilience of green buildings to uncertainty in operation patterns. https://khazna.ku.ac.ae/ws/portalfiles/portal/16939697/20217.

- Allen, J. G., MacNaughton, P., Laurent, J. G. C., Flanigan, S. S., Eitland, E. S., & Spengler, J. D. (2015a). Green Buildings and Health. Current Environmental Health Reports, 2(3), 250–258. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. G., MacNaughton, P., Laurent, J. G. C., Flanigan, S. S., Eitland, E. S., & Spengler, J. D. (2015b). Green Buildings and Health. Current Environmental Health Reports, 2(3), 250–258.

- Alwisy, A. , BuHamdan, S., & Gül, M. (2018a). Criteria-based ranking of green building design factors according to leading rating systems. Energy and Buildings, 178, 347–359. [CrossRef]

- Alwisy, A. , BuHamdan, S., & Gül, M. (2018b). Criteria-based ranking of green building design factors according to leading rating systems. Energy and Buildings, 178, 347–359. [CrossRef]

- Architectural Institute of Japan(AIJ). (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.aij.or.jp/aijhome.htm.

- Assefa, G. , Glaumann, M., Malmqvist, T., & Eriksson, O. (2010). Quality versus impact: Comparing the environmental efficiency of building properties using the EcoEffect tool. Building and Environment, 45(5), 1095–1103. [CrossRef]

- Azam, A. , Ateeq, M., Shafique, M., Rafiq, M., & Yuan, J. (2023). Primary energy consumption-growth nexus: The role of natural resources, quality of government, and fixed capital formation. Energy, 263, 125570. [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics-Government of the People \'s Republic of Bangladesh. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://bbs.gov.bd/.

- Bangladesh now has 243 LEED-certified factories. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://textilefocus.com/bangladesh-now-has-to-243-leed-certified-factories/.

- Bhuiya. G. M. J. A (2007). 1. Bangladesh. Solid Waste Management: Issues and Challenges in Asia, pg 29. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from http://www.apo-tokyo.org/publications/files/ind-22-swm.pdf.

- Boonstra, C. , & Knapen, M. (2000). Knowledge infrastructure for sustainable building in the Netherlands. Construction Management & Economics, 18(8), 885–891. [CrossRef]

- Braune, A. , Geiselmann, D., Oehler, S., & Ruiz Durán, C. (2019). Implementation of the DGNB Framework for Carbon Neutral Buildings and Sites. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 290(1), 012040. [CrossRef]

- BREEAM: What is BREEAM? (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://web.archive.org/web/20150923194348/http://www.breeam.org/about.jsp?id=66.

- Building and Construction Authority (BCA). (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www1.bca.gov.sg/.

- Buildings and Their Impact on the Environment: A Statistical Summary. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/recs/recs97/decade.html#totcons4.

- Chen, X. Yang, H., & Lu, L. (2015). A comprehensive review of passive design approaches in green building rating tools. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 50, 1425–1436. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M. A. , Sabrina, H., Zzaman, R. U., & Islam, S. L. U. (2022). Green building aspects in Bangladesh: A study based on experts' opinion regarding climate change. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(7), 9260–9284. [CrossRef]

- Cidell, J. (2009). Building Green: The Emerging Geography of LEED-Certified Buildings and Professionals. The Professional Geographer, 61(2), 200–215. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C. , Pearlmutter, D., & Schwartz, M. (2017). A game theory-based assessment of the implementation of green building in Israel. Building and Environment, 125, 122–128. [CrossRef]

- Cole, R. J. (1994). Building environmental performance assessment criteria, BEPAC. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD (United States).

- Cole, R. J. , & Valdebenito, M. J. (2013). The Importation of Building Environmental Certification Systems: International Uses of BREEAM and LEED. Building Research & Information, 41(6), 662–676. [CrossRef]

- Condezo-Solano, M. J. , Erazo-Rondinel, A., Barrozo-Bojorquez, L. M., Rivera-Nalvarte, C. C., & Giménez, Z. (2025). Global Analysis of WELL Certification: Influence, Types of Spaces, and Level Achieved. Buildings 2025, Vol. 15, Page 1321, 15(8), 1321. [CrossRef]

- Das, N. , Touhidul Islam, M., Symum Islam, M., & M Adham, A. K. (2018). Response of dairy farm’s wastewater irrigation and fertilizer interactions to soil health for maize cultivation in Bangladesh. Asian-Australasian Journal of Bioscience and Biotechnology, 3(1), 33–39. [CrossRef]

- DGNB's sustainability approach | DGNB. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.dgnb.de/en/sustainable-building/dgnbs-sustainability-approach.

- Diestelmeier, L. , & Cappelli, V. (2023). Article: Conceptualizing' Energy Sharing' as an Activity of 'Energy Communities' under EU Law: Towards Social Benefits for Consumers? Journal of European Consumer and Market Law, 12(1). https://kluwerlawonline.com/api/Product/CitationPDFURL?file=Journals\EuCML\EuCML2023010.

- Ding, Z. , Fan, Z., Tam, V. W. Y., Bian, Y., Li, S., Illankoon, I. M. C. S., & Moon, S. (2018). Green building evaluation system implementation. Building and Environment, 133, 32–40. [CrossRef]

- Ebert, T. , Eßig, N., & Hauser, G. (2011). Green building certification systems. In Green Building Certification Systems. DETAIL - Institut für internationale Architektur-Dokumentation GmbH & Co. KG. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z. L. Guo, W., Wang, L., Ma, J., Shi, L. W., & Lin, M. (2023). Ecological network evolution analysis in the collective intelligence design ecosystem. Advanced Engineering Informatics 58, 102150. [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50378-2014 Green Building Evaluation Standard – Policies - IEA. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.iea.org/policies/7915-gbt-50378-2014-green-building-evaluation-standard.

- Green Building Standards in Bangladesh | Regulations & Trends. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://starpathholdings.com/navigating-green-building-standards-in-bangladesh/.

- Hirokawa, K. H. (2009). At Home with Nature: Early Reflections on Green Building Laws and the Transformation of the Built Environment. Environmental Law, 39. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.

- Home - World Green Building Council. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://worldgbc.org/.

- Ildiri, N. , Bazille, H., Lou, Y., Hinkelman, K., Gray, W. A., & Zuo, W. (2022). Impact of WELL certification on occupant satisfaction and perceived health, well-being, and productivity: A multi-office pre- versus post-occupancy evaluation. Building and Environment, 224, 109539. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. Nijum, N., on, S. D.-7th I. C., & 2024, undefined. (n.d.). From Conventional to Green Building: A Framework for Green Factory Transformation in Bangladesh. Researchgate.Net. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nusrat-Nijum/publication/379188971_FROM_CONVENTIONAL_TO_GREEN_BUILDING_A_FRAMEWORK_FOR_GREEN_FACTORY_TRANSFORMATION_IN_BANGLADESH/links/65fee971a4857c796273e71c/FROM-CONVENTIONAL-TO-GREEN-BUILDING-A-FRAMEWORK-FOR-GREEN-FACTORY-TRANSFORMATION-IN-BANGLADESH.pdf.

- Islam, S. , Islam, T., Al, S. A., Hossain, M., Adham, A. K. M., Islam, D., & Rahman, M. M. (2017). Impacts of dairy farm’s wastewater irrigation on growth and yield attributes of maize. Fundamental and Applied Agriculture, 2(2), 247–255. https://www.f2ffoundation.org/faa/index.

- IWBS: Building Standard v2-pilot, 2019 - Google Scholar. (n.d.). Retrieved August 25, 2025, from https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=WELL+Building+Standard+v2+Pilot&author=International+WELL+Building+Institute&publication_year=2022.

- Jeong, H. (2011). Sustainability Policy and Green Growth of the South Korean Construction Industry. https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/ETD-TAMU-2011-08-9987.

- Katafygiotou, M. Protopapas, P., & Dimopoulos, T. (2023). How Sustainable Design and Awareness May Affect the Real Estate Market. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 16425. 15(23), 16425. [CrossRef]

- Kent, M. G. , Parkinson, T., & Schiavon, S. (2024). Indoor environmental quality in WELL-certified and LEED-certified buildings. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. Environmental, M. S.-B. J. of, & 2022, undefined. (n.d.). Perceptions and Barriers to the Construction of Green Buildings (GB) in Bangladesh. Researchgate.NetFI Khan, M Shammi, Bangladesh Journal of Environmental Research, 2022•researchgate.Net. Retrieved August 21, 2025, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fariha-Khan-18/publication/365265235_Perceptions_and_Barriers_to_the_Construction_of_Green_Buildings_GB_in_Bangladesh/links/636c86b4431b1f5300866f7e/Perceptions-and-Barriers-to-the-Construction-of-Green-Buildings-GB-in-Bangladesh.pdf.

- LEED v4.1 | U.S. Green Building Council. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.usgbc.org/leed/v41.

- Li, D. Z. Chen, H. X., Hui, E. C. M., Zhang, J. B., & Li, Q. M. (2013). A methodology for estimating the lifecycle carbon efficiency of a residential building. Building and Environment 59, 448–455. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Chen, H., & Xian-jiaWang. (2021). Research on green renovations of existing public buildings based on a cloud model –TOPSIS method. Journal of Building Engineering, 34, 101930. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Chen, H., Zhang, L., Wu, X., & Wang, X. Jia. (2020). Energy consumption prediction and diagnosis of public buildings based on support vector machine learning: A case study in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 272, 122542. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Li, T., Xu, W., Wang, Q., Huang, H., & He, B. J. (2023). Building Information Modelling (BIM)- enabled multi-objective optimization for energy consumption parametric analysis in green building design using hybrid machine learning algorithms. Energy and Buildings, 300, 113665. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Lin, C., Lin, M., & Jim, C. Y. (2024). Drivers and spatial patterns of carbon emissions from residential buildings: An empirical analysis of Fuzhou city (China). Building and Environment, 257, 111534. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , Yang, L., He, B., & Zhao, D. (2014). Green building in China: Needs great promotion. Sustainable Cities and Society, 11, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ma, A. , Qian, J. ;, Ye, Q. ;, Song, Q. ;, Visscher, K. ;, & Zhao, H. ; (2016). New Development of China’s National Evaluation Standard for Green Building (ESGB-2014).

- Mao, X. , Lu, H., & Li, Q. (2009). A comparison study of mainstream sustainable/green building rating tools in the world. Proceedings - International Conference on Management and Service Science, MASS 2009. [CrossRef]

- McManus, B. (n.d.). Green Buildings Certifications Executive summary.

- Mia, S. , Economics, M. A.-, & 2019, undefined. (n.d.). Ready-made garments sector of Bangladesh: Its growth, contribution, and challenges. Davidpublisher.ComS Mia, M Akter, Economics, 2019•davidpublisher.Com. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.davidpublisher.com/Public/uploads/Contribute/5dd507c82e7dd.pdf.

- Murakami, S. , Asami, Y., Kaburagi, S., Uchiike, T., Yamaguchi, N., Ikaga, T., Matsukuma, A., & Hashimoto, T. (2007). Outline of CASBEE for Urban development (CASBEE-UD) CASBEE; Comprehensive assessment system for building environmental efficiency, Part 5. AIJ Journal of Technology and Design, 13(25), 191–196. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S. , Kawakubo, S., Asami, Y., Ikaga, T., Yamaguchi, N., & Kaburagi, S. (2011). Development of a comprehensive city assessment tool: CASBEE-City. Building Research & Information, 39(3), 195–210. [CrossRef]

- Negarestani, M. N. , Hajikandi, H., Fatehi-Nobarian, B., & Sardroud, J. M. (2025). Introducing a green structure based on the pattern of the TOPSIS method by the grey wolf algorithm. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Engineering Sustainability, 178(3), 202–217. [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, C. , Piroozfar, P. A. E., Farr, E. R. P., & Gates, J. (2014). Evaluating the Efficacy of BREEAM Code for Sustainable Homes (CSH): A Cross-sectional Study. Energy Procedia, 62, 210–219. [CrossRef]

- Pamu, Y. & Mahesh, K. (2019). A Comparative Study on Green Building Rating Systems in India in terms of Energy and Water. CVR Journal of Science and Technology 16(1), 21–25. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. (n.d.). PROPERTY VALUATION AND ANALYSIS APPLIED TO ENVIRONMENTALLY SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT.

- Roy, B. , Bari, E., Nipa, N. J., & Ani, S. A. (2021). Comparison of temporal changes in urban settlements and land surface temperature in Rangpur and Gazipur Sadar, Bangladesh, after the establishment of the city corporation. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 23, 100587. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, N. M. , Saleh, A. M., Hasan, R. A., Keighobadi, J., Khalil Ahmed, O., Hamad, Z. K., & History, A. (2024). Analyzing and Comparing Global Sustainability Standards: LEED, BREEAM, and PBRS in Green Building Arch Article Topic. Babylonian Journal of Internet of Things, 2024, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, C. W. , & Keoleian, G. A. (n.d.). Evaluation of LEEDTM Using Life Cycle Assessment Methods.

- Seraj, F. , … M. J., the 2018 I. C. on, & 2018, undefined. (n.d.). Performance evaluation of window location and configuration to improve daylighting of residential apartment buildings. Researchgate.NetF Seraj, MAR JoarderProceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Green, 2018•researchgate.Net. Retrieved August 21, 2025, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fariha-Seraj/publication/330440692_PERFORMANCE_EVALUATION_OF_WINDOW_LOCATION_AND_CONFIGURATION_TO_IMPROVE_DAYLIGHTING_OF_RESIDENTIAL_APARTMENT_BUILDINGS/links/5c441fc992851c22a382535b/PERFORMANCE-EVALUATION-OF-WINDOW-LOCATION-AND-CONFIGURATION-TO-IMPROVE-DAYLIGHTING-OF-RESIDENTIAL-APARTMENT-BUILDINGS.pdf.

- S, F. , & H, H. F. (1997). Ecoprofile for buildings: a method for environmental classification of buildings. https://www.aivc.

- Shan, M. , & Hwang, B. Gang. (2018). Green building rating systems: Global reviews of practices and research efforts. Sustainable Cities and Society, 39, 172–180. [CrossRef]

- Sinou, M. , Kyvelou, S., & Bidou, D. (2006). The HQE Approach: Realities and Perspectives on Building Environmental Quality. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 17(5), 587–592. [CrossRef]

- Strohmer, S. Green Buildings in Europe—Regulations,... - Google Scholar. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C44&q=Strohmer%2C+S.+Green+Buildings+in+Europe%E2%80%94Regulations%2C+Programs%2C+and+Trends%3A+An+Interview+with+Robert+Donkers.+Bridges+2006%2C+11%2C+1%E2%80%935.&btnG=.

- Suzer, O. (2019). Analyzing the compliance and correlation of LEED and BREEAM by conducting a criteria-based comparative analysis and evaluating dual-certified projects. Building and Environment, 147, 158–170. [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q. , Nazir, S., Nguyen, T. H., Ho, N. K., Dinh, T. H., Nguyen, V. P., Nguyen, M. H., Phan, Q. K., & Kieu, T. S. (2020). Empirical Examination of Factors Influencing the Adoption of Green Building Technologies: The Perspective of Construction Developers in Developing Economies. Sustainability 2020, Vol. 12, Page 8067, 12(19), 8067. [CrossRef]

- UNIDO GreeN INDUstry INItIatIve for sustainable Industrial Development. (n.d.).

- What is a green building? - Green Building Council of Australia. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.gbca.au/about/what-is-green-building.

- What is a green building? |, U.S. Green Building Council. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.usgbc.org/articles/what-green-building.

- Wong, D. H. , Zhang, C., Di Maio, F., & Hu, M. (2024). Potential of BREEAM-C to support building circularity assessment: Insights from case study and expert interview. Journal of Cleaner Production, 442, 140836. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S. C. , & Abe, N. (2014). Stakeholders’ perspectives of a building environmental assessment method: The case of CASBEE. Building and Environment, 82, 502–516. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P. Song, Y., Shou, W., Chi, H., Chong, H. Y., & Sutrisna, M. (2017). A comprehensive analysis of the credits obtained by LEED 2009 certified green buildings. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 68, 370–379. [CrossRef]

- Xia, B. Zuo, J., Skitmore, M., Pullen, S., & Chen, Q. (2013). Green Star Points Obtained by Australian Building Projects. Journal of Architectural Engineering, 19(4), 302–308. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. , & Hongyu, C. (2025). Research on factors influencing total carbon emissions of construction based on structural equation modeling: A case study from China. Building and Environment, 275, 112396. [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S. , An, J., Hong, T., & Kim, S. (2023). Determining the optimal visible light transmittance of semi-transparent photovoltaic considering energy performance and occupants’ satisfaction. Building and Environment, 231, 110042. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, H. C. , Ridwan, T., Tariq, S., & Zayed, T. (2022). BEAM Plus Implementation in Hong Kong: An Assessment of Challenges and Policies. International Journal of Construction Management, 22(14), 2830–2844. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. , Gu, J., Ardakanian, O., & Kim, J. (2022). Addressing data inadequacy challenges in personal comfort models by combining pretrained comfort models. Energy and Buildings, 264, 112068. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Jiang, X., Cui, C., & Skitmore, M. (2022). BIM-based approach for the integrated assessment of life cycle carbon emission intensity and life cycle costs. Building and Environment, 226, 109691. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Wang, H., Gao, W., Wang, F., Zhou, N., Kammen, D. M., & Ying, X. (2019a). A Survey of the Status and Challenges of Green Building Development in Various Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11(19), 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Wang, H., Gao, W., Wang, F., Zhou, N., Kammen, D. M., & Ying, X. (2019b). A Survey of the Status and Challenges of Green Building Development in Various Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11(19), 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. , Hwang, B. G., & Gao, Y. (2016). A fuzzy synthetic evaluation approach for risk assessment: a case of Singapore’s green projects. Journal of Cleaner Production, 115, 203–213. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. , Xu, W., Luo, W., Yang, M., Chen, H., & Liu, Y. (2025). RETRACTED: Application of a hybrid machine learning algorithm in the multi-objective optimization of green building energy efficiency. Energy, 316, 133581. [CrossRef]

- Zou, R. Yang, Q., Xing, J., Zhou, Q., Xie, L., & Chen, W. (2024). Predicting the electric power consumption of office buildings based on dynamic and static hybrid data analysis. Energy 2024, 290, 130149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J. , & Zhao, Z. Y. (2014). Green Building Research–Current Status and Future Agenda: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 30, 271–281. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).