1. Introduction

Passiflora edulis, commonly known as passion fruit, is an economically important fruit crop with yellow passion fruit (

Passiflora edulis f.

flavicarpa Deg.) and purple passion fruit (

Passiflora edulis f.

edulis) being the two most commercially important types for passion fruit production [

1]. Native to South America, passion fruit has been widely introduced and is cultivated throughout tropical and subtropical regions, including parts of Asia, Africa, and Oceania. In recent years, the cultivation area of passion fruit has expanded significantly in China, particularly in the southern provinces such as Guangxi and Guangdong, driven by increasing consumer demand and governmental initiatives supporting tropical fruit development [

2]. However, its production faces several significant challenges, particularly its susceptibility to biotic stresses, including flower rot [

3], stem rot [

4], Phytophthora blight [

5] and various viral infections [

6,

7]. These diseases not only reduce yield and fruit quality but also threaten the long-term sustainability of cultivation in affected regions.

Flower rot of passion fruit, caused by

Rhizopus stolonifer, is an emerging and economically significant disease, particularly affecting its reproductive organs [

3]. The disease primarily manifests during the flowering and fruit-setting stages, resulting in flower necrosis, premature abscission, and significant yield losses [

8]. The development of flower rot is promoted by warm and humid environmental conditions, making it particularly prevalent in tropical and subtropical cultivation regions. Flower rot has been reported to cause yield losses up to 60% under favorable environmental conditions, posing a serious threat to commercial passion fruit production [

3]. Despite its growing prevalence and substantial economic burden, comprehensive insights into its etiology, epidemiology and the development of effective, integrated management approaches remain insufficient.

Long-read genome sequencing was performed to gain insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of R. stolonifer and to identify genes related to its reproduction, metabolism, and stress responses. To generate a high-quality, chromosome-level genome assembly, we employed PacBio high-fidelity (HiFi) sequencing in combination with Hi-C chromatin conformation capture technology. This genome resource will contribute towards understanding the pathogenicity and aiding the development of improved strategies to manage flower rot of passion fruit in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collecting and Fungal Isolate

Passion fruit samples showing symptoms of flower rot were collected from fields in Wuhua, Guangdong (23.81°N, 115.71°E) on yellow passion fruit plants at flowering. Under aseptic conditions, the diseased flower pieces were surfaced sterilized using 1% bleach, rinsed in steriled water, blotted dry on paper towels, and then placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium at 25°C for 2 days. Resultant mycelia were sub-cultured onto new PDA plates, after which monoconidial cultures were generated. Isolate PRFJ02, was identified as Rhizopus stolonifer by morphology and molecular analysis.

2.2. DNA extraction and genome sequencing

A starter culture of the isolate PRFJ02 was placed on PDA and grown for 3 days at 25°C. From the subsequent growth, five mycelia disks (~10 mm in diameter) were transferred to 250 mL Erlenmeyerflasks containing 200 mL Potato Dextrose Broth and incubated on shaker for 3 days at 25°C. The mycelia mass was then filtered through sterile cheesecloth and rinsed with sterile distilled water to remove any remaining media. The mycelia mass was used to extract genomic DNA using a MagAttract HMW DNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of total DNA was performed with the Quant-iTPicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The isolate was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (NGS) and a PacBio SMRT flow cell, respectively. Genomic library for paired-end (2 × 400 bp) sequencing on an Illumina sequencing platform was constructed by Personalbio Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) using the TruSeqTM DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The required library for PacBio SMRT sequencing was prepared using the PacBio Template Prep Kit 1.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Summarily, genomic DNA was sheared to an average fragment size of 10-15 kb by g-TUBE. The fragmented DNA was then ligated with specific adapters and subjected to enzymatic digestion. Size selection for fragments 10-15 kb was performed using the BluePippin system (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, USA) to construct SMRTbell library. The purified libraries were subsequently assessed for quality and size distribution using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) prior to sequencing on the PacBio Revio platform. Based on an existing draft genome assembly generated from NGS and PacBio sequencing data, Hi-C sequencing data was performed to cluster the draft genome sequences into chromosomal groups and to determine the order and orientation of sequences within each chromosome, thereby improving the assembly to the chromosome level. The genomic DNA library for Hi-C sequencing was generated with TruSeq DNA PCR-free prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced for paired-end (2 × 150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

2.3. Genome assembly

Quality control of raw sequencing data was conducted using fastp (v0.20.0) (

https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp) to trim adapters, remove low-quality reads, and filter out reads with high levels of ambiguous bases. In advance of genome assembly, short-insert libraries (insert size <1,500 bp) obtained through NGS sequencing were analyzed to estimate basic genome parameters, such as genome size, heterozygosity, and repeat content by using GenomeScope 2.0 [

9]. HiFi reads obtained from PacBio sequencing were initially assembled de novo using Hifiasm (v0.18.5). To elevate the assembly to the chromosome level, Hi-C sequencing data were processed with HiC-Pro (v3.1.0) [

10], with the restriction enzyme site set to GATCGATC (EcoRI) and all other parameters kept at default values. Hi-C reads were mapped using Chromap (v0.1.3) [

11] to generate alignments, which were used to anchor and scaffold the draft genome assembly to the chromosome level. The T2T (telomere-to-telomere) genome assembly was polished using NextPolish (v1.4.0) with PacBio HiFi reads to enhance the accuracy and quality of the genome assembly. The completeness of the final chromosome-level assembly was assessed using QUAST initially [

12] and then BUSCO v5.4.5 (

http://busco.ezlab.org) based on the lineage specific BUSCO dataset mucorales_odb10 from the order Mucorales [

13]. Telemore repeats of 5’-ACAACC-3’ were detected on each chromosome sequence using the ‘telo’ function of the tool ‘seqtk’ (

https://github.com/lh3/seqtk).

2.4. Gene prediction

The assembly was then annotated for functional elements including repeats, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and protein-coding genes. The tandem repeat sequences in the genome were firstly predicted and masked using Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF, v4.10.0) [

14]. RepeatModeler (v2.0.4) [

15] and RepeatMasker (v4.1.4,

http://www.repeatmasker.org) [

16] were then utilized to detect and generate a genome-wide profile of repetitive elements in PRFJ02. To annotate ncRNAs in the genome, tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE (v2.0) [

17], and rRNA genes were identified using Barrnap (v0.9) [

18]. Protein-coding genes were performed using Augustus (v2.5.5) [

19], GlimmerHMM (version 3.0.4) [

20], and GeneMark-ES (version 4.71) software [

21]. Homology-based gene prediction was conducted using Exonerate (v2.2.0) software by aligning protein sequences from closely related species to the assembled genome. To obtain a high-confidence, non-redundant gene set, gene models derived from de novo prediction and homology-based approaches were integrated using EVidenceModeler (EVM, v2.0.0) [

22].

2.5. Functional annotation

Functional annotation of protein-coding genes was carried out using multiple databases. Protein sequences were aligned to the NCBI non-redundant (nr) protein database (release 2017.10.10) using DIAMOND (v2.0.14) [

23] with an E-value threshold of 1e-6, and the best hit was retained for functional assignment. Functional annotation of protein-coding genes based on orthology was performed using eggNOG-mapper (V4.5) [

24]. KEGG and COG annotations were obtained by mapping gene sequences to the their respective databases. To obtain more precise annotations, the Swiss-Prot database was queried using BLAST with default parameters. InterPro (v66.0, release 2017.11.23) [

25] was used to identify conserved protein domains and motifs. The resulting InterPro entries were processed in InterPro2GO database to obtain GO terms, which were then mapped to a list of GO slims using map2slim tool (

https://github.com/elhumble/map2slim, accessed on 18 February 2025). Protein domains were identified using HMMER (v3.3.2) against the Pfam database (release 35.0), and functional annotation of protein-coding genes related to pathogen–host interactions was performed by aligning protein sequences against the PHI-base (Pathogen–Host Interactions database, version 4.17) using BLASTP with an E-value cutoff of 1e-5. The best hit was retained for annotation. The CAZy database (

http://www.cazy.org, accessed on 7 October 2025) and the Database of Fungal Virulence Factors (DFVF) (

http://sysbio.unl.edu/DFVF/index.php, accessed on 7 October 2025) was performed using Diamond (v2.0.14) to classify carbohydrate-active enzymes and fungal virulence factors, respectively.

2.6. Subcellular localization analysis

The signal peptide sequences in the predicted protein-coding genes were assessed using SignalP (v5.0) [

26] and TargetP (v2.0) [

27]. The transmembrane helix structures of the predicted protein-coding genes were predicted using TMHMM (v2.0) [

28]. Additionally, the prediction of effector proteins in pathogenic fungi was performed using EffectorP (v3.0) [

29], which identifies candidate effectors based on machine learning models trained on known effector sequences.

2.7. Whole-genome phylogenetic analysis

The genomes of 47 Rhizopus strains, as well as a single isolate of Sporodiniella umbellata (isolate MES1446), were retrieved from NCBI and then used to determine the phylogenetic placement of the R. stolonifer strain PRFJ02 sequenced in this study. Custom-made bash scripts were used to incorporate strain names into the FASTA headers of the genome sequences which allowed merging of alignments downstream.

All 48 genomes were loaded into the Galaxy computing environment (GalaxyCommunity 2024) and subject to de novo gene annotation using AUGUSTUS [30-32] (version 3.4.0), with

R. oryzae splicing models applied to obtain gene models without internal stop codons. The resulting protein sequences were then analyzed using BUSCO (--

mode prot) [

13] (v5.8.0) and the Mucorales lineage, and a custom bash script was used to filter for complete, single-copy amino acid sequences of each genome.

Protein FASTA sequences that were complete and single-copy in at least 36 of the 48 genomes were extracted using the seqkit grep command [

33] (version 2.9.0), aligned using MAFFT [

34] (version 7.520) using default settings, refined by removing poorly aligned regions with trimAl [

35] (version v1.5. rev0) using the

gappyout setting. The edited alignments were then concatenated using the seqkit concat command. A custom bash script was used to process the workflow from BUSCO and AUGUSTUS outputs to the final alignment [

36]. The final alignment consisted of 2,540,600 amino acids with 65% of those being invariant.

Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed using RAxML GUI version 2.0 [

37]. The best model, determined to be GTR+FO+I+G4m, was applied for the maximum likelihood tree search, with bootstrapping conducted using 100 replicates.

Sporodiniella umbellata isolate MES1446 was selected as the outgroup. The resulting phylogeny was imported into the interactive tree of life [

38] prior to export to Adobe Illustrator for final figure preparation.

2.8. Comparative analysis

To obtain orthologous gene clusters specific to

R. stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 versus those shared among multiple species of this genus, gene-encoding protein clustering in the genomes of

R. stolonifer (LSU 92-RS-03),

R. microsporus (ATCC11559),

R. delemar RA (99-880),

R. arrhizus (GL30), and

R. stolonifer (PRFJ02) were performed using the OrthoMCL algorithm and a e-value threshold of 1 × 10

−2 in the software OrthoVenn3 (

https://orthovenn3.bioinfotoolkits.net, accessed on 27 August 2025). GO term enrichment was performed by comparing a selected set of single-copy gene clusters (genes unique to each genome) with these of the background set (all single-copy gene clusters). Statistical testing (Fisher’s Exact Test) was then used to determine significant overrepresentation of GO terms at p < 0.01 with multiple test corrections applied.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pathogen isolation

Flower rot of passion fruit caused by

R. stolonifer has led to significant losses to the local passion fruit industry, with severe field infections observed (

Figure 1A).

R. stolonifera isolate PRFJ02 was isolated from flowers in a local passion fruit plantation in Guangdong, which exhibited severe rot symptoms, such as a mold layer covering the floral tissues and fruits and subsequent abscission of the pedicel (

Figure 1B-D). The fungal colonies on PDA exhibit diffuse, cottony mycelia that are hyaline and aseptate (

Figure 1E). The rhizoids, sporangia, and sporangiospores of

Rhizopus stolonifer PRFJ02 were clearly observed and their morphology was visualized and confirmed under a microscope (

Figure 1F-H).

3.2. Genome assembly

Kmer analysis using k = 19 in GenomeScope (v 1.0) and with Pac-bio short insert libraries (insert size < 1,500 bp) as input predicted a maximum genome size of 49 Mb, a genome repeat length of 28.4 Mb and a heterozygosity of 0.18% (

Figure S1).

Based on an approximately 138-fold coverage, a 48.2 Mb genome assembly containing 21 contigs was produced for

Rhizopus stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 using Hifiasm (

Table 1). Read pairs from Illumina Hi-C were filtered to obtain 49.7% of read pairs that were mapped as either singletons or to multiple locations (

Figure S2). Out of these, 70% of the read pairs have valid 3C interactions (p < 1x10

-5), based on alignment to the Restriction enzyme-digested fragments (

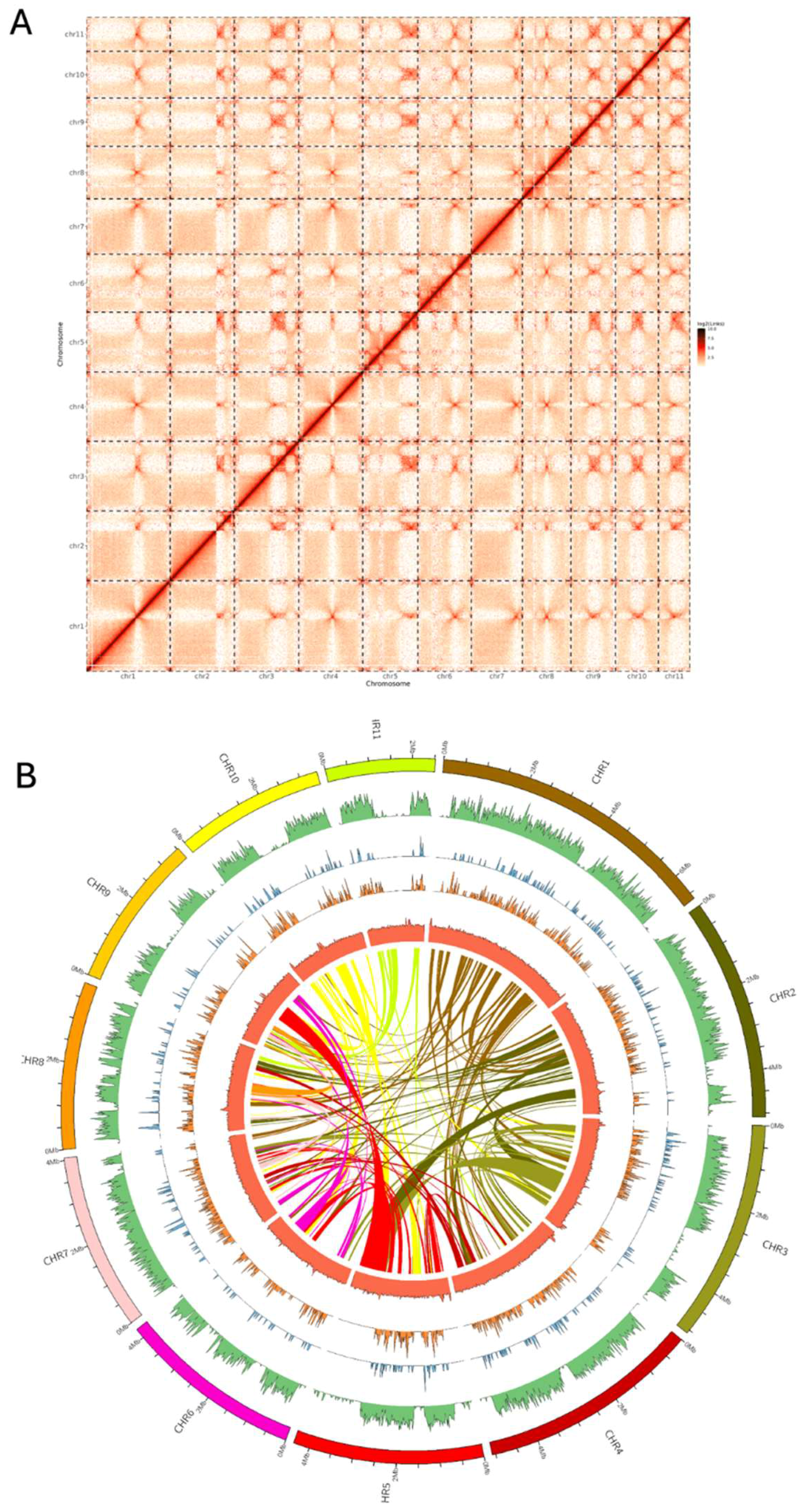

Figure S3). Hi-C contact map for

R. stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 shows that fungus carries 11 chromosomes (

Figure 2A). Each axis represents the 11 assembled chromosomes, ordered and oriented based on Hi-C contact density. The strong diagonal signals presesent intra-chromosomal contacts, whereas enriched off-diagonal interaction hotspots correspond to inter-chromosomal contacts, including centromere clustering that can be used to infer centromere positions. A total of 20 telomere regions containing the 5’-ACAACC-3’ repeats were identified on 10 out of 11 chromosomes of PRFJ02 (

Table S1). This visualization supports the correct chromosome-scale structure for each chromosome and confirms the near-completeness of the

R. stolonifer PRFJ02 assembly.

Nuclear genome of PRFJ02 was assembled into primary contigs with N50 of 4.2 Mb (

Table 1, Additional File 1). Genome completeness analysis showed a 95.2% BUSCO coverage (

Table 1). The PRFJ02 genome encoded 11,885 genes across 11 chromosomes, with an average gene length of 1530 bp (

Figure 2B). GC content averaged 35.2% across the genome. A total of 36,917 tandem repeats mostly micro- and minisatellite DNAs were masked using TRF. A total of 19,111,983 bp sequence was masked using RepeatMasker which occupied 39.64% of the total genome sequence (

Figure 2B,

Table S2). Retroelements, LTR elements, and DNA transposons occupied 3.34%, 2.92% and 2.46% of the total repeat sequence, respectively. Eighty-seven rRNA genes and 398 tRNA genes were detected, which occupied 0.25% and 0.06% of the PRFJ02 genome (

Table S3).

3.3. Functional annotations

A total of 11,737 protein-coding genes were annotated in PRFJ02 (

Table 1, Additional File 1). GO term classification for PRFJ02 revealed that the most enriched Biological Process terms were cellular nitrogen compound metabolic process (1934), biosynthetic process (1849), small molecule metabolic process (1201), transport (1121), and catabolic process (959) (

Figure S4). For the Cellular Component category, the top five terms included cell (3556), intercellular (3642), organelle (2681), cytoplasm (2314), and protein complex (811). In the Molecular Function category, the most abundant terms were ion binding (2415), DNA binding (647), oxidoreductase activity (597), kinase activity (566), and RNA binding (465).

KEGG annotation of the

R. stolonifer PRFJ02 genome showed protein-coding genes commonly associated with metabolism, particularly carbohydrate, amino acid, lipid, and energy metabolism, as well as secondary metabolite biosynthesis (

Figure S5). Genes related to Genetic Information Processing were also abundant, spanning translation, replication/repair, and protein and folding. Signal transduction formed the largest component of Environmental Information Processing, while additional genes were linked to Cellular Processes, including transport and catabolism. Overall, the KEGG classification showed that PRFJ02 possesses a strong metabolic capacity and regulatory flexibility. The three most abundant KOG categories are ‘Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis’,‘Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones’, and ‘Signal transduction mechanisms’ (

Table S4).

Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) represent a diverse group of enzymes that are essential for the degradation, modification, and synthesis of carbohydrates [

39]. A subset of these enzymes function as pathogen-secreted proteins that contribute to infection processes. Classification into the six CAZyme subfamilies [

39] revealed that

R. stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 contained 422 carbohydrate-active enzymes, with glycosyl transferases (146) and glycoside hydrolases (125) being the two most abundant classes (

Table S5, Additional File 2).

3.4. Effector Annotation

Fungal effectors are small, secreted proteins that aid host infection by suppressing plant host immune responses [

40]. These effectors are typically characterised by their small size, and a high cysteine content, which contributes to stability. Beyond that, fungal effectors can also be pivotal in broader microbial dynamics, including roles in establishing ecological niches and interaction with other microbes [

41]. To define the secretome of

R.

stolonifer isolate PRFJ02, 635 proteins carrying signal peptides were identified (Additional File 3), of which, 448, through Tmhmm analysis, contained no transmembrane domains, are therefore classified as secretory proteins (Additional file 4). These numbers are lower than the predictions previously reported for other fungal species [

42,

43]. Effector profiling using EffectorP revealed a total of 274 apoplastic effectors within the genome of PRFJ02 (Additional file 5). Characterising these effectors will offer insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying their pathogenicity in passion fruit.

3.5. Whole-genome phylogenetic analysis

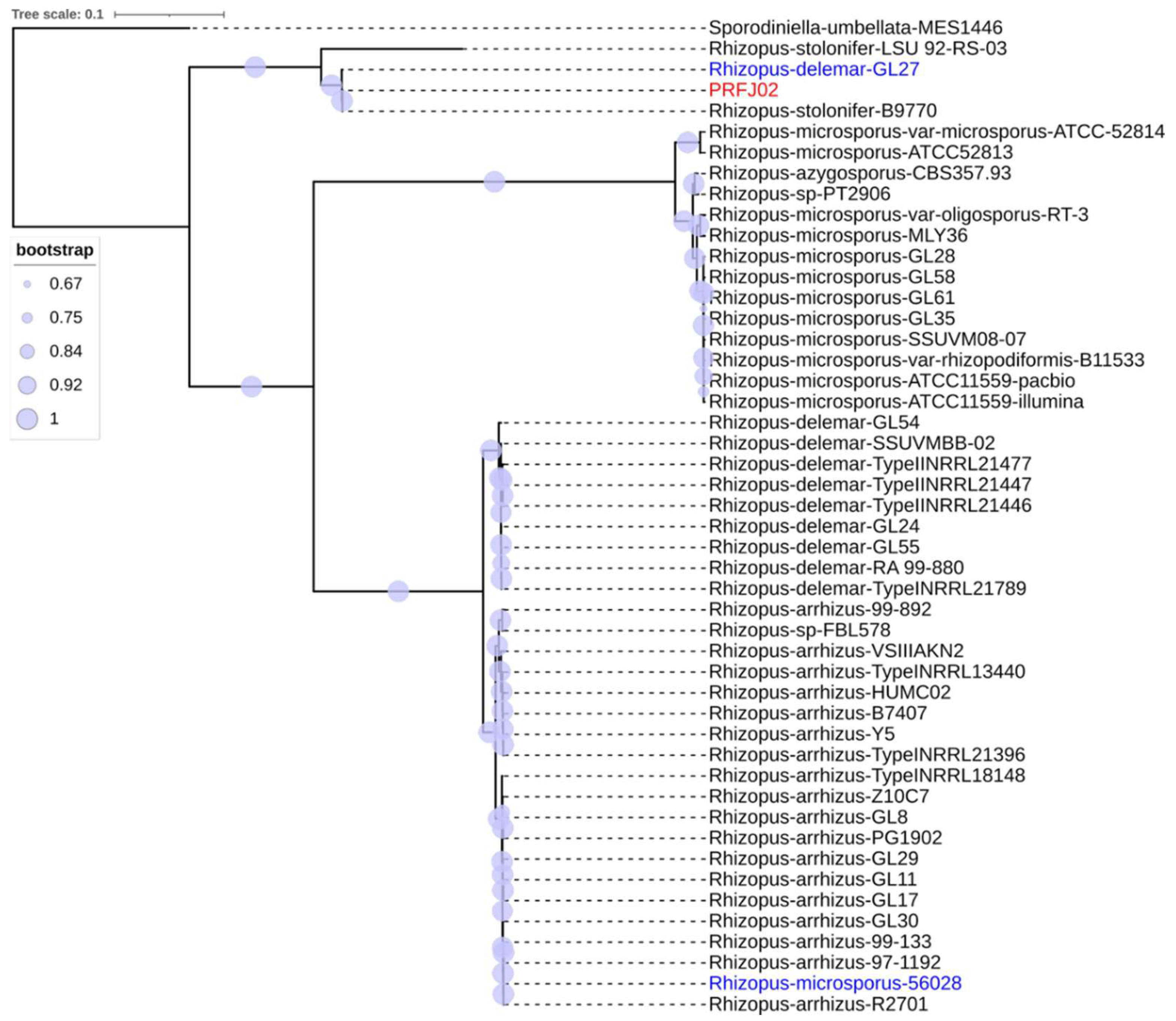

The final alignment included 48 isolates with genomes available from the genus

Rhizopus and comprised 2,540,600 sites, of which 278,101 were variable. The dataset contained 64.72% invariant sites and 22.68% gaps. In total, 1,421 genes were included in the alignment, selected on the basis of being complete, single-copy, and present in at least 36 of the 48 isolates. The phylogeny revealed that

R. stolonifer forms a distinct phylogroup that is separate from a larger clade containing other

Rhizopus species, namely

R. microsporus,

R. delemar, and

R. arrhizus (

Figure 3). Within this broader clade,

R. delemar is closely related to but clearly distinct from

R. arrhizus.

R. microspores and

R. azygosporus clustered together as an independent subclade, separate from the

R. delemar and

R. arrhizus phylogroup. Two isolates, highlighted in blue, displayed incongruence between their taxonomic classification and phylogenetic placement (

Figure 3). The phylogenetic position of PRFJ02 within the

R. stolonifer clade confirmed its identity.

3.6. Comparative study

Protein clustering analysis using OrthoVenn3 revealed 12,269 conserved orthologous clusters in

R. stolonifer isolate LSU 92-RS-03,

R. microsporus isolate ATCC11559,

R. delemar RA isolate 99-880,

R. arrhizus isolate GL30, and

R. stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 (

Table S6). A core orthologous gene set of 5,568 was evident, of which 3,526 appeared to be single-copy orthologues amongst the five genomes.

Orthologous clustering showed that

R. stolonifer isolates PRFJ02 and LSU 92-R03 possessed 85 (322) and 63 (153) unique clusters (genes), respectively (

Figure S6). Significant GO terms (p < 0.01) unique to PRFJ02 included carbohydrate binding, nuclease activity, response to cytokinin, proton transport, NADH dehydrogenase activity, DNA recombination, and electron transport, while LSU 92-R03 was associated with cAMP-mediated signaling and maltose alpha-glucosidase activity (

Table S7). Both isolates had significant GO terms for translation and transmembrane transport in their unique clusters.

In PRFJ02, GO enrichment analysis revealed significant overrepresentation of terms related to carbohydrate binding, suggesting a role in plant host cell wall recognition and interaction. Additional enrichment was observed in processes linked to translation and energy metabolism, including electron transport and ATP synthesis, indicative of elevated metabolic activity. Enrichment of nuclease activity and DNA recombination points to potential genomic adaptability, while the response to cytokinin suggests possible involvement in host hormone signaling pathways. Collectively, these enriched functions highlight key molecular features associated with the pathogenic potential of PRFJ02. Overall, this analysis reveals the extent of conservation and divergence in orthologous gene content among the Rhizopus isolates, highlighting both species-specific and shared gene clusters.

4. Conclusion

This study presents the first chromosome-level genome assembly of R. stolonifer, the causal agent of flower rot in passion fruit. The high-quality assembly allowed a high-confidence set of annotations to be produced. Whole-genome phylogenetic reconstruction confirmed the distinct evolutionary placement of R. stolonifer within this genus, while comparative analyses revealed both conserved orthologs and isolate-specific gene clusters linked to host interaction and adaptation. In particular, the enrichment of functions associated with carbohydrate binding, translation, and energy metabolism in PRFJ02 underscores potential molecular drivers of pathogenicity. These genomic resources and insights not only improve our understanding of the pathogenicity of R. stolonifer but also provide a foundation for developing resistant passion fruit cultivars and sustainable management strategies to mitigate the impact of flower rot disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Kmer analysis using k = 19; Figure S2: Hi-C Illumina read pair data filtering; Figure S3: Read pairs alignment on Restriction Fragments; Figure S4: GO term classification for the genome of Rhizopus stolonifer isolate PRFJ02; Figure S5: KEGG classification for the genome of Rhizopus stolonifer isolate PRFJ02; Figure S6: Comparative analysis of orthologous gene clusters among five Rhizopus isolates; Table S1: Telomeric repeats (‘ACAACC’) were identified at the chromosomal ends of Rhizopus stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 using seqtk_telo; Table S2: Identification of repetitive elements in the genome of Rhizopus stolonifer PRFJ02 using RepeatMasker; Table S3: rRNA and tRNA genes identified in the genome of PRFJ02; Table S4: Clustering of Rhizopus stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 proteins based on the functional classification of KOG; Table S5: Classification of Rhizopus stolonifer isolate PRFJ02 proteins into the six CAZyme subfamilies; Table S6. Overall results of the protein orthologous clustering analysis using Orthovenn3 and R. stolonifer isolate LSU 92-RS-03, R. microsporus isolate ATCC11559, R. delemar RA isolate 99-880, R. arrhizus isolate GL30, and R. stolonifer isolate PRFJ02. Table S7: GO enrichment analysis showing GO terms (p < 0.01) detected in the orthologous gene clusters unique to each of the Rhizopus stolonifer isolates PRFJ02 and LSU 92-RS-03.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and A.C.; methodology, J.S. and A.C.; software, X.Z., D.M.G and G.C.; validation, J.S., G.C. and A.C.; formal analysis, D.M.G., X.Z. and L.Y.; investigation, G.C. and L.Y.; resources, G.C.; data curation, X.Z. and D.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S. and A.C; writing—review and editing, , J.S., D.M.G., E.A.B.A. and A.C; visualization, X.X.; supervision, A.C., E.A.B.A.; project administration, A.C. and J.S.; funding acquisition, L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Passion Fruit Breeding and Cultivation Position Project of Guangxi Innovation Team of National Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (nycytxgxcxtd-2024-17-03),Guangxi key R & D projects (Guike AB23026070) and Scientific Research Project of Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Guinongke 2025YP089). This work was supported by Australian Research Council Research Hub for Sustainable Crop Protection (IH190100022) funded by the Australian Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original raw data presented in the study are openly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under Bioproject PRJNA1337812 and accession numbers SRR35738425 and SRR35738426. The genome assembly and its annotations described in this study are available in Additional File 1. The data analysis outputs presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Material/additional files.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by Galaxy Australia, a service provided by Australian BioCommons and its partners. The service receives NCRIS funding through Bioplatforms Australia, as well as The University of Melbourne and Queensland Government RICF funding.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Santos-Jiménez, J.L.; Montebianco, C.d.B.; Olivares, F.L.; Canellas, L. P.; Barreto-Bergter, E.; Rosa, R.C.C.; Vaslin, M.F.S. Passion fruit plants treated with biostimulants induce defense-related and phytohormone-associated genes. Plant Gene 2022, 30, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xu, Y.; Gui, J.; Huang, Y.; Ma, F.; Wu, W.; Han, T.; Qiu, W.; Yang, L.; Song, S. Characterization of Dof transcription factors and the heat-tolerant function of PeDof-11 in passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. M.; Chen, G.; Huang, Y.C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J.Z.; Qin, J.F. First Report of Rhizopus stolonifer causing flower rot of yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa) in China. Plant disease 2024, 108, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shi, G.; Zhou, J.; Tian, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, W.; Xia, X.; Mou, H.; Yang, X. Identification and validation of stem rot disease resistance genes in passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). Hort. Sci. (Prague) 2025, 52, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Sung, K.Y.; Tuan, S.J.; Huang, J.W.; Lin, Y.H.; Huang, T.P. A streptomyces agent for biocontrol of phytophthora blight and its modulation of rhizosphere microbiomes in passion fruit. Plant disease 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Jiménez, J.L.; Montebianco, C.d.B.; Bernardino, M.C.; Barreto-Bergter, E.; Rosa, R.C.C.; Vaslin, M.F.S. Enhancing passion fruit resilience: the role of hariman in mitigating viral damage and boosting productivity in organic farming systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.K. Integrating viral infection and correlation analysis in Passiflora edulis and surrounding weeds to enhance sustainable agriculture in Republic of Korea. Viruses 2025, 17, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicom, B.; et al. 2003. Diseases of passion fruit. Page 413 in: Diseases of Tropical Fruit Crops. R. C. Ploetz, ed. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, U.K.

- Ranallo-Benavidez, T.R.; Jaron, K.S.; Schatz, M.C. GenomeScope 2. 0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servant, N.; Varoquaux, N.; Lajoie, B.R. Viara, E.; Chen, C.; Vert, J.; Heard, E.;Dekker, J.; Barillot, E. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol 2015, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, M.; Aluru, S.; Cheng, H.; Wang, C.; Meyer, C.A.; Yue, F.; Liu, X.S.; Li, H. Fast alignment and preprocessing of chromatin profiles with Chromap. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheenko, A.; Prjibelski, A.; Saveliev, V.; Antipov, D. Gurevich A. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond. Current Protocols 2021, 1, e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 1999, 27, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, J. M.; Hubley, R.; Goubert, C.; Rosen, J.; Clark, A. G.; Feschotte, C.; Smit, A. F. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. PANS 2020, 117(17), 9451–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to Identify Repetitive Elements in Genomic Sequences. Curr Protoc. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.M.; Eddy, S.R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagesen, K.; Hallin, P.; Rødland, E.A.; Stærfeldt, H.H.; Rognes, T.; Ussery, D.W. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, 3100–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanke, M.; Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, W465–W467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoros, W.H.; Pertea, M.; Salzberg, S.L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 2878–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter-Hovhannisyan, V.; Lomsadze, A.; Chernoff, Y.O.; Borodovsky, M. Gene prediction in novel fungal genomes using an ab initio algorithm with unsupervised training. Genome Res 2008, 18, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Zhu, W.; Pertea, M.; Allen, J.E.; Orvis, J.; White, O.; Buell, C.R.; Wortman, J.R. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Bio. 2008, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Forslund, K.; Coelho, L.P.; Szklarczyk, D.; Jensen, L.J.; Mering, C.; Bork, P. Fast Genome-Wide Functional Annotation through Orthology Assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol. Biol. Evol 2017, 34, 8–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Attwood, T.K.; Babbitt, P.C.; Bateman, A.; Bork, P.; Bridge, A.J.; Chang, H.Y.; Dosztányi, Z.; El-Gebali, S.; Fraser, M.; Gough, J.; Haft, D.; Holliday, G.L.; Huang, H.; Huang, X.; Letunic, I.; Lopez, R.; Lu, S.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Mi, H.; Mistry, J.; Natale, D.A.; Necci, M.; Nuka, G.; Orengo, C.A.; Park, Y.; Pesseat, S.; Piovesan, D.; Potter, S.C.; Rawlings, N.D.; Redaschi, N.; Richardson, L.; Rivoire, C.; Sangrador-Vegas, A.; Sigrist, C.; Sillitoe, I.; Smithers, B.; Squizzato, S.; Sutton, G.; Thanki, N.; Thomas, P.D.; Tosatto, S.C.; Wu, C.H.; Xenarios, I.; Yeh, L.S.; Young, S.Y.; Mitchell, A.L. InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 4: 190-199.

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Sønderby, C.K.; Petersen, T.N.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. [CrossRef]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Salvatore, M.; Emanuelsson, O.; Winther, O.; von Heijne, G.; Elofsson, A.; Nielsen, H. Detecting sequence signals in targeting peptides using deep learning. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201900429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperschneider, J.; Dodds, P.N.; Gardiner, D.M.; Singh, K.B.; Taylor, J.M. Improved prediction of fungal effector proteins from secretomes with EffectorP 3.0. Mol. Plant Pathol, 23.

- Stanke, M.; Diekhans, M.; Baertsch, R.; Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke, M.; Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, O.; Kollmar, M.; Stanke, M.; Waack, S. A novel hybrid gene prediction method employing protein multiple sequence alignments, Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 757–763. 27.

- Shen, W.; Sipos, B.; Zhao, L. SeqKit2: a Swiss army knife for sequence and alignment processing. iMeta 2024, 3, e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutierrez, S.; Silla-Martinez, J.M.; Gabaldon, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, D.M.; Aitken, E.A.B.; van Dam, P.; Le, D.P.; Smith, L.J.; Chen, A. De novo long-read assembly and annotation for genomes of two cotton-associated Fusarium oxysporum isolates. Australasian Plant Pathol. 2025, 54, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, D.; Klein, J.; Antonelli, A.; Silvestro, D. raxmlGUI 2.0: A graphical interface and toolkit for phylogenetic analyses using RAxML. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Coutinho, P.M.; Rancurel, C.; Bernard, T.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D233–D238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Naour-Vernet, M.L.; Lahfa, M.; Maidment, J.H.R.; Padilla, A.; Roumestand, C.; de Guillen, K.; Kroj, T.; Césari, S. Structure-guided insights into the biology of fungal effectors. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 1460–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelders, N.C.; Rovenich, H.; Thomma, B.P. Microbiota manipulation through the secretion of effector proteins is fundamental to the wealth of lifestyles in the fungal kingdom. Fems Microbiol Rev. 2022, 46, fuac022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Hu, H.; Wei, Q.; Bao, C.; Yan, Y. Comprehensive Genomic and Proteomic Analysis Identifies Effectors of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melongenae. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Gardiner, D.M.; van Dam, P.; Fu, G.; Ferguson, B.J.; Aitken, E.A.B.; Chen, A. Long-read draft genome sequences of two Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense isolates from banana (Musa spp.). J. Fungi. 2025, 11, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).