1. Introduction

The Conglomerate Theory of Aging delineates how four synergistic reactive species (RS) initiated processes drive aging through the accumulation of self-reinforcing, inexorable molecular damage (Nelson-Goedert, 2025). It provides a framework for understanding physical decline over time by linking each component to the known hallmarks of aging, followed by identifying the lifespan and healthspan amelioration effects of targeted approaches. The Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis extends this perspective by proposing that cancer arises from the same fundamental molecular processes that drive aging but within localized cellular environments and at accelerated rates.

Traditional approaches to cancer focus primarily on downstream cellular and genetic consequences rather than the upstream molecular initiators. Mainstream research and treatment emphasize intervention at the level of tumor cell growth, genetic mutations, and proliferative signaling through avenues that include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and hormonal therapy. These strategies have improved patient survival and disease management considerably; however, they target established cancer rather than thwarting its foundational molecular drivers (Zafar et al., 2025). This downstream perspective overlooks deeper etiological mechanisms, leaving critical gaps in our understanding of cancer's origins. This ultimately limits opportunities to address disease before malignant transformation occurs, thus hindering the discovery of durable prevention protocols or cures.

In contrast, the four core Conglomerate processes—transition metal bioaccumulation, AGE formation, ALE formation, and metal AGE/ALE hybrid complex formation— individually and in tandem produce a cascade of molecular damage that drives the metabolic reprogramming characteristic of malignant cells. One case in point for a mutually reinforcing, autocatalytic oncogenesis is the Warburg effect, as cancer cells' preference for aerobic glycolysis generates excessive methylglyoxal and other reactive carbonyl species that accelerate AGE formation (Antognelli et al., 2018; Rabbani and Thornalley, 2015). Similarly, the elevated RS production in cancer cells drives both metal accumulation and lipid peroxidation, creating a perfect storm of molecular damage that promotes oncogenesis (Klaunig et al., 2010).

Thus, the Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis provides a unifying framework that explains the interconnectedness of seemingly disparate cancer hallmarks, from genomic instability to metabolic reprogramming, through the lens of upstream molecular damage phenomena. By understanding cancer as an accelerated aging process occurring in localized cellular environments, we can develop more targeted and effective therapeutic strategies that address the fundamental drivers of malignancy.

2. Reactive Species Foundation

Multiple forms of reactive species serve as the central initiating factors in the Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis, with cancer cells generating substantially higher RS levels than normal cells through numerous mechanisms, while also developing more readily in such RS exposures. Mitochondrial dysfunction, a hallmark of cancer cells, leads to increased electron leak from the respiratory chain, generating superoxide and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Penta et al., 2001). The hypoxic tumor microenvironment paradoxically increases ROS production through multiple mechanisms, including mitochondrial dysfunction under oxygen-limited conditions and the activation of NADPH oxidases (Chandel et al., 1998; Cairns et al., 2011).

The activation of oncogenes, particularly KRAS and MYC, significantly increases intracellular ROS production through metabolic reprogramming and direct effects on cellular respiration (Weinberg et al., 2010). KRAS-mutated cancer cells demonstrate enhanced oxidative stress through upregulation of glucose metabolism and increased mitochondrial biogenesis, creating a pro-oxidative cellular environment that facilitates further molecular damage. Inflammatory cell infiltration further amplifies ROS generation through the respiratory burst of activated immune cells, creating a cycle of inflammation and oxidative stress that promotes tumor progression (Grivennikov et al., 2010).

ROS-induced DNA damage represents one of the most critical consequences of elevated oxidative stress in cancer. The formation of 8-oxoguanosine, a major DNA oxidation product, leads to G→T transversions that can activate oncogenes or inactivate tumor suppressor genes (Klaunig et al., 2010). Beyond direct DNA damage, ROS also induce replication stress by depleting the dNTP pool and interfering with DNA polymerase function, leading to genomic instability characteristic of cancer cells (Bester et al., 2011).

3. Transition Metal Bioaccumulation in Cancer

The dysregulation of transition metal homeostasis represents a fundamental feature of cancer cells, with iron, copper, and zinc showing noteworthy alterations in malignant tissues. Iron dysregulation is particularly pronounced in cancer, with elevated intracellular iron levels documented across multiple cancer types (Torti and Torti, 2013). Oncogenic KRAS directly regulates iron metabolism by upregulating STEAP3 (ferrireductase) expression and downregulating ferroportin (iron exporter), creating an iron-rich intracellular environment that promotes Fenton chemistry and hydroxyl radical generation (Jiang et al., 2015).

The molecular mechanisms underlying iron accumulation in cancer involve multiple pathways beyond KRAS signaling. Transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) is overexpressed in many cancers, increasing iron uptake from the circulation (Daniels et al., 2012). Simultaneously, ferritin expression is often dysregulated, leading to decreased iron storage capacity and increased labile iron pools that participate in Fenton reactions (Torti and Torti, 2013). The iron-rich environment not only promotes oxidative damage but also supports the high metabolic demands of rapidly dividing cancer cells.

Copper dysregulation in cancer involves both increased uptake and altered intracellular distribution. Oncogenic KRAS enhances copper uptake through macropinocytosis, while also activating copper-dependent signaling pathways including MEK1/MEK2 kinases (Shanbhag et al., 2021). The ATP7A copper transporter is frequently upregulated in cancer cells, providing protection against copper toxicity while maintaining the elevated copper levels necessary for angiogenesis and metastasis (Brady et al., 2014).

Tetrathiomolybdate, a potent copper chelator originally developed for Wilson's disease, has demonstrated significant anticancer efficacy through copper depletion. In clinical trials, tetrathiomolybdate at doses of 100 mg daily effectively reduced circulating endothelial progenitor cells in high-risk breast cancer patients, with 75% achieving copper depletion targets within one month (Brewer et al., 1994). The compound works by forming stable tripartite complexes with serum albumin and copper, rendering the complexed copper unavailable for cellular uptake.

Zinc metabolism shows complex alterations in cancer, with many tumors displaying zinc depletion despite increased zinc transporter expression. The dysregulation of zinc transporters, particularly ZIP1, ZIP4, ZIP6, and ZIP10, leads to altered zinc distribution that compromises antioxidant defense and DNA repair mechanisms (Alzahrani and Taylor, 2025). This zinc dyshomeostasis contributes to genomic instability and compromised tumor suppressor function (Wang et al., 2020).

4. Advanced Glycation End Products in Cancer

The metabolic reprogramming characteristic of cancer cells creates an ideal environment for accelerated AGE formation. The Warburg effect generates high levels of methylglyoxal and other reactive carbonyl species (RCS) that serve as AGE precursors (Antognelli et al., 2018; Rabbani and Thornalley, 2015). Methylglyoxal, the primary precursor to many AGEs, is formed spontaneously from the glycolytic intermediates dihydroxyacetone phosphate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. Cancer cells, with their enhanced glycolytic flux, produce methylglyoxal at rates far exceeding normal cells, thus producing an autocatalytic effect for further cancer development.

The AGE-RAGE (receptor for AGE) signaling axis plays a crucial role in cancer progression. RAGE activation by AGEs triggers multiple oncogenic pathways, including NF-κB, STAT3, and PI3K/AKT, promoting cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis (Nasser et al., 2015). The AGE-RAGE interaction also promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key process in cancer metastasis, through the activation of transcription factors including Snail and Twist (Nasser et al., 2015).

Clinical evidence supports the involvement of AGEs in cancer progression. Dietary AGE intake has been associated with increased breast cancer risk, with high AGE consumption showing elevated risk ratios for overall breast cancer development (Omofuma et al., 2020). AGE levels are consistently elevated in cancer patients compared to healthy controls, and higher AGE levels correlate with advanced cancer stages and poor prognosis (Nasser et al., 2015).

5. Advanced Lipoxidation End Products in Cancer

Lipid peroxidation and ALE formation represent critical components of the Conglomerate damage process in cancer following genesis of reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Elevated RNS and ROS levels in cancer cells drive extensive lipid peroxidation, generating reactive aldehydes including 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), malondialdehyde (MDA), and acrolein that form ALEs through protein and DNA adduction (Gentile et al., 2017). These ALEs promote oncogenesis at low levels while inducing cancer cell death at substantially high concentrations.

4-HNE, the most studied ALE, forms DNA adducts that cause G→T transversions, particularly at codon 249 of the p53 gene, a mutation hotspot in hepatocellular carcinoma and lung cancer (Gentile et al., 2017). The formation of 4-HNE-DNA adducts has been documented in vivo following lipid peroxidation stimulation, with significant increases observed in liver cancer models (Hu et al., 2002; Nair et al., 2005). Beyond DNA damage, 4-HNE also impairs DNA repair mechanisms by blocking the re-ligation step in base excision repair, allowing more mutations to accumulate.

MDA, another major ALE, forms M1G adducts with DNA that are highly mutagenic and have been detected in human liver, breast, and laryngeal cancer tissues (Marnett, 1999). Normal esophageal epithelial tissues exhibited significantly lower levels of M1G adducts compared to esophageal cancer tissues, with median levels of 3.4 per 10^8 nucleotides in normal tissue versus 14.1 per 10^8 nucleotides in cancer tissue. These adducts can induce large deletions and insertions in DNA, contributing to the genomic instability characteristic of cancer.

Advanced lipoxidation end-products have also been identified as RAGE binders, with ALEs formed from lipid peroxidation-derived reactive carbonyl species showing significant binding affinity to the VC1 domain of RAGE. This binding capability allows ALEs to activate similar oncogenic pathways as AGEs, creating additional mechanisms for tumor promotion through RAGE-mediated signaling (Singh et al., 2001).

6. Hybrid Complex Formation and Crosslinking

The formation of metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrid complexes has been substantiated by a considerable body of in vitro research, which demonstrates that AGEs and ALEs can avidly chelate transition metals such as iron and copper, resulting in structurally unique hybrid adducts (Singh et al., 2001; Rabbani & Thornalley, 2015). These metal-containing complexes exhibit a marked resistance to proteolytic degradation and are potent in catalyzing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through redox cycling mechanisms in cell-free and cell-based systems (Singh et al., 2001). This amplified ROS generation exacerbates oxidative molecular damage, creating damaging feedback loops relevant to carcinogenesis (Klaunig et al., 2010). Although direct isolation of these hybrids from cancer tissues remains to be conclusively achieved, an excess of both AGEs/ALEs and transition metals has consistently been found in tumor samples (Coradduzza et al., 2024). Their mutual interaction has been demonstrated under physiological conditions (Singh, 2001).

These complexes also facilitate extensive protein crosslinking, contributing to the accumulation of highly crosslinked, protease-resistant material in both cellular and extracellular compartments, a feature observed in both aging and malignancy (Singh et al., 2001). Non-enzymatic crosslinking by metal-AGE and metal-ALE complexes may work in parallel with enzymatic pathways, such as those mediated by lysyl oxidase (LOX) and lysyl hydroxylase (LH), to increase collagen crosslink density in the extracellular matrix (Maller et al., 2021; Erler et al., 2009). The resultant stiffening of the tumor microenvironment, driven by both enzymatic and metal-catalyzed non-enzymatic crosslinks, would have profound consequences for cancer progression, as increased extracellular matrix rigidity is directly linked to enhanced tumor cell invasion, proliferation, and metastatic potential (Maller et al., 2021; Rubashkin et al., 2014). Empirical studies show that LOX inhibition can reduce the proliferative and invasive capacity of cancer cells by decreasing collagen crosslinking and matrix stiffness, providing further evidence for the importance of pathological crosslinking in tumor biology (Maller et al., 2021). These findings collectively suggest that metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrid complexes are contributors to the pathological remodeling of the tumor microenvironment and synergize with enzymatic crosslinking processes in cancer progression (Singh et al., 2001; Gentile et al., 2017; Maller et al., 2021).

7. Tumor Microenvironment and Conglomerate Effects

7.1. Hypoxia and ROS Generation

The hypoxic tumor microenvironment creates an ideal environment for conglomerate damage processes. Hypoxic tumor regions experience uneven oxygen distribution with severe hypoxia in the core due to poor vascularization and high metabolic oxygen consumption. Paradoxically, hypoxic conditions increase ROS production through multiple mechanisms, including mitochondrial dysfunction, NADPH oxidase activation, and xanthine oxidase upregulation (Chandel et al., 1998).

During hypoxia, the electron transport chain in mitochondria becomes disrupted, as oxygen availability is insufficient to accept electrons. This disruption causes electron leakage, leading to the formation of superoxide. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), which are the master regulators of the hypoxia response, also upregulate genes encoding ROS-generating enzymes such as NADPH oxidases (NOX1 and NOX4), which transfer electrons from NADPH to oxygen (Semenza, 2010).

HIF-1α stabilization under hypoxic conditions directly promotes glycolytic metabolism, increasing methylglyoxal production and AGE formation (Semenza, 2010). The hypoxic environment also promotes iron accumulation through the upregulation of iron import proteins and the downregulation of iron export mechanisms. This iron accumulation, combined with increased ROS production, creates ideal conditions for Fenton chemistry and hydroxyl radical generation.

Hypoxia changes mediated by HIF-1α and elevated ROS levels enhance the differentiation, recruitment, survival, and immunosuppressive functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), fostering a tumor-supportive microenvironment that promotes cancer progression, immune evasion, and therapy resistance. ROS stabilize HIFs, driving processes such as disorganized angiogenesis and the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and MDSCs (Grivennikov et al., 2010).

7.2. Inflammatory Microenvironment

Chronic inflammation within the tumor microenvironment significantly amplifies conglomerate damage processes. Inflammatory cells, particularly macrophages and neutrophils, generate substantial quantities of ROS through the respiratory burst mechanism, contributing to the overall oxidative burden (Grivennikov et al., 2010). Activated immune cells release reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen intermediates, leading to DNA damage, genomic instability, and epigenetic modifications that elevate mutation rates.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) play a particularly important role in metal dysregulation within tumors. TAMs release iron through ferroportin downregulation and promote copper accumulation through ceruloplasmin secretion (Recalcati et al., 2010). The inflammatory microenvironment also promotes AGE formation through the release of inflammatory mediators that enhance glycolytic metabolism and reactive carbonyl species generation.

The inflammatory-oxidative cycle, in turn, creates a self-perpetuating environment that promotes all aspects of conglomerate damage. Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-23 are produced by tumor-associated immune cells, including macrophages and T cells recruited to the tumor site in response to signals from the tumor and surrounding stromal cells. These cytokines primarily promote tumorigenesis by activating AP-1 and NF-κB transcription factors, which regulate genes essential for inflammation, immune evasion, survival, and metastasis (Reuter et al., 2010).

Inflammatory mediators promote ROS generation, which in turn activates inflammatory pathways through NF-κB and other redox-sensitive transcription factors (Morgan and Liu, 2011; Reuter et al., 2010). This cycle continues throughout tumor progression, creating an environment that favors cancer cell survival and metastasis (Grivennikov et al., 2010). STAT3 activation upregulates the production of IL-6 and other cytokines that promote tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, recruiting additional immune cells and perpetuating a cycle of chronic inflammation that drives tumor growth (Yu et al., 2009; Fu et al., 2023).

7.3. Neutrophils

Recent studies position neutrophils as key mediators in tumor necrosis, vascular occlusion, and metastasis. Notably, the September 2025 publication by Adrover et al. demonstrated that neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) aggregate within tumor vasculature, leading to vessel blockage, localized hypoxia, and necrosis, and further supporting metastatic progression. Inhibition of NET formation in models substantially reduced both necrosis and metastasis (Adrover et al., 2025; Estivill & Obenauf, 2025).

Within the Conglomerate Theory framework, metal bioaccumulation, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs) each act through neutrophil pathways to escalate tumor progression independently. Elevated metals such as iron and copper generate oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment, which can directly promote neutrophil recruitment and NET formation (Cheng et al., 2022). AGEs activate neutrophils via RAGE-dependent signaling and inflammatory responses. RAGE has been shown to enhance autophagy and NET formation, and increased AGE-RAGE activity is linked to tumor progression (Boone et al., 2015). ALEs also bind RAGE and are prominent in tumor and inflamed tissue, while RAGE activation by both AGEs and ALEs fosters ROS production and inflammatory signaling, supporting a pro-tumor microenvironment (Mol et al., 2019).

Together, these damaging byproducts foster a tumor microenvironment that increases neutrophil activation and NET-dependent processes, reinforcing the destructive and metastatic potential of cancer through innate immune mechanisms.

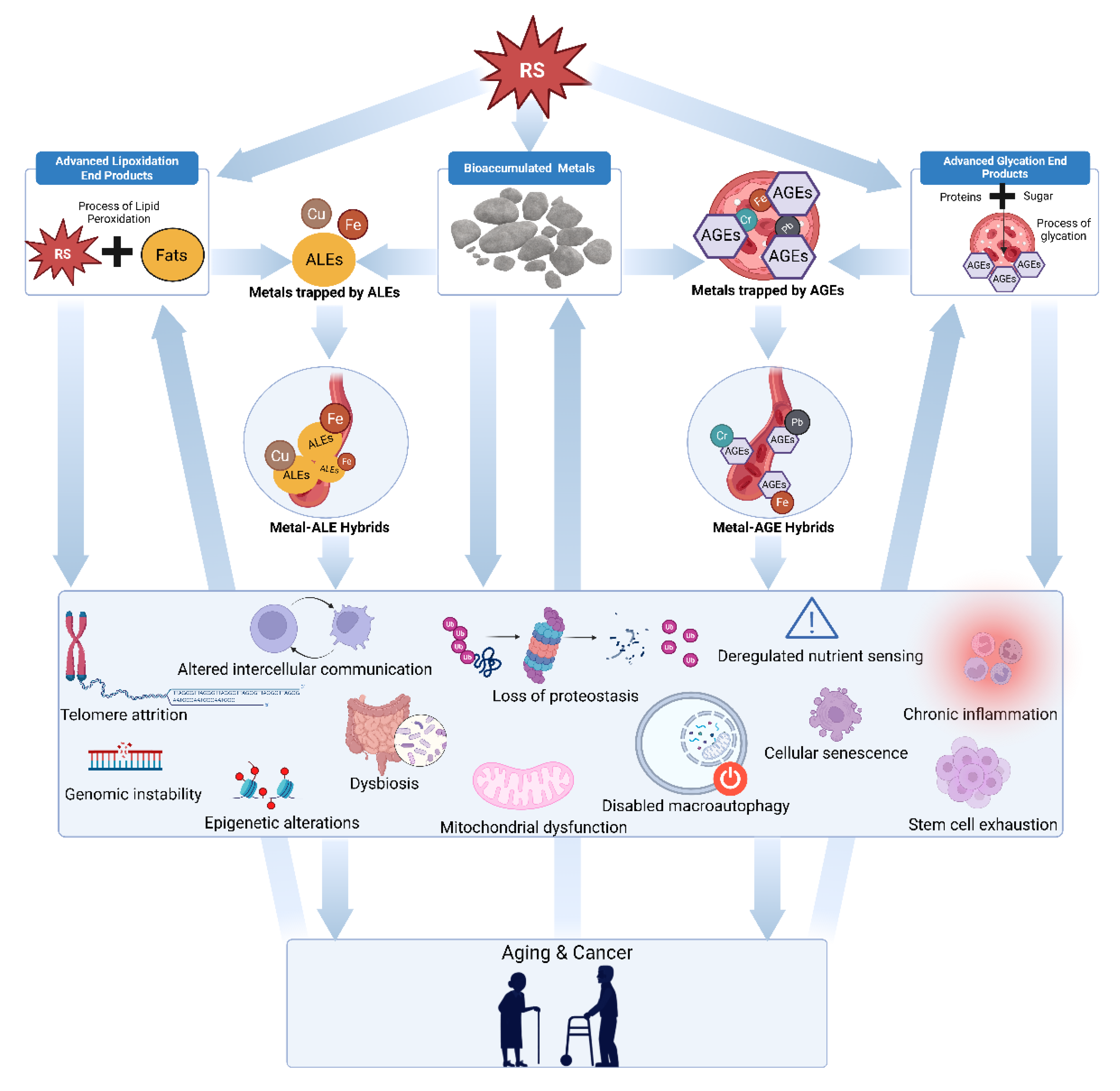

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis. The arrows depict proposed causal pathways, beginning with damage caused by diverse reactive species that generate advanced glycation end products, accumulated metals, advanced lipoxidation end products, and hybrid metal AGE/ALE compounds. These entities collectively trigger various cancers and aging through synergistic and autocatalytic mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis. The arrows depict proposed causal pathways, beginning with damage caused by diverse reactive species that generate advanced glycation end products, accumulated metals, advanced lipoxidation end products, and hybrid metal AGE/ALE compounds. These entities collectively trigger various cancers and aging through synergistic and autocatalytic mechanisms.

8. Therapeutic Implications and Clinical Applications

The Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis suggests that effective cancer therapies require simultaneous targeting of multiple molecular damage processes that correspond with systemic aging. This multi-target approach recognizes that the four conglomerate processes are interconnected and mutually reinforcing, making single-target interventions less effective than combination strategies.

8.1. Metal Chelation Therapy

Metal chelation represents a promising approach for reducing the catalytic metal burden that drives conglomerate damage. Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) provides unique defense as a dual water- and fat-soluble metal chelator. Doses ranging from 50–600 mg/day have been employed in various cancer-related contexts (Bast & Haenen, 2013). In mice bearing Ehrlich ascites carcinoma, 50 mg/kg of ALA reduced tumor volume and viability while enhancing survival and systemic antioxidant defenses (Al Abdan, 2012).

ALA has also demonstrated chemopotentiating properties. In MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, ALA inhibited migration and invasion through suppression of TGFβ signaling (Tripathy et al., 2018). In thyroid cancer models, ALA inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion via suppression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Jeon et al., 2016). Given its unique ability to traverse the blood brain barrier (BBB) among chelators, it has considerable prospects in brain cancers.

Deferasirox, an oral iron chelator used to treat iron overload, has also demonstrated significant anti-tumor effects in numerous in vitro and in vivo studies. Deferasirox at standard doses of 20–40 mg/kg daily has shown antiproliferative activity against pancreatic cancer cells, with combination therapy using deferasirox plus gemcitabine showing enhanced anticancer effects through ribonucleotide reductase activity suppression (Shinoda et al., 2018). Iron chelation therapy with deferasirox operates through multiple mechanisms beyond simple iron depletion. Mitochondrially targeted deferasirox depletes cells of biologically active iron, as evidenced by decreases in iron-sulfur cluster and heme-containing proteins, while also depleting the major cellular antioxidant glutathione and quenches lipid peroxidation (Jadhav et al., 2024; Martin-Sanchez et al., 2017; Martelli & Puccio, 2014). This dual mechanism harnesses the dual nature of iron in a single molecule to combat cancer through both iron deprivation and toxic lipid peroxide production via redox activity Jadhav et al., 2024; Martin-Sanchez et al., 2017; Martelli & Puccio, 2014).

Tetrathiomolybdate represents the most clinically advanced copper chelation therapy for cancer. Clinical trials using tetrathiomolybdate at 100 mg daily to maintain ceruloplasmin levels below 17 mg/dL have demonstrated promising results in high-risk breast cancer patients (Chan et al., 2017). The compound works by forming stable tripartite complexes with serum albumin and copper, rendering the complexed copper unavailable for cellular uptake, and has shown excellent safety profiles with minimal side effects beyond mild hematologic toxicity (Jain et al., 2013).

Additionally, clinical evidence supporting copper chelation in cancer comes from multiple sources. In phase I/II trials of advanced and metastatic cancers, tetrathiomolybdate treatment showed freedom from progression averaging 11 months, with some individual results proving considerable (Chan et al., 2017; Jain et al., 2013). The copper-depleting agent completely prevented the development of visible mammary cancers in Her2/neu mice genetically programmed to develop breast cancer, although avascular microscopic clusters of cancer cells were present in the breasts of treated animals (Pan et al., 2002).

8.2. Anti-Glycation Approaches

Targeting AGE formation requires interventions that either reduce AGE precursor formation or enhance AGE clearance. Aminoguanidine has been extensively studied for its ability to trap reactive carbonyl intermediates in the Maillard reaction (Brownlee et al., 1986). Clinical dosing for aminoguanidine in preclinical animal studies typically ranges from 1–4 mg/mL in drinking water, with 2–4 mg/mL showing significant antitumor effects, including an increase in tumor volume doubling time from 7.8 days in controls to 10.0–11.1 days in treated groups.

L-carnosine inhibits AGEs via the neutralization of reactive carbonyl species (RCS), contributing to its anticancer properties. Cell culture studies have demonstrated carnosine’s antineoplastic effects at concentrations ranging from 20–200 mM, including reduced viability, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of cancer cell adhesion, migration, invasion, and proliferation (Iovine et al., 2012; Stuerenburg and Kunze, 1999). The compound demonstrates variable IC50 values across different cancer cell lines, such as 165 mM for A2780, 125 mM for OVCAR-3, and 485 mM for SKOV-3 ovarian carcinoma cells (Turner et al., 2021).

Animal studies with carnosine have shown promising results at clinically relevant doses. In nude mice bearing human breast cancer xenografts, treatment with carnosine reduced tumor volume by approximately 50–60% with free carnosine, and by 70–80% with nanoparticle formulations. This was accompanied by a greater than 50% decrease in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and cyclin D1 expression in tumors. Apoptosis, indicated by caspase 3 positive cells, increased about twofold in treated animals. There was no systemic toxicity or observable weight loss in the treated animals. These results confirm carnosine’s chemopreventive potential in breast cancer models and support its further study for therapeutic applications (Maugeri et al., 2023).

Benfotiamine has demonstrated multiple anti-cancer activities at the cellular level. Thiamine derivatives, including benfotiamine, suppress breast cancer cell line proliferation, promote apoptosis via caspase-3 activation, and regulate proteins essential for cell survival and inflammation (Ciaciuch O'Neill et al., AACR Abstract 7311, 2024). High-dose thiamine and benfotiamine reduce cell viability in human and mouse cancer cell lines by 25–50%, with effects comparable to the metabolic inhibitor dichloroacetate (Hanberry et al., 2014). Notably, 5 mM benfotiamine reduced proliferation of MCF-7 and HCT-116 cancer cell lines by approximately 40% after 72 hours and induced caspase activation and cell cycle disruption (Hanberry et al., 2014). The mechanism appears to involve benfotiamine's action as a thiamine mimetic, modulating transketolase activity and reducing cancer cell metabolic flexibility (Jonus et al., 2020). Manipulating thiamine metabolism this way disrupts the pentose phosphate pathway in cancer cells, cutting off growth and proliferation signals (Zastre et al., 2013). Benfotiamine also exhibits direct antioxidative capacity and prevents DNA damage in vitro, which adds another layer of potential benefit in cancer therapy (Schmid et al., 2008).

8.3. Anti-Lipoxidation Approaches

Lycopene serves as a potent anti-lipoxidation agent with specific anti-cancer properties. Clinical evidence supports lycopene's anti-cancer effects across multiple types. In prostate cancer prevention, meta-analyses report that each 2 mg/day increase in lycopene intake is associated with a ~1% decrease in risk. A pooled analysis showed that high dietary and plasma lycopene levels were associated with significantly reduced risks of prostate cancer, with relative risks of 0.88 for both dietary and circulating lycopene (95% CI, 0.79–0.98 and 0.78–0.98, respectively) (Chen et al., 2015).

Clinical studies demonstrate optimal efficacy at doses of 15–30 mg daily for cancer prevention and treatment (Chen et al., 2015). The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommends a maximum safe intake of 0.5 mg/kg body weight/day, with several clinical trials demonstrating safety at doses up to 45 mg/day for six months. Gamma-tocopherol also offers superior antilipoxidation protection due to its capacity to neutralize reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Gamma-tocopherol also inhibited MCP-1 expression and COX-2 activity, contributing to anti-inflammatory effects critical in carcinogenesis (Campbell et al., 2006).

Gamma-tocopherol shows greater anti-cancer activity than alpha-tocopherol in breast and prostate cancer models, highlighting the specific biokinetics of this form of vitamin E. In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, gamma-tocopherol at 10–100 µM inhibited estrogen-stimulated proliferation in a dose-dependent fashion, with alpha-tocopherol showing little or no effect (Campbell et al., 2006). Additionally, gamma-tocopherol induced apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells via mitochondria-mediated pathways, including cytochrome c release, caspase-9 activation, and PARP cleavage (Jiang et al., 2004).

8.4. Reactive Species Modulation Strategies

The role of reactive species (RS) in cancer requires approaches that both protect normal cells from damage and, when appropriate, modulate RS to influence cancer cell behavior (De Flora et al., 2001).

8.4.1. N-Acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) acts both as a direct ROS scavenger and by enhancing intracellular glutathione synthesis. Extensive experimental and clinical data demonstrate NAC’s safety, even at high and long-term doses, and support its use in chemoprevention protocols (De Flora et al., 2001). Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that NAC reduces DNA damage, inhibits carcinogen-induced genotoxicity, and modulates processes such as cell cycle progression, inflammation, and apoptosis. These protective effects have been observed across varied animal models and clinical trials, primarily involving populations at elevated risk for cancer (De Flora et al., 2001).

Recent large-scale, population-based evidence further supports NAC’s anticancer potential. In a comprehensive cohort of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), long-term NAC use (≥28 cumulative defined daily doses per year) was associated with a significantly decreased risk of developing several cancers, including breast, prostate, gynecologic, hepatocellular, and colorectal cancers (Yang et al., 2025). The risk reductions were dose-dependent, and the benefits were most pronounced for non-lung cancer types, highlighting NAC’s chemopreventive relevance for high-risk populations (Yang et al., 2025). Together, animal and human studies demonstrate NAC’s diverse mechanisms of action and support its ongoing investigation as a safe, effective agent for cancer chemoprevention.

8.4.2. Glycine

Glycine has emerged as a noteworthy candidate in anti-cancer therapy, with support from multiple preclinical studies. In animal models, dietary glycine supplementation reduced tumor volumes by approximately 50–75% in B16 melanoma mouse models, relative to controls (Rose et al., 1999; Mikalauskas et al., 2019). At the time of necropsy in the melanoma experiments, tumors from glycine-fed mice weighed nearly 65% less than those from control-fed animals, and the number of tumor arteries was reduced by 70% (Rose et al., 1999). These effects appear to stem from inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and microvascular density, rather than direct cytotoxicity, as glycine supplementation did not alter cancer cell proliferation in vitro, body weight, or general animal health (Rose et al., 1999; Mikalauskas et al., 2019). In vitro, glycine inhibits endothelial cell migration and proliferation while exhibiting little to no direct effect on tumor cell growth (Yamashina et al., 2007; Rose et al., 1999).

8.4.3. Selenium

Selenium has been extensively investigated as a potential anti-cancer agent, with mechanistic, preclinical, and human data yielding a nuanced picture. In animal studies, multiple forms of selenium, including selenite, selenomethionine, and selenium-enriched yeast, have been shown to protect against carcinogenesis and reduce tumor incidence across numerous models, with one meta-analysis finding a pooled odds ratio (OR) for cancer risk of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.69–0.82) in animals or populations with higher selenium exposure (Combs and Gray 1998; Ip 1986; Cai et al., 2016; Vinceti et al., 2018). In vitro, selenium compounds often induce apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and growth inhibition in a variety of cancer cell lines, partly through redox modulation and activation of tumor suppressor p53, and by downregulating oncogenes such as c-myc (Zhong and Oberley, 2001; Rudolf et al., 2008). In humans, early trials such as the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer (NPC) study reported that selenium supplementation in selenium-deficient people reduced total cancer incidence (Clark et al., 1996); however, later large randomized controlled trials (SELECT) in generally selenium-replete populations failed to replicate these benefits for prostate or total cancer risk (Lippman et al., 2009; Vinceti et al., 2018). Meta-analyses of observational studies suggest an approximate 20–25% reduced cancer risk for subjects with higher serum or plasma selenium, though the association is U-shaped and there is evidence that excessive supplementation may increase risks of certain cancers or other adverse effects (Filippini et al., 2025; Cai et al., 2016). Recent early-phase clinical studies of sodium selenite in advanced cancer have found it to be safe and potentially synergistic with radiation or chemotherapy, without major systemic toxicity up to 33 mg single dose or 10.2 mg/m^2 in cycle therapy (He et al., 2025). Altogether, selenium’s anti-cancer effects appear most pronounced in deficiency states and are dependent on both the chemical form and baseline selenium status, underscoring the importance of precision and context in its therapeutic use.

9. Clinical Translation and Future Directions

9.1. Biomarker Development

The Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis provides a framework for developing novel biomarkers that reflect the underlying molecular damage processes driving cancer progression. These biomarkers could serve multiple purposes: early detection, risk stratification, treatment monitoring, and prognosis assessment.

Potential metal dysregulation biomarkers include serum iron/copper/zinc ratios, labile iron pool measurements, ferroportin and transferrin receptor expression, and ceruloplasmin and metallothionein levels. Clinical studies have demonstrated that these markers correlate with cancer risk and progression, with elevated iron levels and altered copper metabolism consistently observed across multiple cancer types (Wu et al., 2004).

AGE/ALE biomarkers encompass fluorescent levels in serum and tissues, specific AGE compounds such as carboxymethyl lysine and methylglyoxal derivatives, AGE-RAGE activation markers, and lipid peroxidation products including 4-HNE and MDA adducts. Clinical evidence shows these markers are elevated in cancer patients compared to healthy controls and correlate with cancer stage and prognosis (Rašić et al., 2018; van Heijst et al., 2005).

Crosslinking biomarkers involve collagen crosslink analysis in tumor samples, LOX and lysyl hydroxylase activity measurements, matrix stiffness measurements, and extracellular matrix composition analysis. Studies demonstrate that collagen crosslinking correlates with tumor aggressiveness and patient outcomes across multiple cancer types (Yu et al., 2019; Levental et al., 2009; Xiao and Ge, 2012).

9.2. Therapeutic Development

The multi-target nature of the Conglomerate Theory suggests that combination therapies addressing multiple damage processes simultaneously will be more effective than single-target approaches. This has important implications for drug development and clinical trial design.

Combination therapy strategies should focus on metal chelation plus AGE and ALE inhibition, and reactive species inhibition to slow or eliminate these cascade effects.

Personalized medicine applications include genetic profiling for metal metabolism variants, metabolic profiling for AGE formation propensity, tumor microenvironment analysis for optimal intervention selection, and biomarker-guided therapy adjustment. These approaches recognize that individual variations in conglomerate damage processes may require tailored therapeutic strategies.

9.3. Resistance Mechanisms and Therapeutic Adaptation

Cancer cells may develop resistance to anti-conglomerate therapies through multiple mechanisms, including enhanced antioxidant defenses, altered metal homeostasis, and changes in metabolic programming. Understanding these resistance mechanisms is crucial for developing effective long-term treatment strategies. Potential resistance mechanisms include upregulation of antioxidant enzymes, enhanced metal efflux mechanisms, metabolic reprogramming to reduce AGE formation, and increased DNA repair capacity. Clinical monitoring for these changes will be essential for early detection and intervention.

Strategies to overcome resistance involve sequential targeting of different conglomerate processes, combination with agents that inhibit resistance pathways, pulsed therapy protocols to prevent adaptation, and monitoring with early intervention for resistance development. These approaches recognize the dynamic nature of cancer cell adaptation and the need for flexible therapeutic strategies.

10. Conclusions

The Conglomerate Theory of Oncogenesis reframes cancer as an accelerated aging process driven by four interconnected molecular damage pathways resulting from RS: metal bioaccumulation, AGE formation, ALE formation, and metal AGE/ALE hybrids. These processes are mutually reinforcing, creating self-perpetuating cycles that drive cancer progression. Unlike conventional approaches that target downstream cellular consequences, this theory addresses upstream molecular causes, providing a mechanistic framework for multi-target therapeutic intervention. Individual variations in metal metabolism, antioxidant capacity, and metabolic programming allow for personalized treatment strategies that recognize cancer heterogeneity at its molecular roots. The comprehensive protocol outlined here represents the first systematic attempt to target all four damage processes simultaneously, using agents with decades of safety data: alpha-lipoic acid for metal chelation, L-carnosine and benfotiamine for AGE inhibition, gamma-tocopherol and lycopene for ALE inhibition, plus N-acetylcysteine and selenium for reactive species quenching.

This paradigm shift to addressing root causes opens new avenues for cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment. Clinical studies demonstrate that combination approaches targeting multiple damage pathways outperform single-agent therapies, validating the theory's core premise that effective cancer treatment requires simultaneous intervention at multiple molecular levels. Future research must focus on validating multi-target protocols through carefully designed clinical trials, developing biomarkers that reflect upstream damage processes, and understanding resistance mechanisms. The journey from theory to clinical application will require continued refinement, but the foundation is promising. By targeting all four molecular damage processes at once, this approach offers hope for more effective and less toxic cancer care, potentially improving patient outcomes while addressing the fundamental molecular processes that drive oncogenesis.

Author Contributions

The author is solely responsible for all aspects of this work, including theory development, manuscript preparation, and analysis.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Chidi Nwekwo, Near East University, for his expert contributions as a biomedical illustrator in creating the schematic diagram used to demonstrate our theory of aging. Dr. Nwekwo's skillful visual interpretation of the major concepts presented in this work greatly enhanced the clarity and accessibility of our theoretical framework.

Funding

No funding was received to support this work.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Adrover, J. M., Han, X., Sun, L., Fujii, T., Sivetz, N., Daßler-Plenker, J., Evans, C., Peters, J., He, X. Y., Cannon, C. D., Ho, W. J., Raptis, G., Powers, R. S., & Egeblad, M. (2025). Neutrophils drive vascular occlusion, tumour necrosis and metastasis. Nature, 645(8080), 484–495. [CrossRef]

- Al Abdan M. (2012). Alfa-lipoic acid controls tumor growth and modulates hepatic redox state in Ehrlich-ascites-carcinoma-bearing mice. TheScientificWorldJournal, 2012, 509838. [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A. M., & Taylor, K. M. (2025). Zinc Transporters of the LIV-1 Subfamily in Various Cancers: Molecular Insights and Research Priorities for Saudi Arabia. International journal of molecular sciences, 26(16), 8080. [CrossRef]

- Antognelli, C., Cecchetti, R., Riuzzi, F., Peirce, M. J., & Talesa, V. N. (2018). Glyoxalase 1 sustains the metastatic phenotype of prostate cancer cells via EMT control. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 22(5), 2865–2883. [CrossRef]

- Bast, A., & Haenen, G. R. (2013). The toxicity of antioxidants and their metabolites. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 37(3), 1139-1146.

- Bester, A. C., Roniger, M., Oren, Y. S., Im, M. M., Sarni, D., Chaoat, M., Bensimon, A., Zamir, G., Shewach, D. S., & Kerem, B. (2011). Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell, 145(3), 435-446. [CrossRef]

- Boone, B. A., Orlichenko, L., Schapiro, N. E., Loughran, P., Gianfrate, G. C., Ellis, J. T., Singhi, A. D., Kang, R., Tang, D., Lotze, M. T., & Zeh, H. J. (2015). The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) enhances autophagy and neutrophil extracellular traps in pancreatic cancer. Cancer gene therapy, 22(6), 326–334. [CrossRef]

- Brady, D. C., Crowe, M. S., Turski, M. L., Hobbs, G. A., Yao, X., Chaikuad, A., Knapp, S., Xiao, K., Campbell, S. L., Thiele, D. J., & Counter, C. M. (2014). Copper is required for oncogenic BRAF signalling and tumorigenesis. Nature, 509(7501), 492–496. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G. J., Dick, R. D., Johnson, V., Wang, Y., Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan, V., Kluin, K., Fink, J. K., & Aisen, A. (1994). Treatment of Wilson's disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate. I. Initial therapy in 17 neurologically affected patients. Archives of neurology, 51(6), 545–554. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M., Vlassara, H., Kooney, A., Ulrich, P., & Cerami, A. (1986). Aminoguanidine prevents diabetes-induced arterial wall protein cross-linking. Science (New York, N.Y.), 232(4758), 1629–1632. [CrossRef]

- Bruns, I., Cadeddu, R. P., Bruns, C. J., Schulte, N., Kleeff, J., Reng, M.,... & Büchler, M. W. (2011). Glycine as a potent anti-angiogenic nutrient for tumor growth. Amino Acids, 40(2), 717-728.

- Cai, X., Wang, C., Yu, W., Fan, W., Wang, S., Shen, Y.,... & Wang, F. (2016). Selenium exposure and cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis and meta-regression. Scientific Reports, 6, 19213. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R. A., Harris, I. S., & Mak, T. W. (2011). Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature reviews. Cancer, 11(2), 85–95.

- Campbell, S. E., Stone, W. L., Lee, S., Whaley, S., Yang, H., Qui, M., Goforth, P., Sherman, D., McHaffie, D., & Krishnan, K. (2006). Comparative effects of RRR-alpha- and RRR-gamma-tocopherol on proliferation and apoptosis in human colon cancer cell lines. BMC cancer, 6, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chan, N., Willis, A., Kornhauser, N., Ward, M. M., Lee, S. B., Nackos, E., Seo, B. R., Chuang, E., Cigler, T., Moore, A., Donovan, D., Vallee Cobham, M., Fitzpatrick, V., Schneider, S., Wiener, A., Guillaume-Abraham, J., Aljom, E., Zelkowitz, R., Warren, J. D., Lane, M. E., … Vahdat, L. (2017). Influencing the Tumor Microenvironment: A Phase II Study of Copper Depletion Using Tetrathiomolybdate in Patients with Breast Cancer at High Risk for Recurrence and in Preclinical Models of Lung Metastases. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 23(3), 666–676. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N. S., Maltepe, E., Goldwasser, E., Mathieu, C. E., Simon, M. C., & Schumacker, P. T. (1998). Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(20), 11715–11720. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., Zhang, W., Wang, X., Zhao, K., Negi, D. S., Zhuo, L., Qi, M., Wang, X., & Zhang, X. (2015). Lycopene and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine, 94(33), e1260. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F., Peng, G., Lu, Y., & Chen, H. (2022). Relationship between copper and immunity: The potential role of copper in tumor immunity. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 1019153. [CrossRef]

- Ciaciuch O'Neill, C., Langmead, A. P., & Ramana, K. V. (2024). Lipid soluble vitamin B1 derivatives, benfotiamine and fursultiamine, prevent breast cancer cells growth [Abstract 7311]. Cancer Research, 84(Suppl. 6), 7311.

- Clark, L. C., Combs, G. F., Turnbull, B. W., Slate, E. H., Chalker, D. K., Chow, J.,... & Graham, G. F. (1996). Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 276(24), 1957-1963.

- Combs, G. F., Jr, & Gray, W. P. (1998). Chemopreventive agents: selenium. Pharmacology & therapeutics, 79(3), 179–192. [CrossRef]

- Coradduzza, D., Congiargiu, A., Azara, E., Mammani, I. M. A., De Miglio, M. R., Zinellu, A., Carru, C., & Medici, S. (2024). Heavy metals in biological samples of cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Biometals : an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine, 37(4), 803–817. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T. R., Bernabeu, E., Rodríguez, J. A., Patel, S., Kozman, M., Chiappetta, D. A., Holler, E., Ljubimova, J. Y., Helguera, G., & Penichet, M. L. (2012). The transferrin receptor and the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents against cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1820(3), 291–317. [CrossRef]

- De Flora, S., Izzotti, A., D'Agostini, F., Balansky, R. M., Noonan, D., & Albini, A. (2001). Multiple points of intervention in the prevention of cancer and other mutation-related diseases. Mutation research, 480-481, 9–22. [CrossRef]

- Erler, J. T., Bennewith, K. L., Cox, T. R., Lang, G., Bird, D., Koong, A., Le, Q. T., & Giaccia, A. J. (2009). Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer cell, 15(1), 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Estivill, G., & Obenauf, A. C. (2025). Trio fatale: Neutrophils, NETs, and necrosis. Immunity, 58(9), 2154–2156. [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, D., & Jain, R. K. (2007). Tumor microvasculature and microenvironment: targets for anti-angiogenesis and normalization. Microvascular Research, 74(2-3), 72-84. [CrossRef]

- Filippini, T., Mazzoli, R., Wise, L. A., Cho, E., & Vinceti, M. (2025). Selenium exposure and risk of skin cancer: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiologic evidence. Journal of trace elements in medicine and biology : organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements (GMS), 90, 127693. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., Hou, X., Dong, L., & Hou, W. (2023). Roles of STAT3 in the pathogenesis and treatment of glioblastoma. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 11, 1098482. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, F., Arcaro, A., Pizzimenti, S., Daga, M., Cetrangolo, G. P., Dianzani, C., Lepore, A., Graf, M., Ames, P. R. J., & Barrera, G. (2017). DNA damage by lipid peroxidation products: implications in cancer, inflammation and autoimmunity. AIMS genetics, 4(2), 103–137. [CrossRef]

- Gharieb, S. B., Abu-Elzeet, H. A., Al Khateeb, T. N., Kamel, S. M., & Abou El-Ella, R. (2021). Antitumor effects of selenium: A review of preclinical and clinical studies. Frontiers in Oncology, 11, 1490740.

- Giovannucci, E. (2005). Tomatoes, tomato-based products, lycopene, and cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 97(4), 317-331. [CrossRef]

- Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R., & Karin, M. (2010). Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell, 140(6), 883–899.

- Hanberry, B. S., Berger, R., & Zastre, J. A. (2014). High-dose vitamin B1 reduces proliferation in cancer cell lines analogous to dichloroacetate. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology, 73(3), 585–594. [CrossRef]

- He, L., Zhang, L., Peng, Y., & He, Z. (2025). Selenium in cancer management: exploring the therapeutic potential. Frontiers in oncology, 14, 1490740. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Feng, Z., Eveleigh, J., Iyer, G., Pan, J., Amin, S., Chung, F. L., & Tang, M. S. (2002). The major lipid peroxidation product, trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, preferentially forms DNA adducts at codon 249 of human p53 gene, a unique mutational hotspot in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis, 23(11), 1781–1789. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B., Shin, S. S., Song, J. H., Choi, Y. H., Kim, W. J., & Moon, S. K. (2019). Carnosine exerts antitumor activity against bladder cancers in vitro and in vivo via suppression of angiogenesis. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry, 74, 108230. [CrossRef]

- Iovine, B., Iannella, M. L., Nocella, F., Pricolo, M. R., & Bevilacqua, M. A. (2012). Carnosine inhibits KRAS-mediated HCT116 proliferation by affecting ATP and ROS production. Cancer letters, 315(2), 122–128. [CrossRef]

- Ip C. (1986). The chemopreventive role of selenium in carcinogenesis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 206, 431–447.

- Jadhav, S. B., Sandoval-Acuña, C., Pacior, Y., Klanicova, K., Blazkova, K., Sedlacek, R., Stursa, J., Werner, L., & Truksa, J. (2024). Mitochondrially targeted deferasirox kills cancer cells via simultaneous iron deprivation and ferroptosis induction. bioRxiv.

- Jain, M., Nilsson, R., Sharma, S., Madhusudhan, N., Kitami, T., Souza, A. L.,... & Mootha, V. K. (2012). Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science, 336(6084), 1040-1044. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S., Cohen, J., Ward, M. M., Kornhauser, N., Chuang, E., Cigler, T., Moore, A., Donovan, D., Lam, C., Cobham, M. V., Schneider, S., Hurtado Rúa, S. M., Benkert, S., Mathijsen Greenwood, C., Zelkowitz, R., Warren, J. D., Lane, M. E., Mittal, V., Rafii, S., & Vahdat, L. T. (2013). Tetrathiomolybdate-associated copper depletion decreases circulating endothelial progenitor cells in women with breast cancer at high risk of relapse. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 24(6), 1491–1498. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M. J., Kim, W. G., Lim, S., Choi, H. J., Sim, S., Kim, T. Y., Shong, Y. K., & Kim, W. B. (2016). Alpha lipoic acid inhibits proliferation and epithelial mesenchymal transition of thyroid cancer cells. Molecular and cellular endocrinology, 419, 113–123. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Kon, N., Li, T., Wang, S. J., Su, T., Hibshoosh, H., Baer, R., & Gu, W. (2015). Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature, 520(7545), 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q., Christen, S., Shigenaga, M. K., & Ames, B. N. (2001). Gamma-tocopherol, the major form of vitamin E in the US diet, deserves more attention. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 74(6), 714–722. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q., Wong, J., & Ames, B. N. (2004). Gamma-tocopherol induces apoptosis in androgen-responsive LNCaP prostate cancer cells via caspase-dependent and independent mechanisms. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1031, 399–400.

- Jonus, H. C., Byrnes, C. C., Kim, J., Valle, M. L., Bartlett, M. G., Said, H. M., & Zastre, J. A. (2020). Thiamine mimetics sulbutiamine and benfotiamine as a nutraceutical approach to anticancer therapy. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 121, 109648. [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J. E., Kamendulis, L. M., & Hocevar, B. A. (2010). Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in carcinogenesis. Toxicologic pathology, 38(1), 96–109.

- Labuschagne, C. F., van den Broek, N. J., Mackay, G. M., Vousden, K. H., & Maddocks, O. D. (2014). Serine, but not glycine, supports one-carbon metabolism and proliferation of cancer cells. Cell Reports, 7(4), 1248-1258. [CrossRef]

- Levental, K. R., Yu, H., Kass, L., Lakins, J. N., Egeblad, M., Erler, J. T., Fong, S. F., Csiszar, K., Giaccia, A., Weninger, W., Yamauchi, M., Gasser, D. L., & Weaver, V. M. (2009). Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell, 139(5), 891–906. [CrossRef]

- Lippman, S. M., Klein, E. A., Goodman, P. J., Lucia, M. S., Thompson, I. M., Ford, L. G.,... & Crowley, J. J. (2009). Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA, 301(1), 39-51.

- Maller, O., Drain, A. P., Barrett, A. S., Borgquist, S., Ruffell, B., Zakharevich, I., Pham, T. T., Gruosso, T., Kuasne, H., Lakins, J. N., Acerbi, I., Barnes, J. M., Nemkov, T., Chauhan, A., Gruenberg, J., Nasir, A., Bjarnadottir, O., Werb, Z., Kabos, P., Chen, Y. Y., … Weaver, V. M. (2021). Tumour-associated macrophages drive stromal cell-dependent collagen crosslinking and stiffening to promote breast cancer aggression. Nature materials, 20(4), 548–559. [CrossRef]

- Marnett, L. J. (1999). Lipid peroxidation-DNA damage by malondialdehyde. Mutation Research, 424(1-2), 83-95. [CrossRef]

- Martelli, A., & Puccio, H. (2014). Dysregulation of cellular iron metabolism in Friedreich ataxia: from primary iron-sulfur cluster deficit to mitochondrial iron accumulation. Frontiers in pharmacology, 5, 130. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Sanchez, D., Gallegos-Villalobos, A., Fontecha-Barriuso, M., Carrasco, S., Sanchez-Niño, M. D., Lopez-Hernandez, F. J., Ruiz-Ortega, M., Egido, J., Ortiz, A., & Sanz, A. B. (2017). Deferasirox-induced iron depletion promotes BclxL downregulation and death of proximal tubular cells. Scientific reports, 7, 41510. [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, S., Sibbitts, J., Privitera, A., Cardaci, V., Di Pietro, L., Leggio, L., Iraci, N., Lunte, S. M., & Caruso, G. (2023). The Anti-Cancer Activity of the Naturally Occurring Dipeptide Carnosine: Potential for Breast Cancer. Cells, 12(22), 2592. [CrossRef]

- Mikalauskas, S., Glei, M., & Pool-Zobel, B. (2019). Dietary glycine decreases both tumor volume and vascularization in a rat model of colorectal liver metastasis. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 15(7), 1582-1591. [CrossRef]

- Mol, M., Degani, G., Coppa, C., Baron, G., Popolo, L., Carini, M., Aldini, G., Vistoli, G., & Altomare, A. (2019). Advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs) as RAGE binders: Mass spectrometric and computational studies to explain the reasons why. Redox biology, 23, 101083. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M. J., & Liu, Z. G. (2011). Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell research, 21(1), 103–115. [CrossRef]

- Nair, J., Strand, S., Frank, N., Knauft, J., Wesch, H., Galle, P. R., & Bartsch, H. (2005). Apoptosis and age-dependant induction of nuclear and mitochondrial etheno-DNA adducts in Long-Evans Cinnamon (LEC) rats: enhanced DNA damage by dietary curcumin upon copper accumulation. Carcinogenesis, 26(7), 1307–1315. [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M. W., Wani, N. A., Ahirwar, D. K., Powell, C. A., Ravi, J., Elbaz, M., Zhao, H., Padilla, L., Zhang, X., Shilo, K., Ostrowski, M., Shapiro, C., Carson, W. E., 3rd, & Ganju, R. K. (2015). RAGE mediates S100A7-induced breast cancer growth and metastasis by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Cancer research, 75(6), 974–985.

- Nelson-Goedert, N. (2025). The Conglomerate Theory of Aging: A Unified Model of Metal, AGE, and ALE Accumulation. Preprints.org.

- Olm, E., Jönsson-Videsäter, K., Ribera-Cortada, I., Fernandes, A. P., Eriksson, L. C., Lehmann, S., Rundlöf, A. K., Paul, C., & Björnstedt, M. (2009). Selenite is a potent cytotoxic agent for human primary AML cells. Cancer letters, 282(1), 116–123. [CrossRef]

- Omofuma, O. O., Turner, D. P., Peterson, L. L., Merchant, A. T., Zhang, J., & Steck, S. E. (2020). Dietary Advanced Glycation End-products (AGE) and Risk of Breast Cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO). Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa.), 13(7), 601–610. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q., Kleer, C. G., van Golen, K. L., Irani, J., Bottema, K. M., Bias, C., De Carvalho, M., Mesri, E. A., Robins, D. M., Dick, R. D., Brewer, G. J., & Merajver, S. D. (2002). Copper deficiency induced by tetrathiomolybdate suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer research, 62(17), 4854–4859.

- Penta, J. S., Johnson, F. M., Wachsman, J. T., & Copeland, W. C. (2001). Mitochondrial DNA in human malignancy. Mutation research, 488(2), 119–133.. [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N., & Thornalley, P. J. (2015). Dicarbonyl stress in cell and tissue dysfunction contributing to ageing and disease. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 458(2), 221-226. [CrossRef]

- Rašić, I., Rašić, A., Akšamija, G., & Radović, S. (2018). THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SERUM LEVEL OF MALONDIALDEHYDE AND PROGRESSION OF COLORECTAL CANCER. Acta clinica Croatica, 57(3), 411–416. [CrossRef]

- Recalcati, S., Locati, M., Marini, A., Santambrogio, P., Zaninotto, F., De Pizzol, M., Zammataro, L., Girelli, D., & Cairo, G. (2010). Differential regulation of iron homeostasis during human macrophage polarized activation. European journal of immunology, 40(3), 824–835. [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S., Gupta, S. C., Chaturvedi, M. M., & Aggarwal, B. B. (2010). Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked?. Free radical biology & medicine, 49(11), 1603–1616. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D. R., Tran, E. H., & Ponka, P. (1995). The potential of iron chelators of the pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone class as effective antiproliferative agents. Blood, 86(11), 4295–4306. [CrossRef]

- Rose, M. L., Madren, J., & Bunzendahl, H. (1999). Dietary glycine inhibits the growth of B16 melanoma tumors in mice. Carcinogenesis, 20(5), 793-798. [CrossRef]

- Rubashkin, M. G., Cassereau, L., Bainer, R., DuFort, C. C., Yui, Y., Ou, G., Paszek, M. J., Davidson, M. W., Chen, Y. Y., & Weaver, V. M. (2014). Force engages vinculin and promotes tumor progression by enhancing PI3K activation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate. Cancer research, 74(17), 4597–4611. [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, E., Rudolf, K., & Cervinka, M. (2008). Selenium activates p53 and p38 pathways and induces caspase-independent cell death in cervical cancer cells. Cell biology and toxicology, 24(2), 123–141. [CrossRef]

- Sayin, V. I., Ibrahim, M. X., Larsson, E., Nilsson, J. A., Lindahl, P., & Bergo, M. O. (2014). Antioxidants accelerate lung cancer progression in mice. Science translational medicine, 6(221), 221ra15. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, U., Stopper, H., Heidland, A., & Schupp, N. (2008). Benfotiamine exhibits direct antioxidative capacity and prevents induction of DNA damage in vitro. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews, 24(5), 371–377. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G. L. (2010). Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene, 29(5), 625-634. [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, V. C., Gudekar, N., Jasmer, K., Papageorgiou, C., Singh, K., & Petris, M. J. (2021). Copper metabolism as a unique vulnerability in cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular cell research, 1868(2), 118893. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Yang, J., Li, J., Shi, X., Ouyang, L., Tian, Y., & Lu, J. (2014). Carnosine inhibits the proliferation of human gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells through both of the mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis pathways. PloS one, 9(8), e104632. [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, S., Kaino, S., Amano, S., Harima, H., Matsumoto, T., Fujisawa, K., Takami, T., Yamamoto, N., Yamasaki, T., & Sakaida, I. (2018). Deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, with gemcitabine synergistically inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget, 9(47), 28434–28444. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Barden, A., Mori, T., & Beilin, L. (2001). Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia, 44(2), 129–146.

- Stuerenburg, H. J., & Kunze, K. (1999). Concentrations of free carnosine (a putative membrane-protective antioxidant) in human muscle biopsies and rat muscles. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 29(2), 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Torti, S. V., & Torti, F. M. (2013). Iron and cancer: more ore to be mined. Nature Reviews Cancer, 13(5), 342-355.

- Tripathy, J., Tripathy, A., Thangaraju, M., Suar, M., & Elangovan, S. (2018). α-Lipoic acid inhibits the migration and invasion of breast cancer cells through inhibition of TGFβ signaling. Life sciences, 207, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Turner, M. D., Sale, C., Garner, A. C., & Hipkiss, A. R. (2021). Anti-cancer actions of carnosine and the restoration of normal cellular homeostasis. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular cell research, 1868(11), 119117. [CrossRef]

- van Heijst, J. W., Niessen, H. W., Hoekman, K., & Schalkwijk, C. G. (2005). Advanced glycation end products in human cancer tissues: detection of Nepsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine and argpyrimidine. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1043, 725–733. [CrossRef]

- Vinceti, M., Filippini, T., Del Giovane, C., Dennert, G., Zwahlen, M., Brinkman, M.,... & Crespi, C. M. (2018). Selenium for preventing cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD005195.

- Wang, J., Zhao, H., Xu, Z., & Cheng, X. (2020). Zinc dysregulation in cancers and its potential as a therapeutic target. Cancer biology & medicine, 17(3), 612–625. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, F., Hamanaka, R., Wheaton, W. W., Weinberg, S., Joseph, J., Lopez, M., Kalyanaraman, B., Mutlu, G. M., Budinger, G. R., & Chandel, N. S. (2010). Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(19), 8788–8793. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T., Sempos, C. T., Freudenheim, J. L., Muti, P., & Smit, E. (2004). Serum iron, copper and zinc concentrations and risk of cancer mortality in US adults. Annals of epidemiology, 14(3), 195–201.

- Xiao, Q., & Ge, G. (2012). Lysyl oxidase, extracellular matrix remodeling and cancer metastasis. Cancer microenvironment : official journal of the International Cancer Microenvironment Society, 5(3), 261–273. [CrossRef]

- Yamashina, S., Ikejima, K., Rusyn, I., & Sato, N. (2007). Glycine as a potent anti-angiogenic nutrient for tumor growth. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology, 22 Suppl 1, S62–S64. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. C., Chen, W. M., Shia, B. C., & Wu, S. Y. (2025). Impact of long-term N-acetylcysteine use on cancer risk. American journal of cancer research, 15(2), 618–630.

- Yu, H., Pardoll, D., & Jove, R. (2009). STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nature reviews. Cancer, 9(11), 798–809. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., Shen, W., Shi, X., Wang, Q., Zhu, L., Xu, X., Yu, J., & Liu, L. (2019). Upregulated LOX and increased collagen content associated with aggressive clinicopathological features and unfavorable outcome in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of cellular biochemistry, 120(9), 14348–14359. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A., Khatoon, S., Khan, M. J., Abu, J., & Naeem, A. (2025). Advancements and limitations in traditional anti-cancer therapies: a comprehensive review of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy. Discover oncology, 16(1), 607. [CrossRef]

- Zastre, J. A., Sweet, R. L., Hanberry, B. S., & Ye, S. (2013). Linking vitamin B1 with cancer cell metabolism. Cancer & metabolism, 1(1), 16.

- Zhong, W., & Oberley, T. D. (2001). Redox-mediated effects of selenium on apoptosis and cell cycle in the LNCaP human prostate cancer cell line. Cancer research, 61(19), 7071–7078.

- Zhou, J. N., Zhang, B., Wang, H. Y., Wang, D. X., Zhang, M. M., Zhang, M., Wang, X. K., Fan, S. Y., Xu, Y. C., Zeng, Q., Jia, Y. L., Xi, J. F., Nan, X., He, L. J., Zhou, X. B., Li, S., Zhong, W., Yue, W., & Pei, X. T. (2022). A Functional Screening Identifies a New Organic Selenium Compound Targeting Cancer Stem Cells: Role of c-Myc Transcription Activity Inhibition in Liver Cancer. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany), 9(22), e2201166.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).