Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Urogenital schistosomiasis (UGS) remains a major public health concern in Nigeria, particularly in peri-urban and rural communities with poor sanitation and frequent contact with natural water bodies. This study assessed the prevalence, intensity, and age-gender distribution of Schistosoma haematobium infection and associated urinary abnormalities across five under-represented communities in Atiba LGA, Oyo State, Nigeria. Methods: A cross-sectional community-based survey involved 239 residents of Alagbede, Alagbon, Asamu, Ojala, and Ile Titun. Urine samples were microscopically examined for S. haematobium eggs, tested for haematuria, proteinuria, and leukocyturia, and infection intensity classified as light (<50 eggs/10 mL) or heavy (≥50 eggs/10 mL) based on WHO egg count thresholds. Results: An overall UGS prevalence of 56.9% was recorded, with the highest proportions observed in the Alagbede community (69.6%). The overall mean intensity of infection was 64.04 ± 118.81 eggs/10 mL of urine. Females had a slightly higher overall prevalence (58.9%) compared to males (55.7%) (p > 0.05). Across all communities, the 10–17-year age group had the highest prevalence (78.7%) of infection and mean intensity of infection (87.62 ± 163.29 eggs/10 mL), indicating infection to be age-specific. Urinary abnormalities, including haematuria (42.3%), proteinuria (41.8%), and leukocyturia (22.6%), were commonly detected among infected individuals, particularly those with heavy infection intensities. Bulinus truncatus was found only in Asamu, where all the collected snails (100%) shed furcocercous cercariae. Conclusion: This study revealed that UGS remains a serious public health concern in the study area, with school-aged children bearing the greatest burden. The associated urinary abnormalities observed underline the potential long-term health consequences of untreated infections. These findings reinforce the urgent need for sustained and integrated control measures, including improved access to clean water and sanitation, community-based health education, and regular preventive chemotherapy. Strengthening these interventions in endemic communities is key to reducing transmission, safeguarding child health, and moving closer to the elimination of schistosomiasis. This study provides novel epidemiological data on UGS in Atiba LGA, Oyo State, filling a knowledge gap by documenting prevalence, infection intensity, and associated urinary abnormalities in the communities.

Keywords:

1. Summary

2. Introduction

3. Methods

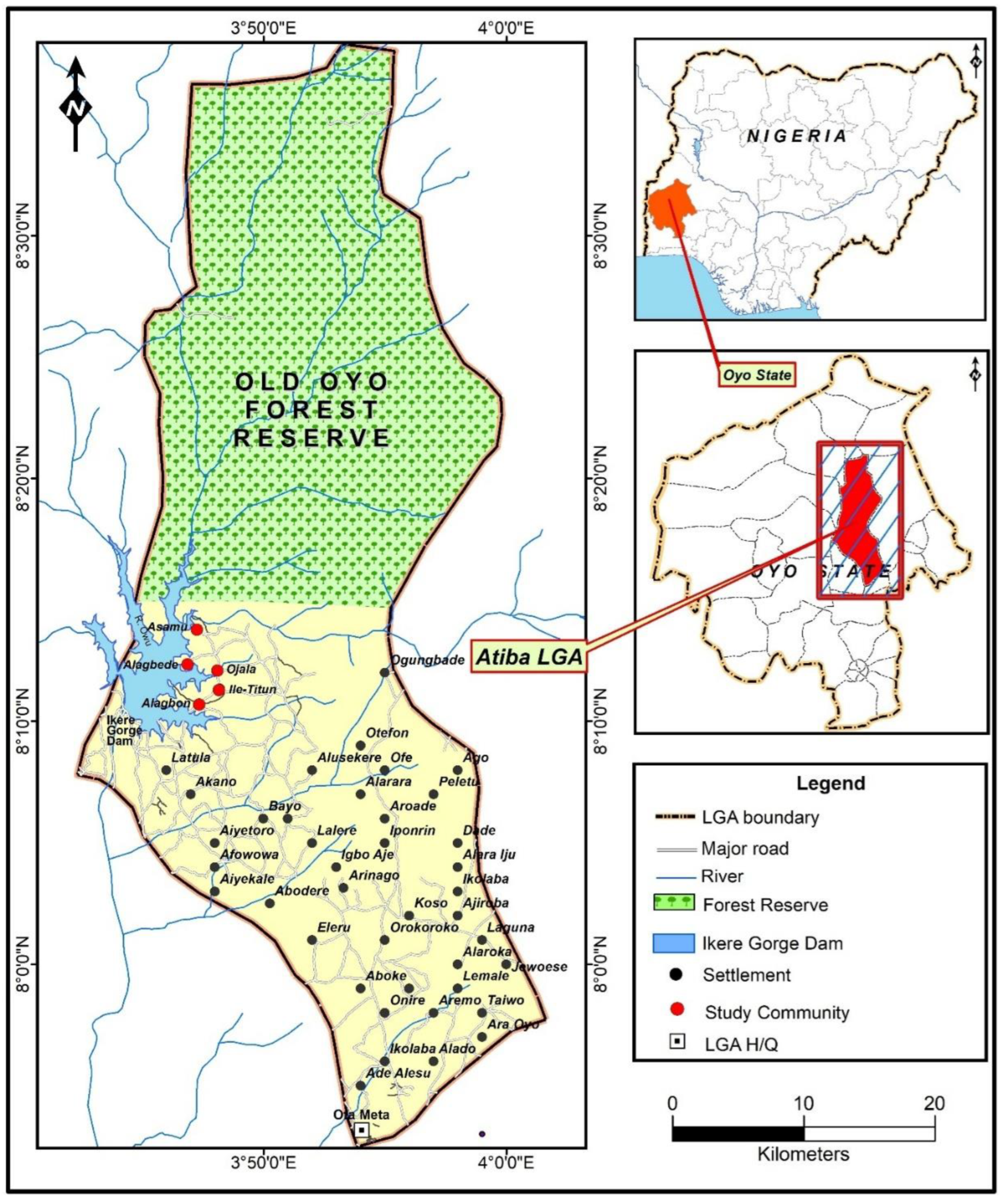

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Study Population, Design and Sample Size

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Urine Collection and Examination for S. haematobium Eggs

3.5. Examination of Urine for Haematuria, Proteinuria and Leukocyturia

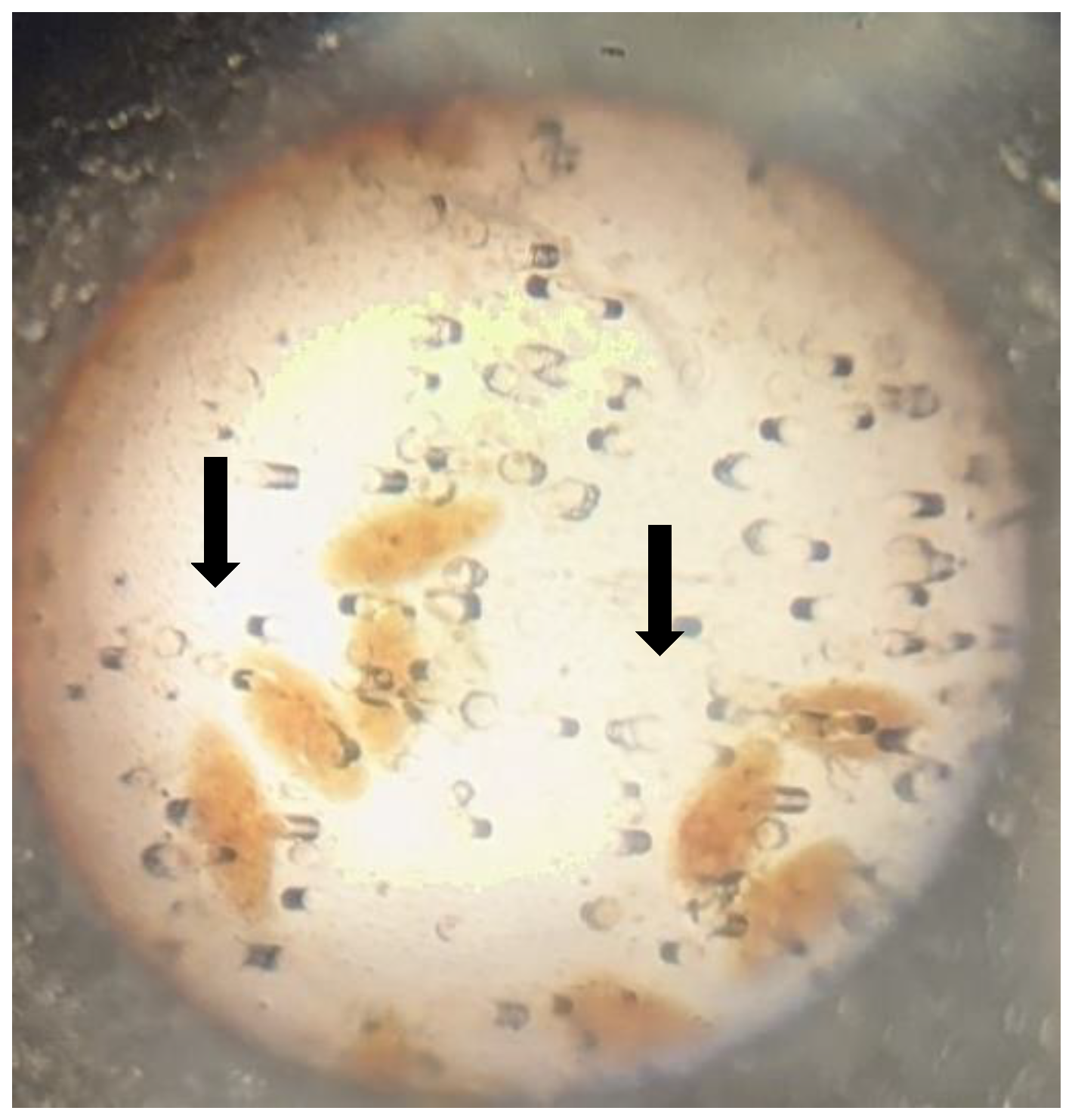

3.6. Snail Survey

3.7. Examination of Snails for Patent Infection

3.8. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

4.2. Overall Prevalence of UGS

4.3. Association Between Urine Characteristics and Infection Status

4.4. Intensity of Infection (Egg Count per 10 mL of Urine) and Prevalence of Schistosomiasis by Age

4.5. Prevalence of Urinary Abnormalities of Infected Individuals

4.6. Prevalence of Schistosomiasis by Gender and Community

4.7. Overall Snail Diversity and Abundance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Future Research Directions

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Availability of Data and Materials

Consent for Publication

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

Abbreviations

| UGS | Urogenital Schistosomiasis |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| MDA | Mass Drug Administration |

| NTDs | Neglected Tropical Diseases |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| LGA | Local Government Area |

| PMF | Polycarbonate Membrane Filter |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| No | Number |

| Assoc | Association |

References

- World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis [Internet]. 2021. https://www.who.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. New road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021– 2030. 2023. https://www.who.int/teams/control-ofneglected-tropical-diseases/ending-ntds-together-towards-2030.

- Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Tropica. 2000;77:41–51. [CrossRef]

- Ekpo UF, Hürlimann E, Schur N, Oluwole AkinolaS, Abe EM, Mafe MA, et al. Mapping and prediction of schistosomiasis in Nigeria using compiled survey data and Bayesian geospatial modelling. Geospat Health. 2013;7:355. [CrossRef]

- Balogun JB, Adewale B, Balogun SU, Lawan A, Haladu IS, Dogara MM, et al. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Urinary Schistosomiasis among Primary School Pupils in the Jidawa and Zobiya Communities of Jigawa State, Nigeria. Annals of Global Health. 2022;88:71. [CrossRef]

- Odaibo AB, Adewunmi CO, Olorunmola FO, Adewoyin FB, Olofintoye LK, Adewunmi TA, et al. Preliminary studies on the prevalence and distribution of urinary schistosomiasis in Ondo State, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2004;33:219–24.

- Christinet V, Lazdins-Helds JK, Stothard JR, Reinhard-Rupp J. Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS): from case reports to a call for concerted action against this neglected gynaecological disease. International Journal for Parasitology. 2016;46:395–404. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf AS, Moi IM, Hassan MA, Abubakar BM. Prevalence, associated risk factors and molecular identification of urinary schistosomiasis among primary school pupils in Jama’are Local Government Area, Bauchi State, Nigeria. J Parasit Dis [Internet]. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Salawu O, Odaibo A. The bionomics and diversity of freshwater snails species in Yewa North, Ogun State, Southwestern Nigeria. Helminthologia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH; 2014;51:337–44. [CrossRef]

- Wang X-Y, Li Q, Li Y-L, Guo S-Y, Li S-Z, Zhou X-N, et al. Prevalence and correlations of schistosomiasis mansoni and schistosomiasis haematobium among humans and intermediate snail hosts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty [Internet]. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2024 [cited 2025 ];13. 24 July. [CrossRef]

- Calasans TAS, Souza GTR, Melo CM, Madi RR, Jeraldo VDLS. Socioenvironmental factors associated with Schistosoma mansoni infection and intermediate hosts in an urban area of northeastern Brazil. Wiegand RE, editor. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0195519. [CrossRef]

- Mbagwu NE, Ajaegbu OC, Ezeonwu BU, Agabi JO, Okwudinka IO, Okolo SN. Prevalence of Urinary Tract Pathology among Pupils Infected with Urinary Schistosomiasis and Those Not Infected with the Infection in Ndokwa-East Lga of Delta State, Nigeria. OALib. 2025;12:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ajakaye OG, Olusi TA, Oniya MO. Environmental factors and the risk of urinary schistosomiasis in Ile Oluji/Oke Igbo local government area of Ondo State. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. 2016;1:98–104. [CrossRef]

- Opeyemi OA, Simon-Oke IA, Olusi TA. Distribution of urinary schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among school-age children in Kwara State, Nigeria. J Parasit Dis. 2025;49:215–23. [CrossRef]

- Bekana T, Abebe E, Mekonnen Z, Tulu B, Ponpetch K, Liang S, et al. Parasitological and malacological surveys to identify transmission sites for Schistosoma mansoni in Gomma District, south-western Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2022;12:17063. [CrossRef]

- Zongo D, Tiendrebeogo JMA, Ouedraogo WM, Bagayan M, Ouedraogo SH, Bougouma C, et al. Epidemiological situation of schistosomiasis in 16 districts of Burkina Faso after two decades of mass treatment. Tuanyok A, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2025;19:e0012858. [CrossRef]

- Nalado Yusuf Ahmed, Abdulkadir Bashir, Yusuf Buhari. Prevalence and Risk factors of Urinary Schistosomiasis among Secondary School Students in Dutsinma Local Government Area of Katsina State. UJMR. 2021;6:108–14. [CrossRef]

- Ponzo E, Midiri A, Manno A, Pastorello M, Biondo C, Mancuso G. Insights into the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and differential diagnosis of schistosomiasis. EuJMI. 2024;14:86–96. [CrossRef]

- Olerimi SE, Ekhoye EI, Enaiho OS, Olerimi A. Selected micronutrient status of school-aged children at risk of Schistosoma haematobium infection in suburban communities of Nigeria. African Journal of Laboratory Medicine [Internet]. AOSIS; 2023 [cited 2025 ];12. 24 July. [CrossRef]

- Hassan J, Mohammed K, Opaluwa S, Adamu T, Nataala S, Garba M, et al. Diagnostic potentials of haematuria and proteinuria in urinary schistosomiasis among school-age children in Aliero Local Government Area, Kebbi State, North-Western Nigeria. AJRIMPS. 2018;2:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Roure S, Vallès X, Pérez-Quílez O, López-Muñoz I, Valerio L, Soldevila L, et al. Therapeutic response to an empirical praziquantel treatment in long-staying sub-Saharan African migrants with positive Schistosoma serology and chronic symptoms: A prospective cohort study in Spain. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2025;154:107873. [CrossRef]

- Morenikeji O, Quazim J, Omoregie C, Hassan A, Nwuba R, Anumudu C, et al. A cross-sectional study on urogenital schistosomiasis in children; haematuria and proteinuria as diagnostic indicators in an endemic rural area of Nigeria. Afr H Sci. 2014;14:390. [CrossRef]

- Smith JH, Christie JD. The pathobiology of schistosoma haematobium infection in humans. Human Pathology. 1986;17:333–45. [CrossRef]

- King CH, Dangerfield-Cha M. The unacknowledged impact of chronic schistosomiasis. Chronic Illness. 2008;4:65–79. [CrossRef]

- Nordin P, Nyale E, Kalambo C, Ahlberg BM, Feldmeier H, Krantz I. Determining the prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis based on the discordance between egg counts and haematuria in populations from northern Tanzania. Front Trop Dis [Internet]. Frontiers Media SA; 2023 [cited 2025 ];4. 24 July. [CrossRef]

- French MD, Rollinson D, Basáñez M-G, Mgeni AF, Khamis IS, Stothard JR. School-based control of urinary schistosomiasis on Zanzibar, Tanzania: monitoring micro-haematuria with reagent strips as a rapid urological assessment. J Pediatr Urol. 2007;3:364–8. [CrossRef]

- Awosolu OB, Akinnifesi OJ, Salawu AS, Omotayo YF, Obimakinde ET, Olise C. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among school age children in Ikota, Southwestern Nigeria. Br J of B Sci. Brazilian Journals; 2019;6:e396. [CrossRef]

- Gundersen SG, Kjetland EF, Poggensee G, Helling-Giese G, Richter J, Chitsulo L, et al. Urine reagent strips for diagnosis of schistosomiasis haematobium in women of fertile age. Acta Tropica. 1996;62:281–7. [CrossRef]

- Vaillant MT, Philippy F, Neven A, Barré J, Bulaev D, Olliaro PL, et al. Diagnostic tests for human Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Microbe. Elsevier BV; 2024;5:e366–78. [CrossRef]

- Ugbomoiko US, Obiezue RNN, Ogunniyi TAB, Ofoezie IE. Diagnostic accuracy of different urine dipsticks to detect urinary schistosomiasis: a comparative study in five endemic communities in Osun and Ogun States, Nigeria. J Helminthol. 2009;83:203–9. [CrossRef]

- Krauth SJ, Greter H, Stete K, Coulibaly JT, Traoré SI, Ngandolo BNR, et al. All that is blood is not schistosomiasis: experiences with reagent strip testing for urogenital schistosomiasis with special consideration to very-low prevalence settings. Parasites Vectors [Internet]. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2015 [cited 2025 ];8. 24 July. [CrossRef]

- Ayabina DV, Clark J, Bayley H, Lamberton PHL, Toor J, Hollingsworth TD. Gender-related differences in prevalence, intensity and associated risk factors of Schistosoma infections in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Santos VS, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009083. [CrossRef]

- Okoli EI, Odaibo AB. Urinary schistosomiasis among schoolchildren in Ibadan, an urban community in south-western Nigeria. Tropical Med Int Health. Wiley; 1999;4:308–15. [CrossRef]

- Bernin H, Lotter H. Sex Bias in the Outcome of Human Tropical Infectious Diseases: Influence of Steroid Hormones. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;209:S107–13. [CrossRef]

- Abaver, DT. A Retrospective Study of Urinary Schistosomiasis in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. TropicalMed. 2024;9:293. [CrossRef]

- Michelson, EH. Adam’s rib awry? Women and schistosomiasis. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;37:493–501. [CrossRef]

- Sellau J, Hansen CS, Gálvez RI, Linnemann L, Honecker B, Lotter H. Immunological clues to sex differences in parasitic diseases. Trends in Parasitology. 2024;40:1029–41. [CrossRef]

- Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021-2030. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- Ezeh CO, Onyekwelu KC, Akinwale OP, Shan L, Wei H. Urinary schistosomiasis in Nigeria: a 50 year review of prevalence, distribution and disease burden. Parasite. 2019;26:19. [CrossRef]

- Odaibo AB, Komolafe AK, Olajumoke TO, Diyan KD, Aluko DA, Alagbe OA, et al. Endemic status of urogenital schistosomiasis and the efficacy of a single-dose praziquantel treatment in unmapped rural farming communities in Oyo East Local Government Area, Oyo State, Nigeria. Webster BL, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18:e0012101. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Manual of basic techniques for a health laboratory. World Health Organization: Geneva. 2003.

- Brown DS, Kristensen TK. '.J" A field guide to African freshwater snails I. West African species.

- Allan F, Ame SM, Tian-Bi Y-NT, Hofkin BV, Webster BL, Diakité NR, et al. Snail-Related contributions from the Schistosomiasis consortium for operational research and evaluation program including Xenomonitoring, focal mollusciciding, biological control, and modelling. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020;103:66–79. [CrossRef]

- Pennance T, Archer J, Lugli EB, Rostron P, Llanwarne F, Ali SM, et al. Development of a molecular snail Xenomonitoring assay to detect Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma bovis Infections in their Bulinus snail hosts. Molecules. 2020;25:4011. [CrossRef]

- Frandsen F, Christensen NO. An introductory guide to the identification of cercariae from African freshwater snails with special reference to cercariae of trematode species of medical and veterinary importance. Acta Trop. 1984;41:181–202.

- Victor A Adebayo, Joshua A Oladimeji. Socioeconomic and prevalence of urinary shistosomiasis infection in riverine areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. IJTDH. 2018;33:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Okpeta EC, Ani OC. Status of urinary schistosomiasis among residents of Ebonyi Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. TZOOL. 2024;24:23–9. [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadir A, Ahmed M, Abubakar BM, Suleiman IE, Yusuf I, Imam IM, et al. Prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis in Nigeria, 1994–2015: Systematic review and meta-analysis. African Journal of Urology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2017;23:228–39. [CrossRef]

- Enabulele EE, Platt RN, Adeyemi E, Agbosua E, Aisien MSO, Ajakaye OG, et al. Urogenital schistosomiasis in Nigeria post receipt of the largest single praziquantel donation in Africa. Acta Tropica. 2021;219:105916. [CrossRef]

- Onyekwere AM, Rey O, Nwanchor MC, Alo M, Angora EK, Allienne JF, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with urogenital schistosomiasis among primary school pupils in Nigeria. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. 2022;18:e00255. [CrossRef]

- Oyelami SO, Oyibo AS, Olabanji AS, Adeleke MA, Odaibo AB. Post-treatment evaluation of urogenital schistosomiasis among elementary school children in Erin Osun, a peri-urban community in Irepodun Local Government Area, Osun State. Nig J Para. 2022;43:127–34. [CrossRef]

- Nkya, TE. Prevalence and risk factors associated with Schistosoma haematobium infection among school pupils in an area receiving annual mass drug administration with praziquantel: a case study of Morogoro municipality, Tanzania. 2023;24.

- Mohammed T, Hu W, Aemero M, Gebrehiwot Y, Erko B. Current Status of Urinary Schistosomiasis among communities in Kurmuk District, Western Ethiopia: prevalence and intensity of Infection. Environ�Health�Insights [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2023 [cited 2025 ];17. 7 July. [CrossRef]

- Atalabi TE, Lawal U, Ipinlaye SJ. Prevalence and intensity of genito-urinary schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among junior high school students in two local government areas around Zobe Dam in Katsina State, Nigeria. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:388. [CrossRef]

- Fusco D, Martínez-Pérez GZ, Remkes A, De Pascali AM, Ortalli M, Varani S, et al. A sex and gender perspective for neglected zoonotic diseases. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1031683. [CrossRef]

- Kazibwe F, Makanga B, Rubaire-Akiiki C, Ouma J, Kariuki C, Kabatereine NB, et al. Transmission studies of intestinal schistosomiasis in Lake Albert, Uganda and experimental compatibility of local Biomphalaria spp. Parasitology International. 2010;59:49–53. [CrossRef]

- Maki AA, Hajissa K, Ali GA. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among selected people in Tulus area, South Darfur State, Sudan. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2021;8:4221. [CrossRef]

- Maseko TSB, Masuku SKS, Dlamini SV, Fan C-K. Prevalence and distribution of urinary schistosomiasis among senior primary school pupils of Siphofaneni area in the low veld of Eswatini: A cross-sectional study. Helminthologia. 2023;60:28–35. [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska, A. Sex—the most underappreciated variable in research: insights from helminth-infected hosts. Vet Res [Internet]. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2022 [cited 2025 ];53. 24 July. [CrossRef]

- Awosolu OB, Shariman YZ, Haziqah M. T. F, Olusi TA. Will Nigerians win the war against urinary schistosomiasis? prevalence, intensity, risk factors and knowledge assessment among some rural communities in Southwestern Nigeria. Pathogens. 2020;9:128. [CrossRef]

- Duwa M, Oyeyi TI, Bassey SE. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among primary school pupils in minjibir local government area of Kano state. Bayero J Pure App Sci. 2010;2:75–8. [CrossRef]

- Bello S, Eberemu EC, Orpin JB, Ya’u S. Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium infection among primary school children in Faskari and funtua Local Government Areas of Katsina State, Nigeria. FJS. 2024;8:311–5. [CrossRef]

- Oso OG, Odaibo AB. Human water contact patterns in active schistosomiasis endemic areas. Journal of Water and Health. 2020;18:946–55. [CrossRef]

- Reitzug F, Ledien J, Chami GF. Associations of water contact frequency, duration, and activities with schistosome infection risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Freeman MC, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17:e0011377. [CrossRef]

- Dejon-Agobé JC, Edoa JR, Honkpehedji YJ, Zinsou JF, Adégbitè BR, Ngwese MM, et al. Schistosoma haematobium infection morbidity, praziquantel effectiveness and reinfection rate among children and young adults in Gabon. Parasites Vectors [Internet]. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2019 [cited 2025 ];12. 1 May. [CrossRef]

- Sumbele IUN, Tabi DB, Teh RN, Njunda AL. Urogenital schistosomiasis burden in school-aged children in Tiko, Cameroon: a cross-sectional study on prevalence, intensity, knowledge and risk factors. Trop Med Health. 2021;49:75. [CrossRef]

- Woldeyohannes D, Sahiledengle B, Tekalegn Y, Hailemariam Z. Prevalence of Schistosomiasis (S. mansoni and S. haematobium) and its association with gender of school age children in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. Elsevier BV; 2021;13:e00210. [CrossRef]

- Hailegebriel T, Nibret E, Munshea A, Ameha Z. Prevalence, intensity and associated risk factors of Schistosoma mansoni infections among schoolchildren around Lake Tana, northwestern Ethiopia. Knight M, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009861. [CrossRef]

- Wilczyńska W, Kasprowicz D, Świetlik D, Korzeniewski K. The Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium and Its Impact on the Hematological Profile of Children Living in Northern Madagascar. Pathogens. MDPI AG; 2025;14:172. [CrossRef]

- Reed AL, O’Ferrall AM, Kayuni SA, Baxter H, Stanton MC, Stothard JR, et al. Modelling the age-prevalence relationship in schistosomiasis: A secondary data analysis of school-aged-children in Mangochi District, Lake Malawi. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. 2023;22:e00303. [CrossRef]

- Elom JE, Odikamnoro OO, Nnachi AU, Ikeh I, Nkwuda JO. The variability of urine parameters in children infected with Schistosoma haematobium in Ukawu Community, Onicha Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. AJID. 2017;11:10–6. [CrossRef]

- Malibiche D, Mushi V, Justine NC, Silvestri V, Mhamilawa LE, Tarimo D. Prevalence and factors associated with ongoing transmission of Schistosoma haematobium after 12 rounds of Praziquantel Mass Drug Administration among school age children in Southern Tanzania. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. Elsevier BV; 2023;23:e00323. [CrossRef]

- Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet. 2006;368:1106–18. [CrossRef]

- Senghor B, Diallo A, Sylla SN, Doucouré S, Ndiath MO, Gaayeb L, et al. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among school children in the district of Niakhar, region of Fatick, Senegal. Parasites Vectors. 2014;7:5. [CrossRef]

- Onile OS, Awobode HO, Oladele VS, Agunloye AM, Anumudu CI. Detection of urinary tract pathology in some Schistosoma haematobium-infected Nigerian adults. Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2016;2016:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Dawaki S, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Ithoi I, Ibrahim J, Abdulsalam AM, Ahmed A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of schistosomiasis among Hausa Communities In Kano State, Nigeria. Rev Inst Med trop S Paulo [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 ];58. 3 May. [CrossRef]

- Ivoke N, Ivoke ON, Nwani CD, Ekeh FN, Asogwa CN, Atama CI, et al. Prevalence and transmission dynamics of Schistosoma haematobium infection in a rural community of southwestern Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Trop Biomed. 2014;31:77–88.

- Houmsou R, Kela S, Suleiman M. Performance of microhaematuria and proteinuria as measured by urine reagent strips in estimating intensity and prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium infection in Nigeria. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011;4:997–1000. [CrossRef]

- Roman D, Jeannette T, Lucia N, Lucie O, Adamou M, Sandra N, et al. Prevalence of Leukocyturia among Schistosoma haematobium Infected School Children in Cameroon. IJTDH. 2016;14:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ngui SM, Mwangangi JM, Richter J, Ngunjiri JW. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths among women of reproductive age in Mwaluphamba, Kwale. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2024;17:71–83. [CrossRef]

- Meurs L, Mbow M, Boon N, Van Den Broeck F, Vereecken K, Dièye TN, et al. Micro-Geographical Heterogeneity in Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium Infection and Morbidity in a Co-Endemic Community in Northern Senegal. Lv S, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2608. [CrossRef]

- Boye A, Agbemator V, Mate-Siakwa P, Essien- Baidoo S. Schistosoma haematobium co-infection with soil-transmitted helminthes: prevalence and risk factors from two communities in the central region of Ghana. Int J Med Biomed Res. 2016;5:86–100. [CrossRef]

- Wiegand RE, Fleming FM, Straily A, Montgomery SP, De Vlas SJ, Utzinger J, et al. Urogenital schistosomiasis infection prevalence targets to determine elimination as a public health problem based on microhematuria prevalence in school-age children. Ramos AN, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009451. [CrossRef]

- Knopp S, Ame SM, Hattendorf J, Ali SM, Khamis IS, Bakar F, et al. Urogenital schistosomiasis elimination in Zanzibar: accuracy of urine filtration and haematuria reagent strips for diagnosing light intensity Schistosoma haematobium infections. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11:552. [CrossRef]

- Kouna LC, Oyegue-Liabagui SL, Atiga CN, Mbani Mpega Ntigui CN, Imboumy-Limoukou RK, Biteghe Bi Essone JC, et al. Molecular Detection of Urogenital Schistosomiasis in Community Level in Semi-Rural Areas in South-East Gabon. Diagnostics. 2025;15:1052. [CrossRef]

- Sunday JO, Oso OG, Babamale AO, Ugbomoiko SU. Urinary Schistosomiasis Prevalence and Diagnostic Performance of Reagent Strip at Point-of-Care. JBM. 2023;11:239–51. [CrossRef]

- Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet. 2014;383:2253–64. [CrossRef]

- Joof E, Sanyang AM, Camara Y, Sey AP, Baldeh I, Jah SL, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of schistosomiasis among primary school children in four selected regions of The Gambia. Zhou X-N, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009380. [CrossRef]

- Deribew K, Erko B, Tiku Mereta S, Yewhalaw D, Mekonnen Z. Assessing Potential Intermediate Host Snails of Urogenital Schistosomiasis, Human Water Contact Behavior and Water Physico-chemical Characteristics in Alwero Dam Reservoir, Ethiopia. Environ�Health�Insights. 2022;16:11786302221123576. [CrossRef]

- Eno-obong Emmanuel Asuquo, Daniel Ohilebo Ugbomoiko, Theophilus Ogie Erameh, Rosemary Edward, Isaac Nyiayem Igbawua. Prevalence and molecular characterization of human urogenital schistosomiasis in selected communities in Keffi local government area, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. GSC Adv Res Rev. 2025;22:025–35. [CrossRef]

- Anosike JC, Nwoke BE, Njoku AJ. The validity of haematuria in the community diagnosis of urinary schistosomiasis infections. J Helminthol. 2001;75:223–5.

- ajol-file-journals_82_articles_59146_submission_proof_59146-973-106623-1-10-20100907 (1).

- Gamde, M. Prevalence, intensity, and risk factors of urinary schistosomiasis among primary school children in Silame, Sokoto Nigeria. Microbes and Infectious Diseases. 2022;0:0–0. [CrossRef]

- Hammad TA, Gabr NS, Talaat MM, Orieby A, Shawky E, Strickland GT. Hematuria and Proteinuria as Predictors of Schistosoma Haematobium Infection. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1997;57:363–7. [CrossRef]

- Mazigo HD, Uisso C, Kazyoba P, Nshala A, Mwingira UJ. Prevalence, infection intensity and geographical distribution of schistosomiasis among pre-school and school aged children in villages surrounding Lake Nyasa, Tanzania. Sci Rep. 2021;11:295. [CrossRef]

- Serra JT, Silva C, Sidat M, Belo S, Ferreira P, Ferracini N, et al. Morbidity associated with schistosomiasis in adult population of Chókwè district, Mozambique. Zakzuk J, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18:e0012738. [CrossRef]

- Hassan J, Mohammed K, Opaluwa S, Adamu T, Nataala S, Garba M, et al. Diagnostic Potentials of Haematuria and Proteinuria in Urinary Schistosomiasis among School-Age Children in Aliero Local Government Area, Kebbi State, North-Western Nigeria. AJRIMPS. 2018;2:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kayange N, Kidenya BR, Muiruri C, Wajanga B, Reis K, Philemon RN, et al. Impact of Praziquantel on Schistosomiasis Infection and the Status of Proteinuria and Hematuria among School Children Living in <i>Schistosoma mansoni</i>-Endemic Communities in Northwestern Tanzania. AID. Scientific Research Publishing, Inc.; 2022;12:448–65. [CrossRef]

- Sow D, Sylla K, Dieng NM, Senghor B, Gaye PM, Fall CB, et al. Molecular diagnosis of urogenital schistosomiasis in pre-school children, school-aged children and women of reproductive age at community level in central Senegal. Parasites Vectors. 2023;16:43. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer KC, Munatsi A, Ndhlovu PD, Wagatsuma Y, Shiff CJ. Urinary schistosomiasis in Zimbabwean school children: predictors of morbidity. Afr Health Sci. 2004;4:115–8.

- Njaanake KH, Omondi J, Mwangi I, Jaoko WG, Anzala O. Urinary interleukins (IL)-6 and IL-10 in schoolchildren from an area with low prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium infections in coastal Kenya. Robinson J, editor. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3:e0001726. [CrossRef]

- Shams M, Khazaei S, Ghasemi E, Nazari N, Javanmardi E, Majidiani H, et al. Prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recently published literature (2016–2020). Trop Med Health. 2022;50:12. [CrossRef]

- Justine NC, Leeyio TR, Fuss A, Brehm K, Mazigo HD, Mueller A. Urogenital schistosomiasis among school children in northwestern Tanzania: Prevalence, intensity of infection, associated factors, and pattern of urinary tract morbidities. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. 2024;27:e00380. [CrossRef]

- Akinwale O, Oso O, Salawu O, Odaibo A, Tang P, Chen T, et al. Molecular characterisation of Bulinus snails – intermediate hosts of schistosomes in Ogun State, South-western Nigeria. Folia Malac. 2015;23:137–47. [CrossRef]

- Kariuki HC, Clennon JA, Brady MS, Kitron U, Sturrock RF, Ouma JH, et al. DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS AND CERCARIAL SHEDDING OF BULINUS NASUTUS AND OTHER SNAILS IN THE MSAMBWENI AREA, COAST PROVINCE, KENYA. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:449–56. [CrossRef]

- Meleko A, Caplan N, Brener Turgeman D, Seifu A, Bentwich Z, Bruck M, et al. Seasonal and Spatial Dynamics of Freshwater Snails and Schistosomiasis in Mizan Aman, Southwest Ethiopia. Parasitologia. MDPI AG; 2025;5:13. [CrossRef]

- Lwanga S, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in Health studies: A practical manual. World Health Organization: Geneva. 1991.

- World Health Organization. Controlling and eliminating neglected tropical diseases [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 13]. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/activities/controlling-and-eliminating-neglected-tropical-diseases. 2025.

- Galappaththi-Arachchige HN, Holmen S, Koukounari A, Kleppa E, Pillay P, Sebitloane M, et al. Evaluating diagnostic indicators of urogenital Schistosoma haematobium infection in young women: A cross sectional study in rural South Africa. Knight M, editor. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191459. [CrossRef]

| Study Community | Distance to Ikere Gorge Dam (km) | Distance to Ibadan |

|---|---|---|

| Alagbede | `5.9km | 92.0km |

| Asamu | 8.4km | 94.6km |

| Ojala | 7.5km | 91.4km |

| Ile titun | 7.0km | 89.9km |

| Alagbon | 5.2km | 88.8km |

| Characteristics | Number Examined (Total= 239) |

Percentage (%) 95% CL |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communities | |||

| Alagbede | 69 | 28.9 [26.5 - 43.3] | <0.001 |

| Asamu | 63 | 26.4 [16.2 -29.4] | |

| Ojala | 13 | 5.4 [0.7-5.9] | |

| Ile Titun | 47 | 19.7 [10.3 - 22.8] | |

| Alagbon | 47 | 19.7 [16.2 - 30.1] | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 149 | 62.3 [52.9 -72.1] | <0.001 |

| Female | 90 | 37.7 [27.9 - 47.1] | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| Total | 239 | 100 [100.0 – 100.0] | |

| 5-9 | 69 | 28.9 [27.2 - 44.9] | <0.001 |

| 10-17 | 47 | 19.7 [18.4 - 36.0] | |

| 18-27 | 25 | 10.5 [5.9 - 16.2] | |

| 28-37 | 30 | 12.6 [2.2 - 11.0] | |

| 38-50 | 26 | 10.9 [2.2 - 11.0] | |

| 51-90 | 42 | 17.6 [7.4 - 19.1] | |

| Urine Colour | |||

| Yellow | 133 | 55.6 [36.8 - 55.9] | <0.001 |

| Red | 35 | 14.6 [17.6 - 30.9] | |

| Brown | 37 | 15.5 [12.5 - 24.3] | |

| Clear | 14 | 5.9 [2.9 - 10.3] | |

| Cloudy | 20 | 8.4 [2.2 - 10.3] |

| Variable | Number examined | Number infected | Prevalence (%) | P-value | Mean Intensity ± SD Eggs/10mL of Urine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection Status | Urine samples | 239 | 136 | 56.9 | <0.001 | |

| Communities | Alagbede | 69 | 48 | 69.6 | 0.005 | 42.35±28.42 |

| Asamu | 63 | 30 | 47.6 | 41.03±25.89 | ||

| Ojala | 13 | 4 | 30.8 | 1.25±0.50 | ||

| Ile titun | 47 | 22 | 46.8 | 86.05±210.65 | ||

| Alagbon | 47 | 32 | 68.1 | 110.84±158.76 | ||

| Sex | Male | 149 | 83 | 55.7 | 0.630 | 76.95±148.55 |

| Female | 90 | 53 | 58.9 | 43.81±34.16 | ||

| Age group (years) | 5-9 | 69 | 49 | 71.0 | <0.001 | 86.94±128.41 |

| 10-17 | 47 | 37 | 78.7 | 87.62±163.29 | ||

| 18-27 | 25 | 15 | 60.0 | 22.6±25.27 | ||

| 28-37 | 30 | 9 | 30.0 | 29.89±28.02 | ||

| 38-50 | 26 | 8 | 30.8 | 29.50±24.25 | ||

| 51 and above | 42 | 18 | 42.9 | 29.50±21.98 | ||

| Urine Colour | Yellow | 133 | 64 | 48.1 | <0.001 | 37.94±49.24 |

| Red | 35 | 32 | 91.4 | 127.63±206.47 | ||

| Brown | 37 | 24 | 64.9 | 67.83±100.07 | ||

| Clear | 14 | 8 | 57.1 | 26.75±26.22 | ||

| Cloudy | 20 | 8 | 40.0 | 44.38±35.15 | ||

| Intensity Status | Light | 239 | 67 | 28.0 | <0.001 | |

| Heavy | 69 | 28.9 |

| Community Surveyed | Age group (years) | No. Examined | No. Infected | Prevalence () [95 CL] | X² (P-value) | Arithmetic Mean (X±SD) Eggs/10mL of Urine [95 CL] | Haematuria [95 CL] | Proteinuria [95 CL] | Leukocyturia [95 CL] | Light Intensity (<50 Eggs/10mL of Urine) % [95% CL) | Heavy intensity (≥50 Eggs/10mL of Urine) % [95% CL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alagbede | 5-9 | 16 | 13 | 81.3 [59.0 - 100.0] |

X2=4.641 (p=0.461) | 58.75 ± 2.99 [55.82 - 61.68] |

93.8 [38.5 – 71.5] |

87.5 [45.7 – 79.3] |

37.5 [3.1 - 31.8] |

93.8% [38.5 - 71.5] |

87.5% [45.7 - 79.3] |

| 10-17 | 12 | 10 | 83.3 [61.7 - 100.0] |

66.75 ± 2.75 [64.05 - 69.45] |

75 [36.6 - 73.7] |

58.3 [29.5 - 67.1] |

41.7 [7.0 – 34.4] |

75.0% [36.6 - 73.7] |

58.3% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 18-27 | 13 | 8 | 61.5 [32.0 - 91.0] |

48.75 ± 2.99 [45.82 - 51.68] |

61.5 [36.6 - 73.7] |

53.8 [29.5 - 67.1] |

7.7 [7.0 – 34.4] |

61.5% [36.6 - 73.7] |

53.8% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 28-37 | 8 | 6 | 75.0 [45.0 - 105.0] |

55.25 ± 1.71 [53.58 - 56.92] |

12.5 [36.6 - 73.7] |

37.5 [29.5 - 67.1] |

0 [7.0 - 34.4] |

12.5% [36.6 - 73.7] |

37.5% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 38-50 | 7 | 4 | 57.1 [21.0 - 93.0] |

47.5 ± 2.08 [45.46 - 49.54] |

28.6 [36.6 - 73.7] |

28.6 [29.5 - 67.1] |

0 [7.0 – 34.4] |

28.6% [36.6 - 73.7] |

28.6% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 51 and above | 13 | 7 | 53.8 [23.5 - 84.1] |

48.0 ± 1.83 [46.21 - 49.79] |

23.1 [36.6 - 73.7] |

46.2 [45.7 - 79.3] |

7.7 [7.0 - 34.4] |

23.1% [36.6 - 73.7] |

46.2% [45.7 - 79.3] |

||

| Asamu | 5-9 | 17 | 11 | 64.7 [42.7 - 86.7] |

X2=19.235 (p=0.002) | 42.5 ± 2.08 [40.46 - 44.54] |

88.2 [31.8 - 61-6] |

88.2 [31.8 - 61.6] |

47.1 [10.1 - 38.7] |

88.2% [31.8 - 61.6] |

88.2% [31.8 - 61.6] |

| 10-17 | 12 | 10 | 83.3 [61.7 - 100.0] |

49.25 ± 2.22 [47.08 - 51.42] |

91.7 [36.6 - 73.7] |

91.7 [29.5 - 67.1] |

58.3 [7.0 – 34.4] |

91.7% [36.6 - 73.7] |

91.7% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 18-27 | 3 | 2 | 66.7 [22.0 - 111.4] |

60.25 ± 1.71 [58.58 - 61.92] |

66.7 [36.6 - 73.7] |

33.3 [29.5 - 67.1] |

66.7 [7.0 – 34.4] |

66.7% [36.6 - 73.7] |

33.3% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 28-37 | 13 | 1 | 7.7 [0.0 - 22.6] |

38.5 ± 1.29 [37.23 - 39.77] |

15.4 [36.6 - 73.7] |

7.7 [29.5 - 67.1] |

0 [7.0 – 34.4] |

15.4% [36.6 - 73.7] |

7.7% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 38-50 | 9 | 2 | 22.2 [0.0 - 61.5] |

48.5 ± 1.29 [47.23 - 49.77] |

11.1 [36.6 - 73.7] |

22.2 [29.5 - 67.1] |

11.1 [7.0 – 34.4] |

11.1% [36.6 - 73.7] |

22.2% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| 51 and above | 9 | 4 | 44.4 [14.3 - 74.5] |

45.5 ± 1.29 [44.23 - 46.77] |

22.2 [36.6 - 73.7] |

44.4 [29.5 - 67.1] |

11.1 [7.0 – 34.4] |

22.2% [36.6 - 73.7] |

44.4% [29.5 - 67.1] |

||

| Ojala | 18-27 | 4 | 1 | 25.0 [0.0 - 55.0] |

X2=1.499 (p=0.683) | 70.25 ± 1.71 [68.58 - 71.92] |

25 [3.6 - 36.4] |

50 [14.7 - 65.3] |

25 [0.4 - 9.6] |

100.0% [39.8 - 100.0] |

0.0% [0.0 - 60.2] |

| 28-37 | 2 | 1 | 50.0 [0.0 - 100.0] |

65.0 ± 1.41 [63.12 - 66.88] |

50 [3.6 - 36.4] |

100 [14.7 - 65.3] |

0 [0.4 - 19.6] |

50.0% [3.6 - 36.4] |

100.0% [14.7 - 65.3] |

||

| 38-50 | 2 | 0 | 0.0 [0.0 - 0.0] |

0.0 ± 0.0 [0.0 - 0.0] |

0 [0.0 - 0.0] |

50 [4.2 - 29.2] |

50 [4.2 - 29.2] |

0.0% [0.0 - 0.0] |

50.0% [4.2 - 29.2] |

||

| 51 and above | 5 | 2 | 40.0 [0.0 - 80.0] |

55.0 ± 1.41 [53.12 - 56.88] |

40 [0.0 - 0.0] |

50 [4.2 - 29.2] |

50 [4.2 - 129.2] |

40.0% [0.0 - 0.0] |

50.0% [4.2 - 29.2] |

||

| Ile Titun | 5-9 | 14 | 6 | 42.9 [15.9 - 69.9] |

X2=4.819 (p=0.438) | 48.5 ± 1.29 [47.23 - 49.77] |

57.1 [31.1 - 73.7] |

78.6 [45.7 - 79.3] |

7.1 [3.1 - 31.8] |

57.1% [31.1 - 73.7] |

78.6% [45.7 - 79.3] |

| 10-17 | 14 | 8 | 57.1 [31.9 - 82.3] |

51.5 ± 1.29 [50.23 - 52.77] |

64.3 [22.6 - 62.0] |

85.7 [49.7 - 94.7] |

14.3 [3.8 - 34.6] |

64.3% [22.6 - 62.0] |

85.7% [49.7 - 94.7] |

||

| 18-27 | 5 | 4 | 80.0 [34.0 - 100.0] |

60.25 ± 1.71 [58.58 - 61.92] |

80.0 [22.6 - 62.0] |

20.0 [49.7 - 94.7] |

20.0 [3.8 - 34.6] |

80.0% [22.6 - 62.0] |

20.0% [49.7 - 94.7] |

||

| 28-37 | 4 | 1 | 25.0 [0.0 - 58.0] |

40.5 ± 1.29 [39.23 - 41.77] |

50.0 [22.6 - 62.0] |

25.0 [49.7 - 94.7] |

25.0 [3.8 - 34.6] |

50.0% [22.6 - 62.0] |

25.0% [49.7 - 94.7] |

||

| 38-50 | 3 | 1 | 33.3 [0.0 - 80.0] |

50.5 ± 1.29 [49.23 - 51.77] |

33.3 [22.6 - 62.0] |

66.7 [49.7 - 94.7] |

0 [3.8 - 34.6] |

33.3% [22.6 - 62.0] |

66.7% [49.7 - 94.7] |

||

| 51 and above | 7 | 2 | 28.6 [0.0 - 57.0] |

45.5 ± 1.29 [44.23 - 46.77] |

57.1 [49.7 - 94.7] |

28.6 [22.6 - 62.0] |

57.1 [3.8 - 34.6] |

57.1% [49.7 - 94.7] |

57.1% [22.6 - 62.0] |

||

| Alagbon | 5-9 | 22 | 19 | 86.4 [74.6 - 98.2] |

X2=22.766 (p<0.001) | 60.25 ± 1.71 [58.58 - 61.92] |

95.5 [68.6 - 95.0] |

100 [83.2 - 98.6] |

22.7 [3.2 – 33.2] |

95.5% [68.6 - 95.0] |

100% [83.2 - 98.6] |

| 10-17 | 9 | 9 | 100.0 [100.0 - 100.0] |

70.5 ± 1.29 [69.23 - 71.77] |

100 [72.4 – 99.1] |

100 [59.7 – 97.5] |

33.3 4.3 - 52.9] |

100% [72.4 - 99.1] |

100% [59.7 - 97.5] |

||

| 28-37 | 3 | 0 | 0.0 [0.0 - 0.0] |

0.0 ± 0.0 [0.0 - 0.0] |

33.3 [0.0 - 0.0] |

66.7 [72.4 - 99.1] |

0 [0.0 - 0.0] |

33.3% [0.0 - 0.0] |

66.7% [72.4 - 99.1] |

||

| 38-50 | 5 | 1 | 20.0 [0.0 - 50.0] |

48.5 ± 1.29 [47.23 - 49.77] |

60.0 [68.6 - 95.0] |

80.0 [83.2 - 98.6] |

20.0 [3.2 – 33.2] |

60.0% [68.6 - 95.0] |

80.0% [83.2 - 98.6] |

||

| 51 and above | 8 | 3 | 37.5 [11.8 - 63.2] |

45.5 ± 1.29 [44.23 - 46.77] |

62.5 [72.4 - 99.1] |

50.0 [59.7 - 97.5] |

12.5 [4.3 - 52.9] |

62.5% [72.4 - 99.1] |

50.0% [59.7 - 97.5] |

| Urinary abnormality | Number examined | Number infected | Prevalence (%) | Test of association with infection intensity p-value |

Gender | χ² value | df | Test of association with gender p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence in male (%) | Prevalence in female (%) | ||||||||

| Haematuria | 239 | 101 | 42.26 | <0.001 | 59.06 | 61.67 | 0.0521 | 1 | 0.8195 |

| Proteinuria | 239 | 100 | 41.84 | <0.001 | 20.07 | 58.44 | 0.1469 | 1 | 0.7015 |

| Leukocyturia | 239 | 54 | 22.59 | <0.001 | 30.02 | 64.46 | 1.7680 | 1 | 0.1836 |

| Abnormality | Median eggs/10 mL of urine | Mean eggs/10 mL of urine | n | Wilcoxon W | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haematuria | 53 | 76.2 | 101 | 1105 | 0.001 |

| Proteinuria | 53.5 | 77.7 | 100 | 1044 | 0.0002 |

| Leukocyturia | 58 | 59.8 | 54 | 1533 | 0.029 |

| Community Surveyed | Sex | No. Examined | No. Infected | Prevalence (%) [95% CL] | X² (P-value) | Arithmetic Mean (X±SD) Eggs/10mL of Urine [95% CL] | Haematuria [95% CL] | Proteinuria [95% CL] | Leukocyturia [95% CL] | Light Intensity (<50 Eggs/10 mL) % [95% CL] | Heavy Intensity (≥50 Eggs/10 mL) % [95% CL] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alagbede | Male | 40 | 27 | 67.5 [47.7 - 87.3] |

X2 =0.189 (p=0.191) |

39.59 ± 28.36 [28.89 - 50.29] | 55 [0.385 - 0.715] |

62.5 [0.457 - 0.793] |

17.5 [0.031 - 0.318] |

55.6 [35.3–74.5] |

44.4 [25.5–64.7] |

| Female | 29 | 21 | 72.4 [50.9 - 93.9] |

- | 45.90 ± 28.80 [33.59 - 58.22] | 55 [0.366 - 0.737] |

48.3 [0.295 - 0.671] |

20.7 [0.070 - 0.344] |

33.3 [14.6–57.0] |

66.7 [43.0–85.4] |

|

| Asamu | Male | 45 | 19 | 42.2 [26.7 - 57.7] |

X2=1.810 (p=0.09) |

41.26 ± 25.72 [29.70 - 52.83] | 46.7 [0.318 - 0.616] |

46.7 [0.318 - 0.616] |

24.4 [0.101 - 0.387] |

36.8 [16.3–61.6] |

63.2 [38.4–83.7] |

| Female | 18 | 11 | 61.1 [32.5 - 89.7] |

- | 40.64 ± 27.45 [24.41 - 56.86] | 66.7 [0.406 - 0.928] |

72.2 [0.497 - 0.947] |

44.4 [0.203 - 0.685] |

36.4 [10.9–69.2] |

63.6 [30.8–89.1] |

|

| Ojala | Male | 10 | 4 | 40.0 [7.0 - 73.0] |

X2=1.600 (p=0.294) |

1.25 ± 0.50 [0.76 - 1.74] |

20.0 [0.036 - 0.364] |

40.0 [0.147 - 0.653] |

10.0 [0.004 - 0.196] |

100.0 [39.8–100.0] |

0.0 [0.0–60.2] |

| Female | 3 | 0 | 0.0 [0.0 - 0.0] |

- | - | 0.0 [0.000 - 0.000] |

66.7 [0.042 - 1.292] |

66.7 [0.042 - 1.292] |

0.0 [0.0–0.0] |

0.0 [0.0–0.0] |

|

| Ile Titun | Male | 21 | 10 | 47.6 [21.2 - 74.0] |

X2=0.010 (p=0.23) |

153.00 ± 303.59 [35.17 - 341.17] | 76.2 [0.311 - 0.737] |

52.4 [0.189 - 0.876] |

19.0 [0.043 - 0.529] |

70.0 [34.8–93.3] |

30.0 [6.7–65.2] |

| Female | 26 | 12 | 46.2 [19.3 - 73.1] |

- | 30.25 ± 42.82 [6.02 - 54.48] | 42.3 [0.226 - 0.620] |

69.2 [0.497 - 0.947] |

19.2 [0.038 - 0.346] |

83.3 [51.6–97.9] |

16.7 [2.1–48.4] |

|

| Alagbon | Male | 33 | 23 | 69.7 [54.5 - 84.8] |

X2=0.231 (p=0.096) |

130.39 ± 183.24 [55.50 - 205.28] | 81.8 [0.686 - 0.950] |

90.9 [0.832 - 0.986] |

18.2 [0.032 - 0.332] |

43.5 [23.2–65.5] |

56.5 [34.5–76.8] |

| Female | 14 | 9 | 64.3 [39.5 - 89.0] |

- | 60.89 ± 37.68 [36.27 - 85.51] | 85.7 [0.724 - 0.991] |

78.6 [0.597 - 0.975] |

28.6 [0.043 - 0.529] |

33.3 [7.5–70.1] |

66.7 [29.9–92.5] |

| Snail Species | Type of snail | Asamu community | Alagbede community |

Ojala community |

Alagbon community |

Total (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. collected (%) | No. with patent Furcocercous schistosome–like cercariae (%) |

No. collected (%) | No. with patent Schistosoma infection (%) | No. collected (%) |

No. with patent Schistosoma infection (%) | No. collected ( %) | No. with patent Schistosoma infection (%) | |||

| Aplexa waterloti | Pulmonate | 9 | 0(0.0) | 28 | 0(0.0) | 18 | 0(0.0) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 55(13.5) |

| Bulinus truncatus | Pulmonate | 2 | 2(100) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 2(0.49) |

| Belamyar unicolor | Prosobranch | 1 | 0(0.0) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 1 | 0(0.0) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 2(0.49) |

| Gabiella spirilosa | Prosobranch | 0 | 0(0.0) | 18 | 0(0.0) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 54 | 0(0.0) | 72(17.69) |

| Melanoides tuberculata | Prosobranch | 89 | 0(0.0) | 48 | 0(0.0) | 25 | 0(0.0) | 11 | 0(0.0) | 173(42.51) |

| Hydrobia sp. | Prosobranch | 83 | 0(0.0) | 12 | 0(0.0) | 0 | 0(0.0) | 4 | 0(0.0) | 99(24.32) |

| Pila ovata | Prosobranch | 0 | 0(0.0) | 1 | 0(0.0) | 1 | 0(0.0) | 2 | 0(0.0) | 4(0.98) |

| Total | 184 | 2(1.09) | 107 | 0(0.0) | 45 | 0(0.0) | 71 | 0(0.0) | 407 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).