Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Background

- Scene safety assessment

- Scene size-up

- Send information

- Scene set-up

- START: Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment

Objectives and Rationale

- Identify common educational approaches across different learner groups

- Highlight innovations such as simulation, VR, interprofessional learning, and community-integrated models

- Expose existing gaps in content coverage, target group inclusion, and training adaptability

- Provide a foundation for future research and curriculum development that supports system-wide disaster preparedness beyond MFRs alone

Methods

Protocol Design

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

- Disaster medicine: A medical specialty focused on two key areas: delivering healthcare to individuals affected by disasters and leading medically related efforts in disaster preparedness, planning, response, and recovery across all phases of the disaster lifecycle [15].

- Disaster preparedness: This refers to the proactive measures and strategies implemented to minimize the effects of emergencies such as hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, and other disasters on individuals, communities, and institutions. It encompasses creating emergency response plans, preparing disaster-specific kits, maintaining critical supplies, and conducting routine drills and training sessions [16].

- Mass casualty incident (MCI): An MCI is an event in which the number and severity of victims surpass the available resources of emergency medical services, including personnel, equipment, and facilities. For example, a sudden surge of patients at a small rural clinic following a nearby industrial explosion can qualify as an MCI. More commonly recognized scenarios include large-scale disasters such as plane crashes, earthquakes, major traffic collisions, and structural collapses [1].

- Curriculum design: Curriculum design refers to the intentional and structured planning of instructional content within a course or program. It involves organizing what will be taught, determining who will deliver the instruction, and establishing the timeline for implementation; essentially serving as a roadmap for educators to guide the teaching and learning process [17].

- Simulation training: Simulation provides learners with the opportunity to build experience, confidence, and competence in managing specific, often rare conditions or scenarios that are not commonly encountered in real clinical settings [18].

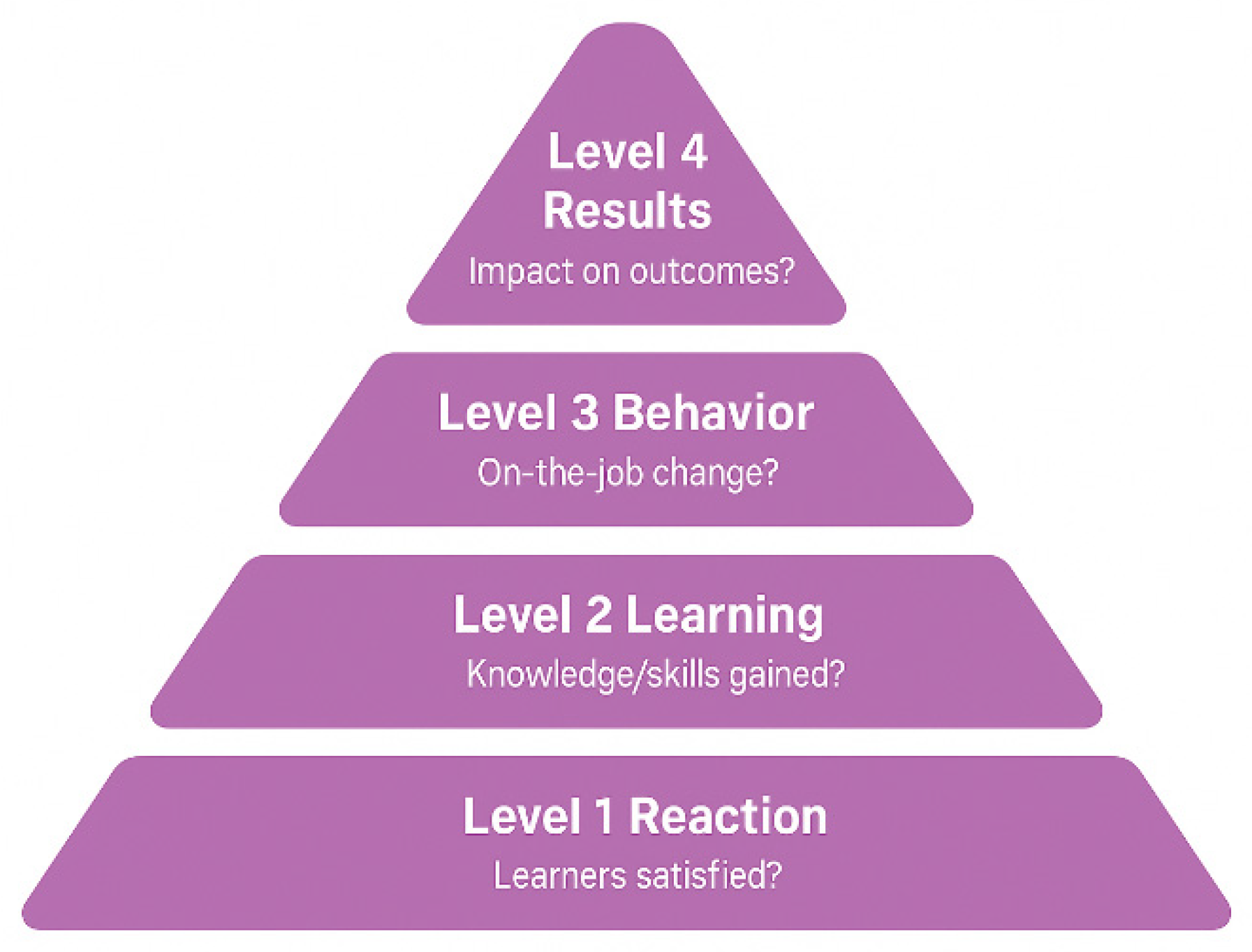

- Kirkpatrick’s model: The Kirkpatrick Model, introduced by Dr. Donald Kirkpatrick in 1959, is one of the most widely used frameworks for evaluating training effectiveness. It breaks down evaluation into four key levels to assess impact and outcomes:

- How are disaster and mass casualty incident (MCI) training curricula designed and implemented across different healthcare professionals globally?

- What types of educational settings (e.g., undergraduate, in-service) are used to deliver MCI training across healthcare professions?

- Which healthcare roles (e.g., paramedics, nurses, residents, physicians) are targeted in disaster training programs?

- What pedagogical strategies and teaching methods (e.g., simulation, PBL, tabletop exercises) are commonly employed in MCI/disaster training curricula?

- Which disaster competency frameworks (e.g., WHO EMT Standards, NDLS, Core Competencies for Disaster Medicine) are referenced in training programs?

- Which domains or themes (e.g., triage, logistics, leadership, communication) and specific competencies (e.g., PPE use, field triage, incident command) are emphasized in the curricula?

- What types of MCI scenarios (e.g., earthquake, flood, chemical spill, pandemic) are used in training simulations?

- How are training modalities (e.g., in-person, online, hybrid) and pacing models (e.g., fixed schedule vs. self-paced) applied across different programs?

- How is pre-simulation preparation structured (e.g., videos, handouts)?

- What assessment and evaluation methods (e.g., OSCE, pre/post-tests, surveys) are used to measure learning outcomes, and what level of the Kirkpatrick framework do they reach?

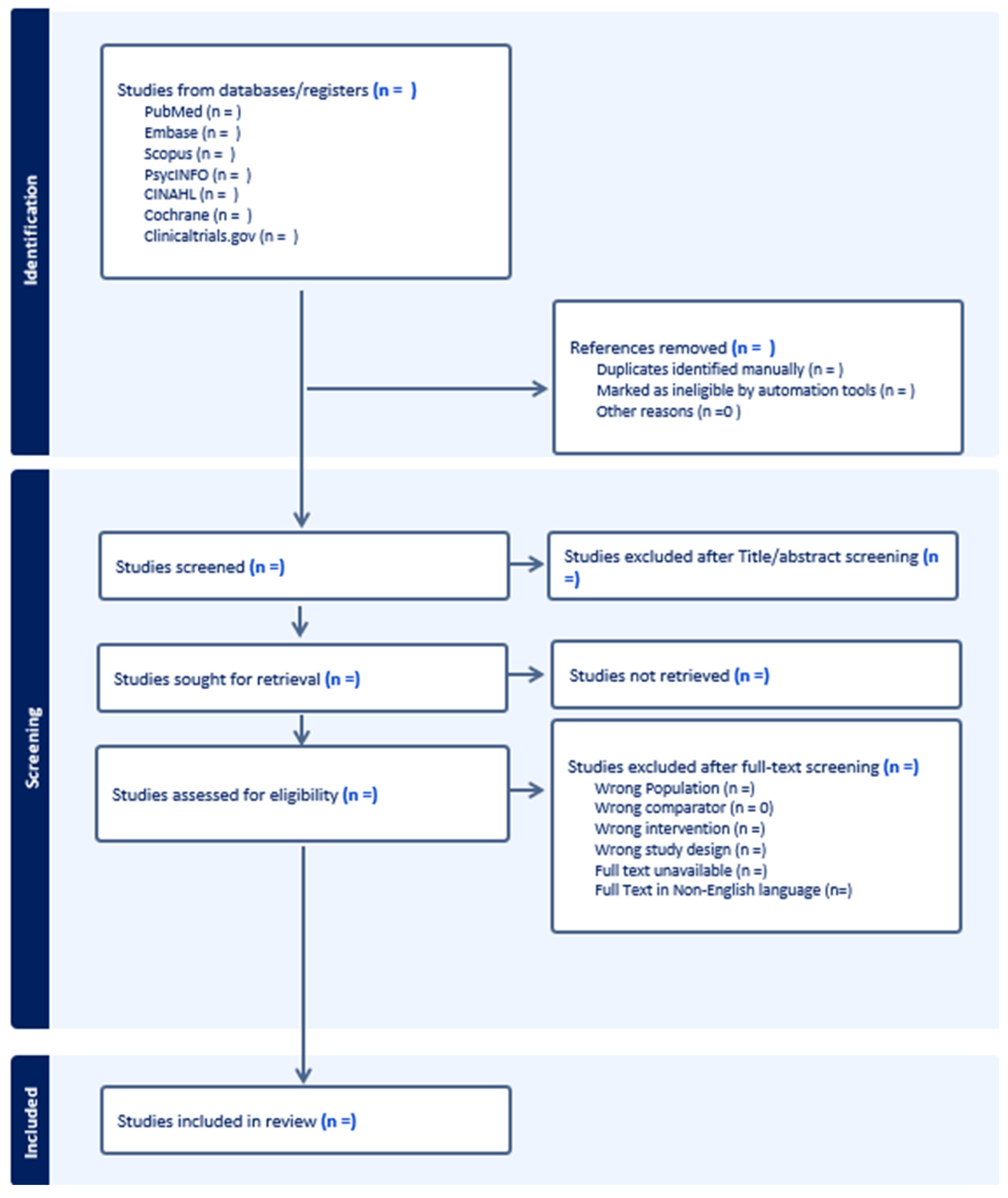

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

- PubMed – for peer-reviewed publications in the biomedical and life sciences

- Embase – offering broad biomedical coverage, including literature from European and Asian sources

- Scopus – encompassing scientific, technical, and medical research from various disciplines

- PsycINFO (via APA PsycNet) – for studies focusing on the psychological dimensions of training and education

- CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) – for research related to nursing and allied health fields

- Cochrane Library – for accessing systematic reviews and evidence from clinical trials

- ClinicalTrials.gov – to identify registered clinical trials relevant to our review

- Google Scholar – to capture additional academic and grey literature

Stage 3: Study Selection

-

Population:

- o

- Involve healthcare providers, including but not limited to physicians, nurses, paramedics, EMTs, residents, and interns.

- o

- Include university or college students enrolled in health-related fields (e.g., medicine, nursing, public health, EMS).

-

Concept:

- o

- Describe or evaluate curricular design strategies in disaster medicine or MCI training.

- o

- Focus on curriculum structure, delivery methods, learning outcomes, or training modalities.

-

Context:

- o

- Focus on disaster medicine or mass casualty incident (MCI) education and training.

- o

- Can include both prehospital and in-hospital training environments.

-

Study Types:

- o

- Include primary studies (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods), and curriculum development reports.

- o

- May include grey literature, such as conference abstracts or government/NGO reports, if they provide relevant curriculum detail.

- o

- Studies published in English, with a restriction on publication year to the last 10 years.

- Do not focus on disaster or MCI training (e.g., general emergency care, trauma surgery without a disaster context).

- Are solely focused on effectiveness evaluations without describing the curriculum structure or instructional design.

- Involve non-healthcare populations (e.g., military, engineers, general public) without a separate analysis for healthcare participants.

- Do not describe any form of curriculum content, strategy, or framework (e.g., focus only on knowledge/attitude assessments or survey perceptions).

- Are editorials, commentaries, or opinion pieces without empirical data or descriptive curriculum details.

- Systematic reviews, literature reviews, and other scoping reviews.

- Are not available in full text.

Stage 4: Data Charting

| Field | Description |

| Study ID | Last name of author and year of publication. |

| Paper DOI | Digital Object Identifier of the paper, if available. |

| Country | The country where the study was conducted. |

| Study Design | Type of study (e.g., RCT, Qualitative, Cross-sectional, Review). |

| Target Population | Description of participants (e.g., EMS personnel, paramedics, medical students). |

| Educational Setting | Undergraduate, Postgraduate, In-service, CME. |

| Study Aim / Objective | Primary objective(s) or research question(s) of the study. |

| Duration of the Course | Time frame or length of the educational/training intervention (e.g., 2 weeks, 3 months, 4 sessions). |

| Curriculum Content | Topics covered in the intervention (e.g., triage, communication, first aid, disaster preparedness). |

| Delivery Modality | Format of instruction (e.g., online, face-to-face, blended, workshop, lecture, simulation-based). |

| Teaching Strategies | All instructional strategies used (e.g., role-play, case studies, debriefing, group discussion). |

| Pacing Model: Fixed vs. Self-Paced | Whether the course was scheduled and synchronous (fixed) or flexible and self-directed (self-paced). |

| Simulation Included? (Y/N) | Yes/No – whether simulation was part of the study. |

| Simulation Type | If simulation is included, specify type (e.g., tabletop, high-fidelity mannequin, virtual reality, drill). |

| MCI Type | Type of mass casualty incident used in scenario (e.g., earthquake, pandemic, explosion, chemical spill). |

| Information on Facilitator (if any) | Background or role of facilitators (e.g., clinical instructor, subject expert, external trainer). |

| Outcomes measured | List all measured outcomes (e.g., knowledge, skills, attitudes, confidence, performance). |

| Describe the findings (results) | Key findings reported by the study (quantitative and/or qualitative). |

| Comparator Present? | Yes/No – whether a comparator group or condition was included. |

| Elaborate on the comparator | If present, describe comparator (e.g., traditional lecture vs. simulation-based training). |

| Which disaster frameworks or systems are referenced or applied in the course? | Any disaster competency frameworks or operational protocols (e.g., START, ICS). |

| General Program Frameworks / Standards Referenced | Educational or professional frameworks guiding the curriculum (e.g., Bloom’s taxonomy, Kirkpatrick’s model, CANMEDS). |

| How was the Data Collected? | Methods of data collection (e.g., survey, exam, observation, interview, performance checklist). |

| Framework/model of training design? | If training design is explicitly based on a framework (e.g., ADDIE, Kern’s six-step approach). |

| Framework/model of assessment, if present | If the assessment uses a framework (e.g., Kirkpatrick, Miller’s pyramid, OSCE model). |

| Mention any cognitive support system or other scaffold | Any support structures provided to aid learning (e.g., decision aids, checklists, feedback, e-learning scaffolds). |

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

- Curriculum structure and design approaches

- Educational setting and learner level (e.g., undergraduate, in-service)

- Target healthcare populations (e.g., paramedics, nurses, physicians, students)

- Instructional methods and pedagogical strategies (e.g., simulation, PBL, lectures)

- Competency frameworks and disaster-specific standards referenced

- Assessment methods and evaluation levels (e.g., Kirkpatrick Model)

- Use and types of simulation, including roles, tasks, and real-world alignment

- Reported outcomes

Stage 6: Stakeholder Consultation (Optional Stage)

Limitations

Ethics and Dissemination

Ethical Considerations

Dissemination Strategy

- Peer-Reviewed Publication

- 2.

- Conference Presentations

- World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine (WADEM)

- International Conference on Emergency Medicine (ICEM)

- National EMS conferences and simulation education events

- 3.

- Stakeholder Engagement

- EMS organizations

- Disaster response agencies

- Simulation centers

- Prehospital training programs

- 4.

- Open Access and Preprints

- 5.

- Professional Networks and Social Media

- 6.

- Policy Briefs

- 7.

- Implementation and Collaboration

- 8.

- Research Gaps and Agenda

- 9.

- Review Updates

Project Timeline

| Stage | Duration | Weeks |

| Planning & Protocol Development | 4 weeks | Weeks 1–4 |

| - Team meetings & protocol drafting | ||

| - Protocol registration (e.g., OSF) | ||

| Literature Search | 3 weeks | Weeks 5–7 |

| - Finalize and conduct search | ||

| - Grey literature and manual search | ||

| Study Selection | 6 weeks | Weeks 8–13 |

| - Title/abstract screening | ||

| - Full-text screening | ||

| Data Charting | 4 weeks | Weeks 14–17 |

| - Pilot and finalize charting form | ||

| - Extract data from included studies | ||

| Analysis & Synthesis | 6 weeks | Weeks 18–23 |

| - Thematic and descriptive analysis | ||

| - Identify trends, gaps, and insights | ||

| Report Writing | 4 weeks | Weeks 24–27 |

| - Draft, review, and finalize manuscript | ||

| Dissemination Activities | 5+ weeks | Weeks 28–32+ |

| - Prepare journal submission | ||

| - Presentations, briefs, stakeholder outreach |

- Weekly team meetings to monitor progress

- Buffer time built into each phase to accommodate unforeseen delays

- Dissemination activities may continue beyond Week 32 due to conference and stakeholder engagement schedules

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Mass casualty management systems: strategies and guidelines for building health sector capacity. 2007;34.

- Mass Casualty Management [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/clinical-services-and-systems/emergency-and-critical-care/mass-casualty-management (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- DeNolf RL, Kahwaji CI. EMS Mass Casualty Management. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482373/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Herstein JJ, Schwedhelm MM, Vasa A, Biddinger PD, Hewlett AL. Emergency preparedness: What is the future? Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2021;1(1):e29.

- Implementing 9/11 Commission Recommendations | Homeland Security [Internet]. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/implementing-911-commission-recommendations (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Bahattab A, Trentin M, Hubloue I, Della Corte F, Ragazzoni L. Humanitarian health education and training state-of-the-art: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2024 Jul 29;12:1343867.

- EMAP-Policies-Procedures-for-the-Development-of-an-American-National-Standards_March-22-2023_Final.pdf [Internet]. Available online: https://emap.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/EMAP-Policies-Procedures-for-the-Development-of-an-American-National-Standards_March-22-2023_Final.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Almukhlifi Y, Crowfoot G, Wilson A, Hutton A. Emergency healthcare workers’ preparedness for disaster management: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021 Jul 12;jocn.15965.

- Glow SD, Colucci VJ, Allington DR, Noonan CW, Hall EC. Managing Multiple-Casualty Incidents: A Rural Medical Preparedness Training Assessment. Prehosp Disaster med. 2013 Aug;28(4):334–41.

- Baetzner AS, Hill Y, Roszipal B, Gerwann S, Beutel M, Birrenbach T, et al. Mass Casualty Incident Training in Immersive Virtual Reality: Quasi-Experimental Evaluation of Multimethod Performance Indicators. J Med Internet Res. 2025 Jan 27;27:e63241.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005 Feb;8(1):19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci. 2010 Dec;5(1):69.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 2;169(7):467–73.

- Yussef HH, Abdelhamied NM, Elmisbah SA, Omayer A, Ali MA, Hubloue I, et al. Curricular Design Strategies in Disaster Medicine Education- A Scoping Review Protocol. 2025 Jul 3. Available online: https://www.protocols.io/view/curricular-design-strategies-in-disaster-medicine-g4fcbytix (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- School of Medicine and Health Sciences [Internet]. Disaster Medicine. Available online: https://ospe.smhs.gwu.edu/disaster-medicine (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- SafetyCulture [Internet]. 2023. Disaster Preparedness: A Guide. Available online: https://safetyculture.com/topics/disaster-preparedness/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- ThoughtCo [Internet]. How to Develop Effective Curriculum Design. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/curriculum-design-definition-4154176 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Davis D, Warrington SJ. Simulation Training and Skill Assessment in Emergency Medicine. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557695/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Falletta, S. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels Donald L. Kirkpatrick, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA, 1996, 229 pp. The American Journal of Evaluation. 1998;19(2):259–61.

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2016 Jul;75:40–6.

- Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org.

| Population | Concept | Context |

| paramedic* | “Curriculum design” | “Disaster medicine” |

| “First responders” | “Instructional design” | “Disaster preparedness” |

| “Medical student” | “Educational strategies” | “Mass casualty incident” |

| physician* | “Curriculum”[Mesh] | “Emergency preparedness” |

| intern* | “Mass Casualty Incidents”[Mesh] | |

| nurse* | “Disaster Medicine”[Mesh] | |

| “Healthcare provider” | “Disaster Planning”[Mesh] | |

| “Paramedics”[Mesh] | ||

| “Health Personnel”[Mesh] | ||

| “Nurses”[Mesh] | ||

| “Physicians”[Mesh] |

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“disaster medicine” OR “disaster preparedness” OR “mass casualty incident” OR “emergency preparedness” OR “Mass Casualty Incidents”[MeSH] OR “Disaster Medicine”[MeSH] OR “Disaster Planning”[MeSH]) AND (“curriculum design” OR “instructional design” OR “educational strategies” OR “Curriculum”[MeSH] OR “Education”[MeSH] OR “Simulation Training”[MeSH] OR “Teaching”[MeSH]) AND (“first responders” OR intern* OR “healthcare provider” OR “Paramedics”[MeSH] OR “Health Personnel”[MeSH] OR “Nurses”[MeSH] OR “Physicians”[MeSH]) AND (y_10[Filter]) |

| Scopus | ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “disaster medicine” OR “disaster preparedness” OR “mass casualty incident” OR “emergency preparedness” ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “curriculum design” OR “instructional design” OR “educational strategies” OR “simulation training” OR education* OR teaching OR training ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( paramedic* OR “first responders” OR “medical student” OR physician* OR intern* OR nurse* OR “healthcare provider” ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND ( EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE, “re” ) ) AND ( EXCLUDE ( LANGUAGE, “Chinese” ) OR EXCLUDE ( LANGUAGE, “German” ) OR EXCLUDE ( LANGUAGE, “Russian” ) ) |

| Embase | #22 #21 AND (2015:py OR 2016:py OR 2017:py OR 2018:py OR 2019:py OR 2020:py OR 2021:py OR 2022:py OR 2023:py OR 2024:py OR 2025:py) #21 #8 AND #14 AND #20 #20 #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 #19 ’emergency preparedness’ #18 ’mass casualty incident’ #17 ’mass disaster’ #16 ’disaster preparedness’ #15 ’disaster medicine’ #14 #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 #13 ’teaching’ #12 ’educational model’ #11 ’curriculum development’ #10 ’education program’ #9 ’simulation training’ #8 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 #7 ’health care personnel’ #6 ’nurse’ #5 ’medical intern’ #4 ’physician’ #3 ’medical student’ #2 ’first responder (person)’ #1 ’paramedical personnel’ |

| PsycNET |

((Any Field: (paramedic*) OR Any Field: (“first responders”) OR Any Field: (“medical student”) OR Any Field: (physician*) OR Any Field: (intern*) OR Any Field: (nurse*) OR Any Field: (“healthcare provider”))) AND ((Any Field: (“curriculum design”) OR Any Field: (“instructional design”) OR Any Field: (“educational strategies”) OR Any Field: (“simulation training”) OR Any Field: (education*) OR Any Field: (teaching) OR Any Field: (training))) AND ((Any Field: (“disaster medicine”) OR Any Field: (“disaster preparedness”) OR Any Field: (“mass casualty incident”) OR Any Field: (“emergency preparedness”))) AND Year: 2015 To 2025 |

| CINAHL | (paramedic* OR “first responders” OR “medical student” OR physician* OR intern* OR nurse* OR “healthcare provider” ) AND (“curriculum design” OR “instructional design” OR “educational strategies” OR “simulation training” OR education* OR teaching OR training ) AND (“disaster medicine” OR “disaster preparedness” OR “mass casualty incident” OR “emergency preparedness”) Filter: last 10 years |

| Cochrane | paramedic* OR “first responders” OR “medical student” OR physician* OR intern* OR nurse* OR “healthcare provider”) in Title Abstract Keyword AND (“curriculum design” OR “instructional design” OR “educational strategies” OR “simulation training” OR education* OR teaching OR training) in Title Abstract Keyword AND (“disaster medicine” OR “disaster preparedness” OR “mass casualty incident” OR “emergency preparedness”) in Title Abstract Keyword Filter: last 10 years |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | (paramedic* OR “first responders” OR “medical student” OR physician* OR intern* OR nurse* OR “healthcare provider” ) AND (“curriculum design” OR “instructional design” OR “educational strategies” OR “simulation training” OR education* OR teaching OR training ) AND (“disaster medicine” OR “disaster preparedness” OR “mass casualty incident” OR “emergency preparedness”) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).