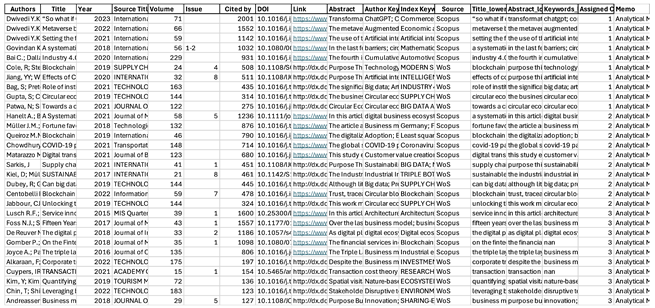

| No. |

Authors |

Title |

Year |

Source title |

DOI |

| 1 |

Dwivedi Y.K.; Kshetri N.; Hughes L.; Slade E.L.; Jeyaraj A.; Kar A.K.; Baabdullah A.M.; Koohang A.; Raghavan V.; Ahuja M.; Albanna H.; Albashrawi M.A.; Al-Busaidi A.S.; Balakrishnan J.; Barlette Y.; Basu S.; Bose I.; Brooks L.; Buhalis D.; Carter L.; Chowdhury S.; Crick T.; Cunningham S.W.; Davies G.H.; Davison R.M.; Dé R.; Dennehy D.; Duan Y.; Dubey R.; Dwivedi R.; Edwards J.S.; Flavián C.; Gauld R.; Grover V.; Hu M.-C.; Janssen M.; Jones P.; Junglas I.; Khorana S.; Kraus S.; Larsen K.R.; Latreille P.; Laumer S.; Malik F.T.; Mardani A.; Mariani M.; Mithas S.; Mogaji E.; Nord J.H.; O’Connor S.; Okumus F.; Pagani M.; Pandey N.; Papagiannidis S.; Pappas I.O.; Pathak N.; Pries-Heje J.; Raman R.; Rana N.P.; Rehm S.-V.; Ribeiro-Navarrete S.; Richter A.; Rowe F.; Sarker S.; Stahl B.C.; Tiwari M.K.; van der Aalst W.; Venkatesh V.; Viglia G.; Wade M.; Walton P.; Wirtz J.; Wright R. |

“So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy |

2023 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642 |

| 2 |

Ren S.; Zhang Y.; Liu Y.; Sakao T.; Huisingh D.; Almeida C.M.V.B. |

A comprehensive review of big data analytics throughout product lifecycle to support sustainable smart manufacturing: A framework, challenges and future research directions |

2019 |

Journal of Cleaner Production |

10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.025 |

| 3 |

Ibn-Mohammed T.; Mustapha K.B.; Godsell J.; Adamu Z.; Babatunde K.A.; Akintade D.D.; Acquaye A.; Fujii H.; Ndiaye M.M.; Yamoah F.A.; Koh S.C.L. |

A critical review of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies |

2021 |

Resources, Conservation and Recycling |

10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169 |

| 4 |

Liu, QL; Trevisan, AH; Yang, MY; Mascarenhas, J |

A framework of digital technologies for the circular economy: Digital functions and mechanisms |

2022 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT |

10.1002/bse.3015 |

| 5 |

Yadav G.; Luthra S.; Jakhar S.K.; Mangla S.K.; Rai D.P. |

A framework to overcome sustainable supply chain challenges through solution measures of industry 4.0 and circular economy: An automotive case |

2020 |

Journal of Cleaner Production |

10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120112 |

| 6 |

Freudenreich B.; Lüdeke-Freund F.; Schaltegger S. |

A Stakeholder Theory Perspective on Business Models: Value Creation for Sustainability |

2020 |

Journal of Business Ethics |

10.1007/s10551-019-04112-z |

| 7 |

Hanelt A.; Bohnsack R.; Marz D.; Antunes Marante C. |

A Systematic Review of the Literature on Digital Transformation: Insights and Implications for Strategy and Organizational Change |

2021 |

Journal of Management Studies |

10.1111/joms.12639 |

| 8 |

Govindan K.; Hasanagic M. |

A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: a supply chain perspective |

2018 |

International Journal of Production Research |

10.1080/00207543.2017.1402141 |

| 9 |

Cenamor J.; Rönnberg Sjödin D.; Parida V. |

Adopting a platform approach in servitization: Leveraging the value of digitalization |

2017 |

International Journal of Production Economics |

10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.12.033 |

| 10 |

Wunderlich, P; Veit, DJ; Sarker, S |

ADOPTION OF SUSTAINABLE TECHNOLOGIES: A MIXED-METHODS STUDY OF GERMAN HOUSEHOLDS |

2019 |

MIS QUARTERLY |

10.25300/MISQ/2019/12112 |

| 11 |

Ehlers, MH; Huber, R; Finger, R |

Agricultural policy in the era of digitalisation |

2021 |

FOOD POLICY |

10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.102019 |

| 12 |

Belhadi, A; Kamble, S; Gunasekaran, A; Mani, V |

Analyzing the mediating role of organizational ambidexterity and digital business transformation on industry 4.0 capabilities and sustainable supply chain performance |

2022 |

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT-AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL |

10.1108/SCM-04-2021-0152 |

| 13 |

Mukherjee, AA; Singh, RK; Mishra, R; Bag, S |

Application of blockchain technology for sustainability development in agricultural supply chain: justification framework |

2022 |

OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT RESEARCH |

10.1007/s12063-021-00180-5 |

| 14 |

Di Vaio A.; Palladino R.; Hassan R.; Escobar O. |

Artificial intelligence and business models in the sustainable development goals perspective: A systematic literature review |

2020 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.019 |

| 15 |

Goralski, MA; Tan, TK |

Artificial intelligence and sustainable development |

2020 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION |

10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100330 |

| 16 |

Toorajipour R.; Sohrabpour V.; Nazarpour A.; Oghazi P.; Fischl M. |

Artificial intelligence in supply chain management: A systematic literature review |

2021 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.009 |

| 17 |

Vrontis D.; Christofi M.; Pereira V.; Tarba S.; Makrides A.; Trichina E. |

Artificial intelligence, robotics, advanced technologies and human resource management: a systematic review |

2022 |

International Journal of Human Resource Management |

10.1080/09585192.2020.1871398 |

| 18 |

Rosa P.; Sassanelli C.; Urbinati A.; Chiaroni D.; Terzi S. |

Assessing relations between Circular Economy and Industry 4.0: a systematic literature review |

2020 |

International Journal of Production Research |

10.1080/00207543.2019.1680896 |

| 19 |

Culot G.; Nassimbeni G.; Orzes G.; Sartor M. |

Behind the definition of Industry 4.0: Analysis and open questions |

2020 |

International Journal of Production Economics |

10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107617 |

| 20 |

Dubey R.; Gunasekaran A.; Childe S.J.; Bryde D.J.; Giannakis M.; Foropon C.; Roubaud D.; Hazen B.T. |

Big data analytics and artificial intelligence pathway to operational performance under the effects of entrepreneurial orientation and environmental dynamism: A study of manufacturing organisations |

2020 |

International Journal of Production Economics |

10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.107599 |

| 21 |

Raut, RD; Mangla, SK; Narwane, VS; Dora, M; Liu, MQ |

Big Data Analytics as a mediator in Lean, Agile, Resilient, and Green (LARG) practices effects on sustainable supply chains |

2021 |

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH PART E-LOGISTICS AND TRANSPORTATION REVIEW |

10.1016/j.tre.2020.102170 |

| 22 |

Ferraris A.; Mazzoleni A.; Devalle A.; Couturier J. |

Big data analytics capabilities and knowledge management: impact on firm performance |

2019 |

Management Decision |

10.1108/MD-07-2018-0825 |

| 23 |

Awan, U; Shamim, S; Khan, Z; Zia, NU; Shariq, SM; Khan, MN |

Big data analytics capability and decision-making: The role of data-driven insight on circular economy performance |

2021 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120766 |

| 24 |

Coble, KH; Mishra, AK; Ferrell, S; Griffin, T |

Big Data in Agriculture: A Challenge for the Future |

2018 |

APPLIED ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVES AND POLICY |

10.1093/aepp/ppx056 |

| 25 |

Queiroz M.M.; Fosso Wamba S. |

Blockchain adoption challenges in supply chain: An empirical investigation of the main drivers in India and the USA |

2019 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.11.021 |

| 26 |

Frizzo-Barker J.; Chow-White P.A.; Adams P.R.; Mentanko J.; Ha D.; Green S. |

Blockchain as a disruptive technology for business: A systematic review |

2020 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.10.014 |

| 27 |

Friedman, N; Ormiston, J |

Blockchain as a sustainability-oriented innovation?: Opportunities for and resistance to Blockchain technology as a driver of sustainability in global food supply chains |

2022 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121403 |

| 28 |

Hughes L.; Dwivedi Y.K.; Misra S.K.; Rana N.P.; Raghavan V.; Akella V. |

Blockchain research, practice and policy: Applications, benefits, limitations, emerging research themes and research agenda |

2019 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.02.005 |

| 29 |

Upadhyay A.; Mukhuty S.; Kumar V.; Kazancoglu Y. |

Blockchain technology and the circular economy: Implications for sustainability and social responsibility |

2021 |

Journal of Cleaner Production |

10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126130 |

| 30 |

Kouhizadeh M.; Saberi S.; Sarkis J. |

Blockchain technology and the sustainable supply chain: Theoretically exploring adoption barriers |

2021 |

International Journal of Production Economics |

10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107831 |

| 31 |

Centobelli P.; Cerchione R.; Vecchio P.D.; Oropallo E.; Secundo G. |

Blockchain technology for bridging trust, traceability and transparency in circular supply chain |

2022 |

Information and Management |

10.1016/j.im.2021.103508 |

| 32 |

Cole, R; Stevenson, M; Aitken, J |

Blockchain technology: implications for operations and supply chain management |

2019 |

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT-AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL |

10.1108/SCM-09-2018-0309 |

| 33 |

Rogerson, M; Parry, GC |

Blockchain: case studies in food supply chain visibility |

2020 |

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT-AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL |

10.1108/SCM-08-2019-0300 |

| 34 |

Coreynen W.; Matthyssens P.; Van Bockhaven W. |

Boosting servitization through digitization: Pathways and dynamic resource configurations for manufacturers |

2017 |

Industrial Marketing Management |

10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.04.012 |

| 35 |

Andreassen, TW; Lervik-Olsen, L; Snyder, H; Van Riel, ACR; Sweeney, JC; Van Vaerenbergh, Y |

Business model innovation and value-creation: the triadic way |

2018 |

JOURNAL OF SERVICE MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/JOSM-05-2018-0125 |

| 36 |

Dubey, R; Gunasekaran, A; Childe, SJ; Papadopoulos, T; Luo, ZW; Wamba, SF; Roubaud, D |

Can big data and predictive analytics improve social and environmental sustainability? |

2019 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.020 |

| 37 |

Peng Y.; Tao C. |

Can digital transformation promote enterprise performance? —From the perspective of public policy and innovation |

2022 |

Journal of Innovation and Knowledge |

10.1016/j.jik.2022.100198 |

| 38 |

Gupta, S; Chen, HZ; Hazen, BT; Kaur, S; Gonzalez, EDRS |

Circular economy and big data analytics: A stakeholder perspective |

2019 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2018.06.030 |

| 39 |

Chaudhuri, A; Subramanian, N; Dora, M |

Circular economy and digital capabilities of SMEs for providing value to customers: Combined resource-based view and ambidexterity perspective |

2022 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.039 |

| 40 |

Pinheiro, MAP; Jugend, D; Jabbour, ABLD; Jabbour, CJC; Latan, H |

Circular economy-based new products and company performance: The role of stakeholders and Industry 4.0 technologies |

2022 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT |

10.1002/bse.2905 |

| 41 |

Dwivedi Y.K.; Hughes L.; Kar A.K.; Baabdullah A.M.; Grover P.; Abbas R.; Andreini D.; Abumoghli I.; Barlette Y.; Bunker D.; Chandra Kruse L.; Constantiou I.; Davison R.M.; De R.; Dubey R.; Fenby-Taylor H.; Gupta B.; He W.; Kodama M.; Mäntymäki M.; Metri B.; Michael K.; Olaisen J.; Panteli N.; Pekkola S.; Nishant R.; Raman R.; Rana N.P.; Rowe F.; Sarker S.; Scholtz B.; Sein M.; Shah J.D.; Teo T.S.H.; Tiwari M.K.; Vendelø M.T.; Wade M. |

Climate change and COP26: Are digital technologies and information management part of the problem or the solution? An editorial reflection and call to action |

2022 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102456 |

| 42 |

Kraus S.; Rehman S.U.; García F.J.S. |

Corporate social responsibility and environmental performance: The mediating role of environmental strategy and green innovation |

2020 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120262 |

| 43 |

Wang, CX; Zhang, QP; Zhang, W |

Corporate social responsibility, Green supply chain management and firm performance: The moderating role of big-data analytics capability |

2020 |

RESEARCH IN TRANSPORTATION BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT |

10.1016/j.rtbm.2020.100557 |

| 44 |

Ghobakhloo, M; Fathi, M |

Corporate survival in Industry 4.0 era: the enabling role of lean-digitized manufacturing |

2020 |

JOURNAL OF MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/JMTM-11-2018-0417 |

| 45 |

Alkaraan, F; Albitar, K; Hussainey, K; Venkatesh, VG |

Corporate transformation toward Industry 4.0 and financial performance: The influence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) |

2022 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121423 |

| 46 |

Amankwah-Amoah J.; Khan Z.; Wood G.; Knight G. |

COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration |

2021 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.011 |

| 47 |

Chowdhury P.; Paul S.K.; Kaisar S.; Moktadir M.A. |

COVID-19 pandemic related supply chain studies: A systematic review |

2021 |

Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

10.1016/j.tre.2021.102271 |

| 48 |

Kunz, W; Aksoy, L; Bart, Y; Heinonen, K; Kabadayi, S; Ordenes, FV; Sigala, M; Diaz, D; Theodoulidis, B |

Customer engagement in a Big Data world |

2017 |

JOURNAL OF SERVICES MARKETING |

10.1108/JSM-10-2016-0352 |

| 49 |

Gil-Gomez, H; Guerola-Navarro, V; Oltra-Badenes, R; Lozano-Quilis, JA |

Customer relationship management: digital transformation and sustainable business model innovation |

2020 |

ECONOMIC RESEARCH-EKONOMSKA ISTRAZIVANJA |

10.1080/1331677X.2019.1676283 |

| 50 |

Min, S; Zacharia, ZG; Smith, CD |

Defining Supply Chain Management: In the Past, Present, and Future |

2019 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS LOGISTICS |

10.1111/jbl.12201 |

| 51 |

Centobelli P.; Cerchione R.; Chiaroni D.; Del Vecchio P.; Urbinati A. |

Designing business models in circular economy: A systematic literature review and research agenda |

2020 |

Business Strategy and the Environment |

10.1002/bse.2466 |

| 52 |

Elia G.; Margherita A.; Passiante G. |

Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process |

2020 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119791 |

| 53 |

Paiola, M; Schiavone, F; Grandinetti, R; Chen, JS |

Digital servitization and sustainability through networking: Some evidences from IoT-based business models |

2021 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.047 |

| 54 |

Kohtamäki M.; Parida V.; Oghazi P.; Gebauer H.; Baines T. |

Digital servitization business models in ecosystems: A theory of the firm |

2019 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.027 |

| 55 |

Paschou T.; Rapaccini M.; Adrodegari F.; Saccani N. |

Digital servitization in manufacturing: A systematic literature review and research agenda |

2020 |

Industrial Marketing Management |

10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.012 |

| 56 |

Ivanov, D; Dolgui, A; Das, A; Sokolov, B |

Digital Supply Chain Twins: Managing the Ripple Effect, Resilience, and Disruption Risks by Data-Driven Optimization, Simulation, and Visibility |

2019 |

HANDBOOK OF RIPPLE EFFECTS IN THE SUPPLY CHAIN |

10.1007/978-3-030-14302-2_15 |

| 57 |

George G.; Merrill R.K.; Schillebeeckx S.J.D. |

Digital Sustainability and Entrepreneurship: How Digital Innovations Are Helping Tackle Climate Change and Sustainable Development |

2021 |

Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice |

10.1177/1042258719899425 |

| 58 |

Khan, SAR; Zia-ul-haq, HM; Umar, M; Yu, Z |

Digital technology and circular economy practices: An strategy to improve organizational performance |

2021 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND DEVELOPMENT |

10.1002/bsd2.176 |

| 59 |

Khan, SAR; Piprani, AZ; Yu, Z |

Digital technology and circular economy practices: future of supply chains |

2022 |

OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT RESEARCH |

10.1007/s12063-021-00247-3 |

| 60 |

Chen, PY; Hao, YY |

Digital transformation and corporate environmental performance: The moderating role of board characteristics |

2022 |

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT |

10.1002/csr.2324 |

| 61 |

Matarazzo M.; Penco L.; Profumo G.; Quaglia R. |

Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective |

2021 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.033 |

| 62 |

Kraus S.; Durst S.; Ferreira J.J.; Veiga P.; Kailer N.; Weinmann A. |

Digital transformation in business and management research: An overview of the current status quo |

2022 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102466 |

| 63 |

Kraus S.; Schiavone F.; Pluzhnikova A.; Invernizzi A.C. |

Digital transformation in healthcare: Analyzing the current state-of-research |

2021 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.030 |

| 64 |

Heilig, L; Lalla-Ruiz, E; Voss, S |

Digital transformation in maritime ports: analysis and a game theoretic framework |

2017 |

NETNOMICS |

10.1007/s11066-017-9122-x |

| 65 |

Dutta, G; Kumar, R; Sindhwani, R; Singh, RK |

Digital transformation priorities of India’s discrete manufacturing SMEs - a conceptual study in perspective of Industry 4.0 |

2020 |

COMPETITIVENESS REVIEW |

10.1108/CR-03-2019-0031 |

| 66 |

George, G; Schillebeeckx, SJD |

Digital transformation, sustainability, and purpose in the multinational enterprise |

2022 |

JOURNAL OF WORLD BUSINESS |

10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101326 |

| 67 |

Kamble, SS; Gunasekaran, A; Parekh, H; Mani, V; Belhadi, A; Sharma, R |

Digital twin for sustainable manufacturing supply chains: Current trends, future perspectives, and an implementation framework |

2022 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121448 |

| 68 |

Rachinger M.; Rauter R.; Müller C.; Vorraber W.; Schirgi E. |

Digitalization and its influence on business model innovation |

2019 |

Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management |

10.1108/JMTM-01-2018-0020 |

| 69 |

Chari, A; Niedenzu, D; Despeisse, M; Machado, CG; Azevedo, JD; Boavida-Dias, R; Johansson, B |

Dynamic capabilities for circular manufacturing supply chains-Exploring the role of Industry 4.0 and resilience |

2022 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT |

10.1002/bse.3040 |

| 70 |

Bag, S; Dhamija, P; Bryde, DJ; Singh, RK |

Effect of eco-innovation on green supply chain management, circular economy capability, and performance of small and medium enterprises |

2022 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.011 |

| 71 |

Jiang, YY; Wen, J |

Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: a perspective article |

2020 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/IJCHM-03-2020-0237 |

| 72 |

Agyabeng-Mensah, Y; Ahenkorah, E; Afum, E; Agyemang, AN; Agnikpe, C; Rogers, F |

Examining the influence of internal green supply chain practices, green human resource management and supply chain environmental cooperation on firm performance |

2020 |

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT-AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL |

10.1108/SCM-11-2019-0405 |

| 73 |

Bag, S; Gupta, S; Luo, ZW |

Examining the role of logistics 4.0 enabled dynamic capabilities on firm performance |

2020 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LOGISTICS MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/IJLM-11-2019-0311 |

| 74 |

Shahzad M.; Qu Y.; Zafar A.U.; Rehman S.U.; Islam T. |

Exploring the influence of knowledge management process on corporate sustainable performance through green innovation |

2020 |

Journal of Knowledge Management |

10.1108/JKM-11-2019-0624 |

| 75 |

Foss N.J.; Saebi T. |

Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How Far Have We Come, and Where Should We Go? |

2017 |

Journal of Management |

10.1177/0149206316675927 |

| 76 |

Müller J.M.; Buliga O.; Voigt K.-I. |

Fortune favors the prepared: How SMEs approach business model innovations in Industry 4.0 |

2018 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2017.12.019 |

| 77 |

El-Kassar A.-N.; Singh S.K. |

Green innovation and organizational performance: The influence of big data and the moderating role of management commitment and HR practices |

2019 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2017.12.016 |

| 78 |

Zameer, H; Wang, Y; Yasmeen, H; Mubarak, S |

Green innovation as a mediator in the impact of business analytics and environmental orientation on green competitive advantage |

2022 |

MANAGEMENT DECISION |

10.1108/MD-01-2020-0065 |

| 79 |

Broccardo, L; Zicari, A; Jabeen, F; Bhatti, ZA |

How digitalization supports a sustainable business model: A literature review |

2023 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122146 |

| 80 |

Cenamor J.; Parida V.; Wincent J. |

How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity |

2019 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.035 |

| 81 |

Li, K; Kim, DJ; Lang, KR; Kauffman, RJ; Naldi, M |

How should we understand the digital economy in Asia? Critical assessment and research agenda |

2020 |

ELECTRONIC COMMERCE RESEARCH AND APPLICATIONS |

10.1016/j.elerap.2020.101004 |

| 82 |

Zhu, SN; Song, JH; Hazen, BT; Lee, K; Cegielski, C |

How supply chain analytics enables operational supply chain transparency: An organizational information processing theory perspective |

2018 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/IJPDLM-11-2017-0341 |

| 83 |

Priyono A.; Moin A.; Putri V.N.A.O. |

Identifying digital transformation paths in the business model of smes during the covid-19 pandemic |

2020 |

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity |

10.3390/joitmc6040104 |

| 84 |

Jeble, S; Dubey, R; Childe, SJ; Papadopoulos, T; Roubaud, D; Prakash, A |

Impact of big data and predictive analytics capability on supply chain sustainability |

2018 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LOGISTICS MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/IJLM-05-2017-0134 |

| 85 |

Radicic, D; Petkovic, S |

Impact of digitalization on technological innovations in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) |

2023 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122474 |

| 86 |

Khan, SAR; Razzaq, A; Yu, Z; Miller, S |

Industry 4.0 and circular economy practices: A new era business strategies for environmental sustainability |

2021 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT |

10.1002/bse.2853 |

| 87 |

Di Maria, E; De Marchi, V; Galeazzo, A |

Industry 4.0 technologies and circular economy: The mediating role of supply chain integration |

2022 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT |

10.1002/bse.2940 |

| 88 |

Bai C.; Dallasega P.; Orzes G.; Sarkis J. |

Industry 4.0 technologies assessment: A sustainability perspective |

2020 |

International Journal of Production Economics |

10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107776 |

| 89 |

Rajput, S; Singh, SP |

Industry 4.0-challenges to implement circular economy |

2021 |

BENCHMARKING-AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL |

10.1108/BIJ-12-2018-0430 |

| 90 |

Irfan M.; Razzaq A.; Sharif A.; Yang X. |

Influence mechanism between green finance and green innovation: Exploring regional policy intervention effects in China |

2022 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121882 |

| 91 |

Denicolai, S; Zucchella, A; Magnani, G |

Internationalization, digitalization, and sustainability: Are SMEs ready? A survey on synergies and substituting effects among growth paths |

2021 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120650 |

| 92 |

Cui, YF; Liu, W; Rani, P; Alrasheedi, M |

Internet of Things (IoT) adoption barriers for the circular economy using Pythagorean fuzzy SWARA-CoCoSo decision-making approach in the manufacturing sector |

2021 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120951 |

| 93 |

Chin, T; Shi, Y; Singh, SK; Agbanyo, GK; Ferraris, A |

Leveraging blockchain technology for green innovation in ecosystem-based business models: A dynamic capability of values appropriation |

2022 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121908 |

| 94 |

Pizzi S.; Caputo A.; Corvino A.; Venturelli A. |

Management research and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs): A bibliometric investigation and systematic review |

2020 |

Journal of Cleaner Production |

10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124033 |

| 95 |

Eckhardt G.M.; Houston M.B.; Jiang B.; Lamberton C.; Rindfleisch A.; Zervas G. |

Marketing in the Sharing Economy |

2019 |

Journal of Marketing |

10.1177/0022242919861929 |

| 96 |

Dwivedi Y.K.; Hughes L.; Baabdullah A.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete S.; Giannakis M.; Al-Debei M.M.; Dennehy D.; Metri B.; Buhalis D.; Cheung C.M.K.; Conboy K.; Doyle R.; Dubey R.; Dutot V.; Felix R.; Goyal D.P.; Gustafsson A.; Hinsch C.; Jebabli I.; Janssen M.; Kim Y.-G.; Kim J.; Koos S.; Kreps D.; Kshetri N.; Kumar V.; Ooi K.-B.; Papagiannidis S.; Pappas I.O.; Polyviou A.; Park S.-M.; Pandey N.; Queiroz M.M.; Raman R.; Rauschnabel P.A.; Shirish A.; Sigala M.; Spanaki K.; Wei-Han Tan G.; Tiwari M.K.; Viglia G.; Wamba S.F. |

Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy |

2022 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102542 |

| 97 |

Constantiou I.D.; Kallinikos J. |

New games, new rules: Big data and the changing context of strategy |

2015 |

Journal of Information Technology |

10.1057/jit.2014.17 |

| 98 |

Gomber P.; Kauffman R.J.; Parker C.; Weber B.W. |

On the Fintech Revolution: Interpreting the Forces of Innovation, Disruption, and Transformation in Financial Services |

2018 |

Journal of Management Information Systems |

10.1080/07421222.2018.1440766 |

| 99 |

Ghosh, A; Edwards, DJ; Hosseini, MR |

Patterns and trends in Internet of Things (IoT) research: future applications in the construction industry |

2021 |

ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION AND ARCHITECTURAL MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/ECAM-04-2020-0271 |

| 100 |

Spring, M; Araujo, L |

Product biographies in servitization and the circular economy |

2017 |

INDUSTRIAL MARKETING MANAGEMENT |

10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.07.001 |

| 101 |

Acquier A.; Daudigeos T.; Pinkse J. |

Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework |

2017 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.006 |

| 102 |

Fernando Y.; Chiappetta Jabbour C.J.; Wah W.-X. |

Pursuing green growth in technology firms through the connections between environmental innovation and sustainable business performance: Does service capability matter? |

2019 |

Resources, Conservation and Recycling |

10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.09.031 |

| 103 |

Kim, Y; Kim, CK; Lee, DK; Lee, HW; Andrada, RT |

Quantifying nature-based tourism in protected areas in developing countries by using social big data |

2019 |

TOURISM MANAGEMENT |

10.1016/j.tourman.2018.12.005 |

| 104 |

Ullah, F; Qayyum, S; Thaheem, MJ; Al-Turjman, F; Sepasgozar, SME |

Risk management in sustainable smart cities governance: A TOE framework |

2021 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120743 |

| 105 |

Sivarajah, U; Irani, Z; Gupta, S; Mahroof, K |

Role of big data and social media analytics for business to business sustainability: A participatory web context |

2020 |

INDUSTRIAL MARKETING MANAGEMENT |

10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.04.005 |

| 106 |

Bag, S; Pretorius, JHC; Gupta, S; Dwivedi, YK |

Role of institutional pressures and resources in the adoption of big data analytics powered artificial intelligence, sustainable manufacturing practices and circular economy capabilities |

2021 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120420 |

| 107 |

Lusch R.F.; Nambisan S. |

Service innovation: A service-dominant logic perspective |

2015 |

MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems |

10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.1.07 |

| 108 |

Frank A.G.; Mendes G.H.S.; Ayala N.F.; Ghezzi A. |

Servitization and Industry 4.0 convergence in the digital transformation of product firms: A business model innovation perspective |

2019 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2019.01.014 |

| 109 |

Dwivedi Y.K.; Ismagilova E.; Hughes D.L.; Carlson J.; Filieri R.; Jacobson J.; Jain V.; Karjaluoto H.; Kefi H.; Krishen A.S.; Kumar V.; Rahman M.M.; Raman R.; Rauschnabel P.A.; Rowley J.; Salo J.; Tran G.A.; Wang Y. |

Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions |

2021 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102168 |

| 110 |

Cheng M. |

Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research |

2016 |

International Journal of Hospitality Management |

10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.003 |

| 111 |

Angelidou M. |

Smart cities: A conjuncture of four forces |

2015 |

Cities |

10.1016/j.cities.2015.05.004 |

| 112 |

Sjödin, DR; Parida, V; Leksell, M; Petrovic, A |

Smart Factory Implementation and Process Innovation A Preliminary Maturity Model for Leveraging Digitalization in Manufacturing |

2018 |

RESEARCH-TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT |

10.1080/08956308.2018.1471277 |

| 113 |

Büchi G.; Cugno M.; Castagnoli R. |

Smart factory performance and Industry 4.0 |

2020 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119790 |

| 114 |

Lerman, LV; Benitez, GB; Müller, JM; de Sousa, PR; Frank, AG |

Smart green supply chain management: a configurational approach to enhance green performance through digital transformation |

2022 |

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT-AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL |

10.1108/SCM-02-2022-0059 |

| 115 |

Buhalis, DT; O’Connor, P; Leung, R |

Smart hospitality: from smart cities and smart tourism towards agile business ecosystems in networked destinations |

2023 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/IJCHM-04-2022-0497 |

| 116 |

Knudsen, ES; Lien, LB; Timmermans, B; Belik, I; Pandey, S |

Stability in turbulent times? The effect of digitalization on the sustainability of competitive advantage |

2021 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.02.008 |

| 117 |

Dubey, R; Gunasekaran, A; Childe, SJ; Papadopoulos, T; Helo, P |

Supplier relationship management for circular economy Influence of external pressures and top management commitment |

2019 |

MANAGEMENT DECISION |

10.1108/MD-04-2018-0396 |

| 118 |

Del Giudice, M; Chierici, R; Mazzucchelli, A; Fiano, F |

Supply chain management in the era of circular economy: the moderating effect of big data |

2021 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LOGISTICS MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/IJLM-03-2020-0119 |

| 119 |

Sarkis, J |

Supply chain sustainability: learning from the COVID-19 pandemic |

2021 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS & PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT |

10.1108/IJOPM-08-2020-0568 |

| 120 |

Kiel D.; Müller J.M.; Arnold C.; Voigt K.-I. |

Sustainable industrial value creation: Benefits and challenges of industry 4.0 |

2017 |

International Journal of Innovation Management |

10.1142/S1363919617400151 |

| 121 |

Machado C.G.; Winroth M.P.; Ribeiro da Silva E.H.D. |

Sustainable manufacturing in Industry 4.0: an emerging research agenda |

2020 |

International Journal of Production Research |

10.1080/00207543.2019.1652777 |

| 122 |

Nam, T |

Technology usage, expected job sustainability, and perceived job insecurity |

2019 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2018.08.017 |

| 123 |

Yang, MY; Fu, MT; Zhang, ZH |

The adoption of digital technologies in supply chains: Drivers, process and impact |

2021 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120795 |

| 124 |

De Reuver M.; Sørensen C.; Basole R.C. |

The digital platform: A research agenda |

2018 |

Journal of Information Technology |

10.1057/s41265-016-0033-3 |

| 125 |

Li F. |

The digital transformation of business models in the creative industries: A holistic framework and emerging trends |

2020 |

Technovation |

10.1016/j.technovation.2017.12.004 |

| 126 |

Yin Y.; Stecke K.E.; Li D. |

The evolution of production systems from Industry 2.0 through Industry 4.0 |

2018 |

International Journal of Production Research |

10.1080/00207543.2017.1403664 |

| 127 |

Morrar, R; Arman, H; Mousa, S |

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0): A Social Innovation Perspective |

2017 |

TECHNOLOGY INNOVATION MANAGEMENT REVIEW |

10.22215/timreview/1117 |

| 128 |

Carayannis, EG; Morawska-Jancelewicz, J |

The Futures of Europe: Society 5.0 and Industry 5.0 as Driving Forces of Future Universities |

2022 |

JOURNAL OF THE KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY |

10.1007/s13132-021-00854-2 |

| 129 |

Ruhlandt R.W.S. |

The governance of smart cities: A systematic literature review |

2018 |

Cities |

10.1016/j.cities.2018.02.014 |

| 130 |

Benzidia S.; Makaoui N.; Bentahar O. |

The impact of big data analytics and artificial intelligence on green supply chain process integration and hospital environmental performance |

2021 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120557 |

| 131 |

Nayal, K; Raut, RD; Yadav, VS; Priyadarshinee, P; Narkhede, BE |

The impact of sustainable development strategy on sustainable supply chain firm performance in the digital transformation era |

2022 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT |

10.1002/bse.2921 |

| 132 |

Ng I.C.L.; Wakenshaw S.Y.L. |

The Internet-of-Things: Review and research directions |

2017 |

International Journal of Research in Marketing |

10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.11.003 |

| 133 |

Kohtamäki M.; Parida V.; Patel P.C.; Gebauer H. |

The relationship between digitalization and servitization: The role of servitization in capturing the financial potential of digitalization |

2020 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119804 |

| 134 |

Khan, SAR; Yu, Z; Sarwat, S; Godil, DI; Amin, S; Shujaat, S |

The role of block chain technology in circular economy practices to improve organisational performance |

2022 |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LOGISTICS-RESEARCH AND APPLICATIONS |

10.1080/13675567.2021.1872512 |

| 135 |

Bag, S; Rahinan, MS |

The role of capabilities in shaping sustainable supply chain flexibility and enhancing circular economy-target performance: an empirical study |

2023 |

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT-AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL |

10.1108/SCM-05-2021-0246 |

| 136 |

Kathan, W; Matzler, K; Veider, V |

The sharing economy: Your business model’s friend or foe? |

2016 |

BUSINESS HORIZONS |

10.1016/j.bushor.2016.06.006 |

| 137 |

Kristoffersen E.; Blomsma F.; Mikalef P.; Li J. |

The smart circular economy: A digital-enabled circular strategies framework for manufacturing companies |

2020 |

Journal of Business Research |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.044 |

| 138 |

Sarker S.; Chatterjee S.; Xiao X.; Elbanna A. |

The sociotechnical axis of cohesion for the IS discipline: Its historical legacy and its continued relevance |

2019 |

MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems |

10.25300/MISQ/2019/13747 |

| 139 |

Joyce A.; Paquin R.L. |

The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models |

2016 |

Journal of Cleaner Production |

10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067 |

| 140 |

Papadopoulos T.; Baltas K.N.; Balta M.E. |

The use of digital technologies by small and medium enterprises during COVID-19: Implications for theory and practice |

2020 |

International Journal of Information Management |

10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102192 |

| 141 |

Opresnik D.; Taisch M. |

The value of big data in servitization |

2015 |

International Journal of Production Economics |

10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.12.036 |

| 142 |

Cai, YZ; Etzkowitz, H |

Theorizing the Triple Helix model: Past, present, and future |

2021 |

TRIPLE HELIX |

10.1163/21971927-bja10003 |

| 143 |

Wurth B.; Stam E.; Spigel B. |

Toward an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Research Program |

2022 |

Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice |

10.1177/1042258721998948 |

| 144 |

Patwa, N; Sivarajah, U; Seetharaman, A; Sarkar, S; Maiti, K; Hingorani, K |

Towards a circular economy: An emerging economies context |

2021 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH |

10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.015 |

| 145 |

Urbinati A.; Chiaroni D.; Chiesa V. |

Towards a new taxonomy of circular economy business models |

2017 |

Journal of Cleaner Production |

10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.047 |

| 146 |

Biswas, D; Jalali, H; Ansaripoor, AH; De Giovanni, P |

Traceability vs. sustainability in supply chains: The implications of blockchain |

2023 |

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF OPERATIONAL RESEARCH |

10.1016/j.ejor.2022.05.034 |

| 147 |

Cuypers, IRP; Hennart, JF; Silverman, BS; Ertug, G |

TRANSACTION COST THEORY: PAST PROGRESS, CURRENT CHALLENGES, AND SUGGESTIONS FOR THE FUTURE |

2021 |

ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT ANNALS |

10.5465/annals.2019.0051 |

| 148 |

Yigitcanlar T.; Kamruzzaman M.; Buys L.; Ioppolo G.; Sabatini-Marques J.; da Costa E.M.; Yun J.J. |

Understanding ‘smart cities’: Intertwining development drivers with desired outcomes in a multidimensional framework |

2018 |

Cities |

10.1016/j.cities.2018.04.003 |

| 149 |

Täuscher K.; Laudien S.M. |

Understanding platform business models: A mixed methods study of marketplaces |

2018 |

European Management Journal |

10.1016/j.emj.2017.06.005 |

| 150 |

Appio F.P.; Lima M.; Paroutis S. |

Understanding Smart Cities: Innovation ecosystems, technological advancements, and societal challenges |

2019 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2018.12.018 |

| 151 |

Jabbour, CJC; Jabbour, ABLD; Sarkis, J; Godinho, M |

Unlocking the circular economy through new business models based on large-scale data: An integrative framework and research agenda |

2019 |

TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE |

10.1016/j.techfore.2017.09.010 |

| 152 |

Chowdhury S.; Dey P.; Joel-Edgar S.; Bhattacharya S.; Rodriguez-Espindola O.; Abadie A.; Truong L. |

Unlocking the value of artificial intelligence in human resource management through AI capability framework |

2023 |

Human Resource Management Review |

10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100899 |

| 153 |

Gomes L.A.D.V.; Facin A.L.F.; Salerno M.S.; Ikenami R.K. |

Unpacking the innovation ecosystem construct: Evolution, gaps and trends |

2018 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.009 |

| 154 |

Kumar, S; Sureka, R; Lim, WM; Mangla, SK; Goyal, N |

What do we know about business strategy and environmental research? Insights from Business Strategy and the Environment |

2021 |

BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT |

10.1002/bse.2813 |

| 155 |

de Sousa Jabbour A.B.L.; Jabbour C.J.C.; Foropon C.; Filho M.G. |

When titans meet – Can industry 4.0 revolutionise the environmentally-sustainable manufacturing wave? The role of critical success factors |

2018 |

Technological Forecasting and Social Change |

10.1016/j.techfore.2018.01.017 |