Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Sample Collections

2.2. Sample Collection and CTC Enrichment

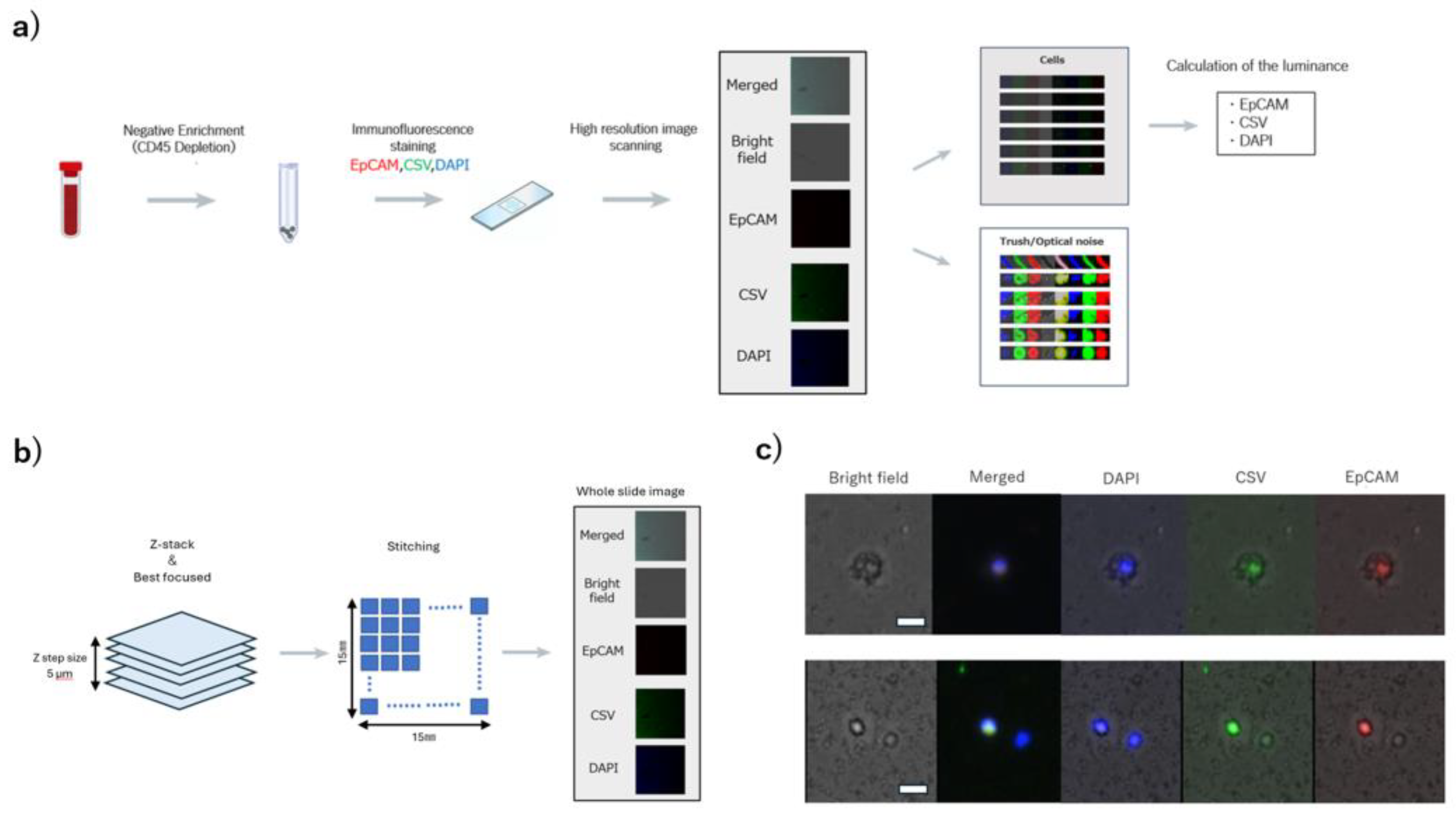

2.3. High-Resolution Image Scanning and Image Processing

2.3.1. Detection of Cellular Regions

2.3.2. Calculation of the Average Luminance of Cellular Regions

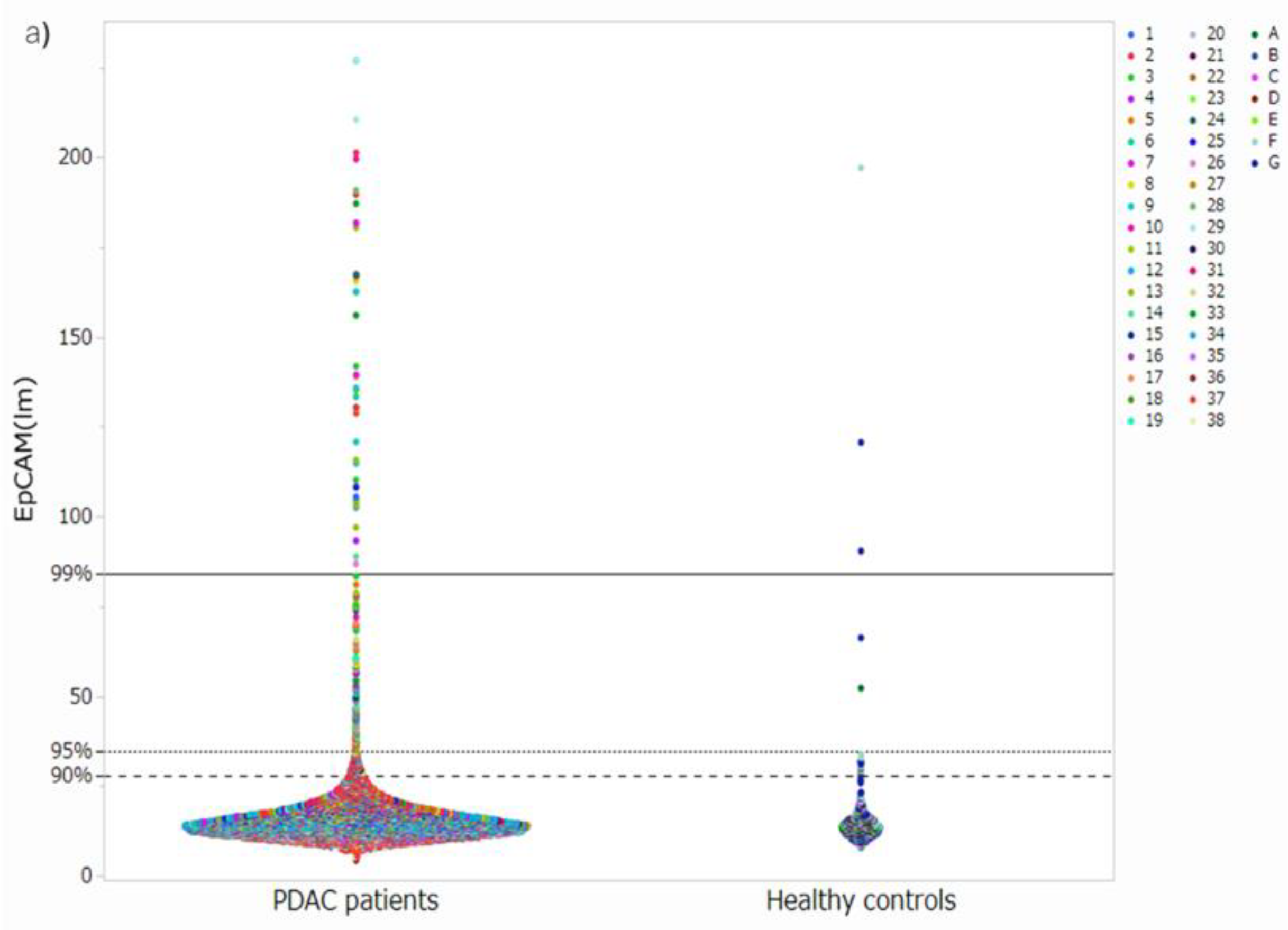

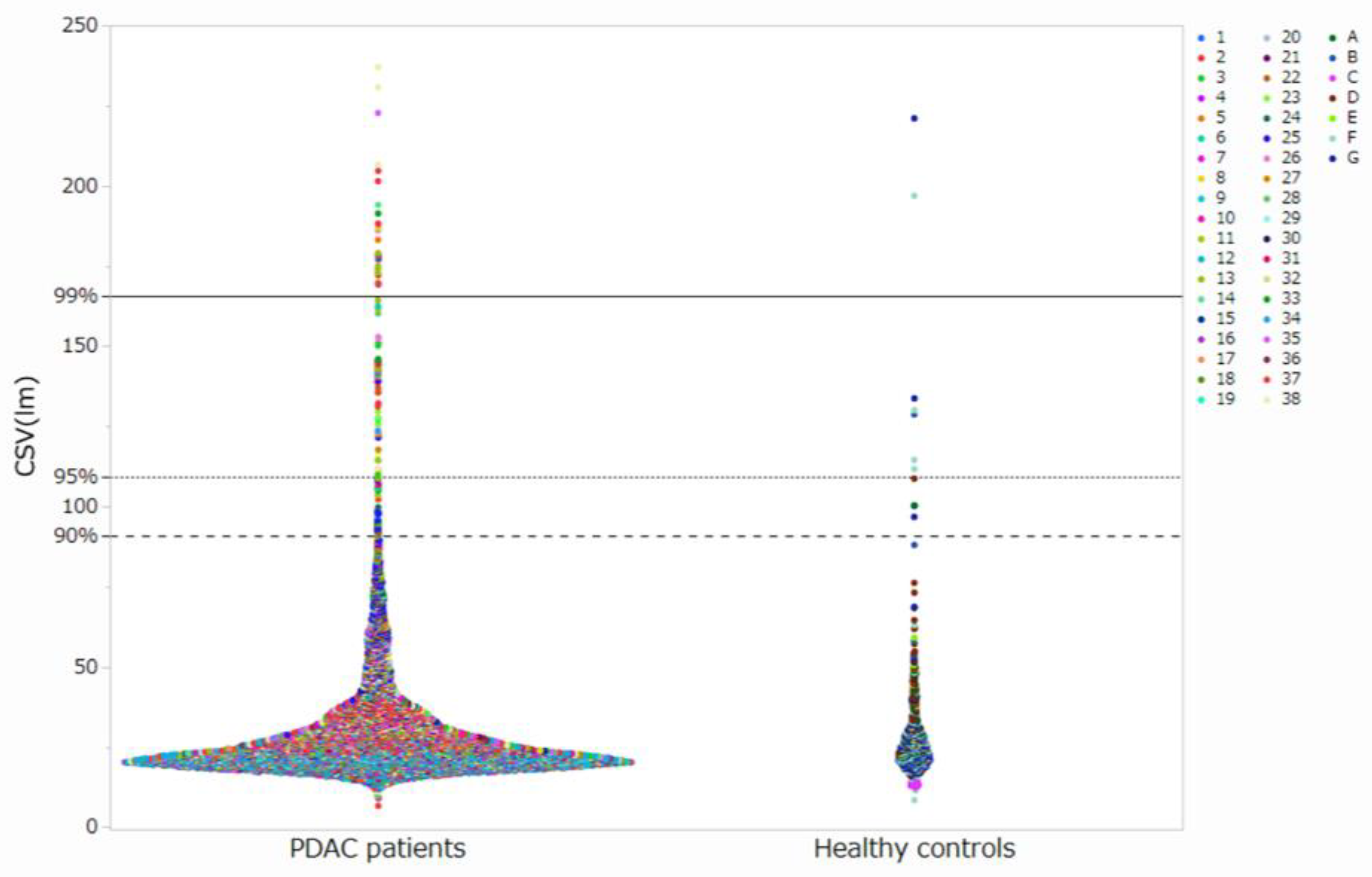

2.4. Threshold Settings

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Acquisition of Cell Images and Measurement of Luminance

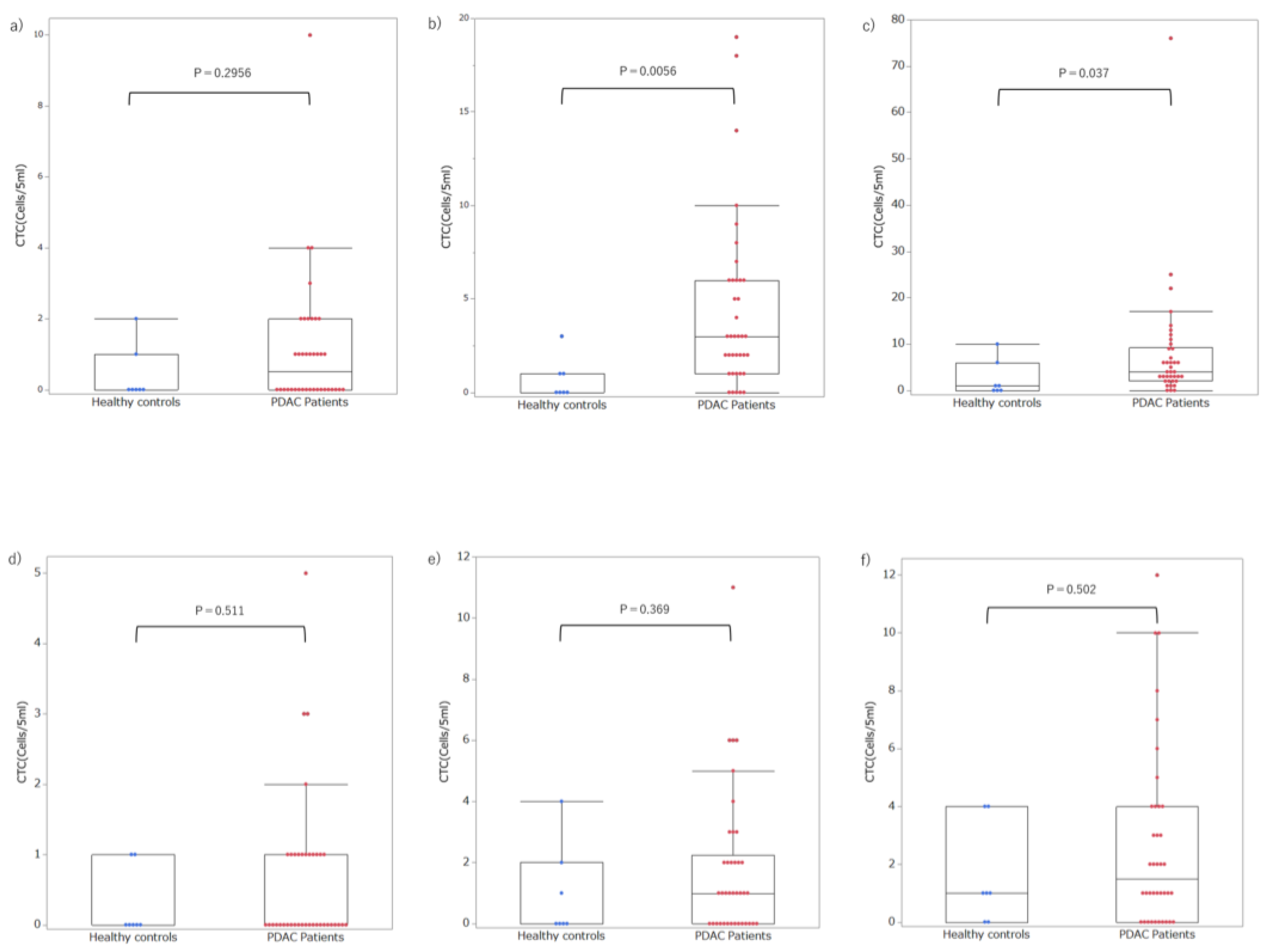

3.2. Setting Thresholds and Counting CTC Candidate Cells at Each Threshold

3.3. Setting Optimal Thresholds and Distributions of CTCs in Patients with PDAC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| CTC | Circulating tumor cells |

| CSV | Cell surface vimentin |

| UICC | Union for International Cancer Control |

| DAPI | 4′, 1, 6′- diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristics |

| AUC | Areas under the curve |

| SN | Sensitivity |

| SP | Specificity |

| DL | Deep learning |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, T.; Yamada, S.; Hoshino, Y.; Murotani, K.; Baba, H.; Takami, H.; Yoshioka, I.; Shibuya, K.; Kodera, Y.; Fujii, T. Prognostic factors in conversion surgery following nab-paclitaxel with gemcitabine and subsequent chemoradiotherapy for unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer: Results of a dual-center study. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 2023, 7, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, M.; Fujii, T.; Takami, H.; Suenaga, M.; Inokawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Nakayama, G.; Sugimoto, H.; Koike, M.; Nomoto, S.; et al. Combination of the serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 and carcinoembryonic antigen is a simple and accurate predictor of mortality in pancreatic cancer patients. Surg Today 2014, 44, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabel, L.; Proudhon, C.; Gortais, H.; Loirat, D.; Coussy, F.; Pierga, J.Y.; Bidard, F.C. Circulating tumor cells: Clinical validity and utility. Int J Clin Oncol 2017, 22, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, D.; Bastian, A.; Strauss, H.; Saxena, P.; Grimison, P.; Rasko, J.E.J. Exploring the clinical utility of pancreatic cancer circulating tumor cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, W.J.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Repollet, M.; Connelly, M.C.; Rao, C.; Tibbe, A.G.J.; Uhr, J.W.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10, 6897–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, C.M.; Hübler, R.; Figge, M.T. Automated classification of circulating tumor cells and the impact of Interobsever variability on classifier training and performance. J Immunol Res 2015, 2015, 573165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akashi, T.; Okumura, T.; Terabayashi, K.; Yoshino, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Yamazaki, T.; Numata, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Manabe, T.; Baba, H.; et al. The use of an artificial intelligence algorithm for circulating tumor cell detection in patients with esophageal cancer. Oncol Lett 2023, 26, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zeune, L.L.; Boink, Y.E.; van Dalum, G.; Nanou, A.; de Wit, S.; Andree, K.C.; Swennenhuis, J.F.; van Gils, S.A.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; Brune, C. Deep learning of circulating tumour cells. Nat Mach Intell 2020, 2, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Rawal, S.; Brown, R.; Zhou, H.; Agarwal, A.; Watson, M.A.; Cote, R.J.; Yang, C. Automatic detection of circulating tumor cells and cancer associated fibroblasts using deep learning. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Wittekind, C. TNM classification of malignant tumor; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom.

- Akita, H.; Nagano, H.; Takeda, Y.; Eguchi, H.; Wada, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Marubashi, S.; Tanemura, M.; Takahashi, H.; Ohigashi, H.; et al. Ep-CAM is a significant prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer patients by suppressing cell activity. Oncogene 2011, 30, 3468–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentink, A.; Isebia, K.T.; Kraan, J.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; Stevens, M. Measuring antigen expression of cancer cell lines and circulating tumour cells. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolazzo, C.; Gradilone, A.; Loreni, F.; Raimondi, C.; Gazzaniga, P. EpCAM: low circulating tumor cells: Gold in the waste. Dis Markers 2019, 2019, 1718920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.G.; Chianese, D.; Doyle, G.V.; Miller, M.C.; Russell, T.; Sanders, R.A.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Expression of epithelial cell adhesion molecule in carcinoma cells present in blood and primary and metastatic tumors. Int J Oncol 2005, 27, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satelli, A.; Mitra, A.; Brownlee, Z.; Xia, X.; Bellister, S.; Overman, M.J.; Kopetz, S.; Ellis, L.M.; Meng, Q.H.; Li, S. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitioned circulating tumor cells capture for detecting tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Ma, T.; Li, G.; et al. Vimentin-positive circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for diagnosis and treatment monitoring in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett 2019, 452, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemenetzis, G.; Groot, V.P.; Yu, J.; Ding, D.; Teinor, J.A.; Javed, A.A.; Wood, L.D.; Burkhart, R.A.; Cameron, J.L.; Makary, M.A.; et al. Circulating tumor cells dynamics in pancreatic adenocarcinoma correlate with disease status: Results of the prospective CLUSTER study. Ann Surg 2018, 268, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poruk, K.E.; Valero, V.; III; Saunders, T. ; Blackford, A.L.; Griffin, J.F.; Poling, J.; Hruban, R.H.; Anders, R.A.; Herman, J.; Zheng, L.; et al.: Circulating tumor cell phenotype predicts recurrence and survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2016, 264, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poruk, K.E.; Valero, V.; Saunders, T.; Blackford, A.L.; Griffin, J.F.; Poling, J.; Hruban, R.H.; Anders, R.A.; Herman, J.; Zheng, L.; et al. : Circulating tumor cell phenotype predicts recurrence and survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2016, 264, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; He, W.; Yang, J.; Ye, Q.; Cheng, L.; Pan, Y.; Mao, L.; Chu, X.; Lu, C.; Li, G.; et al. Ligand-targeted polymerase chain reaction for the detection of folate receptor-positive circulating tumour cells as a potential diagnostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer. Cell Prolif 2020, 53, e12880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.; Tan, X. A combination of circulating tumor cells and CA199 improves the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. J Clin Lab Anal 2022, 36, e24341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankeny, J.S.; Court, C.M.; Hou, S.; Li, Q.; Song, M.; Wu, D.; Chen, J.F.; Lee, T.; Lin, M.; Sho, S.; et al. Circulating tumour cells as a biomarker for diagnosis and staging in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2016, 114, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukasawa, M.; Watanabe, T.; Tanaka, H.; Itoh, A.; Kimura, N.; Shibuya, K.; Yoshioka, I.; Murotani, K.; Hirabayashi, K.; Fujii, T. Efficacy of staging laparoscopy for resectable pancreatic cancer on imaging and the therapeutic effect of systemic chemotherapy for positive peritoneal cytology. J Hepato-Bil Pancreat Sci 2023, 30, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Court, C.M.; Ankeny, J.S.; Sho, S.; Winograd, P.; Hou, S.; Song, M.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Girgis, M.D.; Graeber, T.G.; Agopian, V.G.; et al. Circulating tumor cells predict occult metastatic disease and prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2018, 25, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissolati, M.; Sandri, M.T.; Burtulo, G.; Zorzino, L.; Balzano, G.; Braga, M. Portal vein-circulating tumor cells predict liver metastases in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. Tumour Biol 2015, 36, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubo, K.; Uenosono, Y.; Arigami, T.; Mataki, Y.; Matsushita, D.; Yanagita, S.; Kurahara, H.; Sakoda, M.; Kijima, Y.; Maemura, K.; et al. Clinical impact of circulating tumor cells and therapy response in pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017, 43, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, V.; Timme-Bronsert, S.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Hoeppner, J.; Kulemann, B. Circulating tumor cells in pancreatic cancer: Current perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

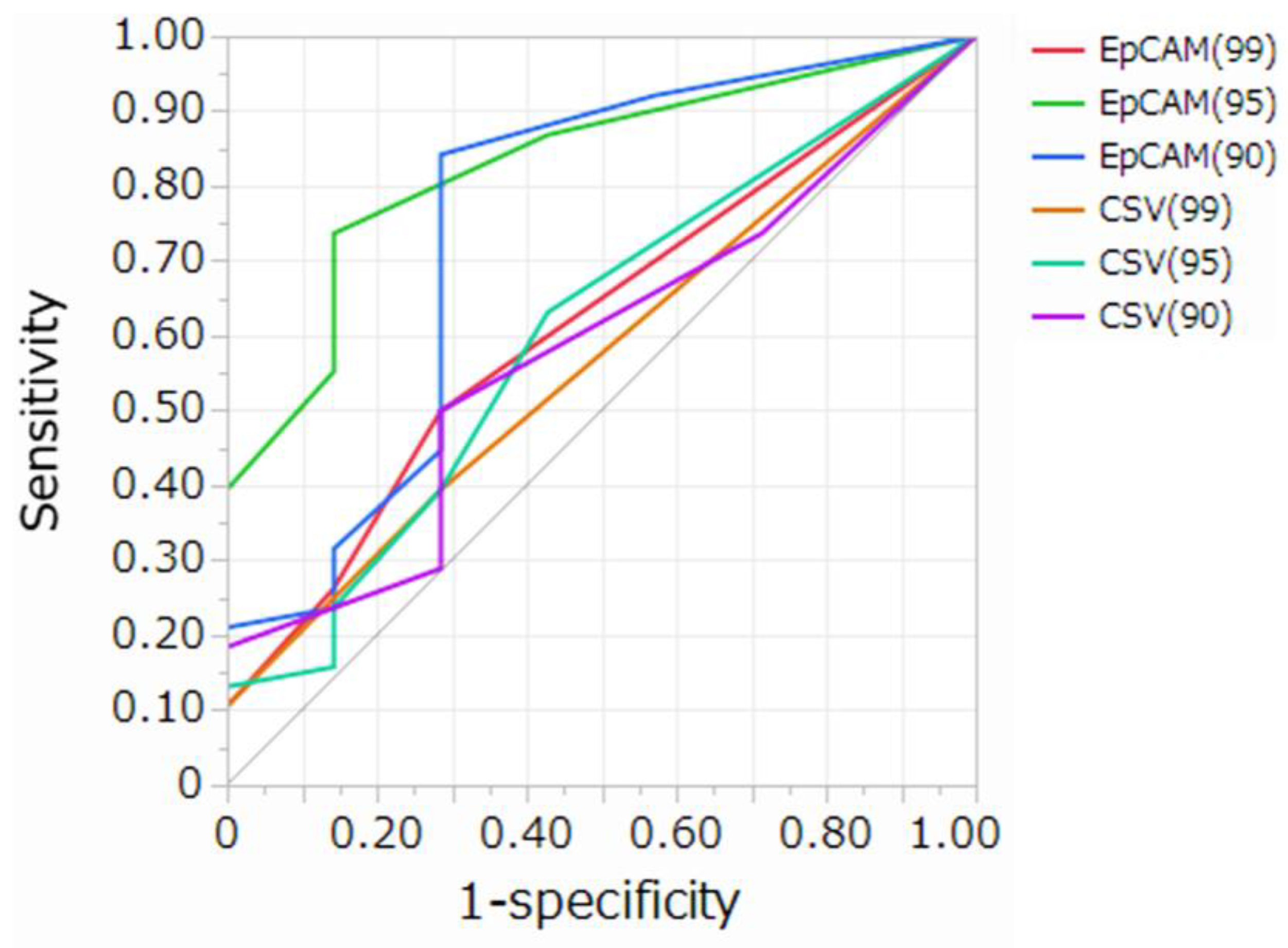

|

Cut-off value (Cells/5mL) |

AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Delong test p-value | ||||||

| EpCAM (99) |

EpCAM (95) |

EpCAM (90) |

CSV (99) | CSV (95) | CSV (90) | |||||

| EpCAM (99) | 1 | 0.617(0.414-0.785) | 0.50 | 0.72 | 1.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0063 | 0.3932 | 0.8864 | 0.6209 |

| EpCAM (95) | 2 | 0.830(0.634-0.932) | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.0002 | 1.0000 | 0.2704 | 0.0002 | 0.0201 | 0.0021 |

| EpCAM (90) | 2 | 0.750(0.456-0.914) | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.0063 | 0.2704 | 1.0000 | 0.0025 | 0.0551 | 0.0087 |

| CSV (99) | 1 | 0.570(0.386-0.736) | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.3932 | 0.0002 | 0.0025 | 1.0000 | 0.5453 | 0.8480 |

| CSV (95) | 1 | 0.605(0.372-0.799) | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.8864 | 0.0201 | 0.0551 | 0.5453 | 1.0000 | 0.6510 |

| CSV (90) | 2 | 0.581(0.362-0.772) | 0.50 | 0.72 | 0.6209 | 0.0021 | 0.0087 | 0.6510 | 0.8480 | 1.0000 |

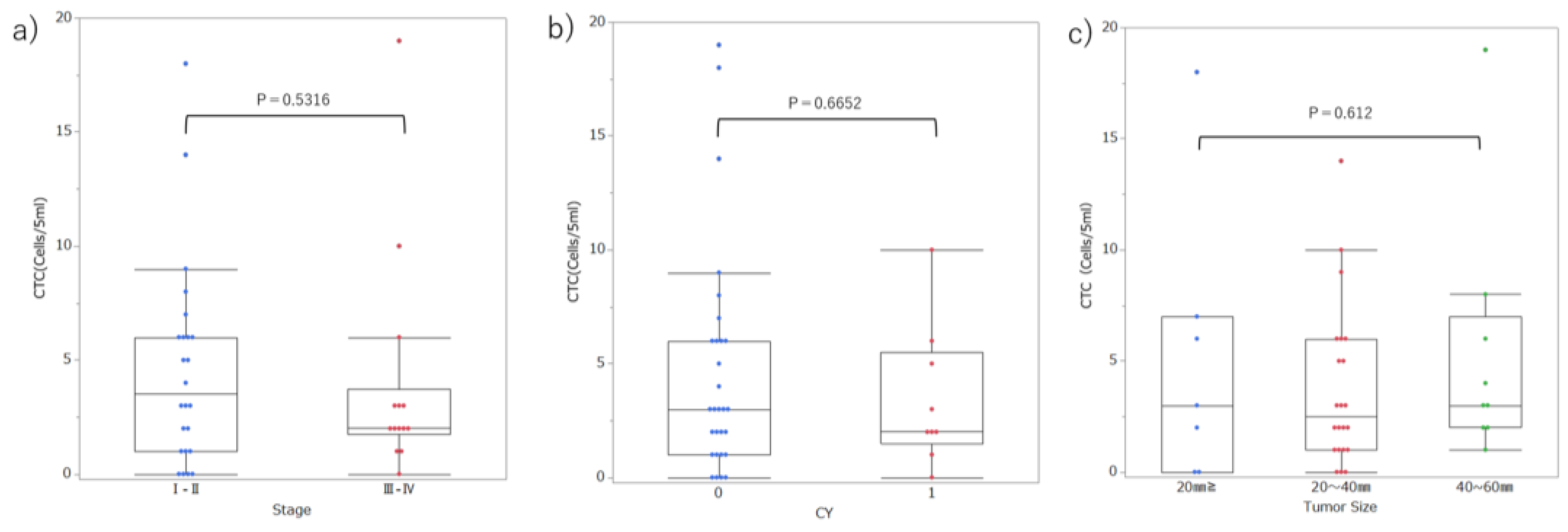

| CTC≥2 | 2 > CTC | p-value | ||

| Age | 67.1 (58–75) | 72.9 (62–84) | 0.079 | |

| Sex | Male | 19 | 7 | 0.733 |

| Female | 9 | 3 | ||

| Location | Head/Neck | 11 | 7 | 0.092 |

| Body/Tail | 18 | 3 | ||

| UICC Stage | I–II | 17 | 7 | 0.598 |

| III–IV | 11 | 3 | ||

| Tumor size | TS1-2 | 20 | 9 | 0.290 |

| TS3-4 | 8 | 1 | ||

| CY | 0 | 21 | 8 | 0.747 |

| 1 | 7 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).