Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Procedures

2.2. Chemotherapy Protocol

2.3. Data Collection

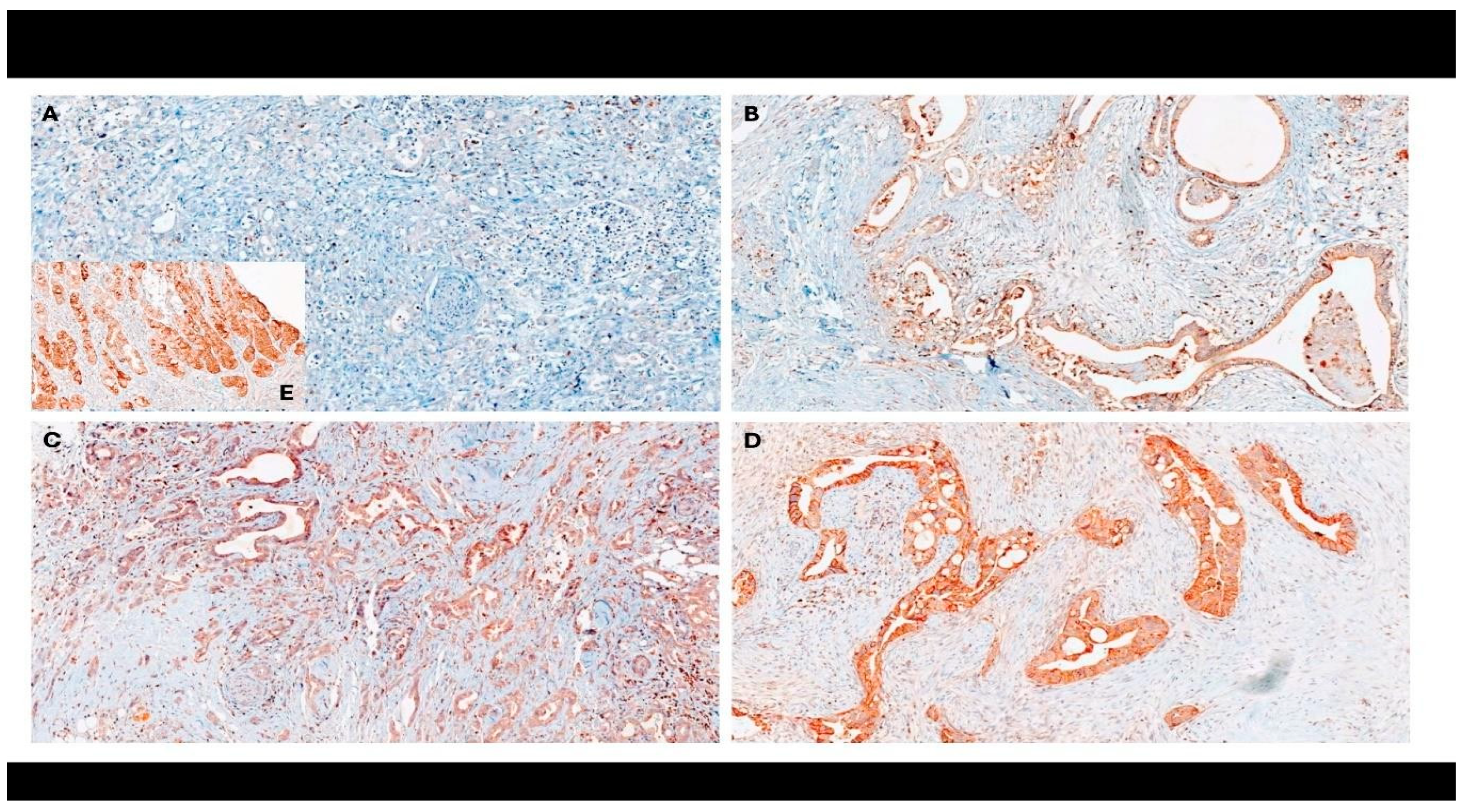

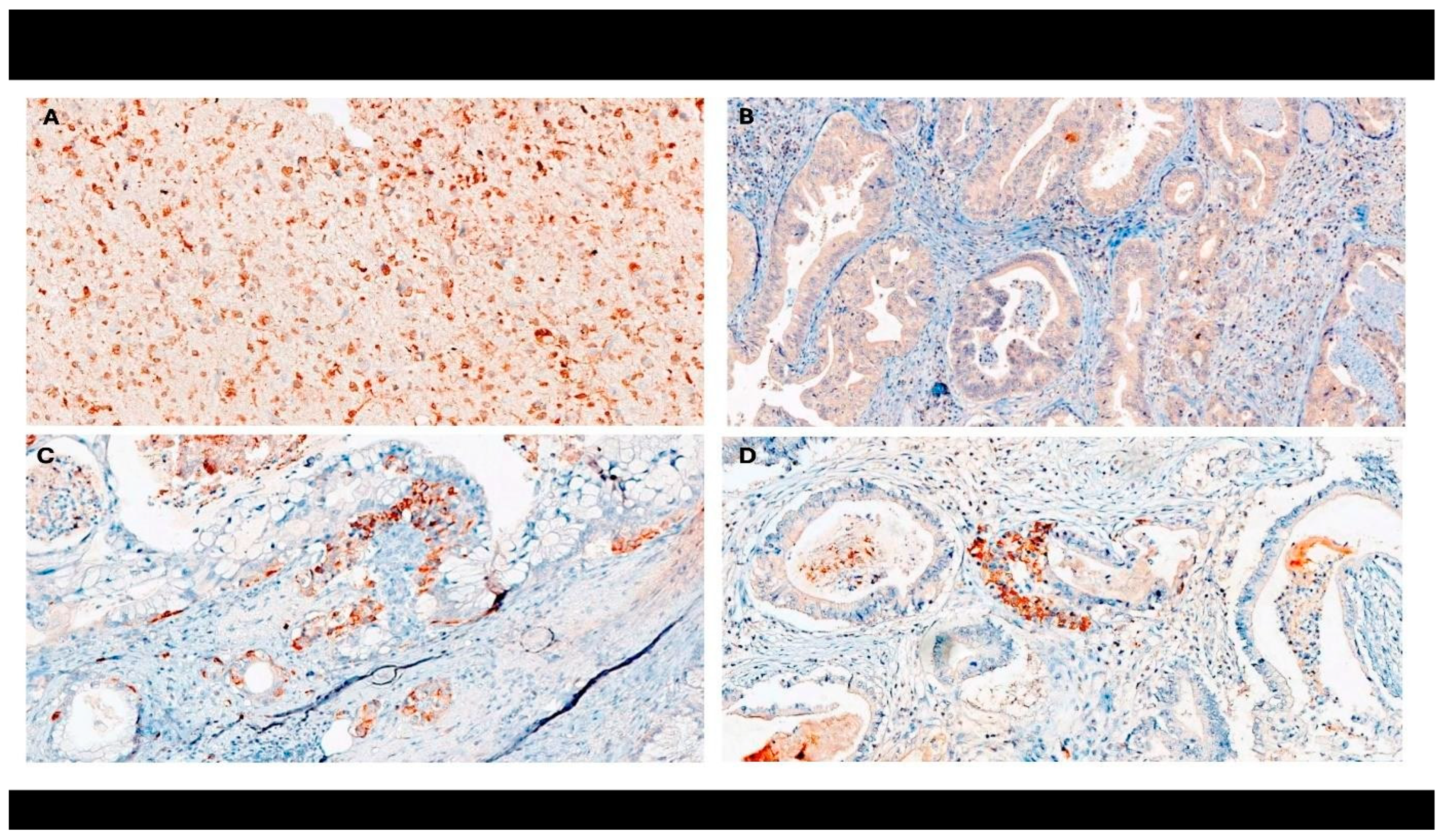

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

2.5. Calculation of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio

2.6. Survival Endpoints

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

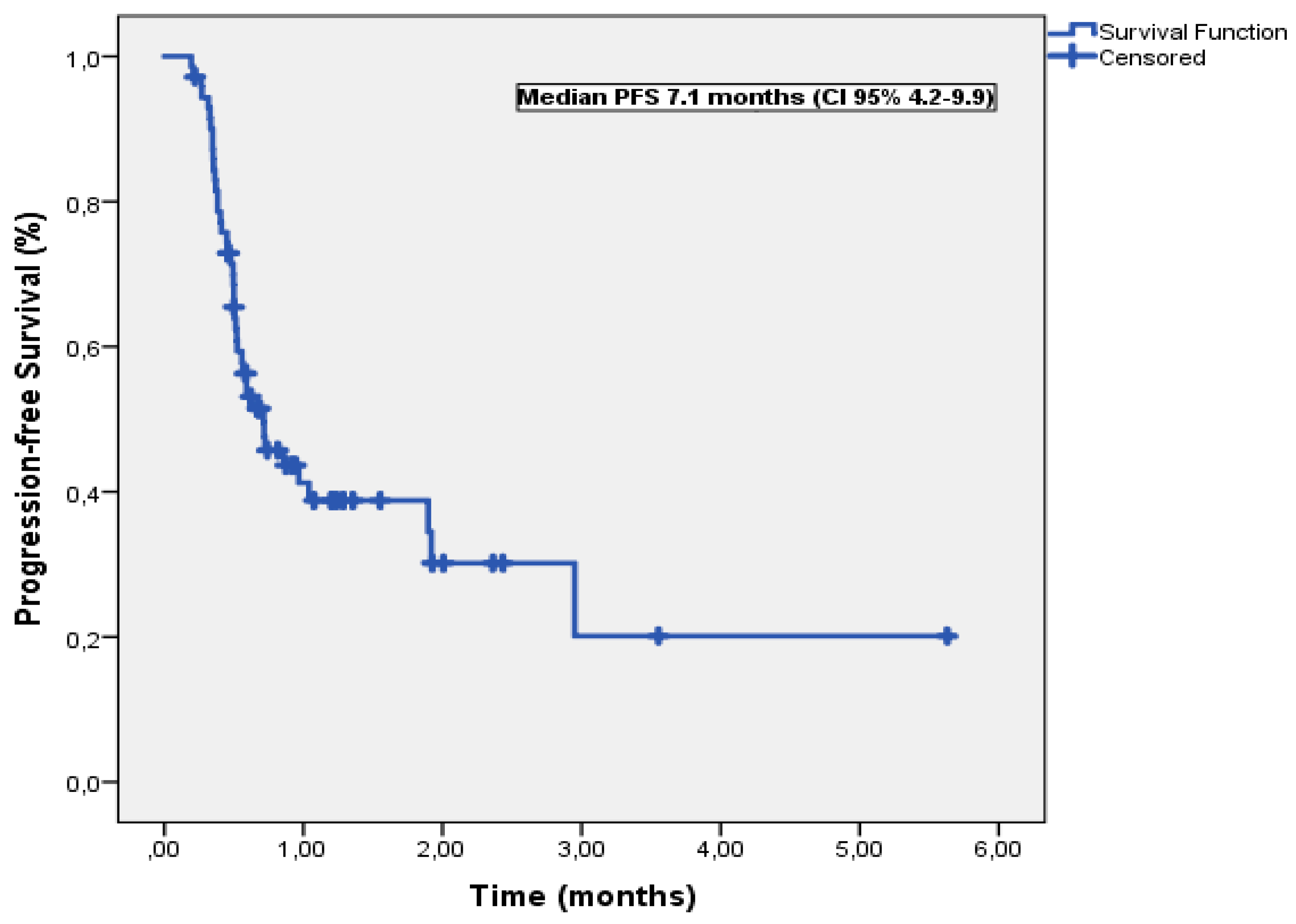

3.2. Progression-Free Survival

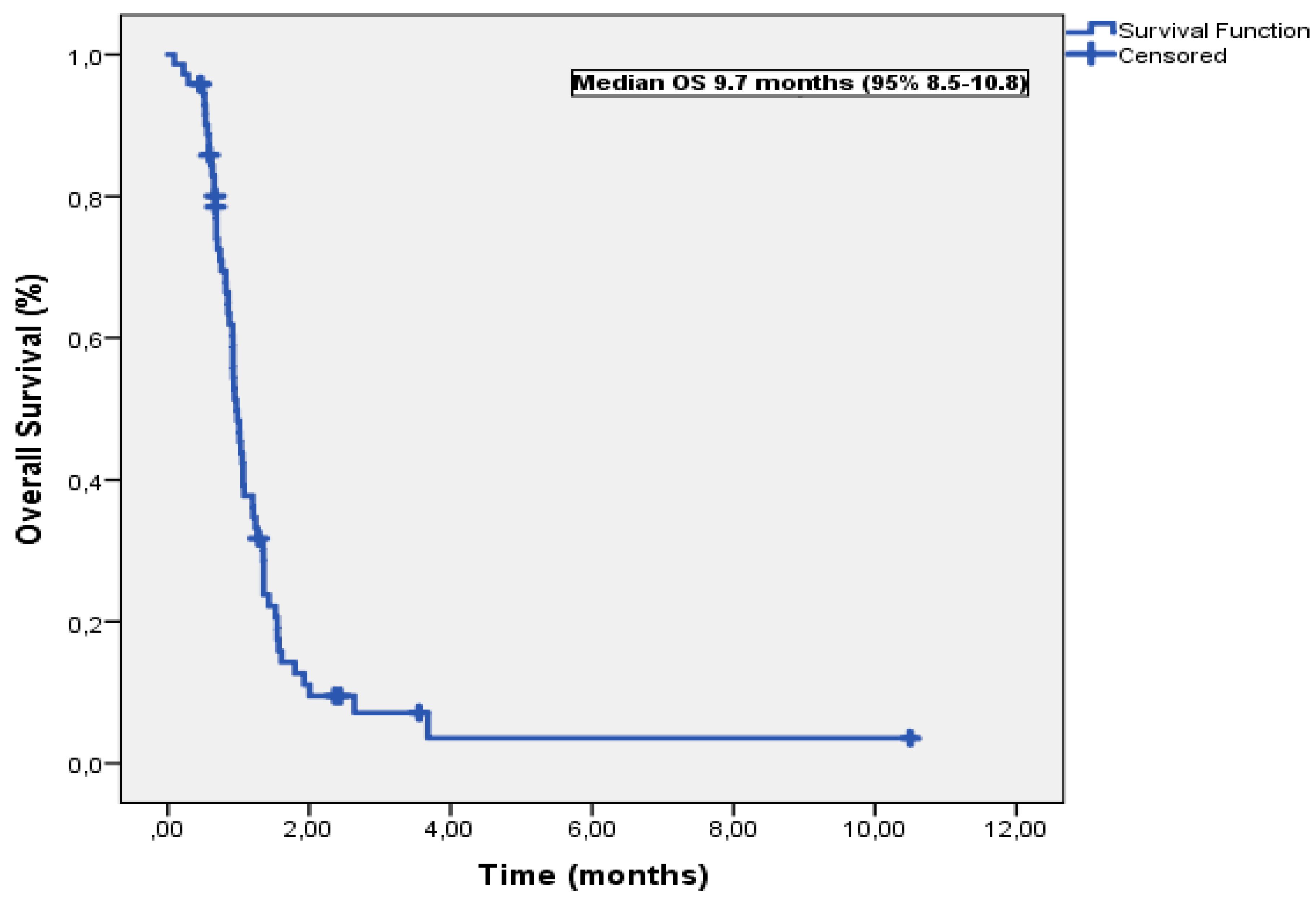

3.3. Overall Survival

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park W, Chawla A, O’Reilly EM. Pancreatic cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021; 326:851- 862. [CrossRef]

- Ushio J, Kanno A, Ikeda E, Ando K, Nagai H, Miwata T, Kawasaki Y, Tada Y, Yokoyama K, Numao N, Tamada K, Lefor AK, Yamamoto H. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021; 11:562. [CrossRef]

- Bekkali NLH, Oppong KW. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma epidemiology and risk assessment: Could we prevent? Possibility for an early diagnosis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6(Suppl 3): S58-S61. [CrossRef]

- Principe DR, Underwood PW, Korc M, Trevino JG, Munshi HG, Rana A. The current treatment paradigm for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and barriers to therapeutic efficacy. Front Oncol. 2021; 11:688377. [CrossRef]

- Słodkowski M, Wroński M, Karkocha D, Kraj L, Śmigielska K, Jachnis A. Current approaches for the curative-intent surgical treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023; 15:2584. [CrossRef]

- Orlandi E, Citterio C, Anselmi E, Cavanna L, Vecchia S. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel as first line treatment in pancreatic cancer: a real-world comparison. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2024; 4:165-171. [CrossRef]

- Chouari T, La Costa FS, Merali N, Jessel MD, Sivakumar S, Annels N, Frampton AE. Advances in immunotherapeutics in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023; 15:4265. [CrossRef]

- Sahin U, Koslowski M, Dhaene K, Usener D, Brandenburg G, Seitz G, Huber C, Türeci O. Claudin-18 splice variant 2 is a pan-cancer target suitable for therapeutic antibody development. Clin Cancer Res. 2008; 14:7624-7634. [CrossRef]

- Wöll S, Schlitter AM, Dhaene K, Roller M, Esposito I, Sahin U, Türeci Ö. Claudin 18.2 is a target for IMAB362 antibody in pancreatic neoplasms. Int J Cancer. 2014; 134:731-739. [CrossRef]

- Park S, Shin K, Kim IH, Hong T, Kim Y, Suh J, Lee M. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients with claudin-18 overexpression. J Clin Med. 2023; 12:5394. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang CS, Dong XY, Hu Y, Duan BJ, Bai J, Wu YY, Fan L, Liao XH, Kang Y, Zhang P, Li MY, Xu J, Mao ZJ, Liu HT, Zhang XL, Tian LF, Li EX. Claudin 18.2 is a potential therapeutic target for zolbetuximab in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022; 14:1252-1264. [CrossRef]

- Kayikcioglu E, Yüceer RO. The role of claudin 18.2 and HER-2 in pancreatic cancer outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102: e32882. [CrossRef]

- Türeci Ӧ, Mitnacht-Kraus R, Wöll S, Yamada T, Sahin U. Characterization of zolbetuximab in pancreatic cancer models. Oncoimmunology. 2018;8:e1523096. [CrossRef]

- Zarei M, Lal S, Parker SJ, Nevler A, Vaziri-Gohar A, Dukleska K, Mambelli-Lisboa NC, Moffat C, Blanco FF, Chand SN, Jimbo M, Cozzitorto JA, Jiang W, Yeo CJ, Londin ER, Seifert EL, Metallo CM, Brody JR, Winter JM. Posttranscriptional the upregulation of IDH1 by HuR establishes a powerful survival phenotype in pancreaticcancer cells. Cancer Res. 2017; 77:4460-4471. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Xu W, Li M, Yang Y, Sun D, Chen L, Li H, Chen L. The regulatory mechanisms and inhibitors of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 in cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023; 13:1438-1466. [CrossRef]

- Golub D, Iyengar N, Dogra S, Wong T, Bready D, Tang K, Modrek AS, Placantonakis DG. Mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase inhibitors as targeted cancer therapeutics. Front Oncol. 2019; 9:417. [CrossRef]

- Xiang ZJ, Hu T, Wang Y, Wang H, Xu L, Cui N. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was associated with prognosis and immunomodulatory in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Biosci Rep. 2020;40: BSR20201190. [CrossRef]

- Pointer DT Jr, Roife D, Powers BD, Murimwa G, Elessawy S, Thompson ZJ, Schell MJ, Hodul PJ, Pimiento JM, Fleming JB, Malafa MP. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, not platelet to lymphocyte or lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, is predictive of patient survival after resection of early-stage pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020; 20:750. [CrossRef]

- Iwai N, Okuda T, Sakagami J, Harada T, Ohara T, Taniguchi M, Sakai H, Oka K, Hara T, Tsuji T, Komaki T, Kagawa K, Yasuda H, Naito Y, Itoh Y. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2020; 10:18758. [CrossRef]

- Jia K, Chen Y, Sun Y, Hu Y, Jiao L, Ma J, Yuan J, Qi C, Li Y, Gong J, Gao J, Zhang X, Li J, Zhang C, Shen L. Multiplex immunohistochemistry defines the tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapeutic outcome in CLDN18.2-positive gastriccancer. BMC Med. 2022; 20:223. [CrossRef]

- Camelo-Piragua S, Jansen M, Ganguly A, Kim JC, Louis DN, Nutt CL. Mutant IDH1-Specific immunohistochemistry distinguishes diffuse astrocytoma from astrocytosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010; 119:509-511. [CrossRef]

- Delgado A, Guddati AK. Clinical endpoints in oncology - a primer. Am J Cancer Res.2021; 11:1121-1131.

- Dang L, Yen K, Attar EC. IDH mutations in cancer and progress toward development of targeted therapeutics. Ann Oncol. 2016; 27:599-608. [CrossRef]

- Zarei M, Hajihassani O, Hue JJ, Graor HJ, Rothermel LD, Winter JM. Targeting wild-type IDH1 enhances chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Mar 29:2023.03.29.534596. [CrossRef]

- Luo X, Yu B, Jiang N, Du Q, Ye X, Li H, Wang WQ, Zhai Q. Chemotherapy-induced reduction of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with better survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer Control. 2020; 27:1073274820977135. [CrossRef]

- Vunnam N, Young MC, Liao EE, Lo CH, Huber E, Been M, Thomas DD, Sachs JN. Nimesulide, a COX-2 inhibitor, sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by promoting DR5 clustering. Cancer Biol Ther. 2023; 24:2176692. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen SR, Strøbech JE, Horton ER, Jackstadt R, Laitala A, Bravo MC, Maltese G, Jensen ARD, Reuten R, Rafaeva M, Karim SA, Hwang CI, Arnes L, Tuveson DA, Sansom OJ, Morton JP, Erler JT. Suppression of tumor-associated neutrophils by lorlatinib attenuates pancreatic cancer growth and improves treatment with immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Commun. 2021; 12:3414. [CrossRef]

- Li HB, Yang ZH, Guo QQ. Immune checkpoint inhibition for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: limitations and prospects: a systematic review. Cell Commun Signal. 2021; 19:117. [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) |

| Age, years | |

| <60 | 23 (31.9) |

| >60 | 49 (68.1) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 33 (45.8) |

| Male | 39 (54.2) |

| Smoking history | |

| Negative | 33 (45.8) |

| Positive | 39 (54.2) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Absent | 39 (54.2) |

| Present | 33 (45.8) |

| Presence of weight loss | |

| No | 28 (38.9) |

| Yes | 44 (61.1) |

| Presence of jaundice at initial presentation | |

| No | 30 (41.7) |

| Yes | 42 (58.3) |

| History of diabetes | |

| Negative | 28 (38.9) |

| Positive | 44 (61.1) |

| Presence of metastasis at initial presentation | |

| No | 158 (57.7) |

| Yes | 104 (42.3) |

| Primary tumor localization | |

| Head | 33 (45.8) |

| Body | 31 (43.1) |

| Tail | 8 (11.1) |

| Presence of visceral metastasis at initial presentation | |

| No | 88 (64.7) |

| Yes | 47 (35.3) |

| First-line chemotherapy regimen | |

| FOLFIRINOX | 43 (59.7) |

| Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel | 29 (40.3) |

| Variable | Median PFS (months) | Univariable P | Multivariable-adjusted P | HR (95% CI) |

| Age, years | ||||

| <60 | 8.6 | 0.42 | ||

| >60 | 7.1 | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 8.6 | 0.26 | ||

| Male | 5.9 | |||

| Smoking history | ||||

| Negative | 9.6 | 0.20 | ||

| Positive | NR | |||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Absent | 9.1 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 2.5 (0.19−31.9) |

| Present | 5.6 | |||

| Presence of weight loss | ||||

| No | 10.4 | 0.91 | ||

| Yes | 9.6 | |||

| Presence of jaundice at initial presentation | ||||

| No | 10.4 | 0.84 | ||

| Yes | 5.9 | |||

| History of diabetes | ||||

| Negative | 10.4 | 0.74 | ||

| Positive | 12.8 | |||

| Presence of metastasis at initial presentation | ||||

| No | 19.2 | 0.36 | ||

| Yes | 8.6 | |||

| Primary tumor localization | ||||

| Head | 7.2 | 0.73 | ||

| Body | 7.1 | |||

| Tail | 7.1 | |||

| Presence of visceral metastasis at initial presentation | ||||

| No | 9.6 | 0.33 | ||

| Yes | 5.9 | |||

| First-line chemotherapy regimen | ||||

| FOLFIRINOX | 7.2 | 0.34 | ||

| Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel | 7.1 | |||

| CLDN18.2 expression | ||||

| Negative | 6.2 | 0.29 | ||

| Positive | 13.9 | |||

| IDH1 expression | ||||

| Negative | 7.1 | 0.033 | 0.98 | 0.10 (0.05−2.12) |

| Positive | 3.7 | |||

| NLR | ||||

| ≤ 3.22 | 18.9 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 1.61 (0.77−3.39) |

| > 3.22 | 6.2 | |||

| Variable | Median OS (months) | Univariable P | Multivariable-adjusted P | HR (95% CI) |

| Age, years | ||||

| <60 | 10.5 | 0.15 | ||

| >60 | 9.4 | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 10.1 | 0.26 | ||

| Male | 9.7 | |||

| Smoking history | ||||

| Negative | 10.6 | 0.35 | ||

| Positive | 12.3 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Absent | 15.7 | 0.67 | ||

| Present | 10.7 | |||

| Presence of weight loss | ||||

| No | 10.4 | 0.91 | ||

| Yes | 9.6 | |||

| Presence of jaundice at initial presentation | ||||

| No | 14.2 | 0.57 | ||

| Yes | 10.3 | |||

| History of diabetes | ||||

| Negative | 14.8 | 0.28 | ||

| Positive | 13.9 | |||

| Presence of metastasis at initial presentation | ||||

| No | 20.3 | 0.40 | ||

| Yes | 9.9 | |||

| Primary tumor localization | ||||

| Head | 9.8 | 0.33 | ||

| Body | 9.4 | |||

| Tail | 13.5 | |||

| Presence of visceral metastasis at initial presentation | ||||

| No | 11.3 | 0.93 | ||

| Yes | 9.2 | |||

| First-line chemotherapy regimen | ||||

| FOLFIRINOX | 10.1 | 0.16 | ||

| Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel | 9.4 | |||

| CLDN18.2 expression | ||||

| Negative | 9.2 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.38 (0.18−0.81) |

| Positive | 15.2 | |||

| IDH1 expression | ||||

| Negative | 9.8 | 0.011 | 0.039 | 0.68 (0.19−0.72) |

| Positive | 5.3 | |||

| NLR | ||||

| ≤ 3.22 | 12.0 | 0.016 | 0.038 | 1.92 (1.03−3.56) |

| > 3.22 | 9.4 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).