Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods/Approach

Literature Search

Conceptual Framework Development

- Inflammasome activation (NLRP3, IL-1β, IL-18)

- Disruption of protein prenylation (Ras-related C3 Botulinum Toxin Substrate [Rac1], geranylgeranylation)

- Insulin resistance acting as an inflammation amplifier

- Shifts in thymus-derived lymphocyte (T-cell) balance (T Helper 17 cell subtype [Th17] versus regulatory T-cells [Tregs])

- Immune priming driven by Lp(a) and oxidized phospholipids

3. Mechanistic Framework

Clinical Problem and Paradoxes

The Residual Risk Paradox

- Inflammation drives residual risk (CANTOS, LoDoCo2) [5,6]

- Statins reduce MACE by ~25% per mmol/L [LDL-C] lowering but leave ~75% of events even with [LDL-C] <1.4 mmol/L [3,4] a gap better predicted by Apolipoprotein (Apo)B [22,23]

- Early epidemiological work, in particular the Framingham Study and its stress-defense analyses, established the baseline event rates and risk factors still used to benchmark modern therapies [24]

- A large meta-analysis confirms persistent risk and treatment heterogeneity [3] and statin-treated patients with low [LDL-C] still face higher event rates than untreated peers with similar concentrations [25]

The Statin Pleiotropy Paradox

The Temporal Paradox

The Enhanced Mechanistic Model

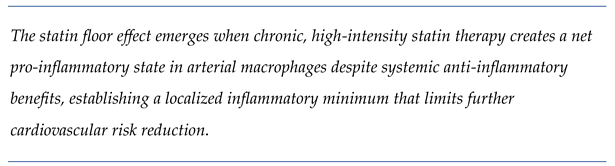

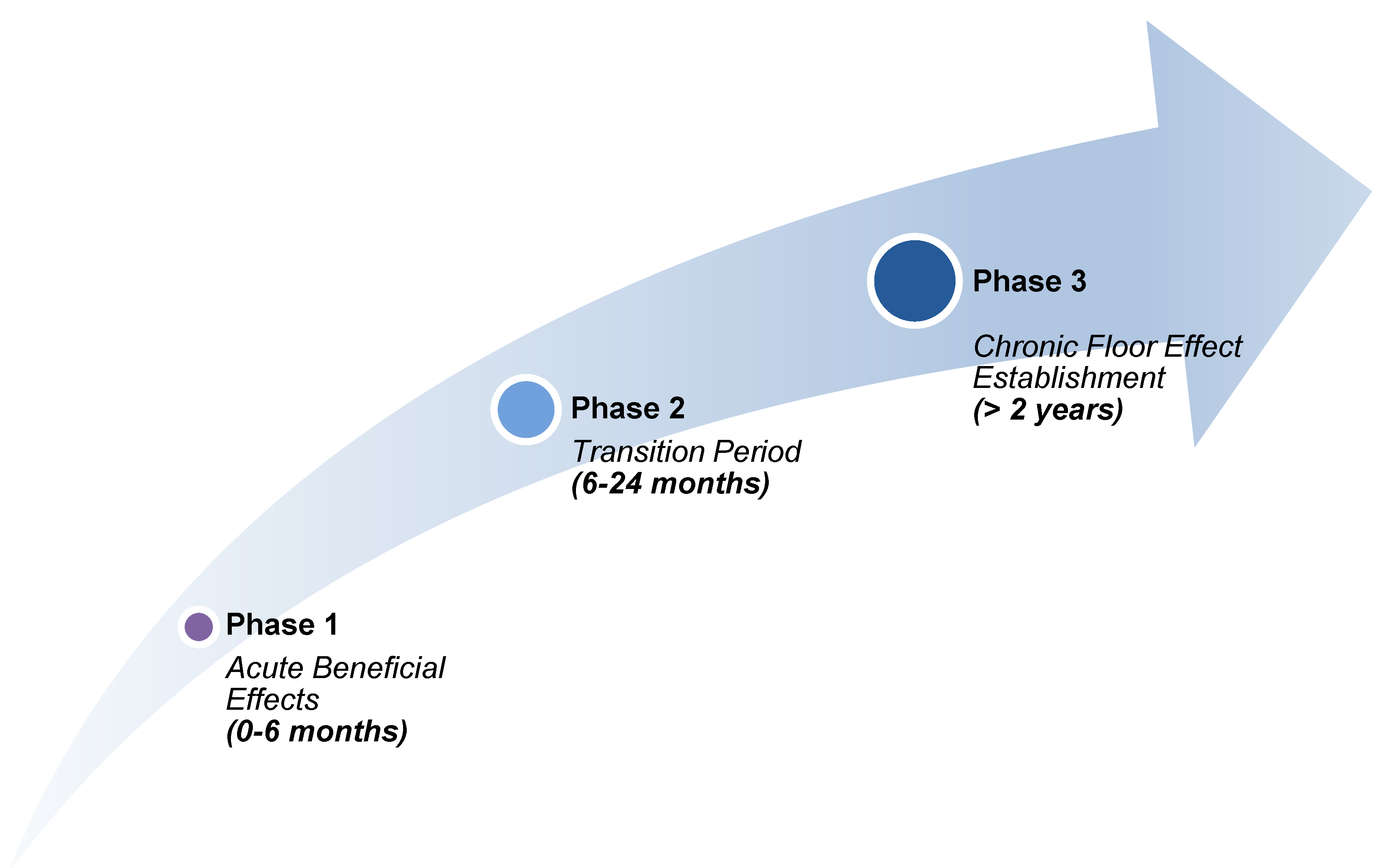

Core Framework Statement

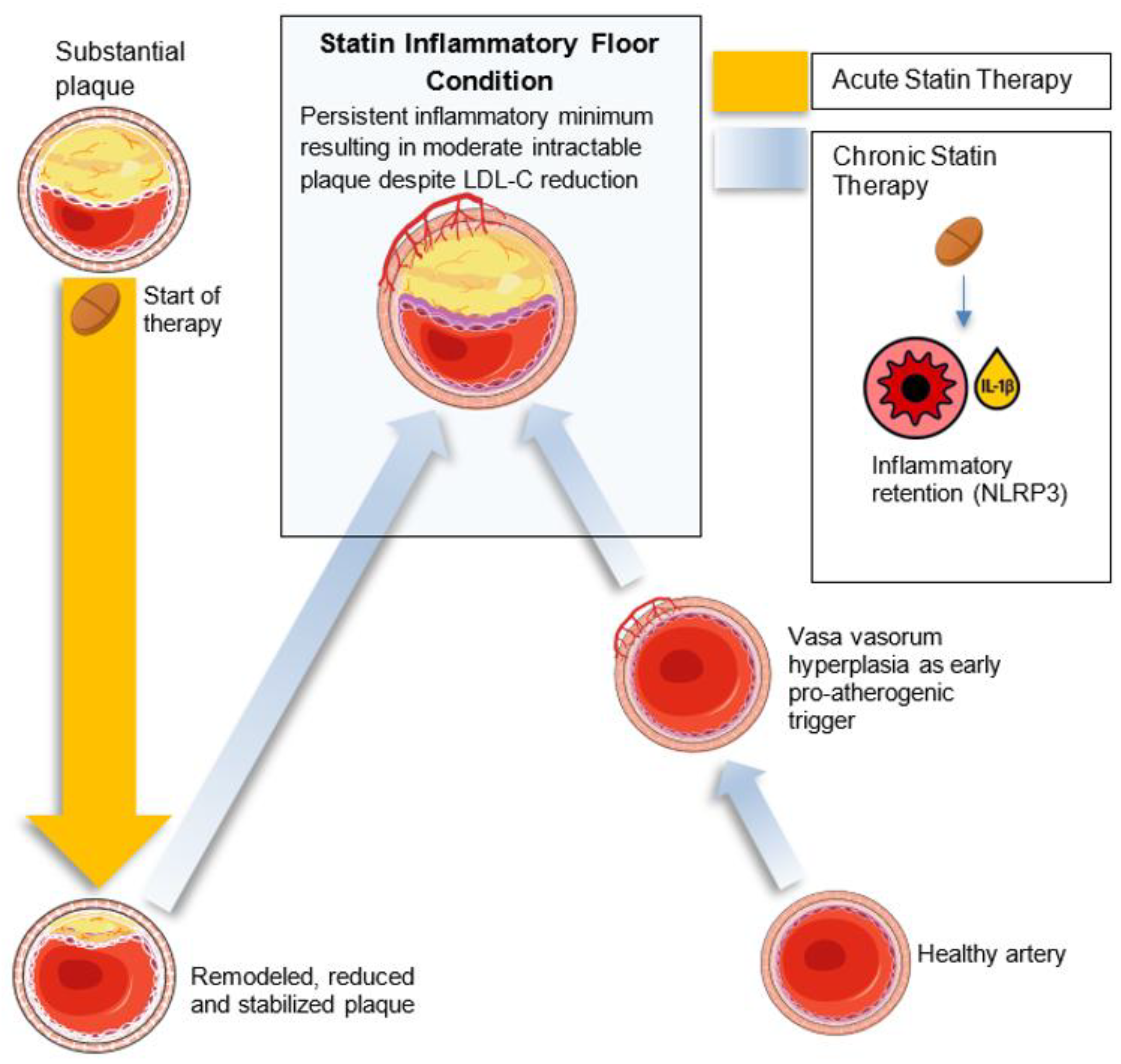

Temporal Stratification Model

- Phase 1 (0–6 months): rapid [LDL-C] lowering with predominant anti-inflammatory benefit

- Phase 2 (6–24 months): competing beneficial and detrimental effects as mevalonate pathway disruption accumulates

- Phase 3 (>24 months): a persistent inflammatory floor limits further MACE reduction despite maintained [LDL-C] suppression

Primary Pathway: Dose-Dependent NLRP3 Activation

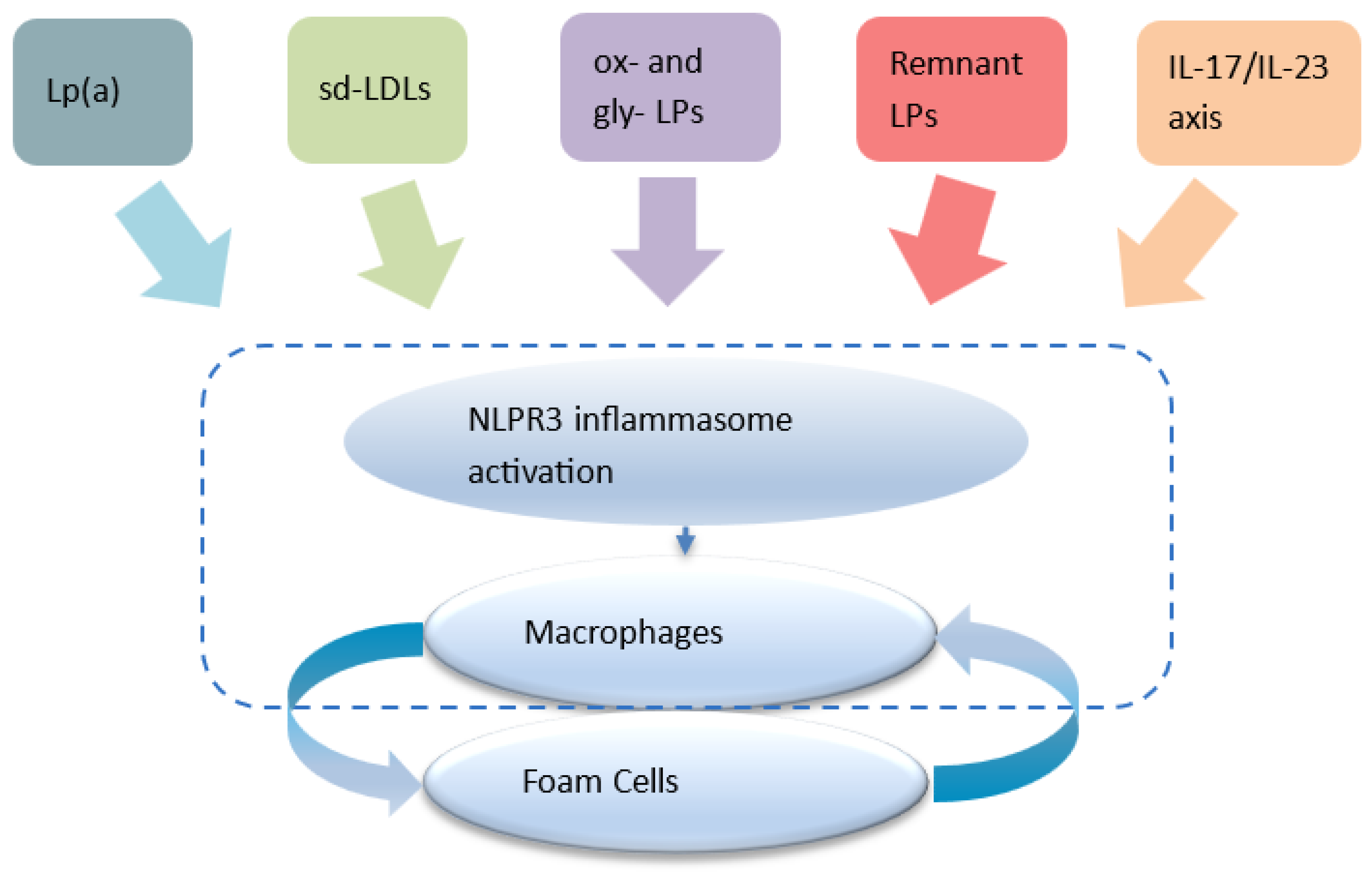

- NLRP3 inflammasome activation in arterial macrophages arises from convergent lipid-sensing pathways, Rac1 dysregulation, impaired protein prenylation, and oxidized lipids, forming the core of the inflammatory floor effect [49,50]

- Statins inhibit the mevalonate pathway, reducing geranylgeranylation and impairing Rac1 regulation to augment NLRP3 activity 2 [49,50], with mathematical and spectroscopic modeling confirming dose-dependent stress signatures consistent with inflammasome priming [28]. Moreover, statins modestly elevate Lp(a) levels [51], whose oxidized phospholipid cargo directly triggers NLRP3 activation, thereby offering a unified upstream pathway linking NLRP3 activation with insulin resistance and reinforcing the inflammatory floor despite optimal LDL-C levels 3 [45,46].

- Statin-mediated menaquinone-4 (MK-4) depletion may impair inflammasome regulation via reduced SXR activation (vide infra: Section 4 - Therapeutic Potential subsection).

- Macrophages retain IL-1β and IL-18 secretion despite expressing alternatively activated (pro-resolution) macrophage (M2) markers [52,53], driving LDLR-mediated lipid uptake [52], foam cell persistence [50,54] and cytokine-reinforced plaque instability [55]

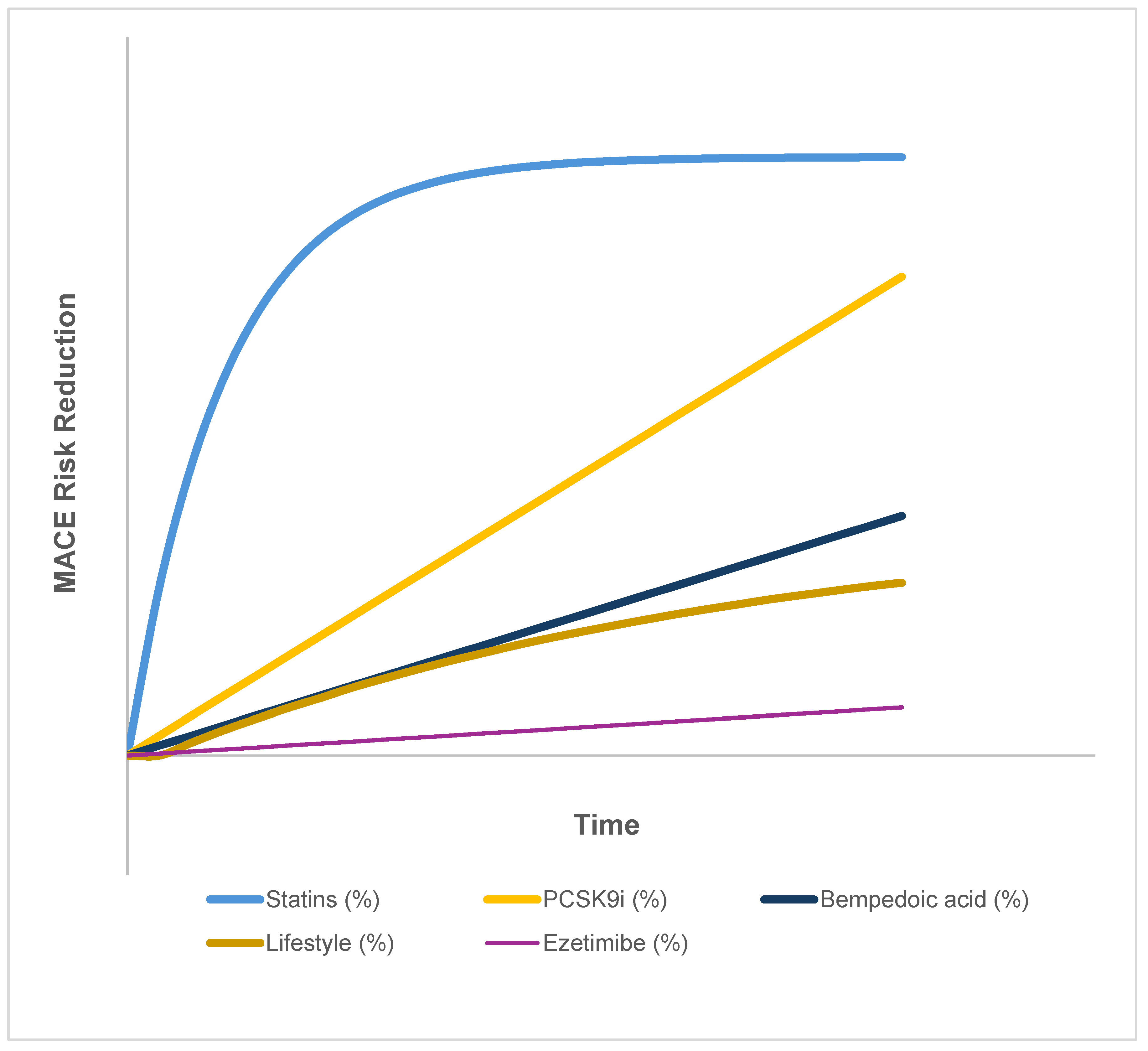

- Statins also inhibit GTPase prenylation, suppressing Th17 differentiation [56,57] and expanding Tregs [58,59], though these adaptive immune effects vary among individuals [60] and sustain a pro-inflammatory milieu 4. In contrast, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors (FOURIER) and bempedoic acid (CLEAR Outcomes) show continuously diverging event-reduction curves at 2–3 years without the early plateau seen in statin trials [31,61].

Secondary Pathways

- Statin-induced NLRP3 activation → systemic IL-1β elevation

- IL-1β → worsens insulin sensitivity [69]

- Insulin resistance → further chronic inflammation [70]

- 10–15% increased diabetes risk with statin use 5 [27]

- Human and translational studies show statins can aggravate insulin resistance by reducing circulating GLP-1 via a Clostridium–Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)–bile-acid axis; UDCA supplementation restores GLP-1 and improves glycemia [13]

- Red blood cell (RBC)-derived extracellular vesicles in diabetes: Glycated or fragile RBCs release vesicles enriched in arginase-1, which are taken up by endothelial cells to suppress nitric oxide bioavailability and increase reactive oxygen species, driving endothelial dysfunction and inflammation [71]. In the statin context, where diabetes risk is elevated, such RBC-EV–mediated insults may synergize with impaired metabolic resilience to sustain a permissive vascular milieu for lipid retention and inflammasome activation.

- Insulin resistance enhances NLRP3 priming in macrophages 6 [72]

- Metabolic dysfunction amplifies pro-inflammatory cytokine production [73]

- A self-reinforcing cycle maintains the inflammatory floor [73]

Tissue-Specific Context Dependency

- Hepatocytes: Retain beneficial responses and systemic anti-inflammatory effects [72]

- Arterial Macrophages: Susceptible to prenylation disruption, driving persistent inflammasome activation [49]

- Systemic Immune Cells: Mixed responses influenced by genetic predisposition [74]

Parallel Amplification Pathways

Supporting EvidenceMolecular Mechanisms

- Histological mapping of human plaques confirms the persistence of macrophage-driven inflammation in morphologically stable lesions, reinforcing the concept of a durable, non-resolving inflammatory floor even in the absence of systemic flare markers [82].

- Statins increase IL-1β in macrophages in a dose-sensitive, NLRP3-dependent manner [11,27]

- Disruption of Rac1 and protein prenylation alters macrophage phenotype [49]

- M2 macrophages retain pro-inflammatory characteristics under chronic statin exposure [83]

- Foam cells are maintained due to impaired mobility and IL-1β-mediated LDL uptake [54]

- Geranylgeraniol supplementation mitigates statin-induced inflammasome activation [84]

Clinical Correlates

- Dose-dependent diabetes risk with statin therapy; mechanistic human evidence indicates statin-associated GLP-1 reduction contributes to this phenotype [13]

- Residual risk concentrated in secondary prevention populations [24,85]

- Colchicine reduces CV events by ~34% in statin-treated patients [6]

- Early vs late statin initiation shows different inflammatory profiles [32]

- Although statin therapy often reduces [CRP] to within the clinically acceptable range as measured by hs-CRP assays [86], concentrations may still exceed thresholds associated with arterial inflammation and cardiovascular risk. In other words, [CRP] falls, but not necessarily far enough to extinguish the inflammatory floor that sustains residual events. Meta-analytic evidence confirms that, even with optimal [LDL-C] reduction, many patients continue to experience cardiovascular events, often in association with persistent, albeit subclinical, elevations in inflammatory markers [23,32].

- Arterial vs Systemic Inflammation Decoupling: reflects systemic IL-6 levels, while NLRP3 activation is local and may be insulin resistance-amplified [26]. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging shows arterial vs systemic dissociation [86].

- PCSK9 inhibitors show diminishing returns in heavily statin-treated populations [87]

Biomarker Evolution Patterns

- Initial [CRP] reduction followed by plateau or slight increase, while IL-18 levels remain elevated and predictive of cardiovascular death in both stable and unstable angina [33]

- Persistent elevation of IL-18 in high-dose statin users [88]

- Divergence between systemic and arterial inflammatory markers [86]

- Elevated IL-1β and IL-18 remain predictive of adverse cardiovascular outcomes despite LDL-C lowering, consistent with persistent inflammasome activity [63]

4. Therapeutic Implications

Refined Biomarker Strategy and Monitoring

Dynamic Biomarker Panel

Functional Assays

- Ex vivo macrophage polarisation capacity

- LDL uptake studies

- Inflammasome activation assays

Precision Monitoring Strategy

- Genetic screening: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), NLRP3, IL-1β, Rac1 variants

- Baseline phenotyping: Metabolic and inflammatory profile assessment

- Longitudinal tracking: Biomarker evolution over therapy duration

- Imaging correlation: Arterial inflammation persists despite systemic reduction 7 [90]; advanced PET tracers such as ¹⁸F-NaF (detecting microcalcification) and ⁶⁸Ga-DOTATATE or ⁶⁸Ga-PentixaFor (targeting activated macrophages or C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) expression) provide tissue-specific insight into persistent plaque activity, helping distinguish inflammatory floor regions from systemic responses [86,91]

Testable Predictions

Clinical Predictions

- On maximal-dose statin therapy, IL-1β/IL-18 will fall initially in step with [LDL-C], but after 12–24 months will plateau or rebound, so that at long-term steady-state (≥2 years) patients have higher IL-1β/IL-18 despite [LDL-C] remaining low

- Carriers of HMGCR or NLRP3 variants show greater susceptibility to the inflammatory floor effect

- Arterial inflammation persists on PET imaging despite systemic normalization

- Statin-induced diabetics show higher arterial inflammatory markers independent of glycemic control

Mechanistic Predictions

- Statin-treated macrophages express M2 markers but retain IL-1β secretion 8

- Geranylgeraniol supplementation suppresses IL-1β without altering [LDL-C]

- Early vs late statin exposure yields distinct epigenetic and inflammatory profiles

- Anti-inflammatory agents benefit genetically susceptible patients more than average

Intervention Predictions

- Early combination therapy prevents inflammatory floor effect establishment

- Metformin co-therapy lowers localized IL-1β levels and diabetes risk

- Biomarker-guided statin dosing improves risk/benefit balance

- Genetic profiling enables earlier combination treatment

- Adjunct UDCA will restore GLP-1 and attenuate elevated blood glucose and insulin-resistance amplification in patients on high-intensity statins [13]

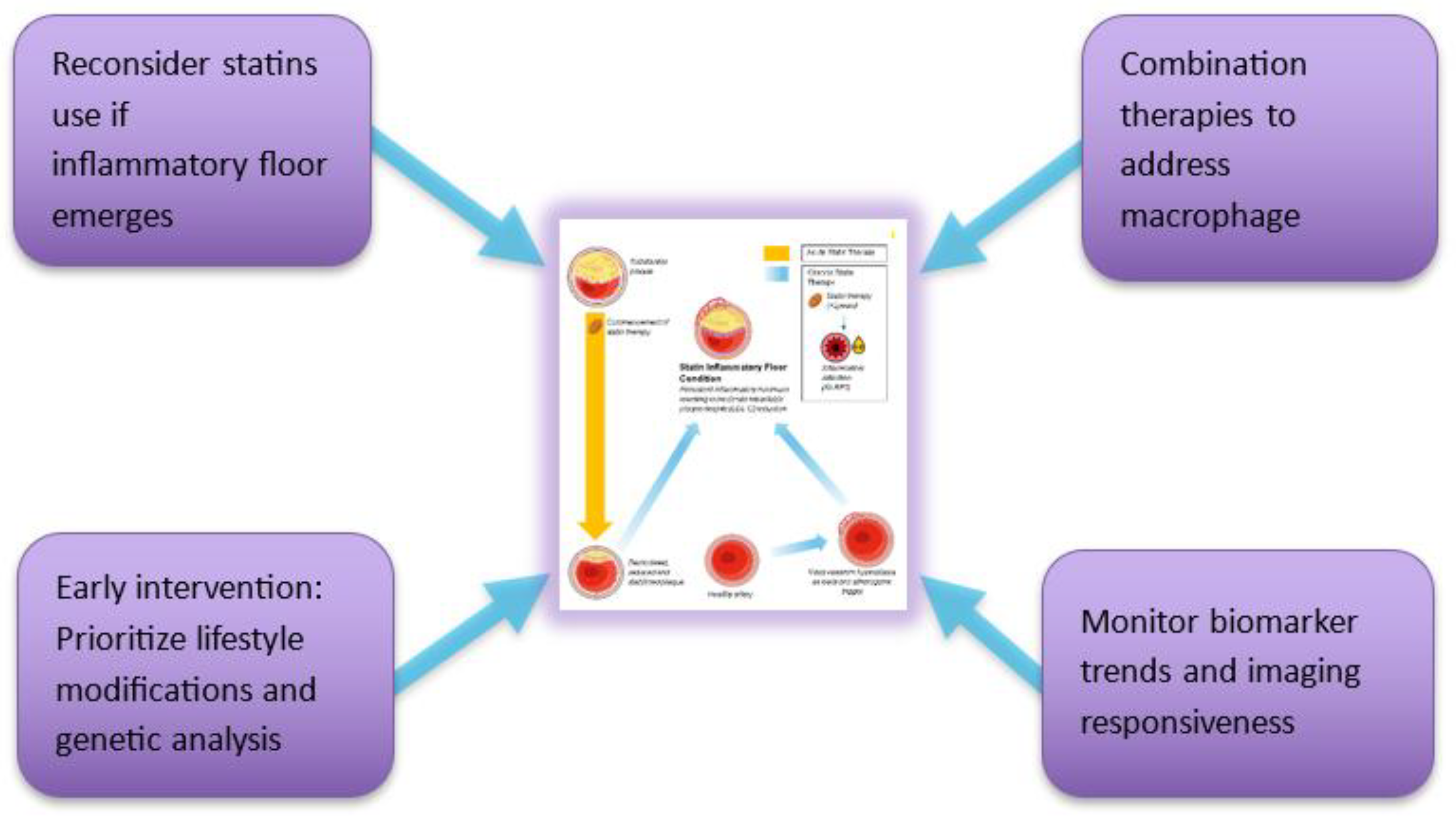

Clinical Implementation Strategy

Risk Stratification Approach

- Aggressive systolic blood pressure control: (120-90 mmHg) and polyphenol-rich diets may blunt mechanical and immunometabolic triggers, reducing NLRP3 activation, improving insulin sensitivity, and lowering endothelial shear stress, to support plaque resolution [92–94]

- Low Risk: Statin monotherapy, routine monitoring

- Moderate Risk: Enhanced biomarker tracking, conditional combination therapy

- High Risk: Immediate combination therapy and intensive monitoring

Precision Medicine Integration

- One off determination of [LP(a)]

- Genetic testing to identify susceptible variants

- Metabolic and inflammatory baseline profiling

- Individualized ApoB, LDL-C, and inflammatory targets

- Dynamic treatment adjustments

- Therapeutic approaches that enhance Treg function or suppress Th17 responses could be beneficial, as suggested by recent insights into T-cell roles in atherosclerosis [95,96]

Therapeutic Sequencing

- Pre-Phase (Structural Priming and Vascular Neogenesis)In the SFE framework, adventitial vasa vasorum hyperplasia and diffuse intimal hyperplasia prime arteries for lipid retention and inflammation, Yang et al. showed in rabbits that adventitial vasa vasorum proliferation precedes intima–media thickening and predicts plaque development [97]. Following this, diffuse intimal hyperplasia (DIH), as described by Subbotin, may further predispose to lipid retention by increasing oxygen diffusion distance and creating localized hypoxia. This facilitates smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation and extracellular matrix accumulation [98]. Together, adventitial vasa vasorum and DIH can create a permissive terrain upon which lipids accumulate and immune processes initiate. Identifying and interrupting these early, pre-lipid stages may offer an opportunity for pre-emptive vascular therapy in at-risk individuals.

- Phase 1 (0–6 months): Statin therapy initiation

- Phase 2 (6–24 months): Monitor for inflammatory floor effect

- Phase 3 (>2 years): Maintain combination therapy for at-risk individuals

Research Priorities and Study Design

Longitudinal Mechanistic Studies

- 5-year biomarker tracking studies

- Stratified cohorts by genetic risk

- Human arterial tissue sampling

- PET imaging to correlate markers with inflammation

Intervention Trials

- Early statin + anti-inflammatory randomized controlled trials

- Biomarker-guided versus standard care dosing

- Metformin combination trials

- Personalized therapy based on genomic risk

Mechanistic Validation

- Murine models to examine NLRP3–foam cell trajectory

- Ex vivo validation of macrophage phenotypes

- Prospective validation of biomarker panels

Modeling Research

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Immediate Clinical Applications

- Biomarker screening for residual inflammatory risk

- Early combination therapy consideration

- Avoid unnecessary statin up-titration in the inflammatory floor effect phenotype

- Better risk communication strategies

Long-Term Paradigm Shifts

- Broaden to immunometabolic cardiology

- Genetically informed prevention models

- Simultaneous targeting of lipid, metabolic, and immune pathways

- Integrated biomarker and imaging-based care models

- While NLRP3 remains the most extensively characterized inflammasome in atherosclerosis, other complexes such as absent in melanoma 2 and NOD-like receptor family CARD domain containing 4 may also contribute to vascular inflammation [53]. Recognizing the pivotal role of adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis, future paradigms may shift towards immunomodulatory therapies [50,101]. Their integration into the SFE framework awaits further mechanistic clarity.

Therapeutic Innovation Opportunities

- NLRP3-specific anti-inflammatory therapies

- Fixed-dose statin + anti-inflammatory combinations

- Genetic testing panels for cardiovascular risk

- Point-of-care inflammatory biomarker devices

- Adventitial vasa vasorum modulation: Early detection and targeting of proliferation, via ultrasound or contrast-enhanced imaging, may offer a window to prevent downstream plaque formation before intimal thickening or immune infiltration

- Structural-stage targeting: Therapeutic modulation of DIH and matrix remodeling, especially in metabolically susceptible individuals, may delay or prevent the creation of lipid-retentive terrain. This approach expands risk-reduction efforts upstream of lipid-lowering or anti-inflammatory therapies.

- Targeted modulation of Lp(a)-associated risk - is now achievable through gene-silencing therapies such as pelacarsen (antisense oligonucleotide), olpasiran and zerlasiran (small interfering RNAs, siRNAs), which have been shown to reduce [Lp(a)] by up to 90% in clinical trials. These agents provide precision strategies for genetically mediated [Lp(a)] elevation.

- Statins can variably raise [Lp(a)] in some individuals, though this effect is not universal and may not always be clinically significant

- Novel agents like muvalaplin (an oral inhibitor of Apo(a)-ApoB binding) offer non-injectable alternatives

- While colchicine does not reduce [Lp(a)], it may blunt downstream inflammation triggered by Lp(a)-bound OxPLs, offering potential therapeutic synergy in high-risk inflammatory phenotypes

Why This Framework Matters

Clinical Relevance

- Explains paradoxes in residual cardiovascular risk

- Enables identification of patients needing intensified therapy

- Enhances clinical efficiency via better risk stratification

- Supports enhanced cardiovascular disease risk reduction

Scientific Impact

- Postulates a unifying mechanistic model

- Encourages precision research designs

- Enhances biomarker development

- Sets the stage for future immunometabolic therapies

Therapeutic Potential

- RNA-silencing approaches: Recent preclinical studies demonstrate that hepatocyte-targeted siRNA and GalNAc-conjugated oligonucleotides against Farnesyl-diphosphate Farnesyltransferase 1 (FDFT1) achieve >70% knockdown of squalene synthase mRNA, reduce plasma [LDL-C] by 30–40%, and attenuate atherosclerotic lesion development in animal models. Early human Phase I data with GalNAc–FDFT1 siRNA suggest durable [LDL-C] lowering with quarterly subcutaneous dosing and a favorable safety profile [102,103].

- Combination with Statins: Preclinical co-administration of low-dose statin plus FDFT1 siRNA yielded additive [LDL-C] lowering (~60-70% total) and greater atherosclerotic plaque regression than either alone, supporting a dual-mechanism strategy to overcome the inflammation floor of statin monotherapy

- Targeting the rescue of the impaired synthesis of MK-4: a form of vitamin K₂ that modulates inflammatory resolution and mitochondrial homeostasis - although direct clinical evidence is lacking, murine studies show that statins can suppress MK-4 formation in extrahepatic tissues. MK-4 deficiency impairs activation of matrix Gla protein (MGP), promoting microcalcification, and may enhance NLRP3 inflammasome activity by removing antioxidant and anti-NF-κB restraints [104]. Observational human data further link low circulating [MK-4] with greater coronary calcification, suggesting a plausible translational mechanism [105]. Thus, MK-4 depletion may represent a second direct molecular axis, alongside geranylgeranyl gyrophosphate / Rac1 disruption, through which statins promote a persistent inflammatory floor within atherosclerotic lesions. This again illustrates the paradoxical effect of statins in that they also enhance plaque stabilization through calcification.

- FDFT1 silencing: limits squalene-derived isoprenoids, reducing macrophage endoplasmic reticulum stress and NLRP3 activation, offering a novel strategy to target the inflammatory floor

- IL-10: may drive post-MI plaque regression and myocardial remodeling by enhancing M2 polarization, suppressing MMP-9, and boosting mitochondrial function, but its efficacy falls off above ~1 µg/mL, highlighting the need for controlled delivery [106]

- Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)-driven plaque reduction: a meta-analysis of 23 intravascular ultrasound trials showed each 1% decrease in percent atheroma volume was linked to a 19% lowering of MACE [107], and in statin-treated coronary artery disease patients, a higher ratio of EPA-derived mediators (18-hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid + resolvin E1) to leukotriene B₄ strongly predicted actual plaque regression [108]

- New gene-editing approaches: such as VERVE-102, which offers durable, possibly lifelong PCSK9 silencing in humans, may further decouple [LDL-C] lowering from the immunometabolic disruptions observed with statins and thus represent an ideal platform for combination therapy targeting inflammatory floor mechanisms [109]

- Unique protein dysregulations: opportunities lie in their discovery by the application of proteomics mass spectrometry, paving the way to new therapies and mechanistic insights. Early spatially resolved proteomic studies of human plaques [110] (preprint) suggest that arterial PCSK9 secretion, ECM remodeling, and region-specific inflammatory pathways may be particularly tractable targets, underscoring the value of local proteomic mapping for future therapy development.

5. Conclusions

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Cannon Christopher P, Braunwald E, McCabe Carolyn H, Rader Daniel J, Rouleau Jean L, Belder R, et al. Intensive versus Moderate Lipid Lowering with Statins after Acute Coronary Syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(15):1495–504. [CrossRef]

- Waters DD, Guyton JR, Herrington DM, McGowan MP, Wenger NK, Shear C. Treating to New Targets (TNT) Study: does lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels below currently recommended guidelines yield incremental clinical benefit? Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(2):154–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists, C. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. The Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670–81. [CrossRef]

- Navarese EP, Robinson JG, Kowalewski M, Kolodziejczak M, Andreotti F, Bliden K, et al. Association Between Baseline LDL-C Level and Total and Cardiovascular Mortality After LDL-C Lowering: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Jama. 2018;319(15):1566–79. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:1119–31. [CrossRef]

- Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383:1838–47. [CrossRef]

- Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464(7293):1357–61. [CrossRef]

- Shankman LS, Gomez D, Cherepanova OA, Salmon M, Alencar GF, Haskins RM, et al. KLF4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nature Medicine. 2015;21(6):628–37. [CrossRef]

- Allahverdian S, Chehroudi AC, McManus BM, Abraham T, Francis GA. Contribution of Intimal Smooth Muscle Cells to Cholesterol Accumulation and Macrophage-Like Cells in Human Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2014;129(15):1551–9. [CrossRef]

- Henriksbo BD, Tamrakar AK, Phulka JS, Barra NG, Schertzer JD. Statins activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and impair insulin signaling via p38 and mTOR. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2020;319(1):E110–E6. [CrossRef]

- Koushki K, Shahbaz SK, Mashayekhi K, Sadeghi M, Zayeri ZD, Taba MY, et al. Anti-inflammatory Action of Statins in Cardiovascular Disease: the Role of Inflammasome and Toll-Like Receptor Pathways. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;60(2):175–99. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sirtori CR, Watts GF, Corsini A, Ruscica M. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of statin pleiotropic effects: the unresolved puzzle. Archives of Toxicology. 2023;97(10):2861–87. [CrossRef]

- She J, Tuerhongjiang G, Guo M, Liu J, Hao X, Guo L, et al. Statins aggravate insulin resistance through reduced blood glucagon-like peptide-1 levels in a microbiota-dependent manner. Cell Metabolism. 2024;36(2):408–21.e5. [CrossRef]

- Chiu JJ, Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiological Reviews. 2011;91(1):327–87. [CrossRef]

- Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1999;282(21):2035–42. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Li C, Xu W. Shear stress activates NLRP3 inflammasome to promote endothelial inflammation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2020;235(1):491–500. [CrossRef]

- Ichihara A, Hayashi M, Koura Y, Tada Y, Kaneshiro Y, Saruta T. Long-term effects of statins on arterial pressure and stiffness of hypertensives. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2005;19(2):103–9. [CrossRef]

- Liao JK, Seto M, Noma K. Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitors. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2007;50(1). [CrossRef]

- Liao JK, Laufs U. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:89–118. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gierig M, Tragoudas A, Haverich A, Wriggers P. Mechano-chemo-biological model of atherosclerosis formation based on the outside-in theory. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology. 2024;23(2):539–52. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Zhang H, Hou Q, Zhang Y, Qiao A. Multiscale Modeling of Vascular Remodeling Induced by Wall Shear Stress. Front Physiol. 2021;12:808999. Epub 20220127. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sehayek D, Cole J, Björnson E, Wilkins JT, Mortensen MB, Dufresne L, et al. ApoB, LDL-C and non-HDL-C as Markers of Cardiovascular Risk. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, MB. ApoB triumphs once more over LDL-C and non-HDL-C in risk prediction: ready for guidelines? European Heart Journal. 2024;45(27):2419–21. [CrossRef]

- Abohelwa M, Kopel J, Shurmur S, Ansari MM, Awasthi Y, Awasthi S. The Framingham Study on Cardiovascular Disease Risk and Stress-Defenses: A Historical Review. Journal of Vascular Diseases [Internet]. 2023; 2(1):[122–64 pp.].

- Sabeel S, Motaung B, Nguyen KA, Ozturk M, Mukasa SL, Wolmarans K, et al. Impact of statins as immune-modulatory agents on inflammatory markers in adults with chronic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2025;20(5):e0323749. [CrossRef]

- Ridker Paul M, Danielson E, Fonseca Francisco AH, Genest J, Gotto Antonio M, Kastelein John JP, et al. Rosuvastatin to Prevent Vascular Events in Men and Women with Elevated C-Reactive Protein. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(21):2195–207. [CrossRef]

- Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735–42. [CrossRef]

- Mylonas E, Mamareli C, Filippakis M, Mamarelis I, Anastassopoulou J, Theophanides T. A Mathematical Model of Statin Anti-Hyperlipidemic Drug Reactivity and Diverse Concentrations of Risk Toxicity. Journal of Clinical Medicine [Internet]. 2025; 14(7).

- Mega JL, Stitziel NO, Smith JG. Genetic risk, coronary heart disease events, and the clinical benefit of statin therapy: an analysis of primary and secondary prevention trials. Lancet. 2015;385:2264–71. [CrossRef]

- Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78. [CrossRef]

- Sabatine Marc S, Giugliano Robert P, Keech Anthony C, Honarpour N, Wiviott Stephen D, Murphy Sabina A, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(18):1713–22. [CrossRef]

- Sposito AC, Carvalho LS, Cintra RM, Araújo AL, Ono AH, Andrade JM, et al. Rebound inflammatory response during the acute phase of myocardial infarction after simvastatin withdrawal. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207(1):191–4. Epub 20090417. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, Rifai N, Rose LM, McCabe CH, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(1):20–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim JY, Choi J, Kim SG, Kim NH. Relative contributions of statin intensity, achieved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, and statin therapy duration to cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: population based cohort study. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2022;21(1):28. [CrossRef]

- Laufs U, La Fata V, Plutzky J, Liao JK. Upregulation of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase by HMG CoA Reductase Inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97(12):1129–35. [CrossRef]

- Feng Q, Jia S, Zhou H, Liu S, Li Y, Ding J, et al. An Atorvastatin/Ferrostatin-1 Codelivered Hybrid Exosome/Liposome System for Combinational Ferroptosis Inhibition, Inflammation Suppression, Efferocytosis Promotion, and Macrophage Reprogramming in Atherosclerosis Treatment. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2025;17(25):36542–56. [CrossRef]

- Tabas I, Seimon T, Timmins J, Li G, Lim W. Macrophage apoptosis in advanced atherosclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):E40–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yurdagul A, Jr. , Doran AC, Cai B, Fredman G, Tabas IA. Mechanisms and Consequences of Defective Efferocytosis in Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:86. Epub 20180108. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Henriksbo BD, Tamrakar AK, Xu J, Duggan BM, Cavallari JF, Phulka J, et al. Statins Promote Interleukin-1β–Dependent Adipocyte Insulin Resistance Through Lower Prenylation, Not Cholesterol. Diabetes. 2019;68(7):1441–8. [CrossRef]

- Gao Q, Jiang Y, Ma T, Zhu F, Gao F, Zhang P, et al. A critical function of Th17 proinflammatory cells in the development of atherosclerotic plaque in mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(10):5820–7. [CrossRef]

- Eid RE, Rao DA, Zhou J. Interleukin-17 and related cytokines induce proinflammatory cytokines and activate human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2009;29:490–7. [CrossRef]

- Hansson GK, Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nature Immunology. 2011;12:204–12. [CrossRef]

- Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2006;6:508–19. [CrossRef]

- Erbel C, Akhavanpoor M, Okuyucu D, Wangler S, Dietz A, Zhao L, et al. IL-17A influences essential functions of the monocyte/macrophage lineage and is involved in advanced murine and human atherosclerosis. J Immunol. 2014;193(9):4344–55. Epub 20140926. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Que X, Hung MY, Yeang C, Gonen A, Prohaska TA, Sun X, et al. Oxidized phospholipids are proinflammatory and proatherogenic in hypercholesterolaemic mice. Nature. 2018;558(7709):301–6. Epub 20180606. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pirro M, Simental-Mendía LE, Bianconi V, Watts GF, Banach M, Sahebkar A. Effect of Statin Therapy on Arterial Wall Inflammation Based on 18F-FDG PET/CT: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventional Studies. J Clin Med. 2019;8(1). Epub 20190118. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsimikas S, Gordts P, Nora C, Yeang C, Witztum JL. Statin therapy increases lipoprotein(a) levels. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(24):2275–84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedding DG, Boyle EC, Demandt JAF, Sluimer JC, Dutzmann J, Haverich A, et al. Vasa Vasorum Angiogenesis: Key Player in the Initiation and Progression of Atherosclerosis and Potential Target for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Front Immunol. 2018;9:706. Epub 20180417. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Healy AM, Terkeltaub RA, Moore KJ, Yvan-Charvet L. Statins disrupt macrophage Rac1 regulation leading to increased calcification in atherosclerotic plaques. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2020;40(3):714–26. [CrossRef]

- Grebe A, Hoss F, Latz E. NLRP3 Inflammasome and the IL-1 Pathway in Atherosclerosis. Circulation Research. 2018;122(12):1722–40. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Fazio S, Ferdinand KC. Lipoprotein(a): novel target and emerging biomarker for cardiovascular risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;69:692–711. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Qin Y, Wan X, Liu H, Lv C, Ruan W, et al. Rosuvastatin exerts anti-atherosclerotic effects by improving macrophage-related foam cell formation and polarization conversion via mediating autophagic activities. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2021;19(1):62. [CrossRef]

- Sharma D, Kanneganti TD. The cell biology of inflammasomes: Mechanisms of inflammasome activation and regulation. J Cell Biol. 2016;213(6):617–29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peled M, Fisher EA. Dynamic aspects of macrophage polarization during atherosclerosis progression and regression. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5:579. [CrossRef]

- Williams JW, Huang LH, Randolph GJ. Cytokine circuits in cardiovascular disease. Immunity. 2019;50(4):941–54. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS. Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(5):358–70. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dehnavi S, Sohrabi N, Sadeghi M, Lansberg P, Banach M, Al-Rasadi K, et al. Statins and autoimmunity: State-of-the-art. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2020;214:107614. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Jin J, Peng X, Ramgolam VS, Markovic-Plese S. Simvastatin inhibits IL-17 secretion by targeting multiple IL-17-regulatory cytokines and by inhibiting the expression of IL-17 transcription factor RORC in CD4+ lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180(10):6988–96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak B, Mulhaupt F, Myit S, Mach F. Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator. Nat Med. 2000;6(12):1399–402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng X, Zhang K, Li J, Dong M, Yang J, An G, et al. Statins Induce the Accumulation of Regulatory T Cells in Atherosclerotic Plaque. Molecular Medicine. 2012;18(4):598–605. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Gao H, Zhao J, Ma L, Hu D. Safety and efficacy of bempedoic acid among patients with statin intolerance and those without: A meta-analysis and a systematic randomized controlled trial review. PLOS ONE. 2024;19(1):e0297854. [CrossRef]

- Ryan TE, Torres MJ, Lin CT, Clark AH, Brophy PM, Smith CA, et al. High-dose atorvastatin therapy progressively decreases skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity in humans. JCI Insight. 2024;9(4). Epub 20240222. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mo B, Ding Y, Ji Q. NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiovascular diseases: an update. Frontiers in Immunology. 2025;Volume 16 - 2025. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz Gregory G, Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt Deepak L, Bittner Vera A, Diaz R, et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(22):2097–107. [CrossRef]

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:2387–97. [CrossRef]

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas M-I, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(25):e34. [CrossRef]

- Kariuki JK, Imes CC, Engberg SJ, Scott PW, Klem ML, Cortes YI. Impact of lifestyle-based interventions on absolute cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2024;22(1):4–65. Epub 20240101. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Islam S, Li W, Liu L, et al. Cardiovascular Risk and Events in 17 Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries. New England Journal of Medicine. 371(9):818–27. [CrossRef]

- Corrao G, Ibrahim B, Nicotra F, Soranna D, Merlino L, Catapano AL, et al. Statins and the risk of diabetes: evidence from a large population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2225–32. Epub 20140626. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbudi A, Khairani S, Tjahjadi AI. Interplay Between Insulin Resistance and Immune Dysregulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Implications for Therapeutic Interventions. Immunotargets Ther. 2025;14:359–82. Epub 20250403. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Collado A, Humoud R, Kontidou E, Eldh M, Swaich J, Zhao A, et al. Erythrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles induce endothelial dysfunction through arginase-1 and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2025;135(10). Epub 20250320. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jain MK, Ridker PM. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e039034. [CrossRef]

- De Nardo D, Latz E. NLRP3 inflammasomes link inflammation and metabolic disease. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(8):373–9. Epub 20110704. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramsey LB, Johnson JA. Influence of SLCO1B1 genotype on statin therapy. Genetics in Medicine. 2021;23(8):1420–30. [CrossRef]

- El-Menyar A, Khan NA, Al Mahmeed W, Al Suwaidi J, Al-Thani H. Cardiovascular Implications of Lipoprotein(a) and its Genetic Variants: A Critical Review From the Middle East. JACC: Asia. 2025;5(7):847–64. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Clopton P, Brilakis ES, Marcovina SM, Khera A, Miller ER, et al. Relationship of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B-100 particles to race/ethnicity, apolipoprotein(a) isoform size, and cardiovascular risk factors: results from the Dallas Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;119(13):1711–9. Epub 20090323. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang H, Zhou Y, Nabavi SM, Sahebkar A, Little PJ, Xu S, et al. Mechanisms of Oxidized LDL-Mediated Endothelial Dysfunction and Its Consequences for the Development of Atherosclerosis. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022;Volume 9 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mitra S, Goyal T, Mehta JL. Oxidized LDL, LOX-1 and Atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 2011;25(5):419–29. [CrossRef]

- Tian K, Xu Y, Sahebkar A, Xu S. CD36 in Atherosclerosis: Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2020;22(10):59. [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg HN, Packard CJ, Chapman MJ, Borén J, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Averna M, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants: metabolic insights, role in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and emerging therapeutic strategies—a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society. European Heart Journal. 2021;42(47):4791–806. [CrossRef]

- Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2015;15(2):104–16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodgie FD, Yahagi K, Mori H, Romero ME, Finn AV, Virmani R. A Comprehensive Histological Analysis of Human Atherosclerotic Plaques: Implications for Understanding Residual Cardiovascular Risk. Am J Pathol. 2023;193(11):1501–17. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi M, Khayati S, Dehnavi S, Almahmeed W, Sukhorukov VN, Sahebkar A. Regulatory impact of statins on macrophage polarization: mechanistic and therapeutic implications. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2024;76(7):763–75. [CrossRef]

- Tan B, Chin KY. Potential role of geranylgeraniol in managing statin-associated muscle symptoms: a COVID-19 related perspective. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1246589. Epub 20231117. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dimmitt S, Stampfer H, Martin J, Kennedy M. Sufficient Statin Dose? Harms Increase More Than Benefits With Higher Doses. Heart, Lung and Circulation. 2023;32:S402. [CrossRef]

- Tarkin JM, Joshi FR, Evans NR, Chowdhury MM, Figg NL, Shah AV, et al. Detection of Atherosclerotic Inflammation by (68)Ga-DOTATATE PET Compared to [(18)F]FDG PET Imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(14):1774–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blankenberg S, Tiret L, Bickel C, Peetz D, Cambien F, Meyer J, et al. Interleukin-18 is a strong predictor of cardiovascular death in stable and unstable angina. Circulation. 2002;106(1):24–30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers AJ, Guan J, Trtchounian A, Hunninghake GM, Kaimal R, Desai M, et al. Association of Elevated Plasma Interleukin-18 Level With Increased Mortality in a Clinical Trial of Statin Treatment for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(8):1089–96. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang X, Kaiser H, Kvist-Hansen A, McCauley BD, Skov L, Hansen PR, et al. IL-17 Pathway Members as Potential Biomarkers of Effective Systemic Treatment and Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(1). Epub 20220105. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joshi NV, Vesey AT, Williams MC. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):705–13. [CrossRef]

- Lapa C, Reiter T, Li X. Imaging of CXCR4 expression in atherosclerotic plaques with the novel PET tracer 68Ga-pentixafor: comparison with 18F-FDG and histopathology. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2015;56(5):751–6. [CrossRef]

- null, n. Final Report of a Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(20):1921–30. [CrossRef]

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). European Heart Journal. 2018;39(33):3021–104. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy JW, McCarthy CP, Bruno RM, Brouwers S, Canavan MD, Ceconi C, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension: Developed by the task force on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). European Heart Journal. 2024;45(38):3912–4018. [CrossRef]

- Gisterå A, Hansson GK. The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(6):368–80. Epub 20170410. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taleb S, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. IL-17 and Th17 cells in atherosclerosis: subtle and contextual roles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(2):258–64. Epub 20140918. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Gao P, Li Q, Wang T, Guo S, Zhang J, et al. Arterial Adventitial Vasa Vasorum Hyperplasia involved in Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation in a Rabbit Model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2024;50(8):1273–9. [CrossRef]

- Subbotin, VM. Excessive intimal hyperplasia in human coronary arteries before intimal lipid depositions is the initiation of coronary atherosclerosis and constitutes a therapeutic target. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21(10):1578–95. [CrossRef]

- Pichardo-Almarza C, Diaz-Zuccarini V. Understanding the Effect of Statins and Patient Adherence in Atherosclerosis via a Quantitative Systems Pharmacology Model Using a Novel, Hybrid, and Multi-Scale Approach. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:635. Epub 20170913. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lei W, Hu J, Xie Y, Liu C, Chen X. Mathematical modelling of the effects of statins on the growth of necrotic core in atherosclerotic plaque. Math Model Nat Phenom. 2023;18. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang XZ, Liu. Regulatory T cells and macrophages in atherosclerosis: from mechanisms to clinical significance. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024;Volume 15 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Li Y, Kumar S. Hepatocyte-targeted siRNA silencing of FDFT1 reduces cholesterol synthesis and plasma LDL in preclinical models. Molecular Therapy. 2018;26(8):2211–21. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Patel R, Singh A. GalNAc-conjugated FDFT1 siRNA lowers LDL cholesterol and attenuates atherosclerosis in mouse models. Journal of Lipid Research. 2019;60(4):581–90. [CrossRef]

- Tan J, Li Y. Revisiting the interconnection between lipids and vitamin K metabolism: insights from recent research and potential therapeutic implications: a review. Nutrition & Metabolism. 2024;21(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Torii S, Ikari Y, Tanabe K, Kakuta T, Hatori M, Shioi A, et al. Plasma phylloquinone, menaquinone-4 and menaquinone-7 levels and coronary artery calcification. Journal of Nutritional Science. 2016;5:e48. Epub 2016/12/29. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhang JJ, Rizk R, Li X, Lee BG, Matthies ML, et al. Macrophages overexpressing interleukin-10 target and prevent atherosclerosis: Regression of plaque formation and reduction in necrotic core. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine. 2024;9(3):e10717. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt Deepak L, Libby P, Mason RP. Emerging Pathways of Action of Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA). JACC: Basic to Translational Science. 2025;10(3):396–400. [CrossRef]

- Welty FK, Schulte F, Alfaddagh A, Elajami TK, Bistrian BR, Hardt M. Regression of human coronary artery plaque is associated with a high ratio of (18-hydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acid + resolvin E1) to leukotriene B(4). Faseb j. 2021;35(4):e21448. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flight P, Rohde E, Lee R, Mazzola AM, Platt C, Mizoguchi T, et al. † VERVE-102, a clinical stage in vivo base editing medicine, leads to potent and precise inactivation of PCSK9 in preclinical studies. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2025;19(3, Supplement):e68. [CrossRef]

- Sinha A, Sachs N, Kratz E, Pauli J, Steigerwald S, Albrecht V, et al. Spatially resolved proteomic signatures of atherosclerotic carotid artery disease. medRxiv. 2025:2025.02.09.25321955. [CrossRef]

| Therapy Class | Trial(s) | Time for Initial Risk Reduction | Temporal Pattern | Plateau Observed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statins (moderate–high dose) | CTT meta-analysis [2,3,26] | Within 3–6 months | Rapid early ↓, then plateau | Yes | Clear early benefit, but ~75% of events still occur despite [LDL-C] <1.4 mmol/L |

| PCSK9 inhibitors | FOURIER, ODYSSEY OUTCOMES [31,64] | 12–24 months | Progressive over time | No | In FOURIER and ODDYSEY, event curves continue diverging through their 2-3 year follow-up, but longer-term trajectories remain to be determined |

| Ezetimibe | IMPROVE-IT [65] | ~24 months | Delayed, modest effect | Mild | Additive to statins; risk reduction ~6% over 6 years |

| Bempedoic acid | CLEAR Outcomes [61] | ≥24 months | Linear, steady | No | Benefit emerges gradually, consistent with an early plateau in statin curves, and raises the question of a statin-linked inflammatory floor |

| Lifestyle interventions | PREDIMED, PURE, observational cohorts [66,67,68] | 2–5 years | Slow, cumulative | Not applicable | Heterogeneous effects: within 2–5 year studies, no clear plateau is observed, but longer-term data are limited |

| Biomarker | Mechanistic Role | Interpretive Value | Preferred Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| ApoB | Structural protein for all atherogenic lipoproteins | Direct measure of total atherogenic particle burden | Immunoassay; preferable to LDL-C in residual risk evaluation |

| IL-1β | Primary NLRP3 inflammasome effector cytokine | Direct marker of inflammasome activation and macrophage priming | Plasma assay (ELISA or multiplex) |

| IL-18 | Co-product of NLRP3 activation | Correlation with plaque activity; elevated in persistent risk | Plasma assay; potential for plaque-specific imaging correlation |

| IL-18/IL-10 Ratio | Balance between inflammation and resolution | Indicator of inflammatory floor and impaired resolution capacity | Calculated from serum cytokine panel |

| TNF-α | Promotes foam cell persistence, metabolic dysfunction | Marker of chronic plaque inflammation and macrophage dysfunction | Serum or plasma; longitudinal tracking preferred |

| CRP | Downstream IL-6–driven acute-phase reactant | Systemic surrogate for residual inflammatory risk | Standard clinical immunoassay |

| Adiponectin | Anti-inflammatory adipokine is suppressed in insulin resistance | Negative correlation of NLRP3 activation | ELISA or multiplex adipokine panel |

| HOMA-IR | Composite index of insulin resistance | Proxy for systemic metabolic reinforcement of NLRP3 | Derived from fasting insulin and glucose |

| GLP-1 | Incretin reduced by statins via microbiota–bile acid axis | Lower levels flag insulin-resistance amplification under statins; candidate for UDCA rescue | Fasting plasma GLP-1 (stabilized tubes); paired with HOMA-IR |

| 1 | Square-bracket notation (e.g., [LDL-C]) denotes molar concentration throughout. |

| 2 | This mechanism is supported by murine and cell culture studies, full validated in human arterial macrophages is yet to occur. |

| 3 | In vitro models support OxPL–NLRP3 activation, the in vivo contribution of Lp(a) to this pathway is yet to be quantified. |

| 4 | The role of adaptive immune–macrophage crosstalk in this context has not yet been fully mapped, however, emerging data suggest that insulin resistance may modulate T-cell polarization and indirectly reinforce pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotypes. |

| 5 | Meta-analytic evidence links statin therapy to new-onset diabetes, with heightened risk in patients with pre-existing metabolic dysfunction—supporting a systemic feedback loop. |

| 6 | While IL-1β–induced insulin resistance is supported by human and animal data, the bidirectional loop involving macrophages remains under active investigation. |

| 7 | [CRP] reflects measured concentrations via hs-CRP assay, and there is a distinction between clinical targets and immunologic sufficiency. |

| 8 | Bentzon et al. have extensively characterized macrophage dynamics in plaque progression and regression models, forming a foundational framework for interpreting phenotypic transitions in atherosclerosis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).