Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

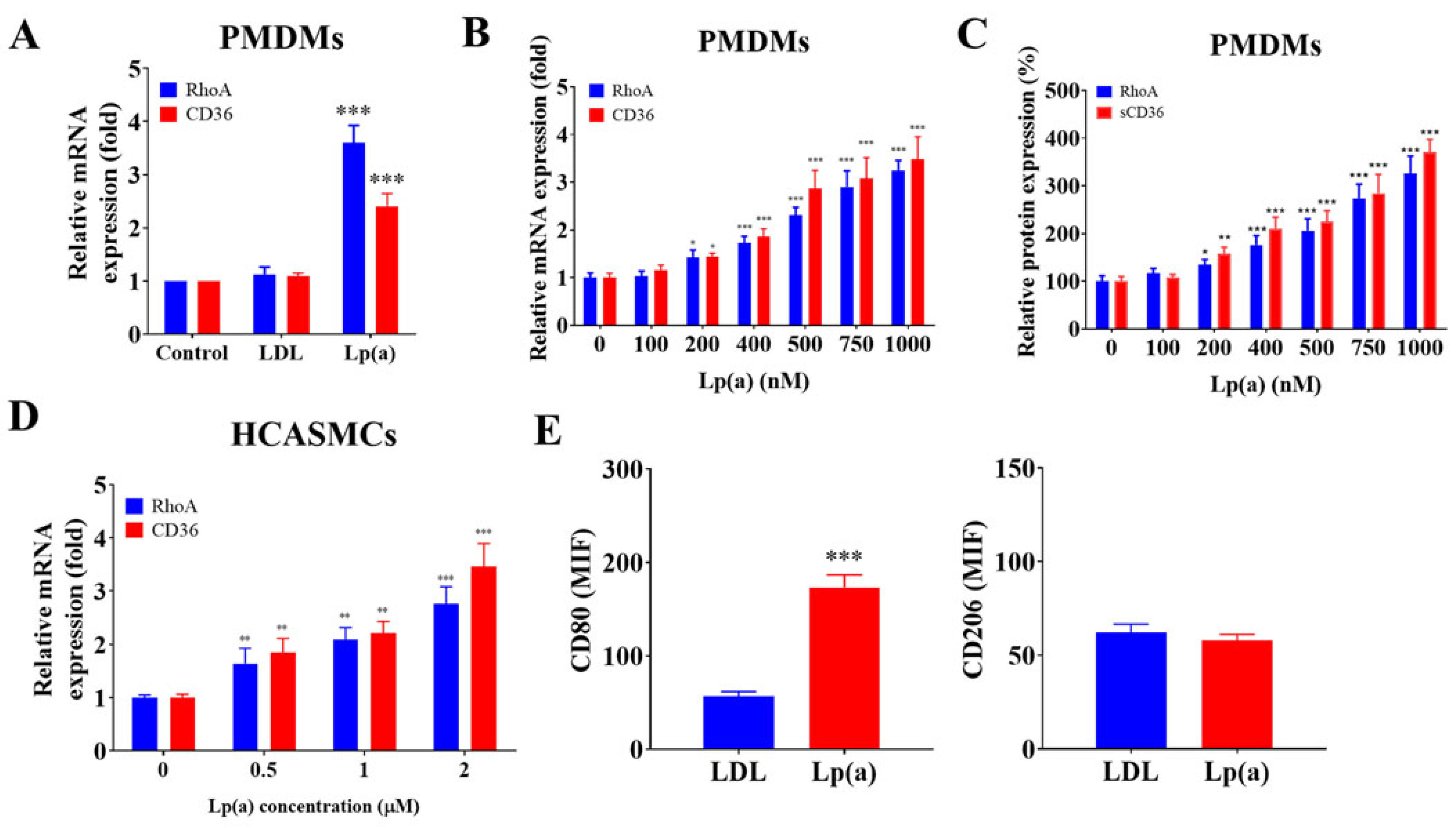

2.1. Study Cohort Baseline Characteristics

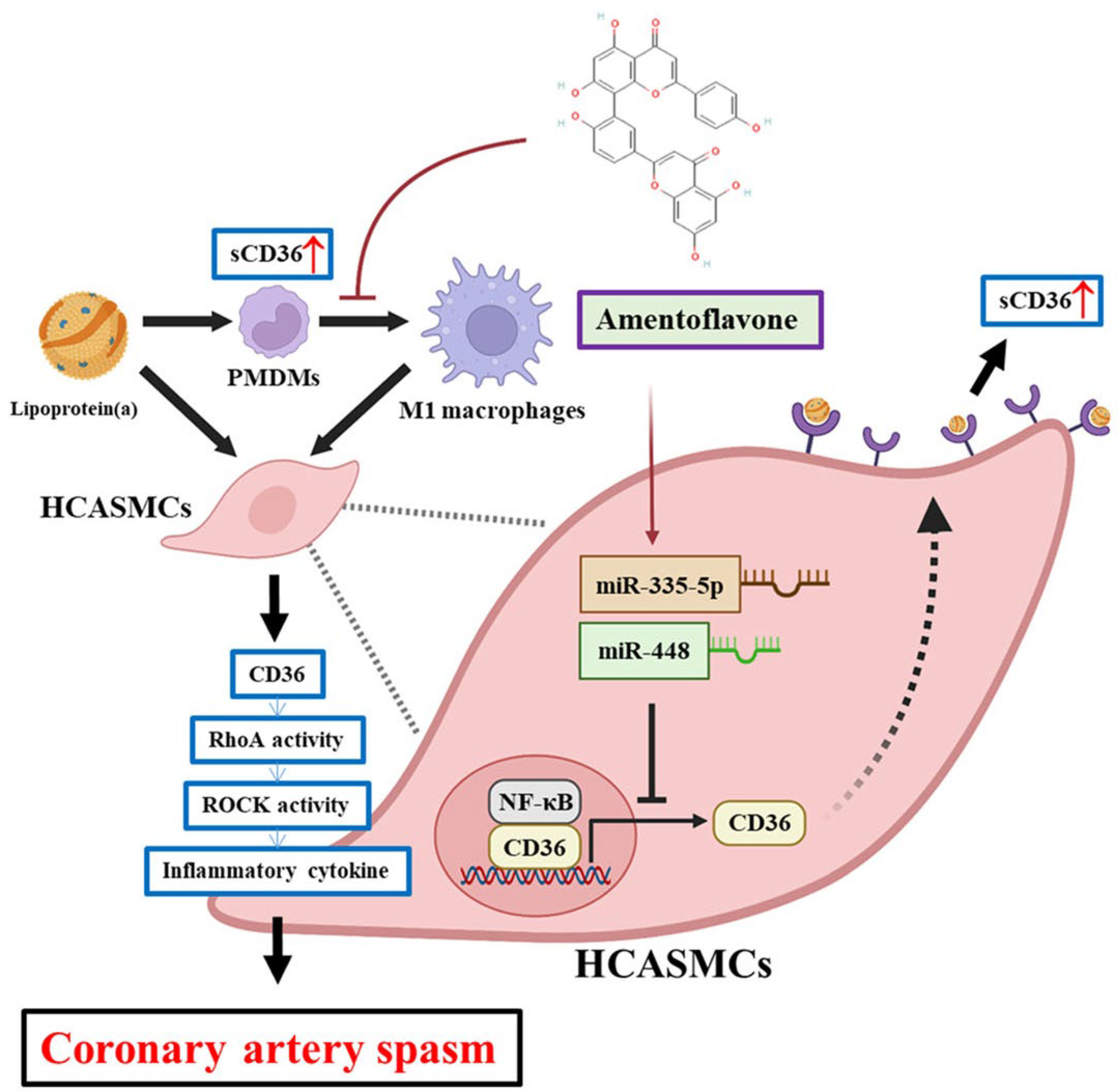

2.2. Correlation of Lp(a) with sCD36

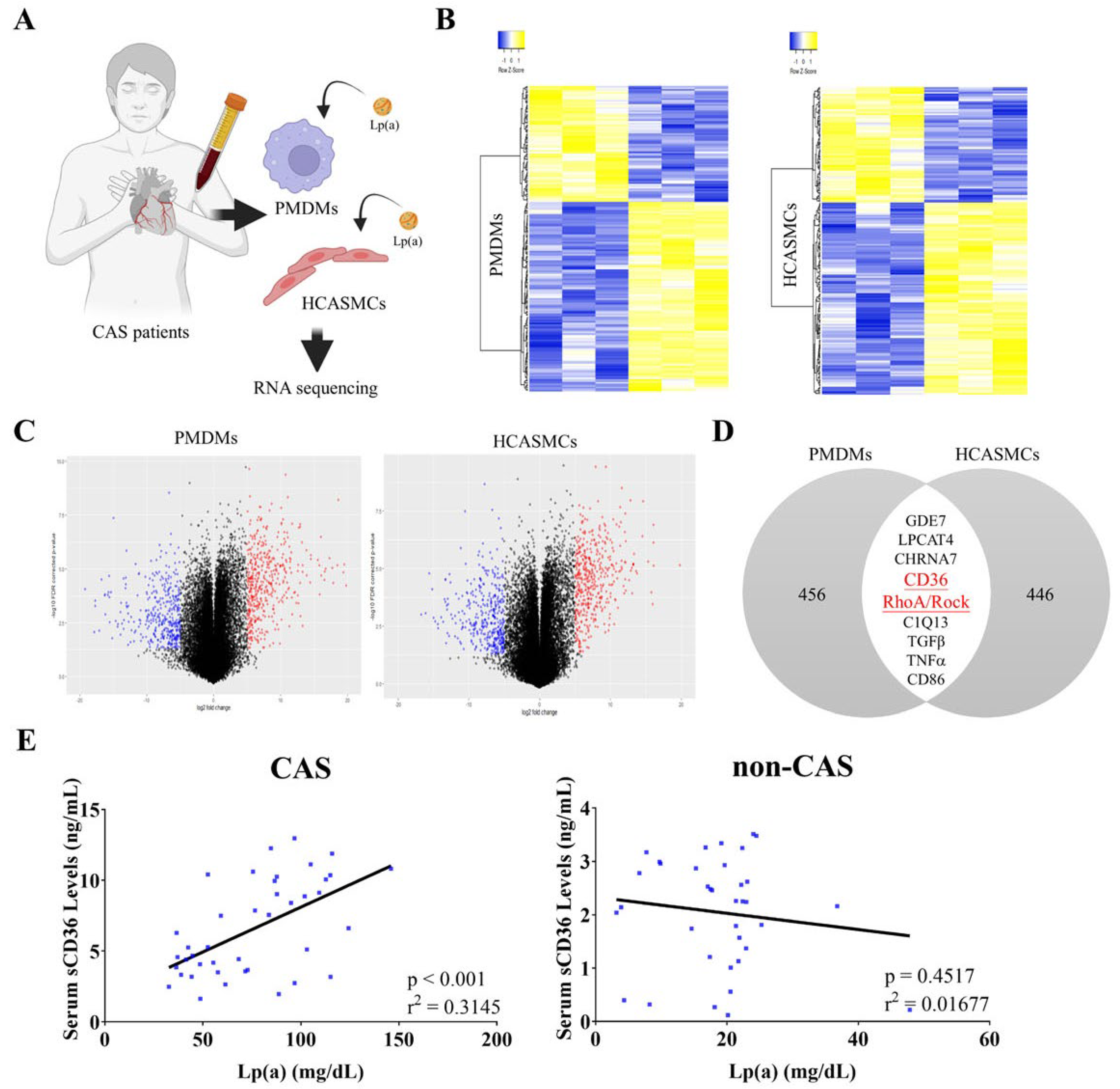

2.3. Lp(a) Stimulated CD36 and RhoA Expression in PMDMs, HCASMCs, and Preferentially Induced PMDM M1 Polarization

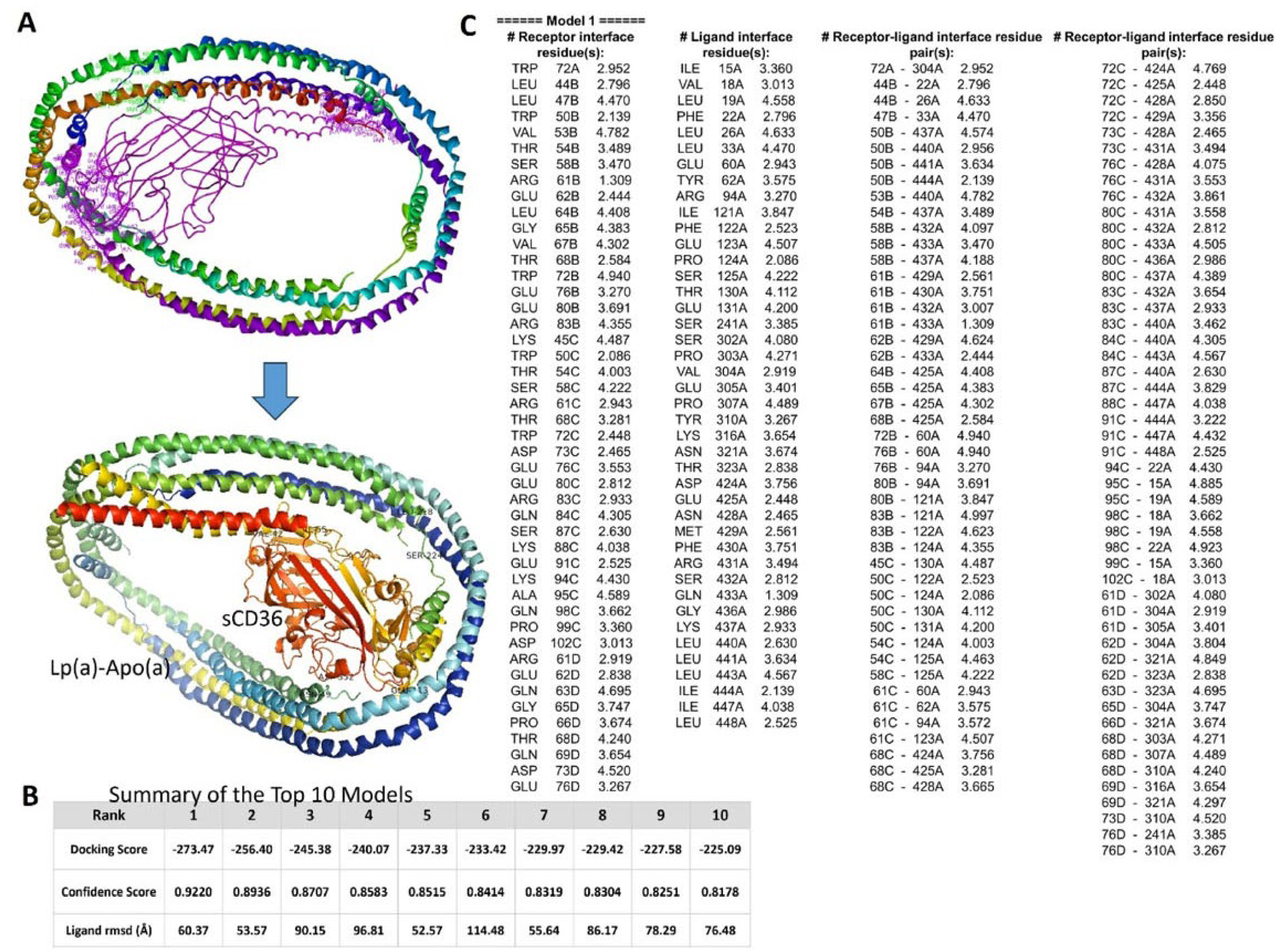

2.4. In Silico Molecular Docking to Examine Lp(a)/sCD36 Binding Interactions

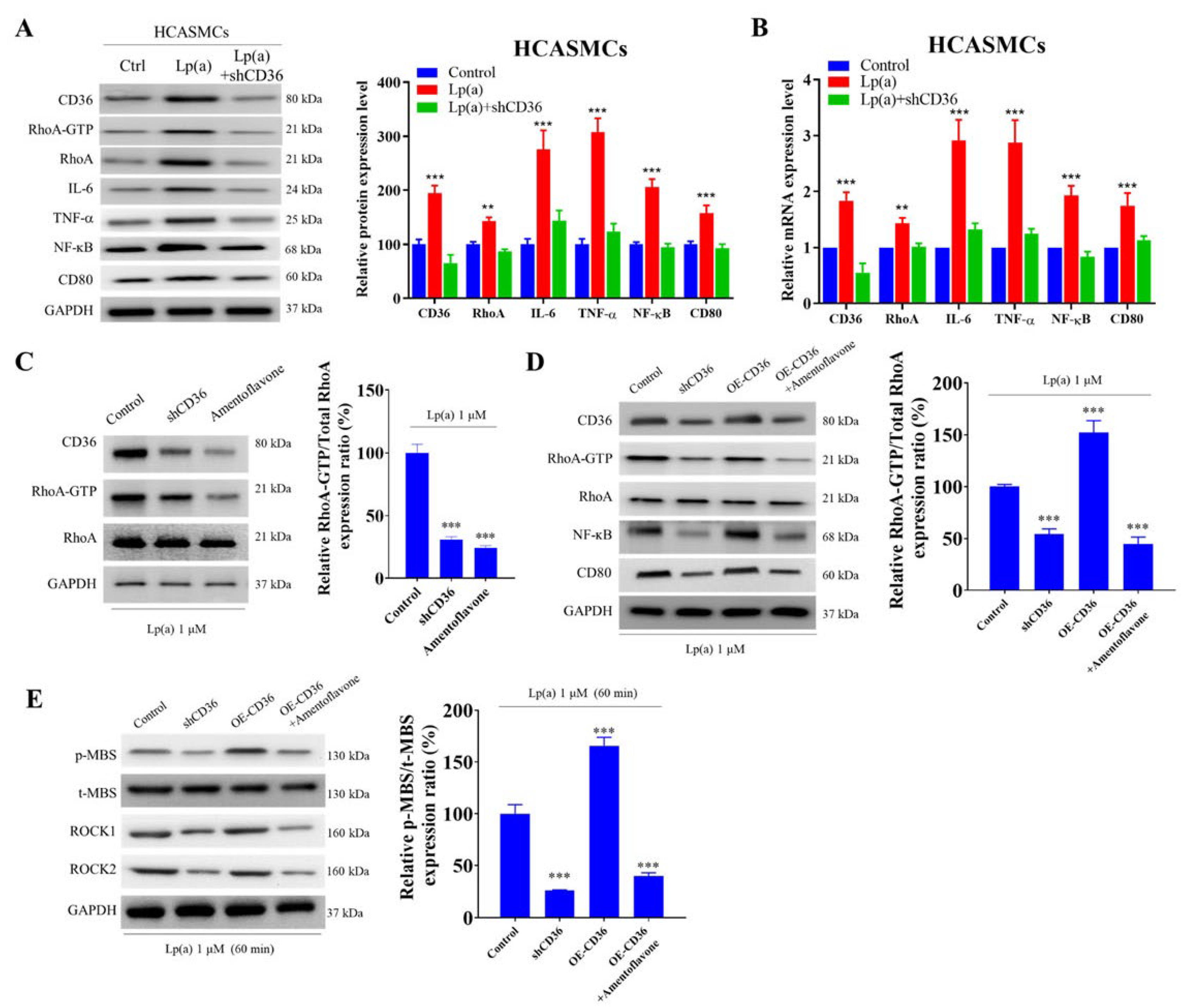

2.5. CD36 Knockdown Reduced Lp(a)-Induced Proinflammatory Signaling in HCASMCs

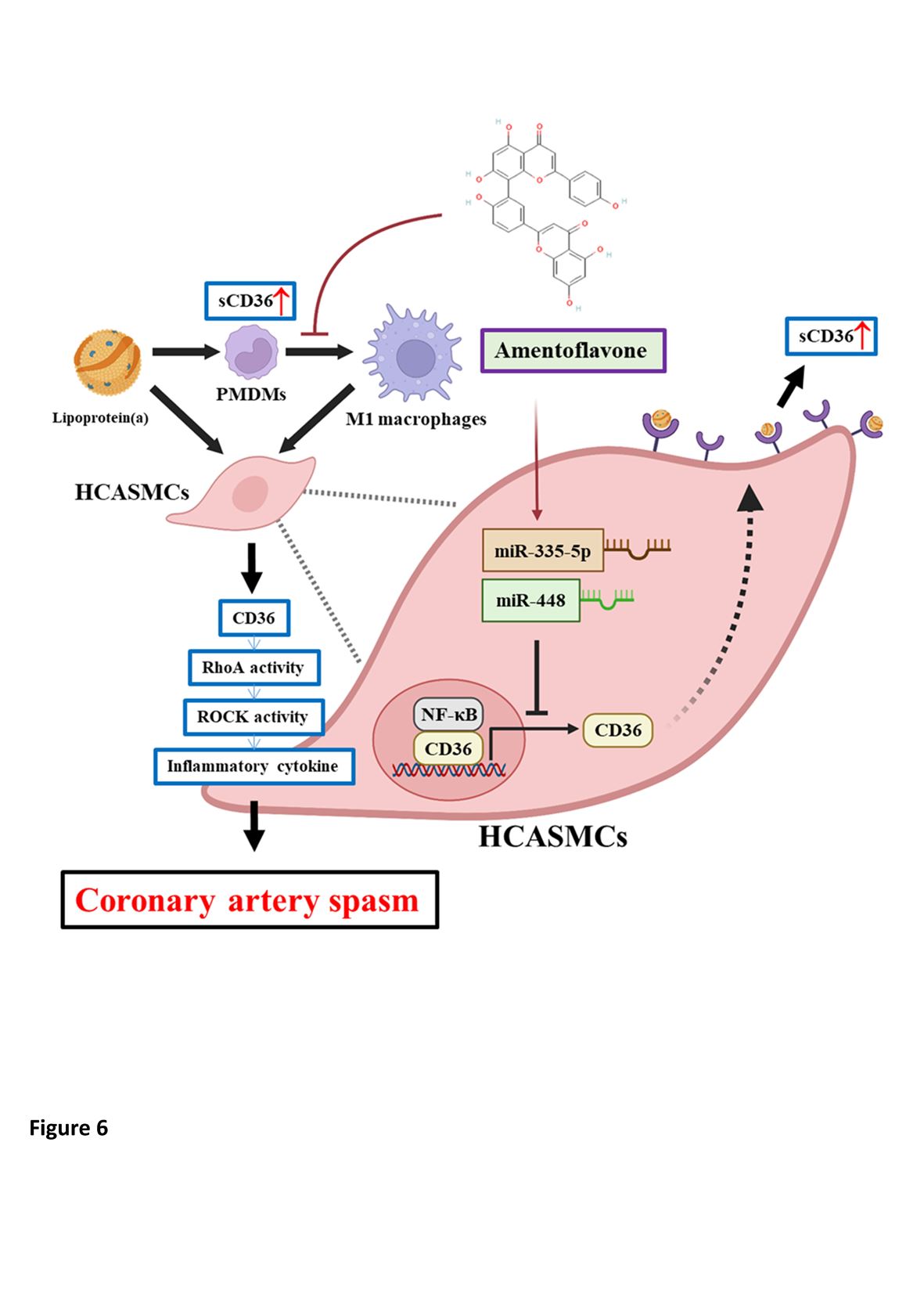

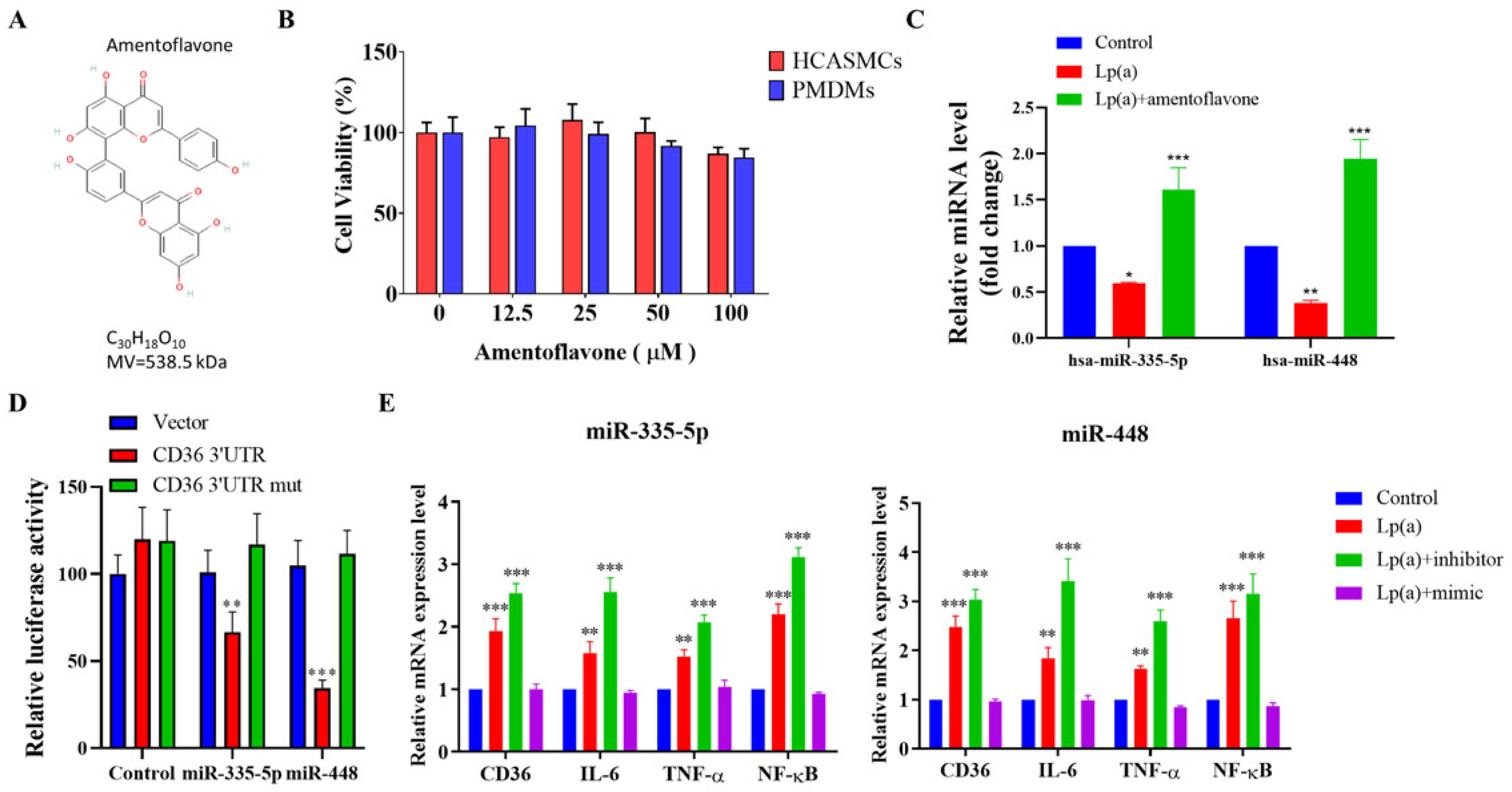

2.6. Epigenetic Regulation of Lp(a)-Triggered CD36, IL-6, TNF-α and NF-κB Expression in HCASMCs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells, Compounds, and Reagents

4.2. Study Population

4.3. Patient Data Collection

4.4. Spasm Provocation Test Protocol

4.5. Monocyte Isolation from Human Peripheral Blood

4.6. Monocyte Differentiation into Macrophages

4.7. HCASMCs Culture

4.8. Lp(a) Assay

4.9. CD36 Expression Analysis in HCASMCs

4.10. RNA Processing and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) for CD36, RhoA and miRNA

4.11. Molecular Docking

4.12. Western Blot Analysis

4.13. Flow Cytometry Analysis

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Writing Committee Members; Gulati, M. ; Levy, P.D.; Mukherjee, D.; Amsterdam, E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blankstein, R.; Boyd, J.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P.; Conejo, T.; et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2022, 16, 54–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.-J.; Hsu, K.-H.; Chang, N.-C.; Hung, M.-Y. Increased Numbers of Coronary Events in Winter and Spring Due to Coronary Artery Spasm: Effect of Age, Sex, Smoking, and Inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2047–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.-J. , Kuo, L.-T.; Cheng, C.W.; Chang, C.-P; Cherng, W.J. Comparison of peripheral monocyte counts in patients with and without coronary spasm and without fixed coronary narrowing. Am J Cardiol. 2004, 93, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.-J.; Hsu, K.-H.; Hu, W.-S.; Chang, N.-C.; Hung, M.-Y. C-reactive protein for predicting prognosis and its gender-specific associations with diabetes mellitus and hypertension in the development of coronary artery spasm. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e77655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.-J.; Cherng, W.-J.; Cheng, C.-W.; Li, L.-F. Comparison of serum levels of inflammatory markers in patients with coronary vasospasm without significant fixed coronary artery disease versus patients with stable angina pectoris and acute coronary syndromes with significant fixed coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006, 97, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.-Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Bamodu OA, Chen X, Lin YK, Hu P, Chang NC, Pang JS, Yeh CT. Activation of the monocytic α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulates oxidative stress and inflammation-associated development of coronary artery spasm via a p38 MAP-kinase signaling-dependent pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018, 120, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugiyama, K.; Yasue, H.; Okumura, K.; Ogawa, H.; Fujimoto, K.; Nakao, K.; Yoshimura, M.; Motoyama, T; Inobe, Y. ; Kawano, H. Nitric oxide activity is deficient in spasm arteries of patients with coronary spastic angina. Circulation. 1996, 94, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, K.; Nakagawa, K.; Yoshida, N.; Taguchi, Y.; Inoue, H. Lipoprotein(a) is a risk factor for occurrence of acute myocardial infarction in patients with coronary vasospasm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 35, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.-Y.; Witztum, J.L.; Tsimikas, S. New therapeutic targets for calcific aortic valve stenosis: the lipoprotein(a)-lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2-oxidized phospholipid axis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014, 63, 478–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmark, C.; Dewan, A.; Orsoni, A.; Merki, E.; Miller, E.R.; Shin, M.J.; Binder, C.J.; Hörkkö, S.; Krauss, R.M.; Chapman, M.J.; et al. A novel function of lipoprotein [a] as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 2230–2239. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-K.; Yeh, C.-T.; Kuo, K.-T.; Fong, I.-H.; Yadav, V.-K.; Kounis, N.G.; Hu, P.; Hung, M.-Y. Apolipoprotein (a)/Lipoprotein(a)-Induced Oxidative-Inflammatory α7-nAChR/p38 MAPK/IL-6/RhoA-GTP Signaling Axis and M1 Macrophage Polarization Modulate Inflammation-Associated Development of Coronary Artery Spasm. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 9964689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.-J.; Cherng, W.-J.; Hung, M.-Y.; Kuo, L.-T.; Cheng, C.-W.; Wang, C.-H.; Yang, N.-I.; Liao, J.K. Increased leukocyte Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase activity predicts the presence and severity of coronary vasospastic angina. Atherosclerosis. 2012, 221, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchałowicz, K.; Rać, M.E. The Multifunctionality of CD36 in Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications-Update in Pathogenesis, Treatment and Monitoring. Cells. 2020, 9, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewmalee, J.; Ontawong, A.; Duangjai, A.; Tansakul, C.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Muanprasat, C.; Srimaroeng, C. High-Efficacy α,β-Dehydromonacolin S Improves Hepatic Steatosis and Suppresses Gluconeogenesis Pathway in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Reyna, B.; Padilla-Gutiérrez, J.R.; Aceves-Ramírez, M.; García-Garduño, T.C.; Martínez-Fernández, D.E.; Jacobo-García, J.J.; Valdés-Alvarado, E.; Valle, Y. Genetic variants, gene expression, and soluble CD36 analysis in acute coronary syndrome: Differential protein concentration between ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and unstable angina. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022, 36, e24529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodart, V.; Febbraio, M.; Demers, A.; McNicoll, N.; Pohankova, P.; Perreault, A.; Sejlitz, T.; Escher, E.; Silverstein, R.L.; Lamontagne, D.; et al. CD36 mediates the cardiovascular action of growth hormone-releasing peptides in the heart. Circ Res. 2002, 90, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.-Y.; Kounis, N.G.; Lu, M.-Y.; Hu, P. Myocardial Ischemic Syndromes, Heart Failure Syndromes, Electrocardiographic Abnormalities, Arrhythmic Syndromes and Angiographic Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Spasm: Literature Review. Int J Med Sci. 2020, 17, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorand, B.; Löwel, H.; Schneider, A.; Kolb, H.; Meisinger, C.; Fröhlich, M.; Koenig, W. C-reactive protein as a predictor for incident diabetes mellitus among middle-aged men: results from the MONICA Augsburg cohort study, 1984-1998. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, L.S.; Sousa Fialho, M.D.L.; Yea, G.; Coumans, W.A.; West, J.A.; Kerr, M.; Carr, C.A.; Luiken, J.J.F.P.; Glatz, J.F.C.; Evans, R.D.; et al. Inhibition of sarcolemmal FAT/CD36 by sulfo-N-succinimidyl oleate rapidly corrects metabolism and restores function in the diabetic heart following hypoxia/reoxygenation. Cardiovasc Res. 2017, 113, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, J.F.; Angin, Y.; Steinbusch, L.K.; Schwenk, R.W.; Luiken, J.J. CD36 as a target to prevent cardiac lipotoxicity and insulin resistance. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2013, 88, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.W.; Choi, B.G.; Rha, S.W. Impact of Insulin Resistance on Acetylcholine-Induced Coronary Artery Spasm in Non-Diabetic Patients. Yonsei Med J. 2018, 59, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.-J.; Chang, N.-C.; Hu, P.; Chen, T.-H.; Mao, C.-T.; Yeh, C.-T.; Hung, M.-Y. Association between Coronary Artery Spasm and the risk of incident Diabetes: A Nationwide population-based Cohort Study. Int J Med Sci. 2021, 18, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handberg, A.; Lopez-Bermejo, A.; Bassols, J.; Vendrell, J.; Ricart, W.; Fernandez-Real, J.M. Circulating soluble CD36 is associated with glucose metabolism and interleukin-6 in glucose-intolerant men. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2009, 6, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, A.; Abe, T.; Hochrainer, K.; Shimamura, M.; Anrather, J.; Racchumi, G.; Zhou, P.; Iadecola, C. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation and postischemic inflammation are suppressed in CD36-null mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Tergaonkar, V. Rho protein GTPases and their interactions with NFκB: crossroads of inflaowiojldflmmation and matrix biology. Biosci Rep. 2014, 34, e00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.-W.; Wu, M.-S.; Liu, Y.; Lu, M.; Guo, J.-D.; Meng, Y.-H.; Zhou, Y.-H. SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of NF-κB inhibits the MLCK/MLC2 pathway and the expression of ET-1, thus alleviating the development of coronary artery spasm. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021, 320, H458–H468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; de Bont, N.; Demacker, P.N.; Kullberg, B.J.; Jacobs, L.E.; Verver-Jansen, T.J.; Stalenhoef, A.F.; Van der Meer, J.W. Lipoprotein(a) inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha production by human mononuclear cells. Infect Immun. 1998, 66, 2365–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvietys, P.R.; Granger, D.N. Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the vascular responses to inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012, 52, 556–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, Q.; Toan, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Liang, J. SERCA overexpression reduces reperfusion-mediated cardiac microvascular damage through inhibition of the calcium/MCU/mPTP/necroptosis signaling pathways. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, D.; Shoelson, S.E. Immunometabolism: an emerging frontier. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, W.; Silverstein, R.L. CD36, a signaling receptor and fatty acid transporter that regulates immune cell metabolism and fate. J Exp Med. 2022, 219, e20211314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, H.Y.; Pearce, S.F.; Yesner, L.M.; Schindler, J.L.; Silverstein, R.L. Regulated expression of CD36 during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation: potential role of CD36 in foam cell formation. Blood. 1996, 87, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tontonoz, P.; Nagy, L.; Alvarez, J.G.; Thomazy, V.A.; Evans, R.M. PPARgamma promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell. 1998, 93, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesner, L.M.; Huh, H.Y.; Pearce, S.F.; Silverstein, R.L. Regulation of monocyte CD36 and thrombospondin-1 expression by soluble mediators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996, 16, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podrez, E.A.; Byzova, T.V.; Febbraio, M.; Salomon, R.G.; Ma, Y.; Valiyaveettil, M.; Poliakov, E.; Sun, M.; Finton, P.J.; Curtis, B.R.; et al. Platelet CD36 links hyperlipidemia, oxidant stress and a prothrombotic phenotype. Nat Med. 2007, 13, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsted, A.; Kamstrup, P.R.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Lipoprotein(a): fasting and nonfasting levels, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2014, 234, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missala, I.; Kassner, U.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E. A Systematic Literature Review of the Association of Lipoprotein(a) and Autoimmune Diseases and Atherosclerosis. Int J Rheumatol. 2012, 2012, 480784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroubakis, I.E. , Malliaraki, N.; Vardas, E.; Ganotakis, E.; Margioris, A.N.; Manousos, O.N.; Kouroumalis, E.A. Increased levels of lipoprotein (a) in Crohn’s disease: a relation to thrombosis? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001, 13, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.; Herrlinger, S.; Pruy, A.; Metzger, T.; Wanner, C. Inflammation enhances cardiovascular risk and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1999, 55, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Abe, A.; Seishima, M.; Makino, K.; Noma, A.; Kawade, M. Transient changes of serum lipoprotein(a) as an acute phase protein. Atherosclerosis. 1989, 78, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, M.B.; Koschinsky, M.L. Lipoprotein (a): truly a direct prothrombotic factor in cardiovascular disease? J Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patthy, L.; Trexler, M.; Váli, Z.; Bányai, L.; Váradi, A. Kringles: modules specialized for protein binding. Homology of the gelatin-binding region of fibronectin with the kringle structures of proteases. FEBS Lett. 1984, 171, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, S.P.A.; Schneider, W.J. Lipoprotein(a) catabolism: a case of multiple receptors. Pathology. 2019, 51, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, S.; Oma, I.; Hagve, T.A.; Saatvedt, K.; Brosstad, F.; Mikkelsen, K.; Rydningen, H.; Risnes, I.; Almdahl, S.M.; Ueland, T.; et al. Levels of Lipoprotein (a) in patients with coronary artery disease with and without inflammatory rheumatic disease: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e030651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, H.K.; Laudes, M.; Krone, W.; Gouni-Berthold, I. Association between the interleukin-6 promoter polymorphism -174G/C and serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations in humans. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e24719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Schulte, D.M.; Türk, K.; Freitag-Wolf, S.; Hampe, J.; Zeuner, R.; Schröder, J.O.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Berthold, H.K.; Krone, W.; et al. IL-6 blockade by monoclonal antibodies inhibits apolipoprotein (a) expression and lipoprotein (a) synthesis in humans. J Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Scavini, M.; Orlando, R.A.; Murata, G.H.; Servilla, K.S.; Tzamaloukas, A.H.; Schrader, R.; Bedrick, E.J.; Burge, M.R.; Abumrad, N.A.; et al. Increased CD36 expression signals monocyte activation among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010, 33, 2065–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Febbraio, M.; Klenotic, P.A.; Kennedy, D.J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Gohara, A.F.; Li, O.; Belcher, A.; Kuang, B.; et al. CD36 Enhances Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Development of Neointimal Hyperplasia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019, 39, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa-Kawase, M.; Masuda, D.; Yamashita, T.; Kawase, R.; Nakaoka, H.; Inagaki, M.; Nakatani, K.; Tsubakio-Yamamoto, K.; Ohama, T.; Matsuyama, A.; et al. Patients with CD36 deficiency are associated with enhanced atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2012, 19, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L.S.; Voran, J.; Frank, D.; Rangrez, A.Y. RhoA: a dubious molecule in cardiac pathophysiology. J Biomed Sci. 2021, 28, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segain, J.P.; Raingeard de la Blétière, D.; Sauzeau, V.; Bourreille, A.; Hilaret, G.; Cario-Toumaniantz, C.; Pacaud, P.; Galmiche, J.P.; Loirand, G. Rho kinase blockade prevents inflammation via nuclear factor kappa B inhibition: evidence in Crohn’s disease and experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003, 124, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, H.; Sunamura, S.; Satoh, K. RhoA/Rho-Kinase in the Cardiovascular System. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiendl, H.; Mitsdoerffer, M.; Schneider, D.; Chen, L.; Lochmüller, H.; Melms, A.; Weller, M. Human muscle cells express a B7-related molecule, B7-H1, with strong negative immune regulatory potential: a novel mechanism of counterbalancing the immune attack in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1892–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Manes, T.D.; Pober, J.S.; Tellides, G. Human vascular smooth muscle cells lack essential costimulatory molecules to activate allogeneic memory T cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010, 30, 1795–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotton, C.J.; Martinez, F.O.; Smelt, M.J.; Sironi, M.; Locati, M.; Mantovani, A.; Sozzani, S. Transcriptional profiling reveals complex regulation of the monocyte IL-1 beta system by IL-13. J Immunol. 2005, 174, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Schulte, M.L.; Volberding, P.; Gerbec, Z.; Zimmermann, M.T.; Zeighami, A.; et al. Mitochondrial Metabolic Reprogramming by CD36 Signaling Drives Macrophage Inflammatory Responses. Circ Res. 2019, 125, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.; Hong, H.S.; Bader, J.E.; Sugiura, A.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Rathmell, J.C. A guide to interrogating immunometabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021, 21, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinetti-Gbaguidi, G.; Colin, S.; Staels, B. Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015, 12, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, F.M.; Bekkering, S.; Kroon, J.; Yeang, C.; Van den Bossche, J.; van Buul, J.D.; Ravandi, A.; Nederveen, A.J.; Verberne, H.J.; Scipione, C.; et al. Oxidized Phospholipids on Lipoprotein(a) Elicit Arterial Wall Inflammation and an Inflammatory Monocyte Response in Humans. Circulation. 2016, 134, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicher, A.; Heeschen, C.; Mohaupt, M.; Cooke, J.P.; Zeiher, A.M.; Dimmeler, S. Nicotine strongly activates dendritic cell-mediated adaptive immunity: potential role for progression of atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 2003, 107, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Sica, A.; Locati, M. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity. 2005, 23, 344–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.-H.; Lai, C.-Y.; Yeh, D.-W.; Liu, Y.-L.; Su, Y.-W.; Hsu, L.-C.; Chang, C.-H.; Catherine Jin, S.-L.; Chuang, T.-H. Involvement of M1 Macrophage Polarization in Endosomal Toll-Like Receptors Activated Psoriatic Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 3523642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardekani, A.M.; Naeini, M.M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Diseases. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2010, 2, 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.S.; Kim, I.; Oh, G.C.; Han, J.K.; Yang, H.M.; Park, K.W.; Cho, H.J.; Kang, H.J.; Koo, B.K.; Chung, W.Y.; et al. Diagnostic Utility and Pathogenic Role of Circulating MicroRNAs in Vasospastic Angina. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Pan, H.T. microRNA profiles of serum exosomes derived from children with nonalcoholic fatty liver. Genes Genomics. 2022, 44, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Mizuno, Y.; Harada, E.; Kashiwagi, Y.; Yoshimura, M.; Murohara, T.; Yasue, H. Pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activator, suppresses coronary spasm. Coron Artery Dis. 2014, 25, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Qin, H.; Liao, M.; Zheng, E.; Luo, X.; Xiao, A.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Wei, L.; Zhao, L.; et al. CD36 promotes de novo lipogenesis in hepatocytes through INSIG2-dependent SREBP1 processing. Mol Metab. 2022, 57, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, G.; Lou, Z. Role of the Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein Pathway in Tumorigenesis. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Sui, L.; Hong, X.; Yang, M.; Li, W. MiR-448 promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in through directly targeting MEF2C. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017, 24, 22294–22300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H.; Otogoto, S.; Chiba, Y.; Abe, K.; Misawa, M. Involvement of p42/44 MAPK and RhoA protein in augmentation of ACh-induced bronchial smooth muscle contraction by TNF-alpha in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004, 97, 2154–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, Z.Z.; Zhuang, Q.Z.; Tang, W.Z.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, X.Z. Amentoflavone prevents ox-LDL-induced lipid accumulation by suppressing the PPARγ/CD36 signal pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2021, 431, 115733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, R.J.; Chatterjee, K.; Daley, J.; Douglas, J.S.; Fihn, S.D.; Gardin, J.M.; Grunwald, M.A.; Levy, D.; Lytle, B.W.; O’Rourke, R.A.; et al. ACC/AHA/ACP-ASIM guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: executive summary and recommendations. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina). Circulation. 1999, 99, 2829–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of patients with vasospastic angina (coronary spastic angina) (JCS 2008): digest version. Circ J. 2010, 74, 1745–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtlscherer, S.; Breuer, S.; Schächinger, V.; Dimmeler, S.; Zeiher, A.M. C-reactive protein levels determine systemic nitric oxide bioavailability in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2004, 25, 1412–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Mahmood, T.; Yang, P.C. Western blot: technique, theory and trouble shooting. N Am J Med Sci. 2014, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Controls (n = 36) | CAS (n = 41) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56.6 ± 15.4 | 56.3 ± 11.9 | 0.94 | |||

| Male sex, n (%) | 12 (33) | 23 (56) | 0.045 | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.5 ± 4.1 | 26.0 ± 4.5 | 0.12 | |||

| Current smoker, n (%) | 4 (11) | 15 (41) | 0.004 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | 0.38 | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5 (14) | 9 (24) | 0.26 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 113 ± 14 | 115 ± 17 | 0.56 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 67 ± 10 | 71 ± 10 | 0.10 | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 67 ± 9 | 71 ± 14 | 0.24 | |||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 65 ± 5 | 65 ± 7 | 0.98 | |||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 171 ± 35 | 166 ± 33 | 0.56 | |||

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 85 ± 51 | 99 ± 54 | 0.26 | |||

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 53 ± 12 | 47 ± 12 | 0.034 | |||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 95 ± 29 | 98 ± 27 | 0.66 | |||

| Lipoprotein (a), mg/dL | 18.6 ± 8.7 | 75.9 ± 29.4 | 0.001 | |||

| sCD36 | 2.1 ± 1 | 6.6 ± 3.3 | 0.001 | |||

| Peripheral leukocytes, /mm3 | 6006 ± 1459 | 6786 ± 2182 | 0.088 | |||

| Monocytes, /mm3 | 458 ± 159 | 551 ± 178 | 0.027 | |||

| Macrophage, /mm3 | 113 ± 36 | 411 ± 113 | 0.001 | |||

| Lymphocytes, /mm3 | 1725 ± 643 | 1669 ± 866 | 0.76 | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.4 ± 1.5 | 14.1 ± 1.3 | 0.03 | |||

| Hematocrit, % | 39.0 ± 5.0 | 41.3 ± 3.6 | 0.026 | |||

| Platelet, ×103/mm3 | 222 ± 57 | 241 ± 61 | 0.18 | |||

| hs-CRP, mg/L* | 0.63 (0.26–1.40) | 0.70 (0.21–0.98) | 0.31 | |||

| Provoked coronary artery | ||||||

| Left anterior descending artery, n (%) | 10 (24) | |||||

| Left circumflex artery, n (%) | 1 (2) | |||||

| Right coronary artery, n (%) | 32 (78) | |||||

| Number of spastic arteries | ||||||

| One-vessel spasm, n (%) | 35 (90) | |||||

| Two-vessel spasm, n (%) | 4 (10) | |||||

| Three-vessel spasm, n (%) | 0 (0) | |||||

| Medications | A | D | A | D | A | D |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 31 (86) | 33 (81) | 31 (89) | 36 (88) | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| β-blockers, n (%) | 34 (94) | 34 (83) | 18 (51) | 7 (17) | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 4 (11) | 11 (27) | 17 (49) | 39 (95) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 0.35 | 0.91 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker, n (%) | 7 (19) | 12 (29) | 7 (20) | 11 (27) | 0.32 | 0.49 |

| Nitrates, n (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.93 | 0.28 |

| Statins, n (%) | 10 (28) | 20 (49) | 11 (31) | 22 (54) | 0.06 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).