Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Time

2.2. Survey Design

2.3. Study Populations

2.4. Sample Size and Sampling Strategies

2.5. Data Collection Methods and Instruments

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

2.7. Ethical Consideration

3. Result

3.1. Stock Management

3.1.1. Stock Management at Central and EPSS Hubs

“Regarding stock management, we usually set the minimum and maximum plan. We monitor monthly stock, and branches send their report quarterly, but they send their monthly vaccine stock in total too. Then we take stock from the head office and check if that stock is within the range.” KII, EPSS Central level

3.2. Vaccine Stock Management at Lowest Distribution and Service Provision Levels

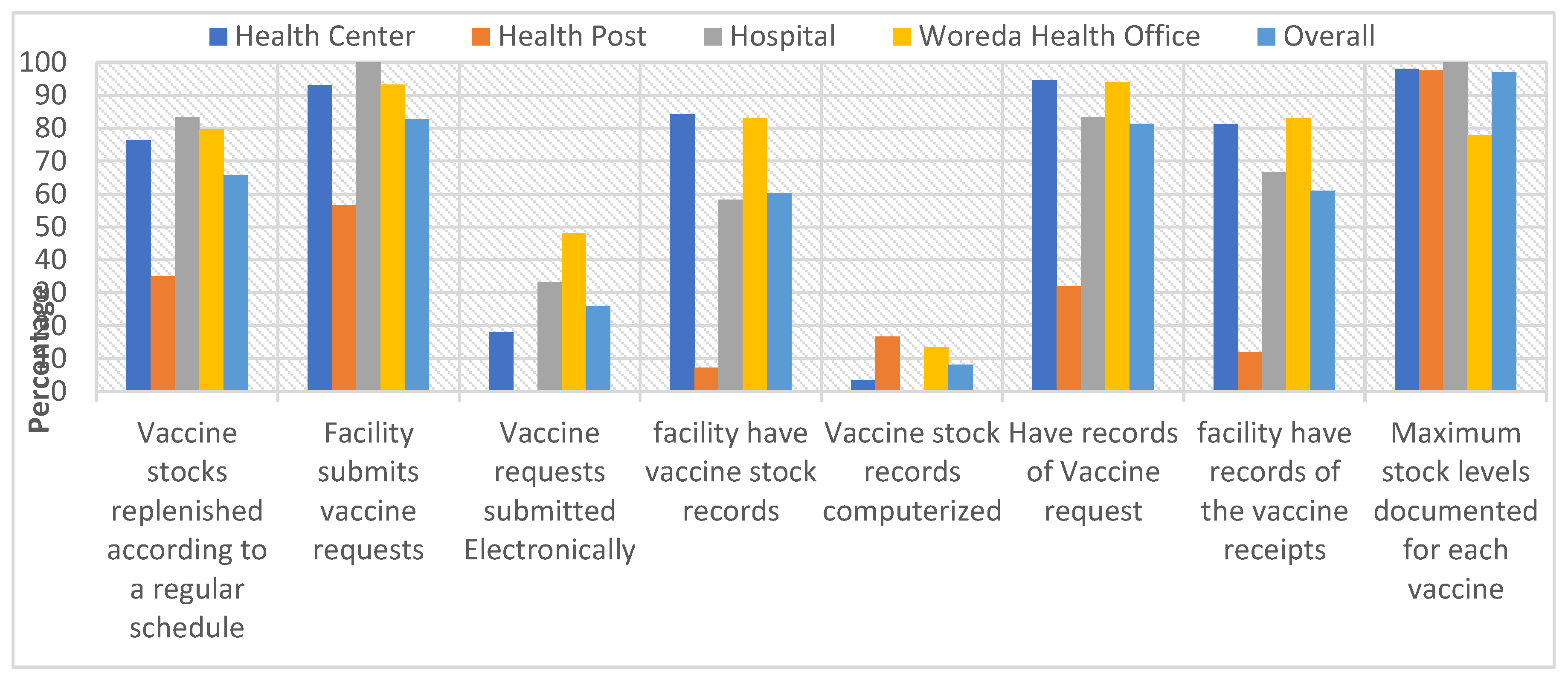

3.3. Stock Records at Lowest Distribution and Service Provision Levels

“We register vaccine supplies on stock management ledger book monthly as collected from woreda health office and distribute it to health posts of our catchment even it is currently interrupted due not trained/ experienced new EPI focal.” KII, HC_ EPI focal

“The other challenge is those of people who are dropout from the program, they are not in the camp. Maybe they are going to South Sudan, or they are going to the border or else they are going to gold mining. This dropout rate is not going to be traced on time. They came after nine months something, something.” KII, GM HF EPI focal

- Utilization of available capacity at lowest distribution and service provision levels

“We keep safety of vaccine according to cold chain management systems for example: which antigens are heat /cold sensitive and assigning place accordingly the fridge compartments and fridge tag monitoring systems twice a day and if high arm maintaining, by doing shake test method we can evaluate the antigens in the facility. In our facility there is a selected room for only cold chain and locked to protect untrained professionals.” KII, HCEPI Focal_SD

“There is an open vial policy, and we give training on that. For example, there are vaccines that have a high dose, like measles and BCG. For that, there are policies, guides, and temperature monitoring, which are critical issues and key performance indicators. KII, National level partner

3.4. Distribution Practice of Vaccines and Dry Goods

3.4.1. Transportation and Distribution of Vaccines and Dry Goods at Central and EPSS Hubs

“…EPSSA should maximize direct supply site and minimize indirect supply approach for vaccine supply distribution.” KII, Regional EPI focal person

3.5. Distribution of Vaccines and Dry Goods at Lower Distribution and Service Provision Levels

“Ethiopia’s immunization supply chain has undergone a transformation over the years. In the past, it was a vertical system where resources were distributed from health protection to region, from region to zone, and from zone to district. However, according to the Ethiopian pharmaceutical master plan, resources should go through EPSS in a coordinated manner… resources will be delivered to health facilities in two ways from 2018. One is that our EPSS branches will deliver direct resources to certain health facilities as EPSS branches in the districts. After that, the resource is transferred to the district, for example, if a district has four or five health centers. Then the health centers will distribute to health posts. The health institutions that EPSS delivers directly use their own.” KII, Partner National level

“As I have said we are bringing vaccines by using motorcycle and we may not bring sufficient number of vaccines to be maintained in the stock. The stock may be maintained for not more than two weeks. Had it been a vehicle we may maintain for longer period of time (for a month or more).” KII, AMH HF EPI focal

Discussion

Conclusion

Recommendation

- Implement measures to improve vaccine forecasting at the service provision level based on updated head counts and eligible population at the micro level through the health extension workers and considering migration and cross-boundary movement.

- Cascading implementation of a computerized stock management systems at all levels of the supply chain and use of standardized leisure books at the lower distribution and service provision levels to improve organization, reduce stock-outs, and minimize vaccine wastage.

- To ensure effectiveness of last-mile delivery, address challenges related to vehicle availability and transportation infrastructure to ensure timely and efficient vaccine delivery, especially at lower levels. The counties policy/SOP should address transportation logistics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Median | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual number of BCG dose | Consumed | 2255.03 | 0 | 8064000 |

| administered | 1130.438 | 0 | 4032000 | |

| Annual number of bOPV dose | Consumed | 4976.873 | 0 | 17920000 |

| administered | 4468.292 | 0 | 16128000 | |

| Annual number of DTwP-HepB-Hib dose | Consumed | 3365.999 | 38.12 | 11974737 |

| administered | 3172.876 | 36.214 | 11376000 | |

| Annual number of HPV dose | Consumed | 863.638 | 0 | 2930526 |

| administered | 827.944 | 0 | 2784000 | |

| Annual number of IPV dose | Consumed | 1190.899 | 13.412 | 4213333 |

| administered | 1080.483 | 12.071 | 3792000 | |

| Annual number of Measles dose | Consumed | 3245.692 | 37.142 | 11667692 |

| administered | 2150.412 | 24.142 | 7584000 | |

| Annual number of PCV-13 dose | Consumed | 3534.671 | 40.237 | 12640000 |

| administered | 3172.876 | 17 | 11376000 | |

| Annual number of Rota_Liq dose | Consumed | 2232.424 | 25.413 | 7983158 |

| administered | 2150.412 | 24.142 | 7584000 | |

| Annual number of Td dose | Consumed | 3830.4 | 42.784 | 13440000 |

| administered | 3429.77 | 24 | 12096000 |

References

- WHO. Immunization Agenda 2030: A global strategy to leave no one behind; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FMOH, Ethiopia National Expanded Programme on Immunization Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2016 - 2020 MCH, Editor. 2015: Addis Ababa. p. 104.

- Lindstrand A, Cherian T, Chang-Blanc D, Feikin D, O’Brien KL. The world of immunization: achievements, challenges, and strategic vision for the next decade. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 224 (Suppl. S4), S452-S467.

- World Health Organization. Vaccine stock management: guidelines on stock records for immunization programme and vaccines store managers. World Health Organization; 2006.

- CSIS. Minding the Gap in Global Immunization Coverage. 2021; Available from: https://www.csis.org/analysis/minding-gap-global-immunization-coverage.

- ICF, E.P.H.I.E.E.a. , Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report., CSA, Editor. 2021, EPHI and ICF.: Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- Bangura, J.B. , et al., Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyisa, D. , et al., Adherence to WHO vaccine storage codes and vaccine cold chain management practices at primary healthcare facilities in Dalocha District of Silt’e Zone, Ethiopia. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 2022, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momose, H. , et al., A new method for the evaluation of vaccine safety based on comprehensive gene expression analysis. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010, 2010, 361841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argaw, M.D. , et al. , Immunization data quality and decision making in pertussis outbreak management in southern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Arch Public Health 2022, 80, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi FA, A.D. , Crepaldi NY, Yamada DB, Lima VC, Lopes Rijo RPC, Data Quality in health research: a systematic literature review. medRxiv 2022. [Internet]. 2022 Jan 1;2022.05.31.22275804.

- WHO, World Health Organization Vaccination Coverage Cluster Surveys: Reference Manual. (WHO/IVB/18.09). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO, 2018.

- Akoh W, Ateudjieu J, Nouetchognou J, Yakum M, Nembot F, Sonkeng S, et al. The expanded program on immunization service delivery in the Dschang health district, west region of Cameroon: a cross sectional survey. BMC public health 2016, 16, 801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ateudjieu J, Kenfack B, Nkontchou BW, Demanou M. Program on immunization and cold chain monitoring: the status in eight health districts in Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2013, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garabadu S, Panda M, Ranjan S, Nanda S. Assessment of vaccine storage practices in 2 districts of Eastern India -using global assessment tool. Int J Health Clin Res. 2020, 3, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Victor Sule, Vaccine Management Knowledge and Practice of Health workers in Yemen, 29 Dec 2022-Texila International Journal of Public Health.

- Adewole et al. Comparative Study on Drivers and Barriers of Vaccine Stock Management Practices Among Healthcare Workers in Northwestern State, Nigeria, 2023).

- FMOH, Ethiopia National Expanded Program On Immunization, Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan (2021-2025).

| Variables | Central | Sub-Central | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of expired vials in the cold/freezer rooms | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Facility has stock records for each vaccine on the vaccination schedule | 1 | 14 | 15 | |

| Stock record completeness | 1 | 14 | 15 | |

| Facility has diluent stock records | 1 | 11 | 12 | |

| Well organized vaccine stock records | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| Vaccine stock records stored in a secure place | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Number of physical stock counts made in last 12 months | 12 Times | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| 11 Times | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9 Times | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 Times | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| 3 Times | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 time | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Variable | Health Institution type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Center | Health Post | Hospital | WorHO | Total | ||

| Stock management system show vaccine needs per receiving store | Yes | 22 (59) | 21(70) | 4(67) | 19(76) | 66(67) |

| Stock management system show the quantities distributed against those allocated per supply period for each receiving store | Yes | 21(93) | 20(95) | 3(75) | 16(84) | 60(91) |

| Complete distribution and allocation records | Yes | 20(91) | 20(95) | 3(75) | 13(68) | 56(85) |

| Stock management system show vaccine stock levels are between the established minimum and maximum | Yes | 42 (69) | 38(73) | 4(57) | 32(55) | 116(65) |

| Variable | Health Institution type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Center n(%) |

Health Post n(%) |

Hospital n(%) |

WorHO n(%) |

Total n(%) |

||

| Vaccine stock records well organized | Yes | 41(67) | 36(72) | 2(27) | 40(68) | 119(67) |

| Stock management system show if vaccine stock levels are between minimum and maximum | Yes | 42 (69) | 38(73) | 4(57) | 322(55) | 116 (65) |

| Stock records complete | Yes | 62 (81.8) | 4(100) | 5(100) | 53(90) | 124(86) |

| Presence of diluent stock records | Yes | 67 (88.2) | 3(75 | 5(100) | 52(88) | 127(88) |

| Vaccine stock records stored in a secure place | Yes | 33 (68.7) | 30(77) | 3(43) | 37(70) | 103(70) |

| How often are the distribution and allocation records updated? | Annually | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(2) |

| Bi-annual. | 1(5) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(2) | |

| Daily | 3(14) | 1(5) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 4(6) | |

| Monthly | 15(68) | 19(90) | 4(100) | 16(84) | 54(82) | |

| Quarterly | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(5) | 1(2) | |

| Weekly | 2(9) | 1(5) | 0(0) | 2(11) | 5(8) | |

| Total | 22 | 21 | 4 | 19 | 66 | |

| Health Institution type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health centre n(%) |

Health Post n(%) |

Hospital n (%) |

WorHO n(%) |

Total n(%) |

||

| Vaccine stocks arranged by vaccine type | Yes | 73(73) | 25(46) | 10(83) | 60(82) | 168(70) |

| Vaccine stocks arranged by lot and expiry date | Yes | 61(61) | 16(29) | 10(83) | 52(72) | 139(58) |

| Vaccine storage emergencies in the last 12 month | Yes | 13(13) | 8(10) | 0(0) | 7(8) | 28(10) |

| Appropriate actions taken during the most recent vaccine storage emergency | Yes | 11(85) | 7(88) | NA | 7(100) | 25(89) |

| WorHO=Woreda Health Office, NA: Not Applicable | ||||||

| Health Institution type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | HP | Hosp. | WorHO | Total | |||

| Collect vaccines from a supplying store | Yes | 44(44) | 31(37) | 4(33) | 40(44) | 119(42) | |

| Road vehicles used to collect, distribute vaccines or to provide | Yes | 20 (20) | 1(1) | 3(25) | 37(41) | 61(21) | |

| Access road in good condition | Yes | 14 (70) | 1(100) | 2(67) | 28(76) | 45(74) | |

| Road can be used year-round | Yes | 13(65) | 1(100) | 3(100) | 26(70) | 43(71) | |

| HC= HP Hosp. WorHO | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).