1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The SARS-CoV-2 virus (COVID-19), which started in Wuhan, China, in January 2020,[

1,

2,

3] spread to world, including Nigeria, which recorded its first case on February 27, 2020.[

4]

According to the Nigerian Centers for Disease Control (NCDC), as of April 24, 2022, Nigeria had 2,653 active cases of COVID-19 and 3,143 fatalities.[

5] However, there is evidence of a gradual decline in the outbreak owing to the response from the Nigerian healthcare system. The COVID-19 program in Nigeria was developed using various measures, such as a robust response framework, emergency operation centers (EOCs), and increased vaccination.[

6] These steps, along with other active precautionary measures (such as non-pharmacological interventions) were instrumental in attaining epidemiological control.[

1,

7,

8]

However, in the early phases of the pandemic, most governments, including Nigeria’s, instituted standard epidemic control measures: travel restrictions, lockdowns, workplace hazard controls, closure of public spaces and facilities, and strict hygiene practices.[

9] Although these measures helped limit the spread of the infection, they also interrupted implementation of crucial primary healthcare (PHC) programs, further exacerbating the prevailing healthcare system weaknesses and community distrust.[

10] The following factors jointly culminated in the far-reaching effects on the overall PHC landscape in Nigeria:[

11]

1.1.1. Service delivery (SD)

Providing vaccinations and improving coverage are the fundamental concepts of SD in routine immunization (RI) programs.[

12,

13] A COVID-19 study conducted in 170 countries and territories found that disrupted RI sessions occurred in 17 of 30/47 World Health Organization (WHO) member states in Africa. There was a partial suspension of fixed-post immunization services in two countries, and partial or complete suspension of outreach services in 17 countries.[

14] The inability to conduct immunization practices during COVID-19 was the greatest threat to the gains in vaccine-preventable diseases.[

14,

15,

16,

17]. According to GAVI, WHO, and UNICEF at least 80 million children are at risk of diphtheria, measles, and polio because of the disruption in routine vaccination efforts caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[

17,

18]

1.1.1. Leadership and governance (L&G)

L&G is pivotal to the success of RI programs.[

19] Studies have shown that since the COVID-19 pandemic, government discussions on RI activities have decreased.[

20,

21] The weak healthcare systems in developing nations made other healthcare intervention programs vulnerable, as most governments’ attention shifted toward curtailing the direct health and economic impact of COVID-19.[

22]

1.1.2. Monitoring and evaluation (M&E)/Supportive supervision (SS)

A study on the impact of COVID-19 on integrated SS in 19 countries in east and south Africa showed that 13 countries had different levels of decline in integrated SS visits in 2020 compared to 2019. Ten of the 13 countries had over 59% decrease; there was a significant reduction in integrated SS in 11 countries.[

23] Studies have reported a significant association between increased SS and improved immunization coverage.[

24,

25,

26] The complexities and uncertainties associated with the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the concepts and methodologies of M&E practices.[

27] The difficulty in the healthcare system to switch from a manual M&E approach to the use of e-tools was a significant factor in determining vaccine coverage during the pandemic.[

28]

1.1.3. Vaccine supply chain (VSC)

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a massive disruption in the global supply chains, which significantly affected the supply of essential drugs and commodities.[

29] The pandemic caused temporary and prolonged closure of healthcare facilities, which led to stockouts of vaccines and other supplies.[

30,

31] According to Shet

et al.,[

14] there was a 33% global reduction in the administration of the third dose of Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus (DPT)containing the vaccine, with reductions ranging from 57% in Southeast Asia to 9% in the WHO African regions.

1.1.4. Community engagement (CE)

UNICEF acknowledges the possibility that local COVID-19 response measures could have temporarily interrupted RI services, CE, and demand generation.[

32] At one point, to reduce the worsening community transmission of COVID-19, WHO recommended the suspension of mass vaccination campaigns.[

33,

34] The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), UNICEF, and WHO recognize that risk communication and enlightenment during a pandemic are important in enhancing continued CE and RI demand generation.[

35] A recent publication on the impact of COVID-19 on immunization programs in Kaduna State, Nigeria, noted that risk communication, enlightenment, and trust were important factors that affected RI programs.[

36]

1.1.5. Health financing and management (HFM)

The sudden onset of the pandemic disrupted the manual approach to finance management, which caused a transition to digital approaches.[

37] At a medical conference in Nigeria, it was reported that the national allocation for RI grew from 17 billion to 139 billion naira between 2018 and 2021.[

38] However, it may not be possible to state that such increments occurred at the state and local government levels.[

38,

39] There is a paucity of information to determine the utilization and management of funds at different implementation levels.

1.2. Study rationale

Although the COVID-19 pandemic potentially derailed and stifled the progress of PHC, particularly RI programs, it also provided a unique opportunity to garner system resilience, including increased attention from the government and international organizations; a surge in health financing and management; prompt agreement to health demands; and an increase in the number of facility equipment and machines, molecular laboratories, and bed spaces in hospitals.

However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, these achievements across all program themes were threatened. A major implication of these restrictive measures and the overwhelming increase in COVID-19 cases included the disruption in the provision of essential healthcare services.[

15,

21,

30], and extra burden on frontline healthcare workers, diagnostic capacities, and management of facilities.[

21] Beyond these disruptions, the pandemic also revealed weaknesses in the healthcare systems and challenged programmatic assumptions.

Most previous studies evaluated the effect of COVID-19 on the healthcare system as a whole.[

14,

15,

20,

21,

30,

40,

41] However, from our perspective, we believe that RI program activities did not experience the same level of disruption due to the pandemic. We posit that the impact of COVID-19 on RI programs varied, with some programs being more resilient and less affected. Others programs may have been directly related to SD, and therefore, impacted SD more. The findings from such evaluations will provide the basis for scaling up or pivoting for adaptation and improvement in existing structures.

1.3. Objectives

The study objectives were as follows (See

Appendix A for the research questions of the stated objectives):

To determine the effects of the pandemic on RI programs, focusing on L&G, M&E (SS), CE, VSC, HFM, and SD in six Northern Nigerian states.

To explore the perception of key stakeholders at different implementation levels (state, local government areas (LGAs), healthcare facilities (HFs), and community) on the impact of COVID-19 on RI systems and services in six Northern Nigerian states.

To discuss the implications of the findings on RI and PHC program policies and implementation.

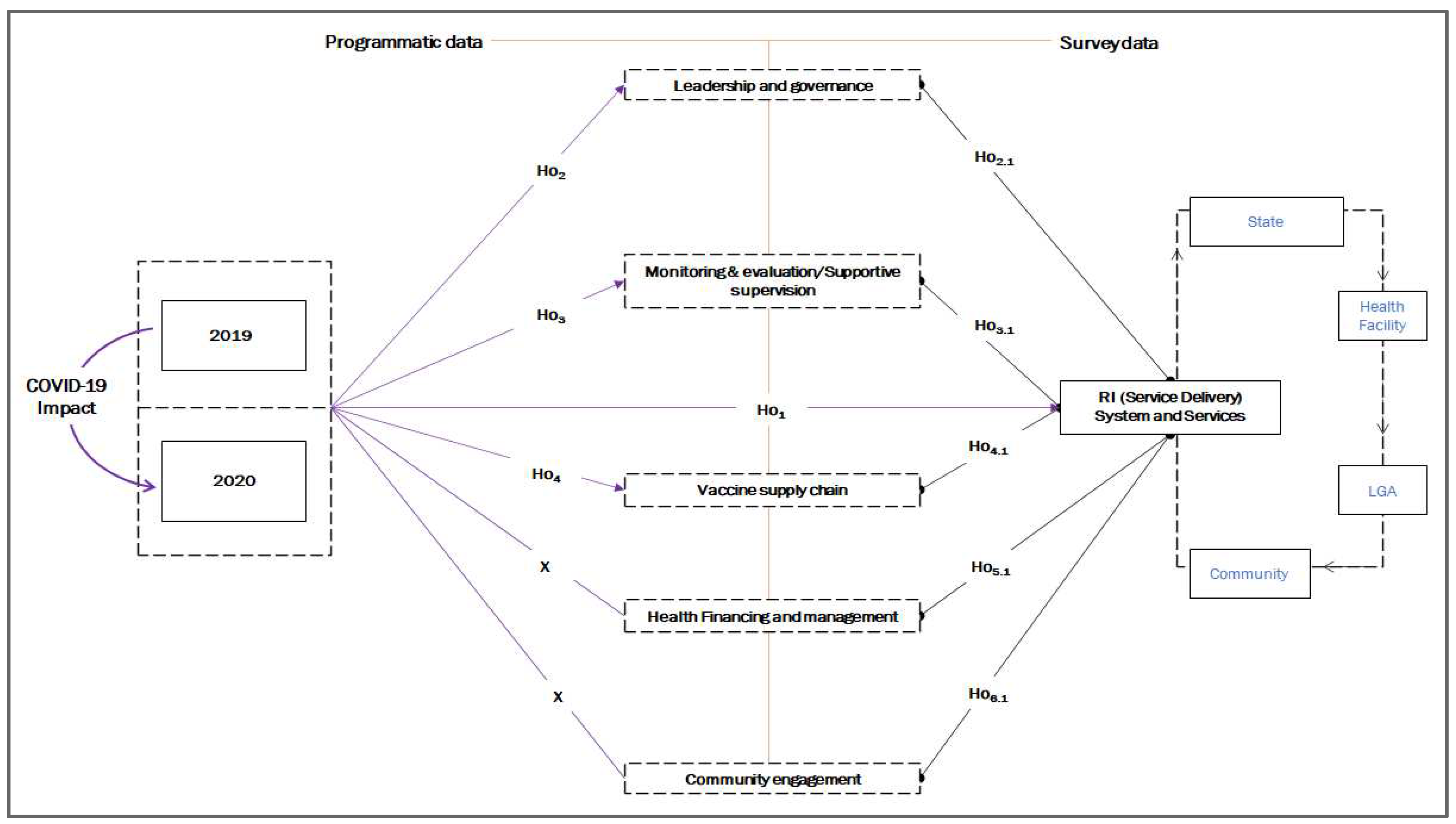

1.4. Analysis framework and research hypothesis

Based on the theoretical perspectives and empirical evidences,[

12,

14,

15,

16,

20,

21,

24,

25,

26,

31,

32,

35,

38,

39] a conceptual framework (Fig. 1) was designed to comparatively analyze the RI program’s (CE, M&E, VSC, HFM, L&G, and SD) performance between 2019 and 2020 as measures of healthcare system resilience, and to evaluate the relationships between the impact of COVID-19 on RI programs using both programmatic and survey data.

Based on the conceptual framework in

Figure 1, we hypothesized that transitioning from 2019 to 2020 (the peak year of the pandemic in terms of number of cases and mortality), RI systems, and services were impacted. However, the impact was felt through various key aspects of the program. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

1.5. Programmatic themes

Ho1: There was a change in SD due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ho2: COVID-19 affected different L&G activities.

Ho3: M&E (SS) was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ho4: COVID-19 affected VSC.

Additionally, we hypothesized a perceived causal effect of the impact of COVID-19 RI programs on SD.

1.6. Survey themes

Ho2.1: The impact of COVID-19 on L&G directly affected RI SD.

Ho3.1: The impact of COVID-19 on M&E (SS) directly affected RI SD.

Ho5.1: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on VSC directly affected RI SD.

Ho6.1: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HFM systems directly affected RI SD.

Ho2.1: The impact of COVID-19 on CE directly affected RI SD.

For the structural equation model (SEM) framework, the exogenous variables included CE, M&E, VSC, HFM, and L&G, while the endogenous variable was SD. The control variables were state, work, and job experience (see Fig. S2 for a graphical presentation of the frameworks).

2. Materials and Methods

This study involved mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) approaches to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic affected RI programs in six states in Northern Nigeria. This study highlighted the systemic strengths and gaps that require optimization as a national effort to build more resilient and functional healthcare programs.

2.1. Study setting

The study focused on six Nigerian states: Bauchi, Borno, Yobe, Kaduna, Kano, and Sokoto (See Fig. S1).[

42] The majority of the population is rural, with scattered settlements, although the states have some urban centers. Most of the population depends on PHC facilities for healthcare services.

The six states were part of the Northern Nigeria Routine Immunization Strengthening Program, in which the state government partnered with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), the Aliko Dangote Foundation (ADF), and in some states, USAID, Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), UNICEF, Global Fund, and Global Affairs Canada. The program aimed to strengthen the PHC system through a basket-funding mechanism, and was first introduced in Kano (2013) and Bauchi (2014), followed by the other four states (2015). The intervention established strong L&G structures, provided technical assistance, and ensured effective oversight and accountability by coordinating structures.

2.2. Study sampling

2.2.1. Sample size

For evaluations at the healthcare facility and local government levels, we employed a sample size estimating formula for a proportion of a finite population by Sharma et al. (2019), since the population is static.

Where m = sample size,[

43,

44] n = correcting for the sample size (m) as a finite population, p

(L) = indicator percentage (proportion of HFs conducting RI out of all HCF in the respective states), z = Z-value (1.96), e = relative error margin (10% = 0.01), design effect = 1.15.

To obtain a realistic sample size, the proportion of accessible communities was factored into the calculations based on difficult terrains and security-compromised areas. The study arrived at a total sample size (m) of 267 [Bauchi (n=37), Borno (n=23), Kaduna (n=54), Kano (n=50), Sokoto (n=47), and Yobe (n=56)].

2.2.2. Sampling technique:

We used both multistage stratified randomized and non-randomized (convenient) sampling techniques, depending on the implementation levels and research approach (qualitative or quantitative). At the state and LGA levels, we conveniently sampled all officers in-charge because they were fixed; however, at health facilities (HFs), we utilized stratified multistage random sampling. We stratified state HFs based on their location within the LGA classification (rural, rural-urban, and urban).[

45,

46]

2.2.3. Selection criteria

Only those within the selected areas who provided informed consent were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were those who did not meet the inclusion criteria.

2.3. Instrument design

The instrument used for quantitative data collection was part of the routine M&E tools for project implementation. The quantitative and qualitative data were obtained using questionnaire surveys and key informants (KIIs). The tool was designed in line with the USAID and UNICEF survey for different aspects of healthcare systems.[

47,

48,

49]

2.3.1. Validity

To ensure instrument localization and adaptability, we considered phase and content validity. We achieved validations through constructive engagements and feedback from healthcare professionals across different institutions.

2.3.2. Reliability

We tested the reliability of the instrument using two approaches: (1) to determine the internal consistency of the questionnaire, in the absence of a complex multidimensional structure, we conducted Cronbach’s alpha analysis (α) [

50,

51] and achieved α-values of 0.814, 0.783, and 0.823 for the questionnaire for the state, LGA, and HF, respectively; and (2) to measure the external consistency of the instrument measurement over time, we used a test-retest method (Pearson’s product moment) [

52,

53] and obtained an

r-value of 0.784.

2.4. Data Sources and variables

Research on evaluation design often requires a combination of data types from different sources; therefore, we obtained both primary and secondary data from multiple sources. This aligns with the recommendation of the Measure Evaluation Manual Series No. 3 by the USAID.[

49]

2.4.1. Secondary (programmatic) data

This included data from administrative sources (DHIS 2), along with CE reports, routine immunization support supervision (RISS) reports, LGA review meeting reports, working group minutes of meetings, and RI or PHC work plans.

2.4.2. Primary (survey) data

We conducted cross-sectional surveys using Likert-scale questionnaires and KIIs to further derive insights from RI programs during the pandemic. We interviewed stakeholders at the state, LGA, and HFs levels to obtain information about the impact of the pandemic on various RI programs and the and the challenges during the pandemic.

2.4.3. Variables

The data variables obtained from the different data sources included Service delivery (SD), Leadership and governance (L&G), Monitoring and evaluation (M&E)/Supportive supervision (SS), Vaccine supply chain (VSC), Community engagement (CE), and Health financing and management (HFM).

2.5. Data management and analysis

2.5.1. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS Amos ver. 28 (IBM, USA), with the confidence level set at 95%, and P-value less than 0.05 considered significant.

The KMO test showed that the data obtained from the survey were well-suited for factor analysis (KMO=0.95, P<0.001). Values closer to 1 indicated a good fit (

Table S2). For the validity test, we performed principal component analysis and confirmatory factor analysis to establish the significance of the data. Among the measurement items, 24 variables were identified in four components (C1-4). The four components cumulatively explained 73.15% of the variance (

Table S3), as shown in the scree plot in Fig. S3, which confirmed that only four components were important to the model (eigenvalue not less than 1). Three variables with less than 0.5 loading values were removed from the study [two in SD (SD2, SD3) and one in L&G (L&G1)]. Thus, only 21 variables were included in this model.

The confirmatory factor analysis results provided evidence of the discriminant validity of the theoretical constructs.[

54] For the path analysis of the survey data using SEM, the fit indices indicated a satisfactory model fit (GFI = 0.884, CFI = 0.961, RMR = 0.054 and RMSEA = 0.062).[

55,

56,

57,

58,

59] However, the chi-square analysis of model fit produced a significant value (chi-square

[df=154] = 339.615,

P<0.001), which implies a non-model fit. Nevertheless, scientists do not rely much on the chi-square test as a useful metric for model fit.[

60,

61]

All variables in the model were statistically significant at a 0.05 level, with standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.537 to 0.860, with reliability (Cronbach’s α) between 0.742 and 0.892 (

Table S4; refer to Fig. S4 for the diagrammatic representation of the factor loading in

Table S4). This implies that the proposed structure for measuring the perceived impact of COVID-19 on RI SD can be achieved using the four components of L&G, M&E, VSC, CE, and HFM.

2.5.2. Thematic analysis

We coded the open-ended comments using the grounded theory approach for thematic analyses,[

62,

63] which involved the use of two research team members to form concepts from the data and independently identifying several themes. The researchers agreed upon the themes and coded open-ended comments for each theme. We evaluated each comment using the constant comparative method of grounded theory.[

62,

64]

3. Results

The analysis to test the hypotheses described a two-way relationship. The first part was approached using an independent t-test analysis of the differences in the programmatic data for thematic areas pre- (2019) and post-COVID-19 (2020). The second part evaluated the relationship between thematic areas from the survey data using path model analysis.

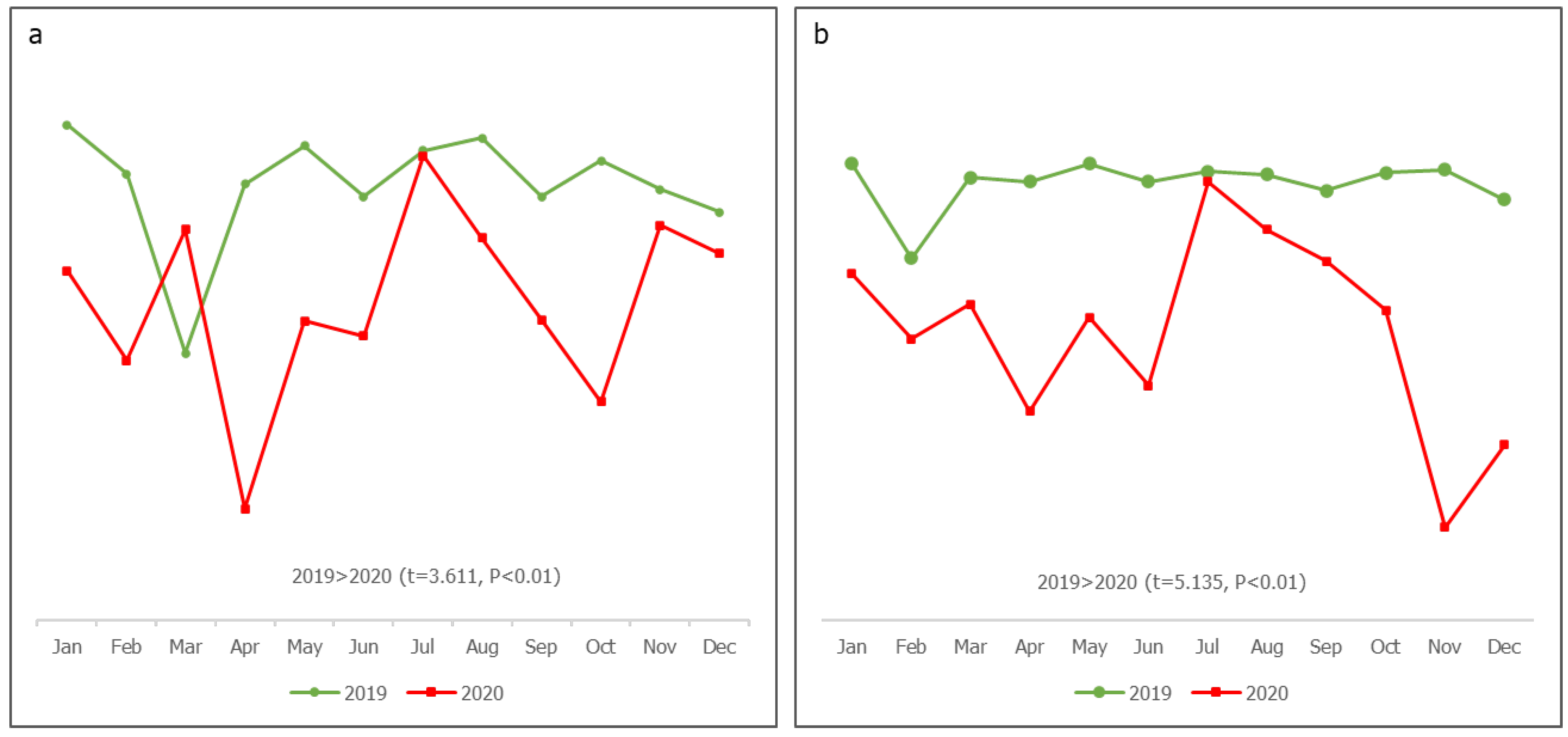

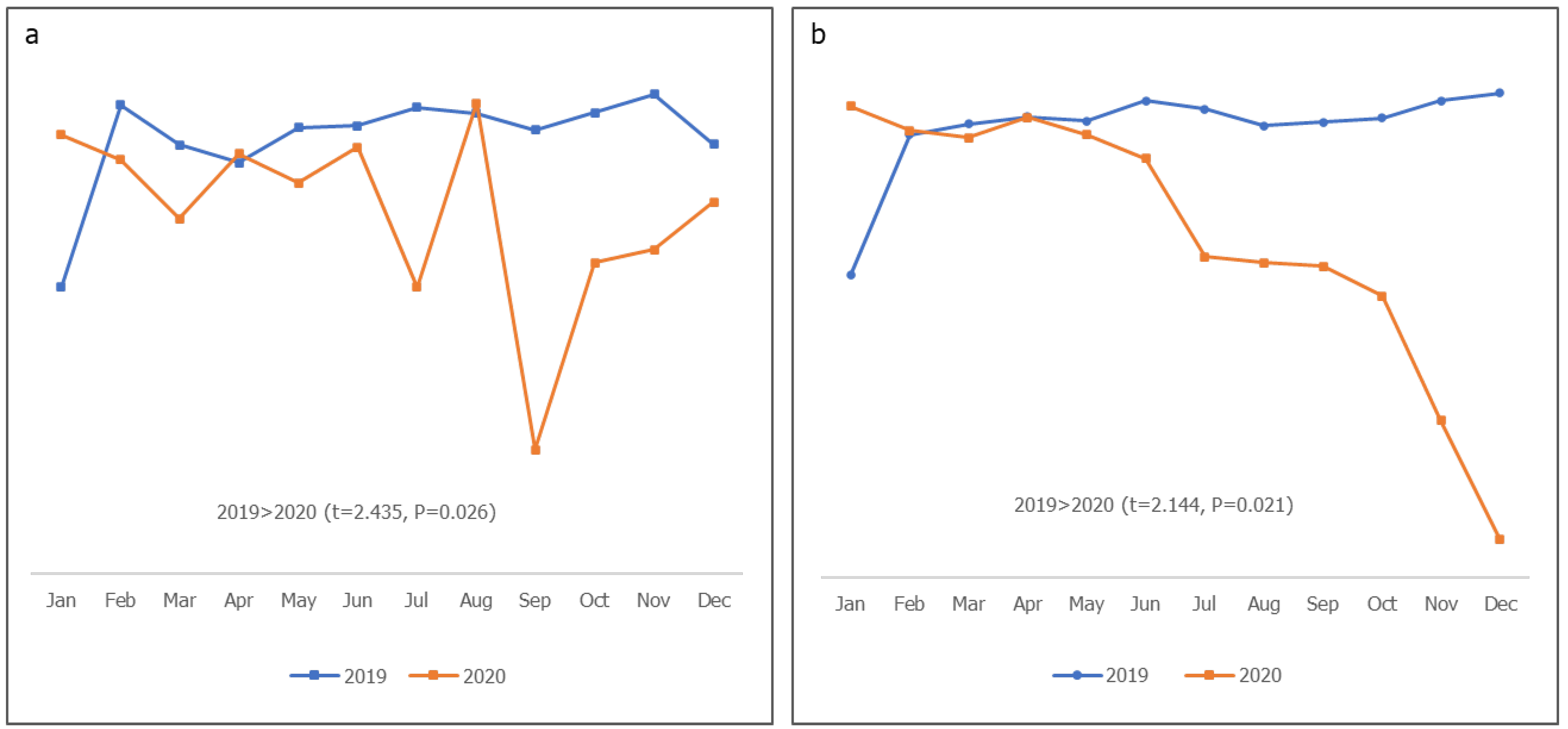

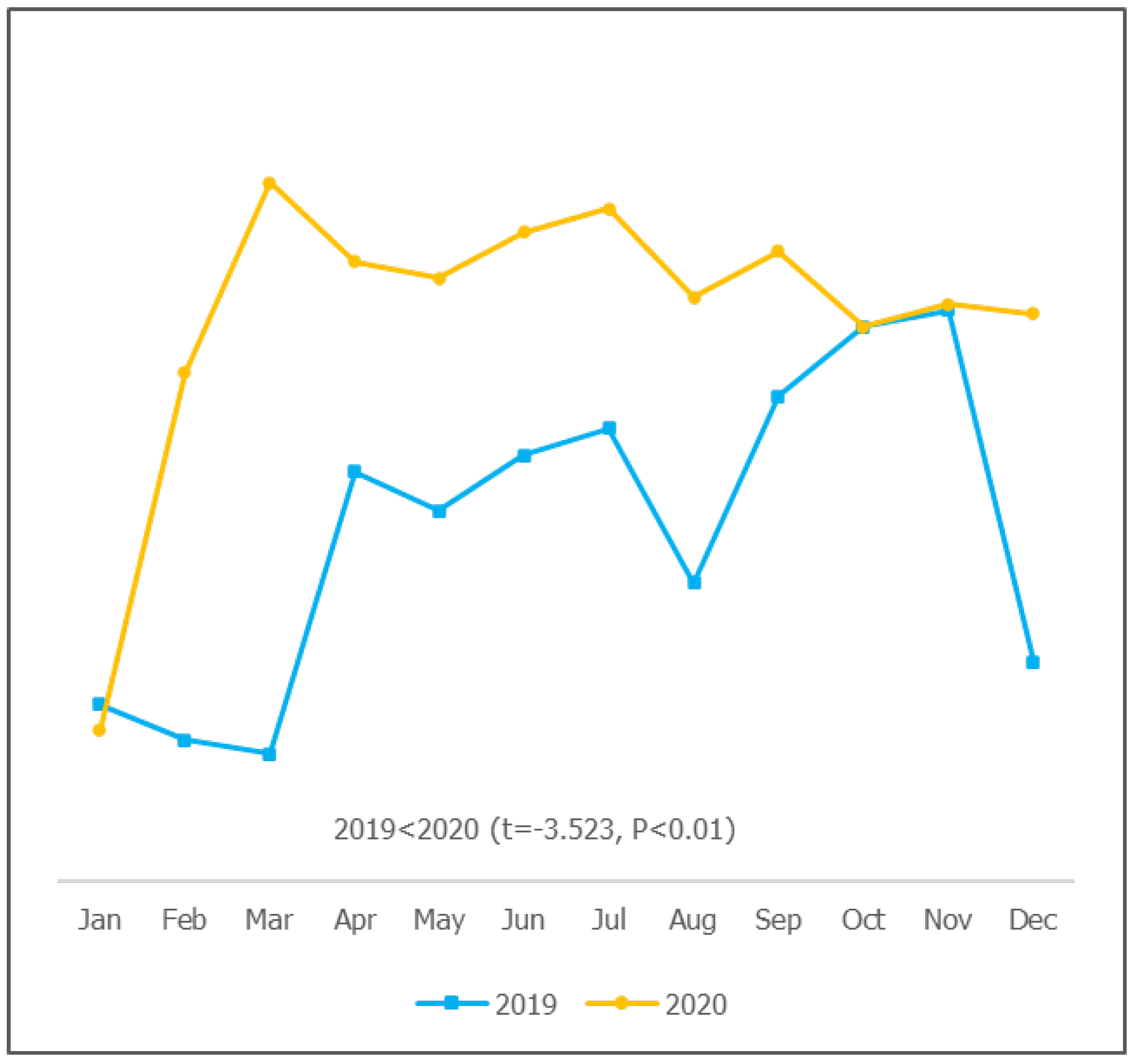

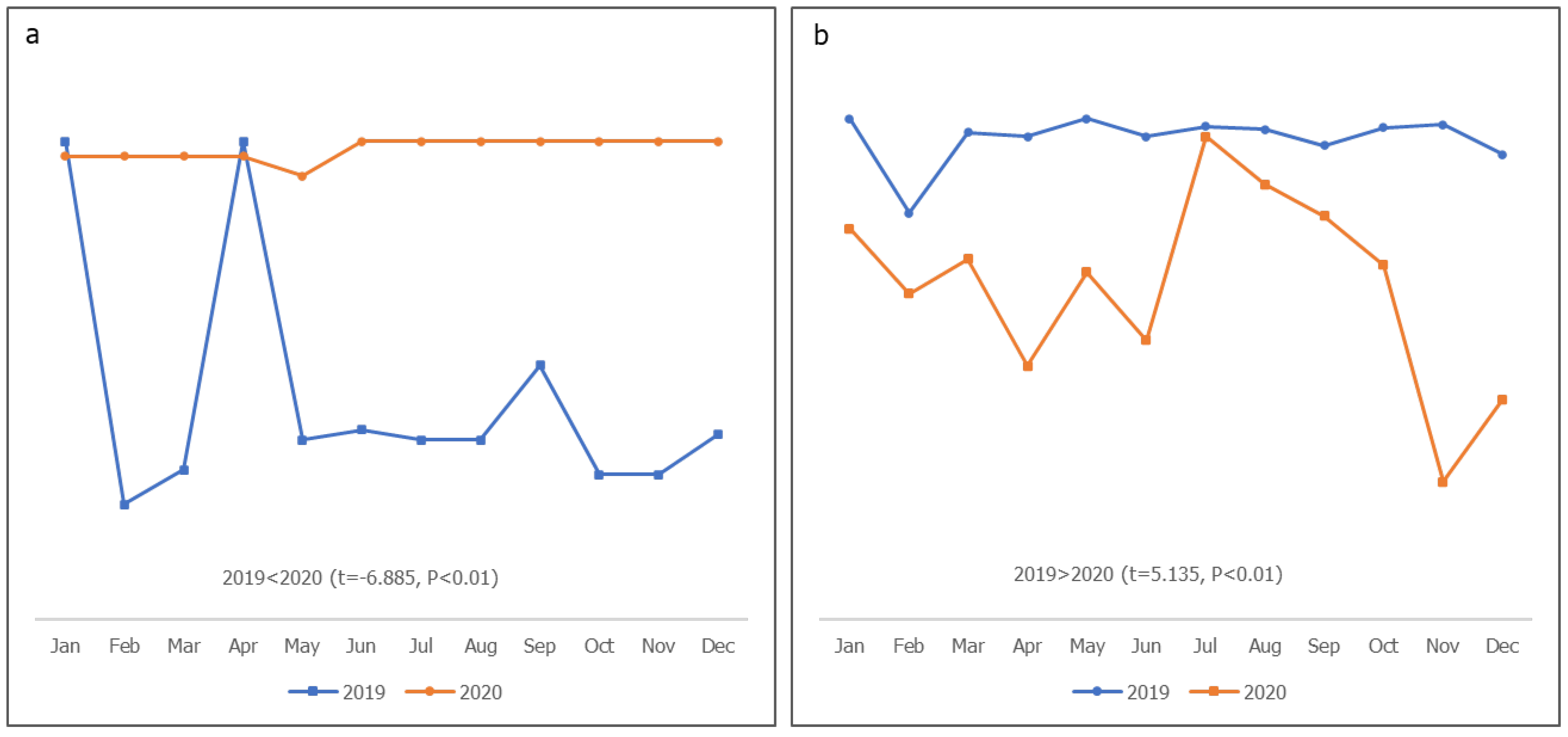

The results of the independent t-test analysis of the programmatic data in

Table 1 and

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show that there were significant changes in the proportion of indicators for the different thematic areas across the states and the general program. A graphical description of the path analysis is shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

3.1. Programmatic data analysis

Meetings significantly decreased in 2020 than in 2019 in Bauchi (P<0.01), Sokoto (P<0.01), and Yobe (P<0.05), whereas the changes in Borno, Kaduna, and Kano were not significant (P>0.05). The changes in the action point completion rate were not significant in Bauchi, Borno, Kaduna, and Kano, but were significantly lower in Sokoto (P<0.01) and Yobe (P<0.05) in 2020 than in 2019. The proportion of planned fixed sessions conducted was lower in 2019 than in 2020 in Bauchi, Kano, Sokoto, and Yobe (P<0.05), whereas the proportion of planned outreach sessions conducted in 2019 significantly decreased in 2020 in Bauchi, Sokoto, Yobe (P<0.05), Borno, and Kano (P<0.01). Planned RISS visits conducted (LGA to HF) in 2019 and 2020 did not significantly change in Borno, Kaduna, and Sokoto (P>0.05); however, in Bauchi, Kano (P<0.01), and Yobe (P<0.05), there was a significant increase in 2020 compared to 2019. All six states showed a significant increase in the timely distribution of vaccines to their apex facilities in 2020 compared to 2019 (P<0.01). Vaccine stockouts in Borno, Sokoto, and Yobe were significantly greater in 2019 than in 2020 (P<0.01).

As shown in

Figure 2, the planned fixed and outreach sessions in 2019 were steady, between 107% and 98%, compared to 2020, which had higher fluctuations with lower values. There were significantly more planned fixed and outreach sessions in 2019 (P<0.01). As shown in

Figure 3, the proportion of working group (WG) meetings conducted and action points completed in 2019 were more progressive and stable than in 2020, in which a significant fluctuation in WG meetings was observed (P=0.026); there was also a rapid drop in action point completion in 2020 (P=0.021). There were significantly more M&E activities involving visits to HFs in 2020 than in 2019 (P<0.01). Although declines were observed in 2019, the activities in 2020 experienced steeper fluctuations (Fig. 3). As shown in

Figure 5, the vaccine supply to facilities in 2020 was significantly steadier than it was in 2019, with more than 98% timely receipt of supply (P<0.01). There was a significantly higher stockout in 2019 than in 2020 (P<0.01).

3.2. Survey data analysis

The survey data analysis showed that 256 (95.9%) respondents had a tertiary educational qualification. The mean work experience of the respondents was 17.34±8.32 years, and most of them had more than 16 years of work experience (191/267; 71.5%). Most of the respondents had spent less than five years at their current job (139; 52.1%), with a mean of 7.67±6.61 years of experience (

Table 2).

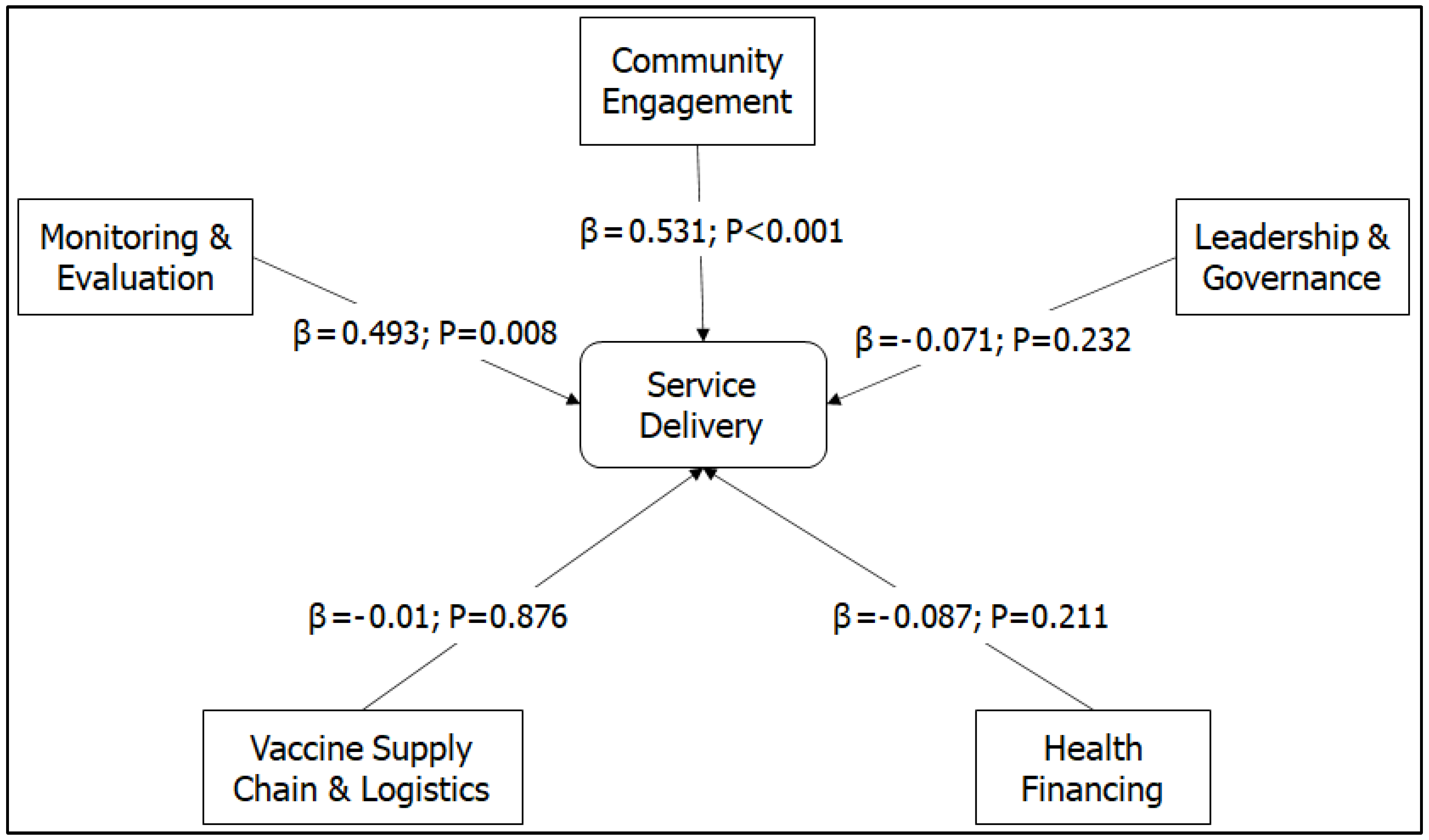

The SEM path analysis showed a direct relationship between the changes in SD, CE (β=0.53; P<0.001), and M&E (β=0.49; P=0.008) during the COVID-19 pandemic. VSCL was an independent factor for SD resilience. L&G and HF were negative factors for SD resilience, although the effects did not significantly influence SD (

Figure 6).

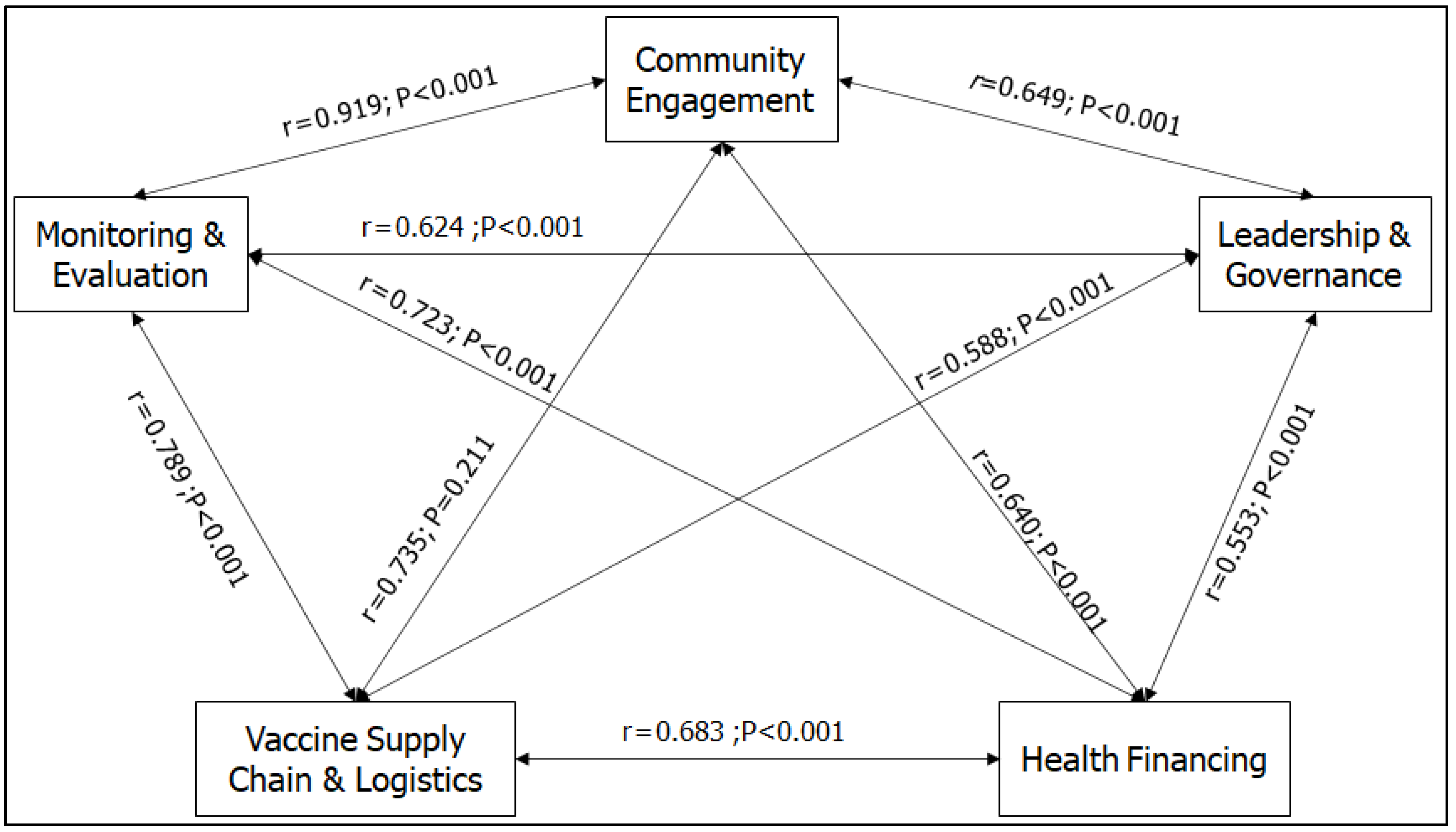

Figure 7 presents the correlation between the thematic areas. The results showed that all the predictor variables were significantly positively correlated (P<0.001). The impact of COVID-19 on one RI program was positively related to its impact on other programs, though at different levels.

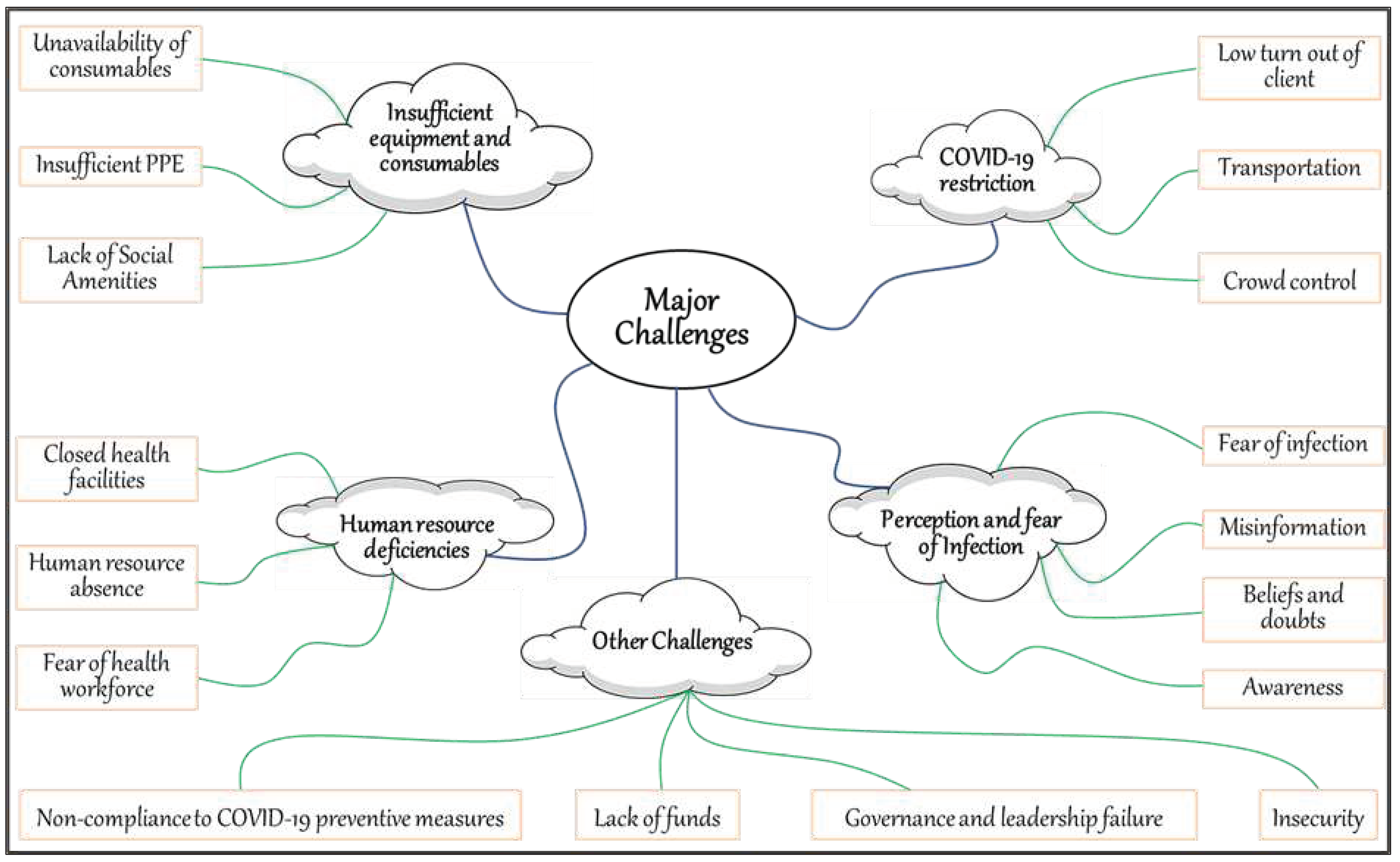

From the thematic analysis and word mapping shown in

Figure 8, we identified four major challenges with RI program activities during COVID-19: insufficient equipment and consumables, restriction of movement, human resource scarcity, and perception and fear of infection. Other challenges included non-compliance with protective measures against COVID-19, reduced funding, leadership failure, and insecurity.

4. Discussion

One of the most discussed aspects of RI and healthcare systems has been resilience and preparedness during pandemics.[

40,

41,

65] Vaccination during a pandemic remains a subject of debate in developing countries. The argument is whether the provision of RI services during COVID-19 was beneficial or detrimental.[

33,

40,

66] However, stopping vaccination can cause up to 700,000 deaths in children.[

40]

In Nigeria, the government implemented various epidemic control measures, which included, travel restrictions, lockdowns, workplace hazard controls, closure of public spaces and facilities, and sanitization;[

9] these directly or indirectly affected RI programs and associated services.[

29,

31,

36,

38,

39]

This study described the impact of the pandemic on various RI programs and how it affected SD from both the programmatic and survey perspectives. The study highlighted the changes in programmatic data regarding RI services in pre- and post-pandemic periods, and also showed how the perceived changes in RI programs during the peak of COVID-19 affected RI SD.

Providing vaccination services is an indicator that measures RI SD,[

12,

13] which is hinged on various RI programs, such as strong L&G structures,[

19] M&E (SS),[

24,

25,

26,

27] VSCL, [

30,

31] CE,[

33,

34,

36] and HFM.[

38,

39] However, the impact of COVID-19 on these RI programs may not have had a converging effect on RI SD because of differences in the program administration.

Although L&G plays a crucial role in RI programs,[

19] the focus shifted to controlling the spread of the virus during the pandemic.[

20,

21] More resources were redirected toward COVID-19 activities.[

67] Programmatically, owing to restrictions on physical meetings and the unavailability of key stakeholders in Bauchi, Sokoto, and Yobe, the coordination and completion rates of action points were affected. The shift to virtual meetings allowed for continued coordination, but existing weaknesses in L&G and HFM were exacerbated.[

68] These issues had a limited direct impact on RI SD during the pandemic.

CE, and M&E are essential for successful RI SD because they are the key drivers of demand generation,[

36,

69,

70] and program improvement,[

24,

25,

26] respectively. During the pandemic, CE was hindered by the lockdown restrictions and vaccine hesitancy. However, SS was optimized through improved monitoring techniques and an increased frequency of supervisory visits. The programmatic data showed improvement in this area, while the survey data indicated that the impact of COVID-19 on CE and SS directly affected SD during the pandemic. This highlights the significance of the role of healthcare workers in RI programs at the HF level as they are responsible for CE and M&E (SS).

VSCL is a vital component of vaccination programs that operates using a multi-structural approach linked to good L&G and HFM.[

71,

72] The State Primary Health Care Board (SPHCB) teams initially used vaccine delivery systems to distribute essential PPE and later added COVID-19 vaccines. The effective RI-COVID integration showed the potential of PHC programs. Stockout rates improved owing to low demand, which was strongly associated with fears, restrictions, and lack of information on the part of RI service users. The study found that SD activities were not influenced by VSCL, likely because VSCL activities are coordinated by subnational governments[

28,

73] and not by RI service providers at HFs. The study observed resilience in VSCL, with on-time delivery of vaccines to endpoints, sustaining program coverage, and preventing vaccine preventable disease (VPD) outbreaks. The direct-to-facility delivery model operated by states eliminated the need for HF to pick up vaccines,[

74] allowing them to focus on SD with minimal disruptions to the VSCL.

Program SD across MoU states was notably affected by disruptions in the conduct of outreach and fixed sessions. These disruptions were due to lock-down measures limiting the movement of healthcare workers and clients, unavailability of protective gear leading to the closure of some facilities, and fear among healthcare workers. Immunization intensification efforts[

75] post-lockdown, such as the state-led Periodic Intensification of Routine Immunization (PIRI), were crucial to ensure recovery of lost ground and overall improved session conduct. The results of this study showed that the impact of the pandemic on L&G, HFM, and VSCL was indirectly related to SD, although the effect was not significant. The impact of the pandemic on CE, and M&E during COVID-19 was directly and strongly related to the impact of COVID-19 on SD, whereas VSCL was an independent factor for SD.

The perceived impact of COVID-19 on RI programs was unidirectional and significantly related. As previously reported, COVID-19 significantly affected RI program activities across all thematic areas.[

17,

20,

21,

22,

28,

33,

37,

68] However, the effect was stronger in some areas compared to others; L&G, HFM, and VSCL were the least affected by COVID-19 compared to M&E, CE, and SD. This suggests that the pandemic had the most negative effect on activities at the health facility level, whereas those at the subnational level were less affected.

The study identified four major challenges associated with RI program activities during the COVID-19 pandemic: insufficient equipment and consumables, restriction of movement, human resource scarcity, and perception and fear of infection. Other challenges included non-compliance with protective measures against COVID-19, reduced funding, leadership failure, and insecurity. Studies have shown that global challenges have been observed during the pandemic.[

21,

22,

76,

77] However, in Nigeria, there were more frequent reports of unavailability of consumables across HFs such as personal protective equipment (PPEs).[

39,

78] This was associated with poor funding and coordination, which resulted in fear and mistrust among healthcare workers, which inadvertently affected RI SD.[

30,

39]

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted and disrupted RI programs. The RI programs were only resilient for planned RISS visits from the LGA to HFs and vaccine supply to apex facilities; interventions were largely coordinated and executed by non-frontline healthcare workers. However, other sub-thematic areas suffered significant setbacks during the pandemic.

The effect of this pandemic on RI programs was contingent on the level at which it was coordinated. The greatest impact was observed for activities at the HF level, which had a direct effect on SD. However, activities coordinated at the state and LGA levels had little to no effect on SD.

Therefore, this study recommends that the government increase its investments in the degree of oversight for RI program interventions executed at HF and community levels. A renewed focus and prioritization of these interventions, which have a more direct effect on SD, will improve the resilience of RI and PHC systems, and ultimately guarantee improved performance even in future pandemics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information are available for this study, Figure S1: The six (6) Northern states SCIDaR provides RI strengthening support,[

42] Figure S2: The study model/framework using SEM designed path analysis [Hypothesis H2.1 - H6.1], Figure S3: Components with factor loadings matrix, Figure S4: Factor loading in components, Table S1: Questionnaire guide for survey, Table S2: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett's Test, Table S3: Initial Eigenvalues and Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings, Table S4: Initial Eigenvalues and Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.Jr., R.I., Y.Y., U.I., and M.A.; methodology, E.A.Jr., R.I., and U.I., software, E.A.Jr.; validation, Y.Y., U.I., C.O., A.A., H.T., M.M., and R.F.; formal analysis, E.A.Jr., R.I., and C.O.; investigation, E.A.Jr., C.O., A.A., H.T., M.M., and R.F.; resources, Y.Y., U.I., and M.A.; data curation, Y.Y., C.O., A.A., H.T., M.M., R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.Jr., R.I., U.I., and C.O.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y., A.A., H.T., M.M., and R.F.; visualization, E.A.Jr., R.I., R.I., and C.O.; supervision, Y.Y., U.I., and M.A.; project administration, R.I., U.I., M.A.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC was funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), grant number OPP1127484.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nigerian National Health Research Ethics Committee with approval number NHREC/01/01/2007-23/08/2022, granted on August 23, 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictive usage from the different levels of governments represented in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all McKing consultants, State Immunization Officers, Coordinators of the State Emergency Operations Centers (EOCs), Members of the State Primary Health Care Development Agencies, and Management Boards; for their unwavering support and invaluable contributions towards the successful implementation of this research program. Your dedication and commitment to this project have been instrumental in enabling us to achieve our research goals. Thank you for your cooperation and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Research questions

-

To what extent has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the performance of RI programs in 6 Northern Nigerian states, in terms of?

- a.

Leadership and governance

- b.

Service delivery

- c.

Monitoring & evaluation/Supportive supervision

- d.

Community engagement

- e.

Vaccine supply chain

- f.

Funding and financial management

- g.

Capacity building

What was the performance of the RI program during pre-pandemic periods and how has this changed?

What adaptive measures were utilized and how did it influence the RI program during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Which stakeholders, processes, and factors are responsible/have contributed to the resilience of the RI program amidst pandemic strains?

What are the persisting challenges?

What policy and program changes can be made to bolster the existing RI program and support the integration of COVID-19 interventions?

References

- J. Liu et al., “Community transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2, Shenzhen, China, 2020,” Emerg. Infect. Dis., vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 1320–1323, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2606.200239. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li, “An Outbreak of NCIP (2019-nCoV) Infection in China — Wuhan, Hubei Province, 2019−2020,” China CDC Wkly., vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 79–80, Jan. 2020. https://doi.org/10.46234/CCDCW2020.022. [CrossRef]

- NHS, “Landmark moment as first NHS patient receives COVID-19 vaccination.” 2020.

- O. Services, “First case of coronavirus disease confirmed in Nigeria - Nigeria.” [Online]. Available: https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/first-case-coronavirus-disease-confirmed-nigeria.

- NCDC, “NCDC coronavirus COVID-19 microsite.” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/advisory/.

- GAVI, “Combining COVID-19 and routine vaccination: Nigeria implements a ‘whole family’ approach.” [Online]. Available: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/combining-covid-19-and-routine-vaccination-nigeria-implements-whole-family-approach?gclid=Cj0KCQjw6pOTBhCTARIsAHF23fI2oGsW8VwCEdYfjFrVquJm6PPpW0NOMp_3rq0ZjMbFusJ1L4zyGyAaApeOEALw_wcB.

- S. Mader and T. Rüttenauer, “The Effects of Non-pharmaceutical Interventions on COVID-19 Mortality: A Generalized Synthetic Control Approach Across 169 Countries,” Front. Public Heal., vol. 10, Apr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPUBH.2022.820642/FULL. [CrossRef]

- O. J. Watson, G. Barnsley, J. Toor, A. B. Hogan, P. Winskill, and A. C. Ghani, “Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study,” Lancet Infect. Dis., vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1293–1302, Sep. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6. [CrossRef]

- C. Dan-Nwafor et al., “Nigeria’s public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic: January to May 2020,” J. Glob. Health, vol. 10, no. 2, Dec. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7189/JOGH.10.020399. [CrossRef]

- G. Owhonda et al., “Community awareness, perceptions, enablers and potential barriers to non-pharmaceutical interventions (npis) in the COVID-19 pandemic in Rivers State, Nigeria,” Biomed. J. Sci. & Tech. Res., vol. 36, no. 5, Apr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.26717/bjstr.2021.36.005928. [CrossRef]

- I. Abubakar et al., “The Lancet Nigeria Commission: Investing in health and the future of the nation,” Lancet, vol. 399, no. 10330, pp. 1155–1200, Apr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02488-0. [CrossRef]

- C. Mbaeyi et al., “Routine Immunization Service Delivery Through the Basic Package of Health Services Program in Afghanistan: Gaps, Challenges, and Opportunities,” J. Infect. Dis., vol. 216, no. Suppl 1, p. S273, Jul. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/INFDIS/JIW549. [CrossRef]

- B. V. Uba et al., “Strengthening facility-based immunization service delivery in local government areas at high risk for polio in Northern Nigeria, 2014-2015,” PAMJ. 2021; 406, vol. 40, no. 6, p. 6, Nov. 2021. https://doi.org/10.11604/PAMJ.SUPP.2021.40.1.25865. [CrossRef]

- A. Shet et al., “Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on routine immunisation services: Evidence of disruption and recovery from 170 countries and territories,” Lancet Glob. Heal., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. e186–e194, Apr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00512-x. [CrossRef]

- K. Causey et al., “Estimating global and regional disruptions to routine childhood vaccine coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: A modelling study,” Lancet, vol. 398, no. 10299, pp. 522–534, Apr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01337-4. [CrossRef]

- K. Hirabayashi, “The impact of COVID-19 on routine vaccinations | UNICEF East Asia and Pacific,” Unicef. 2020. Accessed: Oct. 18, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.unicef.org/eap/stories/impact-covid-19-routine-vaccinations.

- World Health Organization, “COVID-19 pandemic fuels largest continued backslide in vaccinations in three decades,” pp. 1–5, 2022, Accessed: Oct. 18, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-07-2022-covid-19-pandemic-fuels-largest-continued-backslide-in-vaccinations-in-three-decades.

- GAVI, “At least 80 million children at risk of disease as COVID-19 disrupts vaccination efforts, warn Gavi, WHO and UNICEF. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance,” 2020. Accessed: Oct. 18, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/least-80-million-children-risk-disease-covid-19-disrupts-vaccination-efforts.

- A. Oku et al., “Factors affecting the implementation of childhood vaccination communication strategies in Nigeria: a qualitative study,” BMC Public Health, vol. 17, no. 1, Feb. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-017-4020-6. [CrossRef]

- S. A. SeyedAlinaghi et al., “Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine vaccination coverage of children and adolescents: A systematic review,” Heal. Sci. Reports, vol. 5, no. 2, Mar. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/HSR2.516. [CrossRef]

- M. Sharma et al., “Magnitude and causes of routine immunization disruptions during COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries,” J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 3991, 2021. https://doi.org/10.4103/JFMPC.JFMPC_1102_21. [CrossRef]

- OECD, “The territorial impact of COVID-19 : Managing The Crisis Across Levels of Government,” Organ. fo Econ. Coop. Dev., no. April, pp. 2–44, 2020, Accessed: Oct. 19, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1/.

- I. M. Bello et al., “Implementation of integrated supportive supervision in the context of coronavirus 19 pandemic: its effects on routine immunization and vaccine preventable surveillance diseases indicators in the East and Southern African countries,” PAMJ. 2021; 38:164, vol. 38, no. 164, Feb. 2021. https://doi.org/10.11604/PAMJ.2021.38.164.27349. [CrossRef]

- X. Bosch-Capblanch, S. Liaqat, and P. Garner, “Managerial supervision to improve primary health care in low- and middle-income countries,” Cochrane database Syst. Rev., vol. 2011, no. 9, Sep. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006413.PUB2. [CrossRef]

- S. Bradley et al., “An in-depth exploration of health worker supervision in Malawi and Tanzania,” BMC Hum Res Heal., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 43, Sep. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-43. [CrossRef]

- T. Madede et al., “The impact of a supportive supervision intervention on health workers in Niassa, Mozambique: A cluster-controlled trial,” Hum. Resour. Health, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Sep. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12960-017-0213-4/TABLES/5. [CrossRef]

- R. O. Onyango, “Designing an M&E system during a pandemic: Successes and failures at a project’s inception phase,” Independent Development Evaluation (IDEV) - African Development Bank, 2021. http://idev.afdb.org/en/content/designing-me-system-during-pandemic-successes-and-failures-projects-inception-phase (accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- UNICEF, “The critical role of UNICEF in accelerating COVID-19 vaccine rollout through National Logistics Work,” Supply Division, 2021. https://www.unicef.org/supply/stories/critical-role-unicef-accelerating-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-through-national-logistics-work (accessed Jan. 08, 2023).

- E. Faiva et al., “Drug supply shortage in Nigeria during COVID-19: efforts and challenges,” J. Pharm. Policy Pract., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–3, Dec. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40545-021-00302-1/METRICS. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Essoh et al., “Early Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on Immunization Services in Nigeria,” Vaccines, vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 1–14, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10071107. [CrossRef]

- V. O. Olutuase, C. J. Iwu-Jaja, C. P. Akuoko, E. O. Adewuyi, and V. Khanal, “Medicines and vaccines supply chains challenges in Nigeria: a scoping review,” BMC Public Health, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Dec. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-021-12361-9/TABLES/8. [CrossRef]

- WHO and UNICEF, “Maintaining routine immunization services vital during the COVID-19 pandemic,” 2020. https://www.unicef.org/tajikistan/press-releases/maintaining-routine-immunization-services-vital-during-covid-19-pandemic-who-and (accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- GAVI, “Routine vaccinations during a pandemic – benefit or risk?,” 2020. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/routine-vaccinations-during-pandemic-benefit-or-risk?gclid=Cj0KCQiAzeSdBhC4ARIsACj36uGt_uOFfiMwXitGM_dO30qknvxXbswogi3cOo7YW1X0hO9Ay--0Bu0aAmaIEALw_wcB (accessed Jan. 08, 2023).

- World Health Organisation, “Guiding principles for immunization activities during the COVID-19 pandemic,” WHO/2019-nCoV/immunization_services/2020.1, no. March, pp. 17–20, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331590/WHO-2019-nCoV-immunization_services-2020.1-eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization, “COVID-19 Global Risk Communication and Community Engagement Strategy,” Interim Guid., no. December 2020, pp. 20–21, 2020.

- E. Musa, “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immunization Programs in Kaduna State Nigeria,” Sabin Vaccine Institute, 2020. https://www.sabin.org/resources/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-immunization-programs-in-kaduna-state-nigeria/ (accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- G20 Italian Presidency, “The impact of COVID-19 on digital financial inclusion,” Glob. Partnersh. Financ. Incl. by World Bank, no. November, pp. 1–29, 2021.

- C. Alagboso, “Overcoming the Challenges of Financing Routine Immunisation Beyond COVID-19,” Nigeria Health Watch, 2022. https://nigeriahealthwatch.com/overcoming-the-challenges-of-financing-routine-immunisation-beyond-covid-19/ (accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- B. S. Aregbeshola and M. O. Folayan, “Nigeria’s financing of health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and recommendations,” World Med. Heal. Policy, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 195, Mar. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/WMH3.484. [CrossRef]

- K. Abbas et al., “Routine childhood immunisation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a benefit–risk analysis of health benefits versus excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection,” Lancet Glob. Heal., vol. 8, no. 10, pp. e1264–e1272, Oct. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30308-9. [CrossRef]

- R. Ranganathan and A. M. Khan, “Routine immunization services during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic,” Indian J. Community Heal., vol. 32, no. 2 Special Issue, pp. 236–239, 2020. https://doi.org/10.47203/ijch.2020.v32i02supp.011. [CrossRef]

- USAID, “The power of partnerships for improved routine immunization in Nigeria.” 2019. Accessed: Apr. 24, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://mcsprogram.org/the-power-of-partnerships-for-improved-routine-immunization-in-nigeria/.

- N. Fox, A. Hunn, and N. Mathers, “Sampling and Sample Size Calculation,” NIHR RDS East Midlands, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–4, May 2022, [Online]. Available: https://www.bdct.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Sampling-and-Sample-Size-Calculation.pdf.

- D. Lakens, “Sample size justification,” Collabra Psychol., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–31, Jun. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.33267. [CrossRef]

- A. Aliyu and L. Amadu, “Urbanization, cities and health: the challenges to Nigeria—a review,” Ann. Afr. Med., vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 149–158, Oct. 2017. https://doi.org/10.4103/aam.aam_1_17. [CrossRef]

- K. Farrell, “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of Nigeria’s Rapid Urban Transition,” Urban Forum, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 277–298, Sep. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12132-018-9335-6/TABLES/5. [CrossRef]

- IA2030, “Monitoring and Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) Framework,” Immunization Agenda 2030. pp. 1–34, 2020.

- A. P. Khatiwada et al., “Impact of the first phase of COVID-19 pandemic on childhood routine immunisation services in Nepal: a qualitative study on the perspectives of service providers and users,” J. Pharm. Policy Pract., vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40545-021-00366-Z. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Turner, G. Angels, A. O. Tsui, M. Wilkinson, and R. Magnani, SAMPLING MANUAL for FACILITY SURVEYS. MEASURE Evaluation Manual Series, No. 3., no. 3. 2001.

- S. B. Green and Y. Yang, “Evaluation of Dimensionality in the Assessment of Internal Consistency Reliability: Coefficient Alpha and Omega Coefficients,” Educ. Meas. Issues Pract., vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 14–20, Dec. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/EMIP.12100. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Davenport, M. L. Davison, P. Y. Liou, and Q. U. Love, “Reliability, Dimensionality, and Internal Consistency as Defined by Cronbach: Distinct Albeit Related Concepts,” Educ. Meas. Issues Pract., vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 4–9, Dec. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/EMIP.12095. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Collins, “Research Design and Methods,” Encycl. Gerontol., pp. 433–442, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-370870-2/00162-1. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Yu, “Test-Retest Reliability,” Encycl. Soc. Meas., pp. 777–784, Jan. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-369398-5/00094-3. [CrossRef]

- P. Wood, “Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research,” Am. Stat., vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 91–92, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1198/tas.2008.s98. [CrossRef]

- G. Pavlov, A. Maydeu-Olivares, and D. Shi, “Using the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR) to Assess Exact Fit in Structural Equation Models,” Educ. Psychol. Meas., vol. 81, no. 1, pp. 110–130, Feb. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164420926231/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0013164420926231-FIG1.JPEG. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Bentler, “Comparative fit indexes in structural models,” Psychol. Bull., vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 238–246, 1990. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [CrossRef]

- K. Kumar, A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd edn, vol. 175, no. 3. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985x.2012.01045_12.x. [CrossRef]

- S. Parry, “Fit Indices commonly reported for CFA and SEM,” Cornell Univ. Cornell Stat. Consult. Unit, p. 2, 2020.

- J. S. Tanaka and G. J. Huba, “A fit index for covariance structure models under arbitrary GLS estimation,” Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol., vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 197–201, Nov. 1985. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1985.tb00834.x. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Schumacker and R. G. Lomax, “A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling : Fourth Edition,” A Beginner’s Guid. to Struct. Equ. Model., Jun. 2004. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610904. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Stone, “The Ethical Use of Fit Indices in Structural Equation Modeling: Recommendations for Psychologists,” Front. Psychol., vol. 12, p. 5221, Nov. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2021.783226/BIBTEX. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Creswell, Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: choosing among five approaches, vol. 2. 2007. Accessed: Sep. 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkposzje))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1807302.

- S. N. Khan, “Qualitative Research Method: Grounded Theory,” Int. J. Bus. Manag., vol. 9, no. 11, p. p224, Oct. 2014. https://doi.org/10.5539/IJBM.V9N11P224. [CrossRef]

- L. Cohen, L. Manion, and K. Morrison, Research Methods in Education. 2007. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203029053. [CrossRef]

- M. O. C. Ota, S. Badur, L. Romano-Mazzotti, and L. R. Friedland, “Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunization,” Ann. Med., vol. 53, no. 1, p. 2286, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2021.2009128. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF, “Routine immunization of children crucial during the pandemic,” 2020. https://www.unicef.org/montenegro/en/stories/routine-immunization-children-crucial-during-pandemic (accessed Jan. 08, 2023).

- World Health Organization, “COVID-19 Pandemic Leads to Major Backsliding on Childhood Vaccinations, New WHO, UNICEF Data Shows,” News release, 2021. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/covid-19-pandemic-leads-major-backsliding-childhood-vaccinations-new-who-unicef-data (accessed Jan. 08, 2023).

- Save the Children, “SCALING UP ROUTINE IMMUNISATION COVERAGE IN NIGERIA,” 2022. https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/blogs/2022/scaling-up-routine-immunisation-coverage-in-nigeria (accessed Jan. 08, 2023).

- NPHCDA, “Community engagement strategy for strengthening routine immunization in northern nigeria,” pp. 1–20, 2022, [Online]. Available: https://publications.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=22337&lid=3.

- A. Oyo-Ita et al., “Effects of engaging communities in decision-making and action through traditional and religious leaders on vaccination coverage in Cross River State, Nigeria: A cluster-randomised control trial,” vol. 16, p. e0248236, Apr. 2021, Accessed: May 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0248236.

- E. Gooding, E. Spiliotopoulou, and P. Yadav, “Impact of vaccine stockouts on immunization coverage in Nigeria,” Vaccine, vol. 37, no. 35, pp. 5104–5110, Aug. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.006. [CrossRef]

- S. Molemodile, M. Wotogbe, and S. Abimbola, “Evaluation of a pilot intervention to redesign the decentralised vaccine supply chain system in Nigeria,” vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 601–616, May 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1291700. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF, “Lessons Learned and Good Practices: Country-Specific Case Studies on Immunization Activities during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” 2021. Accessed: Oct. 19, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.unicef.org/media/115221/file/Lessons-Learned-and-Good-Practices-Immunization-Activities-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-2021.pdf.

- M. Aina, U. Igbokwe, L. Jegede, R. Fagge, A. Thompson, and N. Mahmoud, “Preliminary results from direct-to-facility vaccine deliveries in Kano, Nigeria,” Vaccine, vol. 35, no. 17, pp. 2175–2182, Apr. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.VACCINE.2016.11.100. [CrossRef]

- A. Uchenna, J. Saleh, Saddiq, O. Eze, P. Ogbonna, and et al., “Intensified Routine Immunization (RI) Activities as A Strategy for Improving Routine Immunization and Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) Surveillance outcomes; Lessons from Intensified Activities Conducted in 2 LGAs in Abia State Nigeria,” J. Community Med. Public Heal., vol. 2, no. 2, May 2018. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2228.100032. [CrossRef]

- A. Shet et al., “Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on routine immunisation services: Evidence of disruption and recovery from 170 countries and territories,” Lancet Glob. Heal., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. e186–e194, Apr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00512-x. [CrossRef]

- K. Causey et al., “Estimating global and regional disruptions to routine childhood vaccine coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: a modelling study,” Lancet, vol. 398, no. 10299, pp. 522–534, Aug. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01337-4. [CrossRef]

- allAfrica.com, “Nigeria: Rising Cost of Healthcare in Nigeria Amid Covid-19,” 2020. https://allafrica.com/stories/202103070279.html (accessed Jan. 08, 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).