Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

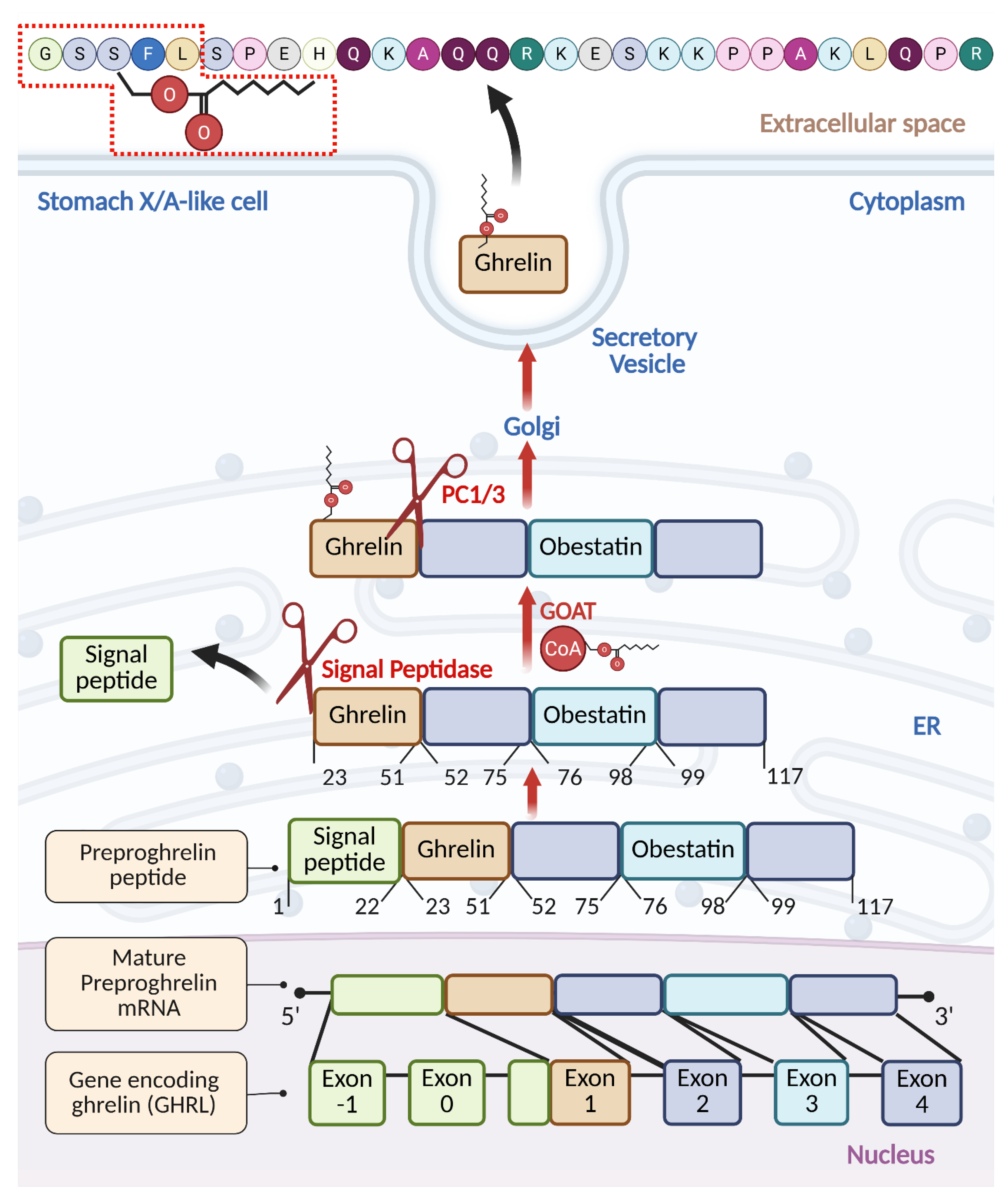

2. Processing and Maturation of Ghrelin

3. The GOAT—A Single Enzyme for the Single Substrate

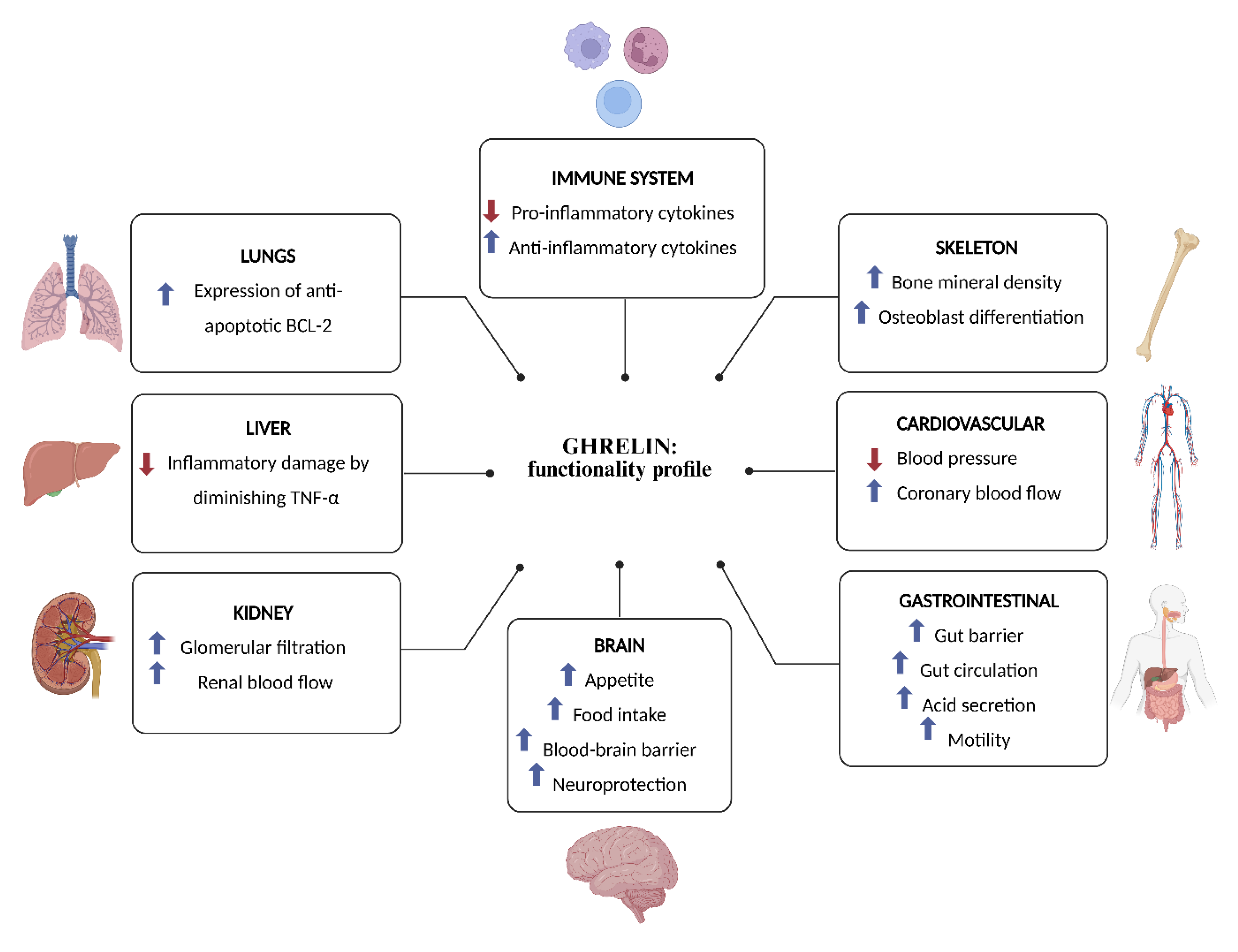

4. Ghrelin: Functionality Profile

4.1. Ghrelin Serves as a “Hunger Hormone” Regulating Food Intake and Obesity

4.2. Ghrelin is a Ligand for the Growth Hormone Secretagogue Receptor 1a (GHSR1a)

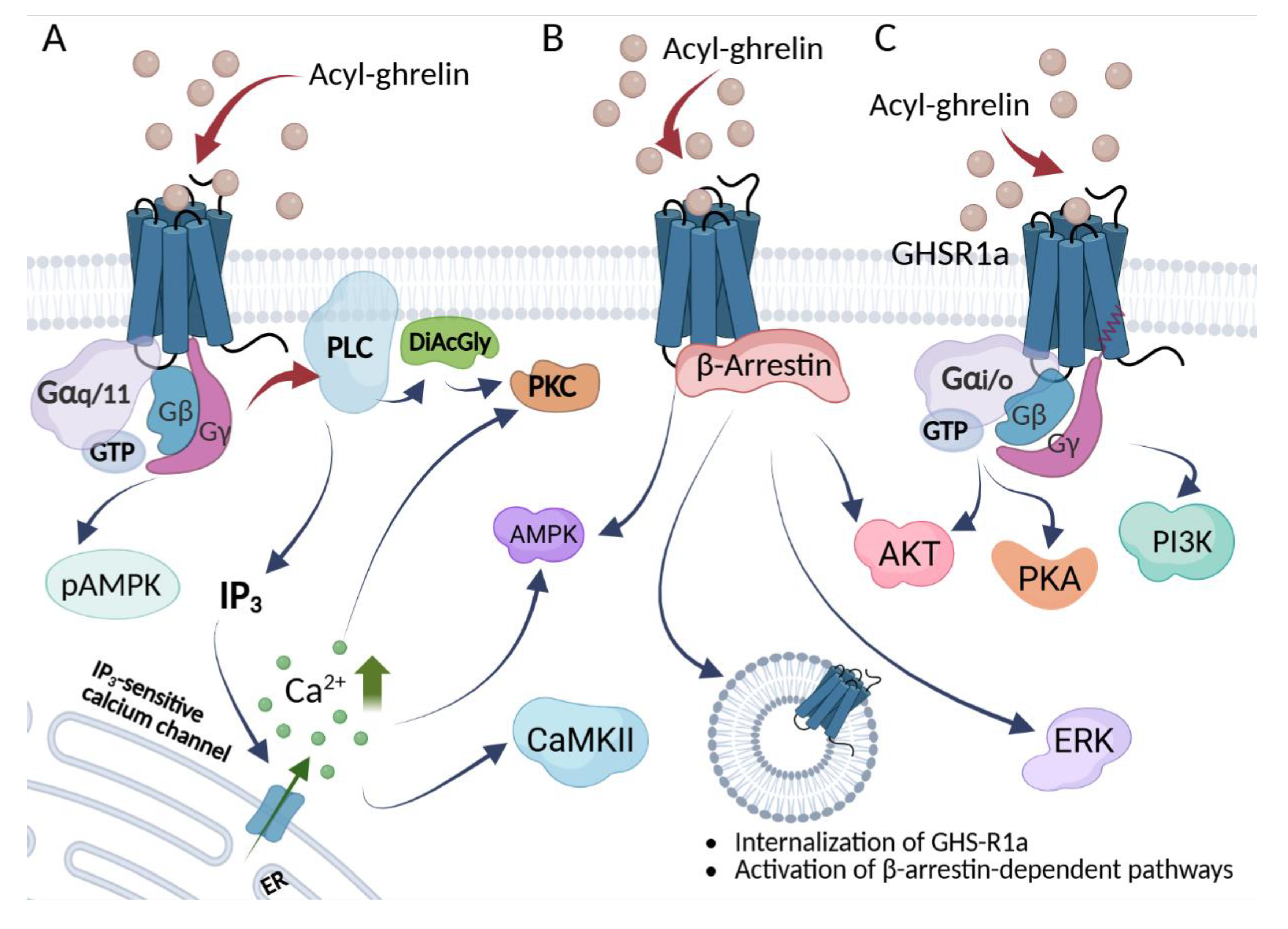

5. GHSR1a Signaling Pathways

| Ligand | Type | Activity | Signaling Pathways | Selected refs | |||

| Ca2+ mobilization | β-arrestin | GHSR1a intern. |

ERK Phosph. |

||||

| Ghrelin (human, acylated) | Endogenous peptide | Full agonist (canonical) | + | + | + | + | [1,112] |

| Des--acyl ghrelin (DAG) | Endogenous peptide (des--acyl) | Weak/low--potency agonist in vitro; often functionally GHSR1a--independent in vivo | [38] | ||||

| Mini-ghrelins (1–15, 1–14, 1–11) | Endogenous peptide fragments | Competitive antagonists | [37,38] | ||||

| LEAP--2 | Endogenous peptide/protein | Competitive antagonist | [114] | ||||

| Anamorelin | Small--molecule | Potent agonist | [107,122] | ||||

| Ibutamoren (MK--677) | Small--molecule | Potent, selective, orally active agonist | + | + | + | + | [112,123,124] |

| + | + | + | + | ||||

| L--692,585 | Small--molecule | Agonist | [112,125,126] | ||||

| JMV2959 | Small--molecule | Unbiased antagonist; bias-inverse agonist | +/- | Basal - | 0 | [112,127] | |

| Compound 21 (C21) | Small--molecule | Neutral antagonist | [103] | ||||

| PF-5190457 | Small--molecule | Orally active inverse agonist | [128,129] | ||||

| Basal - | 0 | ||||||

| [D--Lys3]--GHRP--6 | Peptide analog | Preferentially β-arrestin pathway blocker; bias-inverse agonist | [112,130,131] | ||||

| Substance P analog (D--Arg11,D--Phe55,D--Trp77,99, Leu1111--SP) |

Peptide analog | Inverse agonist at higher concentrations; attenuates β--arrestin at low concentrations | Basal - | Basal - | [112,132] | ||

| KwFwLL | Peptidomimetic | Inverse agonist | [133] | ||||

| AwFwLL | Peptidomimetic | Agonist | [133] | ||||

6. Ghrelin as an Anti-Inflammatory Agent

7. The Neuroimmune Connection—Ghrelin’s Role in the Nervous System

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

BioRender.com/6s2oynh

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHSR1a | growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a |

| GOAT | ghrelin O-acyltransferase |

| LEAP-2 | Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| GCF | gingival crevicular fluid |

| RIA | radioimmunoassay |

| CoA | Coenzyme A |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| PC1/3 | prohormone convertase 1/3 |

| PC | prostate cancer |

| APC | activated protein |

| MBOAT | membrane-bound-O-acyltransferase |

| AG | acyl ghrelin |

| DAG | des-acyl ghrelin |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½ |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| AKT | Protein kinase B; serine/threonine protein kinase |

| APT1 | Acyl-Protein Thioesterase 1/Lysophospholipase |

| PMSF | phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| AEBSF | 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride |

| MAFP | methoxy arachidonyl fluorophosphonate |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| GH | growth hormone |

| PLC | phospholipase C |

| IP3 | inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| DiAcGly | Diacylglycerol |

| CamKII | Ca2+/calmodulindependent protein kinase-IIa |

| AMPK | 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase |

| PKA | protein kinase A |

| PKCε | protein kinase Cε |

| TM | transmembrane helix |

| SNP | single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| DLys3-GHRP-6; D-Lys3 | [D-Lys3]-growth hormone–releasing peptide-6 |

| SP-analog | [D-Arg1,D-Phe5,D-Trp7, 9,Leu11]-substance P |

| HMGB1 | High Mobility Group Box 1 |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA sequencing |

| NASH | non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| MCP-1 | monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| Arg-1 | arginase-1 |

| Mgl-1 | macrophage galactose-type lectin-1 |

| PA | palmitic acid |

| ARC | arcuate nucleus |

| PVN | paraventricular nucleus |

| LHA | lateral hypothalamic area |

| VMN | ventromedial nucleus |

| DMN | dorsomedial nucleus |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| NPY | neuropeptide Y |

| AgRP | agouti-related peptide |

| POMC | proopiomelanocortin |

| CART | cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| ACC | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| CPT1 | carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| UCP2 | uncoupling protein-2 |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| IRI | ischemia–reperfusion injury |

| HPA | hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal |

| BChEI | butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor |

| VTA | ventral tegmental area |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| DRD1 | dopamine receptor D1 |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| GHSR1b | growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1b |

| AUD | alcohol use disorder |

| NAc | nucleus accumbens |

| CPP | conditioned place preference |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

References

- Kojima, M.; Hosoda, H.; Date, Y.; Nakazato, M.; Matsuo, H.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 1999, 402, 656–660. [CrossRef]

- Ghelardoni, S.; Carnicelli, V.; Frascarelli, S.; Ronca-Testoni, S.; Zucchi, R. Ghrelin tissue distribution: comparison between gene and protein expression. J Endocrinol Invest 2006, 29, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Groschl, M.; Topf, H.G.; Bohlender, J.; Zenk, J.; Klussmann, S.; Dotsch, J.; Rascher, W.; Rauh, M. Identification of ghrelin in human saliva: production by the salivary glands and potential role in proliferation of oral keratinocytes. Clin Chem 2005, 51, 997–1006. [CrossRef]

- Ohta, K.; Laborde, N.J.; Kajiya, M.; Shin, J.; Zhu, T.; Thondukolam, A.K.; Min, C.; Kamata, N.; Karimbux, N.Y.; Stashenko, P.; et al. Expression and possible immune-regulatory function of ghrelin in oral epithelium. J Dent Res 2011, 90, 1286–1292. [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, H.; Kangawa, K. Standard sample collections for blood ghrelin measurements. Methods Enzymol 2012, 514, 113–126. [CrossRef]

- Drazen, D.L.; Vahl, T.P.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Seeley, R.J.; Woods, S.C. Effects of a fixed meal pattern on ghrelin secretion: evidence for a learned response independent of nutrient status. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, D.E.; Purnell, J.Q.; Frayo, R.S.; Schmidova, K.; Wisse, B.E.; Weigle, D.S. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 2001, 50, 1714–1719. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Wang, G.; Englander, E.W.; Kojima, M.; Greeley, G.H., Jr. Ghrelin, a new gastrointestinal endocrine peptide that stimulates insulin secretion: enteric distribution, ontogeny, influence of endocrine, and dietary manipulations. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 185–190. [CrossRef]

- Widmayer, P.; Goldschmid, H.; Henkel, H.; Kuper, M.; Konigsrainer, A.; Breer, H. High fat feeding affects the number of GPR120 cells and enteroendocrine cells in the mouse stomach. Front Physiol 2015, 6, 53. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Reed, J.T.; Wang, G.; Han, S.; Englander, E.W.; Greeley, G.H., Jr. Ghrelin secretion is not reduced by increased fat mass during diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008, 295, R429–435. [CrossRef]

- Konturek, P.C.; Brzozowski, T.; Pajdo, R.; Nikiforuk, A.; Kwiecien, S.; Harsch, I.; Drozdowicz, D.; Hahn, E.G.; Konturek, S.J. Ghrelin-a new gastroprotective factor in gastric mucosa. J Physiol Pharmacol 2004, 55, 325–336.

- Zhao, T.J.; Sakata, I.; Li, R.L.; Liang, G.; Richardson, J.A.; Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L.; Zigman, J.M. Ghrelin secretion stimulated by beta1-adrenergic receptors in cultured ghrelinoma cells and in fasted mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 15868–15873. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.L.; Cummings, D.E.; Grill, H.J.; Kaplan, J.M. Meal-related ghrelin suppression requires postgastric feedback. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 2765–2767. [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, U.; Gambineri, A.; Vicennati, V.; Heiman, M.L.; Tschop, M.; Pasquali, R. Plasma ghrelin, obesity, and the polycystic ovary syndrome: correlation with insulin resistance and androgen levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002, 87, 5625–5629. [CrossRef]

- Riis, A.L.; Hansen, T.K.; Moller, N.; Weeke, J.; Jorgensen, J.O. Hyperthyroidism is associated with suppressed circulating ghrelin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 853–857. [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, U.; Gambineri, A.; Pelusi, C.; Genghini, S.; Cacciari, M.; Otto, B.; Castaneda, T.; Tschop, M.; Pasquali, R. Testosterone replacement therapy restores normal ghrelin in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 4139–4143. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Yoon, Y.S.; Park, C.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Um, T.H.; Baik, H.W.; Jang, E.J.; Lee, S.; Park, H.S.; Oh, S.W. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori increases ghrelin mRNA expression in the gastric mucosa. J Korean Med Sci 2010, 25, 265–271. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, J.; Anini, Y. Insulin and norepinephrine regulate ghrelin secretion from a rat primary stomach cell culture. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3646–3656. [CrossRef]

- Sakata, I.; Park, W.M.; Walker, A.K.; Piper, P.K.; Chuang, J.C.; Osborne-Lawrence, S.; Zigman, J.M. Glucose-mediated control of ghrelin release from primary cultures of gastric mucosal cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2012, 302, E1300–1310. [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, H.; Li, Y.; Ariyasu, H.; Hosoda, H.; Kanamoto, N.; Bando, M.; Yamada, G.; Hosoda, K.; Nakao, K.; Kangawa, K.; et al. Establishment of a novel ghrelin-producing cell line. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2940–2945. [CrossRef]

- Seim, I.; Collet, C.; Herington, A.C.; Chopin, L.K. Revised genomic structure of the human ghrelin gene and identification of novel exons, alternative splice variants and natural antisense transcripts. BMC Genomics 2007, 8, 298. [CrossRef]

- Yanagi, S.; Sato, T.; Kangawa, K.; Nakazato, M. The Homeostatic Force of Ghrelin. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 786–804. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.V.; Ren, P.G.; Avsian-Kretchmer, O.; Luo, C.W.; Rauch, R.; Klein, C.; Hsueh, A.J. Obestatin, a peptide encoded by the ghrelin gene, opposes ghrelin’s effects on food intake. Science 2005, 310, 996–999. [CrossRef]

- Hassouna, R.; Zizzari, P.; Tolle, V. The ghrelin/obestatin balance in the physiological and pathological control of growth hormone secretion, body composition and food intake. J Neuroendocrinol 2010, 22, 793–804. [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.; Granada, M.L.; Roca, M.; Palomera, E.; Puig, R.; Serra-Prat, M.; Puig-Domingo, M. Obestatin does not modify weight and nutritional behaviour but is associated with metabolic syndrome in old women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013, 78, 882–890. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cao, Y.; Voogd, K.; Steiner, D.F. On the processing of proghrelin to ghrelin. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 38867–38870. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Brown, M.S.; Liang, G.; Grishin, N.V.; Goldstein, J.L. Identification of the acyltransferase that octanoylates ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating peptide hormone. Cell 2008, 132, 387–396. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.A.; Solenberg, P.J.; Perkins, D.R.; Willency, J.A.; Knierman, M.D.; Jin, Z.; Witcher, D.R.; Luo, S.; Onyia, J.E.; Hale, J.E. Ghrelin octanoylation mediated by an orphan lipid transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 6320–6325. [CrossRef]

- Hormaechea-Agulla, D.; Gomez-Gomez, E.; Ibanez-Costa, A.; Carrasco-Valiente, J.; Rivero-Cortes, E.; F, L.L.; Pedraza-Arevalo, S.; Valero-Rosa, J.; Sanchez-Sanchez, R.; Ortega-Salas, R.; et al. Ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) enzyme is overexpressed in prostate cancer, and its levels are associated with patient’s metabolic status: Potential value as a non-invasive biomarker. Cancer Lett 2016, 383, 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gomez, E.; Jimenez-Vacas, J.M.; Carrasco-Valiente, J.; Herrero-Aguayo, V.; Blanca-Pedregosa, A.M.; Leon-Gonzalez, A.J.; Valero-Rosa, J.; Fernandez-Rueda, J.L.; Gonzalez-Serrano, T.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; et al. Plasma ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) enzyme levels: A novel non-invasive diagnosis tool for patients with significant prostate cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2018, 22, 5688–5697. [CrossRef]

- Delporte, C. Structure and physiological actions of ghrelin. Scientifica (Cairo) 2013, 2013, 518909. [CrossRef]

- Kakidani, H.; Furutani, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Noda, M.; Morimoto, Y.; Hirose, T.; Asai, M.; Inayama, S.; Nakanishi, S.; Numa, S. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for porcine beta-neo-endorphin/dynorphin precursor. Nature 1982, 298, 245–249. [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, S.; Inoue, A.; Kita, T.; Nakamura, M.; Chang, A.C.; Cohen, S.N.; Numa, S. Nucleotide sequence of cloned cDNA for bovine corticotropin-beta-lipotropin precursor. Nature 1979, 278, 423–427. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Hayashida, Y.; Iguchi, T.; Nakao, N.; Nakai, N.; Nakashima, K. Organization of the mouse ghrelin gene and promoter: occurrence of a short noncoding first exon. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 3697–3700. [CrossRef]

- Satou, M.; Nishi, Y.; Hishinuma, A.; Hosoda, H.; Kangawa, K.; Sugimoto, H. Identification of activated protein C as a ghrelin endopeptidase in bovine plasma. J Endocrinol 2015, 224, 61–73. [CrossRef]

- Seim, I.; Jeffery, P.L.; Thomas, P.B.; Walpole, C.M.; Maugham, M.; Fung, J.N.; Yap, P.Y.; O’Keeffe, A.J.; Lai, J.; Whiteside, E.J.; et al. Multi-species sequence comparison reveals conservation of ghrelin gene-derived splice variants encoding a truncated ghrelin peptide. Endocrine 2016, 52, 609–617. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, G.; Fittipaldi, A.; Lufrano, D.; Mustafa, E.R.; Castrogiovanni, D.; Barrile, F.; De Francesco, P.N.; Tolosa, M.J.; Rodriguez, S.S.; Lalonde, T.; et al. Mini-ghrelins: Functional Characterization of N-terminal Peptides Derived From Ghrelin Proteolysis in Male Samples. Endocrinology 2025, 166. [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, M.A.; Feighner, S.D.; Pong, S.S.; McKee, K.K.; Hreniuk, D.L.; Silva, M.V.; Warren, V.A.; Howard, A.D.; Van Der Ploeg, L.H.; Heck, J.V. Structure-function studies on the new growth hormone-releasing peptide, ghrelin: minimal sequence of ghrelin necessary for activation of growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a. J Med Chem 2000, 43, 4370–4376. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Hosoda, H.; Kitajima, Y.; Morozumi, N.; Minamitake, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Matsuo, H.; Kojima, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Kangawa, K. Structure-activity relationship of ghrelin: pharmacological study of ghrelin peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 287, 142–146. [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wang, Z.; Merrikh, C.N.; Lang, K.S.; Lu, P.; Li, X.; Merrikh, H.; Rao, Z.; Xu, W. Crystal structure of a membrane-bound O-acyltransferase. Nature 2018, 562, 286–290. [CrossRef]

- Campana, M.B.; Irudayanathan, F.J.; Davis, T.R.; McGovern-Gooch, K.R.; Loftus, R.; Ashkar, M.; Escoffery, N.; Navarro, M.; Sieburg, M.A.; Nangia, S.; et al. The ghrelin O-acyltransferase structure reveals a catalytic channel for transmembrane hormone acylation. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 14166–14174. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Nelson, T.A.; Guschina, I.A.; Parsons, L.C.; Lewis, C.L.; Brown, R.C.; Christian, H.C.; Davies, J.S.; Wells, T. Unacylated ghrelin promotes adipogenesis in rodent bone marrow via ghrelin O-acyl transferase and GHS-R(1a) activity: evidence for target cell-induced acylation. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 45541. [CrossRef]

- Murtuza, M.I.; Isokawa, M. Endogenous ghrelin-O-acyltransferase (GOAT) acylates local ghrelin in the hippocampus. J Neurochem 2018, 144, 58–67. [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A.; Tschop, M.; Robinson, S.M.; Heiman, M.L. Extent and direction of ghrelin transport across the blood-brain barrier is determined by its unique primary structure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002, 302, 822–827. [CrossRef]

- Campana, M.B.; Davis, T.R.; Novak, S.X.; Cleverdon, E.R.; Bates, M.; Krishnan, N.; Curtis, E.R.; Childs, M.D.; Pierce, M.R.; Morales-Rodriguez, Y.; et al. Cellular Uptake of a Fluorescent Ligand Reveals Ghrelin O-Acyltransferase Interacts with Extracellular Peptides and Exhibits Unexpected Localization for a Secretory Pathway Enzyme. ACS Chem Biol 2023, 18, 1880–1890. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Qin, S. Reactive Astrocytes in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Aging Dis 2019, 10, 664–675. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, M.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin: structure and function. Physiol Rev 2005, 85, 495–522. [CrossRef]

- Gauna, C.; van de Zande, B.; van Kerkwijk, A.; Themmen, A.P.; van der Lely, A.J.; Delhanty, P.J. Unacylated ghrelin is not a functional antagonist but a full agonist of the type 1a growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R). Mol Cell Endocrinol 2007, 274, 30–34. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.; Lambert, G.; Ika-Sari, C.; Dawood, T.; Lee, K.; Chopra, R.; Straznicky, N.; Eikelis, N.; Drew, S.; Tilbrook, A.; et al. Ghrelin modulates sympathetic nervous system activity and stress response in lean and overweight men. Hypertension 2011, 58, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.M.; Yung, B.Y.; Yip, S.P.; Ying, M.; Benzie, I.F.; Siu, P.M. Desacyl ghrelin prevents doxorubicin-induced myocardial fibrosis and apoptosis via the GHSR-independent pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014, 306, E311–323. [CrossRef]

- Mahbod, P.; Smith, E.P.; Fitzgerald, M.E.; Morano, R.L.; Packard, B.A.; Ghosal, S.; Scheimann, J.R.; Perez-Tilve, D.; Herman, J.P.; Tong, J. Desacyl Ghrelin Decreases Anxiety-like Behavior in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 388–399. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, H.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of Des-acyl Ghrelin on Insulin Sensitivity and Macrophage Polarization in Adipose Tissue. J Transl Int Med 2021, 9, 84–97. [CrossRef]

- Witley, S.; Edvardsson, C.E.; Aranas, C.; Tufvesson-Alm, M.; Stalberga, D.; Green, H.; Vestlund, J.; Jerlhag, E. Des-acyl ghrelin reduces alcohol intake and alcohol-induced reward in rodents. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 277. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Gomez-Ambrosi, J.; Catalan, V.; Rotellar, F.; Valenti, V.; Silva, C.; Mugueta, C.; Pulido, M.R.; Vazquez, R.; Salvador, J.; et al. The ghrelin O-acyltransferase-ghrelin system reduces TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis and autophagy in human visceral adipocytes. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 3038–3050. [CrossRef]

- Slupecka, M.; Wolinski, J.; Pierzynowski, S.G. The effects of enteral ghrelin administration on the remodeling of the small intestinal mucosa in neonatal piglets. Regul Pept 2012, 174, 38–45. [CrossRef]

- Bonfili, L.; Cuccioloni, M.; Cecarini, V.; Mozzicafreddo, M.; Palermo, F.A.; Cocci, P.; Angeletti, M.; Eleuteri, A.M. Ghrelin induces apoptosis in colon adenocarcinoma cells via proteasome inhibition and autophagy induction. Apoptosis 2013, 18, 1188–1200. [CrossRef]

- Toshinai, K.; Yamaguchi, H.; Sun, Y.; Smith, R.G.; Yamanaka, A.; Sakurai, T.; Date, Y.; Mondal, M.S.; Shimbara, T.; Kawagoe, T.; et al. Des-acyl ghrelin induces food intake by a mechanism independent of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 2306–2314. [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, A.; Inui, A.; Fujimiya, M.; Sakamaki, R.; Shinfuku, N.; Ueta, Y.; Meguid, M.M.; Kasuga, M. Stomach regulates energy balance via acylated ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin. Gut 2005, 54, 18–24. [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Dave, N.; Mugundu, G.M.; Davis, H.W.; Gaylinn, B.D.; Thorner, M.O.; Tschop, M.H.; D’Alessio, D.; Desai, P.B. The pharmacokinetics of acyl, des-acyl, and total ghrelin in healthy human subjects. Eur J Endocrinol 2013, 168, 821–828. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, A.; Mori, K.; Sugawara, A.; Mukoyama, M.; Yahata, K.; Suganami, T.; Takaya, K.; Hosoda, H.; Kojima, M.; Kangawa, K.; et al. Plasma ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin concentrations in renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002, 13, 2748–2752. [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, H.; Kojima, M.; Matsuo, H.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin: two major forms of rat ghrelin peptide in gastrointestinal tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 279, 909–913. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, N.; Hayashida, T.; Kuroiwa, T.; Nakahara, K.; Ida, T.; Mondal, M.S.; Nakazato, M.; Kojima, M.; Kangawa, K. Role for central ghrelin in food intake and secretion profile of stomach ghrelin in rats. J Endocrinol 2002, 174, 283–288. [CrossRef]

- De Vriese, C.; Gregoire, F.; Lema-Kisoka, R.; Waelbroeck, M.; Robberecht, P.; Delporte, C. Ghrelin degradation by serum and tissue homogenates: identification of the cleavage sites. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 4997–5005. [CrossRef]

- Schopfer, L.M.; Lockridge, O.; Brimijoin, S. Pure human butyrylcholinesterase hydrolyzes octanoyl ghrelin to desacyl ghrelin. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2015, 224, 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Blatnik, M.; Soderstrom, C.I. A practical guide for the stabilization of acylghrelin in human blood collections. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011, 74, 325–331. [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.P.; Gao, Y.; Geng, L.; Parks, R.J.; Pang, Y.P.; Brimijoin, S. Plasma butyrylcholinesterase regulates ghrelin to control aggression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 2251–2256. [CrossRef]

- Shanado, Y.; Kometani, M.; Uchiyama, H.; Koizumi, S.; Teno, N. Lysophospholipase I identified as a ghrelin deacylation enzyme in rat stomach. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 325, 1487–1494. [CrossRef]

- Satou, M.; Nishi, Y.; Yoh, J.; Hattori, Y.; Sugimoto, H. Identification and characterization of acyl-protein thioesterase 1/lysophospholipase I as a ghrelin deacylation/lysophospholipid hydrolyzing enzyme in fetal bovine serum and conditioned medium. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 4765–4775. [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, L.M.; Stowe, G.N.; De Lamo Marin, S.; Mayorov, A.V.; Hixon, M.S.; Janda, K.D. Identification of alpha2 macroglobulin as a major serum ghrelin esterase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2011, 50, 10699–10702. [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, H.; Doi, K.; Nagaya, N.; Okumura, H.; Nakagawa, E.; Enomoto, M.; Ono, F.; Kangawa, K. Optimum collection and storage conditions for ghrelin measurements: octanoyl modification of ghrelin is rapidly hydrolyzed to desacyl ghrelin in blood samples. Clin Chem 2004, 50, 1077–1080. [CrossRef]

- McGovern-Gooch, K.R.; Rodrigues, T.; Darling, J.E.; Sieburg, M.A.; Abizaid, A.; Hougland, J.L. Ghrelin Octanoylation Is Completely Stabilized in Biological Samples by Alkyl Fluorophosphonates. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 4330–4338. [CrossRef]

- Sangiao-Alvarellos, S.; Cordido, F. Effect of ghrelin on glucose-insulin homeostasis: therapeutic implications. Int J Pept 2010, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Dong, W.; Cui, X.; Zhou, M.; Simms, H.H.; Ravikumar, T.S.; Wang, P. Ghrelin down-regulates proinflammatory cytokines in sepsis through activation of the vagus nerve. Ann Surg 2007, 245, 480–486. [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.; Kim, H.G.; Hwang, L.; Seo, J.H.; Kim, S.; Hwang, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.; Chung, H.; Oh, M.S.; et al. Neuroprotective effect of ghrelin in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson’s disease by blocking microglial activation. Neurotox Res 2009, 15, 332–347. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yin, X.; Qi, Y.; Pendyala, L.; Chen, J.; Hou, D.; Tang, C. Ghrelin and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Cardiol Rev 2010, 6, 62–70. [CrossRef]

- Szentirmai, E.; Kapas, L.; Sun, Y.; Smith, R.G.; Krueger, J.M. Spontaneous sleep and homeostatic sleep regulation in ghrelin knockout mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007, 293, R510–517. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zeng, M.; He, W.; Huang, X.; Luo, L.; Zhang, H.; Deng, D.Y. Ghrelin protects alveolar macrophages against lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis through growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a-dependent c-Jun N-terminal kinase and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and suppresses lung inflammation. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 203–217. [CrossRef]

- Gubina, N.V.; Kupnovytska, I.H.; Mishchuk, V.H.; Markiv, H.D. Ghrelin Levels and Decreased Kidney Function in Patients with Early Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease Against the Background of Obesity. J Med Life 2020, 13, 530–535. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, N.; Hanada, R.; Teranishi, H.; Fukue, Y.; Tachibana, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Takeda, S.; Takeuchi, Y.; Fukumoto, S.; Kangawa, K.; et al. Ghrelin directly regulates bone formation. J Bone Miner Res 2005, 20, 790–798. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.T.; Kral, J.G. Ghrelin: integrative neuroendocrine peptide in health and disease. Ann Surg 2004, 239, 464–474. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, D.E. Ghrelin and the short- and long-term regulation of appetite and body weight. Physiol Behav 2006, 89, 71–84. [CrossRef]

- Sovetkina, A.; Nadir, R.; Fung, J.N.M.; Nadjarpour, A.; Beddoe, B. The Physiological Role of Ghrelin in the Regulation of Energy and Glucose Homeostasis. Cureus 2020, 12, e7941. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, G.; Samson, S.L.; Sun, Y. Ghrelin: much more than a hunger hormone. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2013, 16, 619–624. [CrossRef]

- Varela, L.; Vazquez, M.J.; Cordido, F.; Nogueiras, R.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Dieguez, C.; Lopez, M. Ghrelin and lipid metabolism: key partners in energy balance. J Mol Endocrinol 2011, 46, R43–63. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Gao, D.; Li, D. Role of ghrelin in promoting catch-up growth and maintaining metabolic homeostasis in small-for-gestational-age infants. Front Pediatr 2024, 12, 1395571. [CrossRef]

- Wortley, K.E.; Anderson, K.D.; Garcia, K.; Murray, J.D.; Malinova, L.; Liu, R.; Moncrieffe, M.; Thabet, K.; Cox, H.J.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; et al. Genetic deletion of ghrelin does not decrease food intake but influences metabolic fuel preference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 8227–8232. [CrossRef]

- Venables, G.; Hunne, B.; Bron, R.; Cho, H.J.; Brock, J.A.; Furness, J.B. Ghrelin receptors are expressed by distal tubules of the mouse kidney. Cell Tissue Res 2011, 346, 135–139. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A.P.; Bonner, T.I.; Foord, S.M.; Harmar, A.J.; Neubig, R.R.; Pin, J.P.; Spedding, M.; Kojima, M.; Kangawa, K. International Union of Pharmacology. LVI. Ghrelin receptor nomenclature, distribution, and function. Pharmacol Rev 2005, 57, 541–546. [CrossRef]

- Cowley, M.A.; Smith, R.G.; Diano, S.; Tschop, M.; Pronchuk, N.; Grove, K.L.; Strasburger, C.J.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Esterman, M.; Heiman, M.L.; et al. The distribution and mechanism of action of ghrelin in the CNS demonstrates a novel hypothalamic circuit regulating energy homeostasis. Neuron 2003, 37, 649–661. [CrossRef]

- Hattori, N.; Saito, T.; Yagyu, T.; Jiang, B.H.; Kitagawa, K.; Inagaki, C. GH, GH receptor, GH secretagogue receptor, and ghrelin expression in human T cells, B cells, and neutrophils. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001, 86, 4284–4291. [CrossRef]

- Van Craenenbroeck, M.; Gregoire, F.; De Neef, P.; Robberecht, P.; Perret, J. Ala-scan of ghrelin (1-14): interaction with the recombinant human ghrelin receptor. Peptides 2004, 25, 959–965. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Kitajima, Y.; Iwanami, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Minamitake, Y.; Hosoda, H.; Kojima, M.; Matsuo, H.; Kangawa, K. Structural similarity of ghrelin derivatives to peptidyl growth hormone secretagogues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 284, 655–659. [CrossRef]

- De Ricco, R.; Valensin, D.; Gaggelli, E.; Valensin, G. Conformation propensities of des-acyl-ghrelin as probed by CD and NMR. Peptides 2013, 43, 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Patel, K.; Tae, H.J.; Lustig, A.; Kim, J.W.; Mattson, M.P.; Taub, D.D. Ghrelin augments murine T-cell proliferation by activation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase and protein kinase C signaling pathways. FEBS Lett 2014, 588, 4708–4719. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Huang, S.M.; Chen, C.C.; Tsai, C.F.; Yeh, W.L.; Chou, S.J.; Hsieh, W.T.; Lu, D.Y. Ghrelin induces cell migration through GHS-R, CaMKII, AMPK, and NF-kappaB signaling pathway in glioma cells. J Cell Biochem 2011, 112, 2931–2941. [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, J.A.; Lemus, M.B.; Stark, R.; Santos, V.V.; Thompson, A.; Rees, D.J.; Galic, S.; Elsworth, J.D.; Kemp, B.E.; Davies, J.S.; et al. Ghrelin-AMPK Signaling Mediates the Neuroprotective Effects of Calorie Restriction in Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 3049–3063. [CrossRef]

- Cavalier, M.; Crouzin, N.; Ben Sedrine, A.; de Jesus Ferreira, M.C.; Guiramand, J.; Cohen-Solal, C.; Fehrentz, J.A.; Martinez, J.; Barbanel, G.; Vignes, M. Involvement of PKA and ERK pathways in ghrelin-induced long-lasting potentiation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the CA1 area of rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 2015, 42, 2568–2576. [CrossRef]

- Mousseaux, D.; Le Gallic, L.; Ryan, J.; Oiry, C.; Gagne, D.; Fehrentz, J.A.; Galleyrand, J.C.; Martinez, J. Regulation of ERK1/2 activity by ghrelin-activated growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1A involves a PLC/PKCvarepsilon pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2006, 148, 350–365. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Zas, I.; Lodeiro, M.; Gurriaran-Rodriguez, U.; Bouzo-Lorenzo, M.; Mosteiro, C.S.; Casanueva, F.F.; Casabiell, X.; Pazos, Y.; Camina, J.P. beta-Arrestin signal complex plays a critical role in adipose differentiation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2013, 45, 1281–1292. [CrossRef]

- Bouzo-Lorenzo, M.; Santo-Zas, I.; Lodeiro, M.; Nogueiras, R.; Casanueva, F.F.; Castro, M.; Pazos, Y.; Tobin, A.B.; Butcher, A.J.; Camina, J.P. Distinct phosphorylation sites on the ghrelin receptor, GHSR1a, establish a code that determines the functions of ss-arrestins. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 22495. [CrossRef]

- Mende, F.; Hundahl, C.; Plouffe, B.; Skov, L.J.; Sivertsen, B.; Madsen, A.N.; Luckmann, M.; Diep, T.A.; Offermanns, S.; Frimurer, T.M.; et al. Translating biased signaling in the ghrelin receptor system into differential in vivo functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E10255–E10264. [CrossRef]

- Dezaki, K.; Kakei, M.; Yada, T. Ghrelin uses Galphai2 and activates voltage-dependent K+ channels to attenuate glucose-induced Ca2+ signaling and insulin release in islet beta-cells: novel signal transduction of ghrelin. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2319–2327. [CrossRef]

- Shiimura, Y.; Horita, S.; Hamamoto, A.; Asada, H.; Hirata, K.; Tanaka, M.; Mori, K.; Uemura, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Iwata, S.; et al. Structure of an antagonist-bound ghrelin receptor reveals possible ghrelin recognition mode. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4160. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Yun, Y.; Xu, P.; He, X.; Guo, J.; Yin, W.; Xu, H.E.; Xie, X.; et al. Molecular recognition of an acyl-peptide hormone and activation of ghrelin receptor. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5064. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Yamada, Y.; Iihara, H.; Kobayashi, R.; Suzuki, A. Anamorelin in the Management of Cancer Cachexia: Clinical Efficacy, Challenges, and Future Directions. Anticancer Res 2025, 45, 865–881. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Kamada, H.; Semba, S.; Kato, N.; Teraoka, Y.; Mizumoto, T.; Tamaru, Y.; Hatakeyama, T.; Kouno, H.; Shibata, Y.; et al. Real-world effectiveness of anamorelin in patients with unresectable and relapse pancreatic cancer: a prospective observational study. J Gastrointest Oncol 2025, 16, 1268–1279. [CrossRef]

- Shiimura, Y.; Im, D.; Tany, R.; Asada, H.; Kise, R.; Kurumiya, E.; Wakasugi-Masuho, H.; Yasuda, S.; Matsui, K.; Kishikawa, J.I.; et al. The structure and function of the ghrelin receptor coding for drug actions. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2025, 32, 531–542. [CrossRef]

- Masuho, I.; Ostrovskaya, O.; Kramer, G.M.; Jones, C.D.; Xie, K.; Martemyanov, K.A. Distinct profiles of functional discrimination among G proteins determine the actions of G protein-coupled receptors. Sci Signal 2015, 8, ra123. [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, M.A.; Holst, B. The Complex Signaling Pathways of the Ghrelin Receptor. Endocrinology 2020, 161. [CrossRef]

- Mary, S.; Damian, M.; Louet, M.; Floquet, N.; Fehrentz, J.A.; Marie, J.; Martinez, J.; Baneres, J.L. Ligands and signaling proteins govern the conformational landscape explored by a G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 8304–8309. [CrossRef]

- Damian, M.; Marie, J.; Leyris, J.P.; Fehrentz, J.A.; Verdie, P.; Martinez, J.; Baneres, J.L.; Mary, S. High constitutive activity is an intrinsic feature of ghrelin receptor protein: a study with a functional monomeric GHS-R1a receptor reconstituted in lipid discs. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 3630–3641. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, V.T.; van Oeffelen, W.; Torres-Fuentes, C.; Chruscicka, B.; Druelle, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; van de Wouw, M.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Schellekens, H. Differential functional selectivity and downstream signaling bias of ghrelin receptor antagonists and inverse agonists. FASEB J 2019, 33, 518–531. [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.; Sillard, R.; Kleemeier, B.; Kluver, E.; Maronde, E.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Forssmann, W.G.; Schulz-Knappe, P.; Nehls, M.C.; Wattler, F.; et al. Isolation and biochemical characterization of LEAP-2, a novel blood peptide expressed in the liver. Protein Sci 2003, 12, 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yang, H.; Bednarek, M.A.; Galon-Tilleman, H.; Chen, P.; Chen, M.; Lichtman, J.S.; Wang, Y.; Dalmas, O.; Yin, Y.; et al. LEAP2 Is an Endogenous Antagonist of the Ghrelin Receptor. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 461–469 e466. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Huang, L.; Huang, Z.; Feng, D.; Clark, R.J.; Chen, C. LEAP-2: An Emerging Endogenous Ghrelin Receptor Antagonist in the Pathophysiology of Obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 717544. [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Ye, C.F.; Hu, N.; Yao, Q.; Cheng, W.S.; Cheng, Z.G.; Liu, Y. Ghrelin Relieves Obesity-Induced Myocardial Injury by Regulating the Epigenetic Suppression of miR-196b Mediated by lncRNA HOTAIR. Obes Facts 2022, 15, 540–549. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Shen, Y.; Ye, C.F.; Hu, N.; Yao, Q.; Lv, X.Z.; Long, S.L.; Ren, C.; Lang, Y.Y.; et al. Ghrelin protects against obesity-induced myocardial injury by regulating the lncRNA H19/miR-29a/IGF-1 signalling axis. Exp Mol Pathol 2020, 114, 104405. [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ye, C.; Tang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Xie, L.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y. Loss of LEAP-2 alleviates obesity-induced myocardial injury by regulating macrophage polarization. Exp Cell Res 2023, 430, 113702. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, S. LEAP2: Next game-changer of pharmacotherapy for overweight and obesity? Cell Rep Med 2022, 3, 100612. [CrossRef]

- Hola, L.; Zelezna, B.; Karnosova, A.; Kunes, J.; Fehrentz, J.A.; Denoyelle, S.; Cantel, S.; Blechova, M.; Sykora, D.; Myskova, A.; et al. A Novel Truncated Liver Enriched Antimicrobial Peptide-2 Palmitoylated at its N-Terminal Antagonizes Effects of Ghrelin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2022, 383, 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.N.A. An insight into the multifunctional role of ghrelin and structure activity relationship studies of ghrelin receptor ligands with clinical trials. Eur J Med Chem 2022, 235, 114308. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.M.; Polvino, W.J. Pharmacodynamic hormonal effects of anamorelin, a novel oral ghrelin mimetic and growth hormone secretagogue in healthy volunteers. Growth Horm IGF Res 2009, 19, 267–273. [CrossRef]

- Patchett, A.A.; Nargund, R.P.; Tata, J.R.; Chen, M.H.; Barakat, K.J.; Johnston, D.B.; Cheng, K.; Chan, W.W.; Butler, B.; Hickey, G.; et al. Design and biological activities of L-163,191 (MK-0677): a potent, orally active growth hormone secretagogue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 7001–7005. [CrossRef]

- Copinschi, G.; Van Onderbergen, A.; L’Hermite-Baleriaux, M.; Mendel, C.M.; Caufriez, A.; Leproult, R.; Bolognese, J.A.; De Smet, M.; Thorner, M.O.; Van Cauter, E. Effects of a 7-day treatment with a novel, orally active, growth hormone (GH) secretagogue, MK-677, on 24-hour GH profiles, insulin-like growth factor I, and adrenocortical function in normal young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996, 81, 2776–2782. [CrossRef]

- Jacks, T.; Hickey, G.; Judith, F.; Taylor, J.; Chen, H.; Krupa, D.; Feeney, W.; Schoen, W.; Ok, D.; Fisher, M.; et al. Effects of acute and repeated intravenous administration of L-692,585, a novel non-peptidyl growth hormone secretagogue, on plasma growth hormone, IGF-1, ACTH, cortisol, prolactin, insulin, and thyroxine levels in beagles. J Endocrinol 1994, 143, 399–406. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.G.; Cheng, K.; Schoen, W.R.; Pong, S.S.; Hickey, G.; Jacks, T.; Butler, B.; Chan, W.W.; Chaung, L.Y.; Judith, F.; et al. A nonpeptidyl growth hormone secretagogue. Science 1993, 260, 1640–1643. [CrossRef]

- Moulin, A.; Demange, L.; Berge, G.; Gagne, D.; Ryan, J.; Mousseaux, D.; Heitz, A.; Perrissoud, D.; Locatelli, V.; Torsello, A.; et al. Toward potent ghrelin receptor ligands based on trisubstituted 1,2,4-triazole structure. 2. Synthesis and pharmacological in vitro and in vivo evaluations. J Med Chem 2007, 50, 5790–5806. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.K.; Andrews, K.; Beveridge, R.; Cameron, K.O.; Chen, C.; Dunn, M.; Fernando, D.; Gao, H.; Hepworth, D.; Jackson, V.M.; et al. Discovery of PF-5190457, a Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable Ghrelin Receptor Inverse Agonist Clinical Candidate. ACS Med Chem Lett 2014, 5, 474–479. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.R.; Tapocik, J.D.; Ghareeb, M.; Schwandt, M.L.; Dias, A.A.; Le, A.N.; Cobbina, E.; Farinelli, L.A.; Bouhlal, S.; Farokhnia, M.; et al. The novel ghrelin receptor inverse agonist PF-5190457 administered with alcohol: preclinical safety experiments and a phase 1b human laboratory study. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 461–475. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Chan, W.W.; Barreto, A., Jr.; Convey, E.M.; Smith, R.G. The synergistic effects of His-D-Trp-Ala-Trp-D-Phe-Lys-NH2 on growth hormone (GH)-releasing factor-stimulated GH release and intracellular adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate accumulation in rat primary pituitary cell culture. Endocrinology 1989, 124, 2791–2798. [CrossRef]

- Traebert, M.; Riediger, T.; Whitebread, S.; Scharrer, E.; Schmid, H.A. Ghrelin acts on leptin-responsive neurones in the rat arcuate nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol 2002, 14, 580–586. [CrossRef]

- Holst, B.; Cygankiewicz, A.; Jensen, T.H.; Ankersen, M.; Schwartz, T.W. High constitutive signaling of the ghrelin receptor--identification of a potent inverse agonist. Mol Endocrinol 2003, 17, 2201–2210. [CrossRef]

- Holst, B.; Mokrosinski, J.; Lang, M.; Brandt, E.; Nygaard, R.; Frimurer, T.M.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G.; Schwartz, T.W. Identification of an efficacy switch region in the ghrelin receptor responsible for interchange between agonism and inverse agonism. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 15799–15811. [CrossRef]

- Dhurandhar, E.J.; Allison, D.B.; van Groen, T.; Kadish, I. Hunger in the absence of caloric restriction improves cognition and attenuates Alzheimer’s disease pathology in a mouse model. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60437. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, V.; Ryu, S.Y.; Blow, C.; Costantini, T.; Loomis, W.; Eliceiri, B.; Baird, A.; Wolf, P.; Coimbra, R. The hormone ghrelin prevents traumatic brain injury induced intestinal dysfunction. J Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 2255–2260. [CrossRef]

- Delhanty, P.J.; Huisman, M.; Baldeon-Rojas, L.Y.; van den Berge, I.; Grefhorst, A.; Abribat, T.; Leenen, P.J.; Themmen, A.P.; van der Lely, A.J. Des-acyl ghrelin analogs prevent high-fat-diet-induced dysregulation of glucose homeostasis. FASEB J 2013, 27, 1690–1700. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.; Wei, Q.; Wang, H.; Kim, D.M.; Balderas, M.; Wu, G.; Lawler, J.; Safe, S.; Guo, S.; Devaraj, S.; et al. Protective Effects of Ghrelin on Fasting-Induced Muscle Atrophy in Aging Mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020, 75, 621–630. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, N.N.; de Oliveira, M.V.; Braga, C.L.; Guimaraes, G.; Maia, L.A.; Padilha, G.A.; Silva, J.D.; Takiya, C.M.; Capelozzi, V.L.; Silva, P.L.; et al. Ghrelin therapy improves lung and cardiovascular function in experimental emphysema. Respir Res 2017, 18, 185. [CrossRef]

- Chorny, A.; Anderson, P.; Gonzalez-Rey, E.; Delgado, M. Ghrelin protects against experimental sepsis by inhibiting high-mobility group box 1 release and by killing bacteria. J Immunol 2008, 180, 8369–8377. [CrossRef]

- Makki, K.; Froguel, P.; Wolowczuk, I. Adipose tissue in obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance: cells, cytokines, and chemokines. ISRN Inflamm 2013, 2013, 139239. [CrossRef]

- Granado, M.; Priego, T.; Martin, A.I.; Villanua, M.A.; Lopez-Calderon, A. Anti-inflammatory effect of the ghrelin agonist growth hormone-releasing peptide-2 (GHRP-2) in arthritic rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005, 288, E486–492. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.D.; Schaffer, E.M.; Pyle, R.S.; Collins, G.D.; Sakthivel, S.K.; Palaniappan, R.; Lillard, J.W., Jr.; Taub, D.D. Ghrelin inhibits leptin- and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. J Clin Invest 2004, 114, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Waseem, T.; Duxbury, M.; Ito, H.; Ashley, S.W.; Robinson, M.K. Exogenous ghrelin modulates release of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated macrophages through distinct signaling pathways. Surgery 2008, 143, 334–342. [CrossRef]

- Kizaki, T.; Maegawa, T.; Sakurai, T.; Ogasawara, J.E.; Ookawara, T.; Oh-ishi, S.; Izawa, T.; Haga, S.; Ohno, H. Voluntary exercise attenuates obesity-associated inflammation through ghrelin expressed in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 413, 454–459. [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Noor, S.; Menzel, A.; Dosa, A.; Pivina, L.; Bjorklund, G. Obesity and Insulin Resistance: Associations with Chronic Inflammation, Genetic and Epigenetic Factors. Curr Med Chem 2021, 28, 800–826. [CrossRef]

- Bustin, M. Regulation of DNA-dependent activities by the functional motifs of the high-mobility-group chromosomal proteins. Mol Cell Biol 1999, 19, 5237–5246. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Livesey, K.M.; Cheh, C.W.; Farkas, A.; Loughran, P.; Hoppe, G.; Bianchi, M.E.; Tracey, K.J.; Zeh, H.J., 3rd; et al. Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J Cell Biol 2010, 190, 881–892. [CrossRef]

- Bonaldi, T.; Talamo, F.; Scaffidi, P.; Ferrera, D.; Porto, A.; Bachi, A.; Rubartelli, A.; Agresti, A.; Bianchi, M.E. Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J 2003, 22, 5551–5560. [CrossRef]

- Klune, J.R.; Dhupar, R.; Cardinal, J.; Billiar, T.R.; Tsung, A. HMGB1: endogenous danger signaling. Mol Med 2008, 14, 476–484. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Vishnubhakat, J.M.; Bloom, O.; Zhang, M.; Ombrellino, M.; Sama, A.; Tracey, K.J. Proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1) stimulate release of high mobility group protein-1 by pituicytes. Surgery 1999, 126, 389–392.

- Andersson, U.; Wang, H.; Palmblad, K.; Aveberger, A.C.; Bloom, O.; Erlandsson-Harris, H.; Janson, A.; Kokkola, R.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; et al. High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J Exp Med 2000, 192, 565–570. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bloom, O.; Zhang, M.; Vishnubhakat, J.M.; Ombrellino, M.; Che, J.; Frazier, A.; Yang, H.; Ivanova, S.; Borovikova, L.; et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 1999, 285, 248–251. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Landrock, D.; Noh, J.Y.; Zang, Q.S.; Lee, C.H.; Farnell, Y.Z.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Y. Fructose induces inflammatory activation in macrophages and microglia through the nutrient-sensing ghrelin receptor. FASEB J 2025, 39, e70412. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.M.; Lee, J.H.; Pan, Q.; Han, H.W.; Shen, Z.; Eshghjoo, S.; Wu, C.S.; Yang, W.; Noh, J.Y.; Threadgill, D.W.; et al. Nutrient-sensing growth hormone secretagogue receptor in macrophage programming and meta-inflammation. Mol Metab 2024, 79, 101852. [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Gao, M.; Yang, P.; Liu, D.; Wang, D.; Song, F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. Insulin promotes macrophage phenotype transition through PI3K/Akt and PPAR-gamma signaling during diabetic wound healing. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 4217–4231. [CrossRef]

- Mauer, J.; Chaurasia, B.; Plum, L.; Quast, T.; Hampel, B.; Bluher, M.; Kolanus, W.; Kahn, C.R.; Bruning, J.C. Myeloid cell-restricted insulin receptor deficiency protects against obesity-induced inflammation and systemic insulin resistance. PLoS Genet 2010, 6, e1000938. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartl, J.; Baudler, S.; Scherner, M.; Babaev, V.; Makowski, L.; Suttles, J.; McDuffie, M.; Tobe, K.; Kadowaki, T.; Fazio, S.; et al. Myeloid lineage cell-restricted insulin resistance protects apolipoproteinE-deficient mice against atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 247–256. [CrossRef]

- Knuever, J.; Willenborg, S.; Ding, X.; Akyuz, M.D.; Partridge, L.; Niessen, C.M.; Bruning, J.C.; Eming, S.A. Myeloid Cell-Restricted Insulin/IGF-1 Receptor Deficiency Protects against Skin Inflammation. J Immunol 2015, 195, 5296–5308. [CrossRef]

- Rached, M.T.; Millership, S.J.; Pedroni, S.M.A.; Choudhury, A.I.; Costa, A.S.H.; Hardy, D.G.; Glegola, J.A.; Irvine, E.E.; Selman, C.; Woodberry, M.C.; et al. Deletion of myeloid IRS2 enhances adipose tissue sympathetic nerve function and limits obesity. Mol Metab 2019, 20, 38–50. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, K.T.; Wiesbrock, S.M.; Marino, M.W.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Nature 1997, 389, 610–614. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Barnes, G.T.; Yang, Q.; Tan, G.; Yang, D.; Chou, C.J.; Sole, J.; Nichols, A.; Ross, J.S.; Tartaglia, L.A.; et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2003, 112, 1821–1830. [CrossRef]

- McGarry, J.D. Banting lecture 2001: dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 7–18. [CrossRef]

- Sachithanandan, N.; Graham, K.L.; Galic, S.; Honeyman, J.E.; Fynch, S.L.; Hewitt, K.A.; Steinberg, G.R.; Kay, T.W. Macrophage deletion of SOCS1 increases sensitivity to LPS and palmitic acid and results in systemic inflammation and hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2023–2031. [CrossRef]

- Czaja, A.J.; Manns, M.P. Advances in the diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 58–72 e54. [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Boege, Y.; Reisinger, F.; Heikenwalder, M. Chronic liver inflammation and hepatocellular carcinoma: persistence matters. Swiss Med Wkly 2011, 141, w13197. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, P.; Lee, C.H. Role and function of macrophages in the metabolic syndrome. Biochem J 2012, 442, 253–262. [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A.; Barron, L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis 2010, 30, 245–257. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, M.M.; Wang, K.; Adler, A.J.; Vella, A.T.; Zhou, B. Macrophage polarization and meta-inflammation. Transl Res 2018, 191, 29–44. [CrossRef]

- Hertzel, A.V.; Yong, J.; Chen, X.; Bernlohr, D.A. Immune Modulation of Adipocyte Mitochondrial Metabolism. Endocrinology 2022, 163. [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.D.; Kincaid, K.; Alt, J.M.; Heilman, M.J.; Hill, A.M. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol 2000, 164, 6166–6173. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep 2014, 6, 13. [CrossRef]

- Nahrendorf, M.; Swirski, F.K. Abandoning M1/M2 for a Network Model of Macrophage Function. Circ Res 2016, 119, 414–417. [CrossRef]

- Bleriot, C.; Chakarov, S.; Ginhoux, F. Determinants of Resident Tissue Macrophage Identity and Function. Immunity 2020, 52, 957–970. [CrossRef]

- Mulder, K.; Patel, A.A.; Kong, W.T.; Piot, C.; Halitzki, E.; Dunsmore, G.; Khalilnezhad, S.; Irac, S.E.; Dubuisson, A.; Chevrier, M.; et al. Cross-tissue single-cell landscape of human monocytes and macrophages in health and disease. Immunity 2021, 54, 1883–1900 e1885. [CrossRef]

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol 2008, 8, 958–969. [CrossRef]

- Guilliams, M.; Thierry, G.R.; Bonnardel, J.; Bajenoff, M. Establishment and Maintenance of the Macrophage Niche. Immunity 2020, 52, 434–451. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.Y.; Black, A.; Qian, B.Z. Macrophage diversity in cancer revisited in the era of single-cell omics. Trends Immunol 2022, 43, 546–563. [CrossRef]

- Tschop, M.; Lahner, H.; Feldmeier, H.; Grasberger, H.; Morrison, K.M.; Janssen, O.E.; Attanasio, A.F.; Strasburger, C.J. Effects of growth hormone replacement therapy on levels of cortisol and cortisol-binding globulin in hypopituitary adults. Eur J Endocrinol 2000, 143, 769–773. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Zheng, H.; Smith, R.G. Ghrelin stimulation of growth hormone release and appetite is mediated through the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 4679–4684. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Nuotio-Antar, A.M.; Ma, X.; Liu, F.; Fiorotto, M.L.; Sun, Y. Ghrelin receptor regulates appetite and satiety during aging in mice by regulating meal frequency and portion size but not total food intake. J Nutr 2014, 144, 1349–1355. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Saha, P.K.; Ma, X.; Henshaw, I.O.; Shao, L.; Chang, B.H.; Buras, E.D.; Tong, Q.; Chan, L.; McGuinness, O.P.; et al. Ablation of ghrelin receptor reduces adiposity and improves insulin sensitivity during aging by regulating fat metabolism in white and brown adipose tissues. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 996–1010. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Lee, J.H.; Buras, E.D.; Yu, K.; Wang, R.; Smith, C.W.; Wu, H.; Sheikh-Hamad, D.; Sun, Y. Ghrelin receptor regulates adipose tissue inflammation in aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 178–191. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lin, L.; Yue, J.; Pradhan, G.; Qin, G.; Minze, L.J.; Wu, H.; Sheikh-Hamad, D.; Smith, C.W.; Sun, Y. Ghrelin receptor regulates HFCS-induced adipose inflammation and insulin resistance. Nutr Diabetes 2013, 3, e99. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Ma, J.; Xiang, X.; Lan, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Improvement of Adipose Macrophage Polarization in High Fat Diet-Induced Obese GHSR Knockout Mice. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 4924325. [CrossRef]

- Holst, B.; Holliday, N.D.; Bach, A.; Elling, C.E.; Cox, H.M.; Schwartz, T.W. Common structural basis for constitutive activity of the ghrelin receptor family. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 53806–53817. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, P.S.; Woldbye, D.P.; Madsen, A.N.; Egerod, K.L.; Jin, C.; Lang, M.; Rasmussen, M.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G.; Holst, B. In vivo characterization of high Basal signaling from the ghrelin receptor. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 4920–4930. [CrossRef]

- Tanida, R.; Tsubouchi, H.; Yanagi, S.; Saito, Y.; Toshinai, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Takamura, T.; Nakazato, M. GHS-R1a deficiency mitigates lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mice via the downregulation of macrophage activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022, 589, 260–266. [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.Y.; Herrera, M.; Patil, B.S.; Tan, X.D.; Wright, G.A.; Sun, Y. The expression and function of growth hormone secretagogue receptor in immune cells: A current perspective. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2022, 247, 2184–2191. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Kim, M.S. Molecular mechanisms of appetite regulation. Diabetes Metab J 2012, 36, 391–398. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.M.; Yu, H.; Palyha, O.C.; McKee, K.K.; Feighner, S.D.; Sirinathsinghji, D.J.; Smith, R.G.; Van der Ploeg, L.H.; Howard, A.D. Distribution of mRNA encoding the growth hormone secretagogue receptor in brain and peripheral tissues. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1997, 48, 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, H.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Lean mean fat reducing “ghrelin” machine: hypothalamic ghrelin and ghrelin receptors as therapeutic targets in obesity. Neuropharmacology 2010, 58, 2–16. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.T.; Kola, B.; Korbonits, M. The ghrelin/GOAT/GHS-R system and energy metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2011, 12, 173–186. [CrossRef]

- Gnanapavan, S.; Kola, B.; Bustin, S.A.; Morris, D.G.; McGee, P.; Fairclough, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carpenter, R.; Grossman, A.B.; Korbonits, M. The tissue distribution of the mRNA of ghrelin and subtypes of its receptor, GHS-R, in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002, 87, 2988. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.T.; Luo, Q. Molecular Mechanisms and Health Benefits of Ghrelin: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.K.; Schwartz, G.J.; Rossetti, L. Hypothalamic sensing of fatty acids. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8, 579–584. [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Lam, T.K.; Obici, S.; Rossetti, L. Molecular disruption of hypothalamic nutrient sensing induces obesity. Nat Neurosci 2006, 9, 227–233. [CrossRef]

- Obici, S.; Feng, Z.; Arduini, A.; Conti, R.; Rossetti, L. Inhibition of hypothalamic carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 decreases food intake and glucose production. Nat Med 2003, 9, 756–761. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kerner, J.; Hoppel, C.L. Mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (CPT1a) is part of an outer membrane fatty acid transfer complex. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 25655–25662. [CrossRef]

- Schlaepfer, I.R.; Joshi, M. CPT1A-mediated Fat Oxidation, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Endocrinology 2020, 161. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Z.B.; Liu, Z.W.; Walllingford, N.; Erion, D.M.; Borok, E.; Friedman, J.M.; Tschop, M.H.; Shanabrough, M.; Cline, G.; Shulman, G.I.; et al. UCP2 mediates ghrelin’s action on NPY/AgRP neurons by lowering free radicals. Nature 2008, 454, 846–851. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Trumbauer, M.E.; Chen, A.S.; Weingarth, D.T.; Adams, J.R.; Frazier, E.G.; Shen, Z.; Marsh, D.J.; Feighner, S.D.; Guan, X.M.; et al. Orexigenic action of peripheral ghrelin is mediated by neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 2607–2612. [CrossRef]

- Horvath, T.L.; Naftolin, F.; Kalra, S.P.; Leranth, C. Neuropeptide-Y innervation of beta-endorphin-containing cells in the rat mediobasal hypothalamus: a light and electron microscopic double immunostaining analysis. Endocrinology 1992, 131, 2461–2467. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, N.E.; Krzyzaniak, M.J.; Blow, C.; Putnam, J.; Ortiz-Pomales, Y.; Hageny, A.M.; Eliceiri, B.; Coimbra, R.; Bansal, V. Ghrelin prevents disruption of the blood-brain barrier after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 385–393. [CrossRef]

- Raghay, K.; Akki, R.; Bensaid, D.; Errami, M. Ghrelin as an anti-inflammatory and protective agent in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Peptides 2020, 124, 170226. [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.M.; Taher, M.; Chin, K.Y.; Barsby, T.; Austin, V.; Wong, C.H.; Andrews, Z.B.; Spencer, S.J.; Miller, A.A. Protective actions of des-acylated ghrelin on brain injury and blood-brain barrier disruption after stroke in mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016, 130, 1545–1558. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Xia, Q.; Hou, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhu, S. Ghrelin protects cortical neuron against focal ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 359, 795–800. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Hu, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, P.; Jiang, X. Ghrelin Ameliorates Traumatic Brain Injury by Down-Regulating bFGF and FGF-BP. Front Neurosci 2018, 12, 445. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Lei, P.; Zhang, Q. Ghrelin attenuates brain injury in septic mice via PI3K/Akt signaling activation. Brain Res Bull 2016, 124, 278–285. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wei, X.; Hou, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Sun, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, H. Tetramethylpyrazine analogue CXC195 protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis through PI3K/Akt/GSK3beta pathway in rats. Neurochem Int 2014, 66, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Shao, A.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Wu, H.; McBride, D.W.; Wu, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J. Neuroprotective effect of hydrogen-rich saline against neurologic damage and apoptosis in early brain injury following subarachnoid hemorrhage: possible role of the Akt/GSK3beta signaling pathway. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96212. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Ding, R.; Lv, S.; Ji, X. The Pathologic Roles and Therapeutic Implications of Ghrelin/GHSR System in Mental Disorders. Depress Anxiety 2024, 2024, 5537319. [CrossRef]

- Lutter, M.; Sakata, I.; Osborne-Lawrence, S.; Rovinsky, S.A.; Anderson, J.G.; Jung, S.; Birnbaum, S.; Yanagisawa, M.; Elmquist, J.K.; Nestler, E.J.; et al. The orexigenic hormone ghrelin defends against depressive symptoms of chronic stress. Nat Neurosci 2008, 11, 752–753. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, K.; Akiyoshi, J.; Hatano, K.; Hanada, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Tsuru, J.; Matsushita, H.; Kodama, K.; Isogawa, K. Ghrelin gene polymorphism is associated with depression, but not panic disorder. Psychiatr Genet 2008, 18, 257. [CrossRef]

- Yohn, C.N.; Gergues, M.M.; Samuels, B.A. The role of 5-HT receptors in depression. Mol Brain 2017, 10, 28. [CrossRef]

- Samuels, B.A.; Leonardo, E.D.; Gadient, R.; Williams, A.; Zhou, J.; David, D.J.; Gardier, A.M.; Wong, E.H.; Hen, R. Modeling treatment-resistant depression. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 408–413. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zhu, G. Associations Among Monoamine Neurotransmitter Pathways, Personality Traits, and Major Depressive Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 381. [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.; Gomez, R.; Williams, G.; Lembke, A.; Lazzeroni, L.; Murphy, G.M., Jr.; Schatzberg, A.F. HPA axis in major depression: cortisol, clinical symptomatology and genetic variation predict cognition. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 527–536. [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Altered Connectivity in Depression: GABA and Glutamate Neurotransmitter Deficits and Reversal by Novel Treatments. Neuron 2019, 102, 75–90. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ma, L.; Kaarela, T.; Li, Z. Neuroimmune crosstalk in the central nervous system and its significance for neurological diseases. J Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 155. [CrossRef]

- Vreeburg, S.A.; Hoogendijk, W.J.; van Pelt, J.; Derijk, R.H.; Verhagen, J.C.; van Dyck, R.; Smit, J.H.; Zitman, F.G.; Penninx, B.W. Major depressive disorder and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: results from a large cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009, 66, 617–626. [CrossRef]

- Vreeburg, S.A.; Zitman, F.G.; van Pelt, J.; Derijk, R.H.; Verhagen, J.C.; van Dyck, R.; Hoogendijk, W.J.; Smit, J.H.; Penninx, B.W. Salivary cortisol levels in persons with and without different anxiety disorders. Psychosom Med 2010, 72, 340–347. [CrossRef]

- Kluge, M.; Schussler, P.; Dresler, M.; Schmidt, D.; Yassouridis, A.; Uhr, M.; Steiger, A. Effects of ghrelin on psychopathology, sleep and secretion of cortisol and growth hormone in patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2011, 45, 421–426. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.J.; Xu, L.; Clarke, M.A.; Lemus, M.; Reichenbach, A.; Geenen, B.; Kozicz, T.; Andrews, Z.B. Ghrelin regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and restricts anxiety after acute stress. Biol Psychiatry 2012, 72, 457–465. [CrossRef]

- Rucinski, M.; Ziolkowska, A.; Szyszka, M.; Hochol, A.; Malendowicz, L.K. Evidence suggesting that ghrelin O-acyl transferase inhibitor acts at the hypothalamus to inhibit hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis function in the rat. Peptides 2012, 35, 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Kluge, M.; Gazea, M.; Schussler, P.; Genzel, L.; Dresler, M.; Kleyer, S.; Uhr, M.; Yassouridis, A.; Steiger, A. Ghrelin increases slow wave sleep and stage 2 sleep and decreases stage 1 sleep and REM sleep in elderly men but does not affect sleep in elderly women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 297–304. [CrossRef]

- Olivier, N.; Harvey, B.H.; Gobec, S.; Shahid, M.; Kosak, U.; Zakelj, S.; Brink, C.B. A novel butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor induces antidepressant, pro-cognitive, and anti-anhedonic effects in Flinders Sensitive Line rats: The role of the ghrelin-dopamine cascade. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 187, 118093. [CrossRef]

- Belujon, P.; Grace, A.A. Dopamine System Dysregulation in Major Depressive Disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017, 20, 1036–1046. [CrossRef]

- Mifune, H.; Tajiri, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Kawahara, Y.; Hara, K.; Sato, T.; Nishi, Y.; Nishi, A.; Mitsuzono, R.; Kakuma, T.; et al. Voluntary exercise is motivated by ghrelin, possibly related to the central reward circuit. J Endocrinol 2020, 244, 123–132. [CrossRef]

- Abizaid, A. Ghrelin and dopamine: new insights on the peripheral regulation of appetite. J Neuroendocrinol 2009, 21, 787–793. [CrossRef]

- Abizaid, A.; Liu, Z.W.; Andrews, Z.B.; Shanabrough, M.; Borok, E.; Elsworth, J.D.; Roth, R.H.; Sleeman, M.W.; Picciotto, M.R.; Tschop, M.H.; et al. Ghrelin modulates the activity and synaptic input organization of midbrain dopamine neurons while promoting appetite. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 3229–3239. [CrossRef]

- Jerlhag, E.; Egecioglu, E.; Dickson, S.L.; Andersson, M.; Svensson, L.; Engel, J.A. Ghrelin stimulates locomotor activity and accumbal dopamine-overflow via central cholinergic systems in mice: implications for its involvement in brain reward. Addict Biol 2006, 11, 45–54. [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, C.E.; Vestlund, J.; Jerlhag, E. A ghrelin receptor antagonist reduces the ability of ghrelin, alcohol or amphetamine to induce a dopamine release in the ventral tegmental area and in nucleus accumbens shell in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2021, 899, 174039. [CrossRef]

- Ghersi, M.S.; Casas, S.M.; Escudero, C.; Carlini, V.P.; Buteler, F.; Cabrera, R.J.; Schioth, H.B.; de Barioglio, S.R. Ghrelin inhibited serotonin release from hippocampal slices. Peptides 2011, 32, 2367–2371. [CrossRef]

- Cerit, H.; Christensen, K.; Moondra, P.; Klibanski, A.; Goldstein, J.M.; Holsen, L.M. Divergent associations between ghrelin and neural responsivity to palatable food in hyperphagic and hypophagic depression. J Affect Disord 2019, 242, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Mequinion, M.; Foldi, C.J.; Andrews, Z.B. The Ghrelin-AgRP Neuron Nexus in Anorexia Nervosa: Implications for Metabolic and Behavioral Adaptations. Front Nutr 2019, 6, 190. [CrossRef]

- Dehkhoda, F.; Ringuet, M.T.; Whitfield, E.A.; Mutunduwe, K.; Whelan, F.; Nowell, C.J.; Misganaw, D.; Xu, Z.; Piper, N.B.C.; Clark, R.J.; et al. Constitutive ghrelin receptor activity enables reversal of dopamine D2 receptor signaling. Mol Cell 2025, 85, 2246–2260 e2210. [CrossRef]

- Furness, J.B.; Hunne, B.; Matsuda, N.; Yin, L.; Russo, D.; Kato, I.; Fujimiya, M.; Patterson, M.; McLeod, J.; Andrews, Z.B.; et al. Investigation of the presence of ghrelin in the central nervous system of the rat and mouse. Neuroscience 2011, 193, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Ratner, C.; Rudenko, O.; Christiansen, S.H.; Skov, L.J.; Hundahl, C.; Woldbye, D.P.; Holst, B. Anxiolytic-Like Effects of Increased Ghrelin Receptor Signaling in the Amygdala. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2016, 19. [CrossRef]

- Espelund, U.; Hansen, T.K.; Hojlund, K.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Clausen, J.T.; Hansen, B.S.; Orskov, H.; Jorgensen, J.O.; Frystyk, J. Fasting unmasks a strong inverse association between ghrelin and cortisol in serum: studies in obese and normal-weight subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005, 90, 741–746. [CrossRef]

- Schuessler, P.; Uhr, M.; Ising, M.; Schmid, D.; Weikel, J.; Steiger, A. Nocturnal ghrelin levels--relationship to sleep EEG, the levels of growth hormone, ACTH and cortisol--and gender differences. J Sleep Res 2005, 14, 329–336. [CrossRef]

- Buntwal, L.; Sassi, M.; Morgan, A.H.; Andrews, Z.B.; Davies, J.S. Ghrelin-Mediated Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Implications for Health and Disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2019, 30, 844–859. [CrossRef]

- Numakawa, T.; Odaka, H.; Adachi, N. Actions of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Glucocorticoid Stress in Neurogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [CrossRef]

- Price, M.L.; Ley, C.D.; Gorvin, C.M. The emerging role of heterodimerisation and interacting proteins in ghrelin receptor function. J Endocrinol 2021, 252, R23–R39. [CrossRef]

- Kern, A.; Mavrikaki, M.; Ullrich, C.; Albarran-Zeckler, R.; Brantley, A.F.; Smith, R.G. Hippocampal Dopamine/DRD1 Signaling Dependent on the Ghrelin Receptor. Cell 2015, 163, 1176–1190. [CrossRef]

- Ricken, R.; Bopp, S.; Schlattmann, P.; Himmerich, H.; Bschor, T.; Richter, C.; Elstner, S.; Stamm, T.J.; Schulz-Ratei, B.; Lingesleben, A.; et al. Ghrelin Serum Concentrations Are Associated with Treatment Response During Lithium Augmentation of Antidepressants. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017, 20, 692–697. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.L.; Chen, M.H.; Hsu, J.W.; Tsai, S.J.; Bai, Y.M. Using classification and regression tree modeling to investigate appetite hormones and proinflammatory cytokines as biomarkers to differentiate bipolar I depression from major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr 2021, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Aziz, K.; Al-Mugaddam, F.; Sugathan, S.; Saseedharan, P.; Jouini, T.; Elamin, M.E.; Moselhy, H.; Aly El-Gabry, D.; Arnone, D.; Karam, S.M. Decreased acylated and total ghrelin levels in bipolar disorder patients recovering from a manic episode. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 209. [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, A.; Metallinos, I.C.; Psyrogiannis, A.; Vagenakis, G.A.; Kyriazopoulou, V. Ghrelin and leptin secretion in patients with moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging 2012, 16, 472–477. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhu, M.; He, Y.; Chu, W.; Du, Y.; Du, H. Increased Serum Acylated Ghrelin Levels in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 61, 545–552. [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, Y.; Funahashi, Y.; Nakata, S.; Ozaki, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Yoshida, T.; Mori, T.; Mori, Y.; Ochi, S.; Iga, J.I.; et al. Ghrelin cascade changes in the peripheral blood of Japanese patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Psychiatr Res 2018, 107, 79–85. [CrossRef]

- Gahete, M.D.; Rubio, A.; Cordoba-Chacon, J.; Gracia-Navarro, F.; Kineman, R.D.; Avila, J.; Luque, R.M.; Castano, J.P. Expression of the ghrelin and neurotensin systems is altered in the temporal lobe of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 22, 819–828. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Guo, L.; Sui, S.; Driskill, C.; Phensy, A.; Wang, Q.; Gauba, E.; Zigman, J.M.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Kroener, S.; et al. Disrupted hippocampal growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1alpha interaction with dopamine receptor D1 plays a role in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.G.; Van der Ploeg, L.H.; Howard, A.D.; Feighner, S.D.; Cheng, K.; Hickey, G.J.; Wyvratt, M.J., Jr.; Fisher, M.H.; Nargund, R.P.; Patchett, A.A. Peptidomimetic regulation of growth hormone secretion. Endocr Rev 1997, 18, 621–645. [CrossRef]

- M’Kadmi, C.; Cabral, A.; Barrile, F.; Giribaldi, J.; Cantel, S.; Damian, M.; Mary, S.; Denoyelle, S.; Dutertre, S.; Peraldi-Roux, S.; et al. N-Terminal Liver-Expressed Antimicrobial Peptide 2 (LEAP2) Region Exhibits Inverse Agonist Activity toward the Ghrelin Receptor. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 965–973. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimpour, S.; Zakeri, M.; Esmaeili, A. Crosstalk between obesity, diabetes, and alzheimer’s disease: Introducing quercetin as an effective triple herbal medicine. Ageing Res Rev 2020, 62, 101095. [CrossRef]

- Popelova, A.; Kakonova, A.; Hruba, L.; Kunes, J.; Maletinska, L.; Zelezna, B. Potential neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic properties of a long-lasting stable analog of ghrelin: an in vitro study using SH-SY5Y cells. Physiol Res 2018, 67, 339–346. [CrossRef]

- Mengr, A.; Smotkova, Z.; Pacesova, A.; Zelezna, B.; Kunes, J.; Maletinska, L. Reduction of Neuroinflammation as a Common Mechanism of Action of Anorexigenic and Orexigenic Peptide Analogues in the Triple Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer s Disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2025, 20, 18. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.J.; Liang, G.; Li, R.L.; Xie, X.; Sleeman, M.W.; Murphy, A.J.; Valenzuela, D.M.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. Ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) is essential for growth hormone-mediated survival of calorie-restricted mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 7467–7472. [CrossRef]

- Rasineni, K.; Thomes, P.G.; Kubik, J.L.; Harris, E.N.; Kharbanda, K.K.; Casey, C.A. Chronic alcohol exposure alters circulating insulin and ghrelin levels: role of ghrelin in hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2019, 316, G453–G461. [CrossRef]

- Landgren, S.; Engel, J.A.; Hyytia, P.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Jerlhag, E. Expression of the gene encoding the ghrelin receptor in rats selected for differential alcohol preference. Behav Brain Res 2011, 221, 182–188. [CrossRef]

- Ryabinin, A.E.; Cocking, D.L.; Kaur, S. Inhibition of VTA neurons activates the centrally projecting Edinger-Westphal nucleus: evidence of a stress-reward link? J Chem Neuroanat 2013, 54, 57–61. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Engel, J.A. Neurochemical and behavioral studies on ethanol and nicotine interactions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2004, 27, 713–720. [CrossRef]

- Suchankova, P.; Steensland, P.; Fredriksson, I.; Engel, J.A.; Jerlhag, E. Ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1A) antagonism suppresses both alcohol consumption and the alcohol deprivation effect in rats following long-term voluntary alcohol consumption. PLoS One 2013, 8, e71284. [CrossRef]

- Jerlhag, E.; Landgren, S.; Egecioglu, E.; Dickson, S.L.; Engel, J.A. The alcohol-induced locomotor stimulation and accumbal dopamine release is suppressed in ghrelin knockout mice. Alcohol 2011, 45, 341–347. [CrossRef]

- Loonen, A.J.; Ivanova, S.A. Circuits Regulating Pleasure and Happiness: The Evolution of the Amygdalar-Hippocampal-Habenular Connectivity in Vertebrates. Front Neurosci 2016, 10, 539. [CrossRef]

- Jerlhag, E.; Egecioglu, E.; Landgren, S.; Salome, N.; Heilig, M.; Moechars, D.; Datta, R.; Perrissoud, D.; Dickson, S.L.; Engel, J.A. Requirement of central ghrelin signaling for alcohol reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 11318–11323. [CrossRef]

- Zallar, L.J.; Beurmann, S.; Tunstall, B.J.; Fraser, C.M.; Koob, G.F.; Vendruscolo, L.F.; Leggio, L. Ghrelin receptor deletion reduces binge-like alcohol drinking in rats. J Neuroendocrinol 2019, 31, e12663. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, K.; Nagao, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ueda, S.; Kitamura, Y.; Nishimura, K.; Inden, M.; Marunaka, Y.; Hattori, H.; et al. Enhanced alcohol-drinking behavior associated with active ghrelinergic and serotoninergic neurons in the lateral hypothalamus and amygdala. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2017, 153, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, E.R.; Cordisco Gonzalez, S.; Damian, M.; Cantel, S.; Denoyelle, S.; Wagner, R.; Schioth, H.B.; Fehrentz, J.A.; Baneres, J.L.; Perello, M.; et al. LEAP2 Impairs the Capability of the Growth Hormone Secretagogue Receptor to Regulate the Dopamine 2 Receptor Signaling. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 712437. [CrossRef]

- Jerlhag, E.; Egecioglu, E.; Dickson, S.L.; Engel, J.A. Ghrelin receptor antagonism attenuates cocaine- and amphetamine-induced locomotor stimulation, accumbal dopamine release, and conditioned place preference. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010, 211, 415–422. [CrossRef]

- Palotai, M.; Bagosi, Z.; Jaszberenyi, M.; Csabafi, K.; Dochnal, R.; Manczinger, M.; Telegdy, G.; Szabo, G. Ghrelin amplifies the nicotine-induced dopamine release in the rat striatum. Neurochem Int 2013, 63, 239–243. [CrossRef]

- Jerabek, P.; Havlickova, T.; Puskina, N.; Charalambous, C.; Lapka, M.; Kacer, P.; Sustkova-Fiserova, M. Ghrelin receptor antagonism of morphine-induced conditioned place preference and behavioral and accumbens dopaminergic sensitization in rats. Neurochem Int 2017, 110, 101–113. [CrossRef]

- Sustkova-Fiserova, M.; Puskina, N.; Havlickova, T.; Lapka, M.; Syslova, K.; Pohorala, V.; Charalambous, C. Ghrelin receptor antagonism of fentanyl-induced conditioned place preference, intravenous self-administration, and dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in rats. Addict Biol 2020, 25, e12845. [CrossRef]

- You, Z.B.; Galaj, E.; Alen, F.; Wang, B.; Bi, G.H.; Moore, A.R.; Buck, T.; Crissman, M.; Pari, S.; Xi, Z.X.; et al. Involvement of the ghrelin system in the maintenance and reinstatement of cocaine-motivated behaviors: a role of adrenergic action at peripheral beta1 receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 1449–1460. [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, C.; Havlickova, T.; Lapka, M.; Puskina, N.; Slamberova, R.; Kuchar, M.; Sustkova-Fiserova, M. Cannabinoid-Induced Conditioned Place Preference, Intravenous Self-Administration, and Behavioral Stimulation Influenced by Ghrelin Receptor Antagonism in Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).