1. Introduction

The transportation sector accounts for approximately 29% of total European Union CO2 emissions and approximately 27% of all greenhouse gas (GHG) in the United States of America (US), making it one of the highest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions globally [

1,

2]. In response to this challenge, the European Commission's Green Deal aims to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, with the "Fit for 55" initiative targeting a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and complete elimination of gasoline and diesel engines by 2035 [

1,

3]. This regulatory framework has accelerated the global transition toward electric mobility, with China alone projecting electric vehicle production to reach 4,000 units (×10,000) by 2035, representing a 90% market share [

4]. As climate change concerns intensify and governments worldwide implement stringent emission reduction targets, the automotive industry has undergone a fundamental transformation toward electrification of vehicles. Electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a promising solution for reducing transportation-related emissions, driven by advances in battery technology, charging infrastructure, and intelligent vehicle systems [

5,

6]. The global electric vehicle market has experienced remarkable growth, with nearly 14 million new electric cars registered worldwide in 2023, increasing the total number of EVs on the road to 40 million [

7]. With zero tailpipe emissions, EVs offer a clear advantage over traditional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) during their operational phase, directly improving air quality in urban environments and contributing to national and international emission reduction targets [

8,

9].

The increasing adoption of EVs worldwide underscores their significance. Governments and industries are investing heavily in EV technology, charging infrastructure, and incentives to accelerate this transition [

10]. However, the environmental benefits of EVs are not solely determined by their road’s performance. A holistic understanding of their true environmental impact requires a comprehensive evaluation that extends from the extraction of raw materials for their components through manufacturing processes, their operational life, and ultimately to their end-of-life management, including battery recycling and disposal. This comprehensive viewpoint is crucial, as studies indicate that the production phase, especially of batteries, and the source of electricity for charging are significant factors in the overall environmental profile of an EV [

11,

12].

While the absence of tailpipe emissions during operation is a clear and immediate benefit of EVs, a truly comprehensive understanding of their environmental credentials necessitates a much broader perspective that meticulously examines the impacts across their entire lifecycle, from the mining of raw materials, to assessing the impact of the electric grid in the use phase, and to their eventual disposal or recycling. In this context, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a valuable analytical technique and an indispensable tool for informed decision-making. Without such a holistic view, conclusions regarding the environmental benefits of EVs may be incomplete or misleading, potentially overlooking significant upstream and downstream burdens.

Numerous authors have reviewed scientific literature on the life cycle assessment of electric vehicles, each concentrating on different aspects of the topic. In their review, Burchart et al. [

13] focused on the environmental LCA of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) in road transportation. This review emphasized the crucial role of hydrogen production methods in determining the overall environmental performance of FCEVs, highlighting that the use of renewable energy sources for hydrogen production is essential for achieving significant environmental benefits. Another review by Koniak et al. [

14] covered the economic, technical, and environmental aspects of electric vehicles, providing a broader context for understanding the overall sustainability of EVs compared to conventional vehicles. This integrated perspective is crucial for informed decision-making regarding the transition to electric vehicles.

In summary,

Table 1 offers an overview of the review literature, establishing a foundational understanding of the life cycle environmental impacts of electric vehicles, with a focus on their specific areas of emphasis.

1.1. Objectives of the Review

While numerous reviews have summarized the findings of EV LCA studies, a gap exists in systematically analyzing the underlying methodological frameworks that produce these results. Therefore, the primary objective of this paper is to provide a comprehensive methodological review of recent EV LCA literature. Instead of focusing solely on the outcomes, this review deconstructs how these assessments are conducted by examining the choices made by researchers at each stage of the LCA process.

The specific objectives are as follows:

Goal and Scope Definition: To analyze the technologies studied, the system boundaries applied (e.g., cradle-to-grave, well-to-wheel), and the prevalent modeling philosophies (attributional vs. consequential).

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): To identify the dominant software tools, LCI databases, and data sources used to quantify environmental inputs and outputs.

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): To compare the different impact assessment methodologies (e.g., ReCiPe, CML) employed to translate inventory data into environmental impacts.

Interpretation: To investigate how researchers address uncertainty and variability through sensitivity and scenario analyses.

The novelty of this review lies in its structured critique of the LCA process itself, offering a benchmark of current practices in the field. By comparing the tools, databases, and methodological choices, we aim to identify points of consensus, divergence, and key challenges that affect the comparability and reliability of EV LCA results. Furthermore, this review highlights a significant and under-explored research gap: the near absence of comprehensive LCA studies on Vehicle-Integrated Photovoltaics (VIPV) and solar-powered vehicles (SPV), defining a clear direction for future research in sustainable mobility.

This review is structured as follows:

Section 2 explains the materials and methods used in the literature search.

Section 3 delves into the methodological approaches, software, and impact assessment methods used in this study. It also examines the key influencing factors that drive the LCA results and discusses the sensitivity analyses performed in this regard.

Section 4 highlights significant research gaps and proposes future research directions, along with the conclusion.

2. Materials and Methods

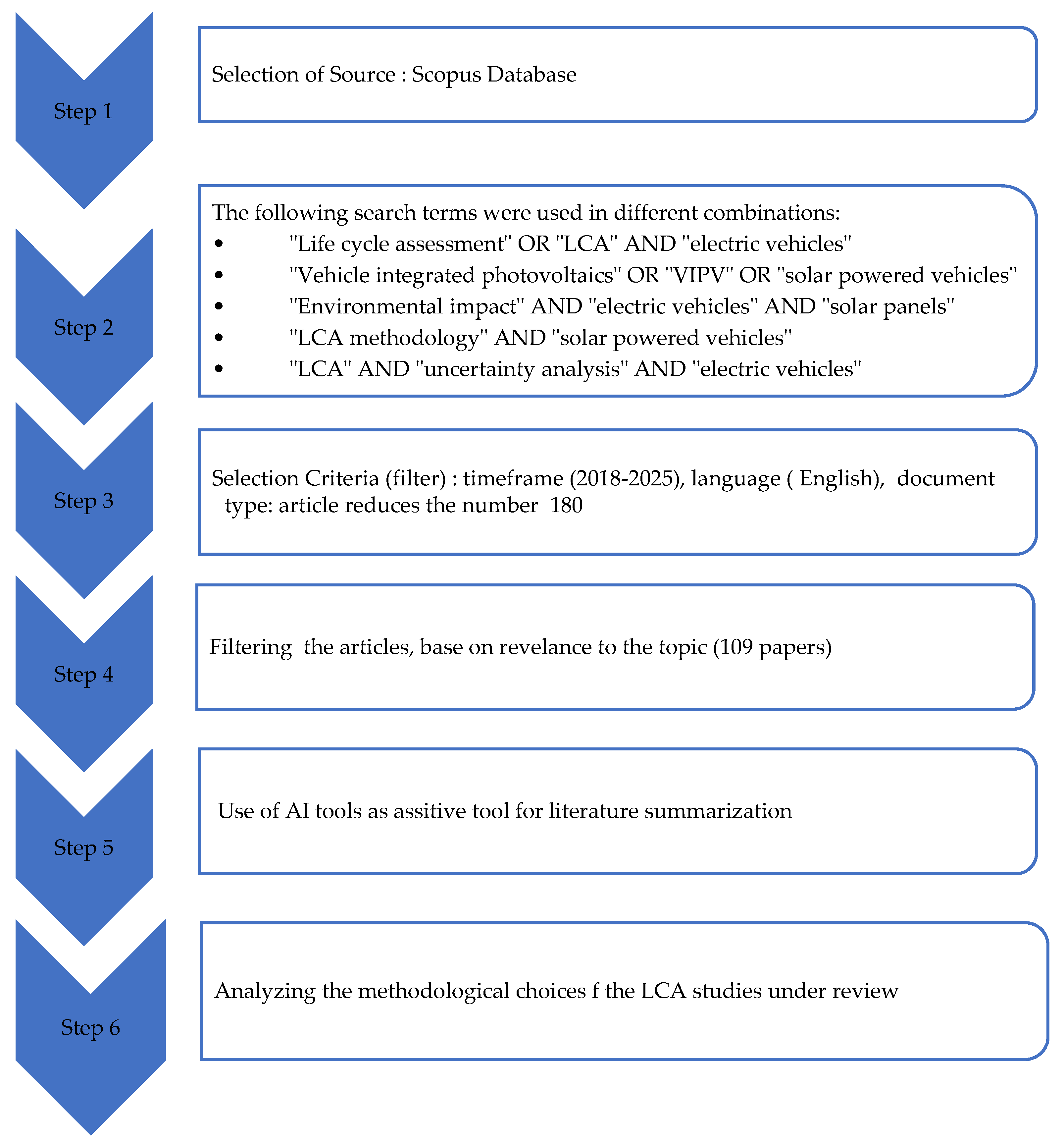

2.1. Systematic Literature Search

This review employed a systematic literature search using the Scopus database to identify relevant studies on the life cycle assessment of electric vehicles. The following search terms were used in different combinations:

"Life cycle assessment" OR "LCA" AND "electric vehicles"

"Vehicle integrated photovoltaics" OR "VIPV" OR "solar powered vehicles"

"Environmental impact" AND "electric vehicles" AND "solar panels"

"LCA methodology" AND "solar powered vehicles"

"LCA" AND "uncertainty analysis" AND "electric vehicles"

The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2018 and 2025 to capture established scientific knowledge in the field and ensure relevance to current technological developments and methodological approaches.

The initial search yielded over 500 publications, which were further screened based on titles, abstracts, and keywords to identify the most relevant studies for a detailed review. Studies focused specifically on the life cycle assessment of electric vehicles, methodological approaches to LCA, and LCA of emerging vehicle technologies such as vehicle-integrated photovoltaics were prioritized for inclusion in this review. The selection criteria emphasized studies that provided quantitative environmental impact assessments, detailed methodological descriptions, and comparative analyses of different vehicle technologies or battery systems.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) non-English language publications, (2) studies published outside the specified timeframe, (3) research focusing exclusively on battery technology without direct reference to electric vehicles, (4) conference papers and abstracts, and (5) non-peer-reviewed reports and grey literature.

The final phase involved a detailed analysis of the identified subthemes. The literature within each sub-theme was analyzed as a cluster, ultimately leading to conclusions regarding the evolution of SEVs, energy optimization, solar technology and design trends, and future perspectives. A flowchart of the selection process is shown in

Figure 1.

During this research, we acknowledge the use of Perplexity AI (Pro version) and Paperpal (Pro version) as supportive tools in the preparation of this manuscript. These AI tools were not employed to create original research content but were utilized to assist with the following tasks:

Literature Summarization: After downloading and evaluating over 101 scientific papers, Perplexity AI (Pro version) aided in extracting key insights, identifying trends, and synthesizing themes, particularly in areas related to functional units, system boundaries and the inclusion of uncertainty used in each studies.

Language and Clarity Improvement: Paperpal AI was used to refine specific sections of the manuscript, enhancing grammatical precision, technical accuracy, and overall readability, focusing on the introduction and conclusion.

Structural Critique and Feedback: Both tools served as initial reviewers, offering suggestions on the logical progression of arguments and highlighting areas of redundancy or wordiness in the draft. All feedback provided by the AI was thoroughly reviewed and edited by the authors to maintain alignment with the original source and ensure scientific integrity.

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment Mehodology

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a robust, internationally standardized (ISO 14040/14044), and systematic methodology designed to evaluate the potential environmental impacts attributable to a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle [

19,

20]. LCA enables the identification of environmental hotspots within a product's life cycle and facilitates comparisons between different products or production pathways [

21]. In the context of electric vehicles, LCA has been widely applied to assess various environmental impacts, including greenhouse gas emissions, resource depletion, acidification, and human toxicity [

21,

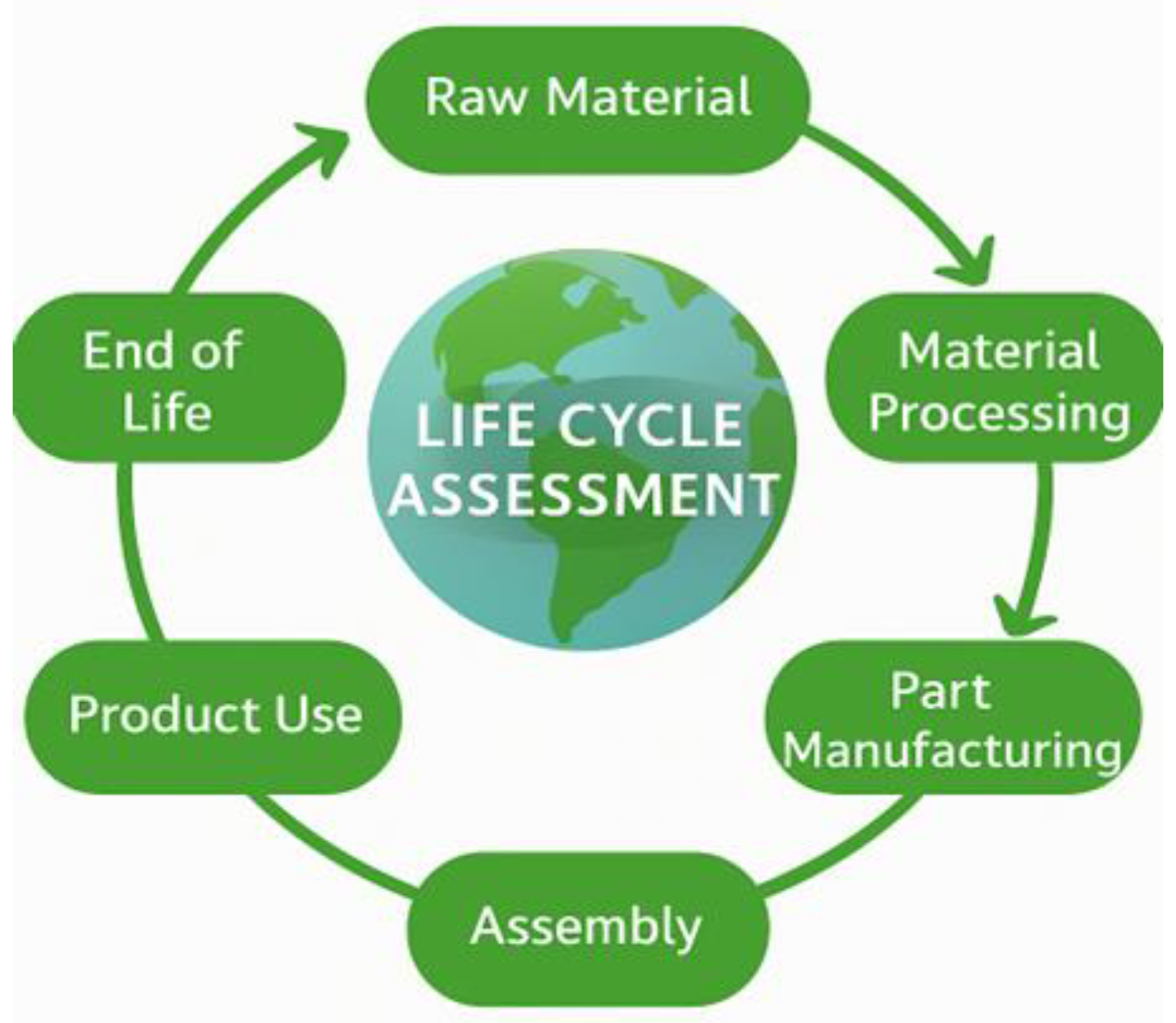

22]. This "cradle-to-grave" or, ideally, "cradle-to-cradle" (emphasizing circularity in end-of-life) approach encompasses all stages raw material acquisition, material processing, component manufacturing, vehicle assembly, distribution, the use phase (including electricity generation for charging and maintenance), and end-of-life (EOL) management.

Figure 2 provides a cradle-to-cradle illustration of life cycle assessment stages. At its core, LCA answers the question: “What environmental impacts occur over the entire life cycle of this product or system?”

The LCA methodology is structured into four distinct phases, which form the organizational basis for the analysis in this review:

Goal and Scope Definition: This initial phase defines the purpose of the study, the product system to be evaluated, the functional unit (the basis for comparison, e.g., one kilometer driven), and the system boundaries (which processes are included).

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): In this phase, data on all environmental inputs (e.g., energy, raw materials) and outputs (e.g., emissions, waste) are collected for every process within the system boundaries.

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): This phase translates the LCI results into potential environmental impacts. The inventory flows are classified into impact categories (e.g., climate change, acidification) and characterized using scientific models to quantify their potential effects.

Interpretation: The final phase involves evaluating the results from the LCI and LCIA to draw conclusions, identify significant issues, check for completeness and consistency, and provide recommendations in line with the study's goal.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Goal and Scope Definition

The goal and scope definition phase is foundational in any LCA, establishing the purpose, context, and boundaries of the assessment. A notable observation in the literature reviewed is the prevalent focus on comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) studies [

3,

23,

24,

25,

26]. A study is considered "comparative" when it directly contrasts at least two different vehicle types rather than merely examining various batteries or scenarios within a single vehicle type. Approximately 70% of these studies involve comparative analyses between different vehicle types, with internal combustion engine vehicles serving as the baseline. This high percentage suggests that most life cycle assessment research in the electric vehicle domain concentrates on evaluating the relative environmental, economic, and social impacts of various vehicle technologies rather than examining single vehicle types in isolation. This comparative approach is essential for understanding the trade-offs and benefits of transitioning from conventional internal combustion engines to electrified vehicle technologies The primary vehicle technologies assessed in these comparative studies include BEVs, PHEVs, HEVs, and FCEVs.

3.1.1. Functional Unit

The functional unit provides a quantified reference to which all inputs and outputs are related, ensuring a fair comparison between systems. The goal of the study informs the functional unit used by the authors. The most common functional unit is "per kilometer traveled (v.km)" [

27,

28,

29,

30]. These studies define the functional unit as the total function of the vehicle over its assumed lifetime, for example, "the transport of a passenger over 150,000 km”. In this approach, all life cycle impacts—from raw material extraction and manufacturing through the vehicle's operational life and final disposal—are aggregated and then normalized to a single kilometer of travel. Its prevalence is due to its simplicity, ease of communication, and direct relevance to vehicle-specific metrics like energy consumption (MJ/km) and emissions [

27,

28,

31]. However, the primary and most significant limitation of the v.km functional unit is its failure to account for vehicle occupancy. By normalizing impacts to the vehicle's movement, it treats a car carrying a single driver as functionally equivalent to one carrying four passengers. This is a critical oversimplification when the broader goal is to assess the environmental efficiency of a transportation system, where the ultimate purpose is to move people, not just the vehicle's mass [

32,

33].

To address the shortcomings of the v.km unit, many studies adopt the passenger-kilometer (p.km) as the functional unit [

32,

34]. This functional unit is considered a more accurate representation of the actual service provided by personal transport. It is calculated by normalizing the total life cycle impacts by the total distance traveled multiplied by the average vehicle occupancy rate. As noted by Fernando et al. 2020 [

32], the p.km unit is essential for any analysis that seeks to compare different modes of transportation, such as a single-occupant private car versus a fully occupied bus or train, as it correctly captures the efficiency gains from shared ridership. It is also the most appropriate functional unit for evaluating the environmental impacts of emerging Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) models like carpooling and ride sourcing, where occupancy levels are a key performance indicator [

35,

36].

For other studies, especially those centered on batteries or component-level LCA, functional units may be "per kWh of battery capacity" or "per battery system" [

12,

37,

38]. This functional unit allows for a direct comparison of the cradle-to-gate environmental impacts of manufacturing different battery chemistries (e.g., Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) vs. Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC)) or producing batteries in different regions with different energy mixes[

4,

11,

39,

40].

However, this functional unit is insufficient for assessing the battery's performance within the context of the full vehicle life cycle. It fails to account for critical performance characteristics that influence the overall environmental impact, such as cycle life (how many times the battery can be charged and discharged before significant degradation), energy density (which affects vehicle weight and thus efficiency), and round-trip efficiency (energy losses during charging and discharging). A battery with a low manufacturing impact per kWh may be a poor choice overall if it has a short lifespan and requires frequent replacement.

The choice between v.km, p.km and per kWh of battery capacity is therefore not merely technical; it reflects a fundamental difference in the research question, with the focus on either the vehicle as a product, mobility as a service or component specific.

The following table provides a consolidated summary and critical evaluation of the functional units discussed.

Table 2.

Typology of Functional Units in EV LCA Studies.

Table 2.

Typology of Functional Units in EV LCA Studies.

| Specific Unit |

Description and Rationale |

Advantages |

Limitations & Biases |

Reference Studies |

| vehicle-kilometer (v.km) |

Normalizes total life cycle impacts to one kilometer driven by the vehicle. Rationale is to compare the environmental efficiency of the vehicle as a product. |

Simple to calculate and communicate. Directly comparable to vehicle efficiency metrics. |

Ignores vehicle occupancy, which is the primary driver of system-level transport efficiency. It can be misleading when comparing personal vehicles to public or shared transport. |

[1,3,24,26,41,42,43,44] |

| passenger-kilometer (p.km) |

Normalizes total life cycle impacts to the transport of one passenger over one kilometer. Rationale is to assess the efficiency of providing a mobility service. |

Accounts for occupancy, providing a more meaningful measure of transport system efficiency. Essential for comparing different modes (car, bus, train) and mobility models (private vs. shared). |

Requires accurate data or assumptions on average occupancy rates, which can vary significantly by region, trip purpose, and time of day. |

[23,25,32,35,36,45,46,47] |

| per kWh of battery capacity |

Normalizes cradle-to-gate impacts to one kilowatt-hour of battery storage capacity. Rationale is to compare the manufacturing footprint of different battery technologies |

Useful for focused, cradle-to-gate comparisons of battery chemistries, manufacturing processes, or production locations |

Ignores critical in-use performance metrics like cycle life, energy density, and efficiency, which are crucial for overall vehicle life cycle performance. It can be highly misleading if used for whole-vehicle comparisons. |

[4,11,34,39,40,48,49,50,51,52] |

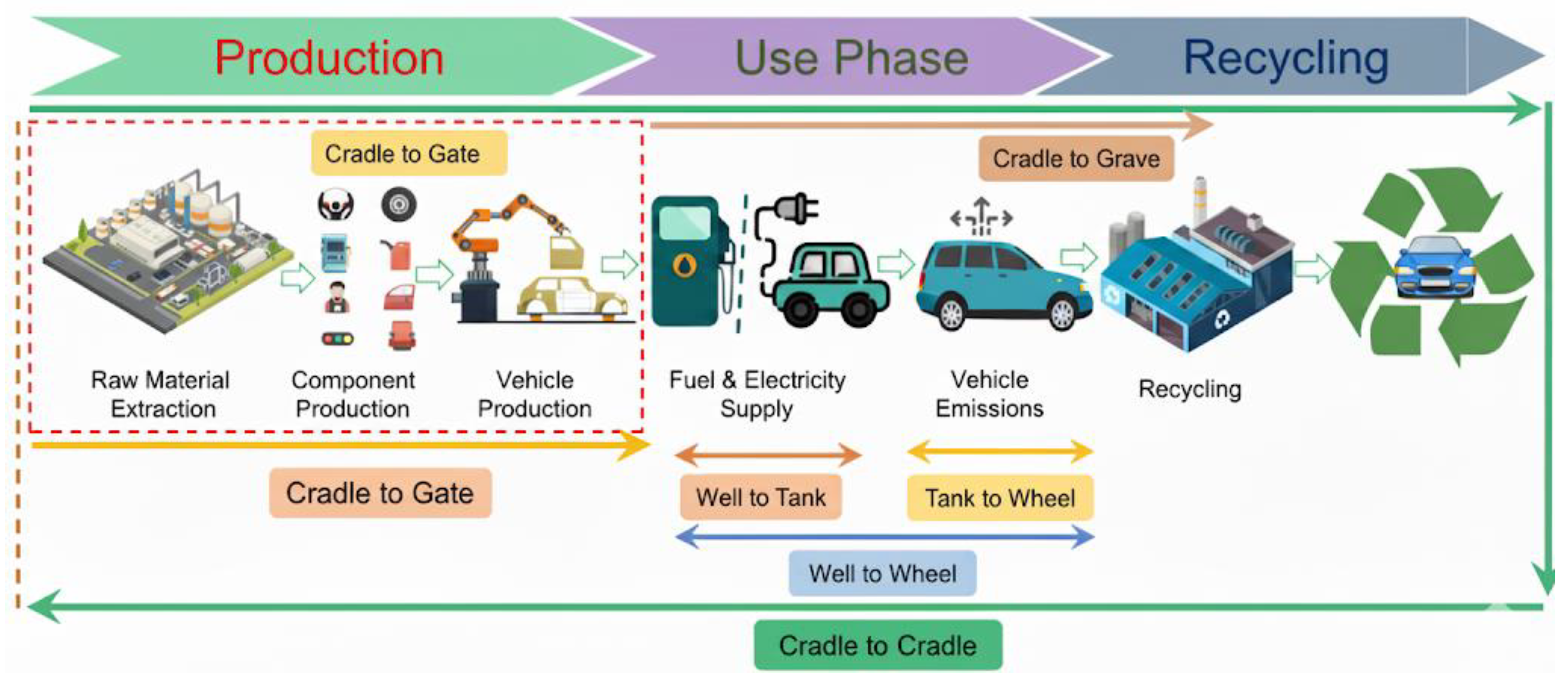

3.1.2. System Boundaries

Defining system boundaries is a crucial initial step in LCA, as it establishes the scope of the assessment and greatly affects its results and comparability. The selection of boundaries determines which life cycle stages and processes are considered, ranging from raw material extraction to end-of-life.

Cradle-to-Grave: This is the most comprehensive and common approach, used in 53.7% of the reviewed studies. The cradle-to-grave approach is the most comprehensive, encompassing all life cycle stages from raw material extraction, through manufacturing, distribution, vehicle use (including fuel/electricity consumption and maintenance), to end-of-life (EOL) treatments such as disposal or recycling [

53,

54]. This approach provides a more complete picture of the vehicle's environmental performance but requires more extensive data collection and modeling [

55]. It is frequently recommended for making robust comparisons, as demonstrated by Alexander et al [

27] for ICEV/BEV, Rashid et al. [

56] for HEV/PHEV, and Wong et al. [

57] for BEV/FCEV. This holistic view is essential for capturing the full environmental profile, especially for BEVs where manufacturing and EOL impacts are significant. However, some cradle-to-grave studies explicitly exclude EOL stages due to a lack of reliable data [

33,

37] which can be a significant limitation.

Well-to-Wheel (WTW): This boundary focuses only on the vehicle's operational life, encompassing fuel/electricity production (Well-to-Tank) and vehicle operation (Tank-to-Wheel). This is often divided into Well-to-Tank (WTT) or Well-to-Plug for electric vehicles, covering fuel/electricity production and delivery, and Tank-to-Wheel (TTW) or Plug-to-Wheel, covering vehicle operation efficiency and direct emissions[

58,

59]. Many Fuels Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV) LCAs tend to concentrate on the WTW scope, emphasizing fuel production pathways, as seen in the studies by Petrauskienė et al. [

42] and Wu et al. [

34] for evaluating fuel production pathways. Bekel et al. [

60] conduct a well-to-wheel LCA for BEVs and FCEVs, crucially and explicitly incorporating the often-neglected fuel supply infrastructure, including charging stations for BEVs and hydrogen production and distribution networks for FCEVs. Yang et al. [

29] define a total life cycle that includes both the vehicle life cycle (material extraction, component production, vehicle assembly, distribution, and disposal/recycling) and the fuel life cycle (fuel production and consumption during use). Burchart-Korol et al. [

61] accurately described WTW as a subset of LCA, focusing on fuel production (WTT) and vehicle operation (TTW) stages, typically emphasizing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, while excluding vehicle manufacturing, maintenance, and end-of-life impacts. This distinction highlights the importance of choosing system boundaries that suit the specific research question; WTW analysis alone is inadequate for developing a complete environmental profile of vehicle technology but can be useful for comparing fuel pathways.

Other System boundaries includes the

Cradle-to-Gate which is often used solely for the manufacturing phase, is the least used in terms of system boundaries [

57]; while cradle-to-cradle concept represents a closed-loop system where EOL products are ideally fully recycled or remanufactured into new products of similar or higher value, minimizing waste as highlighted in studies like Liu et al. [

62] which incorporate EOL recycling for batteries.

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive illustration of a vehicle's life cycle, breaking it down into main phases and defining various scopes for environmental assessment. Proper recycling of EV batteries can recover valuable materials and reduce the need for virgin resource extraction, thereby mitigating environmental impacts [

54].

Studies have shown that battery remanufacturing through recycled materials can reduce carbon emissions by 51.8% compared to battery production with virgin materials [

50,

53]. Future research should investigate the cradle-to-cradle approach as we advance towards achieving circularity in the economy.

The table below provides a summary of the boundary type, its advantages and limitations.

Table 3.

Summary of System Boundary Types in Electric Vehicle LCA Studies.

Table 3.

Summary of System Boundary Types in Electric Vehicle LCA Studies.

| Boundary Type |

Scope |

Advantages |

Limitations |

Reference Studies |

| Cradle-to-Grave |

Raw materials extraction to End of life |

Comprehensive assessment; captures all life cycle stages |

Data intensive; higher uncertainties |

[27,53,55,56,63] |

| Well to Wheel |

Focuses on fuel/electricity production and vehicle operation |

Highlights the environmental impact of energy carriers |

Excludes vehicle manufacturing and end-of-life impacts. |

[24,58,59,60,61,64] |

| Other System boundaries |

Cradle-to-Gate, End of life analysis |

Focuses on manufacturing or recycling impacts; also requires less data |

Excludes use phase impacts during modelling of end-of-life scenarios. |

[50,57,62] |

3.1.3. Attributional vs. Consequential LCA

EV life cycle studies can be performed using either an attributional LCA (ALCA) approach which assesses the average impacts of producing and using an EV in the current context; or a consequential LCA (CLCA) approach which looks at how impacts would change due to decisions [

65]. In practice, most EV LCA’s studies reviewed use an attributional approach. They typically model a single vehicle’s life cycle with average background processes [

15,

66,

67]. This is appropriate for comparisons between vehicle types under consistent assumptions. However, consequential questions are highly relevant to EVs. For instance, what is the marginal power plant that will supply electricity for new EV charging? How would large-scale EV adoption affect material production?

A few studies have embraced consequential modeling – using marginal emission factors for electricity or projecting future changes in supply chains [

68,

69]. Databases play a role here: as noted, Ecoinvent offers a “consequential” system model which some researchers have used to approximate CLCA for EVs (e.g. taking marginal electricity generation instead of average). Yet, even when consequential data is available, the methodological choice must align with the question. In general, industry and policy assessments (like regulatory carbon footprints of EVs) prefer attributional methods for comparability and compliance with standards (ISO 14040/44 lean towards ALCA unless otherwise specified).

Consequential LCA of EVs is more common in research exploring future scenarios or system-level effects (for instance, studies that consider how the power grid expansion driven by EV charging might alter the emissions outcome) [

30,

70,

71]. A review by Eltohamy et al [

33] and Das et al. [

72] pointed out that handling of marginal electricity sources is a key methodological divergence among EV LCAs, essentially an ALCA vs CLCA debate on electricity. Some studies assume the current grid (attributional, location-based) [

24,

61] , while others assume a future cleaner grid or a marginal plant (consequential) [

62,

73,

74]. The lack of harmonization here leads to differing conclusions about EV benefits. For example, using a static average grid in a coal-heavy region might show a high use-phase impact, whereas a consequential view might argue new renewable capacity would come online for EVs, lowering that impact [

24].

In summary, while attributional LCA dominates current practice for EVs is to answer, “what is the footprint of this vehicle?”, consequential LCA is employed for questions like “what if a million EVs are added to the grid?” or “what policy would achieve the most GHG reduction?

3.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

In the reviewed papers, it is evident that authors predominantly relied on a limited number of well-established life-cycle inventory (LCI) and impact assessment databases. The selection of these databases typically hinges on three factors: (1) the regional availability of high-quality data, (2) the extent of coverage for specific materials, such as battery-grade metals, and (3) their compatibility with life-cycle assessment (LCA) software like SimaPro, GaBi, and openLCA.

3.2.1. LCI Databases

Researchers predominantly rely on a few well-established LCI databases. The most prominent databases identified are:

Ecoinvent: As the most widely used database, appearing in 64.3% of studies, Ecoinvent is often considered the gold standard for LCI data due to its global applicability and comprehensive coverage of all lifecycle stages [

7,

75]. Most academic studies rely on Ecoinvent for processes such as battery cell manufacturing, material production (steel, aluminum), and vehicle components. Its prominence is reinforced by its availability in all major LCA software platforms. Different versions are cited in the literature, reflecting its continuous updates (e.g., v2.2, v3.2, v3.8) [

61,

75,

76]. Ecoinvent is a cornerstone of EV LCA modeling, providing the high-quality background data necessary for robust assessments.

GREET Model: While also a software tool, the Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Technologies (GREET) model functions as a critical LCI database, particularly for transportation-focused studies. Developed by the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory, it serves as a benchmark for well-to-wheel analyses in North America [

64]. GREET contains embedded data for battery manufacturing, electricity generation pathways, and material production. It is frequently used to model the use phase and fuel cycle of vehicles [

23,

57,

77,

78].

GaBi Databases: The GaBi databases, developed by Sphera, are another major LCI source, known for being industry-driven and containing detailed, proprietary process data from corporate partnerships. These databases offer strong coverage of industrial processes, such as plastics production and specific automotive manufacturing steps, making them a common choice for confidential industry reports[

79].

Regional Databases (e.g., ELCD, CLCD): To improve regional accuracy, researchers often supplement global databases with localized ones. The European Life Cycle Database (ELCD) provides open-access data for processes within the European Union [

64]. Similarly, studies focused on China frequently use the China Life Cycle Inventory Database (CLCD) to access more precise data for Chinese industrial processes and regional electricity grids [

53].

A primary concern with databases is that the fast-paced advancements in electric vehicles and their components can render database entries obsolete quickly. For instance, there have been significant improvements in battery energy density and manufacturing efficiency in recent years, which could potentially lessen production impacts[

12,

37]. However, most databases typically take about a year to update and reflect these changes. Additionally, databases might not fully capture the variety in battery chemistry, manufacturing methods, or photovoltaic technologies [

11,

39,

80]. This issue is particularly relevant for new technologies like VIPV, which may not be specifically included in current databases. Furthermore, production impacts can differ greatly between regions due to variations in electricity sources, manufacturing techniques, and environmental regulations. Many databases offer global data or concentrate on specific areas, which might not accurately reflect production data of new manufacturing processes, technologies and new production centers [

81]. To overcome these challenges, researchers often enhance database entries with primary data from manufacturers or literature. Nonetheless, this method can introduce further uncertainties and may affect the comparability of studies. Utilizing multiple databases or combining database information with primary data can improve the representativeness and reliability of LCA results.

Table 4 compares the main databases used in LCA studies of electric vehicles, highlighting their coverage, strengths, and representative studies.

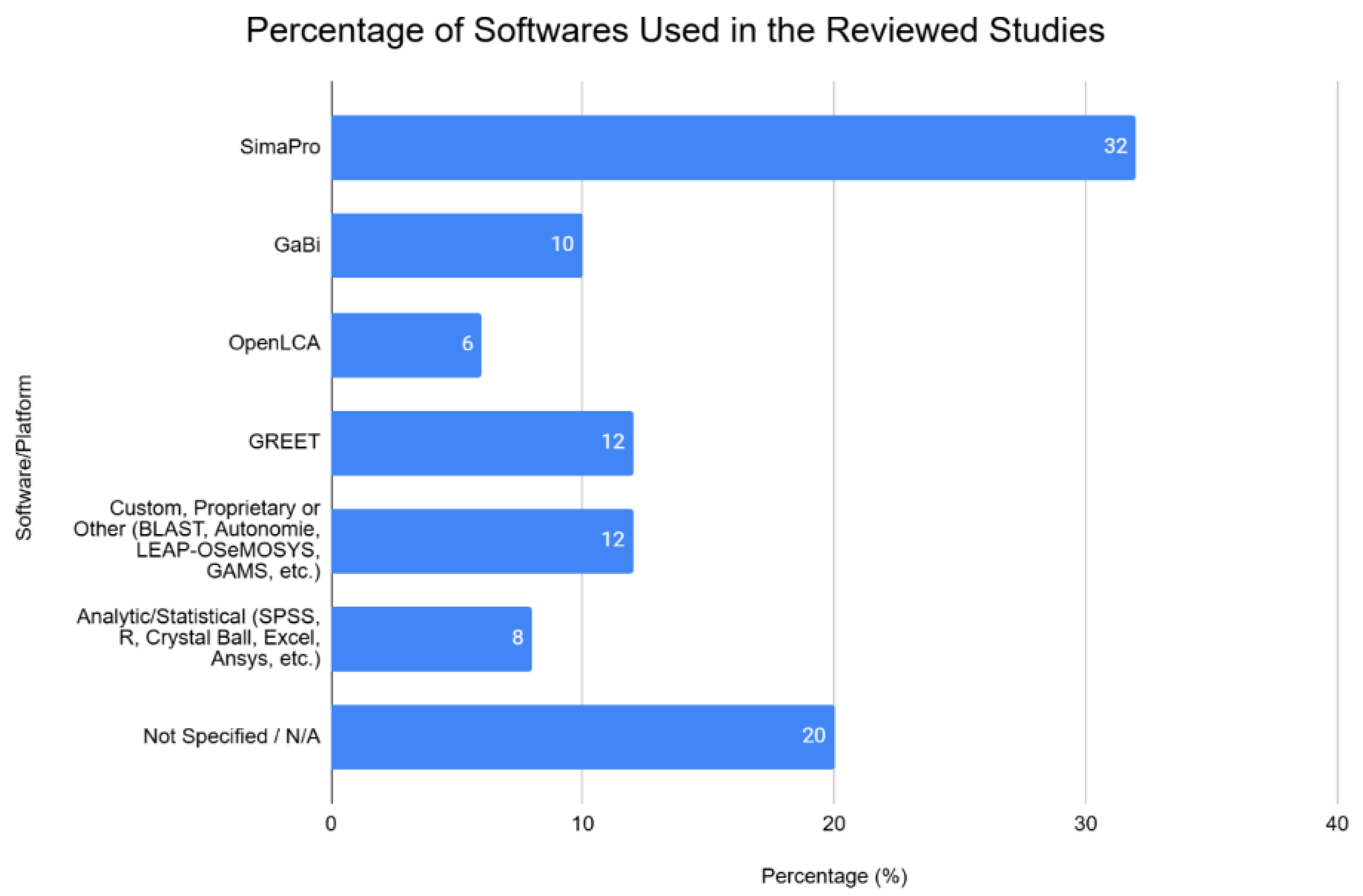

3.2.2. LCA Software

LCA software tools facilitate the modeling, calculation, and interpretation of life cycle assessment studies by providing user interfaces, databases, and computational capabilities [

55]. The choice of tool can influence study outcomes and reproducibility. Several software tools were used for conducting LCA studies in the reviewed studies and the identified software are presented in

Figure 4 below.

SimaPro: Leads as the preferred tool for comprehensive process-based LCAs, used in 32% of the reviewed studies. It offers compatibility with leading databases like Ecoinvent and a broad suite of impact assessment methods. Its ability to handle multi-stage, multi-impact analyses and Monte Carlo-based uncertainty assessments is often highlighted [

19,

45,

91].

GaBi: A popular choice, particularly in European and industry-focused research, for its robust interface and integrated, industry-backed database. It is frequently applied in studies with a strong manufacturing or automotive material focus [

76,

85].

GREET Model: This model from Argonne National Laboratory is widely used for North American, fuel cycle, and well-to-wheel studies due to its specific focus on transportation energy systems and detailed fuel pathway modeling [

57,

78,

88] .

OpenLCA: An open-source tool that is increasingly adopted in academic studies, especially where flexibility, cost, and integration with custom methods or regional databases are priorities [

7,

42,

43].

Specialized or Custom Tools: Several studies employ specialized software for specific tasks, such as Autonomie and BLAST for vehicle and battery dynamic modeling[

53,

92] , or statistical software to supplement LCA calculations with scenario modeling and probabilistic uncertainty estimation [

3,

28,

87,

93] .

Notably, 20% of the papers did not specify the tools used. The critique by Yang et al. [

29] regarding the limitations of commercial software suggests they encountered practical issues related to this lack of transparency or control. The frequent omission of explicit references to specific LCA software and its version in the methods sections of numerous LCA studies can substantially impede the reproducibility and verification of research outcomes. Different software packages, or even varying versions of the same software, may implement LCIA methods, manage allocation procedures, model EoL scenarios, or conduct certain background calculations in subtly distinct manners. It is therefore recommended that every published LCA study should include a dedicated “Tools & Data” subsection stating the software name, version number, database versions and any custom scripts or macros used.

Table 5 compares the main software tools used in LCA studies of electric vehicles, highlighting their features, databases, and user interface.

3.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) provides a structured approach to translating Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) flows into potential environmental impacts. For electric vehicles (EVs), LCIA plays a vital role in determining sustainability trade-offs across climate change, resource use, toxicity, and air pollution. However, the methodological diversity in LCIA introduces variability in results and interpretability. The reviewed literature reveals that researchers adopt a range of LCIA methods depending on geographical scope, regulatory context, and targeted environmental concerns. This diversity leads to what may be described as “methodological pluralism,” which, while allowing tailored assessments, poses challenges for cross-study comparability.

ReCiPe: Among the reviewed studies, ReCiPe—particularly ReCiPe 2016—is the most widely adopted LCIA model, used in approximately 50% of the papers. It supports both midpoint and endpoint assessments and provides detailed indicators for global warming potential (GWP), acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity (cancer and non-cancer), and resource depletion. ReCiPe is notably favored in studies due to this harmonized and comprehensive framework [

41,

94,

95].

CML: The CML 2001/2002 method accounts for around 20% of applications and is especially prevalent in older or region-specific LCAs. It is valued for its focus on scientifically robust midpoint categories such as abiotic depletion (ADP), acidification, and eutrophication. Notably, Dér et al. [

31] and Zhang et al. [

58] relied on this method for resource-oriented analyses.

IPCC GWP 100a: Studies that prioritize climate change frequently employ IPCC GWP (100-year horizon) factors alone—comprising about 15% of the sample. This is especially common in assessments focused on specific fuel pathways (e.g., hydrogen) where broader impact categories are deemed less relevant [

85,

89]. While this approach is simple and transparent, it may underrepresent environmental trade-offs by excluding pollutants beyond CO₂, CH₄, and N₂O.

Other Specialized Methods: About 15% of the studies apply specialized or hybrid approaches. Navas-Anguita et al. [

95] use IMPACT 2002+ to assess endpoint indicators such as human health and resource scarcity, while Pinto-Bautista et al[

96] rely on ILCD Midpoint 2011+.

While the availability of multiple LCIA methods provides flexibility, it can also lead to inconsistencies. For example, studies using ReCiPe and CML may report significantly different outcomes for categories like human toxicity due to differences in characterization factors. This inconsistency creates interpretive challenges for policymakers and highlights the need for transparent justification and consistent reporting across LCA studies.

Table 6 provides a summary of the LCIA methods used in the reviewed studies.

3.4. Interpretation

The final LCA phase involves evaluating the results to draw robust conclusions. This includes assessing the certainty of the results and synthesizing key findings.

3.4.1. Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis

A crucial element of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies is constituted by uncertainty analysis, which permits researchers to assess the robustness of their results through an exploration of how variations in key parameters, assumptions, or scenarios may impact environmental outcomes. Among the studies reviewed, approximately 59.5% were found to have explicitly included such an analysis, a fact that highlights a broad recognition of its importance. In contrast, 40.5% of the studies either omitted this analysis or failed to report it explicitly, a circumstance which could potentially undermine the validity of their conclusions. Several established methods employed for this purpose is discussed below.

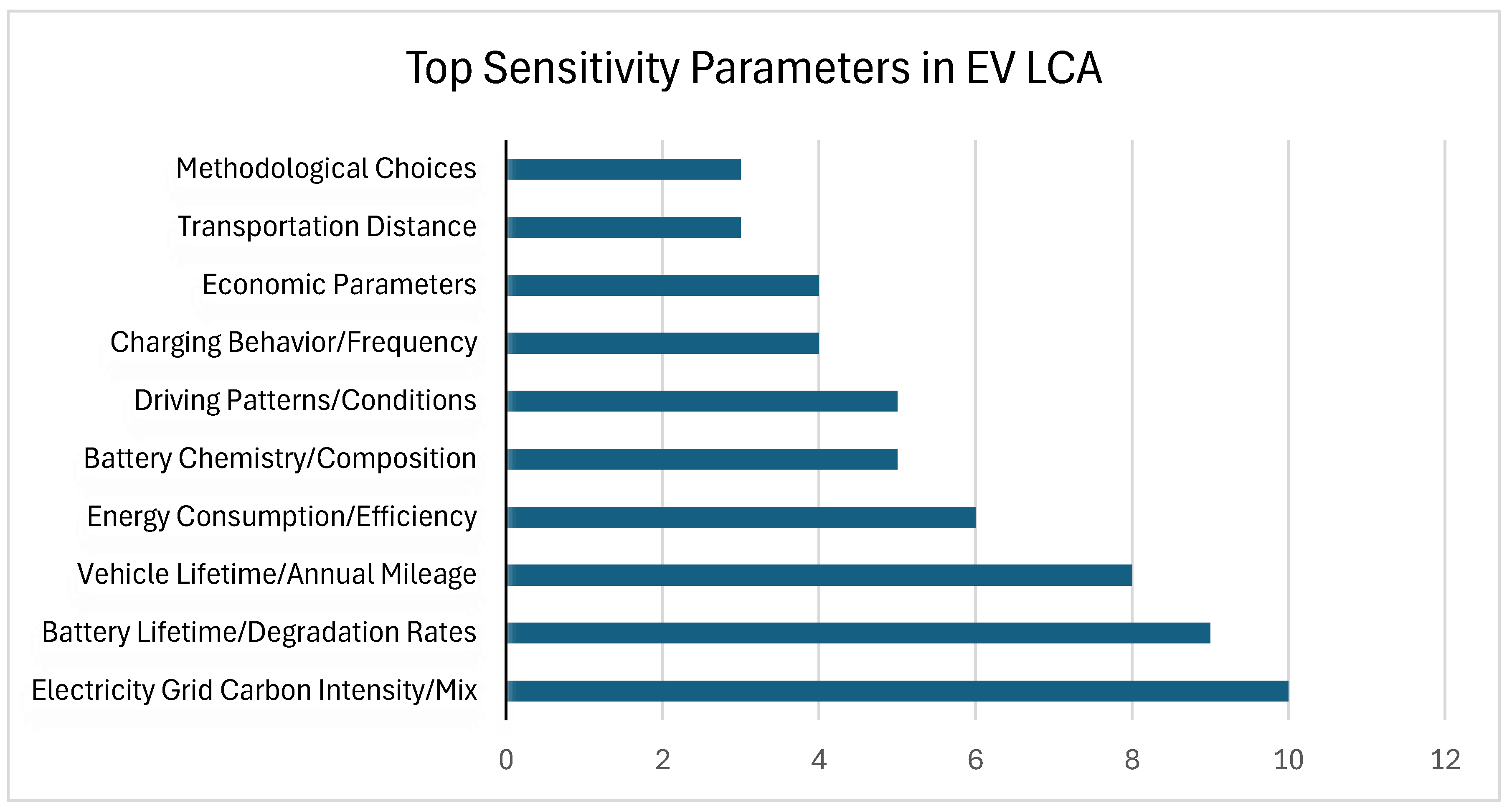

Sensitivity Analysis: This represents the most accessible and frequently applied method. It is designed to gauge the extent to which variations in key factors affect the aggregate results. The key parameters that are most frequently subjected to analysis include the carbon intensity of the electricity grid [

85,

87,

100], the lifetime and degradation rates of the battery [

49,

53,

84], and the operational characteristics of the vehicle, such as annual mileage and energy consumption [

29].

Figure 5 shows the frequency of the range of parameters found in the reviewed studies which is reflective of the multi-dimensional nature of EV sustainability. However, sensitivity analysis typically employs one-at-a-time methods and does not capture interactions among parameters, limiting its scope for complex systems [

101].

Scenario Analysis: This approach is designed to address deeper, structural uncertainties through the modeling of plausible future conditions, such as changes in the energy mix, technological advancements, or behavioral shifts. Scenario-based studies typically explore discrete "what-if" conditions, particularly focusing on future energy system transitions and policy pathways [

95]. Various studies have applied scenario analysis to evaluate the potential effects of evolving electricity grids, extended BEV lifespans, or different charging behaviors on GHG emissions [

58,

62,

73,

74,

102,

103]. While this method supports strategic planning for different future scenarios, it relies heavily on expert assumptions and lacks probabilistic rigor.

Monte Carlo Simulation: This is recognized as the most statistically robust approach, as it propagates input uncertainties through the LCA model by utilizing defined probability distributions, thereby yielding confidence intervals and probabilistic results [

60,

61]. For EV LCA, Monte Carlo has been used to iterate battery composition uncertainty [

82], and compare alternative fuels for EV vehicles [

104,

105] Despite the deeper insights afforded by this method, its considerable demands with respect to data and computational resources have limited its widespread adoption [

61] .

Each of these methods contributes in a distinct manner to the understanding of uncertainty, and it is suggested that their complementary application is often ideal for a comprehensive interpretation of the results of an EV LCA.

Table 7.

Summary of Uncertainty Analysis Methods and Their Characteristics in EV LCA Studies.

Table 7.

Summary of Uncertainty Analysis Methods and Their Characteristics in EV LCA Studies.

| Method |

Description |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Representative Studies |

| Parameter-Specific Sensitivity |

Varies key input variables individually to assess impact on results |

Easy to implement; identifies key influencing variables |

Ignore parameter interactions; not probabilistic |

[39,49,53,84,87,100] |

| Scenario Analysis |

Evaluates future pathways or regional changes (e.g., electricity mix, battery tech, vehicle use) |

Captures systemic and structural uncertainties; policy-relevant |

Depends on expert assumptions; lacks statistical quantification |

[58,62,73,74,102,103] |

| Monte Carlo Simulation |

Uses random sampling from input distributions to estimate output uncertainty |

Provides probabilistic results; captures interactions |

Data- and computation-intensive; requires defined distributions |

[60,61,82,104,105] |

| Other/Implicit Methods |

Includes pedigree matrices, expert elicitation, or qualitative discussions |

Specific to a domain or use case |

Usually not reproducible. |

[81,90,106] |

3.4.2. Synthesis of Key Findings by Technology

The interpretation of LCA results consistently shows that the environmental benefits of EVs are highly context dependent. While a detailed summary of every study is beyond the scope of this review, a synthesis of the consensus findings for each technology is presented below.

Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs): BEVs operate exclusively on electric motors and rechargeable batteries, resulting in zero tailpipe emissions. Their life-cycle impacts are distinguished by a significant upfront environmental burden from the energy- and carbon-intensive manufacturing of their components, particularly the lithium-ion battery, which creates a substantial “embodied” carbon footprint [

25,

76]. However, multiple life cycle assessments have demonstrated that this initial production impact is ultimately offset by the high operational efficiency of the vehicle, provided that the electricity used for charging is derived from low-carbon sources [

25,

77]. The extent of the life-cycle benefit is, therefore, critically contingent upon the carbon intensity of the regional electricity grid; in regions with predominantly renewable energy, GHG emission reductions may be as high as 90% relative to conventional vehicles [

13,

76], whereas in coal-dependent grids, the life-cycle emissions of a BEV can be comparable to those of a gasoline vehicle [

63,

77,

78,

79]. The initial manufacturing impacts are being progressively mitigated through advancements in battery technology and the adoption of circular economy principles, such as the extensive recycling of battery materials, which has been shown to significantly reduce both cumulative carbon emissions and the demand for virgin raw materials [

12,

38,

39,

65,

80].

Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs): PHEVs are constituted by a powertrain that integrates a battery-powered electric drivetrain with a conventional internal combustion engine. By virtue of their dual reliance on both electricity and liquid fuel, PHEVs occupy an intermediate position in life cycle assessment terms; their environmental performance is generally superior to that of conventional ICEVs, yet they do not typically achieve the low-emission profile characteristic of pure BEVs under most scenarios [

43,

53]. The comparatively smaller battery capacity in a PHEV, relative to that of a BEV, serves to reduce the environmental impacts associated with the manufacturing phase [

48,

54]. The environmental performance of PHEVs is observed to be exceptionally sensitive to their operational parameters, most notably the patterns of their use and charging. A critical determinant in this regard is the carbon intensity of the electricity grid, in conjunction with the proportion of total distance traversed utilizing electric power as opposed to the internal combustion engine. The greatest CO₂ savings are realized when PHEVs are operated predominantly on electricity from a clean grid [

32,

53,

56]. Conversely, in regions characterized by a carbon-intensive electricity grid, or if the gasoline engine is used frequently, the relative environmental benefit is markedly diminished [

24,

40,

57]. Although certain exceptional scenarios have been noted wherein an efficient PHEV engine coupled with high-carbon electricity could result in emissions comparable to a BEV, such cases underscore the principle that electricity from carbon-intensive sources can neutralize the advantages of electric operation [

34]. Consequently, the optimal application for PHEVs is frequently posited as that of a transitional technology, particularly when powered by low-carbon electricity and sustainable biofuels [

53,

56,

58]. While studies report that PHEVs achieve lower lifetime fuel consumption and emissions than comparable non-plug-in vehicles [

40,

48,

57], their ultimate impact remains contingent upon charging behavior and energy sources.

Hybrid Electric Vehicles: HEVs which are distinguished as non-plug-in hybrids, are equipped with a comparatively small battery and electric motor that function in concert with an ICEV. The battery's state of charge is maintained exclusively through regenerative braking and by the operation of the engine, as these vehicles are not designed to be charged from an external electrical grid [

44]. From a life-cycle assessment perspective, the manufacturing impacts associated with HEV are found to be marginally greater than those of a conventional vehicle, an increase attributable to the inclusion of supplementary components such as battery, electric motor, and power electronics [

48]. The principal environmental advantage afforded by HEVs is actualized during the use phase and is manifested as a reduction in fuel consumption. Through the strategic alternation between electric drive assistance and engine operation, in conjunction with the capture of energy via regenerative braking, HEVs can achieve a substantial reduction in the consumption of gasoline or diesel per kilometer, which corresponds to a direct and proportional decrease in tailpipe CO₂ and pollutant emissions [

41]. Within a cradle-to-grave assessment, it is consistently observed that the well-to-wheel fuel cycle is accountable for approximately 80 to 90 percent of the total energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with the manufacturing and end-of-life phases contributing only a minor fraction [

41,

44,

48]. Therefore, although HEVs may contribute to an enhancement of urban air quality and a reduction in GHG emissions relative to conventional vehicles, they do not effectuate the complete elimination of said emissions; rather, they are to be understood as a mitigating technology as opposed to a zero-emission solution [

41]. While the end-of-life management of the battery remains crucial for recovering valuable materials [

45,

51,

52], projections indicate that HEVs will likely need to be superseded by 2050 to achieve stringent long-term climate objectives [

45].

Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs): FCEVs are propelled by an electric motor, a characteristic shared with BEVs; however, their mode of energy storage is distinct, as they generate electricity in situ by means of a hydrogen fuel cell rather than relying upon a large-capacity battery. The manufacturing of an FCEV entails the fabrication of several specialized and energy-intensive components, including the fuel cell stack, which frequently incorporates precious metals such as platinum as catalytic agents, and high-pressure hydrogen storage tanks, which are typically reinforced with carbon fibers [

34,

59]. The preponderant environmental impacts associated with FCEVs are not localized to the vehicle's operational phase of zero tailpipe emissions but are instead primarily situated within the "well-to-tank" stage, which encompasses the production and distribution of hydrogen fuel [

61,

62]. It is a matter of critical significance that the environmental performance of an FCEV is overwhelmingly contingent upon the method by which its hydrogen fuel is produced [

45,

59]. At present, the predominant method for hydrogen generation is steam methane reforming of natural gas, a process heavily reliant on fossil fuels that yields what is commonly termed "gray" hydrogen. The use of such hydrogen precludes FCEVs from achieving their optimal environmental potential due to substantial upstream emissions [

63,

64]. Conversely, a remarkable degree of environmental performance can be achieved through the utilization of low-carbon hydrogen; in scenarios where hydrogen is derived from 100 percent renewable electricity, the cradle-to-grave GHG emissions of an FCEV can approach a value of zero, a performance analogous to that of a BEV charged with renewable energy [

63,

64]. The end-of-life phase, which involves the recycling of fuel cell stacks and the recovery of precious metals, can further augment the life-cycle benefits of FCEVs [

62]. Literature consistently underscores that the decarbonization of the hydrogen supply chain is of pivotal importance for rendering FCEVs environmentally competitive [

45,

62].

Solar-Powered Vehicles (SPV) / Vehicle-Integrated Photovoltaics (VIPV): A novel technological development in the domain of sustainable transportation is the integration of solar photovoltaic (PV) panels directly onto vehicle surfaces for the purpose of providing on-board renewable electricity [

63]. VIPV entails the incorporation of PV modules into the body of a vehicle, which enables the generation of a portion of its own requisite energy. The addition of PV cells to a vehicle augments the manufacturing footprint because of the energy consumption and associated emissions involved in the production of solar panels [

65,

66]. The determinative trade-off within the life cycle assessment is a function of the quantity of solar energy that the system produces over its operational lifetime, thereby offsetting grid electricity or fuel consumption, in comparison to the manufacturing and added weight penalties of the PV system itself. If the vehicle-integrated PV system generates a substantial amount of electricity, it has the potential to compensate for the production emissions of the solar hardware by displacing energy that would otherwise be sourced from the grid; if, conversely, a minimal quantity of electricity is generated, the embodied impacts may be found to outweigh the operational benefits [

67,

68]. Studies have indicated that the benefits of VIPV are maximized under conditions of high solar irradiance and in regions served by carbon-intensive electricity grids [

66,

69,

70,

71]. The CO₂ payback period for a vehicular PV system may be on the order of a decade under typical conditions but can be significantly shorter in sunnier locales with carbon-intensive grids [

66,

70]. As of 2025, SPVs and VIPV systems are predominantly in pilot or prototype stages, but they represent an innovative supplement that may enhance the ecological profile of EVs, particularly in regions with high solar insolation.

Table 8.

Summary of Life Cycle Assessment Findings by Vehicle Technology.

Table 8.

Summary of Life Cycle Assessment Findings by Vehicle Technology.

| Vehicle Technology |

LCA Summary |

Cited References |

| Battery Electric Vehicle |

Characterized by high manufacturing emissions (embodied carbon), particularly from the battery, but very low use-phase emissions. The overall life-cycle benefit is critically dependent on the carbon intensity of the electricity grid used for charging. Circular economy principles, such as battery recycling, are crucial for mitigating initial impacts. |

[12,13,25,38,39,65,75,76,77,78,79,80] |

| Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

Occupies an intermediate position between BEVs and ICEVs. Performance is highly sensitive to user charging behavior and the regional electricity grid's carbon intensity. Lower manufacturing impacts than BEVs due to smaller batteries, but retains tailpipe emissions from the ICE. Often considered a transitional technology. |

[24,32,34,40,43,48,53,56,57,58] |

| Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

Principal environmental benefit is a 15-30% reduction in fuel consumption during the use phase. The well-to-wheel fuel cycle dominates its life-cycle impact (80-90%). It is a mitigating, not a zero-emission, technology and is projected to be phased out to meet long-term climate goals. |

[41,44,45,48,51,52] |

| Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle |

Exhibits zero tailpipe emissions, but its life-cycle performance is overwhelmingly dependent on the hydrogen production pathway ("well-to-tank" stage). The use of "green" hydrogen can result in near-zero life-cycle emissions, whereas "gray" hydrogen from fossil fuels offers limited benefits over efficient ICEVs. |

[34,45,59,61,62,63,64] |

| Solar Powered Vehicle / Vehicle Integrated PhotoVoltaic |

A nascent technology where the LCA trade-off balances the added manufacturing footprint of PV panels against the avoided emissions from displaced grid electricity. Benefits are maximized in regions with high solar irradiance and carbon-intensive electricity grids. |

[63,65,66,67,68,70,71] |

4. Conclusion

This review examined how recent EV LCAs are set up and executed, focusing on the stated goals and scope, functional units, system boundaries (cradle-to-grave and well-to-wheel), and the choice between attributional and consequential modeling across studies published mainly from 2018 to 2025. It mapped commonly used databases and tools (e.g., Ecoinvent, GREET, GaBi, and regional inventories), and summarized typical LCIA methods, emphasizing the need for clear reporting of versions, regionalization, and assumptions to support comparison across studies. The review also assessed how uncertainty is handled—through sensitivity and scenario analyses more often, and less frequently via Monte Carlo—showing that methods are unevenly applied and that broader, more systematic uncertainty treatment would improve confidence in results.

Findings across technologies indicate that life-cycle outcomes are context-dependent: BEVs tend to achieve the largest GHG reductions when charged on low-carbon grids and when battery production and end-of-life management are improved, while PHEVs and HEVs often act as transitional options whose performance depends on real-world driving and charging patterns, and FCEVs deliver clear benefits only with low-carbon hydrogen. The review highlights VIPV and solar-powered vehicles as promising but under-studied options; their net benefit depends on local solar resources, design choices (including added mass and durability), and the carbon intensity of the grid over time, warranting comprehensive location-specific assessments. Across the literature, recurring hotspots include battery manufacturing burdens, the carbon intensity of electricity in the use phase, usage parameters (mileage, driving conditions, efficiency, charging behavior), and end-of-life strategies, with circular measures like repair, repurpose, and recycling reducing embodied impacts and demand for primary materials when adopted at scale.

Key challenges and proposed directions:

Database timeliness and transparency: Rapid changes in battery technology and electricity systems can outpace inventory updates; future work should make temporal assumptions explicit, use dynamic use-phase modeling where relevant, and blend curated secondary data with traceable primary data to reduce bias.

Regional specificity and interoperability: Limited regional coverage and inconsistent data models hinder comparability; expanding region-resolved datasets and adopting conventions for cross-platform exchange and version control will improve alignment across studies.

Reporting consistency: Variation in functional units, system boundaries, LCIA choices, and software/database versions complicates synthesis; standardized reporting templates should be used to enable reproducible comparisons and support policy use.

Uncertainty practice: Many studies rely on one-at-a-time sensitivity or qualitative scenarios; broader use of probabilistic, multi-parameter methods (with transparent sensitivity and scenario analyses) is needed to bound decision-relevant ranges.

Evidence gaps on VIPV/SPV and circular pathways: Comprehensive LCAs should capture irradiance, duty cycles, added mass, durability, logistics, second-life uses, and recycling under dynamic grid scenarios to inform design and deployment choices

In practical terms, electrification strategies should be coordinated with grid decarbonization, demand-side management, and smart charging to secure consistent use-phase benefits, while researchers and practitioners should align methods and data to improve comparability and reduce uncertainty as technologies and systems evolve. Taken together, these steps provide a clear path to more reliable, policy-ready EV LCAs and help target research where it can most effectively support sustainable mobility at scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G. and O.J.O.; methodology, O.J.O. and K.G.; software, O.J.O; writing—original draft preparation, O.J.O..; writing—review and editing, O.J.O. and K.G..; visualization, O.J.O..; supervision, K.G..; project administration, K.G.; funding acquisition, K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by the grant “Excellence initiative—research university” for the AGH University of Krakow – no. 16.16.150.7998 and by the research subvention no. 16.16.150.545.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU |

European Union |

| EVs |

Electric Vehicles |

| ICEVs |

Internal combustion engine vehicles |

| FCEVs |

Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles |

| VIPV |

Vehicle-Integrated Photovoltaics |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| BEV |

Battery Electric Vehicles |

| HEV |

Hybrid Electric Vehicles |

| SPV |

Solar-Powered Vehicles |

| GWP |

Global Warming Potential |

| ELCD |

European Life Cycle Database |

| CLCA |

Consequential Life Cycle Assessment |

| ALCA |

Attributional Life Cycle Assessment |

| EOL |

End of Life |

| WTW |

Well- to- Wheel |

| CLCD |

Chinese Life Cycle Inventory Database |

| WTT |

Well-to-Tank |

| PHEVs |

Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles |

| LCI |

Life Cycle Inventory |

| LCIA |

Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

| MaaS |

Mobility as a Service |

| ISO |

International Standard Organization |

| NMC |

Nickel Manganese Cobalt |

| TTW |

Tank-to-Wheel |

| LFP |

Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| WTW |

Well-to-Wheel |

| GREET |

Greenhouse gases Regulated Emissions & Energies use in Technologies |

| US |

United States of America |

| GHG |

Green House Gases |

References

- Oliveri, L. M.; D’Urso, D.; Trapani, N.; Chiacchio, F. Electrifying Green Logistics: A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Electric and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lai, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y.; Ouyang, M.; et al. A critical comparison of LCA calculation models for the power lithium-ion battery in electric vehicles during use-phase. Energy 2024, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkin, A.; Kryukov, E.; Masleeva, O.; Petukhov, Y.; Gusev, D. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Electric and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles. Energies 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Guo, W.; Zhang, C.; Nie, Y.; Li, J. Comparative Study on Environmental Impact of Electric Vehicle Batteries from a Regional and Energy Perspective. Batteries 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kanwal, A.; Asim, M.; Pervez, M.; Mujtaba, M. A.; Fouad, Y.; Kalam, M. A. Transforming the transportation sector: Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions through electric vehicles (EVs) and exploring sustainable pathways. AIP Adv 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M.; Kumar, L.; Zulkifli, S. A.; Jamil, A. Aspects of artificial intelligence in future electric vehicle technology for sustainable environmental impact. Environmental Challenges 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournaviti, M.; Vlachokostas, C.; Michailidou, A. V.; Savva, C.; Achillas, C. Addressing the Scientific Gaps Between Life Cycle Thinking and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for the Sustainability Assessment of Electric Vehicles’ Lithium-Ion Batteries. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Fahad, S.; Alanazi, F. Electric Vehicles: Benefits, Challenges, and Potential Solutions for Widespread Adaptation. Applied Sciences 2023, Vol. 13, Page 6016 2023, 13, 6016. [Google Scholar]

- Tilly, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Degirmenci, K.; Paz, A. How sustainable is electric vehicle adoption? Insights from a PRISMA review. Sustain Cities Soc 2024, 117, 105950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Qadir, S.; Ahmad, F.; Mohsin A B Al-Wahedi, A.; Iqbal, A.; Ali, A. Navigating the complex realities of electric vehicle adoption: A comprehensive study of government strategies, policies, and incentives. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 53, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cong, N.; Zhang, X.; Yue, Q.; Zhang, M. Life cycle assessment and carbon reduction potential prediction of electric vehicles batteries. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankathi, S. K.; Bouchard, J.; He, X. Beyond Tailpipe Emissions: Life Cycle Assessment Unravels Battery’s Carbon Footprint in Electric Vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchart, D.; Przytuła, I. Review of Environmental Life Cycle Assessment for Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles in Road Transport. Energies (Basel) 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniak, M.; Jaskowski, P.; Tomczuk, K. Review of Economic, Technical and Environmental Aspects of Electric Vehicles. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchart, D.; Przytuła, I. Carbon Footprint of Electric Vehicles—Review of Methodologies and Determinants. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, N. C.; Kucukvar, M. A systematic review on sustainability assessment of electric vehicles: Knowledge gaps and future perspectives. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2022, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolganova, I.; Rödl, A.; Bach, V.; Kaltschmitt, M.; Finkbeiner, M. A review of life cycle assessment studies of electric vehicles with a focus on resource use. Resources 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temporelli, A.; Carvalho, M. L.; Girardi, P. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicle batteries: An overview of recent literature. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubecki, A.; Szczurowski, J.; Zarębska, K. The importance of uncertainty sources in LCA for the reliability of environmental comparisons: A case study on public bus fleet electrification. Appl Energy 2025, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, D.; Kelleher, L.; Wang, L. Life cycle assessment: Driving strategies for promoting electric vehicles in China. Int J Sustain Transp 2024, 18, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.; Raugei, M.; Pons, A.; Vasileiadis, N.; Ong, H.; Casullo, L. Environmental challenges through the life cycle of battery electric vehicles Study; 2023.

- Setyoko, A. T.; Nurcahyo, R.; Sumaedi, S. Life Cycle Assessment of Electric Vehicle Batteries: Review and Critical Appraisal. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2023; Vol. 465.

- Candelaresi, D.; Valente, A.; Iribarren, D.; Dufour, J.; Spazzafumo, G. Comparative life cycle assessment of hydrogen-fuelled passenger cars. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 35961–35973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrauskienė, K.; Skvarnavičiūtė, M.; Dvarionienė, J. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment of electric and conventional vehicles in Lithuania. J Clean Prod 2020, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Samper Naranjo, G.; Bolonio, D.; Ortega, M. F.; García-Martínez, M. J. Comparative life cycle assessment of conventional, electric and hybrid passenger vehicles in Spain. J Clean Prod 2021, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syré, A. M.; Shyposha, P.; Freisem, L.; Pollak, A.; Göhlich, D. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Battery and Fuel Cell Electric Cars, Trucks, and Buses. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Abraham, J. Making sense of life cycle assessment results of electrified vehicles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Battery Electric and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles Considering the Impact of Electricity Generation Mix: A Case Study in China. Atmosphere (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, B.; Jiao, K. Life cycle assessment of fuel cell, electric and internal combustion engine vehicles under different fuel scenarios and driving mileages in China. Energy 2020, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Luo, X. Environmental life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles from the current and future energy mix perspective. J Environ Manage 2022, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dér, A.; Erkisi-Arici, S.; Stachura, M.; Cerdas, F.; Böhme, S.; Herrmann, C. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in fleet applications. Sustainable Production, Life Cycle Engineering and Management 2018, 61–80.

- Fernando, C.; Soo, V. K.; Doolan, M. Life Cycle Assessment for Servitization: A Case Study on Current Mobility Services. Procedia Manuf 2020, 43, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltohamy, H.; van Oers, L.; Lindholm, J.; Raugei, M.; Lokesh, K.; Baars, J.; Husmann, J.; Hill, N.; Istrate, R.; Jose, D.; et al. Review of current practices of life cycle assessment in electric mobility: A first step towards method harmonization. Sustain Prod Consum 2024, 52, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Huang, K.; Wang, L. The environmental footprint of electric vehicle battery packs during the production and use phases with different functional units. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2021, 26, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagouz, N.; Onat, N. C.; Kucukvar, M.; Sen, B.; Kutty, A. A.; Kagawa, S.; Nansai, K.; Kim, D. Rethinking mobility strategies for mega-sporting events: A global multiregional input-output-based hybrid life cycle sustainability assessment of alternative fuel bus technologies. Sustain Prod Consum 2022, 33, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaça, M.; Santos, G.; Oliveira, M. S. A.; Coelho, M. C.; Correia, G. H. A. Life cycle assessment of shared and private use of automated and electric vehicles on interurban mobility. Appl Energy 2022, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, J. A comparative life cycle assessment on lithium-ion battery: Case study on electric vehicle battery in China considering battery evolution. Waste Management and Research 2021, 39, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Wu, C.; Feng, W.; You, K.; Liu, J.; Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Cheng, H. M. Impact of electric vehicle battery recycling on reducing raw material demand and battery life-cycle carbon emissions in China. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Guo, W.; Li, Q.; Meng, Z.; Liang, W. Life cycle assessment of lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide batteries and lithium iron phosphate batteries for electric vehicles in China. J Energy Storage 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayutthanabun, A.; Chinda, T.; Papong, S. End-of-life management of electric vehicle batteries utilizing the life cycle assessment. J Air Waste Manage Assoc 2025, 75, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, M. S.; Abdalla, A. M.; Abas, P. E.; Taweekun, J.; Reza, M. S.; Azad, A. K. Life Cycle Cost Assessment of Electric, Hybrid, and Conventional Vehicles in Bangladesh: A Comparative Analysis. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrauskienė, K.; Galinis, A.; Kliaugaitė, D.; Dvarionienė, J. Comparative environmental life cycle and cost assessment of electric, hybrid, and conventional vehicles in Lithuania. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, A. P.; Mastud, S. A. Comparative Environmental Impact Assessment of Battery Electric Vehicles and Conventional Vehicles: A Case Study of India. International Journal of Engineering, Transactions B: Applications 2023, 36, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Sharma, R.; Baral, B. Comparative life cycle assessment of conventional combustion engine vehicle, battery electric vehicle and fuel cell electric vehicle in Nepal. J Clean Prod 2022, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, D.; Oswald, M.; Draheim, P.; Pade, C.; Brand, U.; Vogt, T. Multidimensional assessment of passenger cars: Comparison of electric vehicles with internal combustion engine vehicles. Procedia CIRP 2020, 90, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thawadi, F. E.; Weldu, Y. W.; Al-Ghamdi, S. G. Sustainable Urban Transportation Approaches: Life-Cycle Assessment Perspective of Passenger Transport Modes in Qatar. In Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V., 2020; Vol. 48, pp. 2056–2062.

- Paulino, F.; Pina, A.; Baptista, P. Evaluation of alternatives for the passenger road transport sector in Europe: A life-cycle assessment approach. Environments - MDPI 2018, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Sousa, N.; Coutinho-Rodrigues, J. Quest for sustainability: Life-cycle emissions assessment of electric vehicles considering newer Li-ion batteries. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, B.; Tang, Y.; Evans, S. Environmental life cycle assessment of recycling technologies for ternary lithium-ion batteries. J Clean Prod 2023, 389, 136008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Wen, Z.; Bunn, D.; Li, Y. The economic and environmental impacts of shared collection service systems for retired electric vehicle batteries. Waste Management 2023, 166, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, P.; Garcia, R.; Kulay, L.; Freire, F. Comparative life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles addressing capacity fade. J Clean Prod 2019, 229, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, G.; Sánchez, A.; Rallo, H.; Corchero, C.; Amante, B. Comparative life cycle assessment of Li-Sulphur and Li-ion batteries for electric vehicles. Resources, Conservation and Recycling Advances 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, O.; Rodriguez, R.; Getz, J.; Panneerselvam, S.; Soudbakhsh, D. The impact of lightweighting and battery technologies on the sustainability of electric vehicles: A comprehensive life cycle assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2025, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-S.; Huang, G.-T.; Chang-Chien, C.-L.; Huang, L. H.; Kuo, C.-H.; Hu, A. H. The impact of passenger electric vehicles on carbon reduction and environmental impact under the 2050 net zero policy in Taiwan. Energy Policy 2023, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Salzinger, M.; Remppis, S.; Schober, B.; Held, M.; Graf, R. Reducing the environmental impacts of electric vehicles and electricity supply: How hourly defined life cycle assessment and smart charging can contribute. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, E.; Majed, N. Integrated life cycle sustainability assessment of the electricity generation sector in Bangladesh: Towards sustainable electricity generation. Energy Reports 2023, 10, 3993–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E. Y. C.; Ho, D. C. K.; So, S.; Tsang, C.-W.; Chan, E. M. H. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles using the greet model—a comparative study. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y. Life Cycle Assessment of Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles Considering Different Vehicle Working Conditions and Battery Degradation Scenarios. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L. L. P.; Lora, E. E. S.; Palacio, J. C. E.; Rocha, M. H.; Renó, M. L. G.; Venturini, O. J. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment of conventional vehicles with different fuel options, plug-in hybrid and electric vehicles for a sustainable transportation system in Brazil. J Clean Prod 2018, 203, 444–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekel, K.; Pauliuk, S. Prospective cost and environmental impact assessment of battery and fuel cell electric vehicles in Germany. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2019, 24, 2220–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchart-Korol, D.; Jursova, S.; Folęga, P.; Korol, J.; Pustejovska, P.; Blaut, A. Environmental life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in Poland and the Czech Republic. J Clean Prod 2018, 202, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Gao, L.; Xing, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S. The life cycle assessment and scenario simulation prediction of intelligent electric vehicles. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 6046–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Pagone, E. Cradle-to-Grave Lifecycle Environmental Assessment of Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 11027 2023, 15, 11027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M. S.; Sreenivasan, A. V.; Sharp, B.; Du, B. Well-to-wheel analysis of greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption for electric vehicles: A comparative study in Oceania. Energy Policy 2021, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, D.; Cornago, S.; Scaglia, P.; Brondi, C.; Low, J. S. C.; Ramakrishna, S.; Dotelli, G. Quantification of Non-linearities in the Consequential Life Cycle Assessment of the Use Phase of Battery Electric Vehicles. Frontiers in Sustainability 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmiroli, B.; Messagie, M.; Dotelli, G.; Van Mierlo, J. Electricity generation in LCA of electric vehicles: A review. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.-C.; Fan, Y.; Yao, X.; Fang, H.; Xu, C. Cost and environmental impacts assessment of electric vehicles and power systems synergy: The role of vehicle-to-grid technology. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2025, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicky, M.; Zeng, D.; Dong, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zwicky Hauschild, M. Are the electric vehicles more sustainable than the conventional ones? Influences of the assumptions and modeling approaches in the case of typical cars in China Are the electric vehicles more sustainable than the conventional ones? Influences of the assumptions and modeling approaches in the case of typical cars in China. Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolas Hill; Sofia Amaral; Samantha MorganPrice; Tom Nokes; Judith Bates; Hinrich Helms; Horst Fehrenbach; Kirsten Biemann; Nabil Abdalla; Julius Jöhrens (ifeu); et al. Determining the environmental impacts of conventional and alternatively fuelled vehicles through LCA; Directorate-General for Climate Policy, 2020.

- Electricity as a Vehicle Fuel. Current Methods for Life Cycle Analyses of Low-Carbon Transportation Fuels in the United States; National Academies Press: Washington DC, 2022; pp. 1–220. [Google Scholar]

- Rapa, M.; Gobbi, L.; Ruggieri, R. Environmental and Economic Sustainability of Electric Vehicles: Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Costing Evaluation of Electricity Sources. Energies 2020, Vol. 13, Page 6292 2020, 13, 6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P. K.; Bhat, M. Y.; Sajith, S. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles: a systematic review of literature. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2024, 31, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]