Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Area

Sampling, Collection and Identification

Water Physicochemical Analysis

Environmental Diversity Indices

Data and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Conflict of Interest

References

- Abowei, J.F.N. , and Sikoki, F.D. Impact of dredging on aquatic ecosystems in the Niger Delta. Journal of Environmental Protection 2017, 8(11), 1345–1356. [Google Scholar]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (23rd ed.). Accessed 23rd June 2017, 2025.

- Akintoye, O.A., and Obi, C.N. Water quality dynamics in the Niger Delta: Implications for aquatic ecosystems. Journal of Water Resource and Protection 2021, 13 (4), 245–260.

- Akinyemi, S.A., and Nwankwo, D.I. Seasonal dynamics of phytoplankton in the Ogun River, Nigeria. African Journal of Aquatic Science 2020, 45(3), 345–354.

- Barcelona Field Studies Centre, (2025.) Simpson’s Diversity Index. https://geographyfieldwork.com/Simpson’sDiversityIndex.html. Accessed 23 July, 2025.

- Baumgartner, M.T., Piana, P.A., Baumgartner, G., and Gomes, L.C. Zooplankton community structure in subtropical reservoirs: The role of environmental and morphometric factors. Hydrobiologia 2020, 847 (3), 805–821.

- Burian, A., Mauersberger, R., and Winder, M. Zooplankton community responses to environmental stressors in temperate lakes. Freshwater Biology 2020, 65(7), 1234–1246.

- Cefas. Relative Margalef diversity index - Marine online assessment tool. https://moat.cefas.co.uk/biodiversity-food-webs-and-marine-protected-areas/benthic-habitats/relative-margalef-diversity-index/. Accessed 23 July 2023, 2025.

- Davies, O.A., and Ugwumba, A.A.A. Plankton community structure in response to oil pollution in the Nun River, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management 2019, 23(6), 1075–1082.

- Dexter, E. , and Bollens, S.M. Modeling the trophic impacts of invasive zooplankton in a highly invaded river. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(12), e0243002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edegbene, A.O., Arimoro, F.O., and Odoh, O. Seasonal variation in macroinvertebrate and plankton communities in relation to water quality in a tropical river. Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology 2020, 20(4), 572–584.

- Edegbene, A.O. , Arimoro, F.O., and Odume, O.N. Exploring the distribution patterns of macroinvertebrates in response to water quality and habitat variables in tropical rivers. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2021, 193(5), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency-US.EPA. Climate Change Impacts and Risk Analysis (CIRA). https://www.epa.gov/cira. Accessed 23 June 2025, 2025.

- Ezenwa, I.M., and Omoigberale, M.O. Phytoplankton diversity in response to water quality in the Ethiope River, Nigeria. Journal of Aquatic Sciences 2019, 34(1), 15–24.

- Heys, K., Shore, R., Pereira, M., Jones, K. and Martin, F. (2016). Risk assessment of environmental mixture effects. Royal Society of Chemistry Adv. 6.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change-IPCC. (2021). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report. Https//www.ipcc.ch). Accessed 23 June, 2025.

- nyang A.I., Wang Y.S and Cheng H. (2022) Application of Microalgae Assemblages’ Parameters for Ecological Monitoring in Mangrove Forest. Frontiers in Marine Science. 9:872077.

- Isaksson, C. 2018. Impact of Urbanization on Birds: How They Arise, Modify and Vanish. Bird Species 235-257.

- Jacob, B.G, Astudillo O., Dewitte B, Valladares M., Alvarez-Vergara G., Medel C., Crawford, D.W., Uribe, E. and Yanicelli, B. (2024). Abundance and diversity of diatoms and dinoflagellates in an embayment off Central Chile (30°S): evidence of an optimal environmental window driven by low and high frequency winds. Frontiers in Marine Science. 11:1434007.

- Lee, S. (2025). Understanding Shannon-Wiener Index. Number Analytics. https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ultimate-guide-to-shannon-wiener-index. Accessed June 23, 2025.

- Nwankwoala, H.O., and Mmom, P.C. Environmental challenges of the Niger Delta: Implications for sustainable development. Journal of Environmental Protection 2019, 10(6), 801–815.

- Ogamba, E.N. , Izah, S.C., and Ofoni-Ofoni, A.S. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in fish species from the Niger Delta. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2021, 193(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ohimain, E.I. , Imoobe, T.O.T., and Benka-Coker, M.O. Eco-livelihood assessment of inland river dredging: The Kolo and Otuoke creeks, Nigeria, a case study. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 245, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ohimain, E.I., and Akinnibosun, H.A. Environmental impacts of oil exploration in the Niger Delta: A review. Journal of Ecology and Natural Environment 2020, 12(3), 92–102.

- Pandey, J., Singh, A., and Singh, R. BOD and plankton diversity: Indicator of water quality at river Ghaghara, India. Research Journal of Biology 2014, 2(2), 37-43.

- Qu, Y. , Wu, N., Guse, B., and Fohrer, N. Riverine phytoplankton shifting along a lentic-lotic continuum under changing environmental controls. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 634, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Righetti, D. , Vogt, M., Gruber, N., Psomas, A., and Zimmermann, N. E. Temperature is a key driver of marine phytoplankton diversity at the global scale. Science Advances 2022, 5(8), eaau6253. [Google Scholar]

- Sikoki, F.D. , and Zabbey, N. Environmental impacts of oil pollution on Niger Delta aquatic ecosystems. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 11(6), 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Statology. Simpson’s Diversity Index: Definition & Examples. https://www.statology.org/simpsons-diversity-index/. Accessed 23 July 2021, 2025.

- Udo, J.P. , and Akpan, E.R. Plankton community structure in a polluted tropical estuary. Journal of Environmental Biology 2021, 42(3), 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ugbomeh, A.P., and Atubi, A.O. Water quality and plankton dynamics in the Epie Creek, Niger Delta. Journal of Aquatic Sciences 2019, 34(2), 45–53.

- Uwadiae, R.E. Zooplankton community structure in response to environmental variables in the Lagos Lagoon. African Journal of Ecology 2020, 58(3), 567–576. [Google Scholar]

- Uzoekwe, S.A., Abdulsalam, R.R., and Onwudiegwu C.A. (2025). Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Concentrations in Rainwater and the Ecological and Health Effects on Inhabitants in Some Crude Oil Producing Communities of Niger-Delta. Abstract of Conference Proceedings of the ACS-Federal University Otuoke Chapter Conference 2025: Theme: Harnessing Green Chemistry and Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development.

- Wu, N., Qu, Y., Guse, B., and Fohrer, N. Ecological health evaluation of rivers based on phytoplankton biological integrity index. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 942205.

- Yang, J. , Zhang, Y., and Wang, H. Water quality and habitat drive phytoplankton taxonomic and functional group patterns in the Yangtze River. Ecological Processes 2021, 10(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zabbey, N. , and Uyi, H. Community responses to oil spill remediation in the Niger Delta. Environmental Development 2018, 26, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zabbey, N. , and Uzo, P. Plankton dynamics in response to oil pollution in the Niger Delta. Journal of Environmental Biology 2019, 40(4), 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Zabbey, N., and Tanee, F.B.G. Assessment of heavy metal pollution in the Bodo Creek, Niger Delta. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2019, 191(6), 1–14.

| Sampling Location | Location Code | Sample Points | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Otuaba Waterside (OTU) | L1 | Otuaba 1 Otuaba 2 |

4.7531° N, 6.5156° E |

| Community Waterside (COM) | L2 | Community 1 Community 2 |

4.7550° N, 6.5200° E |

| Azikiel Waterside (AZI) | L3 | Azikiel Water Side 1 Azikiel Water Side 2 |

4.7600° N, 6.5250° E |

| Location | Observations within and around locations |

|---|---|

| 1 | Human settlements, heaped refuse, floating and surrounding vegetation, canoes tied to bank, and an army lookout post. |

| 2 | Refuse was observed heaped at the bank, floating and surrounding vegetation, locales were seen bathing/washing (clothes and kitchen wares), canoes tied to the bank and observed human settlements. |

| 3 | Floating and surrounding vegetation, canoes tied to the bank and one single building was observed |

| Sample Location | Wind-Speed (km/hr) | Relative Humidity (%) | Atmospheric Temp. (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10-25 km/hr | 79%-95% | 23-28 °C |

| 2 | 10-25 km/hr | 80%-95% | 23-28 °C |

| 3 | 10-25 km/hr | 81%-95% | 23-28 °C |

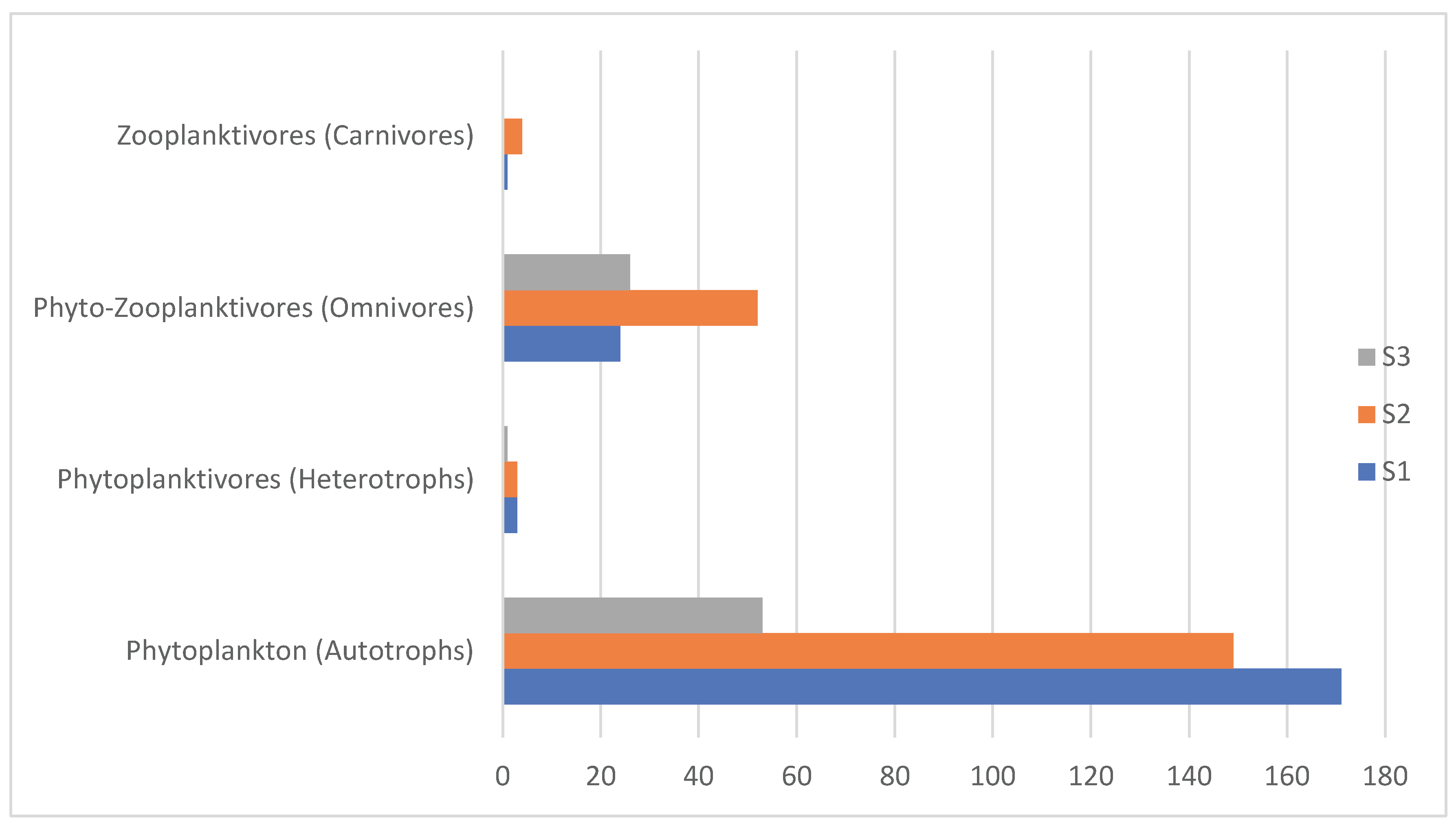

| Trophic Level | %Total | Species | L1 | % | L2 | % | L3 | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phytoplankton (Autotrophs) | 76.22% | 28 | 171 | 85.5% | 149 | 71.64% | 52 | 65.0% | 372 |

| Zooplankton | |||||||||

| Phytoplanktivores (Herbivores) | 1.64% | 5 | 4 | 2% | 3 | 1.44% | 1 | 1.25% | 8 |

| Phyto-Zooplanktivores (Omnivores/Protists) | 21.11% | 5 | 24 | 12% | 52 | 25% | 27 | 33.75% | 103 |

| Zooplanktivores (Carnivores) | 1.03% | 2 | 1 | 0.05% | 4 | 1.93% | 0 | 0% | 5 |

| Total | 100% | 40 | 200 | 100% | 208 | 100% | 80 | 100% | 488 |

| b: Phytoplankton Abundance and Trophic level (Autotrophic Level). | |||||||||

| Organisms/Location | L1-1 | L1-2 | L2-1 | L2-2 | L3-1 | L3-2 | |||

| Spirogyra grevillana | 22 | 11 | 13 | 9 | 3 | 5 | |||

| Spirogyra crassa | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Spirogyra dubia | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Nodularia sphaerocarpa | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Tradeliomonas subtilis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Lyngbya major | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Closterum intermediul | 7 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Closterum gracile | 5 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |||

| Cryptomonas magnsonii | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Clostridium juncundum | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Tradeliomonas volvoxina | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Raphidiopsis mediterranea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |||

| Tetracholomonas eu albiora | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Melosira pusilia | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ankistrodesmus falcatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Microasterias rotata | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Spirogyra princeps | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Tradeliomonas dubia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Tradeliomonas tamboricza | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Volvox sp | 6 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Euglena viridis | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Euglena deses | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Euglena caudata | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Closterum strigosum | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Pinnularia kapelica | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Navicula sp | 15 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 3 | |||

| Stephanodiscus sp | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Chlamydomonas sp | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| c: Zooplankton Abundance and Trophic Levels. | |||||||||

| Trophic Level/Organism/Location | L1-1 | L1-2 | L2-1 | L2-2 | L3-1 | L3-2 | |||

| Phytoplanktivores (Heterotrophs) | |||||||||

| Monostyla closterocerca | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Brachionus calyciflorus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Diaptomus binucleatus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Centropages aculeata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Rotaria neptunia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Phyto-Zooplanktivores (Omnivores) | |||||||||

| Vorticella spp | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | |||

| Paramecium spp | 11 | 8 | 7 | 15 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Amoeba spp | 5 | 6 | 7 | 19 | 5 | 9 | |||

| Stentor polymorphus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Eucyclops sporatus | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Zooplanktivores (Carnivores) | |||||||||

| Pleurotrocha denticulatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Cyclops scutifer | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sampling Location | Margalef Index (D) |

Shannon Index (H’) | Pielou’s Evenness (J) | Simpson Index (1-D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location 1 | 4.133 (P) 1.650 (Z) |

2.704 (P) 1.350 (Z) |

0.875 (P) 0.690 (Z) |

0.909 (P) 0.692 (Z) |

| Location 2 | 4.019 (P) 1.470 (Z) |

2.707 (P) 1.320 (Z) |

0.942 (P) 0.680 (Z) |

0.925 (P) 0.827 (Z) |

| Location 3 | 4.345 (P) 0.910 (Z) |

2.448 (P) 1.120 (Z) |

0.944 (P) 0.810 (Z) |

0.922 (P) 0.797 (Z) |

| Location | pH | BOD | Temp (oc) | COD (µS/cm) | TDS | DO | TURB (NTU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.5184 | 2.4mgll | 31oc | 3.3 µS/cm | 28.00ppm | 4.2mgll | 23.40 |

| 2 | 6.7190 | 2.4mgll | 31oc | 3.3 µS/cm | 20.00ppm | 4.2mgll | 23.46 |

| 3 | 6.8195 | 2.5mgll | 30oc | 3.1 µS/cm | 15ppm | 4.3mgll | 23.41 |

| Gender | N | Age Range | N | Occupation | N | Ethnicity | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 13 | 18-24 | 17 | Fisherman | - | Ijaw | 10 |

| Female | 8 | 29-38 | 4 | Farmer | 10 | Igbo | 4 |

| 39-46 | - | Employee | 2 | Yoruba | 2 | ||

| 49-58 | - | Entrepreneur | 5 | Bini | 1 | ||

| 59-68 | - | No response | 4 | Unidentified | 1 | ||

| Uhobo | 1 | ||||||

| Ika | 1 | ||||||

| Isoko | 1 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | |

| b: Ethnobiological Knowledge and Investigation. | |||||||

| Question/Observation | YES | NO | No Response | TOTAL | |||

| If water intake water or channel is polluted | 14 | 3 | 4 | 21 | |||

| Notice of change during the rainy season | 15 | 6 | 0 | 21 | |||

| Observed unusual events | 14 | 6 | 1 | 21 | |||

| Observation of times with fewer organisms | 10 | 10 | 1 | 21 | |||

| Do you carry out any domestic activities around the creek | 7 | 9 | 5 | 21 | |||

| Opinion on effect of socioeconomic activities around the creek | 17 | 0 | 4 | 21 | |||

| Did you find the questionnaire helpful | 19 | 1 | 1 | 21 | |||

| c: Responses to Change in Water Quality Causes. | |||||||

| Causes | Responses | ||||||

| Refuse dumping | - | ||||||

| Defecation | 3 | ||||||

| Oil pollution | 3 | ||||||

| Farm chemicals | 1 | ||||||

| Runoffs/water flow from outside the creek | 1 | ||||||

| No response | 1 | ||||||

| All of the above | 9 | ||||||

| Defecation and oil pollution | 3 | ||||||

| Refuse dumping and oil pollution | - | ||||||

| Refuse dumping and defaecation | - | ||||||

| d: Domestic and Personal Activities Carriedout. | |||||||

| Activities | Response | No response | |||||

| Washing clothes | - | 16 | |||||

| Washing kitchen and cooking wares | 1 | ||||||

| Bathing | 3 | ||||||

| Defecation | 1 | ||||||

| Refuse dumping | 1 | ||||||

| All of the above | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).