1. Introduction

Rainfall events can produce a variety of effects, depending on the specifics of a given system. On one hand, rainfall can lead to eutrophication as nutrients from nutrient-rich bottom layers become quickly available for cyanobacteria utilization [

1,

2]. On the other hand, rainfall may transport airborne pollutants to the ground and underground systems, thereby harming rivers and lakes [

3]. Rainfall events can also result in the mixing and re-suspension of dormant cyanobacteria [

4,

5], as well as light limitation under conditions of high nutrient supply [

6]. Furthermore, rainfall can cause prolonged turbidity and enhanced turbulence in water bodies through sediment input, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) input [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], and the re-suspension of sediments during storm events [

13]. This effect is often more pronounced in regions with poor land-use practices and management [

14].

In the short term, intense rainfall events can lead to lower total chlorophyll-a concentrations with increased diversity due to the absence of dominant cyanobacterial species [

15]. The influx of large volumes of water during these events can reduce algal biomass as a result of significant flushing rates [

10,

16,

17,

18], and it may take several days for a bloom to re-establish after being flushed out by heavy rainfall [

7]. This is especially pertinent following severe rainfall events. Generally, rainfall amounts are correlated with inflow volumes. However, this correlation may weaken if sufficient rain saturates the catchment area [

19]. In the long term, however, the increased input of nutrients such as phosphorus, nitrogen, and iron into water bodies during and after rainy [

5,

13,

20] can lead to nutrient enrichment. This not only enhances the system's capacity to support higher biomass but also favors the proliferation of cyanobacteria [

21].

Lake Erhai is the second-largest plateau freshwater lake in Yunnan Province, China. It belongs to the Lancang watershed, which covers an area of 2,565 km², receives an annual rainfall of 1,048 mm, and has a water volume of 27.7 billion m³. The rainy season in the Lake Erhai watershed primarily occurs between May and October, accounting for over 80% of the total annual precipitation [

22]. Due to its multiple functions, the lake is prone to agricultural non-point source pollution, with pollutant flows including both osmotic runoff and agricultural irrigation backflow [

23]. The primary pollution source for this lake originates from diffuse pollution caused by surface runoff and river inflow following rainfall. The lake has experienced continuous nutrient loading and is classified as eutrophication, with total nitrogen (TN) levels ranging from 0.39–0.60 mg/L and total phosphorus (TP) levels ranging from 0.004–0.028 mg/L [

24]. Moreover, Lake Erhai is distinguished by a clear division between its dry and rainy seasons. The physical and chemical conditions related to rainfall may vary significantly between these two periods, potentially influencing cyanobacterial dynamics [

21,

25]. Cyanobacterial blooms are common in the eutrophic waters of Lake Erhai, yet the effects of rainfall on the spatial distribution of algae and zooplankton remain poorly understood.

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the impact of rainfall on the spatial distribution of water quality parameters, plankton density, and biomass in Erhai Lake using monthly monitoring data from May 2016 to April 2017. It also sought to uncover the mechanism by which rainfall-induced changes in multiple environmental factors influenced the spatial variation in plankton communities. This research highlights key differences and provides valuable insights for the conservation and sustainable management of water resources in Lake Erhai.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

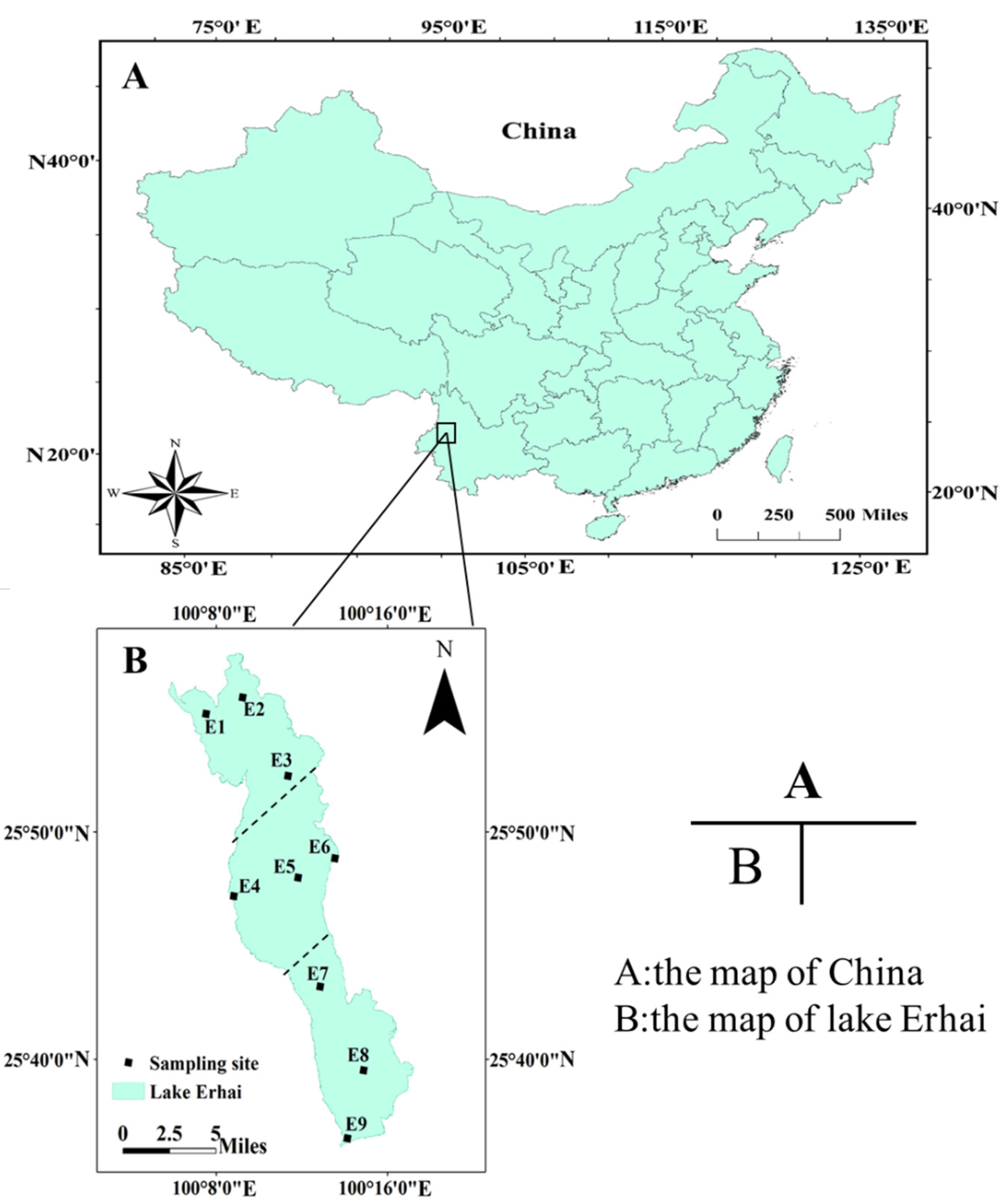

Lake Erhai (25°35′-58′ N, 100°05′-17′ E, 1966 m of altitude), located in Yunnan Province, southwestern China [

26], is a plateau freshwater lake currently in the early stages of eutrophication. It has a surface area of 251 km² (

Figure 1) and features a subtropical monsoon climate with an average annual temperature of 15.0°C, a mean depth of 10.5 m, and a maximum depth of 20.9 m.

The northern part of Lake Erhai is primarily fed by the Mi-Ju River, Luo-Shi River, and Yong-an River, collectively known as the "Northern Three Rivers" water system. The western side consists mainly of 18 mountain stream-type rivers perpendicular to the lake, forming the "Cang-Shan Eighteen Streams" water system. These streams pass through densely populated villages, have short flows, and carry relatively small water volumes [

27,

28]. In the southern region, the Bo-Luo River and its tributary, the Bai-ta River, dominate. These rivers flow through areas experiencing rapid urbanization and are transitioning from traditional agricultural pollution sources, such as farming and livestock breeding, to urban surface pollution [

29].

The "Northern Three Rivers" water system originates from mountainous vegetation and follows a longer course. Before entering the lake, it passes through three dam areas situated in low-lying terrain surrounded by mountainous vegetation, which constitutes 42%–56% of the total vegetation cover. This natural purification process across three levels ensures relatively good water quality. Conversely, the "Cang-Shan Eighteen Streams" water system originates from mountain vegetation and enters the lake via a buffer zone downstream of the Cang-Shan dams. This area experiences higher development intensity, with construction land accounting for an average of 13% of the total land area [

30].

2.2. Sampling Methods

Monthly sampling in Lake Erhai was conducted using a 5 L modified Patalas bottle sampler during both the rainy season (from May 2016 to October 2016) and the dry season (from November 2016 to April 2017). Nine sampling stations were established across the entire lake (

Figure 1), with three stations located in the northern region (E1–E3), three in the central region (E4–E6), and three in the southern region (E7–E9) [

31].

Water samples were collected from each site at the upper (i.e., 0.5 m below the water surface), middle (midway between the surface and the bottom), and lower (i.e., 0.5 m above the sediment surface) parts of the water column and then pooled together for subsequent analyses of the physicochemical parameters and plankton communities [

32]. We assessed water quality by testing indicators, including dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, transparency (Zsd), chlorophyll-

a (Chla) concentration and nutrient parameters. Nutrient parameters, including total nitrogen (TN), total dissolved nitrogen (TDN), total phosphorus (TP), total dissolved phosphorus (TDP) and specific forms of nitrogen such as ammonia-N (NH

4-N) and nitrate (NO

3−N), were tested according to [

33]. Chla was tested using a spectrophotometer [

33]. Water temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), conductivity (Cond) and pH values were determined using YSI Professional Plus (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, USA). Water transparency was measured using a 20 cm diameter Secchi’s disk and represented as Secchi’s depth (Z

Sd).

50 mL of quantitative crustaceans were collected by filtering 10 L integrated water samples through 25

# (69 um) plankton net and then fixed with 1 mL saturated formalin. All individuals were counted after precipitation for one day using an Olympus compound microscope (model BH2-RFC; Olympus America, Inc., Melville, NY, USA) at a total of 4×10 magnification in the samples to calculate density and biomass [

34,

35]. Within each sampling site, collecting 1 L of water samples for phytoplankton identification and counting. Phytoplankton communities were fixed with 1.5% Lugol’s iodine solution in situ and stored in the dark [

12].

2.3. Data Analysis

All results from sampling stations E1-E3 were averaged to represent the northern part of the lake, sampling stations E4-E6 were averaged to represent the central part of the lake, while the averaged results from E7-E9 represented the southern part. Significant differences between various indicators values at different seasons (factor 1) and three areas (factor 2) were calculated using a general linear model with a multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) by comparisons test (LSD) and expressed as means ± standard error (STDVE). The differences were considered significant at

p < 0.05, including Bonferroni adjustments. Statistical analyses mentioned above were undertaken using SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, IBM Inc.) 22.0 for Windows. Statistical figures were output by SPSS 22.0. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), a constrained ordination, was used to assess the relationships between physicochemical factors and the plankton biomass [

36]. This analysis was conducted using the CANOCO 5.0 (Microcomputer Power Company, Ithaca, NY, USA)

.

3. Results

3.1. Variations in Water Quality and Environmental Factors

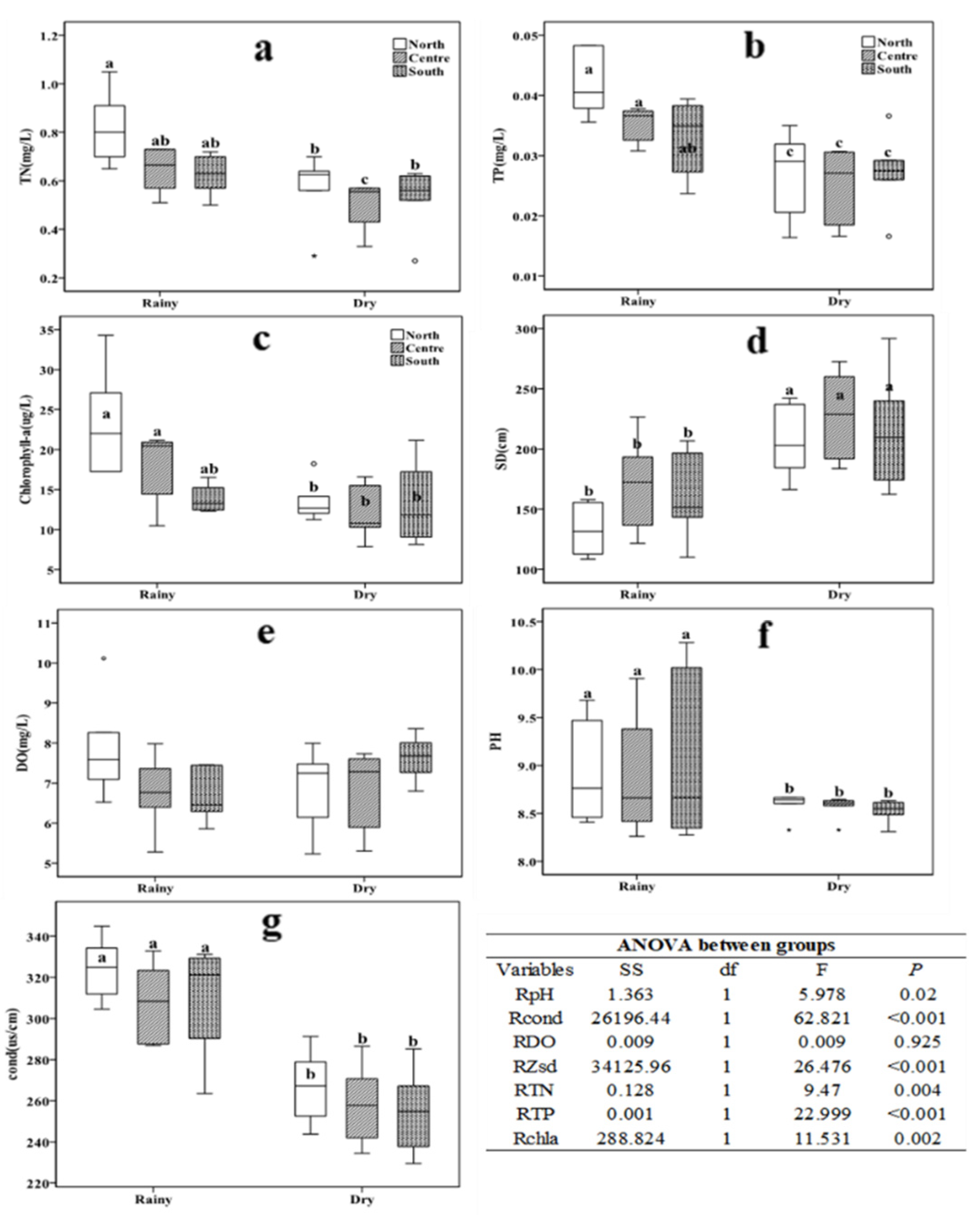

Mean values for all physical and chemical indicators measured in the rainy and dry seasons at different areas are shown in

Table 1. The average values of TN, TP, Chla

, and water temperature were 0.68 ± 0.03 mg/L, 0.04 ± 0.001 mg/L, 20.16 ± 1.52 μg/L and 22.5 ± 0.49 ℃, respectively, during the rainy season and 0.53 ± 0.03 mg/L, 0.03 ± 0.001 mg/L, 12.9 ± 0.86 μg/L and 14.6 ± 0.6 ℃, respectively, during the dry season. The water temperature in the rainy season was significantly higher than that in the dry season (df = 1, F = 98.211,

P < 0.001), however, there was no significant difference between the northern area, central area, and southern area (df = 2, F = 0.743,

p = 0.484). Furthermore, transparency of the rainy season was significantly lower than that of the dry season (df = 1, F = 24.131,

p < 0.001) (

Figure 2d).

During the entire period from May 2016 to April 2017, the mean value of total nitrogen in the northern area were significantly higher than the central and southern regions during the rainy season (

p < 0.05,

Figure 2a). However, there were no significant variations in northern and southern areas during the dry season (

p > 0.05,

Figure 2a). The total phosphorus (

p < 0.05,

Figure 2b) and Chla (

p < 0.05,

Figure 2c) concentrations in the northern area were significantly higher than in the southern part during the rainy season, but there was no significant difference in total phosphorus (

p > 0.05,

Figure 2b) and Chla (

p > 0.05,

Figure 2c) concentrations in the three areas during the rainy season. Moreover, although the transparency (

p < 0.05,

Figure 2d), pH (

p < 0.05,

Figure 2f) and conductivity (

p < 0.05,

Figure 2g) values of the rainy season were significantly different from the dry season, but there were no significant variations between the northern, central and the southern area. Generally, there were no significant variations in the DO during the dry and rainy season (

p > 0.05,

Figure 2e); however, the total nitrogen, total phosphorus, Chla, conductivity, and pH values significantly differed between the two seasons (

p < 0.05).

3.2. Spatial Distribution Differences of Plankton Density and Biomass in Rainy and Dry Seasons

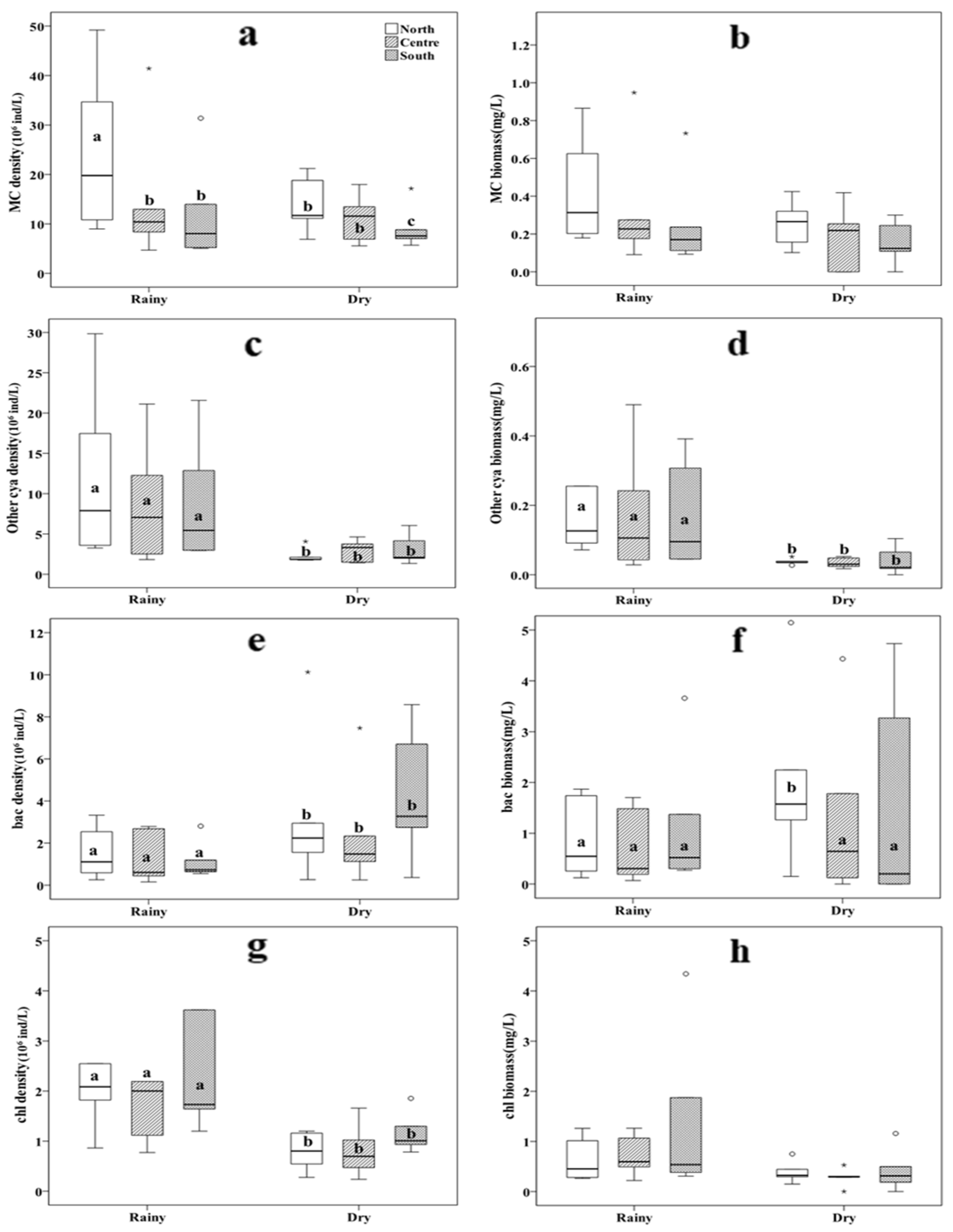

During the rainy season, the density of

Microcystis in the northern area was significantly higher than that in the central and southern areas (

p < 0.05,

Figure 3a); however, during the dry season, the density of

Microcystis in the south area was significantly lower than that in the central and northern areas (

p < 0.05,

Figure 3a). Besides, the ANOVA tests also revealed that the density and biomass of other Cyanobacteria, as well as the density of Chlorophyta and Bacillariophyta, were significantly different in the rainy and dry seasons (

p < 0.05,

Figure 3c,

Figure 3d,

Figure 3e,

Figure 3g); however, only the Bacillariophyta biomass was significantly higher in the northern area than in the central and southern areas during the dry season (

P<0.05,

Figure 3f). There was no significant difference in biomass of

Microcystis and Chlorophyta between the rainy season and dry season (

p > 0.05,

Figure 3b,

Figure 3h).

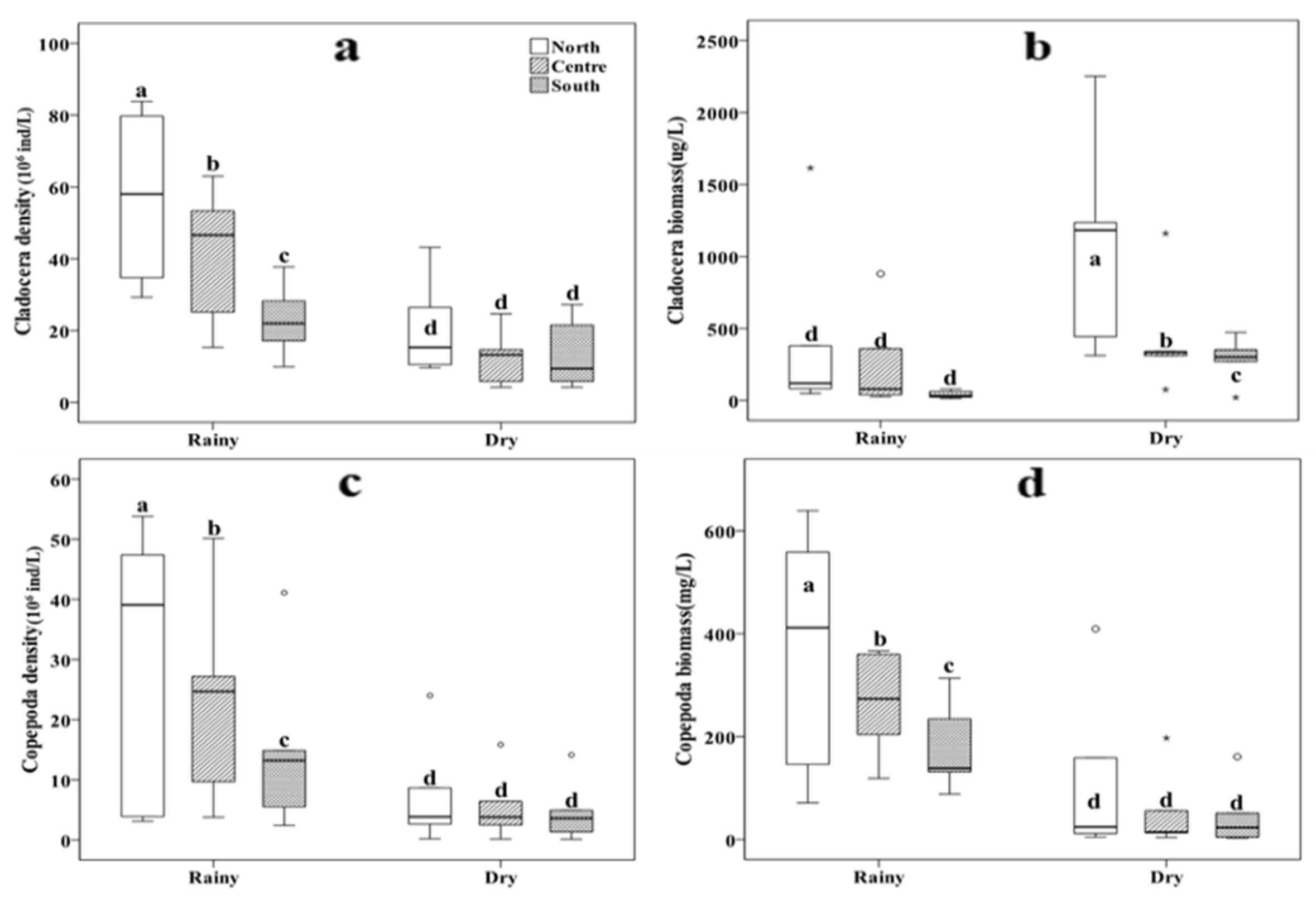

All results of Cladocera and copepods density and copepods biomass indicated that the northern area was significantly higher than the central area. The central area was considerably higher than the southern area during the rainy season (

p < 0.05,

Figure 4a,

Figure 4c,

Figure 4d). However, there was no significant difference in the three areas during the dry season (

p > 0.05,

Figure 4a,

Figure 4c,

Figure 4d). Cladocera density and biomass results also show that the density of Cladocera in the rainy season was significantly higher than in the dry season, but the biomass of Cladocera in the rainy season was significantly lower than that in the dry season (

p < 0.05,

Figure 4b). This result was that the rainy season was mainly dominated by small Cladocera, while large Cladocera mainly dominated the dry season.

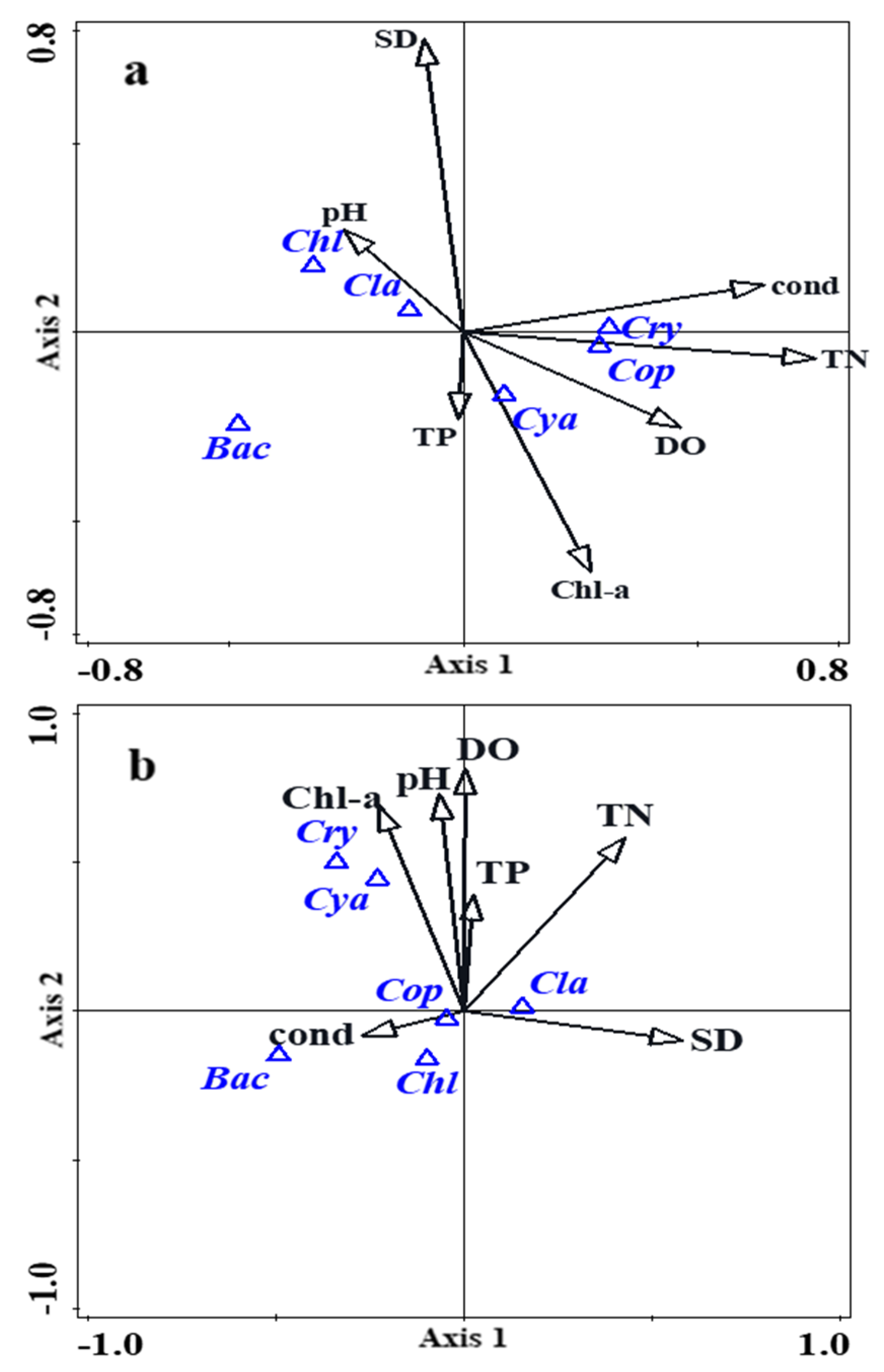

3.3. The Relationship Between Plankton Biomass and Environmental Factors in Canonical Correspondence Analysis

All the canonical axes significantly accounted for 33.7% (

pseudo-F = 5.1,

p < 0.01) of the plankton taxa biomass in the rainy season and 55.1% (

pseudo-F = 11.7,

p < 0.01) in the dry season. The first axis and second axis significantly explained 18.77% (

pseudo-F = 16.2,

p < 0.01) and 9.36% (

pseudo-F = 9.1,

p < 0.01) of the variation, respectively, during the rainy season (

Table 2), which was correlated with TN, SD, DO, PH and Chla (

Figure 5b). The first axis and second axis significantly explained 25.71% (

pseudo-F = 23.9,

p < 0.01) and 6.35% (

pseudo-F = 6.4,

p < 0.05) of the variation, respectively, during the dry season (

Table 2), which was correlated with TN, Cond, DO, Chla and SD (

Figure 5a). The relationship between the plankton taxa and environmental factors were apparent in the CCA analysis. Whether in the rainy season or the dry season, plankton taxa biomass (Cyanophyta, Cryptophyta, Cladocera, Copepods) were correlated with TN, Chla, DO and SD, and not correlated with TP.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Spatial Distribution Differences in Environmental Factors

Our results indicate that nutrient concentrations during the rainy season were significantly higher than those in the dry season. Moreover, nutrient levels in the northern region of Lake Erhai were considerably higher than in the southern area during the rainy season. This suggests that rainfall can accelerate the flow of river sewage into Lake Erhai. The ecosystem of Lake Erhai exhibits pronounced seasonal variations due to the subtropical rainfall climate. The Water Environment Monitoring Center of Dali monitored 23 major streams around Lake Erhai during both the dry and rainy seasons. The findings revealed that rivers flowing into the northern part of the lake contribute 47.0% and 28.7% of the total nitrogen and total phosphorus loads entering Lake Erhai, respectively [

37]. Based on this, some researchers proposed a hypothesis suggesting that external nutrients from storm runoff in the upper watershed may also increase nutrient concentrations in the Yang-He reservoir, as evidenced by a sudden rise in TN on August 5 and TP on July 29 [

38]. Our results further confirm that rainfall accelerates the flow of sewage from upstream rivers into Lake Erhai, as demonstrated by the significant increase in TN and TP concentrations in the northern part of Lake Erhai during the rainy season.

4.2. The Spatial Distribution Differences in Plankton Biomass and Density

Previously study reported that the phytoplankton community in Lake Erhai exhibited significant spatial distribution differences between rainy and dry seasons, with these variations primarily attributed to rainfall runoff [

28]. Similarly noted that rainfall can create favorable conditions for cyanobacterial growth due to increased nutrient input into water bodies during heavy rain events [

21]. Furthermore, a higher frequency of smaller rain events or wet days can also promote cyanobacterial proliferation, as they efficiently utilize nutrients introduced by rainfall, particularly when stratification remains stable. Our findings demonstrated that the density and biomass of dominant phytoplankton species were higher during the rainy season than during the dry season. some researchers corroborated this observation, showing significant seasonal differences in phytoplankton biomass and density [

39]. Additionally, our results revealed that Cladocera exhibited high density but low biomass in the rainy season, contrasting with the dry season where the opposite was observed. This suggests that an increase in water nutrient concentration may lead to the succession of large Cladocera species being replaced by smaller ones, resulting in high density but lower biomass. Previous studies have suggested that increased eutrophication could drive plankton communities toward dominance by smaller Cladocera, aligning well with our findings [

32]. Moreover, research has indicated that under conditions of low Cladocera biomass, Copepod biomass tends to increase due to competitive interactions, which is largely consistent with our results [

40].

4.3. The Influence of Environmental Factors on the Spatial Distribution of Plankton Biomass

All canonical axes together significantly explained 33.7% (

pseudo-F = 5.1,

p < 0.01) of the plankton taxa biomass variation during the rainy season and 55.1% (

pseudo-F = 11.7,

p < 0.01) during the dry season. In the rainy season, the first and second axes accounted for 18.77% (

pseudo-F = 16.2,

p < 0.01) and 9.36% (

pseudo-F = 9.1,

p < 0.01) of the variation, respectively, respectively, and were correlated with TN, SD, DO, pH, and Chla. During the dry season, the first and second axes explained 25.71% (

pseudo-F = 23.9,

p < 0.01) and 6.35% (

pseudo-F = 6.4,

p < 0.05) of the variation, respectively, and were associated with TN, Cond, DO, Chla and SD. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) revealed clear relationships between plankton taxa and environmental factors. Regardless of the season, Cyanophyta, Cryptophyta, Cladocera, and Copepods were positively correlated with TN, Chla, DO, and SD but showed no significant correlation with TP. Previously study demonstrated that dominant Chlorophyta species, such as

Psephonema aenigmaticum and

Mougeotia, were significantly influenced by TN [

41]. The CCA plot further illustrated the relationships between phytoplankton and environmental factors. In our study, Cyanophyta exhibited a strong association with TN and DO, likely due to the nitrogen-fixing capabilities of the predominant cyanobacterial species,

Aphanizomenon, which thrives in low-nitrogen environments [

42]. According to the prediction model, TN remains a critical factor influencing both the density and biomass of Chlorophyta in Lake Erhai [

41]. This aligns with previous studies indicating that nitrogen concentration is more influential than phosphorus in this lake, contrasting with findings from other lakes [

43]. Therefore, controlling nitrogen inputs into the Lake Erhai Basin is essential for maintaining ecological balance.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we investigated the spatial distribution characteristics of water quality parameters, plankton biomass, and density in Lake Erhai over a one-year period from May 2016 to April 2017, covering both the rainy and dry seasons. Significant spatial differences were observed in water quality, plankton density, and biomass within Lake Erhai during these two seasons (p < 0.05). During the rainy season, TN, TP, and Chl-a concentrations exhibited significant variations across three regions of the lake (p < 0.05). Additionally, the distribution of Microcystis, Cladocera density, and copepod biomass and density showed significant differences among the three areas during the rainy season. In contrast, only the distribution of Cladocera biomass demonstrated significant variation across the three regions during the dry season (p < 0.05). Canonical correspondence analysis revealed that dominant plankton taxa (Cyanophyta, Cryptophyta, Cladocera) were significantly correlated with TN, SD, DO, pH, and Chla during the rainy season, while being significantly associated with TN, Cond, DO, Chla, and SD during the dry season. Regardless of the season, no significant correlation was found between plankton taxa and TP. The findings of this study can provide crucial information for the effective management and protection of water quality in Lake Erhai and its inflowing tributaries within the watershed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G. and C.Y.; methodology, C.Y.; software, C.Y.; formal analysis, C.Y.; investigation, C.Y., J.Y., Y.Y. and L.G.; data curation, C.Y. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.G.; supervision, L.G.; funding acquisition, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Water Pollution Control and Management Technology Major Projects (Grant 2012ZX07105-004), the Key Project of Anhui Provincial Department of Education (2023AH052248), Doctoral Research Initiation Fund of Suzhou University (2023BSK007) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (2023M743728).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to YanJin Che for help in the field investigations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prepas, E.E.; Charette, T. Worldwide eutrophication of water bodies: Causes, concerns, controls. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Holland, H.D., Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier, 2005; pp. 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Garnett, C.; Moore, M.R.; Florian, P. The predicted impact of climate change on toxic algal (Cyanobacterial) blooms and toxin production in Queensland. Environ. Health-Glob 2001, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.P. Urbanization and Urban Water Environment. Urban environment and urban ecology 1998, 11, 20–22. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Fabbro, L.D.; Duivenvoorden, L.J. Profile of a bloom of the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Woloszynska) Seenaya and Subba Raju in the Fitzroy River in tropical central Queensland. Mar. Freshwater Res. 1996, 47, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E.; Belay, A. Species composition and phytoplankton biomass in a tropical African Lake (Lake Awassa, Ethiopia). Hydrobiologia, 1994, 288, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Waal, D.B., Verspagen, J.M.H., Lurling, M., Van Donk, E., Visser, P.M., Huisman, J. The ecological stoichiometry of toxins produced by harmful cyanobacteria: an experimental test of the carbon-nutrient balance hypothesis. Ecol. Let 2009, 12, 1326–1335. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.Y., Chung, A.S., Oh, H.M. Rainfall, phycocyanin, and N: P ratios related to cyanobacterial blooms in a Korean large reservoir. Hydrobiologia 2002, 474, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, C.C.; Giani, A. Seasonal variation in the diversity and species richness of phytoplankton in a tropical eutrophic reservoir. Hydrobiologia 2001, 445, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.C. Cladoceran periodicity patterns in relation to selected environmental factors in two cascading warm-water reservoirs over a decade. Hydrobiologia 2004, 526, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.J.; Poplawski, W. Understanding and management of cyanobacterial blooms in sub-tropical reservoirs of Queensland, Australia. Water Sci. Technol. 1998, 37, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, D.W. Lakes as sentinels and integrators for the effects of climate change on watersheds, airsheds, and landscapes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009, 54, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.R., Lv, H., Alain, I., Liu, L.M., Yu, X.Q., Chen, H.H., Yang, J. Disturbance-induced phytoplankton regime shifts and recovery of cyanobacteria dominance in two subtropical reservoirs. Water res. 2017, 120, 52–63. [CrossRef]

- James, R.T., Chimney, M.J., Sharfstein, B., Engstrom, D.R., Schottler, S.P., East, T., Jin, K.R. Hurricane effects on a shallow lake ecosystem, Lake Okeechobee, Florida (USA). Fund. Appl. Limnol. 2008, 172, 273–287. [CrossRef]

- Hendry, K., Sambrook, H., Underwood, C., Waterfall, R., Williams, A. Eutrophication of Tamar Lakes (1975-2003): a case study of land-use impacts, potential solutions and fundamental issues for the water framework directive. Water Environ. J. 2006, 20, 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Bouvy, M., Molica, R., De Oliveira, S., Marinho, M., Beker, B. Dynamics of a toxic cyanobacterial bloom (Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii) in a shallow reservoir in the semi-arid region of northeast Brazil. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 1999, 20, 285–297. [CrossRef]

- Bouvy, M., Nascimento, S.M., Molica, R.J.R., Ferreira, A., Huszar, V., Azevedo, S.M.F.O. Limnological features in Tapacura reservoir (northeast Brazil) during a severe drought. Hydrobiologia 2003, 493, 115–130. [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, C.C., Giani, A. Phytoplankton community in the tropical lake of Lagoa Santa (Brazil): conditions favoring a persistent bloom of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Limnologica 2009, 39, 264–272. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, B.A., Simonsen, P. Disturbance events affecting phytoplankton biomass, composition and species-diversity in a shallow, eutrophic, temperate lake. Hydrobiologia 1993, 249, 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.P., Baxter, G. Interannual variability in phytoplankton biomass and species composition in a subtropical reservoir. Fresh. Biol. 1996, 35, 545–560. [CrossRef]

- Zaw, M., Chiswell, B. Iron and manganese dynamics in lake water. Water Res. 1999, 33, 1900–1910. [CrossRef]

- Reichwaldt, E.S.; Ghadouani, A. Effects of rainfall patterns on toxic cyanobacterial blooms in a changing climate: between simplistic scenarios and complex dynamics. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1372–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.H. Study on hydrological characteristics and non-point source pollution load in the Erhai lake watershed. Yunnan environmental protection 1992, 2, 25–33. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.S.; Ni, X.Y. The status of agriculture non-point pollution in watershed of Lake Erhai. Agricultural Environment and Development (in Chinese). 1999, 2, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.L., Jiang, Y.J., Song, G.F., Tan, W.H., Zhu, M.L., Li, R.H. Variation of Microcystis and microcystin coupling nitrogen and phosphorus nutrient in Lake Erhai, drinking water source in Southwest Plateau, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 9887–9898. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Wang, Y.C., Hu, M.M., Li, Y.H., Liu, Y.D., Shen, Y.W., Li, G.B., et al. Succession of the phytoplankton community in response to environmental factors in north Lake Erhai during 2009–2010. Fresen. Environ. Bull. 2011, 20, 2221–2231.

- Chu, X.L.; Chen., Y.Y. The Fishes of Yunnan; (in Chinese). Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.Y., Zhang, W.T., Xing, Y., Qu, J.T., Li, K., Zhang, Q., Xue, W. Spatial distribution of water quality parameters of rivers around Erhai Lake during the dry and rainy seasons. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 7423–7430. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., Hou, Z.Y., Li, Z.K., Chu, Z.S., Yang, P.P., et al. Succession of phytoplankton functional groups and their driving factors in a subtropical plateau lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631-632, 1127–1137. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S., Pang, Y., Chu, Z.S., Hu, X.Z., Sun, L., Xue, L.Q. Response of inflow water quality to land use pattern in northern watershed of Lake Erhai. Environmental Science, (in Chinese). 2016, 37, 2947–2956.

- Pang, Y. , Xiang, S., Chu, Z.S., Xue, L.Q., Ye, B.B. Relationship between agricultural land and water quality of inflow river in Erhai Lake basin. Environmental Science, 2015, 36, 4005–4011. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Xu, K.C., Wang, S.R., Wang, S.H., Li, Y.P., Li, Q.C., Zhu, M. Characteristics of dissolved organic nitrogen in overlying water of typical lakes of Yunnan Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 84, 727–737. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Xie, P., Zhao, D.D., Zhu, T.S., Guo, L.G., Zhang, J. Eutrophication strengthens the response of zooplankton to temperature changes in a high-altitude lake. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 6690–6701. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, A.E.; Clesceri, L.S.; Eaton, A.D. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.J., Guo, L.G., Yi, C.L., Luo, C.Q., Ni, L.Y. Physiochemical process, crustacean zooplankton and Microcystis changes in water column after introduction of silver carp, an in-situ enclosure experiment to control cyanobacteria bloom at Meiliang Bay, Lake Taihu. Scientifica 2017, 2017, 9643234–9643243. [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.J., He, W.C., Guo, L.G., Gong, L., Yang, Y.L., Yang, J.J., Ni, L.Y., Chen, Y.S., Jeppesen, E. Can top-down effects of planktivorous fish removal be used to mitigate cyanobacterial blooms in large subtropical highland lakes? Water Res. 2022, 218, 118483. [CrossRef]

- Braak, T.; Smilauer, P. Canoco reference manual and user’s guide: software for ordination, version 5.0; microcomputer power: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.Z.; Jin, X.C.; Zhao, J.Z. Ecological protection and sustainable utilization of Erhai Lake, Yunnan. Environmental Sciences, (in Chinese). 2005, 26, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, T.X.; Xie, P.; Guo, L.G.; Chu, Z.S.; Liu, M.H. Phytoplankton dynamics and their equilibrium phases in the Yanghe Reservoir, China. J. Fresh. Ecol. 2014, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.J., Jiang. Impacts of Environmental Variables on a Phytoplankton Community: A Case Study of the Tributaries of a Subtropical River, Southern China. Water 2018, 10, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.P.; Wei, Z.H.; Wu, Q.T.; Han, B.P.; Lin, Q.Q. Response of Planktonic Copepods to Seasonal Fishing Moratorium in Erhai Lake, Yunnan, China. Chinese J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2012, 18, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Shen, H.; Deng, X.W. Use the predictive models to explore the key factors affecting phytoplankton succession in Lake Erhai, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2018, 25, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburn, M.; Lewis, W.M.; McCutchan, J.H. Comparative adaptations of Aphanizomenon and Anabaena for nitrogen fixation under weak irradiance. Fresh. Biol. 2012, 57, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elser, J.J.; Bracken, M.E.; Cleland, E.E. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).