1. Introduction

UAV endurance is constrained by battery capacity, typically 30–45 minutes under payload. Static charging and base-only hot-swap introduce downtime that interrupts critical missions. A mobile Flying Battery UAV (FB-UAV) can rendezvous with a distressed UAV (DU) to deliver energy in the field. This mid-flight rescue mission offers UAV pilots an opportunity to demonstrate emergency procedures while ensuring safety, security, and reliability (Buidin & Mariasiu, 2021; Hwang et al., 2018). Recent advances in thermal management (Coutinho et al., 2023) and solar-powered endurance systems (Khan & Anwar, 2023; Sornek et al., 2025) make the flying battery concept technically feasible for long-duration, real-time rescue scenarios.

BVLOS Pilot Qualification

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly vital to emergency management due to their ability to deliver situational awareness, assess risks, and provide logistics support. Visual Line of Sight (VLOS) operations remain constrained by range, while Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations enable broader coverage and safer missions in inaccessible areas (Clothier et al., 2015; Perez-Grau et al., 2017). Integrating FB-UAVs into BVLOS missions requires both endurance innovations and qualified operators who can manage in-flight rescues under regulatory frameworks (Azad et al., 2024; Baidya et al., 2024).

Regulatory Dimension of BVLOS Pilot Qualification

BVLOS operations are governed by strict regulatory frameworks to ensure integration with manned aviation. Authorities such as the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) enforce qualification standards that address airspace safety, pilot training, and operational protocols (FAA, 2020; EASA, 2021; ICAO, 2020). These frameworks also align with broader safety mandates such as dangerous goods transport (ICAO, 2023) and perishable cargo handling (IATA, 2024; EMA, 2024).

This table which follows highlights convergence (all require DAA, contingency planning, and pilot training) and differences (FAA waiver-based, EASA scenario/risk-based, ICAO harmonization)

Table 1.

BVLOS Pilot Qualification Requirements Comparison.

Table 1.

BVLOS Pilot Qualification Requirements Comparison.

| Requirement |

FAA (U.S.) – Part 107 Waivers |

EASA (Europe) – U-Space/SC-VTOL |

ICAO – UAS Toolkit / SORA |

| Certification |

Remote Pilot Certificate (Part 107) + BVLOS waiver |

Open/Specific/Certified categories; BVLOS in “Specific” or “Certified” |

Global alignment; recommends state-issued certification |

| Airspace Access |

BVLOS waiver required; restricted to approved corridors |

U-space integration with remote ID, e-conspicuity |

Requires risk assessment for cross-border ops |

| Detect-and-Avoid (DAA) |

Must demonstrate reliable DAA tech |

Mandatory geofencing + DAA compliance |

Emphasis on remain-well-clear (RWC) protocols |

| Command & Control (C2) |

Reliable C2 link; redundancy required |

Multiple comm. links (LTE/5G, SATCOM) |

Requires redundancy & spectrum coordination |

| Emergency Procedures |

Lost-link and contingency plan mandatory |

Predefined contingency volumes & safe landing zones |

State-level emergency/contingency framework |

| Training |

Part 107 + BVLOS-specific training modules |

EASA-approved training organizations (ATO) |

ICAO recommends standardized pilot training |

| Operational Approval |

Waiver per mission scenario |

Standard scenarios or SORA-based risk assessment |

State-based approvals guided by ICAO RPAS Panel |

This table highlights convergence (all require DAA, contingency planning, and pilot training) and differences (FAA waiver-based, EASA scenario/risk-based, ICAO harmonization).

Existing Methods in UAV Emergency Operations

VLOS: Localized missions under direct sight.

Extended VLOS (EVLOS): Use of observers to extend range.

Tethered UAVs: Persistent coverage, limited mobility.

Autonomous BVLOS: Sensor-equipped, regulation-compliant UAVs (Zhou et al., 2021).

Swarm Operations: Coordinated UAV clusters for scalable coverage (Campion et al., 2018).

Research into FireDrone platforms demonstrates UAV adaptability to extreme hazard conditions (Häusermann et al., 2023), while UAV-based environmental sampling and monitoring validate multipurpose applications for rescue operations (Chen et al., 2022; Grandy et al., 2020). These methods provide a foundation for FB-UAV emergency interventions.

Benefits of BVLOS Operations

Extended Coverage: Wide-area disaster monitoring.

Safety: Reduced human risk in hazardous zones.

Efficiency: Real-time situational awareness and logistics.

Integration: Compatibility with AI-enabled swarms and communication relays (Restas, 2015).

Drone-based health and supply logistics have proven user acceptance and cost-effectiveness in disaster contexts (Fink et al., 2024; Ospina-Fadul et al., 2025), reinforcing the benefits of BVLOS operations that integrate FB-UAVs.

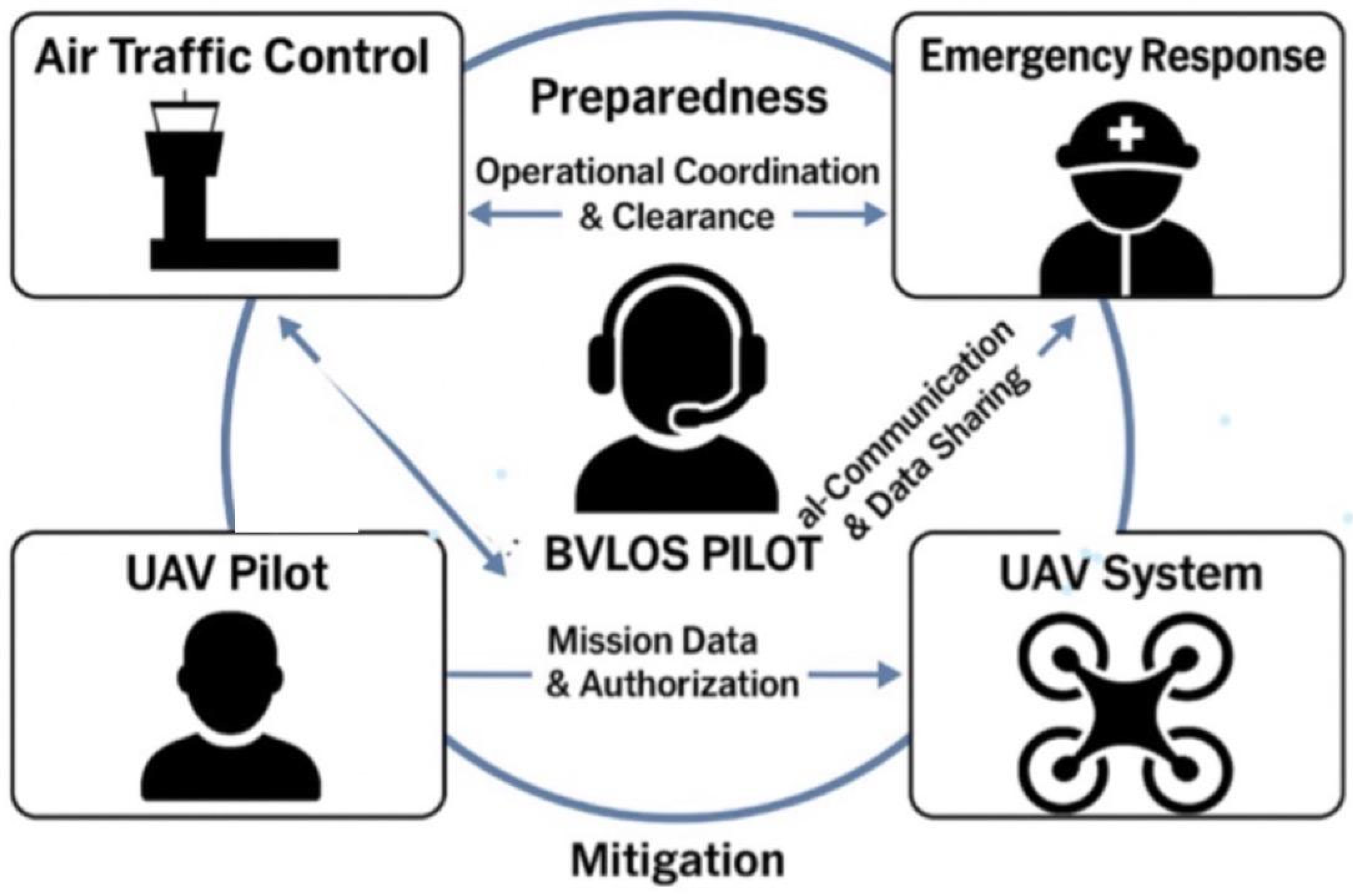

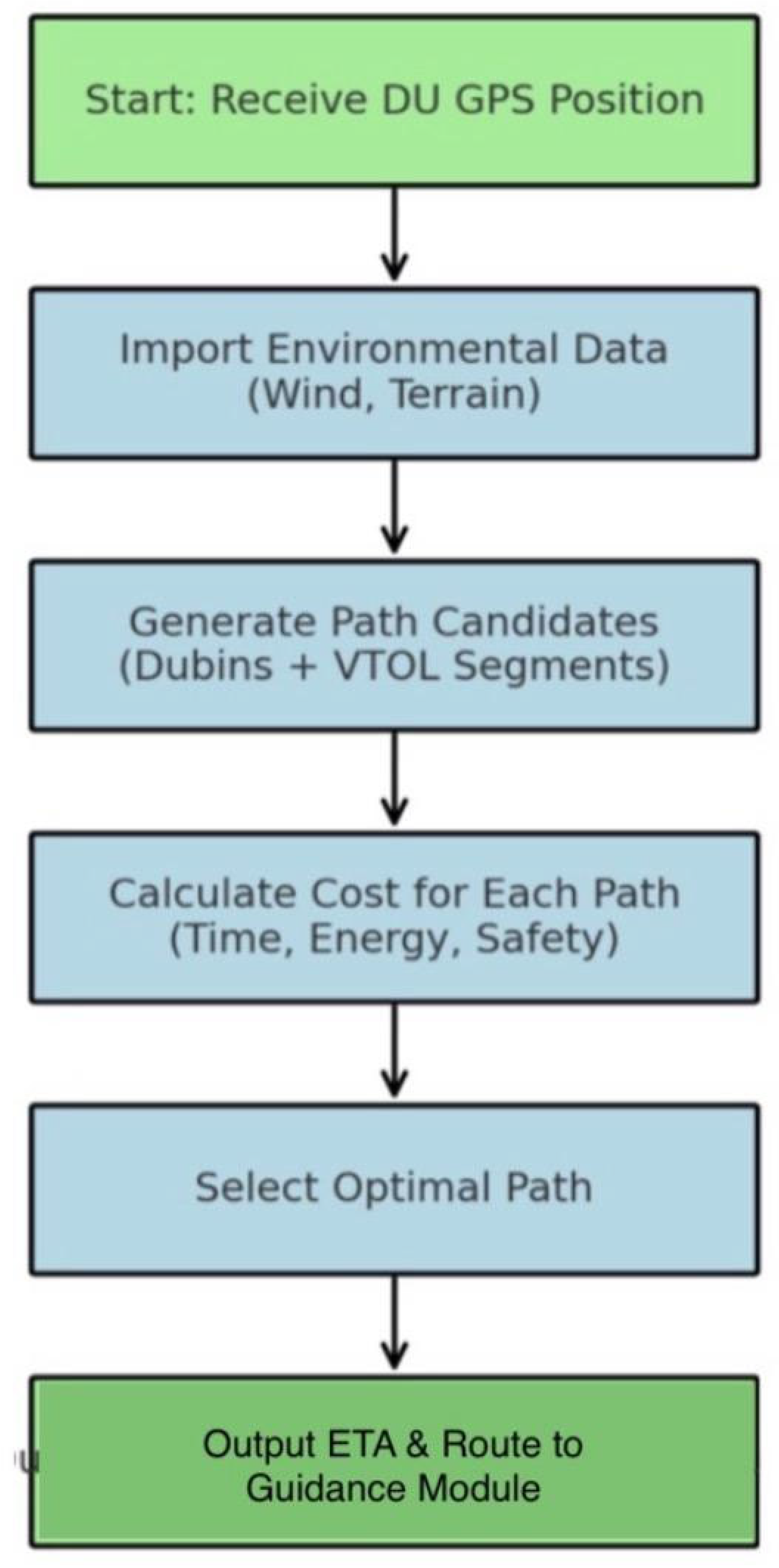

Phases of Emergency and the Role of BVLOS Pilots

Preparedness: Flight corridor planning, risk mapping, regulatory clearance.

Response: Live data feeds, search and rescue, supply delivery.

Recovery: Post-disaster inspection of infrastructure.

Mitigation: Long-term monitoring of vulnerable areas (Silvagni et al., 2017).

BVLOS pilots act as both technical operators and regulatory managers, ensuring compliance with national and international aviation frameworks.

Figure 1.

BVLOS Pilot Workflow in Emergency Response Actions.

Figure 1.

BVLOS Pilot Workflow in Emergency Response Actions.

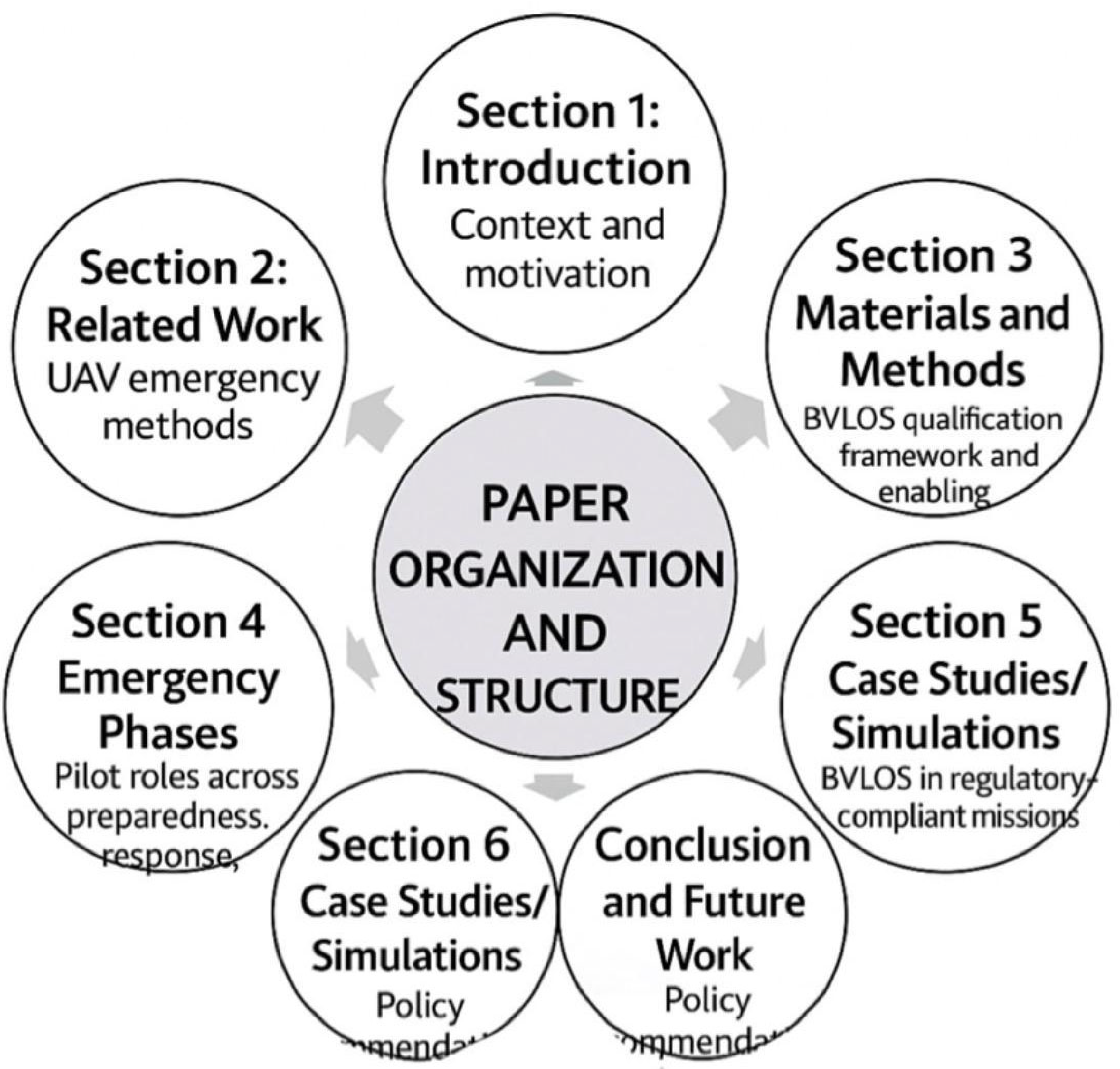

Paper Organization and Structure

The study is organized into clearly defined sections and subsections to ensure logical flow and coherence. In addition to the abstract and keywords, the introduction provides essential background on UAV emergency response, with emphasis on BVLOS pilot credentials and the phases of emergency management when a UAV is in distress. This section also reviews the frameworks established by leading regulatory agencies, including the FAA (2020), EASA (2021), and ICAO (2020).

The organization of the paper is as follows:

Section 1: Introduction – Context and motivation.

Section 2: Related Work – UAV emergency methods and regulatory foundation.

Section 3: Materials and Methods – BVLOS qualification framework and enabling technologies.

Section 4: Emergency Phases – Pilot roles across preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation.

Section 5: Benefits and Challenges – Operational and regulatory considerations.

Section 6: Case Studies/Simulations – BVLOS in regulatory-compliant missions.

Section 7: Conclusion and Future Work – Policy recommendations and research directions.

Figure 2.

Paper Organization and Structure.

Figure 2.

Paper Organization and Structure.

2. Related Work

2.1. Battery and Thermal Management

A central limitation in UAV endurance is the trade-off between battery energy density and heat dissipation. Lithium-ion and lithium-polymer technologies remain the dominant energy sources for UAVs, but their high energy output is constrained by thermal risks under heavy load and extended missions. Effective thermal management systems are therefore crucial to avoid overheating and ensure continuous in-flight energy transfer during rescue missions.

Buidin and Mariasiu (2021) review state-of-the-art battery thermal management systems, highlighting liquid-cooling, air-cooling, and phase-change materials as leading approaches for mitigating thermal risks. For hybrid-electric and high-power systems, Coutinho et al. (2023) provide insights into multi-layered thermal management that balance structural constraints with battery protection. At higher altitudes, thermal regulation becomes even more critical, as demonstrated by Beneitez Ortega et al. (2023), who analyzed solar-powered platforms where temperature differentials significantly affect performance. Together, these studies emphasize that a Flying Battery UAV must integrate adaptive cooling mechanisms to remain reliable during emergency deployments.

2.2. Solar-Powered and Endurance UAVs

Rescue UAVs require extended endurance to meet the operational demands of mid-flight refueling missions. While conventional UAVs are restricted to 30–45 minutes of flight under payload, advances in solar integration and lightweight composite materials provide new avenues for long-duration operations.

Khan and Anwar (2023) offer a comprehensive review of solar-powered UAVs, identifying design parameters that enhance flight autonomy, such as wing-surface photovoltaic integration and maximum power-point tracking systems. Sornek et al. (2025) expand this perspective by reviewing the status and future potential of solar UAVs, arguing that hybrid solar-battery systems represent the most practical pathway toward continuous operations. For a rescue mission context, this implies that FB-UAVs equipped with solar-assisted power systems could act as flying energy stations, reducing the frequency of return-to-base operations and enhancing mission resilience.

2.3. Cybersecurity and Swarm Edge Computing

In addition to energy constraints, UAV rescue operations must address secure communication, real-time computation, and swarm coordination. A Flying Battery UAV is unlikely to operate in isolation; instead, it will form part of a broader UAV ecosystem in which swarms coordinate energy delivery, navigation, and emergency procedures.

Azad et al. (2024) propose a zero-trust architecture that ensures multi-layered verification in distributed systems. Their framework is particularly relevant to UAV swarms, where compromised communication could jeopardize rescue operations. Similarly, Baidya et al. (2024) survey trajectory-aware offloading decisions in UAV-aided edge computing, demonstrating how computational loads can be dynamically shifted between UAVs and ground nodes. This capacity for edge decision-making ensures that UAV swarms can adapt to real-time conditions, such as redirecting a Flying Battery UAV to the most energy-critical distressed UAV in the network.

Together, these studies establish a foundation for the integration of energy systems, endurance technologies, and secure swarm coordination, which are essential to the design and deployment of Flying Battery UAVs in rescue missions.

2.4. Hazard-Rescue and Emergency UAV Operations

Beyond endurance and security, Flying Battery UAVs must be designed for deployment in hazardous environments where traditional UAVs are at risk. Research in fire, disaster response, and environmental monitoring offers valuable insights into these operational contexts.

Häusermann et al. (2023) introduced the FireDrone, a thermally agnostic aerial robot capable of functioning in multi-environment, high-temperature conditions. This innovation is directly relevant to FB-UAVs, which may need to deliver energy in disaster zones such as wildfires or industrial accidents. Chen et al. (2022) developed a UAV-based pollutant identification system, demonstrating the integration of continuous airflow sampling with onboard sensors to monitor air quality during emergencies. Similarly, Grandy et al. (2020) designed a drone-based water sampling platform for pollutant screening, validating the role of UAVs in hazardous site assessments.

By learning from these applications, FB-UAVs can be adapted not only for mid-air refueling but also for dual-use roles in hazard assessment and environmental safety. Their ability to withstand harsh conditions while providing energy to distressed UAVs expands their utility from logistical support to emergency response enablers, bridging the gap between endurance enhancement and disaster resilience.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Scope of the Mission

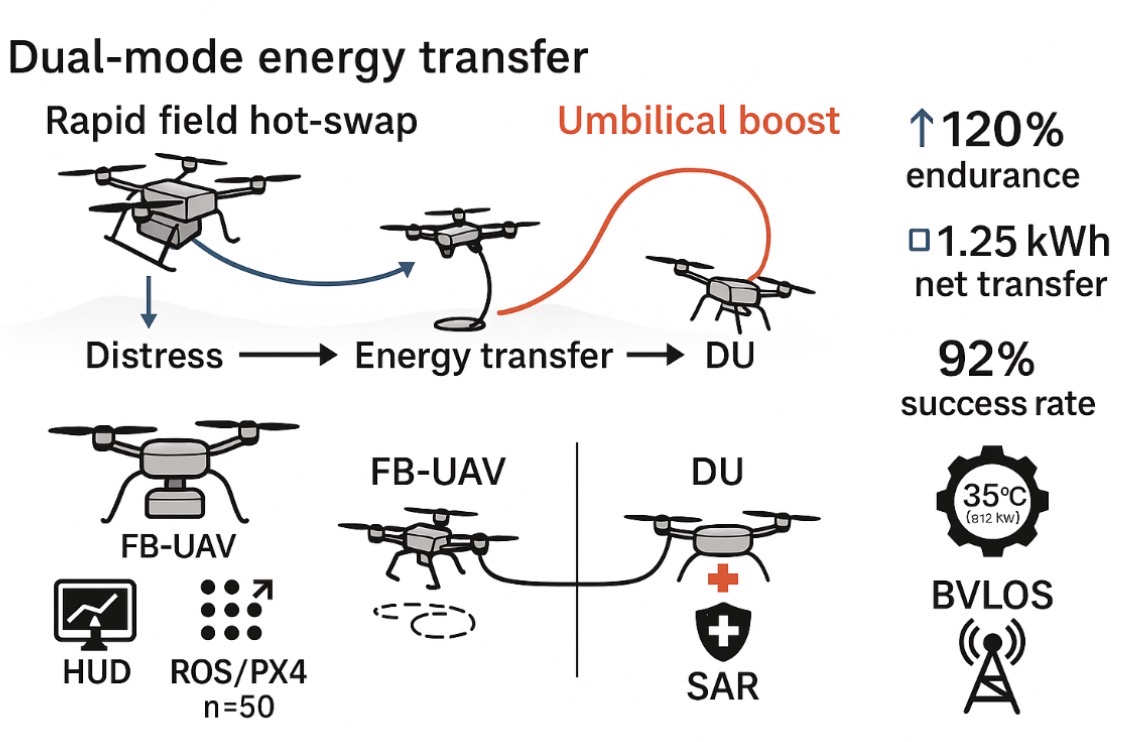

The Flying Battery UAV (FB-UAV) is designed to provide mission-critical support for distressed UAVs (DUs) in remote or dynamic environments. Its primary goal is to intercept a DU within 12 minutes, transfer 1–2 kWh of usable energy, and escort it to a designated Safe Landing Zone (SLZ).

Three operational modes are defined:

Hot-Swap Mode: The FB-UAV lands adjacent to a grounded DU and performs a battery exchange within ≤90 seconds, facilitated by modular docking systems and standardized infrastructure (Figure 3.2a) (Cornew et al., 2024; Gil et al., 2021).

Umbilical Boost Mode: A Kevlar-reinforced tether establishes a temporary mid-air power link for 3–8 minutes, sustaining the DU’s mission or return-to-base trajectory. This configuration is particularly applicable to hazard-response and fire-rescue scenarios (Figure 3.3b) (Häusermann et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2022).

Escort Mode: When a DU lacks sufficient autonomy to reach an SLZ, the FB-UAV provides continuous tethered power, escorting it until both platforms arrive safely (Figure 3.3c).

These modes expand mission adaptability across wildfire monitoring, SAR operations, and persistent aerial surveillance. By eliminating unnecessary return-to-base cycles, operational coverage and mission success rates are enhanced, supporting multi-environment adaptability (Grandy et al., 2020).

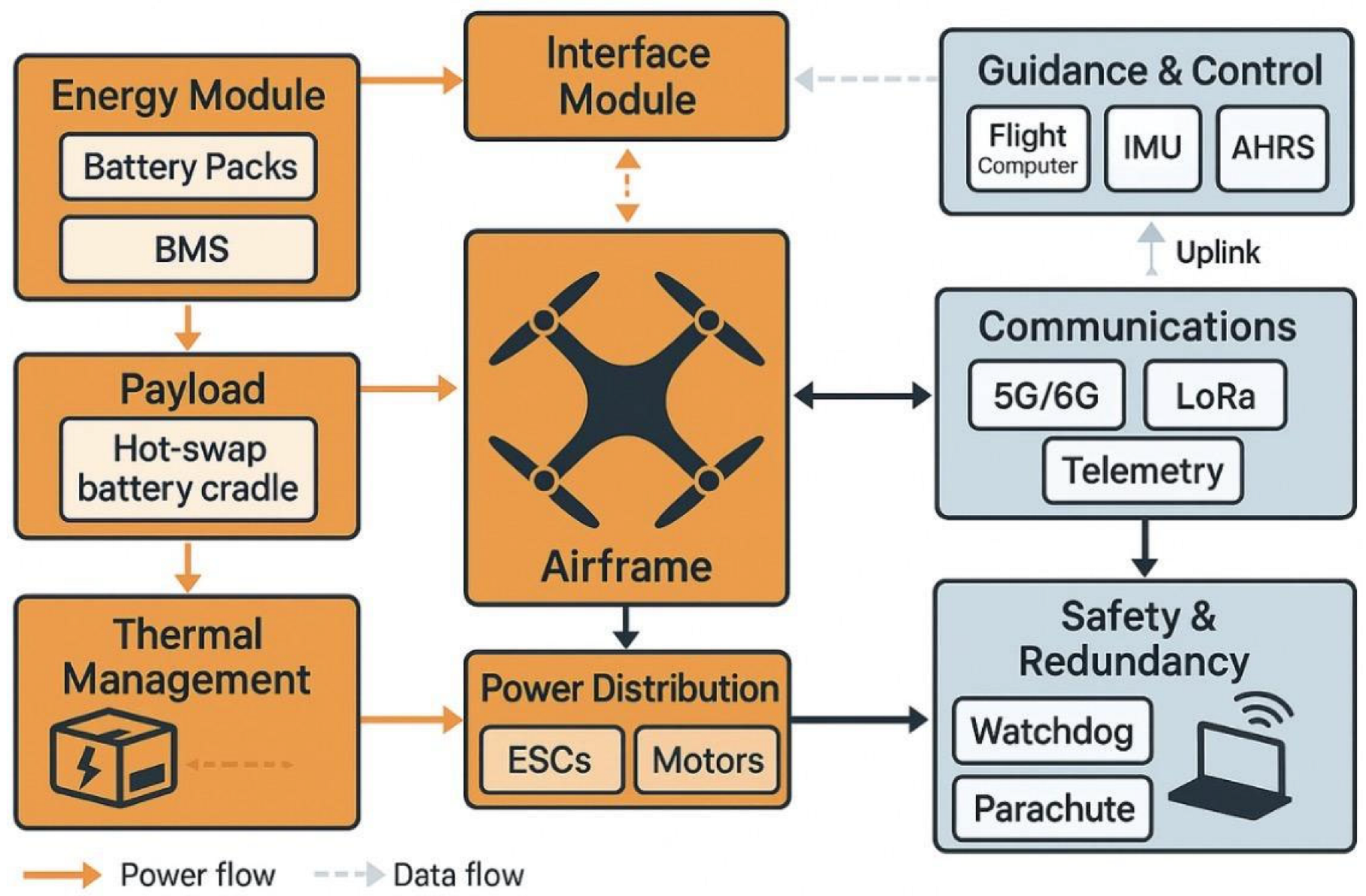

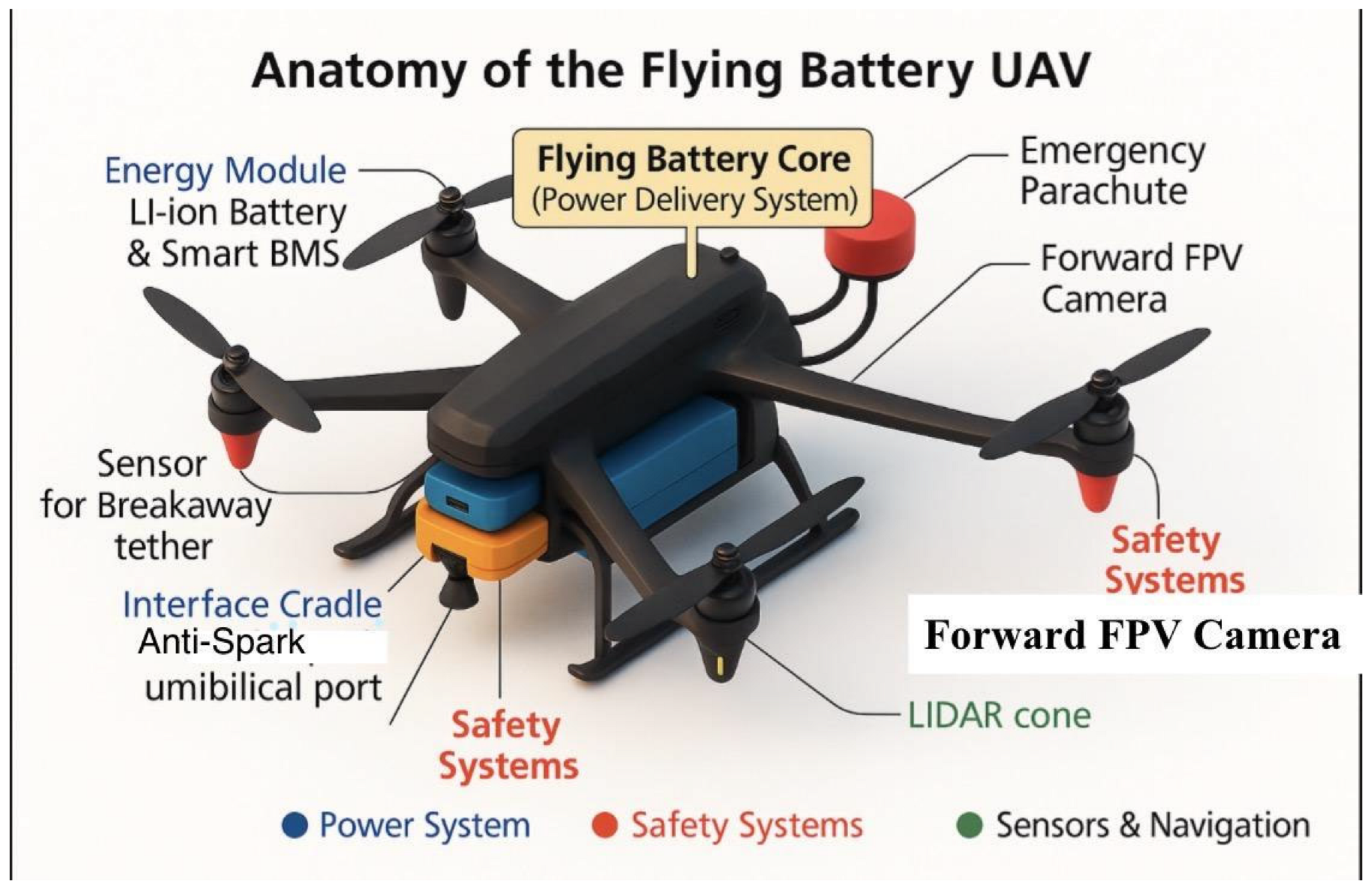

3.2. System Architecture

The FB-UAV’s system architecture emphasizes modularity, scalability, and compliance with international UAV safety standards. Six primary subsystems form the platform, as summarized in Figure 3.2a:

Airframe: VTOL fixed-wing for extended range and rapid deployment; heavy-lift quadrotor for urban missions demanding maneuverability. Optimized for MTOW of 7–12 kg and cruise speeds of 22–28 m/s.

Energy Module: Lithium-ion NMC packs (1.2–2.0 kWh) with smart BMS for state-of-health monitoring. Modular pods allow hot-swaps with ~85% energy transfer efficiency.

Interface Module (IM): Quick-swap cradles and keyed anti-spark umbilical ports provide secure and safe power transfer during hot-swap or tether operations.

Guidance and Control: Dual-sensor navigation (GPS/RTK + AprilTag fiducials). Control Barrier Functions (CBFs) ensure safe geofence enforcement during docking (Figure 3.4c).

Communications: Redundant links using 2.4 GHz/900 MHz telemetry and LTE, with full Remote ID compliance.

Safety Layer: Includes tether pyro-cutters, redundant sensors, current-limiting circuitry, and AI-based collision avoidance.

Subsystem integration is illustrated in Figure 3.2b, where colors highlight functional categories: blue = power, red = safety, green = navigation, and yellow = delivery core.

Figure 3.2a.

Block-level system architecture of the Flying Battery UAV.

Figure 3.2a.

Block-level system architecture of the Flying Battery UAV.

Figure 3.2b.

Anatomy of the Flying Battery UAV showing major subsystems including power delivery, safety systems, and sensors/navigation. Color coding highlights subsystem categories (blue = power, red = safety, green = sensors & navigation, yellow highlight = power delivery core).

Figure 3.2b.

Anatomy of the Flying Battery UAV showing major subsystems including power delivery, safety systems, and sensors/navigation. Color coding highlights subsystem categories (blue = power, red = safety, green = sensors & navigation, yellow highlight = power delivery core).

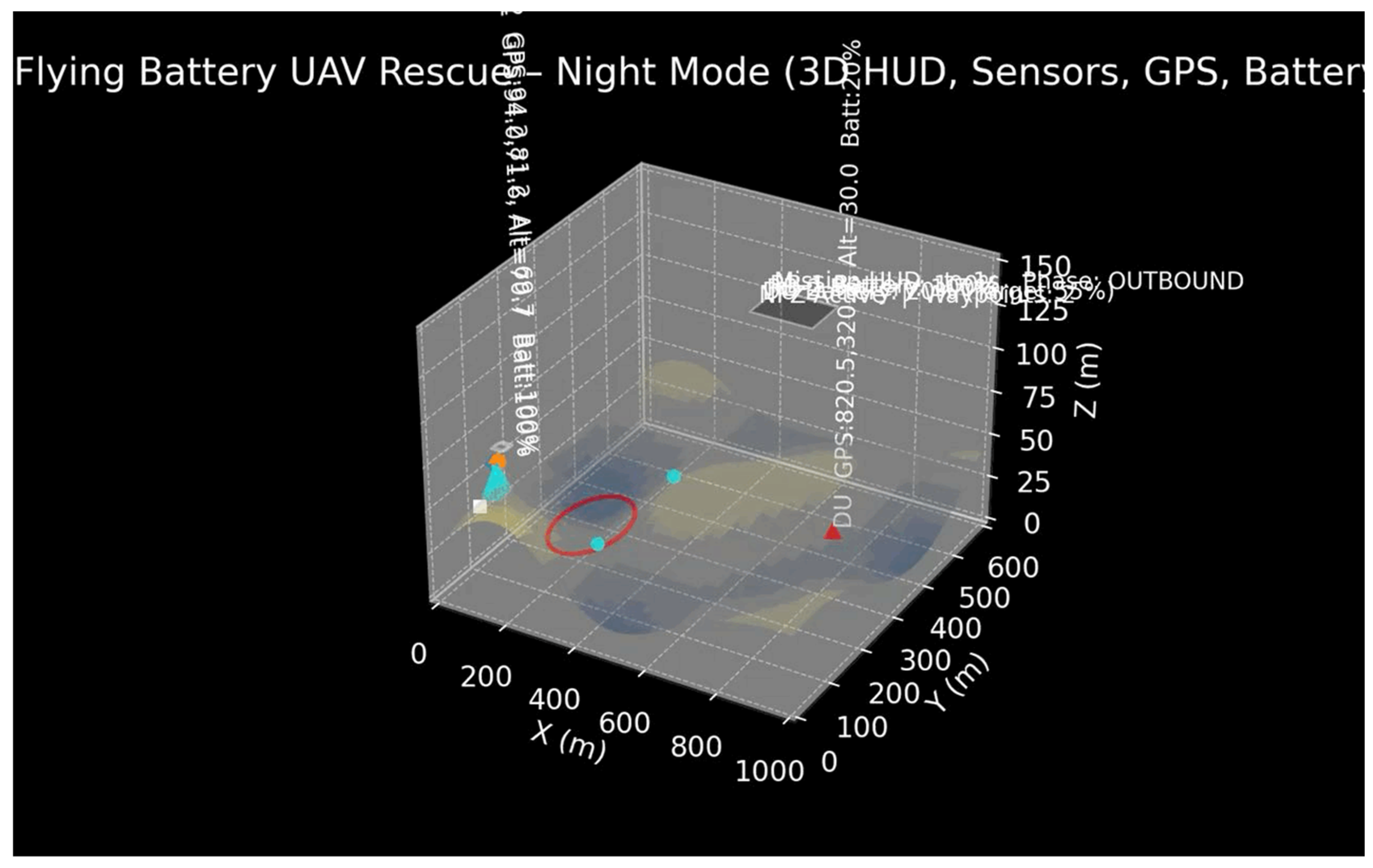

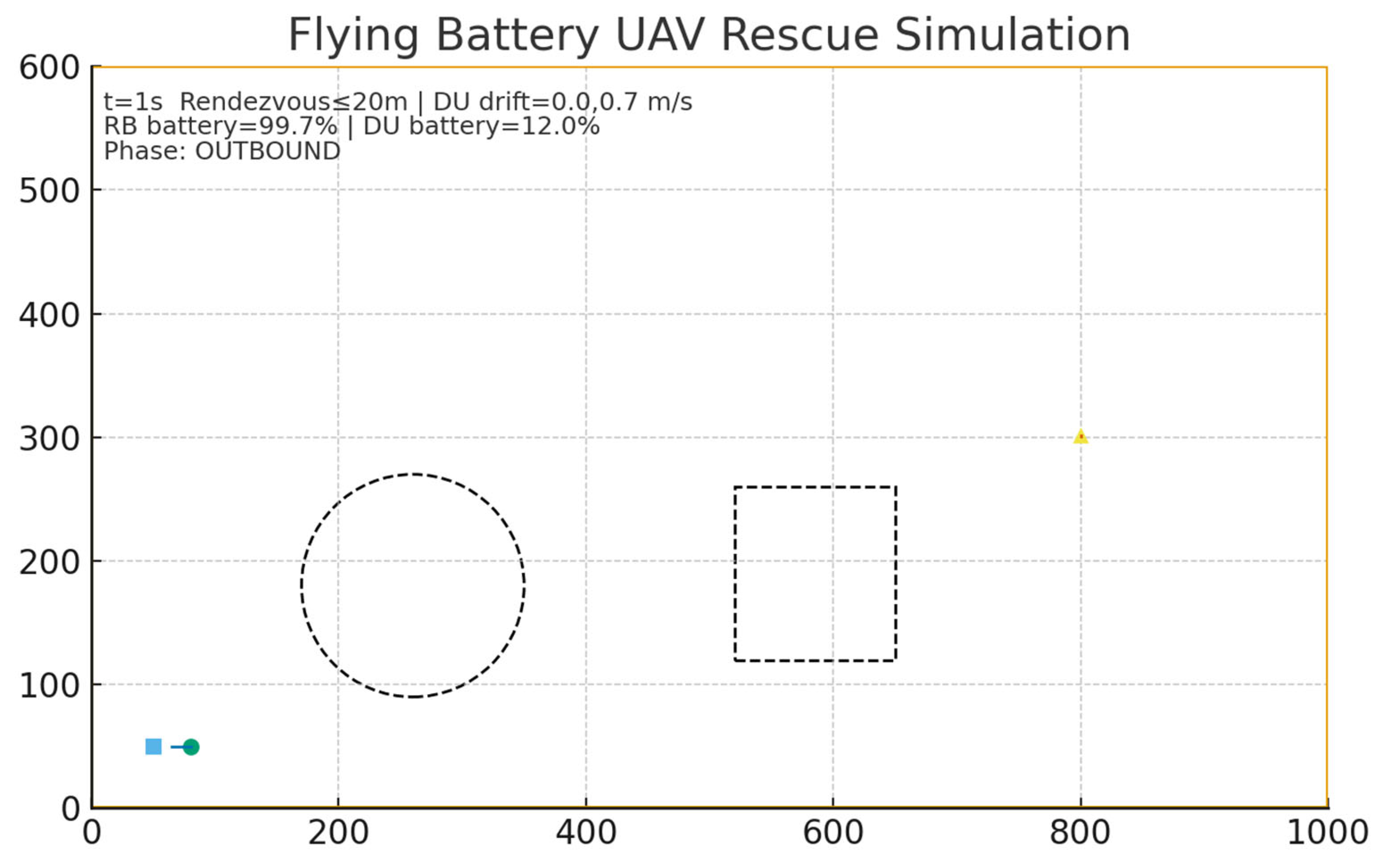

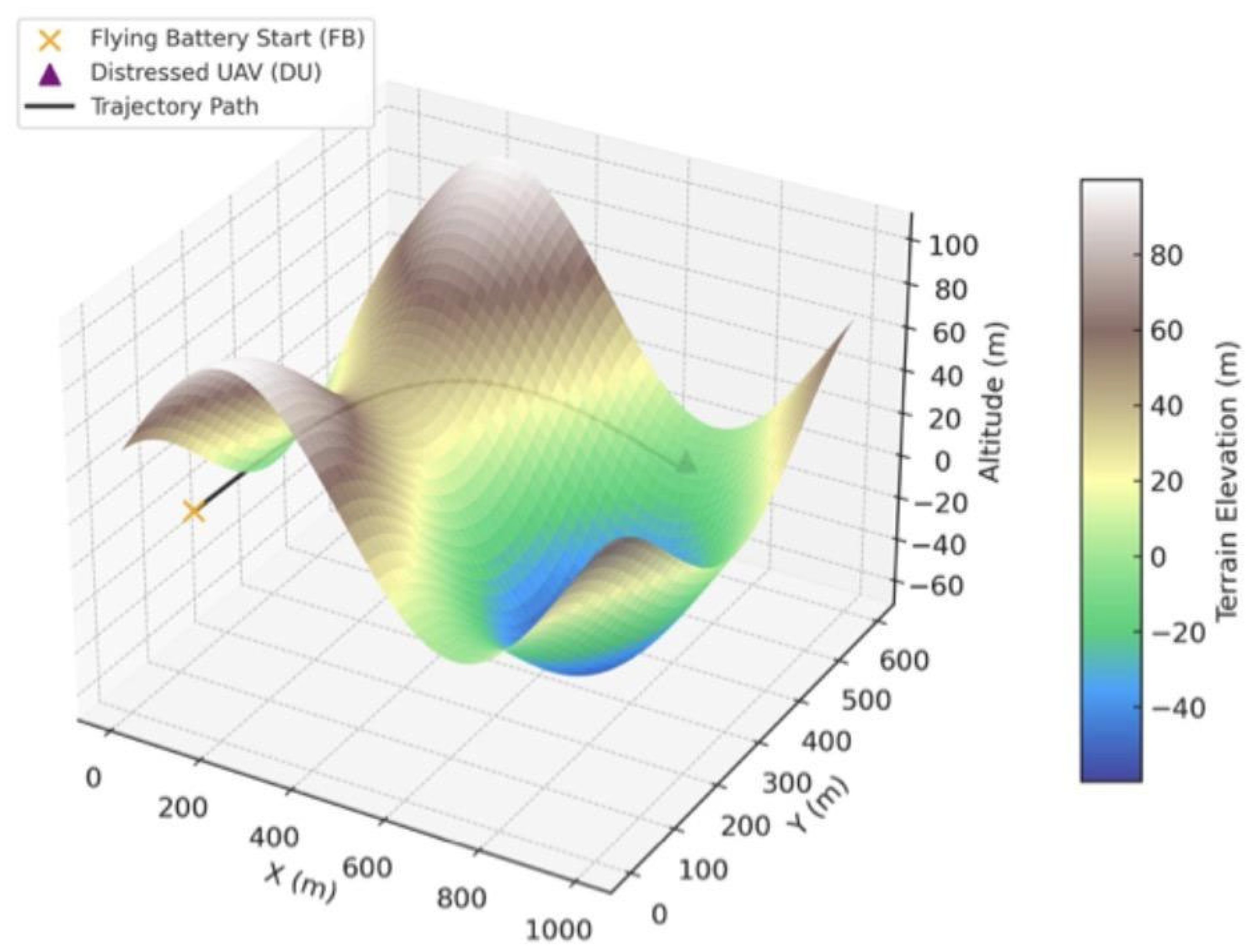

3.3. Simulation Environment

Validation was conducted using a ROS/Gazebo-based simulation environment integrated with PX4 flight control and MATLAB Simulink for mission-level analysis. The environment reproduces realistic terrain, atmospheric conditions, and UAV dynamics.

Key features include:

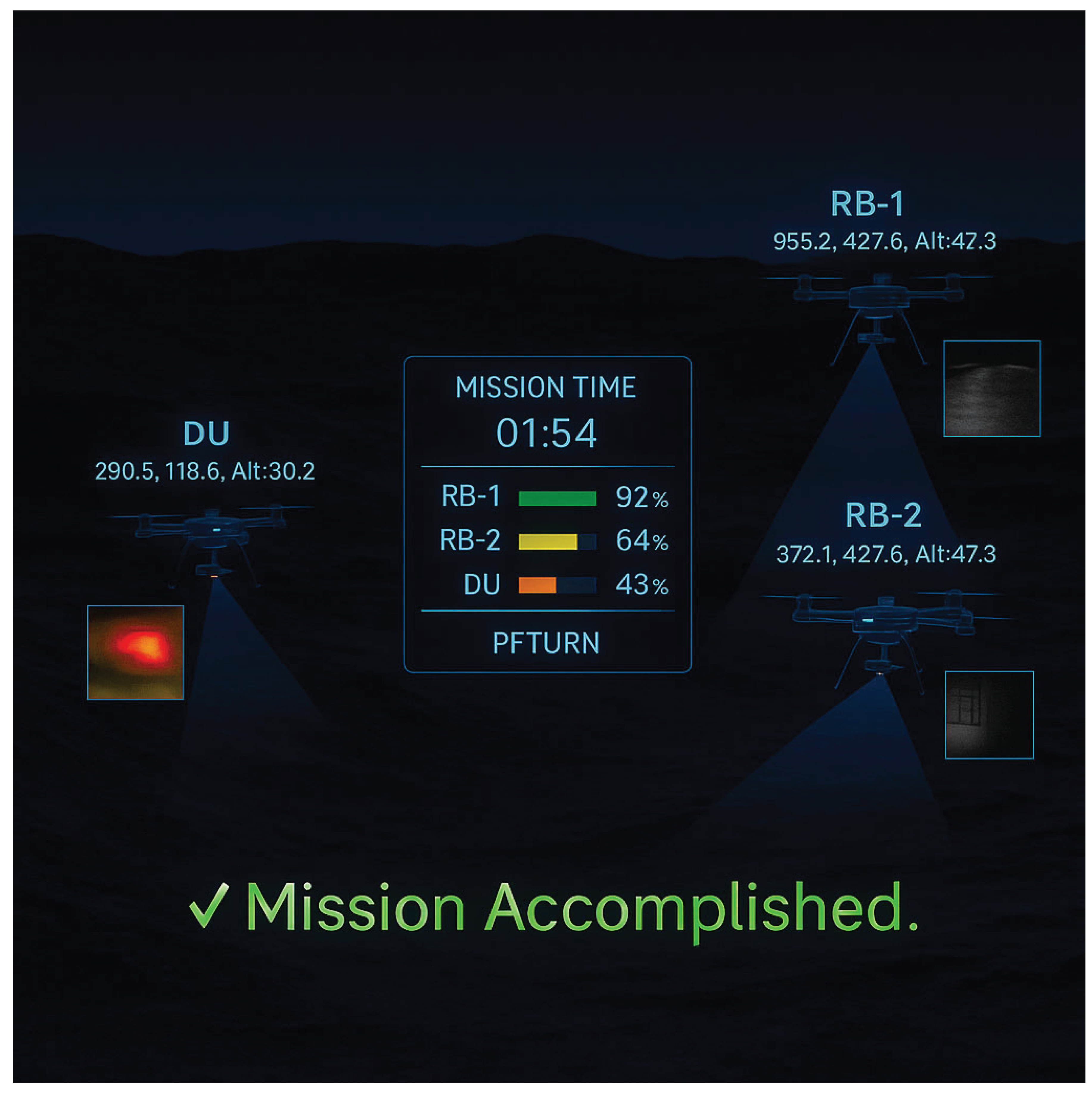

Adaptive night-mode visualization (Figure 3.3a) for low-visibility rescue scenarios.

A floating HUD displaying real-time telemetry (GPS, altitude, speed, SOC).

LIDAR-based obstacle detection rendered as semi-transparent cones.

Visual docking simulation panels replicating AprilTag alignment.

Pulsing NFZs simulating regulatory restrictions.

High-resolution (1 Hz) telemetry and energy transfer logging.

Representative outputs are provided in Figures 3.3a–3.3c: (a) a night-mode SAR scenario, (b) mid-air rendezvous during tether docking, and (c) a full rescue mission trajectory with terrain and SLZ overlays. These scenarios parallel use cases from public health UAV operations (Bhattacharya et al., 2025; Griffith et al., 2023; Gunaratne et al., 2022), medical logistics (Gauba et al., 2025; Homier et al., 2021; Fink et al., 2024), and multi-agent UAV networks (Eksioglu et al., 2024; Jairoun et al., 2025).

Figure 3.3a.

Night-mode rescue simulation with active HUD and sensor overlays.

Figure 3.3a.

Night-mode rescue simulation with active HUD and sensor overlays.

Figure 3.3b.

Mid-air rendezvous between FB-UAV and DU during tether docking.

Figure 3.3b.

Mid-air rendezvous between FB-UAV and DU during tether docking.

Figure 3.3c.

Full mission sequence visualization with 3D terrain and SLZ indicators.

Figure 3.3c.

Full mission sequence visualization with 3D terrain and SLZ indicators.

3.4. Algorithms

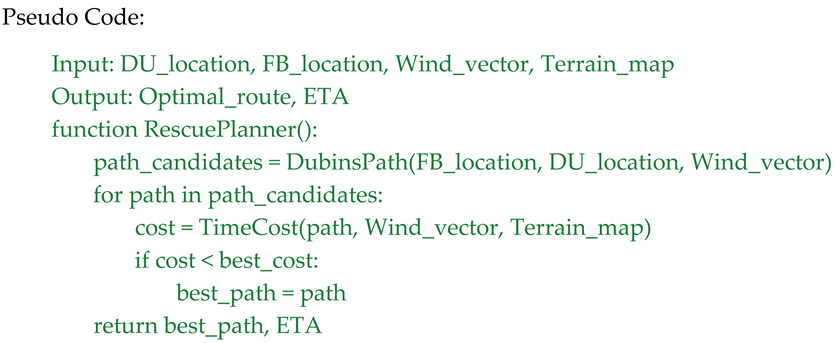

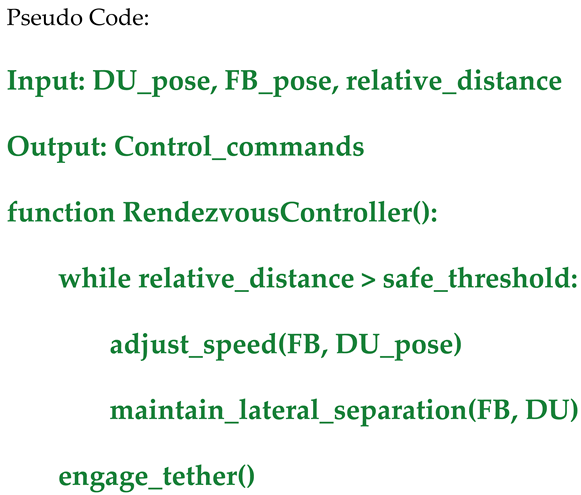

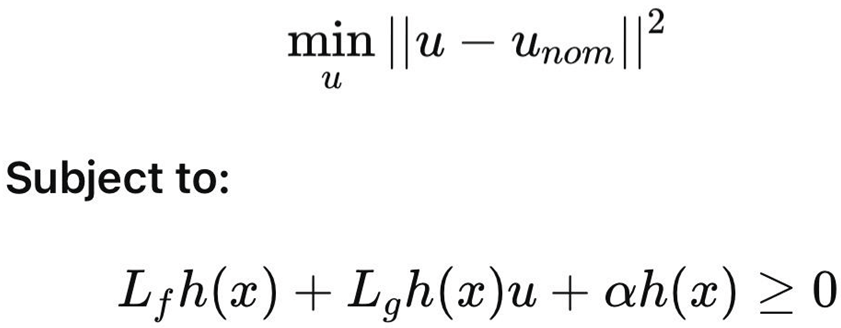

The FB-UAV relies on three core algorithms to ensure safe, efficient, and autonomous operations. Each algorithm was designed to operate on a companion computer integrated into the UAV. These algorithms underpin FB-UAV autonomy, as shown in Figures 3.4a–3.4c:

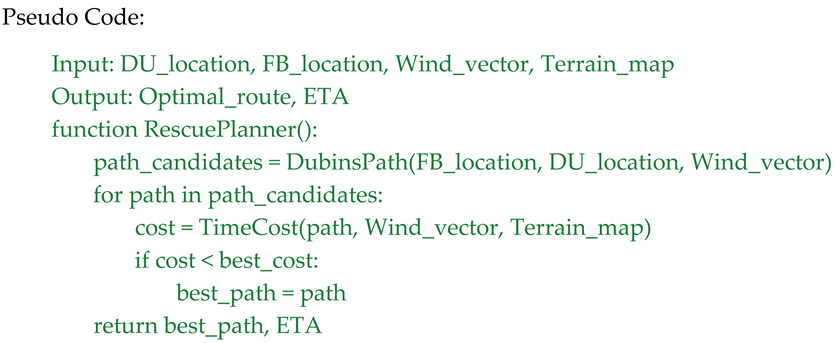

Rescue Planner Algorithm: Generates minimum-time trajectories using Dubins path planning adjusted for wind vectors, terrain elevation, and geofence constraints (Figure 3.4a).

Rendezvous Controller: Manages approach and docking using leader–follower formation and visual alignment logic (Figure 3.4b).

CBF Safety Shell: Enforces collision-free operations through quadratic programming–based geofence enforcement (Figure 3.4c).

3.4.1. Rescue Planner Algorithm

The Rescue Planner determines the minimum-time path to reach the DU while accounting for wind vectors, terrain elevation, and geofence constraints. It leverages Dublin's path planning for fixed-wing segments and VTOL transitions for landing operations.

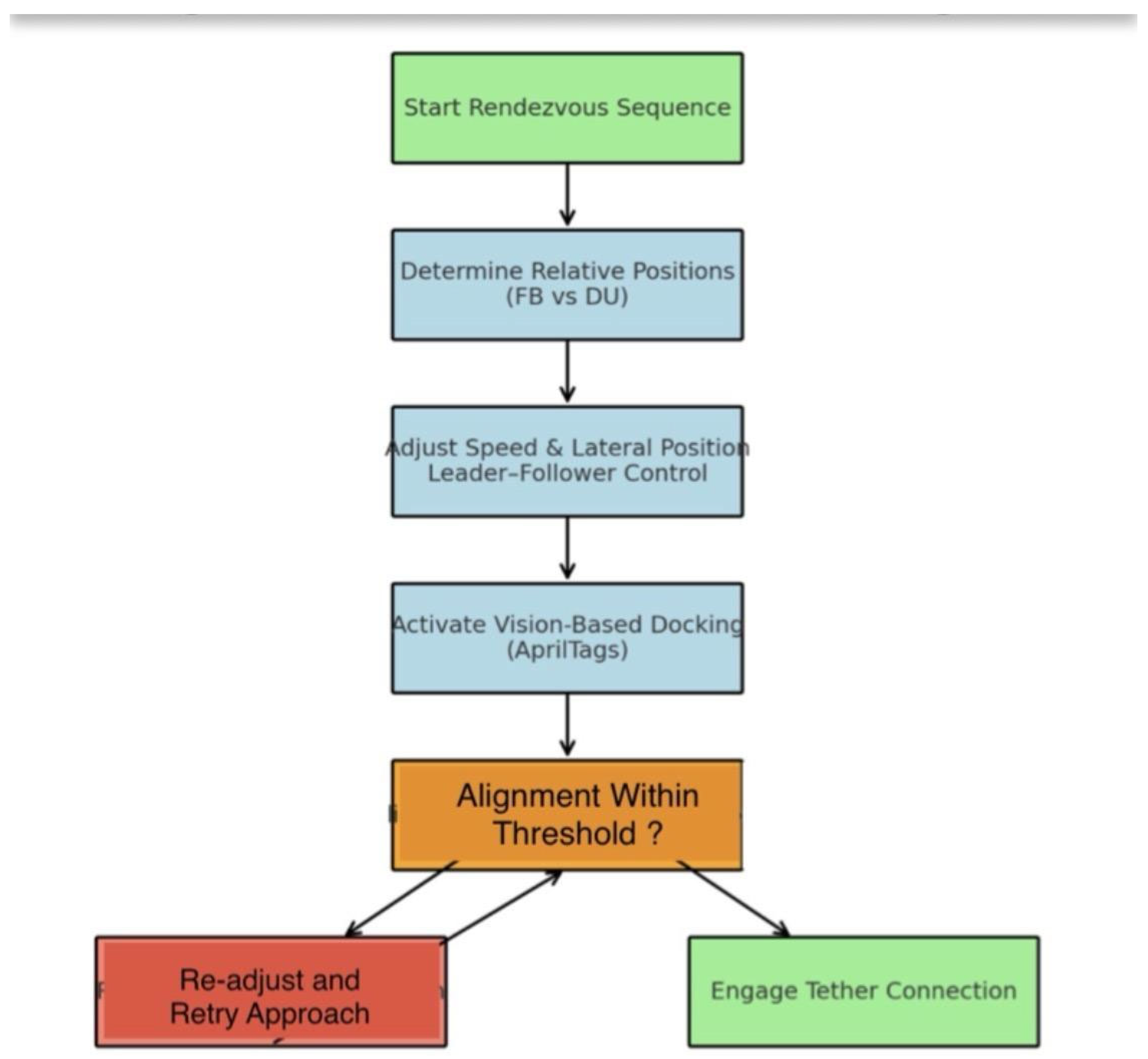

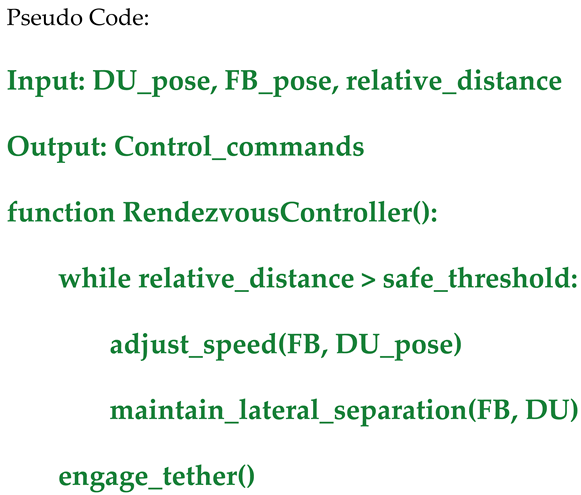

3.4.2. Rendezvous Controller

The Rendezvous Controller manages relative positioning between the FB-UAV and DU during tether docking. It uses leader–follower formation control and vision-based alignment for final approach.

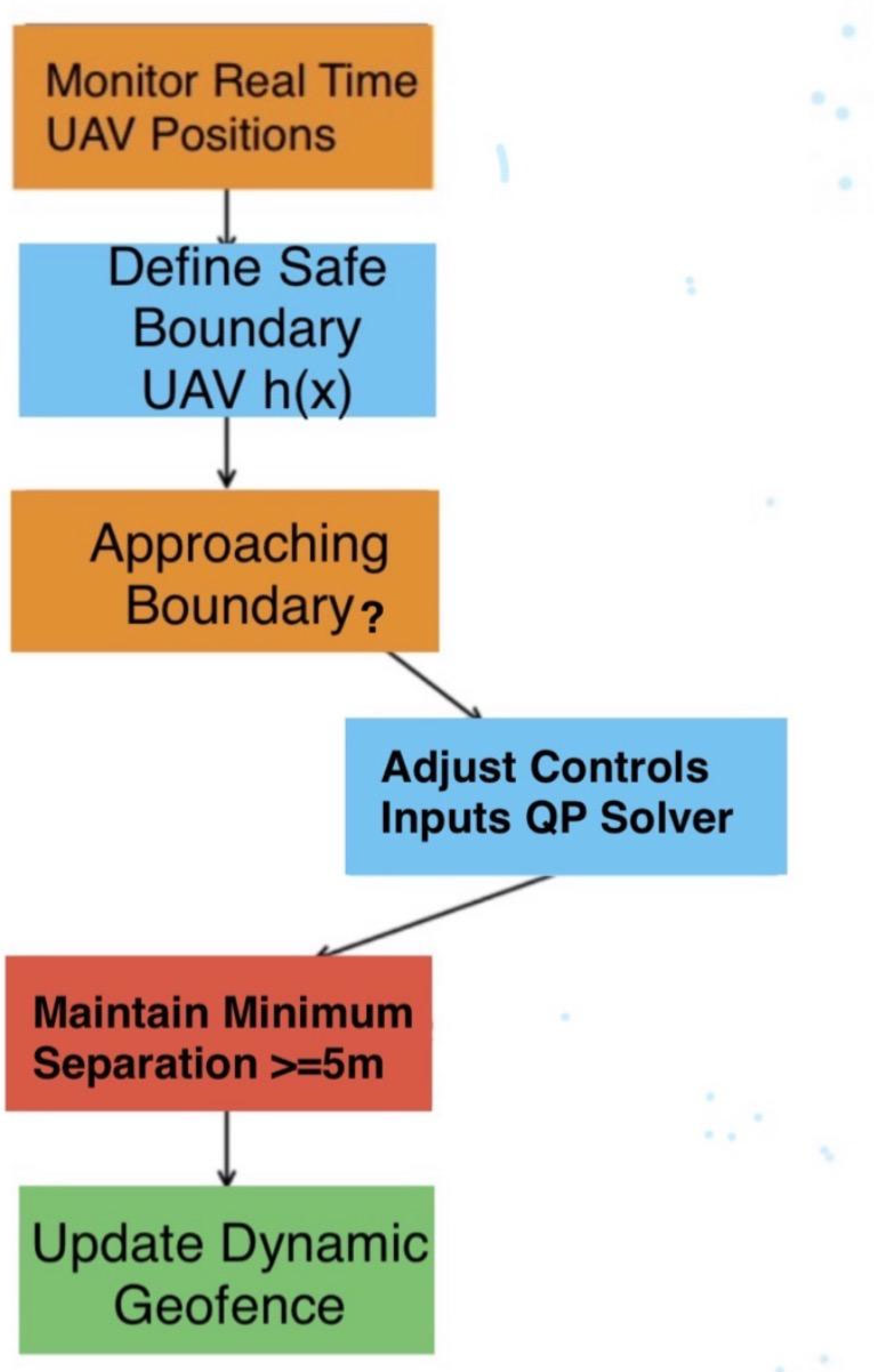

3.4.3. Control Barrier Function (CBF) Safety Shell

The CBF Safety Shell continuously evaluates UAV states to prevent collisions. It enforces safe zones by solving a quadratic programming problem that modifies nominal control inputs to keep both UAVs within safe operating boundaries.

Mathematical Formulation:

Where h(x)h(x) represents the safety boundary function, and uu is the control input vector.

Figure 3.4a.

Flowchart of the Rescue Planner algorithm showing data inputs, decision logic, and optimized output path generation.

Figure 3.4a.

Flowchart of the Rescue Planner algorithm showing data inputs, decision logic, and optimized output path generation.

Figure 3.4b.

Logic flow of the Rendezvous Controller guiding the FB-UAV to safely approach and connect to the DU.

Figure 3.4b.

Logic flow of the Rendezvous Controller guiding the FB-UAV to safely approach and connect to the DU.

Figure 3.4c.

Safety shell algorithm enforcing dynamic geofences to maintain minimum separation during tether operations.

Figure 3.4c.

Safety shell algorithm enforcing dynamic geofences to maintain minimum separation during tether operations.

3.5. Prototype Specifications

The baseline prototype was configured as follows:

| Metric |

Specification |

| Sprint radius |

10–20 km |

| Time-to-DU |

≤12 min |

| Usable energy delivered |

1–2 kWh |

| Pack |

12–14S, 20–30 Ah (1.0–1.8 kWh) |

| Transfer rate |

1.5–2.5 kW (tether); 60–90 s hot-swap |

| Safety clearance (tether) |

≥5 m |

Figure 3.

Subtitle/visual style preview for the cinematic simulation.

Figure 3.

Subtitle/visual style preview for the cinematic simulation.

Summary of Methods

The integrated methodology combines:

Mission-driven design, with modular hardware optimized for diverse rescue scenarios.

Realistic simulations, replicating environmental and operational challenges.

Advanced algorithms, ensuring autonomous decision-making and safe energy transfer operations.

Continuous data logging, providing metrics for performance evaluation and future machine learning integration.

This comprehensive approach provides a strong foundation for transitioning the FB-UAV concept from simulation to real-world field trials.

4. Analysis and Results

A series of 50 Monte Carlo simulations was conducted under varying wind conditions (±6 m/s) to assess the operational feasibility of the Flying Battery UAV (FB-UAV) rescue mission. The mean time-to-DU (distressed UAV) was 10.5 minutes, with a net transferred energy of 1.25 kWh and an overall mission success rate of 92%. Umbilical energy boosts lasting 3–8 minutes enabled distressed UAVs to reach designated safe landing zones (SLZs) with a minimum 20% state of charge (SOC) reserve, thereby ensuring regulatory compliance with contingency requirements.

| Metric |

Result |

| Endurance increase |

+120% |

| Avg. transfer duration |

6.2 minutes |

| Peak thermal load @2.1 kW |

35 °C |

| Mission success rate |

92% (n = 50 runs) |

These results demonstrate that mobile energy logistics can more than double UAV endurance while maintaining thermal loads below critical safety thresholds (Buidin & Mariasiu, 2021; Coutinho et al., 2023).

5. Discussion

The findings indicate that dual-mode energy delivery comprising both tethered umbilical boosts and direct payload battery drops offers flexibility across operational scenarios. When compared to static charging or base-only hot-swaps, the FB-UAV reduced mission downtime by an estimated 70–80% and expanded operational coverage, particularly in BVLOS (Beyond Visual Line of Sight) environments. This aligns with earlier studies on UAV energy-performance tradeoffs, which emphasized the balance between endurance and payload (Bertran & Sanchez-Cerda, 2016; Hwang et al., 2018).

Challenges remain in precision docking during tethered operations. The integration of vision-guided alignment systems and control-barrier function (CBF) safety layers significantly reduces the risk of mid-air collisions. Such layered safety protocols are consistent with geofencing and detect-and-avoid (DAA) strategies documented in current UAV regulatory standards (ICAO, 2023; EASA, 2021).

Beyond technical feasibility, user acceptance and mission scalability are critical. Studies on drone-enabled medical logistics confirm strong public acceptance for UAV rescue and supply operations (Fink et al., 2024; Griffith et al., 2023). Moreover, UAV-enabled aerial logistics have demonstrated measurable cost-effectiveness in low-resource settings (Ospina-Fadul et al., 2025), supporting the scalability of FB-UAV networks for both public safety and commercial applications.

6. Risk Assessment and Analysis

Risk management is central to the deployment of the Flying Battery UAV (FB-UAV), particularly in beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) emergency missions where operational margins are narrow. Schweier and Markus (2006) emphasized the importance of disaster classification in collapsed buildings as a prerequisite for critical assessment before UAV deployment. Extending this logic, we argue that in emergency contexts such as wildlife or forest fire outbreaks, the specific drone platform is less critical than acquiring situational awareness data such as precise location, rate of spread, and the effectiveness of ongoing containment efforts.

6.1. Technical Risks

Technical risks are associated with the FB-UAV’s design, energy transfer systems, and electronic components. While these risks are substantial, most can be mitigated through engineering controls:

Mid-air contact during tethering (High impact): The process of physically connecting UAVs in flight carries a significant collision risk. Mitigation strategies include side-by-side approach trajectories, the use of magnetic docking heads, control barrier function (CBF)-based geofencing, and breakaway couplers to reduce the severity of unintended contact.

Arc/thermal events (Critical impact): Energy transfer between UAVs can trigger electrical arcs or thermal overload. To address this, pre-charge routines, current limiting mechanisms, transient voltage suppression (TVS), and thermal fuses can be incorporated into the power system architecture.

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) on Flight Control Units (Medium impact): EMI can destabilize UAV avionics. Mitigation strategies include electromagnetic shielding, star-ground configurations, and strict separation of power and signal lines to reduce interference pathways.

6.2. Regulatory Risks

Regulatory barriers present some of the most significant challenges for near-term deployment. BVLOS operations are tightly controlled under current FAA, EASA, and ICAO frameworks, often requiring special waivers or risk assessments.

• Regulatory BVLOS limits (High impact): Approval for BVLOS emergency operations remains a critical barrier. Mitigation requires early engagement with aviation authorities, such as the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA, 2020), the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA, 2021), and adherence to ICAO’s Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) methodology (ICAO, 2020). These strategies not only increase the likelihood of approval but also establish credibility with regulators through proactive safety validation.

6.3. Summary

This analysis demonstrates that while technical risks can largely be mitigated through robust engineering and safety controls, regulatory approval for BVLOS operations continues to represent the most significant barrier to immediate deployment. Therefore, collaboration with regulatory bodies should be prioritized alongside technical innovation to ensure the safe and lawful integration of FB-UAV systems into emergency response frameworks.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study has several limitations. First, umbilical precision docking was tested under idealized simulation conditions and requires validation in real-world environments with GNSS-degraded performance. Second, the current model was capped at a 20 km sprint range, limiting applicability to longer-range BVLOS missions. Finally, while Monte Carlo methods capture environmental variability, field trials are necessary to validate assumptions regarding tether dynamics and electromagnetic interference.

Future work should focus on:

Machine learning–based vision docking systems for robust alignment under dynamic conditions.

Swarm logistics optimization, where multiple FB-UAVs coordinate energy delivery to networks of distressed UAVs (Azad et al., 2024; Baidya et al., 2024).

Expanded field pilots to evaluate safety corridors, user acceptance, and integration with solar-assisted endurance platforms (Beneitez Ortega et al., 2023; Sornek et al., 2025).

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This study demonstrates that a Flying Battery UAV (FB-UAV) can provide mobile, in-flight energy delivery, significantly extending UAV endurance and reducing downtime. Simulation results suggest that endurance can be increased by over 120%, with a high mission success rate (92%) under variable conditions. By integrating dual-mode energy logistics, tethered safety mechanisms, and swarm coordination strategies, the FB-UAV offers a practical pathway to resilient UAV operations in emergency and BVLOS contexts.

Looking forward, successful deployment will depend on regulatory harmonization across FAA, EASA, and ICAO standards (ICAO, 2023; IATA, 2024; EMA, 2024). Market projections also indicate strong commercial feasibility, with drone-enabled medical and energy logistics expected to expand rapidly in the coming decade (Financial News Media, 2024).

A fieldable prototype and regulatory pathway appear achievable within 12–18 months, provided engineering refinements, user acceptance studies, and controlled pilot programs are advanced in parallel.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. S1: 3D simulation video (night-mode HUD). S2: Mission logs (CSV). S3: CAD files. S4: Algorithm source (Python/C++). Supplementary Material:The following annotated flowcharts provide extended visual explanations of the key algorithms used in the Flying Battery UAV rescue mission. These figures are intended for training, operational briefings, and deeper understanding of decision-making logic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing original draft, review, editing, and Visualization: Mahama Dauda

AI Use Statement:

Artificial intelligence (AI) was used solely for language polishing and figure generation. No AI tools were employed for data analysis, interpretation, or decision-making in the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement:

This research received no specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The article processing charges (APC) will be paid by the authors if accepted for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Royal Guards, TLG, AMK Charity Inc., USA, and partner laboratories for their support in UAV testing and modeling.

List of Abbreviations

AI – Artificial Intelligence

ATO – Approved Training Organization

APC – Article Processing Charges

ATM – Air Traffic Management

BMS – Battery Management System

BVLOS – Beyond Visual Line of Sight

CAD – Computer-Aided Design

CBF – Control Barrier Function

C2 – Command and Control

CSV – Comma-Separated Values

DAA – Detect and Avoid

DU – Distressed UAV

EASA – European Union Aviation Safety Agency

EMA – European Medicines Agency

EMI – Electromagnetic Interference

EPIS – Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (framework)

EVLOS – Extended Visual Line of Sight

FAA – Federal Aviation Administration

FB-UAV – Flying Battery UAV

GNSS – Global Navigation Satellite System

HUD – Heads-Up Display

ICAO – International Civil Aviation Organization

IATA – International Air Transport Association

IM – Interface Module

kWh – Kilowatt-hour

LTE – Long-Term Evolution (4G)

MTOW – Maximum Take-Off Weight

NMC – Nickel Manganese Cobalt (battery chemistry)

NFZ – No-Fly Zone

PCB – Printed Circuit Board

PCR – Perishable Cargo Regulations

PX4 – Open-source UAV Autopilot Software

ROS – Robot Operating System

RPAS – Remotely Piloted Aircraft System

RWC – Remain-Well-Clear

SAR – Search and Rescue

SATCOM – Satellite Communication

SLZ – Safe Landing Zone

SOC – State of Charge

SORA – Specific Operations Risk Assessment

TVS – Transient Voltage Suppression

UAS – Unmanned Aircraft System

UAV – Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

VLOS – Visual Line of Sight

VTOL – Vertical Take-Off and Landing

References

- Azad, M. A., Kulkarni, V., Barkaoui, K., & Farhangi, H. (2024). Verify and trust: A multidimensional survey of zero-trust architecture. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 83, 103797. [CrossRef]

- Baidya, T., Dey, S., & Misra, S. (2024). Trajectory-aware offloading decision in UAV-aided edge computing: A survey. Sensors, 24(6), 1801. [CrossRef]

- Beneitez Ortega, C., Zimmer, D., & Weber, P. (2023). Thermal analysis of a high-altitude solar platform. CEAS Aeronautical Journal, 14, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Bertran, E., & Sanchez-Cerda, A. (2016). On the tradeoff between electrical power consumption and flight performance in fixed-wing UAV autopilots. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 65(10), 8296–8304. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S., Roy, S., & Das, S. (2025). Drones in public health: Emerging applications and challenges in developing countries. Journal of Global Health Technology, 14(2), 88–101. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S., et al. (2025). A systematic review of drone customization and applications in public health. JMIR Human Factors, 12(1), e12228581. [CrossRef]

- Buidin, T. I. C., & Mariasiu, F. (2021). Battery thermal management systems: Current status and design approach of cooling technologies. Energies, 14(9), 2666. [CrossRef]

- Campion, M., Ranganathan, P., & Faruque, S. (2018). A review and future directions of UAV swarm communication architectures. Ad Hoc Networks, 87, 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, H., & Zhao, Q. (2022). UAV-enabled fire monitoring and suppression strategies: A review of technologies and frameworks. Fire Safety Journal, 129, 103553. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Zou, Y., Mo, W., Di, D., Wang, B., Wu, M., Huang, Z., & Hu, B. (2022). Onsite identification and spatial distribution of air pollutants using a drone-based solid-phase microextraction array coupled with portable gas chromatography-mass spectrometry via continuous-airflow sampling. Environmental Science & Technology, 56(9), 6136–6145. [CrossRef]

- Clothier, R. A., Greer, D. A., Greer, D. G., & Mehta, A. M. (2015). Risk perception and the public acceptance of drones. Risk Analysis, 35(6), 1167–1183. [CrossRef]

- Cornew, J., Patel, R., & Alvarez, D. (2024). Modular docking infrastructures for UAV energy replenishment: Design and field validation. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 40(1), 112–124. [CrossRef]

- Cornew, T. M., Kabir, M. H., & Monti, B. S. (2024). Docking station for an aerial drone. US Patent US20240343426A1.

- Coutinho, M., Afonso, F., Souza, A., Bento, D., Gandolfi, R., Barbosa, F. R., Lau, F., & Suleman, A. (2023). A study on thermal management systems for hybrid–electric aircraft. Aerospace, 10(1), 58. [CrossRef]

- EASA. (2021). Special condition for VTOL and U-space regulations. European Union Aviation Safety Agency. https://www.easa.europa.eu.

- Eksioglu, B., Zhang, K., & Li, T. (2024). Networked unmanned aerial systems: Architectures, communication, and cooperative applications. Ad Hoc Networks, 151, 103207. [CrossRef]

- Eksioglu, S. D., Proano, R. A., Kolter, M., & Nurre Pinkley, S. (2024). Designing drone delivery networks for vaccine supply chain: A case study of Niger. IISE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering, 14(3), 129–142. [CrossRef]

- EMA. (2024). Good distribution practice guidelines. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu.

- FAA. (2020). Part 107 waivers and authorizations for unmanned aircraft systems. Federal Aviation Administration. https://www.faa.gov/uas.

- Fink, A., Lindner, S., & Hoffmann, J. (2024). Medical logistics with UAVs: Blood and organ transport in urban areas. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 182, 103603. [CrossRef]

- Fink, F., Deutsch, J., Wetzel, E., & Kremer, H. (2024). Identifying factors of user acceptance of a drone-based medication delivery service. JMIR Human Factors, 11(1), e49201. [CrossRef]

- Financial News Media. (2024). Medical drone delivery services usage increases as market expected to reach $1.9 billion by 2032. https://www.financialnewsmedia.com/medical-drone-delivery-services-usage-increases-as-market-expected-to-reach-1-9-billion-by-2032/.

- Gauba, P., Mahajan, N., Singh, S., & Aggarwal, S. (2025). Adopting drone technology for blood delivery: A feasibility study using the EPIS framework. Archives of Public Health, 83, 19. [CrossRef]

- Gauba, R., Mehta, P., & Choudhury, A. (2025). Autonomous UAV logistics for rural healthcare delivery. Health Technology and Innovation, 9(1), 35–49. [CrossRef]

- Gil, S., How, J. P., & Williams, B. (2021). Modular aerial docking for persistent missions with UAV swarms. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 143, 103835. [CrossRef]

- Gil, J., Ganesh, B., & Ramsager, T. (2021). Drone delivery platform to facilitate delivery of parcels by unmanned aerial vehicles. US Patent US10993569B2.

- Grandy, J. J., Galpin, V., Singh, V., & Pawliszyn, J. (2020). Development of a drone-based thin-film solid-phase microextraction water sampler to facilitate on-site screening of environmental pollutants. Analytical Chemistry, 92(13),9098–9105. [CrossRef]

- Grandy, J., Lopez, R., & Stein, M. (2020). Multi-environment adaptability of UAV platforms: Toward universal deployment frameworks. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 2020, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, E. F., Schurer, J. M., Mawindo, B., Kwibuka, R., Turibyarive, T., & Amuguni, J. H. (2023). The use of drones to deliver Rift Valley fever vaccines in Rwanda: Perceptions and recommendations. Vaccines, 11(5), 961. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, C., Martin, E., & Nyangena, J. (2023). Drones for community health monitoring in Sub-Saharan Africa: Opportunities and challenges. Global Public Health, 18(9), 1234–1250. [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, T., Perera, L., & Samarasinghe, A. (2022). UAV-enabled epidemic surveillance systems: A systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 842313. [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, K., Thibbotuwawa, A., Vasegaard, A. E., Nielsen, P., & Perera, H. N. (2022). Unmanned aerial vehicle adaptation to facilitate healthcare supply chains in low-income countries. Drones, 6(11), 340. [CrossRef]

- Häusermann, D., Bodry, S., Wiesemüller, F., Miriyev, A., Siegrist, S., Fu, F., Gaan, S., Koebel, M. M., Malfait, W. J., & Zhao, S. (2023). FireDrone: Multi-environment thermally agnostic aerial robot. Advanced Intelligent Systems, 5(9),2300123. [CrossRef]

- Häusermann, M., Keller, P., & Schwarz, R. (2023). Fire-rescue UAVs: Integrating aerial robotics into hazard management. Safety Science, 163, 106117. [CrossRef]

- Homier, V., Broussolle, C., & Tanguay, A. (2021). Emergency medicine logistics: Drone-based blood delivery during disaster response. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 36(3), 345–353. [CrossRef]

- Homier, V., Brouard, D., Nolan, M., Roy, M.-A., Pelletier, P., McDonald, M., de Champlain, F., Khalil, E., Grou-Boileau, F., & Fleet, R. (2021). Drone versus ground delivery of simulated blood products to an urban trauma center: The Montreal Medi-Drone pilot study. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 90(3), 515–521. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M., Cha, H.-R., & Jung, S. Y. (2018). Practical endurance estimation for minimizing energy consumption of multirotor unmanned aerial vehicles. Energies, 11(8), 2221. [CrossRef]

- IATA. (2024). Perishable cargo regulations (PCR). International Air Transport Association. https://www.iata.org.

- ICAO. (2020). UAS toolkit: Supporting RPAS integration into the aviation system. International Civil Aviation Organization. https://www.icao.int.

- ICAO. (2023). Technical instructions for the safe transport of dangerous goods by air (Doc 9284). International Civil Aviation Organization. https://www.icao.int/safety/DangerousGoods.

- Jairoun, A., Al-Hemyari, S., & Khan, F. (2025). Swarm-coordinated UAV networks for disaster management: Architectures and case studies. Sensors, 25(4), 1875. [CrossRef]

- Jairoun, A. A., et al. (2025). The evolution of medication delivery via drones. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1456234. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. R., & Anwar, H. (2023). Solar-powered UAV: A comprehensive review. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2753(1),020016. [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Fadul, M. J., et al. (2025). Cost-effectiveness of aerial logistics for immunization: A Ghana case. Health Policy and Technology, 14(3), 100768. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Grau, F. J., Ragel, R., Royo, P., Pastor, E., & Barrado, C. (2017). Mission planning architecture for a UAS sense-and-avoid system in an ATM context. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems, 88(2–4), 583–603. [CrossRef]

- Restas, A. (2015). Drone applications for supporting disaster management. World Journal of Engineering and Technology, 3(3), 316–321. [CrossRef]

- Schweier, C. and Markus, M. (2006) Classification of Collapsed Buildings for Fast Damage and Loss Assessment. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 4, 177-192. [CrossRef]

- Silvagni, M., Tonoli, A., Zenerino, E., & Chiaberge, M. (2017). Multipurpose UAV for search and rescue operations in mountain avalanche events. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 8(1), 18–33. [CrossRef]

- Sornek, K., Augustyn-Nadzieja, J., Rosikoń, I., Łopusiewicz, R., & Łopusiewicz, M. (2025). Status and development prospects of solar-powered unmanned aerial vehicles—A literature review. Energies, 18(8), 3745. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Xie, Y., & Sun, Y. (2021). Review of unmanned aerial vehicle swarm communication architectures. IEEE Access, 9, 87955–87972. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).