1. Introduction

Microsatellite instability (MSI) refers to a state of genomic instability caused by defects in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system, which prevents the correction of errors in the replication of small repetitive DNA sequences (microsatellites) during cell division [

1,

2]. Microsatellite stability(MSS) refers to a state of stable microsatellites. MSI tumors account for approximately 3%-5% of all rectal cancers. Compared with MSS tumors, patients with stage II MSI-high (MSI-H) rectal cancer have a significantly lower recurrence risk and longer overall survival after surgery. Meanwhile, MSI-H/deficient MMR (dMMR) is the strongest biomarker for predicting the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors [

3,

4]. However, the current assessment of MSI status in rectal cancer relies on biopsy, and conventional imaging methods cannot directly evaluate the MSI status of rectal cancer [

5,

6]. The purpose of this study was to investigate the feasibility of preoperatively predicting the MSI status of rectal cancer using T₂mapping technique combined with ADC value.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Data

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 152 cases of pathologically confirmed rectal cancer in our hospital from January 2022 to June 2025.

Inclusion criteria: (1) All cases had complete pathological results, and the MSI status was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (detecting MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) combined with MSI-PCR (detecting 5 microsatellite loci: BAT25, BAT26, D5S346, D2S123, and D17S250); (2) All MRI examinations were completed before any treatment (including biopsy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy); (3) Image quality score ≥ 1 (see Section 1.3 for definition).

Exclusion criteria: (1) Severe artifacts (foreign body or motion artifacts) affecting image measurement (image quality score = 0); (2) Receipt of intestinal anti-inflammatory treatment (e.g., 5-aminosalicylic acid) within 3 months before surgery; (3) Incomplete clinical or follow-up data.

Sample size calculation: Based on the previously reported T2 value difference of 9.06 ± 7.00 between the MSI and MSS groups in a prior study [

13], and using parameters set at α = 0.05 and power = 0.90, the minimum sample size for the MSI group was calculated as 35 using G*Power 3.1. To ensure statistical robustness, this study included 40 MSI patients.

2.2. Equipment and Methods

A 3.0T superconducting MRI scanner (Philips Elition, Philips Healthcare, the Netherlands, with an 18-channel phased-array body coil; and Siemens Prisma, Siemens Healthineers, Germany, with a 32-channel phased-array body coil) was used. Patients were instructed to empty their rectums before the examination and were placed in the supine position during scanning.

Scanning parameters: (1) Oblique axial high-resolution T2-weighted imaging (T2WI): Perpendicular to the long axis of the lesion; repetition time (TR) = 2500 ± 100 ms, echo time (TE) = 100 ± 5 ms, field of view (FOV) = 20-22 cm × 20-22 cm, matrix = 320 × 240, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice gap = 0.4 mm; fat suppression method: chemical shift suppression. (2) Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI): TR = 4360 ± 200 ms, TE = 77 ± 3 ms, FOV = 30 cm × 22 cm, matrix = 168 × 168, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice gap = 0.4 mm, b-values = 50 and 800 s/mm², diffusion directions = 15. (3) T₂ mapping: Using the mDIXON QUANT sequence; TR = 1700 ± 50 ms, TE = 13, 26, 39, 52, 65, 78 ms, flip angle (FA) = 90°, echo train length (ETL) = 22, FOV = 38 cm × 38 cm, number of excitations (NEX) = 1, slice thickness = 3.5 mm, slice gap = 2.5 mm.

To evaluate the consistency of measurement results between different MRI scanners (Philips Elition and Siemens Prisma), we randomly selected 20 patients. The same radiologist measured the T2 values and ADC values respectively on the images generated by the two different scanners, and Bland-Altman analysis was used to perform consistency testing.

2.3. Image Analysis

Three senior radiologists with more than 8 years of experience in abdominal MRI diagnosis independently measured the T₂ values and ADC values using Philips Intellispace Portal (Version 11.1) or Siemens Syngo VIA workstation in a blinded manner (unaware of patients' clinical/pathological data).

Criteria for drawing the region of interest (ROI): (1) Slice selection: 3 slices (the maximum cross-section of the lesion + 1 adjacent slice above and below); (2) ROI range: Covering the entire solid component of the tumor, avoiding visible necrotic areas (T2WI signal ≥ 2 times the muscle signal), hemorrhagic areas, mucus, and the muscular layer of the intestinal wall; (3) ROI area: 15-30 mm² per slice; the final value was the average of the 3 slices [

10].

Consistency verification: If the measurement difference among the 3 radiologists exceeded 10%, a consensus was reached through joint image review; otherwise, the average value was taken. The coefficient of variation (CV, ≤ 15% considered acceptable) was used to evaluate intra-group consistency, and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC, ≥ 0.90 considered excellent) was used to assess inter-observer consistency.

Image quality scoring: 0 points: Severe artifacts (tumor boundary unidentifiable, unable to draw ROI); 1 point: Mild artifacts (tumor boundary clear, no impact on ROI drawing); 2 points: No artifacts (uniform tumor signal, clear structure).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data processing and analysis include: (1) Grouping criteria: MSS group: All 4 IHC markers positive or only 1 marker missing [MSI-low (MSI-L)]; MSI group: ≥ 2 IHC markers missing, confirmed by MSI-PCR. (2) Normality test: Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Homogeneity of variance test: Levene test. (3) Univariate analysis: Independent samples t-test (comparison of T2/ADC values between groups); one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (comparison of different clinical stages). (4) Multivariate analysis: Binary logistic regression combined with SMOTE oversampling (to address class imbalance,oversampling ratio = 1:1,k-nearest neighbors = 5) and L2 regularization (to avoid overfitting,λ=0.01) was used, and confounding factors (BMI, tumor location, image quality score) were included in the model. (5) Model validation: 10-fold cross-validation (Stratified by MSI status) and Bootstrap resampling (1000 times) were used to evaluate stability; Delong test was applied to compare the AUC of single/combined parameters.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

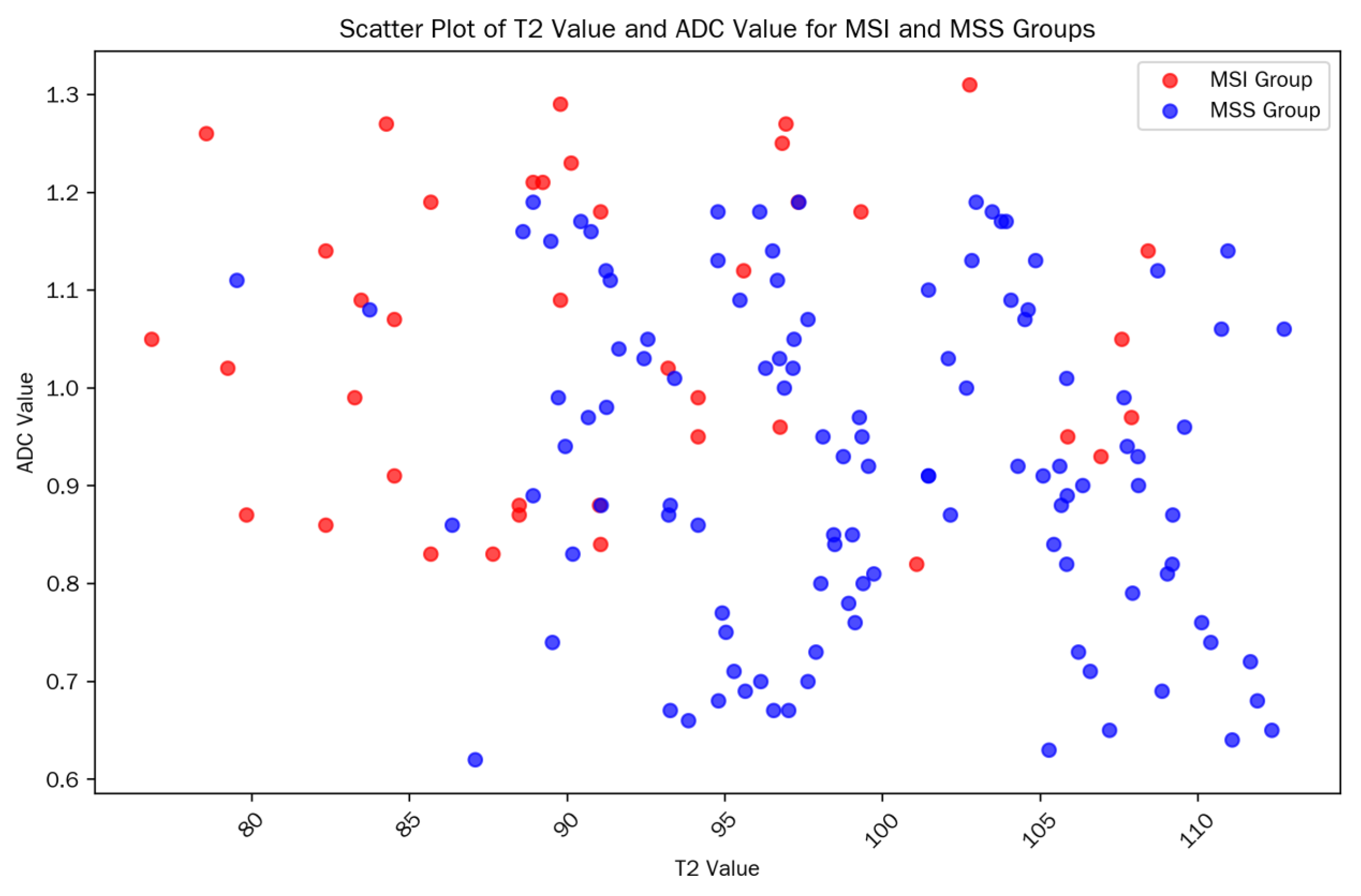

A total of 152 patients with pathologically confirmed rectal cancer were included in this study and divided into two groups according to microsatellite status: 40 cases in the MSI group (accounting for 26.3%, with 12/18/10 cases in clinical stage I/II/III, respectively) and 112 cases in the MSS group (accounting for 73.7%, with 28/50/34 cases in clinical stage I/II/III, respectively). There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics such as age, gender, BMI, tumor location, clinical stage, and image quality score between the two groups (all p > 0.05), indicating comparability; only the T₂ value and ADC value showed significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.001). The statistical data are shown in

Table 1. The scatter plot of T2/ADC values in each group is shown in

Figure 1.

The consistency of measurement results among three radiologists was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The results showed that the measurements of T2 values and ADC values both exhibited excellent inter-rater consistency (ICC_T2 = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91-0.96; ICC_ADC = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.88-0.95).

The consistency between IHC and MSI-PCR results was excellent: Kappa value = 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.85-0.99), with 145 consistent cases (accounting for 95.4%), including 38 consistent cases in the MSI group (95.0%) and 107 consistent cases in the MSS group (95.5%), which verified the reliability of MSI status determination. In terms of image quality, 110 cases (72.4%) scored 2 points (no artifacts, uniform tumor signal, clear structure), and 42 cases (27.6%) scored 1 point (mild artifacts, no impact on ROI drawing); no cases scored 0 points (severe artifacts), which met the measurement requirements.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients and inter-group comparative analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients and inter-group comparative analysis.

| Parameter |

MSI group (n=40) |

MSS group (n=112) |

Test statistic |

p-value |

| Age (years) |

62.5 ± 10.3 |

63.8 ± 9.6 |

t = -0.71 |

0.478 |

| Gender (male/female) |

18/22 |

60/52 |

χ² = 0.12 |

0.728 |

| BMI (kg/m²) |

24.1 ± 2.3 |

23.8 ± 2.5 |

t = 0.65 |

0.516 |

| Tumor location (low/middle/high) |

15/17/8 |

42/50/20 |

χ² = 0.58 |

0.748 |

| T₂ value (ms) |

92.18 ± 7.21 |

99.47 ± 7.85 |

t = -5.89 |

< 0.001 |

| ADC value (×10⁻³ mm²/s) |

1.06 ± 0.18 |

0.91 ± 0.19 |

t = 4.78 |

< 0.001 |

| Clinical stage (I/II/III) |

12/18/10 |

28/50/34 |

χ² = 0.35 |

0.84 |

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of T2/ADC values in each group; data points in the MSI group are concentrated in the "low T2 value-high ADC value" region.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of T2/ADC values in each group; data points in the MSI group are concentrated in the "low T2 value-high ADC value" region.

3.2. Results of Univariate Analysis

T₂ value: The T₂ value in the MSI group was significantly lower than that in the MSS group (92.18 ± 7.21 ms vs. 99.47 ± 7.85 ms, t = -5.89, p < 0.001), suggesting that MSI-type tumors have lower signals on T₂ mapping images.

ADC value: The ADC value in the MSI group was significantly higher than that in the MSS group (1.06 ± 0.18 vs. 0.91 ± 0.19 × 10⁻³ mm²/s, t = 4.78, p < 0.001), indicating that MSI-type tumors have less restricted water molecule diffusion.

There were no statistically significant differences in T₂ values and ADC values measured by different brands of MRI scanners (Philips Elition and Siemens Prisma) within the MSI group (T₂ value: 91.52 ± 6.21 vs. 91.38 ± 6.25 ms, p = 0.921; ADC value: 1.05 ± 0.15 vs. 1.04 ± 0.16 × 10⁻³ mm²/s, p = 0.876), indicating that scanner differences had no significant impact on the measurement results.

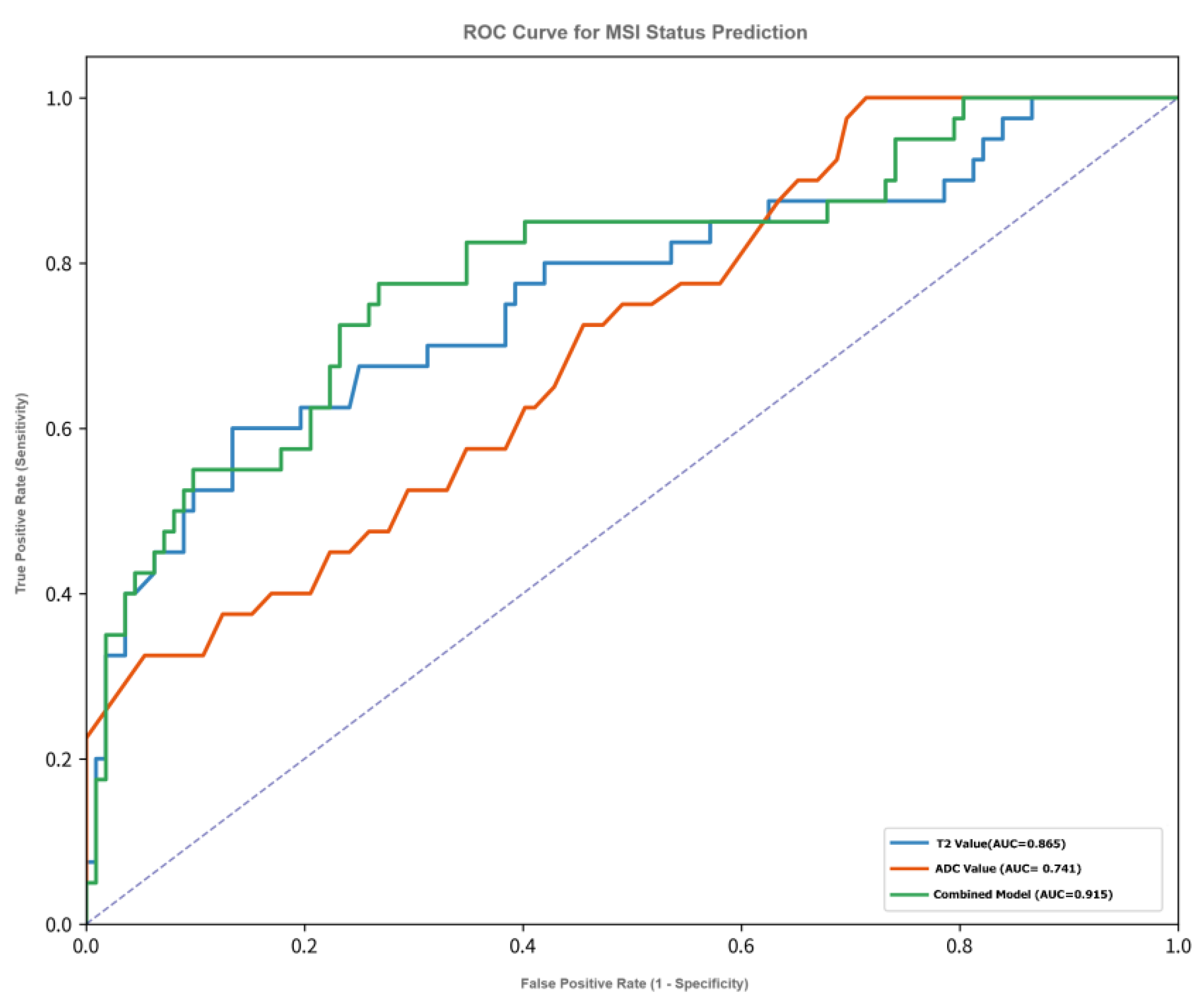

ROC curve analysis (see

Figure 2) showed that single imaging parameters had predictive value for the MSI status of rectal cancer:

T₂ value: AUC = 0.865 (95% CI: 0.798-0.932), optimal cutoff value = 94.5 ms, Maximum Youden Index=66.4%,corresponding sensitivity = 82.5%, specificity = 83.9%, positive predictive value (PPV) = 66.0%, negative predictive value (NPV) = 92.7%.

ADC value: AUC = 0.741 (95% CI: 0.652-0.830), optimal cutoff value = 0.97 × 10⁻³ mm²/s, Maximum Youden Index=46.4%,sensitivity = 75.0%, specificity = 71.4%, PPV = 51.7%, NPV = 87.5%.

In comparison, the diagnostic efficacy of T₂ value was significantly superior to that of ADC value (Delong test: Z = 2.41, p = 0.016).

Figure 2.

ROC curve for MSI status prediction, including reference line (AUC=0.5), T2 value (AUC=0.865), ADC value (AUC=0.741), and combined model (AUC=0.915, with 95% CI interval band marked).

Figure 2.

ROC curve for MSI status prediction, including reference line (AUC=0.5), T2 value (AUC=0.865), ADC value (AUC=0.741), and combined model (AUC=0.915, with 95% CI interval band marked).

3.3. Comparison of Imaging Parameters Among Different Clinical Stages (Table 2)

One-way ANOVA results showed:

T₂ value: There was a statistically significant difference among different clinical stages (F = 3.48, p = 0.033). Specifically, the T₂ value in stage III (99.75 ± 6.90 ms) was significantly higher than that in stage I (96.72 ± 7.50 ms, p = 0.043), suggesting that the T₂ value tends to increase with tumor progression.

ADC value: There was no statistically significant difference among different clinical stages (F = 0.93, p = 0.401), indicating that the ADC value is less affected by tumor stage.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Performance of the Combined Model Across Different Clinical Stages.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Performance of the Combined Model Across Different Clinical Stages.

| Clinical Stage |

Number of Cases (MSI/MSS) |

AUC (95% CI) |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

| Stage I |

12/28 |

0.89 (0.81-0.97) |

83.3 |

89.3 |

76.2 |

92.9 |

| Stage II |

18/50 |

0.92 (0.86-0.98) |

82.2 |

90.0 |

77.8 |

92.3 |

| Stage III |

10/34 |

0.90 (0.82-0.98) |

80.0 |

88.2 |

72.7 |

91.2 |

3.4. Construction of Multivariate Logistic Regression Model

Taking "MSI status" as the dependent variable, a binary logistic regression model was constructed by including T₂ value, ADC value, and potential confounding factors (BMI, tumor location, image quality score) (combined with SMOTE oversampling to address class imbalance and L2 regularization to avoid overfitting). The results are shown in

Table 3.

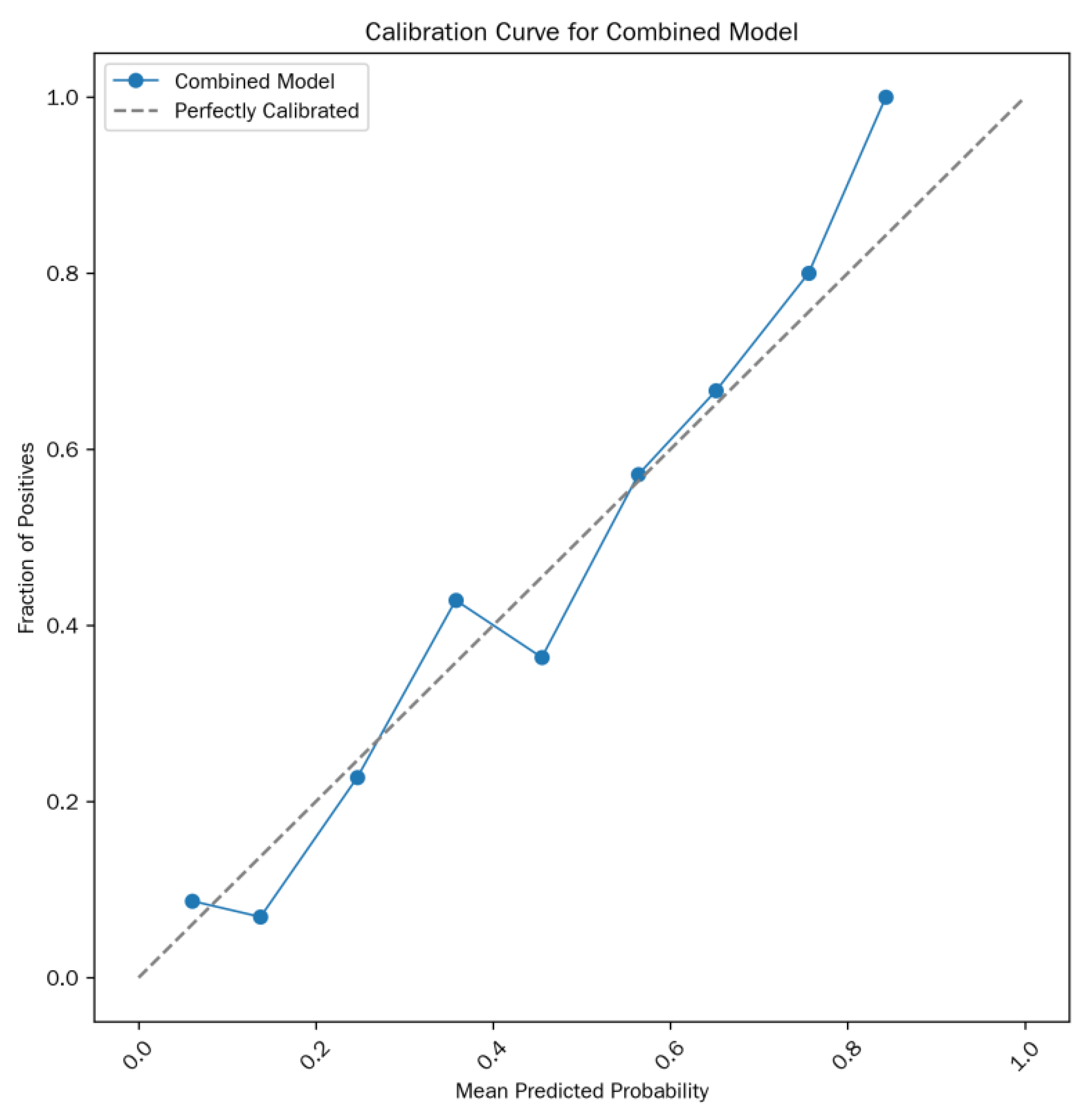

Model formula: Logit(P) =-13.15 + 0.09×T₂ value + 4.32×ADC value (where P is the predicted probability of MSI status). The calibration curve is shown in

Figure 3.

Table 3.

Parameters of the multivariate logistic regression model (verified by Bootstrap resampling).

Table 3.

Parameters of the multivariate logistic regression model (verified by Bootstrap resampling).

| Variable |

β coefficient |

Standard error (SE) |

Wald χ² value |

p-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| Intercept |

-13.15 |

3.38 |

15.22 |

< 0.001 |

- |

| T₂ value |

0.09 |

0.03 |

7.31 |

0.006 |

1.09 (1.03-1.16) |

| ADC value |

4.32 |

1.43 |

8.98 |

0.002 |

74.15 (8.53-643.21) |

| BMI |

-0.05 |

0.03 |

2.81 |

0.094 |

0.95 (0.89-1.01) |

| Tumor location (middle vs. low) |

0.13 |

0.36 |

0.13 |

0.719 |

1.14 (0.55-2.30) |

| Image quality (2 points vs. 1 point) |

-0.22 |

0.39 |

0.32 |

0.573 |

0.80 (0.40-1.59) |

Figure 3.

Calibration curve of the combined model; most points are close to the ideal calibration line; Brier score = 0.078; Hosmer-Lemeshow test p = 0.554.

Figure 3.

Calibration curve of the combined model; most points are close to the ideal calibration line; Brier score = 0.078; Hosmer-Lemeshow test p = 0.554.

3.5. Diagnostic Efficacy of the Combined Model

The diagnostic performance of the combined prediction model based on T₂ value + ADC value was significantly superior to that of single parameters:

ROC curve (see

Figure 2): AUC = 0.915 (95% CI: 0.865-0.965), Maximum Youden Index=71.8%,sensitivity = 82.5%, specificity = 89.3%, PPV = 75.0%, NPV = 93.8%.

Comparison with single parameters: The AUC of the combined model was significantly higher than that of T₂ value (Z = 2.43, p = 0.015) and ADC value (Z = 4.05, p < 0.001).

Two methods were used to verify model stability:

10-fold cross-validation: Mean AUC = 0.906 (95% CI: 0.850-0.962), and the AUC fluctuation range across folds was < 5%.

Bootstrap resampling (1000 times): Mean AUC = 0.913 (95% CI: 0.865-0.961), indicating that the model maintained stable diagnostic performance across different sample subsets.

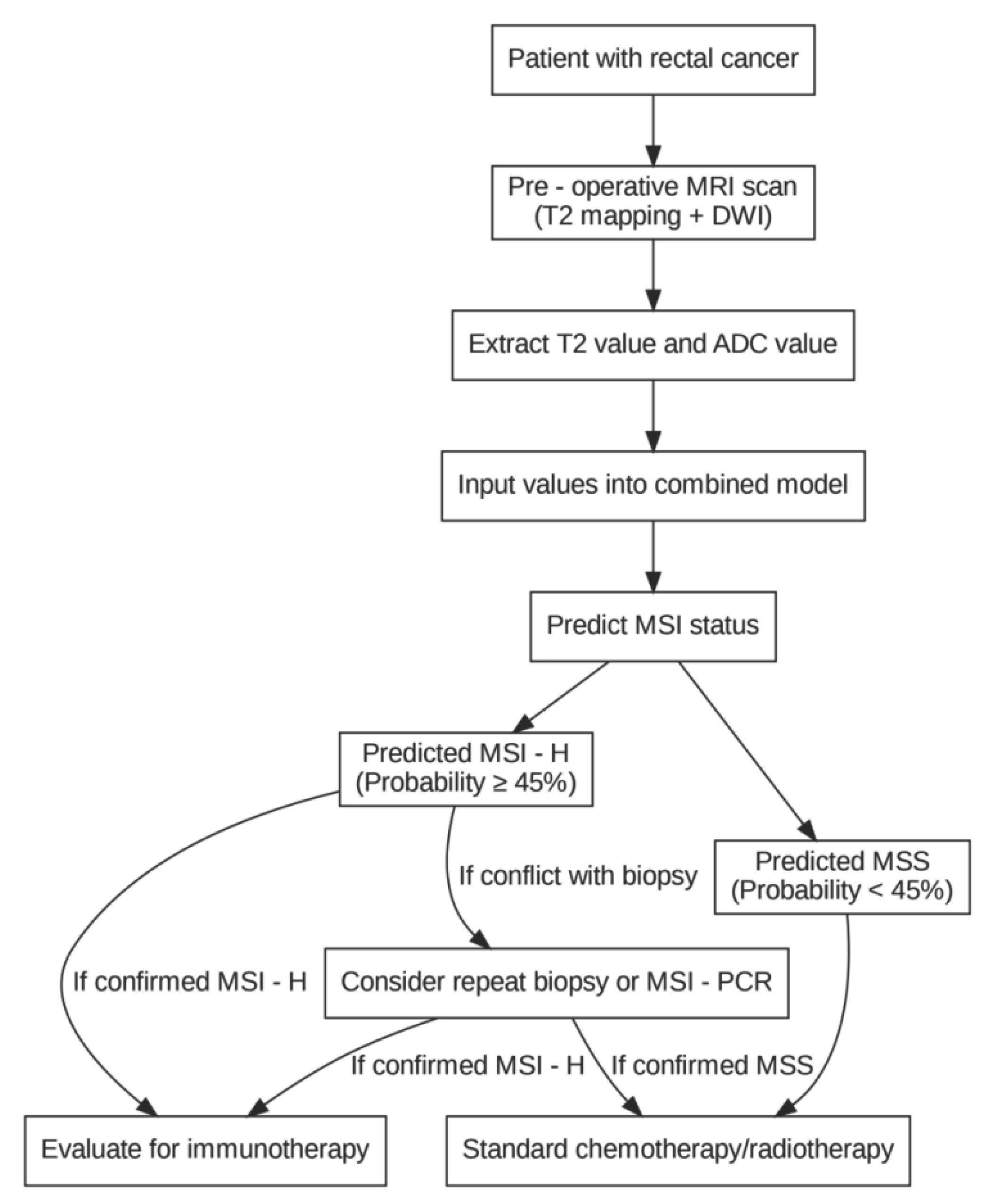

The clinical decision-making flowchart for MSI prediction is shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Clinical decision-making flowchart for MSI prediction. Note: Optimal cutoff probability = 45% (determined by the maximum Youden index); if there is a conflict between the model prediction and biopsy results, repeated MSI-PCR verification is recommended.

Figure 4.

Clinical decision-making flowchart for MSI prediction. Note: Optimal cutoff probability = 45% (determined by the maximum Youden index); if there is a conflict between the model prediction and biopsy results, repeated MSI-PCR verification is recommended.

4. Discussion

By retrospectively analyzing preoperative MRI data of 152 patients with pathologically confirmed rectal cancer (40 cases in the MSI group and 112 cases in the MSS group), this study systematically explored the value of quantitative T₂ mapping technique (T₂ value) and ADC value in predicting the MSI status of rectal cancer for the first time, providing a more evidence-based new imaging scheme for the non-invasive preoperative assessment of MSI status in rectal cancer.

Diagnostic Value of Single Parameters: This study further confirmed that there were significant differences in quantitative imaging parameters between the MSI group and the MSS group: the T₂ value in the MSI group was significantly lower than that in the MSS group (92.18 ± 7.21 ms vs. 99.47 ± 7.85 ms, t = -5.89, p < 0.001), and the ADC value in the MSI group was significantly higher than that in the MSS group (1.06 ± 0.18 × 10⁻³ mm²/s vs. 0.91 ± 0.19 × 10⁻³ mm²/s, t = 4.78, p < 0.001). ROC curve analysis showed that the AUC of T₂ value alone for predicting MSI was 0.865 (95% CI: 0.798-0.932), with an optimal cutoff value of 94.5 ms, corresponding to a sensitivity of 82.5% and a specificity of 83.9%; the AUC of ADC value alone for prediction was 0.741 (95% CI: 0.652-0.830), with an optimal cutoff value of 0.97 × 10⁻³ mm²/s, a sensitivity of 75.0%, and a specificity of 71.4%. The Delong test clearly showed that the diagnostic efficacy of T₂ value was significantly superior to that of ADC value (Z = 2.41, p = 0.016), further supporting that T₂ value is a better single imaging marker for distinguishing MSI from MSS.

One-way ANOVA in this study found that there was a statistically significant difference in T₂ value among different clinical stages (F = 3.48, p = 0.033). Specifically, the T₂ value in stage III (99.75 ± 6.90 ms) was significantly higher than that in stage I (96.72 ± 7.50 ms, p = 0.043), suggesting that the T₂ value tends to increase with tumor progression; however, there was no significant difference in ADC value among different clinical stages (F = 0.93, p = 0.401), indicating that the ADC value is less affected by tumor stage and may be a more stable marker across stages. This stage-specific difference provides a more refined reference for the MSI assessment of rectal cancer at different progression stages.

Efficacy Improvement of Multi-Parameter Combination: A binary logistic regression model was constructed, with the model formula: Logit(P) =-13.15 + 0.09×T₂ value + 4.32×ADC value (P is the predicted probability of MSI status). It was confirmed that the diagnostic efficacy of the combined model was significantly superior to that of single parameters: the Delong test showed that the AUC of the combined model was significantly higher than that of T₂ value (Z = 2.43, p = 0.015) and ADC value (Z = 4.05, p < 0.001). Especially, the improvements in specificity and NPV (5.4% increase in specificity and 1.1% increase in NPV compared with T₂ value) make it more clinically valuable in "ruling out MSI status and confirming MSS status", which can effectively avoid excessive immunotherapy recommendations for MSS patients and reduce missed diagnoses of MSI patients.

Discussion on Pathological Mechanisms: This study observed that the T₂ value in the MSI group was significantly lower, and its potential mechanism may be related to the unique tumor microenvironment, such as more abundant lymphocyte infiltration and reduced stromal fibrosis [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, this is only a speculation based on the literature, and no direct imaging-pathological correlation analysis was conducted in this study. Therefore, future studies will explore the specific association between T₂ value and tumor stromal components, cell density, and other microstructures by matching preoperative MRI with postoperative large tissue section pathology to verify this hypothesis. Previous studies have shown that MSI-H colorectal cancer is usually accompanied by significant lymphocyte infiltration and less stromal fibrosis [

11,

12]. The reduction in fibrotic tissue means a decrease in the proportion of bound water, which may lead to a shorter T₂ value; at the same time, abundant cellular components (such as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes) may also affect the relaxation properties of tissues. However, the above explanations are inferences based on existing literature, and no direct imaging-pathological correlation analysis was performed in this study. This interesting finding points out the direction for future research; subsequent plans will explore the specific association between T₂ mapping values and tumor stromal components, cell density, and other microstructures by accurately matching preoperative MRI with postoperative large tissue section pathology.

Clinical Significance and Translational Value: Current assessment of MSI status in rectal cancer relies on invasive biopsy, which has sampling errors (e.g., local sampling bias caused by tumor heterogeneity) and time delays (3-5 days from biopsy to result reporting). However, high-resolution rectal MRI is a routine item in preoperative assessment. Incorporating quantitative T₂ values and ADC values into routine MRI analysis can realize "one examination, multiple assessments" (simultaneously evaluating tumor stage and MSI status), providing non-invasive and real-time MSI information for clinical decision-making [

13,

14,

15].

Limitations of This Study: First, this is a single-center retrospective study with a relatively small sample size in the MSI group (n=40). Although this is consistent with the overall incidence of MSI-H in rectal cancer (approximately 15-20%), it may lead to insufficient statistical power and potential overfitting of the model. Although we internally evaluated the model performance through strict statistical methods (such as cross-validation), the imbalance in sample size may affect the stability of subgroup analysis (e.g., clinical stage) and the generalizability of conclusions. Second, all data were obtained from MRI scanners of the same model, which ensured the consistency of sequence parameters, but the generalizability of the results needs to be treated with caution. Finally, this study only used T₂ mapping and DWI (ADC value), and did not include parameters reflecting tumor angiogenesis and microstructure such as dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (e.g., Ktrans, Ve values) or diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) [

16,

17]; meanwhile, blood biomarkers (e.g., MSI locus mutations in circulating tumor DNA [ctDNA]) were not incorporated [

18,

19]. Future plans include verifying the generalizability of the model through multi-center, large-sample prospective studies and exploring the use of resampling techniques or cost-sensitive learning algorithms to address the class imbalance issue [

20,

21,

22,

23].

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that T₂ mapping technique combined with ADC value can non-invasively and accurately predict the MSI status of rectal cancer. The AUC of the combined model reaches 0.915, and it maintains stable diagnostic performance across different clinical stages, showing important clinical application value. Despite limitations such as single-center design and small sample size, this study provides a new paradigm for the imaging assessment of MSI in rectal cancer. In the future, through multi-center verification, technical standardization, and multimodal combination, this technology is expected to be incorporated into the preoperative routine assessment process of rectal cancer, providing strong support for precision treatment decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhao Xiaoxin. and Sun Meifang.; methodology, Zhao Xiaoxin.; validation,Zhao Xiaoxin, and Sun Meifang.; formal analysis,Zhao Xiaoxin.; investigation, Sun Meifang.; resources, Ma Hongzhou; data curation, Ma Hongzhou; writing—original draft preparation,Zhao Xiaoxin.; writing—review and editing, Ma Hongzhou.; visualization, Sun Meifang.; supervision, Sun Meifang.; project administration,Sun Meifang.; funding acquisition, Sun Meifang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Heze Hospital Affiliated to Shandong Provincial Hospital (Approval No.: 2025-KJKY022-074).

Informed Consent Statement

As this was a retrospective study using de-identified data without any interventional procedures, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee..

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Radiology and Pathology of Heze Hospital Affiliated to Shandong Provincial Hospital for their support in data collection and processing.During the preparation of this study, the authors used Deepseek for the purposes of data analysis and generating graphics. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| dMMR |

Deficient Mismatch Repair |

| MMR |

Mismatch Repair |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MSI |

Microsatellite Instability |

| MSI-H |

Microsatellite Instability-High |

| MSI-L |

Microsatellite Instability-Low |

| MSS |

Microsatellite Stability |

| ROI |

Region of Interest |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

References

- Swets, M.; Graham Martinez, C.; van Vliet, S.; et al. Microsatellite instability in rectal cancer: What does it mean? A study of two randomized trials and a systematic review of the literature. Histopathology 2022, 81, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, E.; Reynolds, I.S.; McNamara, D.A.; Prehn, J.H.M.; Burke, J.P. Microsatellite instability and response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2020, 34, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desir, A.D.; Ali, F.G. Microsatellite Instability in Colorectal Cancer: The Evolving Role of Immunotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum 2023, 66, 1303–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Immunotherapy-Based Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Proficient Mismatch Repair or Microsatellite Stable Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer (TORCH). J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, 3308–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Xu, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Multiparametric MRI subregion radiomics for preoperative assessment of high-risk subregions in microsatellite instability of rectal cancer patients: A multicenter study. Int J Surg 2024, 110, 4310–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, N.N. Colorectal Cancer: Preoperative Evaluation and Staging. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2022, 31, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludford, K.; Ho, W.J.; Thomas, J.V.; et al. Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab in Localized Microsatellite Instability High/Deficient Mismatch Repair Solid Tumors. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REACCT Collaborative. Microsatellite instability in young patients with rectal cancer: Molecular findings and treatment response. Br J Surg 2022, 109, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Xiao, B.Y.; Li, D.D.; et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab plus apatinib for locally advanced microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer (NEOCAP): A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2024, 25, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lu, T.; Tang, Q.; Yang, M.; Fan, Y.; Wen, M. The clinical value of applying diffusion-weighted imaging combined with T2-weighted imaging to assess diagnostic performance of muscularis propria invasion in mid-to-high rectal cancer. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2025, 50, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, F.; Salvatore, L.; Tamburini, E.; et al. Curative immune checkpoint inhibitors therapy in patients with mismatch repair-deficient locally advanced rectal cancer: A real-world observational study. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshenaifi, J.Y.; Vetere, G.; Maddalena, G.; et al. Mutational and co-mutational landscape of early onset colorectal cancer. Biomarkers 2025, 30, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, J.; et al. Development and validation of magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics models for preoperative prediction of microsatellite instability in rectal cancer. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, L.; Chen, N.; et al. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy Alone for Patients With Locally Advanced and Resectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer of dMMR/MSI-H Status. Dis Colon Rectum 2024, 67, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Xu, H.; et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for DNA mismatch repair proficient/microsatellite stable non-metastatic rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1523455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Ling, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xing, C. Tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in local advanced rectal cancer revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchi, F.; Palomba, A.; Messerini, L.; et al. Tumor angiogenesis in lymph node-negative rectal cancer: Correlation with clinicopathological parameters and prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol 2002, 9, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, M.; Rousseau, B.; Manca, P.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for POLE or POLD1 proofreading-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2024, 35, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, J.N.A.; Preto, D.D‘.; Lazarini, M.E.Z.N.; et al. PD-L1 expression and microsatellite instability (MSI) in cancer of unknown primary site. Int J Clin Oncol 2024, 29, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, B.; Wang, K.; et al. Multi-parametric MRI Habitat Radiomics Based on Interpretable Machine Learning for Preoperative Assessment of Microsatellite Instability in Rectal Cancer. Acad Radiol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Deng, S.; Han, X.; et al. Deep Learning Algorithm-Based MRI Radiomics and Pathomics for Predicting Microsatellite Instability Status in Rectal Cancer: A Multicenter Study. Acad Radiol 2025, 32, 1934–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.; Li, D.; Peng, J.; Shu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Q. A combinatorial MRI sequence-based radiomics model for preoperative prediction of microsatellite instability status in rectal cancer. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 11760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.Y.; Zhang, J.M.; Lin, Q.S.; et al. Noninvasive prediction of microsatellite instability in stage II/III rectal cancer using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging radiomics. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025, 17, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).