1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the second most common gynaecologic malignancy worldwide and its incidence is progressively increasing, particularly in industrialized countries [

1,

2,

3]. According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) guidelines EC staging is surgical, but MRI plays a pivotal role in optimizing treatment strategies[

4,

5]. The recently updated FIGO staging system integrated anatomic findings with pathologic and molecular variables to improve patients’ prognostic stratification[

4]. According to the 2023 update, tumor histological type and grade definition, that enable to subdivide ECs into aggressive and non-aggressive subtypes, as well as the presence of substantial lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) assessment, are crucial to correctly stage EC. However, discrepancies exist in tumor type and grade assessment between pre-operative biopsy and surgical specimen, and LVSI can be addressed on surgical specimen only [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Consequently, a definite preoperative MRI staging is often impossible [

11]

On the other hand, many papers explored the potential role of MRI as an additional tool for assessing EC’s biological behaviour. Many MRI features (e.g. presence of deep myometrial infiltration, large tumor size, high tumor/uterus volume ratio, and low ADC values) have been variably associated to high grade neoplasms and to the presence of LVSI[

6,

8,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The first-line treatment for endometrial cancer (EC), when feasible, is total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, sometimes combined with pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy; however, growing clinical evidence supports a more selective approach to lymph node dissection to reduce morbidity without compromising oncological outcomes, particularly in low-risk cases [

20].

A key factor guiding both treatment decisions and prognostic stratification is the presence of lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), defined as the migration of tumor cells into lymphatic and blood vessels adjacent to the primary tumor. LVSI is considered an early marker of lymphatic metastatic spread and is strongly correlated with lymph node metastases, pelvic recurrence, and decreased overall survival [

20,

21,

22]. Nonetheless, its detection is generally based on final histopathological evaluation.

Accurately identifying LVSI in the preoperative setting—ideally through MRI—could significantly improve risk classification and inform the need for more extensive surgical intervention and/or adjuvant therapies such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

The aim of our study was to identify MRI parameters that can be incorporated into the development of a nomogram capable of predicting tumor aggressiveness and the potential presence of LVSI in endometrial cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The Institutional Review Board approved our multicentre retrospective study; requirement for informed consent was waived. During the period January 2020 – December 2024, 273 consecutive patients affected by histologically proven EC who underwent preoperative pelvic MRI and surgery at the two participating Institutions (Central Hospital, Bolzano, Italy, and IRCSS Policlinico Agostino Gemelli, Rome, Italy) were considered for inclusion. Inclusion criteria were the availability of pre-operative pelvic MRI scan (within 4 weeks before surgery) in patients who did not receive any treatment before the scan (endometrial ablation, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, etc.). Exclusion criteria were non-accessible data on Institutional database (3/280, 1%), time between MRI and surgery >30 days (10/245, 4%), presence of motion or ferromagnetic artifacts (15/280, 6%). Therefore, our patient population encompassed 245 women with a median age of 66 year (range 58–74 years).

2.2. MRI Protocol

All MR examinations were performed on 1.5 T MRI scanners (Ingenia, Philips, Best, The Netherlands or Signa Excite; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) with the patient lying supine on the table, using multi-channel phased-array body coils. The patient was asked to fast 6 h before the examination and to void 1 h before it; moreover, 20 mg of butylscopolamine bromide (Buscopan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) were administered intramuscularly just before the beginning of the examination.

MRI pulse sequences and image parameters are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging protocol: pulse sequences and parameters.

Table 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging protocol: pulse sequences and parameters.

| Pulse Sequence |

Scanning Plane |

TR/TE (ms) |

Voxel Size (mm) |

FoV (mm) |

| FS T2-weighted TSE |

Axial (pelvis) |

7700/83 |

1,3x0,9x6,0 |

400 |

| T1-weighted TSE |

Axial (pelvis) |

730/10 |

0,9x0,6x6,0 |

350 |

| T2-weighted TSE |

Para-sagittal, para-axial, para-coronal (uterus) |

3200/82 |

0,5x0,5x4,0 |

250 |

| EPI (b=0,500,1000 s/mm2) |

Para-sagittal, pasa-axial (uterus) |

3100/98 |

2,0x1,0x5,0 |

250 |

| Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted TSE |

Para-sagittal, para-axial, para-coronal (uterus) |

606/9,5 |

1,3x0,8x4,0 |

250 |

| Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR perfusion (DCE; optional sequence) |

Axial, Para-Sagittal |

3.8/1.7 |

0,5x0,5x4,0 |

250 |

High-resolution T2-weighted images (T2-WI) and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (CE T1-WI) were acquired along three orthogonal planes (para-sagittal, para-axial and para-coronal), according to endometrial cavity longest axis, whereas diffusion-weighted images (DWI) were acquired on two planes only (para-axial and para-sagittal); apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were generated from isotropic diffusion-weighted images. CE T1-WI were acquired after an intravenous bolus injection of 0.1 mmolGd/kg of paramagnetic contrast material, followed by a 20 ml saline flush.

2.3. Image Analysis

Image analysis was performed by one radiologist (10 years of experience in pelvic MRI) on commercially available workstation. The reader was aware of the presence of a histologically proven EC, but unaware of surgical and histological findings.

Qualitative image analysis included lesion’s growth pattern (polypoid or infiltrative), presence of myometrial invasion (yes or no), presence of myometrial infiltration exceeding 50% of its thickness (yes or no), presence of cervical stromal invasion (yes or no), presence of serosal or subserosal involvement (yes or no), presence of tubaric or adnexal involvement (yes or no), presence of parametrial involvement (yes or no), presence of vaginal involvement (yes or no), presence of bladder or rectal involvement (yes or no), presence of pelvic nodal involvement (yes or no), presence of pelvic peritoneal carcinosis (yes or no).

Quantitative image analysis included EC and uterus 3 orthogonal diameters measurement, and of EC-to-serosa minimal distance measurement. EC’s maximum diameter was annotated. EC and uterus volumes were estimated by means of ellipsoid formula; EC/uterus volume ratio was calculated.

2.4. Histological and Laboratory Data

Histological data were retrieved from Institutional databases including EC’s histological type and grade, both on preoperative biopsy and on surgical specimen and presence of substantial LVSI on surgical specimen. G1-G2 endometrioid ECs’ were considered non-aggressive, whereas G3 endometrioid and non-endometrioid ECs’ were considered aggressive. Laboratory data could not be incorporated into the models due to their large unavailability.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

MedCalc (version 20, MedCalc Software) was used for all statistical analyses. RStudio (Version 2024.12.1+563) was used to generate the nomogram. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD or as median with interquartile range (IQR), depending on their distribution. Normality was assessed using the D’Agostino–Pearson test. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the influence of various independent variables on the probability of LVSI and aggressiveness. An independent-samples two-tailed t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test was applied, as appropriate, to compare continuous variables, while Fisher’s exact test and the chi-square test were used for dichotomous variables. Variables with P-values < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. However, for the LVSI multivariate logistic regression, we decided to exclude parameters such as serosal involvement, adnexal involvement, parametrial involvement, vaginal involvement, bladder involvement, rectal involvement, and the presence of lymph node involvement, metastases, and carcinomatosis, as their presence indicates higher disease stages. Similarly, for the aggressiveness multivariate logistic regression, we excluded parametrial involvement, vaginal involvement, bladder involvement, rectal involvement, and the presence of lymph node involvement, metastases, and carcinomatosis for the same reason. The model’s calibration was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

On pre-operative biopsy the pathologist classified 207/245 (84%) neoplasms as endometrioid and 38/245 (16%) as non-endometrioid (15/38 serous type, 3/38 clear cell type, and 20/38 as mixed type). 94/245 (38%) neoplasms were classified as grade 1, 81/245 (33%) as grade 2 and 70/245 (29%) as grade 3. Consequently, 171/245 (70%) ECs’ were considered non-aggressive and 74/245 (30%) were considered aggressive.

On MRI, growth pattern was defined polypoid in 168/245 (69%) cases and infiltrative in 77/245 (31%). Myometrial invasion was present in 204/245 (83%) of the cases, and it was >50% in 86/245 (17%). Cervical stromal invasion was present in 25/245 (10%) cases, serosal or subserosal involvement in 13/245 (5%), tubaric or adnexal involvement in 5/245 (2%), parametrial involvement in 5/245 (2%), vaginal involvement in 3/245 (1%), bladder or rectal involvement in 0/245 (0%), pelvic nodal involvement in 21/245 (9%), and pelvic peritoneal carcinosis in 3/245 (1%).

On surgical specimen the pathologist classified 206/245 (84%) neoplasms as endometrioid and 39/245 (16%) as non-endometrioid. 48/245 (20%) neoplasms were classified as grade 1, 113/245 (46%) as grade 2 and 84/245 (34%) as grade 3. In 71 cases, a tumor grade upgrade was observed between the biopsy and the final histology (mostly from G1 to G2 or G3), whereas 16 cases showed a downgrade. Consequently, 159/245 (65%) ECs’ were considered non-aggressive and 86/245 (35%) were considered aggressive. Substantial LVSI was present in 66/245 (27%) and absent in 179/245 (73%).

The results of the univariate analysis comparing patients with and without LVSI are reported in

Table 2.

In 22/245 (9.0%) cases, the tumor classification changed from non-aggressive to aggressive between the biopsy and the surgical specimen, while in 10/245 (4.1%) the opposite occurred.

Among the predictors included in the logistic regression analysis, MRI-detected cervical involvement significantly increased the odds of LVSI positivity (OR = 9.06, 95% CI: 2.83–29.05, P = 0.0002). In contrast, a greater minimal tumor-to-serosa distance was associated with a lower likelihood of LVSI (OR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.70–0.93, P = 0.0028). Additionally, tumor infiltration depth was a significant predictor (OR = 2.09, 95% CI: 1.04–4.21, P = 0.0391). The model demonstrates good discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.834 (95% CI: 0.779–0.879) and an overall classification accuracy of 78.35%. However, the sensitivity remains relatively low (43.08%). In contrast, specificity was high (92.17%), meaning that the model effectively excludes LVSI-negative cases. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test yielded a chi-squared value of 3.38 (DF = 8, P = 0.9081), indicating excellent model calibration and no significant deviation between observed and predicted values.

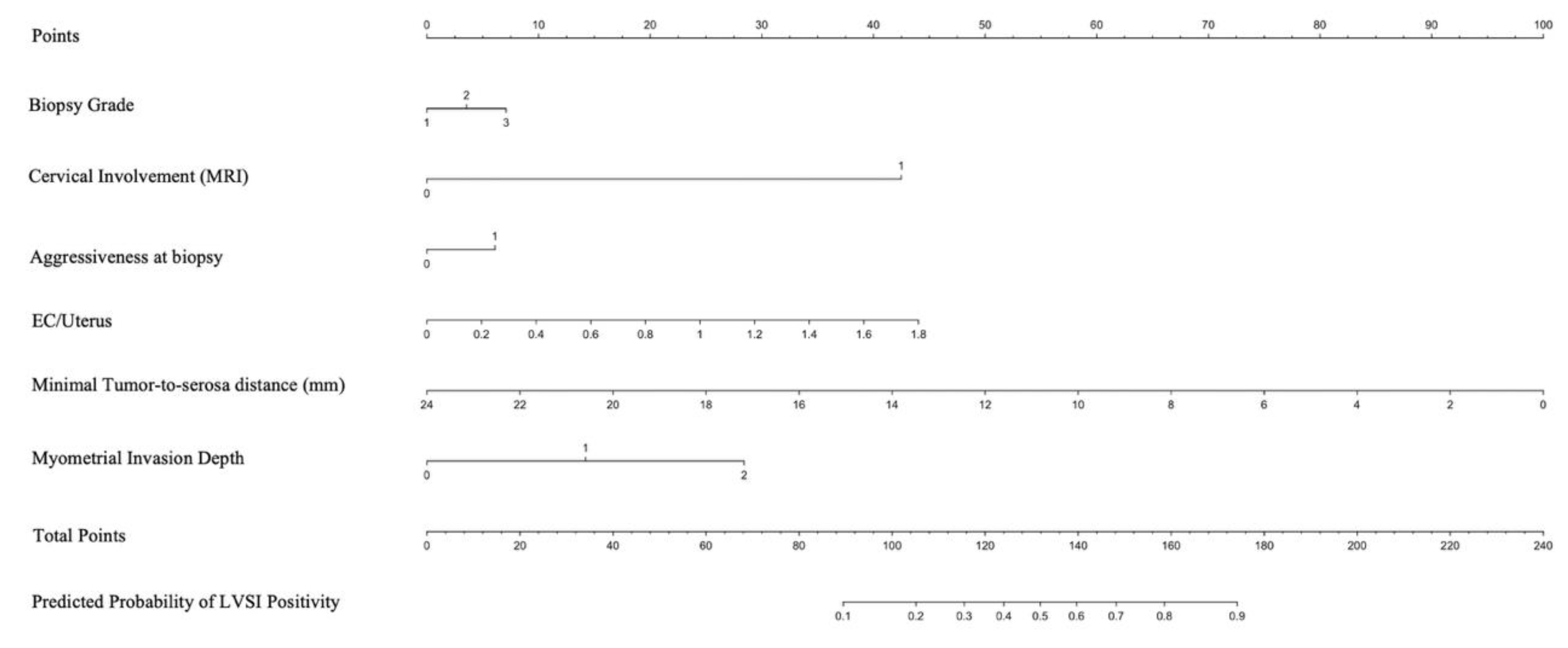

Figure 1 presents a nomogram developed based on the logistic regression model to predict the probability of LVSI positivity.

The nomogram integrates significant predictors, allowing for individualized risk estimation. Each predictor contributes a specific number of points, which are summed to determine the overall probability of LVSI. This graphical tool enhances clinical decision-making by providing an intuitive risk assessment based on the model’s findings.

The results of the univariate analysis comparing patients with and without aggressive histotypes are reported in

Table 3.

Among the predictors included in the logistic regression analysis, biopsy grade (OR = 8.92, 95% CI: 4.56–17.46, P < 0.0001) and histology (OR = 12.02, 95% CI: 2.47–58.57, P = 0.0021) significantly increased the odds of tumor aggressiveness. Additionally, serosal involvement on MRI was strongly associated with tumor aggressiveness (OR = 14.39, 95% CI: 1.36–152.31, P = 0.0268). Moreover, higher EC/uterus values were significantly associated with increased tumor aggressiveness (P = 0.0089). The model demonstrates excellent discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.932 (95% CI: 0.891–0.961) and an overall classification accuracy of 87.01%. Sensitivity and specificity were 79.76% and 91.16%, respectively. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test yielded a chi-squared value of 3.87 (DF = 8, P = 0.8688), confirming excellent model calibration.

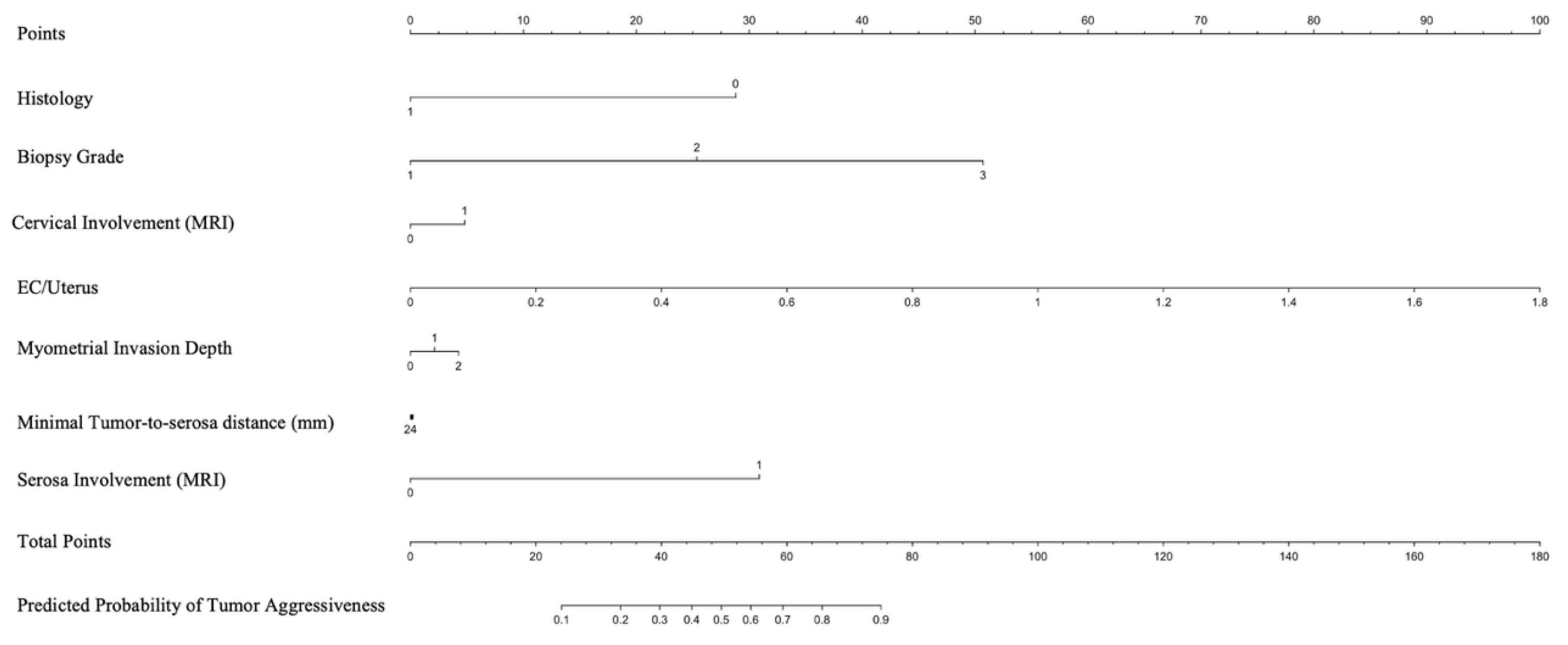

Figure 2 presents a nomogram developed based on the logistic regression model to predict the probability of tumor aggressiveness.

The nomogram integrates significant predictors, allowing for individualized risk estimation. Each predictor contributes a specific number of points, which are summed to determine the overall probability of tumor aggressiveness. This graphical tool enhances clinical decision-making by providing an intuitive risk assessment based on the model’s findings.

4. Discussion

In this multicenter retrospective study, we developed two predictive nomograms combining clinical-pathological and conventional MRI features to estimate, prior to surgery, the likelihood of tumor aggressiveness and lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) in patients with endometrial cancer. The analysis included 245 women who underwent preoperative pelvic MRI and surgery, with evaluation of tumor morphology, volume-related parameters, and biopsy-derived histological data.

One of the most critical aspects in the management of endometrial cancer is the reliability of endometrial biopsy in accurately determining tumor histotype and grade. In our cohort we found a discrepancy between biopsy and surgical specimen histology in 86 out of 245 cases (35%), confirming a substantial preoperative instability in histotype classification. We observed 71 cases of tumor grade upgrade between biopsy and final histology (mostly from G1 to G2 or G3), with 16 cases of downgrade, which may lead to an oncologically insufficient surgical procedure. In 22 cases, the tumor transitioned from non-aggressive to aggressive between the biopsy and the surgical specimen. This finding is consistent with previous studies [

23,

24,

25,

26] and underlines the limitations of biopsy-based histotype determination, due to tumor heterogeneity and sampling bias. As a result, there is often a systematic underestimation of tumor aggressiveness in the preoperative setting. Such discrepancies may directly impact surgical planning and decisions regarding lymphadenectomy or adjuvant treatment, thus supporting the development of radiological prediction models that are not solely dependent on biopsy findings.

To address this matter, we developed and validated two predictive nomograms based on MRI features and preoperative clinico-pathological data to estimate lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) and tumor aggressiveness in patients with endometrial cancer. The results show that combining morphological and quantitative MRI parameters with histological data from endometrial biopsy enables effective preoperative risk stratification, with high diagnostic performance (AUC = 0.834 for LVSI; AUC = 0.932 for tumor aggressiveness).

MRI variables significantly associated with greater tumor aggressiveness included deep myometrial invasion (>50%), cervical stromal involvement, uterine serosal invasion, an increased tumor-to-uterus volume ratio, and a reduced tumor-to-serosa distance, indicating its potential role as a predictive continuous variable. Histological variables significantly associated with tumor aggressiveness were grade 3 (G3) at biopsy and non-endometrioid histology. MRI features significantly associated with the presence of LVSI were cervical stromal invasion, deep myometrial invasion (>50%), a high tumor-to-uterus volume ratio, tumor infiltration depth, and a short tumor-to-serosa distance, suggesting that deeper tumor invasion increases the probability of LVSI. Histological predictors of LVSI included grade 3 and non-endometrioid histology on biopsy. These findings emphasize the ability of MRI-derived morphological features to provide reliable insights into tumor biology, particularly regarding vascular invasion and differentiation grade. The nomogram developed to predict tumor aggressiveness (defined as G3 or non-endometrioid histology) was built using seven variables: biopsy histotype, biopsy grade, cervical invasion, serosal involvement, tumor-to-uterus volume ratio, infiltration depth, and tumor-to-serosa distance. The model presented an AUC of 0.932 (95% CI: 0.891–0.961), with an overall accuracy of 87.0%, sensitivity of 79.8%, and specificity of 91.2%. Calibration was excellent according to the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p = 0.8688) indicating a strong ability to correctly classify aggressive tumors. The LVSI nomogram was developed using six variables: biopsy grade, aggressive histotype on biopsy, cervical invasion (MRI), tumor-to-uterus volume ratio, tumor infiltration depth, and tumor-to-serosa distance. The model showed an AUC of 0.834 (95% CI: 0.779–0.879), with an accuracy of 78.4%, sensitivity of 43.1%, and specificity of 92.2%, and demonstrated excellent calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow p = 0.9081). The low sensitivity reflects the clinical challenge of identifying LVSI preoperatively; however, the high specificity allows for reliable exclusion of negative cases, which can help guide conservative surgical approaches or avoid extended lymphadenectomy.

Our results are consistent with several previous studies that aimed to identify preoperative predictors of LVSI. Kim et al. [

27] proposed a predictive score based on tumor diameter, depth of myometrial invasion, tumor grade, and cervical involvement, achieving an AUC of 0.839, with 74.1% sensitivity and 80.5% specificity. Similarly, Meydanli et al. [

28]identified a combination of grade, tumor size, and percentage of myometrial invasion as predictive of LVSI, with an AUC of 0.90. Wang et al. [

6]combined multiparametric MRI radiomics and clinical variables, achieving AUCs of 0.914 in the training cohort and 0.912 in the validation cohort for LVSI prediction. Although our model is based on similar variables, it has the advantage of being entirely radiological, and therefore independent from intraoperative findings or invasive indices.

Several studies have also developed radiomics-based nomograms; Luo et al. [

25] achieved an AUC of 0.820 in the training cohort and 0.807 in the test set. Ma et al. [

29] reported AUCs of 0.959 in training and 0.926 in validation. Altough these results are comparable or even superior to ours, our nomograms, which are entirely based on MRI and histological features, present a practical advantage: they can be easily replicated in any MRI-equipped center and are simpler to implement, potentially making them more suitable for routine clinical settings without the need for advanced feature extraction software.

Regarding predictors of tumor aggressiveness, our findings confirm the association between histological grade, non-endometrioid histotype, and serosal involvement with aggressive tumors. These findings are in line with what was reported by Rafiee et al. [

30], who observed strong correlations between tumor grade, depth of invasion, and LVSI. Another paper [

26] showed that deeper myometrial invasion is strongly associated not only with LVSI, but also with lymph node metastases, recurrence, and poorer survival.

Our findings regarding the ability to predict LVSI agree with previous literature. Kim et al. [

27] identified deep myometrial invasion, tumor size, and cervical involvement as key predictors of LVSI. Radiomics studies [

6,

25,

29] reported similar or even higher AUCs, though they require complex pipelines and advanced software in comparison to our model, which is based on MRI and could be directly applied in clinical practice without the need for additional infrastructure.

The ability to predict LVSI and tumor aggressiveness before surgery could significantly improve preoperative management in EC patients, aiding in the selection for lymphadenectomy, sentinel node mapping, or adjuvant therapy. This is particularly relevant considering findings by Buechi et al. [

31], who showed that the presence of LVSI significantly reduces the negative predictive value of sentinel lymph node mapping.

Although our models were developed using a multicenter cohort with good generalizability, external validation is an essential step before clinical application. Predictive performance may vary depending on MRI protocols and population characteristics.

Our study has some limitations, first it is a retrospective study and may be subject to selection bias. In addition, the lack of a direct comparison with radiomics-based models limits our ability to draw firm conclusions. Furthermore, laboratory data could not be incorporated into the models due to their large unavailability. However, image standardization and blinded histological assessment remain among the strengths of the study. Future developments may include the integration of our nomograms with molecular biomarkers (such as MSI, p53, and L1CAM) and selected radiomic features using explainable AI algorithms, with the aim of building more robust and personalized hybrid prediction models.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Matteo Bonatti, Riccardo Valletta and Giacomo Avesani.; methodology, Riccardo Valletta, Giacomo Avesani, Martin Steinkasserer, Francesca Vanzo, Sara Notaro and Matteo Bonatti.; software, Vincenzo Vingiani and Bernardo Proner.; validation, Riccardo Valletta, Bernardo Proner and Caterina Vercelli.; formal analysis, Vincenzo Vingiani and Riccardo Valletta; investigation, Giacomo Avesani, Vincenzo Vingiani, Caterina Vercelli and Giovanni Negri.; resources, Matteo Bonatti, Martin Steinkasserer and Giovanni Negri.; data curation, Vincenzo Vingiani and Bernardo Proner; writing—original draft preparation, Riccardo Valletta and Giacomo Avesani writing—review and editing, all authors.; supervision, Matteo Bonatti. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| EC |

Endometrial Cancer |

| FIGO |

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

| LVSI |

Lymphovascular Space Invasion |

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65:87–108. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71:209–249. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2019) Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69:7–34. [CrossRef]

- Berek JS, Matias-Guiu X, Creutzberg C, et al (2023) FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 162:383–394. [CrossRef]

- Lavaud P, Fedida B, Canlorbe G, et al (2018) Preoperative MR imaging for ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO classification of endometrial cancer. Diagn Interv Imaging 99:387–396. [CrossRef]

- Wang JJ, Zhang XH, Guo XH, et al (2024) Prediction of Lymphovascular Space Invision in Endometrial Cancer based on Multi-parameter MRI Radiomics Model. Current Medical Imaging Formerly Current Medical Imaging Reviews 20:. [CrossRef]

- Taşkum İ, Bademkıran MH, Çetin F, et al (2024) A novel predictive model of lymphovascular space invasion in early-stage endometrial cancer. Journal of Turkish Society of Obstetric and Gynecology 21:37–42. [CrossRef]

- Qin Z, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al (2024) Evaluation of prognostic significance of lymphovascular space invasion in early stage endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 13:. [CrossRef]

- Bonatti M, Pedrinolla B, Cybulski AJ, et al (2018) Prediction of histological grade of endometrial cancer by means of MRI. Eur J Radiol 103:44–50. [CrossRef]

- Bonatti M, Stuefer J, Oberhofer N, et al (2015) MRI for local staging of endometrial carcinoma: Is endovenous contrast medium administration still needed? Eur J Radiol 84:208–214. [CrossRef]

- Avesani G, Bonatti M, Venkatesan AM, et al (2024) RadioGraphics Update: 2023 FIGO Staging System for Endometrial Cancer. RadioGraphics 44:. [CrossRef]

- Yue XN, He XY, Wu JJ, et al (2023) Endometrioid adenocarcinoma: combined multiparametric MRI and tumour marker HE4 to evaluate tumour grade and lymphovascular space invasion. Clin Radiol 78:e574–e581. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Xu P, Yang X, et al (2021) Association of Myometrial Invasion With Lymphovascular Space Invasion, Lymph Node Metastasis, Recurrence, and Overall Survival in Endometrial Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 79 Studies With 68,870 Patients. Front Oncol 11:. [CrossRef]

- Wang D-G, Ji L-M, Jia C-L, Shao M-J (2023) Effect of coexisting adenomyosis on tumour characteristics and prognosis of endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 62:640–650. [CrossRef]

- Shawn LyBarger K, Miller HA, Frieboes HB (2022) CA125 as a predictor of endometrial cancer lymphovascular space invasion and lymph node metastasis for risk stratification in the preoperative setting. Sci Rep 12:19783. [CrossRef]

- Lin Q, Lu Y, Lu R, et al (2022) Assessing Metabolic Risk Factors for LVSI in Endometrial Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ther Clin Risk Manag Volume 18:789–798. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Wang H, Wang X (2017) Preoperative CA125 and fibrinogen in patients with endometrial cancer: a risk model for predicting lymphovascular space invasion. J Gynecol Oncol 28:. [CrossRef]

- Petrila O, Nistor I, Romedea NS, et al (2024) Can the ADC Value Be Used as an Imaging “Biopsy” in Endometrial Cancer? Diagnostics 14:325. [CrossRef]

- Celli V, Guerreri M, Pernazza A, et al (2022) MRI- and Histologic-Molecular-Based Radio-Genomics Nomogram for Preoperative Assessment of Risk Classes in Endometrial Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 14:5881. [CrossRef]

- Concin N, Matias-Guiu X, Vergote I, et al (2021) ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 31:12–39. [CrossRef]

- Harris KL, Maurer KA, Jarboe E, et al (2020) LVSI positive and NX in early endometrial cancer: Surgical restaging (and no further treatment if N0), or adjuvant ERT? Gynecol Oncol 156:243–250. [CrossRef]

- Guntupalli SR, Zighelboim I, Kizer NT, et al (2012) Lymphovascular space invasion is an independent risk factor for nodal disease and poor outcomes in endometrioid endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 124:31–35. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Bandyopadhyay S, Semaan A, et al (2011) The Role of Frozen Section in Surgical Staging of Low Risk Endometrial Cancer. PLoS One 6:e21912. [CrossRef]

- Sala P, Morotti M, Menada MV, et al (2014) Intraoperative Frozen Section Risk Assessment Accurately Tailors the Surgical Staging in Patients Affected by Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 24:1021–1026. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Mei D, Gong J, et al (2020) Multiparametric MRI-Based Radiomics Nomogram for Predicting Lymphovascular Space Invasion in Endometrial Carcinoma. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 52:1257–1262. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Li X, Yang X, Wang J (2022) Development and Validation of a Nomogram Based on Metabolic Risk Score for Assessing Lymphovascular Space Invasion in Patients with Endometrial Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:15654. [CrossRef]

- Kim S Il, Yoon JH, Lee SJ, et al (2021) Prediction of lymphovascular space invasion in patients with endometrial cancer. Int J Med Sci 18:2828–2834. [CrossRef]

- Meydanli MM, Aslan K, Öz M, et al (2020) Is It Possible to Develop a Prediction Model for Lymphovascular Space Invasion in Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer? International Journal of Gynecological Pathology 39:213–220. [CrossRef]

- Ma C, Zhao Y, Song Q, et al (2023) Multi-parametric MRI-based radiomics for preoperative prediction of multiple biological characteristics in endometrial cancer. Front Oncol 13:. [CrossRef]

- Rafiee A, Mohammadizadeh F (2023) Association of Lymphovascular Space Invasion (LVSI) with Histological Tumor Grade and Myometrial Invasion in Endometrial Carcinoma: A Review Study. Adv Biomed Res 12:. [CrossRef]

- Buechi CA, Siegenthaler F, Sahli L, et al (2023) Real-World Data Assessing the Impact of Lymphovascular Space Invasion on the Diagnostic Performance of Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Endometrial Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 16:67. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).