Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Theoretical Foundations

Spectral Crossings and Topological Protection in Atomic Hamiltonians

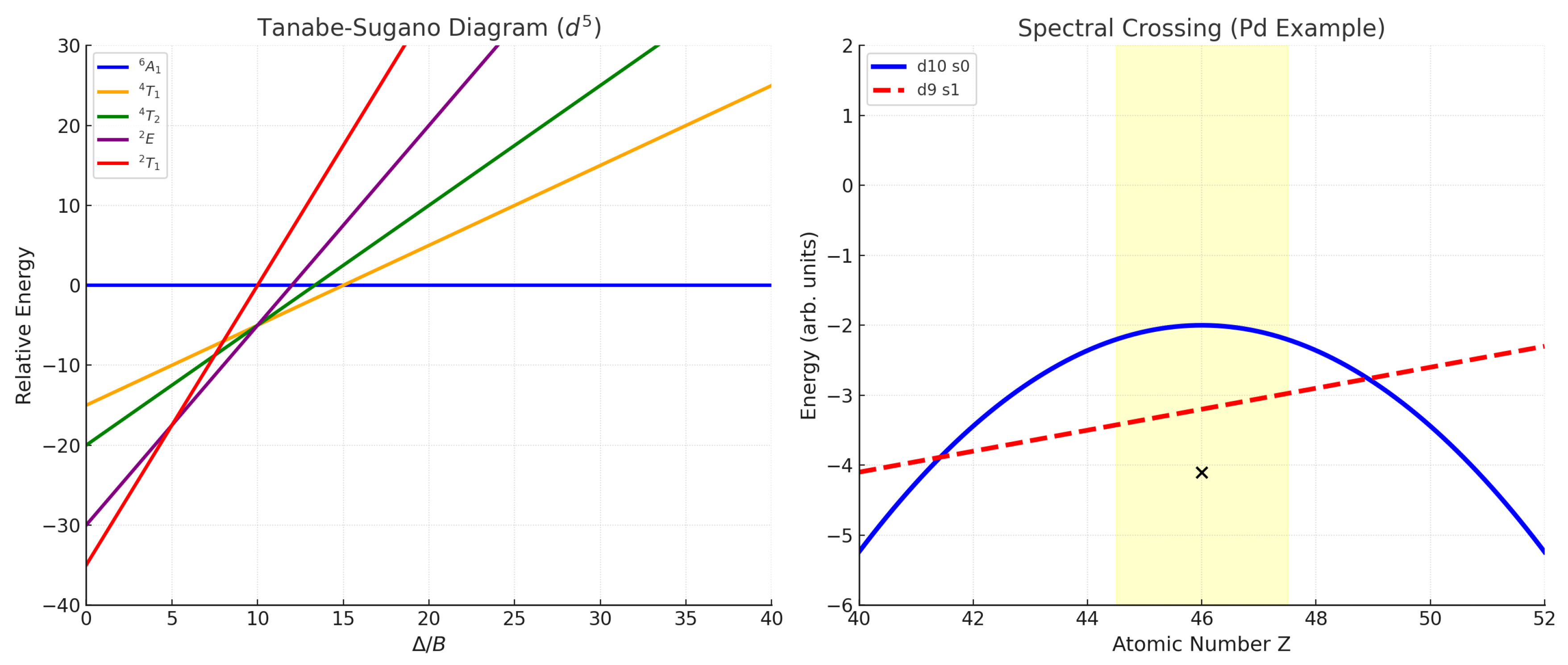

Spectral Crossing Mechanism

Topological Invariants and Berry Phase

Generalization and Predictive Power

Application to Other Transition Elements

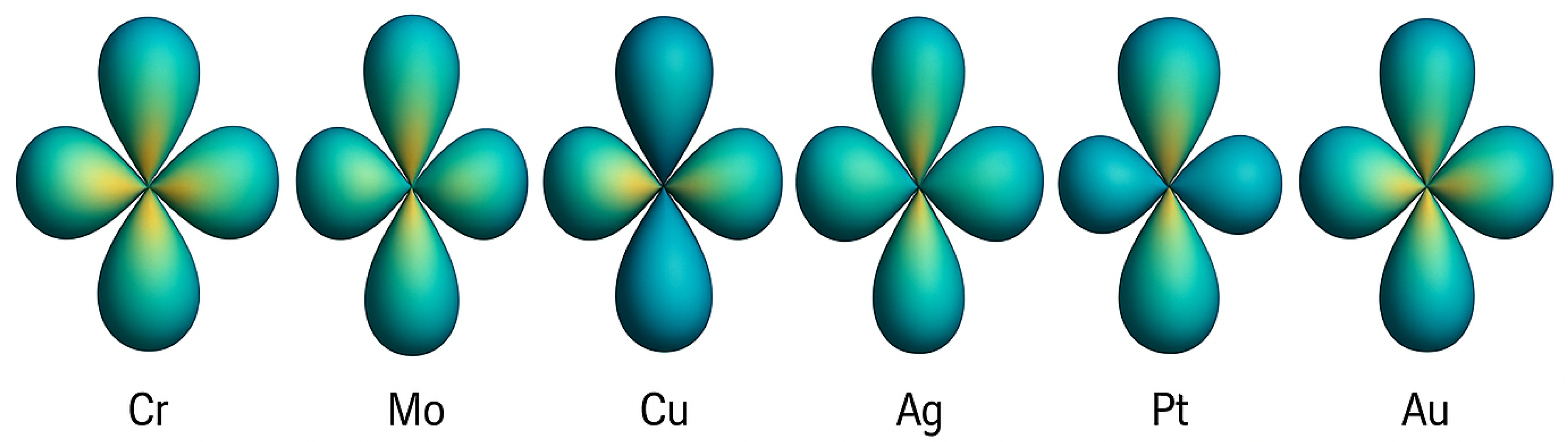

Platinum (): Competing Relativistic and Topological Effects

Copper and Silver (): Half- and Fully-Filled Stabilization

Gold (): Relativistic Reinforcement

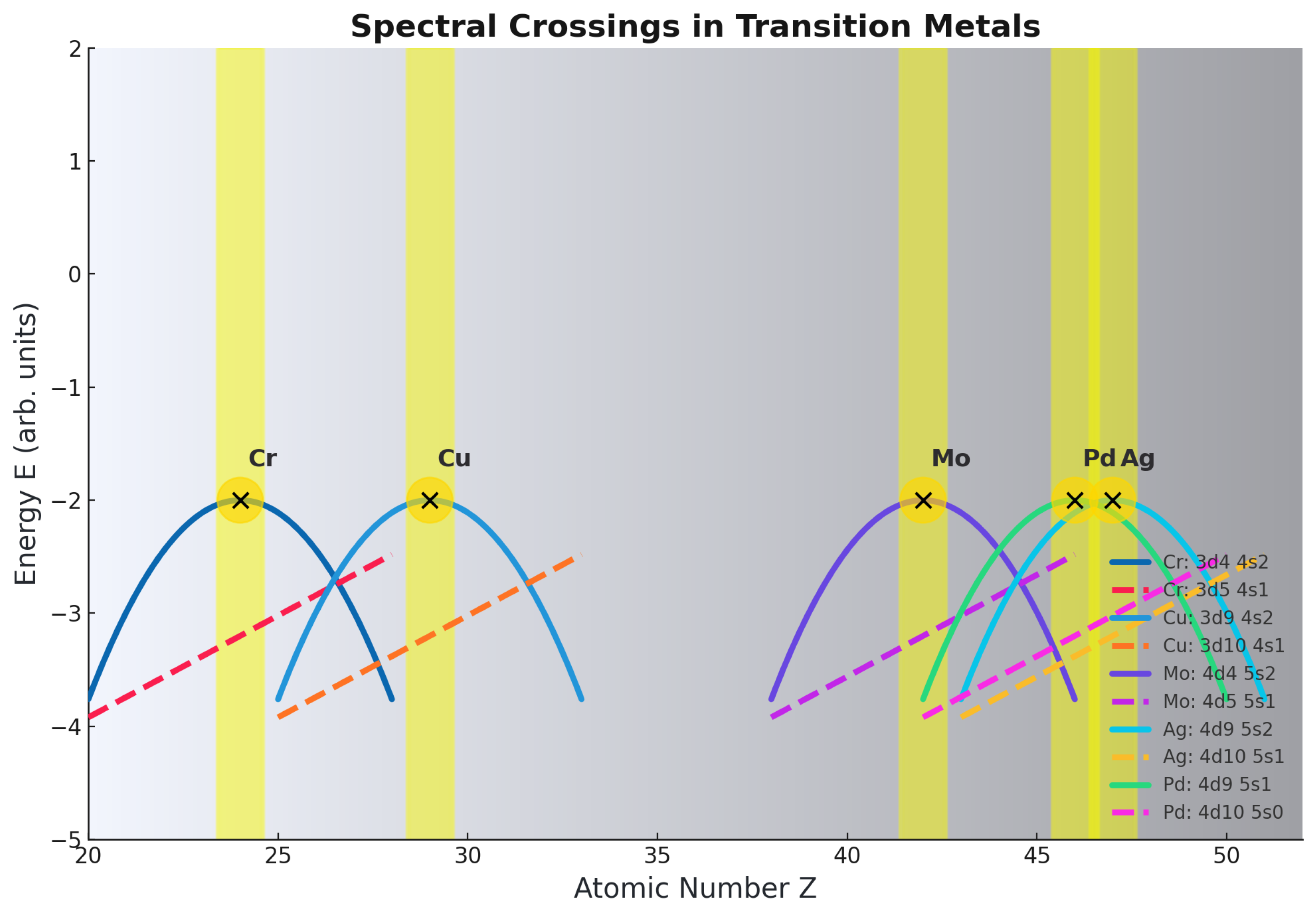

Chromium and Molybdenum (): Half-Filled

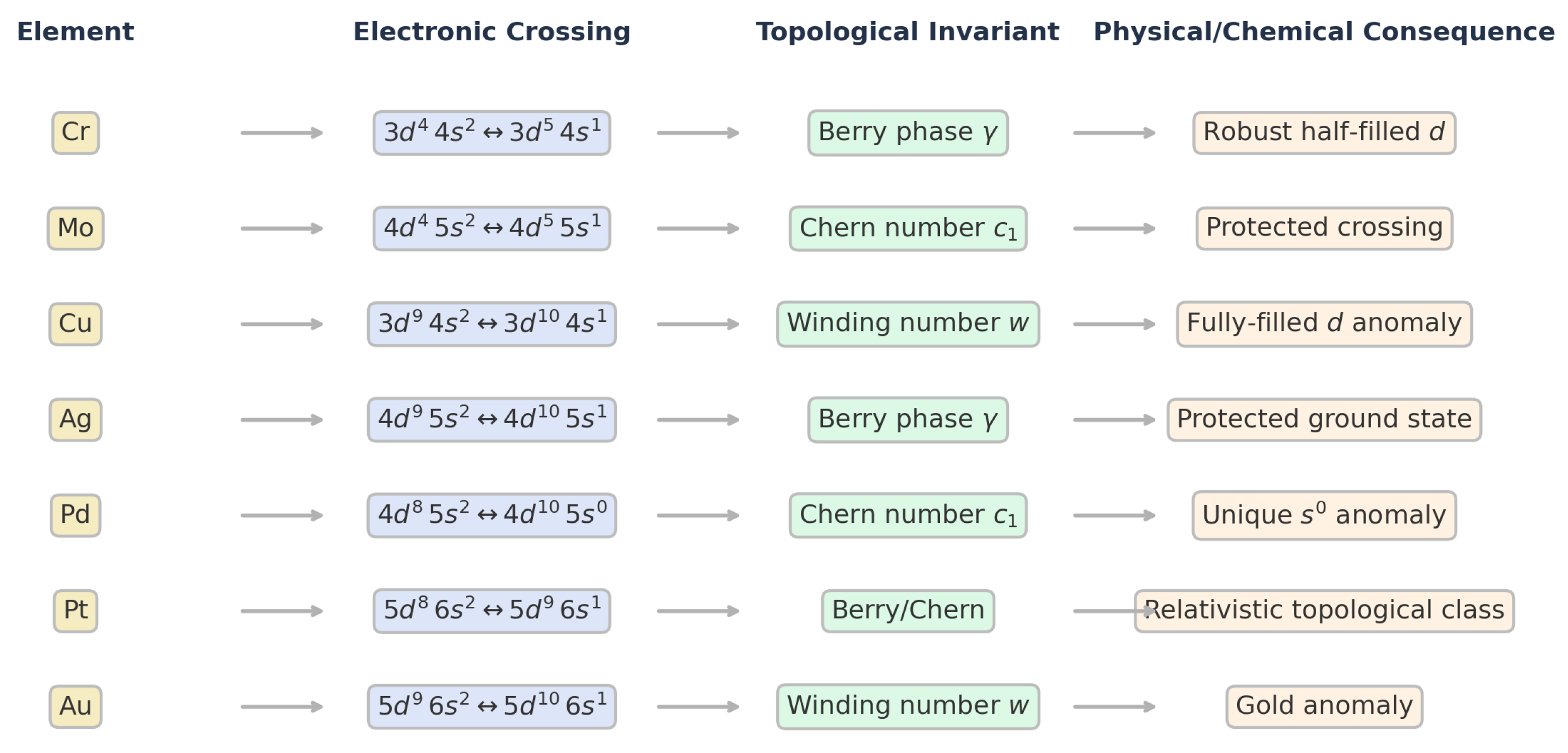

| Element | Z | Madelung Pred. | Observed Config. | Crossing Subspaces | Main Mechanism |

| Cr | 24 | vs | Topological | ||

| Cu | 29 | vs | Topological | ||

| Mo | 42 | vs | Topological | ||

| Ag | 47 | vs | Topological | ||

| Pd | 46 | vs | Topological | ||

| Pt | 78 | vs | Topol. + Relativistic | ||

| Au | 79 | vs | Topol. + Relativistic |

Predictive Power and Generalization

Mathematical Formulation of Spectral Crossings

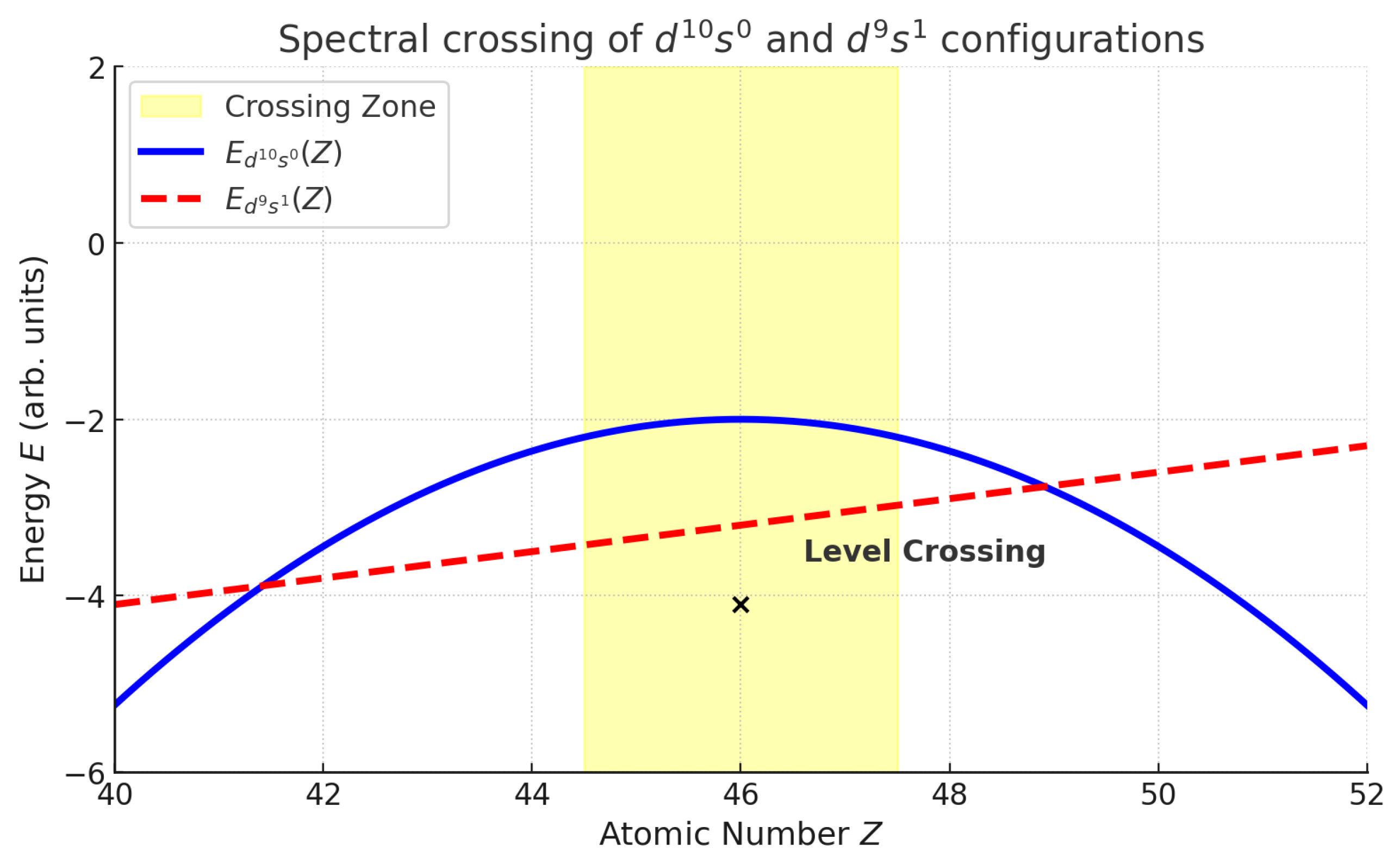

Explicit Example: Palladium ()

Generalized Approach: Other Elements

Symmetry Check: Group-Theoretical Constraint

- Cr (): vs (half-filled d).

- Cu (): vs (filled d).

- Mo (): vs (half-filled d).

- Ag (): vs (filled d).

- Pd (): vs (unique ).

- Pt (): vs (relativistic/topological).

- Au (): vs (relativistic/topological).

Discussion and Outlook

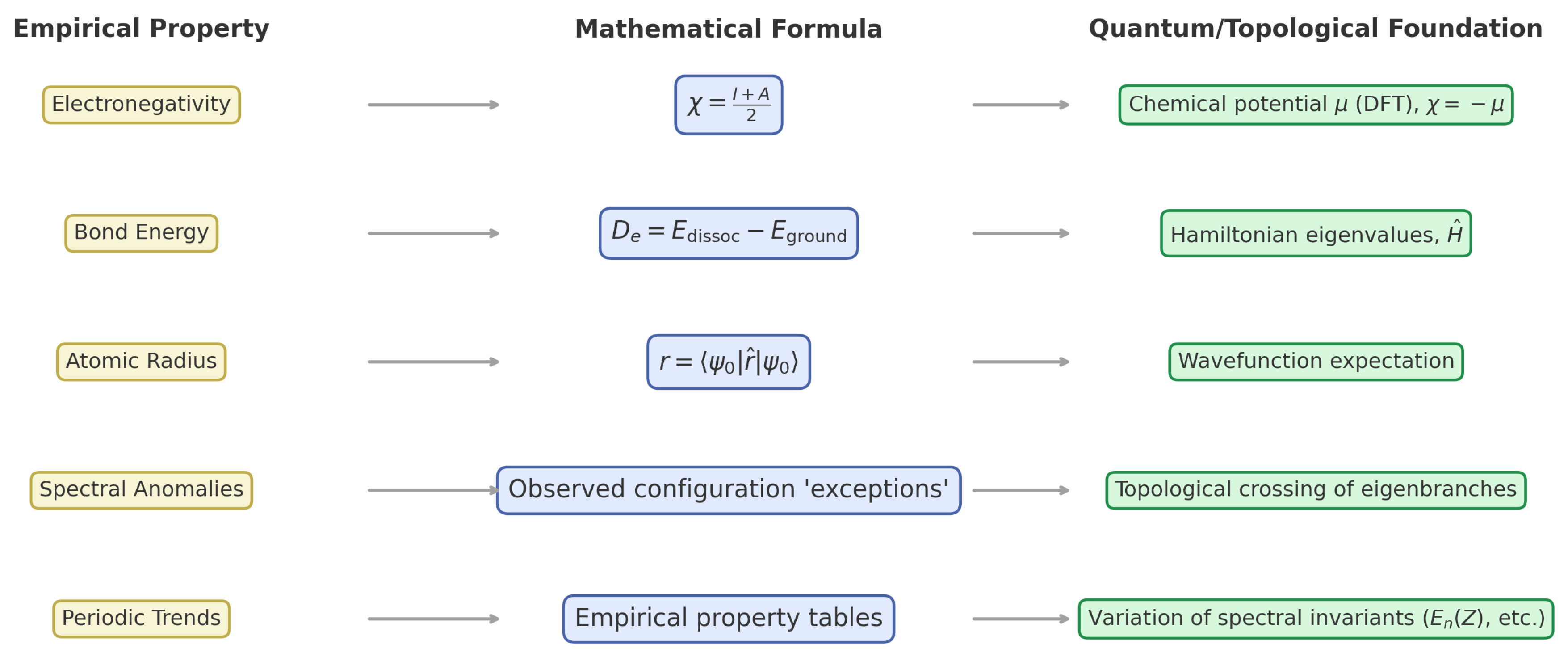

Chemical–Mathematical Comparison of Periodic Properties

- Electronegativity: As a bonded-electron attraction tendency, it is expressed by Mulliken’s mean of first ionization energy I and electron affinity A,and identified in DFT with the negative chemical potential,

- Bond Energy: Bond strength is given by the eigenvalue difference between dissociated and bound molecular states,and is computable from first principles.

- Atomic/Ionic Radius: Tabulated radii correspond to ground-state radial expectation values,with correlation and relativistic corrections.

- Spectral Anomalies: Apparent “exceptions” (Pd, Cr, Cu, etc.) are enforced by protected crossings between symmetry-distinct configurations, as predicted by spectral topology.

- Periodic Trends: Trends are expressible as variations of spectral invariants (orbital energies, degeneracies, topological indices) with atomic number Z and electron count.

Mathematical Foundations Beyond Chemical Heuristics

- Trends and exceptions in the transition series are read as robust features of the atomic Hamiltonian’s spectrum; exceptions arise from symmetry-protected crossings between inequivalent subspaces.

- Key properties (electronegativity, bond energies, radii) are formulated as functionals of eigenvalues/eigenstates of the many-electron Hamiltonian.

- Bonding/reactivity are attributed to the structure and splitting of quantum states rather than fixed classical bond types.

- Group theory/topological invariants provide predictive tools for bonding, magnetism, and the existence/location of anomalies.

- Approximate methods (DFT/MO) are recognized as approximations to the exact many-body problem, with successes and failures reflecting the underlying spectrum.

Mathematical Synthesis: Topology, Bundles, and Spectral Invariants in the Periodic Table

- (1)

-

Anomalies as Topological Invariants. For , each branch is endowed with invariants (Chern number , Berry phase , winding number w):Anomalies occur at singularities or quantized jumps of these invariants.

- (2)

- Periodicity as a Vector Bundle. The eigenspaces of define a vector bundle over . Electronic anomalies are modeled as bundle singularities,encoding stability and universality.

- (3)

- Generalization. For synthetic atoms/quantum dots/ion traps, additional parameters (confinement, field F, pressure P) are included and crossings predicted from

- (4)

- Beyond Standard DFT. Local minima sampling may miss global topological transitions; explicit computation of , Berry curvature, and homotopy invariants (e.g., ) is required to track changes with Z or .

- (5)

- Unified View. Structure and anomalies are classified by the topology of , with degeneracies, Chern numbers, Berry phases, and bifurcations providing the organizing data.

Spectral Topology and Periodicity: Formal and Disruptive Synthesis

- (1)

-

Anomalies as Topological Invariants. For , the n-th eigenstate is smooth on the parameter manifold M except at degeneracies.

- Berry phase: encirclement of a degeneracy (e.g., vs in Pd) yieldswith (mod ) indicating protection.

- Chern number: for a two-level model over ,quantizing the degeneracy’s “monopole charge.”

- (2)

- Vector Bundles and Singularities. Eigenstates define a bundle ; at (Pd), bundles associated with and cross, with charge given by Chern class differences.

- (3)

- Exotic Regimes and Control. High fields B, confinement, or non-integer Z lead to crossings determined by

- (4)

- Algorithmic Needs. Detection of topological transitions requires explicit Berry-connection/curvature evaluation; standard functionals may fail to anticipate states such as Pd’s .

- (5)

- Topological Classification of Matter. Periodicity and anomalies are captured by equivalence classes of spectra, paralleling quantized phenomena (e.g., quantum Hall plateaus).

Explicit Application: Topological Invariants Across the Periodic Table

-

Cr ():with Berry phase ensuring protection.

-

Mo ():with at degeneracy.

-

Cu ():with winding number .

-

Ag ():showing a quantized spectral jump.

-

Pd ():with monopole-like Berry curvature stabilizing .

-

Pt ():enhanced by spin–orbit/relativistic effects and Chern class change.

-

Au ():with matching experiment.

- Synthetic/Exotic: For engineered Z, field F, or non-integer occupations,with nontrivial Berry curvature regions accessible to interference/spectroscopy.

- Berry phase : a geometric phase accumulated by adiabatic transport around a degeneracy, certifying a robust, symmetry-protected crossing (e.g., Cr, Ag).

- Chern number : an integer invariant of eigenbundles’ curvature, diagnosing spectral “monopoles”/topological charge in parameter space (e.g., Mo, Pd).

- Winding number : the count of eigenvalue windings versus Z, indicating quantized ground-state jumps (e.g., Cu, Au).

Topological Invariants and Physical Interpretation Across Periodic Anomalies

-

Cr ():Berry phase : a protected switch to half-filled ; smooth deformations cannot remove the transition.

-

Mo ():Chern number : a quantized curvature source (“monopole”) at the crossing; inevitability of the anomaly is implied.

-

Cu ():Winding : a single spectral winding through flips the ground state to filled .

-

Ag ():Berry phase : protection analogous to Cr, stabilizing the observed state.

-

Pd ():Chern number : monopole-like curvature enforces the unique configuration.

-

Pt ():Berry/Chern: relativistic effects reinforce a change of topological class across the crossing.

-

Au ():Winding : a full winding yields the stable state.

- Exotic/Synthetic: In engineered quantum dots/Rydberg platforms, crossings are designed by tuning external parameters; nontrivial are detected via interference or spectroscopy.

| Element | Transition | Invariant | Physical Meaning |

| Cr | Berry phase | Robust half-filled d | |

| Mo | Chern number | Monopole, protected crossing | |

| Cu | Winding number w | Filled d-shell anomaly | |

| Ag | Berry phase | Protected ground state | |

| Pd | Chern number | Unique anomaly | |

| Pt | Berry/Chern | Relativistic topological class | |

| Au | Winding number w | Gold anomaly |

Conclusions

Final Remarks

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- B. N. Figgis & M. A. Hitchman, "Ligand Field Theory and Its Applications," Wiley-VCH, 2000.

- F. Albert Cotton, "Chemical Applications of Group Theory," 3rd Edition, Wiley, 1999.

- J. C. Slater, Quantum Theory of Atomic Structure. McGraw-Hill, 1960.

- N. F. Hall, “The periodic table: Its story and its significance,” Oxford University Press, 2015.

- P. Pyykkö, “Relativistic Effects in Chemistry: More Common Than You Thought,” Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, vol. 63, pp. 45–64, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Cornwell, Group Theory in Physics: An Introduction. Academic Press, 1984. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Berry, “Quantal Phase Factors Accompanying Adiabatic Changes,” Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A, vol. 392, pp. 45–57, 1984. [CrossRef]

- P. A. M. Dirac, The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 1st ed. Oxford University Press, 1930.

- A. Connes, Noncommutative Geometry. Academic Press, 1994.

- E. P. Wigner, Group Theory and its Application to the Quantum Mechanics of Atomic Spectra. Academic Press, 1959. [CrossRef]

- R. F. W. Bader, Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory. Oxford University Press, 1990.

- P. Atkins and J. de Paula, Physical Chemistry, 10th ed. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- A. R. P. Rau, “The Aufbau Principle: Quo Vadis?,” Foundations of Chemistry, vol. 12, pp. 293–300, 2010.

- R. D. Cowan, The Theory of Atomic Structure and Spectra. University of California Press, 1981. [CrossRef]

- E. Madelung, “Das elektrische Feld in Systemen von Atomen,” Physikalische Zeitschrift, vol. 28, pp. 1127–1129, 1936.

- W. Kutzelnigg, “The Physics and Chemistry of Wave Packets,” Chemical Physics, vol. 329, pp. 99–116, 2006.

- T. Kato, “On the eigenfunctions of many-particle systems in quantum mechanics,” Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, vol. 10, pp. 151–177, 1957. [CrossRef]

- B. Simon, “The definition of molecular resonance curves by the method of exterior complex scaling,” Physics Letters A, vol. 71, pp. 211–214, 1979. [CrossRef]

- M. Tinkham, Group Theory and Quantum Mechanics, Dover, 2003.

- J. J. Sakurai and J. Napolitano, Modern Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- L. Pauling, “The Nature of the Chemical Bond,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 53, pp. 1367–1400, 1932.

- A. Kramida et al., “NIST Atomic Spectra Database (ver. 5.11),” [Online]. Available: https://physics.nist.gov/asd.

- H. Kleinert, Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, 5th ed. World Scientific, 2009.

- M. V. Berry and M. R. Dennis, “Topological events on wave dislocation lines: birth and death of loops, and reconnection,” J. Phys. A: Math. Theor., vol. 43, 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Balachandran, G. Marmo, B.-S. Skagerstam, and A. Stern, Gauge Symmetries and Fibre Bundles: Applications to Particle Dynamics. Springer, 1991.

- R. B. Laughlin, “Quantized Hall conductivity in two dimensions,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 23, pp. 5632–5633, 1981.

- F. D. M. Haldane, “Model for a Quantum Hall Effect without Landau Levels: Condensed-Matter Realization of the ’Parity Anomaly’,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 61, pp. 2015–2018, 1988. [CrossRef]

- P. W. Anderson, “More is Different,” Science, vol. 177, pp. 393–396, 1972.

- W. H. Zurek, “Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 75, pp. 715–775, 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Gutzwiller, Chaos in Classical and Quantum Mechanics. Springer, 1990.

- M. V. Berry, “The adiabatic phase and Pancharatnam’s phase for polarized light,” J. Mod. Opt., vol. 34, pp. 1401–1407, 1987. [CrossRef]

- R. Gilmore, Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Some of Their Applications. Wiley, 1974.

- S. Kobayashi and K. Nomizu, Foundations of Differential Geometry, Vol. 1, Wiley, 1996.

- M. Reed and B. Simon, Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics, Vol. I–IV. Academic Press, 1972–1978.

- W. Fulton and J. Harris, Representation Theory: A First Course. Springer, 1991.

- H. Eyring, “The Activated Complex in Chemical Reactions,” J. Chem. Phys., vol. 3, pp. 107–115, 1935.

- R. de L. Kronig, “The Fine Structure of Helium and Alkali Spectra,” Physica, vol. 1, pp. 545–557, 1934.

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory, 3rd ed., Pergamon, 1977.

- J. Schnack, “Quantum Magnetism in Chemistry and Physics,” Molecules, vol. 11, pp. 475–493, 2006.

- N. F. Mott, “Metal-Insulator Transitions,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 40, pp. 677–683, 1968.

- D. Bohm, Quantum Theory. Prentice-Hall, 1951.

- B. A. Bernevig and T. L. Hughes, Topological Insulators and Topological Superconductors. Princeton Univ. Press, 2013.

- G. F. Koster et al., Properties of the Thirty-Two Point Groups. MIT Press, 1963.

- C. L. Kane and J. E. Moore, “Topological Insulators,” Physics World, vol. 23, pp. 32–36, 2010.

- W. Kohn, “Nobel Lecture: Electronic structure of matter—wave functions and density functionals,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 71, pp. 1253–1266, 1999. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Drukarev, Basics of Quantum Electrodynamics. Springer, 2020.

- R. Hoffmann, Solids and Surfaces: A Chemist’s View of Bonding in Extended Structures. VCH, 1988.

- L. S. Cederbaum, “Electronic correlation in molecules—new theoretical insights,” Chem. Phys. Lett., vol. 463, pp. 227–238, 2008.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).