Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

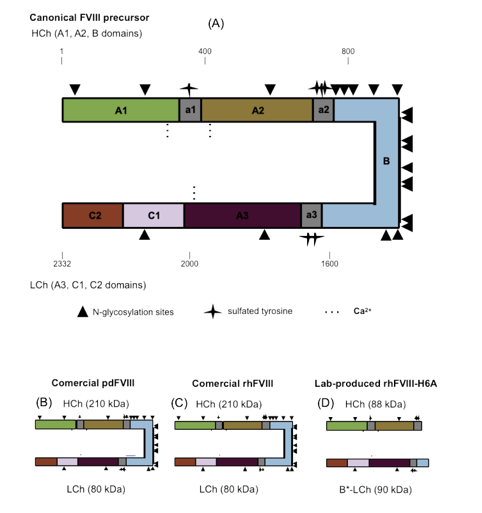

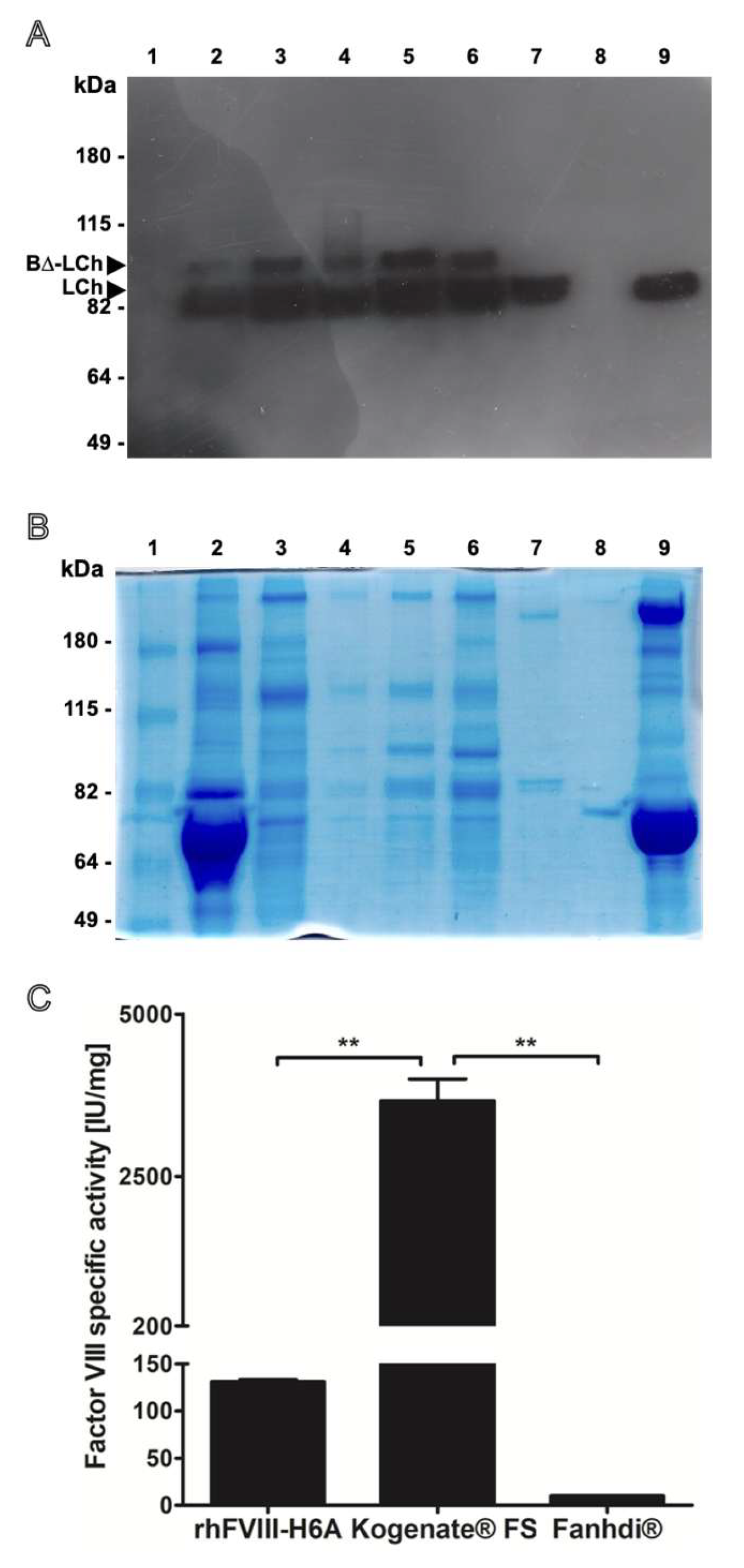

2.1. Production of the Bioengineered Factor VIII (rhFVIII-H6A) Presenting an Artificial Light Chain (LCh) Fused to Part of the B Domain

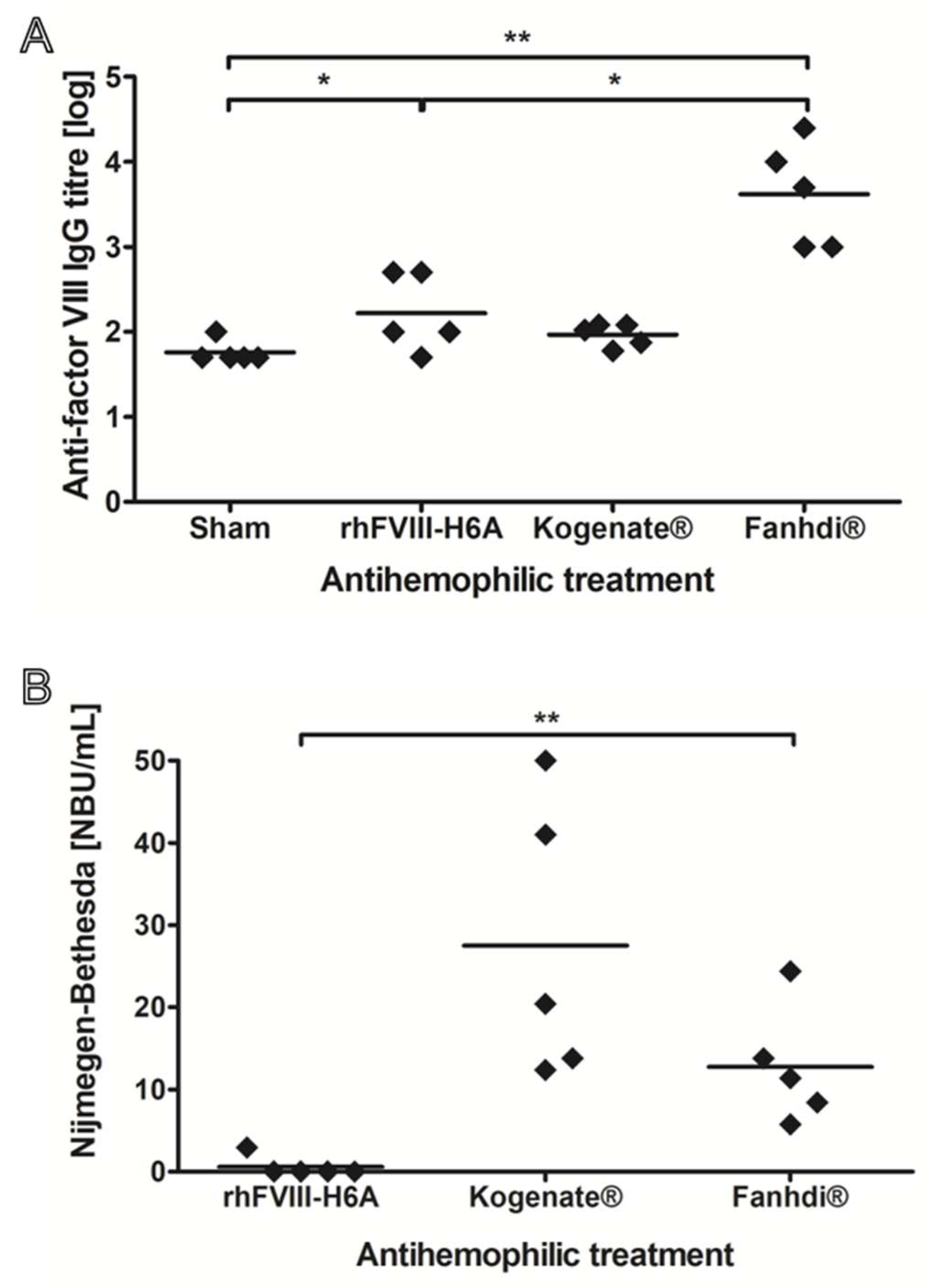

2.2. Low Immunogenicity of rhFVIII-H6A in a Murine Model of Hemophilia A

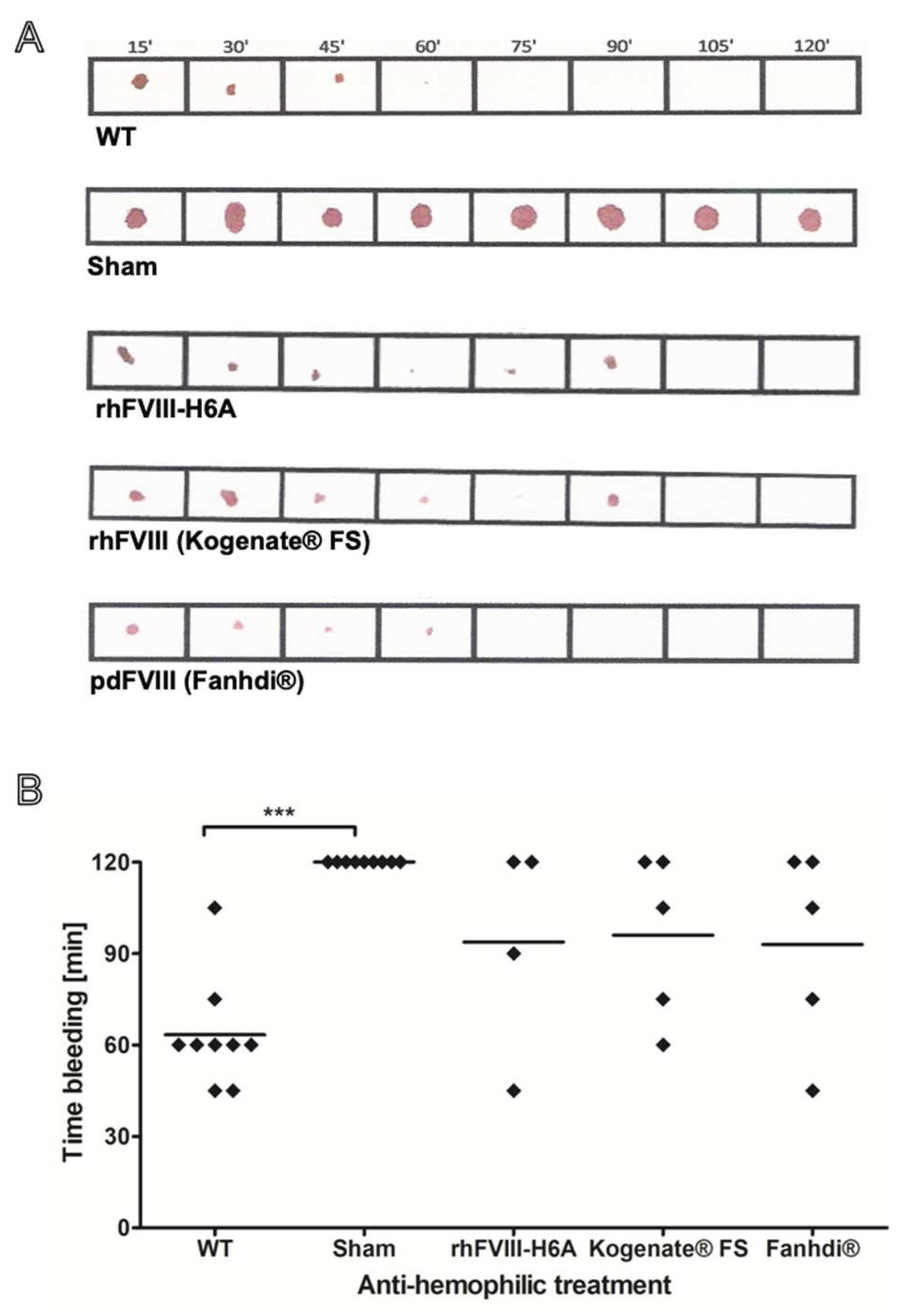

2.3. In Vivo Functional Activity Evaluation of rhFVIII-H6A

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Culture of CHO-DG44 Cell Clones Overexpressing rhFVIII

4.2. Purification of rhFVIII-H6A

4.3. Quantification of Total Proteins

4.4. FVIII Chromogenic Assay

4.5. Western Blot Analysis

4.6. Reference Products

4.7. Animals

4.8. Functional Activity of FVIII

4.9. Induction of Immunological Response to Factor VIII

4.10. Dosage of Total Anti-Factor VIII Antibodies

4.11. Dosage of Total Inhibitory Factor VIII Antibodies

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pipe, S.W.; Morris, J.A.; Shah, J.K.R. Differential interaction of coagulation factor VIII and factor V with protein chaperones calnexin and calreticulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 8537–8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljung, R.; Auerswald, G.; Benson, G.; et al. Inhibitors in haemophilia A and B: Management of bleeds, inhibitor eradication and strategies for difficult-to-treat patients. Eur J Haematol 2019, 102, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharrer, I.; Bray, G.L.; Neutzling, O. Incidence of inhibitors in haemophilia A patients - a review of recent studies of recombinant and plasma-derived factor VIII concentrates. Haemophilia 1999, 5, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, H.; Casadevall, N. Immunogenicity of recombinant human proteins: causes and consequences. J. Neurol. 2004, 251, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbers, H.C.; Crow, S. a, Vulto, A.G., Schellekens, H. Interchangeability, immunogenicity and biosimilars. Nat Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 1186–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, E.; Smith, H.W.; Shores, E.; et al. Recommendations on risk-based strategies for detection and characterization of antibodies against biotechnology products. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008, 333, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.D.F.S. Immunogenicity of biotherapeutics in the context of developing biosimilars and biobetters. Drug Discov. Today. 2011, 16, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Lawler, A.M.; Antonarakis, S.E.; High, K.A.; Gearhart, J.D.; Kazazian, H.H. Targeted disruption of the mouse factor VIII gene produces a model of haemophilia A. Nat. Genet. 1995, 10, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.F.; Parker, E.T.; Barrow, R.T.; Langley, T.J.; Church, W.R.; Lollar, P. The Comparative Immunogenicity of Human and Porcine Factor VIII in Hemophilia A Mice. Thromb Haemost. 2009, 102, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.F.; Lubin, I.M.; Nakai, H.; Saenko, E.L.; Hoyer, L.W.; Scandella, D.; Lollar, P. Residues 484-508 contain a major determinant of the inhibitory epitope in the A2 domain of human factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 1995, 270, 14505–14509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.T.; Healey, J.F.; Barrow, R.T.; Craddock, H.N.; Lollar, P. Reduction of the inhibitory antibody response to human factor VIII in hemophilia A mice by mutagenesis of the A2 domain B-cell epitope. Blood. 2004, 104, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urlaub, G.; Mitchell, P.J.; Kas, E.; Chasin, L.A.; Funanage, V.L.; Myoda, T.T.; Hamlin, J. Effect of gamma rays at the dihydrofolate reductase locus: deletions and inversions. Somat Cell Mol Genet 1986, 12, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demasi, M.A.; de, S. Molina, E.; Bowman-Colin, C.; Lojudice, F.H.; Muras, A.; Sogayar, M.C. Enhanced Proteolytic Processing of Recombinant Human Coagulation Factor VIII B-Domain Variants by Recombinant Furins. Mol Biotechnol 2016, 58, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Fang, X.D.; Zhu, J.; et al. The gene expression of coagulation factor VIII in mammalian cell lines. Thrombosis Research 1999, 95, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonemura, H.; Sugawara, K.; Nakashima, K.; et al. Efficient production of recombinant human factor VIII by co-expression of the heavy and light chains. Protein Eng. 1993, 6, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, E.S.; Fujita, A.; Sogayar, M.C.; Demasi, M.A. A quantitative and humane tail bleeding assay for efficacy evaluation of antihaemophilic factors in haemophilia A mice. Haemophilia 2014, 20, e392–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, B.; van Heerde, W.L.; Laros-van Gorkom, B. a P.. Improvements in factor VIII inhibitor detection: From Bethesda to Nijmegen. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2009, 35, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messori, A. Inhibitors in Hemophilia A: A Pharmacoeconomic Perspective. Semin Thromb Hemost 2018, 44, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W.; Pratt, K.P. Factor VIII: Perspectives on Immunogenicity and Tolerogenic Strategies. Front Immunol 2020, 10, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the clinical investigation of recombinant and plasma-derived factor VIII products. EMA/CHMP/BPWP/144533/2009 rev. 2. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). London. 26 July 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-recombinant-and-human-plasma-derived-factor-viii-products-revision-2_en.pdf.

- Hermeling, S.; Crommelin, D.J.A.; Schellekens, H.; Jiskoot, W. Structure-immunogenicity relationships of therapeutic proteins. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Cousens, L.P.; Alvarez, D.; Mahajan, P.B. Determinants of immunogenic response to protein therapeutics. Biologicals 2012, 40, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, S.L.; Healey, J.F.; Parker, E.T.; Barrow, R.T.; Lollar, P. Antihuman factor VIII C2 domain antibodies in hemophilia A mice recognize a functionally complex continuous spectrum of epitopes dominated by inhibitors of factor VIII activation. Blood 2007, 110, 4234–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, K.P.; Qian, J.; Ellaban; et al. Immunodominant T-cell epitopes in the factor VIII C2 domain are located within an inhibitory antibody binding site. Thromb. Haemost. 2004, 92, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandella, D.H.; Nakai, H.; Felch, M.; Mondorf, W.; Scharrer, I.; Hoyer, L.W.; Saenko, E.L. In hemophilia A and autoantibody inhibitor patients: the factor VIII A2 domain and light chain are most immunogenic. Thromb. Res. 2001, 101, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroblewska, A.; van Haren, S.D.; Herczenik; et al. Modification of an exposed loop in the C1 domain reduces immune responses to factor VIII in hemophilia A mice. Blood 2012, 119, 5294–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuerth, M.E.; Cragerud, R.K.; Clint Spiegel, P. Structure of the Human Factor VIII C2 Domain in Complex with the 3E6 Inhibitory Antibody. Scientific Reports 2015, 5:1 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne-Lissalde, G.; Lacroix-Desmazes, S.; Wootla, B.; et al. Molecular characterization of human B domain-specific anti-factor VIII monoclonal antibodies generated in transgenic mice. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 98, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Qiu, H. The Mechanistic Impact of N-Glycosylation on Stability, Pharmacokinetics, and Immunogenicity of Therapeutic Proteins. J Pharm Sci 2019, 108, 1366–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.D.; Swystun, L.L.; Cartier, D.; et al. N-linked glycosylation modulates the immunogenicity of recombinant human factor VIII in hemophilia A mice. Haematologica 2018, 103, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, C.M.; Zerra, P.E.; Shin, S.; et al. Nonhuman glycans can regulate anti-factor VIII antibody formation in mice. Blood 2022, 139, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisal, D.S.; Kosloski, M.P.; Middaugh, C.R.; Bankert, R.B.; Balu-Iyer, S. Native-like aggregates of factor VIII are immunogenic in von Willebrand factor deficient and hemophilia a mice. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 2055–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzengruber, J.; Lubich, C.; Prenninger, T.; et al. Comparative analysis of marketed factor VIII products: recombinant products are not alike vis-a-vis soluble protein aggregates and subvisible particles. J Thromb Haemost 2018, 16, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baunsgaard, D.; Nielsen, A.D.; Nielsen; et al. A comparative analysis of heterogeneity in commercially available recombinant factor VIII products. Haemophilia 2018, 24, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofaro, R.; de Sacco, M.; Lancellotti, S.; Berruti, F.; Garagiola, I.; Valsecchi, C.; Basso, M.; Stasio, E.d.; Peyvandi, F. Molecular Aggregation of Marketed Recombinant FVIII Products: Biochemical Evidence and Functional Effects. TH Open 2019, 3, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundahl, M.L.E.; Fogli, S.; Colavita, P.E.; Scanlan, E.M. Aggregation of protein therapeutics enhances their immunogenicity: causes and mitigation strategies. RSC Chem Biol 2021, 2, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratanji, K.D.; Derrick, J.P.; Dearman, R.J.; Kimber, I. Immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins: influence of aggregation. J Immunotoxicol 2014, 11, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.S. Effects of protein aggregates: an immunologic perspective. AAPS J 2006, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, V.S.; Middaugh, C.R.; Balasubramanian, S. Influence of aggregation on immunogenicity of recombinant human factor VIII in hemophilia A mice. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delignat, S.; Repessé; Y; Navarrete; et al. Immunoprotective effect of von Willebrand factor towards therapeutic factor VIII in experimental haemophilia A. Haemophilia 2012, 18, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Repessé; Y; Bayry, J. ; et al. VWF protects FVIII from endocytosis by dendritic cells and subsequent presentation to immune effectors. Blood 2007, 109, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveri, S.v.; Dasgupta, S.; Andre, S.; et al. Factor VIII inhibitors: role of von Willebrand factor on the uptake of factor VIII by dendritic cells. Haemophilia 2007, 13, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix-Desmazes, S.; Repessé; Y; Kaveri, S. v.; Dasgupta, S. The role of VWF in the immunogenicity of FVIII. Thromb Res 2008, 122, S3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorvillo, N.; Hartholt, R.B.; Bloem, E.; et al. von Willebrand factor binds to the surface of dendritic cells and modulates peptide presentation of factor VIII. Haematologica 2016, 101, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, S.; Navarrete, A.M.; Bayry, J.; et al. A role for exposed mannosylations in presentation of human therapeutic self-proteins to CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 8965–8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delignat, S.; Rayes, J.; Dasgupta, S.; et al. Removal of Mannose-Ending Glycan at Asn2118 Abrogates FVIII Presentation by Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettingshausen, C.E. , Kreuz, W. Recombinant vs. plasma-derived products, especially those with intact VWF, regarding inhibitor development. Haemophilia 2006, 12, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvez, T.; Chambost, H.; D’Oiron, R.; et al. Analyses of the FranceCoag cohort support differences in immunogenicity among one plasma-derived and two recombinant factor VIII brands in boys with severe hemophilia A. Haematologica 2018, 103, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyvandi, F.; Mannucci, P.M.; Garagiola, I.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Factor VIII and Neutralizing Antibodies in Hemophilia A. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 2054–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, D.; Rodriguez, H.; Vehar, G.A. Proteolytic processing of human factor VIII. Correlation of specific cleavages by thrombin, factor Xa, and activated protein C with activation and inactivation of factor VIII coagulant activity. Biochemistry 1986, 25, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmon, C.T. Interactions between the innate immune and blood coagulation systems. Trends. Immunol. 2004, 25, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, F.J.; Fay, P.J. Regulation of blood coagulation by the protein C system. FASEB J 1992, 6, 2561–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, A.R.; Parsons, N.A.; Samelson-Jones, B.J.; et al. Activated protein C has a regulatory role in factor VIII function. Blood 2021, 137, 2532–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skupsky, J.; Zhang, A.; Su, Y.; Scott, D.W. A role for thrombin in the initiation of the immune response to therapeutic factor VIII. Blood 2009, 114, 4741–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfistershammer, K.; Stöckl, J.; Siekmann, J.; Turecek, P.L.; Schwarz, H.P.; Reipert, B.M. Recombinant factor VIII and factor VIII-von Willebrand factor complex do not present danger signals for human dendritic cells. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 96, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, S.L.; Cox, C.L.; Healey; et al. A major determinant of the immunogenicity of factor VIII in a murine model is independent of its procoagulant function. Blood 2012, 120, 2512–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadharan, B.; Delignat, S.; Ollivier; et al. Role of coagulation-associated processes on factor VIII immunogenicity in a mouse model of severe hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost 2014, 12, 2065–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerra, P.E.; Parker, E.T.; Baldwin, W.H.; et al. Engineering a Therapeutic Protein to Enhance the Study of Anti-Drug Immunity. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).